Abstract

Deregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is a hallmark of colon cancer. Mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene occur in the vast majority of colorectal cancers and are an initiating event in cellular transformation. Cells harboring mutant APC contain elevated levels of the β-catenin transcription coactivator in the nucleus which leads to abnormal expression of genes controlled by β-catenin/T-cell factor 4 (TCF4) complexes. Here, we use chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with massively parallel sequencing (ChIP-Seq) to identify β-catenin binding regions in HCT116 human colon cancer cells. We localized 2168 β-catenin enriched regions using a concordance approach for integrating the output from multiple peak alignment algorithms. Motif discovery algorithms found a core TCF4 motif (T/A–T/A–C–A–A–A–G), an extended TCF4 motif (A/T/G–C/G–T/A–T/A–C–A–A–A–G) and an AP-1 motif (T–G–A–C/T–T–C–A) to be significantly represented in β-catenin enriched regions. Furthermore, 417 regions contained both TCF4 and AP-1 motifs. Genes associated with TCF4 and AP-1 motifs bound β-catenin, TCF4 and c-Jun in vivo and were activated by Wnt signaling and serum growth factors. Our work provides evidence that Wnt/β-catenin and mitogen signaling pathways intersect directly to regulate a defined set of target genes.

INTRODUCTION

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is required for homeostasis in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (1). The GI tract is coated with small invaginations, or crypts, which are comprised of discrete zones of proliferating and differentiated cells (1). Wnt signaling maintains the proliferative compartment of the crypt. The β-catenin transcriptional coactivator controls downstream genetic programs elicited by Wnt signaling and its cellular levels are tightly regulated (2,3). When cells are not exposed to Wnt, cytosolic β-catenin associates with a multi-protein complex that contains the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) protein. APC functions as a scaffold to coordinate β-catenin phosphorylation and degradation by the proteasome. Under these conditions, Wnt/β-catenin target genes are silenced by corepressor complexes that are tethered to Wnt responsive DNA enhancers (WREs) through interactions with the T-cell factor (TCF) family of transcription factors (4). TCF4 is a predominant TCF family member in colon cancer cells (5). When cells are exposed to Wnt, β-catenin escapes proteasomal degradation, and is chaperoned to the nucleus by APC. There, it occupies TCF4 bound WREs and displaces the corepressors. β-catenin then recruits chromatin-modifying complexes and Wnt/β-catenin target genes are expressed (4).

Deregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is associated with colon carcinogenesis (2,3). In virtually all cases of colon cancer, mutations target components of the Wnt signaling pathway (6). The most common lesions localize to APC and lead to production of a truncated APC protein that can no longer effectively coordinate β-catenin degradation. This mutation occurs at the earliest stages of carcinogensis when normal colonic epithelial cells are transformed into aberrant crypt foci (6). Inherited APC mutations give rise to familial adenomatous polyposis, a disease where afflicted individuals are burdened by thousands of intestinal polyps early in adulthood (7,8). In the rare cancer cases where APC is wild-type, mutations instead are found in CTNNB1 (3,9,10). CTNNB1 is the gene that encodes β-catenin, and the cancer causing lesions map to positions near the 5′ portion of the gene. These mutations give rise to a β-catenin pool that is resistant to proteasomal degradation (11). In each instance, mutations that target APC or CTNNB1 lead to high levels of β-catenin in the nucleus and abnormal expression of genes regulated by β-catenin/TCF4 complexes (5,9). Therefore identifying target genes directly controlled by β-catenin/TCF4 is required to understand the pathogenesis of this disease.

To identify direct β-catenin/TCF4 target genes it is first necessary to map binding sites for these factors across the genome. Previously, we used an unbiased and genome-wide screen termed serial analysis of chromatin occupancy (SACO) to localize 412 high confidence β-catenin binding sites in the human colorectal cancer cell line, HCT116 (12). Approximately half of the binding sites were near (<2.5 kb) or within protein-coding gene boundaries. These β-catenin binding sites were located in 5′ promoter regions, intragenic regions and 3′ untranslated regions. β-Catenin binding to 3′ positions relative to E2F4 and MYC genes identified functional WREs. For E2F4, the downstream enhancer drove expression of an antisense and non-coding transcript that decreased E2F4 protein levels (13). For MYC, β-catenin occupancy of the downstream enhancer initiated a chromatin loop that integrated the 5′ WRE to coordinate MYC expression in response to Wnt/β-catenin and mitogen signaling pathways (14,15). Recently, Hatzis et al. (16) used chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) coupled with microarrays (ChIP-chip) to localize 6868 TCF4 binding sites in L171 colorectal cancer cells (16). As was the case for β-catenin, TCF4 binding was also found throughout protein coding gene boundaries. Together these studies indicate that Wnt activation of target gene expression is mechanistically more intricate than the simple model involving recruitment of β-catenin to TCF4-bound 5′ promoter regions.

While SACO was a pioneering technique used to identify transcription factor binding sites and was a viable alternative to the ChIP-chip approach, it did, like most methodologies, suffer from some limitations. First, SACO libraries were constructed in plasmid vectors and then sequenced using high-throughput and Sanger-based sequencing. This was both laborious and costly. In addition, large DNA fragments were included in construction of the earliest SACO libraries. While most DNA was in the 500–700 bp range, fragments as large as 2.5 kb were included in the β-catenin SACO library. This impinged upon the resolution of the technique and hindered de novo motif discovery within β-catenin bound loci. A successor to SACO is the recently described ChIP coupled with massively parallel sequencing (ChIP-Seq) approach (17–19). In this technique, DNA purified from immunoprecipitated chromatin is size-selected and then sequenced using one of the next-generation sequencing platforms such as the Illumina genome analyzer (18,19). The robustness, cost, resolution and relative ease in library construction has made ChIP-seq, rather than SACO, a current method of choice for genome-wide localization of transcription factor binding sites. ChIP-Seq has been used to map numerous histone modifications (20) and binding sites for several transcription factors including, but not limited to, NRSF/REST, GATA1, SRF, E2F4, E2F6 and STAT1 (17). In addition, ChIP-Seq has been used recently to identify TCF4 enriched binding regions in human colon cancer cell lines (21,22). Tuupanen et al. (22) identified 10 TCF4-site containing regions in LoVo cells using a combination of ChIP-Seq and the enhancer element locator analysis. Blahnik et al. (21) used ChIP-Seq to identify 21 102 TCF4 binding sites in HCT116 cells.

In this report we used ChIP-Seq to identify β-catenin binding regions in HCT116 human colon cancer cells. We chose this high-resolution and genome-wide approach because we were interested in using de novo motif analysis to identify transcription factors that putatively cooperate with β-catenin/TCF4. Many algorithms exist to map the enriched genomic regions identified in a ChIP-Seq experiment (23). Because each approach varies in computational strategy and can produce dramatically different numbers of enriched regions for a given false discovery rate (FDR) cutoff, there is some debate as to which is the preferred algorithm (18). In this report, we used CisGenome (24), SISSRs (25) and WTD (26) to initially identify enriched regions from the β-catenin ChIP-Seq library. Based on the intersection of regions found in common with each algorithm, we identified 2168 β-catenin enriched regions. Consistent with our previous report (12), we found over-representation of the core and evolutionarily conserved TCF4 consensus motifs within enriched regions. In addition, we found that consensus AP-1 motifs were also over-represented in a large subset of the enriched regions with the majority of these motifs co-occurring with a TCF4 motif. Finally, we show that serum mitogens and Wnt signaling agonists cooperatively activate expression of some target genes in proximity to β-catenin bound loci that contain AP-1 and TCF4 motifs. These findings indicate that a discrete subset of β-catenin target genes are activated by mitogen and Wnt signaling in colon cancer cells, and that this regulation likely occurs through consensus AP-1 and TCF4 sites, respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

HCT116 human colorectal cancer cells (ATCC number CCL-247) were cultured as previously described (14).

ChIP

Antibodies used in ChIP assays included: 3 µg of anti-β-catenin (BD transduction, 610154), 3 µg of anti-TCF4 (Millipore, 05-511), 2 µl of anti-c-Jun (Millipore, 06-225) and 6 µg rabbit anti mouse IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch, 315-005-003). β-Catenin ChIP DNA for the ChIP-Seq library was prepared using the Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay Kit (Millipore, 17-295) according to the instructions. To assess β-catenin, TCF4 and c-Jun binding to ChIP-Seq peak loci, ChIP assays contained 5–10 × 106 cells and were conducted as previously reported (13). Chromatin in formaldehyde fixed cell lysates was sonicated to an average size of 500–700 bp using a Misonix Ultrasonic XL-2000 Liquid Processor (5 × 20 s, output wattage 7, with 45 s rest intervals on ice between pulses). Real time PCR was used to detect isolated ChIP fragments and samples contained 10 µl of 2 × iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-rad, 170-882), 0.25 µM of each primer and 3 µl of purified ChIP DNA. Reactions were processed for one cycle at 94°C for 3 min, then 45 cycles at 94°C for 10 s and at 68°C for 40 s using a MyIQ Single Color Real-Time PCR machine (Bio-rad). Primers were designed, using Primer3 software, to a 600 bp DNA segment that was centered on the β-catenin ChIP-Seq coverage region. Primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S7. Real time data is represented as fold levels over control. The control is a distal region that is 5 kb upstream from the MYC transcript start site that does not bind significant levels of β-catenin, TCF4 or c-Jun (14).

Construction of the ChIP-Seq library

β-Catenin precipitated and purified ChIP DNA (350 ng) was processed using the ChIP-Seq DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, 1003473) according to instructions provided by the manufacturer. Prior to sequencing, DNAs were re-quantified using a NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer and the quality of DNA was assessed using a Bioanalyzer DNA 1000 (Agilent). Samples were diluted to 10 nM and 54-nt reads were obtained from one lane of sequencing on a Illumina GA II sequencer. The High Throughput Sequencing Facility at the University of Oregon (http://htseq.uoregon.edu) sequenced the library. Raw sequence data was submitted to the sequence read archive (SRA) under accession number SRA012054.

Realignment of ChIP-Seq reads

Reads (9 322 654) were sequenced and of these, 8 456 287 passed the quality filter as assessed using ELAND software (Illumina). We then used ELAND to align the 8 456 267 reads to the repeat masked NCBI 36/hg18 build of the human genome. We assigned unique positions for 6 576 033 reads allowing up to two mismatches in the first 32 bases of the read sequence. This set of reads was retained for downstream computational analysis.

Identification of β-catenin enriched regions

We utilized three peak calling programs to define a set of putative binding regions: CisGenome (24), SISSRs (25) and WTD (26). Each method implements variations on a sliding window approach to identify regions of higher read depth, referred to as peaks, relative to a background distribution. Based on the particular algorithm, background distributions are derived using reads from a negative control experiment, through monte carlo procedures, or through statistical models (23). CisGenome and SISSRs rely on statistical model fitting while the WTD method uses a randomization approach. SISSRs was run using a window size of 20 bases with the FDR set at 0.01. WTD was run with the window size estimated from the binding characteristics. Any local tag anomalies were removed and an FDR cutoff of 0.01 was assessed using 10 randomization procedures. CisGenome was run using a window size of 100 and a read cutoff of 7 reads. We then identified the midpoints of each of the regions and extended 299 bp upstream and 300 bp downstream so that there was a total of 600 bp identifying each putative binding region. We chose 600 bases because it was twice what we considered to be the largest size of DNA fragments submitted for sequencing (Figure 1B). Using these criteria, CisGenome, SISSRs and WTD called 100 372, 80 733 and 2940 peak regions, respectively. Peaks called in common by the three algorithms yielded 2168 putative β-catenin binding regions and this set was used for further computational analysis (See Supplementary Table S1 for a summary of peak overlaps).

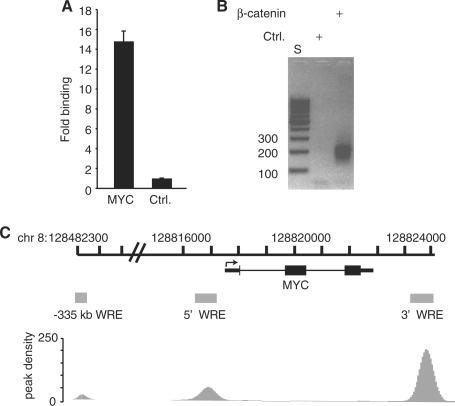

Figure 1.

Generation of a β-catenin ChIP-Seq library in HCT116 human colorectal carcinoma cells. (A) Real-time PCR analysis of DNA fragments isolated from a ChIP assay using a β-catenin specific antibody. Specific oligonucleotides were used to detect binding to a WRE downstream of the MYC transcription stop site (14,15). A region 5 kb upstream from the MYC promoter that does not associate with β-catenin/TCF4 complexes (Ctrl) served as a negative control (14). Data is presented as fold-binding relative to control and error is SEM. (B) Agarose gel analysis of size selected and PCR amplified β-catenin ChIP DNA used for Illumina high-throughput sequencing. S is a DNA standard and Ctrl is a negative control for PCR amplification (see ‘Materials and Methods’ Section). (C) Schematic of the MYC locus. Thin rectangles are untranslated regions, thick rectangles are exons, thin lines are introns and the arrow is the transcription start site. Gray shaded boxes are β-catenin enriched regions that were identified in the ChIP-Seq library which overlap 5′, 3′ and −335 kb WREs (14,22,29). Peak density plots for β-catenin enriched regions are depicted below the WREs.

Generation of peak images

Images of the peaks were generated using the SPP package (26). Total read counts were smoothed using a Gaussian kernel with a step size of 50 and a bandwidth of 200. Values were written to a WIG file and visualized in the UCSC genome browser.

De novo motif analysis

The genomic sequence (600 bp) encompassing each enriched region was isolated and the regions were separated into two sets based upon whether they had at least one instance of a canonical (T/A–T/A–C–A–A–A–G) or evolutionarily conserved (A–C/G–T/A–T–C–A–A–A–G) TCF4 motif within the boundaries of the region (16). The reverse complements of these sequences were also included. The sequence from each region was repeat masked and used as input into the Gibbs sampler motif finding program provided by CisGenome. The motif finder was run searching for motifs of 7, 11 and 15 bp using 5000 MCMC iterations and a score was produced for each motif. Control sequences were picked based on the strategy of Ji et al. (27). Briefly, sequences were chosen to match the underlying characteristics of the enriched regions. Each control sequence was picked randomly such that it was of the same size and was in the same position relative to the nearest RefSeq transcript (28) as a given enriched region. Five sets of control sequences were chosen in this manner for both sets of enriched regions. Motifs found from the de novo search were mapped back to both the β-catenin enriched regions and the control sequences using the motif mapping tool from CisGenome. The number of matches were based on a likelihood ratio cutoff of 500 and a background model consisting of a third-order markov chain, in accordance with Ji et al. (27). The relative enrichment was computed as described (27). Motifs that had a relative enrichment score >2 were determined to be over-represented in the β-catenin enriched regions.

Chromatin conformation capture

Chromatin conformation capture (3C) assays were conducted as described (15) with minor modifications. Formaldehyde cross linked chromatin was digested overnight with 40 µl (800 U) of XbaI (New England Biolabs). XbaI was then heat-inactivated at 65°C for 20 min prior to ligation reactions. After proteinase K treatment, the samples were extracted in phenol/chloroform three times, followed by three back extractions with chloroform. The chromatin loop at CXXC5 was detected by PCR using primers C51, GTACGTAGTCGTTTTAGCC and C56, GCACCCAGCCTCTCAAACCC and the conditions previously described (15). To control for loading, parallel samples were amplified by PCR with the tubulin specific primers GGGGCTGGGTAAATGGCAAA and TGGCACTGGCTCTGGGTTCG. Products were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel by electrophoresis, purified and sequenced.

Serum and LiCl stimulation of HCT116 cells

HCT116 cells were synchronized in the cell cycle as previously described (14). For ChIP experiments, G0/G1 cells grown in a 10-cm tissue culture dish were stimulated with medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum for 1 or 2 h prior to formaldehyde fixation. For expression analysis, G0/G1 cells were grown in a 6-well plate prior to stimulation with medium containing serum with and without 10 mM LiCl for 1 or 4 h as indicated.

Reverse transcription/real time PCR

RNA was isolated using TRIZol reagent (Invitrogen, 15596-018) according to the instructions. cDNA was synthesized using 500 ng of total RNA and the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-rad, 170-8890) according to the instructions. cDNA was diluted to 1: 150 before quantification by real-time PCR. Real-time PCR was conducted as outlined under the ChIP section, except 3 µl of diluted cDNA was used as the template. Primers were designed using Primer3 software and their sequences are included in Supplementary Table S7.

RESULTS

Construction of the β-catenin ChIP-Seq library

We were interested in using ChIP coupled with massively parallel sequencing (ChIP-Seq) to identify β-catenin binding regions in HCT116 human colon cancer cells. Prior to constructing the library, we tested the efficacy of our ChIP protocol to identify bona fide β-catenin targets in this cell line. β-catenin strongly associated with a WRE located 1.4 kb downstream of the transcription stop site of the c-Myc gene (MYC) as we have reported previously (Figure 1A) (14,15). Furthermore, insignificant levels of β-catenin were detected at a control element located 5 kb upstream of the MYC transcription start site that did not associate with either β-catenin or TCF4 (Figure 1A) (14). Size-selected β-catenin ChIP DNA was then processed according to the Illumina sample preparation protocol and minimally amplified by PCR. Most amplified fragments were in the range of 175–225 bp and were produced in samples containing β-catenin ChIP DNA whereas these products were absent in the control sample (Figure 1B). A total of 9 322 654 reads were generated from one lane of sequencing using an Illumina GA II high throughput sequencer. Of these, ∼90.7% (8 456 287) passed the quality filter and ∼77.8% (6 576 033) reads were assigned a unique position in the human genome. The set of 6 576 033 reads was then subjected to additional computational analysis.

As outlined in the ‘Materials and Methods’ section, we compared three computational algorithms and we considered the peaks called in common to demarcate putative β-catenin binding regions. This approach yielded 2168 peaks that we termed β-catenin enriched regions. The genomic boundaries of these regions are provided in Supplementary Table S2. To determine whether our approach identified bona fide Wnt/β-catenin target genes, we searched for representation of the MYC gene. β-catenin enriched regions coincided with the 5′, 3′ and distal WREs previously shown to regulate MYC expression (Figure 1C) (15,22,29–31). Thus, our approach identified β-catenin associated WREs in colon cancer cells.

Computational analysis of β-catenin enriched regions

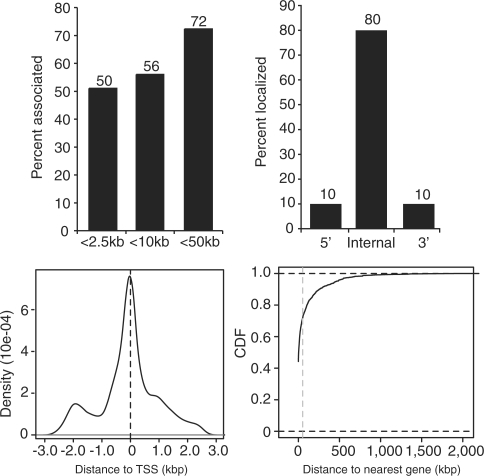

We next localized the β-catenin enriched regions relative to transcripts deposited in the reference sequence database (RefSeq) (28). Of the 2168 β-catenin enriched regions, 1562 (72%) were within 50 kb of a RefSeq transcript. Upon further analysis, we found that 1219 (56%) were within 10 kb and 1090 (50%) were within 2.5 kb (Figure 2A). With respect to protein-coding genes and in agreement with our previous findings (12), we found that β-catenin preferentially localized to internal positions or those positions that are downstream from the transcription start site and upstream from the transcription stop site (Figure 2B). There was a tendency for β-catenin enriched regions within 2.5 kb of the 5′ gene boundary to cluster around transcriptional start sites (Figure 2C). The genes containing β-catenin enriched regions near (<2.5 kb) or within gene boundaries are listed in Supplementary Table S3. Overall, the 1090 β-catenin enriched regions are near or within 988 genes.

Figure 2.

Distribution of β-catenin enriched regions within the ChIP-Seq library. Sequenced DNA fragments that passed quality control were mapped to the NCBI 36/hg18 build of the human genome using ELAND software. β-catenin enriched regions were identified as described in the methods. (A) Histogram showing the percentage of enriched regions that localized within 2.5, 10 or 50 kb of a protein-coding gene boundary as defined by the RefSeq library (28). (B) Histogram representing percentage of enriched regions that localized upstream (5′), within (internal) or downstream (3′) of a RefSeq gene. For 5′ and 3′ categorizations, the enriched regions were <2.5 kb from each respective boundary. (C) Density plot depicting the distribution of enriched regions that are ±2.5 kb from a RefSeq transcription start site. (D) Empirical CDF plot representing the distance of each β-catenin enriched region to its nearest protein-coding gene boundary. The gray vertical line indicates 50 kb.

It was recently shown that a distal WRE interacted with MYC through a large chromatin loop (30,31). This was the first demonstration indicating that a WRE positioned hundreds of kilobases away from their target genes functioned as a transcriptional enhancer. To further explore the relationship of β-catenin enriched regions and annotated protein-coding transcripts, we determined the empirical cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the distance from each β-catenin enriched region to the nearest transcript. This analysis found that 80% of enriched regions were within 100 kb of an annotated transcript and that 95% were within 450 kb (Figure 2D). Together these findings indicate that while most β-catenin regions are near or within protein-coding genes, 28% localized at a distance of >50 kb away. Furthermore, localization of β-catenin enriched regions with gene boundaries was statistically significant when compared to localization of a control set of regions with gene boundaries (Supplementary Figure S1).

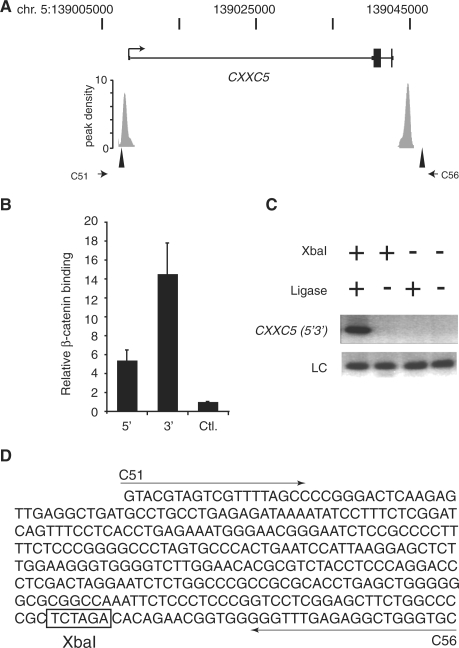

β-Catenin occupancy of 5′ and 3′ regions at CXXC5 identified a chromatin loop

Recently we described a β-catenin and TCF4-coordinated chromatin loop at MYC that integrated 5′ and 3′ proximal WREs (15). To identify targets that may be likewise regulated, we searched for genes that contained both 5′ and 3′ β-catenin enriched regions. In addition to MYC, we found two genes, CXXC5 and FXR2, that contained β-catenin enriched regions within 2.5 kb of both transcript boundaries (Supplementary Table S4 and Figure 3A). If the range was expanded to include regions 10 kb from the 5′ and 3′ ends, 11 loci were identified. This number increased to 111 loci if the range was further expanded to 50 kb. We first used ChIP and real-time PCR to determine whether β-catenin occupied the identified regions relative to CXXC5. β-catenin precipitated higher levels of the 5′ and 3′ CXXC5 enriched regions relative to control (Figure 3B). We then used chromatin conformation capture (3C) to determine whether a chromatin loop containing the 5′ and 3′ β-catenin associated regions formed at CXXC5 (32). Figure 3A depicts the positions of the XbaI restriction endonuclease sites and PCR primer locations used to interrogate CXXC5 in 3C assays. A PCR product of the correct size was generated with forward primer C51 and reverse primer C56, and its production was dependent upon the addition of XbaI and DNA ligase to the reaction (Figure 3C). This 341 bp fragment was sequenced and confirmed to be the correct CXXC5 product (Figure 3D). This analysis indicated that a chromatin loop containing β-catenin bound 5′ and 3′ WREs is present at CXXC5 in human colon cancer cells.

Figure 3.

A chromatin loop containing 5′ and 3′ β-catenin enriched regions is detected at the CXXC5 gene. (A) Schematic of the CXXC5 locus with untranslated regions as thin rectangles, introns as thin lines, exons as thick rectangles and an arrow demarcating the transcription start site. The peak density plots below the gene represent β-catenin enriched regions identified in the ChIP-Seq library. The triangles and stunted arrows identify the XbaI sites and PCR primers, respectively, used in the chromatin conformation capture (3C) assay depicted in (C). (B) Real time PCR analysis of β-catenin ChIP assays performed in HCT116 cells. Specific oligonucleotides were used to detect β-catenin binding to enriched regions depicted by gray rectangles in (A). 5′ is the upstream site and 3′ is the downstream site. A distal upstream region of the MYC gene was used as a negative control (Ctrl). Error bars are SEM. (C) Agarose gel of PCR products generated from a 3C analysis of CXXC5 in HCT116 cells. Generation of the 3C product (CXXC5 5′3′) with primers C51 and C56 required the addition of XbaI and ligase to the reactions. LC is a loading control and S is a DNA standard. (D) DNA sequence of the 3C product. Arrows denote primer sequences C51 and C56 and the XbaI site are boxed.

Motif analysis of β-catenin enriched regions

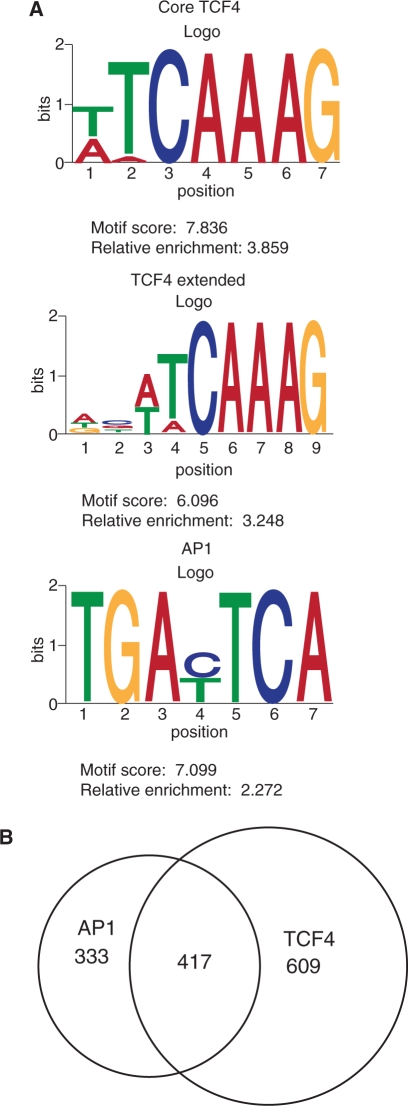

Genome-wide binding analysis has indicated that most β-catenin recruitment to chromatin in colon cancer cells likely occurred through interactions with TCF4 (12). Therefore, we first determined whether the β-catenin enriched regions contained a canonical TCF4 motif (T/A–T/A–C–A–A–A–G) or the evolutionarily conserved TCF4 motif (A–C/G–T/A–T–C–A–A–A–G) (16). Of the 2168 enriched regions, 1026 (47%) contained at least one TCF4 motif. A fraction of these, 192 (9%), resembled the longer and evolutionarily conserved variant. We then performed de novo motif analysis on these populations using a Gibbs sampler algorithm (24,27). Over-representation of motifs was determined by computing the relative enrichment measure as described in the ‘Materials and Methods’ section (27). Using the 1026 enriched-regions that contained TCF4 consensus sequences, we successfully identified an over-representation of both the core and evolutionarily conserved TCF4 motifs. This indicated that our de novo search approach was valid. Upon further analysis, we found a striking co-enrichment of AP-1 motifs with the consensus TCF4 motifs. Examples of all three motifs, along with their scores and enrichment values relative to control sequences, are shown in Figure 4A. Overall, 417 β-catenin enriched regions contained a TCF4 and an AP-1 motif (Figure 4B and Supplementary Table S5).

Figure 4.

DNA motifs within β-catenin enriched regions. (A) Sequence Logos for the identified motifs within β-catenin enriched regions as created by the CEQLOGO program (51). Motif scores and relative enrichment values were computed as in Ji et al. (27). (B) A Venn diagram depicting overlap between peak regions that contain AP-1 and TCF4 consensus motifs.

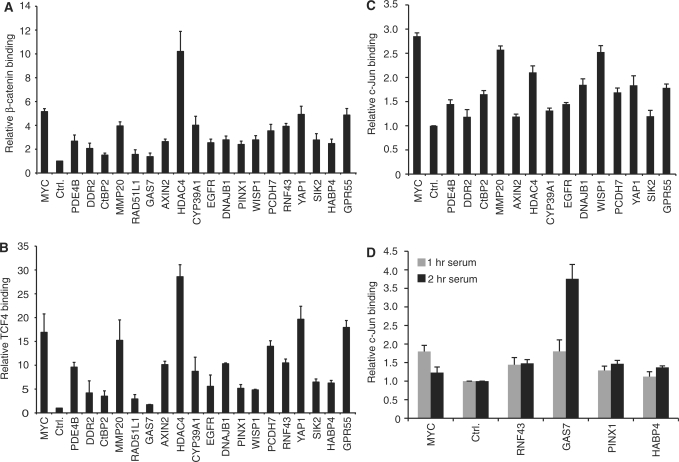

The coupling of AP-1 and TCF4 motifs in 417 (19%) β-catenin enriched regions suggested that AP-1, TCF4 and β-catenin may co-regulate target gene expression. To address this hypothesis, we used the ChIP assay to determine whether these factors bound regions containing AP-1 and TCF4 motifs. We first tested β-catenin binding to a selected subset of regions associated with 23 protein-coding genes. For this set of genes, associated regions were those that localized within 2.5 kb from gene boundaries. β-catenin occupied 19 sites in asynchronously growing HCT116 cells (Figure 5A). We then assayed the same regions for TCF4 binding using TCF4 specific antibodies in the ChIP assay. TCF4 bound the same 19 targets as β-catenin (Figure 5B). We concluded from this analysis that β-catenin and TCF4 co-occupied target genes containing TCF4 and AP-1 consensus motifs.

Figure 5.

β-catenin enriched regions containing AP-1 and TCF4 motifs associated with β-catenin, TCF4 and c-Jun. (A) Real-time PCR analysis of a ChIP assay conducted with β-catenin specific antibodies in HCT116 cells. Binding to enriched regions containing TCF4 and AP-1 consensus motifs was detected using specific oligonucleotides. MYC is the MYC 3′ WRE and Ctrl. is a control region 5 kb upstream of the MYC transcription start site (14). Data is presented as fold binding over control and error is SEM. In (B) and (C) ChIP assays were performed using anti-TCF4 or anti-c-Jun specific antibodies, respectively. (D) Serum-deprived HCT116 cells were cultured in media containing serum for 1 or 2 h as indicated prior to ChIP with c-Jun specific antibodies.

Next, we determined whether AP-1 bound to these selected regions. AP-1 is a heterodimeric complex comprised of Fos and Jun transcription factors (33,34). AP-1 regulates key cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis (35). Several groups have shown that c-Jun associates with AP-1 consensus motifs in colon cancer cells (14,36–39). We therefore tested whether c-Jun occupied β-catenin enriched regions containing AP-1 and TCF4 motifs. Using c-Jun antibodies in ChIP assays conducted in asynchronously growing HCT116 cells, we found that c-Jun associated with 14 of the 19 regions that bound β-catenin and TCF4 (Figure 5C). Serum mitogens elicit signal transduction pathways that stimulate c-Jun binding to chromatin. We have previously shown that c-Jun occupancy of the MYC 3′ enhancer increased as quiescent cells re-entered the cell cycle in response to serum (14). We therefore determined whether treatment of quiescent cells with serum would stimulate c-Jun association with the five targets that lacked binding in asynchronous cells. HCT116 cells were grown to confluency in serum-depleted medium for two days, which caused these cells to enter the G0/G1 stage of the cell cycle (14,39). Cells were then treated with medium containing serum for 1 or 2 h and c-Jun ChIP assays were conducted. In line with previous findings, higher levels of c-Jun were found at the MYC 3′ enhancer when synchronized cells were exposed to serum for 1 h as compared to levels detected in quiescent cells (Figure 5D) (14). When c-Jun binding was interrogated at the five ChIP-Seq targets, serum induced occupancy at regions associated with RNF43, GAS7, PINX1 and HABP4 (Figure 5D). RAD51L1 did not associate with c-Jun. Thus in total, 18 of the 19 β-catenin enriched regions containing TCF4 and AP1 motifs associated with β-catenin, c-Jun and TCF4.

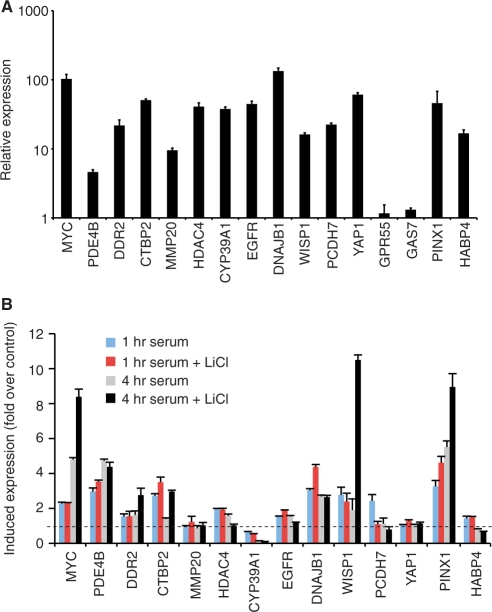

We then tested whether Wnt/β-catenin and mitogen signaling pathways converged to activate genes bound by AP-1, β-catenin and TCF4. First, we profiled RNA levels for 15 genes in asynchronously dividing HCT116 cells using reverse transcription coupled to real-time PCR. Expression of each gene was readily detected with GAS7 and GPR55 expressed at reduced levels (Figure 6A). As these cells contain high levels of nuclear β-catenin and are cultured in medium containing serum, this result does ascertain the relative contribution of mitogen and Wnt/β-catenin pathways to gene expression per se. We conducted the following experiment to address this question more precisely. HCT116 cells were first arrested in G0/G1 stage of the cell cycle by culturing in serum-depleted media. We then added medium containing serum with or without 10 mM LiCl for 1 or 4 h. LiCl is a well-established agonist of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway as it inhibits GSK3β and stimulates nuclear β-catenin accumulation (13,40,41). We and others have shown that LiCl increased β-catenin levels in HCT116 cells (13,42,43). Therefore, we predicted that if mitogen and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways converged to regulate gene expression, treatment with serum and LiCl would result in increased transcript levels when compared to treatment with serum alone. LiCl increased mitogen-induced expression of MYC, PDE4B, DDR2, CTBP2, EGFR, DNAJB1, WISP1 and PINX1 (Figure 6B). HDAC4, PCDH7 and HABP4 were activated by serum alone, and MMP20, CYP39A1 and YAP1 genes were not induced above levels seen in serum-deprived cells (Figure 6B). Together this analysis indicated that Wnt/β-catenin and mitogen-signaling pathways directly activate a subset of β-catenin target genes in colon cancer cells.

Figure 6.

A subset of target genes associated with β-catenin enriched regions containing TCF4 and AP-1 motifs are activated by mitogen and Wnt signaling. (A) Real-time PCR analysis of cDNAs synthesized from RNAs isolated from asynchronously growing HCT116 cells. Primers were designed to spliced exons of the indicated genes that contained AP-1 and TCF motifs either within or proximal to (<2.5 kb) gene boundaries. Data is presented as expression relative to levels of a primary tubulin transcript and error is SEM. (B) HCT116 cells were deprived serum for 2 days and then treated with medium containing serum in the presence or absence of 10 mM LiCl as indicated. RNAs were isolated, cDNAs reverse transcribed and gene expression analyzed as in (A). Data is presented as induced expression relative to levels obtained from serum-deprived cells.

DISCUSSION

Gene expression is rarely controlled by the association of a single transcription factor with an enhancer element embedded in the proximal promoter. Rather, association of multiple transcription factors within an enhancer allows for precise and specific regulation of gene expression in response to environmental stimuli. Moreover, enhancers can occupy regions over 100 kb from their target gene (44,45). Genome-wide profiling of transcription factor binding sites has emerged as one method to localize composite enhancer elements that integrate upstream signal transduction pathways (17,45). In this report, we used ChIP-Seq to identify β-catenin enriched regions in human colon cancer cells. Through an integrated approach involving bioinformatics, ChIP and expression analyses, we provide evidence that a population of β-catenin target genes is directly regulated by β-catenin, TCF4 and AP-1 transcription factors.

The nature of ChIP-Seq data provides many challenges for analysis (18). Algorithms have been designed to assign a presence or absence prediction for occupancy at any non-repetitive region of the genome. A common approach for many algorithms is to use sliding window methods that identify regions of high read depth (relative to a background distribution) by traversing the genome in windows of a predetermined size. CisGenome, SISSRs and WTD algorithms exemplify this approach (24–26). It follows that although each algorithm finds disparate numbers of enriched regions, increased confidence can be assigned to regions that have been found by all three. This approach resulted in 2168 enriched β-catenin binding regions identified in our β-catenin ChIP-Seq library. In addition to the three WREs that control MYC expression (14,22,29), 30 Wnt/β-catenin target genes listed on the Wnt homepage (http://www.stanford.edu/∼rnusse/pathways/targets.html) were in proximity to β-catenin enriched regions (Supplementary Table S5). Furthermore, when considering of all genomic regions identified and assayed for β-catenin and TCF4 binding in this report, we found that 28 of 32 (87.5%) bound both factors. Together, these findings indicate that the β-catenin ChIP-Seq library identified bona fide and direct Wnt/β-catenin target genes.

We previously localized β-catenin binding sites in colon cancer cells using an unbiased and genome-wide approach termed SACO (14). In that study, we found that 84% of high confidence β-catenin binding regions contained at least one TCF4 consensus core motif (T/A–T/A–C–A–A–A–G). In this report, we performed de novo motif analysis on the 2168 β-catenin enriched regions and found that 47% contained a core TCF4 consensus motif. This discrepancy is likely attributed to methodological and computational differences in the generation and analysis of each data set. For the SACO study, a 5 kb interval surrounding the mean position of the enriched region was used in the analysis. For the ChIP-Seq analysis, we examined a much smaller interval enveloping each β-catenin enriched region (600 bp). Therefore, based on our findings using ChIP-Seq and due to the resolution of this technique, the 47% association rate of TCF4 consensus motifs found in β-catenin enriched regions likely reflects the landscape in vivo. Results gleaned from our current analysis are consistent with TCF4 being a predominant factor that directly recruits β-catenin to enhancers in colon cancer cells, but also suggest that the portion of targets that rely on other factors to recruit β-catenin is substantial.

Two recent studies localized TCF4 binding regions in human colon cancer cells using ChIP-Seq (21,22). We therefore searched for representation of our β-catenin enriched regions in the reported TCF4 libraries. Of the 10 conserved TCF4 binding peak regions identified by Tuupanen et al. (22), three were identified in our β-catenin ChIP-Seq library. This included the peak that identified the WRE located 335 kb upstream from the MYC transcription start site. Upon analysis of the TCF4 ChIP-Seq data sets reported by Blahnik et al. (21) and the ENCODE Project Consortium, we found that 786 (36.3%) of our β-catenin peak regions overlapped a TCF4 peak region. There are several possibilities for why a greater percentage of our β-catenin peak regions are not represented in the aforementioned ChIP-Seq libraries. Methodological variations, algorithms chosen to assign peak regions, and cell-type differences aside, TCF4 is bound to both transcriptionally active and repressed genes. As β-catenin is thought to primarily associate with transcribed genes, a partial overlap of the β-catenin enriched regions identified in our study with the TCF4 enriched regions is expected. Furthermore, as mentioned above, our analysis suggests that the many genes likely recruit β-catenin independently of TCF4. Most of these targets are not represented in the TCF4 ChIP-Seq libraries. Finally, the amount of sequencing required to identify all of the binding sites represented in a ChIP-Seq library is debatable (18). Therefore, we would anticipate that additional sequencing of our library would undoubtedly identify more of the reported TCF4 peak regions. Overall, however, the concordance of TCF4 and β-catenin peaks identified by three separate groups independently validates ChIP-Seq as a methodology to identify direct Wnt/β-catenin target genes.

Upon mapping the β-catenin enriched regions relative to RefSeq gene boundaries, we found that binding sites are dispersed through the 5′, intragenic, and 3′ ends of gene boundaries. This finding is in line with previous genome-wide localization studies of β-catenin and TCF4 binding sites (12,16). We were intrigued by the observation that several targets contained β-catenin enriched regions that localized to both 5′ and 3′ gene boundaries. Based on our previous work with MYC (15), we tested whether a chromatin loop was present at two targets that contained 5′ and 3′ β-catenin enriched regions in the library, CXXC5 and GRHL3. CXXC5 is a zinc finger containing protein that inhibits canonical Wnt signaling in response to bone morphogen protein signaling in neural stem cells (46). GRHL3 encodes a Grainyhead factor that plays a role in epidermal barrier formation in the bladder (47). Substantial levels of β-catenin binding to the 5′ and 3′ regions of CXXC5 and GRHL3 were detected by ChIP analysis (Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure S2). Using the 3C technique, we found that a chromatin loop accompanied β-catenin binding to 5′ and 3′ regions of CXXC5. However, we were unable to detect a chromatin loop at GRHL3. This finding suggests that while looping between separated enhancers may be a prevalent mechanism to coordinate Wnt/β-catenin gene expression, β-catenin binding to 5′ and 3′ sites alone is not sufficient for this interaction. We anticipate that 3C coupled with high throughput sequencing techniques will facilitate identification of target genes that are regulated by distal WREs via chromatin loops (48,49).

Through de novo motif analysis, we found that nearly half of the β-catenin enriched regions that contained a TCF4 consensus motif also contained an AP-1 motif. It is noted here that AP-1 motifs were also over-represented in TCF4 bound regions identified by recent ChIP-Seq and ChIP-chip analysis (16,21). However, our current study is the first to report over-representation of AP-1 motifs in β-catenin bound regions. While β-catenin/TCF4 and AP-1 have been shown by others and our group to regulate target gene expression (36,38,39,50), our findings here suggest that target genes regulated by 417 β-catenin enriched regions may be likewise regulated. Our ChIP analysis indicated that nearly every region assayed (95%) containing a TCF4 and AP-1 motif bound c-Jun, a component of the AP-1 complex. The majority of these loci showed an additive increase in expression upon the addition of both LiCl and serum. This analysis suggests that mitogen and Wnt signaling pathways likely converge through AP-1 and β-catenin/TCF4 to co-regulate target gene expression. However, LiCl treatment failed to enhance mitogen-activated gene expression for several targets. It is possible that pre-treatment of quiescent cells with LiCl prior to serum stimulation would sensitize the system to facilitate detection of pathway cooperation. Alternatively, AP-1 binding may function to regulate gene expression in response to a different stimulus such as cytokine signaling or the apoptotic stress response (35).

The application of sequence-based methods to identify transcription factor binding sites genome-wide is likely to persist as the methodology of choice. Next generation sequencing technology, such as those using the Illumina platform, allows increased resolution and increased output. These attributes have facilitated the replacement of SACO with massively parallel sequencing approaches to map transcription factor binding regions isolated by ChIP. Through our ChIP-Seq screen of β-catenin binding regions in asynchronous HCT116 cells, we uncovered evidence for a functional interplay between β-catenin/TCF4 and AP-1. Because cells that initiate colon carcinogenesis contain pathogenic levels of β-catenin in the nucleus and are bathed in serum mitogens, our findings here suggest that miss-expression of target genes containing AP-1 and TCF4 motifs might represent the pathogenically relevant set.

ACCESSION NUMBER

SRA/SRA012054

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health (grant number R01DK080805 to G.S.Y.); start-up research funds from the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine (to G.S.Y.); National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources (5UL1RR024140 to S.K.M.); National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (5 P30 CA069533-13 to S.K.M.). Funding for open access charge: National Institutes of Health (grant number R01DK080805 to G.S.Y.).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr Laura Carrel and Dr Faoud Ishmael (Penn State University College of Medicine) for critically reading this manuscript and providing helpful comments. We would like to thank Doug Turnbull and the High Throughput Sequencing Facility in the Molecular Biology Institute at the University of Oregon for sequencing the library. We would like to thank Dr Richard Goodman and Dr Gail Mandel (Oregon Health and Science University) for support during the initiation of this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sancho E, Batlle E, Clevers H. Signaling pathways in intestinal development and cancer. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;20:695–723. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.092805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polakis P. Wnt signaling and cancer. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1837–1851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosimann C, Hausmann G, Basler K. Beta-catenin hits chromatin: regulation of Wnt target gene activation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:276–286. doi: 10.1038/nrm2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korinek V, Barker N, Morin PJ, van Wichen D, de Weger R, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Clevers H. Constitutive transcriptional activation by a beta-catenin-Tcf complex in APC-/- colon carcinoma. Science. 1997;275:1784–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groden J, Thliveris A, Samowitz W, Carlson M, Gelbert L, Albertsen H, Joslyn G, Stevens J, Spirio L, Robertson M, et al. Identification and characterization of the familial adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Cell. 1991;66:589–600. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinzler KW, Nilbert MC, Su LK, Vogelstein B, Bryan TM, Levy DB, Smith KJ, Preisinger AC, Hedge P, McKechnie D, et al. Identification of FAP locus genes from chromosome 5q21. Science. 1991;253:661–665. doi: 10.1126/science.1651562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morin PJ, Sparks AB, Korinek V, Barker N, Clevers H, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Activation of beta-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in beta-catenin or APC. Science. 1997;275:1787–1790. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubinfeld B, Souza B, Albert I, Muller O, Chamberlain SH, Masiarz FR, Munemitsu S, Polakis P. Association of the APC gene product with beta-catenin. Science. 1993;262:1731–1734. doi: 10.1126/science.8259518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hart M, Concordet JP, Lassot I, Albert I, del los Santos R, Durand H, Perret C, Rubinfeld B, Margottin F, Benarous R, et al. The F-box protein beta-TrCP associates with phosphorylated beta-catenin and regulates its activity in the cell. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yochum GS, McWeeney S, Rajaraman V, Cleland R, Peters S, Goodman RH. Serial analysis of chromatin occupancy identifies beta-catenin target genes in colorectal carcinoma cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:3324–3329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611576104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yochum GS, Cleland R, McWeeney S, Goodman RH. An antisense transcript induced by Wnt/beta-catenin signaling decreases E2F4. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:871–878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yochum GS, Cleland R, Goodman RH. A genome-wide screen for beta-catenin binding sites identifies a downstream enhancer element that controls c-Myc gene expression. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;28:7368–7379. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00744-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yochum GS, Sherrick CM, Macpartlin M, Goodman RH. A beta-catenin/TCF-coordinated chromatin loop at MYC integrates 5′ and 3′ Wnt responsive enhancers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:145–150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912294107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatzis P, van der Flier LG, van Driel MA, Guryev V, Nielsen F, Denissov S, Nijman IJ, Koster J, Santo EE, Welboren W, et al. Genome-wide pattern of TCF7L2/TCF4 chromatin occupancy in colorectal cancer cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;28:2732–2744. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02175-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farnham PJ. Insights from genomic profiling of transcription factors. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:605–616. doi: 10.1038/nrg2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park PJ. ChIP-seq: advantages and challenges of a maturing technology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:669–680. doi: 10.1038/nrg2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt D, Wilson MD, Spyrou C, Brown GD, Hadfield J, Odom DT. ChIP-seq: using high-throughput sequencing to discover protein-DNA interactions. Methods. 2009;48:240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Z, Schones DE, Zhao K. Characterization of human epigenomes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2009;19:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blahnik KR, Dou L, O'Geen H, McPhillips T, Xu X, Cao AR, Iyengar S, Nicolet CM, Ludascher B, Korf I, et al. Sole-Search: an integrated analysis program for peak detection and functional annotation using ChIP-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuupanen S, Turunen M, Lehtonen R, Hallikas O, Vanharanta S, Kivioja T, Bjorklund M, Wei G, Yan J, Niittymaki I, et al. The common colorectal cancer predisposition SNP rs6983267 at chromosome 8q24 confers potential to enhanced Wnt signaling. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:885–890. doi: 10.1038/ng.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pepke S, Wold B, Mortazavi A. Computation for ChIP-seq and RNA-seq studies. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:S22–S32. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ji H, Jiang H, Ma W, Johnson DS, Myers RM, Wong WH. An integrated software system for analyzing ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq data. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:1293–1300. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jothi R, Cuddapah S, Barski A, Cui K, Zhao K. Genome-wide identification of in vivo protein-DNA binding sites from ChIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:5221–5231. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kharchenko PV, Tolstorukov MY, Park PJ. Design and analysis of ChIP-seq experiments for DNA-binding proteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:1351–1359. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ji H, Vokes SA, Wong WH. A comparative analysis of genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation data for mammalian transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e146. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Maglott DR. NCBI reference sequences (RefSeq): a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D61–D65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He TC, Sparks AB, Rago C, Hermeking H, Zawel L, da Costa LT, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science. 1998;281:1509–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pomerantz MM, Ahmadiyeh N, Jia L, Herman P, Verzi MP, Doddapaneni H, Beckwith CA, Chan JA, Hills A, Davis M, et al. The 8q24 cancer risk variant rs6983267 shows long-range interaction with MYC in colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:882–884. doi: 10.1038/ng.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wright JB, Brown SJ, Cole MD. Upregulation of c-MYC in Cis through a large chromatin loop linked to a cancer risk-associated SNP in colorectal cancer cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;30:1411–1420. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01384-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, Kleckner N. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science. 2002;295:1306–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1067799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chinenov Y, Kerppola TK. Close encounters of many kinds: Fos-Jun interactions that mediate transcription regulatory specificity. Oncogene. 2001;20:2438–2452. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eferl R, Wagner EF. AP-1: a double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:859–868. doi: 10.1038/nrc1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis RJ. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell. 2000;103:239–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gan XQ, Wang JY, Xi Y, Wu ZL, Li YP, Li L. Nuclear Dvl, c-Jun, beta-catenin, and TCF form a complex leading to stabilization of beta-catenin-TCF interaction. J. Cell Biol. 2008;180:1087–1100. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hasselblatt P, Gresh L, Kudo H, Guinea-Viniegra J, Wagner EF. The role of the transcription factor AP-1 in colitis-associated and beta-catenin-dependent intestinal tumorigenesis in mice. Oncogene. 2008;27:6102–6109. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sancho R, Nateri AS, de Vinuesa AG, Aguilera C, Nye E, Spencer-Dene B, Behrens A. JNK signalling modulates intestinal homeostasis and tumourigenesis in mice. EMBO J. 2009;28:1843–1854. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toualbi K, Guller MC, Mauriz JL, Labalette C, Buendia MA, Mauviel A, Bernuau D. Physical and functional cooperation between AP-1 and beta-catenin for the regulation of TCF-dependent genes. Oncogene. 2007;26:3492–3502. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hedgepeth CM, Conrad LJ, Zhang J, Huang HC, Lee VM, Klein PS. Activation of the Wnt signaling pathway: a molecular mechanism for lithium action. Dev. Biol. 1997;185:82–91. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klein PS, Melton DA. A molecular mechanism for the effect of lithium on development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:8455–8459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bordonaro M, Lazarova DL, Sartorelli AC. Pharmacological and genetic modulation of Wnt-targeted Cre-Lox-mediated gene expression in colorectal cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2660–2674. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kimbrel EA, Kung AL. The F-box protein beta-TrCp1/Fbw1a interacts with p300 to enhance beta-catenin transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:13033–13044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901248200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miele A, Dekker J. Long-range chromosomal interactions and gene regulation. Mol. Biosyst. 2008;4:1046–1057. doi: 10.1039/b803580f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heintzman ND, Ren B. Finding distal regulatory elements in the human genome. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2009;19:541–549. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andersson T, Sodersten E, Duckworth JK, Cascante A, Fritz N, Sacchetti P, Cervenka I, Bryja V, Hermanson O. CXXC5 is a novel BMP4-regulated modulator of Wnt signaling in neural stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:3672–3681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808119200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu Z, Mannik J, Soto A, Lin KK, Andersen B. The epidermal differentiation-associated Grainyhead gene Get1/Grhl3 also regulates urothelial differentiation. EMBO J. 2009;28:1890–1903. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fullwood MJ, Ruan Y. ChIP-based methods for the identification of long-range chromatin interactions. J. Cell Biochem. 2009;107:30–39. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lieberman-Aiden E, van Berkum NL, Williams L, Imakaev M, Ragoczy T, Telling A, Amit I, Lajoie BR, Sabo PJ, Dorschner MO, et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science. 2009;326:289–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nateri AS, Spencer-Dene B, Behrens A. Interaction of phosphorylated c-Jun with TCF4 regulates intestinal cancer development. Nature. 2005;437:281–285. doi: 10.1038/nature03914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, Ren J, Li WW, Noble WS. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.