Abstract

DNA is subjected to many endogenous and exogenous damages. All organisms have developed a complex network of DNA repair mechanisms. A variety of different DNA repair pathways have been reported: direct reversal, base excision repair, nucleotide excision repair, mismatch repair, and recombination repair pathways. Recent studies of the fundamental mechanisms for DNA repair processes have revealed a complexity beyond that initially expected, with inter- and intrapathway complementation as well as functional interactions between proteins involved in repair pathways. In this paper we give a broad overview of the whole DNA repair system and focus on the molecular basis of the repair machineries, particularly in Thermus thermophilus HB8.

1. Introduction

It is essential for all living organisms to warrant accurate functioning and propagation of their genetic information. However, the genome is constantly exposed to various environmental and endogenous agents, which produce a large variety of DNA lesions (Figure 1) [1, 2]. Environmental damage can be induced by several chemical reactive species and physical agents. Endogenous damages occur spontaneously and continuously even under normal physiologic conditions through intrinsic instability of chemical bonds in DNA structure. The biological consequences of these damages usually depend on the chemical nature of the lesion. Most of these lesions affect the fidelity of DNA replication, which leads to mutations. Some of human genetic diseases are associated to defects in DNA repair (Table 1).

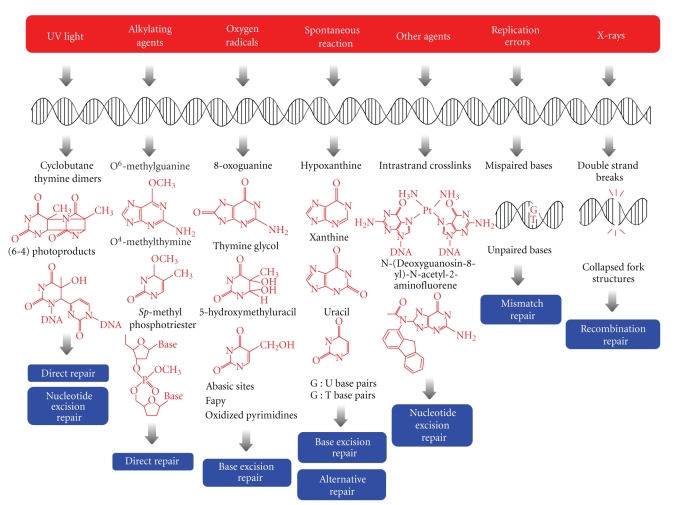

Figure 1.

Different repair systems for the principal types of DNA lesion produced by a wide range of factors. UV-light induces cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers or (6-4) photoproducts that are repaired by nucleotide excision repair and direct reversal systems. Alkylating agents can modify all of the bases and the phosphates of the DNA, and some repair proteins remove these alkyl adducts in a direct manner. Oxygen radicals modify DNA, and the base excision repair system acts to reverse these changes. The main cause of spontaneous mutation is deamination, and base excision repair and alternative repair systems remove the lesions. Other bulky adducts or interstrand cross-links are repaired by the nucleotide excision repair system. The mismatch repair pathway repairs replication errors. Double-strand breaks and four-way junctions are induced by X-rays and are repaired by recombinational repair.

Table 1.

Distribution of DNA repair genes. ∗1Related human diseases are listed by referencing the following databases: KEGG disease (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/disease/), GeneCards (http://www.genecards.org/), and Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim). ∗2Descriptions in the parentheses indicate the subunit organizations of holoenzymes.

| Repair pathways | Molecular functions | T. thermophilus | E. coli | S. cerevisiae | A. thaliana | M. musculus | H. sapiens | Related disease∗1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct reversal | ||||||||

| Photoreactivation | Photoreactivation | Phr (TTHB102) | PhrA | PHR1 | PhrB | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Alkyltransfer | Alkyltransfer or recognition | ATL (TTHA1564) | Ada, AGT, ATL | MGT1 | MGMT | MGMT | ||

| alkyltransfer | AlkB | AlkBH1 | ALKBH2, ALKBH3 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Base excision repair | ||||||||

| Base excision | Remove ring-saturated or fragmented pyrimidines | EndoIII (TTHA0112) | Nth (EndoIII) | Ntg1p, Ntg2p | AT1G05900 | Nthl1 | NTHL1 | |

| remove 3-meA, ethenoA, hypoxanthine | AlkA (TTHA0329) | AlkA, TagA | Mag1p | AT3G12040 (MAG) | Mpg | MPG, (MAG, AAG) | ||

| Remove U | UDGA (TTHA0718) | Ung | Ung1p | AT3G18630 uracil DNA glycosylase family protein | Ung | Ung | Hyper IgM syndromes, autosomal recessive type | |

| UDGB (TTHA1149) | ||||||||

| Remove U, hydroxymethyl U | Smug1 | SMUG1 | ||||||

| Remove U or T opposite G at CpG sequences | Mbd4 | MBD4 (MED1) | ||||||

| Remove U, T, or ethenoC opposite G | Mug | Tdg | TDG | |||||

| Remove 8-oxoG opposite C | MutM (TTHA1806) | Fpg (MutM) | Ogg1p | OGG1 | Ogg1 | OGG1 | Lung cancer | |

| Remove A opposite 8-oxoG | MutY (TTHA1898) | MutY | AT4G12740 (MYH-related) | MUTYH | MUTYH | |||

| Remove thymine glycol | Nei (EndoVIII) | Neil1 | NEIL1 | |||||

| Remove oxidative products of C, U | NEIL2 | |||||||

| Not known | NEIL3 | |||||||

| Alternative strand incision | Incision 3′ of hypoxanthine and uracil | EndoV (TTHA1347) | Nfi (EndoV) | EndoV | EndoV | EndoV | ||

|

| ||||||||

| AP site processing and resynthesis | AP endonuclease | EndoIV (Nfo) (TTHA0834) | Nfo (EndoIV) | Apn1p | ||||

| AP endonuclease | XthA (ExoIII) | Apn2p (Eyh1) | ARP | Apex1 | APEX1 (APE1, APEX, HAP1, REF1), | |||

| AP endonuclease | AT4G36050 | Apex2 | APEX2 | |||||

| gap-filling DNA polymerase | PolX (TTHA1150) | Polβ | Polβ | |||||

| DNA polymerase, 5′ flap endonuclease | PolI (TTHA1054) | PolI | ||||||

| replication and BER in mitochondrial DNA | Mip1p | Polγ | Polγ | |||||

| NAD-dependent DNA ligase | LigA (TTHA1097) | LigA | ||||||

| ATP-dependent DNA ligase | AT1G66730 (ATP-dependent) | Lig3 (ATP-dependent) | LIG3 (ATP-dependent) | |||||

| accessory factor for LIG3 and BER | AT1G80420 (putative XRCC1) | Xrcc1 | XRCC1 | |||||

| poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase | PARP2 | Parp1 | PARP1 (ADPRT) | |||||

| ADPRT-like enzyme | APP (Arabidopsis poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase) | Parp2 | PARP2 (ADPRTL2) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Nucleotide excision repair | ||||||||

| DNA binding | Bind damaged DNA in complex with UvrB | UvrA (TTHA1440) | UvrA | |||||

| Catalyze unwinding in preincision complex | UvrB (TTHA1892) | UvrB | ||||||

| Bind disordered DNA as complex | RAD4 | RAD4 | Xpc | XPC | Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) | |||

| Bind disordered DNA as complex | RAD23 | RAD23 | Rad23b (Hr23b) | RAD23B (HR23B) | ||||

| RAD23B paralog | Rad23a (Hr23a) | RAD23A (HHR23A) | ||||||

| Bind DNA and proteins in preincision complex | RAD14 | Xpa | XPA | XP, | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| TFIIH subunits | 3′-5′ DNA helicase TFIIH subunit | SSL2 (RAD25) | XPB2 | Xpb (Ercc3) | XPB (ERCC3) | XP, Cockayne syndrome (CS), Trichothiodystrophy (TTD) | ||

| 5′-3′ DNA helicase TFIIH subunit | RAD3 | UVH6 | Xpd (Ercc2) | ERCC2 | XP, CS, TTD | |||

| TFIIH subunit p62 | TFB1 | AT1G55750 | Gtf2h1 | GTF2H1 | ||||

| TFIIH subunit p44 | SSL1 | GTF2H2 | Gtf2h2 | GTF2H2 | ||||

| TFIIH subunit p34 | TFB4 | AT1G18340 | Gtf2h3 | GTF2H3 | ||||

| TFIIH subunit p52 | TFB2 | AT4G17020 | Gtf2h4 | GTF2H4 | ||||

| TFIIH subunit p8 | TFB5 | AT1G12400 | Gtf2h5 | GTF2H5 (TTDA) | TTD | |||

| Kinase subunits of TFIIH | KIN28 | CDKD1;3 | Cdk7 | CDK7 | ||||

| Kinase subunits of TFIIH | CCL1 | CYCH;1 | Ccnh | CCNH | ||||

| THIIH subunit | TFB3 | AT4G30820 | Mnat1 (Mat1) | MNAT1 (MAT1) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Strand incision and excision | 3′ and 5′ incision nuclease | UvrC (TTHA1548) | UvrC | |||||

| 3′ incision nuclease | Cho | |||||||

| 3′ incision nuclease | RAD2 | UVH3 | Xpg (Ercc5) | ERCC5 | XP, CS | |||

| 5′ incision nuclease subunits | RAD10 | ERCC1 | Ercc1 | ERCC1 | XP | |||

| 5′ incision nuclease subunits | RAD1 | UVH1 | Xpf (Ercc4) | ERCC4 | XP | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Separating two annealed strands | DNA helicase | UvrD (TTHA1427) | UvrD | |||||

| Other factors | Transcription- repair coupling factor | Mfd (TTHA0889) | Mfd | |||||

| Cockayne syndrome, needed for TC-NER | ERCC6 | Csb (Ercc6) | CSB (ERCC6) | CS, UV-sensitive syndrome (UVS) | ||||

| Cockayne syndrome, needed for TC-NER | AT1G19750 | Csa (Ckn1, Ercc8) | CSA (ERCC8) | CS | ||||

| P127 subunit of DDB | DDB1 | Ddb1 | DDB1 (XPE) | |||||

| P48 subunit of DDB, defective in XP-E | DDB2 | Ddb2 (Xpe) | DDB2 (XPE) | XP | ||||

| transcription and NER | AT5G48120 | Mms19 | MMS19 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Mismatch repair | ||||||||

| Mismatch recognition | DNA-binding ATPase | MutS (TTHA1324) | MutS | MutSα

(MSH2/MSH6) MutSβ (MSH2/MSH3) |

MutSα

(MSH2/MSH6) MutSβ (MSH2/MSH3) |

MutSα

(MSH2/MSH6) MutSβ (MSH2/MSH3) |

MutSα

(MSH2/MSH6) MutSβ (MSH2/MSH3) |

Colorectal cancer, Ovarian cancer |

|

| ||||||||

| Strand incision | Activation of MutL homologue | DNA polymerase III, β subunit (TTHA0001) | — | PCNA | PCNA | PCNA | PCNA | |

| Activation of MutL homologue | DNA polymerase III, δ, δ′, γ, τ subunits (TTHA0788, 1860, 1952) | RFC (RFC1-5)∗2 | RFC (RFC1-5)∗2 | RFC (RFC1-5)∗2 | RFC (RFC1-5)∗2 | |||

| Endonuclease ATPase | MutL (TTHA1323) | — | MutLα (MLH1/PMS1) MutLβ (MLH1/MLH2) MutLγ (MLH1/MLH3) | MutLα (MLH1/PMS1) MutLγ (MLH1/MLH3) | MutLα (MLH1/PMS2) MutLβ (MLH1/PMS1) MutLγ (MLH1/MLH3) | MutLα (MLH1/PMS2) MutLβ (MLH1/PMS1) MutLγ (MLH1/MLH3) | Colorectal cancer, Endometrial cancer, Ovarian cancer | |

|

| ||||||||

| Match making | ATPase | — | MutL | — | — | — | — | |

| Strand excision | 5′-3′ exonuclease | RecJ (TTHA1167) | RecJ | |||||

| 3′-5′ exonuclease | ExoI (TTHB178) | ExoI | ||||||

| 5′-3′ exonuclease | ExoVII | |||||||

| 3′-5′ exonuclease | ExoX | |||||||

| 5′-3′ exonuclease | EXO1 | AT1G29630 | Exo1 | EXO1 | ||||

| Single-stranded DNA binding protein | SSB (TTHA0244) | SSB | ||||||

| Single-stranded DNA binding protein complex | RFA (RFA1-3)∗2 | RPA (RPA1-3)∗2 | Rpa (Rpa1-3)∗2 | RPA (RPA1-3)∗2 | ||||

| DNA helicase | UvrD (TTHA1427) | UvrD | ||||||

| Recombination repair | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| End resection and recombinase loading | 5′-3′ exonuclease | RecJ (TTHA1167) | RecJ | |||||

| 5′-3′ exonuclease | EXO1 | AT1G29630 | Exo1 | EXO1 | ||||

| 5′-flap endonuclease | DNA2 | AT1G08840 | Dna2 | DNA2 | ||||

| RECQ family DNA helicase | RecQ | SGS1 | AT1G10930 (RECQ4A) | Blm | BLM | Bloom syndrome | ||

| Endonuclease, interact with MRN complex | SAE2 | AT3G52115 (ATGR1) | CtIP (Rbbp8) | CTIP (RBBP8) | ||||

| SMC-like ATPase, complex with SbcD (Mre11) | SbcC (TTHA1288) | SbcC | RAD50 | AT2G31970 (RAD50) | Rad50 | RAD50 | Nijmegen breakage syndrome-like disorder | |

| 3′-5′ exonuclease, endonuclease, complex with SbcC (Rad50) | SbcD (TTHA1289) | SbcD | MRE11 | AT5G54260 (MRE11) | Mre11a | MRE11A | Ataxia telangiectasia -like disorder | |

| Accessory protein for MR complex | XRS2 | AT3G02680 (NBS1) | Nbn (Nbs1) | NBN (NBS1) | Nijmegen breakage syndrome | |||

| SMC-like ATPase | RecN (TTHA1525) | RecN | ||||||

| Helicase/nuclease complex | RecB | |||||||

| Helicase/nuclease complex | RecC | |||||||

| Helicase/nuclease complex | RecD | |||||||

| 5′-3′ exonuclease | RecE | |||||||

| ssDNA annealing | RecT | |||||||

| Single-stranded DNA binding protein | SSB (TTHA0244) | Ssb | ||||||

| Single-stranded DNA binding protein complex | RFA (RFA1-3) | RPA (RPA1-3) | Rpa (Rpa1-3) | RPA (RPA1-3) | ||||

| ATPase, complex with RecR | RecF (TTHA0264) | RecF | ||||||

| Recombinase mediator, ssDNA annealing | RecO (TTHA0623) | RecO | ||||||

| DNA binding, complex with RecF and RecO | RecR (TTHA1600) | RecR | ||||||

| Recombinase mediator, ssDNA annealing | Rad52-like (TTHA0081) | RAD52 | Rad52 | RAD52 | ||||

| Recombinase mediator | AT5G01630 (BRCA2B) | Brca2 | BRCA2 | Pancreatic cancer, Ovarian cancer, Breast cancer, Fanconi anemia | ||||

| RAD54 family DNA translocase, recombinase mediator | RAD54 | AT3G19210 (ATRad54) | Rad54l | RAD54L | Adenocarcinoma, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | |||

| RAD54 family DNA translocase, recombinase mediator | RDH54 | Rad54b | RAD54B | Colon cancer, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | ||||

| RAD51-like, recombinase mediator | AT5G64520 (XRCC2) | Xrcc2 | XRCC2 | Breast cancer | ||||

| RAD51-like, recombinase mediator | AT5G57450 (XRCC3) | Xrcc3 | XRCC3 | Breast cancer, Melanoma | ||||

| RAD51-like, recombinase mediator | RAD57 | AT2G28560 (RAD51B) | Rad51l1 | RAD51L1 | Uterine leiomyoma | |||

| RAD51-like, recombinase mediator | AT2G45280 (RAD51C) | Rad51c | RAD51C | Fanconi anemia-like disorder, Breast-Ovarian cancer | ||||

| RAD51-like, recombinase mediator | RAD55 | AT1G07745 (RAD51D) | Rad51l3 | RAD51L3 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Strand exchange | Recombinase | RecA (TTHA1818) | RecA | AT2G19490 (recA) | ||||

| Recombinase | RAD51 | AT5G20850 (ATRAD51) | Rad51 | RAD51 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Branch migration | Branch migration complex | RuvA (TTHA0291) | RuvA | |||||

| Branch migration complex | RuvB (TTHA0406) | RuvB | ||||||

| DNA helicase | RecG (TTHA1266) | RecG | AT2G01440 (RecG) | |||||

| RecA-like ATPase | RadA/Sms (TTHA0541) | RadA/Sms | AT5G50340 | |||||

| RAD54 family DNA translocase, recombinase mediator | RAD54 | AT3G19210 (ATRad54) | Rad54l | RAD54L | Adenocarcinoma, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | |||

| RAD54 family DNA translocase, recombinase mediator | RDH54 | Rad54b | RAD54B | Colon cancer, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | ||||

| RECQ family DNA helicase | RecQ | SGS1 | AT1G10930 (RECQ4A) | Blm | BLM | Bloom syndrome | ||

| RECQ family DNA helicase | Wrn | WRN | Werner syndrome | |||||

| RECQ family DNA helicase | AT1G31360 (RECQL2) | Recql | RECQL | |||||

| RECQ family DNA helicase | MPH1 | AT1G35530 | Fancm | FANCM | Fanconi anemia | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Holliday junction resolution | HJ resolvase | RuvC (TTHA1090) | RuvC | |||||

| HJ resolvase | RusA | |||||||

| HJ resolvase | YEN1 | AT1G01880 | Gen1 | GEN1 | ||||

| Structure-specific endonuclease | MUS81 | AT4G30870 (MUS81) | Mus81 | MUS81 | ||||

| complex with MUS81 | MMS4 | AT2G22140 (ATEME1B) | Eme1 | EME1 | ||||

| Structure-specific endonuclease | RAD1 | AT5G41150 (UVH1) | Ercc4 | ERCC4 | Xeroderma pigmentosum | |||

| complex with ERCC4 (RAD1) | RAD10 | AT3G05210 (ERCC1) | Ercc1 | ERCC1 | Cerebro-oculo-facio-skeletal syndrome | |||

| HJ resolvase | SLX1 | AT2G30350 | Slx1 (Giyd2) | SLX1 (GIYD2) | ||||

| Accessory protein for structure-specific nucleases | SLX4 | Slx4 (Btbd12) | SLX4 (BTBD12) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Anti-recombination | Recombinase inhibitor | RecX (TTHA0848) | RecX | AT3G13226 (RecX) | ||||

| DNA helicase | UvrD (TTHA1427) | UvrD | SRS2 | AT4G25120 | ||||

| Structure-specific endonuclease | MutS2 (TTHA1645) | AT1G65070 (MutS2) | ||||||

To cope with these DNA damages, all organisms have developed a complex network of DNA repair mechanisms [1, 3]. A variety of different DNA repair pathways have been reported: direct reversal, base excision repair, nucleotide excision repair, mismatch repair, and recombination repair pathways. Most of these pathways require functional interactions between multiple proteins. Furthermore, recent studies have revealed inter- and intra-pathway complementation.

Although there are a number of model organisms representing different kingdoms, such as Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Mus musculus (Table 1), we selected the bacterial species Thermus thermophilus HB8 for use in our studies of basic and essential biological processes. T. thermophilus is a Gram-negative eubacterium that can grow at temperatures over 75°C [4]. T. thermophilus HB8 was chosen for several reasons: (i) it has a smaller genome size than other model organisms; (ii) proteins from T. thermophilus HB8 are very stable suitable for in vitro analyses of molecular function; and (iii) the crystallization efficiency of the proteins is higher than for those of other organisms [5]. Moreover, since each biological system in T. thermophilus is only constituted of fundamentally necessary enzymes, in vitro reconstitution of a particular system should be easier and more understandable.

Our group has constructed overexpression plasmids for most T. thermophilus HB8 ORFs [6], and those plasmids are available from The DNA Bank, RIKEN Bioresource Center (Tsukuba, Japan) (http://www.brc.riken.jp/lab/dna/en/thermus_en.html). Approximately 80% of the ORFs have been completely cloned into the overexpression vectors pET-11a, pET-11b, pET-3a, and/or pET-HisTEV. Furthermore, plasmids for gene disruption are also available from the Structural-Biological Whole Cell Project (http://www.thermus.org/). Protein purification profiles and gene disruption methods can be downloaded from the RIKEN Bioresource Center. Therefore, it is a relatively simple matter to initiate an analysis of proteins of interest in this species.

T. thermophilus HB8 has all of the fundamental enzymes known to be essential for DNA repair, and most of these show homology to human enzymes. Biological and structural analyses of DNA repair in T. thermophilus will therefore provide a better understanding of DNA repair pathways in general. Moreover, these analyses are aided by the high efficiency of protein crystallization and stability of purified proteins in this species. In this paper we give a broad overview of the whole DNA repair system and focus on the molecular basis of the repair machineries, especially in T. thermophilus HB8.

2. Direct Reversal of DNA Damage

UV-induced pyrimidine dimers and alkylation adducts can be directly repaired by DNA photolyases and alkyl transferases, respectively. These repair systems are not followed by incision or resynthesis of DNA.

2.1. Photolyases

UV-induced pyrimidine dimers, such as cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) and (6-4) photoproducts, disturb DNA replication and transcription. Some species make use of DNA photolyases to repair these lesions (Figure 2(a)). The FADH− in the photolyase donates an electron to the CPD, which induces the breakage of the cyclobutane bond [7].

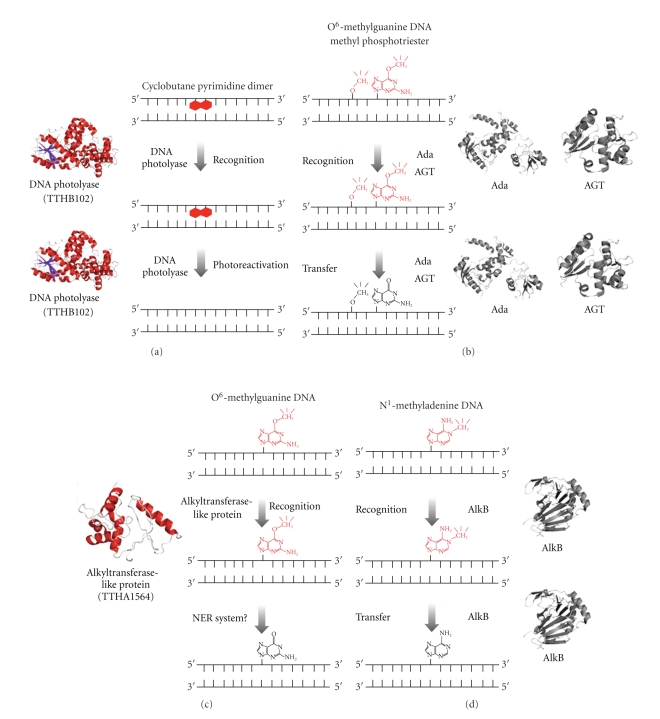

Figure 2.

A schematic representation of models for direct reversal of DNA damage. The structure of the ATL proteins was modeled by SWISS-MODEL (the template structure is Sulfolobus tokodaii Ogt) [19, 20]. AGT, Ada, and AlkB are not conserved in T. thermophilus. (a) Cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers are recognized by photolyase (TTHB102; PDB ID: 1IQR) and repaired by photolyase. (b) O 6-methylguanines are recognized by AGT (PDB ID: 1EH6) in most species and by the C-terminal domain of Ada (PDB ID: 1SFE) in E. coli. Methyl phosphotriesters are recognized by the N-terminal domain of Ada (PDB ID: 1WPK) in E. coli. These enzymes directly accept a methyl group, and the alkyl adducts are removed from the DNA. (c) O 6-alkyl adducts including O 6-methylguanines are recognized by ATL proteins (TTHA1564; predicted model) in several species. It is predicted that NER proteins are involved in this pathway after recognition of the adducts by ATL proteins. (d) N 1-methyladenines and N 3-methylcytosines are recognized by AlkB (PDB ID: 2IUW). Methyl group transfer by AlkB depends on α-ketoglutarate and Fe(II).

CPD photolyases repair UV-induced CPDs utilizing photon energy from blue or near-UV light [8]. To absorb light, CPD photolyases have two different chromophoric cofactors. One of these, FAD, acts as the photochemical reaction center in the repair process. An electron is transferred from an exogenous photoreductor to FAD, which is changed to the fully reduced, active form FADH− [9]. Although only this chromophore is necessary for the reaction, photolyases have a second chromophore as an auxiliary antenna to harvest light energy, which is transferred to the reaction center. The identity of the second chromophore differs among species. To date, reduced folate (5,10-methenyl-tetrahydrofolate, MTHF), 8-hydroxy-5-deazaflavin (8-HDF), FMN, and riboflavin have been identified as secondary chromophores.

A CPD photolyase (ORF ID, TTB102) of T. thermophilus (ttPhr) was identified as the first thermostable photolyase in 1997 [10]. The crystal structures of photolyases from E. coli and Aspergillus nidulans were reported in 1995 and 1997, respectively [11, 12]. Those of ttPhr and the complex it forms with thymine, a part of its substrate, were reported in 2001 [13]. NMR analysis showed that the CPD is flipped out from the double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) into a cavity in ttPhr [14]. Likewise, the thymine dimer interacts with the active site in the crystal structure of A. nidulans photolyase complexed with substrate dsDNA [15]. NMR analysis also showed the distance between FAD and CPD, which is important for understanding the CPD repair reaction by ttPhr [16]. In 2005, an overexpression analysis using E. coli identified the second chromophore of ttPhr as FMN [17]. Photolyases usually have a specific binding site for cofactors, but the second chromophore, FMN, of ttPhr shows promiscuous binding with riboflavin or 8-HDF [18].

Placental mammals lack photoreactivation activity, but they do have nucleotide excision repair (NER) systems for repairing CPDs [21]. NER has two sub-pathways: global genomic repair (GGR) and transcription-coupled repair (TCR) [3]. These sub-pathways are versatile repair systems and are highly conserved across species. Thus, the absence of photoreactivation activity would not have a significant effect on DNA repair efficiency in placental mammals. The mechanisms of NER are detailed in the later section. It should be noted that mammals, birds, and plants have photolyase-like proteins, the so-called cryptochromes, which have no ability to repair damaged DNA but function as blue-light photoreceptors [22].

2.2. Reversal of O 6-Alkylguanine-DNA

O 6-alkylguanine is one of the most harmful alkylation adducts and can induce mutation and apoptosis [23–25]. Almost all species possess mechanisms to repair this adduct (Figures 2(b) and 2(c)). O 6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase (AGT) accepts an alkyl group on a cysteine residue at its active site (PCHR) in a stoichiometric fashion, and this alkylated AGT is inactive (Figure 2(b)) [26–28]. AGT acts as a monomer and transfers the alkyl group from DNA without a cofactor [29–31]. The structure of human AGT, MGMT, indicates that a helix-turn-helix motif mediates binding to the minor groove of DNA and that O 6-methylguanine (O 6-meG) is flipped out from the base stack into this active site [32, 33]. Tyrosine and arginine residues in the active site of the enzyme mediate nucleotide flipping.

The cysteine residue in the active site (PCHR) of AGT is necessary for the methyltransferase activity. Some AGT-like proteins lack cysteine residues in their active sites (PXHR) [34–40]. Alkyltransferase-like (ATL) proteins are a type of AGT homologue and are present in all three domains of life. ATL proteins from E. coli, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and T. thermophilus can bind to DNA and show preferential binding to O 6-meG-containing DNA, but they are unable to transfer a methyl group from the modified DNA [37–39]. This binding activity inhibits AGT activity in a competitive manner [38]. E. coli has three AGT homologues, AGT, Ada, and the ATL protein, but S. pombe and T. thermophilus have only the ATL protein. Therefore, S. pombe or T. thermophilus are particularly suitable for studies of ATL proteins.

The tyrosine and arginine residues involved in base flipping are also conserved in ATL proteins. A fluorescence assay of the T. thermophilus ATL protein (TTHA1564) suggested that it can also recognize O 6-meG and flips out the target residue into its active site (Figure 2(c)) [37]. The crystal and NMR structures of ATL proteins indicate that the O 6-meG residue is flipped out from the base stacks into the active site [34, 40]. Mutational analysis demonstrated that the tyrosine and arginine residues of ATL proteins are also involved in base flipping [34].

A comparison of their 3D structures showed that the lesion-binding pocket of ATL proteins is approximately three times larger than that of AGTs [34, 40]. The S. pombe ATL protein (Atl1) can bind to the bulky O 6-adduct, O 6-4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobutylguanine (O 6-pobG), with higher affinity than to O 6-meG [34]. Additionally, AGT repairs O 6-pobG with lower efficiency than O 6-meG. In species that have both AGT and ATL protein, for example, E. coli, it is possible that AGT repairs O 6-meG while the ATL protein is involved in the repair of bulky O 6-adducts such as O 6-pobG.

It is known that the action of ATL proteins is linked with the NER pathway (Figure 2(c)) [34, 36, 37, 40]. The ATL protein of T. thermophilus, TTHA1564, can interact with UvrA, while that of E. coli can interact with UvrA and UvrC [36, 37, 40]. MNNG caused an increased mutation frequency in the ttha1564-deficient mutant compared with the wild type (unpublished data). Genetic analysis of S. pombe Atl1 showed that atl1 is epistatic to rad13 (the fission yeast orthologue of human ERCC5) and swi10 (the ERCC1 orthologue) but not to rhp14 or rad2 for N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) toxicity [40]. Analyses of the spontaneous mutation rate of rad13 and rad13 atl mutants suggested that ATL-DNA complexes block an alternative repair pathway probably because ATL proteins form a highly stable complex with DNA in the absence of Rad13 or other NER proteins [40]. However, the mechanism by which ATL proteins repair lesions in collaboration with NER proteins is not well understood.

The protein Ada repairs alkylated lesions in the same manner as AGTs in E. coli (Figure 2(b)) [27]. The amino acid sequence and the molecular function of the C-terminal domain of Ada (C-Ada) show similarity to those of AGTs. The N-terminal domain of Ada (N-Ada) can repair a methyl phosphotriester lesion in DNA in vitro [44]. Methylated N-Ada specifically binds to the promoter region of the ada-alkB operon and the alkA and aidB genes and C-Ada can bind to RNA polymerase [45, 46]. Thus, the methylated Ada acts as a transcriptional activator.

2.3. AlkB

AlkB homologues are conserved in many organisms including humans and E. coli. As described above, alkB is one of the genes regulated by Ada. AlkB requires α-ketoglutarate and Fe(II) as cofactors to repair N 1-methyladenine or N 3-methylcytosine via an oxidative demethylation mechanism [46]. These properties are consistent with the fact that AlkB has sequence motifs in common with 2-oxoglutarate and iron-dependent dioxygenases (Figure 2(d)) [47]. AlkB oxidizes the methyl group using nonheme Fe2+, O2, and α-ketoglutarate to restore undamaged bases with subsequent release of succinate, CO2, and formaldehyde. The detailed mechanisms of substrate recognition and catalysis were identified by structural and mutational analyses.

Eight AlkB homologues are known in humans, [48] and, of these, ALKBH1, ALKBH2, and ALKBH3 have been identified as repair enzymes, each of which has a different substrate specificity [49, 50]. E. coli AlkB can repair a lesion in both single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and dsDNA, whereas ALKBH3 repairs lesions only in ssDNA. ALKBH1 and ALKBH2 can act only on DNA whereas E. coli AlkB and ALKBH3 can act on both DNA and RNA [51]. The crystal structures of AlkB-dsDNA and ALKBH2-dsDNA complexes explain distinct preferences of AlkB homologues for substrates [51]. Cell cycle-dependent subcellular localization experiments suggested that ALKBH2 and ALKBH3 repair mainly newly synthesized DNA and mRNA, respectively, and withhold demethylation of modified rRNA or tRNA.

3. Base Excision Repair

DNA is altered and damaged by various endogenous and exogenous reactions [52]. With regard to endogenous reactions, deamination of cytosine, adenine and guanine produce uracil, hypoxanthine, and xanthine, respectively. Depurination and depyrimidination result in the formation of an apurinic/apyrimidinic site (AP site). Reactive oxygen species (ROSs) convert guanine to 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine (8-oxoguanine, 8-oxoG, or its isomeric form 8-hydroxyguanine) and purine bases to 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine (FaPyG) and 4,6-diamino-5-formamidopyrimidine (FaPyA). Thymine glycol, cytosine hydrates, and etheno adducts of adenine, cytosine, and guanine are also generated as a result of oxygen damage. DNA replication errors also introduce lesions into the DNA. For example, DNA polymerases sometimes incorporate mismatched bases or damaged nucleotides (such as dUMP and 8-oxo-dGMP) [53–55]. With regard to exogenous reactions, DNA is susceptible to damage by agents such as UV radiation and alkylating compounds. The lesions caused by endogenous and exogenous reactive species can be repaired through the base excision repair (BER) pathway described below.

3.1. General Mechanism of BER

BER is probably the most frequently used DNA repair pathway in the cell (Figure 3, Table 1) [56, 57]. Bases damaged as described above are specifically recognized by various DNA glycosylases to initiate BER [58]. Monofunctional DNA glycosylases catalyze the hydrolysis of N-glycosyl bonds and generate an AP site. Bi- and trifunctional DNA glycosylases have AP lyase activity via a β- or β/δ-elimination mechanism using an ε amino group of a lysine residue or α-imino group in addition to DNA glycosylase activity [59]. However, it is still unclear whether this lyase activity is the primary in vivo mechanism. AP sites are targeted by both AP endonuclease and AP lyase. AP endonuclease nicks an AP site through a hydrolytic reaction to generate a 3′-OH and 5′-deoxyribosephosphate (dRP) [60–62]. This 5′ block is removed by deoxyribophosphodiesterase (dRPase) or dRP lyase using hydrolytic or lyase (β-elimination) mechanisms, respectively [63–65]. When the AP lyase incises an AP site, it produces 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde (by β-elimination) or 3′-phosphate (by β/δ-elimination) and 5′-phosphate [66]. These 3′-blocking groups must be removed by 3′-phosphoesterase to allow DNA polymerase activity. A one-nucleotide gap typically remains after AP site processing. When repair synthesis is performed by incorporation of a single nucleotide, this pathway is called single nucleotide-BER (SN-BER) [67]. Some DNA polymerases can synthesize DNA of more than 2 bases by strand displacement activity, followed by cleaving flap DNA via flap endonuclease activity. This pathway is called long-patch BER (LP-BER) [67]. In both pathways, the resulting nick is sealed by DNA ligase.

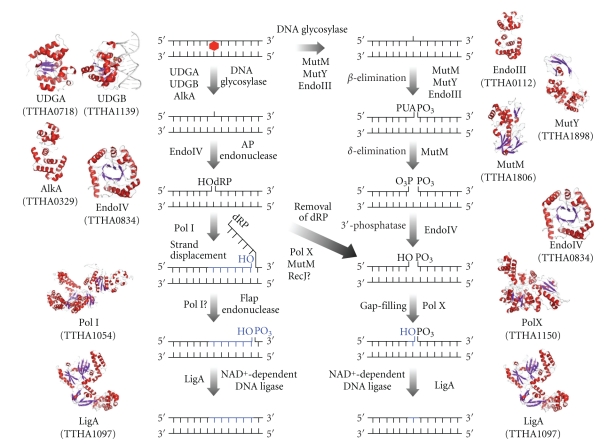

Figure 3.

General mechanism of the BER pathway in T. thermophilus. UDGA, UDGB, and AlkA are monofunctional DNA glycosylases. UDGA (PDB ID: 1UI0) and UDGB (PDB ID: 2DDG) remove uracil from DNA. AlkA removes 3-methyladenine in E. coli. MutY and EndoIII are bifunctional DNA glycosylases and have both DNA glycosylase and AP lyase activities. MutY removes adenine opposite 8-oxoG, and EndoIII removes pyrimidine residues damaged by ring saturation, fragmentation, and contraction [41], by which 3′-phospho α,β-unsaturated aldehyde (3′-PUA) remains. MutM (PDB ID: 1EE8) is a trifunctional DNA glycosylase that removes 8-oxoG from oxidatively damaged DNA and 3′-phosphate remains. An AP site resulting from DNA glycosylase activity is processed by EndoIV or multifunctional DNA glycosylases. EndoIV has both AP endonuclease activity and 3′-esterase activity in E. coli [42, 43]. PolX or MutM removes 5′-dRP by dRP lyase activity. In addition, 5′-3′ exonuclease (RecJ) may have dRPase activity. The resulting gap is filled by PolI or PolX followed by sealing of the nick by LigA. The structures of AlkA, EndoIII, MutY, PolI, PolX, and LigA were obtained using SWISS-MODEL [19, 20] (PDB ID: 2H56, 2ABK, 3FSP, 1TAU, 2W9M, and 1V9P, resp.) based on amino acids sequences of T. thermophilus HB8.

3.2. BER in T. thermophilus

The T. thermophilus HB8 genome contains the genes for all the fundamental BER enzymes. The genome includes the following monofunctional DNA glycosylases: 3-methyl-adenine DNA glycosylase, TTHA0329 (ttAlkA); uracil DNA glycosylase A, TTHA0718 (ttUDGA); uracil DNA glycosylase B, TTHA1149 (ttUDGB). It also includes the following bifunctional DNA glycosylases: endonuclease III (Nth), TTHA0112 (ttEndoIII); adenine DNA glycosylase, TTHA1898 (ttMutY); formamidopyrimidine DNA glycosylase, TTHA1806 (ttMutM). AP endonucleases are classified on the basis of their structure as members of either the exonuclease III family or the endonuclease IV (Nfo) family. The only AP endonuclease in T. thermophilus is the EndoIV, TTHA0834 (ttEndoIV); a similar restriction occurs in other bacterial and archaeal species. T. thermophilus has been found to have two DNA polymerases, TTHA1054 (ttPolI) and TTHA1150 (ttPolX), and an NAD+-dependent DNA ligase, TTHA1097 (ttLigA). The crystal structures of ttUDGA [68], ttUDGB [69], ttMutM [70], and ttEndoIV (unpublished data) have been determined.

Uracil-DNA glycosylases (Ungs or UDGs) remove uracil from DNA by cleaving the N-glycosylic bond. These enzymes are classified into several families on the basis of similarities in their amino acid sequences [71, 72]. T. thermophilus HB8 has two Ungs that belong to families 4 (ttUDGA) and 5 (ttUDGB). ttUDGA removes uracil from not only U : G but also U : C, U : A, and U : T and can also remove uracil from ssDNA. Moreover, the crystal structure of ttUDGA with uracil indicates that the mechanism by which family 4 Ungs remove uracils from DNA is similar to that of family 1 enzymes [68]. The crystal structures of apo-form ttUDGB and ttUDGB complexed with AP site containing DNA have been solved [69]. The active site structures suggest that this enzyme uses both steric force and water activation for its excision reaction. Based on the absence of a significant open-closed conformational change upon binding to DNA, it was proposed that Ungs recognize the damaged base by sliding along the target-containing strand [69].

MutM is a trifunctional DNA glycosylase which removes 8-oxoG from oxidatively damaged DNA [73]. ttMutM was cloned, characterized, and crystallized. Based on crystal structure and biochemical experiments of ttMutM, DNA-binding mode and catalytic mechanism of MutM were proposed [70].

In mammalian cells, SN-BER is the principal BER sub-pathway and is catalyzed mainly by Polβ [74, 75]. Nevertheless, LP-BER also occurs in vivo [76]. The selection of which sub-pathway to use is dependent on the nature of the damaged base, the 5′-blocking structure, and the enzymes involved [74, 77–82]. Bacteria have both SN- and LP-BER pathways [83]. Bacterial PolIs, including ttPolI, have strand displacement [84] and flap endonuclease-like activities (structure-specific 5′-nuclease activity) [85–89]. Therefore, PolI is probably the main DNA polymerase in bacterial LP-BER. Furthermore, the fact that the β-clamp, the β subunit of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme, interacts with some DNA repair enzymes, such as PolI and LigA [90], indicates that it is possibly involved in bacterial LP-BER in a similar manner to mammalian PCNA clamp [77].

Many bacteria have PolX, which belongs to the X-family DNA polymerases; the mammalian homologues of this enzyme are Polβ, Polλ, Polμ, TdT, and Polσ [91]. PolXs can efficiently fill a short DNA gap in mammals [79, 92] and bacteria [93] and are therefore thought to be the main DNA polymerases in the SN-BER pathway [74, 75, 94]. Although PolX is conserved in many bacteria, including T. thermophilus, E. coli does not have this enzyme. Therefore, T. thermophilus has an advantage as a model organism in understanding human and bacterial BER. ttPolX has two principal active regions, the N-terminal POLX core (POLXc) domain and the C-terminal polymerase and histidinol phosphatase (PHP) domain. These domains are conserved in many bacteria, but eukaryotic PolXs lack the PHP domain. Furthermore, it is thought that only PHP domain-containing PolXs have 3′-5′ exonuclease activity [95, 96]. The PHP domain has nine catalytic residues and is mainly responsible for the nuclease activity; however, the POLXc domain is also needed for this activity [97]. Although the PHP domain is thought to have a phosphoesterase activity, details of the function of the PHP domain remain to be clarified. Bacterial PolXs may play more than two roles in the BER pathway whereas these functions might be performed in eukaryotes by two or more separate enzymes. Identifying the role of the PHP domain of bacterial PolXs in BER will be important for understanding both bacterial and eukaryotic BERs.

3.3. Eukaryotic-Specific BER Enzymes

Eukaryotes have many functional homologues of bacterial BER enzymes, and the mechanism of BER is similar to that of prokaryotes. However, eukaryotes also have specific BER enzymes. To date, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and X-ray cross-complementing group 1 (XRCC1) have been identified as eukaryotic-specific enzymes. PARP1 uses NAD to add branched ADP-ribose chains to proteins. PARP1 functions as a DNA nick-sensor in DNA repair and as a negative regulator of the activity of Polβ in LP-BER [98]. XRCC1 interacts with DNA ligase III and PARP through its two BRCT domains and with Polβ through an N-terminal domain. XRCC1 also interacts with many other proteins and forms a large DNA repair complex [99, 100].

4. Nucleotide Excision Repair

Nucleotide excision repair (NER) is one of the most important repair systems and is conserved from prokaryotes to higher eukaryotes [101, 102]. The most important feature of the NER system is its broad substrate specificity: NER can excise DNA lesions such as UV-induced pyrimidine dimers or more bulky adducts [103].

In the prokaryotic NER system, recognition and excision of DNA lesions are mediated by UvrABC excinucleases (Figure 4) [101, 102]. After the incision event, UvrD helicase removes the nucleotide fragment, PolI synthesizes the complementary strand, and then DNA ligase completes the repair process. NER has two sub-pathways, global genomic repair (GGR) and transcription-coupled repair (TCR) [104, 105]. In GGR, recognition of DNA lesions by UvrAB initiates the initiation of the repair reaction, whereas, in TCR, stalling of the RNA polymerase is responsible for the initiation of repair [106]. When a transcribing RNA polymerase meets a bulky DNA lesion, the polymerase stalls. Transcription-repair coupling factor (TRCF) releases the stalled RNA polymerase from the template DNA and then recruits UvrA. After UvrA has bound to the DNA, the subsequent reactions proceed in the same fashion as in GGR.

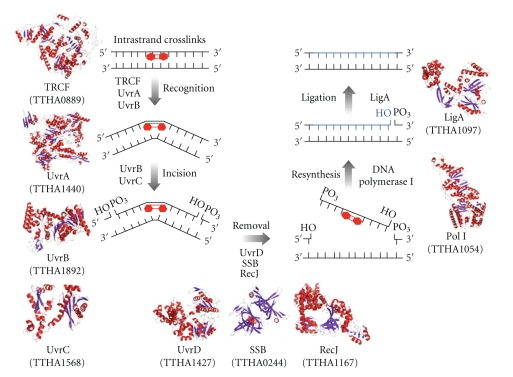

Figure 4.

A schematic representation of models for the nucleotide excision repair pathway controlled by Uvr proteins. All of the predicted protein structures were modeled using SWISS-MODEL. The template structures used in the model building were Geobacillus stearothermophilus UvrA, the N- and C-terminal domain of Thermotoga maritime UvrC, G. stearothermophilus UvrD, Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase I, Thermus filiformis DNA ligase, and E. coli TRCF. UvrA (TTHA1440; predicted model) and UvrB (TTHA1892; PDB ID: 1D2M) recognize the DNA lesion. In transcribing strand, TRCF (TTHA0889; predicted model) is also involved in recognition of the lesion. UvrC (TTHA1568; predicted model) incises both sides of the lesion. The DNA fragment containing the lesion is excised by UvrD (TTHA1427; predicted model), SSB (TTHA0244; 2CWA), and exonuclease RecJ (TTHA1167; PDB ID: 2ZXO). A new strand is resynthesized by DNA polymerase I (TTHA1054; predicted model) and ligated by DNA ligase (TTHA1097; predicted model).

Most eukaryote species, including humans, possess an NER system. The amino acid sequences of the proteins that act in eukaryotic NER are very different from those of bacterial proteins, but the functions of these proteins are nevertheless similar [101]. The molecular mechanism of NER is more complicated in eukaryotes than bacteria. The eukaryotic NER pathway involves more than ten proteins, including some that are functional homologues of those required for bacterial NER [107].

4.1. Global Genomic Repair (GGR)

Bacterial GGR is a multistep process that removes a wide variety of DNA lesions. In solution, UvrA and UvrB form UvrA2B or UvrA2B2 that can recognize lesions in DNA and can make a stable complex with the DNA [108, 109]. When UvrB detects a lesion, it hydrolyzes ATP to form the pro-preincision complex. After UvrA is released, UvrB binds tightly to DNA and makes a stable UvrB-DNA complex, that is, a pre-incision complex. In this state, UvrB hydrolyzes ATP and can then specifically recognize damage in the absence of UvrA [110]. In E. coli, UvrB can hydrolyze ATP in this step with UvrA but not without UvrA [111]. In T. thermophilus HB8, the UvrB protein (ttUvrB; TTHA1892) shows ATPase activity at its physiological temperature even in the absence of UvrA (ttUvrA; TTHA1440) [112, 113]. Finally, a new pre-incision complex is formed by binding new ATP [110]. UvrC can bind to the pre-incision complex to incise both sides of a DNA lesion. The first incision is made at the fourth or fifth phosphodiester bond on the 3′ side of the lesion and is immediately followed by incision at the eighth phosphodiester bond on the 5′ side [114, 115]. The catalytic sites for 3′ and 5′ incisions are located in different domains of UvrC. It has been reported that the expression levels of uvrA and uvrB are approximately three times higher than that of uvrC (ttha1548) in T. thermophilus [116].

UvrD is a DNA helicase that releases lesion-containing DNA fragments from dsDNA. The purification and characterization of UvrD from T. thermophilus (ttUvrD; TTHA1427) have been reported [117]. After removing the nucleotide fragment, PolI synthesizes a new strand with the same sequence as the removed nucleotide fragment. The newly synthesized sequence is ligated to the adjacent strand by DNA ligase, and all of the repair steps are completed.

4.2. Transcription-Coupled Repair (TCR)

Bacterial TCR is a highly efficient NER system. In 1985, it became apparent that the DNA lesion in the transcribed strand is preferentially repaired [118]. The first consequence of this mechanism is that a stalled RNA polymerase interacts with UvrA with high affinity. Interestingly, however, a stalled RNA polymerase interrupts the NER repair system in vitro [119]. Hence, it was suspected that an unknown factor must release the stalled RNA polymerase and recruit NER proteins. Selby et al. showed in E. coli that the gene product (transcription-repair coupling factor, TRCF) of the mfd gene is the factor involved [106, 120].

TRCF can release a stalled elongation complex but not an initiation complex [106]. The activity for releasing an elongation complex is dependent on ATP hydrolysis. After the complex is released, TRCF can recruit UvrA to the DNA lesion. TRCF has a UvrB homology module, which interacts with UvrA [106, 121]. After recruiting UvrA to the DNA lesion, the subsequent reactions are the same as in GGR. UvrB and DNA form a pre-incision complex, and then UvrC incises both sides of the DNA strand.

The broad substrate specificity of TCR is similar to that of GGR, but TCR repairs lesions with a higher efficiency [106]. In TCR, UvrA can be more rapidly directed to the DNA lesion because the stalled RNA polymerase and TRCF mediate binding of UvrA, whereas, in GGR, UvrA needs to search for DNA lesions across the whole genome without the aid of cofactors. An increased efficiency in finding the substrate also increases the efficiency of the repair system.

4.3. Crystal Structures and Functions of Key Enzymes

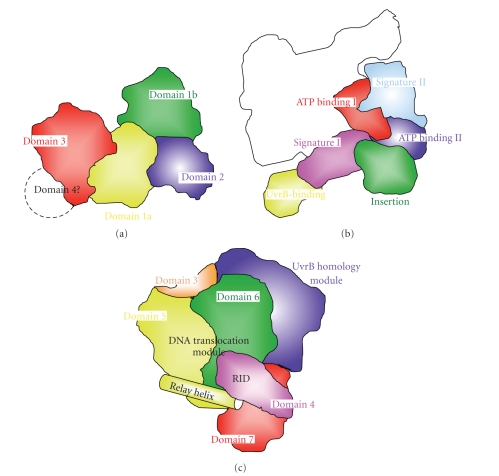

The overall crystal structures of UvrA, UvrB, and TRCF and the two domains of UvrC were determined some years ago [122–128]. In 1999, UvrB was the first of the proteins involved in NER to have its crystal structure established [124, 125, 127]. Later, in 2006, the 3D structure of the UvrB-DNA complex was reported [129]. It was suggested by limited proteolysis that ttUvrB is comprised of four domains, whereas analysis of the 3D structure identified five domains, 1a, 1b, 2, 3, and 4 (Figure 5(a)) [125, 130]. Domain 2 interacts with UvrA, and domain 4 interacts with both UvrA and UvrC. Domains 1a and 3 contain helicase motifs and share high structural similarity to the DNA helicases NS3, PcrA, and Rep. The flexible β-hairpin-connecting domains 1a and 1b are predicted to play important roles in DNA binding. The structure of the UvrB-DNA complex shows that the nucleotide directly behind the β-hairpin is flipped out and inserted into a small pocket in UvrB [129].

Figure 5.

The domain architectures of UvrB, UvrA, and TRCF. (a) UvrB is comprised of five domains. Domains 1a (yellow) and 3 (red) contain helicase motifs. Domain 1b (green) has the flexible β-hairpin invosved in substrate recognition. Domain 2 (blue) interacts with UvrA. Domain 4 is disordered in the crystal structures. (b) UvrA is comprised of six domains: ATP-binding I (red), ATP-binding II (blue), signature I (pink), signature II (cyan), UvrB-binding (yellow), and insertion (green) domain. The white region is the other subunit of the dimer. (c) TRCF is comprised of seven domains. Domains 1 and 2 (not separated in the figure) comprise UvrB homology module (blue). Domains 5 (yellow) and 6 (green) comprise DNA translocation module. Relay helix (yellow) interacts with domain 4 (pink), RNA polymerase interaction domain (RID). The functions of domain 3 (orange) and domain 7 (red) are unclear.

The crystal structures of the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of UvrC were reported in 2005 and 2007, respectively, but the 3D structure of the interdomain loop and of full-length UvrC is still unclear [123, 128]. The N-terminal domain of UvrC catalyzes the 3′ incision reaction and shares homology with the catalytic domain of GIY-YIG family endonucleases. The C-terminal domain of UvrC is responsible for the 5′ incision [123]. It includes an endonuclease domain and an (HhH)2 domain. Despite the lack of sequence homology, the endonuclease domain has an RNase H-like fold. We established the methods of purification of UvrC from T. thermophilus (ttUvrC; TTHA1568), and Hori et al. developed an in vitro reconstitution system of NER using purified ttUvrA, ttUvrB, and ttUvrC [131]. The ttUvrABC system can recognize a (6-4) thymine dimer and excise the affected strand; however, it does not excise a strand containing 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanine or 2-hydroxy-2′-deoxyadenine [131].

The overall structure of UvrA was reported in 2008 [126]. UvrA is comprised of six domains: ATP-binding I, signature I, ATP-binding II, signature II, UvrB-binding, and insertion domains (Figure 5(b)). UvrA has two ATPase modules: one is divided into an ATP-binding domain I and a signature domain I, the other is divided into an ATP-binding domain II and a signature domain II. UvrA contains three zinc ions. It has been reported that ttUvrA and ttUvrB can recognize bulky adducts, such as tetramethylrhodamine and tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester, and (6-4) pyrimidine dimer [113, 131]. Furthermore, it has been shown that ttUvrA can interact with the ATL protein, but the physiological significance of this interaction remains unclear [37].

The overall structure of TRCF was reported in 2006 [122]. Domains 1a, 2, and 1b comprise a UvrB homology module, which interacts with UvrA (Figure 5(c)). Domains 5 and 6 comprise a DNA translocation module. Domain 4 is an RNA polymerase interaction domain (RID). The RID and the DNA translocation modules are linked by a long helix called the relay helix. The functions of domains 3 and 7 are unclear. The mfd gene from T. thermophilus (the gene product name is ttTRCF; TTHA0889) is listed in the genome annotation but no formal report has yet been published.

The 3D structures of these proteins show that they all contain several enzymatic domains. The NER pathways involve multi-step processes; therefore, almost all the proteins can interact in order to advance the process to the next repair step. TRCF has a UvrA-binding domain whose amino acid sequence and 3D structure are similar to those of the UvrB domain 2 [122]. Therefore, it might be expected that TRCF would bind to UvrA in the same manner as UvrB. The mechanisms of interaction of TRCF with UvrA and other proteins, such as the ATL protein, are not yet well defined.

5. Mismatch Repair

The DNA mismatch repair (MMR) machinery recognizes and corrects mismatched or unpaired bases that principally result from errors by DNA polymerases during DNA replication. MMR increases the accuracy of DNA replication by at least 3 orders of magnitude [132]. Mutations in the genes involved in MMR are associated with increased predisposition to human hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancers [133]. Postreplication MMR is achieved by removal of a relatively long tract of mismatch-containing oligonucleotides, a process called long-patch MMR. Here, we refer to long-patch MMR simply as MMR.

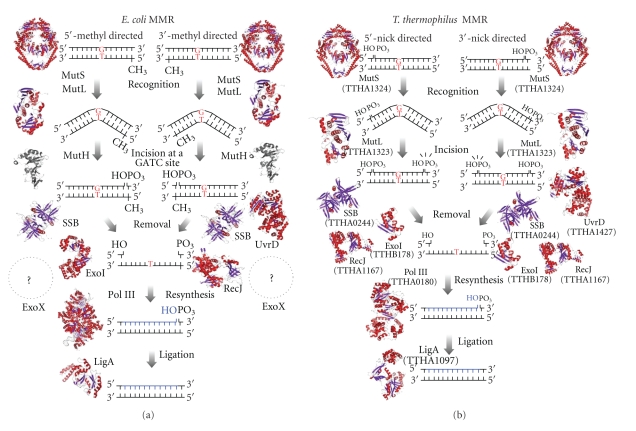

5.1. Methyl-Directed MMR in E. coli

In E. coli, the first steps in MMR are performed by the MutHLS system, which consists of three proteins, MutS, MutL, and MutH (Figure 6(a)) [134, 135]. In this system, a MutS homodimer recognizes and attaches to a mismatched base in the dsDNA [136–138]. A MutL homodimer then interacts with and stabilizes the MutS-mismatch complex and activates a MutH restriction endonuclease [139]. The MMR system needs to discriminate the newly synthesized DNA strand in order to remove the incorrect base of the mismatched pair. However the mismatch itself contains no signal for such discrimination. The E. coli MMR system utilizes the absence of methylation at a restriction site to direct repair to the newly synthesized strand [135]. Immediately after replication, the restriction sites in the newly synthesized strand remain unmethylated. At the site of a mismatch, the MutH endonuclease nicks the unmethylated strand at a hemimethylated GATC site to introduce an entry point for the excision reaction. The error-containing region is excised by a DNA helicase [140] and an ssDNA-specific exonuclease [141–143]. The excised tract of oligonucleotides is then replaced by DNA synthesis directed by DNA polymerase III and a ligase. Since the absence or presence of methylation provides the signal for strand discrimination, E. coli MMR is termed methyl-directed MMR [135]. Homologues of E. coli MutS and MutL are found in almost all organisms; however, no homologue of E. coli MutH has been identified in the majority of eukaryotes or most bacteria.

Figure 6.

A schematic representation of models for MMR pathways in E. coli and mutH-less bacteria. (a) 5′- and 3′-methyl-directed MMR in E. coli. DNA mismatches principally result from misincorporation of bases during DNA replication. The MutS (PDB ID: 1E3M)/MutL (PDB ID: 1NHJ) complex recognizes a mismatch and activates the MutH endonuclease (PDB ID: 1AZO). MutH nicks the unmethylated strand of the duplex to introduce an entry point for the excision reaction. In 3′-methyl-directed MMR, one of the 5′-3′ exonucleases (RecJ and exonuclease VII (ExoVII)) removes the error-containing DNA strand in cooperation with UvrD helicase (PDB ID: 2IS4) and single-stranded DNA-binding protein (SSB; PDB ID: 1EYG). By contrast, one of the 3′-5′ exonucleases (exonuclease I (ExoI; PDB ID: 1FXX) and exonuclease X (ExoX)) is responsible for the 3′-5′ excision reaction. DNA polymerase III (PDB ID: 2HNH) and DNA ligase (PDB ID: 2OWO) synthesize a new strand to complete the repair. (b) A predicted model for 5′- and 3′-nick-directed MMR in T. thermophilus. After recognition of a mismatch by MutS (TTHA1324), MutL (TTHA1323) incises the discontinuous strand of the mismatched duplex to direct the excision reaction to the newly synthesized strand. The error-containing DNA segment is excised by UvrD helicase (TTHA1427), SSB (TTHA0244), and an exonuclease (either RecJ (TTHA1167; PDB ID: 2ZXR) or ExoI (TTHB178)) followed by the resynthesis of a new strand by DNA polymerase III (TTHA0180) and DNA ligase (TTHA1097). The modeled structures of T. thermophilus MutS, MutL (amino acid residues 1–316), ExoI, DNA polymerase III α subunit, DNA ligase, and E. coli RecJ were modeled using SWISS-MODEL. The template structures used for model building were E. coli MutS, the N-terminal domain of MutL, ExoI, UvrD, DNA polymerase III α subunit, DNA ligase, and T. thermophilus RecJ.

5.2. Nick-Directed MMR in Eukaryotes

In eukaryotes, it has been demonstrated that strand discontinuity serves as a signal for directing MMR to a particular strand of the mismatched duplex in vitro. In living cells, newly synthesized strands contain discontinuities as 3′-ends or termini of Okazaki fragments. Since the presence or absence of a nick can be a strand discrimination signal, eukaryotic MMR is termed nick-directed MMR. It has also been reported that the shorter path from a nick to the mismatch is removed by the excision reaction, indicating that 5′- and 3′-nick-directed MMR are distinct [144–147]. Surprisingly, both 5′- and 3′-nick-directed strand removal requires the 5′-3′ exonuclease activity of exonuclease 1 (EXO1) [148, 149]. This apparently contradictory requirement for 5′-3′ exonuclease activity in 3′-nick-directed MMR was explained by the breakthrough discovery that the human MutL homologue MutLα (MLH1-PMS2 heterodimer) and the yeast homologue MutLα (MLH1-PMS1 heterodimer) harbor latent endonuclease activity, which nicks the discontinuous strand of the mismatched duplex [147, 150, 151]. In eukaryotic 5′-nick-directed and 3′-nick-directed MMR, MutLα incises the 3′- and 5′- sides of a mismatch, respectively, to yield a DNA segment spanning the mismatch. Then, the 5′-3′ exonuclease activity of EXO1 removes the segment.

5.3. MMR in mutH-Less Bacteria

The DQHA(X)2E(X)4 motif in the C-terminal domain of the PMS2 subunit of human MutLα comprises the metal-binding site, which is essential for endonuclease activity [150]. In mutH-less bacteria, the C-terminal domains of MutL homologues contain this metal-binding motif and exhibit endonuclease activity [150, 152]; moreover, in T. thermophilus, Aquifex aeolicus, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, this activity is abolished by mutations in the motif [152–154]. The endonuclease activity of T. thermophilus MutL has been shown to be essential for in vivo DNA repair activity [152]. Thus, the molecular mechanism of MMR in mutH-less bacteria appears to resemble that of eukaryotic MMR (Figure 6(b)).

MutS homologues from mutH-less bacteria show fundamentally similar properties to E. coli MutS and eukaryotic MutSα. First, T. thermophilus MutS exhibits a high affinity for mismatched heteroduplexes [138, 155], and the mismatch-MutS complex seems to be stabilized by MutL [152]. Second, similar ATP binding-dependent conformational changes have been observed in MutS homologues from T. thermophilus [156], E. coli [157, 158], and humans [159, 160]. Third, the crystal structures of Thermus aquaticus MutS [137], E. coli MutS [136, 161], and human MutSα [162] exhibit a common mismatch recognition mode in which the mismatched base is recognized by the intercalated phenylalanine residue from one of the two subunits. Finally, T. thermophilus mutS gene complements the hypermutability of the E. coli mutS-deleted null mutant [138]. These results indicate that interspecies variations in MMR machinery may principally derive from differences in the functions of the MutL homologues.

The biochemical properties of MutL endonucleases have been studied using MutL homologues from mutH-less thermophilic bacteria such as T. thermophilus and A. aeolicus. The endonuclease activity of T. thermophilus MutL is suppressed by the binding of ATP [152]. MutL homologues belong to the GHKL ATPase superfamily that also includes homologues of DNA gyrase, Hsp90, and histidine kinase [163]. GHKL superfamily proteins undergo large conformational changes upon ATP binding and/or hydrolysis. Such conformational changes are expected to affect the molecular functions of the MutL homologues [164, 165]. The endonuclease activities of MutL homologues exhibit no sequence or structure specificity [150, 152]; hence, it is thought that living cells may have mechanisms for regulating these activities. Cells may employ ATP binding-induced suppression of MutL endonuclease activity in order to ensure mismatch-specific incision. It has also been suggested that the ATP binding form of T. thermophilus MutL preferably interacts with a MutS-mismatch complex [152]. Since the ATPase activity of MutL is activated by interaction with MutS, it could be speculated that the ATP binding-dependent suppression of the endonuclease activity of MutL is canceled by the interaction with a MutS-mismatch complex. Recently, it was reported that the endonuclease activity of A. aeolicus MutL in response to ATP depends on the concentration of the protein and that when A. aeolicus MutL is present at relatively high concentrations activity is stimulated, not suppressed, by ATP [154]. This result indicates that ATP is required not only for suppression but also for active enhancement of the endonuclease activity of MutL.

5.4. Strand Discrimination in Nick-Directed MMR

As mentioned above, a pre-existing strand break serves as a signal to direct the excision reaction in eukaryotic nick-directed MMR [146, 150]. Since daughter strands always contain 3′- or 5′- termini during replication, these ends may act as strand discrimination signals in vivo. In eukaryotic nick-directed MMR, MutLα is responsible for strand discrimination by incising the discontinuous strand [150]. Interestingly, MutLα has been found to incise the discontinuous strand at a distal site from the pre-existing strand break. It remains to be elucidated how MutLα discriminates the discontinuous strand of the duplex at a site far removed from the strand discrimination signal. One possible explanation may lie in the association of MutS and MutL homologues with replication machinery. MSH6 and MSH3 subunits contain a PCNA-interacting motif [166], and this interaction between MutSα and PCNA is now well characterized [167]. Furthermore, both PCNA and replication factor C (RFC) are required for stimulation of the latent endonuclease activity of MutLα in eukaryotic MMR [150]. These results suggest that MutSα (or MutSβ) and MutLα are loaded onto the substrate DNA through an interaction with PCNA in the presence of RFC to produce binding to the newly synthesized strand in the catalytic site of the MutLα endonuclease domain [168–170]. In mutH-less bacteria, it has been also demonstrated that mismatch-provoked localization of MutS and MutL is controlled through an association with β-clamp, a bacterial counterpart of eukaryotic PCNA [171]. These interactions may also be responsible for strand discrimination in bacterial nick-directed MMR.

5.5. Downstream Events in Nick-Directed MMR

EXO1 is responsible for the excision reaction in eukaryotic MMR in vitro. To date, EXO1 is the only ssDNA-specific exonuclease that has been reported to be involved in the reaction [150, 172]. In addition, no MMR-related eukaryotic DNA helicase has yet been identified. The exonuclease activity of eukaryotic EXO1 is enhanced by a direct interaction with MutSα in a mismatch- and ATP-dependent manner [173]. MutSα is known to form a sliding clamp that diffuses along the DNA after mismatch recognition. The diffusion of MutSα from the mismatch may be required for the activation of EXO1 at the 5′-terminus of the error-containing DNA segments. In contrast to eukaryotes, the MutL of A. aeolicus stimulates DNA helicase activity in UvrD, an enzyme that shows high conservation of amino acid sequence among bacteria [174]. Furthermore, in T. thermophilus, genetic analyses have indicated that 5′-3′ exonuclease RecJ and 3′-5′ exonuclease ExoI are involved in parallel pathways of MMR [175]. It is possible that mutH-less bacteria employ the cooperative function of multiple exonucleases and helicases to remove error-containing DNA segments.

Termination of the EXO1-dependent excision reaction in eukaryotic 3′-nick-directed and MutLα-dependent 5′-nick-directed MMR is expected to be determined by pre-existing and newly introduced 3′-termini, respectively. In mutH-less bacteria, the mechanism for termination of the excision-reaction remains unknown. Since not only 5′-3′ exonuclease but also 3′-5′ exonuclease can be involved in the repair [175], termination of an excision reaction in 5′- and 3′-nick-directed MMR might be achieved by the 3′- and 5′-termini that are introduced by MutL.

Further biochemical and structural studies on exonucleases are required to achieve a deeper understanding of the excision reaction. Recently, the crystal structure of intact RecJ, a 5′-3′ exonuclease, from T. thermophilus was reported [176]. The entire structure of RecJ consists of four domains that form a ring-like structure with the catalytic site in the center of the ring. One of these four domains contains an oligonucleotides/oligosaccharide-binding fold that is known as a nucleic acid-binding fold. Knowledge of these structural features increases our understanding of the molecular basis for the high processivity and specificity of this enzyme. Furthermore, two Mn2+ ions in the catalytic site suggest that RecJ utilizes a two-metal ion mechanism [177] for the exonuclease activity. The understanding of a 3′-5′ exonuclease in MMR has been also enhanced by the ongoing biochemical studies on T. thermophilus ExoI [175]. The study revealed that ExoI has extremely high K M value compared with other exonucleases. The interactions with other MMR proteins might stimulate the DNA-binding activity of ExoI. Especially, it would be intriguing to examine the interaction between ExoI and MutS.

6. Recombination Repair

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are the most crucial lesions in DNA for inducing loss of genetic information and chromosomal instabilities. DSBs can be caused by ionizing radiation, ROS, nuclease dysfunction, or replication fork collapse [178]. Defects in the repair of DSBs lead to cancer or other severe diseases [179–181]. There are two different pathways for repair of DSBs, homologous recombination (HR) and nonhomologous end-joining [178]. HR is the accurate pathway and makes use of undamaged homologous DNA as a template for repair. Nonhomologous end-joining directly ligates two DSB ends together, and although it is efficient, it is prone to loss of genetic information at the ligation sites. In most bacteria, the HR pathway is thought to be the major route for repair of DSBs [182–184].

Recombination repair of DSBs consists of various steps: end resection, strand invasion, DNA repair synthesis, branch migration, and Holliday junction (HJ) resolution (Figure 7). Although the repair-related components and details of each step show variations among organisms, these steps are conserved in all organisms, and there are many evolutionarily conserved functional homologues involved in recombination repair [182, 184]. The first step of recombination repair, end resection, is initiated by a 5′ to 3′ degradation of DSB ends to generate 3′-ssDNA tails. Next, mediator proteins bind to the 3′-tailed ssDNA and load the recombinase to promote formation of a nucleoprotein filament. The recombinase searches for a homologous DNA sequence and catalyzes strand invasion to yield a D-loop structure. After strand invasion, DNA synthesis occurs using the homologous DNA as the template, and the intermediates are processed through a branch migration reaction to form HJs, stable four-stranded DNA structures. Finally, HJs are endonucleolytically resolved into linear duplexes, and the nicks at cleavage site are sealed by DNA ligase to complete the repair. HR significantly contributes to retention of genome integrity; however, this mechanism is also utilized for the rearrangement of genome, such as incorporation of foreign DNAs or intrachromosomal gene conversion [185, 186]. There are various anti-recombination mechanisms to suppress excessive recombination that might cause genomic instabilities [187, 188]. These sub-pathways interact with each other to regulate the HR system.

Figure 7.

A schematic pathway of recombination repair and structures of the proteins involved in T. thermophilus. Recombination repair of DSBs is initiated by an end resection step in which DSB ends are processed by the concerted action of RecJ nuclease (TTHA1167; PDB ID: 2ZXR) and SSB (TTHA0244; PDB ID: 2CWA) to form 3′-ssDNA tails. After end resection, the SSB-ssDNA complex is disassembled and RecA recombinase (TTHA1818) is loaded onto ssDNA by “mediators”, RecF (TTHA0264), RecO (TTHA0623), and RecR (TTHA1600), to promote strand invasion. DNA repair synthesis is primed by PolI (TTHA1054) and PolIII (TTHA0180) from the invaded strand of the D-loop structure. Alternatively, second-end capture is mediated by RecO and SSB and branch migration mediated by the RuvA-RuvB complex (TTHA0291-TTHA0406; PDB ID: 1IXR) and RecG (TTHA1266) to yield HJs. HJs are cleaved by RuvC resolvase (TTHA1090) and the nicks sealed by LigA (TTHA1097). Newly synthesized DNA is colored in blue. The model structures of T. thermophilus RecA, RecF, RecO, RecR, PolI, PolIII α subunit, RecG, RuvC, and LigA were generated using SWISS-MODEL. The models were based on the structures of Mycobacterium smegmatis RecA (PDB ID: 2OE2), D. radiodurans RecF (PDB ID: 2O5V), RecO (PDB ID: 1U5K), RecR (PDB ID: 1VDD), E. coli PolI (PDB ID: 1TAU), PolIII α subunit (PDB ID: 2HNH), RuvC (PDB ID: 1HJR), LigA (PDB ID: 2OWO), and Thermotoga maritima RecG (PDB ID: 1GM5).

6.1. End Resection and Loading of Recombinase

Recombination repair is initiated by an end resection step that processes DSB ends to generate 3′-ssDNA tails. In mammals, various nucleases and helicases have been implicated in this step, such as the MRN complex, CTIP, EXO1, DNA2, and RECQ paralogues [189]. By contrast, most bacteria have two major sub-pathways, the RecF pathway and the RecBCD/AddAB pathway [183, 190, 191]. The RecF pathway is highly conserved in many bacteria and is similar to the eukaryotic end resection pathway whereas the RecBCD/AddAB pathway differs from that of eukaryotes and also shows diversity in bacteria. In the RecF pathway, RecJ nuclease, RecQ helicase, and SSB act in concert in the processing of DSB ends. After DNA unwinding by RecQ helicase and 5′ to 3′ exonucleolytic degradation by RecJ nuclease, the generated 3′-ssDNA tails are coated and stabilized with SSB [192]. Interestingly, there is no RecQ homologue in T. thermophilus HB8 [193]. However, a recent in vitro reconstitution study of the E. coli RecF pathway showed that RecJ nuclease degrades dsDNA exonucleolytically in the absence of RecQ helicase [190]. Another study also showed that Haemophilus influenzae SSB directly interacts with RecJ nuclease and stimulates exonuclease activity [194]. Based on these results, it could be speculated that in T. thermophilus HB8, RecJ nuclease and SSB might synergistically perform the end resection step without involvement of a helicase. Recently, the crystal structures of T. thermophilus RecJ and SSB were solved [176]. By combining these structural data with biochemical analyses, it should soon be feasible to elucidate the molecular mechanism of the end resection step.

In the RecF pathway, after generation of 3′-ssDNA tails, recombination mediators, RecFOR or RecOR, disassemble the SSB-ssDNA complex and load RecA recombinase onto ssDNA to form nucleoprotein filaments [190, 195]. Structural and biochemical analyses of T. thermophilus RecF, RecO, and RecR proteins showed that RecR forms a tetrameric ring-like structure and acts as a DNA clamp and also binds to RecF and RecO; on the other hand, RecO can also bind to RecR, SSB, and ssDNA [196–198]. These studies found that SSB is displaced from ssDNA by RecO and that RecA loading is mediated by RecR [198]. Based on these results, there appear to be two distinct ways for SSB displacement and RecA loading [190]. The RecFOR complex binds at the ssDNA-dsDNA junction on the resected DNA and loads RecA onto ssDNA in a 5′ to 3′ direction. The RecOR complex binds to SSB-ssDNA complex and promotes the exchange of SSB by RecA. These processes are very similar to the eukaryotic recombination repair pathway mediated by RAD52, RAD54, BRCA2, and RAD51 paralogues [199–202]. Recombinase loading by “mediators” is thought to be a common system of recombination repair in all three kingdoms of life.

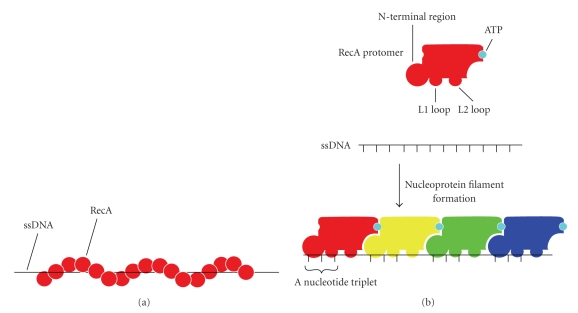

6.2. Strand Invasion by Recombinase

The DNA strand exchange between homologous segments of chromosomes is catalyzed by the RecA-family recombinases, which include RecA in bacteria, RAD51 in eukaryotes, and RadA in archaea [203]. The processes catalyzed by these recombinases have been studied in detail [204–206]. In bacteria, RecA binds to ssDNA, forming helical nucleoprotein filament (Figure 8(a)). Contact between the RecA-coated ssDNA and dsDNA allows ssDNA to search sequence homology. Strand exchange is initiated by local denaturation of dsDNA in a region of homology. The invading strand forms a paranemic joint, which is an unstable intermediate. When the free end of the strand invades, the paranemic joint is converted into a plectonemic joint, in which the two strands are intertwined. Then heteroduplex formation is extended by branch migration.

Figure 8.

A schematic illustration of RecA-ssDNA interaction in the nucleoprotein filament. (a) A schematic representation of a RecA-ssDNA nucleoprotein filament. The filament comprises a helical structure. RecA molecules are shown as red spheres and the ssDNA as a black line. (b) A schematic model of RecA-ssDNA interaction. The RecA protomer has the L1 and L2 loops and the N-terminal region to make contact with the ssDNA. The bound ssDNA comprises a nucleotide triplet with a nearly normal B-form distance between bases followed by a long internucleotide stretch before the next triplet. The ATP binds to RecA-RecA interfaces. The schematic model was prepared from the crystal structure of RecA-ssDNA complex (PDB ID: 3CMW).

The crystal structure of RecA filament determined in 1992 [207] revealed six subunits in each helical turn, but this structure contained no DNA. In 2008, Chen et al. determined the structures of both RecA complexed with ssDNA and with dsDNA [208], which are the substrate and product forms of DNA strand exchange, respectively. The RecA-ssDNA filament is different from the RecA filament primarily in the orientation of the subunit relative to the filament axis. The bound ssDNA makes contact with the L1 and L2 loops, which had been suggested to be DNA binding sites and the N-terminal region (Figure 8(b)). It had been previously assumed that in the nucleoprotein filament ssDNA is uniformly stretched by about 1.5-fold [209]. However, unexpectedly, the DNA comprises a nucleotide triplet (three-nucleotide segment) with a nearly normal B-form distance between bases followed by a long untwisted internucleotide stretch before the next triplet. In addition, ATP binds to RecA-RecA interfaces, which can couple RecA-ATP interaction to RecA-DNA interaction.

6.3. Postsynaptic Phase

After strand invasion, HJs are formed through DNA repair synthesis, second-end capture, and branch migration during the postsynaptic phase. In most organisms, a range of DNA polymerases deal with the various DNA processes, and several of these DNA polymerases are involved in recombination-associated DNA repair synthesis [210]. It has been shown that the translesion synthesis (TLS) polymerase, Polη, and replicative polymerase, Polδ, are involved in mammalian recombination-associated DNA synthesis [211–214]. In addition, a recent genetic study suggested the possible involvement of human Polν, prokaryotic PolI-like enzyme, in HR [215]. However, it is still unclear whether other DNA polymerases can synthesize the DNA strand during recombination. Interestingly, bacterial TLS polymerases, PolII, PolIV, and PolV, are also able to synthesize the DNA strand in recombination processes as well as PolI and PolIII in E. coli; however, the details of the relationship between TLS and HR remain to be elucidated [216]. The Deinococcus-Thermus group of bacteria has only two processive DNA polymerases, PolI and PolIII, and, therefore, it should be relatively straightforward to analyze the involvement of DNA polymerases in recombination-associated DNA synthesis [217, 218]. A recent study on genome repair after ionizing radiation in Deinococcus radiodurans showed that PolI and PolIII had distinct roles in the extensive synthesis-dependent strand annealing repair pathway [219]; therefore, it might be expected that in T. thermophilus, PolI and PolIII will also act in concert in recombination-associated DNA synthesis.

Second-end capture and branch migration also occur at the same time as DNA repair synthesis in the postsynaptic phase. In eukaryotes, second-end capture appears to be mediated by RAD52 and RPA, whereas their functional homologues in bacteria are RecO and SSB, respectively [220–222]. Interestingly, it has been shown that E. coli RecO cannot form joint molecules with the S. cerevisiae RPA-ssDNA complex nor can S. cerevisiae RAD52 promote second-end capture with either the human RPA-ssDNA complex or the E. coli SSB-ssDNA complex [222]. These results indicate that the second-end capture event can be performed in a species-specific manner. Various DNA translocases are involved in branch migration. There is evidence that RAD54 and RECQ paralogues process the joint molecules to generate HJs in eukaryotes. By contrast, RuvAB, RecG and RadA/Sms promote branch migration in bacteria [201, 223–225]. To date, there is no satisfactory explanation as to why a single organism might redundantly possess multiple branch migration activities. In bacteria, RuvAB are believed to be the main branch migration proteins based on their genetic properties [223, 226]. Currently, the crystal structure of the RuvAB-HJ complex is not available. However, various crystal structures involving T. thermophilus RuvA and RuvB proteins have been solved and their biochemical properties determined [227–232]. In addition, an atomic model of the RuvAB-HJ complex has been proposed based on data from electron microscopic analyses [229, 233]. These structural and functional analyses of RuvAB provide insights into its molecular properties with regard to branch migration. Two RuvA tetramers sandwich an HJ forming a planar conformation while two RuvB hexameric rings are bound to the arms of the junction symmetrically via RuvA and promote branch migration using energy from ATP hydrolysis [224]. Furthermore, by combining structural and biochemical data on RuvC resolvase, it is possible to suggest a model for HJ resolution that involves the formation of a RuvABC resolvasome [224, 234–237].

Recombination repair is completed by HJ resolution and sealing of its cleavage sites. In mammals, members of a structure-specific endonuclease family, including GEN1, SLX1, MUS81-EME1, and ERCC4-ERCC1, are involved in the resolution of HJs and recombination intermediates [238]. Recent work showed that GEN1 can act as an HJ resolvase. Other studies have suggested that the SLX4 protein can form a complex with SLX1, MUS81-EME1, or ERCC4-ERCC1 and control their activities [239–243]. It has been shown that the SLX1-SLX4 complex can resolve HJs symmetrically. In bacteria, RuvC and RusA have HJ resolvase activity. RuvC forms a dimeric structure and cleaves HJs symmetrically in a sequence-specific manner [234, 244]. Biochemical analyses of RuvC in the presence of RuvAB suggest that RuvC forms a complex with RuvAB and that the HJ resolution event is coupled with the branch migration reaction [235, 236]. In E. coli, there is another resolvase, RusA, which has cleaved HJs symmetrically at specific sites [245, 246]. It has also been suggested that topoisomerase III can resolve HJs in E. coli as an alternative to the RuvABC pathway [247]. T. thermophilus does not have either RusA or topoisomerase III [217]. Thus, this organism will be a suitable model for analyzing this step of HJ resolution because of its simple and minimal systems.

6.4. Anti-Recombination

Since excessive recombination events lead to the alteration of the genetic information, various anti-recombination mechanisms are employed by organisms to regulate the frequency of recombination [188]. For example, the MMR system is present in a wide range of organisms and serves particularly to prevent homeologous recombination [187]. In bacteria, RecX acts as an anti-recombinase that inhibits RecA recombinase in both direct and indirect manners [248]. Direct interaction with RecX inhibits the recombinase activity of RecA and destabilizes the nucleoprotein filament [249, 250]. RecX also suppresses recA induction at the transcription level [248]. The UvrD helicase is suspected to be an anti-recombinase because of its activity to disassemble the RecA nucleoprotein filament in vitro [251, 252].

Recently, a novel anti-recombination mechanism was identified in Helicobacter pylori and T. thermophilus. It was found that disruption of mutS2, a bacterial paralogue of the MMR gene mutS, significantly increased the frequency of recombination events, indicating that mutS2 had an anti-recombination function [253, 254]. It has also been shown that MutS2 is not involved in MMR, that is, MutS2 prevents recombination in an MMR-independent manner. Detailed biochemical investigation showed that T. thermophilus MutS2 possesses an endonuclease activity that preferably incises the D-loop structure, the primary intermediate in HR [253, 255–257]. MutS2 might suppress HR through the resolution of early intermediates.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 20570131 (to R. Masui), 19770083 (to N. Nakagawa) and 20870042 (to K. Fukui) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan. R. Morita and S. Nakane are the recipients of a Research Fellowship of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists (no. 21-1019 and 22-37, resp.).

References

- 1.Schärer OD. Chemistry and biology of DNA repair. Angewandte Chemie. 2003;42(26):2946–2974. doi: 10.1002/anie.200200523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altieri F, Grillo C, Maceroni M, Chichiarelli S. DNA damage and repair: from molecular mechanisms to health implications. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2008;10(5):891–937. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. Washington, DC, USA: ASM Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oshima T, Imahori K. Description of Thermus thermophilus (Yoshida and Oshima) comb. nov., a nonsporulating thermophilic bacterium from a Japanese thermal spa. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 1974;24(1):102–112. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iino H, Naitow H, Nakamura Y, et al. Crystallization screening test for the whole-cell project on Thermus thermophilus HB8. Acta Crystallographica Section F. 2008;64(6):487–491. doi: 10.1107/S1744309108013572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]