Abstract

The autonomic nervous and respiratory systems, as well as their coupling, adapt over a wide range of conditions. Chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH) is a model for recurrent apneas and induces alterations in breathing and increases in sympathetic nerve activity which may ultimately result in hypertension if left untreated. These alterations are believed to be due to increases in the carotid body chemoreflex pathway. Here we present evidence that the nucleus tractus solitarii (nTS), the central brainstem termination site of chemoreceptor afferents, expresses a form of synaptic plasticity that increases overall nTS activity following intermittent hypoxia. Following CIH, an increase in presynaptic spontaneous neurotransmitter release occurs under baseline conditions. Furthermore, during and following afferent stimulation there is an augmentation of spontaneous transmitter release that occurs out of synchrony with sensory stimulation. On the other hand, afferent evoked synchronous transmitter release is attenuated. Overall, this shift from synchronous to asynchronous transmitter release enhances nTS cellular discharge. The role of the neurotransmitter dopamine in CIH-induced plasticity is also discussed. Dopamine attenuates synaptic transmission in nTS cells by blockade of N-type calcium channels, and this mechanism occurs tonically following normoxia and CIH. This dopaminergic pathway, however, is not altered in CIH. Taken together, alterations in nTS synaptic activity may play a role in the changes of chemoreflex function and cardiorespiratory activity in the CIH apnea model.

Keywords: chemoreflex, cardiovascular, baroreflex, respiration, synaptic transmission, action potential

1. Introduction

The cardiovascular and respiratory systems are vital in maintaining physiological homeostasis. Heart rate and blood pressure are maintained within normal limits by precise beat-to-beat control of the autonomic nervous system. Likewise, the respiratory system maintains typical arterial oxygen, carbon dioxide and pH within the body. These systems do not work in isolation but are coordinated through afferent and efferent pathways as well as central nuclei. These systems are also tightly coupled in that respiratory rhythms are observed in sympathetic nerve activity and changes in blood pressure influence respiration. The cardio-respiratory systems, and their coupling, exhibit an amazing degree of adaptation under physiological [e.g., exercise (Michelini and Stern, 2009), deconditioning (Hasser and Moffitt, 2001), pregnancy (Kvochina et al., 2007)] and pathophysiological [e.g., heart failure (Patel, 2000)] conditions.

Commonly observed is exposure to periods of low oxygen, either environmentally influenced or due to disease states. Decreases in arterial oxygen (hypoxia) are sensed by peripheral chemoreceptors in the carotid body located in the bifurcation of the common carotid artery. Hypoxia increases carotid body chemoreceptor sensory activity within the carotid sinus nerve, which joins the glossopharyngeal nerve, and this afferent activity is sent to the central nervous system (Mifflin, 1992; Vardhan et al., 1993). Ultimately, hypoxic episodes activate the carotid body chemoreflex and robustly increase breathing, sympathetic nerve activity and their coupling to maintain proper perfusion of the lungs, brain and kidney and to compensate for the direct vasodilating response of hypoxia. Several key central nuclei are important for integrating sensory information and increasing activity of the cardiovascular and respiratory system. One such area is the nucleus tractus solitarii (nTS), which is the first site for sensory termination in the brain (Andresen and Kunze, 1994), the focus of this short review.

2. Recurrent apneas induce alterations in the cardiorespiratory system

Epidemiologically, up to 24% of males and 9% of females from several racial and ethnic groups have mild hypoxic episodes from recurrent apneas throughout the night (Bradley and Floras, 2009). A prominent example is obstructive sleep apnea in which the upper airway periodically collapses (Bradley and Floras, 2009). With the occurrence of each apneic episode, there is an increase in arterial pressure and sympathetic nerve activity (Kato et al., 2009). The persistence of recurrent apneas induces daytime elevations in blood pressure and sympathetic nerve activity which eventually leads to hypertension. Clinical case studies suggest that the carotid body chemoreflex is one of the primary components of obstructive sleep apnea-induced alterations in the cardiovascular system (Narkiewicz et al., 1998; Narkiewicz et al., 1999b). Sleep apnea patients, even when studied without the influence of other confounding factors, exhibit increased chemoreflex sensitivity and hypertension (Spicuzza et al., 2006). Ventilatory depression caused by brief hyperoxia, a measure of peripheral chemosensitivity, is also more pronounced in sleep apnea patients (Tafil-Klawe et al., 1991). Last, apneic patients who have had their carotid bodies removed for unrelated purposes do not develop hypertension (Somers and Abboud, 1993). Untreated, recurrent apneas elevate the mortality rate. With the use of continuous airway positive pressure therapy, a successful reduction in nocturnal respiratory events, elevated sympathetic nerve activity and cardiovascular morbidity can occur (Narkiewicz et al., 1999a; Doherty et al., 2005; Spicuzza et al., 2006). Moreover, treatment is associated with a return to near normal of the elevated chemosensitivity (Spicuzza et al., 2006). In summary, sleep apnea is associated with an elevated chemoreflex.

3. Chronic intermittent hypoxia

Chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH) is a common rodent model for recurrent apneas. This model was designed to mimic hypoxic episodes during apneas by subjecting animals to brief periods of acute hypoxia interspersed with normal room air, or normoxia (Fletcher et al., 1992). The pattern of CIH exposure, however, varies widely among laboratories (Fletcher and Bao, 1996; Greenberg et al., 1999; Ling et al., 2001; Peng et al., 2003; Kline et al., 2007; de Paula et al., 2007; Almado et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2009). The time of each hypoxic episode occurs between ~30 seconds to a few minutes, with the hypoxic-normoxic cyclic periods ranging from hours to months. This is an important consideration because the pattern and duration of the hypoxic challenge can determine the final cardiorespiratory output (Prabhakar and Kline, 2002).

Similar to sleep apnea, during and following CIH exposure in animal models, cardiorespiratory reflexes are amplified compared to those observed during brief hypoxia; this is believed to be due to changes in the chemoreflex. For instance, after CIH exposure, the ventilatory response to hypoxia is augmented in the rat (Peng et al., 2004), mouse (Peng et al., 2006) and cat (Rey et al., 2004). The sympathoexcitatory response to peripheral chemoreflex activation is also increased after CIH in anesthetized (Braga et al., 2006) and conscious (Huang et al., 2009) rats. Furthermore, intermittent hypoxia also induces an increase in baseline arterial pressure of 10-30 mm Hg (Kumar et al., 2006; Zoccal et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2007). Last, sectioning of the carotid sinus nerve carrying chemoafferent fibers ablates CIH-induced hypertension (Fletcher et al., 1992). Thus, the chemoreflex plays a prominent role in the augmentation of hypoxic ventilatory response, sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in CIH, similar to individuals inflicted with sleep apnea.

In addition to the chemoreflex pathway, the baroreceptor reflex is also altered following CIH. While ten days of CIH increases the gain of the baroreflex (Zoccal et al., 2009a), longer exposures to CIH (1-3 months) significantly blunt the baroreflex in mice (Lin et al., 2007) and rats (Gu et al., 2007). This occurs despite an increase in aortic depressor nerve activity (Gu et al., 2007) which may result from structural changes of baroreceptor terminal fields in the aortic arch (Ai et al., 2009). In short, CIH can significantly alter sensory reflexes such as the chemo- and baroreflex. The site and mechanism of these alterations has received considerable attention.

4. The central nervous system contributes to CIH-induced alterations of sensory reflexes

The chemoreflex arc that is responsible for increases in breathing and sympathetic activity during hypoxia consists of afferent sensory axons, central brainstem and forebrain nuclei, and motor and autonomic efferent axons. The augmented reflexes seen in CIH animal models are due, in part, to enhanced chemosensory afferent discharge during hypoxia (Peng et al., 2003; Peng and Prabhakar, 2004). In addition, several studies suggest CIH induces alterations in the processing of sensory information within the central nervous system. Following seven days of CIH, an increase in the gain of the central component of chemoreceptor processing has been demonstrated (Ling et al., 2001). In those studies, carotid sinus nerve stimulation, which bypasses the carotid body and thereby avoids the potential influence of differences in afferent activity, was more effective in inducing phrenic nerve discharge in CIH-conditioned rats compared to normoxic rats. In contrast, CIH decreases the central component of the baroreflex. After 35 to 50 days of CIH, the reflex fall in heart rate and blood pressure due to directly stimulating the aortic depressor nerve was reduced when compared to their normoxic controls (Gu et al., 2007). The reduced baroreflex response in CIH to depressor nerve stimulation was not due to an attenuation in the activity of efferent pathways to the heart or blood vessels as direct stimulation of the vagus nerve resulted in a potentiated fall in heart rate and blood pressure (Gu et al., 2007). These studies would suggest a central component is involved in both the alterations of the chemo- and baroreflex.

The central site for reflex modifications in CIH may involve several cardiorespiratory nuclei. The induction of the immediate early gene protein Fos, a marker for neuronal activation, may lend some insight into the nuclei affected. CIH induces Fos expression in the raphé, intermediate reticular nuclear zone, and along the rostral to caudal ventral lateral medulla cell column (Greenberg et al., 1999). Another key region is the nTS where Fos was observed in the medial and commissural subregions of this nucleus.

5. Sensory afferent processing is altered in the nTS following CIH

The nucleus tractus solitarii is the first site of chemoreceptor and baroreceptor integration in the central nervous system (van Giersbergen et al., 1992; Andresen and Kunze, 1994). A loose viscerotopic organization of afferent integration has been suggested, with baroafferents primarily terminating in the medial subnucleus and chemoafferents terminating in the medial and commissural subnucleus (Finley and Katz, 1992; Andresen and Kunze, 1994). Chemo- and barosensory afferent axons enter the brainstem and travel along the sensory bundle of the solitary tract before exiting and forming synapses with cells in the nTS (Housley et al., 1987; Finley and Katz, 1992; Andresen and Kunze, 1994). In addition to second-order cells that directly receive afferent information, the nTS possesses a large number of interneurons, receives projections from many brain regions that influence cardiorespiratory control, and contains a multitude of neurotransmitters and neuromodulators (Andresen and Kunze, 1994). Thus, the nTS is well suited for cardiorespiratory integration.

The nTS receives baroreceptor and chemoreceptor afferent signals in a continuous manner and processes this incoming information to modulate the autonomic and respiratory systems. This central nucleus is crucial to the integration of afferent signals and is more than a simple relay station. This is evident in the many short- and long-term forms of synaptic and neuronal plasticity that have been observed in the nTS (Kline, 2008). Glutamate is the primary neurotransmitter of sensory afferents, yet other transmitter and modulators can also be released. The nTS sends reciprocal projections to several nuclei within the forebrain, brainstem and spinal cord. Prominent areas for innervation include the paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus, rostral and caudal ventrolateral medulla, and raphé, sites in which Fos expression is observed in CIH. It is the coordinated activity of the nTS with these other central nuclei that modulates the cardiorespiratory system during hypoxic stress.

As the first site of information processing for cardiorespiratory reflexes, it is not unexpected that the nTS is also the first site where such processing can be modulated by CIH (Kline, 2008). This notion was tested in brain tissue from CIH exposed animals. In these protocols, rats were exposed to normoxia (21% oxygen) or CIH (50 seconds of 6% oxygen, 5 minutes of 21% oxygen, 8 hours per day) for up to 30 days (Kline et al., 2007). To explore whether sensory afferent processing or neuronal activity is altered in the nTS by intermittent hypoxia, recordings were taken from caudal nTS cells in the in vitro brainstem preparation. In this preparation, the brainstem including the nTS is sliced in the horizontal plane thereby leaving intact the afferent pathway through the solitary tract (i.e., tractus solitarius, or TS). Such an in vitro preparation permits electrical stimulation of sensory axons in the solitary tract several hundred microns distal from the neuron of interest, allowing the precise examination of synaptic current or potential kinetics resulting from TS stimulation without the potential interference of stimulation artifacts or pathways activated outside of the intended fiber bundle.

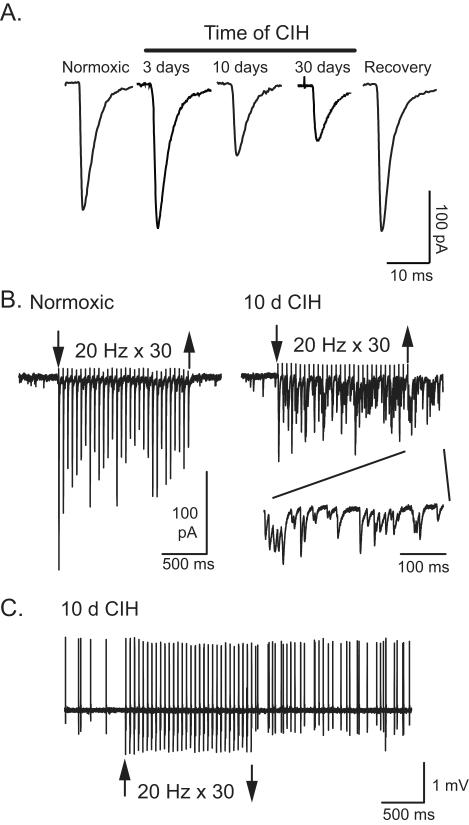

CIH augments chemosensory afferent activity, the central processing of afferent information, and its associated reflexes. Since the nTS is the first central site of chemoafferent integration, it was reasoned that intermittent hypoxia would strengthen afferent processing and neuronal activity in the nTS. Extracellular activity from cells in the medial and commissural nTS was examined first. In these recording experiments, the intracellular milieu remains undisturbed thereby eliminating the potential for changes in neuronal activity due to pipette impalement of the cell. Following ten days of CIH, more cells exhibited spontaneous discharge compared to their normoxic controls. In those spontaneously active CIH cells, the number of action potentials observed was also elevated. Stimulating the solitary tract to mimic increased sensory afferent activity induced discharge in CIH and normoxia exposed nTS cells. Interestingly, following the synchronous burst of activity that coincides with afferent stimulation, discharge in CIH cells remained elevated beyond the stimulation period (Figure 1C) whereas activity in normoxic cells promptly returned to their baseline. Taken together, these results indicate that CIH increases overall activity in nTS cells as well as their response to afferent input. An increase in chemoafferent fiber activity could contribute to this augmented discharge in nTS cells.

Figure 1. CIH induces synaptic and neuronal alterations in the nTS.

A. Representative examples of solitary tract-evoked EPSCs from cells following normoxia and 3, 10 and 30 days of CIH in the brainstem slice. Note the reduction in EPSCs following 10 and 30 days of CIH. Returning rats to room air conditions for two weeks following 10 days of CIH recovered EPSCs to that comparable to normoxia (pre-CIH). B. Ten day CIH synapses have reduced synchronous TS-EPSC amplitudes, frequency-dependant depression in TS-EPSCs and exaggerated asynchronous release during repetitive TS-stimulation. Representative tracing of EPSCs from a normoxic (left) and 10 day CIH (right) slice during repetitive stimulation (20 Hz, 30 episodes, at arrows). Note the increase in asynchronous EPSCs. Inset shows expanded traces of asynchronous currents. C. Example of action potential discharge during and following a stimulus train in a CIH cell. As in B, the TS was stimulated at 20 Hz for 30 episodes between the arrows. Action potential discharge is increased after ten days of CIH and is enhanced following afferent stimulation. The increase in asynchronous EPSCs following CIH (panel B, right) is sufficient to increase discharge. Panels B and C modified from Journal of Neuroscience with permission.

How might this augmentation in discharge occur in the nTS following CIH? To determine potential mechanisms, synaptic currents that represent the flow of information from the sensory axon to the nTS cell were evaluated. In horizontal slices from normoxic and CIH-conditioned rats, stimulation of the TS elicited glutamatergic excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in nTS cells which occurred in synchrony with each TS shock. Individual cells had a consistent shock-to-shock latency in EPSC initiation, which is a property of neurons receiving direct contact from afferent axons [i.e., “monosynaptic” cells, (Doyle and Andresen, 2001)]. Three days of CIH did not alter monosynaptic, TS-evoked EPSC amplitude, though it tended to be elevated. However, contrary to expectations, after 10 and 30 days of intermittent hypoxia, TS evoked EPSC amplitudes were reduced compared to their normoxic controls. Importantly, the reduced current that occurred from CIH was reversible. Rats that were exposed to 10 days of CIH followed by 14 days of returning to their normoxic environment had near control postsynaptic currents. Thus, CIH induces a time-dependent and reversible decrease in sensory afferent evoked synaptic transmission (Figure 1A). The mechanism(s) behind the reduced TS-evoked EPSCs following 10 days of CIH were then explored in more detail.

Potential mechanisms of decreased synaptic currents following 10 days of CIH could reflect changes in presynaptic neurotransmitter release, postsynaptic neuronal properties, or both. Several lines of evidence suggest that a reduction in presynaptic release of neurotransmitter is primarily responsible for alterations in evoked synaptic currents. One method to evaluate this relied on examining the mean2/variance of EPSCs, a measure of presynaptic changes in transmitter release attributable to alterations in synaptic strength (Malinow and Tsien, 1990). Manipulations that decrease synaptic efficacy (the capacity of a presynaptic input to influence a postsynaptic output) also decrease mean2/variance. This variable is dependent on the number of neurotransmitter release sites and release probability (Malinow and Tsien, 1990). Consistent with a decrease in TS-evoked EPSC amplitude, chronic intermittent hypoxia decreased mean2/variance of evoked EPSCs, suggesting a presynaptic decrease in neurotransmitter release. Further studies described below suggest a change in neurotransmitter release probability during TS stimulation occurs following CIH.

Miniature (m) EPSCs were recorded in the presence of the sodium channel blocker tetrodotoxin to block action potential generation and further differentiate presynaptic from postsynaptic mechanisms of synaptic depression in CIH. Analysis of mEPSC frequency provides information about possible changes in the presynaptic release process, whereas changes in the amplitudes of the miniature currents can reflect either alterations in postsynaptic receptor properties or presynaptic neurotransmitter vesicle packet size. The mEPSC amplitude as well as their rise and decay kinetics was similar between normoxic and CIH-conditioned cells, indicating differences in postsynaptic current were not attributable to changes in presynaptic vesicle size or receptor properties. CIH did not alter other synaptic current properties including TS-evoked EPSC decay time constants or desensitization of the α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) glutamate receptor which mediates glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the nTS. Both CIH cells and normoxic cells were also sensitive to non-N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor blockade. What’s more, CIH did not alter resting membrane potential, input resistance, or action potential properties of the postsynaptic cell. This preponderance of data suggests that under our preparation changes in presynaptic release properties are responsible for decreased evoked EPSC amplitude rather than changes in cellular properties or postsynaptic glutamate receptor alterations. Furthermore, these synaptic currents are mediated by non-NMDA glutamate receptors.

Other studies in primary dissociated nTS cells suggest CIH may also induce postsynaptic changes in receptor function. Following seven days of CIH, dispersed second-order nTS cells studied in vitro exhibited enhanced postsynaptic AMPA yet decreased NMDA receptor currents when exposed to brief agonist application (de Paula et al., 2007). AMPA receptor desensitization was not altered after 7 days of CIH. In our in vitro slice preparation, the NMDA receptor component was not examined as this receptor may be less important when studied at more negative membrane potentials in the presence of magnesium. Moreover, as stated above, TS-evoked EPSCs are fully blocked by non-NMDA receptor blockade. Nonetheless, NMDA receptors can contribute to synaptic transmission in the nTS (Aylwin et al., 1997). Activation of NMDA receptors from neurotransmitter spillover has also been observed in AMPA-only synapses (Clark and Cull-Candy, 2002). Such studies suggest potential important roles for NMDA receptor activation in CIH synaptic responses, especially when studied in the intact animal.

During hypoxic episodes, chemoafferent activity increases (Vidruk et al., 2001). Likewise, rises in blood pressure augment baroafferent activity (Andresen and Kunze, 1994). To mimic the increases in activity arising from sensory afferents a series of 30 stimuli at 20 Hz was delivered to the sensory afferent fibers in the TS. As characteristic for the nTS synapse (Doyle and Andresen, 2001; Kline et al., 2002; Kline et al., 2010a), the first evoked response was a large EPSC that was followed by smaller currents that were often half of the initial response (Figure 1B). This accommodation in synaptic activity was observed in cells from both normoxic and CIH-exposed rats. The size of the evoked current to each stimulus continued to be less in CIH cells. However, these CIH neurons had noticeably different synaptic currents in that they exhibited greater spontaneous activity during and following TS stimulation (Figure 1B). This “asynchronous” activity in CIH cells is indicative of exaggerated neurotransmitter release from the afferent synaptic terminal (Lu and Trussell, 2000; Catterall and Few, 2008) and could contribute to the increased nTS neuronal activity and augmented reflex responses observed in CIH. In addition to an increase in asynchronous neurotransmitter release, CIH cells also exhibit elevated background synaptic currents. This was observed as an enhanced frequency of miniature EPSCs when recorded in tetrodotoxin to block action potentials. Subsequent studies in other labs have confirmed this increase in spontaneous activity in CIH (Almado et al., 2008).

To determine whether the increase in asynchronous transmitter release in CIH is sufficient to induce action potential discharge, this recorded excitatory current was injected back into normoxic and CIH cells. Asynchronous EPSC activity significantly increased action potential discharge in cells from normoxic and CIH rats. This indicates that the increase in asynchronous activity in CIH is sufficient to induce action potential discharge as seen in this model. A recent study examining asynchronous EPSCs in the nTS produced similar findings. These studies demonstrate that asynchronous and solitary tract evoked EPSCs originate from the same afferent terminal and asynchronous transmitter can induce action potential discharge (Peters et al., 2010). Taken together, these data would suggest that despite the reduced evoked synaptic currents following CIH, these synapses continuously release more neurotransmitter under basal conditions and this transmitter release is enhanced following continuous afferent stimulation. The elevated miniature and asynchronous activity is likely to be responsible for short-term facilitation of action potential discharge when recorded in vitro. Such increases in activity may be even more important in vivo, as a persistent increase in chemosensory afferent activity has been observed in the CIH rat.

The amount of neurotransmitter released is directly related to extracellular calcium. Raising concentrations of extracellular calcium increases the probability of transmitter release and the resulting synaptic current (Catterall and Few, 2008). Conversely, reducing calcium decreases the probability of release and attenuates postsynaptic currents. The decrease in TS-evoked EPSCs in CIH may be due to changes in calcium handling or its effect on transmitter release in the presynaptic cell. Thus, it was reasoned that elevating external calcium would restore the reduced TS-evoked EPSC size in CIH cells to those of normoxic cells. Whether the increases in spontaneous synaptic currents with CIH, both asynchronous and miniature frequency, might be due to elevated calcium levels in the synaptic terminal (Catterall and Few, 2008; Glitsch, 2008) was also tested. In nTS cells from CIH-conditioned rats, the TS-evoked synaptic response is reduced and cannot be enhanced by increasing extracellular calcium concentration. Yet, the evoked response can be further reduced by decreasing calcium concentration. In contrast to the evoked response in CIH, spontaneous current frequency is elevated in higher calcium. Conversely, normoxic TS-evoked EPSCs can be proportionally altered with rising and falling external calcium. Thus, it would appear that following CIH, a calcium-dependent component that is responsible for evoked transmitter release has been altered. Concurrently, there is a functional shift in the synapse to release more neurotransmitter spontaneously and following afferent stimulation. The latter appears to rely on calcium.

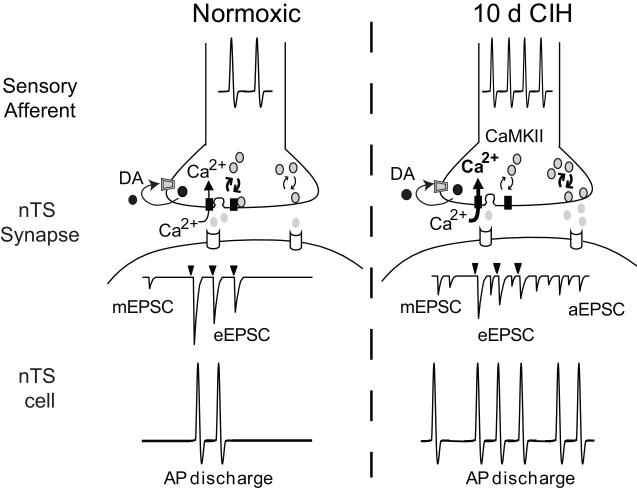

Protein kinases are activated by elevated intracellular calcium and can affect neurotransmitter release. The potential role of calcium-calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII) was examined based on its described role in synaptic plasticity (Wang, 2008). In CIH cells, pharmacological blockade of CaMKII increased the reduced TS-evoked EPSCs without affecting postsynaptic properties (Kline et al., 2007) or producing a consistent effect on spontaneous events. This coincided with an increase in the phosphorylated isoform of CaMKII in the nTS and sensory ganglia, which contain the cell bodies of sensory TS axons. By contrast, normoxic cell synaptic currents were not significantly altered by CaMKII blockade. Thus, one potential mechanism by which CIH induces synaptic depression with TS stimulation is through elevated basal calcium levels and activation of CaMKII. Increased activity of this kinase may phosphorylate other synaptic or ion channel proteins to reduce neurotransmitter release with each invading action potential (Wang, 2008). What those potential proteins are requires further investigation.

In summary, CIH induces a decrease in synchronous TS-evoked EPSCs while increasing spontaneous and asynchronous transmitter release. The increase in spontaneous release can be attributed to elevated synaptic calcium concentration (Catterall and Few, 2008; Glitsch, 2008). External calcium differentially alters spontaneous and evoked release in CIH, and at least a part of the decrease in synchronous TS-EPSCs arises from activation of CaMKII. What is the mechanism of these different effects of CIH on spontaneous and evoked currents and their sensitivity to calcium and CamKII blockade? Based on the available data, one may surmise thatCIH may differentially affect the vesicle pools responsible for spontaneous and evoked transmitter release [Figure 2, (Kline et al., 2007; Glitsch, 2008)]. The increase in internal calcium and activation of CaMKII blunts, in part, evoked neurotransmitter release. Concurrently, the increase in calcium increases miniature and asynchronous release during and following afferent stimulation and this process is independent of CaMKII. Directionally different regulation of vesicle pools has been observed in other preparations (Eliot et al., 1994; Zengel and Sosa, 1994; Cummings et al., 1996; Pan et al., 1996; Schoch et al., 2001; Washbourne et al., 2002; Sara et al., 2005) and recently in the nTS (Peters et al., 2010). Possible roles for the increased spontaneous miniature activity include maintaining or influencing the expression of receptors or ion channels on nTS cells, as well as the firing of compact neurons such as those in the nTS (Carter and Regehr, 2002; Glitsch, 2008). Asynchronous neurotransmitter release may function to prolong synaptic signaling, as shown in the continuation of excitatory (Peters et al., 2010) and inhibitory (Hefft and Jonas, 2005; Best and Regehr, 2009) neurotransmission. Thus, the increase in miniature and asynchrounous activity following CIH is a means in which CIH increases action potential discharge in nTS second order cells (Figure 2). Yet the question remains: are there other potential mechanisms?

Figure 2. Proposed model for synaptic alterations following CIH.

Schematic representation of alterations in a normoxic (left) and CIH (right) NTS synapse. Under normoxic conditions, a barrage of action potentials in the sensory afferent increases presynaptic calcium concentrations in the synaptic terminal, likely through the opening N-type calcium channel. This results in the release of the neurotransmitter glutamate from docked vesicles to produce EPSCs in the nTS cell. The downward filled arrowhead represents afferent stimulation which results in EPSCs. Synaptic vesicles are recycled to and from the evoked vesicle pool for synchronous release. Miniature and asynchronous transmitter release is at a minimum. Dopamine (DA) is also released from the afferent terminal and through its retrograde binding of D2 receptors decreases glutamate release. The sum of this activity results in action potential discharge in the nTS cell upon TS stimulation. The balance of inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitter release is responsible for postsynaptic activity.

Following CIH exposure (right), the increase in action potential frequency in the sensory afferent axon leads to an increase in intracellular calcium, likely through the N-type calcium channel. The increase in calcium activates CaMKII to reduce evoked, synchronous transmitter release from the synaptic terminal. An alteration of presynaptic calcium buffering or other mechanism may also occur. Concurrently, the increase in intracellular calcium significantly augments miniature and asynchronous release. The resulting effect is a decrease in evoked, synchronous release and an increase in baseline miniature release as well as asynchronous release during and following afferent stimulation. The latter may result from elevation of the spontaneous neurotransmitter vesicle pool. The increase in miniature and asynchronous activity, coupled with synchronous release (although reduced), results in greater activity of nTS cells. Dopamine release and activation of presynaptic D2 receptors continues to play a role following CIH. NOTE: Arrow thickness and bold font denotes proposed increased weight of a given pathway to the observed results.

Several neurotransmitters and modulators have been examined in synaptic neurotransmission and its plasticity in the nTS. The role of dopamine on TS-evoked EPSCs under control and following CIH was recently studied (Kline et al., 2002; Kline et al., 2009). Since CIH alters tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) expression and/or function in the carotid body, brainstem and forebrain (Hui et al., 2003; Raghuraman et al., 2009), perhaps catecholamines may play a prominent role in reducing TS-EPSCs in the nTS after CIH. Several lines of evidence suggest dopamine plays a role in the nTS and chemoreflex. Dopamine is one of the first neurotransmitters generated in the catecholamine synthesis pathway and is a precursor to epinephrine and norepinepherine. Dopamine is released from afferent fibers upon activation of the chemoreflex in the rabbit (Goiny et al., 1991) and its receptors have also been localized in the brainstem, including the nTS, where they are up regulated by chronic hypoxia (Huey and Powell, 2000). Dopamine is also elevated following CIH in the carotid body (Hui et al., 2003), brainstem (Raghuraman et al., 2009), and hypothalamus (Li et al., 1996). The role of dopamine in nTS synaptic transmission in normoxia and in the induction of CIH-induced synaptic depression was therefore examined.

In the in vitro nTS slice, dopamine and the D2 agonist quinpirole reduce synaptic transmission to nTS cells that are directly apposed with fluorescently-tagged chemoreceptor and vagal afferent sensory boutons (Kline et al., 2002). Dopamine-mediated synaptic reduction was due primarily to activation of presynaptic D2-like receptors. Moreover, blockade of these receptors increased synaptic transmission suggesting that dopamine is tonically released from chemoreceptor and vagal afferents to persistently attenuate neurotransmission. Does an increase in tonic D2 activation mediate the synaptic depression seen in the CIH model? If so, this effect could occur by an inhibition of presynaptic calcium channels due to either an increase in presynaptic D2 receptors or dopamine release. Dopamine did inhibit TS-evoked EPSC amplitude in normoxic and CIH cells; however, inhibition of current size was comparable between both groups of cells. Additionally, blockade of D2 receptors increased EPSC amplitude in normoxic and CIH second-order nTS cells, yet the magnitude of increase was also comparable between the two groups. D2 blockade in CIH cells did also not increase synaptic current size to the levels seen in normoxic cells. In short, D2 dopamine receptors were functional in both normoxic and 10 day CIH cells.

What then is the mechanism of dopamine’s reduction of synaptic transmission in normoxia and CIH? To explore that question, the N-type calcium channel was initially examined based on its role as the primary mediator of calcium-induced vesicle release in nTS sensory afferents (Mendelowitz et al., 1995), and its ability to reduce synaptic transmission upon blockade (Missale et al., 1998; Momiyama and Koga, 2001; Lisman et al., 2007). These studies focused on isolated sensory neurons and the in vitro brainstem slice.

In sensory neurons isolated from the nodose-petrosal ganglion, including labeled petrosal cells projecting from the carotid body, dopamine and the D2 receptor agonist quinpirole decreased calcium currents. Blockade of the N-type, but not P/Q- and L-type, calcium channel ablated the D2-mediated attenuation of calcium entry. Activation of D2 receptors also inhibited N-type calcium in cells isolated from CIH rats. However, the magnitude of inhibition by the D2 receptor was comparable between normoxic and CIH cells.

Confocal imaging was subsequently used to determine if a similar mechanism occurred in the central nTS terminals of sensory neurons. In these studies, the nodose-petrosal ganglion was isolated in vivo and labeled with a calcium indicator, which was then transported to the nTS. Stimulating the TS in the in vitro slice at frequencies similar to electrophysiological studies increased the fluorescence intensity of synaptic terminals that is indicative of a rise in internal calcium. Similar to what was seen in isolated cells, activation of D2 receptors significantly decreased calcium fluorescence during TS stimulation, and this effect was due to attenuation of N-type channels. These data demonstrate activation of D2 receptors in the nTS decreases calcium entry in the afferent synaptic terminal as well as in their somas, and suggests the decrease in calcium entry by dopamine reduces synaptic transmission. However, these data, together with EPSC data, suggest dopamine is not the sole source of synaptic inhibition in the nTS following CIH, at least not in the studied isolated preparations. Whether it plays a more significant role in an in vivo model remains to be determined.

6. CIH potentiates sympathetic nerve activity and breathing. What’s the role of the nTS?

Exposing animals to CIH, as is observed in sleep apnea patients, induces a robust respiratory and sympathoexcitatory response which leads to hypertension. Sympathetic nervous system activity is elevated in patients with recurrent apneas as well as in their CIH animal models. In some patients, changes in basal respiration may also occur (Prabhakar and Kline, 2002). Following CIH, increases in nTS synaptic input and the resulting elevation of postsynaptic activity may contribute to autonomic and respiratory alterations, as well as cardiorespiratory coupling. In the 10 day CIH rat, an increased cardiovascular-respiratory coupling is seen during and following CIH (Zoccal et al., 2008; Zoccal et al., 2009b). This is demonstrated by an increase in sympathetic nerve activity during expiration. A similar cardio-respiratory coupling occurs during acute hypoxia (Dick et al., 2004). Possible sites for such coupling include the rostral (Zoccal et al., 2009b) and caudal (Mandel and Schreihofer, 2006; Mandel and Schreihofer, 2009) ventrolateral medulla, pons (Dick et al., 2009) and possibly many others. The nTS sends projections to all of these regions and thus has the potential to play a large role. Interestingly, glutamatergic inputs in the caudal and intermediate nTS that are activated by the chemoreflex have been suggested to mediate some forms of cardiorespiratory coupling (Costa Silva et al., 2010). Whether CIH-induced increases in spontaneous and asynchronous neurotransmitter release, as well as postsynaptic discharge, in the caudal nTS contribute to this phenomenon is an intriguing question warranting further investigation.

7. Future research directions

Obviously, many questions remain unanswered. For instance, what is the identity of the afferents which are altered in CIH? Is this adaption to CIH specific for chemoreceptors or do baroreceptor afferents also exhibit CIH-induced modifications? Sensory afferents express several modalities, such as unmyelinated C-fibers and myelinated A-fibers (Andresen et al., 2004). Are these fiber types differentially altered by CIH? The majority of carotid sinus nerve fibers are unmyelinated fibers (McDonald, 1983), suggesting at least a portion of those nTS cells recorded in our studies received C-fiber inputs. Recent studies have also suggested that C-fibers exhibit greater asynchronous activity than myelinated A-fibers (Peters et al., 2010). How is this increase in chemosensory information conveyed from the nTS to increase sympathetic activity, respiration and possibly cardiorespiratory coupling? The nTS neurons which project to the RVLM, the central site for generation sympathetic nerve activity, have been shown to receive chemoafferent signals from direct monosynaptic connections and be activated by hypoxia (Koshiya and Guyenet, 1996; Accorsi-Mendonca et al., 2009; Kline et al., 2010a). A conceivable pathway activated by CIH is one in which chemoafferent signals are processed in the nTS and directly sent to the RVLM. Is the activity in those RVLM-projecting nTS neurons -- or perhaps those which project to the hypothalamus, caudal ventrolateral medulla, or pons -- altered in CIH? Are there other potential receptors, neurotransmitters and neuromodulators altered in CIH? Does the increase in spontaneous glutamate release result in spill over at the synapse to activate other receptors in vivo? For instance, serotonergic mechanisms are thought to play a role in respiratory long-term facilitation after CIH (Ling et al., 2001). Brain derived neurotrophic factor modulates synaptic function in the nTS (Kline et al., 2010b), and is increased in expression following CIH in the ventral spinal cord in the vicinity of phrenic nucleus (Wilkerson and Mitchell, 2009). GABA is a major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the nTS and is altered following hypoxia (Tolstykh et al., 2004). Do these neurochemicals play a role? What causes the hypertension to reverse after normal oxygen conditions are resumed? The prolonged time required for reversing synaptic dysfunction following CIH or the return of arterial pressure or sympathetic activity in humans suggests long-term changes in gene and/or protein expression. Advancing molecular and proteonomic techniques will soon allow us to determine on a cellular level these potential changes following CIH.

8. Summary

The reduced size of the synaptic current may be an adaptive response to place a brake on increased chemoafferent activity. This brake may stabilize breathing during robust chemoreceptor activation as seen during CIH. It may also, however, contribute to increased sympathetic nerve activity. This intrinsic adaptation of synaptic circuits to maintain function is analogous to homeostatic plasticity observed in other central nuclei (Turrigiano, 2007) and in the nTS (Chen et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2003). Such homeostatic adaptations are well known to those studying the autonomic nervous and respiratory systems.

As discussed, the nTS is well suited for the processing and modulation of afferent activity that results in the cardiorespiratory reflexes during a hypoxic challenge. The nTS expresses several forms of synaptic plasticity over short and long time domains, including those which occur in CIH. Following intermittent hypoxia, an increase in postsynaptic activity is initiated by enhanced presynaptic spontaneous neurotransmitters release. A decrease in evoked release attempts to counterbalance this augmented asynchronous transmitter release. This nTS activity may be sent to one or more cardiovascular and respiratory nuclei. The numerous reciprocal projections make the nTS ideal for integrating information from sensory afferents and various nuclei to ultimately modulate sympathetic nerve activity, respiration or its coupling during a hypoxic challenge. Nonetheless, much work is needed to fully understand this nucleus and the role it plays in health and disease.

Acknowledgements

I thank Drs. E.M. Hasser and J.R. Austgen for critical review of earlier drafts of this manuscript. The majority of this work examining CIH was done in collaboration with Dr. Diana L. Kunze of Case Western Reserve University. The work reported herein was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute [HL-085108 (DDK) and HL-25830 (DLK)].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Accorsi-Mendonca D, Bonagamba LG, Leao RM, Machado BH. Are L-glutamate and ATP cotransmitters of the peripheral chemoreflex in the rat nucleus tractus solitarius? Exp.Physiol. 2009;94:38–45. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.043653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai J, Wurster RD, Harden SW, Cheng ZJ. Vagal afferent innervation and remodeling in the aortic arch of young-adult fischer 344 rats following chronic intermittent hypoxia. Neuroscience. 2009;164:658–666. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almado CEL, Accorsi-Mendonca D, Machado BH, Leao RMX. Chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH) enhances spontaneous synaptic transmission in the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) neurons of juvenile rats. The FASEB Journal. 2008;22 1171.19. [Google Scholar]

- Andresen MC, Doyle MW, Bailey TW, Jin YH. Differentiation of autonomic reflex control begins with cellular mechanisms at the first synapse within the nucleus tractus solitarius. Braz.J.Med.Biol.Res. 2004;37:549–558. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004000400012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen MC, Kunze DL. Nucleus tractus solitarius--gateway to neural circulatory control. Annu.Rev.Physiol. 1994;56:93–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylwin ML, Horowitz JM, Bonham AC. NMDA receptors contribute to primary visceral afferent transmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract. J.Neurophysiol. 1997;77:2539–2548. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.5.2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best AR, Regehr WG. Inhibitory regulation of electrically coupled neurons in the inferior olive is mediated by asynchronous release of GABA. Neuron. 2009;62:555–565. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley TD, Floras JS. Obstructive sleep apnoea and its cardiovascular consequences. Lancet. 2009;373:82–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61622-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga VA, Soriano RN, Machado BH. Sympathoexcitatory response to peripheral chemoreflex activation is enhanced in juvenile rats exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia. Exp.Physiol. 2006;91:1025–1031. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2006.034868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AG, Regehr WG. Quantal events shape cerebellar interneuron firing. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1309–1318. doi: 10.1038/nn970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Few AP. Calcium channel regulation and presynaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008;59:882–901. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Bonham AC, Plopper CG, Joad JP. Neuroplasticity in nucleus tractus solitarius neurons after episodic ozone exposure in infant primates. J.Appl.Physiol. 2003;94:819–827. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00552.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Bonham AC, Schelegle ES, Gershwin LJ, Plopper CG, Joad JP. Extended allergen exposure in asthmatic monkeys induces neuroplasticity in nucleus tractus solitarius. J.Allergy Clin.Immunol. 2001;108:557–562. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.118132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark BA, Cull-Candy SG. Activity-dependent recruitment of extrasynaptic NMDA receptor activation at an AMPA receptor-only synapse. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4428–4436. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04428.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa Silva JH, Zoccal DB, Machado BH. Glutamatergic antagonism in the NTS decreases post-inspiratory drive and changes phrenic and sympathetic coupling during chemoreflex activation. J Neurophysiol. 2010 doi: 10.1152/jn.00802.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings DD, Wilcox KS, Dichter MA. Calcium-dependent paired-pulse facilitation of miniature EPSC frequency accompanies depression of EPSCs at hippocampal synapses in culture. J.Neurosci. 1996;16:5312–5323. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05312.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Paula PM, Tolstykh G, Mifflin SW. Chronic intermittent hypoxia alters NMDA and AMPA-evoked currents in NTS neurons receiving carotid body chemoreceptor inputs. Am.J.Physiol Regul.Integr.Comp Physiol. 2007 doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00760.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick TE, Baekey DM, Paton JF, Lindsey BG, Morris KF. Cardio-respiratory coupling depends on the pons. Respir.Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;168:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick TE, Hsieh YH, Morrison S, Coles SK, Prabhakar N. Entrainment pattern between sympathetic and phrenic nerve activities in the Sprague-Dawley rat: hypoxia-evoked sympathetic activity during expiration. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;286:R1121–R1128. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00485.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty LS, Kiely JL, Swan V, McNicholas WT. Long-term effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy on cardiovascular outcomes in sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 2005;127:2076–2084. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle MW, Andresen MC. Reliability of monosynaptic sensory transmission in brain stem neurons in vitro. J.Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2213–2223. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliot LS, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. Modulation of spontaneous transmitter release during depression and posttetanic potentiation of Aplysia sensory-motor neuron synapses isolated in culture. J.Neurosci. 1994;14:3280–3292. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-03280.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley JC, Katz DM. The central organization of carotid body afferent projections to the brainstem of the rat. Brain Res. 1992;572:108–116. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90458-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher EC, Bao G. The rat as a model of chronic recurrent episodic hypoxia and effect upon systemic blood pressure. Sleep. 1996;19:S210–S212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher EC, Lesske J, Behm R, Miller CC, III, Stauss H, Unger T. Carotid chemoreceptors, systemic blood pressure, and chronic episodic hypoxia mimicking sleep apnea. J.Appl.Physiol. 1992;72:1978–1984. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.5.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glitsch MD. Spontaneous neurotransmitter release and Ca2+--how spontaneous is spontaneous neurotransmitter release? Cell Calcium. 2008;43:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goiny M, Lagercrantz H, Srinivasan M, Ungerstedt U, Yamamoto Y. Hypoxia-mediated in vivo release of dopamine in nucleus tractus solitarii of rabbits. J.Appl.Physiol. 1991;70:2395–2400. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.6.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg HE, Sica AL, Scharf SM, Ruggiero DA. Expression of c-fos in the rat brainstem after chronic intermittent hypoxia. Brain Res. 1999;816:638–645. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H, Lin M, Liu J, Gozal D, Scrogin KE, Wurster R, Chapleau MW, Ma X, Cheng ZJ. Selective impairment of central mediation of baroreflex in anesthetized young adult Fischer 344 rats after chronic intermittent hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ.Physiol. 2007;293:H2809–H2818. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00358.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasser EM, Moffitt JA. Regulation of sympathetic nervous system function after cardiovascular deconditioning. Ann.N.Y.Acad.Sci. 2001;940:454–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefft S, Jonas P. Asynchronous GABA release generates long-lasting inhibition at a hippocampal interneuron-principal neuron synapse. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1319–1328. doi: 10.1038/nn1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Housley GD, Martin-Body RL, Dawson NJ, Sinclair JD. Brain stem projections of the glossopharyngeal nerve and its carotid sinus branch in the rat. Neuroscience. 1987;22:237–250. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Lusina S, Xie T, Ji E, Xiang S, Liu Y, Weiss JW. Sympathetic response to chemostimulation in conscious rats exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia. Respir.Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;166:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey KA, Powell FL. Time-dependent changes in dopamine D(2)-receptor mRNA in the arterial chemoreflex pathway with chronic hypoxia. Brain Res.Mol.Brain Res. 2000;75:264–270. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00321-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui AS, Striet JB, Gudelsky G, Soukhova GK, Gozal E, Beitner-Johnson D, Guo SZ, Sachleben LR, Jr., Haycock JW, Gozal D, Czyzyk-Krzeska MF. Regulation of catecholamines by sustained and intermittent hypoxia in neuroendocrine cells and sympathetic neurons. Hypertension. 2003;42:1130–1136. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000101691.12358.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M, Adachi T, Koshino Y, Somers VK. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease. Circ.J. 2009;73:1363–1370. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DD. Plasticity in glutamatergic NTS neurotransmission. Respir.Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;164:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DD, Hendricks G, Hermann G, Rogers RC, Kunze DL. Dopamine inhibits N-type channels in visceral afferents to reduce synaptic transmitter release under normoxic and chronic intermittent hypoxic conditions. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:2270–2278. doi: 10.1152/jn.91304.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DD, King TL, Austgen JR, Heesch CM, Hasser EM. Sensory afferent and hypoxia-mediated activation of nucleus tractus solitarius neurons that project to the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Neuroscience. 2010a doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DD, Ogier M, Kunze DL, Katz DM. Exogenous Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor Resues Synaptic Dysfunction in Mecp2 Null Mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010b doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5503-09.2010. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DD, Ramirez-Navarro A, Kunze DL. Adaptive depression in synaptic transmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract after in vivo chronic intermittent hypoxia: evidence for homeostatic plasticity. J.Neurosci. 2007;27:4663–4673. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4946-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DD, Takacs KN, Ficker E, Kunze DL. Dopamine modulates synaptic transmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract. J.Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2736–2744. doi: 10.1152/jn.00224.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiya N, Guyenet PG. NTS neurons with carotid chemoreceptor inputs arborize in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Am.J.Physiol. 1996;270:R1273–R1278. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.6.R1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar GK, Rai V, Sharma SD, Ramakrishnan DP, Peng YJ, Souvannakitti D, Prabhakar NR. Chronic intermittent hypoxia induces hypoxia-evoked catecholamine efflux in adult rat adrenal medulla via oxidative stress. J.Physiol. 2006;575:229–239. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.112524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvochina L, Hasser EM, Heesch CM. Pregnancy increases baroreflex-independent GABAergic inhibition of the RVLM in rats. Am.J.Physiol Regul.Integr.Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R2295–R2305. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00365.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Bao G, el-Mallakh RS, Fletcher EC. Effects of chronic episodic hypoxia on monoamine metabolism and motor activity. Physiol Behav. 1996;60:1071–1076. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(96)00149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M, Liu R, Gozal D, Wead WB, Chapleau MW, Wurster R, Cheng ZJ. Chronic intermittent hypoxia impairs baroreflex control of heart rate but enhances heart rate responses to vagal efferent stimulation in anesthetized mice. Am.J.Physiol Heart Circ.Physiol. 2007;293:H997–1006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01124.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling L, Fuller DD, Bach KB, Kinkead R, Olson EB, Jr., Mitchell GS. Chronic intermittent hypoxia elicits serotonin-dependent plasticity in the central neural control of breathing. J.Neurosci. 2001;21:5381–5388. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05381.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, Raghavachari S, Tsien RW. The sequence of events that underlie quantal transmission at central glutamatergic synapses. Nat.Rev.Neurosci. 2007;8:597–609. doi: 10.1038/nrn2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Trussell LO. Inhibitory transmission mediated by asynchronous transmitter release. Neuron. 2000;26:683–694. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinow R, Tsien RW. Presynaptic enhancement shown by whole-cell recordings of long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices. Nature. 1990;346:177–180. doi: 10.1038/346177a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel DA, Schreihofer AM. Central respiratory modulation of barosensitive neurones in rat caudal ventrolateral medulla. J Physiol. 2006;572:881–896. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel DA, Schreihofer AM. Modulation of the sympathetic response to acute hypoxia by the caudal ventrolateral medulla in rats. J Physiol. 2009;587:461–475. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.161760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald DM. Morphology of the rat carotid sinus nerve. II. Number and size of axons. J Neurocytol. 1983;12:373–392. doi: 10.1007/BF01159381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelowitz D, Reynolds PJ, Andresen MC. Heterogeneous functional expression of calcium channels at sensory and synaptic regions in nodose neurons. J.Neurophysiol. 1995;73:872–875. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.2.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelini LC, Stern JE. Exercise-induced neuronal plasticity in central autonomic networks: role in cardiovascular control. Exp.Physiol. 2009;94:947–960. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.047449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mifflin SW. Arterial chemoreceptor input to nucleus tractus solitarius. Am.J.Physiol. 1992;263:R368–R375. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.263.2.R368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missale C, Nash SR, Robinson SW, Jaber M, Caron MG. Dopamine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:189–225. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momiyama T, Koga E. Dopamine D(2)-like receptors selectively block N-type Ca(2+) channels to reduce GABA release onto rat striatal cholinergic interneurones. J.Physiol. 2001;533:479–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0479a.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkiewicz K, Kato M, Phillips BG, Pesek CA, Davison DE, Somers VK. Nocturnal continuous positive airway pressure decreases daytime sympathetic traffic in obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation. 1999a;100:2332–2335. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.23.2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkiewicz K, van de Borne PJ, Montano N, Dyken ME, Phillips BG, Somers VK. Contribution of tonic chemoreflex activation to sympathetic activity and blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation. 1998;97:943–945. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.10.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkiewicz K, van de Borne PJ, Pesek CA, Dyken ME, Montano N, Somers VK. Selective potentiation of peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity in obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation. 1999b;99:1183–1189. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.9.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan ZH, Segal MM, Lipton SA. Nitric oxide-related species inhibit evoked neurotransmission but enhance spontaneous miniature synaptic currents in central neuronal cultures. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1996;93:15423–15428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel KP. Role of paraventricular nucleus in mediating sympathetic outflow in heart failure. Heart Fail.Rev. 2000;5:73–86. doi: 10.1023/A:1009850224802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Overholt JL, Kline D, Kumar GK, Prabhakar NR. Induction of sensory long-term facilitation in the carotid body by intermittent hypoxia: implications for recurrent apneas. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2003;100:10073–10078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1734109100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Prabhakar NR. Effect of two paradigms of chronic intermittent hypoxia on carotid body sensory activity. J.Appl.Physiol. 2004;96:1236–1242. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00820.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Rennison J, Prabhakar NR. Intermittent hypoxia augments carotid body and ventilatory response to hypoxia in neonatal rat pups. J.Appl.Physiol. 2004;97:2020–2025. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00876.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Yuan G, Ramakrishnan D, Sharma SD, Bosch-Marce M, Kumar GK, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Heterozygous HIF-1alpha deficiency impairs carotid body-mediated systemic responses and reactive oxygen species generation in mice exposed to intermittent hypoxia. J.Physiol. 2006;577:705–716. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JH, McDougall SJ, Fawley JA, Smith SM, Andresen MC. Primary Afferent Activation of Thermosensitive TRPV1 Triggers Asynchronous Glutamate Release at Central Neurons. Neuron. 2010;65:657–669. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar NR, Kline DD. Ventilatory changes during intermittent hypoxia: importance of pattern and duration. High Alt.Med.Biol. 2002;3:195–204. doi: 10.1089/15270290260131920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghuraman G, Rai V, Peng YJ, Prabhakar NR, Kumar GK. Pattern-specific sustained activation of tyrosine hydroxylase by intermittent hypoxia: role of reactive oxygen species-dependent downregulation of protein phosphatase 2A and upregulation of protein kinases. Antioxid.Redox.Signal. 2009;11:1777–1789. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey S, Del RR, Alcayaga J, Iturriaga R. Chronic intermittent hypoxia enhances cat chemosensory and ventilatory responses to hypoxia. J.Physiol. 2004;560:577–586. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.072033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sara Y, Virmani T, Deak F, Liu X, Kavalali ET. An isolated pool of vesicles recycles at rest and drives spontaneous neurotransmission. Neuron. 2005;45:563–573. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch S, Deak F, Konigstorfer A, Mozhayeva M, Sara Y, Sudhof TC, Kavalali ET. SNARE function analyzed in synaptobrevin/VAMP knockout mice. Science. 2001;294:1117–1122. doi: 10.1126/science.1064335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers VK, Abboud FM. Chemoreflexes--responses, interactions and implications for sleep apnea. Sleep. 1993;16:S30–S33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicuzza L, Bernardi L, Balsamo R, Ciancio N, Polosa R, Di MG. Effect of treatment with nasal continuous positive airway pressure on ventilatory response to hypoxia and hypercapnia in patients with sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 2006;130:774–779. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.3.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafil-Klawe M, Thiele AE, Raschke F, Mayer J, Peter JH, von WW. Peripheral chemoreceptor reflex in obstructive sleep apnea patients; a relationship between ventilatory response to hypoxia and nocturnal bradycardia during apnea events. Pneumologie. 1991;45(Suppl 1):309–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolstykh G, Belugin S, Mifflin S. Responses to GABA(A) receptor activation are altered in NTS neurons isolated from chronic hypoxic rats. Brain Res. 2004;1006:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano G. Homeostatic signaling: the positive side of negative feedback. Curr.Opin.Neurobiol. 2007;17:318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Giersbergen PL, Palkovits M, De JW. Involvement of neurotransmitters in the nucleus tractus solitarii in cardiovascular regulation. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:789–824. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.3.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardhan A, Kachroo A, Sapru HN. Excitatory amino acid receptors in commissural nucleus of the NTS mediate carotid chemoreceptor responses. Am.J.Physiol. 1993;264:R41–R50. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.1.R41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidruk EH, Olson EB, Jr., Ling L, Mitchell GS. Responses of single-unit carotid body chemoreceptors in adult rats. J.Physiol. 2001;531:165–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0165j.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZW. Regulation of synaptic transmission by presynaptic CaMKII and BK channels. Mol.Neurobiol. 2008;38:153–166. doi: 10.1007/s12035-008-8039-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washbourne P, Thompson PM, Carta M, Costa ET, Mathews JR, Lopez-Bendito G, Molnar Z, Becher MW, Valenzuela CF, Partridge LD, Wilson MC. Genetic ablation of the t-SNARE SNAP-25 distinguishes mechanisms of neuroexocytosis. Nat.Neurosci. 2002;5:19–26. doi: 10.1038/nn783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson JE, Mitchell GS. Daily intermittent hypoxia augments spinal BDNF levels, ERK phosphorylation and respiratory long-term facilitation. Exp.Neurol. 2009;217:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengel JE, Sosa MA. Changes in MEPP frequency during depression of evoked release at the frog neuromuscular junction. J.Physiol. 1994;477(Pt 2):267–277. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoccal DB, Bonagamba LG, Oliveira FR, ntunes-Rodrigues J, Machado BH. Increased sympathetic activity in rats submitted to chronic intermittent hypoxia. Exp.Physiol. 2007;92:79–85. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2006.035501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoccal DB, Bonagamba LG, Paton JF, Machado BH. Sympathetic-mediated hypertension of awake juvenile rats submitted to chronic intermittent hypoxia is not linked to baroreflex dysfunction. Exp.Physiol. 2009a;94:972–983. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.048306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoccal DB, Paton JF, Machado BH. Do changes in the coupling between respiratory and sympathetic activities contribute to neurogenic hypertension? Clin.Exp.Pharmacol.Physiol. 2009b;36:1188–1196. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoccal DB, Simms AE, Bonagamba LG, Braga VA, Pickering AE, Paton JF, Machado BH. Increased sympathetic outflow in juvenile rats submitted to chronic intermittent hypoxia correlates with enhanced expiratory activity. J Physiol. 2008;586:3253–3265. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.154187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]