Abstract

Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance is a major cause of worldwide increases in malaria mortality and morbidity. Recent laboratory and clinical studies have associated chloroquine resistance with point mutations in the gene pfcrt. However, direct proof of a causal relationship has remained elusive and most models have posited a multigenic basis of resistance. Here, we provide conclusive evidence that mutant haplotypes of the pfcrt gene product of Asian, African, or South American origin confer chloroquine resistance with characteristic verapamil reversibility and reduced chloroquine accumulation. pfcrt mutations increased susceptibility to artemisinin and quinine and minimally affected amodiaquine activity; hence, these antimalarials warrant further investigation as agents to control chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria.

Chloroquine has for decades been the primary chemotherapeutic means of malaria treatment and control (1). This safe and inexpensive 4-aminoquinoline compound accumulates inside the digestive vacuole of the infected red blood cell, where it is believed to form complexes with toxic heme moieties and interfere with detoxification mechanisms that include heme sequestration into an inert pigment called hemozoin (2–4). Chloroquine resistance (CQR) was first reported in Southeast Asia and South America and has now spread to the vast majority of malaria-endemic countries (1). pfcrt was recently identified as a candidate gene for CQR after the analysis of a genetic cross between a chloroquine-resistant clone (Dd2, Indochina) and a chloroquine-sensitive clone (HB3, Honduras) (5–7). The PfCRT protein localizes to the digestive vacuole membrane and contains 10 putative transmembrane domains (7, 8). Point mutations in PfCRT, including the Lys76 → Thr (K76T) mutation in the first predicted transmembrane domain, show an association with CQR in field isolates and clinical studies (7, 9, 10). Episomal complementation assays demonstrated a low-level, atypical CQR phenotype in chloroquine-selected, transformed, pseudo-diploid parasite lines that coexpressed the Dd2 form of pfcrt (containing eight point mutations; Table 1), under the control of a heterologous promoter, with the wild-type endogenous allele (7).

Table 1.

Transformation status and PfCRT haplotype of recombinant and wild-type lines. The first round of transformation (11) was performed with GC03 and used a plasmid containing the human dihydrofolate reductase (hDHFR) selectable marker (40). The resulting clone, C1GC03 (fig. S1), shared the same chloroquine IC50 values (Fig. 1) (table S2) and pfcrt coding sequence as GC03. Transformation of C1GC03 in the second round used plasmids containing the blasticidin S-deaminase (BSD) selectable marker (41) and resulted in the C2 to C6 clones. GC03 is a chloroquine-sensitive progeny of the genetic cross between the chloroquine-resistant clone Dd2 (Indochina) and the chloroquine-sensitive clone HB3 (Honduras) (5, 6). Dd2 and 7G8 (Brazil) represent common PfCRT haplotypes found in Asia/Africa and South America, respectively (7). K76I is a chloroquine-resistant line selected from the chloroquine-sensitive 106/1 (Sudan) clone propagated in the presence of high chloroquine concentrations, resulting in the generation of a full complement of PfCRT point mutations including the novel K76I mutation (8). Point mutations in boldface are those previously associated with CQR (7, 8).

| Clone | First plasmid integration | Second plasmid integration | Change in PfCRT haplotype | Functional PfCRT haplotype |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 220 | 271 | 326 | 356 | 371 | ||||

| GC03 | — | — | — | C | M | N | K | A | Q | N | I | R |

| C1GC03 | phDHFR-crt-GC03Pf3′ | — | No | C | M | N | K | A | Q | N | I | R |

| C2GC03 | phDHFR-crt-GC03Pf3′ | pBSD-crt-Dd2Py3′ | No | C | M | N | K | A | Q | N | I | R |

| C3Dd2 | phDHFR-crt-GC03Pf3′ | pBSD-crt-Dd2Pf3′ | Yes | C | I | E | T | S | E | S | T | I |

| C4Dd2 | phDHFR-crt-GC03Pf3′ | pBSD-crt-Dd2Py3′ | Yes | C | I | E | T | S | E | S | T | I |

| Dd2 | — | — | — | C | I | E | T | S | E | S | T | I |

| C5K76I | phDHFR-crt-GC03Pf3′ | pBSD-crt-K76IPf3′ | Yes | C | I | E | I | S | E | S | I | I |

| K76I | — | — | — | C | I | E | I | S | E | S | I | I |

| C67G8 | phDHFR-crt-GC03Pf3′ | pBSD-crt-7G8Py3′ | Yes | S | M | N | T | S | Q | D | L | R |

| 7G8 | — | — | — | S | M | N | T | S | Q | D | L | R |

Abbreviations for amino acid residues: A, Ala; C, Cys; D, Asp; E, Glu; I, Ile; K, Lys; L, Leu; M, Met; N, Asn; Q, Gln; R, Arg; S, Ser; T, Thr.

To address whether mutations in pfcrt are sufficient to confer CQR, we implemented an allelic exchange approach to replace the endogenous pfcrt allele of a chloroquine-sensitive line (GC03) with pfcrt alleles from chloroquine-resistant lines of Asian, African, or South American origin (Table 1) (fig. S1) (11). This approach maintained the endogenous promoter and terminator regulatory elements for correct stage-specific expression and did not use chloroquine during the selection procedure. As a result of this gene’s highly interrupted nature (13 exons) and the dissemination of point mutations throughout the coding sequence, two rounds of genetic transformation were required. This enabled us to obtain pfcrt-modified clones that expressed the pfcrt allele from the chloroquine-resistant lines Dd2 (clones C3Dd2 and C4Dd2), K76I (C5K76I), and 7G8 (C67G8). We also obtained the C2GC03 clone in which recombination had occurred downstream of the functional allele, providing a critical control in correcting for any influence of inserting the two selectable marker cassettes without exchanging pfcrt point mutations (Table 1) (fig. S1).

pfcrt allelic exchange was confirmed by Southern hybridization and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis (fig. S2, A to D, and table S1). Reverse-transcription PCR analysis confirmed transcription of the recombinant functional pfcrt allele (fig. S2C), whereas no transcription was observed from the downstream remnant pfcrt sequences that lacked a promoter and 5′ coding sequence. Western blot analysis (7, 8) revealed expression of PfCRT (about 42 kD) in all clones (fig. S2E). Quantitation analysis predicted a reduction in PfCRT expression of approximately 30 to 40%, 50%, and 0%, respectively, in the C3Dd2/C4Dd2, C5K76I, and C67G8 clones, relative to C2GC03, which itself expressed 30% less PfCRT than did the original GC03 clone (11).

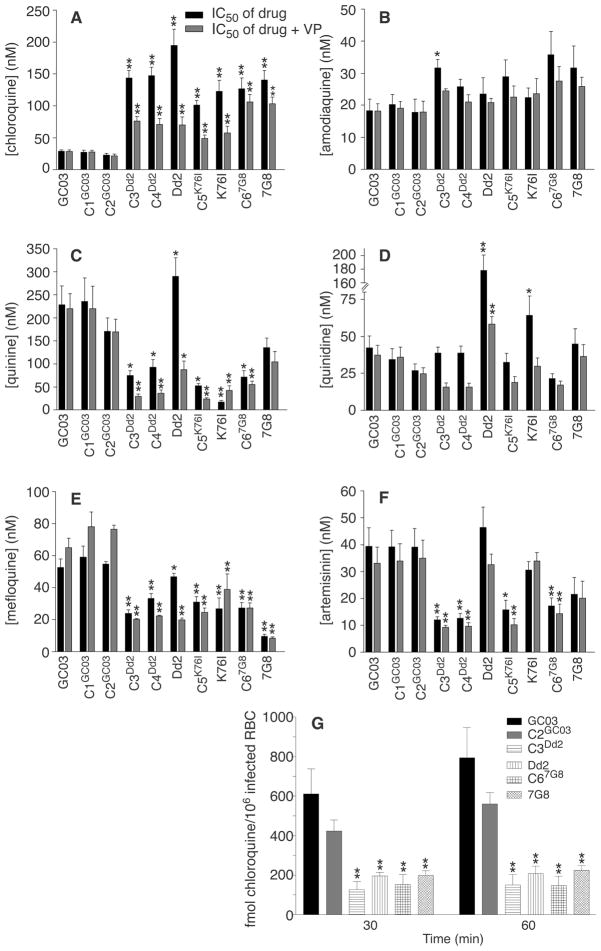

Phenotypic analysis showed that mutant pfcrt alleles conferred a CQR phenotype to chloroquine-sensitive P. falciparum (Fig. 1A). Recombinant clones expressing pfcrt alleles from the chloroquine-resistant lines Dd2, K76I, and 7G8 all had 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values in the range of 100 to 150 nM. These IC50 values were typically 70 to 90% of those observed with the nontransformed chloroquine-resistant lines. All these lines equaled or exceeded the 80 to 100 nM level previously proposed as a threshold diagnostic of in vivo resistant infections (12, 13). In comparison, chloroquine IC50 values in the recombinant control lines C1GC03 and C2GC03 were comparable to those observed with the initial GC03 line (20 to 30 nM). Acquisition of resistance was even more pronounced for the active metabolite monodesethylchloroquine, with IC50 values in the range of 600 to 1200 nM for the pfcrt-modified lines, versus 35 to 40 nM for chloroquine-sensitive lines (table S2).

Fig. 1.

pfcrt mutations confer chloroquine resistance and altered susceptibility to other heme (ferriprotoporphyrin IX)–binding antimalarials in P. falciparum. (A to F) Results of in vitro drug assays with pfcrt-modified and control lines. Each line was tested in duplicate against each antimalarial drug at least four times, in the presence or absence of 0.8 μM verapamil (VP). IC50 values (shown as the mean + SE for each line) correspond to the concentration at which incorporation of [3H]hypoxanthine was half-maximal and were derived from the inhibition curves generated as a function of drug concentration. Mann-Whitney tests were used to assess statistically significant differences between the reference line C2GC03 and the others (*P < 0.05, **P <0.01). IC50 and IC90 values and compound structures are detailed in table S2 and fig. S3. The finding that pfcrt mutations conferred increased susceptibility to both quinine and mefloquine provides an intriguing contrast with the recent report that the introduction of mutations into pfmdr1 led to decreased susceptibility to quinine and increased susceptibility to mefloquine (17). (G) Chloroquine accumulation assays (using 30 nM [3H]chloroquine) confirm that pfcrt mutations confer a CQR phenotype. The saturable component of [3H]chloroquine accumulation, measured as femtomoles of drug per 106 infected red blood cells, was calculated by subtracting the nonsaturable accumulation (measured in the presence of 10 μM unlabeled chloroquine) from the total accumulation (measured in the absence of unlabeled drug). The mean + SE, calculated from five experiments performed in duplicate, is shown for each line. Accumulation values in the pfcrt-modified clones C3Dd2 and C67G8 showed a statistically significant difference from values observed in C2GC03 (**P < 0.01). The chloroquine data in (A) and (G) prove a central role for pfcrt point mutations in conferring CQR to the GC03 line, although they do not rule out the possibility that other loci can contribute to this phenotype. It remains to be established whether mutant pfcrt alleles can confer CQR to multiple, genetically distinct chloroquine-sensitive lines. One hypothesis under consideration is that pfcrt confers CQR and altered susceptibility to other heme-binding antimalarials through a combination of direct effects (which may involve drug-protein interactions) and indirect effects on parasite physiological processes (which may influence drug accumulation and formation of drug-heme complexes).

The lower chloroquine IC50 values observed in the pfcrt-modified clones, relative to the nontransformed chloroquine-resistant lines, may be a consequence of the reduced PfCRT expression levels and other effects stemming from the complex genetic locus created in these recombinant clones (fig. S1). Alternatively, additional genetic factors might be required to attain high chloroquine IC50 values. One candidate secondary determinant is pfmdr1, which encodes the P-glycoprotein homolog Pgh-1 that localizes to the digestive vacuole (14–16). Reed et al. (17) recently demonstrated by allelic exchange that removal of three pfmdr1 point mutations (1034C, 1042D, and 1246Y) from the 7G8 line decreased the chloroquine IC50 values; however, introduction of these mutations into endogenous pfmdr1 did not alter the susceptible phenotype of a chloroquine-sensitive line. Our experiments were performed with the GC03 clone, which carries the HB3-type pfmdr1 allele that in two P. falciparum genetic crosses showed no association with decreased chloroquine susceptibility (5, 18). This allele contains the 1042D point mutation that is prevalent in chloroquine-resistant South American isolates, although this mutation does not show a consistent association with CQR in isolates from other malaria-endemic regions (6, 19–21).

Acquisition of elevated chloroquine IC50 values in the pfcrt-modified clones was accompanied by verapamil chemosensitization, a hallmark of the CQR phenotype (Fig. 1A) (22). Association of both parameters with pfcrt represents a marked departure from earlier suppositions that verapamil reversibility of P. falciparum CQR was analogous to this compound’s chemosensitization of multidrug resistance in mammalian tumor cells, believed to be mediated primarily by adenosine triphosphate–dependent P-glycoproteins (22). We note that verapamil reversibility was more pronounced in the clones expressing recombinant pfcrt from Old World (Dd2, K76I) origins than in the clone expressing the recombinant New World (7G8) allele. These findings are consistent with the recent report of reduced verapamil reversibility in chloroquine-resistant field isolates expressing the PfCRT 7G8 haplotype (23). In an independent confirmation of the CQR phenotype of pfcrt-modified clones, we observed significantly reduced [3H]chloroquine accumulation in the C3Dd2, Dd2, C67G8, and 7G8 clones as compared with the chloroquine-sensitive clones GC03 and C2GC03 (Fig. 1G). These assays measured the uptake into infected red blood cells of the saturable component of chloroquine at nanomolar concentrations, a measure that has been previously found to clearly distinguish chloroquine-resistant and chloroquine-sensitive parasites (24, 25).

Having this set of clones on the same genetic background, in which CQR was produced in vitro via modification of a single gene, allowed us to begin investigations into the relationship between pfcrt, CQR, and P. falciparum susceptibility to related antimalarials. We focused initially on amodiaquine, a chloroquine analog with the same aminoquinoline ring that differs by the presence of an aromatic ring in the side chain (fig. S3). Drug assays showed that the lines harboring mutant pfcrt were slightly less susceptible to amodiaquine (Fig. 1B); nonetheless, the pfcrt-modified clones remained sensitive to this drug, with IC50 values of 22 to 36 nM. A modest degree of cross-resistance was observed between chloroquine and monodesethylamodiaquine, the primary metabolite of amodiaquine (table S2) (26–28). These findings are consistent with the published data on amodiaquine efficacy in areas with a high prevalence of CQR malaria (29, 30) and signal the need for close monitoring for resistance, including screening for possible additional changes in pfcrt sequence, with increased clinical use of amodiaquine. Further, these data suggest that CQR mediated by pfcrt point mutations now prevalent in endemic areas has a high degree of specificity for the chloroquine structure (fig. S3). Other groups have reported that altering the chloroquine side chain length can result in a gain of efficacy against chloroquine-resistant lines (31, 32).

Phenotypic characterization also revealed increased susceptibility (by a factor of 2 to 4) to quinine, mefloquine, and artemisinin and its metabolite dihydroartemisinin in the pfcrt-modified clones (Fig. 1, C, E, and F) (table S2). These data provide direct evidence for an important role for this gene in determining parasite susceptibility to these antimalarials. Collateral hypersensitivity to these compounds is reminiscent of antimalarial susceptibility patterns observed in a Thailand study of P. falciparum field isolates (33) and is encouraging given their current clinical usage in antimalarial combination therapy regimes (34). In comparison to C2GC03, the Dd2 line is more quinine resistant; however, the introduction of the Dd2 pfcrt allele (resulting in the clones C3Dd2 and C4Dd2) conferred quinine susceptibility (Fig. 1C). This implicates pfcrt as a component of a multifactorial process that governs parasite susceptibility to these antimalarials. Upon introduction of pfcrt point mutations, the increased susceptibility to quinine was accompanied by a decrease in susceptibility to the diastereomer quinidine (Fig. 1, C and D).

These data, obtained in lines that were not exposed to chloroquine pressure during their selection, agree with an earlier observation on the chloroquine-selected K76I line (7, 8) and suggest a structure-specific component of PfCRT-mediated drug accumulation in the digestive vacuole. All of these compounds are believed to act, at least in part, by complexing with heme products (35, 36). Possibly, PfCRT mutations affect accumulation by altering drug flux across the digestive vacuole membrane. Our data also document a key role for pfcrt point mutations in the mode of action of verapamil, a known CQR reversal agent (22, 25, 37, 38) that also chemosensitized the pfcrt-modified lines to quinine and quinidine (Fig. 1, C and D). This verapamil-reversible phenotype may reflect a physical association between verapamil and mutant PfCRT and/or mutant PfCRT-mediated physiological changes that alter the activity of verapamil on heme processing and drug-hematin binding. Our genetic system now provides a direct means to evaluate the precise role of individual pfcrt point mutations in determining P. falciparum drug response and verapamil reversibility, via site-directed mutagenesis and introduction of mutant alleles into chloroquine-sensitive lines.

These data are consistent with the concept that the appearance of pfcrt mutant alleles in a limited number of foci was the pivotal driving force behind the genesis and spread of CQR worldwide. The structural specificity of this pfcrt-mediated resistance mechanism is underscored by the finding that pfcrt-modified clones remained susceptible to amodiaquine, promoting the use of this and related compounds that differ in their aminoquinoline side chain for the treatment of chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria. Identification of PfCRT as the major component of CQR and an important determinant of susceptibility to other heme-binding antimalarials offers alternative strategies for targeting the hemoglobin detoxification pathway for malaria treatment and control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Wellems, P. Roepe, and S. Krishna for many helpful discussions. We also thank A. Talley, R. Cooper, D. Jacobus, S. Ward, P. Bray, W. Ellis, P. Ringwald, and N. Shulman. Supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant R01 AI50234, the Speaker’s Fund for Biomedical Research, a New Scholar Award in Global Infectious Disease from the Ellison Medical Foundation, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Research Resources Program for Medical Schools.

Footnotes

Note added in proof: Wootton et al. (39) recently presented compelling evidence for rapid evolutionary sweeps of mutant pfcrt sequences throughout malaria-endemic areas, starting from a limited number of initial foci. These sweeps presumably occurred as a result of intense chloroquine pressure. These data complement and support our finding that mutant pfcrt sequences from different continents can confer CQR to chloroquine-sensitive parasites.

References and Notes

- 1.Ridley RG. Nature. 2002;415:686. doi: 10.1038/415686a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan DJ, Jr, Matile H, Ridley RG, Goldberg DE. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pagola S, Stephens PW, Bohle DS, Kosar AD, Madsen SK. Nature. 2000;404:307. doi: 10.1038/35005132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ginsburg H, Ward SA, Bray PG. Parasitol Today. 1999;15:357. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01502-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wellems TE, et al. Nature. 1990;345:253. doi: 10.1038/345253a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su X-z, Kirkman LS, Wellems TE. Cell. 1997;91:593. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80447-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fidock DA, et al. Mol Cell. 2000;6:861. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(05)00077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper RA, et al. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:35. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Djimdé A, et al. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:257. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101253440403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wellems TE, Plowe CV. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:170. doi: 10.1086/322858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.See supporting data on Science Online.

- 12.Brasseur P, Kouamouo J, Moyou-Somo R, Druilhe P. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46:1. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.46.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cremer G, Basco LK, Le Bras J, Camus D, Slomianny C. Exp Parasitol. 1995;81:1. doi: 10.1006/expr.1995.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foote SJ, Thompson JK, Cowman AF, Kemp DJ. Cell. 1989;57:921. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90330-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson CM, et al. Science. 1989;244:1184. doi: 10.1126/science.2658061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cowman AF, Karcz S, Galatis D, Culvenor JG. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:1033. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.5.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reed MB, Saliba KJ, Caruana SR, Kirk K, Cowman AF. Nature. 2000;403:906. doi: 10.1038/35002615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duraisingh MT, Roper C, Walliker D, Warhurst DC. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:955. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foote SJ, et al. Nature. 1990;345:255. doi: 10.1038/345255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basco LK, Le Bras J, Rhoades Z, Wilson CM. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;74:157. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaiyaroj SC, Buranakiti A, Angkasekwinai P, Looressuwan S, Cowman AF. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:780. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin SK, Oduola AM, Milhous WK. Science. 1987;235:899. doi: 10.1126/science.3544220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehlotra RK, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221440898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krogstad DJ, Gluzman IY, Herwaldt BL, Schlesinger PH, Wellems TE. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43:57. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90661-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bray PG, Mungthin M, Ridley RG, Ward SA. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:170. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.1.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Childs GE, et al. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:7. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.40.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basco LK, Le Bras J. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;48:120. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.48.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bray PG, Hawley SR, Mungthin M, Ward SA. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:1559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olliaro P, et al. Lancet. 1996;348:1196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)06217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adjuik M, et al. Lancet. 2002;359:1365. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De D, Krogstad FM, Cogswell FB, Krogstad DJ. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:579. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ridley RG, et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1846. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Price RN, et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2943. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.12.2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White NJ. Parassitologia. 1999;41:301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foley M, Tilley L. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;79:55. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Neill PM, Bray PG, Hawley SR, Ward SA, Park BK. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;77:29. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krogstad DJ, et al. Science. 1987;238:1283. doi: 10.1126/science.3317830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ursos LMB, Dzekunov S, Roepe PD. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;110:125. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wootton JC, et al. Nature. 2002;418:320. doi: 10.1038/nature00813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fidock DA, Wellems TE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mamoun CB, Gluzman IY, Goyard S, Beverley SM, Goldberg DE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.