Abstract

The exact molecular mechanisms by which the environmental pollutant arsenic works in biological systems are not completely understood. Using an unbiased chemogenomics approach in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, we found that mutants of the chaperonin complex TRiC and the functionally related prefoldin complex are all hypersensitive to arsenic compared to a wild-type strain. In contrast, mutants with impaired ribosome functions were highly arsenic resistant. These observations led us to hypothesize that arsenic might inhibit TRiC function, required for folding of actin, tubulin, and other proteins postsynthesis. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that arsenic treatment distorted morphology of both actin and microtubule filaments. Moreover, arsenic impaired substrate folding by both bovine and archaeal TRiC complexes in vitro. These results together indicate that TRiC is a conserved target of arsenic inhibition in various biological systems.

ARSENIC is a ubiquitous environmental pollutant that causes severe health problems in humans. It is also used as an effective therapeutic agent against various diseases and infections. Using advanced genomic tools in the model organism yeast and biochemical experiments, we demonstrated that arsenic disturbs functions of the chaperonin complex required for proper folding and maturation of a large number of proteins. This mechanism of action by arsenic is conserved in various biological systems ranging from archaeal bacteria to mammals. Such an understanding should help in exploring possible ways to overcome toxic effects caused by exposure to arsenic.

Trivalent inorganic arsenic is among the most significant environmental hazards affecting the health of millions of people worldwide (Nordstrom 2002). Particularly, inorganic trivalent arsenic [As(III)] in underground drinking water and some mining environments is recognized as the cause of various cancers affecting the skin, lung, urinary tract, bladder, liver, and kidney (Tapio and Grosche 2006), as well as being implicated in several other disorders such as diabetes, hypertension, neuropathy, and vascular diseases (Tseng 2004). Interestingly, As(III) is also an effective therapeutic agent against cancer and human pathogens. A number of models have been proposed to explain the biological effects of As(III), including stimulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (Miller et al. 2002; Tapio and Grosche 2006) and inhibition of tubulin polymerization (Ramirez et al. 1997; Li and Broome 1999). However, exactly how As(III) disturbs biological systems is still not clear.

The eukaryotic chaperonin TRiC (TCP1-ring complex, also called CCT) is a ∼900-kDa complex consisting of two apposed heterooligomeric protein rings. Each ring, constituted by eight homologous subunits (encoded by the essential CCT1–CCT8 genes in budding yeast), contains a central cavity in which unfolded polypeptide substrates attain a properly folded state in an ATP-requiring reaction (Bukau and Horwich 1998; Gutsche et al. 1999). TRiC is required for the proper folding of an important subset of cytosolic proteins, including cytoskeleton components, cell cycle regulators, and tumor suppressor proteins (Spiess et al. 2004). Some of these protein substrates are themselves encoded by essential genes; thus TRiC is indispensable for eukaryotic cell survival. Many TRiC substrates are subunits of oligomeric complexes and their assembly into functional multisubunit complexes also requires TRiC (Spiess et al. 2004). Assembly of such macromolecular complexes in some cases eliminates the accumulation of toxic subunits such as free β-tubulin molecules, which can bind to γ-tubulin and thereby disrupt the formation of mitotic spindles in the yeast S. cerevisiae (Archer et al. 1995). Folding of yeast actin, α-tubulin, and β-tubulin and their oligomerization require TRiC and GimC (also known as prefoldin), a nonessential protein complex of six distinct but structurally related subunits of 13–23 kDa (Geiser et al. 1997; Vainberg et al. 1998). Mutational loss of GimC function substantially reduces actin and tubulin folding efficiency although it does not cause obvious growth defects in yeast. However, deletion of various GimC subunits strongly reduces the viability of conditional-lethal alleles of TRiC subunits under permissive conditions (Siegers et al. 1999).

To elucidate the mechanisms of inorganic As(III)'s action(s) in a eukaryotic system, we first took an unbiased functional chemogenomics approach in yeast to systematically probe for the genetic determinants of arsenic sensitivity. These genetic and subsequent biochemical results point to the conclusion that As(III) inhibits the yeast TRiC complex. This mechanism of action is apparently conserved because the activities of both a mammalian TRiC complex and an archaeal TRiC-like chaperonin are significantly inhibited by arsenic in vitro. Given that mammalian TRiC and some of its substrates are implicated in tumor suppression, angiogenesis, and neuropathy (Lee et al. 2003; Spiess et al. 2004; Bouhouche et al. 2006), TRiC is likely an important protein mediator of As(III)'s effects on human health.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Profiling of the sensitivity of genome-wide deletion mutants to arsenic and individual validation were carried out as described in supporting information, File S1. As2O3 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was first dissolved in NaOH as a 400-mm stock solution of sodium arsenite.

Yeast strains and plasmids:

Individual yeast deletion mutant strains used in this study were all obtained or derived from the yeast knockout mutants constructed by the Saccharomyces Genome Deletion Project (Giaever et al. 1999). The DAmP alleles of TUB2, CCT1, and CCT2 were obtained from Open Biosystems (Breslow et al. 2008). The Cdc55p-3HA expression strain was a gift from Katja Siegers. Plasmids expressing ACT1 and TUB2 from a centromere-based plasmid were constructed by in vivo homologous recombination into YCplac33 (CEN andURA3) (Gietz and Sugino 1988). The CCT1–CCT7,TUB1, and TUB3 overexpression plasmids were similarly constructed into YEplac195 (2 μ, URA3) (Gietz and Sugino 1988). Either YCplac33 or YEplac195 was used as the vector control.

Immunofluorescence:

A 100-ml culture of the wild-type diploid yeast BY4743a/α was grown in YPD at 30° until mid-log phase and split. Sodium arsenite was added into one part of the culture at a final concentration of 1 mm. The other part served as a nontreatment control. Both were incubated at 30° for 3 additional hr. Immunofluorescence analyses of actin and microtubule morphology were performed as previously described (Rieder et al. 1996). Actin was stained with rhodamine-phalloidin and microtubule with an anti-α–tubulin antibody.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting:

The yeast strain expressing Cdc55p–3HA was grown in 100 ml YPD at 30° until mid-log phase. The culture was split and sodium arsenite was added into one aliquot at a final concentration of 1 mm. The other aliquot served as a nontreatment control. Both were subsequently incubated at 30° for 1 hr before cells were harvested. Cell homogenization and immunoprecipitation were carried out essentially as described (Pan and Heitman 2002). An anti HA and anti-actin antibody were used to immunoprecipitate Cdc55p–3HA and actin, respectively. Cdc55p–3HA, actin and TRiC on the Western blots were detected with anti-HA, anti-actin, and anti-Cct5p antibodies.

In vitro actin folding assay:

The actin-folding assay was carried out as described by Frydman and Hartl (1996). Briefly, 0.25 μm TRiC was incubated in buffer A [20 mm Hepes-KOH (pH 7.5), 100 mm KOAc, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, 10% glycerol, and 1% PEG 8000]. Subsequently [35S]-actin, which was denatured in 6 m guanidine/HCl, was rapidly diluted 1:100 to a final concentration of 30 μm into the reaction mix. After incubation for 10 min at 4° and centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 min to remove aggregated actin, the reaction was supplemented with 1 mm ATP and incubated for 40 min at 30° to allow time for ATP-dependent actin refolding by the chaperonin. A total of 1 mm arsenite was added as indicated in the figure. Generation of native [35S]-actin was determined by native gel electrophoresis using folded [35S]-actin as a control as described previously (Frydman and Hartl 1996). The gel was exposed on a phosphor storage screen (Kodak) and scanned in a Typhoon 9410 imager (GE Healthcare).

Archaeal chaperonin folding assays:

Purification of the archaeal chaperonin from Mm-Cpn was carried out by conventional chromatography essentially as described (Kusmierczyk and Martin 2003). Rhodanese folding by the archaeal chaperonin Mm-Cpn was assayed as described (Weber and Hayer-Hartl 2000). In brief, 0.25 μm protein was incubated in Cpn-buffer supplemented with 20 mm sodium thiosulfate. Purified rhodanese was denatured in 6 m guanidinium/HCl containing 5 mm DTT and rapidly diluted 1:100 to a final concentration of 30 μm into the reaction mix. After incubation for 5 min at 37°, the reaction was started by addition of 2 mm ATP and allowed to proceed for 50 min at 37°. To detect the presence of refolded rhodanese, 10 μl of the reaction was withdrawn and applied to a rhodanese activity assay performed as described (Weber and Hayer-Hartl 2000).

RESULTS

Mutants of the chaperonin pathway are As(III) hypersensitive:

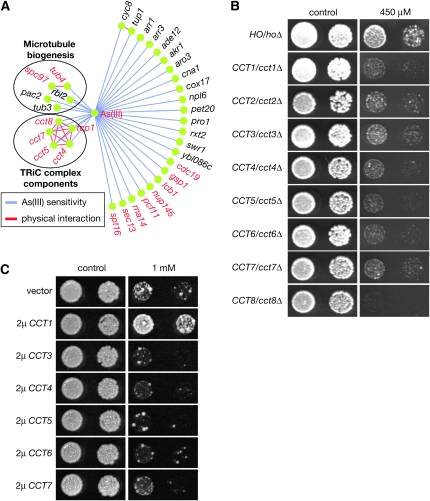

Haploinsufficiency of a target gene could lead to increased sensitivity to the cognate antiproliferation cytotoxin or drug (Giaever et al. 1999; Lum et al. 2004). To probe molecular mechanisms of As(III) actions in yeast, we investigated As(III) sensitivity of genome-wide heterozygous diploid yeast knockout (YKO) mutants using a TAG array-based analysis (Giaever et al. 1999; Lum et al. 2004) followed by individual validation. We found that 33 heterozygous diploid YKOs were significantly more sensitive than an isogenic wild-type strain to 450 μm sodium arsenite (Figure 1A and Table S1). Because As(III) completely inhibits yeast cell growth at higher concentrations, we reasoned that it might inactivate at least one essential protein or protein complex. A total of 15 of these 33 As(III)-hypersensitive mutants were heterozygous for essential genes, including five (CCT1, CCT4, CCT5, CCT7, and CCT8) encoding subunits of the TRiC complex and two more (SPC97 and TUB4) that are directly involved in microtubule biogenesis and function (Figure 1A and Table S1). We directly tested three other heterozygous YKOs (CCT2, CCT3, and CCT6) of TRiC that were missed in the initial array-based screen due to low microarray hybridization signal intensities and found that they were also more sensitive to As(III) than a control strain (Figure 1B). Yeast cells overexpressing one of the TRiC complex genes, CCT1, were also partially arsenic resistant on solid medium (Figure 1C). Such an effect was also observed in liquid culture. Under unperturbed conditions, the growth rates of hoΔ mutants carrying an empty vector and overexpressing TCC1 in a liquid synthetic medium were at 113 min/division and 115 min/division, respectively. In the presence of 450 μm of As(III), their growth rates were 181 min/division and 137 min/division, respectively. These results together suggest that As(III) might inhibit TRiC complex function.

Figure 1.—

Genetic alterations in the TRiC complex affect arsenic susceptibility. (A) As(III)-sensitive heterozygous diploid YKOs identified by genome-wide mutant fitness profiling. Essential genes are colored in red and nonessential genes in black. The network diagram was created with Cytoscape 2.0 (Shannon et al. 2003). (B) Sensitivity of the heterozygous diploid YKOs of all eight TRiC subunits to As(III) at 450 μm. An ho/hoΔ mutant phenotypically indistinguishable from a wild-type yeast served as the control strain. (C) An hoΔ mutant harboring a vector or a plasmid overexpressing a TRiC subunit as indicated was tested for growth on solid SC −Ura that either contained or lacked 1 mm As(III).

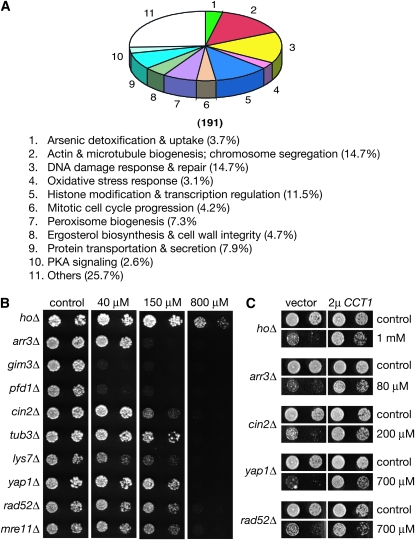

Synthetic lethality interactions were previously observed between CCT1 partial loss-of-function alleles and deletion mutations of the GimC complex, which acts as a cochaperone in TRiC-mediated actin and tubulin folding (Siegers et al. 1999). Thus, if As(III) inhibits TRiC, GimC deletion mutants should be arsenic hypersensitive. To test this prediction and to further extend the study of cellular response to As(III), we systematically investigated genome-wide haploid YKOs for As(III) sensitivity using dSLAM, a barcode microarray-based method for detecting gene-compound and gene–gene interactions (Pan et al. 2004). Upon individual validation, we found that 191 haploid YKOs were sensitive to As(III) at 400 μm or lower (Figure 2A and Table S2). The nine most sensitive ones directly affected either As(III) efflux (arr1Δ and arr3Δ) or the GimC complex (gim3Δ, gim4Δ, gim5Δ, pac10Δ, pfd1Δ, yke2Δ, and yml094c-aΔ, which deletes part of GIM5) (data not shown) and all GimC mutants were more sensitive than the ARR mutants when tested at 40 μm As(III) (Figure 2B and data not shown), further supporting the model that arsenic inhibits TRiC.

Figure 2.—

Arsenic-sensitive haploid YKOs and their genetic relationships with CCT1. (A) As(III)-sensitive haploid deletion mutants identified by genome-wide mutant fitness profiling. A total of 191 were individually verified to be sensitive to As(III) at 400 μm. The number of mutants in each biological process affected and the corresponding percentage among all mutations identified were listed. This plot was derived from Table S2. (B) Growth of representative arsenic-sensitive haploid YKOs of indicated genotypes on a solid synthetic complete (SC) medium that either lacked or contained As(III) at 40 μm, 150 μm, and 800 μm. (C) Partial suppression of the arsenic sensitivity by CCT1 overexpression in various mutants.

Most other As(III)-sensitive mutants were susceptible only to relatively high concentrations (Table S2). These included additional mutants affecting actin and microtubule biogenesis and those affecting peroxisome biogenesis, mitotic chromosome segregation, cell cycle progression, histone modification, ergosterol biosynthesis, oxidative stress response, DNA repair, and others (Figure 2A and Table S2), consistent with results of recently performed screens using the haploid or homozygous diploid knockout mutants (Dilda et al. 2008; Jin et al. 2008; Thorsen et al. 2009). That mutants defective in oxidative stress response and DNA repair were sensitive to As(III) also agrees with a previous finding that As(III) stimulates the production of ROS (Tapio and Grosche 2006), which damage DNA molecules. The arsenic-sensitive phenotypes of some of these other mutants are likely related to TRiC inhibition because CCT1 overexpression partially suppressed arsenic sensitivity in various mutants, including those of oxidative stress response and DNA repair (Figure 2C). Some of the affected pathways are likely required for buffering the effects of arsenic inhibition of TRiC. Others might well reflect additional independent bona fide arsenic targets in yeast.

Slowed protein synthesis confers As(III) resistance:

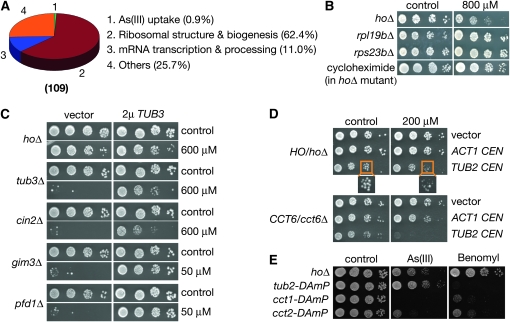

We also identified 109 arsenic-resistant haploid YKOs and about 62.4% of them affected either ribosomal protein genes or those involved in ribosomal biogenesis (Figure 3A and Table S3). A similar connection between mutations in ribosomal biogenesis and arsenic resistance was also recently observed by others (Dilda et al. 2008). Although ribosomal proteins are essential, some are encoded by duplicated genes in yeast and deleting one copy is nonlethal. Interestingly, arsenic resistance of the ribosomal protein mutants largely correlated with their fitness defects under normal conditions (data not shown). We suspected that these mutants might have compromised capacity in protein synthesis, which leads to As(III) resistance. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the effects of inhibiting protein synthesis with a sublethal concentration of cycloheximide. Similar to the rpl19bΔ and rps23bΔ mutations that affect ribosomal protein genes, treatment with cycloheximide conferred yeast cells resistance to As(III) (Figure 3B). This relationship between protein synthesis and arsenic cytotoxicity is consistent with the model that As(III) inhibits TRiC, which facilitates the folding of newly synthesized polypeptides and their subsequent assembly into oligomeric complexes (Spiess et al. 2004). Inhibition of TRiC by As(III) likely has two distinct types of effects: (1) production of insufficient quantities of correctly folded substrates and assembled complexes that are essential for viability and (2) accumulation of incorrectly folded substrates or unassembled subunits that are toxic.

Figure 3.—

The rate of protein synthesis and free β-tubulin modulate yeast arsenic sensitivity. (A) The distribution of arsenic-resistant haploid YKOs according to biological processes affected. This plot was derived from Table S3. (B) Cells of indicated genotypes were grown in an SC medium that either contained or lacked 800 μm of As(III). Cycloheximide was used at 10 ng/ml. (C) One of the α-tubulin genes TUB3 was overexpressed from a 2μ plasmid in mutants defective in microtubule biogenesis. Cells were grown on solid SC −Ura either in the presence or absence of As(III). As(III) concentration used was 600 μm for the hoΔ, tub3Δ, and cin2Δ mutants and 50 μm for the gim3Δ and pfd1Δ mutants. (D) The β-tubulin gene TUB2 and the actin gene ACT1 were expressed in mutants of indicated genotypes from a centromere-based plasmid. Cells were grown on solid SC that lacked uracil (SC −Ura) either in the presence or absence of 200 μm of As(III). (E) Strains of indicated genotypes were grown on solid YPD with or without As(III) (1 mm) or benomyl (20 μg/ml).

β-Tubulin contributes to As(III) toxicity:

One such TRiC substrate is β-tubulin, which causes growth defects in yeast cells when overexpressed and not dimerized with α-tubulin (Archer et al. 1995). Presumably, β-tubulin polypeptides produced at lower rates (resulting from slowed protein translation) in ribosomal protein mutants or cycloheximide-treated cells were more compatible with the capacity of arsenic-crippled TRiC complex. As a result, unfolded polypeptides and/or unassembled toxic free β-tubulin molecules might have been accumulated at lower levels, mitigating As(III) toxicity. To test this hypothesis, we investigated whether β-tubulin contributes to As(III) toxicity by genetically perturbing the relative ratio between α- and β-tubulins. We first modestly overexpressed TUB2 (the β-tubulin gene) from a centromeric plasmid under control of its endogenous promoter and tested its effects on the growth and arsenic sensitivity of HO/hoΔ (a surrogate wild type) and CCT6/cct6Δ heterozygous diploid mutants. Modest overexpression of TUB2 made the HO/hoΔ mutant slightly yet reproducibly more sensitive to As(III) (Figure 3D). It also noticeably hampered growth of the CCT6/cct6Δ mutant in the absence of As(III) and even more so in its presence (Figure 3D). In comparison, modest overexpression of ACT1, which encodes another important cytoskeletal substrate of TRiC, actin, had no effect (Figure 3C). In agreement with these results, deleting TUB3, a nonessential gene encoding α-tubulin, caused As(III) hypersensitivity (Figures 2B and 3C). Overexpression of TUB3 from a high copy plasmid also suppressed As(III) toxicity in cin2Δ, gim3Δ, and pfd1Δ mutants (Figure 3C), which are defective in tubulin folding and dimerization. Similar results were observed when TUB1, an essential α-tubulin gene highly homologous to TUB3, was overexpressed (data not shown). In these mutants, overexpression of α-tubulin likely allowed more efficient folding and/or incorporation of β-tubulin molecules into nontoxic heterodimers due to the increased abundance of available α-tubulin molecules. These results together indicated that yeast cells with a relatively high β/α-tubulin ratio are sensitized to As(III) and those with a low β/α-tubulin ratio are more resistant to the drug. Thus unfolded and/or folded yet free β-tubulin molecules apparently contribute to As(III) cytotoxicity.

Arsenic unlikely directly inhibits microtubule function in yeast:

It has been proposed that As(III) directly binds to tubulins and disrupts their functions in mammalian cells (Li and Broome 1999). In particular, As(III) was shown to directly bind to β-tubulin isolated from a human breast cancer cell line and structural modeling suggested the amino acid residue Cys12 is key to such a physical interaction (Zhang et al. 2007). This model of arsenic action would be consistent with most of the genetic evidence described above. However, it is not consistent with other genetic evidence. We found that a tub2–DAmP mutant (Breslow et al. 2008), which presumably expresses TUB2 at a lower level as compare to a wild type due to mRNA instability, responds to As(III) and the well-known microtubule poison benomyl very differently. Consistent with the idea that benomyl directly binds to and inihibits microtubules, the tub2–DAmP was hypersensitive to this drug (Figure 3E). The latter result also implies that TUB2 expression is indeed reduced in the DAmP allele. In contrast to the hypothesis that As(III) directly affects microtubules, the tub2–DAmP strain was slightly more resistant to As(III) than the wild type (Figure 3E), a highly reproducible phenotype. A TUB2/tub2Δ heterozygous diploid mutant was similarly hypersensitive to benomyl but slightly more resistant to As(III) as compared to a HO/hoΔ control strain (data not shown). In contrast to the tub2–DAmP mutant, both the cct1–DAmP and cct2–DAmP mutants were hypersensitive to both As(III) and benomyl. These results suggest that As(III) unlikely inhibit yeast growth by binding to microbutules as benomyl does. Of course, it is still possible that arsenic binds to yeast microtubules but has a different effect than benomyl. However, the Cys12 residue critical for arsenic binding to human β-tubulin is not conserved in its yeast ortholog. The genetic results are also more consistent with the model that As(III) inhibits the TRiC complex, which is required to compensate for the loss of microtubule functions in the presence of benomyl due to its essential functions in microtubule biogenesis (Ursic et al. 1994;Siegers et al. 2003).

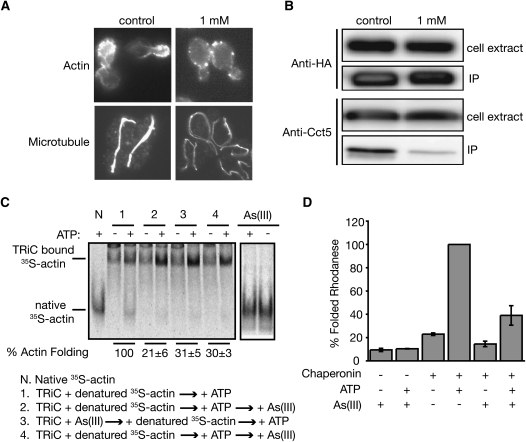

Arsenic affects TRiC function in vivo:

Defects in TRiC were previously shown to distort morphological organization of both actin and microtubule filaments (Ursic et al. 1994; Siegers et al. 2003). If As(III) inhibits TRiC, we expected that arsenic treatment of wild-type yeast cells would have similar effects, and this was exactly what we observed. Actin filaments are typically polarized to emerging buds under normal conditions (Figure 4A) (Adams and Pringle 1984; Kilmartin and Adams 1984). In the presence of As(III), such polarization disappeared (Figure 4A). Arsenic treatment also distorted the mitotic microtubule structures (Figure 4A). Similar observations were recently made in another study (Jin et al. 2008), although the exact microtubule morphology change caused by arsenic treatment shown there was different from what we saw. Such difference was likely caused by different experimental protocols. In this other study, the intrinsic fluorescence of GFP tagged α-tubulin was observed, whereas we used immunostaining. Despite this, the fact that arsenic treatment affects the morphology of both actin and microtubule filaments strongly support the model that As(III) inhibits TRiC functions in vivo.

Figure 4.—

As(III) inhibits TRiC functions. (A) Wild-type yeast (BY4743) cells were grown in liquid YPD either in the absence or presence of 1 mm of As(III) for 3 hr. Actin was stained with rhodamine-phalloidin and microtubules were visualized with an anti-α–tubulin antibody. (B) ATP-depleted cell lysates prepared from yeast cells expressing Cdc55–3HA grown in liquid YPD that either contained or lacked 1 mm As(III) were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody. Western blots of the total cell extracts (5μg) and the immunoprecipitates (IP) from lysates containing 200 μg total protein were analyzed with an anti-HA antibody and an antibody against one of the TRiC subunits Cct5. (C) In vitro binding and folding of denatured [35S]-actin by bovine TRiC both in the presence and absence of 1 mm As(III) were assessed by native gel analysis followed by autoradiography. Three (2, 3, and 4) different schemes of arsenic treatment were tested. Native [35S]-actin samples incubated with or without As(III) were included as controls (right two lanes). The extent of As(III) inhibition in each condition was quantified for three independent experiments and expressed as percentage of actin folding relative to the untreated control. (D) In vitro rhodanese folding by the M. maripaludis TRiC-like chaperonin (Mm-Cpn) was assessed in the presence and absence of 1 mm sodium arsenite as described (Kusmierczyk and Martin 2003).

We next investigated whether As(III) might interfere with the physical interaction between TRiC and its substrates. In addition to the major substrates actin and tubulins, TRiC is required for folding of cytoplasmic proteins such as Cdc55p in yeast (Siegers et al. 2003). We found that As(III) reproducibly and significantly reduced physical interaction between TRiC and Cdc55p in coimmunoprecipitation assays (Figure 4B), further indicating that As(III) directly affects TRiC functions. However, arsenic had no effect on the physical interaction between TRiC and β-tubulin (data not shown) and its effect on the interaction between TRiC and actin was inconclusive. Out of three independent coimmunoprecipitation experiments, we found that As(III) partially reduced TRiC binding to actin in one experiment and did not see any effect in the other two (data not shown). Thus, As(III) inhibits TRiC binding to some substrates (i.e., Cdc55p) but not to others in vivo (β-tubulin).

Arsenic inhibits TRiC activity in vitro:

Eukaryotic pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), which consumes pyruvate to form acetyl-CoA while reducing NAD+ to NADH, has long been considered a primary target for arsenic (Schiller et al. 1977). A possible consequence of arsenic inhibition of PDH is disruption of energy production and lowered intracellular ATP/ADP ratio. TRiC folding of substrates absolutely requires ATP hydrolysis (Spiess et al. 2004) and As(III) might inhibit TRiC function indirectly by inactivating PDH and thereby damping intracellular ATP concentration. However, we consider this unlikely because PDH is nonessential in yeast. In addition, we did not observe a synthetic lethality or slow growth interaction between a PDH (pda1Δ) mutation and a GimC mutation (pfd1Δ) (data not shown).

We next tested the possibility that As(III) directly inactivates TRiC using a well-characterized in vitro assay that monitors the ability of purified chaperonin to fold chemically denatured 35S-actin (Meyer et al. 2003). We found that addition of 1 mm As(III) to a folding reaction using purified bovine TRiC significantly inhibited actin folding. Such inhibition was observed both when the inhibitor was added before and shortly after substrate binding to TRiC. Here binding of TRiC to actin was not inhibited by As(III) (Figure 4C). Yet actin folding activity was still inhibited, suggesting that As(III) inactivates TRiC after substrate binding. Similarly, As(III) inhibited substrate folding by a TRiC-like archaeal complex, the Mm-Cpn chaperonin from Methanococcus maripaludis, which is ∼40% identical to its human counterpart (Figure 4D). Together, these results support the idea that As(III) directly inhibits the folding activity of TRiC and TRiC-like chaperones.

We also found that inhibition of TRiC by arsenic in vitro was reversible because its activity was recovered after gel filtration (data not shown), ruling out direct covalent modification of TRiC by As(III) as a mechanism of action. Such reversibility was also observed with arsenic inhibition of yeast growth; nearly 100% of yeast cells regained colony formation capacity after being incubated in the presence of inhibitory concentration of the drug (>2 mm) for over 24 hr at 30° (data not shown).

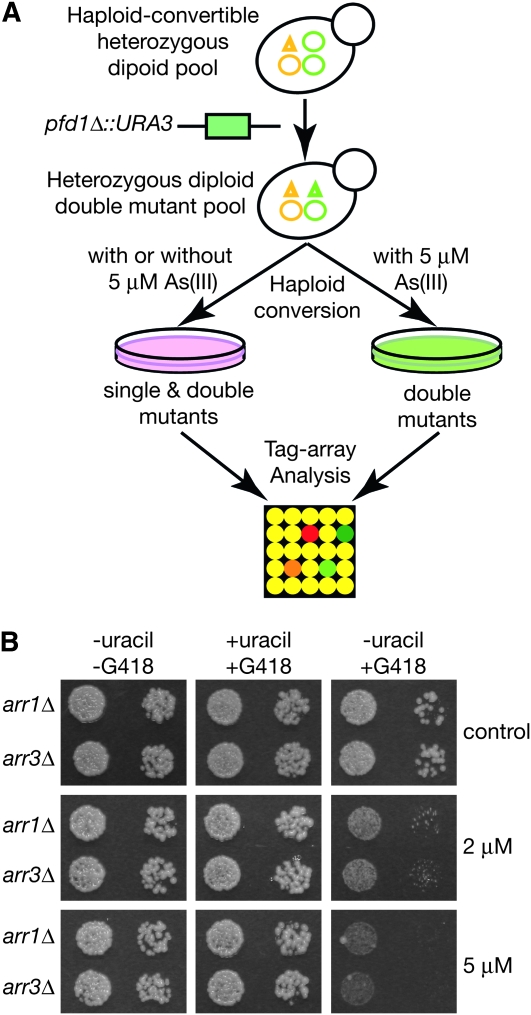

Detoxification mutations sensitize TRiC defective cells toward As(III):

Arsenic concentrations required for inhibiting growth of wild-type yeast cells are much higher than needed for arsenic chemotherapy and toxicity in human cells. To mitigate such difference, we next investigated whether arsenic inhibition of TRiC at clinically achievable doses could inhibit growth of relatively healthy yeast cells. To do this, we first performed a genome-wide synthetic As(III)-hypersensitivity screen to identify secondary mutations that further sensitize a pfd1Δ mutant, which does not have obvious growth defect on its own but does exhibit partial defect in TRiC-mediated actin and tubulin folding (Geiser et al. 1997; Vainberg et al. 1998), to 5 μm of As(III) (Figure 5A). We identified and individually confirmed a large number of such mutations (Table S4). Among them, both arr1Δ and arr3Δ rendered the pfd1Δ mutant highly sensitive to 5 μm of As(III) without affecting its growth rate under normal conditions (Figure 5B and Table S4). Growth of the arr1Δ pfd1Δ and arr3Δ pfd1Δ double mutants was also significantly inhibited by a lower concentration of arsenic (2 μm) (Figure 5B). Thus, at clinically effective doses, arsenic inactivation of TRiC indeed significantly inhibited the growth of otherwise healthy yeast cells. These results indicate that, at the mechanistic level, arsenic modes of actions may well be the same in both yeast and human, even though the wild-type yeast cells seem to be more resistant to As(III) than human cells. Interestingly, Arr1p is a transcription factor required for expression of Arr3p, an arsenite transporter that actively pumps the drug out of yeast cells (Ghosh et al. 1999). Mammalian genomes do not seem to encode an Arr3p-like arsenic transporter, the absence of which might allow for more effective accumulation of intracellular As(III).

Figure 5.—

A genome-wide screen identifies double mutants hypersensitive to low concentrations of arsenic. (A) A high-efficiency pfd1Δ∷URA3 gene disruption cassette was transformed into a pool of haploid-convertible heterozygous diploid yeast knockout mutants. After sporulation, a pool of haploid double knockout mutants were derived from the heterozygous diploid double mutant pool in the presence of 5 μm of As(III). A separate pool of haploid single and double mutants were also similarly derived either in the presence or absence of 5 μm of As(III). Relative representation of each knockout mutation in both pools was compared by TAG-array analysis (Pan et al. 2004). (B) Haploid-convertible ARR1/arr1Δ∷kanMX PFD1/pfd1Δ∷URA3 and ARR3/arr3Δ∷kanMX PFD1/pfd1Δ∷URA3 diploid double mutants were sporulated and spotted on a haploid selection medium that either lacked both uracil and G418 (to select for Ura+ single and double mutants), contained both uracil and G418 (to select for G418-resistant single and double mutants), or lacked uracil but contained G418 (to select for the double mutants). Cell growth under each condition was assessed both in the absence (control) and presence of 2 μm or 5 μm of As(III) and photographed.

DISCUSSION

By using a combination of functional genomic, genetic, and biochemical studies, we have investigated the genetic determinants of arsenic susceptibility in yeast and elucidated a mechanism of action by arsenic common to both eukaryotes and archaea. Our data suggest that arsenic inhibits the function(s) of the chaperonin complex. Similar functional genomic studies have been recently reported (Dilda et al. 2008; Jin et al. 2008; Thorsen et al. 2009). Although there was considerable overlap among all of these studies regarding the lists of arsenic-sensitive and -resistant mutants identified, our study is distinctly different from these others, which studied only the haploid and/or homozygous diploid knockout mutant libraries that lack mutants of essential genes. In contrast, we first studied the genome-wide heterozygous diploid mutants, which directly and dramatically revealed the essential TRiC complex as a candidate target of As(III) via drug-induced haploinsufficiency. We subsequently corroborated this finding by identifying As(III)-hypersensitive and -resistant haploid mutants. In particular, we have put an emphasis on the most sensitive haploid knockout mutant(s) with the premise that it likely affects functions most closely related to the arsenic target(s). That all 6 mutants of the GimC complex exhibited the highest sensitivity toward low concentrations of As(III) (Figure 2B and Table S2) further supported the idea that TRiC is the target. More importantly, we provided further evidence that As(III) inhibits TRiC functions both in vivo and in vitro. Such a conclusion is also consistent with a previous observation made in mouse Swiss 3T3 cells that treatment with 30 μm of arsenic leads to distorted organization of both actin and microtubule filaments (Li and Chou 1992). Lastly, with subtle modification of the previously described dSLAM methodology (Pan et al. 2004), we also demonstrated that it is possible to systematically identify genome-wide double mutations that confer hypersensitivity to a given drug in a high throughput manner. This will allow for expansion in the elucidation of genetic interaction networks involved in drug response to beyond monogenic traits.

Despite that As(III) concentrations used in most of our experiments were relatively high, our results are likely relevant to arsenic effects on human health. First, our results with the apparently healthy arr1Δ pfd1Δ and arr3Δ pfd1Δ double mutants (Figure 5B) have demonstrated that low concentrations of arsenic can inhibit cell growth in yeast. That human cells are more susceptible might also be due to stress-induced apoptosis that is basically lacking in yeast cells. Second, both yeast and human cells accumulate high levels of arsenic after exposure to low concentrations and this is more obvious in human cells than in yeast. It was shown that ∼106 wild-type yeast cells exposed to 160 μm of arsenic for 2 hr accumulate ∼0.163 nmol of the drug (Dilda et al. 2008), equivalent to a final intracellular concentration of ∼2.3 mm, assuming an average volume of a haploid yeast cell of ∼70 fl (Sherman 2002). Similarly, ∼106 human APL cells (NB4) exposed to 20 μm of arsenic for 4 hr accumulated ∼0.73 nmol of the drug (Dilda et al. 2008), equivalent to an intracellular concentration of ∼0.7 mm, assuming an average volume of of ∼1040 fl for an NB4 cell (Miossec-Bartoli et al. 1999). As(III) concentrations within cells of certain human organs and tissues or within some intracellular compartments might be even higher. Thus our observation of TRiC inhibition by 1 mm of As(III) in vitro could be relevant in vivo even when mammalian cells are exposed to relatively low levels of As(III). Third, our in vitro assays might have underdetected the potency of arsenic inhibition of TRiC. In the protein-folding assays, we had to include 1 mm of DTT, which is absolutely required for substrate folding by TRiC and Mm-Cpn (J. Frydman, unpublished observations). The presence of DTT in the folding assays likely at least partially reversed the inhibitory effects of arsenic on TRiC and Mm-Cpn. Unfortunately, we could not test the effects of lower concentrations of As(III) on TRiC activities due to this technical limitation of the assay.

Among the heavy metals that interact with thiol groups, As(III) inhibition of TRiC seems to be specific. One piece of supporting evidence is that mutants of the prefoldin complexes, which are hypersensitive to As(III), did not exhibit sensitivity toward Cd2+ when compared to a wild-type strain (data not shown). However, currently it is not clear how As(III) inhibits the TRiC complex at the biochemical level. It did not seem to inhibit TRiC's substrate binding (Figure 4C) or its ATPase activity. In fact, arsenic stimulated the ATPase activity of TRiC by approximately twofold (data not shown). Given the similar inhibitory effects observed when As(III) was added both before and shortly after substrate binding (Figure 4C), it is possible that it blocks a late step of the process, for example, release of correctly folded products from the chaperonin complex. This might gradually lead to accumulation of unproductive TRiC complex and reduction in its overall productivity. This might partly explain why arsenic reproducibly inhibits TRiC binding to Cdc55 but not actin and tubulin. Possibly, most TRiC molecules within arsenic-treated cells are stuck with the more abundant substrates such as actin and tubulin.

That TRiC is required for folding and maturation of as much as ∼9–15% of all cytosolic proteins in mammals (Thulasiraman et al. 1999) might also at least partly explain the pleiotropic effects of arsenic on human health. For example, exposure to arsenic has been linked to cancers and neuropathy. The former might be related to the fact that TRiC is required for the assembly of the Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor complex (Feldman et al. 1999), which plays a positive role in stabilizing and activating p53 (Roe et al. 2006), a major tumor suppressor commonly mutated in various human cancers. Arsenic inhibition of TRiC might thus indirectly downregulate p53 activity and cause cancers, a model consistent with the observation that arsenic inhibits p53 activation in response to DNA damage (Tang et al. 2006). In addition, mutating TRiC subunit genes CCT5 and CCT4 are directly implicated in sensory neuropathy in both human patients and in a rat model (Lee et al. 2003;Bouhouche et al. 2006).

Acknowledgments

We thank Katja Siegers for providing the anti-Cct5p antibody and a yeast strain that expresses Cdc55p–3HA (Siegers et al. 2003). We are also grateful to David Drubin and Andy Hoyt for anti-α–tubulin antibodies and Pamela Meluh for an anti-β–tubulin antibody. We thank Robert Cohen and Pamela Meluh for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants HG02432 and RR020839 to J.D.B, by NIH grant HG004840 to X.P., by NIH grant RR019409 to J.M.M., and by NIH grant GM74074 and a grant from the NIH Roadmap Initiative on Nanomedicine to J.F.

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.110.117655/DC1.

The microarray data were submitted to GEO (accession no. GSE5973).

References

- Adams, A. E., and J. R. Pringle, 1984. Relationship of actin and tubulin distribution to bud growth in wild-type and morphogenetic-mutant Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 98 934–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer, J. E., L. R. Vega and F. Solomon, 1995. Rbl2p, a yeast protein that binds to beta-tubulin and participates in microtubule function in vivo. Cell 82 425–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhouche, A., A. Benomar, N. Bouslam, T. Chkili and M. Yahyaoui, 2006. Mutation in the epsilon subunit of the cytosolic chaperonin-containing t-complex peptide-1 (Cct5) gene causes autosomal recessive mutilating sensory neuropathy with spastic paraplegia. J. Med. Genet. 43 441–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow, D. K., D. M. Cameron, S. R. Collins, M. Schuldiner, J. Stewart-Ornstein et al., 2008. A comprehensive strategy enabling high-resolution functional analysis of the yeast genome. Nat. Methods 5 711–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau, B., and A. L. Horwich, 1998. The Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperone machines. Cell 92 351–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilda, P. J., G. G. Perrone, A. Philp, R. B. Lock, I. W. Dawes et al., 2008. Insight into the selectivity of arsenic trioxide for acute promyelocytic leukemia cells by characterizing Saccharomyces cerevisiae deletion strains that are sensitive or resistant to the metalloid. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 40 1016–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, D. E., V. Thulasiraman, R. G. Ferreyra and J. Frydman, 1999. Formation of the VHL-elongin BC tumor suppressor complex is mediated by the chaperonin TRiC. Mol. Cell 4 1051–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman, J., and F. U. Hartl, 1996. Principles of chaperone-assisted protein folding: differences between in vitro and in vivo mechanisms. Science 272 1497–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser, J. R., E. J. Schott, T. J. Kingsbury, N. B. Cole, L. J. Totis et al., 1997. Saccharomyces cerevisiae genes required in the absence of the CIN8-encoded spindle motor act in functionally diverse mitotic pathways. Mol. Biol. Cell 8 1035–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, M., J. Shen and B. P. Rosen, 1999. Pathways of As(III) detoxification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 5001–5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaever, G., D. D. Shoemaker, T. W. Jones, H. Liang, E. A. Winzeler et al., 1999. Genomic profiling of drug sensitivities via induced haploinsufficiency. Nat. Genet. 21 278–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz, R. D., and A. Sugino, 1988. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene 74 527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutsche, I., L. O. Essen and W. Baumeister, 1999. Group II chaperonins: new TRiC(k)s and turns of a protein folding machine. J. Mol. Biol. 293 295–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y. H., P. E. Dunlap, S. J. McBride, H. Al-Refai, P. R. Bushel et al., 2008. Global transcriptome and deletome profiles of yeast exposed to transition metals. PLoS Genet. 4 e1000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmartin, J. V., and A. E. Adams, 1984. Structural rearrangements of tubulin and actin during the cell cycle of the yeast Saccharomyces. J. Cell Biol. 98 922–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusmierczyk, A. R., and J. Martin, 2003. Nucleotide-dependent protein folding in the type II chaperonin from the mesophilic archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis. Biochem. J. 371 669–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. J., D. A. Stephenson, M. J. Groves, M. G. Sweeney, M. B. Davis et al., 2003. Hereditary sensory neuropathy is caused by a mutation in the delta subunit of the cytosolic chaperonin-containing t-complex peptide-1 (Cct4) gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12 1917–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, W., and I. N. Chou, 1992. Effects of sodium arsenite on the cytoskeleton and cellular glutathione levels in cultured cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 114 132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. M., and J. D. Broome, 1999. Arsenic targets tubulins to induce apoptosis in myeloid leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 59 776–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum, P. Y., C. D. Armour, S. B. Stepaniants, G. Cavet, M. K. Wolf et al., 2004. Discovering modes of action for therapeutic compounds using a genome-wide screen of yeast heterozygotes. Cell 116 121–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, A. S., J. R. Gillespie, D. Walther, I. S. Millet, S. Doniach et al., 2003. Closing the folding chamber of the eukaryotic chaperonin requires the transition state of ATP hydrolysis. Cell 113 369–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Jr., W. H., H. M. Schipper, J. S. Lee, J. Singer and S. Waxman, 2002. Mechanisms of action of arsenic trioxide. Cancer Res. 62 3893–3903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miossec-Bartoli, C., L. Pilatre, P. Peyron, E. N. N'Diaye, V. Collart-Dutilleul et al., 1999. The new ketolide HMR3647 accumulates in the azurophil granules of human polymorphonuclear cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43 2457–2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom, D. K., 2002. Public health. Worldwide occurrences of arsenic in ground water. Science 296 2143–2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X., and J. Heitman, 2002. Protein kinase A operates a molecular switch that governs yeast pseudohyphal differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 3981–3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X., D. S. Yuan, D. Xiang, X. Wang, S. Sookhai-Mahadeo et al., 2004. A robust toolkit for functional profiling of the yeast genome. Mol. Cell 16 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, P., D. A. Eastmond, J. P. Laclette and P. Ostrosky-Wegman, 1997. Disruption of microtubule assembly and spindle formation as a mechanism for the induction of aneuploid cells by sodium arsenite and vanadium pentoxide. Mutat. Res. 386 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder, S. E., L. M. Banta, K. Kohrer, J. M. McCaffery and S. D. Emr, 1996. Multilamellar endosome-like compartment accumulates in the yeast vps28 vacuolar protein sorting mutant. Mol. Biol. Cell 7 985–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe, J. S., H. Kim, S. M. Lee, S. T. Kim, E. J. Cho et al., 2006. p53 stabilization and transactivation by a von Hippel-Lindau protein. Mol. Cell 22 395–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller, C. M., B. A. Fowler and J. S. Woods, 1977. Effects of arsenic on pyruvate dehydrogenase activation. Environ. Health Perspect. 19 205–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, P., A. Markiel, O. Ozier, N. S. Baliga, J. T. Wang et al., 2003. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13 2498–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, F., 2002. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 350 3–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegers, K., T. Waldmann, M. R. Leroux, K. Grein, A. Shevchenko et al., 1999. Compartmentation of protein folding in vivo: sequestration of non-native polypeptide by the chaperonin-GimC system. EMBO J. 18 75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegers, K., B. Bolter, J. P. Schwarz, U. M. Bottcher, S. Guha et al., 2003. TRiC/CCT cooperates with different upstream chaperones in the folding of distinct protein classes. EMBO J. 22 5230–5240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Spiess, C., A. S. Meyer, S. Reissmann and J. Frydman, 2004. Mechanism of the eukaryotic chaperonin: protein folding in the chamber of secrets. Trends Cell. Biol. 14 598–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, F., G. Liu, Z. He, W. Y. Ma, A. M. Bode et al., 2006. Arsenite inhibits p53 phosphorylation, DNA binding activity, and p53 target gene p21 expression in mouse epidermal JB6 cells. Mol. Carcinog. 45 861–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapio, S., and B. Grosche, 2006. Arsenic in the aetiology of cancer. Mutat. Res. 612 215–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsen, M., G. G. Perrone, E. Kristiansson, M. Traini, T. Ye et al., 2009. Genetic basis of arsenite and cadmium tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Genomics 10 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thulasiraman, V., C. F. Yang and J. Frydman, 1999. In vivo newly translated polypeptides are sequestered in a protected folding environment. EMBO J. 18 85–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, C. H., 2004. The potential biological mechanisms of arsenic-induced diabetes mellitus. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 197 67–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursic, D., J. C. Sedbrook, K. L. Himmel and M. R. Culbertson, 1994. The essential yeast Tcp1 protein affects actin and microtubules. Mol. Biol. Cell 5 1065–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vainberg, I. E., S. A. Lewis, H. Rommelaere, C. Ampe, J. Vandekerckhove et al., 1998. Prefoldin, a chaperone that delivers unfolded proteins to cytosolic chaperonin. Cell 93 863–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber, F., and M. Hayer-Hartl, 2000. Refolding of bovine mitochondrial rhodanese by chaperonins GroEL and GroES. Methods Mol. Biol. 140 117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., F. Yang, J. Y. Shim, K. L. Kirk, D. E. Anderson et al., 2007. Identification of arsenic-binding proteins in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 255 95–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]