Abstract

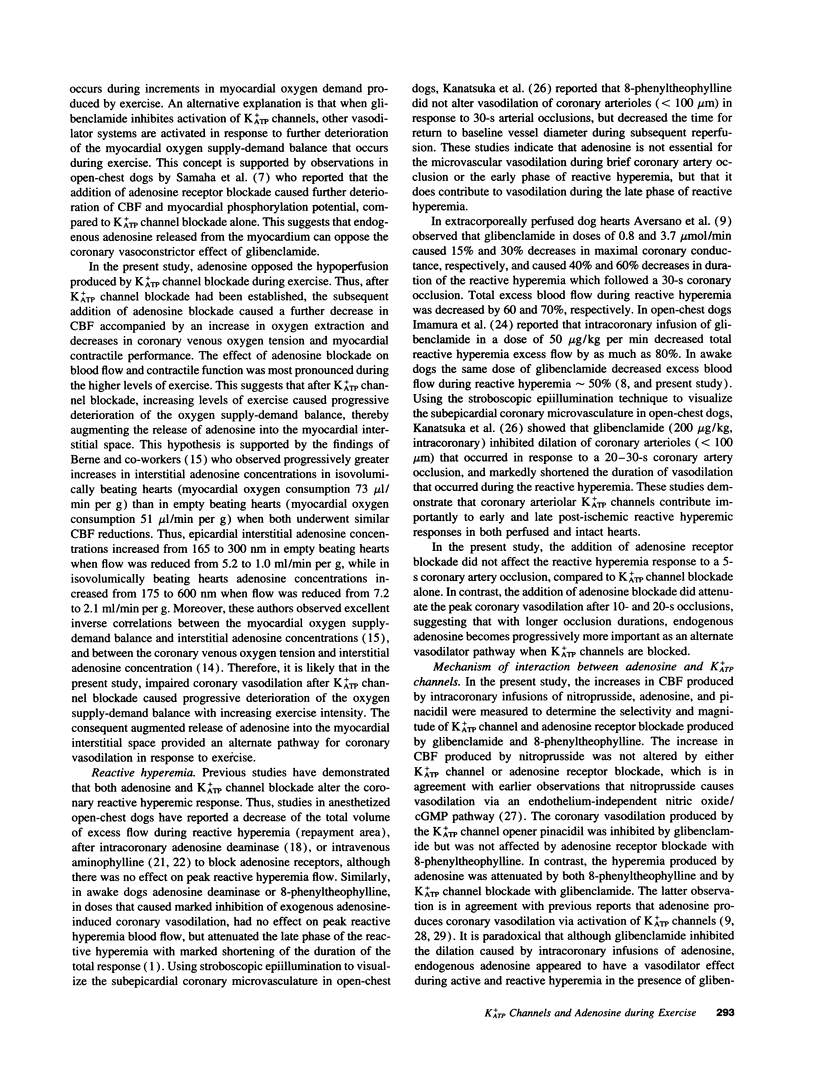

The mechanism of coronary vasodilation produced by exercise is not understood completely. Recently, we reported that blockade of vascular smooth muscle K(ATP)+ channels decreased coronary blood flow at rest, but did not attenuate the increments in coronary flow produced by exercise. Adenosine is not mandatory for maintaining basal coronary flow, or the increase in flow produced by exercise during normal arterial inflow, but does contribute to coronary vasodilation in hypoperfused myocardium. Therefore, we investigated whether adenosine opposed the hypoperfusion produced by K(ATP)+ channel blockade, thereby contributing to coronary vasodilation during exercise. 11 dogs were studied at rest and during exercise under control conditions, during intracoronary infusion of the K(ATP)+ channel blocker glibenclamide (50 micrograms/kg per min), and during intracoronary glibenclamide in the presence of adenosine receptor blockade. Glibenclamide decreased resting coronary blood flow from 45 +/- 5 to 35 +/- 4 ml/min (P < 0.05), but did not prevent exercise-induced increases of coronary flow. Glibenclamide caused an increase in myocardial oxygen extraction at the highest level of exercise with a decrease in coronary venous oxygen tension from 15.5 +/- 0.7 to 13.6 +/- 0.8 mmHg (P < 0.05). The addition of the adenosine receptor antagonist 8-phenyltheophylline (5 mg/kg intravenous) to K(ATP)+ channel blockade did not further decrease resting coronary blood flow but did attenuate the increase in coronary flow produced by exercise. This was accompanied by a further decrease of coronary venous oxygen tension to 10.1 +/- 0.7 mmHg (P < 0.05), indicating aggravation of the mismatch between oxygen demand and supply. These findings are compatible with the hypothesis that K+ATP channels modulate coronary vasomotor tone both under resting conditions and during exercise. However, when K(ATP)+ channels are blocked, adenosine released from the hypoperfused myocardium provides an alternate mechanism to mediate coronary vasodilation in response to increases in oxygen demand produced by exercise.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Altman J. D., Kinn J., Duncker D. J., Bache R. J. Effect of inhibition of nitric oxide formation on coronary blood flow during exercise in the dog. Cardiovasc Res. 1994 Jan;28(1):119–124. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aversano T., Ouyang P., Silverman H. Blockade of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel modulates reactive hyperemia in the canine coronary circulation. Circ Res. 1991 Sep;69(3):618–622. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.3.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchus A. N., Ely S. W., Knabb R. M., Rubio R., Berne R. M. Adenosine and coronary blood flow in conscious dogs during normal physiological stimuli. Am J Physiol. 1982 Oct;243(4):H628–H633. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.243.4.H628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bache R. J., Dai X. Z., Schwartz J. S., Homans D. C. Role of adenosine in coronary vasodilation during exercise. Circ Res. 1988 Apr;62(4):846–853. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.4.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloni F. L., Hintze T. H. Glibenclamide attenuates adenosine-induced bradycardia and coronary vasodilatation. Am J Physiol. 1991 Sep;261(3 Pt 2):H720–H727. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.3.H720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X. Z., Bache R. J. Effect of indomethacin on coronary blood flow during graded treadmill exercise in the dog. Am J Physiol. 1984 Sep;247(3 Pt 2):H452–H458. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.247.3.H452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncker D. J., Bache R. J. Inhibition of nitric oxide production aggravates myocardial hypoperfusion during exercise in the presence of a coronary artery stenosis. Circ Res. 1994 Apr;74(4):629–640. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncker D. J., Laxson D. D., Lindstrom P., Bache R. J. Endogenous adenosine and coronary vasoconstriction in hypoperfused myocardium during exercise. Cardiovasc Res. 1993 Sep;27(9):1592–1597. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.9.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncker D. J., Van Zon N. S., Altman J. D., Pavek T. J., Bache R. J. Role of K+ATP channels in coronary vasodilation during exercise. Circulation. 1993 Sep;88(3):1245–1253. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlund A., Sollevi A., Wennmalm A. The role of adenosine and prostacyclin in coronary flow regulation in healthy man. Acta Physiol Scand. 1989 Jan;135(1):39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1989.tb08548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz H., Olsson R. A., Brautigan D. L., Brown P. R., Most A. S. Adenosine's role in regulating basal coronary arteriolar tone. Am J Physiol. 1986 Jun;250(6 Pt 2):H1030–H1036. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.250.6.H1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles R. W., Wilcken D. E. Reactive hyperaemia in the dog heart: inter-relations between adenosine, ATP, and aminophylline and the effect of indomethacin. Cardiovasc Res. 1977 Mar;11(2):113–121. doi: 10.1093/cvr/11.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley F. L., Grattan M. T., Stevens M. B., Hoffman J. I. Role of adenosine in coronary autoregulation. Am J Physiol. 1986 Apr;250(4 Pt 2):H558–H566. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.250.4.H558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison D. G., Bates J. N. The nitrovasodilators. New ideas about old drugs. Circulation. 1993 May;87(5):1461–1467. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.5.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headrick J. P., Ely S. W., Matherne G. P., Berne R. M. Myocardial adenosine, flow, and metabolism during adenosine antagonism and adrenergic stimulation. Am J Physiol. 1993 Jan;264(1 Pt 2):H61–H70. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.1.H61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headrick J. P., Matherne G. P., Berr S. S., Berne R. M. Effects of graded perfusion and isovolumic work on epicardial and venous adenosine and cytosolic metabolism. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1991 Mar;23(3):309–324. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(91)90067-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura Y., Tomoike H., Narishige T., Takahashi T., Kasuya H., Takeshita A. Glibenclamide decreases basal coronary blood flow in anesthetized dogs. Am J Physiol. 1992 Aug;263(2 Pt 2):H399–H404. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.2.H399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatsuka H., Sekiguchi N., Sato K., Akai K., Wang Y., Komaru T., Ashikawa K., Takishima T. Microvascular sites and mechanisms responsible for reactive hyperemia in the coronary circulation of the beating canine heart. Circ Res. 1992 Oct;71(4):912–922. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.4.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusachi S., Thompson R. D., Olsson R. A. Ligand selectivity of dog coronary adenosine receptor resembles that of adenylate cyclase stimulatory (Ra) receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1983 Nov;227(2):316–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxson D. D., Homans D. C., Bache R. J. Inhibition of adenosine-mediated coronary vasodilation exacerbates myocardial ischemia during exercise. Am J Physiol. 1993 Nov;265(5 Pt 2):H1471–H1477. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.5.H1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie J. E., Steffen R. P., Haddy F. J. Relationships between adenosine and coronary resistance in conscious exercising dogs. Am J Physiol. 1982 Jan;242(1):H24–H29. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.242.1.H24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols C. G., Lederer W. J. Adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol. 1991 Dec;261(6 Pt 2):H1675–H1686. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.6.H1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves R. B., Park J. S., Lapennas G. N., Olszowka A. J. Oxygen affinity and Bohr coefficients of dog blood. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1982 Jul;53(1):87–95. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.53.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozek R. J., Kuo T. H., Giacomelli F., Wiener J. Proteolytic activities in hypertensive cardiomyopathy of rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1983 Mar;15(3):173–187. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(83)90297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito D., Steinhart C. R., Nixon D. G., Olsson R. A. Intracoronary adenosine deaminase reduces canine myocardial reactive hyperemia. Circ Res. 1981 Dec;49(6):1262–1267. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.6.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaha F. F., Heineman F. W., Ince C., Fleming J., Balaban R. S. ATP-sensitive potassium channel is essential to maintain basal coronary vascular tone in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1992 May;262(5 Pt 1):C1220–C1227. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.5.C1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schütz W., Zimpfer M., Raberger G. Effect of aminophylline on coronary reactive hyperaemia following brief and long occlusion periods. Cardiovasc Res. 1977 Nov;11(6):507–511. doi: 10.1093/cvr/11.6.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver P. J., Walus K., DiSalvo J. Adenosine-mediated relaxation and activation of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in coronary arterial smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984 Feb;228(2):342–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkinson W. P., Foley D. H., Rubio R., Berne R. M. Myocardial adenosine formation with increased cardiac performance in the dog. Am J Physiol. 1979 Jan;236(1):H13–H21. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.1.H13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]