Abstract

Although cellular transplantation has been shown to promote improvements in cardiac function following injury, poor cell survival following transplantation continues to limit the efficacy of this therapy. We have previously observed that transplantation of muscle-derived stem cells (MDSCs) improves cardiac function in an acute murine model of myocardial infarction to a greater extent than myoblasts. This improved regenerative capacity of MDSCs is linked to their increased level of antioxidants such as glutathione (GSH) and superoxide dismutase. In the current study, we demonstrated the pivotal role of antioxidant levels on MDSCs survival and cardiac functional recovery by either reducing the antioxidant levels with diethyl maleate or increasing antioxidant levels with N-acetylcysteine (NAC). Both the anti- and pro-oxidant treatments dramatically influenced the survival of the MDSCs in vitro. When NAC-treated MDSCs were transplanted into infarcted myocardium, we observed significantly improved cardiac function, decreased scar tissue formation, and increased numbers of CD31+ endothelial cell structures, compared to the injection of untreated and diethyl maleate–treated cells. These results indicate that elevating the levels of antioxidants in MDSCs with NAC can significantly influence their tissue regeneration capacity.

Introduction

Postnatal stem cells are a promising cell population for regenerative medicine due to their capacity to differentiate into multiple lineages, self-renewal, and be transplanted in an autologous manner. Another putative stem cell characteristic that is of critical importance for cell transplantation is the ability to survive inflammatory and oxidative stresses typically present at the site of injury.1,2 Current research has shown that stem cells are much less susceptible to damage from environmental stresses such as hydrogen peroxide than are differentiated cells.3 The mechanism for this increased stress resistance is not entirely clear, but higher levels of intracellular antioxidants appear to play an important role.4

Higher resistance to oxidative stress has been seen in a variety of stem cell types, including endothelial progenitor cells and cardiac side population cells,5 and has been linked to elevated levels of antioxidants.3,6 Endothelial progenitor cells were shown to be less sensitive to oxidative stress–induced apoptosis, to express significantly higher levels of antioxidant enzymes, and to have increased levels of DNA repair as compared to more differentiated endothelial cells.3,7 Similarly in our studies, muscle-derived stem cells (MDSCs) demonstrate decreased levels of oxidative stress–induced death when compared to myoblasts.8 This observation in MDSCs correlated with increased antioxidant levels including glutathione (GSH) and superoxide dismutase.4 Furthermore, the survival advantage of MDSCs was lost when GSH levels were decreased using the GSH inhibitor, diethyl maleate. Other research has shown that antioxidant treatment can reduce apoptosis in many cell types, including neural and cardiac cells.9,10,11

We hypothesized that increasing the cellular antioxidant levels prior to transplantation could further increase stem cell survival and thereby improve functional repair. In order to further validate that antioxidants directly influence the repair process, we used diethyl maleate (DEM), a nontoxic chemical that conjugates and inactivates GSH, to reduce cellular antioxidant levels,4,8 and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) treatment to increase antioxidant levels. NAC is a synthetic precursor to intracellular cysteine and GSH as well as a direct reactive oxygen species scavenger.12 We found that NAC antioxidant pretreatment led to improved MDSC survival in oxidative stress, whereas DEM pro-oxidant pretreatment led to lower MDSC survival in vitro. We also demonstrated that MDSCs treated with NAC prior to in vivo implantation showed improved therapeutic effect when compared to implanted untreated MDSCs and DEM-pretreated MDSCs. Overall, our results support the hypothesis that the pretreatment of MDSCs with pro- or antioxidant agents impacts cell behavior and consequently affects tissue regeneration and repair capacity after transplantation.

Results

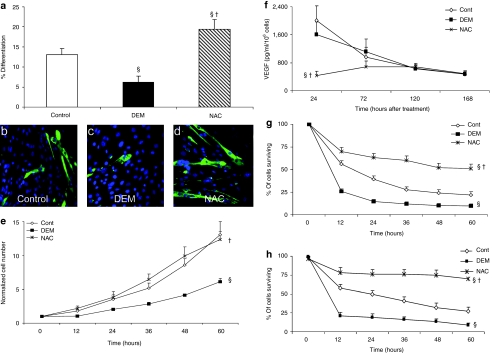

In vitro myogenic differentiation and proliferation of NAC-/DEM-treated MDSCs

NAC-treated MDSCs differentiated into myotubes in vitro to a significantly greater extent than did either the untreated or DEM treated MDSCs (P < 0.05, Figure 1a–d). DEM-treated MDSCs differentiated to a significantly lesser extent than did the untreated MDSCs (Figure 1a, P < 0.05). No difference in the proliferation rate of NAC-treated and untreated MDSCs was observed; however, DEM treatment significantly decreased the MDSCs' proliferation rate as compared to that of the untreated and NAC-treated MDSCs at later time points (Figure 1e, P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

In vitro effects of NAC treatment of muscle-derived stem cells (MDSCs) on myogenic differentiation, VEGF secretion, proliferation, and survival. (a) NAC treatment significantly increased the rate of myogenic differentiation (MHC+ myotube formation in vitro) of MDSCs compared to untreated (control) and DEM-treated MDSCs (mean ± SEM). Statistically significant differences are indicated from §control and from †DEM-treated MDSCs. (b–d) Representative immunostain images of MHC+ myotubes at 5 days (MHC-green, nuclei-blue) (magnification ×40) illustrate increased myogenic differentiation of NAC-treated MDSCs compared to §untreated (control) and †DEM-treated MDSCs. (e) DEM treatment significantly decreased the proliferation rate compared to both the †NAC-treated and §untreated MDSC (control) groups. (f) The impact of 24 hours of NAC and DEM treatment on VEGF secretion of MDSCs was assessed. Time points indicate elapsed time following NAC and DEM treatment. NAC treatment significantly lowered VEGF secretion of the MDSCs 24 hours after treatment compared to both the †DEM-treated and §untreated MDSCs (control) (mean ± SEM, n = 6). However, this significant difference was lost in the 72- to 168-hour time points. (g,h) NAC-treated MDSCs survive inflammatory (10 ng/ml, TNF-α) and oxidative stresses (500 µmol/l, H2O2) at significantly increased rates compared to untreated (§control) and †DEM-treated MDSCs (n = 12). DEM, diethyl maleate; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

VEGF enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay analysis of MDSC conditioned media

Angiogenesis is a key component of the MDSC's repair process after ischemic cardiac injury, in which vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been demonstrated to be an important factor.13 VEGF secretion by the MDSCs was measured at 0, 2, 4, and 6 days following DEM and NAC treatment in vitro to determine the magnitude and duration at which these treatments may affect changes in VEGF secretion. Immediately following the 24-hour NAC or DEM pretreatment (0-hour time point), VEGF levels were significantly decreased in the NAC treatment group as compared to levels for both the untreated and the DEM-treated cells (Figure 1f, P < 0.05); however, at subsequent time points, there was no statistically significant difference among any of the treatment groups (Figure 1f).

In vitro survival of NAC-/DEM-treated MDSCs under oxidative/inflammatory stress conditions

A significantly decreased rate of survival was observed in MDSCs pretreated with DEM when exposed to either oxidative (H2O2, Figure 1g) or inflammatory stressors (TNF-α, Figure 1h) in comparison to the untreated and NAC-treated MDSCs (P < 0.05). In contrast, NAC-treated MDSCs demonstrated a significantly greater rate of survival under both stress conditions than did either the untreated or the DEM-treated MDSCs (Figure 1g,h, P < 0.05).

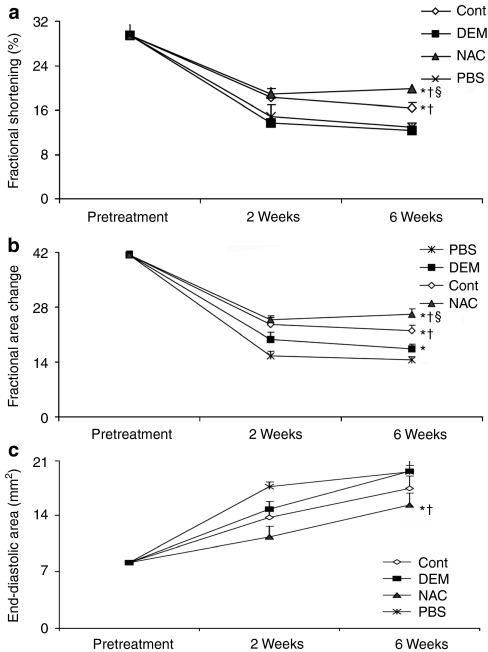

Echocardiographic assessment of cardiac function postinfarction

Significantly improved preservation of systolic function as measured by fractional shortening was observed in hearts injected with NAC-treated MDSCs at the 6-week time point when compared to untreated MDSCs, DEM-treated MDSCs, and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Figure 2a). Measures of fractional area change demonstrated an improved preservation of the fractional area change in hearts injected with NAC-treated MDSCs at 6 weeks postinfarction when compared to hearts injected with DEM-treated MDSCs and PBS (Figure 2b). Similarly, measures of end-diastolic area, a measure of ventricular dilation and a marker of cardiac failure, indicated significantly improved ventricular function of hearts injected with NAC-treated MDSCs, as compared to hearts injected with DEM-treated MDSCs or with PBS (Figure 2c). In summary, all measures of cardiac function indicated that NAC-treated MDSCs generated improved cardiac outcomes when compared to DEM-treated MDSCs and to PBS treatment.

Figure 2.

Echocardiographic evaluation of cardiac function of infarcted hearts following muscle-derived stem cell (MDSC) transplantation. (a) Fractional shortening (FS), a measure of postinfarction contractility, at 6 weeks postinfarction was improved to a significantly greater extent by NAC-treated MDSCs compared to the §untreated MDSCs (control), †DEM-treated, and *PBS injections. Furthermore, DEM-treated MDSCs induced significantly less FS than the †NAC-treated and †untreated (control) MDSCs (P < 0.05, mean ± SEM, n = 10). (b) The NAC-treated MDSC injections yielded a significantly greater fractional area change at 6 weeks than the †DEM-treated MDSCs and *PBS injection groups (n = 10); however, this was not significantly different from the untreated MDSCs (control). (c) NAC-treated MDSC injections mitigated ventricular dilatation as measured by end-diastolic area to a greater extent than the †DEM-treated MDSCs and *PBS injection groups (n = 10). DEM, diethyl maleate; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

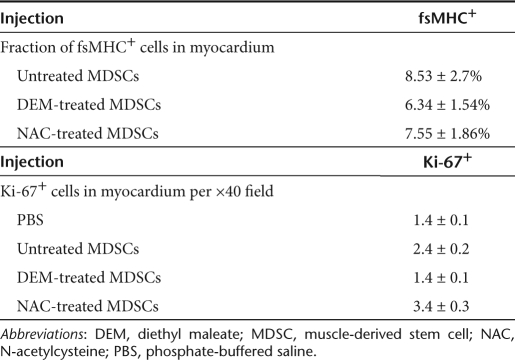

In vivo MDSC engraftment, proliferation, and apoptosis in infarcted myocardium

There were no statistically significant differences in the number of engrafted fsMHC+ cells, measured as a percentage of the total number of cells in the myocardium, observed at 6 weeks postinfarction among the various treatment groups. These measurements are tabulated in Table 1. Hearts injected with NAC-treated MDSCs contained significantly higher numbers of Ki-67+ nuclei per ×40 high-powered field than the hearts injected with untreated MDSCs, DEM-treated MDSCs, or PBS (Table 1). Furthermore, the untreated MDSC injection group had significantly higher numbers of Ki-67+ cells than the DEM or PBS treatment groups. The rates of apoptosis were quantified at the earlier 2-week postinfarction time point. Increased rates of apoptosis were observed in the NAC-treated MDSCs as compared to DEM-treated MDSCs (120 versus 21 TUNEL positive cells per ×40 field, respectively). However, it should be noted that increased LacZ positive cell donor engraftment was observed in hearts injected with NAC-treated MDSCs compared to those injected with DEM-treated MDSCs (81.65 versus 28.75 LacZ+ cells per ×40 field, respectively; data not shown). In light of this engraftment data, the survival rate in the NAC-treated MDSC group was almost three times higher (2.84) than that of the DEM-treated MDSC group. Moreover, it should be noted that the TUNEL stain data include both apoptotic donor and host cells.

Table 1. Evaluation of fsMHC+ and Ki-67+ cells in MDSC transplanted myocardium.

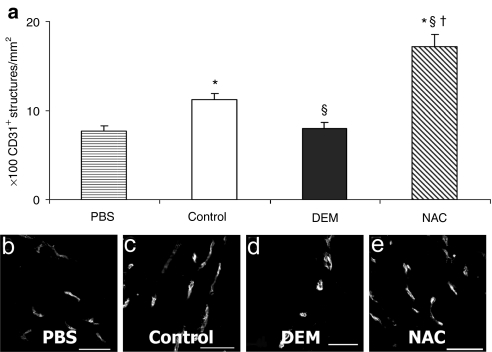

Identification of CD31+ endothelial cells within infarcted myocardium

Hearts injected with NAC-treated MDSCs and isolated at 6 weeks postinfarction yielded significantly increased numbers of CD31+ vascular structures in the peri-infarct area compared to hearts injected with untreated MDSCs, DEM-treated MDSCs, and PBS (Figure 3a). Furthermore, hearts injected with untreated MDSCs yielded significantly increased densities of CD31+ structures over those injected with DEM-treated cells or with PBS (Figure 3a). There was no significant difference between the DEM-treated cell group and the PBS group (Figure 3a). Figure 3b–e are representative micrographs of the CD31 staining (×40 magnification, bar = 50 µm).

Figure 3.

CD31+ cells in infarcted myocardium following muscle-derived stem cell (MDSC) transplantation. (a) Infarcted myocardium injected with NAC-treated MDSCs had significantly more CD31+ endothelial cell structures at 6 weeks after infarction in ×40 magnification fields than the hearts injected with §untreated MDSCs (control), †DEM-treated MDSCs, and *PBS injection groups (P < 0.05, n = 8). (b–e) Representative immunostain images of CD31+ cell structures (white: CD31+) in the peri-infarct area (bar = 50 µm). DEM, diethyl maleate; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

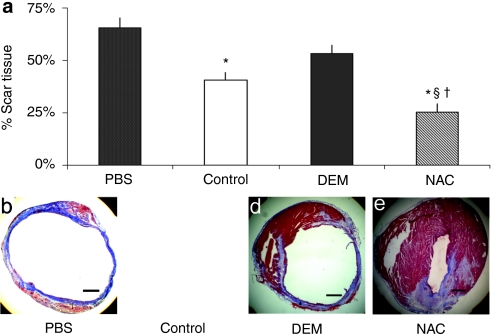

Scar tissue formation in infarcted myocardium

Cryosections of the hearts at 6 weeks postinfarction were stained with Masson's trichrome to quantify the percentage of scar tissue area to the total cardiac muscle area in the left ventricle. Hearts injected with NAC-treated MDSCs yielded a significantly lower percentage area of collagenous scar than hearts injected with untreated MDSCs, DEM-treated MDSCs, and PBS (Figure 4a). Hearts injected with untreated MDSCs generated significantly less scar tissue than did hearts injected with PBS, but were not significantly different from the DEM treatment group (Figure 4a). There was no significant difference in myocardial scar between hearts injected with DEM-treated MDSCs and those injected with PBS (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Scar tissue formation in infarcted myocardium following muscle-derived stem cell (MDSC) transplantation. (a) The myocardium injected with NAC-treated MDSCs generated less scar tissue when compared to injections with §untreated MDSCs (control), †DEM-treated MDSCs, and *PBS (P > 0.05, n = 8). Scar area percentage was determined by trichrome staining of collagenous scar area as a percentage of total myocardium area in a longitudinal cross-section. Myocardium injected with untreated MDSCs (control) demonstrated lower levels of scar tissue formation than did the *PBS injection group (P = 0.09). (b–e) Representative images of trichrome stains (collagen: blue, muscle: red) illustrate the decreased area of scar in the NAC-treated MDSC-injected myocardium (bar = 500 µm). DEM, diethyl maleate; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

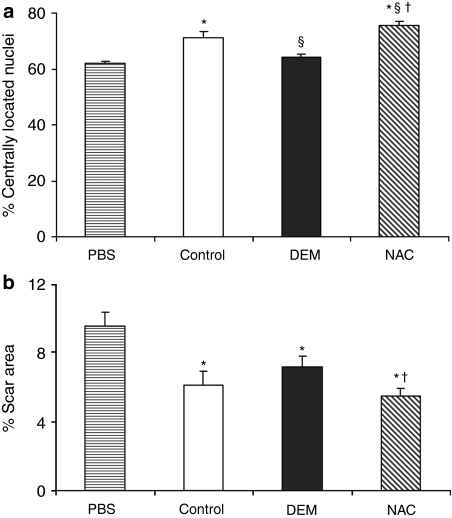

Regeneration and scar tissue formation in injured skeletal muscle

Significant increases in host regeneration, as measured by the percentage of centrally nucleated muscle fibers, was observed in skeletal muscles injected with NAC-treated MDSCs in comparison to all other muscle injection groups (Figure 5a). Other group comparisons yielded significant differences in host regeneration as follows: significantly greater percentages of centrally located nuclei were observed in muscles injected with untreated MDSCs than in those injected with DEM-treated MDSCs or with PBS; no significant difference in host regeneration was observed between muscles injected with DEM-treated MDSCs and those injected with PBS. Trends in scar tissue formation were the inverse of the trends observed in host muscle regeneration. That is, muscles injected with NAC-treated MDSCs generated significantly less scar than those injected with DEM-treated MDSCs or with PBS, and there was no significant difference in scar area observed between muscles injected with DEM-treated MDSCs and those injected with PBS. It should be noted that the trends in scar tissue formation in the injured skeletal muscle were identical to those seen in the myocardial infarction model.

Figure 5.

Regeneration of injured skeletal muscle following muscle-derived stem cell (MDSC) transplantation. (a) Host regeneration after injury, determined by percentage of centrally nucleated myofibers, is increased following injection of NAC-treated MDSCs when compared to §untreated MDSCs (control), †DEM-treated MDSCs, and *PBS (P > 0.05, n = 8). A significant increase in muscle regeneration was induced by untreated MDSCs (control) compared to †DEM-treated MDSCs and *PBS (n = 6). (b) Measurements of the area of collagenous scar formation after cardiotoxin injury followed an inverse trend of that observed in host regeneration. Significantly decreased scar formation was observed in muscle injected with NAC-treated MDSCs compared to DEM-treated †MDSCs and *PBS, but not to the untreated MDSCs (control). DEM, diethyl maleate; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

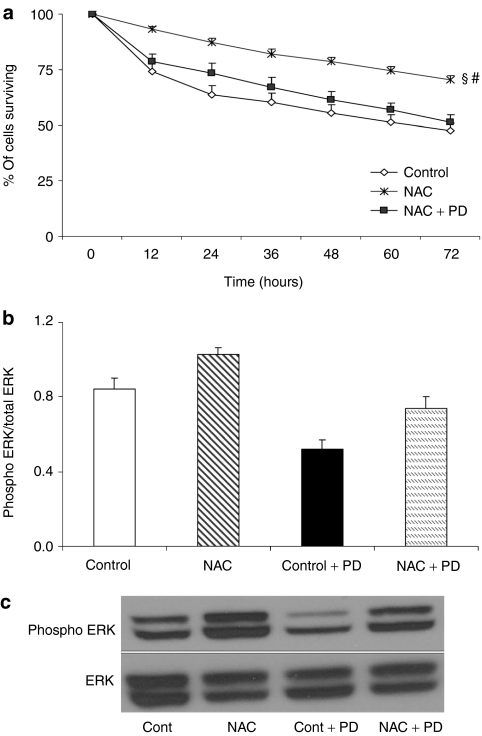

MDSC survival after ERK inhibition in vitro

Under oxidative stress conditions (H2O2 exposure), the inhibition of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway, using PD, caused a significant decrease in the cell survival of NAC-treated MDSCs compared to uninhibited NAC-treated MDSCs (Figure 6a). In fact, PD inhibition of NAC-treated MDSCs reduced survival rates to levels similar to those observed in the untreated MDSCs (Figure 6a). PD inhibition of the ERK pathway in untreated MDSCs also significantly reduced MDSC survival rates when compared to rates of uninhibited, untreated MDSCs. Western blot analysis further confirmed the reduction of ERK phosphorylation after treatment with PD (Figure 6b,c).

Figure 6.

In vitro inhibition of ERK by PD98059 reduces NAC-treated muscle-derived stem cell (MDSC) survival in oxidative stress conditions. (a) The inhibition of ERK signaling using PD98059 significantly reduced §NAC-treated MDSC cell survival in oxidative stress (500 µmol/l, H2O2) to levels observed in the untreated MDSCs (control) (mean ± SEM, n = 9). NAC-treated MDSCs had significantly increased survival rates when compared to the §untreated MDSCs (control) and #NAC/PD-treated MDSCs. (b,c) Western blot analysis demonstrated the efficacy of PD98059 treatment in reducing ERK 1/2 phosphorylation both in untreated MDSCs (control) and NAC-treated MDSCs (n = 2). Although NAC-treated MDSCs demonstrated elevated ERK phosphorylation compared to untreated (control) and PD-treated MDSCs, this phosphorylation was reduced to control levels when NAC-treated MDSCs were simultaneously treated with PD. NAC, N-acetylcysteine.

Discussion

Heart failure is the leading cause of death in both men and women, and cell therapy is a promising method of treating this serious disease; yet many challenges must be overcome to make cell therapy a safe and effective procedure for treating injured myocardium. Current limitations in therapeutic efficacy are due, in part, to poor survival of the transplanted donor cells that has been observed in multiple cell types and injury models. This poor survival can be attributed to the hostile environment to which the cells are introduced that is both ischemic and may contain activated inflammatory cells and cytokines. Other factors playing a role in the cells ability to survive include the delivery method of the cells, and the lack of survival signals that the cells are exposed to such as the cell interaction with the intracellular matrix, cell–cell interactions, and Akt phosphorylation.14

We have previously identified a population of skeletal muscle–derived progenitor cells, MDSCs, which are easily accessible and multipotent, and which proliferate long-term and survive under stressful conditions at significantly higher rates than do myoblasts.4,8,15,16,17 Although these MDSCs repair skeletal and cardiac muscles more effectively than do more differentiated muscle cells such as myoblasts, the repair process remains limited. MDSCs were shown to have increased levels of antioxidants compared to myoblasts and lower levels of apoptosis when cultured under oxidative and inflammatory stress. In fact, resistance to stress has been demonstrated as a common characteristic among adult and embryonic stem cells.1,2 We therefore believe that treatments capable of further increasing stem cell survival after transplantation, through an increased resistance to stress, would have significant therapeutic benefits for tissue regeneration and repair.

Antioxidant levels are tightly regulated within the cell, and a small change in the redox state can significantly affect cell behavior, stem cell characteristics, and survival.9 Cells at the site of tissue injury experience oxidative and inflammatory stresses, which can lead to cellular senescence and/or apoptosis. NAC is a direct antioxidant and a cysteine precursor of GSH synthesis.18 Previous research has shown that NAC treatment decreases cell death caused by extrinsic stresses and loss of trophic factors,10 protects against oxidative stress both in vitro and in vivo,18,19 and has antifibrotic effects.20 NAC is used clinically to treat acetaminophen toxicity, acute liver failure, and diseases characterized by low GSH levels.18,21,22,23,24

We hypothesized that increasing the cellular antioxidant levels of MDSCs prior to their transplantation could increase cell survival and thereby improve functional repair. In order to validate this hypothesis, we treated cells with DEM, a nontoxic chemical that binds to GSH and inactivates it, to reduce antioxidant levels,4,8 and with NAC, a direct antioxidant and GSH precursor, to increase antioxidant levels. The results demonstrated that MDSCs treated with NAC prior to implantation have a therapeutic advantage in repairing skeletal and cardiac muscles compared to untreated and DEM-treated MDSCs. This was shown by a significant increase in cardiac function parameters in the NAC-treated MDSC group, indicating that MDSCs with chemically increased antioxidant levels, transplanted into a murine infarcted heart, can improve function as compared to MDSCs with chemically reduced levels of antioxidants or untreated MDSCs.

One possible reason for this increase in function is that in vitro NAC-treated MDSCs have consistently shown an increase in their ability to survive. We have demonstrated that pro- and antioxidant treatments impact cell survival and the differentiation capacity of the MDSCs in vitro under oxidative and inflammatory stresses, which is likely a way in which donor cells protect against apoptosis.25

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family of protein kinases, including ERK, influences a wide variety of cellular mechanisms, including survival and proliferation.26,27 Blocking the ERK 1/2 signaling pathway has been shown to decrease cell viability in cardiac stem cells, and to protect against induced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes.24,28,29 More relevant to the current study is that NAC has been shown to activate the ERK pathway and to inhibit the activation of downstream signals, including the nuclear factor-κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B-cells (NFκB).24,30,31,32 In this study, we confirmed the role of NAC in increasing MAPK activation in the MDSCs. Further, we examined the role of MAPK in the increased survival of NAC-treated MDSCs and observed a loss of survival advantage in NAC-treated MDSCs when MAPK signaling was inhibited by PD98059. This result provides further evidence that MAPK signaling is an important component of the increased survival of NAC-treated cells in general and of MDSCs in particular. Further investigation of NAC and its role in affecting downstream signaling pathways is needed to clarify the prosurvival mechanism of NAC.

There were no significant differences observed between the NAC-, DEM-treated, and untreated MDSCs in their secretion of VEGF at the 72-, 120-, and 168-hour time points after treatment; however, there was an initial decrease in VEGF secretion by the NAC-treated cells at the 24-hour time point. NAC treatment has been shown to decrease VEGF secretion in a variety of cell types including human keratinocytes and human melanoma cell lines33,34 and has been shown to have antiangiogenic properties in a model of breast carcinoma.35 In the present study using an acute myocardial infarction model, NAC-treated MDSCs yielded an increased CD31+ endothelial structure density and reduced harmful fibrotic remodeling despite the in vitro result of an initial inhibition of VEGF secretion. Although apparently NAC transiently decreased VEGF secretion of the MDSCs, the more important impact of NAC during this 24-hour time frame in vivo appears to be the increase in the survival rate imparted on the donor MDSCs, which have been shown previously to improve myocardial regeneration in an acute myocardial infarction model.13 The increased number of viable donor MDSCs could also explain the increase in the formation of CD31+ endothelial structures. It is also possible that the NAC-treated MDSCs increased the number of CD31+ structures more effectively in vivo by influencing the secretion of angiogenic factors other than VEGF, such as fibroblast growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, the angiopoietins, and the matrix metalloproteinases. Furthermore, increased Ki-67 positivity in the infarcted myocardium suggests that NAC-treated MDSCs may increase host and donor cell proliferation. Proliferating myocytes, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells have been reported after transplantation of bone marrow cells into myocardium.36 There likely exists a relationship between the cells' ability to survive and proliferate and subsequent paracrine factor secretion, both being critical to successful cell therapy.37,38

The events leading to fibrotic remodeling in the infarcted myocardium are complex and remain to be fully elucidated; however, ischemia, inflammation, and cell death (via necrosis and apoptosis) have been implicated. As discussed previously, stimulation of angiogenesis and upregulation of prosurvival signals such as MAPK may mitigate fibrotic remodeling. In hearts injected with NAC-treated MDSCs, a significant decrease in scar tissue formation was observed when compared to those injected with untreated MDSCs and DEM-treated MDSCs. Moreover, the untreated MDSCs had significantly lower levels of scar tissue formation than the DEM-treated MDSCs. These results may indicate that increased rates of donor MDSC survival allows the cells to go on to play a significant paracrine role in attenuating fibrosis, promoting angiogenesis, and mitigating ischemia. Similar results were obtained in the skeletal muscle injury model where increased host regeneration and reduced scar tissue formation were seen in the NAC-treated MDSC group compared to the other groups. These results highlight the beneficial effects of antioxidant pretreatment on the ability of MDSCs to increase the number of CD31+ cells, decrease scar tissue formation and, ultimately, preserve the cardiac function of mice that have experienced myocardial infarction.

NAC treatment has previously been used in animal models of ischemia-reperfusion injury with encouraging results.21 In the current study, we have shown that pretreating MDSCs with pro- or antioxidants changes the survival capacity of the cells when exposed to oxidative and inflammatory stresses in vitro. Moreover, when injected into infarcted hearts or injured skeletal muscle of SCID mice, the treated MDSCs may positively influence the repair process. These results suggest that, although MDSCs already have higher antioxidant levels than differentiated cells, further benefit can still be gained through the use of antioxidant pretreatment, and that cell survival plays an important role in functional tissue repair. Treatment with antioxidants is an attractive option for improving cell transplantation, in particular, treatment with NAC because it has been used clinically for other purposes for many years.

To further validate the benefits of antioxidant pretreatment, other antioxidants need to be tested in conjunction with this type of cellular therapy. Enhancing the activity of superoxide dismutase could also provide support for the indication that increased antioxidant activity influences stem cell behavior and the capacity for regeneration and repair after transplantation.39,40 We are currently investigating the utility of sorting muscle-derived progenitors to isolate sub-populations based on the markers of increased antioxidant capacity such as aldehyde dehydrogenase.41 Reactive oxygen species are increasingly recognized as important signaling molecules involved in gene transcription, proliferation, differentiation, and DNA damage.42 Further work is required to determine all the contributing factors involved with antioxidant treatment and subsequent reactive oxygen species modulation. We are also investigating whether these treatments can influence the survival and regenerative property of more differentiated and less stress-resistant muscle cells such as myoblasts because these cells have been widely tested in clinical trials for both skeletal and cardiac muscle repair.

Materials and Methods

Animal studies. The use of animals and the surgical procedures performed in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh (protocol 14/06).

Murine MDSC isolation. MDSCs were isolated from the skeletal muscle of 3-week-old female C57BL mice (Jackson, Bar Harbor, ME) using a modified preplate technique as previously described.15,43,44,45 MDSCs were cultured in proliferation medium (PM) containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 10% horse serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 0.5% chick embryo extract (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, NY).

Myogenic differentiation of NAC-/DEM-treated MDSCs. DEM-treated, NAC-treated, and untreated MDSCs were examined for their myogenic differentiation and fusion capacities by culturing the cells in differentiation medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 2% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin) containing either DEM (50 µmol/l; Sigma, St Louis, MO), NAC (10 mmol/l; Sigma), or no additional supplement. MDSCs were plated at a density of 5,000 cells per well on a 24-well collagen type I coated plate in PM. After 24 hours, the medium was replaced with one of the three treatment groups described above. After 5 days of differentiation medium culture, the plates were stained with mouse antifast skeletal myosin heavy chain antibody (fsMHC, 1:400; Sigma) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (for nuclei), and the ratio of nuclei in fsMHC+ myotubes to total nuclei was quantified to assess myogenic differentiation.

Cell survival under oxidative/inflammatory stress. Cell proliferation and survival were assessed using a live cell imaging system (Kairos Instruments, Pittsburgh, PA) employing bright-field imaging to assess cell number and fluorescent imaging of propidium iodide infiltration to assess cell death.46 MDSCs were plated in PM at a density of 1,000 cells/well in a 24-well collagen type I coated plate and the wells were divided into three treatment groups: (i) PM only, (ii) PM supplemented with 50 µmol/l DEM, and (iii) PM supplemented with 10 mmol/l NAC. These treatment groups were then additionally supplemented with either hydrogen peroxide (500 µmol/l H2O2; Sigma) (oxidative stress), tumor necrosis factor-α (10 ng/ml, TNF-α R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) (inflammatory stress) or not exposed to any stressing agent. All wells were also supplemented with propidium iodide (2 µg/ml; Sigma) in order to identify the dead cells. It should be noted that 500 µmol/l H2O2 is a physiologically high concentration compared to levels observed in vivo during inflammation (~5 µmol/l). This increased concentration of H2O2 is used in vitro to compensate for the lack of other reactive oxygen species and proinflammatory cytokines observed in the context of inflammation that would otherwise potentiate apoptosis. Fluorescent and bright-field images were taken every 10 minutes in three locations per well for a period of 60 hours. All images were analyzed using ImageViewer software (Kairos Instruments). Cell proliferation and cell death were quantified at successive 12-hour time points over a 60-hour time period.

Analysis of VEGF secretion. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay analysis of VEGF secretion by cultured MDSCs was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) as previously described.13 MDSCs were plated in PM at a density of 50,000 cells/well in 6-well collagen type I coated plates and pretreated in PM only (control), PM with 50 µmol/l DEM, or PM with 10 mmol/l NAC for 24 hours. Subsequently, VEGF secretion by the MDSCs was collected in serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 1% penicillin/streptomycin for a period of 24 hours at the time points of 24, 72, 120, and 168 hours following the pretreatment. However, for those time points >24 hours, MDSCs were cultured in normal PM prior to the 24-hour serum-free collection period and following the 24-hour NAC and DEM pretreatment. Therefore, the time points reflect the elapsed time following pretreatment to the time of collection for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay analysis. The VEGF levels were normalized to cell number, which was assessed manually using a hemocytometer.

MDSC transplantation into infarcted myocardium. An acute infarction model was used to assess the cardiac transplantation efficacy of NAC-treated, DEM-treated, and untreated MDSCs. Fifty male immunodeficient, SCID mice (B6.CB17-Prkdcscid/SzJ; Jackson, Bar Harbor, ME) at 14–18 weeks of age underwent permanent left anterior descending coronary artery ligation using a 7-0 prolene suture to create a myocardial infarction as previously described.8,13,47 Five minutes after the creation of the infarction, the mice (n = 12–14) received a 30 µl injection of one of the following: (i) PBS, (ii) 3 × 105 NAC-treated MDSCs in PBS, (iii) 3 × 105 DEM-treated MDSCs in PBS, or (iv) 3 × 105 untreated MDSCs in PBS. All treated MDSCs received NAC (10 mmol/l) or DEM (50 µmol/l) modified PM pretreatments for 24 hours prior to injection. These groups were further subdivided into 2-week and 6-week sacrifice time points for immunohistochemical characterization of the infarcted myocardium. The MDSCs were retrovirally transduced to express LacZ using a previously described protocol22 and used in the 2-week time point animals. Nontransduced MDSCs were used in the animals for the 6-week time point. Although in the current study, only female-derived MDSCs were used, we would not expect a selective advantage between male and female MDSC treatment groups following cardiac injury.47 Longitudinal echocardiography was performed in each mouse prior to cell transplantation and at 2 and 6 weeks after the cell transplantation. Left ventricular area and contractile function were assessed at the left ventricular short axis at the midpapillary muscle level as described previously.8,13 Subsequently, the hearts were harvested, flash-frozen in 2-methylbutane, and cryosectioned for immunohistochemical analyses.

Identification of CD31+ endothelial cells within the infarct area. The density of CD31+ endothelial cell structures in the infarct area at the 6-week postinfarction time point was assessed by immunofluorescence staining of cryosectioned myocardium. Although the CD31+ cell structures observed in this study often bore the hallmarks of functional vasculature, such as a lumen and the appearance of blood cells, their functionality as blood vessels could not be verified in all cases. Therefore, we report only the density of CD31+ structures rather than blood vessel density. CD31+ cell structures were visualized using a rat anti-CD31 primary antibody (1:300; Sigma) and donkey anti-rat Alexafluor 594 secondary antibody (1:300, Sigma). CD31+ structures in ×40 magnification fields were quantified in three randomly chosen areas of the infarct area and reported as the number of CD31+ structures per mm2.

Assessment of myocardial fibrosis following infarction. Myocardial fibrosis at 6 weeks postinfarction was quantified using Masson trichrome stain and assessing the area of collagenous scar in five sections of myocardium in each infarcted heart. Heart sections were fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde for 2 minutes and stained with the Masson modified IMEB trichrome stain kit (IMEB, San Marcos, CA), which stains both collagen (blue) and muscle (red).8,13,47 Fibrosis was quantified by measuring the area of collagenous scar as a percentage of overall myocardial area using ImageJ visualization software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

MDSC proliferation and apoptosis following transplantation to infarcted myocardium. Donor MDSC proliferation was quantified by immunohistochemical staining of Ki-67 in three ×40 fields of injected myocardium at the 6-week postinfarction time point. Cryosectioned tissue was stained using rabbit anti-Ki-67 primary antibodies (1:250; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and Alexafluor 555 secondary goat anti-rabbit antibodies (1:200; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Sections were co-stained with mouse anti-fsMHC antibodies (1:400; Sigma) and Alexafluor 488 donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:300; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Apoptosis was quantified by terminal dUPT nick end-labeling (TUNEL). Staining was performed on the injected myocardium at the 2-week postinfarction time point according to the manufacturer's protocol (ApopTag Plus Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit; Chemicon, Billerica, MA). The samples were counter-stained with hematoxylin. The total number of apoptotic cells was quantified in five microscopic fields at ×20 magnification.

MDSC transplantation into injured skeletal muscle. Treated and untreated MDSCs (1 × 105 cells) were injected into the gastrocnemius muscles of male mdx mice (n = 20) following cardiotoxin injury. Two weeks following cardiotoxin injection (1 µg in 20 µl PBS), the injured skeletal muscles were randomly allocated among three treatment groups: (i) 20 µl PBS, untreated MDSCs, (ii) NAC-treated MDSCs, or (iii) DEM-treated MDSCs. The three MDSC treatment conditions were identical to those used in the cardiac infarction model. The mice were killed at 2 weeks following cell injection, The muscles were harvested, flash-frozen in 2-methylbutane, and cryosectioned.

Quantification of host regeneration and CD31+ endothelium in injured skeletal muscle. Muscle regeneration was assessed by counting the numbers of centrally nucleated myofibers. Three randomly chosen microscopic fields were assessed at ×20 magnification for each muscle. Cryosections were fixed in 10% formalin and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin to visualize the muscle fibers and their nuclei. The number of CD31+ cells as a ratio of engrafted MDSCs was determined by co-staining with CD31 and dystrophin as described previously.13,48,49

Inhibition of the ERK pathway. Given the role of ERK signaling in oxidative stress–mediated apoptosis, the role of ERK/MAPK signaling following NAC and DEM treatment was evaluated.50 An ERK/MAPK inhibitor, PD98059 (PD) (ERK/MAPK inhibitor; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) was used to determine whether ERK/MAPK signal inhibition would attenuate the prosurvival effects of NAC. PD is a selective noncompetitive inhibitor of MEK1 activation, which inhibits the subsequent phosphorylation and activation of MAP kinase. Its inhibition of MEK2 is less effective; thus, whereas its MAPK/ERK inhibition is significant, it is not complete.51 Cells were plated in PM at 1,000 cells/well in a 24-well collagen type I coated plate. After 24 hours, the medium was switched to PM supplemented with propidium iodide (2 µg/ml) with half of the wells being treated with 500 µmol/l hydrogen peroxide. These two groups (PM or PM with peroxide) were further split into three pretreatment groups (n = 3) including (i) untreated cells, (ii) 10 mmol/l NAC-treated cells, and (iii) 10 mmol/l NAC- and 25 µmol/l PD-treated cells. The plates were then placed onto a live cell imaging system to quantify cell proliferation and survival as previously described.

Assessment of ERK activation/phosphorylation by western blot analysis. Changes in ERK phosphorylation following PD and NAC pretreatments were confirmed by western blotting. MDSCs plated on collagen type I coated culture flasks for 24 hours were treated for 15 minutes with 25 µmol/l PD, 10 mmol/l NAC, 10 mmol/l NAC, and 25 µmol/l PD, or left untreated. Total cell extracts were separated using NE-PER kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL), and 20 µg of protein were separated by electrophoresis on a 10–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to immunoblot polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (0.2 µmol/l; Bio-Rad Labs, Hercules, CA). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in 0.1% TBS-T and subsequently probed with antibodies directed against phosphor-p44/42 and p44/42 (1:500; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) for 2 hours at room temperature. After washing, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:10,000; Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA). Proteins were detected by application of the Super-Signal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate to the membranes (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Blots were stripped with IgG elution buffer (Pierce Biotechnology) for reprobing. Densitometric analysis of the bands was done using ImageJ.

Microscopy. Fluorescence and bright-field microscopy were performed using either a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) equipped with a Retiga digital camera (QImaging, Surrey, British Columbia, Canada) and Northern Eclipse software (v6.0; Empix Imaging, Cheektowaga, NY) or a Leica DMIRB inverted microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a Retiga digital camera and Northern Eclipse software. Image analysis was performed using Northern Eclipse software or Image J.

Statistical analysis. The means and standard deviations were calculated for all measured values, and statistical significance between the groups was determined by one-way analysis of variance (SigmaStat; Systat Software, San Jose, CA). In the event of a significant analysis of variance, the appropriate multiple comparisons test was used for post hoc analysis (Tukey test).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to J.H. from the NIH (IU54AR050733-01, HL 069368), the William F. and Jean W. Donaldson Endowed Chair in Pediatric Orthopaedic Surgery, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, the Henry J. Mankin Endowed Chair for Orthopaedic Research at the University of Pittsburgh, and the Orris C. Hirtzel and Beatrice Dewey Hirtzel Memorial Foundation. This work was also supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the NIH to L.D. (T32 EB001026-05). We also thank James H. Cummins and Barbara Edelman for their editorial assistance in preparing the final version of this manuscript. Declaration of potential conflicts of interest: J.H. has received consulting fees and royalty payments from Cook MyoSite during the period of time in which this project was performed.

REFERENCES

- Singh A, Lee KJ, Lee CY, Goldfarb RD., and, Tsan MF. Relation between myocardial glutathione content and extent of ischemia-reperfusion injury. Circulation. 1989;80:1795–1804. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.6.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Murtuza B, Beauchamp JR, Smolenski RT, Varela-Carver A, Fukushima S, et al. Dynamics and mediators of acute graft attrition after myoblast transplantation to the heart. FASEB J. 2004;18:1153–1155. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1308fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dernbach E, Urbich C, Brandes RP, Hofmann WK, Zeiher AM., and, Dimmeler S. Antioxidative stress-associated genes in circulating progenitor cells: evidence for enhanced resistance against oxidative stress. Blood. 2004;104:3591–3597. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urish KL, Vella JB, Okada M, Deasy BM, Tobita K, Keller BB, et al. Antioxidant levels represent a major determinant in the regenerative capacity of muscle stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:509–520. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CM, Ferdous A, Gallardo T, Humphries C, Sadek H, Caprioli A, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha transactivates Abcg2 and promotes cytoprotection in cardiac side population cells. Circ Res. 2008;102:1075–1081. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho-Santos M, Yoon S, Matsuzaki Y, Mulligan RC., and, Melton DA. “Stemness”: transcriptional profiling of embryonic and adult stem cells. Science. 2002;298:597–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1072530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T, Peterson TE, Holmuhamedov EL, Terzic A, Caplice NM, Oberley LW, et al. Human endothelial progenitor cells tolerate oxidative stress due to intrinsically high expression of manganese superoxide dismutase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2021–2027. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000142810.27849.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima H, Payne TR, Urish KL, Sakai T, Ling Y, Gharaibeh B, et al. Differential myocardial infarct repair with muscle stem cells compared to myoblasts. Mol Ther. 2005;12:1130–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.07.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Ladi E, Mayer-Proschel M., and, Noble M. Redox state is a central modulator of the balance between self-renewal and differentiation in a dividing glial precursor cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10032–10037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.170209797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demiralay R, Gürsan N., and, Erdem H. The effects of erdosteine, N-acetylcysteine and vitamin E on nicotine-induced apoptosis of cardiac cells. J Appl Toxicol. 2007;27:247–254. doi: 10.1002/jat.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M., and, Noble M. N-acetyl-l-cysteine is a pluripotent protector against cell death and enhancer of trophic factor-mediated cell survival in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7496–7500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd S, Dean O, Copolov DL, Malhi GS., and, Berk M. N-acetylcysteine for antioxidant therapy: pharmacology and clinical utility. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:1955–1962. doi: 10.1517/14728220802517901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne TR, Oshima H, Okada M, Momoi N, Tobita K, Keller BB, et al. A relationship between vascular endothelial growth factor, angiogenesis, and cardiac repair after muscle stem cell transplantation into ischemic hearts. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1677–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DA., and, Zenovich AG. Cell therapy for left ventricular remodeling. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2007;4:3–10. doi: 10.1007/s11897-007-0019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu-Petersen Z, Deasy B, Jankowski R, Ikezawa M, Cummins J, Pruchnic R, et al. Identification of a novel population of muscle stem cells in mice: potential for muscle regeneration. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:851–864. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao B, Zheng B, Jankowski RJ, Kimura S, Ikezawa M, Deasy B, et al. Muscle stem cells differentiate into haematopoietic lineages but retain myogenic potential. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:640–646. doi: 10.1038/ncb1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsic N, Mamaeva D, Lamb NJ., and, Fernandez A. Muscle-derived stem cells isolated as non-adherent population give rise to cardiac, skeletal muscle and neural lineages. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:1266–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowska AM, Manuel-Y-Keenoy B., and, De Backer WA. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory efficacy of NAC in the treatment of COPD: discordant in vitro and in vivo dose-effects: a review. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2007;20:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price TO, Uras F, Banks WA., and, Ercal N. A novel antioxidant N-acetylcysteine amide prevents gp120- and Tat-induced oxidative stress in brain endothelial cells. Exp Neurol. 2006;201:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marian AJ, Senthil V, Chen SN., and, Lombardi R. Antifibrotic effects of antioxidant N-acetylcysteine in a mouse model of human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:827–834. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe M, Takiguchi Y, Ichimaru S, Tsuchiya K., and, Wada K. Comparison of the protective effect of N-acetylcysteine by different treatments on rat myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;106:571–577. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0071664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sochman J. N-acetylcysteine in acute cardiology: 10 years later: what do we know and what would we like to know?! J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1422–1428. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01797-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna G, Diwan V, Singh M, Singh N., and, Jaggi AS. Reduction of ischemic, pharmacological and remote preconditioning effects by an antioxidant N-acetyl cysteine pretreatment in isolated rat heart. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2008;128:469–477. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.128.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafarullah M, Li WQ, Sylvester J., and, Ahmad M. Molecular mechanisms of N-acetylcysteine actions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:6–20. doi: 10.1007/s000180300001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paranjpe A, Cacalano NA, Hume WR., and, Jewett A. N-acetylcysteine protects dental pulp stromal cells from HEMA-induced apoptosis by inducing differentiation of the cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:1394–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bironaite D, Baltriukiene D, Uralova N, Stulpinas A, Bukelskiene V, Imbrasaite A, et al. Role of MAP kinases in nitric oxide induced muscle-derived adult stem cell apoptosis. Cell Biol Int. 2009;33:711–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim GH, Song DK, Cho CH, Yoo SK, Kim DK, Park GY, et al. Muscular cell proliferative and protective effects of N-acetylcysteine by modulating activity of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase. Life Sci. 2006;79:622–628. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreka P, Zang J, Dougherty C, Slepak TI, Webster KA., and, Bishopric NH. Cytoprotection by Jun kinase during nitric oxide-induced cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Circ Res. 2001;88:305–312. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai-Kanai E, Hasegawa K, Fujita M, Araki M, Yanazume T, Adachi S, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor protects cardiac myocytes from iNOS-mediated apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 2002;190:54–62. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kin H, Wang NP, Halkos ME, Kerendi F, Guyton RA., and, Zhao ZQ. Neutrophil depletion reduces myocardial apoptosis and attenuates NFkappaB activation/TNFalpha release after ischemia and reperfusion. J Surg Res. 2006;135:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staal FJ, Roederer M, Herzenberg LA., and, Herzenbergm LA. Intracellular thiols regulate activation of nuclear factor kappa B and transcription of human immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9943–9947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloire G, Legrand-Poels S., and, Piette J. NF-kappaB activation by reactive oxygen species: fifteen years later. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:1493–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redondo P, Jimenez E, Perez A., and, García-Foncillas J. N-acetylcysteine downregulates vascular endothelial growth factor production by human keratinocytes in vitro. Arch Dermatol Res. 2000;292:621–628. doi: 10.1007/s004030000187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redondo P, Bandrés E, Solano T, Okroujnov I., and, García-Foncillas J. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and melanoma. N-acetylcysteine downregulates VEGF production in vitro. Cytokine. 2000;12:374–378. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A, Muñoz-Nájar U, Klueh U, Shih SC., and, Claffey KP. N-acetyl-cysteine promotes angiostatin production and vascular collapse in an orthotopic model of breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1683–1696. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63727-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Jakoniuk I, Anderson SM, Li B, et al. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410:701–705. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbiser JL, Petros J, Klafter R, Govindajaran B, McLaughlin ER, Brown LF, et al. Reactive oxygen generated by Nox1 triggers the angiogenic switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:715–720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022630199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albini A, Morini M, D'Agostini F, Ferrari N, Campelli F, Arena G, et al. Inhibition of angiogenesis-driven Kaposi's sarcoma tumor growth in nude mice by oral N-acetylcysteine. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8171–8178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mysore TB, Shinkel TA, Collins J, Salvaris EJ, Fisicaro N, Murray-Segal LJ, et al. Overexpression of glutathione peroxidase with two isoforms of superoxide dismutase protects mouse islets from oxidative injury and improves islet graft function. Diabetes. 2005;54:2109–2116. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottino R, Balamurugan AN, Tse H, Thirunavukkarasu C, Ge X, Profozich J, et al. Response of human islets to isolation stress and the effect of antioxidant treatment. Diabetes. 2004;53:2559–2568. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.10.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vella JB, Bucsek MJ., and, Huard J. 56th Annual Meeting of the Orthopedic Research Society. New Orleans, LA; 2010. The use of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) expression as a marker for muscle derived cells endowed with high survival and myogenic potential. [Google Scholar]

- Pervaiz S, Taneja R., and, Ghaffari S. Oxidative stress regulation of stem and progenitor cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2777–2789. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huard J, Cao B., and, Qu-Petersen Z. Muscle-derived stem cells: potential for muscle regeneration. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2003;69:230–237. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deasy BM, Gharaibeh BM, Pollett JB, Jones MM, Lucas MA, Kanda Y, et al. Long-term self-renewal of postnatal muscle-derived stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3323–3333. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharaibeh B, Lu A, Tebbets J, Zheng B, Feduska J, Crisan M, et al. Isolation of a slowly adhering cell fraction containing stem cells from murine skeletal muscle by the preplate technique. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1501–1509. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt BT, Feduska JM, Witt AM., and, Deasy BM. Robotic cell culture system for stem cell assays. Ind Rob. 2008;35:116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Drowley L, Okada M, Payne TR, Botta GP, Oshima H, Keller BB, et al. Sex of muscle stem cells does not influence potency for cardiac cell therapy. Cell Transplant. 2009;18:1137–1146. doi: 10.3727/096368909X471305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne TR, Oshima H, Sakai T, Ling Y, Gharaibeh B, Cummins J, et al. Regeneration of dystrophin-expressing myocytes in the mdx heart by skeletal muscle stem cells. Gene Ther. 2005;12:1264–1274. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deasy BM, Feduska JM, Payne TR, Li Y, Ambrosio F., and, Huard J. Effect of VEGF on the regenerative capacity of muscle stem cells in dystrophic skeletal muscle. Mol Ther. 2009;17:1788–1798. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aikawa R, Komuro I, Yamazaki T, Zou Y, Kudoh S, Tanaka M, et al. Oxidative stress activates extracellular signal-regulated kinases through Src and Ras in cultured cardiac myocytes of neonatal rats. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1813–1821. doi: 10.1172/JCI119709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen LB, Ginty DD, Weber MJ., and, Greenberg ME. Membrane depolarization and calcium influx stimulate MEK and MAP kinase via activation of Ras. Neuron. 1994;12:1207–1221. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90438-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]