Abstract

Protein misfolding with loss-of-function of the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) is the molecular basis of phenylketonuria in many individuals carrying missense mutations in the PAH gene. PAH is complexly regulated by its substrate l-Phenylalanine and its natural cofactor 6R-l-erythro-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). Sapropterin dihydrochloride, the synthetic form of BH4, was recently approved as the first pharmacological chaperone to correct the loss-of-function phenotype. However, current knowledge about enzyme function and regulation in the therapeutic setting is scarce. This illustrates the need for comprehensive analyses of steady state kinetics and allostery beyond single residual enzyme activity determinations to retrace the structural impact of missense mutations on the phenylalanine hydroxylating system. Current standard PAH activity assays are either indirect (NADH) or discontinuous due to substrate and product separation before detection. We developed an automated fluorescence-based continuous real-time PAH activity assay that proved to be faster and more efficient but as precise and accurate as standard methods. Wild-type PAH kinetic analyses using the new assay revealed cooperativity of activated PAH toward BH4, a previously unknown finding. Analyses of structurally preactivated variants substantiated BH4-dependent cooperativity of the activated enzyme that does not rely on the presence of l-Phenylalanine but is determined by activating conformational rearrangements. These findings may have implications for an individualized therapy, as they support the hypothesis that the patient's metabolic state has a more significant effect on the interplay of the drug and the conformation and function of the target protein than currently appreciated.

Keywords: Allosteric Regulation, Cooperativity, Enzyme Kinetics, Protein Conformation, Protein Drug Interactions, Phenylalanine Hydroxylase, Phenylketonuria, Protein Misfolding, Tetrahydrobiopterin

Introduction

Phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH4; EC 1.14.16.1) is a non-heme iron monoxygenase that catalyzes the hydroxylation of the substrate l-Phe to l-Tyr in the presence of its natural cofactor 6R-l-erythro-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) and molecular dioxygen. Mutations in the PAH gene can lead to protein misfolding with loss of function and subsequently to phenylketonuria ([MIM 261600]), the most common inborn error of amino acid metabolism in European-descended populations (1, 2). Pharmacological doses of BH4 can correct protein misfolding in a significant number of patients with PAH deficiency, and sapropterin dihydrochloride, the synthetic form of the natural PAH cofactor, was recently approved as the first pharmacological chaperone to treat phenylketonuria patients (3–5).

The enzyme is a homotetramer built as a dimer of dimers with each subunit consisting of an N-terminal regulatory domain (residues 1–142), a catalytic domain (residues 143–410), and a C-terminal oligomerization domain (residues 411–452). Elaborate functional and kinetic studies have revealed complex enzyme regulation by its substrate and cofactor as well as by phosphorylation (6–8). Binding of the substrate induces a catalytically competent (activated) enzyme, whereas binding of BH4 leads to formation of an inactive dead-end PAH-BH4 complex (9–12). These regulatory mechanisms require reversible conformational changes that are transmitted throughout the enzyme upon binding of BH4 and l-Phe (13). Structural analyses of BH4 binding revealed that the cofactor interacts with the N-terminal autoregulatory sequence and the pterin binding loop, leading to stabilizing hydrogen bonds and to formation of a binary enzyme-BH4 complex (14). The largest conformational changes were observed upon binding of l-Phe, where local changes at the active site are propagated globally through hinge-bending motions in the catalytic domain, also altering the position and orientation of bound BH4 (13, 15) and of the regulatory domain (16).

Analyses of the effects of missense mutations in the PAH gene on PAH enzyme kinetic properties have shown that residual enzyme activity generally is high, yet allostery is often disturbed (17–19), with reduced cooperativity for substrate binding, decreased substrate activation, or altered affinity to the substrate and the cofactor. Thus, the evaluation of kinetics and allostery can help to assess to which extent local single amino acid replacements lead to global conformational alterations compromising enzyme function. In this context, comprehensive steady state kinetic analyses beyond single determination of residual enzyme activity are needed to retrace the structural impact of missense mutations on the phenylalanine hydroxylating system. Yet, the current standard activity assays requiring substrate and product separation before l-Tyr detection by radioactivity or fluorescence signals (20–22) are laborious and time consuming. In addition, designed as end-point measurements, these discontinuous assays assume a linear range of activity for the time period chosen, although variations of temperature and pH as well as concentrations of enzyme, substrate, and cofactor can dramatically change the linearity of a reaction over the fixed time window (23). Therefore, we aimed to develop an automated continuous real-time assay of PAH activity. Our new fluorescence-based multi-well assay has given rise to the possibility of evaluating PAH kinetics and allostery faster and more efficiently but as precisely and accurately as the standard methods. Surprisingly, by application of this technique, the data obtained for BH4-dependent PAH kinetics did not fit to the well accepted model of a single hyperbolic function (Michaelis-Menten kinetic model). Instead, a good fit was found using a sigmoidal binding curve (Hill kinetic model). Although positive cooperativity for the binding of l-Phe has been extensively studied (24, 25), cooperativity toward BH4 has not been described to date. However, cofactor-dependent kinetic studies were routinely performed using the non-activated PAH enzyme (19, 26), whereas an l-Phe preincubated (activated) enzyme was applied in our experiments.

Thus, we aimed to characterize BH4-dependent PAH kinetics in more detail and to investigate whether activation of PAH is a prerequisite for the positive cooperativity observed. Real-time fluorescence kinetic analyses using l-Phe-activated and non-activated PAH were performed. Furthermore, genetic variants of PAH, which are structurally preactivated by single amino acid replacements, were analyzed. To discriminate between non-cooperative and cooperative enzyme kinetics, in-depth model comparisons by nonlinear regression analysis were conducted with fitting of the data to the Michaelis-Menten or the Hill kinetic model.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression and Purification of Recombinant PAH Enzymes

The cDNA of human phenylalanine hydroxylase (EST clone obtained from Imagines, formerly RZPD, Germany) was cloned into the pMAL-c2E and pMAL-c2X expression vectors (New England Biolabs) encoding an N-terminal maltose-binding protein (MBP) tag and enterokinase or Factor Xa cleavage sites, respectively. PAH mutants were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis as described (17). Escherichia coli DH5α were transformed with the expression vector for wild-type and mutant MBP-PAH fusion proteins. Proteins were purified by affinity chromatography (MBP Trap, GE Healthcare) followed by size-exclusion chromatography using a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) on an ÄKTAxpress system as previously described (17). The isolated tetrameric fusion proteins were collected, and protein concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically using ϵ280 (1 mg/ml) = 1.63. Tetrameric fusion protein was cleaved by factor Xa (10 units of factor Xa:1 mg of fusion protein) at 4 °C for 16 h and isolated by size-exclusion chromatography using a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 prep grade column (GE Healthcare). Protein concentrations of the cleaved tetrameric PAH were determined spectrophotometrically using ϵ280 (1 mg/ml) = 1.0.

Verifying Direct Fluorescence Detection of Enzymatic l-Tyr Production

To verify the spectral separation needed for the direct in-well fluorescence detection of enzymatic l-Tyr production, l-Tyr (0–150 μm) (Sigma) in 17 mm NaHepes, pH 7.3, was added to all wells of a 96-well plate (NUNC F96) containing a reaction mixture with 1 mg/ml catalase (Sigma), 10 μm ferrous ammonium sulfate (Fe2+) (Fluka), and l-Phe (0–1000 μm) (Sigma) yet lacking the apoenzyme and BH4. l-Tyr fluorescence intensity was subsequently measured using a fluorescence photometer (FLUOstar OPTIMA, BMG Labtech) at an excitation wavelength of 274 nm and an emission wavelength of 304 nm. Individual experiments were assayed as triplicates. All concentrations mentioned refer to a final volume of 204 μl.

Quantification of l-Tyr Production

For the quantification of l-Tyr production, standards consisting of l-Tyr (0–463 μm) and l-Phe (547 μm) in 17 mm NaHepes, pH 7.3, 1 mg/ml catalase, and 10 μm ferrous ammonium sulfate were measured before each experiment using the fluorescence photometer (excitation 274 nm, emission 304 nm). Individual experiments were assayed as triplicates before enzyme kinetic measurements on each experimental day. All concentrations mentioned refer to a final volume of 204 μl.

Analysis of the Inner Filter Effect (IFE) of BH4

A 96-well plate was prepared with l-Tyr (0–150 μm) in 17 mm NaHepes, pH 7.3, and a standard reaction mixture containing the standard concentration of 1 mm l-Phe in 17 mm NaHepes, pH 7.3, 1 mg/ml catalase, 10 μm ferrous ammonium sulfate, and 15 mm NaHepes, pH 7.0. Subsequent to injection of BH4 (0–125 μm) (6R-l-erythro-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin, Schircks Laboratories) stabilized in 2 mm dithiothreitol (DTT) (Fluka), l-Tyr fluorescence intensity was measured using the fluorescence photometer (excitation 274 nm, emission 304 nm). The IFE of BH4 was corrected by defining a correction factor for each BH4 concentration added to the reaction mixture: q = f (at each [BH4])/f (fluorophore alone), where f is the fluorescence intensity, and q is the correction factor for the substrate concentration (27, 28). All measurements were assayed as triplicates before enzyme kinetic measurements on each experimental day. All concentrations mentioned refer to a final volume of 204 μl.

Time-dependent Enzyme Activity Measurement

For time-dependent enzyme activity measurements, the assay was performed with and without preincubation of the enzyme with 1 mm l-Phe. A reaction buffer containing 1 mg/ml catalase, 10 μm ferrous ammonium sulfate, and the tetrameric MBP-PAH fusion protein (0.01 mg/ml) was prepared. After preincubation with 1 mm l-Phe in 22.35 mm NaHepes, pH 7.3, for 5 min at 25 °C, the reaction was initiated by the addition of 75 μm BH4 stabilized in 2 mm DTT. For enzyme activity measurements without l-Phe preincubation, the reaction was initiated by simultaneous injection of 1 mm l-Phe and 75 μm BH4.

Time-dependent substrate production was assessed by detection of the increase in l-Tyr fluorescence intensity at an excitation wavelength of 274 nm and an emission wavelength of 304 nm using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Cary Eclipse, Varian). All concentrations mentioned refer to the final concentration in a 204-μl reaction mixture.

Multiwell Enzyme Activity Assay with and without l-Phe Preactivation

For PAH activity measurement, l-Phe in 22.35 mm NaHepes, pH 7.3, was added to 12 wells of a 96-well plate with varying l-Phe concentrations (0–1000 μm) or at a constant l-Phe concentration (1 mm) using the injection system of a fluorescence photometer. A reaction buffer containing 1 mg/ml catalase, 10 μm ferrous ammonium sulfate, and the tetrameric MBP-PAH fusion protein (0.01 mg/ml) was prepared and injected in all 12 wells. After preincubation with l-Phe for 5 min at 25 °C, the reaction was initiated by the addition of BH4 stabilized in DTT for a final concentration of 75 μm BH4 with varying l-Phe concentrations (0–1000 μm) or varying BH4 concentrations (0–125 μm) at 1 l-Phe concentration (1 mm) and 2 mm DTT.

For enzyme activity measurements without l-Phe preincubation, the reaction buffer was prepared and injected to 12 wells. The reaction was initiated by simultaneous injection of varying l-Phe concentrations (0–1000 μm) and 1 BH4 concentration (75 μm) or 1 l-Phe concentration (1 mm) and varying BH4 concentrations (0–125 μm).

Steady state kinetics of PAH were determined at 25 °C and a 60-s measurement time per well. Substrate production was assessed by detection of the increase in l-Tyr fluorescence intensity at an excitation wavelength of 274 nm and an emission wavelength of 304 nm using a fluorescence photometer (FLUOstar OPTIMA, BMG Labtech) and assayed as duplicates on 3 consecutive days. Fluorescence intensity signals were corrected for the quenching effect of BH4. All concentrations mentioned refer to the final concentration in a 204 μl reaction mixture.

For all enzyme activity measurements, fluorescence intensity was recorded and, after subtraction of the blank reaction, converted to enzyme activity units (nmol Tyr/min × mg protein) using the standard curve obtained by l-Tyr concentration measurements. Data were analyzed by nonlinear regression analysis using the single hyperbolic model (Michaelis-Menten kinetic model),

|

where v is the observed rate of enzyme catalysis, Vmax is the maximum rate of enzyme catalysis, [S] is the substrate concentration, and Km is the substrate concentration at which Vmax/2 is reached and the sigmoidal kinetic model (Hill kinetic model),

|

where v is the observed rate of enzyme catalysis, Vmax is the maximum rate of enzyme catalysis, [S] is the substrate concentration, EC50 is the substrate concentration at which Vmax/2 is reached, and h is the Hill coefficient (GraphPad Prism 4.0c). Values are given as the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. The coefficient of variation was determined as the ratio of the S.D. to the mean value. Comparison of model fitting was performed using the F-test (GraphPad Prism QuickCal), residuals of values, the S.D. of the residuals (Sy.x), the runs test, and the square of residuals (R2) (see supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Fig. S2) (29–34).

Tryptophan Fluorescence Measurements

For tryptophan fluorescence emission scans, wild-type PAH, dimeric PAH 103–427, and variant PAH R68S were diluted to 11 μm subunits PAH (0.6 μg/μl) in 20 mm NaHepes and 200 mm NaCl, pH 7.0, containing 10 μm ferrous ammonium sulfate and 2 mm DTT. Fluorescence measurements were performed using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Cary Eclipse, Varian) at an excitation wavelength of 295 nm with excitation and emission slits set to 2.5 and 5 nm, respectively.

Differential Scanning Fluorimetry

Differential scanning fluorimetry analyses were performed on a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer equipped with a temperature-controlled Peltier multicell holder (Varian). Denaturation of 6 μm MBP-PAH subunits diluted in 20 mm NaHepes and 200 mm NaCl, pH 7.0, containing 2 mm DTT was performed by scanning a temperature range of 25 to 70 °C at a rate of 1.2 °C/min. In the cases indicated, l-Phe was added to a final concentration of 1 mm. Changes in 8-anilino-1-naphtalenesulfonic acid fluorescence emission (Sigma) were monitored at 500 nm (excitation 395 nm, slit widths 5.0/10.0 nm). The phase transitions of three to eight independent experiments were determined, and the respective transition midpoints were calculated using the Boltzmann sigmoidal equation. Transition midpoints for wild-type and variant PAH with and without l-Phe were plotted and compared using a paired t test.

RESULTS

Direct Fluorescence Detection of Enzymatic l-Tyr Production

To date measurement of PAH activity is routinely performed using a standard reaction mixture containing the apoenzyme, Fe2+, l-Phe, and BH4 followed by time-consuming chromatographic separation of substrate and product. Yet differences in the fluorescence properties of the aromatic amino acids l-Phe and l-Tyr, such as emission and excitation wavelengths as well as the quantum yield, would allow for spectral separation of these substances even in a mixed solution.

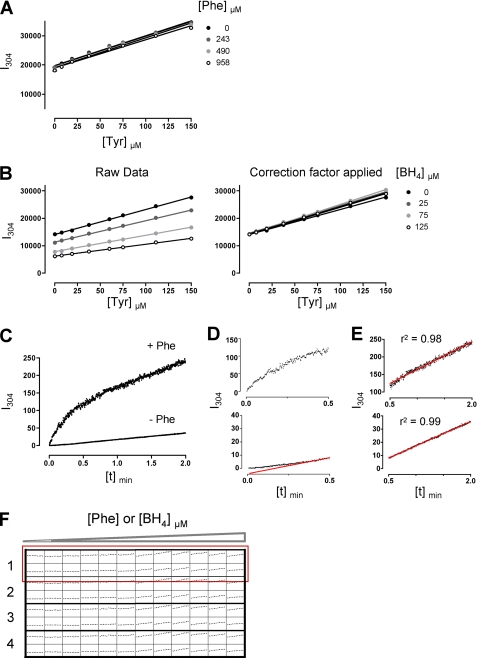

To determine spectral separation of the two substances, we assessed fluorescence signal intensities of varying l-Tyr concentrations at 304 nm (35), the l-Tyr emission wavelength, as a function of increasing l-Phe concentrations. We showed that direct in-well detection of l-Tyr was unaffected by the various l-Phe concentrations used in our assay (Fig. 1A and supplemental Fig. 1A). This was true for all l-Tyr concentrations expected in the following enzyme kinetic measurements. However, l-Tyr fluorescence signal intensities decreased with increasing BH4 concentrations (supplemental Fig. 1B), suggesting an IFE of BH4 on l-Tyr excitation and emission. Therefore, we determined specific correction factors on the basis of the factorial decrease of signal intensity for every BH4 concentration added to account for the IFE (Fig. 1B) (27, 28). Evaluation of the IFE of BH4 and calculation of the correction factor for each BH4 concentration added to the reaction mixture was performed before each enzyme kinetic measurement (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

A novel continuous assay for the measurement of PAH activity. A, fluorescence intensity (I304) of l-Tyr concentrations (0–150 μm) with increasing l-Phe concentrations (0, 243, 490, and 958 μm) is shown. l-Tyr fluorescence intensity was not influenced by increasing l-Phe concentrations, confirming spectral separation of the two substances in one mixed solution. Values are given as the mean ± S.E. of three independent measurements. B, quenching of l-Tyr fluorescence intensity by BH4 is shown. Measurement of l-Tyr (0–150 μm) subsequent to the addition of increasing BH4 concentrations (0, 25, 75, and 125 μm), revealed an inner filter effect of BH4 on l-Tyr excitation and emission (left panel). For each BH4 concentration used in the assay, a correction factor was calculated according to the factorial decrease in signal intensity to account for the inner filter effect (right panel). Values are given as the mean ± S.E. of three independent measurements. C, continuous measurement of time-dependent wild-type PAH kinetics with and without preincubation of the enzyme with 1 mm l-Phe are shown. D, l-Phe preincubation (activation) led to burst-phase kinetics within the first 30 s of the reaction (top) followed by a linear phase of l-Tyr production. Without l-Phe preincubation, an initial lag-phase before steady state enzyme kinetics was found (bottom, a red line was used to guide the eye). E, the time frame chosen for the measurement of steady state enzyme kinetics between 30 and 120 s showed a linear rate of reaction (top, with l-Phe preincubation; bottom, without l-Phe preincubation). F, a 96-well plate for sequential measurement of PAH enzyme kinetics is shown. Direct in-well measurements of enzyme kinetics of up to four different PAH enzymes (numbers 1–4) were performed by the sequential analysis of 2 rows, consisting of 24 wells (red box). Each row contained the PAH enzyme varying substrate concentrations (0–1 mm) and one cofactor concentration (75 μm) or varying cofactor concentrations (0–125 μm) and one substrate concentration (1 mm). Repeated cycles allowed kinetic measurements of 24 wells over a time period of 60 s.

The analysis of steady state enzyme kinetics using direct in-well detection of l-Tyr production revealed a time-dependent change of enzyme activity upon the addition of BH4, with an initial high activity burst phase (Fig. 1C and Fig. 1D, top) followed by a linear steady state rate of catalysis for the l-Phe preincubated (activated) enzyme (Fig. 1C and Fig. 1E, top). In contrast, the non-activated enzyme showed an initial lag-phase (Fig. 1C and Fig. 1D, bottom) before a linear phase of l-Tyr production (Fig. 1C and Fig. 1E, bottom).

In addition, time-dependent initial velocity measurements require substrate turnover to remain less than 10% that of the substrate concentrations added to the reaction mixture (23). A time frame of 60 s for measurement of steady state enzyme kinetics starting 30 s after the addition of BH4 proved to best fulfill the criteria of linearity and limited substrate turnover.

To allow for an accurate and efficient performance of the enzyme kinetic assay, liquid handling and signal detection were automated using a multi-well fluorescence detection device with an integrated injection system. Various substrate or cofactor concentrations were injected for l-Phe or BH4-dependent kinetics, respectively, and process automation enabled sequential duplicate measurements of up to four different PAH enzymes, resulting in reduced time for experimental preparation and procedure (Fig. 1F).

Thus, real-time measurement of PAH product formation revealed that direct in-well detection of l-Tyr during the catalytic reaction without prior separation of substrate and product is feasible when BH4 quenching is taken into account. In addition, real-time kinetics give more insights into both pre-steady state and steady state kinetics of phenylalanine hydroxylation, allowing thorough analysis of PAH enzyme kinetics.

A Continuous PAH Activity Assay Reveals BH4-dependent Cooperativity

The newly developed continuous assay was used to determine enzyme kinetic parameters at varying substrate concentrations (l-Phe, 1–1000 μm) and a constant cofactor concentration (BH4, 75 μm) or at varying cofactor concentrations (BH4, 0–125 μm) and a constant substrate concentration (l-Phe, 1 mm).

Measurement of l-Phe-dependent PAH kinetics showed sigmoidal behavior for the activated enzyme (Fig. 2A) as previously described (24, 36–38). Enzyme kinetic parameters were calculated by nonlinear regression analysis using the Hill equation, accounting for substrate cooperativity and compared with the results of a standard discontinuous PAH activity assay (Table 1) (17). Values for Vmax were substantially higher when determined by the continuous assay (6598 nmol Tyr/min × mg protein) as compared with the discontinuous assay (3470 nmol Tyr/min × mg protein). However, apparent affinity to the substrate (S0.5 156 μm), cooperativity (Hill coefficient, hPhe 3.0), and substrate activation (activation-fold 2.8) showed virtually identical results in both experiments (discontinuous assay; S0.5 155 μm, hPhe 3.0, activation-fold 3.0). As expected from previous studies using recombinant human PAH (26, 37) and the rat enzyme (36), enzyme kinetic parameters obtained without l-Phe preincubation gave different results (Table 1). Vmax was markedly lower (2533 nmol Tyr/min × mg protein), and the apparent affinity of the enzyme to l-Phe (Km 318 μm) was reduced. In addition, binding of l-Phe to the non-activated enzyme was found to be non-cooperative (hPhe 1.0). This is in concordance with studies using surface plasmon resonance (25). The enzyme kinetic parameters determined for both activated and non-activated PAH were well comparable with the data found in previous studies (Table 1) (17, 37).

FIGURE 2.

Measurements of wild-type PAH kinetics. A, reaction rates at variable l-Phe concentrations (0–1 mm) and one BH4 concentration (75 μm) are shown. Before initiation of the reaction by BH4, the enzyme was preincubated for 5 min at 25 °C with l-Phe to activate the enzyme. Nonlinear regression analysis was performed using the Hill equation. B and C, reaction rates at variable BH4 concentrations (0–125 μm) and one l-Phe concentration (1 mm) are shown. B, data obtained for the l-Phe preincubated (activated) enzyme were evaluated using the Michaelis-Menten equation (dashed line) and the Hill equation (solid line). C, a comparison of enzyme kinetics measured using the non-activated (●) and the activated (○) wild-type PAH is shown. The non-activated enzyme showed non-cooperative binding of BH4. The activated enzyme indicated positive cooperativity for the binding of BH4. D, enzyme kinetics of non-activated and activated PAH at variable BH4 concentrations (0–50 μm) and one l-Phe concentration (1 mm) are shown. Data obtained for the non-activated enzyme were fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation (left panel). Data of the activated enzyme followed Hill kinetics (right panel). For all enzyme activity measurements, fluorescence intensity was recorded and after subtraction of the blank reaction converted to enzyme activity units (nmol l-Tyr/min × mg protein) using the standard curve obtained by l-Tyr concentration measurements. Values are given as the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of l-Phe-dependent enzyme kinetic parameters obtained by standard PAH activity assay and direct in-well detection of l-Tyr production

Steady state kinetic parameters of WT MBP-PAH fusion protein are shown. Apparent affinities for l-Phe (S0.5, Km, and the Hill-coefficient (hPhe) as a measure of cooperativity are shown. Measurements were performed with (+) and without (−) l-Phe preincubation of the enzyme. Enzyme kinetic parameters were determined at variable l-Phe concentrations (0–1000 μm) and standard BH4 concentrations (75 μm). CV, coefficient of variation, defined as the ratio of the S.D. to the mean value.

| l-Phe preincubation | Vmax | CV | S0.5 | CV | Km | hPhe | Activation folda | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmol l-Tyr/min × mg protein | % | μm | % | μm | ||||

| WTb | − | 495c | 318c | 1.5c | — | |||

| + | 1550c | 154c | 2.2c | 3.1c | ||||

| + | 3470 ± 75d | 2 | 155 ± 6d | 4 | 3.0d | 3.0d | ||

| WTe | − | 2533 ± 217 | — | 318 ± 68 | 1.0 | — | ||

| + | 6598 ± 190 | 3 | 156 ± 9 | 6 | 3.0 | 2.8 |

a Fold increase in PAH activity by l-Phe preincubation calculated at the standard l-Phe (1 mm) and BH4 (75 μm) concentrations.

b Measurement by standard discontinuous PAH activity assay (HPLC and fluorimetric detection). Values are given as the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

c From Knappskog et al. (37); activation fold was calculated from Vmax.

d From Gersting et al. (17).

e Measurement by continuous PAH activity assay (direct in-well fluorescence detection). Values are given as the mean ± S.E. of four independent experiments.

Surprisingly, the data obtained for BH4-dependent PAH kinetics did not fit to the well accepted Michaelis-Menten kinetic model. Instead, the data showed a sigmoidal behavior, indicating BH4-dependent cooperativity (Fig. 2B). Although BH4-dependent kinetics was as yet mainly determined using the non-activated enzyme (19, 26), we conducted the assay utilizing the l-Phe-preincubated (activated) enzyme. To examine whether the Hill kinetic model describing BH4-dependent kinetic parameters depends on the activation state of the enzyme, the assay was run with and without prior incubation of the enzyme by l-Phe, and the results were compared with data from the literature (Table 2). Similar to l-Phe-dependent enzyme kinetics, Vmax of the activated enzyme was markedly lower in the discontinuous assay (3425 nmol Tyr/min × mg protein) when compared with the continuous assay (7288 nmol Tyr/min × mg protein), but the values for the apparent affinity to the ligand were comparable for both methods used (Km 24 μm; C0.5 33 μm) (Table 2). Although the analysis of the non-activated enzyme showed a reduction in Vmax (2277 nmol Tyr/min × mg protein), an increased apparent affinity to BH4 (Km 8 μm) was observed. In addition, steady state kinetic analysis of activated PAH indicated BH4-dependent-positive cooperativity (Hill coefficient, hBH4 2.2), whereas Michaelis-Menten kinetics for the non-activated PAH was confirmed (Fig. 2C). To obtain a better resolution of the range that best discriminates between both kinetic models, the assay was repeated in the limits of 0–50 μm BH4 (Fig. 2D). The data obtained for the activated enzyme clearly followed Hill kinetics (hBH4 2.0). This was in contrast to the non-activated enzyme, where nonlinear regression analysis showed hyperbolic kinetics following the Michaelis-Menten kinetic model (hBH4 1.0).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of BH4-dependent enzyme kinetic parameters obtained by standard PAH activity assay and direct in-well detection of l-Tyr production

Steady state kinetic parameters of WT MBP-PAH fusion protein are shown. Apparent affinities for BH4 (C0.5) and the Hill-coefficient (hBH4) as a measure of cooperativity are shown. Measurements were performed with (+) and without (−) l-Phe preincubation of the enzyme. Enzyme kinetic parameters were determined at variable BH4 concentrations (0–125 μm) and standard l-Phe concentrations (1 mm). CV, coefficient of variation, defined as the ratio of the S.D. to the mean value.

| l-Phe preincubation | Vmax | CV | Km | CV | C0.5 | CV | hBH4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmol l-Tyr/min × mg protein | % | μm | % | μm | % | |||

| WTa | + | 3425 ± 139b | 4 | 24 ± 3b | 12.5 | — | 1.0 | |

| WTc | − | 2277 ± 84 | 8 ± 1 | — | 1.0 | |||

| + | 7288 ± 282 | 4 | — | 33 ± 2 | 6 | 2.2 |

a Measurement by standard discontinuous PAH activity assay (HPLC and fluorimetric detection). Values are given as the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

b From Gersting et al. (17).

c Measurement by continuous PAH activity assay (direct in-well fluorescence detection). Values are given as mean ± S.E. of four independent experiments.

The enzyme kinetic parameters determined for l-Phe- and BH4-dependent enzyme kinetics were well comparable with previous studies using the standard discontinuous assay (17, 19), confirming the accuracy of our newly developed continuous assay. Furthermore, we aimed to determine the assay precision and calculated the coefficient of variation for all enzyme kinetic parameters of the activated enzyme, comparing the standard discontinuous with the continuous assay. The coefficients of variation for both l-Phe- and BH4-dependent kinetic parameters were similar for the two assays, revealing equal precision in enzyme kinetic measurements (Tables 1 and 2).

In conclusion, allosteric parameters obtained using the newly developed PAH activity assay were well comparable with results from standard discontinuous assays. The assay accuracy as well as precision confirmed the suitability of this method for the evaluation of enzyme kinetic parameters of PAH. In addition, PAH kinetic analysis using the continuous assay gave evidence for BH4-dependent cooperativity with PAH activation as a prerequisite.

BH4-dependent Cooperativity Relies on an Activated Structural Conformation of PAH

Three variant PAH enzymes, R68S, V106A, and the dimeric double-truncated form 103–427 (19, 37, 39, 40), were used to characterize the interrelation of enzyme activation and BH4-dependent cooperativity in more detail. In particular, we aimed to investigate whether the shift in enzyme kinetics from Michaelis-Menten to the Hill kinetic model depends on the presence of the l-Phe substrate itself or on structural attributes of the activated enzyme. It is known that substrate activation induces conformational changes (16, 37, 41–45) that convert the enzyme from a low activity T-state to a high activity R-state (Monod Wyman Changeux model) (46, 47). This is accompanied by an increase in quantum yield and a red-shifted emission maximum of the Trp-120 residue (48, 49). To determine the level of preactivation, structural attributes of the variants were compared with wild-type PAH. Spectral differences with and without preincubation by the substrate were utilized to assess the activation state.

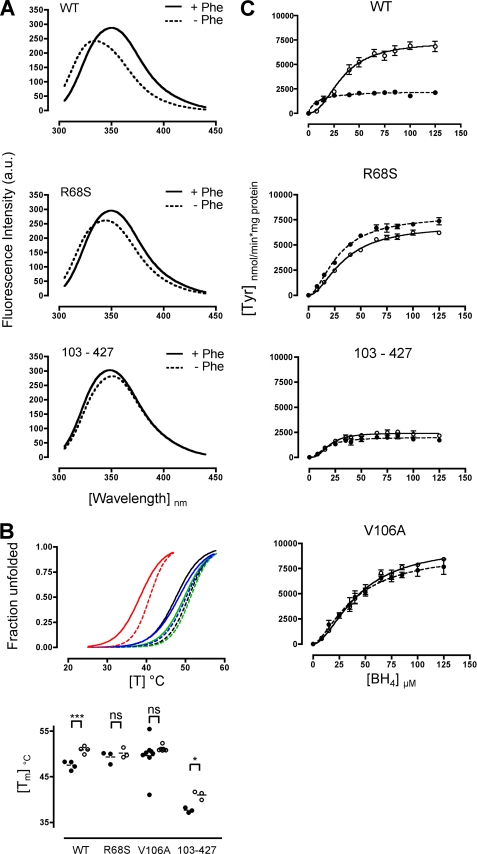

Tryptophan emission scans of wild-type PAH and the variants R68S and 103–427 were performed. As expected, wild-type PAH revealed a red shift in the emission maximum (340 to 351 nm) and an increase in intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (247–296 arbitrary units) upon the addition of l-Phe (Fig. 3A) (Table 3). Both variants showed a red-shifted emission maximum in the absence of l-Phe, which was more pronounced for the dimeric variant. Upon l-Phe preincubation, R68S yielded an emission maximum of the activated wild-type (351 nm), whereas the emission maximum of the dimeric PAH remained unchanged (350 nm). Both variants showed an increase in quantum yield but to a lesser extent than observed for wild-type PAH. Furthermore, we determined activation-induced structural rearrangements for all three variants by thermal unfolding using temperature-dependent differential scanning fluorimetry (Fig. 3B). Although the addition of l-Phe induced a highly significant increase in the transition midpoint for wild-type PAH (p = 0.0006), no significant increase was found for the variants R68S and V106A (Fig. 3B) (Table 4). These variants already showed increased transition midpoints at the activated wild-type level even without l-Phe preincubation. The dimeric PAH 103–427, although showing markedly decreased transition midpoints in general, revealed a significant increase when l-Phe was added (p = 0.0345). Taken together, all variants displayed structural characteristics that are indicative of mutation-induced conformational preactivation but to different extents.

FIGURE 3.

Determining the activated structural and functional conformation. A, intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra of the Factor Xa cleaved wild-type PAH, variant PAH R68S, and 103–427 are shown. Fluorescence emission spectra were acquired in the absence (dashed line) or presence (solid line) of 1 mm l-Phe. The excitation wavelength for Trp fluorescence measurements was 295 nm, with an excitation and emission slit of 2.5 and 5 nm, respectively. a.u., arbitrary units. B, differential scanning fluorimetry of the wild-type PAH and variant PAH R68S, V106A, and 103–427 fusion protein are shown. Denaturation of PAH was monitored by scanning a temperature range of 25 to 70 °C at a rate of 1.2 °C/min. Changes in 8-anilino-1-naphtalenesulfonic acid fluorescence emission were monitored at 500 nm (excitation 395 nm, slit widths 5.0/10.0 nm). The fraction unfolded of three to four independent experiments for wild-type, R68S, and 104–427 and seven to eight independent experiments for V106A without l-Phe (solid line) and with 1 mm l-Phe (dashed line) were determined (top panel; wild-type (black), R68S (blue), V106A (green), and 103–427 (red)), and the respective transition midpoints were calculated using the Boltzmann sigmoidal equation. For comparison of the transition midpoints, a paired t test, two-tailed, was used. Transition midpoints for wild-type and variant PAH, with (○) and without (●) l-Phe preincubation were plotted and compared (bottom panel) (ns, not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). C, enzyme activity measured for the wild-type PAH and the preactivated variants R68S, V106A, and 103–427 without preincubation (●) and with preincubation of the enzyme (○) with 1 mm l-Phe before initiation of the reaction by the addition of BH4. Data obtained for the non-preincubated and preincubated enzymes followed the Hill kinetic model as shown for the activated wild-type PAH. For all enzyme activity measurements, fluorescence intensity was recorded and after subtraction of the blank reaction converted to enzyme activity units (nmol of l-Tyr/min × mg protein) using the standard curve obtained by l-Tyr concentration measurements. Values are given as the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

TABLE 3.

Trp emission scans of PAH cleaved by factor Xa

Tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra were obtained with and without l-Phe (1 mm) preincubation of the cleaved WT PAH and preactivated variants. Fluorescence measurements were performed using a fluorescence spectrophotometer at an excitation wavelength of 295 nm with excitation and emission slits set to 2.5 and 5 nm, respectively. a.u., arbitrary units.

| Without l-Phe preincubation |

With l-Phe preincubation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength | Fluorescence intensity | Wavelength | Fluorescence intensity | |

| nm | a.u. | nm | a.u. | |

| WT | 340 | 247 | 351 | 296 |

| R68S | 345 | 266 | 351 | 304 |

| 103–427 | 350 | 288 | 350 | 310 |

TABLE 4.

Mean transition midpoints of thermal denaturation assays

Calculation of transition midpoints from differential scanning fluorimetry of WT PAH and preactivated variants with and without 1 mm l-Phe. Transition midpoints were calculated using the Boltzmann sigmoidal equation. Transition midpoints are given as the mean ± S.E. of three to four for V106A eight independent experiments. Mean transition midpoints with and without l-Phe were compared using a paired t test, two-tailed. NS, not significant.

|

Tm |

p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without l-Phe preincubation | With l-Phe preincubation | ||

| °C | |||

| WT | 47.49 ± 0.46 | 50.90 ± 0.38 | p = 0.0006 |

| R68S | 49.28 ± 0.78 | 50.15 ± 0.64 | NS |

| V106A | 49.63 ± 1.40 | 51.11 ± 0.21 | NS |

| 103–427 | 37.68 ± 0.32 | 40.99 ± 0.54 | p = 0.0345 |

According to the results on structural preactivation, evaluation of the activation-fold determined by the continuous assay (Fig. 3C) (Table 5) confirmed functional preactivation of the variants without l-Phe preincubation (R68S, 0.9; V106A, 1.0; 103–427, 1.3). Nonlinear regression analysis of BH4-dependent kinetics of all three preactivated variants followed the Hill model as shown for activated wild-type PAH. Although distinctly positive, the Hill-coefficients ranging from 1.6 to 2.1 were lower than that determined for activated wild-type PAH (h, 2.2). The dimeric variant 103–427 showed a Vmax (1980 nmol Tyr/min × mg protein) comparable with that of the non-activated wild-type PAH, which did not change markedly upon l-Phe preincubation (2421 nmol Tyr/min × mg protein). This is in contrast to an increase by 3.2-fold observed for wild-type PAH preincubated with l-Phe. However, for the variants R68S and V106A, a Vmax comparable with the activated wild-type PAH was found without l-Phe preincubation, and no further increase was measured when the substrate was present. R68S and V106A without l-Phe preincubation showed lower cofactor affinities than the non-activated wild-type PAH; however, the values were at the same level as determined for the l-Phe preincubated wild-type PAH. C0.5 of the dimeric PAH 103–427 was 2-fold higher as compared with the non-activated wild-type PAH. Notably, no marked changes in sigmoidal behavior and kinetic parameters were observed for all variants irrespective of whether they were preincubated by l-Phe (Fig. 3C) (Table 5). In summary, analyses of structurally preactivated variants substantiated BH4-dependent positive cooperativity of the activated enzyme, where the kinetic model does not rely on the presence of l-Phe but is determined by activating conformational rearrangements.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of BH4-dependent enzyme kinetic parameters of variant PAH proteins with and without l-Phe preincubation

Steady state kinetic parameters of variant MBP-PAH fusion proteins were determined by direct in-well activity measurements. Apparent affinities for BH4 (C0.5) and the Hill-coefficient (h) as a measure of cooperativity are shown. Enzyme kinetic parameters determined at variable BH4 concentrations (0–125 μm) and standard l-Phe concentrations (1 mm) with and without preincubation of the enzyme with l-Phe (1 mm).

| Without l-Phe preincubation |

With l-Phe preincubation |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vmaxa | Km | C0.5a | hBH4 | Vmaxa | C 0.5a | hBH4 | Activation foldb | |

| nmol l-Tyr/min × mg protein | μm | μm | nmol l-Tyr/min × mg protein | μm | ||||

| WT | 2277 ± 84 | 8 ± 1 | — | 1.0 | 7288 ± 282 | 33 ± 2 | 2.2 | 2.8 |

| R68S | 7928 ± 232 | — | 29 ± 1 | 1.8 | 6940 ± 225 | 34 ± 2 | 1.8 | 0.9 |

| V106A | 9041 ± 489 | — | 40 ± 3 | 1.6 | 9773 ± 534 | 43 ± 4 | 1.8 | 1.0 |

| 103–427 | 1980 ± 100 | — | 16 ± 2 | 2.1 | 2421 ± 73 | 19 ± 1 | 2.6 | 1.3 |

a Values are given as the mean ± S.E. of three independent measurements.

b Fold increase in PAH activity by l-Phe preincubation calculated at the standard l-Phe (1 mm) and BH4 (75 μm) concentrations.

Evaluation of Model Fitting

To validate the experimental data on conditions that determine PAH cooperativity, an extended evaluation of model fitting by nonlinear regression analysis of BH4-dependent kinetics was performed. The test parameters goodness of fit (R2), root mean square (Sy.x), runs test, and residuals of values were compared, and an F-test was run to discriminate between the two nested kinetic models Michaelis-Menten and Hill for activated and non-activated PAH, respectively.

First we analyzed non-activated PAH. A simple calculation of goodness of fit (R2) did not allow for distinction between the two models used for data analyses (R2MM 0.97; R2H 0.97) (supplemental Table 1). The residuals of values (supplemental Fig. 2) and, thus, the S.D. of the residuals also showed no marked improvement of data description by the more complicated Hill equation. Although the runs test showed a marginally significant deviation of the data from the Michaelis-Menten model (p = 0.048), the F-test proved the simpler Michaelis-Menten kinetics to be the correct model for data analysis of BH4-dependent kinetics of non-activated PAH (F ratio 2.86; p = 0.125) (Table 6). This was confirmed by refined analysis of BH4-dependent kinetics in the limits of 0–50 μm. As before, R2, Sy.x, and the residuals of values did not allow for a clear distinction between the two models (supplemental Table 1). However, no significant deviation of the data from any of the two equations could be determined by the runs test. Yet again, the F-test revealed that the data were best described by the simpler Michaelis-Menten kinetic model (F ratio 0.58; p = 0.463) (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Comparison of two nested non-linear regression models

F-test for two nested models after measurement of wild-type PAH kinetics without and with preincubation of the enzyme with l-Phe. Enzyme kinetics were measured with l-Phe (1 mm) and BH4 (0–125 μm and 0–50 μm). The F-test assumes that the Michaelis-Menten equation is a simpler case of the Hill equation. If the simpler model is correct, the F ratio is near 1.0. To verify the correctness of the more complicated model (if the F ratio is >1.0), the p value is calculated. If the p value is less than the traditional significance level of 5%, it can be concluded that the data do not randomly fit to the more complicated model but fit significantly better to Hill than to Michaelis-Menten kinetics.

| BH4 | F-test |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| l-Phe preincubation | F ratio | p value | |

| μm | |||

| 0–125 | − | 2.86 | 0.125 |

| 0–125 | + | 274.28 | <0.0001 |

| 0–50 | − | 0.58 | 0.463 |

| 0–50 | + | 62.79 | <0.0001 |

In contrast to non-activated PAH, enzyme activation by l-Phe now resulted in marked differences of the two models even by goodness of fit (R2MM 0.96; R2H 0.99) (supplemental Table 1) (Table 6). In addition, evaluation of the data by the Hill equation revealed a decrease of Sy.x by ∼2-fold, and the residuals of values showed less fluctuation (supplemental Fig. 2). The runs test showed no significant deviation from any of the two models used, but comparison by the F-test resulted in a highly significant p value (F ratio 274.28; p < 0.0001) (Table 6) favoring Hill kinetics. Detailed analysis at low BH4 concentrations (0–50 μm) additionally uncovered a significant deviation of the data from Michaelis-Menten kinetics in the runs test (p = 0.024) (Table 6) (supplemental Table 1 and Fig. 2). Taken together, the evaluation of model fitting provided clear evidence for BH4-dependent positive cooperativity of activated PAH, whereas the BH4-dependent kinetics of the non-activated enzyme followed the non-cooperative Michaelis-Menten model.

Next, we aimed to learn whether the presence of the l-Phe substrate has an impact on the kinetic model beyond l-Phe induced conformational changes upon PAH activation. To validate structural preactivation of R68S, V106A, and of the dimeric double-truncated 103–427 PAH, we first analyzed whether BH4-dependent kinetic data would fit significantly better to the more complex Hill equation even without l-Phe preincubation. Indeed, we identified an increase in R2, a more than 2-fold decrease in Sy.x, and a significant deviation of the Michaelis-Menten model in the runs test for the variants R68S and V106A (supplemental Table 2). Only the dimeric 103–427 showed a less pronounced reduction in Sy.x and no discrimination between the two models in the runs test. In all cases fluctuation of the residuals of values was lower using the Hill equation (supplemental Fig. 2). This was in line with the results obtained by the F-test (p < 0.01) (Table 7). Hence, the kinetic data fit significantly better to the more complicated Hill equation, indicating substrate-independent structural preactivation. Second, model fitting of the structurally activated variants was compared with and without prior incubation with l-Phe in the next step. All in all, the presence of l-Phe only negligibly changed the test results. Only for the dimeric 103–427, Sy.x was markedly lower upon evaluation by sigmoidal kinetics, and the runs test classified Michaelis-Menten as an incorrect model (supplemental Table 2). Again, all data provided evidence for a correct data description by the Hill kinetic model (supplemental Table 2 and Fig. 2) (Table 7).

TABLE 7.

Comparison of two nested non-linear regression models with and without preincubation of preactivated variants

F-test for two nested models after measurement of enzyme kinetics without and with preincubation of the enzyme with l-Phe. Enzyme kinetics were measured with l-Phe (1 mm) and BH4 (0–125 μm). The F-test assumes that the Michaelis-Menten equation is a simpler case of the Hill equation. If the simpler model is correct, the F ratio is near 1.0. To verify the correctness of the more complicated model (if the F ratio is >1.0), the p value is calculated. If the p value is less than the traditional significance level of 5%, it can be concluded that the data do not randomly fit to the more complicated model but fit significantly better to Hill than to Michaelis-Menten kinetics.

| F-test |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| l-Phe preincubation | F ratio | p value | |

| R68S | − | 58.02 | <0.0001 |

| R68S | + | 69.63 | <0.0001 |

| V106A | − | 24.00 | <0.001 |

| V106A | + | 35.44 | <0.001 |

| 103–427 | − | 10.66 | <0.01 |

| 103–427 | + | 40.23 | <0.001 |

In summary, extended analysis and comparison of the two non-linear regression models Michaelis-Menten and Hill revealed non-cooperative kinetics of the non-activated enzyme, whereas activation of the enzyme clearly induced cooperativity. Moreover, l-Phe preincubation did not have a significant impact on the kinetic model of structurally activated variant PAH.

DISCUSSION

In this study we established a new method for the evaluation of PAH kinetic parameters, allowing for real-time detection of enzyme activity. Continuous assays are the safest means of determining reaction velocity from the slope of a plot of signal versus time (23). However, many assays used for the evaluation of PAH enzyme kinetics are discontinuous due to chromatographic separation of the substrate from the product before product detection. We aimed to establish the measurement of l-Tyr production without separation from the substrate l-Phe. The spectral properties of the aromatic amino acids and differences in quantum yield allowed for direct detection of l-Tyr uninfluenced by l-Phe concentrations. However, the IFE of BH4 at the excitation and emission maxima of l-Tyr (274 and 304 nm, respectively) had to be taken into account. By analyzing the IFE of BH4 on l-Tyr fluorescence in the entire range of concentrations used in the assay, a concentration-dependent correction factor was defined (27, 28). This facilitated accurate and precise quantification of l-Tyr product formation inside the assay reaction mixture. In addition, all substances required to perform the activity assay were applied by means of an integrated injection system. Although equally precise, this led to marked time reduction in sample preparation. Furthermore, sequential duplicate measurements subsequent to sample injections of up to four different PAH proteins in a 96-well format substantially increased the throughput of enzyme kinetics analyses. The addition of various substrate and cofactor concentrations as well as their injection at different time-points proved this method to be very flexible, allowing for numerous assay conditions in one single run.

By applying the new technique, we observed burst-phase kinetics of preactivated and lag-phase kinetics of non-activated PAH. The discontinuous assays used previously measured product formation from the initiation of the reaction to a defined end point, and burst- and lag-phase kinetics were not taken into consideration. However, pre-steady state kinetics should not be ignored as they may lead to erroneous interpretations regarding the existence of cooperativity (50). A complete model describing the enzyme reaction is a prerequisite for comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms involved in pre-steady state kinetics. Assumptions to approach such a model have been made using a prokaryotic monomeric PAH (51). Yet this enzyme lacks the regulatory properties of the oligomeric multidomain human protein and is, therefore, not applicable to human PAH. Therefore, we decided to assess steady state kinetics at a 1-min time frame after the burst-phase and provided a linear rate of reaction velocity for the non-activated and the activated enzyme while remaining within 10% of substrate turnover.

The data of continuous measurements were compared with our results obtained previously by the discontinuous assay as well as to data described in the literature. Differences in Vmax between the discontinuous and the continuous assay were found. These variations may be due to the different methods used, yet additional aspects such as different time frames for measurement of steady state kinetics and the improvement of protein purification methods in our laboratory within the last years play an important role and may further explain these findings. Notably, large differences in enzyme activities, ranging up to 7-fold, can also be found in the literature (16, 37, 52, 53). However, kinetic parameters describing apparent affinity and enzyme allostery (S0.5, Km/C0.5, Hill coefficient (h), and activation-fold) were similar to results obtained using discontinuous assays and to results previously described (17, 37), confirming the accuracy of our newly developed continuous assay. Furthermore, calculation of the coefficient of variation proved the new assay to be as precise as the standard discontinuous assays applied.

Interestingly, data points did not fit to the Michaelis-Menten kinetic model when the method was applied to determine BH4-dependent enzyme kinetics. Instead, a good fit was found applying the Hill kinetic model. All previous studies using different methods had shown hyperbolic non-cooperative binding kinetics of the cofactor to PAH (17, 19, 25, 53). When applying the continuous assay, BH4-dependent kinetics of wild-type PAH revealed positive cooperativity. However, our experiments were performed with an l-Phe-preincubated (activated) enzyme, whereas in most of the previous studies the non-activated enzyme had been used. To elucidate whether PAH activation determines cofactor dependent cooperativity, we compared enzyme kinetics of non-activated and of activated PAH. In agreement with previous findings, the continuous assay without l-Phe preincubation resulted in hyperbolic binding kinetics of BH4. Together with the observed BH4-dependent cooperativity of activated PAH, these results suggested that cooperativity of BH4 depends on an activated state of the enzyme.

Thus, we investigated whether the shift in enzyme kinetics from Michaelis-Menten to the Hill kinetic model depends on the presence of the l-Phe substrate itself or on structural attributes of the activated enzyme. This was dissected by means of conformationally preactivated genetic variants of PAH (R68S, V106A, dimeric 103–427). Using two different spectroscopic techniques we analyzed local and global effects on protein structure by mutation/truncation or by l-Phe, respectively, and correlated this with enzyme kinetic parameters. Preincubation of wild-type PAH with l-Phe leads to a series of structural and functional changes resulting in enzyme activation (16, 37, 41–45). On the structural level these include a red-shifted and enhanced tryptophan emission and a right-shifted thermal denaturation profile. On the functional level an increase in Vmax, a decreased apparent affinity, and a switch from non-cooperative to positive cooperative kinetics accounted for activation. All three variants displayed characteristics of structural and functional preactivation but to varying degrees. Preactivation of the variants was reflected by the activation-fold with values ranging from 0.9 to 1.3. Furthermore, all variants displayed clear positive cooperativity without prior incubation with the substrate. In the presence of l-Phe some selective structural changes for single variants were observed, i.e. a minor shift in tryptophan emission for R68S and a significantly enhanced transition midpoint of the thermal denaturation for 103–427. However, no variant showed decisive changes in enzyme kinetic parameters upon l-Phe preincubation. This observation held true irrespective of whether the parameter was at the same level as activated wild-type PAH. These data provide evidence that the variants are activated at a structural level and that l-Phe does not have any additional effect on their activity and cooperativity. We conclude that the conformation associated with preactivation accounts for positive cooperativity where l-Phe induces activating conformational changes that in turn lead to allostery. The addition of the substrate to the assay, however, does not induce cooperativity by itself.

Mathematical analyses of the data obtained by enzyme kinetic measurements were used to substantiate our findings on the comparison of the kinetic models (29, 34, 54–58). A simple calculation of best-fit parameters for enzyme kinetic data (R2, root mean square, runs test) did not always allow for a clear distinction between the Michaelis-Menten and the Hill model. However, the application of an F-test made evident to which biological mechanism the kinetic data are linked with highest probability (29–32). Even though a more complex model like the Hill equation would always fit the experimental data better than a simpler model, the F-test revealed that kinetics of non-preincubated wild-type PAH were not described significantly better by this model. However, analysis of the l-Phe-activated enzyme gave a significant p value in the F-test for the Hill equation and, thus, proved positive cooperativity. These findings were corroborated when enzyme kinetic analyses were focused on the area of distinct sigmoidality, i.e. on the range of 0 to 50 μm BH4. Statistical analyses of model fitting for preactivated PAH variants verified BH4-dependent cooperativity even without prior incubation with l-Phe. Taken together, mathematical analyses of the cofactor-dependent enzyme kinetic data confirmed that the non-activated enzyme follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics, whereas the activated enzyme shows cooperativity.

Cooperativity of PAH to the l-Phe substrate is reflected by a Hill coefficient of >3.0 and has previously been described to be propagated throughout the whole tetramer (59). Alterations in the orientation of the oligomerization domain transfer cooperative activating conformational changes from one to the other dimer. This requires a switch between a low affinity “T-state” conformation to a high affinity “R-state” conformation at elevated l-Phe concentrations following the model proposed by Monod, Wyman, and Changeux. The Hill coefficients of BH4-dependent kinetics determined for the l-Phe preincubated (activated) wild-type PAH and the preactivated variants in this study were ∼2.0. The current study may, thus, allow speculating that enzyme activation leads to positive cooperativity in BH4 binding. The dissimilar Hill coefficients for substrate and cofactor binding may also show that cooperative binding of BH4 follows different conformational alterations propagating cooperativity than found for l-Phe binding. This may explain that positive cooperativity was not only observed for the tetrameric enzyme but also for the truncated PAH 103–427 that lacks the regulatory and the oligomerization domain and, thus, only exists in dimeric form. However, whether there is cooperative behavior of PAH upon BH4 binding in the strict mechanistic sense or hysteresis leading to cooperative kinetics could not be fully elucidated. Further crystallization and NMR studies are needed for a thorough understanding of the impact of l-Phe and BH4 binding on cooperative allosteric changes in PAH structure.

In conclusion, the development of a novel method for real-time measurement of PAH activity provided accurate, fast, and efficient PAH enzyme kinetic measurements in a 96-well format. Application of this method for wild-type PAH revealed BH4-dependent positive cooperativity previously not described. Spectroscopic assessment of activating conformational changes and statistical evaluation of model-fitting disclosed PAH activation as a prerequisite for BH4-dependent positive cooperativity. BH4 has recently been approved as a pharmacological chaperone drug in the treatment of phenylketonuria. We showed that the presence of l-Phe affects the BH4-dependent kinetic properties of PAH. These findings may, thus, have implications for an individualized therapy, as they support the hypothesis that patient metabolic state may have a more significant effect on the interplay of the drug and the conformation and function of the target protein than currently appreciated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Christoph Siegel for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Bavarian Genome Research Network (BayGene).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Materials and Methods, Tables 1 and 2, and Figs. 1 and 2.

- PAH

- phenylalanine hydroxylase

- IFE

- inner filter effect

- BH4

- 6R-l-erythro-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin

- l-Phe

- l-phenylalanine

- l-Tyr

- l-tyrosine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zschocke J. (2003) Hum. Mutat. 21, 345–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiege B., Blau N. (2007) J. Pediatr. 150, 627–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muntau A. C., Röschinger W., Habich M., Demmelmair H., Hoffmann B., Sommerhoff C. P., Roscher A. A. (2002) N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 2122–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy H. L., Milanowski A., Chakrapani A., Cleary M., Lee P., Trefz F. K., Whitley C. B., Feillet F., Feigenbaum A. S., Bebchuk J. D., Christ-Schmidt H., Dorenbaum A. (2007) Lancet 370, 504–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trefz F. K., Burton B. K., Longo N., Casanova M. M., Gruskin D. J., Dorenbaum A., Kakkis E. D., Crombez E. A., Grange D. K., Harmatz P., Lipson M. H., Milanowski A., Randolph L. M., Vockley J., Whitley C. B., Wolff J. A., Bebchuk J., Christ-Schmidt H., Hennermann J. B. (2009) J. Pediatr. 154, 700–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiman R., Gray D. W., Hill M. A. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 24637–24646 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiman R., Xia T., Hill M. A., Gray D. W. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 24647–24656 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xia T., Gray D. W., Shiman R. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 24657–24665 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiman R., Gray D. W. (1980) J. Biol. Chem. 255, 4793–4800 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiman R., Jones S. H., Gray D. W. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 11633–11642 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shiman R., Mortimore G. E., Schworer C. M., Gray D. W. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 11213–11216 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitnaul L. J., Shiman R. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 885–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen O. A., Stokka A. J., Flatmark T., Hough E. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 333, 747–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solstad T., Stokka A. J., Andersen O. A., Flatmark T. (2003) Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 981–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen O. A., Flatmark T., Hough E. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 320, 1095–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stokka A. J., Carvalho R. N., Barroso J. F., Flatmark T. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26571–26580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gersting S. W., Kemter K. F., Staudigl M., Messing D. D., Danecka M. K., Lagler F. B., Sommerhoff C. P., Roscher A. A., Muntau A. C. (2008) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 83, 5–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waters P. J., Parniak M. A., Akerman B. R., Scriver C. R. (2000) Mol. Genet. Metab. 69, 101–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erlandsen H., Pey A. L., Gámez A., Pérez B., Desviat L. R., Aguado C., Koch R., Surendran S., Tyring S., Matalon R., Scriver C. R., Ugarte M., Martínez A., Stevens R. C. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 16903–16908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bailey S. W., Ayling J. E. (1980) Anal. Biochem. 107, 156–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ledley F. D., Grenett H. E., Woo S. L. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 2228–2233 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez A., Knappskog P. M., Olafsdottir S., Døskeland A. P., Eiken H. G., Svebak R. M., Bozzini M., Apold J., Flatmark T. (1995) Biochem. J. 306, 589–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Copeland R. A. (2000) Enzymes: A Practical Introduction to Structure, Mechanism, and Data Analysis, 2nd Ed., Wiley-VCH, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher D. B., Kaufman S. (1973) J. Biol. Chem. 248, 4345–4353 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flatmark T., Stokka A. J., Berge S. V. (2001) Anal. Biochem. 294, 95–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pey A. L., Martinez A. (2005) Mol. Genet. Metab. 86, S43–S53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y., Kati W., Chen C. M., Tripathi R., Molla A., Kohlbrenner W. (1999) Anal. Biochem. 267, 331–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmier M. O., Van Doren S. R. (2007) Anal. Biochem. 371, 43–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reissmann S., Parnot C., Booth C. R., Chiu W., Frydman J. (2007) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 432–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hutt D. M., Baltz J. M., Ngsee J. K. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 20197–20203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brock D. A., Ehrenman K., Ammann R., Tang Y., Gomer R. H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 52262–52272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Koninck P., Schulman H. (1998) Science 279, 227–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James J. R., Oliveira M. I., Carmo A. M., Iaboni A., Davis S. J. (2006) Nat. Methods 3, 1001–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller W. L., Matewish M. J., McNally D. J., Ishiyama N., Anderson E. M., Brewer D., Brisson J. R., Berghuis A. M., Lam J. S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 3507–3518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bailey S. W., Ayling J. E. (1978) J. Biol. Chem. 253, 1598–1605 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaufman S. (1993) Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 67, 77–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knappskog P. M., Flatmark T., Aarden J. M., Haavik J., Martínez A. (1996) Eur. J. Biochem. 242, 813–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bjørgo E., de Carvalho R. M., Flatmark T. (2001) Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 997–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pérez B., Desviat L. R., Gómez-Puertas P., Martínez A., Stevens R. C., Ugarte M. (2005) Mol. Genet. Metab. 86, S11–S16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gersting S. W., Lagler F. B., Eichinger A., Kemter K. F., Danecka M. K., Messing D. D., Staudigl M., Domdey K. A., Zsifkovits C., Fingerhut R., Glossmann H., Roscher A. A., Muntau A. C. (2010) Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 2039–2049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kappock T. J., Harkins P. C., Friedenberg S., Caradonna J. P. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30532–30544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis M. D., Parniak M. A., Kaufman S., Kempner E. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 491–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chehin R., Thorolfsson M., Knappskog P. M., Martinez A., Flatmark T., Arrondo J. L., Muga A. (1998) FEBS Lett. 422, 225–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teigen K., Frøystein N. A., Martínez A. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 294, 807–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thórólfsson M., Ibarra-Molero B., Fojan P., Petersen S. B., Sanchez-Ruiz J. M., Martínez A. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 7573–7585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Monod J., Wyman J., Changeux J. P. (1965) J. Mol. Biol. 12, 88–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koshland D. E., Jr., Némethy G., Filmer D. (1966) Biochemistry 5, 365–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knappskog P. M., Haavik J. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 11790–11799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shiman R., Gray D. W., Pater A. (1979) J. Biol. Chem. 254, 11300–11306 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cornish-Bowden A., Cárdenas M. L. (1987) J. Theor. Biol. 124, 1–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Volner A., Zoidakis J., Abu-Omar M. M. (2003) J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 8, 121–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Erlandsen H., Bjørgo E., Flatmark T., Stevens R. C. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 2208–2217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pey A. L., Pérez B., Desviat L. R., Martínez M. A., Aguado C., Erlandsen H., Gámez A., Stevens R. C., Thórólfsson M., Ugarte M., Martínez A. (2004) Hum. Mutat. 24, 388–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee J., Johnson J., Ding Z., Paetzel M., Cornell R. B. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 33535–33548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Velloso L. M., Bhaskaran S. S., Schuch R., Fischetti V. A., Stebbins C. E. (2008) EMBO Rep. 9, 199–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sawicki A., Willows R. D. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 31294–31302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Isin E. M., Guengerich F. P. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9127–9136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pauwels F., Vergauwen B., Vanrobaeys F., Devreese B., Van Beeumen J. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 16658–16666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thórólfsson M., Teigen K., Martínez A. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 3419–3428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.