Abstract

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the two cryptic mating type loci, HML and HMR, are transcriptionally silent. Previous studies on the establishment of silencing at HMR identified a requirement for passage through S phase. However, the underlying mechanism for this requirement is still unknown. In contrast to HMR, we found that substantial silencing of HML could be established without passage through S phase. To understand this difference, we analyzed several chimeric HM loci and found that promoter strength determined the S phase requirement. To silence a locus with a strong promoter such as the a1/a2 promoter required passage through S phase while HM loci with weaker promoters such as the α1/α2 or TRP1 promoter did not show this requirement. Thus, transcriptional activity counteracts the establishment of silencing but can be overcome by passage through S phase.

EPIGENETIC silencing refers to a transcriptionally inactive state and its heritable transmission. It involves the formation, maintenance, and inheritance of a specialized, constitutively compact chromatin structure, termed heterochromatin. This kind of transcriptional silencing plays an important role in establishing and maintaining distinct patterns of gene expression in genetically identical cells during growth and differentiation. Examples of transcriptional silencing include the inactive mammalian X chromosome, position effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster, and the cryptic mating-type loci in fission and budding yeasts (Rusche et al. 2003; Probst et al. 2009).

In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the MAT locus encodes transcriptional regulatory proteins that are responsible for the differences between the two mating types. HML and HMR harbor cryptic copies of the mating type information genes, α and a, respectively. Transcriptional silencing at these loci relies on cis-regulatory DNA elements called silencers and on a number of trans-acting gene products. Previous studies revealed that establishment of silencing involves a series of protein–DNA and protein–protein interactions (reviewed in Gasser and Cockell 2001; Rusche et al. 2003; Fox and Mcconnell 2005). The silencer elements flanking the HM loci recruit the DNA binding proteins Rap1, Abf1, and ORC, which in turn recruit the silent information regulator (Sir) proteins, Sir1, Sir2, Sir3, and Sir4. A Sir2–Sir3–Sir4 complex spreads from the silencers into nearby nucleosomes (Hoppe et al. 2002; Rusche et al. 2002; Liou et al. 2005; Rudner et al. 2005). This spreading requires Sir2, which deacetylates histone H4 K16, thereby creating a binding site for Sir3 and Sir4 and hence the Sir2/3/4 complex (Carmen et al. 2002; Liou et al. 2005). Multiple rounds of deacetylation by Sir2 allow the Sir complex to spread to adjacent nucleosomes, thus creating a stretch of silent chromatin.

To investigate the establishment of silencing and its relationship to the cell cycle, previous studies utilized conditional or inducible alleles of the Sir proteins to create a transition from Sir− to Sir+ and then examined the establishment of silencing (Miller and Nasmyth 1984; Fox et al. 1997; Kirchmaier and Rine 2001; Li et al. 2001; Lau et al. 2002; Martins-Taylor et al. 2004; Kirchmaier and Rine 2006; Xu et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2008; Osborne et al. 2009). For example, in a classic study, Miller and Nasmyth (1984) used a sir3 temperature-sensitive allele (sir3-8) and shifted cells from a nonpermissive temperature to a permissive temperature to follow the establishment of silencing as functional Sir3 protein became available. This strain contained a-information at both HML and HMR cassettes while MAT was deleted, so that it could be arrested in G1 phase by α-factor at either temperature. Therefore, the establishment of silencing at HML and HMR could not be distinguished in this strain. They tested the establishment of silencing under two conditions, arresting in G1 phase or released for cell-cycle progression. They found that silencing could not be established while the cells were held in G1 phase. Furthermore, they determined that passage through S phase was required for silencing because cells released from an α-factor block and then arrested in G2/M phase were able to silence the HM loci substantially.

It was generally assumed that this S phase requirement was DNA replication. However, a subsequent study in which ORC binding sites were deleted from the HMR silencers found that silencing of the locus still required passage through S phase, suggesting that the S phase requirement was not replication (Fox et al. 1997). This was later demonstrated convincingly by two groups who used modified extrachromosomal copies of an HMR locus whose origins of replication had been deleted and hence could not replicate (Kirchmaier and Rine 2001; Li et al. 2001). They showed that silencing on these plasmids could still occur and thus was independent of DNA replication, but, surprisingly, still required passage through S phase. In a later study, Lau et al. (2002) identified an additional cell-cycle requirement in M phase and suggested it to be the dissolution of sister-chromatid cohesion. They also showed that the two cell-cycle requirements were independent because loss of sister-chromatid cohesion could not bypass the requirement of passage through S phase. Interestingly, the underlying mechanism for the S phase requirement remains unknown.

All the studies described above focused on the HMR locus. A single report previously investigated the S phase requirement at the HML locus and concluded that passage through M phase, but not S phase, was required for establishment of silencing of this locus (Martins-Taylor et al. 2004). But their experimental protocol differed substantially from those used previously to study the S phase requirement at HMR; furthermore, they did not compare the two loci (see discussion). Therefore we decided to compare establishment of silencing of HML and HMR in the same strain under similar conditions. Consistent with the previous observations on HMR, we found that silencing was not established without passage through S phase. However, we found that substantial silencing could be established at the HML locus under the same conditions. To understand this difference, we analyzed the HM loci and attributed the difference to the transcription units of these loci. We then used modified HM loci containing transcription units with different promoter strength and found that transcription counteracted the establishment of silencing: the stronger the promoter, the more stringent the cell-cycle requirement. On the basis of these observations, we propose possible cell-cycle events that may determine the S phase requirement.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and culture conditions:

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Gene replacements were performed as described (Scherer and Davis 1979; Longtine et al. 1998). JRY17 was derived from a cross of RS547 with XRY19, followed by deletion of BAR1 with the S.p.his5+ marker. JRY19 was constructed from JRY17 by gene replacement of sir3Δ∷kanMX6 with sir3-8. JRY25 is a trp1Δ∷kanMX6 version of JRY19. JRY27 was constructed by replacing the wild-type (WT) HML locus with a modified HML locus from plasmid pHML-Pa. This plasmid contains a hybrid HML locus with the α1 gene driven by the promoter from a1/a2 transcription unit. It was generated by overlapping PCR, substituting HML sequences from the Yα segment (Chr III coordinates 12,944–13,244) with HMR sequences from the Ya segment (Chr III coordinates 293,734–293,819). JRY32 was constructed by replacing the hmr∷TRP1 locus in JRY25 (from HMR-E through the TRP1 gene and Z1 segment) with a hybrid HMRα locus from plasmid pHMRα. This plasmid contains ligated genomic fragments of HMR-E (Chr III coordinates 292,385–293,029) fused with HML sequences containing the X, Yα, and Z1 segments (Chr III coordinates 12,239–13,909).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotypea |

|---|---|

| W303-1a | MATaade2-1 can1-100 his3-11, 15 leu2-3, 112 trp1-1 ura3-1 |

| RS547 | HMLaMATaHMRaleu2-1 can1-100 met trp1-1 his3, his4, ade2-1 |

| RS1230 | MATα sir3-8 ade2 trp1-1 ura3 leu2 his3 his4 |

| RS1231 | MATasir3-8 ade2 trp1-1 |

| XRY19 | HMLα mat∷LEU2 hmr∷TRP1 sir3Δ∷kanMX6 trp1-1 leu2 ura3 his3 can 1-100 ade2-1 |

| JRY17 | HMLamat∷LEU2 hmr∷TRP1 sir3Δ∷kanMX6 bar1Δ∷S.p.his5+ trp1-1 leu2 ura3 his3 can 1-100 ade2-1 |

| JRY19 | HMLamat∷LEU2 hmr∷TRP1 sir3-8 bar1Δ∷S.p.his5+ trp1-1 leu2 ura3 his3 can 1-100 ade2-1 |

| JRY25 | HMLamat∷LEU2 hmr∷TRP1 sir3-8 bar1Δ∷S.p.his5+ trp1Δ∷kanMX6 leu2 ura3 his3 can 1-100 ade2-1 |

| JRY27 | HML-Pamat∷LEU2 hmr∷TRP1 sir3-8 bar1Δ∷S.p.his5+ trp1Δ∷kanMX6 leu2 ura3 his3 can 1-100 ade2-1 |

| JRY30 | HMLα mat∷kanMX6 HMRasir3-8 ade2 trp1-1 ura3 leu2 his3 his4 |

| JRY32 | HMLamat∷LEU2 HMRα sir3-8 bar1Δ∷S.p.his5+ trp1Δ∷kanMX6 leu2 ura3 his3 can 1-100 ade2-1 |

S.p.his5+, Schizosaccharomyces pombe his5+ gene.

Strains with the sir3-8 mutation (RS1230, RS1231, JRY19, JRY25, JRY27, and JRY32) were all grown to early log phase in yeast extract–peptone–dextrose medium (YPD) before synchronizing with 0.2 m hydroxyurea (HU) at the nonpermissive temperature. In the case of JRY27, an initial synchrony with 150 nm alpha factor (αF) was used for a better outcome before synchronizing with HU as above. To restore silencing, strains were shifted back to permissive temperature either with HU to prevent passage through S phase or released into fresh YPD to allow for cell-cycle progression. Samples were taken at 1-hr intervals and subjected to DNA and RNA measurements.

Plasmids:

The a1 promoter, α1 promoter, and TRP1 promoter present at hmr∷TRP1 were fused to a yEmRFP reporter gene in 2-μm plasmids pJR67, pJR68, and pJR69, respectively. W303-1a was transformed with each plasmid for measurements of expression of reporter gene from corresponding promoter.

Flow cytometry:

Flow cytometry analysis of DNA content was performed as described (Haase and Reed 2002). Briefly, cells were harvested and fixed with 70% ethanol. After sonication, cells were treated with RNaseA (Sigma) and pepsin (Sigma). Samples were stained with CYTOX Green (Invitrogen) and analyzed on a FACScan using Cell Quest Pro software (BD).

RT–PCR:

Total RNA was extracted with a RiboPure–Yeast kit (Applied Biosystems) followed by treatment with RNase-free DNase (Applied Biosystems). RT–PCR was performed with SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Real-time PCR and quantification:

Real-time PCR was performed with a LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master kit according to recommended conditions. Experiments were conducted and analyzed in Mastercycler ep realplex2 (Eppendorf) according to manufacturer's instructions. Primer sequences for a1, α1, ACT1, 18S, and yEmRFP are listed in supporting information, Table S1. For each set of samples, the RNA level at the 0-hr time point, normalized to either an ACT1 or 18S internal control, was set to 1.0 and RNA levels from subsequent time points were normalized relative to the initial state. For comparison of the RNA level from derepressed HMRa1 and HMLα1, the relative amount of HMRa1 and HMLα1 RNA was measured by normalizing to the corresponding locus in genomic DNA isolated from JRY30, which only contains one copy of each transcription unit. The relative amount of HMRa1 RNA was set to 1.0. For measurement of promoter strength, the RNA level of yEmRFP was normalized to the ACT1 internal control, and the relative amount of transcript from a1 promoter was set to 1.0.

RESULTS

Silencing at HMR requires passage through S phase; however, it could be partially established at HML during early S phase arrest:

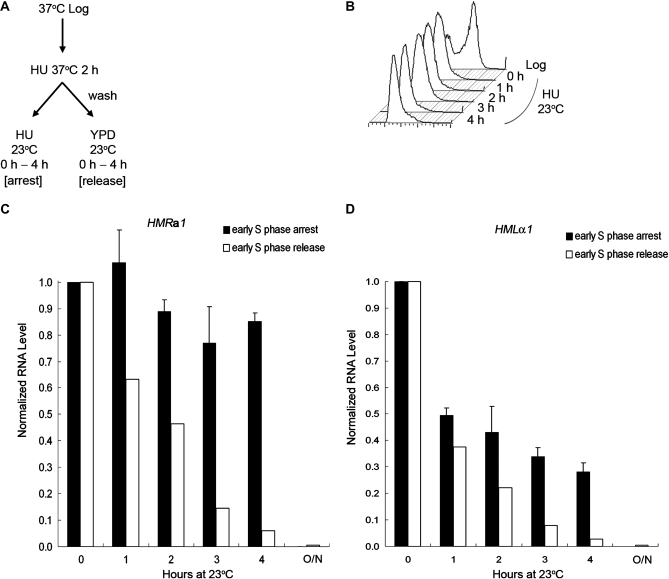

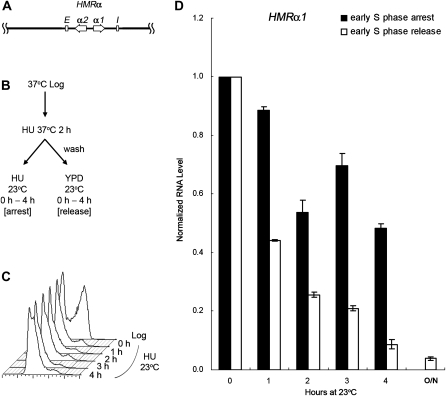

Previous work from our laboratory identified a point mutation in the SIR2 gene, which caused mating defects in haploid strains of either mating type at 37° but not at 23° (Wang et al. 2008). RNA measurements demonstrated that the lack of mating at 37° was due to loss of silencing. We also noted that when cultures were shifted from 37° to 23°, it took >8 hr for silencing to be reestablished at the HMR locus (Wang et al. 2008). On the other hand, it took <4 hr to achieve a similar extent of silencing at HML (data not shown). These observations prompted us to consider the possibility that establishment of silencing at HML might not have the same cell-cycle requirement as had been described previously for HMR. To characterize the difference in cell-cycle requirement we monitored the establishment of silencing at the HMR locus in a MATα strain and at the HML locus in a MATa strain with the same sir3-8 temperature-sensitive allele that had been used in several previous studies on this topic. Cells were grown to log phase at 37° (the nonpermissive temperature that disrupts silencing), synchronized in early S phase with HU, then shifted to 23° (the permissive temperature) either in the presence of HU to prevent passage through S phase or released into fresh medium without HU to allow cell-cycle progression (Figure 1A). HU rather than αF was used because only the MATa strain is sensitive to αF, while HU allowed us to compare strains of either mating type under the same condition. Samples were withdrawn at the times indicated and their DNA content monitored by flow cytometry. The cells held in HU maintained a 1n peak of DNA content during the course of the experiment, demonstrating an early S phase arrest by HU (Figure 1B), whereas cells incubated without HU progressed through the cell cycle (data not shown). RNA was extracted from the above samples, subjected to RT–PCR, and quantified by real-time PCR. The amount of HMLα1 and HMRa1 RNA level was normalized to the ACT1 RNA control, respectively. At the 0-hr time point, just after cells have been shifted to 23°, when they were still fully derepressed, the ratio of HMRa1/ACT1 RNA (Figure 1C) or HMLα1/ACT1 RNA (Figure 1D) for each strain was set to 1.0. As shown in Figure 1C, the expression level of HMRa1 RNA remained high in cells held in HU, consistent with previous studies (Miller and Nasmyth 1984; Fox et al. 1997; Kirchmaier and Rine 2001; Li et al. 2001; Lau et al. 2002; Kirchmaier and Rine 2006; Osborne et al. 2009). Although there was a slight decrease during incubation at 23° in HU (to 0.85 at the 4-hr time point), this extent of silencing may have been due to a small portion of the cells that escaped the HU block and entered the cell cycle. In contrast, as shown in Figure 1D, the HMLα1 RNA level showed a significant decrease under the same condition (to 0.28 at the 4-hr time point). This demonstrated that substantial silencing of the HML locus could occur without passage through S phase and thus contrasted with the well-documented cell-cycle requirement for establishment of silencing at HMR. Cells released from the S phase block had an even greater drop in the HMLα1 RNA level, to 0.028 at the 4-hr time point. This is to be compared with cells grown at 23° for 11 hr in which the HMLα1 RNA level was even lower, 0.004 (Figure 1D). Thus, it took several generations for silencing to be fully established, consistent with previous observations and our results on the HMR locus, which also required several cell division cycles for the locus to be fully silenced (Katan-Khaykovich and Struhl 2005) (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.—

Silencing can be partially established at HML without passage through S phase, while silencing at HMR cannot. (A) Experimental outline. MATα sir3-8 cells (RS1230) and MATa sir3-8 cells (RS1231) were used to analyze silencing at HMR and HML, respectively. Cells were grown to log phase at 37°, synchronized in early S phase with HU, and then shifted to 23° either with HU to prevent passage through S phase or released into fresh YPD to allow for cell-cycle progression. (B) DNA content. Samples at 23° were withdrawn at the times indicated and their DNA content monitored by flow cytometry. A representative result of samples held in HU is shown. (C) HMRa1 expression. RNA was extracted at the indicated time points from both S phase-arrested and -released samples, subjected to RT–PCR, and quantified by real-time PCR. The HMRa1 RNA level at the 0-hr time point, normalized to the ACT1 control, was set to 1.0. The average of two independent experiments is shown for the S phase-arrested samples (shaded bars) and one representative experiment is shown for S phase-released samples (open bars). (D) HMLα1 expression. A similar procedure and analysis was done as described in C, except that the HMLα1 RNA level was measured. In C and D, the RNA level for fully silenced cells grown at 23° overnight is also shown (labeled O/N).

The difference in cell-cycle requirement for establishment of silencing at HML vs. HMR was due to the transcription units of these loci rather than the flanking silencers:

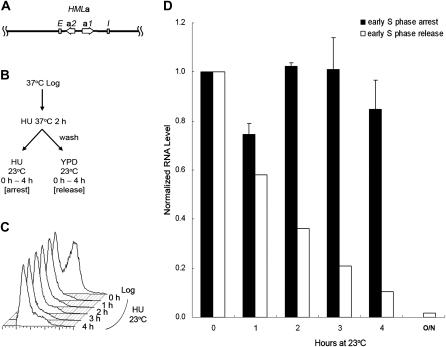

Despite some similarities between the HML and HMR loci, they are composed of different transcription units and somewhat different flanking silencers. Therefore, there were two possible explanations for the difference in cell-cycle requirement, the transcription units or the flanking silencers. To distinguish these possibilities, we constructed a strain carrying an HMLa locus, which contained the a1/a2 transcription unit from the HMR locus instead of the usual HML α1/α2 transcription unit, but flanked by the usual HML silencers, as diagrammed in Figure 2A. Thus, if the silencers caused the different cell-cycle requirement of the HML locus, they should be able to convey the difference to the HMLa locus, allowing silencing to be partially reestablished without passage through S phase. On the other hand, if the difference was linked to the transcription units, this substitution should prevent the establishment of silencing before S phase.

Figure 2.—

Silencing is not established at an HMLa locus without passage through S phase. (A) A diagram of the modified HML locus, HMLa, is shown. It contains the a1/a2 transcription unit from HMR instead of the usual HMLα1/α2 transcription unit, but flanked by the usual HML silencers. (B) Experimental outline. The scheme for this experiment is similar to that described in Figure 1, except that HMLa sir3-8 cells (JRY19) were used. (C) DNA content. Samples for S phase arrest were withdrawn at the time points indicated and their DNA content monitored by flow cytometry. (D) HMLa1 expression. RNA was extracted at the indicated time points from both S phase-arrested and -released samples, subjected to RT–PCR, and quantified by real-time PCR. The HMLa1 RNA level at the 0-hr time point, normalized to either an 18S rRNA or the ACT1 internal control, was set to 1.0. The average of two independent experiments is shown. Also shown is the RNA level for cells grown at 23° overnight (labeled O/N).

To test it, we used a similar experimental strategy (Figure 2B) as we did for WT HM loci. A strain with the HMLa locus and mutations at MAT and HMR so that there was no other source of a1 mRNA was synchronized in early S phase with HU at the nonpermissive temperature, then shifted to the permissive temperature, either with HU for early S phase arrest or released into fresh medium to allow for cell-cycle progression (Figure 2, B and C). Cells arrested in early S phase kept expressing a1 RNA from the HMLa locus at a high level, while cells released from the block established silencing as cells progressed through the cell cycle (Figure 2D). The normalized HMLa1 RNA level was 0.85 after arresting in early S phase for 4 hr. In contrast, the HMLa1 level decreased to 0.10 at the 4-hr time point in the released samples (Figure 2D). To check that the cell-cycle requirement was not an artifact caused by an HU-induced checkpoint, the same strain was synchronized in G1 with α-factor in a similar experiment. Cells arrested in G1 phase still did not establish silencing at this hybrid locus (Figure S1), indicating that arresting with α-factor or HU gave the same result. Therefore, silencing was not established at the HMLa locus without passage through S phase. These results indicated that the difference in the cell-cycle requirement for establishment of silencing at HML vs. HMR was linked to the transcription units.

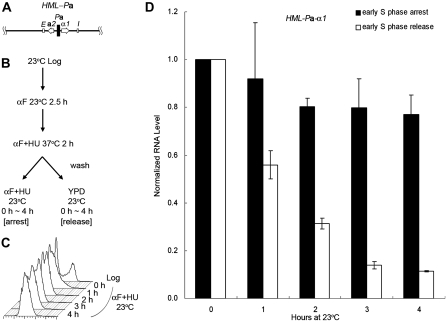

The difference in cell-cycle requirement for establishment of silencing between HML and HMR was due to transcription, rather than the gene product:

To further delineate which part of the transcription units, i.e., the promoter or the open reading frame (ORF) caused this difference, we constructed a strain (JRY27) with a hybrid HML-Pa locus by substituting the usual α1/α2 divergent promoter with the a1/a2 promoter. This construct expressed the α1 protein from the a1 promoter instead of the usual α1 promoter (Figure 3A). HU was used to synchronize cells at 37° as in Figures 1 and 2. After the HU block cells were shifted back to 23°, either with HU for continued S phase arrest or released into fresh medium to allow cell-cycle progression. Similar to the result with an HMLa locus (Figure 2), the α1 RNA level expressed from the a1 promoter at the hybrid HML-Pa locus showed no significant decrease without passage through S phase (Figure 3D, 0.77 for the 4-hr time point). On the other hand, in cells allowed to pass through the cell cycle, silencing was reestablished and transcription dropped to 0.11 after 4 hr. Since silencing was not established at the hybrid HML-Pa locus without passage through S phase, the difference in cell-cycle requirement between HML and HMR was due to the promoter-based transcription activity, rather than to the gene product from the ORF.

Figure 3.—

Silencing is not established at a hybrid HML-Pa locus without passage through S phase. (A) A diagram of the hybrid HML-Pa locus is shown. It expresses the α1 protein from the a1 promoter instead of the usual α1 promoter. (B) Experimental outline. An HML-Pa sir3-8 strain (JRY27) was treated with αF at 23° for 2.5 hr, then shifted to 37° in the presence of αF and HU for 2 hr to synchronize cells in early S phase. The culture was then shifted back to 23°, either with HU for S phase arrest or released into fresh YPD to allow for cell-cycle progression. (C) DNA content. Samples for S phase arrest were withdrawn at the times indicated and their DNA content monitored by flow cytometry. (D) HMLα1 expression at the HML-Pa locus. RNA was extracted at the indicated time points from both S phase-arrested and -released samples, subjected to RT–PCR, and quantified by real-time PCR. For either cell-cycle condition, the HMLα1 RNA level at the 0-hr time point, normalized to 18S rRNA, was set to 1.0. The average of two independent experiments is shown.

The a1 promoter was significantly stronger than the α1 promoter:

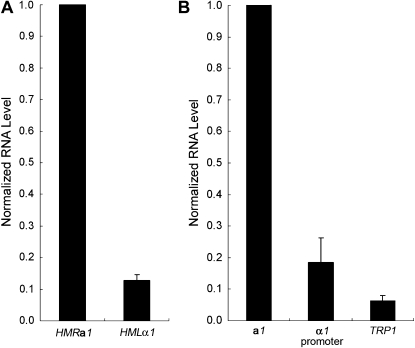

To understand the linkage between the cell-cycle requirement and the corresponding promoter, we measured the relative strength of the a1 and α1 promoters. First, the RNA level from the derepressed HMLα1 and HMRa1 loci was measured as an indicator of their promoter strength. We found that the HMLα1 RNA level was 0.13, relative to 1.0 for HMRa1 (Figure 4A). To confirm that the measurement of these RNA levels reflected the promoter strength rather than half-life of the RNAs, the a1 promoter and α1 promoter were fused to a yEmRFP reporter gene (Keppler-Ross et al. 2008) and the amount of this transcript from each promoter was measured. When the normalized yEmRFP RNA level from the a1 promoter was set to 1.0, the level from the α1 promoter was 0.18 (Figure 4B). Therefore, using two different methods, we found that the a1 promoter was significantly stronger than the α1 promoter.

Figure 4.—

The a1 promoter is significantly stronger than the α1 promoter and a weakened TRP1 promoter. (A) RNA levels from derepressed HMLα1 and HMRa1. An HMLα matΔ∷kanMX6 HMRa sir3-8 strain (JRY30) was grown at the nonpermissive temperature and used to extract RNA for RT–PCR. RNA was quantified as described in materials and methods. (B) Measurement of promoter strength. The a1 promoter, α1 promoter, and TRP1 promoter present at hmr∷TRP1 were fused to a yEmRFP reporter gene and expressed from 2μ plasmids. RNA was extracted, subjected to RT–PCR, and quantified by real-time PCR. The yEmRFP RNA level from the a1 promoter, normalized to the ACT1 internal control, was set to 1.0. The average of two independent experiments is shown.

Silencing was partially reestablished without passage through S phase at a chimeric HMR locus containing a weaker promoter, but not at the wild-type HMR locus:

The results presented above indicated that the strength of the promoter and hence the amount of transcription through the locus determined the cell-cycle requirement or lack thereof. To test this in another way, a strain (JRY27) with an hmr∷TRP1 locus harboring a weakened TRP1 promoter, flanked by the usual HMR silencers, was used (Figure 5A). Measurement of promoter strength with the yEmRFP reporter gene showed that this TRP1 promoter was much weaker than the a1 promoter (Figure 4B). This strain also contained the hybrid HML-Pa locus. As we showed in Figure 3, silencing was not established at that locus without passage through S phase. In contrast, the TRP1 transcript from the hmr∷TRP1 locus measured from the same samples decreased significantly during S phase arrest (Figure 5B). When the TRP1 RNA level at the 0-hr time point was set to 1.0, after 4 hr of arrest in early S phase, the RNA level from hmr∷TRP1 dropped to 0.31, a much greater drop than that seen from the HML-Pa promoter driving the α1 transcript in the same strain (compare Figures 5B and 3D). Therefore, in contrast to the WT HMR locus, silencing could be partially established at the hybrid HMR locus containing a weaker promoter.

Figure 5.—

Substantial silencing can occur at an hmr∷TRP1 locus without passage through S phase. (A) A diagram of the hmr∷TRP1 locus (JRY27), containing the TRP1 transcription unit driven by a weakened TRP1 promoter, flanked by the usual HMR silencers. (B) TRP1 expression at the hmr∷TRP1 locus. The strain and the samples are the same ones used for the experiment shown in Figure 3, although TRP1 RNA quantification is shown here. For both S phase arrest and release, the TRP1 RNA level at time point 0 hr, normalized to an 18S rRNA internal control, was set to 1.0. The average of two independent experiments is shown.

We also tested this conclusion in a strain that had the α1/α2 transcription unit from HML flanked by the HMR silencers (Figure 6A). In this case, we observed an intermediate phenotype (Figure 6D), presumably because the α1 promoter strength is much weaker than the a1 promoter, but still stronger than the TRP1 promoter. Silencing could be established to a certain extent, as the α1 RNA level dropped to 0.48 after a 4-hr arrest in early S phase when the initial RNA level was set to 1.0. The α1 RNA level was somewhat higher than the TRP1 RNA level measured at the same time point (comparing Figures 6D and 5D, 0.48 vs. 0.31), showing less silencing with the stronger promoter. Although the HMR α strain showed significant silencing before passage through S phase, it was less than was seen at HMLα (Figure 1). Therefore, it is possible that the silencers may have some effect on the kinetics of silencing.

Figure 6.—

Substantial silencing can occur at an HMRα locus without passage through S phase. (A) A diagram of the hybrid HMRα locus is shown. (B) Experimental outline. The scheme for this experiment is similar to that described in Figure 1, except that an HMRα sir3-8 strain (JRY32) was used. (C) DNA content. Samples for S phase arrest were withdrawn at the times indicated and their DNA content monitored by flow cytometry. (D) α1 expression at the HMRα locus. RNA was extracted at the indicated time points from both S phase-arrested and -released samples, subjected to RT–PCR, and quantified by real-time PCR. For either cell-cycle condition, the HMRα1 RNA level at the 0-hr time point, normalized to 18S rRNA, was set to 1.0. The average of two RNA measurements is shown. Also shown is the RNA level for cells grown at 23° overnight (labeled O/N).

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate a difference in the S phase requirement for establishment of silencing at HML and HMR. While silencing cannot occur at the HMR locus without passage through S phase (Miller and Nasmyth 1984; Fox et al. 1997; Kirchmaier and Rine 2001; Li et al. 2001; Lau et al. 2002; Kirchmaier and Rine 2006; Osborne et al. 2009) (Figure 1C), it can be established to a significant extent at the HML locus under the same conditions (Figure 1D). This difference explains our previous result that silencing was established at HML much more rapidly than at HMR after shifting a sir2 temperature-sensitive strain from a nonpermissive to a permissive temperature (Wang et al. 2008).

Using various chimeric constructs we determined that the different S phase requirement for silencing HML and HMR was due primarily to the transcription units of these loci rather than to the flanking silencers. For example, an HML locus with the a1/a2 transcription unit instead of the usual α1/α2 transcription unit, but flanked by the usual HML silencer elements, could not be silenced without passage through S phase (Figure 2). We narrowed down this difference by showing that a substitution of the α1/α2 promoter at HML with the a1/a2 promoter also prevented the establishment of silencing before passage through S phase (Figure 3). Therefore, the different S phase requirement for silencing HMLα and HMRa was due to the different promoters present at those loci.

To test whether the two promoters had different strengths we measured transcription activity from each promoter and found that the a1 promoter was significantly stronger than the α1 promoter (Figure 4). We did this in two ways. First we compared the amount of RNA from derepressed HMRa1 with the amount from HMLα1 (Figure 4A). To correct for the possibility that a1 mRNA might have a greater half-life than α1 mRNA, we also fused each of these promoters to a reporter gene and measured the amount of RNA from this gene (Figure 4B). Both experiments showed that the a1 promoter was significantly stronger than the α1 promoter. Furthermore, by substituting the a1/a2 promoter and gene at HMR with the much weaker TRP1 promoter and its gene, we observed that silencing could be established at the HMR locus without passage through S phase (Figure 5B). On the other hand, the silencers may also influence the S phase requirement. When we tested an HMRα construct, which had the HMR silencers but the α1/α2 transcription unit, less silencing was observed when holding cells in early S phase than when the α1/α2 transcription unit was at its natural locus, HML (Figure 6B). Nevertheless, the data from the various constructs tested support our conclusion that the amount of transcription through a gene counteracts establishment of silencing, and that influences the cell-cycle requirement. That is, the stronger the promoter, the more resistance there is to establishment of silencing and the more stringent is the S phase requirement. It seems reasonable that the frequent passage of RNA polymerase II from a relatively strong promoter inhibits the spreading of the Sir complex from the silencers. The euchromatin marks that result from active transcription may also hinder the establishment of heterochromatin.

Previous studies have also observed a competition between transcription and silencing. For instance, a URA3 reporter gene could be silenced at a greater distance from the telomere when PPR1, the trans-activator of URA3, was deleted (Renauld et al. 1993). In addition, it was found that a silent telomeric URA3 gene could become expressed if cells were arrested in G2/M and that depended on the PPR1 activator (Aparicio and Gottschling 1994).

A recent study using galactose induction of Sir3 to study the kinetics of spreading of the Sir complex during reestablishment of silencing found that the Sir complex spread more rapidly at HMR than at a telomere, and evidence was presented that the HMR-E silencer was responsible for this effect (Lynch and Rusche 2009). However, that study did not use cells blocked in the cell cycle and thus probably does not apply to the results presented here.

Additional support for the competition between transcription and silencing came from studying silencing in mutants lacking the chromatin-modifying enzymes Dot1 or Set1, responsible for euchromatic methyl marks on histone H3K79 and H3K4, respectively. In dot1Δ and set1Δ mutants, establishment of silencing was more rapid than in wild-type cells, probably because active transcription was compromised by the hypomethylated chromatin and hence was less resistant to silencing (Osborne et al. 2009). However, it may also have been caused by the better binding of Sir proteins to hypomethylated histones (Onishi et al. 2007; Sampath et al. 2009).

Interestingly, the reason why S phase passage is necessary for establishing silencing at HMR is still not understood. Studies with nonreplicating HMR circles provided strong evidence that it is not DNA replication itself that is needed for establishing silent chromatin (Kirchmaier and Rine 2001; Li et al. 2001). On the basis of our findings that promoter strength influences the S phase requirement, we propose two different S phase events that may facilitate the spreading of the Sir complex and allow it to overcome the competition from transcription. One is an S phase-dependent post-transcriptional modification of a Sir protein or a histone that would strengthen the association between the Sir complex and nucleosomes. A recent study by Holt et al. (2009) identified Sir2, Sir3, and Sir4 among 308 substrates of the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdc28/Cdk1 in cells synchronized at M phase. Conceivably, similar modifications of Sir proteins or histones could explain the S phase requirement.

Another explanation could be that histone synthesis and deposition occur during S phase and that facilitates silencing. It is well established that transcription tends to reduce histone occupancy on chromosomal DNA. For example, the histone occupancy on the GAL10 coding region is inversely correlated with transcription activity (Schwabish and Struhl 2004). Using antihistone H3 chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), we obtained a similar result. We observed a bigger decrease in histone occupancy at the HMRa1 transcription unit than at the HMLα1 transcription unit when shifting an exponentially growing sir3-8 ts strain from 23° to 37° (data not shown), agreeing with our result that the a1 promoter is stronger than the α1 promoter. The frequent passage of RNA polymerase II from the relatively strong a1 promoter may cause reduced nucleosome occupancy, which in turn, provides less binding surface for the Sir complex, thus counteracting silencing. During passage through S phase, when histone synthesis and deposition are robust, more nucleosomes may be incorporated into the silent regions, providing a better binding surface for the Sir complex. This process is not necessarily coupled to DNA replication since it can take place on a nonreplicating HMR circle (Kirchmaier and Rine 2001; Li et al. 2001).

Martins-Taylor et al. (2004) previously observed that establishment of silencing at HML did not require passage through S phase, but did require passage through G2/M. However, their protocol was very different than ours and did not compare HML and HMR. They synchronized sir3-8 ts cells in G2/M at 23° and then released them into αF at 37°. They measured the fraction of cells blocked in G1 by αF as a measure of silencing at HML. Our results agree with their conclusion and extend it by showing that it is the strength of the promoter that influences the S phase requirement.

One interesting question not answered by our results is how the amount of silencing observed for the population relates to that of the individual cell. For example, in the experiment shown in Figure 1D, when the amount of HMLα1 RNA during S phase arrest decreased to 30% of its original level after 4 hr at a permissive temperature, was that because 70% of the cells were fully silenced or because the entire population was partially silenced? The two possibilities correspond to two different views for the establishment of silencing. One is that intermediate states of silencing exist and complete silencing is achieved gradually as cells continue to divide. The other assumes an all-or-none model, that a locus is either completely silenced or derepressed (Gottschling et al. 1990). Two recent studies showed that complete silencing required several generations and thus favor the former model (Katan-Khaykovich and Struhl 2005; Osborne et al. 2009). Therefore, the decrease in RNA level we detected at HML in the first few hours at the permissive temperature (Figure 1) is likely to reflect a reduced RNA level in the population of cells, few or none of which are completely silenced.

Even though substantial silencing was established without passage through S phase at the HM loci with a weak promoter, e.g., HMLα and hmr∷TRP1, it didn't reach the same extent as that seen for cells allowed to pass through the cell cycle. For example, as shown in Figure 1D, the HMLα1 RNA level decreased substantially to 0.28 after 4 hr in early S phase arrest, while it showed an even greater drop to 0.028 at the corresponding time point when released from the S phase block. A similar difference was observed at the hmr∷TRP1 locus (Figure 5B). One possible cause is the previously described G2/M phase requirement, which is independent of the S phase requirement (Lau et al. 2002). That study concluded that it was the dissolution of sister-chromatid cohesion at anaphase that accounted for the G2/M-phase requirement (Lau et al. 2002).

In summary, the results presented have clarified the different cell-cycle requirement for establishment of silencing at HML and HMR. That is, silencing can be partially established at HML without passage through S phase, but not at HMR. We have analyzed the difference and attributed it to the transcriptional activity of these loci. We found that the greater the transcriptional activity, the more resistance there is to silencing and the more stringent the S phase requirement. The competition between transcription and silencing may allow for a certain amount of plasticity for switching to the opposite phenotype, and this may be particularly important in metazoans.

Acknowledgments

We thank Janet Leatherwood for sharing facilities and Vinaya Sampath and other members of our laboratory for helpful discussions. We thank Evelyn Prugar for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM28220 and GM55641.

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.110.120592/DC1.

References

- Aparicio, O. M., and D. E. Gottschling, 1994. Overcoming telomeric silencing: a trans-activator competes to establish gene expression in a cell cycle-dependent way. Genes Dev. 8 1133–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmen, A. A., L. Milne and M. Grunstein, 2002. Acetylation of the yeast histone H4 N terminus regulates its binding to heterochromatin protein SIR3. J. Biol. Chem. 277 4778–4781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, C. A., and K. H. McConnell, 2005. Toward biochemical understanding of a transcriptionally silenced chromosomal domain in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 280 8629–8632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, C. A., A. E. Ehrenhofer-Murray, S. Loo and J. Rine, 1997. The origin recognition complex, SIR1, and the S phase requirement for silencing. Science 276 1547–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser, S. M., and M. M. Cockell, 2001. The molecular biology of the SIR proteins. Gene 279 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschling, D. E., O. M. Aparicio, B. L. Billington and V. A. Zakian, 1990. Position effect at S. cerevisiae telomeres: reversible repression of Pol II transcription. Cell 63 751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase, S. B., and S. I. Reed, 2002. Improved flow cytometric analysis of the budding yeast cell cycle. Cell Cycle 1 132–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, L. J., B. B. Tuch, J. Villen, A. D. Johnson, S. P. Gygi et al., 2009. Global analysis of Cdk1 substrate phosphorylation sites provides insights into evolution. Science 325 1682–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, G. J., J. C. Tanny, A. D. Rudner, S. A. Gerber, S. Danaie et al., 2002. Steps in assembly of silent chromatin in yeast: Sir3-independent binding of a Sir2/Sir4 complex to silencers and role for Sir2-dependent deacetylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 4167–4180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katan-Khaykovich, Y., and K. Struhl, 2005. Heterochromatin formation involves changes in histone modifications over multiple cell generations. EMBO J. 24 2138–2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppler-Ross, S., C. Noffz and N. Dean, 2008. A new purple fluorescent color marker for genetic studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. Genetics 179 705–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchmaier, A. L., and J. Rine, 2001. DNA replication-independent silencing in S. cerevisiae. Science 291 646–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchmaier, A. L., and J. Rine, 2006. Cell cycle requirements in assembling silent chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26 852–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, A., H. Blitzblau and S. P. Bell, 2002. Cell-cycle control of the establishment of mating-type silencing in S. cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 16 2935–2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. C., T. H. Cheng and M. R. Gartenberg, 2001. Establishment of transcriptional silencing in the absence of DNA replication. Science 291 650–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou, G. G., J. C. Tanny, R. G. Kruger, T. Walz and D. Moazed, 2005. Assembly of the SIR complex and its regulation by O-acetyl-ADP-ribose, a product of NAD-dependent histone deacetylation. Cell 121 515–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie, III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach et al., 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, P. J., and L. N. Rusche, 2009. A silencer promotes the assembly of silenced chromatin independently of recruitment. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29 43–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins-Taylor, K., M. L. Dula and S. G. Holmes, 2004. Heterochromatin spreading at yeast telomeres occurs in M phase. Genetics 168 65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A. M., and K. A. Nasmyth, 1984. Role of DNA replication in the repression of silent mating type loci in yeast. Nature 312 247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi, M., G. G. Liou, J. R. Buchberger, T. Walz and D. Moazed, 2007. Role of the conserved Sir3-BAH domain in nucleosome binding and silent chromatin assembly. Mol. Cell 28 1015–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, E. A., S. Dudoit and J. Rine, 2009. The establishment of gene silencing at single-cell resolution. Nat. Genet. 41 800–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst, A. V., E. Dunleavy and G. Almouzni, 2009. Epigenetic inheritance during the cell cycle. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10 192–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renauld, H., O. M. Aparicio, P. D. Zierath, B. L. Billington, S. K. Chhablani et al., 1993. Silent domains are assembled continuously from the telomere and are defined by promoter distance and strength, and by SIR3 dosage. Genes Dev. 7 1133–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudner, A. D., B. E. Hall, T. Ellenberger and D. Moazed, 2005. A nonhistone protein-protein interaction required for assembly of the SIR complex and silent chromatin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25 4514–4528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusche, L. N., A. L. Kirchmaier and J. Rine, 2002. Ordered nucleation and spreading of silenced chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 13 2207–2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusche, L. N., A. L. Kirchmaier and J. Rine, 2003. The establishment, inheritance, and function of silenced chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72 481–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampath, V., P. Yuan, I. X. Wang, E. Prugar, F. van Leeuwen et al., 2009. Mutational analysis of the Sir3 BAH domain reveals multiple points of interaction with nucleosomes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29 2532–2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, S., and R. W. Davis, 1979. Replacement of chromosome segments with altered DNA sequences constructed in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76 4951–4955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabish, M. A., and K. Struhl, 2004. Evidence for eviction and rapid deposition of histones upon transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 10111–10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. L., J. Landry and R. Sternglanz, 2008. A yeast sir2 mutant temperature sensitive for silencing. Genetics 180 1955–1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, E. Y., K. A. Zawadzki and J. R. Broach, 2006. Single-cell observations reveal intermediate transcriptional silencing states. Mol. Cell 23 219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]