Abstract

The impact of cumulative dosing and premature drug discontinuation (PMDD) of bortezomib (V), thalidomide (T), and dexamethasone (D) on overall survival (OS), event-free survival (EFS), time to next therapy, and post-relapse survival in Total Therapy 3 were examined, using time-dependent methodology, relevant to induction, peritransplantation, consolidation, and maintenance phases. Univariately, OS and EFS were longer in case higher doses were used of all agents during induction, consolidation (except T), and maintenance (except V and T). The favorable OS and EFS impact of D induction dosing provided the rationale for examining the expression of glucocorticoid receptor NR3C1, top-tertile levels of which significantly prolonged OS and EFS and rendered outcomes independent of D and T dosing, whereas T and D, but not V, dosing was critical to outcome improvement in the bottom-tertile NR3C1 setting. PMDD of V was an independent highly adverse feature for OS (hazard ratio = 6.44; P < .001), whereas PMDD of both T and D independently imparted shorter time to next therapy. The absence of adverse effects on postrelapse survival of dosing of any VTD components and indeed a benefit from V supports the use up-front of all active agents in a dose-dense and dose-intense fashion, as practiced in Total Therapy 3, toward maximizing myeloma survival.

Introduction

The superiority of Total Therapy 3 (TT3)1,2 to Total Therapy 2 (TT2)3 was limited to the approximately 85% of patients presenting with gene expression profiling (GEP)–defined low-risk myeloma.4,5 As a consequence of shortened induction before and consolidation after melphalan-based tandem transplantations in TT3 versus TT2, the compliance with intended protocol steps was improved which, along with the incorporation of bortezomib, affected prognosis favorably.6 TT3 applied 2 cycles of VTD-PACE (bortezomib, thalidomide, dexamethasone; 4-day continuous infusions of cisplatin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide) as induction before and, at reduced doses, as consolidation after melphalan-based tandem transplantation. Thalidomide and dexamethasone were given at 50 mg/day and 20 mg/day for 4 days every 28 days to “bridge” drug-free intervals between induction cycles, whereas thalidomide dosing was 100 mg/day with dexamethasone 20 mg/day for 4 days every 28 days between transplantations and consolidation cycles. Maintenance therapy comprised VTD (bortezomib [V], thalidomide [T], and dexamethasone [D]) in year 1 and TD without V in years 2 and 3.

Here, we examined whether cumulative dosing of VTD components and their premature drug discontinuation (PMDD) impacted overall survival (OS), event-free survival (EFS), time to next therapy (TNT), and postrelapse survival (PRS) in the context of baseline variables and completion of second transplantation and both cycles of consolidation therapy.

Methods

Trial details have been reported previously.1,2,4,5 Briefly, TT3 accrued 303 newly diagnosed patients with symptomatic or progressive myeloma between February 2004 and July 2006. GEP analysis of CD138-enriched plasma cells was performed in a subset of 275 patients.7 GEP parameters considered included risk designation (high vs low),4 molecular subgroups (hyperdiploidy, low bone disease, CCND1 without CD-1 and with CD20 coexpression, MAF/MAFB, MMSET/FGFR3, myeloid, proliferation),8 and delTP53 status.9,10 The median follow-up of live patients is 55 months.

Definition of clinical endpoints followed Blade et al11 and International Myeloma Working Group criteria12 for the definition of complete response (CR), which also required absence, by bone marrow flow cytometry, of aneuploidy and light chain restriction.13 CR duration (CRD) was counted from onset of CR, whereas OS and EFS were measured from initiation of protocol therapy. Events included recurrence and death from any cause for CRD and EFS and death from any cause for OS. PRS was measured from the onset of confirmed relapse to death, whereas TNT considered the time interval from start of protocol therapy to the first non–protocol-defined salvage therapy or to change in treatment because of protocol therapy-associated toxicities. All patients signed a written informed consent form in keeping with institutional and federal guidelines and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Both protocols and their revisions have been approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Arkansas. This study was registered at http://clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00081939.

The impact of cumulative dosing of VTD components on OS, EFS, TNT, and PRS was addressed in relationship to the individual drugs in milligram-per-protocol step or month of maintenance of V, T, and D as continuous variables, applying actual doses taken through the end of induction, transplantation, and consolidation therapy and then serially by the end of each month of maintenance. Such analyses were carried out both regardless of and in relationship to whether patients had completed second transplantation and one or 2 cycles of consolidation therapies. We also investigated the clinical consequences of PMDD of VTD components before the protocol-prescribed time lines.

Kaplan-Meier statistical methods were used for OS, EFS, and time to CR and CRD plots,14 and the log-rank test was used for comparisons.15 The impact of cumulative dosing of V, T, and D on TNT and PRS was also examined. Multivariate Cox regression modeling16 was used to determine which baseline parameters and time-dependent drug dosages significantly affected the aforementioned endpoints. Treating the drug dosages as continuous, time-dependent variables allowed us to analyze the impact of the doses on outcomes for the entire population, unlike in land-marking methodology in which only a population subset surviving the landmark can be considered. We also investigated the impact of drug doses at specific protocol steps, as well as overall impact.

Results

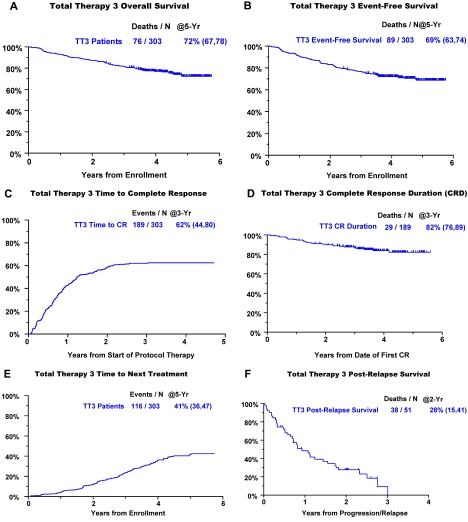

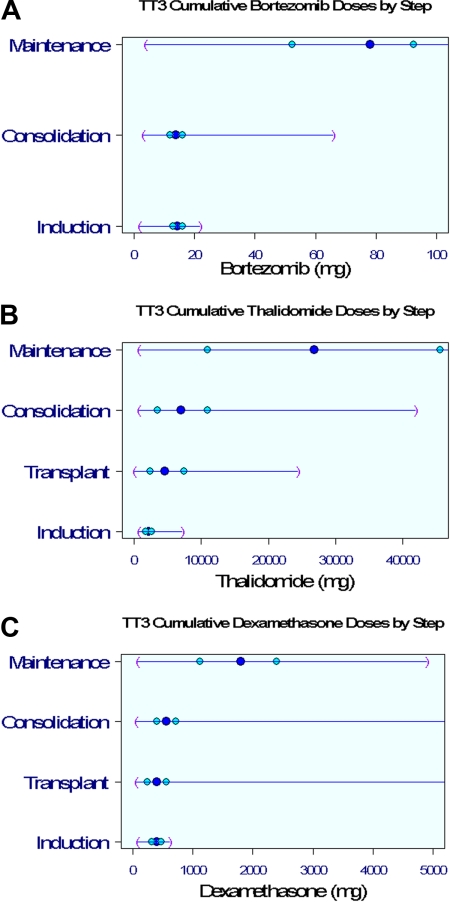

Clinical outcomes are portrayed from enrollment for OS, EFS, and time to CR and for CRD from onset of CR (Figure 1). The 5-year estimates of OS and EFS are 72% and 69%, respectively (Figure 1A-B). Of the 62% of patients achieving CR (Figure 1C), 82% retained this status 5 years later (Figure 1D). Within 5 years, 41% of patients had received subsequent nonprotocol therapy (Figure 1E), whereas the 2-year PRS estimate was 28% (Figure 1F). Figure 2 depicts V, T, and D dosing details applied during the different phases of the TT3 protocol. The dosing variation for all 3 agents was particularly pronounced in the maintenance phase as a consequence of dose reduction or cessation of treatment resulting from toxicities.

Figure 1.

Clinical outcomes with TT3. (A) OS. (B) EFS. (C) Cumulative incidence of CR. (D) CRD from onset of CR. (E) TNT. (F) PRS.

Figure 2.

Drug dosing distributions by protocol step. Dark blue circle in the middle represents the median; lighter blue circles, 25%/75%; and purple parentheses, minimum/maximum values. (A) Cumulative bortezomib doses. (B) Cumulative thalidomide doses. (C) Cumulative dexamethasone doses.

Relevant to pretreatment variables, both OS and EFS were adversely affected by GEP-defined high-risk disease, cytogenetic abnormalities (CAs), and elevated serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and creatinine (Table 1). Conversely, OS and EFS were significantly extended in case CR was achieved and when second transplantation and both consolidation therapy cycles were completed. Regarding VTD dosing, OS and EFS were longer when higher doses had been delivered of all 3 agents during induction, of V and D in consolidation, and of D in maintenance. Given the prognostic implications of cumulative dosing of D throughout all phases of therapy, we investigated, by GEP analysis, whether the expression level of its target, glucocorticoid receptor gene NR3C1, impacted clinical outcome. Indeed, NR3C1 top-tertile expression levels were linked to longer and bottom-tertile levels to shorter OS and EFS. Table 2 examines how NR3C1 expression levels impacted prognosis in the context of cumulative dosing of all 3 VTD components, relative to their phase of drug administration. A beneficial dosing effect applied to D and T during induction and less obviously during later treatment phases in case of bottom-tertile NR3C1 levels; dosing trends were noted in mid-tertile and dosing independence in top-tertile NR3C1 cases. A V dosing effect was limited to patients with mid-tertile NR3C1 levels, pertaining to induction and consolidation phases. CR rates were higher with increased dosing for all 3 agents, reaching significance levels during most treatment phases with bottom-tertile, less so with mid-tertile, and least with top-tertile levels of the glucocorticoid receptor gene (data not shown). CRD was VTD dosing-neutral and independent of NR3C1 expression (not shown).

Table 1.

Cox regression analyses of baseline and time-dependent variables (PMDD of V, T, and D) in relationship to phase of protocol

| Variable | n/N (%) | OS |

EFS |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P (Wald χ2 test in Cox regression) | HR (95% CI) | P (Wald χ2 test in Cox regression) | ||

| Univariate analysis | |||||

| β2M ≥ 3.5 mg/L | 136/303 (45) | 2.26 (1.42, 3.59) | < .001 | 2.02 (1.33, 3.09) | .001 |

| β2M > 5.5 mg/L | 65/303 (21) | 3.67 (2.33, 5.78) | < .001 | 3.45 (2.26, 5.26) | < .001 |

| Creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL | 23/303 (8) | 2.88 (1.58, 5.23) | < .001 | 3.31 (1.92, 5.69) | < .001 |

| CRP ≥ 8 mg/L | 100/302 (33) | 1.53 (0.97, 2.42) | .069 | 1.77 (1.16, 2.69) | .008 |

| Hb < 10 g/dL | 94/303 (31) | 2.26 (1.44, 3.56) | < .001 | 2.33 (1.54, 3.54) | < .001 |

| LDH ≥ 190 U/L | 81/303 (27) | 3.12 (1.98, 4.89) | < .001 | 3.25 (2.14, 4.93) | < .001 |

| Cytogenetic abnormalities | 100/302 (33) | 2.80 (1.78, 4.41) | < .001 | 2.32 (1.53, 3.53) | < .001 |

| GEP high-risk | 40/275 (15) | 4.66 (2.83, 7.66) | < .001 | 4.50 (2.83, 7.16) | < .001 |

| GEP MAF/MAFB subgroup | 22/275 (8) | 2.41 (1.26, 4.59) | .008 | 2.09 (1.11, 3.95) | .023 |

| GEP proliferation subgroup | 27/275 (10) | 2.73 (1.49, 5.02) | .001 | 2.64 (1.50, 4.63) | < .001 |

| GEP NR3C1 bottom tertile | 91/274 (33) | 1.57 (0.97, 2.54) | .068 | 1.83 (1.18, 2.83) | .007 |

| GEP NR3C1 top tertile | 91/274 (33) | 0.56 (0.32, 0.99) | .046 | 0.52 (0.31, 0.88) | .015 |

| Completed transplantation 2* | — | 0.37 (0.21, 0.62) | < .001 | 0.35 (0.21, 0.59) | < .001 |

| Completed consolidation 1* | — | 0.38 (0.22, 0.67) | < .001 | 0.49 (0.29, 0.83) | .008 |

| Completed consolidation 2* | — | 0.45 (0.26, 0.78) | .005 | 0.57 (0.34, 0.98) | .043 |

| Bortezomib during induction (mg)* | — | 0.88 (0.81, 0.96) | .003 | 0.90 (0.83, 0.97) | .008 |

| Bortezomib during consolidation (mg)* | — | 0.94 (0.90, 0.99) | .008 | 0.96 (0.92, 1.00) | .039 |

| Bortezomib during maintenance (mg)* | — | 0.99 (0.98, 1.00) | .083 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) | .286 |

| Dexamethasone during induction (dg)* | — | 0.71 (0.56, 0.89) | .004 | 0.75 (0.60, 0.94) | .011 |

| Dexamethasone during transplantation (dg)* | — | 0.94 (0.84, 1.04) | .210 | 0.92 (0.83, 1.01) | .078 |

| Dexamethasone during consolidation (dg)* | — | 0.85 (0.77, 0.93) | < .001 | 0.89 (0.81, 0.97) | .007 |

| Dexamethasone during maintenance (dg)* | — | 0.93 (0.89, 0.97) | < .001 | 0.97 (0.93, 1.00) | .047 |

| Thalidomide during induction (g)* | — | 0.63 (0.44, 0.90) | .011 | 0.68 (0.50, 0.95) | .021 |

| Thalidomide during transplantation (g)* | — | 0.94 (0.87, 1.02) | .118 | 0.94 (0.87, 1.01) | .071 |

| Thalidomide during consolidation (g)* | — | 0.94 (0.89, 1.00) | .048 | 0.97 (0.92, 1.02) | .220 |

| Thalidomide during maintenance (g)* | — | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) | .094 | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | .824 |

| Premature bortezomib discontinuation* | — | 8.08 (4.41, 14.81) | < .001 | 1.96 (1.19, 3.25) | .009 |

| Premature dexamethasone discontinuation* | — | 7.17 (3.91, 13.15) | < .001 | 1.53 (0.91, 2.58) | .106 |

| Premature thalidomide discontinuation* | — | 7.19 (3.89, 13.29) | < .001 | 1.58 (0.96, 2.60) | .074 |

| Achieved CR* | — | 0.32 (0.19, 0.53) | < .001 | 0.35 (0.22, 0.56) | < .001 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||||

| Creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL | 21/275 (8%) | 2.09 (1.13, 3.87) | .019 | 2.48 (1.42, 4.34) | .001 |

| LDH ≥ 190 U/L | 74/275 (27%) | 1.98 (1.20, 3.26) | .007 | 2.40 (1.52, 3.79) | < .001 |

| Cytogenetic abnormalities | 95/275 (35%) | 2.28 (1.37, 3.79) | .001 | 1.85 (1.16, 2.95) | .010 |

| GEP high-risk | 40/275 (15%) | 2.85 (1.69, 4.79) | < .001 | 3.01 (1.84, 4.94) | < .001 |

| Premature bortezomib discontinuation* | — | 6.44 (3.30, 12.57) | < .001 | 1.59 (0.93, 2.72) | .087 |

| Achieved CR* | — | 0.41 (0.23, 0.72) | .002 | 0.35 (0.21, 0.59) | < .001 |

Analyses were performed of cumulative doses per protocol step (induction, peritransplantation, consolidation, and maintenance). The multivariate model uses stepwise selection with entry level of 0.1 and variable remains if it meets the 0.05 level. Variables considered univariately were age ≥ 65 years, female sex, white race, albumin < 3.5 g/dL, B2M ≥ 3.5 mg/L, B2M > 5.5 mg/L, creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL, CRP ≥ 8 mg/L, Hb < 10 g/dL, LDH ≥ 190 U/L, cytogenetic abnormalities (anytime before enrollment), GEP high-risk, GEP CD-1 subgroup, GEP CD-2 subgroup, GEP hyperdiploidy subgroup, GEP low bone disease subgroup, GEP MAF/MAFB subgroup, GEP MMSET/FGFR3 subgroup, GEP myeloid subgroup, GEP proliferation subgroup, GEP TP53 deletion, GEP NR3C1 bottom tertile, GEP NR3C1 top tertile, completed transplantation 2*, completed consolidation 1*, completed consolidation 2*, bortezomib during induction*, bortezomib during consolidation*, bortezomib during maintenance*, dexamethasone during induction*, dexamethasone during transplantation*, dexamethasone during consolidation*, dexamethasone during maintenance*, thalidomide during induction*, thalidomide during transplantation*, thalidomide during consolidation*, thalidomide during maintenance*, premature bortezomib discontinuation*, premature dexamethasone discontinuation*, premature thalidomide discontinuation*, achieved CR*, and achieved CR before Tx2*. Variables considered for the multivariate model were B2M > 5.5 mg/L, creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL, CRP ≥ 8 mg/L, Hb < 10 g/dL, LDH ≥ 190 U/L, cytogenetic abnormalities (anytime before enrollment), GEP high-risk, GEP MAF/MAFB subgroup, GEP proliferation subgroup, GEP NR3C1 top tertile, completed transplantation 2*, completed consolidation 1*, completed consolidation 2*, bortezomib during induction*, bortezomib during consolidation*, dexamethasone during induction*, dexamethasone during consolidation*, dexamethasone during maintenance*, thalidomide during induction*, achieved CR*, achieved CR before Tx2*, premature bortezomib discontinuation*, premature dexamethasone discontinuation*, and premature thalidomide discontinuation*.

B2M indicates B2-microglobulin; CRP, C-reactive protein; Hb, hemoglobin; and —, not applicaple.

Variable was treated as a time-dependent variable.

Table 2.

Effect of dexamethasone, bortezomib, and thalidomide dosing on clinical outcomes in relationship to glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) expression tertile (univariate analyses)

| Variable | Lowest NR3C1 tertile (N = 91) |

Middle NR3C1 tertile (N = 92) |

Top NR3C1 tertile (N = 91) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| OS | ||||||

| Dexamethasone during induction (all stages of induction combined, dg)* | 0.57 (0.40, 0.79) | < .001 | 0.71 (0.48, 1.04) | .081 | 1.38 (0.73, 2.60) | .322 |

| Dexamethasone during transplantation (dg)* | 0.93 (0.77, 1.13) | .481 | 0.89 (0.74, 1.06) | .193 | 0.93 (0.74, 1.16) | .509 |

| Dexamethasone during consolidation (dg)* | 0.85 (0.72, 1.02) | .082 | 0.79 (0.67, 0.92) | .002 | 0.91 (0.75, 1.11) | .354 |

| Dexamethasone during maintenance (dg)* | 0.92 (0.85, 1.00) | .045 | 0.94 (0.89, 1.00) | .057 | 0.94 (0.87, 1.02) | .144 |

| Bortezomib during induction (mg)* | 0.95 (0.83, 1.10) | .499 | 0.78 (0.69, 0.88) | < .001 | 0.92 (0.73, 1.15) | .441 |

| Bortezomib during consolidation (mg)* | 0.94 (0.86, 1.01) | .108 | 0.93 (0.87, 1.00) | .042 | 0.97 (0.89, 1.06) | .500 |

| Bortezomib during maintenance (mg)* | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | .160 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | .766 | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | .168 |

| Thalidomide during induction (all stages of induction combined, dg)* | 0.49 (0.29, 0.83) | .008 | 0.83 (0.44, 1.57) | .572 | 1.01 (0.42, 2.40) | .988 |

| Thalidomide during transplantation (g)* | 0.86 (0.74, 1.01) | .064 | 0.94 (0.83, 1.07) | .334 | 0.91 (0.77, 1.09) | .307 |

| Thalidomide during consolidation (g)* | 0.86 (0.75, 0.98) | .029 | 0.93 (0.85, 1.02) | .122 | 0.97 (0.86, 1.10) | .658 |

| Thalidomide during maintenance (g)* | 0.97 (0.94, 1.01) | .148 | 1.00 (0.97, 1.02) | .753 | 0.98 (0.94, 1.02) | .338 |

| EFS | ||||||

| Dexamethasone during induction (all stages of induction combined, dg)* | 0.62 (0.46, 0.85) | .003 | 0.72 (0.50, 1.05) | .088 | 1.38 (0.75, 2.53) | .302 |

| Dexamethasone during transplantation (dg)* | 0.91 (0.77, 1.08) | .284 | 0.90 (0.76, 1.06) | .201 | 0.85 (0.69, 1.06) | .152 |

| Dexamethasone during consolidation (dg)* | 0.95 (0.82, 1.09) | .458 | 0.83 (0.72, 0.96) | .012 | 0.87 (0.71, 1.06) | .161 |

| Dexamethasone during maintenance (dg)* | 0.97 (0.91, 1.02) | .247 | 0.97 (0.91, 1.02) | .233 | 0.96 (0.89, 1.04) | .336 |

| Bortezomib during induction (mg)* | 0.96 (0.85, 1.09) | .572 | 0.80 (0.71, 0.90) | < .001 | 0.92 (0.74, 1.14) | .452 |

| Bortezomib during consolidation (mg)* | 0.98 (0.91, 1.05) | .578 | 0.94 (0.88, 1.01) | .089 | 0.95 (0.87, 1.04) | .297 |

| Bortezomib during maintenance (mg)* | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | .429 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | .898 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | .132 |

| Thalidomide during induction (all stages of induction combined, dg)* | 0.51 (0.32, 0.80) | .004 | 0.83 (0.46, 1.50) | .541 | 1.46 (0.65, 3.26) | .361 |

| Thalidomide during transplantation (g)* | 0.85 (0.74, 0.98) | .022 | 0.95 (0.85, 1.07) | .422 | 0.90 (0.76, 1.05) | .186 |

| Thalidomide during consolidation (g)* | 0.96 (0.88, 1.05) | .372 | 0.94 (0.86, 1.03) | .167 | 0.98 (0.87, 1.10) | .703 |

| Thalidomide during maintenance (g)* | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) | .354 | 1.01 (0.98, 1.03) | .592 | 1.00 (0.96, 1.03) | .801 |

Univariate analyses were performed of cumulative doses per protocol step (induction, peritransplantation, consolidation, and maintenance), within each GEP NR3C1 tertile.

Variable was treated as a time-dependent variable.

Supporting the observations of clinically favorable VTD dosing effects were the adverse prognostic implications of PMDD of all VTD components, among which V retained independent significance, after adjusting for all baseline and VTD dosing variables (Table 1). PMDD was significantly linked to older age (≥ 65 years) in case of V (hazard ratio = 1.59; P = .001) and T (hazard ratio = 1.49; P = .007), with a trend observed for D (hazard ratio = 1.29; P = .079).

A variable of increasing importance in cancer therapy is TNT, as a reflection of the time during which the initial protocol-based therapy provided disease control (or treatment-related toxicity was acceptable; Figure 1F). Independently linked to shorter TNT were PMDD of T and D, in addition to the baseline features of high-risk GEP class, CA, and high LDH (Table 3). Achieving CR was a favorable event linked to longer TNT.

Table 3.

Variables linked to TNT

| Variable | n/N (%) | TNT from enrollment |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Univariate analysis | |||

| β2M > 5.5 mg/L | 65/303 (21) | 1.67 (1.09, 2.56) | .018 |

| Creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL | 23/303 (8) | 1.90 (1.04, 3.45) | .036 |

| Hb < 10 g/dL | 94/303 (31) | 1.55 (1.06, 2.27) | .025 |

| LDH ≥ 190 U/L | 81/303 (27) | 2.05 (1.39, 3.02) | < .001 |

| Cytogenetic abnormalities | 100/302 (33) | 2.40 (1.66, 3.48) | < .001 |

| GEP high-risk | 40/275 (15) | 2.74 (1.71, 4.40) | < .001 |

| GEP proliferation subgroup | 27/275 (10) | 2.05 (1.17, 3.59) | .013 |

| GEP NR3C1 bottom tertile | 91/274 (33) | 1.07 (0.71, 1.60) | .747 |

| GEP NR3C1 top tertile | 91/274 (33) | 0.77 (0.51, 1.15) | .202 |

| Completed transplantation 2* | — | 0.64 (0.38, 1.09) | .102 |

| Completed consolidation 1* | — | 0.82 (0.48, 1.37) | .444 |

| Completed consolidation 2* | — | 1.02 (0.62, 1.66) | .946 |

| Bortezomib during induction (mg)* | — | 0.94 (0.86, 1.02) | .133 |

| Bortezomib during consolidation (mg)* | — | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | .397 |

| Bortezomib during maintenance (mg)* | — | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) | .136 |

| Dexamethasone during induction (dg)* | — | 0.77 (0.62, 0.96) | .022 |

| Dexamethasone during transplantation (dg)* | — | 0.92 (0.85, 0.99) | .034 |

| Dexamethasone during consolidation (dg)* | — | 0.95 (0.90, 1.02) | .148 |

| Dexamethasone during maintenance (dg)* | — | 0.98 (0.95, 1.00) | .060 |

| Thalidomide during induction (g)* | — | 0.84 (0.64, 1.12) | .232 |

| Thalidomide during transplantation (g)* | — | 1.02 (0.96, 1.07) | .517 |

| Thalidomide during consolidation (g)* | — | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | .458 |

| Thalidomide during maintenance (g)* | — | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | .407 |

| Premature bortezomib discontinuation* | — | 8.57 (5.09, 14.42) | < .001 |

| Premature dexamethasone discontinuation* | — | 8.16 (4.81, 13.86) | < .001 |

| Premature thalidomide discontinuation* | — | 8.52 (4.98, 14.57) | < .001 |

| Achieved CR* | — | 0.47 (0.32, 0.69) | < .001 |

| Achieved CR before Tx2* | — | 0.67 (0.41, 1.10) | .113 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||

| LDH ≥ 190 U/L | 74/275 (27) | 1.62 (1.05, 2.49) | .028 |

| Cytogenetic abnormalities | 95/275 (35) | 2.16 (1.42, 3.29) | < .001 |

| GEP high-risk | 40/275 (15) | 1.74 (1.07, 2.85) | .027 |

| Premature dexamethasone discontinuation* | — | 2.47 (1.02, 5.98) | .046 |

| Premature thalidomide discontinuation* | — | 4.04 (1.66, 9.81) | .002 |

| Achieved CR* | — | 0.45 (0.29, 0.68) | < .001 |

Analyses were performed of cumulative doses per protocol step (induction, peritransplantation, consolidation, and maintenance). The multivariate model uses stepwise selection with entry level of 0.1 and variable remains if it meets the 0.05 level. Variables considered univariately were: age ≥ 65 years, female sex, white race, albumin < 3.5 g/dL, B2M ≥ 3.5 mg/L, B2M > 5.5 mg/L, creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL, CRP ≥ 8 mg/L, Hb < 10 g/dL, LDH ≥ 190 U/L, cytogenetic abnormalities (anytime before enrollment), GEP high-risk, GEP CD-1 subgroup, GEP CD-2 subgroup, GEP hyperdiploidy subgroup, GEP low bone disease subgroup, GEP MAF/MAFB subgroup, GEP MMSET/FGFR3 subgroup, GEP myeloid subgroup, GEP proliferation subgroup, GEP TP53 deletion, GEP NR3C1 bottom tertile, GEP NR3C1 top tertile, completed transplantation 2*, completed consolidation 1*, completed consolidation 2*, bortezomib during induction*, bortezomib during consolidation*, bortezomib during maintenance*, dexamethasone during induction*, dexamethasone during transplantation*, dexamethasone during consolidation*, dexamethasone during maintenance*, thalidomide during induction*, thalidomide during transplantation*, thalidomide during consolidation*, thalidomide during maintenance*, premature bortezomib discontinuation*, premature dexamethasone discontinuation*, premature thalidomide discontinuation*, achieved CR*, and achieved CR before Tx2*. Variables considered for the multivariate model were: B2M > 5.5 mg/L, creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL, Hb < 10 g/dL, LDH ≥ 190 U/L, cytogenetic abnormalities (anytime before enrollment), GEP high-risk, GEP proliferation subgroup, dexamethasone during induction*, dexamethasone during transplant*, premature bortezomib discontinuation*, premature dexamethasone discontinuation*, premature thalidomide discontinuation* and achieved CR*.

B2M indicates B2-microglobulin; CRP, C-reactive protein; Hb, hemoglobin; and —, not applicable.

Variable was treated as a time-dependent variable.

As upfront use of all myeloma-active treatment ingredients might adversely affect PRS, this endpoint was also examined in the context of VTD dosing (Table 4). Of many variables examined that encompass baseline and relapse characteristics, duration of initial disease control as well as VTD dosing and PMDD, adverse impact on PRS was independently linked to PR subgroup designation before therapy, female gender, and progression within 2 years of starting protocol therapy. PRS was not affected by dosing of any of the VTD components; indeed, univariately, a higher V dose was associated with longer PRS.

Table 4.

Variables associated with postrelapse survival

| Variable | n/N (%) | PRS from first relapse |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Univariate | |||

| Female | 20/51 (39) | 2.31 (1.19, 4.50) | .014 |

| Cytogenetic abnormalities at baseline | 25/50 (50) | 3.56 (1.71, 7.44) | < .001 |

| Baseline GEP MMSET/FGFR3 subgroup | 10/47 (21) | 0.37 (0.14, 0.98) | .045 |

| Baseline GEP proliferation subgroup | 11/47 (23) | 3.15 (1.37, 7.25) | .007 |

| Relapse β2M ≥ 3.5 mg/L | 15/44 (34) | 2.30 (1.13, 4.67) | .021 |

| Cytogenetic abnormalities at relapse | 20/41 (49) | 3.28 (1.50, 7.18) | .003 |

| Relapse GEP high-risk | 13/22 (59) | 4.23 (1.17, 15.29) | .028 |

| Completed transplantation 2 | 37/51 (73) | 1.31 (0.63, 2.74) | .466 |

| Completed consolidation 1 | 33/51 (65) | 0.65 (0.33, 1.26) | .204 |

| Completed consolidation 2 | 28/51 (55) | 0.52 (0.27, 0.99) | .047 |

| Total bortezomib on study (cg) | N = 51 | 0.94 (0.89, 1.00) | .035 |

| Total dexamethasone on study (cg) | N = 51 | 0.89 (0.73, 1.09) | .255 |

| Total thalidomide on study (cg) | N = 51 | 0.92 (0.81, 1.05) | .208 |

| Progression within 2 years of enrollment | 24/51 (47) | 2.80 (1.43, 5.47) | .003 |

| Premature bortezomib discontinuation (before relapse) | 20/51 (39) | 0.76 (0.39, 1.51) | .438 |

| Premature dexamethasone discontinuation (before relapse) | 17/51 (33) | 0.63 (0.30, 1.30) | .208 |

| Premature thalidomide discontinuation (before relapse) | 18/51 (35) | 0.66 (0.33, 1.35) | .255 |

| Started salvage therapy*** | 0.77 (0.34, 1.73) | .526 | |

| Received salvage transplant*** | 2.07 (1.02, 4.17) | .043 | |

| Multivariate | |||

| Female | 12/35 (34) | 6.62 (2.45, 17.86) | < .001 |

| Baseline GEP proliferation subgroup | 11/35 (31) | 3.69 (1.35, 10.09) | .011 |

| Progression within 2 years of enrollment | 18/35 (51) | 2.84 (1.19, 6.80) | .019 |

Variables considered univariately were: age ≥ 65 years at enrollment, female sex, white race, baseline albumin < 3.5 g/dL, baseline B2M ≥ 3.5 mg/L, baseline B2M > 5.5 mg/L, baseline creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL, baseline CRP ≥ 8 mg/L, baseline Hb < 10 g/dL, baseline LDH ≥ 190 U/L, cytogenetic abnormalities anytime prior to enrollment, baseline GEP high-risk, baseline GEP CD-1 subgroup, baseline GEP CD-2 subgroup, baseline GEP HY subgroup, baseline GEP LB subgroup, baseline GEP MF subgroup, baseline GEP MS subgroup, baseline GEP MY subgroup, baseline GEP PR subgroup, baseline GEP NR3C1 lower tertile, baseline GEP NR3C1 upper tertile, relapse albumin < 3.5 g/dL, relapse B2M ≥ 3.5 mg/L, relapse B2M > 5.5 mg/L, relapse creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL, relapse Hb < 10 g/dL, relapse LDH ≥ 190 U/L, cytogenetic abnormalities within 45 days of relapse, relapse GEP high-risk, relapse GEP CD-1 subgroup, relapse GEP CD-2 subgroup, relapse GEP HY subgroup, relapse GEP LB subgroup, relapse GEP MF subgroup, relapse GEP MS subgroup, relapse GEP MY subgroup, relapse GEP PR subgroup, relapse GEP NR3C1 lower tertile, relapse GEP NR3C1 upper tertile, completed transplant 2, completed consolidation 1, completed consolidation 2, total bortezomib on study (cg), total dexamethasone on study (cg), total thalidomide on study (cg), progression within 1 year of enrollment, progression within 2 years of enrollment, premature bortezomib discontinuation (before relapse), premature dexamethasone discontinuation (before relapse), premature thalidomide discontinuation (before relapse), started salvage therapy***, received salvage transplant***. Variables considered for the multivariate model without relapse parameters were: female sex, cytogenetic abnormalities anytime prior to enrollment, baseline GEP MS subgroup, baseline GEP PR subgroup, completed consolidation 2, total bortezomib on study (cg), progression within 2 years of enrollment, received salvage transplant***.

HR indicates hazard ratio; and 95% Cl, 95% confidence interval.

P value from Wald χ2 test in Cox regression multivariate model uses stepwise selection with entry level 0.1 and variable remains if meets the 0.05 level.

Discussion

Maintaining remission in the melphalan-prednisone era with melphalan-prednisone was deemed to be ineffective, as patients had comparable OS whether they were maintained on this regimen or treatment was suspended and reintroduced at the time of recurrence.17 The value of interferon-based maintenance18 could not be validated with longer follow-up or in subsequent randomized trials.19,20 The Southwest Oncology Group reported that the addition of prednisone to interferon prolonged progression-free survival but not OS.21 A subsequent trial by the same group noted that a higher prednisone dose of 50 mg versus 10 mg applied on an alternating-day schedule significantly extended both progression-free survival and OS in responding patients.22 In the novel agent era, ushered in with the discovery of thalidomide's activity in advanced and refractory MM,23,24 such immunomodulatory therapy was also evaluated as maintenance strategy, mostly in low doses after transplantation, with favorable results.25–27 In contrast, TT2 used thalidomide from the outset of treatment.3 Despite drug discontinuation resulting from cumulative toxicity in approximately 80% of patients 2 years into protocol therapy, an OS benefit was first detected in patients exhibiting CA.28 For the entire population, Kaplan-Meier survival plots began to segregate at year 6 and reached statistical significance in favor of the thalidomide arm only at 10 years.29 Toward improving treatment compliance, we shortened induction and consolidation therapies in TT3 to 2 cycles from 4 cycles in TT2, resulting in superior outcomes that were attributable both to the addition of bortezomib in TT3 and to a higher proportion of patients completing the intended therapies.6

Here we investigated the cumulative impact on clinical outcomes of 3 agents applied from the onset of protocol therapy and extended into maintenance. By using time-dependent variable methodology, all patients could be considered for the analysis.30 OS and EFS were both favorably affected by V, T, and D dosing during most protocol phases. PMDD of all 3 agents conferred shorter OS, EFS, and TNT in univariate models, of which V retained independent significance for OS and both T and D for TNT. These results attest to the clinical benefit of sustained VTD dosing. TT3 successor trial 2006-66 extended V dosing to all 3 years of maintenance and substituted lenalidomide (R) for T.31 This practice continues in currently accruing Total Therapies 4 and 5 protocols for low- and high-risk MM, respectively. High-risk GEP designation, the presence of CA, and elevated levels of LDH and creatinine were confirmed as independently conferring shorter OS and EFS. Although contributing to higher CR frequency, dosing of VTD components did not impact CRD.

The prognostic implications of D dosing provided the rationale for examining whether the expression level of the glucocorticoid receptor gene, NR3C1, played a role in mediating the observed dosing effects and whether such effects were limited to D as its pharmacologic ligand. Interestingly, top-tertile NR3C1 levels were associated with superior, and bottom-tertile levels with inferior, survival outcomes. These findings are consistent with favorable survival outcomes linked to gains of chromosome 5q31.3 where NR3C1 resides.32 Importantly, D dosing in induction extended OS and EFS significantly only when NR3C1 expression was low; a dosing trend was observed in mid-tertile and no dosing effect in top-tertile cases. Thus, D dosing may overcome otherwise unfavorable survival effects associated with low NR3C1 expression, perhaps by way of D-induced up-regulation of NR3C1 within 48 hours of D test dosing, which we had shown to improve survival in TT2.33 The NR3C1 expression dependency of D's dosing effect on survival extended to T but not to V dosing, suggesting a commonality of pathways by which both D and T interact with myeloma cells.

An unexpected finding was the observation that PRS was not adversely affected by VTD dosing, arguing in favor of using myeloma-effective agents up-front and in sufficient intensity. The sustained profound PRS-adverse impact of PR designation at baseline is consistent with tumor proliferation facilitating the acquisition of further mutations with their adverse consequences for disease control.

The beneficial effects of higher cumulative dosing of components of the VTD regimen may be the result not only of their direct tumor cell–inactivating properties but also of favorable alterations of the bone marrow microenvironment that all 3 agents have been shown to target.34 Such investigations are currently in progress, as we are examining serial GEP data on both highly purified plasma cells and whole bone marrow biopsies.35 As data mature from a TT3 successor protocol 2006-66, using VRD for all 3 years,31 we will be able to determine whether survival can be improved beyond 2003-33 results by extending V maintenance from 1 to 3 years, while additionally decreasing the frequency of PMDD by substituting R for T. Recent reports of several randomized trials attested to R's ability to delay disease progression.36–38 The link to age of PMDD emphasizes the need for early dose reduction in the elderly for maintenance benefits to be realized. This objective seems feasible with the currently applied VRD maintenance schedule, calling for once weekly administration of V at 1.0 mg/m2 together with D at 12 to 20 mg and R at 15 mg daily for 21 of 28 days.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD (CA 55813).

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: F.v.R. and B.B. conceptualized work and wrote the paper; F.v.R., E.A., B.N., S.W., Y.A., and B.B. contributed patients and performed clinical research; N.P. supervised data collection and assured accuracy; J.D.S. supervised and discussed gene expression profiling analyses; and J.S., A.H., and J.C. performed statistical analyses.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Bart Barlogie, Myeloma Institute for Research and Therapy, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 West Markham St, Little Rock, AR 72205; e-mail: barlogiebart@uams.edu.

References

- 1.Barlogie B, Anaissie E, van Rhee F, et al. Incorporating bortezomib into upfront treatment for multiple myeloma: early results of total therapy 3. Br J Haematol. 2007;138(2):176–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Rhee F, Bolejack V, Hollmig K, et al. High serum-free light chain levels and their rapid reduction in response to therapy define an aggressive multiple myeloma subtype with poor prognosis. Blood. 2007;110(3):827–832. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-067728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barlogie B, Tricot G, Anaissie E, et al. Thalidomide and hematopoietic-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(10):1021–1030. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaughnessy J, Zhan F, Burington B, et al. A validated gene expression model of high-risk multiple myeloma is defined by deregulated expression of genes mapping to chromosome I. Blood. 2007;109(6):2276–2284. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-038430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pineda-Roman M, Zangari M, Haessler J, et al. Sustained complete remissions in multiple myeloma linked to bortezomib in total therapy 3: comparison with total therapy 2. Br J Haematol. 2008;140(6):625–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06921.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barlogie B, Haessler J, Pineda-Roman M, et al. Completion of pre-maintenance phases in total therapies 2 and 3 improves clinical outcomes in multiple myeloma: an important variable to be considered in clinical trial designs. Cancer. 2008;112(12):2720–2725. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhan F, Hardin J, Kordsmeier B, et al. Global gene expression profiling of multiple myeloma, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and normal bone marrow plasma cells. Blood. 2002;99(5):1745–1757. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhan F, Huang Y, Colla S, et al. The molecular classification of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108(6):2020–2028. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-013458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiong W, Wu X, Starnes S, et al. An analysis of the clinical and biologic significance of TP53 loss and the identification of potential novel transcriptional targets of TP53 in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;112(10):4235–4246. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-119123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaughnessy JD, Zhou Y, Haessler J, et al. TP53 deletion is not an adverse feature in multiple myeloma treated with total therapy 3. Br J Haematol. 2009;147(3):347–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07864.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blade J, Samson D, Reece D, et al. Criteria for evaluating disease response and progression in patients with multiple myeloma treated by high-dose therapy and haemopoietic stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol. 1998;102(5):1115–1123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durie BGM, Harousseau J-L, Miguel JS, et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2006;20(9):1467–1473. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barlogie B, Alexanian R, Pershouse M, Smallwood L, Smith L. Cytoplasmic immunoglobulin content in multiple myeloma. J Clin Invest. 1985;76(2):765–769. doi: 10.1172/JCI112033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox DR. Regression tables and life tables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexanian R, Balzerzac S, Haut A, et al. Remission maintenance therapy for multiple myeloma. Arch Intern Med. 1975;135(1):147–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandelli F, Avvisati G, Amadori S, et al. Maintenance treatment with recombinant interferon alfa-2b in patients with multiple myeloma responding to conventional induction chemotherapy. N Eng J Med. 1990;322(20):1430–1434. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005173222005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myeloma Trialists' Collaborative Group. Interferon as therapy for multiple myeloma: an individual patient data overview of 24 randomized trials and 4012 patients. Br J Haematol. 2001;113(4):1020–1034. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fritz E, Ludwig H. Interferon-alpha treatment in multiple myeloma: meta-analysis of 30 randomised trials among 3948 patients. Ann Oncol. 2000;11(11):1427–1436. doi: 10.1023/a:1026548226770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salmon SE, Crowley JJ, Balcerzak SP, et al. Interferon versus interferon plus prednisone remission maintenance therapy for multiple myeloma: a Southwest Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(3):890–896. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.3.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berenson JR, Crowley JJ, Morgan TM, et al. Maintenance therapy with alternating-day prednisone improves survival in multiple myeloma patients. Blood. 2002;99(9):3163–3168. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.9.3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singhal S, Mehta J, Desikan R, et al. Antitumor activity of thalidomide in refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(21):1565–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911183412102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barlogie B, Desikan R, Eddlemon P, et al. Extended survival in advanced and refractory multiple myeloma after single agent thalidomide: identification of prognostic factors in a phase 2 study of 169 patieints. Blood. 2001;98(2):492–494. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.2.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Attal M, Harousseau JL, Leyvraz S, et al. Maintenance therapy with thalidomide improves survival in multiple myeloma patients. Blood. 2006;108(10):3289–3294. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-022962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdelkefi A, Ladeb S, Torjman L, et al. Single autologous stem-cell transplantation followed by maintenance therapy with thalidomide is superior to double autologous transplantation in multiple myeloma: results of a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Blood. 2008;111(4):1805–1810. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-101212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spencer A, Prince HM, Roberts AW, et al. Consolidation therapy with low-dose thalidomide and prednisolone prolongs the survival of multiple myeloma patients undergoing a single autologous stem-cell transplantation procedure. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(11):1788–1793. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.8573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barlogie B, Pineda-Roman M, van Rhee F, et al. Thalidomide arm of Total Therapy 2 improves complete remission duration and survival in myeloma patients with metaphase cytogenetic abnormalities. Blood. 2008;112(8):3115–3121. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-145235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barlogie B, Attal M, Crowley J, et al. Long-term follow-up of autotransplant trials for multiple myeloma: update of protocols conducted by the Intergroupe Francophone Du Myelome, Southwest Oncology Group, and University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1209–1214. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoering A, Crowley J, Shaughnessy JD, Jr, et al. Complete remission in multiple myeloma examined as time-dependent variable in terms of both onset and duration in Total Therapy protocols. Blood. 2009;114(7):1299–1305. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nair B, van Rhee F, Shaughnessy JD, Jr, et al. Superior results of Total Therapy 3 (2003-33) in gene expression profiling-defined low-risk multiple myeloma confirmed in subsequent trial 2006-66 with bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone (VRD) maintenance. Blood. 2010;115(21):4168–4173. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-255620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Avet-Loiseau H, Li C, Magrangeas F, et al. Prognostic significance of copy-number alterations in multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(27):4585–4590. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burington B, Barlogie B, Zhan F, Crowley J, Shaughnessy JD., Jr Tumor cell gene expression changes following short-term in vivo exposure to single agent chemotherapeutics are related to survival in multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(15):4821–4829. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Tonon G, Richardson PG, Anderson KC. Understanding multiple myeloma pathogenesis in the bone marrow to identify new therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(8):585–598. doi: 10.1038/nrc2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaughnessy J, Zhan F, Kordsmeier B, Tian E, Smith R, Barlogie B. Gene expression profiling of the bone marrow microenvironment in patients with multiple myeloma, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and normal healthy donors [abstract]. Blood. 2002;100:382a. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1745. Abstract 382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Attal M, Harousseau JL, Marit G, et al. Lenalidomide after autologous transplantation for myeloma: first analysis of a prospective randomized study of the Intergroupe Francophone Du Myelome (IFM 2005 02) [abstract]. Blood. 2009;114(Abstract 529) [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCarthy PL, Owzar K, Stadtmauer EA, et al. Phase III Intergroup Study of Lenalidomide (CC-5013) versus placebo maintenance following single autologous stem cell transplant for multiple myeloma (CALGB 100104): initial report of patient accrual and adverse events [abstract]. Blood. 2009;114 Abstract 3416. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gay F, Falco P, Crippa C, et al. Sequential approach with bortezomib as induction before autologous transplantation, followed by lenalidomide as consolidation-maintenance in untreated multiple myeloma [abstract]. Blood. 2009;114 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.7561. Abstract 3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]