Abstract

Salmonella enterica species are exposed to envelope stresses due to their environmental and infectious lifestyles. Such stresses include amphipathic cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs), and resistance to these peptides is an important property for microbial virulence for animals. Bacterial mechanisms used to sense and respond to CAMP-induced envelope stress include the RcsFCDB phosphorelay, which contributes to survival from polymyxin B exposure. The Rcs phosphorelay includes two inner membrane (IM) proteins, RcsC and RcsD; the response regulator RcsB; the accessory coregulator RcsA; and an outer membrane bound lipoprotein, RcsF. Transcriptional activation of the Rcs regulon occurred within minutes of exposure to CAMP and during the first detectable signs of CAMP-induced membrane disorder. Rcs transcriptional activation by CAMPs required RcsF and preservation of its two internal disulfide linkages. The rerouting of RcsF to the inner membrane or its synthesis as an unanchored periplasmic protein resulted in constitutive activation of the Rcs regulon and RcsCD-dependent phosphorylation. These findings suggest that RcsFCDB activation in response to CAMP-induced membrane disorder is a result of a change in structure or availability of RcsF to the IM signaling constituents of the Rcs phosphorelay.

Salmonellae are Gram-negative bacterial pathogens that infect a large array of hosts, including poultry, swine, cattle, and humans. Infection with salmonellae occurs by the fecal-oral route, leading to a spectrum of diseases, including gastroenteritis and typhoidal fever. Salmonellae can invade the intestinal mucosa, multiplying and replicating within a phagocytic vacuole (24). Therefore, Salmonella species transition through a variety of environments and must respond to these environments with appropriate regulation of gene expression to promote survival and growth within host tissues.

Salmonellae are exposed to a range of membrane stresses due to both their environmental and their infectious lifestyle. Encountered stresses include desiccation, changing ionic strength, osmotic stress, temperature fluctuations, and exposure to membrane-active host proteins, including complement and cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs) (19, 24). In response to CAMPs, salmonellae remodel their outer membrane (OM) by synthesis and covalent modifications to lipid A, which can increase membrane acylation and reduce negative charge and immune detection, thus increasing resistance to CAMPs (19). In addition to producing membrane changes, they can modulate envelope protein content on exposure to antimicrobial peptides. Selective ion/ABC transporters that use active efflux to restore envelope integrity and membrane bound proteases that selectively cleave at basic amino acid residues of the CAMP molecule are synthesized, which also promotes CAMP resistance (3, 5, 21).

Gram-negative bacteria sense and respond to CAMP-induced envelope stress by use of two-component systems which consist of a sensor histidine kinase (HK) and a phosphorylated cytoplasmic response regulator (RR) (45). The best characterized of these is PhoP/PhoQ, which is directly activated by CAMP binding to the periplasmic domain of the sensor kinase PhoQ. The RcsFCDB signaling system is a more complex histidine kinase sensor system that is activated by the CAMP polymyxin B (PMB), though the mechanism and specificity of its activation by CAMP are unknown (4, 15, 18). In Escherichia coli, RcsFCDB contributes to resistance to select β-lactams; lysozyme exposure and a variety of other conditions result in its activation. For example, mutants with diverse weakened or altered envelope structures demonstrate Rcs regulon activation (8, 9, 17, 27, 36, 39, 42). The different disruptions include altered lipopolysaccharide (LPS) structure in rfa-1 mutants, dysregulation of membrane-derived oligosaccharides in mdoH mutants, and defects in acidic phospholipid synthesis in pgsA mutants (9, 17, 36, 42). While in general these conditions cause a weakened or altered envelope structure, Rcs activation by lysozyme and β-lactams suggests that disruption of the peptidoglycan layer of the envelope can also activate the Rcs regulon (8, 27, 39).

The RcsFCDB phosphorelay was originally identified as a regulator of capsule synthesis (Rcs), as it promotes colanic acid production; however, transcriptional studies have shown that the Rcs regulon encompasses a much broader transcriptome, including regulation of genes involved in biofilm formation and flagellar genes as well as many other putative periplasmic and membrane proteins (15, 18, 20, 23, 29, 44). The Rcs regulon has also been implicated in positive and negative control of specific virulence factors in Enterobacteriaceae, including SPI-2 genes of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Vi antigen of S. enterica serovar Typhi, and the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) of enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC). The complexity of genes regulated by the Rcs regulon suggests an important role for both the response to membrane stress and microbial pathogenesis (2, 15, 18, 47, 50).

The Rcs phosphorelay is more complex than the typical two-component system embodied by the canonical sensor kinase phosphorylation of a cognate response regulator. RcsFCDB consists of the periplasmic lipoprotein RcsF; two inner membrane (IM) bound proteins, the HK RcsC and the histidine phosphotransfer (HPT) protein RcsD; the cytoplasmic response regulator RcsB; and an auxiliary transcriptional activator, RcsA (29). The mechanism of activation involves autophosphorylation of the HK RcsC, phosphotransfer to the HPT protein RcsD, and subsequent phosphotransfer to the RR RcsB, leading to regulation of gene expression either as an RcsB homodimer or as a heterodimer with RcsA (10, 29). Signaling in the RcsFCDB phosphorelay follows a histidine-to-aspartate phosphorylation cascade from RcsC to RcsD to RcsB.

It is unclear how RcsF, an outer membrane lipoprotein, contributes to this signaling cascade. Genetic studies indicate that it is epistatic to RcsCDB under certain conditions. RcsF is required for induction of the regulon after exposure to either lysozyme or β-lactam antibiotics. This result has led some investigators to postulate that it is involved in sensing peptidoglycan-mediated stress or disorder (8, 9, 27, 30). However, RcsF is not required for regulon activation from overexpression of the inner membrane protein DjlA (9, 27, 30). Therefore, different envelope stresses could be sensed through different and complex mechanisms, given the complexity of the regulation machinery.

In this work, we examined the activation of the Rcs regulon by CAMPs, which, in contrast to β-lactam antibiotics, are a physiologic signal that will first permeabilize the outer membrane. Rcs activation by CAMPs is rapid, requires RcsF, and is highly specific in that it is not induced by most other membrane-damaging agents. We further show that subcellular localization, lipidation, and disulfide linkages of RcsF influence its activation, leading to a model in which specific membrane disruption by CAMPs is directly sensed through increased RcsF accessibility to the inner membrane or periplasm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The S. Typhimurium strains and plasmids used are listed in Table 1. Strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or LB plates with the required antibiotics as needed. Assays measuring transcriptional responses and ethidium bromide (EtBr) influx on exposure to CAMPs were conducted in Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB), which is an established medium for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and reproduced in LB broth with similar trends. Transcriptional activity on exposure to LL-37 was conducted in N-minimal medium, pH 7.4, with 1 mM MgCl2, as LL-37 has been shown to have a high degree of salt sensitivity, which negatively affects its antimicrobial activity (4, 7, 37). The antibiotic concentrations used were as follows: kanamycin, 45 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 20 μg/ml; ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; and tetracycline, 10 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype/description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| CS093 | 14028s | ATCC |

| CH82 | 14028s rcsF::kan | This work |

| CH88 | 14028s wza::pFUSE | 3 |

| CH92 | 14028s wza::lacZ rcsF::kan | This work |

| MB126 | 14028s rcsC::pFUSE | This work |

| CH175 | 14028s rcsD::kan | This work |

| CH107 | 14028s rcsF::kan wza::lacZ, pCH1 | This work |

| CH109 | 14028s rcsF::kan wza::lacZ, pCH2 | This work |

| CH132 | 14048s rcsF::kan wza::lacZ, pCH3 | This work |

| CH188 | 14048s rcsC::kan wza::lacZ, pCH2 | This work |

| CH189 | 14048s rcsD::kan wza::lacZ, pCH2 | This work |

| CH177 | 14028s rcsF::kan wza::lacZ, pCH4 | This work |

| CH178 | 14028s rcsF::kan wza::lacZ, pCH5 | This work |

| CH179 | 14028s rcsF::kan wza::lacZ, pCH6 | This work |

| CH180 | 14028s rcsF::kan wza::lacZ, pCH7 | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCH1 | RcsF-HA in pBAD24, Ampr | This work |

| pCH2 | RcsF S17D-HA in pBAD24, Ampr | This work |

| pCH3 | PagC(1-24)-RcsF(17-134)-6His in pBAD24, Ampr | This work |

| pCH4 | RcsF C74S-6His in pBAD24, Ampr | This work |

| pCH5 | RcsF C109S-6His in pBAD24, Ampr | This work |

| pCH6 | RcsF C118S-6His in pBAD24, Ampr | This work |

| pCH7 | RcsF C124S-6His in pBAD24, Ampr | This work |

Construction of RcsF mutants and epitope-tagged constructs.

P22 HT int lysates were harvested and used for transductions as previously described (31). All candidate plasmids and strains were verified by sequencing and P22 phage transduced to a fresh background where necessary. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed according to manufacturer instructions by use of a Stratagene quick-change site-directed mutagenesis kit (La Jolla, CA). Primers CH63 and CH64 (Table 2) were used to generate pCH2, primers CH132 and CH133 for pCH4, primers CH134 and CH135 for pCH5, primers CH136 and CH137 for pCH6, and primers CH139 and CH139 for pCH7, and combinations thereof were used to make the double mutants. The wza::lacZ reporter strain (CH88) was constructed with the lacZYA suicide vector pFUSE introduced into the wza gene, using primers MB30 and MB31 by methods previously reported (6). The rcsF, rcsD, and rcsC deletion strains (CH92, CH175, and MB126, respectively) were constructed using the lambda red system previously described (13). Primers used for rcsF were MB281 and MB280, those for rcsD were CH103 and CH104, and those for rcsC were MB47 and MB48. An unanchored PagC-RcsF-HA (hemagglutinin) clone was constructed by replacing the first 16 amino acids of RcsF with the published N-terminal sequence of the S. Typhimurium PagC protein to generate PagC(1-24)-RcsF(17-134)-HA. The construct was cloned into pBAD24 to make pCH3 (33).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|

| MB30 | CGGATATCATTTATCACTTTGGCAGAGTC |

| MB31 | GCTCTAGACTTAACGCCTGTACGCTAAAA |

| MB47 | TACAGGCCGGACAGGCGACGCCGCCATCCGGCATTTTTTACATATGAATATCTTCTTTAG |

| MB48 | ACACTCTATTTACATCCTGAGGCGGAGCTTCGCCCCTTTGTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTT |

| MB280 | TCATTTATGCAAGCTCCTGA |

| MB281 | CGGCGAATTTTTCTTTATAG |

| CH63 | CTGCTTAGCATGTCACAACCGCCCAGC |

| CH64 | GCTGGGCGGTTGTGACATGCTAAGCAG |

| CH103 | GACGGGAAGTGGAAGTCGCAACGAAAATGTCCAGCATTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| CH104 | GGCCCATCCTCTAATTCGTACCGTTTGTGGGGAAAGTCCGCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

| CH132 | GTCGCCTGGCTGGATTCGCCGCTAAC |

| CH133 | GTTAGCGGCGAATCCAGCCAGGCGAC |

| CH134 | CGCTGGTAATTTCACTGCTGTGCAGCAGGA |

| CH135 | TCCTGCTGCACAGCAGTGAAATTACCAGCG |

| CH136 | CGCCTGACGATAGCTGCCTGGCGTG |

| CH137 | CACGCCAGGCAGCTATCGTCAGGCG |

| CH138 | GCGGACCCGATACTAACCGCCTGACG |

| CH139 | CGTCAGGCGGTTAGTATCGGGTCCGC |

β-Galactosidase reporter assays.

β-Galactosidase reporter assays were adapted from previously published Miller assays using the SDS/CHCl3 permeabilization process, and results are reported in units established by Miller (32). β-Galactosidase activities caused by subinhibitory to sublethal concentrations of envelope-disrupting substrates were analyzed at 60 min postexposure as previously described (3). Activities of triplicate samples were averaged (±standard deviation) among the three experiments.

Determination of MICs for all envelope-disrupting substrates was performed as described previously (1).

Quantitative real-time PCR assays.

Quantitative real-time PCR assays were performed on an MX4000 Multiplex QPCR system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), with samples loaded in triplicate using approximately 30 ng of total RNA. After each assay, a dissociation curve was run to confirm specificity of all PCR amplicons. Resulting threshold cycle (CT) values were converted to nanograms, normalized to total RNA, and expressed as the averages of triplicate samples ± 1 standard deviation. Samples to measure transcriptional activation by exposure to subinhibitory concentrations of PMB were prepared and analyzed as previously mentioned (3). Briefly, each strain was grown in LB broth to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.2 and split into two flasks, with subinhibitory concentrations of PMB (1 μg/ml) added to one of the two flasks. Samples were collected over time, frozen at −80°C immediately after collection, and subsequently processed for real-time PCR (RT-PCR). CS093 was compared against the otherwise isogenic rcsF deletion strain (CH82). As expected, no transcriptional response to CAMP was observed for CH82. Fold activation of CS093 reflects activation above basal transcription observed without exposure to CAMP.

Permeability assay.

Measurement of ethidium bromide influx as a measure of OM permeability was performed as described previously (3). The strains and experimental conditions were identical to those used for RT-PCR.

Subcellular fractionation.

Subcellular fractionation of cell envelope fractions was performed as previously described (9). Periplasmic preparations were carried out using the periplasting protocol supplied by an Epicentre periplasting kit (Madison, WI). Where necessary, trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation of proteins was performed as described previously (16).

Western blot analysis.

Protein concentrations were determined using the standard Bradford assay (7a). Protein (5 μg per sample) was resolved on a Bio-Rad 12% Tris-HCl ready gel, and blots were detected with an ECL Western blotting detection system from Amersham Biosciences. Sources for primary antibodies are as follows: HA antibodies were from Covance, tetra-His antibodies were from Qiagen, and both the OmpA and SecA polyclonal antibodies were obtained from D. B. Oliver at Wesleyan University.

Phosphotransfer assays.

Samples for in vitro phosphorylation were prepared according to protocols previously described (22, 40). Briefly, total membrane (TM) was prepared from CH109 induced with 0.05% arabinose for 2 h to express IM-routed RcsF and processed as previously described (40). TM was added to 2 μCi [γ-33P]ATP and incubated in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 200 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol). Reaction mixtures were separated by a bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel and exposed to a phosphorimager, and mean signal intensities between lanes were analyzed by ImageJ software.

Analysis of LPS fatty acids.

LPS isolation was performed as described previously (12). LPS fatty acids were derivatized to fatty acid methyl esters and extracted into hexane as previously described (26) prior to analysis by gas chromatography using an RTX-5MS column on a Shimadzu GCMS-QP2010 instrument in electron ionization (EI) source mode. The amounts of C12:0, C14:0, 2-hydroxymyristate (2-OH C14:0), and C16:0 were determined. C15:0 was used as an internal standard.

RESULTS

Induction of the Rcs regulon by CAMPs requires RcsF.

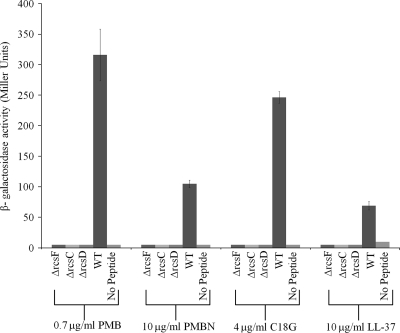

RcsFCDB-regulated genes were previously shown to be transcriptionally activated by polymyxin B and polymyxin E (3, 15, 18, 39). S. Typhimurium strains carrying a wza::lacZ transcriptional reporter and with and without an rcsF deletion were exposed to subinhibitory concentrations of PMB, polymyxin B nonapeptide (PMBN), C18G, and LL-37 at concentrations below the experimentally determined MICs (Table 3), and β-galactosidase activity was measured. Exposure of wild-type (WT) bacteria to 0.5 μg/ml PMB, 2.5 μg/ml PMBN, 2 μg/ml C18G, and 10 μg/ml LL-37 produced 11-fold, 7-fold, 30-fold, and 7-fold activation, respectively. Activation was dose dependent, with an increase in CAMP concentration nearing the MIC corresponding to an increase in reporter activity. In contrast, no activation was observed for the rcsF, rcsD, and rcsC mutants (Fig. 1). These results show that the Rcs regulon is activated by subinhibitory concentrations of CAMP in a dose-dependent manner that requires all three periplasmic constituents, RcsF, RcsC, and RcsD, for activation.

TABLE 3.

The wza gene is induced by exposure to CAMPs

| CAMP tested | MIC (μg/ml) | Concn testeda (μg/ml) | wza::lacZ activationb (Miller units) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymyxin B | ≥1.0 | 0.7 | 316 |

| 0.5 | 54 | ||

| 0 | 5 | ||

| PMBN | ≥20 | 10 | 105 |

| 2.5 | 35 | ||

| 0 | 5 | ||

| C18G | ≥5.0 | 4 | 247 |

| 2 | 148 | ||

| 0 | 5 | ||

| LL-37c | ≥15 | 15 | 341 |

| 10 | 69 | ||

| 0 | 10 |

Concentrations used are below or at the experimentally determined MIC.

The wza::lacZ response increases with concentrations exceeding the MIC but generally plateaus shortly thereafter, likely due to cell death (not shown).

LL-37 activation was measured in N-minimal medium, due to salt sensitivity.

FIG. 1.

RcsFCD is required for wza induction by CAMPs. Individual Rcs deletion mutants carrying the wza::lacZ transcriptional reporter were constructed as described in Materials and Methods (ΔrcsF mutant, CH92; ΔrcsC mutant, MB126; ΔrcsD mutant, CH175; WT, CH88). Each mutant was tested for Rcs activation by CAMP exposure, and results reveal that RcsF, RcsC, and RcsD are all required for activation by CAMP exposure.

The Rcs transcriptional response occurs within minutes of PMB exposure.

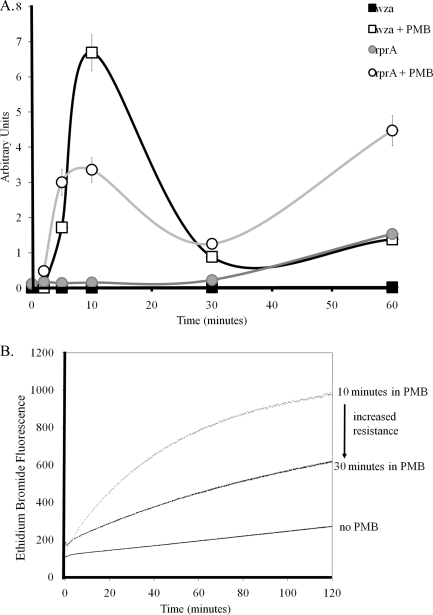

Within 10 min of exposure to subinhibitory concentrations of polymyxin, changes in permeability of the OM can be detected (49). Therefore, polymyxin-induced changes in the OM are rapid, and if Rcs activation is a direct result of these initial changes to the OM, Rcs activation should occur shortly after exposure. To determine the kinetics of the Rcs response to PMB, we measured transcriptional activation after exposure to subinhibitory concentrations of PMB as previously described (3). Real-time PCR was used to measure transcriptional activation for rcsF and two Rcs-regulated genes: wza, which is regulated by the RcsBA heterodimer, and rprA, which is regulated by the RcsBB homodimer. Rcs activation did not affect transcription of rcsF (data not shown); however, activation of the wza and rprA genes was observed 5 min after exposure to PMB, with peak activation for both genes within 10 min after exposure (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, activation of wza decreased from 672-fold at 10 min to 50-fold at 30 min and maintained a reduced level through 60 min. A similar trend was observed for rprA, with 22-fold activation at 10 min decreasing to 5-fold at 30 min, again with this reduced level of activation maintained through 60 min. The rapid Rcs response to PMB raised the possibility that the mechanism of activation of the periplasmic Rcs signaling machinery involved a change in the membrane environment to facilitate a threshold for activation.

FIG. 2.

Rcs activation is rapid and reduced in parallel with membrane repair. (A) mRNA levels of rprA and wza were compared with or without exposure to a subinhibitory concentration of PMB (1 μg/ml) at 0, 2, 5, 10, 30, and 60 min postexposure. Each data point represents the average ratio of the respective mRNA/total RNA, reported in arbitrary units. Both wza and rprA mRNA levels increased within 5 min after exposure to PMB, with peak activation at 10 min. CH82, carrying the rcsF deletion, did not show activation for rprA or wza (not shown). (B) Outer membrane repair is observed within 30 min of exposure to low levels of PMB. A change in outer membrane permeability was measured by EtBr uptake after exposure to 1 μg/ml of PMB.

The rapid activation and subsequent reduction in Rcs transcriptional activation after 30 min could be explained by membrane repair or reconstitution of the membrane environment occurring within 30 min, resulting in a reduced degree of Rcs activation. To investigate this possibility, the change in OM disruption after exposure to PMB was measured. We measured OM permeability by recording ethidium bromide (EtBr) uptake after exposure to PMB for either 10 or 30 min, as previously described (3, 34). After a 10-min exposure to PMB, there is a 3-fold increase in EtBr uptake (Fig. 2B). In contrast, cells exposed to PMB for 30 min had a reduced EtBr uptake, to 1.5-fold that of the no-CAMP control (Fig. 2B). To assess the effect of PMB exposure on LPS remodeling, we isolated and derivatized LPS from cells exposed to PMB for 30 min and analyzed by gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. The average molar ratios relative to that of C12:0, which remains constant, were calculated and showed that the relative contents of 2-OH C14:0 and C16:0 increased upon PMB exposure, 2.3-fold and 1.7-fold, respectively. 2-OH C14:0 molar ratios increased from 0.0083 for PMB-unexposed cells to 0.0190 upon exposure and C16:0 molar ratios from 0.1433 to 0.7032. These results suggest that significant OM repair and LPS modifications occurred within 30 min of PMB exposure, which could reduce the envelope stress response recognized by the RcsFCDB phosphorelay. Our analysis of the Rcs response upon PMB exposure reveals a rapid initial Rcs response to PMB exposure that is reduced over time in parallel with OM repair. These results suggest that outer membrane disruption by CAMPs may be a signal for Rcs regulon activation.

RcsFCDB activation is a specific response to CAMP-induced outer membrane stress.

CAMPs are small polycationic peptides that upon contact with the bacterial surface induce charge disruption, membrane disorganization, and permeabilization (49). To test the specificity of RcsF-dependent activation by CAMP-related stresses, we investigated Rcs activation by other envelope-permeabilizing agents. As seen in Table 4, neither β-galactosidase activity nor RT-PCR activation was observed after exposure to subinhibitory to sublethal concentrations of EDTA, SDS, and Triton X-100, arguing against gross membrane permeabilization being sufficient for Rcs activation. To test whether envelope stress specific to polycationic structures led to Rcs activation, activity was measured after exposure to a range of subinhibitory concentrations of spermine or spermidine, which are polycationic amines but are not as amphipathic as CAMPs (Table 4). Again, no significant activity was observed upon measurement of Rcs-regulated gene expression for these cationic stimuli. Together, these results reflect remarkable selectivity in Rcs activation by CAMPs that is not specific to generalized envelope permeabilization or polycationic protein structure. These results indicate significant specificity for basic amphipathic peptide disruption of the membrane and suggest that the RcsF system may have evolved to specifically recognize this type of outer membrane disruption.

TABLE 4.

Compounds that induce membrane stress without wza activation

| Compound | Concn testeda | wza::lacZ activationb (Miller units) |

|---|---|---|

| Spermidine | 5-20 mM | — |

| Spermine | 0.25-20 mM | — |

| Triton X-100 | 0.5-10% | — |

| SDS | 0.05-5% | — |

| EDTA | 0.1-10 mM | — |

The range of tested concentrations represents sublethal to lethal concentrations.

The response to each compound was further tested by RT-PCR to avoid the possibility that the compound interfered with beta-galactosidase activity (not shown). —, no activity above background levels.

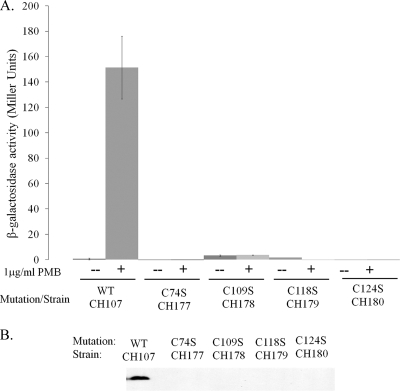

RcsF requires two disulfide linkages for protein stability and Rcs activation by CAMPs.

E. coli RcsF is a 14-kDa lipoprotein routed to the periplasmic side of the OM (9). NCBI BLASTp alignments between S. Typhimurium RcsF and its E. coli K-12 homolog show 91% amino acid identity and conservation of an N-terminal lipobox signal sequence, suggesting that the Salmonella RcsF is also an OM-directed lipoprotein (9, 30). Sequence alignments of Salmonella RcsF with those of more-diverse enterobacterial species revealed conservation of the N-terminal lipobox sequence and 4 internal cysteines in the processed protein that would be available for disulfide bond formation.

Our group recently reported that periplasm-expressed and purified RcsF has two disulfide linkages, between C74-C124 and C109-C118 (43). To investigate whether these linkages were required for Rcs activation, single Cys-to-Ser point mutants were constructed and β-galactosidase activity from the wza::lacZ reporter in response to PMB was measured (Fig. 3A). No β-galactosidase activity from any of the four point mutants in response to PMB was observed, and immunoblots revealed that only traces of the proteins were present, suggesting that the cysteines are required for protein stability (Fig. 3B and data not shown). We next tested whether removal of a cysteine pair (thereby removing a disulfide linkage) would produce the same effect. Removal of a single disulfide bond also abrogated the Rcs response to PMB and led to protein degradation (not shown). Together, these results show that the RcsF lipoprotein requires two disulfide linkages for protein stability and the Rcs response to CAMPs.

FIG. 3.

RcsF Cys→Ser point mutants abrogate the Rcs response to PMB. (A) Single site-directed point mutants of RcsF were constructed from the pCH1 template as described in Materials and Methods. Each point mutant was transformed into CH92 and tested for wza::lacZ activity in response to PMB in LB broth. All point mutants tested were unable to respond to PMB. (B) Immunoblots to detect the HA-tagged mutants revealed little to no traces, suggesting that inactivation is due to protein instability in RcsF in the absence of both disulfide linkages.

Routing of RcsF to the periplasm or the inner membrane activates the Rcs regulon.

It is possible that the mechanism of RcsF-dependent activation involved a change in the physical nature of the envelope such that disorder of the outer membrane resulted in an increased availability of RcsF to the HK RcsC and HPT protein RcsD at the IM. To investigate whether subcellular positioning of RcsF influenced Rcs activation, constructs of RcsF were generated to alter its localization within the envelope.

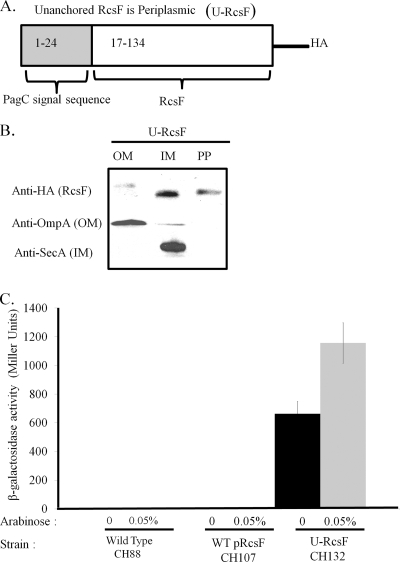

An unanchored construct of RcsF was made by replacing the 5′ nucleotide sequence encoding the first 16 amino acids of RcsF with sequence encoding the first 24 amino acids of the Salmonella PagC protein (Fig. 4A). The PagC N-terminal signal sequence contained in the first 24 amino acids has been shown to be sufficient for periplasmic routing, followed by cleavage of the signal sequence by signal peptidase I, leading to release of the protein into the periplasm (33). This HA-tagged construct, termed U-RcsF, would be routed to the periplasm through the general secretion pathway machinery, recognized by signal peptidase I, and subsequently cleaved after the PagC signal sequence, resulting in release of RcsF into the periplasmic space. pCH3, encoding U-RcsF, was transformed into S. Typhimurium carrying the wza::lacZ reporter to make strain CH132. Subcellular fractionation of CH132 verified that U-RcsF was present primarily in the soluble periplasmic fraction (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Periplasmic RcsF results in constitutive activation. (A) Schematic of unanchored HA-tagged RcsF (U-RcsF). An unanchored version of RcsF was constructed by deleting the first 16 amino acids encoding the secretion and lipoprotein processing information and replacing the sequence with the first 24 amino acids of the S. Typhimurium PagC sequence, which has been shown to be sufficient for periplasmic routing and cleavage by signal peptidase I. (B) CH132 RcsF is periplasmic. Strain CH132, carrying pCH3, was used to verify subcellular routing of RcsF in S. Typhimurium. Cells were induced with 0.05% arabinose and prepared for fractionation as described in Materials and Methods. Protein (5 μg/lane) was loaded and immunoblotted with anti-HA to detect HA-tagged RcsF, anti-OmpA to identify OM constituents, or anti-SecA to detect IM constituents. OM, outer membrane fraction; IM, inner membrane fraction; PP, periplasmic fraction. U-RcsF-HA was found in both the IM and PP fractions. (C) Unanchored RcsF induces constitutive activation of the wza::lacZ reporter. Activation of CH132 was measured in LB broth 60 min past an OD600 of 0.2. Activity was recorded for CH132 with or without 0.05% arabinose induction and compared against that for CH88 (WT) and CH107.

Figure 4C depicts the results of RcsF-dependent transcription, comparing the wild type (CH88), U-RcsF (CH132), and WT pRcsF (CH107). CH107 is a strain isogenic to CH132 but carries pCH1, encoding WT RcsF-HA. In the absence of arabinose and based on minimal basal expression, CH132 alone constitutively activated the wza::lacZ reporter. Addition of 0.05% arabinose to increase transcription from the arabinose promoter upstream of pCH1 and pCH3 increased the β-galactosidase activity of CH132 alone, without resulting in activation in CH88 or CH107. Constitutive activation was not a result of overexpression, as a low arabinose concentration (0.05%) was used, corresponding to the minimal concentration required for CH107 to complement the WT (CH88) response to PMB exposure. The lack of β-galactosidase activity from CH107 verified that the mucoid effect produced by unanchored periplasmic RcsF was not due to Rcs activation by overproduction of RcsF. These results show that the lipidation state of RcsF influences Rcs activity and that removal of the lipid anchor from RcsF leads to constitutive Rcs activation.

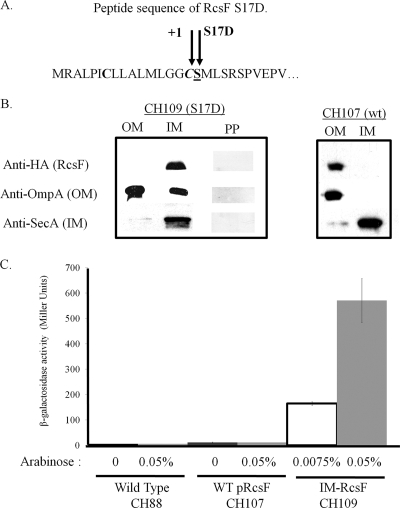

Changing the anchored location of RcsF from the OM to the IM could also produce Rcs activation if it allowed greater access to the inner membrane signaling constituents RcsCD. To test this possibility, a mutant construct of RcsF that rerouted the RcsF lipoprotein from the OM to the IM was generated. The N-terminal sequence of RcsF contains an amino acid lipobox sequence with the cysteine at amino acid 16 positioned to be lipidated to form an N-acyl-diacylglycerylcysteine. Following acylation, the first 15 amino acids are cleaved by signal peptidase II, leaving cysteine 16 as the first N-terminal amino acid, in the “+1” position (Fig. 5A). The adjacent amino acid, labeled the “+2” position, is known to influence membrane routing, with a serine being common for default routing to the outer membrane, as is seen for RcsF (41). Replacing a serine with an aspartic acid in the +2 position can lead to retention of lipoproteins in the IM rather than passage through the default pathway to the OM (41). We used this logic along with site-directed mutagenesis to generate an IM-routed version of the RcsF lipoprotein in the plasmid construct pCH2 and transformed it into the S. Typhimurium wza::lacZ reporter strain to generate strain CH109.

FIG. 5.

IM-routed RcsF causes constitutive activation. (A) N-terminal peptide sequence of RcsF. The +1 position reflects the cysteine predicted to be acylated and the first amino acid present after lipoprotein processing. The +2 position contains a serine that when changed to an aspartate results in IM routing. (B) Subcellular fractions of CH109 show that the RcsF S17D mutant is routed to the IM. Strains CH107, carrying pCH1 (WT RcsF), and CH109, carrying pCH2 (RcsF S17D), were induced with 0.05% arabinose for 1 h and prepared for subcellular fractionation as described in Materials and Methods. Protein (5 μg/lane) was loaded and immunoblotted with anti-HA to detect HA-tagged RcsF, anti-OmpA to identify OM constituents, or anti-SecA to identify IM constituents. Separately, periplasmic fractions of CH109 were immunoblotted to verify that the RcsF S17D mutant is routed exclusively to the IM. As a control, subcellular fractionation of CH107 was performed as described in Materials and Methods. As expected, WT RcsF is routed to the OM. (C) IM-routed RcsF leads to constitutive activation. CH109 was induced with either 0.0075% or 0.05% arabinose in LB broth. Activation was measured 60 min past an OD600 of 0.2. Activity was compared against that for CH88 (WT) and CH107 (pRcsF-HA) induced with 0.05% arabinose.

IM-directed RcsF in CH109 was routed entirely to the inner membrane and constitutively activated the wza::lacZ transcriptional reporter (Fig. 5A and B). As was observed with CH132, the lack of β-galactosidase activity from CH107 verified that the mucoid effect produced by CH109 was not due to Rcs activation by overproduction of RcsF. In the absence of arabinose, CH109 did not constitutively activate the wza::lacZ transcriptional reporter. However, induction with only 0.0075% arabinose was sufficient for CH109 to induce 160 mU of constitutive activity from the wza::lacZ transcriptional reporter, indicating that low levels of IM-routed RcsF are sufficient for constitutive activation.

To verify that constitutive activation by IM-routed or periplasmic RcsF required disulfide linkages, we generated mutant constructs of CH132 and CH109 carrying cysteine-to-serine point mutations. As expected, deletion of any cysteine or cysteine pair resulted in protein degradation and abrogation of activation (not shown). To verify that constitutive activation required both RcsC and RcsD, deletion strains were constructed and tested for activation. As expected, constitutive Rcs activation by either IM-routed or periplasmic RcsF requires both RcsC and RcsD for activation (not shown). Collectively, these results show that the subcellular location of RcsF strongly influences Rcs activation and that small amounts of RcsF made available either anchored at the IM or unanchored in the periplasmic space were sufficient for constitutive Rcs activation.

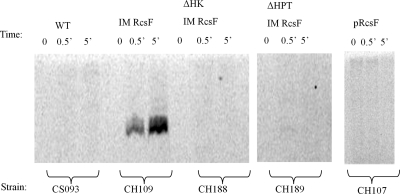

Inner membrane-routed RcsF resulted in RcsC- and RcsD-dependent phosphotransfer.

In vitro phosphotransfer assays were used to verify that constitutive activation of the wza::lacZ transcriptional reporter by IM-routed RcsF results in Rcs-dependent phosphorylation. Total membrane (TM) was harvested from CH109 expressing IM-routed RcsF, and samples were prepared for in vitro phosphorylation according to protocols previously described (22, 40). Briefly, 4 μg TM was added to 2 μCi [γ-33P]ATP (0.67 pmol) and incubated in reaction buffer. Samples were collected at various time points, and the reaction was stopped by adding SDS loading buffer. Reaction mixtures were separated on a 10% criterion XT bis-Tris gel, dried, and exposed on a phosphorimager screen.

A phosphorylated band running at ∼100 kDa was observed from total membrane fractions from strain CH109, carrying IM RcsF (Fig. 6). This phosphorylated product increased over time and required IM-routed RcsF, RcsC, and RcsD. This supported previously described models in which both RcsC and RcsD are required for Rcs signal transduction. Between 30 s and 5 min, there is over a 400-fold to 800-fold increase in signal observed in the presence of IM-routed RcsF. We hypothesize that the 100-kDa protein is likely a result of either the autophosphorylation of 106-kDa RcsC or the phosphotransfer of the HPT protein on the 100-kDa RcsD protein, as both proteins are required for the phosphorylation event and are close in molecular mass and isoelectric point. These results show that expression of IM-routed RcsF led to in vitro Rcs phosphotransfer in an RcsC- and RcsD-dependent manner.

FIG. 6.

Inner membrane-routed RcsF leads to phosphotransfer in vitro. Total membrane was prepared and in vitro phosphotransfer was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Samples were taken at time zero and 30 s (0.5′) and 5 min (5′) after addition of [γ-33P]ATP and prepared for electrophoresis. A phosphorylated band running around 100 kDa was observed in CH109, carrying IM-routed RcsF. Strain CH188 and strain CH189 were used to verify the requirement for RcsC and RcsD for phosphotransfer, respectively. Images taken with a phosphorimager were analyzed using ImageJ software.

DISCUSSION

Two-component systems are used by prokaryotes to sense and respond to membrane stresses, such as cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs). In this work, the substrate specificity for CAMP-induced membrane damage and the role of RcsF in activation of the Rcs phosphorelay were demonstrated. RcsF was required for Rcs activation by PMB as well as three other CAMPs (PMBN, C18G, and LL-37), while a variety of other membrane stresses did not activate the Rcs regulon. Real-time PCR of two Rcs-regulated genes, wza and rprA, showed that the response to PMB was rapid, as it was observed within 5 min of exposure. LPS fatty acid analysis showed an increase in 2-OH C14:0 and C16:0 in response to 30 min of PMB exposure, indicating that membrane alterations can be detected. Targeting RcsF to the inner membrane or the periplasm led to constitutive activation, supporting the idea that activation by CAMPs involved increased access of RcsF to other inner membrane constituents of the regulon.

All of the antimicrobial peptides that activated RcsF in this study are cationic amphipathic molecules, which, in the first step of disruption of the bacterial membrane, are known to bind bacterial outer membrane LPS through electrostatic interaction with the negatively charged phosphates of the lipid A moiety (46, 49). High concentrations of other OM-disrupting agents and polycationic molecules, such as spermine, spermidine, EDTA, SDS, and Triton X-100, did not lead to Rcs activation, suggesting that gross OM permeabilization is not a sufficient signal for Rcs activation. This is specifically notable in the case of EDTA, which chelates magnesium, forming metal bridges between LPS phosphates and therefore in part mimicking the initial interaction of CAMPs with the outer membrane.

The Rcs response to PMBN is particularly interesting because its predominate activity at subinhibitory concentrations is selective permeabilization of the outer membrane to hydrophobic compounds (11, 35, 49). PMBN resulted in Rcs activation at 2.5 μg/ml, which is substantially below its MIC of ≥20 μg/ml in MHB. This concentration of PMBN leads to a substantial increase in OM sensitivity to lipophilic compounds without a release in periplasmic proteins (35, 49). This same effect is seen with PMB exposure but is masked by its bactericidal effects at low concentrations (46, 48, 49). These results indicate that specific outer membrane disruption may be detected by RcsF. Consistent with this interpretation is the finding that the deep rough phenotype caused by an rfaP mutation led to Rcs-mediated capsule production (36). The rfaP mutation causes a truncated LPS core with two heptose residues, which results in OM disorder and increased susceptibility to hydrophobic compounds (14, 36). Given the lipid anchoring of RcsF within the OM inner leaflet, rfaP- or CAMP-induced outer leaflet OM disorder could produce a rearrangement of the membrane environment sufficient to induce a change in location or environment of RcsF, which is somehow sensed by the inner membrane signaling components.

How does RcsF transfer the signal of outer membrane disorder by CAMPs? Subcellular fractionation of chromosomally tagged RcsF suggests that RcsF does not appear to be proteolytically cleaved or to change subcellular location or concentration after CAMP exposure (not shown). However, we cannot rule out that processing may be present but limited by the tools used, since it is likely that at the concentration of CAMP used only a minor or localized portion of membrane is altered, resulting in a change in a relatively small percentage of RcsF molecules. Our observation that trace amounts of unanchored RcsF are sufficient for activation leaves open the possibility that a minor species of RcsF molecules is made available to the signaling components of the inner membrane and that this results in robust levels of signal transduction.

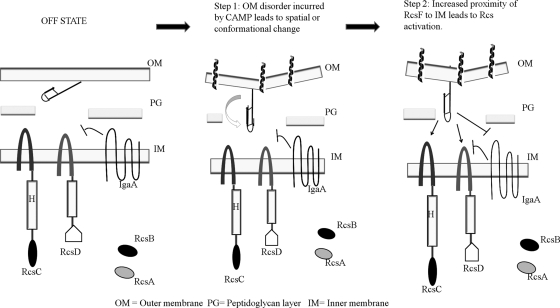

This suggests a model in which a threshold concentration of RcsF is required to be freely available to interact with IM-proximal constituents before Rcs activation occurs. In this model, RcsF is anchored to the OM, sequestered from its signaling partners in the “off state.” During the right kind of envelope disorganization, a conformational or spatial change increases the availability of RcsF to its signaling constituents at the IM, leading to Rcs activation (Fig. 7). We propose that this could occur by two possible mechanisms: (i) envelope disorder could reduce the distance between the OM and the IM as part of membrane repair, allowing RcsF to come in contact with IM signaling constituents, or (ii) sufficient disorder at the OM or periplasmic framework could cause a conformational and/or spatial change in RcsF that increases its availability to the IM constituents (Fig. 7). Consistent with the first mechanism, a study with E. coli exposed to sublethal concentrations of PMB reported increased contact between the IM and the OM phospholipids, showing a reduced periplasmic distance between the membranes during exposure (28).

FIG. 7.

Hypothetical model for RcsF-mediated Rcs activation. RcsF is likely sequestered from the IM in the off state. The two disulfide linkages in RcsF are shown. Step 1, OM disorder incurred by CAMPs leads to a spatial or conformational change in RcsF, resulting in increased proximity to the IM. Step 2, increased proximity of RcsF to the IM leads to Rcs activation by either RcsF activation of RcsCD or inhibition of negative repression by IgaA.

Once RcsF is available to the inner membrane signaling components, how does activation occur? RcsC, RcsD, and the negative regulator IgaA are all candidates for a direct interaction with RcsF (Fig. 7). RcsC, RcsD, and IgaA all have significant periplasmic domains that could directly interact with RcsF. A change in RcsF availability could promote direct, noncovalent interactions with the periplasmic domains of these proteins during the on/off state of the Rcs regulon. One model for this kind of interaction has been proposed for the CpxAR two-component stress response system in Escherichia coli, where an OM lipoprotein, NlpE, is hypothesized to increase availability to the CpxA HK after exposure to copper, leading to activation (25). Therefore, either direct interaction of RcsF with the periplasmic domains of RcsC or RcsD or binding to IgaA and release of inhibition could result in activation. It also remains plausible that an unknown additional periplasmic or inner membrane component of the regulon directly mediates the RcsF effect.

Detection of membrane integrity though the use of membrane-localized proteins is a logical but undefined mechanism for mediating signal transduction. The sensing of specific types of membrane disruption may be important for all organisms but is certainly logical for Gram-negative bacteria, which evolved a two-membrane system as a protection against environmental stresses and to promote environmental sensing and protection. Similar responses may be important to multicellular organisms, as they have recently emerged as critical to the cytoplasmic Nod receptor signaling responses of plants and animals that function as part of the innate immune system (38). Therefore, recognition of specific types of membrane damage and subcellular disorganization is likely an important property of all free-living organisms, from bacteria to plants and mammals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthias Christian for valuable discussions and Dale Whittington for help with gas chromatography.

This work was supported by a grant from the NIAID (AI030479).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews, J. M. 2001. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:5-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arricau, N., D. Hermant, H. Waxin, C. Ecobichon, P. S. Duffey, and M. Y. Popoff. 1998. The RcsB-RcsC regulatory system of Salmonella typhi differentially modulates the expression of invasion proteins, flagellin and Vi antigen in response to osmolarity. Mol. Microbiol. 29:835-850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bader, M. W., W. W. Navarre, W. Shiau, H. Nikaido, J. G. Frye, M. McClelland, F. C. Fang, and S. I. Miller. 2003. Regulation of Salmonella typhimurium virulence gene expression by cationic antimicrobial peptides. Mole. Microbiol. 50:219-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bader, M. W., S. Sanowar, M. E. Daley, A. R. Schneider, U. Cho, W. Xu, R. E. Klevit, H. Le Moual, and S. I. Miller. 2005. Recognition of antimicrobial peptides by a bacterial sensor kinase. Cell 122:461-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baranova, N., and H. Nikaido. 2002. The BaeSR two-component regulatory system activates transcription of the yegMNOB (mdtABCD) transporter gene cluster in Escherichia coli and increases its resistance to novobiocin and deoxycholate. J. Bacteriol. 184:4168-4176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bäumler, A. J., R. M. Tsolis, A. W. M. van der Velden, I. Stojiljkovic, S. Anic, and F. Heffron. 1996. Identification of a new iron regulated locus of Salmonella typhi. Gene 183:207-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowdish, D. M. E., D. J. Davidson, Y. E. Lau, K. Lee, M. G. Scott, and R. E. W. Hancock. 2005. Impact of LL-37 on anti-infective immunity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 77:451-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callewaert, L., K. G. A. Vanoirbeek, I. Lurquin, C. W. Michiels, and A. Aertsen. 2009. The Rcs two-component system regulates expression of lysozyme inhibitors and is induced by exposure to lysozyme. J. Bacteriol. 191:1979-1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castanie-Cornet, M.-P., K. Cam, and A. Jacq. 2006. RcsF is an outer membrane lipoprotein involved in the RcsCDB phosphorelay signaling pathway in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 188:4264-4270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, M. H., S.-I. Takeda, H. Yameda, Y. Ishii, T. Yamashino, and T. Mizuno. 2001. Characterization of the RcsC→YojN→RcsB phosphorelay signaling pathway involved in capsular synthesis in Escherichia coli. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 65:2364-2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danner, R. L., K. A. Joiner, M. Rubin, W. H. Patterson, N. Johnson, K. M. Ayers, and J. E. Parrillo. 1989. Purification, toxicity, and antiendotoxin activity of polymyxin B nonapeptide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:1428-1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darveau, R. P., and R. E. Hancock. 1983. Procedure for isolation of bacterial lipopolysaccharides from both smooth and rough Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Salmonella typhimurium strains. J. Bacteriol. 155:831-838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Decad, G. M., and H. Nikaido. 1976. Outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. XII. Molecular-sieving function of cell wall. J. Bacteriol. 128:325-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Detweiler, C. S., D. M. Monack, I. E. Brodsky, H. Mathew, and S. Falkow. 2003. virK, somA and rcsC are important for systemic Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection and cationic peptide resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 48:385-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eastman, S. W., and M. L. Linial. 2001. Identification of a conserved residue of foamy virus Gag required for intracellular capsid assembly. J. Virol. 75:6857-6864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebel, W., G. J. Vaughn, H. K. Peters III, and J. E. Trempy. 1997. Inactivation of mdoH leads to increased expression of colanic acid capsular polysaccharide in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:6858-6861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erickson, K. D., and C. S. Detweiler. 2006. The Rcs phosphorelay system is specific to enteric pathogens/commensals and activates ydeI, a gene important for persistent Salmonella infection of mice. Mol. Microbiol. 62:883-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ernst, R. K., T. Guina, and S. I. Miller. 2001. Salmonella typhimurium outer membrane remodeling: role in resistance to host innate immunity. Microbes Infect. 3:1327-1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrières, L., and D. J. Clarke. 2003. The RcsC sensor kinase is required for normal biofilm formation in Escherichia coli K-12 and controls the expression of a regulon in response to growth on a solid surface. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1665-1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guina, T., C. Y. Eugene, W. Houle, H. Murray, and S. I. Miller. 2000. A PhoP-regulated outer membrane protease of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium promotes resistance to alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides. J. Bacteriol. 182:4077-4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunn, J. S., E. L. Hohmann, and S. I. Miller. 1996. Transcriptional regulation of Salmonella virulence: a PhoQ periplasmic domain mutation results in increased net phosphotransfer to PhoP. J. Bacteriol. 178:6369-6373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagiwara, D., M. Sugiura, T. Oshima, H. Mori, H. Aiba, T. Yamashino, and T. Mizuno. 2003. Genome-wide analyses revealing a signaling network of the RcsC-YojN-RcsB phosphorelay system in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:5735-5746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haraga, A., M. B. Ohlson, and S. I. Miller. 2008. Salmonellae interplay with host cells. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:53-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirano, Y., M. M. Hossain, K. Takeda, H. Tokuda, and K. Miki. 2007. Structural studies of the Cpx pathway activator NlpE on the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Structure 15:963-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawasaki, K., R. K. Ernst, and S. I. Miller. 2005. Purification and characterization of deacylated and/or palmitoylated lipid A species unique to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Endotoxin Res. 11:57-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laubacher, M. E., and S. E. Ades. 2008. The Rcs phosphorelay is a cell envelope stress response activated by peptidoglycan stress and contributes to intrinsic antibiotic resistance. J. Bacteriol. 190:2065-2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liechty, A., J. Chen, and M. K. Jain. 2000. Origin of antibacterial stasis by polymyxin B in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1463:55-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majdalani, N., and S. Gottesman. 2005. The Rcs phosphorelay: a complex signal transduction system. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59:379-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majdalani, N., M. Heck, V. Stout, and S. Gottesman. 2005. Role of RcsF in signaling to the Rcs phosphorelay pathway in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 187:6770-6778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maloy, S. R., V. J. Stewart, and R. K. Taylor. 1996. Genetic analysis of pathogenic bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 32.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 33.Miller, V. L., K. B. Beer, W. P. Loomis, J. A. Olson, and S. I. Miller. 1992. An unusual pagC::TnphoA mutation leads to an invasion- and virulence-defective phenotype in salmonellae. Infect. Immun. 60:3763-3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murata, T., W. Tseng, T. Guina, S. I. Miller, and H. Nikaido. 2007. PhoPQ-mediated regulation produces a more robust permeability barrier in the outer membrane of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 189:7213-7222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ofek, I., S. Cohen, R. Rahmani, K. Kabha, D. Tamarkin, Y. Herzig, and E. Rubinstein. 1994. Antibacterial synergism of polymyxin B nonapeptide and hydrophobic antibiotics in experimental gram-negative infections in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:374-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker, C. T., A. W. Kloser, C. A. Schnaitman, M. A. Stein, S. Gottesman, and B. W. Gibson. 1992. Role of the rfaG and rfaP genes in determining the lipopolysaccharide core structure and cell surface properties of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 174:2525-2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raivio, T. L. 2005. Envelope stress responses and Gram-negative bacterial pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 56:1119-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rasmussen, S. B., L. S. Reinert, and S. R. Paludan. 2009. Innate recognition of intracellular pathogens: detection and activation of the first line of defense. APMIS 117:323-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sailer, F. C., B. M. Meberg, and K. D. Young. 2003. Beta-lactam induction of colanic acid gene expression in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 226:245-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanowar, S., A. Martel, and H. L. Moual. 2003. Mutational analysis of the residue at position 48 in the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoQ sensor kinase. J. Bacteriol. 185:1935-1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seydel, A., P. Gounon, and A. P. Pugsley. 1999. Testing the ‘+2 rule’ for lipoprotein sorting in the Escherichia coli cell envelope with a new genetic selection. Mol. Microbiol. 34:810-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shiba, Y., Y. Yokoyama, Y. Aono, T. Kiuchi, J. Kusaka, K. Matsumoto, and H. Hara. 2004. Activation of the Rcs signal transduction system is responsible for the thermosensitive growth defect of an Escherichia coli mutant lacking phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin. J. Bacteriol. 186:6526-6535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh, P., S. A. Shaffer, A. Scherl, C. Holman, R. A. Pfuetzner, T. J. Larson Freeman, S. I. Miller, P. Hernandez, R. D. Appel, and D. R. Goodlett. 2008. Characterization of protein cross-links via mass spectrometry and an open-modification search strategy. Anal. Chem. 80:8799-8806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sledjeski, D. D., and S. Gottesman. 1996. Osmotic shock induction of capsule synthesis in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 178:1204-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stock, A. M., V. L. Robinson, and P. N. Goudreau. 2000. Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:183-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Storm, D. R., K. S. Rosenthal, and P. E. Swanson. 1977. Polymyxin and related peptide antibiotics. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 46:723-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tobe, T., H. Ando, H. Ishikawa, H. Abe, K. Tashiro, T. Hayashi, S. Kuhara, and S. Nakaba. 2005. Dual regulatory pathways integrating the RcsC-RcsD-RcsB signalling system control enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli pathogenicity. Mol. Microbiol. 58:320-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vaara, M. 1992. Agents that increase the permeability of the outer membrane. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 56:395-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaara, M., and T. Vaara. 1983. Polycations as outer membrane-disorganizing agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 24:114-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang, Q., Y. Zhao, M. McClelland, and R. M. Harshey. 2007. The RcsCDB signaling system and swarming motility in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium: dual regulation of flagellar and SPI-2 virulence genes. J. Bacteriol. 189:8447-8457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]