Abstract

The similarity of endospore surface antigens between bacteria of the Bacillus cereus group complicates the development of selective antibody-based anthrax detection systems. The surface of B. anthracis endospores exposes a tetrasaccharide containing the monosaccharide anthrose. Anti-tetrasaccharide monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) and anti-anthrose-rhamnose disaccharide MAbs were produced and tested for their fine specificities in a direct spore enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with inactivated spores of a broad spectrum of B. anthracis strains and related species of the Bacillus genus. Although the two sets of MAbs had different fine specificities, all of them recognized the tested B. anthracis strains and showed only a limited cross-reactivity with two B. cereus strains. The MAbs were further tested for their ability to be implemented in a highly sensitive and specific bead-based Luminex assay. This assay detected spores from different B. anthracis strains and two cross-reactive B. cereus strains, correlating with the results obtained in direct spore ELISA. The Luminex assay (detection limit 103 to 104 spores per ml) was much more sensitive than the corresponding sandwich ELISA. Although not strictly specific for B. anthracis spores, the developed Luminex assay represents a useful first-line screening tool for the detection of B. anthracis spores.

Anthrax is an acute zoonotic disease caused by the spore-forming bacterium Bacillus anthracis. It affects primarily herbivores in many countries of Southern Europe, South America, Asia, and Africa (24). Endospores are the infecting agent and remarkably resistant to extreme heat, dryness, chemicals, or irradiation, thus ensuring long-term survival. The principal virulence factors are a capsule and two exotoxins produced by the growing vegetative form. The major sources of human anthrax infection are direct or indirect contact with infected animals. A reliable identification of B. anthracis is challenging, due to the monomorphic nature of the B. cereus group, which comprises B. cereus, B. anthracis, B. thuringiensis, and B. mycoides (10). The similarity of spore cell surface antigens of the bacteria of this group makes it difficult to create selective, reliable, antibody-based detection systems. DNA-based assays and traditional phenotyping of bacteria are the most accurate detection systems but are also complex, expensive, or slow. The use of B. anthracis spores as a biological weapon has stressed the need to learn more about spore components that can be used for efficient vaccines and rapid detection systems.

The B. anthracis endospore comprises a genome-containing core compartment and three protective layers called the cortex, coat, and exosporium (8). The glycoprotein Bacillus collagen-like protein of anthracis (BclA) is an immunodominant structural component of the exosporium that is extensively glycosylated with two O-linked carbohydrates, a 715-Da tetrasaccharide and a 324-Da disaccharide (6). The tetrasaccharide contains three rhamnose residues and an unusual terminal sugar, 2-O-methyl-4-(3-hydroxy-3-methylbutanamido)-4,6-dideoxy-d-glucopyranose, named anthrose. As anthrose was not found in spores of related strains of bacteria, it has been considered a potential biomarker for the detection of anthrax (6). In this study, the detection of B. anthracis spores was achieved by an assay based on the Luminex technology with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) derived from mice immunized with anthrose-containing synthetic oligosaccharides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of anti-anthrose-rhamnose disaccharide MAbs.

The anthrose-containing synthetic carbohydrates were prepared as described previously (20, 22, 23). Mice carrying human immunoglobulin Cγ1 heavy and Cκ light chain gene segments (16) were immunized with an anthrose-rhamnose disaccharide conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) and formulated in ImmunEasy adjuvant (Qiagen AG, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland). Mice received 3 doses of 40 μg conjugate at 3-week intervals. Three days before cell fusion, a mouse received an intravenous booster injection with 40 μg of conjugate in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). From the sacrificed mouse, the spleen was aseptically removed, and a spleen cell suspension in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) was mixed with PAI mouse myeloma cells as a fusion partner. Spleen and myeloma cells in a ratio of 1:1 were centrifuged; after the supernatant was discarded, the pellet was mixed with 1 ml prewarmed polyethylene glycol 1500 sterile solution. After 60 s, 10 ml of culture medium was added. After 10 min, cells were suspended in IMDM containing hypoxanthine, aminopterin, thymidine, and 20% fetal bovine serum and cultured in 96-well plates. Cells secreting disaccharide-specific IgG were selected using disaccharide-bovine serum albumin (BSA)-coated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates. Six hybridoma cell lines producing disaccharide-specific MAbs were identified, cloned twice by limiting dilution, and named MTD1 to MTD6. The production of anti-tetrasaccharide MAbs is described in reference 21.

Animals were housed in temperature-controlled rooms (22°C ± 3°C). Conventional laboratory feeding and unlimited drinking water were provided to the mice. Approval for animal experimentation was obtained from the responsible authorities, and all experiments were performed in strict accordance with the Rules and Regulations for the Protection of Animal Rights laid down by the Swiss Bundesamt für Veterinärwesen. All animal manipulations were performed under controlled laboratory conditions by specifically qualified personnel in full conformity with Swiss and European regulations.

Spore production and inactivation.

Strains of Bacillus spp. (Table 1) were cultured on tryptone soya agar (Oxoid, Basel, Switzerland) at 37°C for 1 to 2 days. Then, the culture plates were kept in the dark at room temperature for 4 weeks. Colony material was suspended in sterile water, and spores were collected by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. To remove vegetative cells, spores were treated with 65% isopropanol for 1 h at room temperature and subsequently washed with sterile water until the supernatant appeared clear. The washed spores were stored in sterile water at 4°C, and the concentrations were determined by using a Thoma counting chamber. B. anthracis spores were inactivated by suspending 108 spores in 1 ml 10% paraformaldehyde for 1 h, subsequently washed with PBS, and recounted. For Yersinia pestis (ICM 1/41) and Brucella melitensis (NCTC 10094, biotype 1), inactivation was essentially done as described above using 3% formaldehyde. For both inactivation methods, sterility was verified by cultivation. Cultivation and inactivation of risk group 3 bacteria were done in a BSL-3 laboratory.

TABLE 1.

Cross-reactivity of MAbs raised against anthrose-containing synthetic carbohydrates with spores of Bacillus spp.a

| Bacillus sp. | Strain | Code | Plasmid content | OD from spore ELISA of: |

Mean fluorescence intensity (Luminex assay) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTA1 | MTD6 | |||||

| B. anthracis | Ames | Ba0 | pX01+ pX02+ | 0.44 | 1.41 | 19,398 |

| Böhm A58 | Ba1 | pX01− pX02− | 0.33 | 1.54 | 18,719 | |

| Böhm A1 | Ba2 | pX01+ pX02− | 1.01 | 1.66 | 7,229 | |

| Böhm A73202.2000 | Ba3 | pX01− pX02+ | 1.31 | 2.16 | 21,591 | |

| NCTC 8234 Sterne | Ba4 | pX01+ pX02− | 1.76 | 2.36 | 11,120 | |

| NCTC 02620 | Ba7 | pX01+ pX02+ | 0.23 | 0.77 | 24,262 | |

| B. cereus | ATCC 10876 | Bc1 | 1.52 | 2.09 | 23,710 | |

| ATCC 13061 | Bc2 | −0.09 | −0.05 | 141 | ||

| ATCC 14579 | Bc3 | −0.04 | −0.05 | 300 | ||

| ATCC 33019 | Bc4 | 0.24 | 1.15 | 5,964 | ||

| ATCC 11778 | Bc5 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 470 | ||

| B. subtilis | ATCC 6051 | Bs1 | −0.10 | −0.13 | 28 | |

| ATCC 6633 | Bs2 | −0.10 | −0.14 | 26 | ||

| ATCC 11774 | Bs3 | −0.11 | −0.13 | 23 | ||

| Biocontrol AG | Bs4 | ND | ND | 38 | ||

| B. thuringiensis | Kurstaki SP09 | Bt1 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 47 | |

| ATCC 10792 | Bt2 | −0.09 | −0.13 | 33 | ||

| B. atrophaeus | ATCC 9372 | Bat | −0.10 | −0.14 | 27 | |

| B. circulans | ATCC 61 | Bcir | ND | ND | 33 | |

| B. licheniformis | ATCC 12759 | Bl1 | −0.10 | −0.11 | 73 | |

| ATCC 14580 | Bl2 | −0.08 | −0.12 | 27 | ||

| B. megaterium | ATCC 9885 | Bm1 | −0.10 | −0.13 | 23 | |

| ATCC 14581 | Bm2 | −0.10 | −0.13 | 28 | ||

| B. sphaericus | ATCC 4525 | Bsp | −0.08 | −0.13 | 23 | |

| B. pumilus | ATCC 14884 | Bp | −0.10 | −0.13 | 28 | |

B. anthracis strains were chemically inactivated by paraformaldehyde with the exception of the Ames strain (Ba0), which was gamma irradiated. All the other Bacillus species and strains were not inactivated. Spores were used at a concentration of 1 × 106/ml. ELISA results are expressed as test optical densities minus two times the blank (blank, 0.10). Luminex values are shown as the mean fluorescence intensities from two experiments. Bolded values indicate MAb cross-reactive samples. ND, not done.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

For the detection of saccharide-binding antibodies, Immulon 4 microtiter plates (Dynex Technologies Inc., Chantilly, VA) were coated at 4°C overnight with 50 μl of a 10-μg/ml solution of saccharide-BSA conjugate in PBS, pH 7.2. Wells were then blocked with 5% milk powder in PBS for 1 h at room temperature followed by three washings with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20. Plates were then incubated with serial dilutions of MAbs in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 0.5% milk powder for 2 h at room temperature. After being washed, the plates were incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (γ-chain-specific) antibodies (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 1 h at room temperature and then washed. Phosphatase substrate (1 mg/ml p-nitrophenyl phosphate) in buffer (0.14% Na2CO3, 0.3% NaHCO3, 0.02% MgCl2 [pH 9.6]) was added and incubated at room temperature. The optical density (OD) of the reaction product was recorded after an appropriate time at 405 nm using a microplate reader (Sunrise [Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland]).

For the detection of spore-binding antibodies, Maxisorp microtiter plates (Nunc/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wohlen, Switzerland) were coated at 4°C overnight with 100 μl of a spore suspension in 0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6). Wells were then blocked with 3% BSA in PBS and washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20. Wells were incubated with MAbs at a concentration of 1 μg/ml for 1 h. After being washed, the plates were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (γ-chain-specific) antibodies (KPL Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) for 1 h and finally developed with the ABTS [2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid)] substrate.

In antigen capture ELISA, microtiter plates were coated with 100 μl of a 10-μg/ml solution of unlabeled MAbs in PBS. After being blocked with 3% BSA in PBS and washed, wells were incubated with dilutions of spores in PBS. Biotinylated detection MAbs (5 μg/ml) were added and incubated for 1 h. Biotinylation was performed using the EZ-Link sulfo-NHS-biotin labeling kit (Pierce/Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After repeated washing, streptavidin-peroxidase polymer conjugate (1 μg/ml) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added and developed with the ABTS substrate.

Immunofluorescence assays (IFA).

Inactivated spore suspensions were mixed with 2 volumes of a solution containing 4% paraformaldehyde. Droplets of 40 μl of cell suspension were added to each well of a diagnostic microscope slide (Flow Laboratories, Baar, Switzerland) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Spores were blocked with blocking solution containing 100 mg/ml fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin in PBS. Immunostaining was performed by incubating the wells with 25 μl of an appropriate MAb dilution in blocking solution in a humid chamber for 1 h at room temperature. After five washes with blocking solution, 25 μl of 5-μg/ml indocarbocyanine dye-conjugated affinity-pure F(ab′)2 fragment goat anti-mouse IgG heavy-chain antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA), diluted in blocking solution, was added to the wells and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the wells were washed five times, mounted with ProLong gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen AG, Basel, Switzerland), and covered with a coverslip. Antibody binding was assessed by fluorescence microscopy.

Luminex assay.

Antibody MTA1 (21) was coupled to MagPlex microspheres (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer's instructions and diluted in blocking buffer (1% BSA in PBS). In the coupling reaction, 6 μg of antibody was applied to 5 × 105 beads. For the assay, 2,000 beads in a volume of 50 μl were used per microtiter well. Fifty-microliter mixed bacterial samples were added to each bead-containing well and incubated for 2 h on a shaker at 37°C. After being washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, 50 μl of biotinylated detection antibody MTD6 diluted in blocking buffer was added to each well and incubated for 1 h, as described above. After repeated washing, 50 μl of a streptavidin-R phycoerythrin (ProZyme Inc., Hayward, CA) solution was added. Plates were incubated for 30 min as described above and washed. The beads were resuspended in 125 μl of blocking buffer, and the plate was placed on the shaker for 1 min. The assay was analyzed in a BioPlex 200 instrument (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) by counting 100 beads per region. The data are reported as mean fluorescence intensities.

RESULTS

Generation and characterization of anti-anthrose-rhamnose disaccharide MAbs.

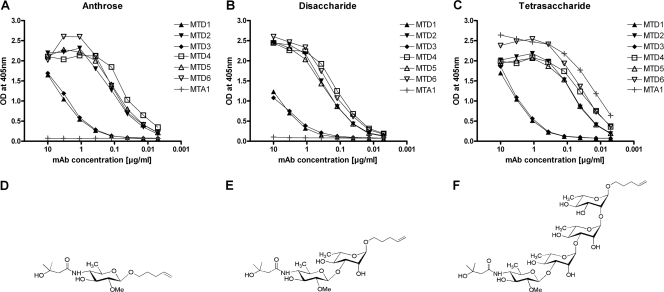

Anthrose-rhamnose disaccharide-specific MAbs were generated basically in the same way as the previously described tetrasaccharide-specific MAbs MTA1 to MTA3 (20, 21). Chemically synthesized disaccharide (Fig. 1E) was covalently attached to the keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) carrier protein by reductive amination. After repeated immunizations of mice with the disaccharide conjugate delivered with a CpG-based adjuvant (ImmunEasy, Qiagen), six anti-disaccharide MAbs (named MTD1 to MTD6) were generated that reacted with a synthetic disaccharide-BSA conjugate in ELISA (Fig. 1B). Analyses of the IgG subclass profiles of the induced disaccharide-specific MAbs showed a predominance of the mouse IgG1(λ) isotype; only MTD6 was of the IgG2b(λ) isotype.

FIG. 1.

Reactivity of anti-disaccharide MAbs with carbohydrate-BSA conjugates bound to ELISA microtiter plates. Shown are response patterns of individual anthrose-rhamnose disaccharide-specific MAbs (MTD1 to MTD6) and of a tetrasaccharide-specific MAb (MTA1) with anthrose-BSA (A), disaccharide-BSA (B), and tetrasaccharide-BSA (C). Structure of the synthetic anthrose (D), anthrose-rhamnose disaccharide (E), and tetrasaccharide (F).

While the binding patterns of disaccharide- and tetrasaccharide-specific MAbs differed, MAbs generated against the same antigen exhibited similar fine specificities. All anti-disaccharide MAbs showed cross-reactivity with the tetrasaccharide (Fig. 1C) and the anthrose monosaccharide (Fig. 1A), demonstrating that rhamnose moieties were not crucial structural elements of their epitopes. MAbs MTD1 and MTD3 showed lower affinities for the synthetic antigens than the other MAbs and were therefore not selected for the further assay development. The failure of MAbs from tetrasaccharide-immunized mice to bind to anthrose (Fig. 1A) and to the disaccharide (Fig. 1B) indicated that rhamnose sugars attached to anthrose were essential for recognition.

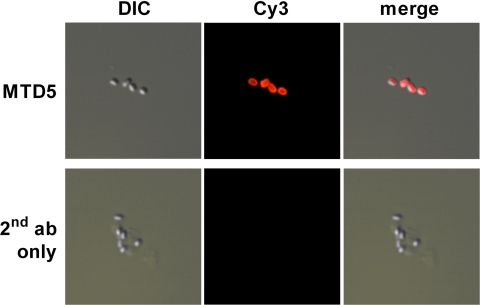

Cross-reactivity of the disaccharide-specific MAbs with endogenous tetrasaccharide expressed by B. anthracis strain Ba4 was established by indirect immunofluorescence assay (Fig. 2) and with immunoblotted B. anthracis endospore lysates (not shown).

FIG. 2.

Cross-reactivity of anti-disaccharide MAbs with B. anthracis strain Ba4 in IFA. Paraformaldehyde-inactivated endospores were stained with the anti-disaccharide MAbs and a secondary antibody conjugated to Cy3. All six MAbs yielded comparable results, and a representative staining is shown for MAb MTD5. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images and an overlay of both signals are also depicted.

Binding of the newly generated anti-disaccharide MAbs as well as of the anti-tetrasaccharide MAbs to spores of a broad spectrum of different Bacillus spp. was analyzed in a direct ELISA using plates coated with a spore suspension. Irrespective of their different fine specificities, both sets of MAbs recognized spores of the tested B. anthracis strains but also showed cross-reactivity with the B. cereus strains Bc1 and Bc4. Spores of none of the other Bacillus spp. were reactive with the MAbs. All tested MAbs showed uniform reactivity patterns, and representative results with the anti-tetrasaccharide MAb MTA1 and the anti-disaccharide MAb MTD6 are shown (Table 1).

Development of a Luminex assay for rapid detection of anthrax spores.

To develop a highly sensitive and specific assay for the detection of anthrax spores from complex samples, the anti-carbohydrate MAbs were used for the development of a Luminex sandwich assay. The Luminex technology is based on fluorescent beads that are color coded. Each bead subset can be coated with a reagent specific for a particular analyte, allowing the capture and detection of this analyte from a complex sample. Within the BioPlex analyzer, lasers excite the internal dyes that identify each bead particle and also any reporter dye captured during the assay. Here, the anti-tetrasaccharide MAb MTA1 was coupled to magnetic beads and used as the capture antibody, and the biotinylated anti-disaccharide MAb MTD6 was used as the detection antibody. The Luminex assay detected the different B. anthracis strains and the B. cereus strains Bc1 and Bc4, correlating with the results obtained in direct spore ELISA (Table 1). For the B. cereus strains Bc2, Bc3, and Bc5, fluorescence background signals were weak at very high spore concentrations (≥1 × 106 spores/ml) and were absent within one lower log stage of spores (not shown). Other antibody combinations were not adapted for the Luminex assay, since all MAbs showed similar reactivity patterns in direct spore ELISA.

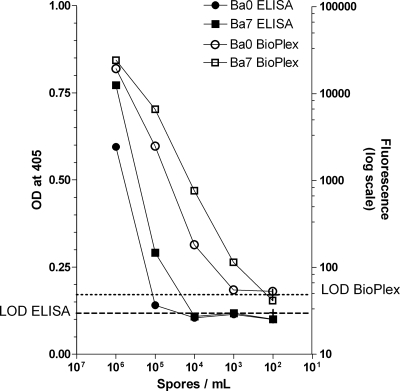

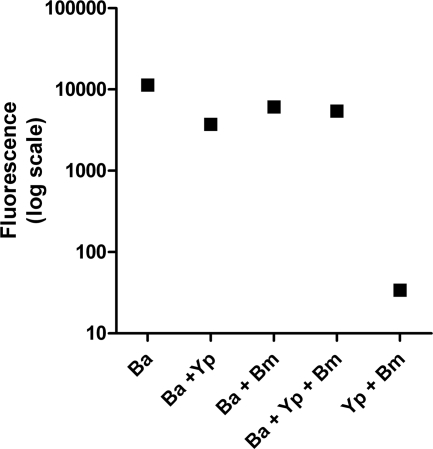

The sensitivity of the developed bead-based assay was determined by analyzing a serial dilution of the B. anthracis spores. The limit of detection (LOD) was defined by the spore concentration yielding a signal two times as high as the mean fluorescence intensity of the blank (dashed lines in Fig. 3). Depending on the anthrax strain tested, the assay was able to detect 50 to 500 spores in a sample volume of 50 μl. The sensitivity of the Luminex assay was 10- to 100-fold higher than that of a corresponding antigen capture ELISA (Fig. 3), where at least 5 × 103 spores per 50 μl sample volume were required for an accurate detection. The developed Luminex assay for anthrax spore detection was further evaluated in mixed samples combining three inactivated bacterial species. In these complex samples, the anthrax spores were accurately detected, and no cross-reactivities were observed (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Sensitivity of the Luminex assay compared to that of the corresponding antigen capture ELISA. The filled symbols represent ELISA (left y axis) values, and the open symbols represent the BioPlex (right y axis) values. Dashed lines indicate the limit of detection (LOD). BioPlex LOD was defined by two times the mean fluorescence intensity of the blank (mean blank, 26.75; standard deviation [SD], 0.35). Capture ELISA LOD was defined by the mean blank plus two times the SD and used as the threshold for positive results (mean blank, 0.105; SD, 0.007).

FIG. 4.

Performance of a bead-based Luminex assay for the detection of anthrax spores in complex biological samples. Test samples contained B. anthracis Ba0 (Ba), Y. pestis (Yp), or B. melitensis (Bm) bacteria either alone or in combination. Shown are reporter dye fluorescence intensities measured for MTA1 beads. Bacteria were used at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml.

DISCUSSION

Antibodies can provide the basis for specific and sensitive immunoassays for the diagnosis of infectious diseases (2, 3). The development of immunochemical assays specific for B. anthracis endospores has been hampered by the presence of cross-reactive antigens in closely related spores, in particular in B. cereus. Since the anthrose monosaccharide was not found in spores of the B. cereus T strain and a B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki strain (6), it has been considered a potential target antigen for the detection of B. anthracis spores. After the first chemical synthesis of the anthrose-containing tetrasaccharide (23), several synthetic approaches of the tetrasaccharide or corresponding sequences have been reported (1, 4, 9, 15, 17-19). Covalent attachment of the synthetic tetrasaccharide to a carrier protein produced a carbohydrate-protein conjugate that was immunogenic in mice (21). Cross-reactivity of anti-tetrasaccharide MAbs with native B. anthracis endospores in immunofluorescence analysis confirmed the structural analysis of the tetrasaccharide and its expression on the endospore surface (21). Screening of anti-tetrasaccharide MAbs for cross-reactivity with immunoblotted spore lysates of panels of B. anthracis and B. cereus strains demonstrated the presence of anthrose in all B. anthracis strains tested and in some B. cereus strains (20). A recent genomic analysis demonstrated the presence of the anthrose biosynthetic operon in B. cereus strains (7). Additionally, structures similar to anthrose were found in the capsular polysaccharide of Shewanella spp. MR-4 and on flagella of Pseudomonas syringae (13).

Anti-tetrasaccharide MAbs (21) and anti-anthrose-rhamnose disaccharide MAbs described in this study were tested for their specificities in a direct ELISA using plates coated with spores of B. anthracis strains and related species of the Bacillus genus. Both types of MAbs recognized the tested B. anthracis strains but also showed cross-reactivity with two B. cereus strains, confirming the previously observed cross-reactivity with immunoblotted spore lysates of the same B. cereus strains (20). Kuehn and colleagues (14) generated one polyclonal antibody against the anthrose-containing tetrasaccharide that showed no cross-reactivities with other Bacillus strains in capture ELISA. Interestingly, the synthetic anthrose monosaccharide included the already-essential structural motifs required for binding of the anti-disaccharide MAbs. In contrast, the anti-tetrasaccharide MAbs recognized more complex epitopes that probably comprised all four sugar residues of the tetrasaccharide. Therefore, the target epitope might be better accessible for the anti-disaccharide MAbs. Biosafety containment requires an inactivation of probes containing B. anthracis spores. Inactivation by paraformaldehyde treatment did not destruct the epitopes recognized by the carbohydrate-specific antibodies, as also observed previously (14). Moreover, the sugar was also conserved on irradiated spores. Antigen conservation is not self-evident, since it was demonstrated that inactivation methods can affect the sensitivity of nucleic acid- and antibody-based assays for the detection of B. anthracis endospores (5).

Even though the MAbs generated against anthrose-containing structures were not strictly specific for B. anthracis, they still may represent a basis for the development of useful first-line screening platforms. Therefore, MAbs MTA1 and MTD6 were further tested as components of a highly sensitive immunodetection assay based on the Luminex technology platform. Use of the assay to detect individual spores of a broad range of Bacillus spp. strains correlated with the results obtained in direct spore ELISA, demonstrating the suitability of the bead-based platform to capture and detect spore particles. The sensitivity of spore detection by the Luminex assay was substantially increased compared to the corresponding capture ELISA, with the detection of 103 to 104 spores per ml. Currently available immunological detection systems offer higher detection limits (11, 12, 14). The platform can be also used in multiplex assays, and we are currently evaluating the simultaneous detection of different biothreat bacteria in mixed samples. In addition, we are testing the generated anti-carbohydrate monoclonal antibodies with field samples from different countries where anthrax is endemic to incorporate a broader genetic diversity of strains within the B. cereus group.

Acknowledgments

M.T., P.H.S., and G.P. are coinventors of European patent no. 06116359.8—detection of Bacillus anthracis and vaccine against B. anthracis infections.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamo, R., R. Saksena, and P. Kováč. 2005. Synthesis of the β anomer of the spacer-equipped tetrasaccharide side chain of the major glycoprotein of the Bacillus anthracis exosporium. Carbohydr. Res. 340:2579-2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreotti, P. E., G. V. Ludwig, A. H. Peruski, J. J. Tuite, S. S. Morse, and L. F. Peruski, Jr. 2003. Immunoassay of infectious agents. Biotechniques 4:850-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry, J. D. 2005. Rational monoclonal antibody development to emerging pathogens, biothreat agents and agents of foreign animal disease: the antigen scale. Vet. J. 170:193-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crich, D., and O. Vinogradova. 2007. Synthesis of the antigenic tetrasaccharide side chain from the major glycoprotein of Bacillus anthracis exosporium. J. Org. Chem. 72:6513-6520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dang, J. L., K. Heroux, J. Kearney, A. Arasteh, M. Gostomski, and P. A. Emanuel. 2001. Bacillus spore inactivation methods affect detection assays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3665-3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daubenspeck, J. M., H. Zeng, P. Chen, S. Dong, C. T. Steichen, N. R. Krishna, D. G. Pritchard, and C. L. Turnbough, Jr. 2004. Novel oligosaccharide side chains of the collagen-like region of BclA, the major glycoprotein of the Bacillus anthracis exosporium. J. Biol. Chem. 279:30945-30953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong, S., S. A. McPherson, L. Tan, O. N. Chesnokova, C. L. Turnbough, Jr., and D. G. Pritchard. 2008. Anthrose biosynthetic operon of Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 190:2350-2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerhardt, P. 1967. Cytology of Bacillus anthracis. Fed. Proc. 5:1504-1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo, H., and G. A. O'Doherty. 2007. De novo asymmetric synthesis of the anthrax tetrasaccharide by a palladium-catalyzed glycosylation reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 46:5206-5208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helgason, E., O. A. Okstad, D. A. Caugant, H. A. Johansen, A. Fouet, M. Mock, I. Hegna, and A. B. Kolstø. 2000. Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis—one species on the basis of genetic evidence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2627-2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoile, R., M. Yuen, G. James, and G. L. Gilbert. 2007. Evaluation of the rapid analyte measurement platform (RAMP) for the detection of Bacillus anthracis at a crime scene. Forensic Sci. Int. 171:1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King, D., V. Luna, A. Cannons, J. Cattani, and P. Amuso. 2003. Performance assessment of three commercial assays for direct detection of Bacillus anthracis spores. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3454-3455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubler-Kielb, J., E. Vinogradov, H. Hu, S. H. Leppla, J. B. Robbins, and R. Schneerson. 2008. Saccharides cross-reactive with Bacillus anthracis spore glycoprotein as an anthrax vaccine component. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:8709-8712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuehn, A., P. Kovác, R. Saksena, N. Bannert, S. R. Klee, H. Ranisch, and R. Grunow. 2009. Development of antibodies against anthrose tetrasaccharide for specific detection of Bacillus anthracis spores. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:1728-1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta, A. S., E. Saile, W. Zhong, T. Buskas, R. Carlson, E. Kannenberg, Y. Reed, C. P. Quinn, and G. J. Boons. 2006. Synthesis and antigenic analysis of the BclA glycoprotein oligosaccharide from the Bacillus anthracis exosporium. Chemistry 12:9136-9149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pluschke, G., A. Joss, J. Marfurt, C. Daubenberger, O. Kashala, M. Zwickl, A. Stief, G. Sansig, B. Schlapfer, S. Linkert, H. van der Putten, N. Hardman, and M. Schroder. 1998. Generation of chimeric monoclonal antibodies from mice that carry human immunoglobulin Cgamma1 heavy of Ckappa light chain gene segments. J. Immunol. Methods 215:27-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saksena, R., R. Adamo, and P. Kováč. 2005. Studies toward a conjugate vaccine for anthrax. Synthesis and characterization of anthrose [4,6-dideoxy-4-(3-hydroxy-3-methylbutanamido)-2-O-methyl-d-glucopyranose] and its methyl glycosides. Carbohydr. Res. 340:1591-1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saksena, R., R. Adamo, and P. Kováč. 2006. Synthesis of the tetrasaccharide side chain of the major glycoprotein of the Bacillus anthracis exosporium. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 16:615-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saksena, R., R. Adamo, and P. Kováč. 2007. Immunogens related to the synthetic tetrasaccharide side chain of Bacillus anthracis exosporium. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 15:4283-4310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamborrini, M., M. A. Oberli, D. B. Werz, N. Schürch, J. Frey, P. H. Seeberger, and G. Pluschke. 2009. Immuno-detection of anthrose containing tetrasaccharide in the exosporium of Bacillus anthracis and Bacillus cereus strains. J. Appl. Microbiol. 106:1618-1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamborrini, M., D. B. Werz, J. Frey, G. Pluschke, and P. H. Seeberger. 2006. Anti-carbohydrate antibodies for the detection of anthrax spores. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 45:6581-6582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Werz, D. B., A. Adibekian, and P. H. Seeberger. 2007. Synthesis of a spore surface pentasaccharide of Bacillus anthracis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 12:1976-1982. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Werz, D. B., and P. H. Seeberger. 2005. Total synthesis of antigen Bacillus anthracis tetrasaccharide—creation of an anthrax vaccine candidate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 44:6315-6318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. 1998. Guidelines for the surveillance and control of anthrax in humans and animals, 3rd ed. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.