Abstract

Recurrent microdeletions and microduplications of a 600 kb genomic region of chromosome 16p11.2 have been implicated in childhood-onset developmental disorders1-3. Here we report the strong association of 16p11.2 microduplications with schizophrenia in two large cohorts. In the primary sample, the microduplication was detected in 12/1906 (0.63%) cases and 1/3971 (0.03%) controls (P=1.2×10-5, OR=25.8). In the replication sample, the microduplication was detected in 9/2645 (0.34%) cases and 1/2420 (0.04%) controls (P=0.022, OR=8.3). For the series combined, microduplication of 16p11.2 was associated with 14.5-fold increased risk of schizophrenia (95% C.I. [3.3, 62]). A meta-analysis of multiple psychiatric disorders showed a significant association of the microduplication with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and autism. The reciprocal microdeletion was associated only with autism and developmental disorders. Analysis of patient clinical data showed that head circumference was significantly larger in patients with the microdeletion compared with patients with the microduplication (P = 0.0007). Our results suggest that the microduplication of 16p11.2 confers substantial risk for schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders, whereas the reciprocal microdeletion is associated with contrasting clinical features.

Rare structural mutations play an important role in schizophrenia. Recent studies have shown that the genome-wide burden of rare copy number variants (CNVs) is significantly greater in patients than in healthy controls 4-6. In addition, multiple structural variants have been implicated in schizophrenia. Seminal examples include the recurrent microdeletion of 22q11.2 7, and a balanced translocation disrupting the gene DISC1 8. More recently, recurrent microdeletions at 1q21.1, 15q13.3, 5,9 and 15q11.2 6,9 and copy number mutations at other genomic loci10-12 have been associated with schizophrenia in large cohorts.

We previously reported two cases of childhood-onset schizophrenia (COS) with a 600 kb microduplication of 16p11.2 4. This region is a well documented hot spot for recurrent rearrangements in association with autism spectrum disorders and mental retardation 1-3, 13, 14. Genomic hotspots such as this are important candidate loci in genetic studies of schizophrenia.

We tested the hypothesis that microduplications of 16p11.2 are associated with schizophrenia by analysis of microarray intensity data in a sample of 1906 cases and 3971 controls. Patients and controls were drawn from several different sources, as described in the supplemental note and supplementary table 1. Samples were analyzed with one of four microarray platforms (NimbleGen HD2, Affymetrix 6.0, Affymetrix 500K and ROMA 85K). Only the 16p11.2 region was examined. Thirteen microduplications and four microdeletions were detected in our primary sample using standard segmentation algorithms (Figure 1A, Supplementary Figure 1A). Microduplications were detected in 12/1906 cases (0.63%) and 1/3971 controls (0.03%), a statistically significant association (Table1, P = 1.2×10-5, OR = 25.8 [3.3, 199]).

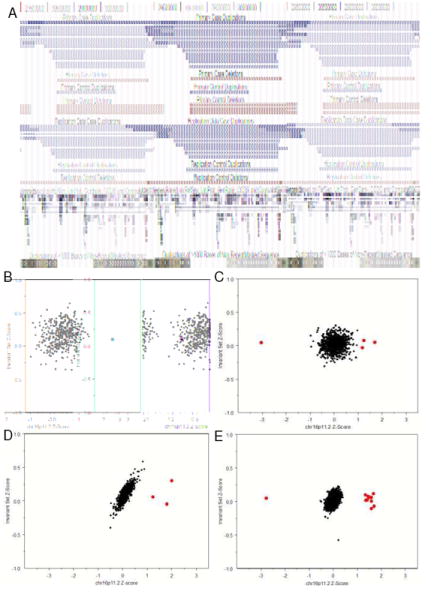

Figure 1. Microduplications and microdeletions at 16p11.2 in persons with schizophrenia and controls.

(A) 16p11.2 rearrangements were detected in a primary sample of 1906 cases and 3971 controls (Panels A, B, C, D) and a replication sample of 2645 cases and 2420 controls (Panel A, E). The single microduplication and three microdeletions detected in the primary control set are presented based on the Affymetrix 500K coordinates (hg18). All other CNVs were validated in the NimbleGen HD2 platform and are illustrated based on the validation coordinates (Panels B, C, D, E) The median z-score for the 535kb 16p11.2 target region is plotted on the X-axis and the median z-score of flanking invariant probes is plotted on the Y-axis. Data are presented separately for the ROMA (B), Affymetrix500K (C), NimbleGen HD2 (D), and (Affymetrix 6.0 (E) platforms. CNVs were called using thresholds of >2 SD for ROMA and >1 SD for all other platforms ( ). MeZOD and the HMM algorithms detected the same deletions and duplications at 16p11.2.

). MeZOD and the HMM algorithms detected the same deletions and duplications at 16p11.2.

Table 1.

Duplications and deletions at 16p11.2 among persons with schizophrenia and controls

| Series |

Diagnosis |

Subjects |

Deletions |

Duplications |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N |

N |

% |

N |

% |

OR[95% C.I.] |

P-Value |

||

| Primary | ||||||||

| Schizophrenia | 1906 | 1 | 0.05 | 12 | 0.63 | 25.8 [3.3,199] | 1.2×10-5 | |

| Controls | 3971 | 3 | 0.08 | 1 | 0.03 | |||

| Replication | ||||||||

| Schizophrenia | 2645 | 0 | 0.00 | 9 | 0.34 | 8.3 [1.3, 50.5] | 0.022 | |

| Controls | 2420 | 1 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.04 | |||

| Combined | ||||||||

| Schizophrenia | 5877 | 1 | 0.02 | 21 | 0.36 | 14.5 [3.3, 62.0] | 4.3×10-5 | |

| Controls | 6391 | 4 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.03 | |||

In the primary sample, which consisted of patients and controls genotyped using one of 3 microarray platforms, association was calculated using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel exact test using array type as a stratifying variable. Combined odds ratio estimates and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using a logistic regression with disease group and array-type as factors. In the replication sample, which consisted of patients and controls assessed on a single microarray platform, association was calculated using a Fisher’s exact test. Deletions did not show a significant association with schizophrenia or in controls.

In a subset of individuals evaluated at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, consisting of 1352 cases and 1179 controls, CNV calls were verified by MeZOD, an independent CNV genotyping algorithm that identifies outliers in the sample based on the median probe Z-score of the target region. These results are illustrated in Figure 1 as cluster plots. All microduplications and microdeletions detected in the combined sample were experimentally validated using an independent microarray platform (Supplementary Table 2).

In order to replicate this association, we evaluated the 16p11.2 region using microarray data (Affymetrix 6.0 platform) from an independent sample of 2645 schizophrenia cases and 2420 controls. These data were collected as part of a case-control study of schizophrenia supported by the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN, phs000021.v2.p1). We detected ten duplications and one deletion using standard HMM calling algorithms (Figure 1A). The same events were also detected using MeZOD (Figure 1E). All 16p11.2 rearrangements were validated by an independent microarray platform (Supplementary Table 2). The microduplication was detected in 9/2645 cases and 1/2420 controls, a significant association (P = 0.022, OR=8.3 [1.3, 50.5]).

The odds ratios in our primary and replication datasets were not significantly different (Breslow-Day-Tarone test P = 0.46). Thus, our initial result was replicated in an independent sample. For the combined sample, the association of schizophrenia with microduplication at 16p11.2 was highly significant (P=4.3×10-7, OR=14.5 [3.3,62]). Sex of the subject did not have a significant effect on the association (Supplementary Note)

Our present findings, and those from previous studies1-3, 13, 14, suggest that mutations at 16p11.2 confer high risk for schizophrenia and for other neuropsychiatric disorders. Clinical variability associated with the 16p11.2 microduplication is evident from the heterogeneity of psychiatric diagnoses among microduplication carriers in five families in our series (Supplementary Figure 2). In these families, ten relatives carried the microduplication found in the proband. The diagnoses of these relatives were: schizophrenia (N=3), bipolar disorder (N=1), depression (N=2), psychosis signs not otherwise specified (N=1), and no mental illness (N=3). We were able to determine the parent of origin in four families, and in all cases the microduplications were inherited from a non-schizophrenic parent. The observations in these few families suggest that penetrance of the duplication is incomplete, though substantial (perhaps 30-50%), and that expression is highly variable.

In order to more precisely define the spectrum of psychiatric phenotypes associated with rearrangements of 16p11.2, we performed a meta-analysis of data on schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and childhood developmental disorders (combining autism and global developmental delays). We integrated data from this study with four publicly available datasets 1,3,5, 15 to generate a combined sample of 8590 individuals with schizophrenia, 2172 with developmental delay or autism, 4822 with bipolar disorder, and 30,492 controls (Supplementary Note, Supplementary Table 3). In this combined sample, the microduplication of 16p11.2 was strongly associated with schizophrenia (Table 2, OR = 8.4 [2.8, 25.4], P = 4.8×10-7) and autism (OR = 20.7 [6.9, 61.7], P = 1.9×10-7). The association with bipolar disorder was also significant (OR = 4.3 [1.3; 14.5], P = 0.017). The reciprocal microdeletion of 16p11.2 was strongly associated with developmental delay or autism (OR = 38.7 [13.4, 111.8], P = 2.3×10-13), as reported previously1-3. However, the deletion was not associated with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (Supplementary Note). These results suggest that the microduplication is associated with multiple psychiatric phenotypes, whereas the reciprocal microdeletion is more specifically associated with developmental delay and autism.

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of 16p11.2 rearrangements in schizophrenia, autism and developmental delay, and bipolar disorder

| Diagnosis |

Subjects |

Deletions |

Duplications |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N |

N |

% |

OR[95% C.I.] |

P-Value |

N |

% |

OR[95% C.I.] |

P-Value |

|

| Schizophrenia | 8590 | 3 | 0.03 | NC* | 26 | 0.30 | 8.4 [2.8, 25.4] | 4.8×10-7 | |

| Controls | 28406 | 9 | 0.03 | 8 | 0.03 | ||||

| Autism or Developmental Delay | 2172 | 17 | 0.78 | 38.7 [13.4,111.8] | 2.3×10-13 | 10 | 0.46 | 20.7 [6.9,61.7] | 1.9×10-7 |

| Controls | 24891 | 5 | 0.02 | 6 | 0.02 | ||||

| Bipolar Disorder | 4822 | 4 | 0.08 | NC* | 6 | 0.12 | 4.3 [1.3; 14.5] | 0.017 | |

| Controls | 25225 | 6 | 0.02 | 7 | 0.03 | ||||

Not calculated (NC) because significant heterogeneity among studies was detected by the Breslow-Day Tarone test. The partial odds ratios [95%CI] for the deletion in schizophrenia were 0.69 [0.1, 4.9], 0.3 [0.05, 2.2], 14.6 [1.9, 111.2], and 0.3 [0.03, 3.7] and partial odds ratios for the deletion in bipolar disorder were 0.3[0.03,3.3], 0.55[0.05,6.7], 25[5.4,117] in this study, the GAIN study and the Weiss et al. studies, respectively.

Data from four studies reporting microduplications and microdeletions of 16p11.2 in schizophrenia, autism and/or bipolar disorder were combined with data from the Primary Sample to assess the relative strength of the association of each variant with each disorder. Associations were calculated using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel exact test, using source as a stratifying variable. Combined odds ratio estimates and confidence intervals were calculated from logistic regression with disease group and source (study) as factors.

We explored the association of 16p11.2 microduplications and microdeletions with two clinical measures, head circumference and height. Available data were compiled from 32 patients with 16p11.2 mutations who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder or developmental delay (Supplementary Note, Supplementary Tables 4 and references 13, 16). Z-scores for head circumference and height were calculated using standard growth charts from the Centers for Disease Control. Head circumference was greater among 23 patients with microdeletions relative to 9 patients with microduplications (Supplementary Table 5). The mean orbital frontal circumference (OFC) values of patients with microdeletions and microduplications were 1.25 and -0.28, respectively (two-tailed Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test P = 0.0007). In addition, mean head circumference of the microdeletion group was significantly greater than the population mean (P = 0.0001), whereas the mean head circumference of the microduplication group was not statistically significant (P = 0.29). The association between the 16p11.2 microdeletion and larger head circumference was observed in multiple diagnostic categories and was not specifically attributable to patients with autism (Supplemental Table 5). The microduplication and microdeletion groups did not differ significantly in height.

Microduplication of 16p11.2 is associated with increased risk of schizophrenia between 8 and 24-fold. This region joins a growing list of genomic hotspots that confer high risk for the disorder. The odds ratios in our series for the 16p11.2 microduplication and schizophrenia are comparable to odds ratios for deletions at other schizophrenia-associated genes and regions. Deletions of 1q21.1, 15q13.3, and NRXN1 have reported odds ratios ranging from 7 to 18 5,9,10.

Previous genome-wide studies of copy number variation did not find a significant association with the microduplication of 16p11.2 and schizophrenia. This event is rare, and its appearance in a cohort may be influenced by several factors, including resolution of the detection platform, methods of analysis, and chance. In the International Schizophrenia Consortium (ISC) study 5, microduplications spanning >50% of the 16p11.2 region were detected in 5/3391 cases and 1/3181 controls. These results are consistent with our findings, but the association did not meet the criteria for genome-wide significance in that study. In the SGENE consortium study of schizophrenia 9, the 16p11.2 microduplication was not selected as a candidate because the event was not observed in the initial phase of that study as a de novo mutation, which was the key criterion for inclusion in the association analyses.

Microduplication at 16p11.2 is associated with multiple neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Phenotypic heterogeneity has been observed for virtually all structural variants associated with schizophrenia. For example, in a large Scottish pedigree harboring a translocation disrupting DISC1, translocation carriers had diagnoses of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or no mental illness 8. Similarly, microdeletions of 1q21.117,18, 15q13.319, 22q11.2 20, and neurexin-1 21,22 10,12 are associated with adult psychiatric disorders and with autism and other pediatric neurodevelopmental disorders.

The association between the 16p11.2 microdeletion and increased head circumference is interesting given that the microdeletion appears specific to autism and developmental delay. Several studies have found increased head circumference in patients with autism 23-30, leading to the suggestion that early brain overgrowth may be a key neurobiological mechanism in the disorder 31. A recent study has shown that microdeletions and microduplications of 1q21.1 are associated with microcephaly and macrocephaly respectively18. Taken together, these studies suggest that some mutations underlying neurodevelopmental disorders may also lead to changes in brain volume.

The 16p11.2 microduplication spans a region of approximately 600kb containing 28 genes (Supplementary Figure 1B), including multiple genes with potential roles in neurodevelopment. At least 17 of the 28 genes are expressed in the mammalian brain (Supplementary Table 6). Behavioral features have been reported in mouse knockout models of Mapk3 -/- Doc2a-/-and Sez6/2-/- 32-34. Further studies are needed in order to identify the specific gene or genes in this region for which dosage effects contribute to increased risk for psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Our findings further strengthen the evidence demonstrating a role for rare mutations in schizophrenia 4-6,9. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that schizophrenia is characterized by marked genetic heterogeneity. The 16p11.2 locus by itself accounts for only a small fraction of the illness. At the same time, duplication of this region confers substantial risk to the individuals who carry it. The fact that a single mutation is rare does not negate its potential relevance to the broader patient population. The collective effect of rare mutations at many different loci may account for a substantial proportion of affected individuals 4,5. Furthermore, the microduplication of 16p11.2 and rare mutations at other loci will likely impact overlapping neurobiological pathways. Characterizing these critical brain processes will contribute substantially to our understanding of the origins of schizophrenia and provide important targets for treatment development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by grants from Ted and Vada Stanley, the Simons Foundation, grants from NARSAD to FJM, TGS, DLL, MCK and TW, and grants from the Essel Foundation and the Sidney R. Baer, Jr. Foundation to DLL and from the Margaret Price Investigatorship to JBP and VLW. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program, National Institutes of Health, including NIMH grant MH076431 to JS, which reflects co-funding from Autism Speaks, and the Southwestern Autism Research and Resource Center, as well as NIH grants to JS (HF004222), MCK, TW, and JMC (MH083989), DLL and NRM (MH071523; MH31340), JMC (RR000037), PFS (MH074027 and MH077139), JSS (MH061009), LED (MH44245), THS (GM081519) and CKD (MH081810; DE016442; HD04147). Funding for GK, NC, MJO and MCO was provided by the Medical Research Council, UK, and the Wellcome Trust. The CATIE project was funded by NIMH contract N01 MH90001. Genotyping of the Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia study (PI Pablo Gejman) was funded by the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN) of the Foundation for the US National Institutes of Health. Genotype data were obtained from dbGaP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/dbgap, accession number phs000021.v2.p1). This study makes use of data generated by the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium (full list of contributors is presented in the supplementary online material). Funding for that project was provided by the Wellcome Trust under award 076113. Microarray data and clinical information were provided by the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN). Thanks to the New York Cancer Project, Peter Gregersen and Annette Lee for providing population control samples. Also, we wish to thank Drs. Pablo Gejman and Douglas Levinson for helpful discussions. Special thanks to Dr. James Watson for helpful discussions and support.

Footnotes

Authors Contributions J.S. organized and designed the study. S.M.C., J.S., S.Y., N.R.M., M-C.K., G.K., D.G. and A.A. contributed to the analysis of genetic data. S.M.C., J.S., C.K.D. and D.L.L. contributed to the analysis of clinical data. S.M.C. and J.S prepared the manuscript. All authors contributed their critical reviews of the manuscript in its preparation. The following persons contributed to the collection of samples and data: (Schizophrenia) G.K., D.G., N.Craddock, M.J.O., M.C.D., WTCCC, A.A., J.R., D.P., J.L., S.S., P.F.S., J.M.C., D.E.D., T.W., M-C.K., E.S., O.K., V.K., D.L.L., T.J.C., and L.E.D.; (Bipolar Disorder) J.P., M.G., V.L.W., P.DeR., S.G., J.S., L.K., J.W., N.C., F.J.M., A.K.M., J.B.P., T.G.S., M.M.N., S.C., M.R., E.L., G.K., D.G., N.Craddock, M.J.O., M.C.D., and WTCCC; (Autism) V.K., C.M.L., E.H.Z., P.K., J.G., I.D.K., N.B.S., C.H-E., T.H.S., M.G., L.G., T.L., K.P., R.A.K., S.L.C., J.S.S., and D.S.. Array-CGH data collection, processing and management at CSHL were carried out by: S.M.C., D.M., V.M., S.Y., M.K., P.R., A.B., K.P., B.L., A.L., J.K., Y-H.L., L.I., V.V. and J.S.

References

- 1.Weiss LA, et al. Association between microdeletion and microduplication at 16p11.2 and autism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:667–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa075974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar RA, et al. Recurrent 16p11.2 microdeletions in autism. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:628–38. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall CR, et al. Structural Variation of Chromosomes in Autism Spectrum Disorder. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2008;82:477–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh T, et al. Rare Structural Variants Disrupt Multiple Genes in Neurodevelopmental Pathways in Schizophrenia. Science. 2008;320:539–543. doi: 10.1126/science.1155174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone JL, et al. Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications increase risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2008;455:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature07239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirov G, et al. Support for the involvement of large cnvs in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;14:796–803. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karayiorgou M, et al. Schizophrenia susceptibility associated with interstitial deletions of chromosome 22q11. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7612–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Millar JK, et al. Disruption of two novel genes by a translocation co-segregating with schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1415–23. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.9.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stefansson H, et al. Large recurrent microdeletions associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nature07229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rujescu D, et al. Disruption of the neurexin 1 gene is associated with schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman JI, et al. CNTNAP2 gene dosage variation is associated with schizophrenia and epilepsy. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:261–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirov G, et al. Comparative genome hybridization suggests a role for NRXN1 and APBA2 in schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:458–65. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghebranious N, Giampietro PF, Wesbrook FP, Rezkalla SH. A novel microdeletion at 16p11.2 harbors candidate genes for aortic valve development, seizure disorder, and mild mental retardation. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143:1462–71. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sebat J, et al. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with autism. Science. 2007;316:445–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1138659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manolio TA, et al. New models of collaboration in genome-wide association studies: the Genetic Association Information Network. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1045–51. doi: 10.1038/ng2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bijlsma EK, et al. Extending the phenotype of recurrent rearrangements of 16p11.2: deletions in mentally retarded patients without autism and in normal individuals. Eur J Med Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mefford HC, et al. Recurrent rearrangements of chromosome 1q21.1 and variable pediatric phenotypes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1685–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunetti-Pierri N, et al. Recurrent reciprocal 1q21.1 deletions and duplications associated with microcephaly or macrocephaly and developmental and behavioral abnormalities. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1466–71. doi: 10.1038/ng.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharp AJ, et al. Discovery of previously unidentified genomic disorders from the duplication architecture of the human genome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1038–42. doi: 10.1038/ng1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ousley O, Rockers K, Dell ML, Coleman K, Cubells JF. A review of neurocognitive and behavioral profiles associated with 22q11 deletion syndrome: implications for clinical evaluation and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9:148–58. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HG, et al. Disruption of neurexin 1 associated with autism spectrum disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szatmari P, et al. Mapping autism risk loci using genetic linkage and chromosomal rearrangements. Nat Genet. 2007;39:319–28. doi: 10.1038/ng1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodhouse W, et al. Head circumference in autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1996;37:665–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fidler DJ, Bailey JN, Smalley SL. Macrocephaly in autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:737–40. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200001365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Courchesne E, Carper R, Akshoomoff N. Evidence of brain overgrowth in the first year of life in autism. Jama. 2003;290:337–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butler MG, et al. Subset of individuals with autism spectrum disorders and extreme macrocephaly associated with germline PTEN tumour suppressor gene mutations. J Med Genet. 2005;42:318–21. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.024646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dementieva YA, et al. Accelerated head growth in early development of individuals with autism. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;32:102–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Redcay E, Courchesne E. When is the brain enlarged in autism? A meta-analysis of all brain size reports. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lainhart JE, et al. Head circumference and height in autism: a study by the Collaborative Program of Excellence in Autism. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:2257–74. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fukumoto A, et al. Growth of head circumference in autistic infants during the first year of life. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:411–8. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Courchesne E, et al. Mapping early brain development in autism. Neuron. 2007;56:399–413. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mazzucchelli C, et al. Knockout of ERK1 MAP kinase enhances synaptic plasticity in the striatum and facilitates striatal-mediated learning and memory. Neuron. 2002;34:807–20. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00716-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakaguchi G, et al. Doc2alpha is an activity-dependent modulator of excitatory synaptic transmission. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4262–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyazaki T, et al. Disturbance of cerebellar synaptic maturation in mutant mice lacking BSRPs, a novel brain-specific receptor-like protein family. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4057–64. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sebat J, et al. Large-scale copy number polymorphism in the human genome. Science. 2004;305:525–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1098918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diskin SJ, et al. Adjustment of genomic waves in signal intensities from whole-genome SNP genotyping platforms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e126. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grubor V, et al. Novel genomic alterations and clonal evolution in chronic lymphocytic leukemia revealed by representational oligonucleotide microarray analysis (ROMA) Blood. 2009;113:1294–303. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCarroll SA, et al. Integrated detection and population-genetic analysis of SNPs and copy number variation. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1166–74. doi: 10.1038/ng.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooper GM, Zerr T, Kidd JM, Eichler EE, Nickerson DA. Systematic assessment of copy number variant detection via genome-wide SNP genotyping. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1199–203. doi: 10.1038/ng.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deutsch CK. Head Circumference in autism. In: Neisworth J, Wolfe P, editors. Autism and PDD Dictionary. Brookes; Baltimore MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deutsch CK, Farkas LG. Quantitative methods of dysmorphology diagnosis. In: Farkas LG, editor. Anthropometry of the head and face. Raven; New York: 1994. pp. 151–158. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.