Abstract

All organisms are subject to DNA damage from both endogenous and environmental sources. DNA damage that is not fully repaired can lead to mutations. Mutagenesis is now understood to be an active process, in part facilitated by lower-fidelity DNA polymerases that replicate DNA in an error-prone manner. Y-family DNA polymerases, found throughout all domains of life, are characterized by their lower fidelity on undamaged DNA and their specialized ability to copy damaged DNA. Two E. coli Y-family DNA polymerases are responsible for copying damaged DNA as well as for mutagenesis. These DNA polymerases interact with different forms of UmuD, a dynamic protein that regulates mutagenesis. The UmuD gene products, regulated by the SOS response, exist in two principal forms: UmuD2, which prevents mutagenesis, and UmuD2′, which facilitates UV-induced mutagenesis. This paper focuses on the multiple conformations of the UmuD gene products and how their protein interactions regulate mutagenesis.

1. Mutagenesis Due to Y-Family DNA Polymerases

The observation of nonmutable phenotypes of E. coli umu (UV-nonmutable) mutants led to the discovery that mutagenesis in E. coli is an active process [1–4]. The mutagenesis process utilizes specialized DNA polymerases belonging to the Y family [5]. Y-family DNA polymerases are found in all domains of life and have the specialized ability to replicate damaged DNA, a process known as translesion synthesis (TLS) [5–8]. This specialized ability comes at the cost of lower fidelity in replicating undamaged DNA compared to replicative DNA polymerases. Indeed, Y-family polymerases are from one to several orders of magnitude less accurate than replicative DNA polymerases [9–11]. Moreover, Y-family polymerases lack intrinsic 3′-5′-exonuclease activity and have inherent low processivity [6, 8, 12–14]. Because the cellular functions of Y-family DNA polymerases are potentially mutagenic, their activities are tightly regulated. E. coli has two members of the Y family, DNA pol IV (DinB, encoded by the dinB gene) [15] and pol V (UmuD2′C, encoded by the UmuD and UmuC genes) [16, 17], whose functions are regulated on multiple levels. A key feature of their regulation is their interactions with products of the umuD gene.

2. SOS Regulation

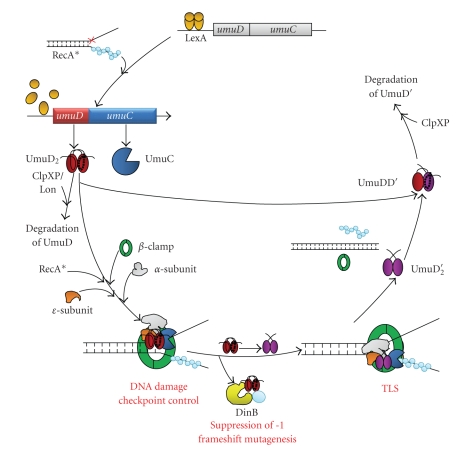

The UmuD gene is found in an operon with UmuC [18, 19]. The expression of these genes, as well as the dinB gene, is negatively regulated by the LexA repressor as part of the SOS response [7, 20]. LexA binds to a sequence in the operator region of regulated genes called the “SOS box,” with a consensus sequence of 5′taCTGtatatatataCAGta, where the most conserved residues are in capital letters [21]. Upon DNA damage, a region of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) forms due to the inability to continue replication of the damaged DNA. RecA polymerizes on the ssDNA, forming a RecA/ssDNA nucleoprotein filament, which is the inducing signal for the SOS response (Figure 1) [22]. Upon binding to the RecA/ssDNA filament, LexA undergoes a conformational change that stimulates its latent ability to cleave itself [23]. LexA cleavage inactivates it as a repressor and exposes a proteolysis signal sequence, leading to degradation of LexA [24] and to increased expression of at least 57 SOS-regulated genes, including UmuD [20]. The cellular levels of UmuD, UmuC, and DinB all increase approximately 10-fold upon SOS induction, with UmuD increasing from ~180 to ~2400 molecules, UmuC increasing from ~15 to ~200 molecules, and DinB increasing from ~250 to ~2500 molecules per cell [25, 26]. The products of SOS-regulated genes are involved in DNA repair, DNA damage tolerance, and regulation of cell division. As the cell recovers from genotoxic stresses, it is presumed that the concentration of ssDNA is reduced, resulting in a decrease of RecA/ssDNA filament in the cell. This occurrence allows intact LexA to accumulate, thereby diminishing the SOS response [4].

Figure 1.

Life cycle and interactions of UmuD gene products. Details are described in the text.

3. UmuD is a Molecular Adaptor That Regulates Mutagenesis

Following initiation of the SOS response, UmuD2 is the predominant form of the protein for 20–30 minutes [27]. The presence of UmuD and UmuC protects the cell from the potential deleterious effects of the error-prone DNA damage response pathway, a function which is genetically distinct from their role in SOS mutagenesis [27, 28]. UmuD2, together with UmuC, may act in a primitive DNA damage checkpoint, as they specifically inhibit DNA replication without an effect on transcription or translation when present at elevated levels in cells grown at 30°C [27, 29]. UmuD and UmuC also slow the resumption of DNA replication after UV irradiation [27]. Therefore, UmuDC acts in a noncatalytic fashion by delaying SOS mutagenesis and thereby allowing accurate pathways such as nucleotide excision repair time to proceed [27, 28]. Moreover, UmuD interacts with DinB and inhibits its mutagenic −1 frameshift activity [30].

UmuD2 interacts with the RecA/ssDNA filament, which stimulates the ability of UmuD to cleave itself, removing its N-terminal 24 amino acids [31–33]. UmuD is homologous to the C-terminal domain of LexA, and their cleavage reactions are remarkably similar: both proteins utilize a Ser-Lys (S60-K97 in UmuD) catalytic dyad, which is also similar to the reaction carried out by signal peptidases [34]. By analogy to signal peptidases, K97 is proposed to deprotonate S60, which is then capable of nucleophilic attack on the peptide backbone [34]. Therefore, UmuD2 and LexA also undergo autodigestion at elevated pH [23, 33]. The kinetics of cleavage are remarkably different for UmuD2 and LexA, with cleavage of LexA much more efficient than that of UmuD2 in both RecA- and alkaline-mediated cleavage [33]. Moreover, LexA undergoes intramolecular cleavage [35] while UmuD2 is capable of intermolecular cleavage [36–38].

RecA-facilitated cleavage of UmuD to UmuD′ occurs 20–40 minutes after the induction of SOS and serves to initiate TLS [4, 27]. UmuD′ together with UmuC forms the TLS polymerase Pol V that is active in the damage tolerance mechanism SOS mutagenesis [4, 16, 17, 39, 40]. Additionally, UmuD′ and UmuC inhibit RecA-dependent homologous recombination as a result of the direct interaction of UmuD′C with the RecA/ssDNA nucleoprotein filament, thereby preventing accurate recombination repair [41–43]. Taken together, these results support a model in which full-length UmuD acts to prevent mutagenesis while UmuD′ facilitates it.

4. Structure and Dynamics of UmuD

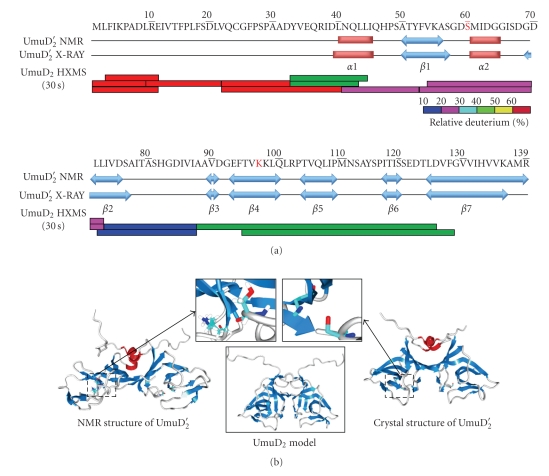

Since the UmuD gene products play crucial roles in managing the biological responses to DNA damage, the conformation and dynamics of UmuD2 and UmuD2′ are of great interest. To date, the structure of full-length UmuD2 has not been amenable to crystallization or NMR analysis. However, the NMR [44, 45] and crystal [46] structures (Figure 2) of UmuD2′ have been solved. Both structures show that UmuD2′ is a homodimer with a C2 axis of symmetry and show similar secondary structures: UmuD2′ is composed primarily of β-strands with two short α-helices in each monomer. The C-terminal globular domain (residues 40–139) is mainly composed of curved antiparallel β-strands connected by tight turns with a long C-terminal strand, β7, that spans both monomers (Figure 2). Residues between positions 132–139 in β7 in UmuD and UmuD′ show the strongest interdimer cross-linking of their monocysteine derivatives [47]. The α1 helices pack against each other in the dimer interface. Both UmuD2 and UmuD2′ are exceptionally tight dimers with equilibrium dissociation constants K DS < 10 pM [48]. The active site residue K97 is in the middle of strand β4 while S60 is in helix α2 (Figure 2) [44, 46]. In both structures, the short N-terminal arms that remain after cleavage (residues 25–39) are largely unstructured [45, 46].

Figure 2.

The secondary and tertiary structure of UmuD2 and UmuD2′. (a) Secondary structure comparison between the UmuD2′ NMR [44, 45] and crystal [46] structures. The α helices are shown in red, and β sheets are shown in blue. Relative deuterium incorporation of UmuD2 at 30 sec labeling in HXMS experiments is shown, and the colors are based on the relative deuterium percentage scale shown [51]. (b) Comparison of the NMR [44, 45] and crystal [46] structures of UmuD2′. The color of the α helices and β sheets is consistent with (a). The active site regions are boxed and shown in the insets. A model of full-length UmuD2 is shown [52].

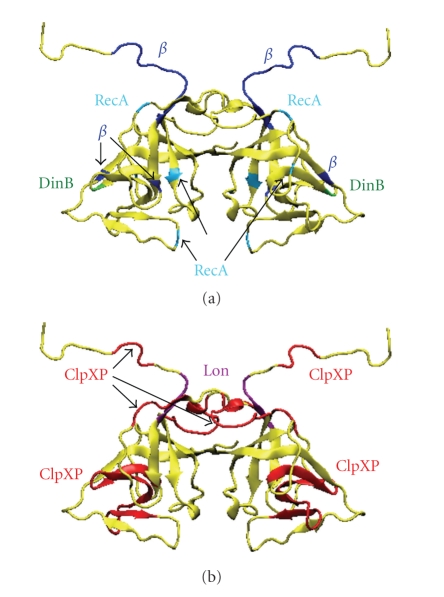

The differences between the X-ray and NMR structures of UmuD′ are not insignificant [44]. The RMSD of the backbone atoms (residues 40–139) between the two structures of UmuD2′ is 4.59 Å [44]. Moreover, the active site in the crystal structure appears correctly positioned for catalysis, while in the NMR structure, the catalytic residues Ser60 and Lys97 are over 7 Å apart and are not positioned appropriately (Figure 2) [44, 46]. It has been suggested that the conformation of UmuD2′ in the crystal structure is similar to the conformation of UmuD2 bound to the RecA/ssDNA nucleoprotein filament [44], which might indicate the mechanism whereby RecA/ssDNA acts as a coprotease in facilitating UmuD cleavage. Several residues on the outer loops and the surface of UmuD2, specifically Val34, Ser57, Ser67, Ser81, and Ser112, each when changed to single cysteines, have been shown to cross-link to RecA and therefore are likely sites of interaction between the two proteins (Figure 3) [49]. The structure of UmuD2′C-RecA/ssDNA complex determined by using cryo-electron microscopy shows UmuD2′C bound deep in the groove of the RecA/ssDNA nucleoprotein filament and a second binding mode with UmuD2′C at the end of the RecA/ssDNA filament [50].

Figure 3.

Protein interaction sites on UmuD. (a) The β clamp interacts with residues 14–19, 24, 52, and 126 (blue) [53]. RecA interacts with residues 34, 81, 57, 67, and 112 (cyan) [49]. DinB interacts with residue 91 on UmuD (green) [30]. (b) ClpXP interacts with residues 9–12, 33–37, 41–51, and 85–109 (red) [123]. Lon binds to regions close to the residues that are important for interaction with ClpXP, residues 15–19 (violet) [125].

The differences in the X-ray and NMR structures of UmuD′ and other findings suggested that UmuD and UmuD′ may be quite dynamic proteins. Indeed, UmuD2 and UmuD2′ were recently found to be intrinsically disordered proteins [48]. Despite the predominantly β-sheet character in the solved structures of UmuD′, the circular dichroism spectra of both UmuD′ and UmuD at physiological concentrations (5 μM) in solution are more characteristic of a random coil than of β sheets [48]. Higher concentrations of UmuD or UmuD′ (2 mM) or incubation with crowding agents or partner proteins including DinB or the β clamp induced CD spectra more characteristic of a predominantly β-sheet structure [48].

An analysis of the dynamics of UmuD using hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HXMS) found that many regions of UmuD2 were highly dynamic in solution, especially its N-terminal arms (Figure 2), consistent with previous suggestions [36, 44, 51]. In addition, the comparison of the conformations and dynamics of UmuD2 and UmuD2′ in solution by HXMS indicated that the N-terminal arm was a key factor governing the dynamics of UmuD2 and UmuD2′. In the absence of the N-terminal 24 residues in UmuD2′, regions of the globular domain likely to contact the arm underwent more exchange than in UmuD2 [51]. The predicted dimer interface of UmuD2 was the most resistant to deuteration indicating that this region is the most stable and structured part of the protein. The results of HXMS were consistent both with the proposed model of UmuD2 [52] and with the observation that UmuD2 is relatively unstructured [48].

Gas-phase hydrogen-deuterium exchange experiments, which specifically detect side-chain hydrogen exchange at msec time scales, show that when the arm is truncated, in UmuD2′, more side-chain sites can be labeled, reinforcing the idea that the arm protects part of the globular domain of the protein from interactions with solvent [51]. Therefore, the flexible N-terminal arm and the extended binding interface are potential sites for UmuD2 to interact with other partner proteins. Indeed, the β processivity clamp has been shown to interact with specific amino acids in both the N-terminal arm and the globular domain of UmuD2 [53].

Also in support of the dynamic nature of UmuD, it was found that Leu101 and Arg102 are important for proper positioning of the Ser/Lys active site dyad upon interaction with the RecA/ssDNA filament [54]. HXMS experiments showed that the peptides including these residues (89–125 and 95–128) are highly deuterated (Figure 2) [51]. Additionally, from molecular modeling experiments four distinct conformations of UmuD2 were calculated; all four were isoenergetic, suggesting that all four conformations may be physiologically relevant [52]. Thus, the flexibility of UmuD2 is likely to be a key feature governing its cleavage activity as well as interactions with its numerous protein partners.

Not only are the monomer units of UmuD and UmuD′ highly flexible, but multiple dimeric forms are also observed. Homodimers of UmuD2 and UmuD2′ readily exchange to form the UmuDD′ heterodimer, which has been found to be the most thermodynamically stable dimeric form [55]. Additionally, the X-ray structure of UmuD2′ suggested two possible dimer interfaces [46, 56]. Much biochemical data, as well as solution NMR and HXMS experiments, are consistent with the dimer interface shown in Figure 2 [45, 47, 51]. However, some experiments suggest that the other dimer interface (not shown) may also form [56]. Both dimer interfaces may be present in solution, as indicated by the observation of higher order cross-linked UmuD multimers of molecular weights consistent with tetramers and hexamers and larger complexes [28, 56]. UmuD and UmuD′ appear to be intrinsically highly dynamic proteins that can adopt multiple dimeric, and possibly higher order, forms.

5. The Interactions of the UmuD Gene Products with the α, β, and ε Subunits of DNA Polymerase III

DNA pol III is the 10-subunit complex responsible for most DNA replication in E. coli [57, 58]. Although pol III and UmuD2′C reduce the primer extension activity of each other by competing for DNA primer termini, they also appear to directly interact as UmuD2′C enhances the polymerase activity of pol III with a temperature-sensitive α protein in vitro [17, 59, 60]. UmuD2 and UmuD2′ directly interact with components of the replicative DNA polymerase III, including the α catalytic, β processivity, and ε proofreading subunits [28, 61]. The UmuD gene products display differential interactions with these components of the replisome. UmuD2 binds more strongly to the β processivity clamp than UmuD2′ does whereas UmuD2′ binds more strongly to the α polymerase subunit than UmuD2 does, which is consistent with the UmuD gene products serving temporally separate roles in coordinating the replication machinery in response to DNA damage [61].

The ε subunit possesses 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity and serves as the proofreading subunit of the replicative DNA polymerase [57]. Both UmuD2 and UmuD2′ interact with the C-terminal domain of ε, which is the same region of ε that contacts α [61–63]. The overexpression of the ε subunit suppresses umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity whereas overexpression of any of the other pol III subunits does not [62].

By far, the best characterized interactions of UmuD or UmuD′ with the replisome are the interactions between UmuD or UmuD′ and the β processivity clamp. Overexpression of the β processivity clamp exacerbates umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity, which was used as the basis of selection to identify additional sites of interaction between UmuD′, UmuC, and the β clamp [62, 64, 65]. It was suggested that the exacerbation of the cold sensitive phenotype is due to an exaggerated checkpoint response [61, 64].

UmuD2 binds to β in the vicinity of the same hydrophobic pocket region where other β-binding proteins interact [53, 66]. As the β clamp is a homodimer, it has two such interaction sites per functional protein. However, there is still likely to be a hierarchy or competition for binding to the clamp because at least eight proteins are likely to interact with the β clamp at the same site, some of which possess different affinities for the β clamp (Table 1) [66–74]. By using site-directed mutagenesis and cross-linking experiments, it was reported that UmuD2, UmuD2′, and the α catalytic subunits of Pol III share some common contacts with β, but each of these proteins possesses a different affinity for β [66]. The N-terminal region of UmuD2 contains a canonical β clamp-binding motif (14TLPLF18) (Figures 2 and 3, Table 1); this motif is used by a number of proteins to bind to the hydrophobic pocket on the β clamp (Figure 3) [67]. By constructing truncations of UmuD, it was determined that the residues between 9 and 19 are critical for interactions with the β clamp [53]. A UmuD2 variant containing mutations in the canonical β clamp interaction motif was found to bind β with the same affinity as wild-type UmuD but with a different tryptophan fluorescence emission spectrum of β [52], which indicates that the motif itself is not necessary for the interaction, but it likely indicates a conformational change in the β clamp upon UmuD binding [6]. Additionally, residues in the C-terminal globular domain of UmuD and UmuD′ are also involved in interactions with the β clamp (Figure 3) [53]. Therefore, UmuD2 interacts with the β clamp by both its N-terminal arm and C-terminal globular domain.

Table 1.

E. coli proteins that interact with the β clamp via the β-binding pentapeptide motif QL[SD]LF or similar sequence [67].

| β-interacting proteins | β-binding sequence | References |

|---|---|---|

| UmuD | 14TFPLF18 | [52, 53](1) |

| DNA Pol V (UmuC) | 357QLNLF361 | [127, 128] |

| DNA Pol IV (DinB) | 346QLVLGL351 | [68, 127, 129] |

| DNA Pol II (Pol B) | 779QLGLF783 | [127] |

| DNA Pol III (α-subunit) | 920QADMF924 | [130] |

| δ-subunit Clamp Loader | 70AMSLF74 | [131] |

| MutS | 812QMSLL816 | [132] |

| Hda | 6QLSLPL11 | [133] |

(1)Although these residues reside in an important region for interactions with the β clamp, their identity is not required for UmuD to interact with β (see text Section 5).

6. Molecular Interactions of UmuD with Y-Family DNA Polymerases UmuC and DinB

6.1. Molecular Interactions of UmuD Gene Products with UmuC

Disruptions to the umuDC operon result in nonmutability by UV, 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide (4-NQO), methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), and other agents [1–4], presumably due to the lack of TLS by pol V. Pol V has a base substitution error frequency of 10−3– 10−5 on undamaged DNA, compared to 10−4–10−6 for the replicative DNA polymerase pol III [75, 76]. Pol V copies DNA-containing lesions such as abasic sites, thymine-thymine cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers, (6-4) photoproducts, as well as the C 8-dG adduct of N-2-acetylaminofluorene, while preferentially misincorporating dG opposite the 3′ T of the thymine-thymine (6-4) photoproducts [16, 17, 59, 75, 77, 78]. This specific mutagenic bypass of the (6-4) photoproduct is a major contributor to the observed UmuC-dependent SOS mutagenesis [75, 79]. UmuC contains intrinsic DNA polymerase activity and is therefore capable of DNA synthesis on undamaged DNA, but TLS activity requires the formation of the UmuD′C complex and the presence of RecA [16, 80]. Other cofactors, including SSB and the β processivity clamp and clamp loader, also support TLS by pol V [16, 17, 59, 75, 80–86].

Whereas UmuD′ is required for TLS by UmuC, full-length UmuD does not support TLS [16, 87]. Cells expressing UmuD and UmuC at elevated levels exhibit a cold sensitive for growth phenotype that is not yet well understood [29]. Full-length UmuD also plays a role together with UmuC in inhibiting the recovery of DNA replication after UV exposure [27]. Moreover, full-length UmuD that cannot be cleaved because it harbors the S60A active site mutation causes a dramatic reduction in UV-induced mutagenesis while UmuD′-S60A shows only a modest decrease in UV-induced mutagenesis [32]. Cells expressing UmuC together with noncleavable UmuD-S60A are sensitive to UV relative to cells expressing wild-type UmuD and UmuC but are resistant to killing by UV irradiation relative to cells that are Δu m u D C [27, 52, 55]. Taken together, these findings suggest that full-length UmuD specifically prevents mutagenesis, presumably at least in part by preventing UmuC from engaging in mutagenic TLS.

Due to the difficulty in acquiring large quantities of pure, active UmuC and pol V, protein interaction studies have been somewhat limited, especially considering that the UmuC gene was identified in the 1970s. However, the physical interaction between UmuD′ and UmuC was confirmed using immunoprecipitation, yeast two-hybrid assay and glycerol gradient analysis [88, 89]. Additionally, the interaction between full-length UmuD and UmuC was verified by using affinity chromatography and velocity sedimentation in glycerol gradients, but not immunoprecipitation from cell extracts [88]. From this, it was concluded that UmuC associates strongly with UmuD′in vivo whereas, in vitro, UmuC interacts efficiently with both forms of the UmuD gene products [88]. The likely stoichiometry was determined to be one UmuC with either a dimeric UmuD or UmuD′ [88]. UmuD and UmuD′ appear to interact with the C-terminus of UmuC, as a UmuC construct lacking its C-terminal 25 residues showed dramatically reduced binding to both UmuD and UmuD′ [28]. In addition to the UmuD and UmuD′ homodimers, UmuC also interacts with the UmuDD′ heterodimer, which acts to inhibit SOS mutagenesis, possibly by titrating out the dimeric UmuD′ species that is active in TLS [88–91].

6.2. Molecular Interactions of UmuD and DinB

The dinB (damage-inducible) gene encoding DNA pol IV (DinB) was discovered in a screen using reporter fusions to identify DNA damage-inducible genes [92]. DinB (Pol IV) is the other Y-family lesion bypass polymerase in E. coli and is the only Y-family polymerase that is conserved throughout all domains of life [5, 15]. The expression level of chromosomal DinB under DNA damaging conditions is 6–12 times higher than that of UmuC or PolB (DNA pol II) with about 2500 molecules of DinB in an SOS-induced cell [25]. DinB is also found on the recombinant F′ plasmid that was constructed to determine mutation spectra of specific revertible l a c − alleles [25, 93]. The expression level of DinB in an uninduced state from the F′ plasmid in E. coli strain CC108 is approximately 750 molecules, as compared to 250 molecules expressed from the chromosome in the absence of SOS induction [25]. DinB has a misincorporation error frequency of 10−3 –10−5 [94]. Unlike UmuD′C, DinB elongates templates with bulged structures causing potentially deleterious -1 frameshift mutations [95, 96]. It was also shown that DinB and its eukaryotic ortholog Pol κ can accurately and efficiently perform TLS on templates containing N 2-deoxyguanosine (N 2-dG) adducts, suggesting that these proteins are specialized for relatively accurate TLS over some N 2-dG adducts [97–99].

UmuD, UmuD′, and RecA play important roles in the regulation of DinB, and direct physical interactions between DinB and UmuD, UmuD′, and RecA have been detected [30]. Although this may have initially seemed surprising, the expression levels of UmuD (180 molecules uninduced; 2400 molecules in SOS-induced cells) and DinB (250 molecules uninduced; 2500 molecules in SOS-induced cells) before and after SOS induction align [25, 26]. The stoichiometry of the complex was found to be one DinB molecule to one UmuD2 dimer [30]. DinB and UmuD2 bind with a K D of 0.62 μM [30]. It was also determined that DinB, RecA, and UmuD2 form a stable ternary complex under physiological conditions in vitro [30]. Genetic and biochemical analysis shows that full-length UmuD as well as the noncleavable UmuD variant UmuD S60A strongly inhibits the -1 frameshift mutator effect of DinB [30]. UmuD and UmuD′ also inhibit DinB activity in adaptive mutagenesis [30]. Presteady-state kinetics experiments led to the proposal that DinB bound to DNA containing a repetitive sequence is in equilibrium between a template slipped conformation, which leads to frameshift mutagenesis and a nonslipped conformation [100]. UmuD appears to prevent DinB-dependent frameshift mutagenesis by favoring the nonslipped conformation upon binding to DinB [100]. UmuD also modulates DinB function by facilitating efficient extension of correctly paired primer termini while blocking extension of mismatched termini [30, 100].

Using peptide array mapping and structural homology models of both DinB and UmuD, it was proposed that UmuD interacts with several hydrophobic residues on the surface of DinB in the thumb and finger domains. DinB residue F172 in the thumb domain was identified as a likely site of interaction with UmuD. Indeed, DinB F172A has lower affinity for UmuD (K D reduced ~56-fold) and exhibits less UmuD-dependent -1 frameshift suppression in vivo and in vitro than wild-type DinB [30]. The DinB interacting surface on UmuD is a discontinuous surface when mapped onto a model of trans-UmuD [47, 52]. Alternatively, isoenergetic models of UmuD in which the N-terminal arms are in a noncleavable conformation provide alternative interacting surfaces across the side of UmuD [52]. UmuD D91, on the outer surface of UmuD, was proposed as a likely residue to be important for interaction with DinB (Figure 3). UmuD D91A has reduced affinity for DinB (K D reduced by over 24-fold) and dramatically reduced suppression of -1 frameshift mutagenesis compared to wild-type UmuD [30]. This suggests that there may be multiple biologically relevant conformations of UmuD that can interact with DinB or other polymerases [48, 51, 52, 101]. These interactions may aid in the suppression of frameshift mutagenesis by blocking the open active site that is needed to elongate bulged templates [13, 14, 30, 102]. By creating a ternary complex model of DinB, UmuD2, and RecA, it was suggested that UmuD2 and RecA work together in restricting the open active site of DinB thereby preventing -1 frameshift mutagenesis on bulged templates [30, 100]. Therefore, the presence of full-length UmuD actually enhances accurate TLS by DinB while suppressing extension of bulged templates that would cause frameshift mutagenesis.

7. Molecular Interactions of UmuD and UmuD′ with Lon and ClpXP Proteases

Regulation of UmuD protein levels by ClpXP and Lon proteases is an important part of the SOS response to DNA damage. Proteolytic degradation of the UmuD gene products is involved in cessation of SOS mutagenesis [4, 103, 104]. ClpXP is composed of the ATP-dependent unfoldase ClpX hexamer and the double-ringed, 14-subunit serine protease, ClpP [105–109]. The domain structure of the Lon protease is quite similar in that it contains an ATPase domain, a sensor and substrate discrimination domain (SSD), and a protease domain [110]. The mechanism of degradation begins when ClpX unfolds the substrates using repeated cycles of ATP hydrolysis and translocates the unfolded peptide into the ClpP chamber where proteolysis occurs. Substrate recognition involves the N- or C-terminal regions of the target protein binding to the substrate-processing site on ClpX [111, 112]. These signals may become apparent after cleavage, as in the case of LexA, or upon a conformational change in the target protein [113, 114]. However, the addition of an 11-amino acid (AANDENYALAA) ssrA tag to improperly translated nascent polypeptides will result in direct targeting to ClpXP for degradation [107, 108, 115–118]. This C-terminal ssrA tag is encoded by the ssrA transfer mRNA and is added cotranslationally to proteins translated without an in-frame stop codon [117, 118]. In addition, substrate recognition by ClpXP involves the interaction of tethering sites with adaptor proteins. These adaptor proteins are not degraded themselves but work to enhance the degradation of the target protein [119, 120]. One example is the SspB-mediated degradation of ssrA-tagged protein. Here, one part of the target protein binds the tethering site on ClpX while the SspB protein interacts with the ssrA tag enabling efficient delivery to ClpXP for degradation [121, 122].

Similar to SspB-facilitated degradation of ssrA-tagged target proteins, UmuD′ is a substrate for ClpXP but is only degraded when bound to full-length UmuD [123, 124]. Therefore, the preferential formation of UmuDD′ heterodimer specifically leads to a decrease in the steady-state levels of UmuD′in vivo [123]. Although the residues found within the N-terminal 24 amino acids of UmuD serve as the degradation signal for ClpXP degradation of UmuD′, UmuD serves as an adaptor and is not itself degraded [124]. UmuD also serves as an adaptor in the context of UmuD2 homodimers, leading to degradation of one UmuD in the dimer [123]. UmuD residues 9–12 are necessary for UmuD′ instability and therefore protease recognition (Figure 3) [124]. Amino acids 15–19 of UmuD are also implicated in the degradation of the UmuDD′ heterodimer by ClpXP (Figure 3) [124]. On the other hand, while residues 15–19 are also important for Lon-mediated degradation of UmuD, residues 9–12 are not involved in recognition by Lon [125]. ClpXP recognition sites can also be found on the surface of UmuD′, in particular, residues 33–37, 41–51, and 85–109 were found to interact robustly with ClpXP (Figure 3) [124]. The UmuD-facilitated degradation of UmuD′ can be impeded by the SspB-tethering peptide, and the SspB-tethering motif is interchangeable with the sequence in UmuD. Because the N-terminal domain of ClpX mediates interactions with both SspB and UmuD, it was determined that UmuD acts as a ClpX delivery factor that is critical in tethering itself and UmuD′ to ClpX. This seems to be a primary mechanism for bringing SOS mutagenesis to an end [126].

8. Conclusions

Although the UmuD gene was discovered over 30 years ago, new findings regarding how the UmuD gene products regulate mutagenesis have been made even within the last few years. This is despite the fact that there is still no high-resolution structure of full-length UmuD. The extremely dynamic nature of UmuD and UmuD′ has only recently come to light and provides insights into the large number of specific protein interactions of which the UmuD gene products are capable. Because of the role of UmuD in regulating mutagenesis, it could be important in bacterial evolution and is therefore potentially an important drug target.

Acknowledgments

Jaylene N. Ollivierre and Jing Fang contributed equally in this work. The authors are pleased to acknowledge generous financial support from a New Faculty Award from the Camille & Henry Dreyfus Foundation (PJB), the NSF (CAREER Award, MCB-0845033 to PJB), and the NU Office of the Provost (PJB). P. J. Beuning is a Cottrell Scholar of the Research Corporation for Science Advancement.

References

- 1.Bagg A, Kenyon CJ, Walker GC. Inducibility of a gene product required for UV and chemical mutagenesis in Escherichia coli . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1981;78(9):5749–5753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.9.5749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kato T, Shinoura Y. Isolation and characterization of mutants of Escherichia coli deficient in induction of mutations by ultraviolet light. Molecular and General Genetics. 1977;156(2):121–131. doi: 10.1007/BF00283484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinborn G. Uvm mutants of Escherichia coli K12 deficient in UV mutagenesis. I. Isolation of uvm mutants and their phenotypical characterization in DNA repair and mutagenesis. Molecular and General Genetics. 1978;165(1):87–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00270380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD, Schultz RA, Ellenberger T. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. 2nd edition. Washington, DC, USA: ASM Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohmori H, Friedberg EC, Fuchs RPP, et al. The Y-family of DNA polymerases. Molecular Cell. 2001;8(1):7–8. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarosz DF, Beuning PJ, Cohen SE, Walker GC. Y-family DNA polymerases in Escherichia coli . Trends in Microbiology. 2007;15(2):70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlacher K, Goodman MF. Lessons from 50 years of SOS DNA-damage-induced mutagenesis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2007;8(7):587–594. doi: 10.1038/nrm2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang W, Woodgate R. What a difference a decade makes: insights into translesion DNA synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(40):15591–15598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704219104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maor-Shoshani A, Reuven NB, Tomer G, Livneh Z. Highly mutagenic replication by DNA polymerase V (UmuC) provides a mechanistic basis for SOS untargeted mutagenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(2):565–570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCulloch SD, Kunkel TA. The fidelity of DNA synthesis by eukaryotic replicative and translesion synthesis polymerases. Cell Research. 2008;18(1):148–161. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi S, Valentine MR, Pham P, O’Donnell M, Goodman MF. Fidelity of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase IV: preferential generation of small deletion mutations by dNTP-stabilized misalignment. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(37):34198–34207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Washington MT, Carlson KD, Freudenthal BD, Pryor JM. Variations on a theme: eukaryotic Y-family DNA polymerases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2010;1804(5):1113–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang W. Damage repair DNA polymerases Y. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2003;13(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang W. Portraits of a Y-family DNA polymerase. FEBS Letters. 2005;579(4):868–872. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner J, Gruz P, Kim S-R, et al. The dinB gene encodes a novel E. coli DNA polymerase, DNA pol IV, involved in mutagenesis. Molecular Cell. 1999;4(2):281–286. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reuven NB, Arad G, Maor-Shoshani A, Livneh Z. The mutagenesis protein UmuC is a DNA polymerase activated by UmuD′, RecA, and SSB and is specialized for translesion replication. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(45):31763–31766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.31763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang M, Shen X, Frank EG, O’Donnell M, Woodgate R, Goodman MF. UmuD′2C is an error-prone DNA polymerase, Escherichia coli pol V. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(16):8919–8924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elledge SJ, Walker GC. Proteins required for ultraviolet light and chemical mutagenesis: identification of the products of the umuC locus of Escherichia coli . Journal of Molecular Biology. 1983;164(2):175–192. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(83)90074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shinagawa H, Kato T, Ise T, Makino K, Nakata A. Cloning and characterization of the umu operon responsible for inducible mutagenesis in Escherichia coli . Gene. 1983;23(2):167–174. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simmons LA, Foti JJ, Cohen SE, Walker GC. The SOS regulatory network. In: Bock A III, Kaper RC, Karp JB, et al., editors. EcoSal–Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. chapter 5.4.3. Washington, DC, USA: ASM Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Courcelle J, Khodursky A, Peter B, Brown PO, Hanawalt PC. Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS-deficient Escherichia coli . Genetics. 2001;158(1):41–64. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sassanfar M, Roberts JW. Nature of the SOS-inducing signal in Escherichia coli. The involvement of DNA replication. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1990;212(1):79–96. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90306-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Little JW. Autodigestion of lexA and phage λ repressors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1984;81(3):1375–1379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neher SB, Flynn JM, Sauer RT, Baker TA. Latent ClpX-recognition signals ensure LexA destruction after DNA damage. Genes and Development. 2003;17(9):1084–1089. doi: 10.1101/gad.1078003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim S-R, Matsui K, Yamada M, Gruz P, Nohmi T. Roles of chromosomal and episomal dinB genes encoding DNA pol IV in targeted and untargeted mutagenesis in Escherichia coli . Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2001;266(2):207–215. doi: 10.1007/s004380100541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woodgate R, Ennis DG. Levels of chromosomally encoded Umu proteins and requirements for in vivo UmuD cleavage. Molecular and General Genetics. 1991;229(1):10–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00264207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Opperman T, Murli S, Smith BT, Walker GC. A model for a umuDC-dependent prokaryotic DNA damage checkpoint. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(16):9218–9223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutton MD, Walker GC. umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity is a manifestation of functions of the UmuD2C complex involved in a DNA damage checkpoint control. Journal of Bacteriology. 2001;183(4):1215–1224. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1215-1224.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marsh L, Walker GC. Cold sensitivity induced by overproduction of UmuDC in Escherichia coli . Journal of Bacteriology. 1985;162(1):155–161. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.1.155-161.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Godoy VG, Jarosz DF, Simon SM, Abyzov A, Ilyin V, Walker GC. UmuD and RecA directly modulate the mutagenic potential of the Y family DNA polymerase dinB . Molecular Cell. 2007;28(6):1058–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shinagawa H, Iwasaki H, Kato T, Nakata A. RecA protein-dependent cleavage of UmuD protein and SOS mutagenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85(6):1806–1810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nohmi T, Battista JR, Dodson LA, Walker GC. RecA-mediated cleavage activates UmuD for mutagenesis: mechanistic relationship between transcriptional derepression and posttranslational activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85(6):1816–1820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burckhardt SE, Woodgate R, Scheuermann RH, Echols H. UmuD mutagenesis protein of Escherichia coli: overproduction, purification, and cleavage by RecA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85(6):1811–1815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paetzel M, Strynadka NCJ. Common protein architecture and binding sites in proteases utilizing a Ser/Lys dyad mechanism. Protein Science. 1999;8(11):2533–2536. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.11.2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slilaty SN, Rupley JA, Little JW. Intramolecular cleavage of LexA and phage λ repressors: dependence of kinetics on repressor concentration, pH, temperature, and solvent. Biochemistry. 1986;25(22):6866–6875. doi: 10.1021/bi00370a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDonald JP, Peat TS, Levine AS, Woodgate R. Intermolecular cleavage by UmuD-like enzymes: identification of residues required for cleavage and substrate specificity. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1999;285(5):2199–2209. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonald JP, Frank EG, Levine AS, Woodgate R. Intermolecular cleavage by UmuD-like mutagenesis proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(4):1478–1483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDonald JP, Maury EE, Levine AS, Woodgate R. Regulation of UmuD cleavage: role of the amino-terminal tail. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1998;282(4):721–730. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruck I, Woodgate R, McEuntee K, Goodman MF. Purification of a soluble UmuD′C complex from Escherichia coli: cooperative binding of UmuD′C to single-stranded DNA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(18):10767–10774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodgate R, Rajagopalan M, Lu C, Echols H. UmuC mutagenesis protein of Escherichia coli: purification and interaction with UmuD and UmuD′. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86(19):7301–7305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rehrauer WM, Lavery PE, Palmer EL, Singh RN, Kowalczykowskit SC. Interaction of Escherichia coli RecA protein with LexA repressor. I. LexA repressor cleavage is competitive with binding of a secondary DNA molecule. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(39):23865–23873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sommer S, Bailone A, Devoret R. The appearance of the UmuD′C protein complex in Escherichia coli switches repair from homologous recombination to SOS mutagenesis. Molecular Microbiology. 1993;10(5):963–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szpilewska H, Bertrand P, Bailone A, Dutreix M. In vitro inhibition of RecA-mediated homologous pairing by UmuD′C proteins. Biochimie. 1995;77(11):848–853. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(95)90002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferentz AE, Walker GC, Wagner G. Converting a DNA damage checkpoint effector (UmuD2C) into a lesion bypass polymerase (UmuD′2C) EMBO Journal. 2001;20(15):4287–4298. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferentz AE, Opperman T, Walker GC, Wagner G. Dimerization of the UmuD′ protein in solution and its implications for regulation of SOS mutagenesis. Nature Structural Biology. 1997;4(12):979–983. doi: 10.1038/nsb1297-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peat TS, Frank EG, McDonald JP, Levine AS, Woodgate R, Hendrickson WA. Structure of the UmuD′ protein and its regulation in response to DNA damage. Nature. 1996;380(6576):727–730. doi: 10.1038/380727a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sutton MD, Guzzo A, Narumi I, et al. A model for the structure of the Escherichia coli SOS-regulated UmuD2 protein. DNA Repair. 2002;1(1):77–93. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(01)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simon SM, Sousa FJR, Mohana-Borges R, Walker GC. Regulation of Escherichia coli SOS mutagenesis by dimeric intrinsically disordered umuD gene products. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(4):1152–1157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706067105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee MH, Walker GC. Interactions of Escherichia coli UmuD with activated RecA analyzed by cross-linking UmuD monocysteine derivatives. Journal of Bacteriology. 1996;178(24):7285–7294. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7285-7294.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frank EG, Cheng N, Do CC, et al. Visualization of two binding sites for the Escherichia coli UmuD′2C complex (DNA pol V) on RecA-ssDNA filaments. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2000;297(3):585–597. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fang J, Rand KD, Silva MC, Wales TE, Engen JR, Beuning PJ. Conformational dynamics of the Escherichia coli DNA polymerase manager proteins UmuD and UmuD′. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2010;398(1):40–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beuning PJ, Simon SM, Zemla A, Barsky D, Walker GC. A non-cleavable UmuD variant that acts as a UmuD′ mimic. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(14):9633–9640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sutton MD, Narumi I, Walker GC. Posttranslational modification of the umuD-encoded subunit of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase V regulates its interactions with the β processivity clamp. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(8):5307–5312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082322099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sutton MD, Kim M, Walker GC. Genetic and biochemical characterization of a novel umuD mutation: insights into a mechanism for UmuD self-cleavage. Journal of Bacteriology. 2001;183(1):347–357. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.1.347-357.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Battista JR, Ohta T, Nohmi T, Sun W, Walker GC. Dominant negative umuD mutations decreasing RecA-mediated cleavage suggest roles for intact UmuD in modulation of SOS mutagenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87(18):7190–7194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peat TS, Frank EG, McDonald JP, Levine AS, Woodgate R, Hendrickson WA. The UmuD′ protein filament and its potential role in damage induced mutagenesis. Structure. 1996;4(12):1401–1412. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kelman Z, O’Donnell M. DNA polymerase III holoenzyme: structure and function of a chromosomal replicating machine. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1995;64:171–200. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.001131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McHenry CS. Chromosomal replicases as asymmetric dimers: studies of subunit arrangement and functional consequences. Molecular Microbiology. 2003;49(5):1157–1165. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fujii S, Gasser V, Fuchs RP. The biochemical requirements of DNA polymerase V-mediated translesion synthesis revisited. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2004;341(2):405–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fujii S, Isogawa A, Fuchs RP. RecFOR proteins are essential for Pol V-mediated translesion synthesis and mutagenesis. EMBO Journal. 2006;25(24):5754–5763. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sutton MD, Opperman T, Walker GC. The Escherichia coli SOS mutagenesis proteins UmuD and UmuD′ interact physically with the replicative DNA polymerase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(22):12373–12378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sutton MD, Murli S, Opperman T, Klein C, Walker GC. umuDC-dnaQ interaction and its implications for cell cycle regulation and SOS mutagenesis in Escherichia coli . Journal of Bacteriology. 2001;183(3):1085–1089. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.3.1085-1089.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taft-Benz SA, Schaaper RM. The C-terminal domain of DnaQ contains the polymerase binding site. Journal of Bacteriology. 1999;181(9):2963–2965. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.9.2963-2965.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sutton MD, Farrow MF, Burton BM, Walker GC. Genetic interactions between the Escherichia coli umuDC gene products and the β processivity clamp of the replicative DNA polymerase. Journal of Bacteriology. 2001;183(9):2897–2909. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.9.2897-2909.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beuning PJ, Chan S, Waters LS, Addepalli H, Ollivierre JN, Walker GC. Characterization of novel alleles of the Escherichia coli umuDC genes identifies additional interaction sites of UmuC with the beta clamp. Journal of Bacteriology. 2009;191(19):5910–5920. doi: 10.1128/JB.00292-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Duzen JM, Walker GC, Sutton MD. Identification of specific amino acid residues in the E. coli β processivity clamp involved in interactions with DNA polymerase III, UmuD and UmuD′. DNA Repair. 2004;3(3):301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dalrymple BP, Kongsuwan K, Wijffels G, Dixon NE, Jennings PA. A universal protein-protein interaction motif in the eubacterial DNA replication and repair systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(20):11627–11632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191384398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Burnouf DY, Olieric V, Wagner J, et al. Structural and biochemical analysis of sliding clamp/ligand interactions suggest a competition between replicative and translesion DNA polymerases. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2004;335(5):1187–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Heltzel JMH, Maul RW, Scouten Ponticelli SK, Sutton MD. A model for DNA polymerase switching involving a single cleft and the rim of the sliding clamp. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(31):12664–12669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903460106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heltzel JMH, Scouten Ponticelli SK, Sanders LH, et al. Sliding clamp-DNA interactions are required for viability and contribute to DNA polymerase management in Escherichia coli . Journal of Molecular Biology. 2009;387(1):74–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Maul RW, Scouten Ponticelli SK, Duzen JM, Sutton MD. Differential binding of Escherichia coli DNA polymerases to the β-sliding clamp. Molecular Microbiology. 2007;65(3):811–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scouten Ponticelli SK, Duzen JM, Sutton MD. Contributions of the individual hydrophobic clefts of the Escherichia coli β sliding clamp to clamp loading, DNA replication and clamp recycling. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37(9):2796–2809. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sutton MD, Duzen JM. Specific amino acid residues in the β sliding clamp establish a DNA polymerase usage hierarchy in Escherichia coli . DNA Repair. 2006;5(3):312–323. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wijffels G, Dalrymple BP, Prosselkov P, et al. Inhibition of protein interactions with the β 2 sliding clamp of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase III by peptides from β 2-binding proteins. Biochemistry. 2004;43(19):5661–5671. doi: 10.1021/bi036229j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tang M, Pham P, Shen X, et al. Roles of E. coli DNA polymerases IV and V in lesion-targeted and untargeted SOS mutagenesis. Nature. 2000;404(6781):1014–1018. doi: 10.1038/35010020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bloom LB, Chen X, Fygenson DK, Turner J, O’Donnell M, Goodman MF. Fidelity of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase III holoenzyme: the effects of β, γ complex processivity proteins and ε proofreading exonuclease on nucleotide misincorporation efficiencies. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(44):27919–27930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reuven NB, Tomer G, Livneh Z. The mutagenesis proteins UmuD′ and UmuC prevent lethal frameshifts while increasing base substitution mutations. Molecular Cell. 1998;2(2):191–199. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fujii S, Fuchs RP. Defining the position of the switches between replicative and bypass DNA polymerases. EMBO Journal. 2004;23(21):4342–4352. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Becherel OJ, Fuchs RPP. SOS mutagenesis results from up-regulation of translesion synthesis. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1999;294(2):299–306. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schlacher K, Leslie K, Wyman C, Woodgate R, Cox MM, Goodman MF. DNA polymerase V and RecA protein, a minimal mutasome. Molecular Cell. 2005;17(4):561–572. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schlacher K, Cox MM, Woodgate R, Goodman MF. RecA acts in trans to allow replication of damaged DNA by DNA polymerase V. Nature. 2006;442(7105):883–887. doi: 10.1038/nature05042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Maor-Shoshani A, Livneh Z. Analysis of the stimulation of DNA polymerase V of Escherichia coli by processivity proteins. Biochemistry. 2002;41(48):14438–14446. doi: 10.1021/bi0262909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reuven NB, Arad G, Stasiak AZ, Stasiak A, Livneh Z. Lesion bypass by the Escherichia coli DNA polymerase V requires assembly of a RecA nucleoprotein filament. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(8):5511–5517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006828200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pham P, Seitz EM, Saveliev S, et al. Two distinct modes of RecA action are required for DNA polymerase V-catalyzed translesion synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(17):11061–11066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172197099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jiang Q, Karata K, Woodgate R, Cox MM, Goodman MF. The active form of DNA polymerase v is UmuD′ 2 C-RecA-ATP. Nature. 2009;460(7253):359–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Arad G, Hendel A, Urbanke C, Curth U, Livneh Z. Single-stranded DNA-binding protein recruits DNA polymerase V to primer termini on RecA-coated DNA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(13):8274–8282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rajagopalan M, Lu C, Woodgate R, O’Donnell M, Goodman MF, Echols H. Activity of the purified mutagenesis proteins UmuC, UmuD′, and RecA in replicative bypass of an abasic DNA lesion by DNA polymerase III. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89(22):10777–10781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Woodgate R, Rajagopalan M, Lu C, Echols H. UmuC mutagenesis protein of Escherichia coli: purification and interaction with UmuD and UmuD′. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86(19):7301–7305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jonczyk P, Nowicka A. Specific in vivo protein-protein interactions between Escherichia coli SOS mutagenesis proteins. Journal of Bacteriology. 1996;178(9):2580–2585. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2580-2585.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rajagopalan M, Lu C, Woodgate R, O’Donnell M, Goodman MF, Echols H. Activity of the purified mutagenesis proteins UmuC, UmuD′, and RecA in replicative bypass of an abasic DNA lesion by DNA polymerase III. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89(22):10777–10781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bruck I, Woodgate R, McEuntee K, Goodman MF. Purification of a soluble UmuD′C complex from Escherichia coli: cooperative binding of UmuD′C to single-stranded DNA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(18):10767–10774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kenyon CJ, Walker GC. DNA-damaging agents stimulate gene expression at specific loci in Escherichia coli . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1980;77(5):2819–2823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Strauss BS, Roberts R, Francis L, Pouryazdanparast P. Role of the dinB gene product in spontaneous mutation in Escherichia coli with an impaired replicative polymerase. Journal of Bacteriology. 2000;182(23):6742–6750. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.23.6742-6750.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kobayashi S, Valentine MR, Pham P, O’Donnell M, Goodman MF. Fidelity of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase IV. Preferential generation of small deletion mutations by dNTP-stabilized misalignment. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(37):34198–34207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wagner J, Gruz P, Kim S-R, et al. The dinB gene encodes a novel E. coli DNA polymerase, DNA pol IV, involved in mutagenesis. Molecular Cell. 1999;4(2):281–286. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kim S-R, Matsui K, Yamada M, Gruz P, Nohmi T. Roles of chromosomal and episomal dinB genes encoding DNA pol IV in targeted and untargeted mutagenesis in Escherichia coli . Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2001;266(2):207–215. doi: 10.1007/s004380100541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jarosz DF, Godoy VG, Delaney JC, Essigmann JM, Walker GC. A single amino acid governs enhanced activity of dinB DNA polymerases on damaged templates. Nature. 2006;439(7073):225–228. doi: 10.1038/nature04318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Napolitano R, Janel-Bintz R, Wagner J, Fuchs RPP. All three SOS-inducible DNA polymerases (Pol II, Pol IV and Pol V) are involved in induced mutagenesis. EMBO Journal. 2000;19(22):6259–6265. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.22.6259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lenne-Samuel N, Janel-Bintz R, Kolbanovskiy A, Geacintov NE, Fuchs RPP. The processing of a Benzo(a)pyrene adduct into a frameshift or a base substitution mutation requires a different set of genes in Escherichia coli . Molecular Microbiology. 2000;38(2):299–307. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Foti JJ, DeLucia AM, Joyce CM, Walker GC. UmuD2 inhibits a non-covalent step during dinB-mediated template slippage on homopolymeric nucleotide runs. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(30):23086–23095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.115774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Beuning PJ, Simon SM, Godoy VG, Jarosz DF, Walker GC. Characterization of Escherichia coli translesion synthesis polymerases and their accessory factors. Methods in Enzymology. 2006;408:318–340. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)08020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ling H, Boudsocq F, Woodgate R, Yang W. Crystal structure of a Y-family DNA polymerase in action: a mechanism for error-prone and lesion-bypass replication. Cell. 2001;107(1):91–102. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00515-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gonzalez M, Woodgate R. The “tale” of umuD and its role in SOS mutagenesis. BioEssays. 2002;24(2):141–148. doi: 10.1002/bies.10040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Frank EG, Ennis DG, Gonzalez M, Levine AS, Woodgate R. Regulation of SOS mutagenesis by proteolysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(19):10291–10296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gottesman S, Clark WP, De Crecy-Lagard V, Maurizi MR. ClpX, an alternative subunit for the ATP-dependent Clp protease of Escherichia coli. Sequence and in vivo activities. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268(30):22618–22626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Maurizi MR, Clark WP, Katayama Y, et al. Sequence and structure of Clp P, the proteolytic component of the ATP-dependent Clp protease of Escherichia coli . Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265(21):12536–12545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kim Y-I, Burton RE, Burton BM, Sauer RT, Baker TA. Dynamics of substrate denaturation and translocation by the ClpXP degradation machine. Molecular Cell. 2000;5(4):639–648. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Singh SK, Grimaud R, Hoskins JR, Wickner S, Maurizi MR. Unfolding and internalization of proteins by the ATP-dependent proteases ClpXP and ClpAP. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(16):8898–8903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang J, Hartling JA, Flanagan JM. The structure of ClpP at 2.3 Å resolution suggests a model for ATP-dependent proteolysis. Cell. 1997;91(4):447–456. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80431-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Smith CK, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Lon and Clp family proteases and chaperones share homologous substrate-recognition domains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(12):6678–6682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gonciarz-Swiatek M, Wawrzynow A, Um S-J, et al. Recognition, targeting, and hydrolysis of the λ O replication protein by the ClpP/ClpX protease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(20):13999–14005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Flynn JM, Neher SB, Kim Y-I, Sauer RT, Baker TA. Proteomic discovery of cellular substrates of the ClpXP protease reveals five classes of ClpX-recognition signals. Molecular Cell. 2003;11(3):671–683. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Marshall-Batty KR, Nakai H. trans-targeting of the phage Mu repressor is promoted by conformational changes that expose its ClpX recognition determinant. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(3):1612–1617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Neher SB, Flynn JM, Sauer RT, Baker TA. Latent ClpX-recognition signals ensure LexA destruction after DNA damage. Genes and Development. 2003;17(9):1084–1089. doi: 10.1101/gad.1078003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Burton BM, Williams TL, Baker TA. ClpX-mediated remodeling of Mu transpososomes: selective unfolding of subunits destabilizes the entire complex. Molecular Cell. 2001;8(2):449–454. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kenniston JA, Baker TA, Fernandez JM, Sauer RT. Linkage between ATP consumption and mechanical unfolding during the protein processing reactions of an AAA+ degradation machine. Cell. 2003;114(4):511–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00612-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Karzai AW, Roche ED, Sauer RT. The SsrA-SmpB system for protein tagging, directed degradation and ribosome rescue. Nature Structural Biology. 2000;7(6):449–455. doi: 10.1038/75843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Dulebohn D, Choy J, Sundermeier T, Okan N, Karzai AW. Trans-translation: the tmRNA-mediated surveillance mechanism for ribosome rescue, directed protein degradation, and nonstop mRNA decay. Biochemistry. 2007;46(16):4681–4693. doi: 10.1021/bi6026055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Levchenko I, Grant RA, Wah DA, Sauer RT, Baker TA. Structure of a delivery protein for an AAA+ protease in complex with a peptide degradation tag. Molecular Cell. 2003;12(2):365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Levchenko I, Seidel M, Sauer RT, Baker TA. A specificity-enhancing factor for the ClpXP degradation machine. Science. 2000;289(5488):2354–2356. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wah DA, Levchenko I, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Characterization of a specificity factor for an AAA+ ATPase: assembly of SspB dimers with ssrA-tagged proteins and the ClpX hexamer. Chemistry and Biology. 2002;9(11):1237–1245. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wah DA, Levchenko I, Rieckhof GE, Bolon DN, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Flexible linkers leash the substrate binding domain of SspB to a peptide module that stabilizes delivery complexes with the AAA+ ClpXP protease. Molecular Cell. 2003;12(2):355–363. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Neher SB, Sauer RT, Baker TA. Distinct peptide signals in the UmuD and UmuD′ subunits of UmuD/D′ mediate tethering and substrate processing by the ClpXP protease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(23):13219–13224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235804100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gonzalez M, Rasulova F, Maurizi MR, Woodgate R. Subunit-specific degradation of the UmuD/D′ heterodimer by the ClpXP protease: the role of trans recognition in UmuD′ stability. EMBO Journal. 2000;19(19):5251–5258. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gonzalez M, Frank EG, Levine AS, Woodgate R. Lon-mediated proteolysis of the Escherichia coli UmuD mutagenesis protein: in vitro degradation and identification of residues required for proteolysis. Genes and Development. 1998;12(24):3889–3899. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sutton MD. Damage signals triggering the Escherichia coli SOS response. In: Wolfram Seide YWK, Doetsch PW, editors. DNA Damage and Recognition. New York, NY, USA: Taylor & Francis; 2006. pp. 781–802. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Becherel OJ, Fuchs RPP, Wagner J. Pivotal role of the β-clamp in translesion DNA synthesis and mutagenesis in E. coli cells. DNA Repair. 2002;1(9):703–708. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Beuning PJ, Sawicka D, Barsky D, Walker GC. Two processivity clamp interactions differentially alter the dual activities of UmuC. Molecular Microbiology. 2006;59(2):460–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Bunting KA, Roe SM, Pearl LH. Structural basis for recruitment of translesion DNA polymerase Pol IV/dinB to the β-clamp. EMBO Journal. 2003;22(21):5883–5892. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Dohrmann PR, McHenry CS. A bipartite polymerase-processivity factor interaction: only the internal β binding site of the α subunit is required for processive replication by the DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2005;350(2):228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Jeruzalmi D, Yurieva O, Zhao Y, et al. Mechanism of processivity clamp opening by the delta subunit wrench of the clamp loader complex of E. coli DNA polymerase III. Cell. 2001;106(4):417–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.López de Saro FJ, O’Donnell M. Interaction of the β sliding clamp with MutS, ligase, and DNA polymerase I. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(15):8376–8380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121009498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kurz M, Dalrymple B, Wijffels G, Kongsuwan K. Interaction of the sliding clamp β-subunit and Hda, a DnaA-related protein. Journal of Bacteriology. 2004;186(11):3508–3515. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.11.3508-3515.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]