Abstract

The Childhood Adaptation Model to Chronic Illness: Diabetes Mellitus was developed to identify factors that influence childhood adaptation to type 1 diabetes (T1D). Since this model was proposed, considerable research has been completed. The purpose of this paper is to update the model on childhood adaptation to T1D using research conducted since the original model was proposed. The framework suggests that individual and family characteristics, such as age, socioeconomic status, and in children with T1D, treatment modality (pump vs. injections), psychosocial responses (depressive symptoms and anxiety), and individual and family responses (self-management, coping, self-efficacy, family functioning, social competence) influence the level of adaptation. Adaptation has both physiologic (metabolic control) and psychosocial (QOL) components. This revised model provides greater specificity to the factors that influence adaptation to chronic illness in children. Research and clinical implications are discussed.

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is the most common and severe metabolic disorder of childhood and has the potential for long term life-threatening sequelae including cardiovascular disease, retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and premature death.1 Between 1990 and 1999, the prevalence increased from 0.1 per 100,000/year to 40.9 per 100,000/year among 112 centers worldwide.2 In the United States, 0.22% of individuals younger than 20 years of age, or about 176,500 children, have the condition.3, 4 Over the past 20 years, clear evidence has shown that the incidence has increased steadily among children and adolescents worldwide, with 2.8% (95% CI 2.4–3.2%) as the average annual increase in incidence.2, 5 The treatment regimen for T1D is both complex and demanding for children with T1D and their families. Following treatment recommendations requires that youth and their families expend considerable time, energy, and effort daily.3

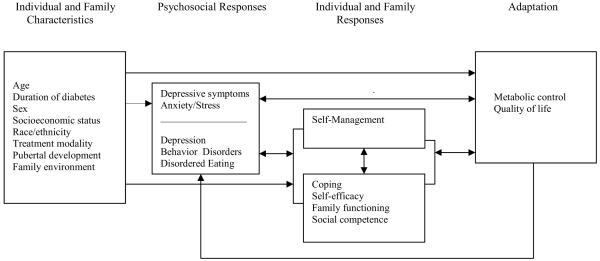

The Childhood Adaptation Model to Chronic Illness: Diabetes Mellitus6 was developed to identify factors that influence childhood adaptation to T1D (Figure 1). The model was derived from Roy’s Model of Adaptation,7 Pollock’s Adaptation to Chronic Illness Model,8 and research on childhood adaptation to T1D.9 In this framework, adaptation to chronic illness is viewed as a complex process involving internal and external factors that influence the initial response and level of adaptation. Adaptation is defined as the degree to which an individual responds both physiologically and psychosocially, to the stress of living with a chronic illness. In the original model, three elements were proposed to contribute to adaptation to chronic illness: (1) residual stimuli, which include age, sex, socioeconomic status (SES), developmental stage and time since diagnosis; (2) psychological responses such as anxiety and depressive symptoms; and (3) contextual stimuli, which include self-care, stressful events, and coping. These elements are proposed to interact and influence physiological and psychosocial adaptation to T1D.

Figure 1.

Original Model

Since this model was proposed in 1991, the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), a landmark clinical trial, demonstrated that in adolescents over 13 years, intensive management and improved metabolic control can reduce complications by 27% to 76%.10 Consequently, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) now recommends intensive management for all children and adolescents to achieve as close to normoglycemia as possible while avoiding severe hypoglycemia (HbA1c in school age children < 8% and HbA1c < 7.5% in adolescents age 13-19).3 Such treatment consists of delivery of insulin through continuous subcutaneous infusion (pump therapy) or multiple injections per day. In addition, youth are expected to conduct frequent blood glucose monitoring (at least four/day) and track carbohydrate intake and physical activity to make insulin dosing decisions.3 These changes in treatment recommendations have implications for childhood adaptation to T1D, and it is important that the model reflect recent research and current treatment practices.

In addition, since the model was proposed, considerable research has been undertaken on childhood adaptation to T1D, revealing new evidence on factors that may influence adaptation, such as family environment and psychological responses (e.g., depressive symptoms). Further, there is greater understanding of factors mediating adaptation, such as the relationship of self-management, coping, family functioning, and self-efficacy to improved metabolic control and quality of life. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to update the model on childhood adaptation to T1D using research conducted since the original model was proposed and to discuss research and clinical implications of the updated model.

Revised Model

Our research team has used The Childhood Adaptation Model to Chronic Illness: Diabetes Mellitus to guide a series of studies on the efficacy of a coping skills training (CST) program to improve physiological and psychosocial adaptation in adolescents,11 school-aged children,12 and parents of youth with T1D.13 Over the years, we have updated the model to include current research in order to further our understanding of childhood adaptation to T1D (Figure 2). Additional variables that are relevant to the adaptation process have been added to each element of the model to increase specificity and will be discussed in more detail. A summary of the model changes are identified in Table 1.

Figure 2. Conceptual Framework.

Table 1.

Summary of Model Changes

| Conceptual Change | Model Change |

|---|---|

| Terminology was modified to improve clarity. |

Residual stimuli changed to individual and family characteristics. Contextual stimuli changed to individual and family responses. Self-care changed to self-management. |

| Additional variables were added to the model to increase specificity of factors influencing adaptation. |

Treatment modality and family environment added to individual and family characteristics. Stress added to psychosocial responses. Severity of psychosocial responses differentiated. Self-efficacy, family functioning, and social competence added to individual and family responses. Self-management separated from other individual and family responses. Quality of life added as an adaptation outcome. |

| More recursive pathways in the model were defined and additional pathways are proposed. |

Psychosocial responses influences and is influenced by individual and family responses. Self-management influences and is influenced by coping, self-efficacy, family functioning, and social competence. Individual and family responses influence and are influenced by adaptation. Adaptation influences psychosocial responses. |

Individual and Family Characteristics

It is well established that age, duration of illness, sex, socioeconomic status (SES), and developmental status influence childhood adaptation to T1D. For example, each developmental stage presents unique diabetes self-management issues and psychosocial responses. Adolescence is a particularly challenging phase, as the physiologic changes of puberty and the developmentally appropriate need for autonomy can negatively influence self-management and metabolic control.14, 15 Duration of illness also has implications for childhood adaptation to T1D; research supports an association between longer duration and increased depressive symptoms.16, 17

Race/ethnicity may also influence adaptation to T1D. Studies suggest that minority youth are at greater risk for poor metabolic control than white youth,18 but the mechanism of risk is not well understood. There is some evidence that these differences are accounted for by the effects of SES and family structure (i.e., single vs. two-parent household).19, 20 For example, youth from traditional families have been reported to have better metabolic control compared to youth in non-traditional families (single and step families).21 It is likely that cultural differences in parenting also contribute to racial/ethnic differences in self-management and metabolic control. Hispanic culture, for example, is more likely to emphasize the needs of the family than American culture, which promotes the development of autonomy during adolescence.22 In line with this, Hispanic youth were found to be less independent in managing their care than white non-Hispanic youth.23 Another study found that parents of minority youth (primarily African American) were significantly lower in monitoring adolescents’ diabetes management than parents of white youth.24 Thus, there is a need to better understand how race/ethnicity influences family functioning of adolescents with T1D.

Since 1991, the availability of new technology, such as insulin pumps, smaller portable glucose monitors, and continuing glucose monitoring has changed diabetes management. Thus, treatment type (i.e., insulin pump vs. injections) may moderate adaptation. New technology also has the potential to influence childhood adaptation to T1D; more children and adolescents are using insulin pump therapy as a treatment modality, including very young children. Research demonstrates that pump therapy can be safe and effective with improved metabolic control and less severe hypoglycemia in children using pumps compared to children intensively managing diabetes with multiple daily injections.25, 26 Self-management is also different; depending on treatment modality as pump therapy requires less injections and offers increased flexibility in the timing of eating and physical activity. Recent studies suggest that pump therapy may have beneficial effects on quality of life as well.27, 28

Psychosocial Responses

Depressive Symptoms and Anxiety

The diagnosis of a chronic illness in childhood is a stressful event for youth and families and is likely to produce symptoms of anxiety and depression. Indeed, some studies suggest that the diagnosis and treatment of T1D is a traumatic event for parents, with significant symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder occurring in 22% of mothers and 16% of fathers 6 weeks after diagnosis.29 Such symptoms, particularly avoidance (e.g., avoiding things that remind one of the stressful event) may interfere with a child and family’s ability to adapt to the diagnosis and integrate its management into their lives. Research indicates that the number of depressive symptoms may be higher in the first few years after diagnosis, lower 4-9 years post-diagnosis, and rise again after 10 years.30 Thus, after an initial period of stress and distress, levels of depressive symptoms in children with T1D may not be significantly different from youth without a chronic illness;31 however, longer duration of T1D may increase the risk for depression and psychosocial problems.16, 17

Research supports that diabetes is a risk factor for developing psychological problems in youth with T1D, with rates up to 3 times as high as those without diabetes in a Nordic population.32 One of the few longitudinal studies to follow youth with T1D into young adulthood found that 42% developed at least one episode of psychiatric disorder, with the most common being depressive disorders (26%), followed by anxiety disorders (20%), and behavior disorders (16%).16

Depression is the most common psychological disorder in adolescents with T1D; a recent multi-center study of youth age 10-21 with diabetes (the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study) reported that 14% of youth were mildly depressed and 8.6% were moderately/severely depressed.33 Depression in adolescents with diabetes is more common in girls, in older adolescents, and in non-white, non-Hispanic youth.33 It also has important psychosocial and physiological consequences, including longer episodes of depression and higher levels of suicidal thoughts.34, 35 Depressive symptoms have also been shown to predict increased risk for retinopathy, increased risk for hospitalization, and poorer metabolic control in adults.33, 36-39

Eating disorders and eating disordered behavior are also of concern, particularly in adolescent girls with T1D. Rates of eating disorders among adolescents with T1D are estimated at 10% -- a rate twice as high as in girls without diabetes -- and evidence supports that the prevalence of eating disorders increase into young adulthood.40 Perhaps the eating disordered behavior of greatest concern is intentional insulin restriction, which results in hyperglycemia and weight loss. This behavior is fairly common and may occur in those who do not meet criteria for an eating disorder; it has been reported by 31-36% of women with T1D.40, 41 In addition, the attention to carbohydrates and control over eating required by the treatment regimen may predispose youth to the kind of rigid thinking about food that characterizes anorexia nervosa.42 Eating disorders, as well as sub-clinical eating disordered behaviors, have important clinical implications for adolescents with T1D, including poor metabolic control,37 recurrent hospitalizations, microvascular complications (e.g., retinopathy), and a higher mortality rate.40

To summarize, increased depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress are often consequences of living with T1D. Coping skills, self-efficacy, family functioning, social competence, and self-management may positively influence these psychosocial responses and adaptation. However, psychological problems, such as depression, behavior disorders, and eating disordered behavior, have been recognized as potential negative responses over time. Thus, the model distinguishes between less severe psychosocial responses (stress, increased depressive symptoms) and psychosocial responses, symptoms, and behaviors that indicate a psychological disorder. Over time, ineffective coping, poor family functioning, lack of social competence, particularly during adolescence and/or longer duration of T1D can increase the risk for the development of depression. Ineffective coping and female gender can increase the risk for the development of eating disorders.

Individual and Family Responses

Since the development of the original model, several factors have been identified as potential mediators of the stress of living with the illness and child and family adaptation. These factors include family functioning, coping and self-efficacy, and self-management. Each is described in more detail below.

Family functioning

Family functioning is widely acknowledged to be an important factor in childhood adaptation to diabetes, accounting for 34% of the variance in metabolic control (as compared to only 10% for adherence). For adolescents in particular, family conflict over diabetes management, such as negative and critical parenting, has been related to poorer metabolic control.21, 43 In addition, diabetes-specific family conflict is related to poorer quality of life in youth, having a stronger negative impact on quality of life than the intensity of treatment.44

In contrast, adolescents’ perceptions of parental acceptance have been related to better self-management and metabolic control.45 A review of the literature on family functioning in youth with diabetes indicated that better family functioning and more diabetes-specific support was related to better child psychosocial outcomes in adolescents.21 Research also indicates that greater parental involvement in adolescent diabetes management is associated with better metabolic control, and that shared responsibility for diabetes management tasks is associated with better psychological adjustment and self-management in adolescents.14, 46 The current ADA standards of care recommend a gradual transition toward independence in management during middle school and high school, while emphasizing that adult supervision remains important throughout the transition.47

Self-Efficacy and Coping

Self-efficacy and coping have been associated with improved self-management, family functioning, psychosocial adjustment, and metabolic control in children and adolescents.48-51 Self-efficacy, an important aspect of Social Cognitive Theory, is the belief that one can carry out specific behaviors under specified circumstances.52 Acquisition of health behaviors, particularly the complex health behaviors necessary in diabetes self-management, requires strong self-efficacy beliefs.53 Research supports that higher self-efficacy is related to better self-management and metabolic control in youth with T1D,51, 53 and increased parental and professional involvement may be needed for youth with low self-efficacy to improve diabetes self-management.53

The literature on coping has shown that the ways in which children and adolescents cope with stress are important mediators of the emotional and behavioral outcomes of stressful situations, such as living with T1D.54 In adolescents, greater use of avoidant (or disengagement) coping strategies has been related to poorer self-management, social competence, metabolic control, and quality of life.48, 55-58 Thus, how adolescents cope with the stress of a chronic condition has an important impact on their adaptation to the illness.

As previously mentioned, our research team has conducted a series of studies using CST for children and adolescents with diabetes. CST is based on Bandura’s self-efficacy theory,52 such that improving adolescents’ coping skills (including social problem solving, conflict resolution, stress management, and assertive communication) will increase their perceptions of self-efficacy, thereby improving adaptation. CST improved metabolic control, self-efficacy, and quality of life in adolescents (age 12-20) with T1D.11 In subsequent studies comparing CST to group-based education with parents and school-aged children with T1D, no significant effect of CST was demonstrated with respect to metabolic control, psychosocial outcomes, or quality of life.12 However, parents and school-aged children in both groups demonstrated significant improvements in self-efficacy, coping, and quality of life over one year, suggesting the potential benefit of group-based interventions in these populations.12, 13

Social competence

Development of relationships with peers can be complicated for youth with T1D, particularly adolescents. While diabetes is increasingly prevalent, an adolescent is often the only student in his/her school with T1D.59 Adolescents face internal stress when considering whether to share information about their diabetes to their friends. Needing to be the same as one’s peers and not be treated differently is characteristic of early adolescence. There is a strong fear of non-acceptance by the peer group and exclusion from peer activities, which may make an adolescent reluctant to disclose his or her diagnosis.60 This fear often causes adolescents to deliberately skip blood glucose monitoring, insulin injections or boluses as well as to eat additional foods without taking the appropriate insulin, all of which can lead to poorer metabolic control.59

While research supports that friends provide valuable emotional support to adolescents with T1D,61 many adolescents express apprehension about friend reactions to their diabetes self-management tasks.62, 63 Social competence has been identified as an area of particular vulnerability for adolescents with a chronic illness and may interfere with their ability to develop close peer relationships.64 In adolescents, social competence has been associated with better emotional well-being, better ability to manage stress, and better metabolic control.61, 65, 66

Self-management

Self-management is an active and flexible process whereby youth and their parents share responsibility and decision-making to achieve metabolic control, health, and well-being through a range of illness-related activities.67 Current standards of diabetes management require significant effort on the part of the youth and the family to achieve treatment goals. Research on the relationship between self-management and metabolic control is complex; while most studies have shown that better self-management behaviors were related to better metabolic control,68-70other studies have reported no significant association.71-73 Longer disease duration, physiologic factors, and developmental status may obscure this relationship. Child age, race/ethnicity, and SES may also influence self-management and metabolic control. In addition, treatment modality influences self-management. For example, pump therapy allows for greater flexibility in meal timing due to the ability to modify insulin administration precisely and frequently. While further research is indicated, gaining expertise in the self-management tasks and skills of T1D are an important aspect of adapting to T1D.

The use of complex self-management behaviors necessary to achieve treatment goals in youth may contribute to lower quality of life. Grey and colleagues suggested that it is difficult for youths with T1D to carry out intensive treatment regimens, advocating for more psychosocial interventions for youth with T1D to improve quality of life.74 In contrast, some evidence suggests that such treatment does not necessarily impair quality of life in children and adolescents because these regimens allow for greater flexibility than older, conventional regimens.75-77 For example, better quality of life was correlated with some diabetes self-management behaviors, such as dietary restrictions, the number of insulin injections a day, and the use of pump therapy, indicating that youth with T1D who have good diabetes self-management could also perceive a good quality of life.28, 76

Research also supports a relationship between depression and diabetes self-management in youth.39, 78 In fact, Kyngas reported that depressive symptoms were the most powerful predictor of diabetes self-management in adolescents with T1D.68 Depression is accompanied by decreasing energy, which may in turn decrease motivation to perform complex self-management tasks.79, 80 In addition, poor self-management may also contribute to youth feeling discouraged and depressed.

Adaptation

Metabolic control is the primary marker of physiological adaptation to T1D because it has been shown clearly to delay and/or prevent the development of long-term diabetes complications.81 Maintaining glucose metabolism at close to normal levels is now the standard of care. This revised model provides greater specificity on the factors that influence metabolic control and quality of life.

Quality of life is increasingly being recognized as an important psychosocial outcome in youth, a qualitatively different but important outcome along with metabolic control. In general, youth perceive their quality of life to be good, reporting high satisfaction with life and showing no significant difference from their peers without a chronic health condition.44, 82, 83 Conflicts around diabetes management have been shown to negatively affect children’s quality of life more than the intensity of treatment.44, 82 Better quality of life in children is associated with fewer depressive symptoms, better coping, and warmer and more caring family behaviors.

Research on the relationship between quality of life and metabolic control is conflicting. Some research has indicated no significant association,82, 84 while other research has demonstrated that better metabolic control is associated with better quality of life,85, 86 and deteriorating metabolic control is associated with poorer quality of life.87 Sample size, child age, and gender may influence this relationship. Girls have been reported to have more worries, greater impact of diabetes, and less life satisfaction than boys.82, 85 Quality of life has been reported to decline in mid-adolescence and return to baseline in young adulthood.88

More recently, parental adaptation has been reported to influence quality of life, in that children whose parents report fewer depressive symptoms report better quality of life.83, 89 In addition, children who perceive that their parents provide positive emotional support and communication report better quality of life.84

Thus, optimal adaptation in childhood includes metabolic control within standards of care for age and positive quality of life. Interventions that optimize metabolic control and quality of life are advocated in the care and treatment of children with T1D.84, 85

Discussion

Stress-adaptation models provide a framework for the study of interventions to promote adaptation to chronic illness and posit that adaptation may be viewed as an active process whereby the individual adjusts to the environment and the challenges of a chronic illness.6, 8, 74 In this paper, a revised model of adaptation to T1D is proposed. In this revised framework, adaptation is the degree to which an individual responds both physiologically and psychosocially to the stress of living with a long-term illness. The framework suggests that individual and family characteristics, such as age, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and treatment modality (pump vs. injections), psychosocial responses (depressive symptoms and anxiety), and individual and family responses (self-management, coping, self-efficacy, family functioning, social competence) influence adaptation. In this model, adaptation has both physiologic (metabolic control) and psychosocial (QOL) components (Figure 2).

T1D is a chronic condition; thus, the impact of the condition will unfold over time and persist for life. For youth, not only does the impact of the illness (in terms of the symptoms), course, and treatment change over time, but developmental expectations also change over time. In addition, T1D in childhood has considerable implications for families. The Childhood Adaptation to T1D Model represents a recursive model, in that changes in different elements of adaptation to illness will have the potential to impact the adaptive process and the individual level of adaptation. One limitation to the model is that most research on youth with T1D is conducted in the United States and some factors or specified relationships in the model may be manifested differently in other cultures. In addition, adaptation to chronic illness in childhood is complex and additional factors not yet delineated may also influence this process. Despite these limitations, the model suggests important research and clinical implications.

Research Implications

Research over the past decade has provided data to support the relationships proposed in the original model as well as to identify additional factors that influence childhood adaptation to T1D. Continued research evaluating the relationships proposed in the model and how they vary based on proposed moderating and mediating factors is indicated. In addition, there is the need for more longitudinal research on childhood adaptation. Prospective longitudinal investigations of adolescents with chronic illnesses may be particularly informative when change is examined during critical development periods or transition points, such as early adolescence (11-15 years) and mid-adolescence (15-17 years).90 Moreover, many of the relationships between factors are likely to be bi-directional, and longitudinal research is needed to understand how these factors may influence each other over time.90

In addition to the need for more longitudinal studies, our model suggests that intervention research needs to move beyond evaluation of simple efficacy, but that studies must be designed to evaluate both moderators and mediators of outcomes.91 In other words, it is important that studies have large enough samples, careful attention to measurement over time, and explicit consideration of the mediators of interventions outcomes. We are using the new model to evaluate such factors in a multi-site study of an internet version of the CST program.92

Considerable research on the influence of the family to childhood adaptation to T1D has been undertaken since the publication of the original model. Family-based psychosocial interventions are being evaluated with promising outcomes.93 In addition, research has begun to focus on parent adaptation to having a child with T1D and the subsequent impact on child adaptation.89, 94 Further research on parent adaptation and family functioning is indicated. Since youth with T1D are at increased risk for depression, research is also needed on interventions to prevent and treat depression across developmental stages.95 Lastly, most studies on adaptation in youth were conducted in the United States; therefore, research on the patterns of adaptation in different cultures and races is indicated.

Clinical Implications

The multitude of factors that influence childhood adaptation to T1D suggest the need for comprehensive ongoing assessment and multidisciplinary care, particularly at developmental transitions. Guidelines for developmentally appropriate clinical care for children with T1D have been proposed.96 Clearly, the transition from childhood to adolescence poses considerable child and family challenges, and there is a need for healthcare providers to evaluate individual and family functioning during this transition. Psychosocial assessment, particularly for depression in both youth with T1D and their parents, is indicated to promote childhood adaptation.94 In addition, research suggests that most families would benefit from a discussion on the optimal transfer of responsibility for diabetes self-management. By keeping in mind risk factors (Table 2), providers can focus such screening efforts and offer supportive services. Potential clinical interventions are summarized in Table 3.

Table 2.

Risk Factors for Poor Adaptation to T1D

| Risk Factor |

|---|

| Developmental stage of adolescence (particularly age 14-16) |

| Duration > 2 years |

| Low socioeconomic status |

| Nontradtional family |

| Black or Hispanic race/ethnicity |

| Female gender for eating disorders, depression |

Table 3.

Interventions to Promote Childhood Adaptation to T1D

| Interventions |

|---|

| Promote positive coping strategies of social problem solving, conflict resolution |

| Support collaborative child and family self-management |

| Promote age-appropriate responsibility for self-management |

| Provide opportunity for child to gain self-efficacy in self-management |

| Promote positive family functioning (family cohesison, warm and caring diabetes support, conflict resolution skills) |

| Stress management for child and parent as indicated |

| Screen for maternal and child depression |

Conclusion

This revised model of childhood adaptation to chronic illness is complex, and it is unlikely that a single study could test all of the relationships. This revised model, however, is intended to guide researchers and health care providers in their thinking about adaptation to chronic illness in children, especially youth with T1D. In this paper, we have considered the recent research on individual and family factors that influence adaptation in youth with T1D, as well as the clinical changes in treatment, to provide a more comprehensive, updated model. Considering the significant challenges to youth and their families, there is a great need to develop innovative interventions that are developmentally appropriate and address the complex physiologic, psychosocial, and family processes that influence adaptation to T1D.

Acknowledgement

National Institute of Nursing Research R01NR0094009

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Robin Whittemore, Yale University School of Nursing, 100 Church Street South, New Haven, CT 06536-0740, Phone: 203-737-2351, Fax: 203-737-4480, robin.whittemore@yale.edu.

Sarah Jaser, Yale University School of Nursing, New Haven, CT.

Jia Guo, Central South University, School of Nursing, Changsha, China.

Margaret Grey, Yale University School of Nursing, New Haven, CT.

References

- 1.Complications of diabetes. 2009 [cited March 13, 2009]; Available from: http://www.diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/complications/index.htm.

- 2.Karvonen M. Incidence and trends of childhood type 1 diabetes worldwide 1990-1999. Diabet Med. 2006;23:857–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ADA Standards of medical care in diabetes - 2009. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:S13–S61. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liese AD. The burden of diabetes mellitus among US youth: Prevalence estimates from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1510–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li XH, Li TL, Yang Z, Liu ZY, Wei YD, Jin SX. A nine-year prospective study on the incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes mellitus in China. Biomed Environ Sci. 2000;13:263–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grey M, Thurber FW. Adaptation to chronic illness in childhood: Diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr Nurs. 1991;6:302–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roy C. Introduction to nursing: An adaptation model. Englewood Cliffs, NJ; Prentice-Hall: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollock SE. Human responses to chronic illness: Physiologic and psychosocial adaptation. Nurs Res. 1986;35:90–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grey M, Cameron ME, Thurber FW. Coping and adaptation in children with diabetes. Nurs Res. 1991;40:144–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DCCT Research Group Effect of intensive insulin treatment on the development and progression of long-term complications in adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. J Pediatr. 1994;125:177–88. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grey M, Boland EA, Davidson M, Li J, Tamborlane WV. Coping skills training for youth with diabetes mellitus has long-lasting effects on metabolic control and quality of life. J Pediatr. 2000;137:107–13. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.106568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grey M, Whittemore R, Jaser SS, Ambrosino J, Lindemann E, Liberti L, et al. Effects of coping skills training in school-age children with type 1 diabetes. Res Nurs Health. 2009;32:405–18. doi: 10.1002/nur.20336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grey M, Jaser SS, Whittemore R, Jeon S, Lindemann E. Coping Skills Training for Parents of Children with Type 1 Diabetes: 12 Month Outcomes. J Pediatr Nurs. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182159c8f. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson BJ, Vangsness L, Connell A, Butler D, Goebel-Fabbri A, Laffel LMB. Family conflict, adherence, and glycaemic control in youth with short duration Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2002;19:635–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hocking MC, Lochman JE. Applying the transactional stress and coping model to sickle cell disorder and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: Identifying psychosocial variables related to adjustment and intervention. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2005;8:221–46. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-6667-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovacs M, Goldston D, Obrosky DS, Bonar LK. Psychiatric disorders in youth with IDDM: Rates and risk factors. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:36–44. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whittemore R, Kanner S, Singleton S, Hamrin V, Chiu J, Grey M. Correlates of depressive symptoms in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2002;3:135–43. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5448.2002.30303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delamater AM, Shaw KH, Applegate EB, Pratt IA, Eidson M, Lancelotta GX, et al. Risk for metabolic control problems in minority youth with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(5):700–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.5.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Auslander WF, Thompson S, Dreitzer D, White NH, Santiago JV. Disparity in glycemic control and adherence between African-American and Caucasian youths with diabetes: Family and community contexts. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(10):1569–75. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.10.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swift EE, Chen R, Hershberger A, Holmes CS. Demographic risk factors, mediators, and moderators in youths’ diabetes metabolic control. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32(1):39–49. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3201_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whittemore R, Kanner S, Grey M. The influence of family on physiological and psychosocial health in youth with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. In: Melnyk B, Fineat-Overholt E, editors. Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2004. pp. CD22-73–CD22-87. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lugo Steidel A, Contreras JM. A new familism scale for use with Latino populations. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2003;25:312–30. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallegos-Macias AR, Macias SR, Kaufman E, Skipper B, Kalishman N. Relationship between glycemic control, ethnicity and socioeconomic status in hispanic and white non-hispanic youths with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Diabetes. 2003;4(1):19–23. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5448.2003.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellis DA, Templin TN, Podolski C-L, Frey MA, Naar-King S, Moltz K. The Parental Monitoring of Diabetes Care Scale: Development, Reliability and Validity of a Scale to Evaluate Parental Supervision of Adolescent Illness Management. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(2):146–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boland EA, Grey M, Oesterle A, Fredrickson L, Tamborlane WV. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion: A new way to lower risk of severe hypoglycemia, improve metabolic control, and enhance coping in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1779–84. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.11.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinzimer SA, Ahern JH, Doyle EA, Vincent MR, Dziura J, Steffen AT, et al. Persistence of benefits of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion in very young children with type 1 diabetes: A follow-up report. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1601–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMahon SK, Airey FL, Marangou DA, McElwee KJ, Carne CL, Clarey AJ, et al. Insulin pump therapy in children and adolescents: Improvements in key parameters of diabetes management including quality of life. Diabet Med. 2005;22:92–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mednick L, Cogen FR, Streisand R. Satisfaction and quality of life in children with type 1 diabetes and their parents following transition to insulin pump therapy. Children’s Health Care. 2004;33:169–83. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landolt MA, Vollrath M, Laimbacher J, Gnehn HE, Sennhauser FH. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder in parents of children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:682–9. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000161645.98022.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grey M, Whittemore R, Tambolane WV. Depression in type 1 diabetes in children: natural history and correlates. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:907–11. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobson AM, Hauser ST, Willett JB, Wolfsdorf JI, Dvorak R, Herman L, et al. Psychological adjustment to IDDM: 10-year follow-up of an onset cohort of child and adolescent patients. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:811–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.5.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kokkonen J, Kokkonen E-R. Mental health and social adaptation in young adults with juvenile-onset diabetes. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;49:175–81. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawrence JM, Standiford DA, Loots B, Klingensmith GJ, Williams DE, Ruggiero A, et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Depressed Mood Among Youth With Diabetes: The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Pediatrics. 2006 April 1;117(4):1348–58. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1398. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldston DBP, Kelley AEMD, Reboussin DMP, Daniel SSP, Smith JAP, Schwartz RPMD, et al. Suicidal Ideation and Behavior and Noncompliance With the Medical Regimen Among Diabetic Adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1528–36. doi: 10.1016/S0890-8567(09)66561-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kovacs M, Obrosky DS, Goldston D, Drash A. Major depressive disorder in youths with IDDM: A controlled prospective study of course and outcome. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:45–51. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garrison MM, Katon WJ, Richardson LP. The impact of psychiatric comorbidities on readmissions for diabetes in youth. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2150–4. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hegelson VS, Siminerio L, Escobar O, Becker D. Predictors of metabolic control among adolescents with diabetes: A 4-year longitudinal study. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:254–70. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kovacs M, Mukerji P, Drash A, Iyengar S. Biomedical and psychiatric risk factors for retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1592–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.12.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stewart SM, Rao U, Emslie GJ, Klein D, White PC. Depressive symptoms predict hospitalization for adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1315–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peveler RC, Bryden KS, Neil HAW, Fairburn CG, Mayou RA, Dunger DB, et al. The relationship of disordered eating habits and attitudes to clinical outcomes in young adult females with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:84–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ. Insulin omission in women with IDDM. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:1178–85. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.10.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goebel-Fabbri AE. Disturbed eating behaviors in type 1 diabetes: Clinical significance and recommendations. Curr Diab Rep. 2009;9:133–9. doi: 10.1007/s11892-009-0023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewin AB, Heidgerken AD, Geffken GR, Williams LB, Storch EA, Gelfand KM, et al. The relation between family factors and metabolic control: The role of diabetes adherence. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31:174–83. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laffel LM, Connell A, Vangness L, Goebel-Fabbri A, Mansfield A, Anderson BJ. General quality of life in youth with Type 1 Diabetes: Relationship to patient management and diabetes-specific family conflict. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3067–73. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.11.3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berg CA, Butler JM, Osborn P, King G, Palmer DL, Butner J, et al. Role of parental monitoring in understanding the benefits of parental acceptance on adolescent adherence and metabolic control of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:678–83. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palmer DL, Berg CA, Wiebe DJ, Beveridge RM, Korbel C, Upchurch R. The role of autonomy and pubertal status in understanding age differences in maternal involvement in diabetes responsibility across adolescence. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29:35–46. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silverstein JH, Klingensmith G, Copeland K, Plotnick L, Kaufman F, Laffel LMB, et al. Care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:184–212. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Graue M, Wentzel-Larsen T, Bru E, Hanestad BR, Sovik O. The coping styles of adolescents with type 1 diabetes are associated with degree of metabolic control. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1313–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grey M, Lipman T, Cameron ME, Thurber FW. Coping Behaviors at Diagnosis and in Adjustment One Year Later in Children with Diabetes. Nurs Res. 1997;46:312–7. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199711000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Griva K, Myers LB, Newman S. Illness perceptions and self efficacy beliefs in adolescents and young adults with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Psychology and Health. 2000;15:733–50. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ott J, Greening L, Palardy N, Holderby A, DeBell WK. Self-efficacy as a mediator variable for adolescents’ adherence to treatment for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Children’s Health Care. 2000;29:47–63. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iannotti RJ, Schneider S, Nansel TR, Haynie DL, Plotnick LP, Clark LM, et al. Self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and diabetes self-management in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27:98–105. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200604000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Progress, problems, and potential in theory and research. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:87–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Delamater AM, Kurtz SM, Bubb J, White NH, Santiago JV. Stress and coping in relation to metabolic control of adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1987;8:136–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hanson CL, Cigrang JA, Harris MA, Carle DL, Relyea G, Burghen GA. Coping styles in youth with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:644–51. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.5.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jacobson AM, Hauser ST, Lavori P, Wofsdorf JI, Herskowitz RD, Milley JE, et al. Adherence among children with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus over a four-year longitudinal follow-up: I. The influence of patient coping and adjustment. J Pediatr Psychol. 1990;15:511–26. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/15.4.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reid GJ, Dubow EF, Carey TC, Dura JR. Contribution of coping to medical adjustment and treatment responsibility among children and adolescents wtih diabetes. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1994;15:327–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Davidson M, Penney EA, Muller B, Grey M. Stressors and self-care challenges faced by adolescents living with type 1 diabetes. App Nurs Res. 2004;17:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Syzdlo D, Van Wattum PJ, Woolson J. Psychological aspects of diabetes mellitus. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2003;12:439–58. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(03)00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.La Greca AM, Auslander WF, Greco P, Spetter D, Fisher EB, Santiago JV. I get by with a little help from my family and friends: Adolescents’ support for diabetes care. J Pediatr Psychol. 1995;20:449–76. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/20.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buchbinder MH, Detzer MJ, Welsch RL, Christiano AS, Patashnick JL, Rich M. Assessing adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: A multiple perspective pilot study using visual illness narratives and interviews. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36(1):71.e9–.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hains AA, Berlin KS, Davies WH, Parton EA, Alemzadeh R. Attributions of adolescents with type 1 diabetes in social situations. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:818–22. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.04.06.dc05-1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.La Greca AM. Peer influences in pediatric chronic illness: An update. J Pediatr Psychol. 1992;17:775–84. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/17.6.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Edgar KA, Skinner TC. Illness representations and coping as predictors of emotional well-being in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003;28:485–93. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hanson CL, Henggeler SW, Burghen GA. Social competence and parental support as mediators of the link between stress and metabolic control in adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55:529–33. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.55.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schilling LS, Grey M, Knafl KA. The concept of self-management of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents: An evolutionary concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2002;37:87–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kyngas HA. Predictors of good adherence of adolescents with diabetes (insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus) Chronic llln. 2007;3:20–8. doi: 10.1177/1742395307079191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Levine BS, Anderson BJ, Butler DA, Antisdel JE, Brackett J, Laffel LMB. Predictors of glycemic control and short-term adverse outcomes in youth with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr. 2001;139:197–203. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.116283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schilling LS, Dixon JK, Knafl KA, Lynn MR, Murphy K, Dumser S, et al. A new self-report measure of self-management of type 1 diabetes for adolescents. Nurs Res. 2009;58:228–36. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181ac142a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chang CW, Yeh CH, Lo FS, Shih YL. Adherence behaviours in Taiwanese children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:207–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dashiff CJ, McCaleb A, Cull V. Self-Care of Young Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes. J Pediatr Nurs. 2006;21:222–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Greening L, Stoppelbein L, Konishi C, Jordan SS, Moll G. Child routines and youths’ adherence to treatment for type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:437–47. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grey M, Davidson M, Boland EA, Tambolane WV. Clinical and psychosocial factors associated with achievement of treatment goals in adolescents with diabetes mellitus. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28:377–85. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ausili E, Tabacco F, Focarelli B, Padua L, Crea F, Caliandro P, et al. Multidimensional study on quality of life in children with type 1 diabetes. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2007;11:249–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen SL, Zhi DJ, Shen SX, Yu SZ. Study on factors associated with life quality of children with type 1 diabetes. China Public Heath. 2001;17:1077–88. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rubin RR, Peyrot M. Quality of life and diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 1999;15:205–18. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-7560(199905/06)15:3<205::aid-dmrr29>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang AH, Zhu C, Hong BS, Zhang JS. Influence of mood disturbance on metabolic control and compliance with treatment in type 1 diabetic children. J Appl Clin Pediatr. 2007;22:1081–2. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lin EHB, Katon W, Von Korff M, Rutter C, Simon GE, Oliver M, et al. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2154–60. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McKellar JD, Humphreys K, Piette JD. Depression increases diabetes symptoms by complicating patients’ self-care adherence. Diabetes Educ. 2004;30:485–92. doi: 10.1177/014572170403000320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.DCCT Research Group Influence of intensive diabetes treatment on quality of life outcomes in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:195–203. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Grey M, Boland EA, Yu C, Sullivan-Bolyai S, Tamborlane WV. Personal and family factors associated with quality of life in adolescents with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:909–14. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.6.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Whittemore R, Urban AD, Tamborlane WV, Grey M. Quality of life in school-age children with type 1 diabetes on intensive treatment and their parents. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29:847–54. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Faulkner MA. Quality of life for adolescents with type 1 diabetes: Parental and youth perspectives. Pediatr Nurs. 2007;29:362–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hoey H, Aanstoot HJ, Chiarelli F, Daneman D, Danne T, Dorchy H, et al. Good metabolic control is associated with better quality of life in 2, 101 adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1923–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.11.1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vanelli M, Chiarelli F, Chiari G, Tumini S. Relationship between metabolic control and quality of life in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: Report from two Italian centres for the management of diabetes in childhood. Acta Biomedica de l’Ateneo Parmense. 2003;74:13–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hassan K, Loar R, Anderson BJ, Heptulla RA. The role of socioeconomic status, depression, quality of life, and glycemic control in type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr. 2006;149:526–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Insabella G, Grey M, Knafl KA, Tambolane WV. The transition to young adulthood in youth with type 1 diabetes on intensive treatment. Pediatr Diabetes. 2007;8:228–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jaser SS, Whittemore R, Ambrosino J, Lindemann E, Grey M. Mediators of depressive symptoms in children with type 1 diabetes and their mothers. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:509–19. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Holmbeck GN, Bruno EF, Jandasek B. Longitudinal research in pediatric psychology: An introduction to the special issue. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31(10):995–1001. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kraemer HC, Wilson T, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):877–83. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Whittemore R, Grey M, Lindemann E, Ambrosino JM, Jaser SS. An internet CST Program for teens with type 1 diabetes. Computers, Informatics, and Nursing. 2010;28:103–11. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e3181cd8199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wysocki T, Harris MA, Buckloh LM, Mertlich D, Lochrie AS, Mauras N, et al. Randomized Trial of Behavioral Family Systems Therapy for Diabetes: Maintenance of effects on diabetes outcomes in adolescents. Diabetes Care. 2007 March 1;30(3):555–60. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1613. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cameron FJ, Northam EA, Ambler GR, Daneman D. Routine psychological screening in youth with type 1 diabetes and their parents: A notion whose time has come? Diabetes Care. 2007;30(10):2716–24. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hood KK, Huestis S, Maher A, Butler D, Volkening L, Laffel LMB. Depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: association with diabetes-specific characteristics. Diabetes Care. 2006 Jun 01;29(6):1389–91. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0087. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Grey M, Tambolane WV. Behavioral and family aspects of treatment of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. In: Porte D, Sherwin R, Baron AD, editors. Ellenberg and Rifkin’s diabetes mellitus. 6 ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2003. pp. 565–72. [Google Scholar]