Abstract

Objective

We investigated the hypothesis that partner-specific characteristics are important to improve an individual's risk characterization.

Design

It has been shown that the egocentric network structure is important to establish a person's risk for infection.

Methods

The study was cross-sectional in its design and enrolled 1231 volunteers at one HIV testing site in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and applied an adapted ego-network questionnaire. Each individual was interviewed about their own risk factors and those related to up to 10 sex partners. We used the dyadic data analysis method in which each relationship forms a record. Two receiver operator characteristic curves were generated, and the ability to correctly predict volunteers' HIV serostatus based on a model with characteristics of volunteers and sex partners and another with only volunteers' characteristics was evaluated.

Results

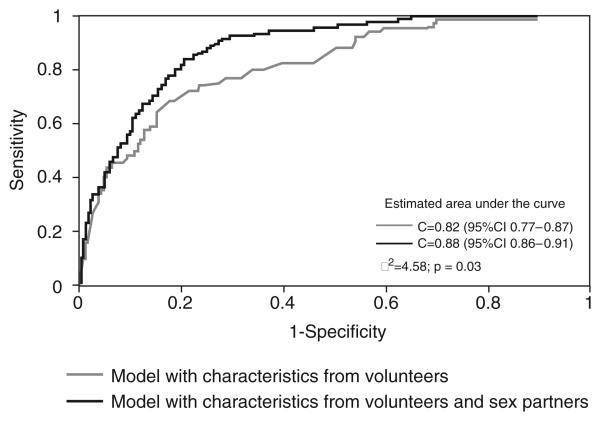

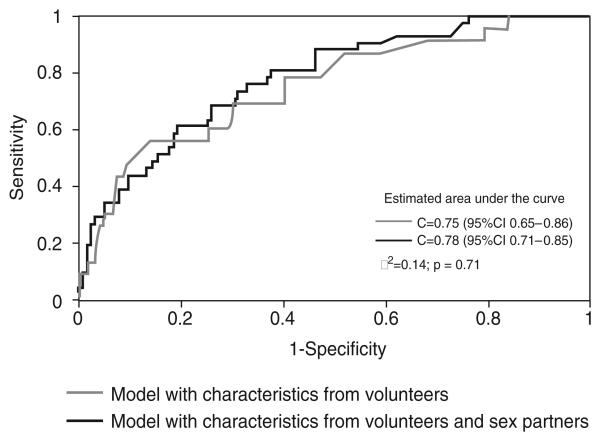

Partner-related variables were associated with HIV serostatus both for men and women. The model with volunteer/sex partners' characteristics performed better in discriminating between HIV-positive and negative volunteers only for men but not for women. The c statistic for men volunteers was 0.82 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.77–0.87] for the volunteer alone model and 0.88 (95% CI 0.86–0.91) for the combined model (P = 0.03). The values for women were 0.75 (95% CI 0.65–0.86) and 0.78 (95% CI 0.71–0.85), respectively (P = 0.71).

Conclusion

Ego-network theory-based approaches provide additional information for characterizing risk for HIV infection among men.

Keywords: AIDS, Brazil, epidemiology, HIV, risk, social network

Introduction

The WHO estimates that, by the end of 2007, approximately 33 million (30.3–36.1 million) people were living with HIV [1]. In Brazil, 506 499 cumulative AIDS cases were reported from 1980 to June 2008 [2]. In Rio de Janeiro, the second largest city in Brazil, 40 090 AIDS cases were reported from 1982 to October 2008 [3]. Most transmission of HIV/AIDS in the Brazilian epidemic is attributed to heterosexual relationships.

Epidemiologic studies of HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have traditionally focused on individual risk factors. As HIV/STI depends on intimate contact to propagate, it is reasonable to believe that inclusion of characteristics about an individual's network of contacts may be valuable for predicting risk of infection. Social network analysis examines a set of individuals or groups connected by links that represent relationships, such as friendships, or interactions, such as sexual networks [4]. Personal or local networks are made up of egos (the main study participants) and alters (those with whom the egos interact) forming egos' neighborhoods. The concept of neighborhood in social network is derived from the graphic theory used by mathematicians in which two points connected by a line are called adjacent to one another, and all points to which a particular point is adjacent are called its neighborhood [5]. Information can be gathered from egos about their demographics, risk factors and other variables. Similar information can also be obtained from ego about their partners. Neighborhood risk has been linked to an individual risk for acquiring an infection in a number of studies [6-10].

We investigated the hypothesis that partner-specific characteristics are important to improve individual risk characterization for HIV infection in Brazil.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted from June 2005 to July 2006 at the HIV Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT) site located at the Hospital Escola São Francisco (HESFA), Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Approximately 5000 individuals are tested every year at the VCT. The VCT develops several activities with its clients such as group workshops, individual interviews and testing for HIV, hepatitis B and syphilis. HIV test results are available on an average 25 days after the first visit. On the basis of routinely collected data, roughly half of the people attending the VCT site are women (51.2%) and about 11% are MSM. Approximately 43% of the VCT population is married and 51.2% have 8–11 years of education. The main reasons that individuals report for going to the VCT site for HIV testing are concern about a possible exposure (56.5%) and prenatal care (11.9%). The most important risk exposure is a sexual relationship (90%), and about 85% of the VCT clients report fewer than four partners in the past year. Overall prevalence of HIV is about 8%.

Design, recruitment and eligibility

Our goal with this cross-sectional study was to interview approximately 100 HIV-positive volunteers. On the basis of the HIV prevalence at the VCT, we anticipated a total sample size of 1250 people. Study volunteers were selected from people attending the VCT site for the first time and not aware of their HIV status. Two persons were responsible for interviewing the volunteers, one of each sex. Interviews were performed either before or after the VCT group counseling, according to the volunteer's indication. Interviewers and volunteers were blinded to the participants' HIV status.

We excluded volunteers younger than 18 years old, those already known to be HIV positive, people with no history of regular or casual sexual relationships in the previous year, pregnant women and volunteers scoring more than 10 in modified Caracas criteria [11]. The Caracas definition is used in the Brazilian case definition for AIDS and presents a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 91% without serology. The diagnosis is presumptive if the total score is greater or equal to 10 with no serology result.

Data collection

All participants responded to a questionnaire to gather ego-network data, adapted to the Brazilian context in a prior pilot study. The questionnaire collected information on each participant's demographic markers, such as age, sex, race and socio-economic level, medical history, such as past history of STI other than HIV; and behavior information, such as sexual identification, sexual practices (oral, anal and vaginal intercourse), and number of partners during the period of 1 year before the interview. Participants were asked to give some identification (nicknames, first name initial letter and so on) for each one of their casual and regular sexual contacts in the previous year. They were also asked to provide information on some demographic characteristics (e.g., age and sex), behavior information (e.g., sexual identification) and information on interaction with each partner (e.g., number of sex acts per week) for up to 10 partners (egocentric network data collection). Partner information was collected for the period that the participant maintained a relationship with each partner. In order to increase recall of sexual partners, we used supplementary techniques described by Brewer and Garrett [12] as name generators.

Laboratory

HIV testing was performed at the HESFA laboratory. The laboratory is a Ministry of Health certified unit for HIV testing and uses the official Brazilian guideline for diagnosing HIV (positive if two ELISA and one indirect immunofluorescence are positive) [13].

Measures

We defined sex as any kind of vaginal, anal or oral sex involving two or more people, regardless of the situation in which the sexual contact occurred, or the type of relationship the volunteer had with the other person. We defined regular partners as those with whom the volunteer had sex and described the relationship as an affair, frequent meetings, as boyfriend/girlfriend, as spouse or had any kind of stable relationship. Casual partners were those with whom the volunteer had sex without setting up other meetings or had no intention to sustain a relationship. Frequency of sex was defined as the number of sexual relationships per week, assuming once/twice in a lifetime as 0. The question on volunteers' risk perception to acquire the HIV for the year before the interview was valued from 0 (impossible) to 10 (I believe I have AIDS). The same values were used on partner's chance to acquire HIV (from 0/impossible to 10/I believe he or she has AIDS). Volunteers' perception of their level of accuracy in the responses regarding sex partners was measured from 0 (none) to 10 (100% sure).

Statistical analysis

We wanted to assess whether demographic markers and factors related to volunteers' sex partners were associated with the volunteers' HIV status. We created two models, the first using just characteristics of the volunteer (ego) and the second using volunteer–sex partner dyads to incorporate information on both volunteers and their sex partners. The dyadic data construction consist of one data record for each alter that includes volunteers characteristics and HIV status. For each model, we first screened for possible associations between potential risk factors and volunteers' HIV serostatus by using two sample, independent t-tests (for normally distributed variables) for continuous variables and chi-squared test (or Fisher's exact test, if 20% or higher of the table cells had an expected value of 5 or lower) in the case of categorical variables. All variables with a P value of less than 0.15 in the exploratory analysis, as well as any other biologically plausible variables were used in the multivariable modeling. We used logistic regression to model the association between volunteer characteristics and HIV positivity. For the dyadic analysis, we used a generalized linear model (generalized estimated equations, GEE) to adjust estimates for odds ratios (ORs) for the correlations in volunteer data. The ORs represent the relative odds of HIV positivity for the volunteer and sex partners' characteristics. We tested for plausible interactions in order to obtain final models.

For the two final, fitted models, we computed predictive event probabilities for each observation. A receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve, a plot of sensitivity vs. one-specificity for all values of the predictor variable, was generated for each model, and the area under the curve (c statistic) was calculated along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the c statistic [14]. The c statistic is an estimate of the probability that the value of the predictor variable, for a randomly selected case (HIV positive), will be higher than that for a randomly selected control (HIV negative) [15]. The discriminating ability of the model with characteristics of volunteers and the model with characteristics of volunteers and sex partners was then compared by plotting the two ROC curves together. We finished by fitting separated models by sex.

All data were entered by scanning using the Teleform software version 6.1 standard (Cardiff Software, Inc., San Marcos, California, USA). SAS (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA; 2002–2003) was used to analyze the data.

Human participants

Written informed consent was obtained from all volunteers prior to screening. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, USA, and by the Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Results

During the 13-month study period, 1290 volunteers were approached for inclusion. Forty of these individuals (3.1%) were not eligible for the study. Of the 1250 volunteers who were eligible, 19 (1.5%) were excluded, and the main reason was refusal to give blood later in the VCT (n = 13 of 19, 68%). General characteristics of the participating volunteers and their sex partners are shown in Table 1. Overall, the prevalence of HIV positivity was 7.6% (94/1231). Eight of the volunteer variables and four of the sex partners' characteristics met the screening criteria for inclusion in the multivariable modeling.

Table 1.

General characteristics of egos and alters' characteristics.

| Characteristics | Egos (n = 1231) |

Alters (n = 2668) |

|---|---|---|

| Timing of interview/n (%) | ||

| Before group counseling | 810 (65.8) | – |

| After group counseling | 421 (34.2) | |

| Sex/n (%) | ||

| Male | 799 (64.9) | 1233 (46.2) |

| Female | 432 (35.1) | 1435 (53.8) |

| Race/n (%) | ||

| White | 414 (33.6) | 1333 (50.1) |

| Black | 287 (23.3) | 404 (15.2) |

| Mulatto | 530 (43.1) | 926 (34.7) |

| Age in years old/n (%) | ||

| <30 | 627 (50.9) | 1516 (56.8) |

| 30–40 | 343 (27.9) | 629 (23.) |

| 40–50 | 185 (15.0) | 372 (13.9) |

| ≥50 | 76 (6.2) | 151 (5.7) |

| Marital status/n (%) | ||

| Single | 530 (43.1) | 1319 (49.4) |

| Married | 489 (39.7) | 830 (31.1) |

| Divorced | 193 (15.7) | 453 (17.0) |

| Widowed | 19 (1.5) | 34 (1.3) |

| Do not know | – | 32 (1.2) |

| Job/n (%) | ||

| Employed | 777 (63.1) | |

| Unemployed | 269 (21.9) | |

| Retired | 24 (1.9) | – |

| Student | 92 (7.5) | |

| Housewife | 40 (3.2) | |

| Other | 29 (2.4) | |

| Monthly family income (R$)/n (%) | ||

| ≤240.00 | 394 (32.0) | |

| 240.00–466.67 | 398 (32.3) | – |

| >466.67 | 439 (35.7) | |

| Sexual orientation/n (%) | ||

| Heterosexual | 1023 (83.1) | 2170 (81.4)a |

| MSM | 208 (16.9) | 497 (18.6) |

| Network size/n (%) | ||

| 1 | 639 (51.9) | |

| 2 | 277 (22.5) | – |

| 3 | 121 (9.8) | |

| ≥4 | 193 (15.8) | |

| Number of regular and casual partners, median (range) | 1.0 (1–33) | – |

| Sex in exchange for money or drug/n (%) | ||

| Yes | 37 (3.0) | |

| No | 1194 (97.0) | – |

| Use of any drug/n (%) | ||

| Yes | 216 (17.6) | |

| No | 1015 (82.4) | – |

| Risk perception for the prior year (average/SD) | 3.4/3.0b | – |

| Partner's chance to acquire HIV (average/SD) | – | 3.9/3.2c |

| Frequency of sex/week (average/SD) | – | 2.2/3.1a |

| Level of certainty about the answers (average/SD) | – | 8.1/2.0a |

| HIV serostatus (n = 2667)/n (%) | ||

| Positive | 94 (7.6) | 80 (3.0)d |

| Negative | 1137 (92.4) | 1413 (53.0) |

| Not known | – | 1174 (44.0) |

n = 2267.

n = 1227.

n = 2666.

Alters' HIV serostatus reported by egos.

The final, multivariable, logistic model using only characteristics of volunteers showed retired individuals, MSM and those who perceived themselves at higher risk for acquiring HIV in the previous year to have significantly increased odds of HIV infection (Table 2). Participants interviewed before the group counseling also more frequently had an HIV-positive test result. Volunteers reporting the highest monthly family income level were less likely to be HIV positive. Use of any drug in the prior year and volunteer's number of regular and casual partners were inversely related to the volunteer's chance of being HIV positive.

Table 2.

Final multivariable model of HIV accounting for egos' characteristics only.

| Characteristics | OR estimate | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Timing of interview | ||

| After group counseling (ref.) | 1.00 | – |

| Before group counseling | 1.93 | 1.15–3.24 |

| Job | ||

| Employed (ref.) | 1.00 | – |

| Unemployed | 0.98 | 0.56–1.71 |

| Retired | 4.58 | 1.45–14.42 |

| Other | 0.43 | 0.19–1.02 |

| Monthly family income (R$)a | ||

| ≤240.00 (ref.) | 1.00 | – |

| 240.00–466.67 | 0.82 | 0.47–1.42 |

| >466.67 | 0.51 | 0.28–0.93 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Heterosexual (ref.) | 1.00 | – |

| MSM | 7.00 | 4.24–11.56 |

| Number of regular and casual partners | 0.81 (1 higher) | 0.69–0.95 |

| Sex in exchange for money or drugs | ||

| No (reference) | 1.00 | – |

| Yes | 2.78 | 0.96–8.07 |

| Use of any drug | ||

| No (ref.) | 1.00 | – |

| Yes | 0.44 | 0.21–0.92 |

| Risk perception for the prior year | 1.12 (1 unit) | 1.04–1.21 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

R$ 466.67 ≈ US$ 220.

The final, multivariable, GEE model for men was based on the 1864 dyads with a male volunteer (Table 3). The risk patterns in the combined model for volunteer characteristics showed similar relationships as in the volunteer alone model, with the exception of number of sexual partners, which was replaced by a combined volunteer/sex partner variable. Additionally, presence of circumcision was associated with a lower chance of the volunteer being HIV positive. A number of sex partners' variables were also found to be predictive. Male sex for partner was associated with increased volunteer HIV positivity. Volunteers' perception of their accuracy in answers regarding sex partners was inversely associated with the chance of being HIV positive. Volunteers with high number of partners had a lower chance of being HIV positive, but those with only one partner at high risk had a higher risk of a positive HIV test.

Table 3.

Final multivariable dyadic model by sex of ego.

| Men (n = 1864) |

Women (n = 798) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | ORa | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Timing of interview | ||||

| After group counseling (ref.)b | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Before group counseling | 1.98 | 1.28–3.07 | 5.11 | 1.99–13.09 |

| Job | ||||

| Employed (ref.) | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Unemployed | 1.01 | 0.65–1.58 | 0.85 | 0.34–2.10 |

| Retired | 3.99 | 1.60–9.93 | 9.49 | 1.76–51.17 |

| Other | 0.37 | 0.16–0.85 | 0.75 | 0.27–2.10 |

| Monthly family income (Rs.) | ||||

| ≤240.00 (ref.) | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| 240.00–466.67 | 0.86 | 0.49–1.49 | ||

| >466.67 | 0.52 | 0.31–0.88 | ||

| Circumcisedc | ||||

| No (ref.) | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Yes | 0.33 | 0.16–0.69 | ||

| Sexual orientationd | ||||

| Heterosexual (ref.) | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| MSM | 5.75 | 3.04–10.89 | ||

| Sex in exchange for money or drug | ||||

| No (ref.) | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Yes | 6.14 | 3.30–11.44 | ||

| Use of any drug | ||||

| No (ref.) | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Yes | 0.32 | 0.17–0.61 | ||

| No. of regular and casual partners | – | – | 0.85 | 0.76–0.94 |

| Risk perception for the prior year | – | – | 1.23 | 1.10–1.37 |

| Alters' sexd | ||||

| Female (ref.) | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Male | 2.33 | 1.28–4.25 | ||

| Level of certainty about answers | 0.82 | 0.74–0.91 | – | – |

| Partner's chance to acquire HIV | – | – | 1.15 | 1.04–1.27 |

| Number of regular and casual partners and partner's chance to acquire HIVe | ||||

| Low number of regular and casual partners and low partner's chance to acquire HIV (ref.) | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Low number of regular and casual partners and high partner's chance to acquire HIV | 2.11 | 1.37–3.26 | ||

| High number of regular and casual partners and low partner's chance to acquire HIV | 0.21 | 0.10–0.41 | ||

| High number of regular and casual partners and high partner's chance to acquire HIV | 0.08 | 0.03–0.20 | ||

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Generalized estimated equations.

Ref., category of reference.

Defined only for men.

Women who have sex with women were not included in our study.

Number of regular and casual partners: high, 8; low, 1; partner's chance to acquire HIV: high, 8; low, 3.

For the GEE model based on the 798 dyads with a female volunteer (Table 3), retired volunteers, those interviewed before counseling and those who perceived themselves at higher risk were at increased risk, as was found in the general GEE model. Higher family income, sexual orientation, drug use and sex in exchange for money or drugs were not found to be significantly associated with HIV status for female volunteers. Number of partners and partner's chance to acquire HIV were included separately rather than as a combined variable, with an inverse relationship between number of partners and risk (as was found in the volunteer alone model) and an increased risk for female volunteer's who felt that their sex partners had a higher chance of being HIV positive.

The final, multivariable, GEE model was a better fit to the data than the model with volunteer characteristics alone for men but not for women (Figs 1 and 2). The c statistic for men volunteers was 0.82 (95% CI 0.77–0.87) for the volunteer alone model and 0.88 (95% CI 0.86–0.91) for the combined model (P=0.03). The values for women were 0.75 (95% CI 0.65–0.86) and 0.78 (95% CI 0.71–0.85), respectively (P= 0.71).

Fig. 1. Receiver operator characteristic curves for the final multivariable models with and without alters' characteristics for men.

CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 2. Receiver operator characteristic curves for the final multivariable models with and without alters' characteristics for women.

CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first network-based research of STI performed in Brazil. Our study showed that variables related to both volunteer and sex partners were associated with HIV serostatus.

Although small sample size, male and female retired individuals had a higher chance to be HIV positive compared with employed individuals. Approximately 70% of retired volunteers in our sample were 50 years or older. It is an important finding because it confirms a national trend and identifies a new area of possible research [2]. Aging individuals have their own epidemiological risk factors for HIV infection, do not perceive themselves as at risk for acquiring HIV, find it harder to adopt preventive measures and do not have HIV/STI programs with preventive measures directed to them [16-19]. Volunteers with higher socioeconomic status were less likely to be HIV positive. This was true for men, but not for women, and confirms data indicating a shift of the epidemic to the poorer segment of the Brazilian population [19,20]. Our data indicate that MSM are still a core risk group for HIV. We were also able to show that the only factor associated with unsafe sex (e.g., sex at first date, use of condom, forced to have sex and so on) between HIV-positive men and their female partners was exchanging sex for money or drugs, a result similar to the study by Aidala et al. [21]. Finally, our data indicating male circumcision associated with a lower chance of volunteer being HIV positive [22] is in line with the recent data from Africa [23].

We have described a sample from a highly prevalent HIV population, both for men (8.9%; 71/799) and women (5.3%; 23/432). Therefore, the low level of risky behavior that we found for volunteers is somewhat surprising. In fact, some known risk factors, such as use of drugs for men and high numbers of partners for both sexes, are inversely related to HIV serostatus. In an attempt to explain our results, we turn our attention to the variable that showed volunteers interviewed before group counseling were more likely to be HIV positive compared with individuals interviewed after group counseling. We can speculate that some level of selection bias affected our final results. Those individuals, who perhaps perceived themselves at a higher risk to acquire HIV for some reason, arrived early in the VCTand waited longer before being tested. Therefore, they were more likely to be interviewed. Most of them may have actually known that they were infected but would not disclose it because they would be prevented from both re-testing for HIV at the VCT and participating in our study. Those already HIV infected may have reduced their risk behavior profile (e.g., reduced the number of partners) and moved to a network of people with greater chance of being HIV infected because of the infection. There are several data from other studies [24-27] showing that both MSM and heterosexuals tend to reduce risk after becoming HIV infected. A recent meta-analysis in the United States of high-risk behavior in persons aware and unaware of HIV infection showed that the prevalence of high-risk behavior is indeed reduced after people become aware they are HIV positive [28]. The serosorting, HIV-positive patient preferentially selects other HIV-positive patient, has been described among MSM as a safer sex practice to avoid HIV transmission [29,30]. We anticipated the risk reduction in HIV-positive patients in our design and tried to exclude individuals with AIDS, by using the Caracas criteria, and HIV-positive volunteers, by only allowing those never tested positive before (self-disclosure). The associations, among women, between timing of interview, number of regular and casual partners and risk perception of HIV seropositive status for volunteer and sex partners, with chance of volunteer being HIV positive, indicate that the selection bias was not related to the sex of the volunteer.

Partner-specific variables were also associated with HIV serostatus. Having had a male sex partner increased the chance of the volunteer being HIV positive for MSM (variable not defined for women as we did not include women who have sex with women). Men HIV-positive volunteers reported a level of certainty in their answers regarding partners that was slightly lower than for HIV-negative individuals. This fact may reflect either less trustful relationships among MSM [31] or more casual partners among them. Women volunteers not only perceive their risk to acquire HIV as high but also believe that their partners have a higher chance to acquire HIV. These results and the absence of other risk factors demonstrated that the biggest risk factor for women is having a male partner [32,33]. Finally, the interaction term shows that the risk of a positive HIV test for men is highest for volunteers, with only one partner who is believed to be at risk for HIV. The inverse relationship between number of regular and casual partners and volunteers' HIV serostatus may be explained by the possible biased selection of HIV-positive patients in our sample with lower number of partners.

The comparison between the two ROC curves demonstrates that partner-specific variables were important in increasing the predictability of the final multivariable model for men but not for women. A model for men with characteristics of both volunteer and sex partners performed better in discriminating between HIV positive and HIV-negative volunteers. Whittington et al. [34] have shown that indeed partner-level data are useful in refining volunteers' risk assessment.

Apart from the bias cited above, our study has other potential limitations. There are some indications from network studies that HIV-infected individuals tend to decrease their network size, to be marginalized within the social structure and to move to subgroups with more HIV-positive patients [35,36]. By using the cross-sectional design, we have no way to confirm whether our volunteers presented a higher chance of being HIV positive because they were engaging in sex practices with positive partners or whether they had moved to a network with positive partners because they became HIV positive. Low recall of sex partners is one of the major problems in network research that could bias final conclusions [37]. Although recall may have been responsible for some missing links between volunteers and sex partners, we do not believe this problem had a great impact in our analysis because our sample is mostly composed of volunteers reporting a low number of sex partners in the previous year, and other data have shown that these groups of individuals are usually less likely to forget past partners [38]. We were not able to go after sex partners to get information about their demographic and sexual behavior from them directly. Therefore, all information about partners was collected from volunteers. Several studies [9,39,40] have shown different levels of reliability in different populations for specific variables. Stoner et al. [41] showed that the agreement between ego and partners was higher for fixed personal characteristics, such as age and race, and for partnership duration, and was lower for partners' numbers of other sex partners and for measures of communication within partnerships such as condom use within partnership. In spite of that inconsistency, some authors argue that reliability of egos' information about alters' risk factors is not of fundamental importance, as perception of neighborhood risk is a reliable surrogate [42].

Our study has several strengths in its design, apart from the large sample size that we were able to enroll. We have anticipated potential biases, such as selection of less risky volunteers, interviewer bias and bias due to low recall of past partners, and proposed solutions for some of them and made sure that we would be able to account for some in the final analysis. By using these measures, we were able to identify possible selection bias that would pass without notice otherwise. Also, we used and adapted a supplementary technique in order to increase recall of past sex partners and reduce the bias in our network design resulting from missing links [43].

Conclusion

Although our results may not be generalizable to other population settings, we were able to show that some partner-specific characteristics are important to explain individual's chance of being HIV positive, mainly for men. If anything, our limitations resulted in an under-estimation of the real effect of sex partners' characteristics on our volunteers. We believe that if we are able to characterize the effect of the entire neighborhood (all sex contacts in direct contact with a person) on ego, we will improve our ability to identify individuals at higher risk to acquire HIV. Our methods and results are important for researchers conducting HIV studies such as vaccine trials by identifying and characterizing more effectively people at higher risk for HIV infection through the introduction in their design of egocentric information in addition to the traditional individual risk profile identification from regular surveys.

Acknowledgements

All authors were involved in the conception and design of the study. A.R.S.P, M.B., M.C. and W.B. submitted the grant proposal for the PhD funding. A.R.S.P. conducted the statistical analysis, interpreted the data and wrote the first draft of the article. P.L. and M.B. assisted and guided the statistical analysis, and were involved in the data interpretation. All authors contributed to the final draft. They all read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors wish to thank the Fogarty International Center for financial support to one of the authors (A.R.S.P.) through a Doctorate training scholarship (AIDS International Training and Research Program/AITRP, National Institute of Health Research grant #D43-TW001041). Funding for this study was totally provided by the Fogarty International Center (Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health) Small Research Grant number 1 R03 TW006876-01A1 (Revised).

Footnotes

The authors do not have any commercial or other association that might pose a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic 2008: executive summary. UNAIDS: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epidemiological Bulletin - Year V, n.1. Secretariat of Health Surveillance, National Program for STD and AIDS, Ministry of Health; Brazil: 2008. AIDS and STDs. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epidemiological Bulletin: AIDS, Tuberculosis and Leprosy. Coordination of Communicable Diseases, Municipal Health; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: 2008. The epidemic of HIV and AIDS in Rio de Janeiro. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jolly AM, Muth SQ, Wylie JL, Potterat JJ. Sexual networks and sexually transmitted infections: a tale of two cities. J Urban Health. 2001;78:433–445. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott J. Social Network Analysis: a handbook. SAGE Publications; London: 2000. Points, lines and density; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellen JM, Gaydos C, Chung SE, Willard N, Lloyd LV, Rietmeijer CA. Sex partner selection, social networks, and repeat sexually transmitted infections in young men: a preliminary report. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:18–21. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000187213.07551.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghani AC, Swinton J, Garnett GP. The role of sexual partnership networks in the epidemiology of gonorrhea. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:45–56. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199701000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson KM, Alarcon J, Watts DM, Rodriguez C, Velasquez C, Sanchez J, et al. Sexual networks of pregnant women with and without HIV infection. AIDS. 2003;17:605–612. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303070-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neaigus A, Friedman SR, Goldstein M, Ildefonso G, Curtis R, Jose B. Using dyadic data for a network analysis of HIV infection and risk behaviors among injecting drug users. NIDA Res Monogr. 1995;151:20–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youm Y, Laumann EO. Social network effects on the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:689–697. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200211000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weniger BG, Quinhoes EP, Sereno AB, de Perez MA, Krebs JW, Ismael C, et al. A simplified surveillance case definition of AIDS derived from empirical clinical data. The Clinical AIDS Study Group, and the Working Group on AIDS case definition. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:1212–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brewer DD, Garrett SB. Evaluation of interviewing techniques to enhance recall of sexual and drug injection partners. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:666–677. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ordinance n.59, January 28th, 2003. Ministry of Health, Office of the Minister; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agate LL, Mullins JM, Prudent ES, Liberti TM. Strategies for reaching retirement communities and aging social networks: HIV/AIDS prevention activities among seniors in South Florida. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(Suppl 2):S238–S242. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drumright LN, Little SJ, Strathdee SA, Slymen DJ, Araneta MR, Malcarne VL, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse and substance use among men who have sex with men with recent HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:344–350. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000230530.02212.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karlovsky M, Lebed B, Mydlo JH. Increasing incidence and importance of HIV/AIDS and gonorrhea among men aged >/= 50 years in the US in the era of erectile dysfunction therapy. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2004;38:247–252. doi: 10.1080/00365590410025488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon M. We must understand that all of us who are sexually active can contract the virus. Radis: Health Communication. 2007;53:26–27. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reiche EM, Bonametti AM, Watanabe MA, Morimoto HK, Morimoto AA, Wiechmann SL, et al. Socio-demographic and epidemiological characteristics associated with human immunodeficiency virus type I (HIV-1) infection in HIV-1-exposed but uninfected individuals, and in HIV-1-infected patients from a southern Brazilian population. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2005;47:239–246. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652005000500001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aidala AA, Lee G, Howard JM, Caban M, Abramson D, Messeri P. HIV-positive men sexually active with women: sexual behaviors and sexual risks. J Urban Health. 2006;83:637–655. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9074-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perisse AR, Schechter M, Blattner W. Association between male circumcision and prevalent HIV infections in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:435–437. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181958591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I, Krieger JN, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:643–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrill AC, Ickovics JR, Golubchikov VV, Beren SE, Rodin J. Safer sex: social and psychological predictors of behavioral maintenance and change among heterosexual women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:819–828. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otten MW, Jr, Zaidi AA, Wroten JE, Witte JJ, Peterman TA. Changes in sexually transmitted disease rates after HIV testing and posttest counseling, Miami, 1988 to 1989. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:529–533. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.4.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsons JT, Halkitis PN, Wolitski RJ, Gomez CA. Correlates of sexual risk behaviors among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15:383–400. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.6.383.24043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, Bickham NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1397–1405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsons JT, Schrimshaw EW, Wolitski RJ, Halkitis PN, Purcell DW, Hoff CC, Gomez CA. Sexual harm reduction practices of HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men: serosorting, strategic positioning, and withdrawal before ejaculation. AIDS. 2005;19(Suppl 1):S13–S25. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000167348.15750.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia Q, Molitor F, Osmond DH, Tholandi M, Pollack LM, Ruiz JD, Catania JA. Knowledge of sexual partner's HIV serostatus and serosorting practices in a California population-based sample of men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2006;20:2081–2089. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247566.57762.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Périssé A, Amorim C, Silva J, Schechter M, Blattner W. AIDS 2006: XVI International AIDS Conference. Toronto, Canada: Aug, 2006. Relationship of egocentric network characteristics and HIV transmission among MSM in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quinn TC, Overbaugh J. HIV/AIDS in women: an expanding epidemic. Science. 2005;308:1582–1583. doi: 10.1126/science.1112489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turmen T. Gender and HIV/AIDS. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82:411–418. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(03)00202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whittington WL, Morris M, Buchbinder SP, McKirnan DJ, Mayer KH, Para MF, et al. Partner-specific sexual behavioral differences between phase 3 HIV vaccine efficacy trial participants and controls: Project VISION. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:234–238. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000230296.06829.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shelley GA, Bernard HR, Killworth P, Johnsen E, McCarty C. Who knows your HIV status: what HIV plus patients and their network members know about each other. Soc Net. 1995;17:189–217. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woodhouse DE, Rothenberg RB, Potterat JJ, Darrow WW, Muth SQ, Klovdahl AS, et al. Mapping a social network of heterosexuals at high risk for HIV infection. AIDS. 1994;8:1331–1336. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199409000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghani AC, Donnelly CA, Garnett GP. Sampling biases and missing data in explorations of sexual partner networks for the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. Stat Med. 1998;17:2079–2097. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980930)17:18<2079::aid-sim902>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brewer DD, Potterat JJ, Muth SQ, Malone PZ, Montoya P, Green DL, et al. Randomized trial of supplementary interviewing techniques to enhance recall of sexual partners in contact interviews. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:189–193. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000154492.98350.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldstein MF, Friedman SR, Neaigus A, Jose B, Ildefonso G, Curtis R. Self-reports of HIV risk behavior by injecting drug users: are they reliable? Addiction. 1995;90:1097–1104. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90810978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Padian NS, Aral S, Vranizan K, Bolan G. Reliability of sexual histories in heterosexual couples. Sex Transm Dis. 1995;22:169–172. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199505000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoner BP, Whittington WL, Aral SO, Hughes JP, Handsfield HH, Holmes KK. Avoiding risky sex partners: perception of partners' risks v partners' self reported risks. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:197–201. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.3.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valente TW, Watkins SC, Jato MN, van der Straten A, Tsitsol LP. Social network associations with contraceptive use among Cameroonian women in voluntary associations. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:677–687. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00385-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perisse AR, Langenberg P, Hungerford L, Boulay M, Charurat M, Schechter M, Blattner W. The use of supplementary techniques to increase recall of sex partners in a network-based research study in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:674–678. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31816b323d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]