Abstract

Background

Transcription is affected by nucleosomal resistance against polymerase passage. In turn, nucleosomal resistance is determined by DNA sequence, histone chaperones and remodeling enzymes. The contributions of these factors are widely debated: one recent title claims “… DNA-encoded nucleosome organization…” while another title states that “histone-DNA interactions are not the major determinant of nucleosome positions.” These opposing conclusions were drawn from similar experiments analyzed by idealized methods. We attempt to resolve this controversy to reveal nucleosomal competency for transcription.

Methodology/Principal Findings

To this end, we analyzed 26 in vivo, nonlinked, and in vitro genome-wide nucleosome maps/replicates by new, rigorous methods. Individual H2A nucleosomes are reconstituted inaccurately by transcription, chaperones and remodeling enzymes. At gene centers, weakly positioned nucleosome arrays facilitate rapid histone eviction and remodeling, easing polymerase passage. Fuzzy positioning is not due to artefacts. At the regional level, transcriptional competency is strongly influenced by intrinsic histone-DNA affinities. This is confirmed by reproducing the high in vivo occupancy of translated regions and the low occupancy of intergenic regions in reconstitutions from purified DNA and histones. Regional level occupancy patterns are protected from invading histones by nucleosome excluding sequences and barrier nucleosomes at gene boundaries and within genes.

Conclusions/Significance

Dense arrays of weakly positioned nucleosomes appear to be necessary for transcription. Weak positioning at exons facilitates temporary remodeling, polymerase passage and hence the competency for transcription. At regional levels, the DNA sequence plays a major role in determining these features but positions of individual nucleosomes are typically modified by transcription, chaperones and enzymes. This competency is reduced at intergenic regions by sequence features, barrier nucleosomes, and proteins, preventing accessibility regulation of untargeted genes. This combination of DNA- and protein-influenced positioning regulates DNA accessibility and competence for regulatory protein binding and transcription. Interactive nucleosome displays are offered at http://chromatin.unl.edu/cgi-bin/skyline.cgi.

Introduction

Nucleosomal resistance against RNA polymerase II (Pol II)-induced remodeling and eviction may regulate the speed of transcription. What determines the strength of nucleosome positions is a subject to intense debate. Fundamentally “DNA-encoded nucleosome organization” is advocated by Kaplan et al. [1] in the Segal, Widom and Lieb laboratories, while “intrinsic histone-DNA interactions” are considered only as minor determinants of the in vivo nucleosome positions by Zhang et al. [2] in Struhl and Liu's laboratories. Most notably, Kaplan et al. [1] strongly correlated in vitro reconstruction with the five base pair (bp) sequence preferences of nucleosomes (r = 0.83). Zhang et al. [2] estimated that intrinsic histone-DNA interactions account for only ∼20% of the in vivo positions because “nucleosomes assembled in vitro have only limited preference for specific translational positions and do not show the patterns observed in vivo.” These opposing conclusions were drawn from compatible experiments but incompatible data analysis. These experiments shared an identical concept: reconstitute nucleosomes in vitro from purified chicken or Drosophila histones and yeast DNA. The differences were limited to experimental implementations and interpretations. As Zhang et al. pointed out, their group used a nonlimiting histone∶DNA ratio of 1∶1 to simulate the high in vivo nucleosome occupancy, while Kaplan et al. used a lower ratio of 0.4∶1 that allowed the limiting histones to occupy the highest affinity DNA loci and leave many less affine in vivo loci vacant. Because higher affinity reduces the probability of inaccurate remodeling, this competition inflated the correlation between in vivo and in vitro nucleosome occupancy (“histone density”, from 0.54 in Zhang et al. to 0.74 in Kaplan et al.).

This debate resurfaced on Correspondence pages of Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. Kaplan et al. [3] now published numerical estimates for the DNA's influence on nucleosome positioning. Depending on the methods and parameter values used, this ranges as wide as 34–57%. In their reply, Zhang et al. [4], and in a separate comment, Franklin Pugh [5] raised objections against using nucleosome occupancy to estimate nucleosome positioning. Zhang et al. [4] reiterated that as few as “∼20% of the in vivo positioned nucleosomes are positioned due to intrinsic histone-DNA interactions.” The most notable progress is some departure from the “code” concept for nucleosome positioning: now Kaplan et al. [3] “leave for others to debate” whether the influence of DNA on many aspects of the in vivo nucleosome organization reflects the use of a code.”

By partially resolving this controversy, we aimed to improve our understanding of the chromatin's competency for transcription. In doing so, we carefully avoided directly estimating the influence of intrinsic histone-DNA affinities on nucleosome positioning because of their extreme sensitivity for the choice of methods and parameter values. In a more robust approach, we compared nucleosome occupancy and dynamics patterns between different gene and genomic regions (GGRs). We observed similar occupancy and dynamism patterns both in vivo or in vitro under diverse conditions across twenty six high-coverage maps of nucleosomes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae [1], [2], [6], [7], [8], [9]. These maps were generated by Chromatin ImmunoPrecipitation (ChIP-seq) or micrococcal nuclease digestion (MNase-seq) and deep sequencing [10]. We analyzed signal and noise using admittedly unattractive but unbiased displays and statistics of the sequencing tag density profiles of the genome. We also introduce here a robust algorithm for calling nucleosome peaks. Specifically, we examined how nucleosomes were remodeled during transcription or by histone chaperones [11] and chromatin remodeling enzymes [12]. We compared in vivo positions to positions of nucleosomes reconstituted from purified DNA and histones in yeast [1], [2] and sheep [13], [14].

To allow Pol II passage, DNA replication and DNA repair, nucleosomes need to be evicted or remodeled at least partially or temporarily. In vitro, Pol II can pass through nucleosomes by forming DNA bubbles [15], [16] but in vivo, the Pol II complex may force histone octamers to completely dissociate from the DNA [17]. Alternatively, the FACilitator of Transcription (FACT) complex can evict only a single H2A–H2B dimer [18]. In either case, nucleosomes are reconstructed within a minute if FACT, SWI/SNF, and the histone chaperone ACT1 are present [19], [20], [21]. Independently of transcription, nucleosome octamers and hexamers can slide on the DNA either spontaneously or assisted by powerful ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes [22]: RSC in yeast and ACHF in human can reposition nucleosomes to DNA loci that are thousand times less affine to histones than the original loci [23].

Traces of remodeling are reproducible in the nucleosome maps. We found that high-level nucleosome occupancy is similar in vivo and in maps of nucleosomes reconstituted by salt dialysis, showing that occupancy at the level of most GGRs is strongly influenced by the sequence of DNA. Weak histone-DNA affinities appear to facilitate nucleosome remodeling at transcriptional landmarks even when reconstituted in vitro in the absence of the transcriptional apparatus. However, at the level of individual nucleosomes, inaccurate in vivo remodeling and sliding are likely due to transcription, remodeling enzymes or chaperones [24], [25].

Remodeling signals can be deconvoluted from the considerable noise. Fuzzy reconstitutions are shown by the reproducibility, width and height of these peaks. Our minimally biased peak calling algorithm allowed us to overlay peak distributions on GGRs and to identify statistically significant trends and patterns from 26 experiments/replicates. We found that in vivo, most nucleosomes reposition in a range of 156–174 bp compared to the ∼147-bp footprint of a single histone octamer on DNA in crystallographic studies [26]. Nucleosomes slide and/or reposition more intensively in vivo in the presence of chaperones and remodeling enzymes than in nonlinked experiments, where histones were not cross-linked to their in vivo loci by formaldehyde. The fuzziest peaks were formed by nucleosomes reconstituted from purified histones and DNA either in yeast [1], [2] or sheep [13], [14], [27]. Intensive eviction and fuzzy remodeling at the centers of transcriptionally active genes indicate Pol II-complex-mediated remodeling. This remodeling is subject to at least two constraints. First, most individual nucleosomes reposition around well-defined centers and seldom invade ranges of other nucleosomes. Second, nucleosome remodeling is also constrained to gene boundaries or shorter limits, possibly to prevent the accessibility regulation of untargeted genes.

Results

Reproducible, regional nucleosome occupancy patterns are due to intrinsic histone-DNA affinities

We define protein-influenced positioning as the combined effects of the transcriptional apparatus, chaperones and remodeling enzymes. The extent to which transcriptional competency is influenced by the DNA versus proteins by can be estimated by comparing in vivo and in vitro maps [1], [2]. To resolve the published opposing conclusions, we perform such comparisons both at the levels of GGRs and at the level of individual nucleosomes. These comparisons are based both on nucleosome occupancy and the width of the nucleosome peaks. Occupancy roughly indicates the fraction of a region occupied by nucleosomes in the average of multiple cells. This robust measure does not depend on peak calls and works well even on maps generated from end-primed short reads. To allow comparisons of diverse experiments, we define standardized nucleosome occupancy as the difference between the average density of sequencing tags over a region and the genome-wise average divided by the genome-wide standard deviation of tag density. Conveniently, standardization leads to zero mean and unit standard deviation over the genome (see Methods and Figures 1–2). Standardization also mitigates extremely high read-density peaks caused by amplification bias [28], low sequence complexity or frequent sequence motifs. Because correction for such biases, to our best knowledge, remains an open problem, we cannot meaningfully estimate occupancy on a zero-to-one scale. Another issue is the division by genome-wise standard deviations that differ between experiments. This was necessary for visualization purposes but it may have inflated the similarity between experiments on Figure 1. Fortunately, we performed the statistical tests on raw, unstandardized occupancy distributions to find unbiased, significant differences between GGRs within the same experiment.

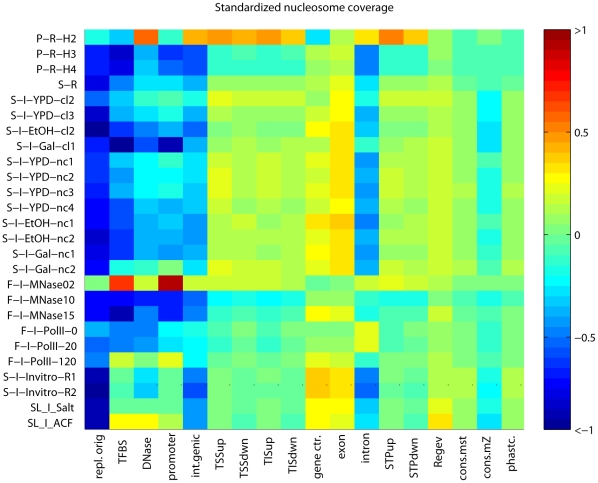

Figure 1. Standardized nucleosome occupancy at GGRs.

Sequencing tag density values are standardized to zero mean and unit standard deviation. General nucleosomes are abundant in exons, and conserved regions. H2A.Z nucleosomes are overrepresented around the TIS, upstream of the STOP codons and in introns. Experiments are coded as follows: the first letter indicates the last or the last two authors (“P” for Pugh [7], [8], “S” for Segal [1], [6], “F” for Friedman [9],“A” for Allan [14], [27], “SL” for Liu and Struhl [2]); the second letter indicates the deep sequencing platform (“R” for Roche/454 and “I” for Illumina/Solexa); “H2A.Z”, “H3” or “H4” stands for the specificity of the antibody used; and the carbon source is indicated by “YPD” for glucose, “EtOH” for ethanol and “Gal” for galactose. “cl” indicates histones cross-linked to the DNA in vivo, “nc” indicates the no cross-linking, both followed by replicate numbers. The number after “MNase” indicates the micromolar concentration of the enzyme, and the number after RNAP (Pol II) show the minutes after heat inactivation of the thermo-sensitive Pol II mutant [9]. “Invitro” refers to the Segal group's in vitro reconstitutions, [1] “Salt” indicates reconstitution followed by salt extraction, and “ACF1” stands for reconstitution in the presence of the Drosophila ACF1 and Nap1 histone chaperones [2]. . “Regev” indicates the deep sequencing transcriptome published by the Regev laboratory [37], “cons. mst. stands for the most conserved regions, cons.mZ for multiZ conserved regions, phastcon. for phastcons regions [36].

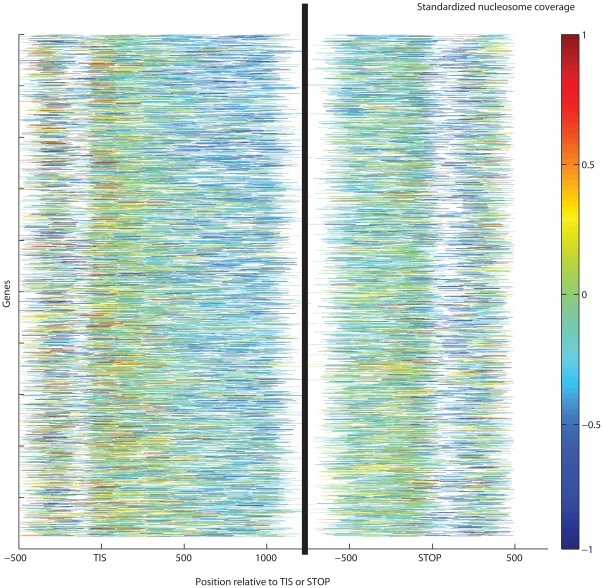

Figure 2. Patterns of standardized nucleosome occupancy across all yeast genes.

Lower occupancy shows incomplete nucleosome reconstruction at the mid-thirds of abundantly transcribed genes. The ±300 bp neighborhoods of TIS and STOP codon display higher nucleosome coverage. Genes are ordered by median transcript level in a compendium of gene expression experiments [41] with the most actively transcribed genes at the top. We show the Segal laboratory's in vivo Illumina experiment with galactose carbon source [1].

The nucleosome occupancy of most GGRs is specific and highly reproducible across the majority of experiments. This reproducibility is moderately biased by standardization. It is highly visible on heat maps of nucleosome occupancy where experiments are represented as rows and GGRs as columns (Figure 1). The striking column-wise patterns indicate the reproducibility of the GGR-wise occupancy across many experiments. Most notably, the occupancy of gene centers exceeds the genomic average by ∼0.2 standard deviation (sd) units. The exceptions are the H2A.Z nucleosomes [7], known to be depleted in translated regions and the experiment with low-concentration MNase that creates artificial coverage at linker regions [9]. At exons and certain noncoding transcripts, occupancy was ∼0.1 sd unit higher than in the genomic average. This indicates that nucleosome presence is necessary for transcription, and temporarily or partly evicted nucleosomes may be fully reconstituted following Pol II passage. In contrast, the occupancy of the ±300 bp neighborhoods of TIS and STOP codons are close to the genomic average. Possibly due to Pol II pausing or slow progression immediately downstream of the TIS [29], nucleosomes or potential agents anchoring them in the 5′ untranslated region and in the first third of the coding region may have the strongest role in downregulating transcription. Below we support these results by nucleosome dynamics results using consistently called nucleosome peaks.

AT-rich regions are known to disfavor nucleosomes [30], therefore a considerable nucleosome depletion at replication origins (∼−0.5 sd units below the genomic average) is in accordance with earlier small-scale experiments [31] . We also confirmed significant depletion at intergenic regions (∼−0.2–−0.3 sd units, p<10−300,Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney (WMW) test performed on the raw, unstandardized data, see Methods), in particular at all regulatory regions such as promoters [7], [32], [33], transcription factor binding sites and DNase hypersensitive regions [34]. Significantly high occupancy was confirmed for H2A.Z nucleosomes at promoter termini and introns, in the vicinity of TSS, TIS and STOP codons (Figures 1–2).

Wide nucleosome peaks indicate fuzzy remodeling of H2A nucleosomes

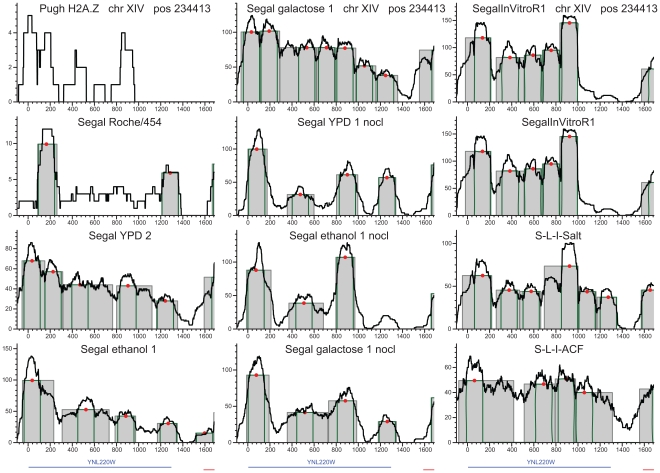

A simple visual inspection at our web site (http://chromatin.unl.edu/cgi-bin/skyline.cgi) reveals that sequencing tags mapped to the genome form peaks diverse in shape, width and height. Most of these peaks extend considerably wider than the single-nucleosome footprint obtained in crystallographic studies [26]. This is primarily due to fuzzy remodeling as opposed to incomplete digestion and other experimental issues. We confirm that by systematic comparisons to those nucleosomes where the canonical H2A subunits are replaced by variant H2A.Z subunits (Figure 3, for details, see the section “Are wide nucleosome peaks due to remodeling or experimental noise” below). Most H2A.Z nucleosomes are well-positioned [7], their average width barely exceeds the 147 bp footprint of a single histone octamer.

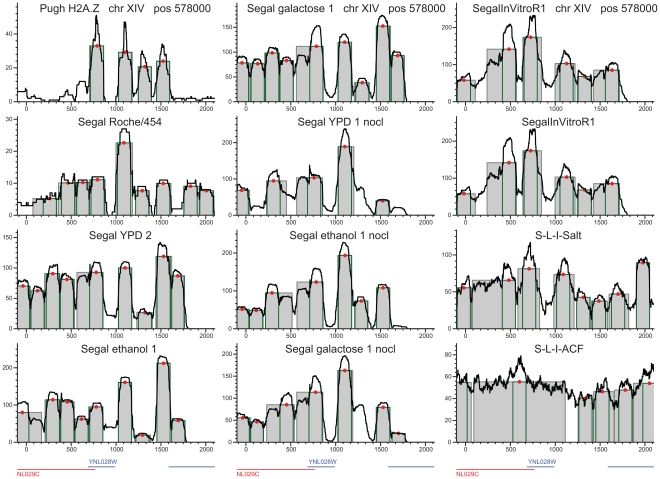

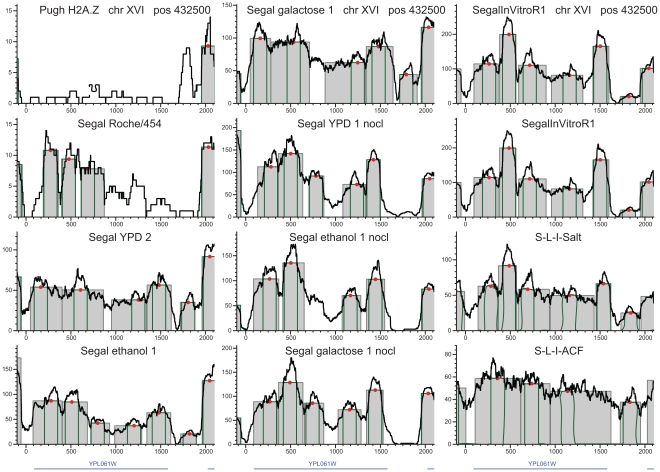

Figure 3. Reproducible positioning of four H2A.Z nucleosomes at chromosome XIV.

H2A.Z nucleosomes are indicated on the same loci in vivo, nonlinked and in the salt extraction reconstitution experiment as well. The only exception is the reconstitution with the ACF1 histone scaffold, which interfered with accurate, DNA-influenced positioning. The density of sequencing tags is shown by black lines. Peak location calls are displayed as gray rectangles and green outlines indicate the single octamer footprint. Red dots represent the peak's center of gravity. These H2A.Z peaks barely extend beyond the single octamer footprint, in sharp contrast to the nucleosomes in the middle of the coding regions.

While Roger Kornberg and coworkers advocated nucleosome positioning by remodeling agents and random factors [24], [25], [35], [36], advocates of DNA-encoded positioning idealized nucleosome peaks to the width of the single-nucleosome footprint by loess normalization or wavelets [7], [8], [37]. Unbiased remodeling information needs to be preserved because each ChIP/MNase-seq DNA segment whose tags form a nucleosome peak may represent a different cell, and nucleosomes in different cells may occupy somewhat different genomic loci. To take this into account, Weiner et al. identified peaks by template filtering using seven templates [9]. As a further improvement, we introduce a consistent, template-free, and fully reproducible peak calling algorithm that is minimally biased by hypotheses about peak width, shape and other parameters (see Methods). Consistent calls across the whole genome and experiments allowed us to compare in vivo, nonlinked and in vitro nucleosome peaks. We also compared results of the Illumina vs. Roche/454 sequencing, growth media experiments, and replicates that quantify biological and technological variation. Users can access interactive, visual displays of peak calls and the undistorted density profiles of sequencing tags at our web server: http://chromatin.unl.edu/cgi-bin/skyline.cgi.

Nucleosome remodeling and transcription

Our results confirmed the sharp contrast between the two basic classes of nucleosomes. H2A.Z nucleosomes are typically located around promoter regions. H2A.Z peaks are tall, well-defined, and barely exceed the 147 bp width of the single-octamer footprint [26] (Figure 3). In contrast, most nucleosomes with the canonical H2A subunits form wide, irregular peaks with multiple rises and drops in the tag density profile (Figures 4–5, S1, S2, S3, S4, S5). These patterns manifest on the gene for cytosolic aldehyde dehydrogenase 6 (ALDH6, Figure 4 [38]). Notwithstanding constitutive expression, four-to-five peaks cover most of ALDH6 gene, all negative for the H2A.Z variant. Peaks are moderately reproducible in vivo but separate better in nonlinked experiments. This indicates that intrinsic histone-DNA affinities play minor roles in positioning individual H2A nucleosomes in vivo, and that these positions are frequently modified by the transcriptional apparatus, chaperones and remodeling enzymes. Reconstitutions from purified DNA and histones [2] produced extremely fuzzy peaks. Within a peak, multiple summits in tag density indicate competing maxima of histone-DNA affinity, and nucleosomes appear to jump from one competing maximum to another. The histone chaperone ACF1 tends to further delocalize the nucleosome peaks in vitro. In our opinion, however, this observation does not exclude primarily DNA-influenced nucleosome positioning because positioning to the maxima of histone-DNA affinity may require remodeling enzymes. In vivo, fuzzy positioning is apparent in the gene for ADE12, adenylosuccinate synthase, particularly at the middle of the coding sequence (Figure 5). Mid-gene remodeling is abundant at the gene for the MED2 subunit of the Pol II mediator complex (Figure S1); SMC5, structural maintenance of chromosomes (Figure S2); LDB17 (Figure S3); or the SR077 gene (Figure S4).

Figure 4. Nucleosome peaks at the constitutively expressed gene for cytosolic aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALD6).

The peaks between the relative positions of 200 to 760 bp and 960 to 1560 bp show extensive sliding or remodeling. Nucleosome positioning is more statistical in vivo than in the nonlinked experiments, particularly in the mid-third of the coding region.

Figure 5. In vivo, nucleosomes occupy alternative positions, particularly in the middle of the ADE12 gene that codes for adenylosuccinate synthase.

Better focused positioning is observed in nonlinked experiments and in reconstitutions following salt extraction. Reconstitutions with the ACF1 chaperone produce fuzzier positioning.

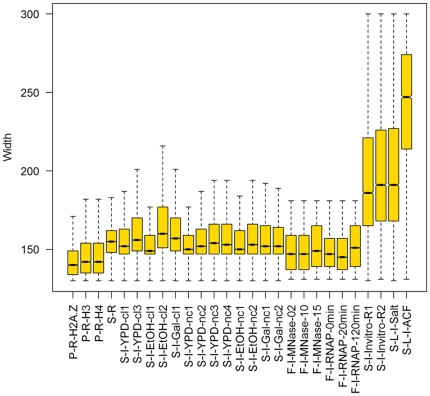

These individual observations are generalized by genome-wide statistics. A quarter of the in vivo H2A-peaks extend to 159–179 bp or wider (Figure 6, Table 1), and the widest 10% of peaks span to 177–200 bp or wider. Nonlinked nucleosomes form somewhat narrower peaks (average: 158–163 bp, p<10−300, WMW test). Each of these peaks consists of hundreds of sequencing tags. In turn, these tags come from a still considerable number of DNA segments, each representing a different yeast cell. Therefore peak widths reveal the positional variation of the histones on the DNA subject to experimental noise such as incomplete digestion by the MNase enzyme.

Figure 6. Nucleosome remodeling as reflected by the width distributions of nucleosome peaks.

H2A.Z nucleosomes (less than 10% of the total) form regular peaks but most general nucleosome peaks span considerably wider than the single octamer footprint of 147 bp. In vivo peaks are significantly wider than nonlinked peaks. Reconstituted nucleosomes frequently delocalize to ill-defined peaks wider than 200 bp. Note that peaks in end-primed experiments with short reads (diverse MNase levels and RNA Pol II mutants) were called by template filtering and hence not comparable to the other experiments.

Table 1. The prevalence of extended nucleosome peaks.

| Experiment | Peak width, bp | Number of peaks | Mean peak coverage | ||||

| Mean | Median | 75th | 90th | std | |||

| percentile | |||||||

| P-R-H2A.Z | 152 | 149 | 158 | 171 | 13 | 2,873 | 21 |

| P-R-H3 | 157 | 152 | 163 | 179 | 18 | 4,833 | 43 |

| P-R-H4 | 156 | 151 | 163 | 177 | 17 | 4,504 | 29 |

| S-R | 160 | 157 | 164 | 174 | 18 | 23,530 | 9 |

| S-I-YPD-cl2 | 161 | 153 | 164 | 183 | 25 | 12,753 | 87 |

| S-I-YPD-cl3 | 167 | 157 | 172 | 198 | 28 | 16,566 | 55 |

| S-I-EtOH-cl1∧ | 157 | 149 | 159 | 177 | 20 | 14,934 | 114 |

| S-I-EtOH-cl2 | 174 | 161 | 179 | 227 | 37 | 19,223 | 82 |

| S-I-Gal-cl1 | 168 | 158 | 172 | 200 | 32 | 23,023 | 94 |

| S-I-YPD-nc1 | 158 | 151 | 160 | 180 | 19 | 18,747 | 107 |

| S-I-YPD-nc2 | 160 | 153 | 163 | 185 | 22 | 17,029 | 130 |

| S-I-YPD-nc3 | 162 | 154 | 167 | 190 | 24 | 18,181 | 124 |

| S-I-YPD-nc4 | 163 | 154 | 167 | 192 | 25 | 17,498 | 128 |

| S-I-EtOH-nc1 | 160 | 151 | 163 | 187 | 23 | 21,523 | 98 |

| S-I-EtOH-nc2 | 163 | 154 | 167 | 192 | 25 | 17,432 | 108 |

| S-I-Gal-nc1 | 162 | 153 | 166 | 191 | 24 | 22,866 | 85 |

| S-I-Gal-nc2 | 160 | 153 | 164 | 186 | 21 | 19,807 | 132 |

| F-I-MNase-02* | 150 | 147 | 159 | 173 | 14 | 31,261 | 29 |

| F-I-MNase-10* | 150 | 147 | 159 | 1173 | 14 | 32,048 | 15 |

| F-I-MNase-15* | 152 | 149 | 165 | 175 | 15 | 26,432 | 49 |

| F-I-RNAP-0* | 136 | 137 | 149 | 163 | 20 | 62,538 | 31 |

| F-I-RNAP-20* | 132 | 131 | 147 | 161 | 21 | 62,582 | 26 |

| F-I-RNAP-120* | 134 | 131 | 151 | 169 | 23 | 53,686 | 30 |

| S-I-Invitro-R1 | 197 | 185 | 219 | 263 | 40 | 30,941 | 82 |

| S-I-Invitro-R2 | 200 | 190 | 224 | 265 | 40 | 28,289 | 79 |

| SL-I-Salt† | 163 | 157 | 166 | 178 | 24 | 34,717 | 268 |

| SL-I-ACF† | 211 | 206 | 235 | 264 | 35 | 13,655 | 188 |

| A-I-sheep† | 174 | 169 | 190 | 232 | 39 | 29 | 8,793 |

| A-R-sheep† | 209 | 200 | 228 | 276 | 40 | 29 | 1,305 |

The S-I-EtOH-cl1 replicate was more random than the comparable experiments and was excluded from further analyses.

*Peaks in these end-primed experiments are called by Weiner et al.'s (2010) template filtering method.

In reconstitutions from purified DNA and histones, the highly random protein-influenced positioning frequently makes peak calling uncertain (see Figure S5).

The distributions of peak widths, the numbers of peaks are shown, along with the mean density of uniquely mapping sequencing tags at all peaks. For the abbreviations of experiments, refer to Figure 1.

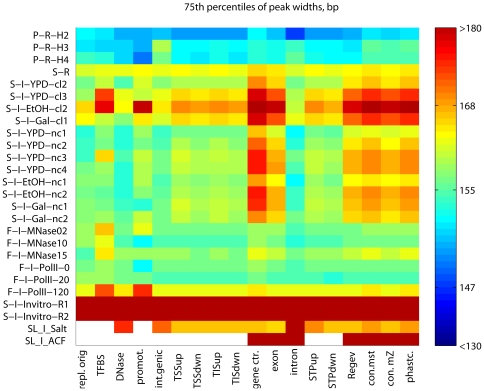

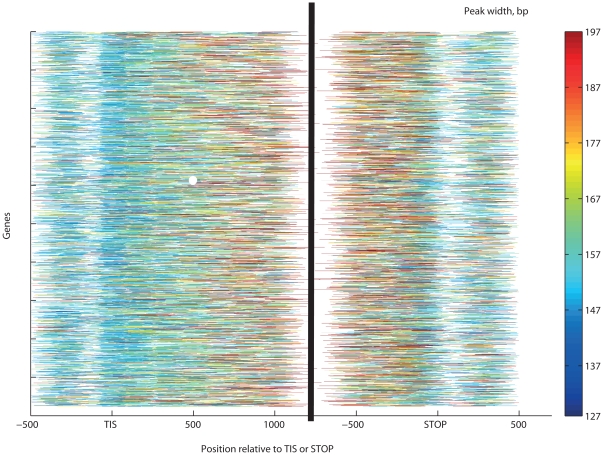

Our results indicate that positional variation is caused primarily by transcription-related nucleosome remodeling and eviction. This would imply higher dynamism at genic regions where Pol II is most active. Indeed, GGRs have very specific positioning strength patterns that are reproducible across most experiments (Figure 7), much like the patterns of nucleosome occupancy above. Unusually wide nucleosome peaks (denoted by hot colors) are particularly abundant at the centers of the transcriptionally active genes and at conserved noncoding DNA elements [39], while narrow peaks (blue colors) are concentrated in promoter and intergenic regions. Most H2A.Z nucleosomes form narrow peaks, close to the single-octamer footprint. In vivo, peaks expanded wider (169±22 bp) than in the ±300 bp neighborhood of the TSS, TIS or STOP codons (160±21, 151±14 and 155±14 bp, respectively, all with p<10−300, WMW test; Figure 7). Peaks span wider in protein-coding genes and deep sequencing transcripts [40] than in intergenic regions or the few introns in yeast. The top expression quartile of genes from [41] harbors somewhat wider peaks than the lowest quartile (means: 176 vs. 172 bp, respectively, p = 0.002; Figure 8). From the extended peaks, particularly at the centers of transcriptionally active genes, we infer that nucleosomes are reconstituted with an inaccuracy of ∼20 bp. The more accurately positioned nucleosomes, however, stop repositioning near the intergenic regions.

Figure 7. GGRs have characteristic patterns of nucleosome dynamism.

We show the 75th percentiles of the peak width distributions. Only H2A.Z peaks, the heavily size-fractionated P-R-H3 and P-R-H4 experiments, and peaks predicted by template filtering (F-I-MNase10 through F-I-RNAP-120m) do not exceed width of the single-octamer footprint.

Figure 8. Gene-wise patterns of nucleosome repositioning as indicated by peak widths.

Color codes indicate standardized nucleosome occupancy, and white indicates the absence of sequencing tags or nucleosomes callable by our method. The most active repositioning was found in the mid-third of coding sequences (171±44 bp). Significantly narrower peaks were found in the ±300 bp environment of the TIS (162±41 bp) or the STOP codon (161±41 bp). Most well-positioned nucleosomes are located in the proximity of TIS and the STOP codons.

The variable strength of DNA-influenced positioning is most visible on the in vitro nucleosome reconstitutions from purified ovine β-lactoglobulin DNA and chicken erythrocyte histones in the absence of histone chaperones and remodeling enzymes [13], [14], [27] (Figure S5). Intrinsic histone-DNA affinities are likely to be responsible for the high summits in these exceptionally high-coverage experiments. However, most peaks are not separated well from each other and many peaks appear to be merged. Similar, often fuzzy positioning was revealed by yeast reconstitution experiments (Figures 3– 5 and S1, S2, S3, S4) [1], [2].

Are wide nucleosome peaks due to remodeling or experimental noise?

We have been concerned regarding experimental error in chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing [ChIP-seq, 10, 42] and in the differential digestion of the excess DNA by micrococcal nuclease (MNase) [43]. Field et al. [6] found that in over a million of MNase cleavage sites, sequence-specific bias is limited to primarily two consecutive base pairs, and the preferred sequences can be found in nearly all short DNA segments. A more realistic concern is that linker histones, chaperones and remodeling agents may block interactions between the DNA and MNase, leading to incomplete digestion [44]. Hence too low or too high MNase concentrations lead to overly wide or overly narrow peaks in the density profiles of the ChIP-DNA or MNase-DNA sequencing tags [9]. Fortunately, that does not affect comparisons between experiments using similar MNase concentrations or comparisons of regions within one experiment.

The effects of limited nuclease accessibility, incomplete cleavage and bias

One could argue that crowding with other nucleosomes or nonhistone proteins could limit the accessibility of DNA for MNase digestion and that the observed wide peaks were only artifacts of crowding. Let us examine this argument using in vitro nucleosome reconstitutions and well-separated nucleosomes.

Nucleosome peaks span wide even when accessibility is not limited by nonhistone proteins

In vitro reconstituted nucleosomes have not been associated with or positioned by nonhistone proteins. Our algorithm called peaks in the extremely high-density tag profiles of the sheep β-lactoglobulin gene [13], [14], [27] and in yeast [2]. In the experiments with short Illumina tags, the average nucleosome peak extended to 174±39 bp and a quarter of peaks spanned wider than 190 bp. The long tags in the Roche/454 experiments resulted in even more extended peaks (Figure 6, Table 1). These extended peaks cannot be due to crowding or other effects of nonhistone proteins.

Reduced accessibility due to nucleosome crowding

One could also argue that typically short linker regions between H2A nucleosomes (38±55 bp) limit nuclease access to DNA and the resulting incomplete digestion creates artificially extended peaks. One could also argue that H2A.Z peaks are digested short because their long linker regions (88±247 bp) allow more access for digestion than the short linkers for H2A nucleosomes. To evaluate these arguments, we selected such H2A nucleosomes that are separated by long linkers (88 bp or more) on both sides and that, unless protected by nonhistone proteins, are accessible to MNase digestion. Because these accessible H2A nucleosomes still extend to as wide as 170±54 bp, at practical MNase concentrations, crowding with histones or other DNA-bound proteins are not likely to have major effects for extended peaks. Lowering MNase concentration from 10 µM/L to 2 µM/L did increase the length of core DNA segments both in yeast [9] and in Caenorhabditis elegans [45]. In the latter, decreasing the temperature also produced longer DNA segments but Johnson et al. [45] estimated that at room temperature and practical MNase levels under- and overdigestion ranges to as low as a few base pairs.

As a final test, we benchmarked the reproducibility of those nucleosomes that contained the H2A.Z variant subunits [46], and were mapped using selective antibodies [7]. We selected all the 297 peaks with high average tag densities (≥20x) so as to reduce the effect of limited H2A.Z specificity of the antibodies. These peaks are practically as wide (median: 149 bp) as the single-core footprint both in vivo and in nonlinked experiments (Figure 6). Many of them guard promoter regions against nucleosome invasion [8], [47] because they are firmly anchored to the DNA either by intrinsic histone-DNA affinity or by chaperones. Indeed, a total of 225–258 peaks overlapped with peaks in 21 high-coverage experiments (Table S1). Somewhat fewer (190) overlaps were found with the template-filtered peaks of the RNA-Pol II mutant after 120 minutes following induction [9].

We observed a reproducibility of 13.5 bp being defined as the median positional difference between known H2A.Z peaks and overlapping peaks in all other in vivo experiments. Consequently, peaks wider than 161 bp are highly likely to represent dynamic nucleosomes. Because this 13.5-bp reproducibility is acceptable but not negligible, we tested the contribution of nonhistone proteins to the location of H2A.Z-overlapping peaks by comparing in vivo and nonlinked nucleosomes. The latter are more reproducible (7.5 bp) but nucleosomes in vitro reconstitute into more fuzzy positions. The 6-bp difference from in vivo and nonlinked experiments is highly significant (p<10−300, WMW test) and shows a major role for chaperones [48] in positioning H2A.Z nucleosomes, which is confirmed by the in vitro reconstitutions in the presence of ACF1 and Nap1 [2]. We estimate that the total average inaccuracy caused by incomplete or biased cleavage, amplification bias and the bona fide mobility of H2A.Z nucleosomes is as low as ∼7.5 bp. Cleavage, amplification bias and limited DNA accessibility for MNase digestion combined are not the primary determinant of the extended peaks. Instead, we hypothesize that the extended peaks are primarily due to statistical (re)positioning [24], [25] or sliding [49] of nucleosomes. This hypothesis is supported by the significantly wider peaks found at the centers of highly transcribed genes compared to at either terminus or at intergenic regions.

Remodeling stops at gene boundaries

Preserving regional differences in nucleosome occupancy and dynamism would not be possible without agents that arrest the progression of remodeling. These agents include nucleosome-excluding sequences on the DNA, histones or other DNA-associated proteins. Another reason for the spatial limits to nucleosome remodeling is the arrest and detachment of the transcriptional machinery at the 3′ termini of genes. The third reason for spatial limitations relates to effects of nucleosome presence and mobility to gene regulation [21]. To prevent regulating untargeted neighboring genes, remodeling events need to be contained within the limits of the target gene. The earlier proposed “barrier” nucleosomes guard only promoter regions against invasions of dynamic nucleosomes [8], [47]. We also found barrier nucleosomes within and downstream of the coding sequences. These well-positioned nucleosomes are reproducible across all the thirteen high-density in vivo Illumina experiments with random priming in 58% of the genes (Figures 3– 5 and S1, S2, S3, S4, S5). Across seven or more experiments, 85% of genes contained at least one well-positioned nucleosome (Table S1). Across the entire yeast genome, almost every 2000-bp segment with two or more dynamic nucleosomes also contains at least one well-positioned nucleosome, whether removable or permanent. As few as 288 segments lacked well-positioned nucleosomes in each of Kaplan et al.'s [1] thirteen Illumina experiments. Several of these are nucleosomes are frequently evicted as shown by the low density of their peaks (only ∼2.5 times higher than at the linker regions). Arrays of well-positioned nucleosomes may arrest nucleosome remodeling at gene boundaries and hence prevent accessibility regulation of neighboring genes.

Discussion

We offer partial reconciliation for the controversy between two claims: “… DNA-encoded nucleosome organization…” and “intrinsic histone-DNA interactions are not the major determinant of nucleosome positions in vivo.” Note that Kaplan et al.'s observed high correlation between in vivo and in vitro positions does not necessarily indicate well-positioned nucleosomes: two maps with similarly fuzzy remodeling patterns (dynamism) also produce high correlation. Indeed, most nucleosomes are dynamic even in Kaplan et al.'s in vitro reconstitutions where the 0.4∶1 histone∶DNA ratio allowed that histones occupy only the most affine and hence least dynamic positions. Dynamism is even more prevalent in Zhang et al.'s experiments with nonlimiting histone∶DNA ratios (Table 1, Figures 1– 3, S1, S2, S3, S4, S5). This dynamism manifests at the level of individual H2A nucleosomes, the transcriptional apparatus, chaperones and remodeling enzymes cause inaccurate reconstitution or sliding. At the level of GGRs, however, histone-DNA affinities appear to be the primary determinant of nucleosome occupancy. Both the dynamism of individual nucleosomes and the GGR-level affinities are highly related to transcription. Nucleosomes, like transcription, are influenced by both DNA-specific features like the location of exons, promoters and temporal features like the momentary location and state of the transcriptional apparatus and regulatory events.

The dynamism of individual H2A nucleosomes is indicated by extended and low peaks both in vivo and in vitro. At gene centers, peaks shrink significantly lower than at other regions. Low but wide peaks indicate fuzzy reconstitution of nucleosomes evicted by the transcriptional apparatus. These peaks also spanned significantly wider in the mid-third of genes than in introns, regulatory regions, replication origins that are known to be AT-rich and therefore less likely to coordinate nucleosomes [30], and the rest of the genome (Figures 4– 7, S1, S2, S3, S4, S5). Reconstitution is particularly inaccurate at highly expressed genes (Figures 2 and 8). This is in accord with earlier observed removal of at least one H2A/H2B dimer by the chromatin transcription-enabling activity (CTEA) complex [CTEA], [ 15], [18,29] to allow Pol II passage and the fast reconstitution of nucleosomes by CTEA and the FACT histone chaperone shortly after Pol II passage [29], [50]. The observed extended nucleosome peaks are primarily due to bona fide biological dynamism, which exceeds the combined bias of limited DNA accessibility, incomplete MNase cleavage, and amplification. Among others, this is shown by variant H2A.Z nucleosomes, which, in contrast to H2A nucleosomes, form narrow and highly reproducible peaks. Regional patterns of transcription-specific dynamism are also highly reproducible.

Nucleosome occupancy and dynamism are lower at the first and last thirds of genes than at the center, both in vivo and in reconstitution experiments. The high histone-DNA affinity of these regions may have evolved to facilitate Pol II pausing, deceleration or delay recovery from pauses, as shown by dual-trap optical tweezer assay experiments [16].

Most H2A peaks extend almost as wide in nonlinked experiments than in vivo (Table 1). In the absence of chaperones and remodeling enzymes, nucleosomes move more freely from one local affinity maximum to another, although these movements are not assisted by remodeling enzymes [1], [6], [51]. The most likely mechanism for nucleosome dynamism is ATP-independent histone sliding [52], which intensifies at higher temperatures [53]. Peaks of H2A.Z nucleosomes, however, are constrained to a median width equal to the single octamer footprint in vivo, in nonlinked and reconstitution experiments as well. This stability and the high positional reproducibility across experiments suggest that many H2A.Z nucleosomes are localized primarily at tall and locally unique maxima of histone-DNA affinity [2]. Note that a low-affinity maximum surrounded by two nucleosome-exclusion regions would also produce a well-positioned nucleosome. Alternatively, chaperones like CZF1 [48] may also anchor nucleosomes to specific loci. Long nucleosome-exclusion regions such as promoters allow binding of numerous regulatory proteins and protect from the invasion of other nucleosomes. Most peaks of barrier nucleosomes rise far above those of dynamic nucleosomes. This indicates that such barrier nucleosomes are more resistant to eviction than H2A nucleosomes and hence are preserved in most cells at almost identical genomic loci, regardless of cellular and environmental conditions. The positioning of H2A.Z nucleosomes is highly reproducible with the sole exception of ACF1-assisted reconstitution (Figure 3). These peaks are confined to the size of the single-octamer footprint with a variation of ∼9 bp, which may partly be due to experimental error.

We generalize the barrier hypothesis, which until now, was limited to H2A.Z nucleosomes [8], [47]. Nucleosome movements are limited, and in vivo, very few nucleosomes reposition in a range wider than ∼195 bp. This and the more or less well-defined peaks separated by troughs indicate that the probability of repositioning to new loci drops at some distance from the center. Occasionally, nucleosomes can invade each other's range, but this may require considerable momentum [54]. Surprisingly, remodeling events extended further than 2,000 bp in as few as 288 cases. On this basis, we postulate that long chains of remodeling events may be prevented by compounding energetic costs that contain remodeling within gene boundaries. This containment may prevent nucleosome invasions that would change the accessibility of untargeted genes. Relatively well-positioned nucleosomes may be responsible for Pol II pausing [15], [29]. Remodeling can be weakened, halted or arrested even by a series of dynamic and eviction-prone nucleosomes not necessarily containing the H2A.Z variant. Each nucleosome and possibly certain nonhistone proteins can absorb some sliding and remodeling momentum [36], depending upon the affinity of the histone octamer to the DNA segment and upon crowding with other nucleosomes and chromatin proteins. Individual nucleosomes can frequently be depositioned, but the remaining nucleosomes can still extinguish the momentum of remodeling before invading untargeted regulatory regions. This protection mechanism requires a lower but still considerable nucleosome presence at intergenic regions as well.

We conclude that dense arrays of weakly positioned nucleosomes appear to be necessary for transcription. The majority of canonical H2A nucleosomes repositions or slides to somewhat different genomic loci. Such nucleosome remodeling follows DNA-influenced, gene-wise patterns and is most intense at the centers of intensively transcribed genes. The weakness of positioning is partly due to either low or nonunique local maxima of intrinsic histone-DNA affinities, and its function is to give way to transcription, chaperones, and remodeling enzymes. Oscillations are centered at fixed positions, and their magnitude and frequency may reflect transcription or regulatory protein binding. Remodeling does not transgress to neighboring genes and may be weakened and ultimately arrested by a series of moderately or well-positioned nucleosomes, chaperones, or possibly by the lack of histone modifications. This combination of DNA- and protein-influenced positioning fine-tunes the accessibility of genomic regions and their competence for regulatory protein binding and transcription, affecting Pol II speed and the extent of its pausing.

Methods

We mapped each sequencing tag to the S. cerevisiae genome's 2006 release [55] using the bowtie tool [56], [57]. Tags matching to multiple genomic loci were discarded. We also eliminated short Illumina reads with more than two mismatches to the genome and long Roche/454 tags with more than 2 percent mismatch. To minimize bias, we have not extended or trimmed the sequencing tags. We calculated the tag density of a genomic position as the number of tags that cover the position. Tag density profiles were calculated for each experiment/replicate for the entire genome.

To allow genome-wide comparisons, we created a consistent prediction algorithm and tools to call nucleosome peaks from ChIP-Seq tags (Figures 3– 6 and S1, S2, S3, S4, S5). This consistency is a condition for minimally biased comparisons involving histone variants and GGRs. Methods designed for transcription factor binding sites [e.g., 58] are not applicable because nucleosome peaks vary in width and their sequences are not conserved. Nucleosome peaks are also diverse in height and shape. The ideal 147-bp wide rectangle is rather an exception than the rule. Instead of sharp vertical drops, observed peaks may terminate in gradual slopes (Figures 3 and S1, S2, S3, S4, S5). These valuable signals are compromised by smoothing procedures such as wavelets or loess [7], [37].

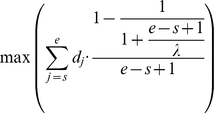

We created a peak calling algorithm for experiments with random priming with short or long sequencing tags and/or nucleosome-long sequencing tags. First, each chromosomal segment bordered by either the end of a chromosome or by nucleosome-free region(s) into such subsegments that may contain at most one full, possibly extended nucleosome peak. For each subsegment, we identify a set of candidate start positions p and end positions q, for which the subsegment cannot be divided into additional peaks: 1≤p1<q1<p2<q2,…,<pn<qn. Peaks with deep internal troughs are eliminated as follows. Any peak with a triplet of positions x, y, and z satisfying pi≤x<y<z≤qi with a deep trough y in a density d of sequencing tags

is eliminated. Here α is the maximal allowed fractional drop in density inside a peak (by default, α is set to 0.25). We optimize the widths (the start and end positions) of peaks that pass this filter by maximizing the objective function below. To prevent overextending the peaks, the cumulative tag density is assigned decreasing weight as the width increases:

|

Here s and e denote the start and the end positions of the peak (pi≤s<e≤qi), respectively. Broad peaks are slightly penalized by the parameter λ. By setting λ to 147 bp, we promote conservative width estimates while still allowing peaks to grow or shrink to any size. Experimenting with several combinations for α and λ, we found that values of 0.25≤α≤0.28 and 146≤λ≤149 accounted for the peak calls with the visually highest quality. As a further quality assurance, we eliminate potential di- and multi-nucleosomes (widths exceeding 300 bp) and peaks with extreme asymmetry or low density.

Due to premature detachment of the reverse transcriptase from the ChIP-DNA, nucleosome calls are most accurate in experiments that use random priming (on any sequencing platform) and/or nucleosome-long reads (on the Roche/454 platform) [1], [6], [7], [8], [14]. Experiments with both end-priming and short reads [9], [32] produce dual peaks (one upstream and one downstream) on the two DNA strands. Detachment becomes increasingly likely as the enzyme progresses towards the 3′ end [42]. Calling the width of dual peaks may be biased by the use of peak shape templates [9].

The consistently predicted peak widths serve as a single-valued, practical measure for the comparative analyses of nucleosome dynamics. Standardized nucleosome occupancy roughly indicates the proportion of cells that harbor nucleosomes at a genomic locus. Peaks with high amplification bias or extremely high density are excluded from the analyses. Yeast nucleosome peak calls are interactively displayed at our web-server: http://chromatin.unl.edu/cgi-bin/skyline.cgi.

None of the statistical distributions analyzed were normal as shown by the Lilliefors test. We applied the two-sample Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney (WMW) test in all statistical comparisons.

Supporting Information

All nucleosomes are dynamic at the constitutively expressed MED2 (YDL005C) gene.In particular, the single nucleosome at relative position −40 and the twin peaks starting at relative position ∼450 are subject to extreme sliding or remodeling. The MED2 protein is a subunit of the RNA polymerase II mediator complex, and it is essential for transcriptional regulation.

(0.95 MB TIF)

Extensive sliding/remodeling at the SMC5 (YOL034W) gene. SMC5 encodes a protein responsible for the structural maintenance of chromosomes, required for growth and DNA repair. Note that in most unlinked experiments, peaks are absent from region 300–1200 and 1700–2500. This suggests that the nucleosomes anchored by formaldehyde cross-linking to their in vivo loci are positioned by chaperones or remodeling enzymes.

(1.21 MB TIF)

Extensive sliding/remodeling at the SMC5 (YOL034W) gene. SMC5 encodes a protein responsible for the structural maintenance of chromosomes, required for growth and DNA repair. Note that in most unlinked experiments, peaks are absent from region 300–1200 and 1700–2500. This suggests that the nucleosomes anchored by formaldehyde cross-linking to their in vivo loci are positioned by chaperones or remodeling enzymes.

(1.03 MB TIF)

The gene for the SRO77 protein with roles in exocytosis and cation homeostasis. Note the flat distribution of sequencing tag density at the center of the gene. Although clear summits are formed, most peaks are not separated from each other in the cross-linked experiments and in ACF1 reconstitutions.

(1.25 MB TIF)

Nucleosome reconstitutions from the purified DNA of the ovine beta-lactoglobulin gene and chicken erythrocyte histones (Fraser et al., 2009). These extremely high coverage experiments indicate fuzzy nucleosome positioning even in the absence of remodeling enzymes and histone chaperones.

(3.54 MB TIF)

The presence of well-positioned (barrier) nucleosomes in the yeast genes. Experiments with well-positioned nucleosomes are shown for each gene. Most genes (including their flanking intergenic regions) contain one or more well-positioned nucleosome(s) in the majority if not all of the 13 Illumina experiments. Off-target transcriptional regulation is reduced by within-transcribed region “absorbers” of the momentum of histone sliding and remodeling. Cross-linked studies are color-coded by blue. Please refer to Figs. S1, S2, S3, S4 for graphical displays.

(2.74 MB PDF)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. D. Swanson, T. Harvill, A. Guru (University of Nebraska, Holland Computing Center), Ms. Sabina Manandhar (University of Nebraska-Lincoln), and I. Albert (Pennsylvania State Univ.). This work was completed utilizing the Holland Computing Center and the Bioinformatics Core Research Facility of the University of Nebraska.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: The study was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) grant EPS-0701892 and grants from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln to IL. Funding for the Open Access Charge was obtained by NSF grant EPS-0701892 to IL. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kaplan N, Moore IK, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Gossett AJ, Tillo D, et al. The DNA-encoded nucleosome organization of a eukaryotic genome. Nature. 2009;458:362–366. doi: 10.1038/nature07667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Moqtaderi Z, Rattner BP, Euskirchen G, Snyder M, et al. Intrinsic histone-DNA interactions are not the major determinant of nucleosome positions in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:847–852. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan N, Moore I, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Gossett AJ, Tillo D, et al. Nucleosome sequence preferences influence in vivo nucleosome organization. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:918–920; author reply 920–912. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0810-918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Moqtaderi Z, Rattner BP, Euskirchen G, Snyder M, et al. Evidence against a genomic code for nucleosome positioning. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:920–923. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0810-920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pugh BF. A preoccupied position on nucleosomes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:923. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0810-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Field Y, Kaplan N, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Moore IK, Sharon E, et al. Distinct modes of regulation by chromatin encoded through nucleosome positioning signals. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albert I, Mavrich TN, Tomsho LP, Qi J, Zanton SJ, et al. Translational and rotational settings of H2A.Z nucleosomes across the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature. 2007;446:572–576. doi: 10.1038/nature05632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mavrich TN, Ioshikhes IP, Venters BJ, Jiang C, Tomsho LP, et al. A barrier nucleosome model for statistical positioning of nucleosomes throughout the yeast genome. Genome Res. 2008;18:1073–1083. doi: 10.1101/gr.078261.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiner A, Hughes A, Yassour M, Rando OJ, Friedman N. High-resolution nucleosome mapping reveals transcription-dependent promoter packaging. Genome Res. 2010;20:90–100. doi: 10.1101/gr.098509.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barski A, Zhao K. Genomic location analysis by ChIP-Seq. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107:11–18. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park YJ, Luger K. Histone chaperones in nucleosome eviction and histone exchange. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clapier CR, Cairns BR. The biology of chromatin remodeling complexes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:273–304. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.062706.153223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gencheva M, Boa S, Fraser R, Simmen MW, Whitelaw CBA, et al. In Vitro and in Vivo nucleosome positioning on the ovine beta-lactoglobulin gene are related. J Mol Biol. 2006;361:216–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraser RM, Keszenman-Pereyra D, Simmen MW, Allan J. High-resolution mapping of sequence-directed nucleosome positioning on genomic DNA. J Mol Biol. 2009;390:292–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Studitsky VM, Walter W, Kireeva M, Kashlev M, Felsenfeld G. Chromatin remodeling by RNA polymerases. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2004;29:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hodges C, Bintu L, Lubkowska L, Kashlev M, Bustamante C. Nucleosomal fluctuations govern the transcription dynamics of RNA polymerase II. Science. 2009;325:626–628. doi: 10.1126/science.1172926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell. 2007;128:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kireeva ML, Walter W, Tchernajenko V, Bondarenko V, Kashlev M, et al. Nucleosome remodeling induced by RNA polymerase II: loss of the H2A/H2B dimer during transcription. Mol Cell. 2002;9:541–552. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00472-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwabish MA, Struhl K. The Swi/Snf complex is important for histone eviction during transcriptional activation and RNA polymerase II elongation in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6987–6995. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00717-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwabish MA, Struhl K. Asf1 mediates histone eviction and deposition during elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell. 2006;22:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwabish MA, Struhl K. Evidence for eviction and rapid deposition of histones upon transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10111–10117. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.23.10111-10117.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith CL, Peterson CL. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2005;65:115–148. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(04)65004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Partensky PD, Narlikar GJ. Chromatin remodelers act globally, sequence positions nucleosomes locally. J Mol Biol. 2009;391:12–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.04.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kornberg RD, Stryer L. Statistical distributions of nucleosomes: nonrandom locations by a stochastic mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:6677–6690. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.14.6677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boeger H, Griesenbeck J, Kornberg RD. Nucleosome retention and the stochastic nature of promoter chromatin remodeling for transcription. Cell. 2008;133:716–726. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richmond TJ, Davey CA. The structure of DNA in the nucleosome core. Nature. 2003;423:145–150. doi: 10.1038/nature01595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fraser RM, Allan J, Simmen MW. In Silico Approaches Reveal the Potential for DNA Sequence-dependent Histone Octamer Affinity to Influence Chromatin Structure in Vivo. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:582–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dohm JC, Lottaz C, Borodina T, Himmelbauer H. Substantial biases in ultra-short read data sets from high-throughput DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e105. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kireeva ML, Hancock B, Cremona GH, Walter W, Studitsky VM, et al. Nature of the nucleosomal barrier to RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell. 2005;18:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iyer V, Struhl K. Poly(dA:dT), a ubiquitous promoter element that stimulates transcription via its intrinsic DNA structure. Embo J. 1995;14:2570–2579. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yin S, Deng W, Hu L, Kong X. The impact of nucleosome positioning on the organization of replication origins in eukaryotes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385:363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shivaswamy S, Bhinge A, Zhao Y, Jones S, Hirst M, et al. Dynamic remodeling of individual nucleosomes across a eukaryotic genome in response to transcriptional perturbation. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e65. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee C-K, Shibata Y, Rao B, Strahl BD, Lieb JD. Evidence for nucleosome depletion at active regulatory regions genome-wide. Nat Genet. 2004;36:900–905. doi: 10.1038/ng1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hesselberth JR, Chen X, Zhang Z, Sabo PJ, Sandstrom R, et al. Global mapping of protein-DNA interactions in vivo by digital genomic footprinting. Nat Methods. 2009;6:283–289. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fedor MJ, Lue NF, Kornberg RD. Statistical positioning of nucleosomes by specific protein-binding to an upstream activating sequence in yeast. J Mol Biol. 1988;204:109–127. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kornberg RD, Lorch Y. Irresistible force meets immovable object: transcription and the nucleosome. Cell. 1991;67:833–836. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan G-C, Liu Y-J, Dion MF, Slack MD, Wu LF, et al. Genome-scale identification of nucleosome positions in S. cerevisiae. Science. 2005;309:626–630. doi: 10.1126/science.1112178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X, Mann CJ, Bai Y, Ni L, Weiner H. Molecular Cloning, Characterization, and Potential Roles of Cytosolic and Mitochondrial Aldehyde Dehydrogenases in Ethanol Metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:822–830. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.822-830.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siepel A, Bejerano G, Pedersen JS, Hinrichs AS, Hou M, et al. Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes. Genome Research. 2005;15:1034–1050. doi: 10.1101/gr.3715005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yassour M, Kaplan T, Fraser HB, Levin JZ, Pfiffner J, et al. Ab initio construction of a eukaryotic transcriptome by massively parallel mRNA sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3264–3269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812841106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hughes TR, Marton MJ, Jones AR, Roberts CJ, Stoughton R, et al. Functional discovery via a compendium of expression profiles. Cell. 2000;102:109–126. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pepke S, Wold B, Mortazavi A. Computation for ChIP-seq and RNA-seq studies. Nat Methods. 2009;6:S22–32. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horz W, Altenburger W. Sequence specific cleavage of DNA by micrococcal nuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:2643–2658. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.12.2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson SM, Tan FJ, McCullough HL, Riordan DP, Fire AZ. Flexibility and constraint in the nucleosome core landscape of Caenorhabditis elegans chromatin. Genome Res. 2006;16:1505–1516. doi: 10.1101/gr.5560806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suto RK, Clarkson MJ, Tremethick DJ, Luger K. Crystal structure of a nucleosome core particle containing the variant histone H2A.Z. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:1121–1124. doi: 10.1038/81971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bondarenko VA, Steele LM, Ujvari A, Gaykalova DA, Kulaeva OI, et al. Nucleosomes can form a polar barrier to transcript elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell. 2006;24:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luk E, Vu ND, Patteson K, Mizuguchi G, Wu WH, et al. Chz1, a nuclear chaperone for histone H2AZ. Mol Cell. 2007;25:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Becker PB. Nucleosome sliding: facts and fiction. EMBO J. 2002;21:4749–4753. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kulish D, Struhl K. TFIIS enhances transcriptional elongation through an artificial arrest site in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4162–4168. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4162-4168.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Segal E, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Chen L, Thastrom A, Field Y, et al. A genomic code for nucleosome positioning. Nature. 2006;442:772–778. doi: 10.1038/nature04979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bowman GD. Mechanisms of ATP-dependent nucleosome sliding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;20:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meersseman G, Pennings S, Bradbury EM. Mobile nucleosomes–a general behavior. Embo J. 1992;11:2951–2959. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Engeholm M, de Jager M, Flaus A, Brenk R, van Noort J, et al. Nucleosomes can invade DNA territories occupied by their neighbors. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:151–158. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hinrichs AS, Karolchik D, Baertsch R, Barber GP, Bejerano G, et al. The UCSC Genome Browser Database: update 2006. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:D590–598. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Campbell PJ, Stephens PJ, Pleasance ED, O'Meara S, Li H, et al. Bowtie: An ultrafast memory-efficient short read aligner. Identification of somatically acquired rearrangements in cancer using genome-wide massively parallel paired-end sequencing. Nat Genet. 2008;40:722–729. doi: 10.1038/ng.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg S. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biology. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fejes AP, Robertson G, Bilenky M, Varhol R, Bainbridge M, et al. FindPeaks 3.1: a tool for identifying areas of enrichment from massively parallel short-read sequencing technology. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1729–1730. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

All nucleosomes are dynamic at the constitutively expressed MED2 (YDL005C) gene.In particular, the single nucleosome at relative position −40 and the twin peaks starting at relative position ∼450 are subject to extreme sliding or remodeling. The MED2 protein is a subunit of the RNA polymerase II mediator complex, and it is essential for transcriptional regulation.

(0.95 MB TIF)

Extensive sliding/remodeling at the SMC5 (YOL034W) gene. SMC5 encodes a protein responsible for the structural maintenance of chromosomes, required for growth and DNA repair. Note that in most unlinked experiments, peaks are absent from region 300–1200 and 1700–2500. This suggests that the nucleosomes anchored by formaldehyde cross-linking to their in vivo loci are positioned by chaperones or remodeling enzymes.

(1.21 MB TIF)

Extensive sliding/remodeling at the SMC5 (YOL034W) gene. SMC5 encodes a protein responsible for the structural maintenance of chromosomes, required for growth and DNA repair. Note that in most unlinked experiments, peaks are absent from region 300–1200 and 1700–2500. This suggests that the nucleosomes anchored by formaldehyde cross-linking to their in vivo loci are positioned by chaperones or remodeling enzymes.

(1.03 MB TIF)

The gene for the SRO77 protein with roles in exocytosis and cation homeostasis. Note the flat distribution of sequencing tag density at the center of the gene. Although clear summits are formed, most peaks are not separated from each other in the cross-linked experiments and in ACF1 reconstitutions.

(1.25 MB TIF)

Nucleosome reconstitutions from the purified DNA of the ovine beta-lactoglobulin gene and chicken erythrocyte histones (Fraser et al., 2009). These extremely high coverage experiments indicate fuzzy nucleosome positioning even in the absence of remodeling enzymes and histone chaperones.

(3.54 MB TIF)

The presence of well-positioned (barrier) nucleosomes in the yeast genes. Experiments with well-positioned nucleosomes are shown for each gene. Most genes (including their flanking intergenic regions) contain one or more well-positioned nucleosome(s) in the majority if not all of the 13 Illumina experiments. Off-target transcriptional regulation is reduced by within-transcribed region “absorbers” of the momentum of histone sliding and remodeling. Cross-linked studies are color-coded by blue. Please refer to Figs. S1, S2, S3, S4 for graphical displays.

(2.74 MB PDF)