Abstract

The olfactory epithelium maintains stem and progenitor cells that support the neuroepithelium’s life-long capacity to reconstitute after injury. However, the identity of the stem cells – and their regulation – remain poorly defined. The transcription factors Pax6 and Sox2 are characteristic of stem cells in many tissues, including the brain. Therefore, we assessed the expression of Pax6 and Sox2 in normal olfactory epithelium and during epithelial regeneration after methyl bromide lesion or olfactory bulbectomy. Sox2 is found in multiple kinds of cells in normal epithelium, including sustentacular cells, horizontal basal cells, and some globose basal cells. Pax6 is co-expressed with Sox2 in all these, but is also found in duct/gland cells as well as olfactory neurons that innervate necklace glomeruli. Most of the Sox2/Pax6-positive globose basal cells are actively cycling, but some express the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1, and are presumably mitotically quiescent. Among globose basal cells, Sox2 and Pax6 are co-expressed by putatively multipotent progenitors (labeled by neither anti-Mash1 nor anti-Neurog1) and neuron-committed transit amplifying cells (which express Mash1). However, Sox2 and Pax6 are expressed by only a minority of immediate neuronal precursors (Neurog1- and NeuroD1-expressing). The assignment of Sox2 and Pax6 to these categories of globose basal cells is confirmed by a temporal analysis of transcription factor expression during the recovery of the epithelium from methyl bromide-induced injury. Each of the Sox2/Pax6-colabeled cell types is at a remove from the birth of neurons; thus, suppressing their differentiation may be among the roles of Sox2/Pax6 in the olfactory epithelium.

Keywords: tissue stem cells, transcription factors, neural injury, neural regeneration

Direct contact with the external environment makes the olfactory epithelium (OE) vulnerable to various forms of damage. It is fortunate, then, that the OE retains an inherent life-long capacity to reconstitute itself after lesion, and restore to normal or near-normal the populations of neurons, sustentacular cells (Sus), duct cells, gland cells, etc. from spared cells within the OE and/or the lamina propria (Cancalon, 1982; Graziadei and Monti Graziadei, 1979; Matulionis, 1976; Monti Graziadei and Graziadei, 1979; Mulvaney, 1971; Schwob et al., 1995). The capacity to regenerate the neurons of the epithelium most likely reflects the persistence of neurocompetent stem cells within the olfactory tissue. However, the question of which cell type(s) are stem cells, i.e., capable of giving rise to all the different kinds of epithelial cells and of renewing themselves, remains unanswered. Among the cell types of the OE, three candidates have been proffered as putative stem cell elements: globose basal cells (GBCs), horizontal basal cells (HBCs), and Bowman’s duct cells (Chen et al., 2004; Leung and Reed, 2007; Matulionis, 1975). The morphologically undifferentiated GBCs are mitotically active in the normal mucosa and some, at least, proliferate to an enhanced degree after various forms of damage that elicit either selective regeneration of the neuronal population or reconstitution of the OE as a whole (Graziadei and Monti Graziadei, 1979; Huard and Schwob, 1995; Monti Graziadei and Graziadei, 1979).

Data from our laboratory suggest that the GBCs are a functionally heterogeneous cell population (Chen et al., 2004; Goldstein et al., 1998; Huard et al., 1998; Jang et al., 2007; Manglapus et al., 2004). That the proximate neuronal progenitors, i.e., cells that give rise directly to the neurons of the olfactory epithelium, are among the GBCs is well-established by lineage analysis and by targeted inactivation of neurogenic genes expressed exclusively by GBCs, including Mash1 and Neurog1(Caggiano et al., 1994; Cau et al., 2002; Cau et al., 1997; Schwob et al., 1994). More recent findings have emphasized the broader-than-neuronal potency of GBC progenitors, which is made manifest at times when multiple epithelial cell types need to be regenerated. FACS-purified GBCs from normal OE engraft and give rise to GBCs, neurons, Sus cells, gland/duct cells, and respiratory epithelial (RE) cells following transplantation into the methyl bromide (MeBr)-lesioned OE (Chen et al., 2004; Goldstein et al., 1998; Huard et al., 1998; Jang et al., 2007; Manglapus et al., 2004). Included among the multipotent GBCs are ones that are proliferating at the time they are harvested from the normal OE, an exclusively neurogenic environment (Chen et al., 2004; Goldstein et al., 1998). Thus, the conventionally defined population of GBCs harbors multipotent progenitor cells as a subgroup amongst them, even in settings, e.g., the unlesioned OE in a laboratory environment, where that capacity is not actively called upon. In contrast, FACS-purified HBCs and Sus/duct/gland cells from the normal OE give no evidence of multipotency in the same assay (Chen et al., 2004), although HBCs become multipotent after epithelial damage as shown by lineage analysis in situ or when activation is followed by transplantation (Leung and Reed, 2007; A.I. Packard and J.E. Schwob, unpublished results). Furthermore, among the GBCs are a small subpopulation that show a kinetic feature of tissue stem cells: the retention of thymidine label for a prolonged period, re-entry into the mitotic cycle following lesion, and the return to label retention during recovery after injury (Chen and Schwob, 2003).

The varieties of clone types arising from single GBCs, which range in composition from neuron-only to Sus-only or any kind of mixture of these and other epithelial cells types, as well as the presence of long-term label-retaining GBCs suggest that the GBC population is heterogeneous with respect to differentiation capacity. Moreover, these data indicating functional heterogeneity within the GBC population are paralleled by studies on the expression of members of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family of transcription factors in the normal and MeBr-lesioned OE. On the basis of the temporal pattern post-lesion, the expression of Hes1 gene and protein by GBCs seems to be associated with a commitment to make Sus cells, while the later appearance of Mash1 and then Neurog1 and NeuroD1 mRNAs imply commitment to the production of replacement neurons (Manglapus et al., 2004). The timing and evolution of bHLH transcription factor expression after lesion also indicates that the truly multipotent GBCs express none of these transcription factors, since multipotent progenitors are characteristic of the epithelium at 1 and 2 d after MeBr lesion as shown by transplantation of cells harvested at that time and by retroviral lineage tracing (Goldstein et al., 1997; Huard et al., 1998).

In an effort to characterize the neurocompetent stem cells and multipotent progenitor (MPP) cells among the GBCs, we have assayed for the expression of a pair of transcription factors, Sox2 and Pax6, which function, often together, at multiple levels in the development of an embryo: the specification of morphogenetic fields (e.g., olfactory placode and the retina), the regulation of stem cells and multipotent progenitor cells (e.g., in the CNS), and the elaboration of phenotypic properties of terminally differentiated cells (e.g., δ1-crystallin gene expression in the developing lens) (Chi and Epstein, 2002; Kondoh et al., 2004; Mansouri et al., 1994; Osumi et al., 2008; Pevny and Placzek, 2005; Wegner and Stolt, 2005).

Sox2 contains a high-mobility-group (HMG) DNA-binding domain and is one of the key factors in regulating embryonic stem cell self-renewal and inducing somatic cells to become pluripotent stem cells (Pevny and Lovell-Badge, 1997; Pevny and Placzek, 2005; Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006). In the CNS, Sox2 expression persists in multipotent neural stem cells from the embryo into the adult, as shown by the expression of eGFP inserted into the Sox2 locus, and therefore may provide a marker for identifying and isolating stem cells (Brazel et al., 2005; Pevny and Placzek, 2005). The expression pattern and possible function(s) of Sox2 in adult olfactory epithelium are largely unknown.

Pax6 contains two DNA binding motifs (a paired-domain and a homeodomain) and regulates multipotent progenitor cells in diverse systems, including the forebrain and retina among the various structures of the CNS(Walther et al., 1991). Down-regulation of Pax6 is associated with the differentiation of radial glia in SVZ (Gotz et al., 1998), and disruption of Pax6 leads to the loss of multipotency in retinal progenitor cells (RPCs) (Marquardt et al., 2001). In homozygous Pax6 mutant animals, the structures of the nose fail to form, indicating that Pax6 is involved in olfactory development as well (Collinson et al., 2003). Pax6 is known to be expressed in the adult OE, but its expression pattern was described as limited to cells of non-neuronal lineages, including HBCs and Sus cells and cells of Bowman's glands and ducts (Davis and Reed, 1996). The function(s) of Pax6 in adult OE have not been subject to detailed study.

Given their roles in stem and progenitor cells elsewhere in the nervous system, we examined the expression patterns of Sox2 and Pax6 in normal OE and during its regeneration following epithelial lesion caused by MeBr inhalation (Schwob et al., 1995). Our analyses demonstrate that Sox2 and Pax6 are expressed by a variety of cell types in the normal and lesioned-regenerating OE. Indeed, we find that both transcription factors are intensely expressed in sustentacular cells and at a lower level in HBCs. However, in contrast to a previous report (Davis and Reed, 1996), we demonstrate here that some GBCs express both Sox2 and Pax6. Most of the Sox2/Pax6 (+) GBCs are proliferating, but some appear to be in cell cycle arrest. With reference to the different functional categories of GBCs, direct demonstration and the temporal pattern of Sox2/Pax6 labeling after MeBr lesion indicate that the two transcription factors are expressed in presumptive multipotent GBCs and Mash1 (+) GBCs (commonly held to be committed to the neuronal lineage), but only a small subset of Neurog1 (+) cells (presumed immediate neuronal progenitors). Thus, Sox2 and Pax6 are expressed by GBCs with the characteristics of stem cells and MPPs, but do not apparently proscribe commitment to neuronal fate, judging by co-expression of Mash1. Accordingly, Sox2 and Pax6 may play multiple and complex roles in the regulation of olfactory neurogenesis, rather than maintaining multipotency, per se.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Taconic, Germantown, NY) weighing 200–250 g were maintained on ad libitum rat chow and water. All animals were housed in a heat- and humidity-controlled, AALAC-accredited vivarium operating under a 12:12-hour light-dark cycle. Rats were acclimated for a minimum of 1 week prior to use and then lesioned at a body weight of 225–275 g. Male C57Bl/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were maintained on on ad libitum rat chow and water and used at 12 weeks of age. The ΔNeurog1-eGFP mice were obtained from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Centers and were produced for the GENSAT project as described (Gong et al., 2002, 2003). Briefly, for the production of the ΔNeurog1-eGFP mice, BAC clone RP23-457E22 (containing the coding region for neurog1) was modified via a two–step BAC modification procedure, resulting in the insertion of eGFP-polyadenylation sequence immediately 3’ of the start codon of the neurog1 gene. The modified BAC clone containing eGFP-PA inserted immediately after the start codon of neurog1 is then purified and injected into pronuclei of fertilized oocytes of FVB/N mice. Transgenic founders are identified by PCR for the GFP transgene. All our use of vertebrate animals was approved by the Committee for the Humane Use of Animals at Tufts University School of Medicine, where the animals were housed and experiments were conducted.

MeBr lesion

Unilateral MeBr exposure was accomplished by reversible closure of the rat’s left naris, as described previously (Iwema et al., 2004). In brief, on the day prior to MeBr exposure, rats were anesthetized by inhalation of isofluorane, and the right naris was closed by applying cyanoacrylate glue in and around the opening of the naris before and after placing a single stitch with 5-0 silk. On the following day, unanesthetized rats were placed in a wire enclosure centered in a Plexiglas box and exposed to MeBr for 6 hours at a concentration of 330 ppm in purified air at a flow rate of 10 liters/minute. The day after the exposure to MeBr the stitch and the superglue plug were removed following mild sedation by inhalation of isofluorane. Rats were allowed to survive for 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 or 14 days post- MeBr lesion. Time points after MeBr lesion were chosen on the basis of previously reported changes in basal cell proliferation rate and re-emergence of the various cell types (Manglapus et al., 2004; Schwob et al., 1995). MeBr-exposed animals show no evidence of discomfort as a consequence of the lesion; they eat and drink and are active to the same degree as unlesioned animals.

Olfactory bulbectomy

The right olfactory bulb of adult rats or mice was ablated by aspiration according to our usual surgical protocol following the induction of surgical anesthesia by injection of a cocktail of ketamine (26 mg/kg), xylazine (5.4 mg/kg) and acepromazine (1 mg/kg) (Schwob et al., 1992). Rats were allowed to survive for 3, 7, 10 or 21 days after bulbectomy. Mice survived for 21 days after bulbectomy.

Tissue harvest

Age-matched unlesioned, MeBr-lesioned, and bulbectomized rats and unlesioned or bulbectomized mice at the end of the prescribed survival times were deeply anesthetized by injection of a cocktail of ketamine (52 mg/kg), xylazine (10.8 mg/kg) and acepromazine (2 mg/kg) and then euthanized by perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.05 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2. After perfusion, the head was stripped of soft tissue and the heavy bones of the skull were removed; the nasal skeleton and mucosa were postfixed for additional 4 hours. Tissues were then rinsed with PBS, cyroprotected in 30% sucrose in PBS overnight (without decalcification), and frozen in OCT compound (Miles Inc., Elkhart, IN). The olfactory mucosa was sectioned on a cryostat (Reichert-Jung 2800 Frigocut) in the coronal plane; 5–12 µm sections were collected on to "Plus" slides (Fisher Scientific) and stored at −20°C for future use.

Immunohistochemistry

Standard laboratory protocols were employed for detecting Sox2 and Pax6 expression in normal OE and during epithelial regeneration post-MeBr lesion and comparing it with known markers of different epithelial cell types (Table 1) (Jang et al., 2007). Adequate labeling for Sox2 or Pax6 either alone or in combination requires a set of treatments on the sections prior to incubation with the antibodies. Briefly, frozen sections were rinsed in PBS for 5 minutes to remove the OCT, puddled with 0.01 M citric acid buffer (pH 6.0), and then placed in a commercial food steamer containing water in its reservoir heated to 90°C for 15 minutes (which we term “steaming”). After cooling, sections were rinsed with PBS briefly before incubating with blocking solution (10% serum + 5% Non fat dry milk + 4% BSA + 0.01% Triton X-100) for 30 minutes at room temperature. The analyses conducted here depended on a number of double and triple-immunohistochemical staining approaches (Table 2). In all cases, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Bound primary antibodies were visualized either by incubation with the corresponding biotinylated secondary antibody followed by avidin-bHRP conjugate (Elite ABC Kit, Vector Laboratory, Burlingame, CA) and then 3, 3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as chromogen, or with one of several fluorescently-conjugated secondary antibodies for purposes of co-localization by double and/or triple labeling. On occasion, tyramide signal amplification was utilized to enhance a weak signal or permit staining with two antibodies from the same species, and used according to kit instructions (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

Table 1.

Primary antibodies used in the study

| Primary antibody (alpha by immunogen) |

Source and catalog number |

Immunogen and preparation |

|---|---|---|

| Goat α−CD54 | R&D systems, AF583 | Recombinant extracellular domain from rat, affinity- purified (Accession number Q00238: amino acid residues Q28 - T493) |

| Mouse α−CK14 | Vector, VP-C410 | Synthetic peptide corresponding to C-terminus of human cytokeratin14 (GKVVSTHEQVLRTKN), conjugated to thyroglobulin |

| Goat α−FITC | Invitrogen (Molecular Probes), A-11095 |

FITC-conjugated to KLH, affinity-purified serum |

| Mouse α−FITC | Jackson Immunores., 200- 002-037 |

FITC-conjugated to KLH, monoclonal antibody chromatographically purified from ascites |

| Rabbit α−FITC | Zymed/Invitrogen, 71-1900 | FITC-conjugated to KLH, affinity-purified serum |

| Chicken α−GFP | AbCam, ab13970 | Recombinant full-length eGFP |

| Rabbit α−GFP | AbCam, ab6556 | Recombinant full-length eGFP |

| Mouse α−Ki67 | BD-Biosciences, 556003 (clone B56) |

22 amino acid Ki-67 repeat motif (APKEKAQPLEDLASFQELSQ) |

| Mouse α−Mash1 | BD-Biosciences, 556604 (clone 24B72D11.1; Lo et al, 1991) |

Recombinant-full length rat MASH1 protein, affinity chromatography-purified |

| Goat α−NeuroD1 | Santa Cruz, sc-1086 | Peptide sequence near C-terminus of mouse NeuroD1 (GSIFSSGAAAPRCEIPIDNI) |

| Mouse α−Neurog1 | Santa Cruz, sc-19231 | Peptide sequence near N-terminus of mouse Neurog1 (ARLQPLASTSGLSVPARRSAK) |

| Mouse α−p27Kip1 | BD-Biosciences, 610241 (clone 57; Polyak et al, 1994) |

Recombinant-full length mouse p27Kip1 |

| Rabbit α−Pax6 | Chemicon, AB5409 | Peptide corresponding to C-terminus of mouse/rat/human Pax6 (QVPGSEPDMSQYWPRLQ), serum |

| Rabbit α−PGP9.5 | Cedarlane Laboratories Ltd., 31A3 (same as RA95101, Ultraclone) |

Purified human PGP9.5 protein (ubiquitin-C- terminal hydrolase 1, 27 kD) from brain |

| Goat α−Sox2 | Santa Cruz, sc-17320 | Peptide corresponding to amino acids 277-293 of human Sox2 (YLPGAEVPEPAAPSRLH), affinity- purified serum |

| Rabbit α−Sox2 | Chemicon, AB5603 | Peptide corresponding to amino acids 249-264 of human Sox2 (SSSPPVVTSSSHSRAP – identical to mouse), affinity-purified serum |

| Mouse α-TGFα, clone 213-4.4 |

Oncogene Science, MAb 213 |

Full-length recombinant TGFα, treated with paraformaldehyde. |

Table 2.

Immunohistochemical protocols used in the analysis

| IHC | Primary Antibody (Table 1) |

Secondary Antibody |

Tertiary Step |

Quaternary Step |

Pentanery Step |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sox2 | Sox2 (1:80) | b-DαG1,2 | ABC3→DAB4 | ||

| Pax6 | Pax6 (1:1200) | b-DαR1 | ABC→DAB | ||

| Mash1 | Mash1 (1:30) | b-DαM1 | ABC→DAB | ||

| Sox2 + CD54 |

Sox2 (1:80) | b-DαG | ABC→DAB | CD54 (1:100) | FITC-DαG1 |

| Pax6 + CD54 |

Pax6 (1:1200) + CD54 (1:100) |

b-DαR1 | ABC→DAB | FITC-DαG | |

| Sox2 + PGP9.5 |

Sox2 (1:500) + PGP9.5 (1:900) |

b-DαG + Alexa594- DαR1 |

TSA5→Alexa488-SA6 | ||

| Sox2 + Pax6 + CK14 |

Sox2 (1:80) + Pax6 (1:1200) + CK14 (1:100) |

FITC-DαR1 | Rabbit αFITC (1:100) | FITC-DαR + Alexa594-DαG1 + AMCA-DαM |

|

| Sox2 + Pax6 |

Sox2 (1:80) + Pax6 (1:1200) |

FITC-DαG1 + b-DαR |

Goat αFITC (1:50) | FITC-DαG | TSA→DAB |

| Ki67 + CD54 + Pax6 |

Ki67 (1:800) + CD54 (1:100) + Pax6 (1:10,000) |

FITC-DαM1 + AMCA-DαG1 + b-DαR |

Mouse αFITC (1:50) | FITC-DαM | TSA→ TxRd-SA6 |

| p27Kip1 + CD54 + Pax6 |

p27 (1:200) + CD54 (1:100) + Pax6 (1:10,000) |

FITC-DαM1 + AMCA-DαR1 + b-DαR |

Mouse αFITC | FITC-DαM | TSA→TxRd-SA |

| Mash1 + CD54 + Pax6 |

Mash1 (1:30) + CD54 (1:100) + Pax6 (1:10,000) |

FITC-DαM + AMCA-DαG + b-DαR |

Mouse αFITC | FITC-DαM | TSA→TxRd-SA |

| Neurog1 + Pax6 |

Neurog1 (1:80) + Pax6 (1:10,000) |

FITC-DαG + b-DαR |

Goat αFITC | FITC-DαG1 | TSA→TxRd-SA |

| Sox2 + GFP7 |

Sox2 (1:1000) + GFP (1:1500) |

b-DαG + Alexa488-DαR |

TSA→ Alexa594-SA | ||

| p27Kip1 + Mash1 |

p27 (1:200) + Mash1(1:200) |

b-DαM | FITC-DαM + TSA→Alexa594-SA6 |

Mouse αFITC (1:50) |

FITC-DαM (1:250) |

| p27Kip1 + NeuroD1 |

p27 (1:200) + NeuroD1 (1:200) |

FITC-DαM + b-DαG |

Mouse αFITC + TSA→Alexa594-SA |

Alexa488-DαM (1:250) |

FITC-DαM |

| Mab213 + Pax6 |

Mab213 ( 1:20) + Pax6 (1:300) |

TxRd-DαM + b-DαR |

FITC-SA5 |

Notes

b-DαG – biotinylated-donkey anti-goat IgG;

b-DαM – biotinylated-donkey anti-mouse IgG

b-DαR – biotinylated-donkey anti-rabbit IgG;

FITC-DαG – FITC-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG;

FITC-DαM – FITC-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG;

FITC-DαR – FITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG;

AMCA-DαG – AMCA-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG;

AMCA-DαR – AMCA-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG;

TxRd-DαM – TexasRed -conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG;

Alexa594-DαG – Alexa594-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG;

Alexa488-DαR – Alexa488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG

All secondary antibodies were used at a 1:50 dilution, except for Alexa594-DαG and Alexa488-DαR, which were used at 1:250.

ABC – Avidin (1:50)+ biotinylated horse radish peroxidase (1:50).

DAB – 3,3'-diaminobenzidine.

TSA – Tyramide Signal Amplification™ kit from Perkin-Elmer.

TxRd-SA – TexasRed™-conjugated streptavidin; Alexa594-SA – Alexa 594-conjugated streptavidin; FITC-SA – FITC-conjugated streptavidin.

GFP refers to staining for eGFP in BAC transgenic mice of the genotype ΔNeurog1-eGFP.

Antibody specificity

As a general rule, the antibodies that we used here are either standard ones for the field (i.e., PGP9.5), or ones for which the staining patterns generated by us or available in the literature are the same as described or directly observed with another, independently-generated antibody targeting the same protein (i.e., for Sox2, two antibodies were tested and used; for Pax6, the staining pattern generated by the antibody used here is equivalent to the previous publication on the expression of Pax6 in the olfactory epithelium; Davis and Reed, 1996). For the antibodies listed in Table 1, additional studies reported by the manufacturer that demonstrate specificity are summarized below, with references to the published literature where appropriate.

The anti-CD-54 antibody shows inhibition in the HSB2 adhesion assay by blocking adhesion of target cells to ICAM-1 (R&D Systems, Product Data sheet AF583) and a single band at 90kDa molecular weight is detected on Western Blot of HUVEC cell lysate stimulated with TNFalpha (Sawa et al, 2007).

The anti-CK14 antibody VP-C410 labels basal cells in skin, selectively, with a cytoplasmic distribution (Vector Laboratories Datasheet VP-C410). The staining pattern with VP-C410 is completely equivalent to that observed with another anti-CK14 monoclonal, RGE-53, which labels a single spot in 2-D IEF-SDS-PAGE Western blot with a molecular weight and isoelectric point consistent with CK14 (Holbrook et al., 1995). The choice of VP-C410 was predicated on the retention of antigenicity despite formaldehyde fixation.

The goat and rabbit anti-FITC antibodies demonstrate quenching of FITC fluorescence in soluble assay (Molecular Probes, The Handbook, http://www.invitrogen.com/site/us/en/home/References/Molecular-Probes-The-Handbook/Antibodies-Avidins-Lectins-and-Related-Products/Anti-Dye-and-Anti-Hapten-Antibodies.html). The mouse anti-FITC was shown to produce a dose-dependant quenching of FITC in a soluble assay as well as specific reactivity to FITC and DTAF, but not TRITC (Personal communication with Mary Kay Phillips, Manager, Product Development, Jackson Immunoresearch).

The anti-Ki67 antibody reacts with a 345/395 kDa protein doublet on Western blot; in addition, binding to cells is blocked by the canonical anti-Ki67 clone, MIB 1 (BD Biosciences Datasheet #556003).

The anti-Mash1 detects a single 34 kDa band on Western Blots of rat embryonic brain lysate (BD Biosciences Datasheet #556604).

The anti-NeuroD1 antibody detects a single band of 50 kDa on Western blots of both MM-142 nuclear extracts and Y79 whole cell lysate (SantaCruz datasheet #sc-1086), and the post-MeBr lesion timing, number and pattern of labeled cells corresponds well with ISH studies (Manglapus et al., 2004).

The anti-Neurog1 antibody detects a single band of 27 kDa on Western Blots of mouse brain tissue extract (Santa Cruz datasheet #sc-19231), and the post-MeBr lesion timing, number and pattern of labeled cells fits with ISH studies (Manglapus et al., 2004).

The anti-p27Kip1 antibody detects a single band of 27 kDa on Western blots of HeLa cell lysate (BD biosciences datasheet #610241).

The anti-Pax6 antibody detects a single band of 50 kDa on Western blots of fetal mouse brain (Chemicon Datasheet #AB5409).

The anti-PGP9.5 antibody detects a band of 27 kDa on Western blots of mouse brain and rat pineal gland lysate (Tsai et al., 20008). This antibody cross reacts with all mammalian species so far tested (Ultraclone limited datasheet RA95101, Hasegawa and Wang, 2008).

The goat anti-Sox2 antibody detects a single band of 34 kDa in Western blot of mouse and human embryonic stem cell lysates (clone Y-17: datasheet # sc-17320) and antibody staining on embryonic tissue from Mash1 knockout olfactory epithelium replicates the published Sox2 mRNA pattern by ISH (Kawauchi et al, 2004).

The rabbit anti-Sox2 antibody recognizes a single band of 34 kDa in Western blot of mouse and human embryonic stem cells or NT2/D1 cells in whole cell lysates or nuclear preparations that is not seen in the cytosol (Millipore data sheet).

Monoclonal antibody 213-4.4 (MAb 213) was raised against formaldehyde-fixed full-length TGF-alpha (Oncogene Science, Uniondale, NY), We have previously shown that MAb 213 labels a subset of olfactory neurons that project to the necklace glomeruli of the main olfactory bulb under the conditions of fixation used here (Ring et al., 1997). Comparison with other antibodies against TGF-alpha indicates that the neuronal labeling is not against the growth factor, but some fixation-induced, but useful, alternative antigen, which has not been identified (Ring et al.,1997).

Cell Counts

Cell counts were performed on sections of rat OE stained with Pax6, CK14 and Ki67, or ones stained with Pax6, CK14 and p27Kip1, in order to determine what proportion of the Pax6 population was proliferating (Ki67 (+)) vs. quiescent (p27Kip1 (+)). The septum on one section was sampled per staining condition. All of the markers under consideration are nuclear. Thus, a labeled profile was included in the count when the nucleus was recognizable as such. Counts of nuclear profiles are corrected for cell size as follows. Nuclear diameters are measured under direct observation using a 60x oil objective. In the case of p27Kip1, the nuclei of all the double-labeled cells (n = 5) were measured and compared to 25 nuclei of the Pax6 (+)-only cells (n = 181). In the case of Ki-67, the nuclei of all of the Pax6-only cells (n = 12) were measured and compared to 25 nuclei of the Pax6 (+)/Ki67 (+) cells (n = 93). The values for nuclear diameter were 4.83 ± 0.09, 4.91 ± 0.11, 4.92 ± 0.12, and 4.78 ± 0.10, respectively, for mean ± standard error of the mean, none of which are significantly different from any other. For purposes of calculating the proportion of profiles for each cell type, the profile counts were adjusted taking into account Abercrombie’s correction formula (Abercrombie, 1946) and percentages of total were then calculated.

Similarly, anti-Neurog1 (+) cells were assayed for detectable expression of GFP in mice that bear the BAC transgene ΔNeurog1-eGFP (see above for the description of the transgenic line). Counts were carried out across the OE of a section spaced midway along the anteroposterior extent of the epithelium, and cells were classified as anti-Neurog1 (+)/anti-GFP (+) or anti-Neurog1 (+)/anti-GFP (−). Nuclear diameters were measured on images taken with a 60x oil objective. The values for nuclear diameter were 3.94 ± 0.36 and 4.21 ± 0.60, respectively, for mean ± standard error of the mean; the values are not significantly different from each other. The counts of the cell profiles were adjusted as described above, using the nuclear diameters and Abercrombie’s correction.

Photography

Sections were imaged with a Spot RT color digital camera attached to Nikon 800 E microscope. Image preparation, assembly and analysis were performed in Photoshop CS2 and CS3. In all cases, only balance, contrast, brightness, and evenness of the illumination were altered.

RESULTS

Expression pattern of Sox2 and Pax6 in normal rat OE

Immunohistochemical labeling of the rat OE with either goat (Fig. 1) or rabbit (data not shown) anti-Sox2 antibody stains several different cell types at the apex and at the base of the epithelium with variable intensity.

Figure 1.

Pax6 and Sox2 are expressed by a subgroup of GBCs. (A, C) Normal adult rat OE was stained with either anti-Pax6 antibody (in A) or anti-Sox2 antibody (in C) (both were visualized with DAB), followed by immunostaining with antibody against the horizontal basal cell (HBC) cell marker CD54 (visualized with FITC-labeled strepavidin) with corresponding insets at higher magnification in B, D, respectively. The presence of Pax6 and Sox2 in a subset of globose basal cells (GBC) is confirmed by the expression of Pax6 and the absence of CD54 in these cells, as indicated by the thick arrows. Some Pax6 (+) cells make contact with basal lamina but are not CD54 (+), as indicated by the thin arrow; basal cells such as these have also been observed with the electron microscope (Holbrook et al., 1995). BD – Bowman’s duct, BG – Bowman’s gland, both of which stain with anti-Pax6. Arrowheads mark the basal lamina. Scale bar in C is 25 µm and also applies to A. Scale bar in D is 10 µm and also applies to B.

The position and the shape of the stained cells allow one to assign the dense staining at the apex to the nuclei of sustentacular cells. Near the base of the epithelium, cells with labeled nuclei are found in close apposition to the basal lamina, while others are at a slight remove from it. Double-staining of the normal rat OE with any one of a set of specific markers for horizontal basal cells (HBCs) including anti-CD54 (Fig. 1), the lectin BS-1 (data not shown), or cytokeratins (CK) 5 (data not shown) and 14 (Fig. 2) demonstrate that some among the labeled basal cells express known HBC markers, and thus are HBCs, while others are found slightly more superficial to the layer of HBCs, and thus are GBCs. Based on the number and distribution of CK (+) cells and the incidence of double labeling with anti-Sox2, it appears that all HBCs express the transcription factor. That antibody labeling of Sus cells, HBCs, and GBCs represents authentic Sox2 is indicated by the identity of staining pattern with both goat and rabbit antibodies, confirmation of antibody specificity in Western blots of normal OE, the demonstration of Sox2 mRNA in the epithelium by RT-PCR, and the expression of eGFP from the Sox2 locus in transgenic mice (data not shown). Sox2 does not label olfactory neurons; in the normal adult rat OE PGP9.5 (a marker for all neurons) and Sox2 labeled completely non-overlapping groups of cells (Suppl. Fig. 1).

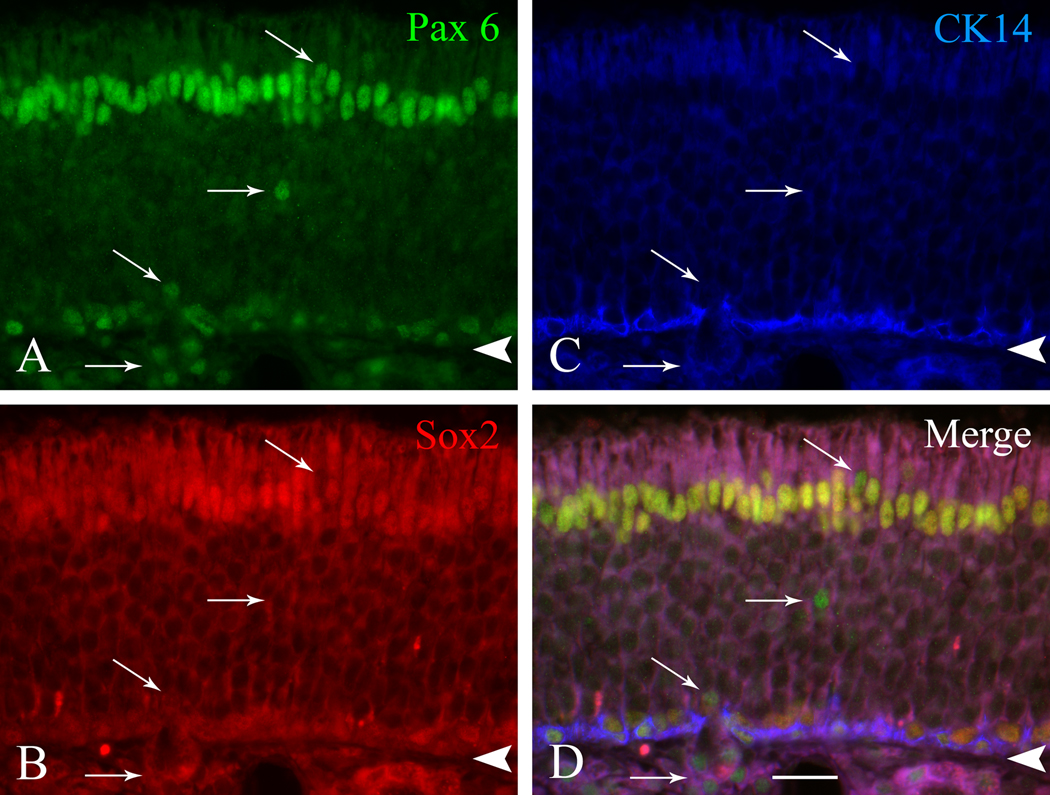

Figure 2.

Pax6 and Sox2 are co-expressed by the same subgroup of GBCs in rat OE. Section of normal rat OE stained with: A) anti-Pax6 (visualized with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody), B) anti-Sox2 (visualized with Texas red®-conjugated secondary antibody), C) anti-CK14 (visualized with AMCA-conjugated secondary antibody. D) Merged image. Staining with Pax6 and Sox2 is coincident and double-labeled cells appear yellow-orange in the merged image; these include Sus cells at the apex of the epithelium, HBCs marked with CK14 at the base, and GBCs situated immediately above the CK14 (+) cells. Arrows in A and D mark cells that are labeled only with Pax6 and are cells of Bowman’s gland and ducts. Arrowheads mark the basal lamina. Scale bar in D is 10 µm and also applies to the other panels.

Given the overlap between the pattern of Sox2-labeling demonstrated here and the published description of the staining observed with an anti-Pax6 antiserum in mouse OE (Davis and Reed, 1996), we also re-examined the expression of Pax6 in the normal OE using two antibodies that are different from the one used in the previous report (Fig. 1). The staining that we obtained here with our anti-Pax6 antibodies matches the previous description precisely, and the same complicated pattern of labeling is observed. The current data demonstrate that anti-Pax6 labels the nuclei of sustentacular cells densely (Fig. 1). In addition, staining of basal cells is seen, resembling that seen with anti-Sox2. Besides the cells that co-express Sox2, the nuclei of Bowman's gland and duct cells are also labeled with anti-Pax6; the gland cells are found in the lamina propria interspersed between fascicles of the olfactory nerve and blood vessels, while the Pax6 (+) duct cells have an elongated nucleus and form a cell stack that extends apicalward through the basal lamina to the surface of the OE. In addition to these types, some cells found in the middle of the OE are more strongly Pax6 (+) than any other cells in the epithelium; these are particularly prevalent in the ventral part of the OE and in the posterolateral cul de sacs of the OE. With regard to the latter category, we will demonstrate below that the Pax6 (+) cells are neurons that project to necklace glomeruli of the olfactory bulb. RT-PCR results (data not shown) and the equivalence of the staining pattern with multiple Pax6 antibodies in multiple species indicate that the labeling does indeed represent expressed Pax6.

The apparent similarity of Pax6 and Sox2 expression by basal cells is emphasized by double labeling with the HBC marker CD54 (Fig. 1). As for Sox2, some of the Pax6 (+) basal cells are co-labeled with anti-CD54 and are clearly HBCs (and conversely all HBCs are Pax6 (+) as well as Sox2 (+)), but others Pax6 (+) cells are situated superficial to the CD54 (+) cells and are GBCs (Fig. 1).

The apparent co-expression of Sox2 and Pax6 by Sus cells, HBCs, and GBCs was confirmed by double labeling with both antibodies using several approaches. Neither the Pax6 nor the Sox2 antibodies generate particularly robust staining, which is to be expected given the usual challenge of assaying for expression of transcription factors. The most direct demonstration entails triple immunofluorescent labeling for Pax6 (green channel), Sox2 (red), and CK14 (blue) (Fig. 2). Double-labeled Sus cells, HBCs, and GBCs are evident in the merged RGB image. While the staining with anti-Sox2 is weak, and only slightly above background when examined in the red channel alone, examination with a dual FITC/Texas Red filter and merging of the individual channels allows one to distinguish double-labeled cells as ones shifted toward yellow by comparison with the green, Pax6-only duct/gland cells and necklace neurons.

As an alternative approach, DAB was used to mark Sox2 (+) cells or Pax6 (+) cells on separate sections followed, in each of the two cases, by immunofluorescent labeling for the other marker. Sequential DAB-immunofluorescent staining is a subtractive method; it takes advantage of the quenching of immunoflourescence where chromogen is deposited such that the absence of the fluorescent label from where it is normally seen indicates that a cell also expresses the second marker. Thus, as expected, DAB labeling to visualize bound anti-Sox2 eliminates the subsequent immunoflourescent labeling of Sus cells, HBCs, and GBCs by anti-Pax6, and vice-versa (Suppl. Fig. 2). That the quenching of signal by the DAB part of the procedure is limited to cells that co-express both transcription factors is shown by the immunoflourescent labeling of duct-gland cells with anti-Pax6 despite the deposition of DAB on top of Sox2 when the latter marker was used first (Suppl. Fig. 2).

It is worth noting that we also performed triple-labeling on the mouse OE. Similar results were obtained (Fig. 3). In the case of the mouse OE, two separate anti-Pax6 antibodies stained equivalently: the rabbit anti-Pax6 described above and the mouse monoclonal anti-Pax6 obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (not shown).

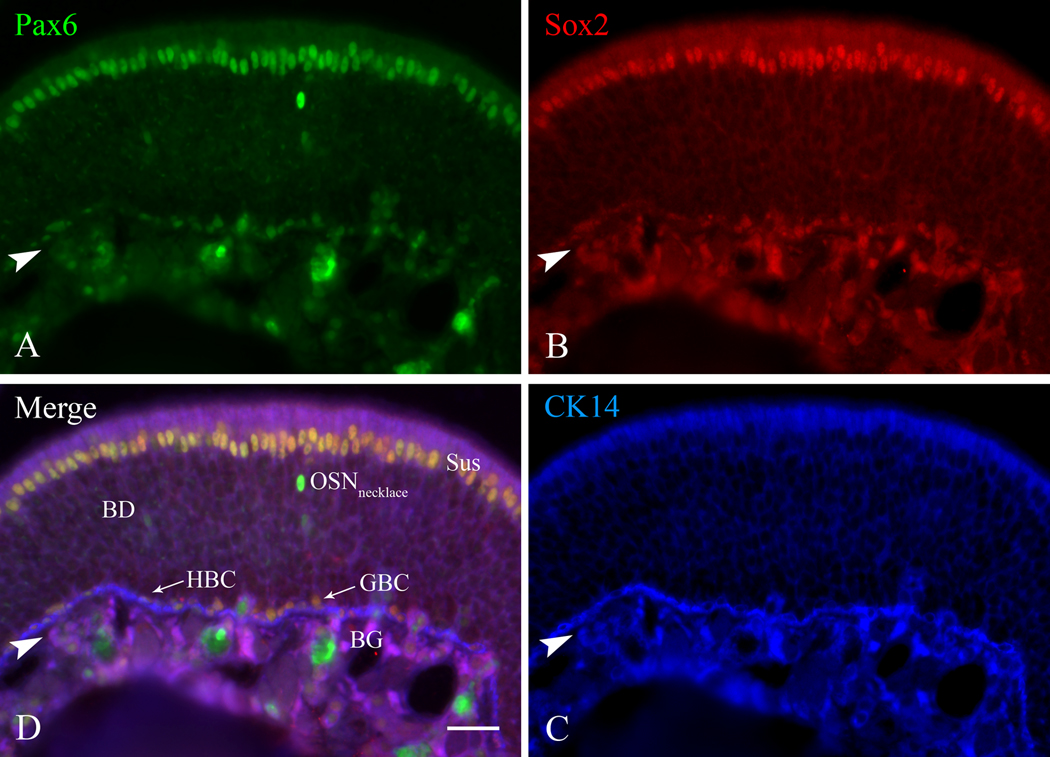

Figure 3.

Pax6 and Sox2 are co-expressed by the same subgroup of GBCs in the mouse OE as well. Section of normal mouse OE triple-labeled for Pax6, Sox2, and CK14. A) Anti-Pax6 staining. B) Anti-Sox2 staining. C) Anti-CK14 staining for HBCs. D) Merged image of all three labels. As in the rat OE, Pax6 labels Sus cells, Bowman’s gland (BG) and duct (BD) cells, the monolayer of HBCs apposed to the basal lamina and a population of necklace neurons (OSNnecklace) in the neuronal layers of the OE. The neuronal identity of the intensely Pax6 (+) neuronal zone cells was confirmed by staining sections of a transgenic mouse OE in which the LacZ gene is knocked into the Pax6 locus with anti-β-galactosidase and monoclonal antibody MAb213, a known necklace neuron marker (data not shown). Arrowheads mark the basal lamina. Scale bar in D is 25 µm and also applies to the other panels.

The results show that Pax6 and Sox2 are co-expressed in some GBCs in the OE of mouse and rat. To take advantage of its more robust staining, anti-Pax6 labeling was used as a proxy for the Pax6 (+)/Sox2 (+) GBCs in most of the comparisons with other markers. It is important to note that the Pax6 (+) GBCs can be distinguished from Pax6 (+) duct cells on the basis of cell shape and arrangement. To take advantage of antibody compatibility, the analysis focused on the rat OE.

Many but not all Pax6/Sox2 (+) GBCs are actively in the mitotic cycle

GBCs are a heterogeneous cell population, in both molecular and functional terms, varying with regard to the rate of proliferation, the expression of transcription factors that correlate with cell commitment, etc. In order to characterize the subset of Pax6/Sox2 (+) GBCs, we first examined the cell cycle behavior of this subset of GBCs using Ki67 as a marker for proliferating cells (Fig. 4). Ki67 is a DNA-binding protein of unknown function and is expressed in all phases of the cell cycle except G0. Anti-Ki67 antibody typically produced punctate nuclear staining in the basal layer of the OE. Direct double immunofluorescent comparison of Ki67 with acute BrdU labeling suggests that the vast majority of the Ki67 (+) basal cells are GBCs (X. Chen, W. Jang, M.R. Harris, J.E. Schwob, unpublished results). For example, Ki67 (+) GBCs are bunched in the OE, coincident with the clusters of GBCs labeled by acute BrdU incorporation. While Ki67 antibody also does stain occasional Sus cell nuclei at the apex of the OE, some duct cells, and a few HBCs, their individual and cumulative frequencies are much lower than labeled GBCs. Triple labeling with Ki67, Pax6, and CD54 demonstrates that majority of the Pax6 (+) GBCs expressed Ki67 as well (arrows with asterisks, Fig. 4), suggesting that most of the Pax6 (+) GBCs are actively proliferating. However, among the Pax6 (+) GBCs, a modest percentage of cells (12 out of 105 profiles counted, after correction for cell size as described in the methods, this number corresponds to 11%) are not labeled by anti-Ki67 (as indicated by arrows in Fig. 4), suggesting that they are not cycling.

Figure 4.

The majority of the Pax6 (+) GBCs are actively cycling. Normal rat OE stained with: A, B) anti-Pax6; C, D) anti-Ki-67, a marker of cells in all phases of the cell cycle except G0; G, H) anti-CD54, a marker of HBCs. E, F) the merged image of Pax6 and Ki67 staining. I, J) the merged image of Pax6, Ki67, and CD54. Boxed areas are shown at higher power in B, D, F, H, J. Arrows with asterisks designate Pax6 (+)/Ki-67 (+) GBCs, which are situated above the CD54 (+) HBCs. Arrows (without asterisks) mark GBCs that are only Pax6 (+) and lack detectable Ki67 labeling. Scale bar in I is 25 µm and also applies to A, C, E, G. Arrowheads mark the basal lamina. Scale bar in J is 10 µm and also applies to B, D, F, H. A magenta-green version of this figure is available online as Supplementary Figure 4.

To assay whether some of the Pax6/Sox2 (+) GBCs are likely to be quiescent (as suggested by the absence of Ki67 labeling), we compared the expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 and Pax6 in OE (Fig. 5). Immature neurons, which are situated just above the basal layer, are heavily labeled for p27Kip1, while expression of the CDKI then decreases in more superficially placed, presumably more mature OSNs. The vast majority of the Pax6 (+) GBCs do not express p27Kip1, consistent with the Ki-67 labeling and a further indication that they are actively cycling. However, close examination demonstrated a low percentage of Pax6 (+) GBCs that also express p27Kip1 (5 out of 186 profiles counted, after correction for cell size this number corresponds to 3%), as indicated by the presence of Pax6, p27Kip1 and absence of HBC marker CD54 (Fig. 5). The latter observation provides a further indication of cell cycle heterogeneity among the Pax6/Sox2-expressing GBCs.

Figure 5.

Some Pax6 (+) GBCs express the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 in the normal rat OE and are likely to be mitotically quiescent. Triple-labeled section of normal rat OE for Pax6, p27Kip1 and CD54. A) Anti-Pax6 staining; the arrow and arrow with asterisk designate Pax6 (+) GBCs and their surround that are shown at higher magnification in A’, A”, as indicated. B, B’, B”) Anti-p27Kip1 staining of the same section. The Pax6 (+) GBC designated by the arrow is not labeled for p27Kip1, while the GBC designated by the arrow with asterisk does express detectable p27Kip1C, C’, C”) Merged Pax6 and p27Kip1 staining, documenting that p27Kip1 and Pax6 are co-expressed in some GBCs (including the example marked by the arrow with asterisk); but most of the Pax6 (+) cells lack detectable p27Kip1 expression (including the example indicated by the solo arrow). D, D’, D”) Anti-CD54 staining to mark HBCs. E, E’, E”) The merged image of Pax6, p27Kip1 and CD54 staining to confirm that the p27Kip1 (+)/Pax6 (+) basal cells are CD54 (−) and indeed GBCs (arrow with asterisk). Arrowheads mark the basal lamina. Scale bar in E is 25 µm and also applies to A–D. Scale bar in E” is 10 µm and also applies to all other images. A magenta-green version of this figure is available online as Supplementary Figure 5.

Comparison of anti-Pax6, anti-Sox2, anti-Mash1, and anti-Neurog1 labeling

To gain further insight into the nature of the Pax6/Sox2 (+) GBCs in OE, we compared Pax6 labeling with the expression of key pro-neural bHLH transcription factors Mash1 and Neurog1 (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). As described previously, neurogenesis in the OE occurs through sequential activation of serial bHLH family factors: Mash1 followed by Neurog1 and NeuroD1 (which may lag Neurog1 slightly; Cau et al., 1997, 2002). Mash1 and Neurog1 apparently define distinct groups of GBCs that are committed to making neurons vs. those that are actively generating post-mitotic neurons, respectively (at least some NeuroD1 (+) and Neurog1 (+) GBCs are actively proliferating and incorporate BrdU, A.I. Packard, R.C. Krolewski and J.E. Schwob, unpublished results).

Figure 6.

Many Pax6 (+) GBCs are Mash1 (+). Triple-labeled section of normal rat OE for Pax6, Mash1, and CD54. Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification on the right. A, A’) Anti-Pax6 staining; Pax6 (+) GBCs are indicated by arrows (with or without asterisks). B, B’) Anti-Mash1 staining; Mash1 (+) GBCs are indicated by arrows with asterisks. C, C’) Merged image of Pax6 and Mash1 staining. D, D’) Anti- CD54 staining to mark HBCs. E, E’) Merged image of Pax6, Mash1, and CD54 staining to demonstrate that the some Pax6 (+)/Mash1 (−) basal cells are CD54 (−) and indeed GBCs. Arrowheads mark the basal lamina. Scale bar in E is 25 µm and also applies to A–D. Scale bar in E’ is 10 µm and also applies to A’, D’. A magenta-green version of this figure is available online as Supplementary Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Many Neurog1 (+) GBCs are not Pax6 (+). Section of normal rat OE double-stained with anti-Neurog1 and anti-Pax6. A, D, G, J) Anti-Neurog1 staining, a marker for GBCs that function as immediate neuronal precursors. B, E, H, K) Anti-Pax6 staining. The Neurog1 (+) GBCs indicated by the arrows are not labeled with Pax6. C, F, I, L) Merged image of Pax6 and Neurog1 staining. Neurog1 (+)-only cells in A–F are indicated by arrows and are situated superficial to the Pax6 (+) GBCs. Neurog1 (+)/Pax6 (+) cells in G–L are indicated by arrows with asterisks. Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification in the panels to the immediate right. Arrowheads mark the basal lamina. Scale bar in C is 25 µm and also applies to A and B. Scale bar in L is 10 µm and also applies to D–K. A magenta-green version of this figure is available online as Supplementary Figure 7.

In keeping with prior reports (Gordon et al., 1995; Manglapus et al., 2004), anti-Mash1 stained relatively low number of basal cells in clusters or singletons throughout the normal OE. As Mash1 and the HBC marker CD54 labeled mutually exclusive cells, the Mash1 (+) cells are all GBCs (Fig. 6). Double labeling for Mash1 and Pax6 suggested that all or the vast majority of Mash1 (+) cells also expressed Pax6/Sox2. Conversely, despite the abundance of double-labeled cells, some Pax6 (+) GBCs (identified as such by the usual criteria of sitting superficial to the layer of HBCs and being round rather than the spindle-shape that is typical of duct cells) do not express Mash1 (thin arrows in Fig. 6).

The relationship between Pax6 expression and Neurog1 is more complicated (Fig. 7). Here, too, Neurog1 stains scattered clusters and singletons, though overall they are relatively few by comparison with the total number or Sox2/Pax6 cells and the number of basal cells that are proliferating and express Ki67. Anti-Pax6 does co-label some Neurog1 (+) GBCs, at least lightly, but many of the anti-Neurog1 (+) cells lack detectable Pax6. We wanted to take a more comprehensive look at the Neurog1 (+) population so we took advantage of a BAC transgenic mouse line in which GFP is driven from the Neurog1 locus. In this strain, GFP label is found in most of the Neurog1 (+) cells, but extends into the population of immature neurons due to perdurance of the label beyond the stage of Neurog1 expression (Suppl. Fig. 3). The eGFP marker does not overlap with Mash1 expression, as expected from previous analyses in mouse OE (Cau et al., 1997), but does coincide with GBCs that are BrdU (+) or Ki-67 (+) and thus actively dividing (R.C. Krolewski and J.E. Schwob, unpublished data). Counts of Neurog1 (+) profiles, corrected by the Abercrombie formula, indicate that 75% of them are co-labeled by GFP (Suppl. Fig. 3). The remainder of the Neurog1 (+) cells do not contain detectable GFP or show only the faintest blush of the label. The lack of GFP label in some Neurog1-expressing cells presumably reflects a lag between the onset of expression of the Neurog1 BAC locus, and the accumulation of sufficient GFP to become evident. Nonetheless, comparing Sox2 expression with the Neurog1-driven GFP is instructive. We find that the GFP-labeled cells and the Sox2 (+) GBCs are mutually exclusive (Fig. 8), which suggests that Sox2 and Pax6 are limited to the Neurog1-expressing GBCs that have more recently begun to express the Neurog1 locus. In sum, the analysis of the GBC population suggests that multiple subsets of GBCs express Pax6 and Sox2. Comparing the relative numbers of the various subpopulations of GBCs is instructive to that end. Mash1 and Neurog1 (+) cells are fewer in aggregate than the size of the Sox2 (+)/Pax6 (+) GBC population in total or of the population of Ki67 (+) basal cells overall. That discrepancy in numbers suggests that a substantial fraction of the Sox2/Pax6-expressing GBCs in the normal OE are likely to be upstream of the Mash1 (+) and Neurog1 (+) cells and may be multipotent progenitors (MPPs). The assignment of Sox2 and Pax6 to multipotent GBCs is consistent with published reports showing that Sox2 is expressed by stem cells and neuronal progenitor cells in the subventricular zone of the adult CNS (Ellis et al., 2004). Our interpretation is more firmly established by the analysis of the lesioned-recovering OE (see below).

Figure 8.

Neurog1 (+) GBCs in the OE are mainly Pax6 (−)/Sox2(−) as shown by analysis of the ΔNeurog1-eGFP BAC transgenic mouse line (generated by the Gensat project at the Rockefeller University; Gong et al., 2003). A, B) Sox2 labeling of the OE of a mouse bulbctomized 3 weeks before harvest. E, F) GFP labeling enhanced by anti-GFP staining. C, D) Merged image. Sox 2 (+) cells are found deep to the eGFP-labeled cells (arrows); the Neurog1 (+) cell marked by the arrow with asterisk is also GFP (−), but is closely apposed to GFP (+) cells. In this mouse line detectable eGFP marks the majority of Neurog1 (+) GBCs, as well as carrying over into immature neurons (see Supplementary Figure 3). Hence, most Neurog1 (+) cells in the neurogenic mouse OE do not contain detectable Sox2. Arrowheads mark the basal lamina. The scale bar in E is 25 µm and also applies to A, C. The scale bar in F is 10 µm and also applies to B, D. A magenta-green version of this figure is available online as Supplementary Figure 8.

Quiescent GBCs are neither Mash1 (+) nor NeuroD1 (+)

The forgoing results, in combination with the finding that some Pax6 (+) GBCs express the CDK inhibitor p27Kip1, raise the question of whether the Pax6 (+)/p27Kip1 (+) GBCs are either Mash1 (+) or NeuroD1 (+) (which is used in this case instead of Neurog1 to achieve compatibility with immunohistochemical detection). Indeed, NeuroD1 is thought to lag Neurog1 slightly (Cau et al., 1997, 2002), which would bring it closer to the time when p27Kip1 is expressed by the postmitotic differentiating olfactory neurons. The combination of anti-p27Kip1 and anti-Mash1 immunostaining demonstrates that the two labels are mutually exclusive (Fig. 9). Likewise, p27Kip1 does not co-localize with anti-NeuroD1, although it stains the differentiating neurons immediately apical to them heavily (Fig. 10). We examined over 100 Mash1 (+) and an equivalent number of NeuroD1 (+) cells without seeing any that were double labeled with p27Kip1. Other p27Kip1 (+) putative GBCs were seen while scanning for that number, and the frequency of Pax6 (+)/p27Kip1 (+) GBCs described above suggests that a sample of that size ought to contain them, if they exist. As a consequence, the p27Kip1 (+) /Pax6 (+) GBCs are likely to be upstream of the onset of Mash1 and NeuroD1 expression and are likely fall within the category that are multipotent.

Figure 9.

Mash1 (+) GBCs are not p27Kip1 (+) and, thus, apparently not quiescent. Section of normal rat OE double-stained for Mash1 and p27Kip1A, A’) Anti-Mash1 staining. The Mash1 (+) GBCs are indicated by arrows, B, B’) Anti- p27Kip1 staining; the Mash1 (+) cells (arrows) are positioned deep to the layer of p27Kip1 (+) immature neurons. C, C’) Merged image of Mash1 and p27Kip1 labeling. Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification in the panels on the right. Arrowheads mark the basal lamina. Scale bar in E is 25 µm and also applies to A and E. Scale bar in F is 10 µm and also applies to B and D. A magenta-green version of this figure is available online as Supplementary Figure 9.

Figure 10.

NeuroD1 (+) GBCs are not p27Kip1 (+) and, thus, apparently not quiescent. Section of normal rat OE double-stained for NeuroD1 and p27Kip1. In this large cluster of GBCs all of the NeuroD1 (+) cells are deep to the band of p27 labeled cells. Arrowheads mark the basal lamina. The scale bar in C is 20 µm and applies to all panels. A magenta-green version of this figure is available online as Supplementary Figure 10.

Expression pattern of Sox2 and Pax6 post-MeBr lesion and post-bulbectomy

MeBr exposure destroys the Sus cells and neurons of the OE and depletes the other cell populations to a variable extent (Schwob et al., 1995). The lesion activates multipotent progenitors amongst the population of GBCs and HBCs that participate in the reconstitution of the OE (Huard et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2004; Leung and Reed, 2007). Moreover, the uniform severity of the lesion synchronizes the sequential expression of bHLH factors as a function of time after MeBr (Manglapus et al., 2004). Therefore, the regeneration process provides an unparalleled opportunity to associate marker expression with particular stages in the progression from multipotent progenitor to the production of differentiated cells. We examined the expression dynamics of Pax6 and Sox2 during the regeneration of the OE after unilateral MeBr exposure (Fig. 11). Nuclear labeling with anti-Pax6 and anti-Sox2 is very dense in all or the vast majority of the spared cells at 1 and 2 days after lesion (Fig. 11, Fig. 12). At this phase in the regeneration process, lineage tracing by retroviral vector transduction demonstrates that many, perhaps most, of the basal cells are multipotent at this time point and able to give rise to a variety of cells types (Huard et al., 1998); importantly, the most superficial basal cells in the rat OE at 1 day after MeBr, and thus most susceptible to infection, are GBCs (Fig. 12; Huard et al., 1998).

Figure 11.

Immunolabeling for Pax6, Sox2, and Mash1 during the reconstitution of rat OE elicited by MeBr lesion. A – G) Anti-Pax6 staining in unlesioned OE (Un) and at the various designated time points (1d – 14d) after MeBr lesion. A’ – G’) Anti-Sox2 staining from the same tissue at the same time points after MeBr lesion. A” – G”) Anti-Mash1 staining from the same tissue at the same time points after MeBr lesion. All or the overwhelming majority of the epithelial cells are labeled with Pax6 and Sox2 at 1 and 2 days after MeBr lesion. Cells that stain with anti-Mash1 do not reappear until 2 days post lesion. The first Pax6 (−)/Sox2 (−) cells become evident at 3 days post lesion. A more prominent layer of Pax6 (−)/Sox2 (−) cells emerges and then expands from 5–14 days after lesion as neurogenesis reconstitutes the population of sensory neurons. Arrowheads mark the basal lamina. Scale bar in G” is 50 µm and applies to all other panels.

Figure 12.

Higher magnification examination shows that all epithelial cells are Pax6 (+) and Sox2 (+) at early stages in reconstitution of the rat OE following MeBr lesion. A, B) Section from animal euthanized 1 d after lesion, double-labeled with anti-Pax6 (A) visualized with DAB and anti-CD54 (B) visualized with fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody. Many of the cells are located superficial to the layer of CD54 (+) HBCs. C, D) Anti-Sox2 staining 1 day and 2 days after MeBr lesion visualized with DAB; all of the epithelial cells label for Sox2 at this stage. Asterisks in C designate debris that has not yet cleared from the nasal cavity after lesion. E, F) Anti-Mash1 labeling from the same tissue, showing an absence of stained cells at 1 day after lesion (E) and their reappearance at 2 days after lesion (F). Arrowheads mark the basal lamina. Scale bar in E is 10 µm and applies to all other panels.

Sox2 (+) and Pax6 (+) cells still dominate the recovering OE at 3 days after lesion (Fig. 11, Fig. 13). However, in the 3-day post lesion OE, some of the cells lack detectable Sox2 and Pax6 (Fig. 11, Fig. 13). Neurog1 (+) and NeuroD1 (+) GBCs, detected by in situ hybridization (ISH), re-appear – although still sparse – at that same 3-day post-lesion time point. Indeed, the same material was used for both analyses; i.e., the illustrations for Pax6 and Sox2 immunostaining after lesion are drawn from the same rats as used previously for the ISH analysis of bHLH TF expression (Manglapus et al., 2004). The results at this time point during recovery also fit well with the absence of detectable Pax6 and Sox2 from many Neurog1 (+) GBCs in the neurogenic OE (Fig. 7, Fig. 8).

Figure 13.

Higher magnification examination confirms that Pax6 (−)/Sox2 (−) cells begin to re-emerge at 3 days after MeBr lesion. Triple-stained section of rat OE harvested 3 days after MeBr lesion. A) Anti-Pax6 staining – a few Pax6 (−) cells are evident at this point in the reconstitution of the OE (arrows). B) Anti-Sox2 staining – a larger number of cells are now Sox2 (−). Of these some are Pax6 (+) only (arrow with asterisk) and are presumably Bowman’s duct cells at the surface of the recovering OE. The remainder, including both GBCs and HBCs, co-express both factors and are Pax6 (+)/Sox2 (+). C) Anti-CK14 staining to mark HBCs. The Pax6 (−)/Sox2 (−) basal cells (arrows) are also CK14 (−), and hence are GBCs. Arrowheads mark the basal lamina. Scale bar in D is 10 µm and also applies to the other panels.

A band of Sox2 (−)/Pax6 (−) cells emerges, occupies the middle layer of the OE (along the basal to apical axis), and expands from 5 days post-lesion onward, which corresponds in large part to the population of newly-born and differentiating neurons (Fig. 11). The normal expression patterns of Sox2 and Pax6 in the OE are largely restored by 14 days post-MeBr (cf. Fig 1, Fig 11).

To assay further the relationship between expression of Pax6 and Sox2 and progenitors moving toward a neuronal fate, we analyzed the expression of Mash1 protein during epithelial regeneration (Fig. 11, Fig. 12), as a complement to our prior analysis by ISH. As expected from the previous results (Manglapus et al., 2004), Mash1 staining was largely absent from OE at 1-day post-lesion, with the exception of very rare labeled basal cells, which further buttresses the idea that Sox2 and Pax6 can be expressed in GBCs that are upstream of Mash1. Mash1 expression in the OE is strongly up-regulated at 2 days post-lesion and is maintained at a higher than normal level at 3 days. That all epithelial cells are Sox2 (+) and Pax6 (+) at 2 days post MeBr lesion, when Mash1 (+) GBCs are prevalent, suggests that Mash1 and Sox2/Pax6 are co-expressed by some GBCs in the lesioned OE as in the normal. The coincidence of Mash1 and Pax6 immunolabeling at 2 days after lesion strongly supports that interpretation (Fig. 12). Mash1 (+) GBCs begin to decrease in number and are largely confined to the basal 2–3 layers of cells in OE from 5 days post-lesion onward, such that the normal expression pattern of Mash1 is largely restored at 14 days post-lesion (Fig. 11). The present observations on Mash1 protein expression are fully consistent with our prior results using in situ hybridization for Mash1 after MeBr lesion (Manglapus et al., 2004).

In contrast to the widespread damage to the epithelium that results from MeBr exposure, olfactory bulbectomy kills those olfactory neurons whose axons are severed by the procedure, abbreviates the lifespan of those who are born and/or reach the ablation cavity after the lesion, and accelerates the proliferation of GBCs (Schwob et al., 1992); ablation of the bulb does not cause the degeneration of any other cell group. We determined the expression profile of Pax6 and Sox2 at various survival times after unilateral bulbectomy (Fig. 12 and, in mice, by comparison with Neurog1-driven expression of eGFP, Suppl. Fig. 3). The expression patterns of both Pax6 and Sox2 remain similar to the normal OE, with regard to the types of cells labeled. However, the population of Sox2 (+) and Pax6 (+) GBCs grows larger and more prominent within a few days after lesion as the rate of GBC proliferation increases, peaks at 7–10 days after lesion, and remains greater than normal at 14 days after ablation (Carr and Farbman, 1992, 1993).

Pax6 expression in a group of sensory neurons

As noted above (Fig. 1), anti-Pax6 heavily stains the nuclei of a small number of cells in the middle layers of ventral OE and in the epithelium lining the posterior cul-de-sacs of the nasal cavity. Previously published work on Pax6 expression also took note of densely labeled cells midway along the basal-to-apical axis, but suggested they were basal cells differentiating into sustentacular cells and migrating from deep to superficial in the OE (Davis and Reed, 1996). That these intensely positive Pax6-expressing cells are limited to specific regions of the OE is not particularly consistent with that interpretation. Rather, the positioning of such intensely Pax6 (+) cells across the epithelium is highly reminiscent of the distribution of a population of neurons that project to the necklace glomeruli at the posterior margins of the glomerular sheet; a large percentage of these atypical or necklace neurons also stain heavily with the mouse monoclonal antibody designated MAb213 (Ring et al., 1997). Accordingly, we performed double labeling with anti-Pax6 and MAb213 to assess the possibility that these densely Pax6 (+) cells are necklace neurons (Fig. 12). Indeed, we found that most of the strongly Pax6 (+) cells located in the ventral part and cul-de-sac regions of the OE are also labeled by MAb213, and are presumptive necklace neurons. In keeping with that identification, the MAb213 (+)/Pax6 (+) cells elaborate apical and basal processes that resemble dendrites and axons respectively and not the inverted flask shape of the Sus cells. Indeed, this population of neurons can be recognized on the basis of intense anti-β-gal labeling in transgenic mice in which LacZ has been knocked into, and renders null, the Pax6 locus (A.I. Packard and J.E. Schwob, unpublished results). Labeled neurons in the heterozygous ΔPax6-LacZ mice are concentrated in the posterior cul de sacs, and individual labeled axons and small bundles of them are evident in the nerve fascicles deep to the OE and can be followed to the olfactory bulb (ibid). Some of the Pax6 (+) neurons are not stained by MAb213. We suspect that the Pax6 (+)/MAb213 (−) neurons are another subgroup of necklace neurons despite lacking the MAb213 epitope, since MAb213 (−) necklace neurons have been demonstrated previously (Ring et al., 1997).

DISCUSSION

The work presented here describes in detail the expression of the transcription factors Pax6 and Sox2 within the OE of normal and lesioned adult rats. Our results demonstrate that Pax6 and Sox2 are co-expressed by multiple morphologically and functionally different cell groups in OE, including sustentacular cells, HBCs and the same subgroups of GBCs. Pax6 is also expressed in Bowman's gland/duct cells and necklace neurons. Our conclusion that the two transcription factors are expressed by some GBCs is based on four observations: first, Pax6 and Sox2 label a subset of cells positioned superficial to marker-identified HBCs; second, Pax6 (and by extension Sox2) labels some dividing basal cells, the vast majority of which are GBCs; third, Pax6 is co-expressed with Mash1, a marker of GBCs that likely serve as transit amplifying cells within the neuronal lineage, and with Neurog1 in some of those GBCs; and fourth, all basal cells co-express Pax6 and Sox2 at 1 and 2 days after MeBr lesion of the rat OE, at which time the majority of basal cells in the rat are GBCs.

The post-lesion observations also clarify which subsets of GBCs express Pax6 and Sox2. GBCs present at 1 d after lesion express neither Mash1 protein (present results), nor Mash1, Neurog1, nor NeuroD1 mRNAs (Manglapus et al., 2004). Thus, Pax6 and Sox2 labeling at 1 d after lesion implies that GBCs upstream of Mash1 are also Pax6/Sox2 (+); lineage tracing by retroviral transduction indicates that GBCs are also multipotent at this time-point post-MeBr (Huard et al., 1998). Not all GBCs label with Sox2/Pax6. Many Neurog1 (+) GBCs label with neither marker. In addition, the contemporaneous appearance of Neurog1-expressing GBCs (Manglapus et al., 2004) and Pax6/Sox2 (−) GBCs (present data) beginning 3 d after MeBr lesion is consistent with the failure to demonstrate complete overlap of Pax6/Sox2 and Neurog1in the neurogenic OE. Finally, we have demonstrated that the intensely Pax6-labeled cells positioned midway along the apical-basal axis of the ventral OE and in the cul-de-sacs bordering the cribriform plate are actually neurons that innervate necklace glomeruli at the posterior margin of the bulb, as shown by their co-labeling with MAb213, a known marker for necklace neurons (Ring et al., 1997).

Papers published while this work was in progress have described Sox2 expression by cells of the olfactory placode/pit and in the developing OE in slightly later stage embryos (Donner et al., 2007; Kawauchi et al., 2009), but a determination of the identity of Sox2-expressing basal cells with reference to known basal cell subtypes has been lacking. Expression of Pax6 has been described previously in the adult OE and our results are perfectly congruent with the observations made previously (Davis and Reed, 1996). However, we have used a more extensive panel of cell-type specific markers to characterize the cells expressing Pax6 and Sox2. As a consequence, our interpretation of the Pax6-expression pattern differs from that of the previous report, which used morphological criteria to assign Pax6 exclusively to HBCs among the basal cells. In contrast to this prior assignment, Pax6 is shown here to be expressed by selected subsets of GBCs in addition to HBCs. Likewise, by using markers characteristic of necklace neurons, we concluded that the Pax6 (+) cells located in the middle of the OE are indeed necklace neurons and not Sus cells migrating toward the apex of the OE as was suggested on morphological grounds before.

What might be the function(s) of Sox2 and Pax6 in these several cell types of the OE or in the other parts of the nervous system where they are expressed? Both transcription factors have been studied extensively in multiple cell types of multiple tissues at multiple stages during development from the embryo into adulthood. Taken together, the results imply that Pax6 and Sox2 are central players in the elaboration of tissue fields in the embryo – e.g., in the placodes contributing to the eye and the nose (Collinson et al., 2003; Donner et al., 2007; Grindley et al., 1995); in the regulation of primitive multipotent progenitors in several tissues – e.g., in the neural stem cells of the embryonic and adult CNS (Blake et al., 2008; Brazel et al., 2005; Ellis et al., 2004; Graham et al., 2003; Marquardt et al., 2001; Osumi et al., 2008; Pevny and Placzek, 2005; Taranova et al., 2006); and in driving the expression of structural proteins by differentiating cells – e.g., the regulation of lens δ-crystallin expression (Kamachi et al., 2001; Kondoh et al., 2004; Muta et al., 2002). The latter case is particularly instructive, as Pax6 and Sox2 have been shown to cooperate by binding to adjacent motifs in the promoter region of the target genes in order to drive crystallin expression (Kamachi et al., 2001); indeed, a cooperative interaction with another transcription factor seems to be a general requirement for Sox2 function.

The cell biological roles of Pax6 and Sox2 have been most thoroughly studied in the regulation of stem and progenitor cells. Sox2 is well known as one of the key factors in the regulation of embryonic stem cell self-renewal and in the formation of induced pluripotent cells, in which setting it partners with Oct4 (the product of the POU5F1 gene) to control a number of target genes in trans (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006). Likewise, Sox2 is required for the elaboration of multipotent tissue stem cells that emerge from the inner cell mass of the early embryo (Avilion et al., 2003). For example, Sox2 is expressed by neuronal progenitors/stem cells along the entire neuraxis from the neural plate stage onward, including the embryonic ventricular zone and the subventricular zone from its emergence onward into adulthood (Pevny and Placzek, 2005). As in the OE, the population of Sox2-expressing CNS progenitors is heterogeneous, with respect to locale, marker expression, and potentially differentiation capabilities. By means of genetic disruption, Sox2 has been shown to be key to the capacity of retinal progenitors both to proliferate and to differentiate (Taranova et al., 2006), and for ongoing neurogenesis in the postnatal dentate gyrus (Cavallaro et al., 2008; Favaro et al., 2009). In the latter setting, conditional elimination of Sox2 using a nestin-driven recombinase does not produce a phenotype in the hippocampus until birth (Cavallaro et al., 2008; Favaro et al., 2009); the stage-dependence of the effect suggests that other members of the SoxB1 subfamily, i.e., Sox1 and Sox3, may compensate for the loss of Sox2 before birth in this setting, though not in the retina. Interestingly, preliminary microarray analysis suggests that Sox1 and Sox3 are not prominent in the various cell types of the OE where Sox2 is expressed (R.C. Krolewski, A.I. Packard, N. Schnittke, and J.E. Schwob, unpublished results). Conversely, constitutive overexpression of Sox2 in chick neural tube (where Sox2 is accompanied by Pax6 or Pax7 in most of the dorsoventral extent of the tube) is sufficient by itself in blocking neuronal differentiation and maintaining cells as proliferating progenitors (Graham et al., 2003). Similarly, over-expression of Sox2 in cultured neocortical progenitors blocks neurogenesis and promotes glial differentiation acting through the Notch signaling pathway (Bani-Yaghoub et al., 2006). Whether Sox2 directly inhibits the genes underlying neuronal differentiation or accomplishes its inhibition by sustaining progenitor cell proliferation, remains unclear. That highly differentiated, largely quiescent, non-neuronal cells of the OE express Sox2 at high (Sus cells) or moderate (HBCs) levels suggests that inhibition of neuronal differentiation remains a plausible component of Sox2’s effects in the OE as well as in the CNS.

Pax6 (and Pax family members, more generally) also seems to play a key role in regulating certain categories of stem and progenitor cells. From the neuroepithelium stage onward throughout postnatal neurogenesis Pax6 is expressed coincident with Sox2 in the ventricular, and eventually the subventricular, zone of the telencephalon (Osumi et al., 2008; Pevny and Placzek, 2005). Here, Pax6 precedes and is excluded from cells in the ventricular/subventricular zone expressing downstream pro-neurogenic transcription factors, in this case Neurog2 (Osumi et al., 2008). Pax6 levels are highest in more primitive cells of the ventricular zone and then decline with the progression to transit amplifying cells (Sansom et al., 2009), much as is seen here in the OE. In the primordial neocortex Pax6 binds to and regulates a wide array of genes, which play complex and sometimes off-setting roles in the progression from neural stem cell to differentiating neuron (Sansom et al., 2009; Simpson and Price, 2002). For example, in the absence of Pax6 telencephalic stem cells and progenitor cells exit the cell cycle, forego self-renewal, and undergo premature neuronal differentiation, leading to a thinned cortex, while up-regulation of Pax6 can also result in a thinner cortex but by means of a different mechanism (Sansom et al., 2009). Thus, context strongly influences Pax6 function in telencephalic progenitors. It may be easier to parse Pax6 roles in the simpler setting of olfactory neurogenesis. For example, the co-expression with Mash1 and partial overlap with Neurog1 suggests that Pax6 does not block commitment to a neuronal fate in the OE. Beyond its role in stem and progenitor cells, Pax6 also contributes to the diversification of neuron types in the neural tube (Ericson et al., 1997; Osumi et al., 1997; Timmer et al., 2002) and to the differentiation to tyrosine hydroxylase-expressing periglomerular neurons of the olfactory bulb (Baltanas et al., 2009; Hack et al., 2005; Kohwi et al., 2005; Stoykova and Gruss, 1994), which is reminiscent of the intense expression of Pax6 in the necklace neurons.

The requirement that Sox and Pax genes complex with each other or another transcription factor seems to be a general one. Besides the partnering of Sox2 and Pax6 to regulate crystallin expression referenced above, stem cells of the melanocytic lineage, as well as the formation of the enteric ganglia, are regulated by the co-expression of Pax3 and Sox10 (Blake et al., 2008; Lang et al., 2005). Their role in melanocytic stem cells is particularly apposite; Pax3 acts with Sox10 to initiate the melanogenic cascade, but also acts downstream to prevent terminal differentiation in the absence of the other transcription factor (Lang et al., 2005). Whether the co-expressed Sox2 and Pax6 act together in cells of the OE to regulate gene expression awaits the development of a more facile system for analysis of transcription factor binding and function in the epithelium.

In sum, two transcription factors – Pax6 and Sox2 – that act separately and often together in regulating self-renewal and differentiation of stem cells and progenitor cells in the nervous system are expressed in a complex array of cells in the OE. The roles of Pax6 and Sox2 in the cellular economy of the epithelium are likely to be multifaceted, but their expression in some GBCs and HBCs that are thought to act as stem cells in this tissue suggest that both transcription factors will be key to the maintenance of neurogenesis and the neuroepithelium’s remarkable capacity for recovery from injury throughout life.

Supplementary Material

Figure 14.

Expression of Sox2 and Pax6 in OE from bulbectomized rats is similar to normal, although more GBCs are labeled. A–E) Anti-Sox2 staining at various time points after olfactory bulbectomy. A’–E’) Anti-Pax6 staining at various time points after olfactory bulbectomy. Note the larger population of Sox2 (+) and Pax 6 (+) basal cells at 7, 10 and 21 days after bulbectomy by comparison with the normal control. Note also the intensely stained Pax6 (+) cells within the neuronal layer of the OE at 21 days after bulbectomy, which correspond to necklace neurons. Arrowheads mark the basal lamina. Scale bar in E’ is 50 µm and also applies to the other panels.

Figure 15.

The cells that are intensely Pax6 (+) in the neuronal zone of the OE label with a marker of, and are presumably, necklace neurons. Double-stained section of normal rat OE in a location on the ventral septum. A) Anti-Pax6 staining; the intensely positive cells situated in the neuronal layers of the OE are indicated by arrows. C) Staining with monoclonal antibody MAb213, which marks necklace neurons. Note the apical and basal processes, which resemble dendrites and axons, respectively. B) Merged image of Pax6 and MAb213 staining. Arrowheads mark the basal lamina. Scale bar in C is 25 µm and also applies to the other panels. A magenta-green version of this figure is available online as Supplementary Figure 11.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants R01 DC002167 (JES) and F30 DC010276 (RCK) from the National Institutes of Health

LITERATURE CITED

- Abercrombie M. Estimation of nuclear population from microtome sections. Anat Rec. 1946;94(2):239–247. doi: 10.1002/ar.1090940210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avilion AA, Nicolis SK, Pevny LH, Perez L, Vivian N, Lovell-Badge R. Multipotent cell lineages in early mouse development depend on SOX2 function. Genes Dev. 2003;17(1):126–140. doi: 10.1101/gad.224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltanas FC, Weruaga E, Murias AR, Gomez C, Curto GG, Alonso JR. Chemical characterization of Pax6-immunoreactive periglomerular neurons in the mouse olfactory bulb. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2009;29(8):1081–1085. doi: 10.1007/s10571-009-9405-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bani-Yaghoub M, Tremblay RG, Lei JX, Zhang D, Zurakowski B, Sandhu JK, Smith B, Ribecco-Lutkiewicz M, Kennedy J, Walker PR, Sikorska M. Role of Sox2 in the development of the mouse neocortex. Dev Biol. 2006;295(1):52–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake JA, Thomas M, Thompson JA, White R, Ziman M. Perplexing Pax: from puzzle to paradigm. Dev Dyn. 2008;237(10):2791–2803. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazel CY, Limke TL, Osborne JK, Miura T, Cai J, Pevny L, Rao MS. Sox2 expression defines a heterogeneous population of neurosphere-forming cells in the adult murine brain. Aging Cell. 2005;4(4):197–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2005.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiano M, Kauer JS, Hunter DD. Globose basal cells are neuronal progenitors in the olfactory epithelium: a lineage analysis using a replication-incompetent retrovirus. Neuron. 1994;13(2):339–352. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancalon P. Degeneration and regeneration of olfactory cells induced by ZnSO4 and other chemicals. Tissue Cell. 1982;14(4):717–733. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(82)90061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr VM, Farbman AI. The dynamics of cell death in the olfactory epithelium. Exp Neurol. 1993;124(2):308–314. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr VM, Farbman AI. Ablation of the olfactory bulb up-regulates the rate of neurogenesis and induces precocious cell death in olfactory epithelium. Exp Neurol. 1992;115(1):55–59. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(92)90221-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cau E, Casarosa S, Guillemot F. Mash1 and Ngn1 control distinct steps of determination and differentiation in the olfactory sensory neuron lineage. Development. 2002;129(8):1871–1880. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cau E, Gradwohl G, Fode C, Guillemot F. Mash1 activates a cascade of bHLH regulators in olfactory neuron progenitors. Development. 1997;124(8):1611–1621. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.8.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro M, Mariani J, Lancini C, Latorre E, Caccia R, Gullo F, Valotta M, DeBiasi S, Spinardi L, Ronchi A, Wanke E, Brunelli S, Favaro R, Ottolenghi S, Nicolis SK. Impaired generation of mature neurons by neural stem cells from hypomorphic Sox2 mutants. Development. 2008;135(3):541–557. doi: 10.1242/dev.010801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Fang H, Schwob JE. Multipotency of purified, transplanted globose basal cells in olfactory epithelium. J Comp Neurol. 2004;469(4):457–474. doi: 10.1002/cne.11031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Schwob JE. Quiescent globose basal cells are present in the olfactory epithelium. Chem Senses. 2003;28:A5. [Google Scholar]