Abstract

Circadian rhythms occur in all levels of organization from expression of genes to complex physiological processes. Although much is known about the mechanism of the central clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the regulation of clocks present in peripheral tissues as well as the genes regulated by those clocks is still unclear. In this study, the circadian regulation of gene expression was examined in rat adipose tissue. A rich time series involving 54 animals euthanized at 18 time points within the 24-h cycle (12:12 h light-dark) was performed. mRNA expression was examined with Affymetrix gene array chips and quantitative real-time PCR, along with selected physiological measurements. Transcription factors involved in the regulation of central rhythms were examined, and 13 showed circadian oscillations. Mining of microarray data identified 190 probe sets that showed robust circadian oscillations. Circadian regulated probe sets were further parsed into seven distinct temporal clusters, with >70% of the genes showing maximum expression during the active/dark period. These genes were grouped into eight functional categories, which were examined within the context of their temporal expression. Circadian oscillations were also observed in plasma leptin, corticosterone, insulin, glucose, triglycerides, free fatty acids, and LDL cholesterol. Circadian oscillation in these physiological measurements along with the functional categorization of these genes suggests an important role for circadian rhythms in controlling various functions in white adipose tissue including adipogenesis, energy metabolism, and immune regulation.

Keywords: circadian rhythms, metabolism, adipokine, lipids, microarray

circadian rhythms are oscillations in behavioral, physiological, cellular, and biochemical processes with a period of ∼24 h that are controlled by an endogenous clock. In mammalian systems, the central clock system is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which receives direct input from photoreceptive retinal ganglion cells containing melanopsin through the retinohypothalamic tract, thereby entraining and synchronizing circadian oscillations to the light-dark cycle (26). Circadian oscillators are also found in other parts of the brain and in peripheral tissues and are at least in part coordinated and synchronized by the central clock. Although much is known about the mechanism of the central clock in the SCN, the regulation of clocks and the response to those clocks present in peripheral tissues is still unclear.

Molecular analyses show that the central clock mechanism involves an autoregulatory negative feedback loop of gene expression consisting of BMAL1, CLOCK, and NPAS2 transcription factors that form the positive arm and the PERIOD and CRYPTOCHROME transcription factors that form the negative arm of the feedback loop (17, 38, 50). BMAL1 heterodimerizes with either CLOCK or NPAS2 and binds to E-box elements, thereby transactivating the expression of Per (Per1, Per2, and Per3) and Cry (Cry1 and Cry2) genes. After reaching a critical concentration, the proteins encoded by these genes form heterotypic complexes and repress the transcriptional activity of the BMAL1:CLOCK or BMAL1:NPAS2 complexes. In addition to these core transcription factors, many other transcription factors that are directly regulated by the core factors including REV-ERBs, RORs, PAR-bZip, and BHLHBs are also involved in the regulation of the circadian expression of the transcriptome (21, 29, 45).

Circadian rhythms play an important role in maintaining and coordinating normal biological processes necessary for efficient functioning of an organism. Disruption of circadian rhythms can lead to metabolic disorders such as cancer, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases (47, 54). In some disorders, symptoms also show circadian oscillations. For example, in rheumatoid arthritis symptoms such as joint pain, stiffness, and functional disability peak during the early active period (morning in humans) (15). Similarly in asthma the symptoms worsen during the late inactive period (late night in humans) (8), and in humans there is an increased incidence of myocardial infarction in early morning (63).

In recent years white adipose tissue has been recognized as playing a pivotal role in many pathological states including metabolic syndrome, obesity, and diabetes (60). Adipose tissue is made up of heterogeneous cell types consisting of mature adipocytes, preadipocytes, mesenchymal stem cells, immune cells (predominantly macrophages), vasculature, and nerves. Of these cell types only mature adipocytes can store triglycerides and participate in the cycle of lipogenesis and lipolysis. The proliferation and differentiation of stem cells into preadipocytes and subsequently into mature adipocytes is controlled by a number of transcription factors, and a dynamic equilibrium exists in the numbers of preadipocytes and mature adipocytes in the tissue. In addition to its primary function as the reservoir for excess energy, adipose tissue also serves as an endocrine organ, producing adipokines such as leptin, adiponectin, visfatin, resistin, and omentin as well as inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, etc.), chemokines (CXCL8, MCP-1, etc.) and other chemical mediators such as prostaglandins. These protein and chemical mediators regulate many important biological processes such as energy metabolism and immune/inflammatory responses.

In previously published reports (3, 4), we used Affymetrix 230A gene arrays to profile global mRNA expression in liver and skeletal muscle tissue from male Wistar rats killed across the 24-h light-dark cycle. The genes showing circadian oscillation in expression in liver were analyzed for function with particular focus on potential therapeutic targets, and the circadian expression in skeletal muscle was analyzed for function with particular focus on energy metabolism. Furthermore, the effects of exogenous glucocorticoid administered at a specific time during the 24-h cycle on the expression of these genes were analyzed.

The objectives of this study were to identify and analyze circadian oscillations in gene expression in white adipose tissue and to identify the role of circadian regulation in coordinating the functioning of this dynamic tissue. We used Affymetrix 230_2 gene array chips to profile global mRNA expression in abdominal adipose tissue from the same animals used for our previous studies in liver and muscle. Furthermore, circadian oscillations in selected physiological parameters relevant to white adipose tissue function were also quantified in these animals. These physiological measurements along with functional categorization of mRNA expression provide insight into the role of circadian oscillations in the proper functioning of white adipose tissue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

A more extensive description of this experiment can be found in our previously published reports (3, 4). In brief, 54 normal male Wistar rats in two batches of 27 each from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) were allowed to acclimatize in a constant-temperature environment (22°C) equipped with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with free access to standard rat chow and drinking water. Our research protocol adheres to the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” (NIH Pub. No. 85-23, revised 1985) and was approved by the State University of New York at Buffalo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine (80 and 10 mg/kg) and killed by exsanguination on three successive days at 0.25, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 11, and 11.75 h after lights on for time points in the light period and at 12.25, 13, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 23, and 23.75 h after lights on for time points in the dark period . Animals killed at the same time on the three successive days were treated as triplicate measurements. Blood was drawn from the abdominal aortic arteries into syringes with EDTA (4 mM final concentration) as anticoagulant. Plasma was prepared from blood by centrifugation (2,000 g, 4°C, 15 min), divided into aliquots, and stored at −80°C. A discrete abdominal fat pad was harvested bilaterally, rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

Hormones.

Commercial ELISA kits were used to quantify plasma leptin (Rat Leptin TiterZyme EIA, Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI) and plasma adiponectin (Rat Adiponectin EIA, ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH) concentrations. Insulin was measured in plasma samples with a commercial RIA kit (RI-13K Rat Insulin RIA Kit, Millipore, St. Charles, MO). These commercial kits were used per manufacturers' protocols with standards run in duplicate and samples run in triplicate.

Plasma glucose.

Plasma glucose was measured by the glucose oxidase method (Sigma GAGO-20). The manufacturer's instructions were modified such that the assay was carried out in a 1-ml assay volume, and a standard curve consisting of 7 concentrations over a 16-fold range was prepared from the glucose standard and run with each experimental set. Experimental samples were run in triplicate.

Lipid assays.

Commercially available colorimetric assay reagents were used for quantitative determination of total cholesterol (Cholesterol E: in vitro enzymatic colorimetric assay, Wako Chemicals, Richmond VA), total triglycerides (L-type TG H, Wako Chemicals), HDL (HDL Cholesterol E: phosphotugstate-magnesium salt precipitation method, Wako Chemicals), and LDL cholesterol (L-Type LDL-C, Wako Chemicals). All assays were performed with modifications to the manufacturer's protocol in order to scale down to a microtiter plate format. Plasma free fatty acids were measured with a nonesterified fatty acids detection kit (Zen-Bio, Research Triangle Park, NC) with standard curves constructed from a commercial standard solution (Wako NEFA, Wako Chemicals).

Microarrays.

Adipose tissue samples were ground into a fine powder with a mortar and pestle cooled by liquid nitrogen, and 300 mg of tissue was added to 3 ml of QIAzol lysis reagent (QIAGEN Sciences, Germantown, MD). Total RNAs were extracted according to manufacturer's instructions and were further purified with RNeasy mini columns (RNeasy Mini Kit, QIAGEN Sciences). Final RNA preparations were resuspended in RNase-free water and stored at −80°C. RNAs were quantified spectrophotometrically, and purity and integrity were assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis. All samples used for arrays exhibited 260- to 280-nm absorbance ratios of ∼2.0, and all showed intact ribosomal 28S and 18S RNA bands in an approximate ratio of 2:1 as visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Isolated RNA from each sample was used to prepare target according to manufacturer's protocols. The biotinylated cRNAs were hybridized to 52 individual Affymetrix GeneChips Rat Genome 230_2 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). The 230_2 chips contain >31,000 different probe sets. The high reproducibility of in situ synthesis of oligonucleotide chips allows accurate comparison of signals generated by samples hybridized to separate arrays. This data set has been submitted to GEO (GSE20635).

Data set construction and mining.

Affymetrix Microarray Suite 5.0 (Affymetrix) was used for initial data acquisition and analysis. The signal intensities were normalized for each chip with a distribution of all genes around the 50th percentile. Animals that were killed at the same time on different days were considered as replicate measurements (n = 3) for that time, and 24-h time series plots were constructed from these data. A nonlinear least-squares fitting of individual replicate data points was conducted with MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA), which utilized a regular sinusoidal function [A × sin (B × t + C) + mean]. In this sinusoidal model A, B, and C reflect the amplitude, period, and phase of the oscillation. Genes that could be curve fitted with R2 correlation values >0.75 to mean data were kept for further analysis. In addition, for better visualization and analysis of the data for the light-to-dark and dark-to-light transition, two 24-h cycles were concatenated to form a 48-h time series. Concatenation provided a visual check that the end of one cycle seamlessly fit to the beginning of the next cycle, further confirming circadian expression. This particular approach is only viable because of our rich data set. The data set was then loaded into a data mining program, GeneSpring 7.3.1 (Silicon Genetics, Redwood City, CA), and we normalized the value of each probe set on each chip to the median of that probe set on all chips. To identify genes that show similar expression patterns within the light-dark cycle, we used a quality threshold (QT) clustering algorithm in the GeneSpring software, employing Pearson's correlation as the similarity measurement.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

The quantity of abdominal fat glucocorticoid receptor (GR), leptin, and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) mRNA along with gene-specific in vitro-transcribed cRNA standards was determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) using TaqMan-based probes. Primer and probe sequences were designed with PrimerExpress software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and custom synthesized by Biosearch Technologies (Novato, CA). The qRT-PCR was performed with the Brilliant QRT-PCR Core Reagent Kit, 1-Step (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) in a Stratagene MX3005P thermocycler according to the manufacturer's instructions. A standard curve was generated with in vitro-transcribed sense cRNA standards. Primer and probe sequences are as follows: GR: forward primer 5′ AACATGTTAGGTGGGCGTCAA 3′, reverse primer 5′ GGTGTAAGTTTCTCAAGCCTAGTATCG 3′, and FAM-labeled probe 5′ TGATTGCAGCAGTGAAATGGGCAAAG 3′; leptin: forward primer 5′ GGCTTTGGTCCTATCTG 3′, reverse primer GTGTCATCCTGGACTTTG 3′, and FAM-labeled probe TCCTATGTTCAAGCTGTGCCTATCCA 3′; PEPCK: forward primer 5′ CCGGGCACCTCAGTGAAG 3′, reverse primer 5′ CACGTTGGTGAAGATGGTGTTT 3′, and FAM-labeled probe 5′ ATCCGAACGCCATTAAGACCATC 3′. Samples were run in triplicate and standards in duplicate. Additional reverse transcriptase (RT) minus controls were run for each RNA sample analyzed to check for genomic DNA contamination; all controls exhibited lack of amplification in RT minus controls. Intra- and interassay coefficient of variation values were <15%.

RESULTS

Core clock and clock-controlled transcription factor expression in white adipose tissue.

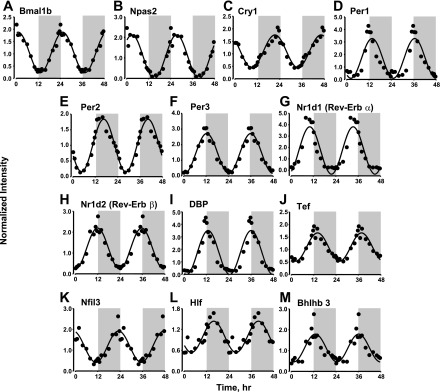

After normalization and mining, the array data were examined for the expression of the core clock genes and clock-controlled transcription factors that are known to regulate circadian rhythms. The Rat 230_2 chips contained probe sets for 18 of these core clock and clock-controlled transcription factors (21, 58). However, only 13 of the 18 showed circadian rhythmicity in their expression, as shown in Fig. 1. Consistent with literature data on core clock gene expression in the SCN (master clock) and other peripheral tissues, PAS-bHLH transcription factor Bmal1 and Npas2 mRNA expression peaked during the early light period [zeitgeber time (ZT) 1]. Per transcription factors Per1, Per2, and Per3 peaked during the early dark period (ZT 13 for Per1 and Per3 and ZT 16 for Per2), and Cry transcription factor Cry1 peaked during the late dark period (ZT 21). Nuclear orphan receptors Nr1d1 and Nr1d2 showed similar expression patterns, with peak expression occurring at the transition from the light to the dark period (ZT 12). The clock-controlled transcription factors Dbp, Hlf, and Tef all showed very similar expression patterns, with peaks occurring at the early dark period (ZT 13), while Nfil3, which represses the expression of genes containing D-box binding elements, showed an opposite expression pattern, with the peak occurring at the transition from the dark to the light cycle (ZT 0). Furthermore, repressor protein Bhlhb3 also showed circadian rhythmicity in its expression, with maximal expression occurring at the transition between the light and the dark period (ZT 12). Although the Rat 230_2 chips contained probe sets for Clock, Cry2, Bhlhb2, RORα, and RORβ genes, no circadian rhythmicity was observed in the mRNA expression of these mRNAs. Visual examination of the signal intensities for these probe sets showed that, except for RORα, the remainder of these probe sets displayed very low signal intensities, which could prevent identification of rhythmicity in the expression of these genes. These chips did not have a probe set for RORγ.

Fig. 1.

Expression patterns of core clock and clock-controlled transcription factors in abdominal adipose tissue as a function of circadian time: Bmal1 (A), Npas2 (B), Cry1 (C), Per1–3 (D–F), Nr1d1–2 (G, H), Dbp (I), Tef (J), Nfil3 (K), Hlf (L), Bhlhb3 (M). Shaded areas indicate dark periods, and unshaded areas indicate light periods. Circles represent the original data, and solid lines represent the curve fitted to a sine function.

Data mining and quality threshold clustering.

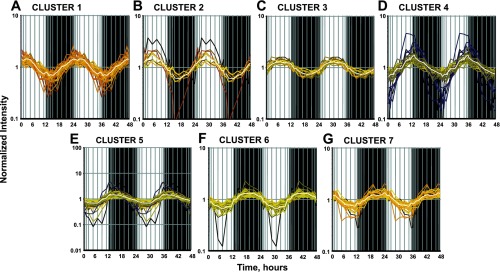

The general sinusoidal model applied to the data set identified 190 probe sets that showed R2 correlation values to the fitted curve >0.75. Supplemental Table S1 gives the values of the parameters of the sine function that were estimated for all the 190 probe sets.1 The estimated value for parameter B, which reflects the periodicity of the oscillations, was ∼0.26 (2π/24) for all mined probe sets, which further confirms that the oscillations are indeed circadian (with 24-h periodicity). Because of the richness of the time series data, we were further able to apply QT clustering to group these probe sets based on the similarity in their expression patterns within the light-dark cycle. This procedure yielded seven discrete clusters of probe sets, and each probe set displayed a minimum correlation coefficient of 0.75 with the centroid of its assigned cluster as shown in Fig. 2. Thirty-two probe sets (17%) peaked during the transition from dark to light or during the early light period (cluster 1), 28 (15%) peaked during the light period (clusters 2 and 3), 24 (13%) peaked during the transition from light to dark period (cluster 4), and 106 probe sets (56%) peaked during the early, middle, and late dark/active period (clusters 5, 6, and 7).

Fig. 2.

Quality threshold (QT) clustering of genes showing circadian oscillations in expression in abdominal adipose tissue: cluster 1 (A), cluster 2 (B), cluster 3 (C), cluster 4 (D), cluster 5 (E), cluster 6 (F), cluster 7 (G). Each probe set has a Pearson's correlation value of >0.75, with the centroid of the cluster (average curve) shown in white. Shaded areas indicate dark periods, and unshaded areas indicate light periods.

Functional grouping.

Accession numbers corresponding to each of the 190 probe sets were analyzed with a variety of online databases and tools including GeneCards, NCBI BLAST, and other NCBI tools to confirm the identity of the genes and annotation provided by Affymetrix and to obtain alternative names and symbols for the genes. With this information, extensive literature research was performed to identify the tissue-specific functions for these probe sets. We avoided the use of currently available pathway analysis tools because the databases for these tools are not complete (i.e., they do not represent all the functional genes identified) and do not take into account tissue-specific (or even organism specific) physiological functions. Of the 190 probe sets that showed circadian oscillation, we were able to identify the function of 147, corresponding to 127 genes (because some genes are represented by multiple probe sets) that we categorized into eight functional groups. These functional groups include Inflammation/Immune Response; Transcription, Posttranscription, and Translation Regulation; Lipid Metabolism; Transport; Cytoskeleton/Extracellular; Cell Cycle/Apoptosis; Signal Transduction; and Protein Processing. The identified probe sets that did not fall into any of these categories were classified as Miscellaneous. The remaining 43 probe sets that did not have any specific function identified correspond either to expressed sequence tags (ESTs) or to genes with unknown function. Supplemental Table S2 gives the relevant information for all probe sets categorized on the basis of their function. However, it should be noted that some of the probe sets/genes can fit into more than one functional category. For example, Klf15 is placed in the transcription regulation category because it regulates the expression of many genes by functioning as a transcription factor, but it can also be placed in Cell Cycle/Apoptosis because of its role in regulating cellular proliferation and differentiation. In addition, Supplemental Table S3 provides the normalized data for each of these 190 probe sets.

Transcription, Posttranscription, and Translation Regulation represents the most populated functional group, with 49 probe sets representing 41 genes. This functional group includes genes encoding transcription factors, activators, and repressors. The core clock and clock-controlled transcription factors are included in this functional group. Several of the transcription factors in this category play an important role in regulating adipogenesis and adipocyte differentiation. For example, Kruppel-like factors 9 and 15 are involved in adipocyte differentiation (25, 39). Both genes are part of cluster 5 and show maximal mRNA expression in the early dark/active period (ZT 14). The expression patterns of these genes along with several other examples are presented in Supplemental Fig. S1. Another example is Dsipi, also called Gilz (glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper), which acts as a negative regulator of adipogenesis by repressing the expression of PPARγ (23). This gene is grouped in cluster 6, with its maximum mRNA expression during the middle dark period (ZT 18). This group also contains genes that code for proteins having histone acetyltransferase activity including Nuclear receptor coactivator 1 (Ncoa1), which acts as coactivator for many different nuclear receptors, thereby regulating adipocyte energy balance and differentiation, and Histone acetyltransferase 1 (Hat1), the sole member of type B histone acetyltransferase (19, 43, 53). Both of these genes show maximal expression during the early dark/active period (cluster 5, ZT 15). This group also contains genes coding for proteins that are found to be involved in mRNA processing (like Cugbp1, Adarb1, and Hnrpc) and RNA chaperoning (like Cirbp and Rbm3), thereby regulating RNA stability and translation efficiency.

Signal Transduction represents the next most populated functional group, with 25 probe sets representing 24 different genes. This functional group consists of genes coding for receptors, protein factors, kinases, and phosphatases that regulate signaling pathways. Some of these genes, including Insulin receptor substrate 3 (Irs3), AKT1 kinase, Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (Mapk 1), Neuropeptide Y receptor 1 (Npy1r), Growth differentiation factor 11 (Gdf11), C1q-tumor necrosis factor related protein 1 (Ctrp1), and Parathyroid hormone related hormone (Pthlh), play important roles in regulating energy homeostasis in adipose tissue by different mechanisms (16, 32, 34, 48, 55, 57). Except for Irs3, which peaks during the early light/inactive period (cluster 1), and Ctrp1, which peaks during the transition from light to dark period (cluster 4), the rest of these genes peaked during the early or middle dark/active period (clusters 5 and 6). In addition, Pthlh influences the production of insulin by beta islet cells, and Irs3, Mapk1, Akt1, and Npy1r modulate various aspects of insulin signaling pathways in a tissue-specific manner, thereby regulating energy homeostasis. Furthermore, Pthlh, Mapk1, and Akt1 also play an important role in regulating adipogenesis and adipocyte differentiation (12, 44, 46).

Inflammation/Immune Response consists of nine probe sets representing seven genes that regulate and mediate immune responses both under normal and inflammatory conditions. For example, Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (Ptgs2), also called Cyclooxygenase 2 (Cox-2), plays an important role in the production of inflammatory mediators like prostaglandins (27). The probe set for this gene showed a circadian rhythm, with peak expression at the early dark/active period and nadir at the early light/inactive period (cluster 5, ZT 15). What makes this result interesting is the fact that the expression of another gene from this group, 15-Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (Hpgd), which plays an important role in metabolizing and deactivating prostaglandins, peaked at the early light period (ZT 1) with its nadir at the early dark period, which is just the opposite of Cox-2 (14). Furthermore, two probe sets corresponding to the Fcγ receptor 2a (Fcgr2a) gene are also classified under this functional group, with peak expression occurring in the early light period (cluster 1). Fcgr2a is a low-affinity receptor for IgG molecules and is critical in regulating antibody-mediated cellular toxicity, inflammatory mediator release, phagocytosis of opsonized microbes, and antigen processing and presentation (40, 42).

Cell Cycle/Apoptosis consists of 14 probe sets representing 12 different genes with roles in regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. For example, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (CDKN1A, also called p21) is a negative regulator of cell cycle progression by inhibiting the activity of cyclin-Cdk2 and cyclin-CDK4 complexes in the G1-to-S phase transition (6). CDKN1A positively regulates adipocyte differentiation, and knockdown of this gene is found to suppress the differentiation process (28). Another example is Wee1 kinase protein, which is a critical regulator of the G2-to-M transition checkpoint by inhibiting the activity of cyclin B1-CDK1 complex (6). The expressions of Cdkn1a and Wee1 kinase show opposite circadian phases, with peak expression of Cdkn1a occurring at the transition from dark to light period (cluster 1, ZT 0) and peak expression of Wee1 occurring at the early dark period (cluster 5, ZT 16). Almost all genes present in this grouping are found to be differentially regulated in various cancers (20, 33, 35, 41).

Protein Processing contains 13 probe sets representing 10 different genes. This group consists of genes that code for proteins that are involved in protein folding, trafficking, posttranslational modifications, and degradation. For example, heat shock proteins (HSP72, HSP40, and HSP105) and FK506 binding proteins 4 and 5 act as molecular chaperones, assisting in the proper folding of other proteins, and are also involved in trafficking of certain proteins (18). It is interesting to note that all of these chaperoning proteins show peak expression during the dark/active period (clusters 5 and 7), which might be due to the fact that the body temperature in nocturnal animals peaks at this period (11).

Although Lipid Metabolism contains only six probe sets corresponding to six genes, the proteins encoded by these genes are very important in the functioning of adipose tissue. 7-Dehydrocholesterol reductase (Dhcr7), which shows maximum expression during the transition from dark to light period (cluster 1), codes for an important enzyme that is involved in cholesterol biosynthesis (56). Deficiency of this enzyme results in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, a metabolic and developmental disorder caused by reduced cholesterol and increased 7-dehydrocholesterol levels. Another gene from the same cluster, Fatty acid desaturase 1 (Fads1), is a Δ5 desaturase that catalyzes the biosynthesis of highly unsaturated fatty acids that play an important role in a variety of biological processes ranging from metabolic regulation to immune function (24). Another gene that shows maximum expression during the light/inactive period (cluster 3) is Monoglyceride lipase, which is involved in hydrolyzing triglycerides stored in adipose tissue to free fatty acids that can serve as an energy substrate during nonfeeding periods (65).

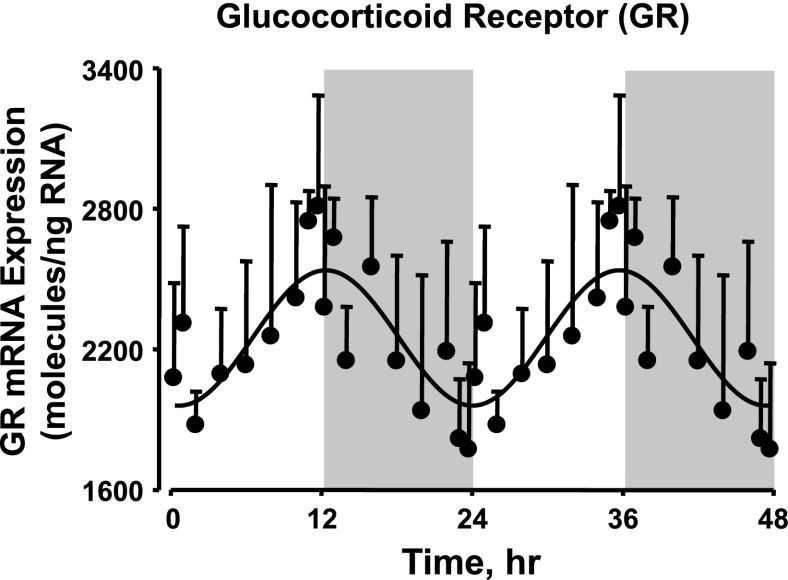

Circadian rhythms in glucocorticoid receptor mRNA expression.

GR is a cytosolic receptor that can be activated by both endogenous and exogenous glucocorticoids and is involved in the regulation of transcription of a wide variety of genes. Figure 3 shows the mRNA expression of GR in white adipose tissue quantified by qRT-PCR as a function of circadian time. The circadian profile of GR mRNA expression peaks at the transition from the light/inactive period to the dark/active period (ZT 12). Plasma corticosterone measurements from these animals have been previously published and are provided in Supplemental Fig. S2 (4).

Fig. 3.

Glucocorticoid receptor mRNA expression in abdominal adipose tissue as a function of circadian time. Shaded areas indicate dark periods, and unshaded areas indicate light periods. Circles represent mean data, with error bars representing 1 SD of the mean, and solid lines represent the curve fitted to a sine function.

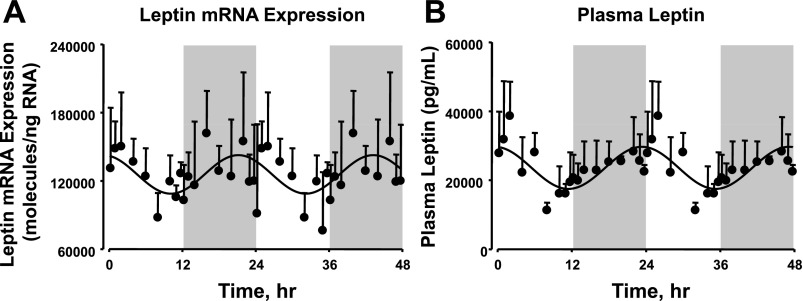

Circadian rhythms in leptin mRNA expression in white adipose tissue and plasma leptin.

Since adipose tissue is an important endocrine organ producing adipokines, we studied the circadian rhythmicity in the expression and circulating levels of leptin and adiponectin. Figure 4 shows the mRNA expression of leptin in white adipose tissue quantified by qRT-PCR and the leptin concentrations in plasma measured by ELISA as a function of circadian time. The mRNA expression of leptin peaks during the late dark/active period (ZT 21) and reaches its nadir during the late light/inactive period (ZT 9). The circadian pattern of leptin mRNA expression was directly reflected in the circadian pattern of plasma leptin concentrations, with the peak occurring at ZT 22 and the nadir at ZT 10. We also measured plasma adiponectin and adiponectin mRNA expression in white adipose tissue, but no circadian rhythmicity was observed.

Fig. 4.

Leptin mRNA expression in abdominal adipose tissue (A) and plasma leptin concentration (B) as a function of circadian time. Shaded areas indicate dark periods, and unshaded areas indicate light periods. Circles represent mean data, with error bars representing 1 SD of the mean, and solid lines represent the curve fitted to a sine function.

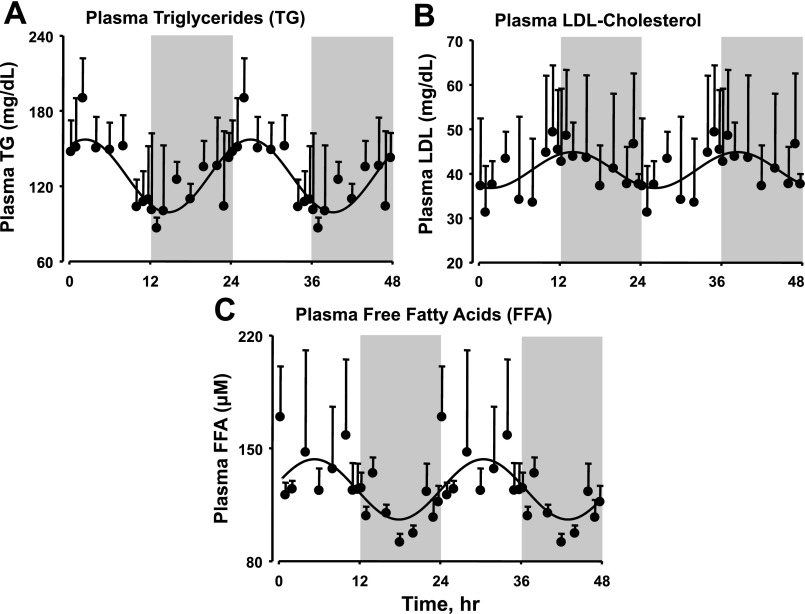

Circadian rhythms in plasma lipid profiles.

The most important metabolic function of white adipose tissue is to store excess energy substrate in the form of lipids in well-fed states and to release these stored lipids in some form that can be used as substrate under fasting conditions. Figure 5 shows the concentration of triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, and free fatty acids in plasma as a function of circadian time. The concentration of triglycerides in plasma reached its peak at ZT 2, which is the early light/inactive period, and the nadir was at ZT 14 in the 24-h cycle. In contrast, the concentration of LDL cholesterol in the plasma showed exactly the opposite circadian rhythmicity to that of triglycerides, with its peak at ZT 14 in the early dark/active period and the nadir at ZT 2. In the case of plasma free fatty acids, the concentrations were higher during the light/inactive period, with peak concentrations occurring at the mid-light period around ZT 5 and the nadir in the mid-dark/active period. We also measured the concentrations of total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol in the plasma, but no circadian rhythmicity was observed.

Fig. 5.

Concentrations of triglycerides (A), LDL cholesterol (B), and free fatty acids (C) in plasma as a function of circadian time. Shaded areas indicate dark periods, and unshaded areas indicate light periods. Circles represent mean data, with error bars representing 1 SD of the mean, and solid lines represent the curve fitted to a sine function.

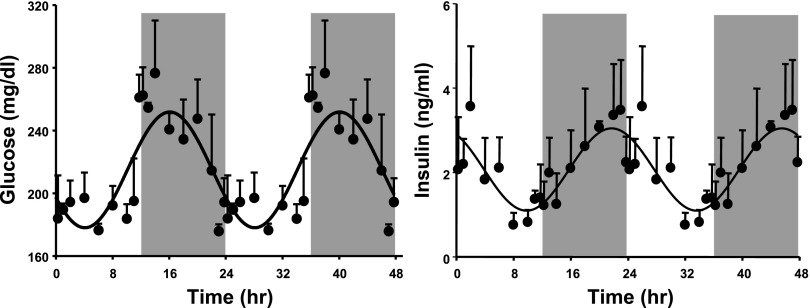

Circadian rhythm in plasma insulin and plasma glucose concentrations.

Insulin is an important hormone that regulates a wide range of physiological functions mainly related to energy metabolism. Figure 6 shows the concentration of plasma insulin and plasma glucose as a function of circadian time. The plasma concentration of insulin reaches its peak at ZT 22 in the late dark/active period and its nadir at ZT 10 in the late light period. In the case of glucose, the plasma concentration reaches its peak at ZT 16 in the dark/active period and its nadir at ZT 4 in the light/inactive period.

Fig. 6.

Concentration of glucose (left) and insulin (right) in plasma as a function of circadian time. Shaded areas indicate dark periods, and unshaded areas indicate light periods. Circles represent mean data, with error bars representing 1 SD of the mean, and solid lines represent the curve fitted to a sine function.

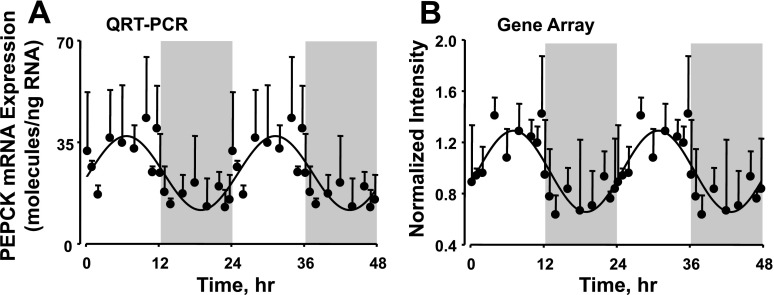

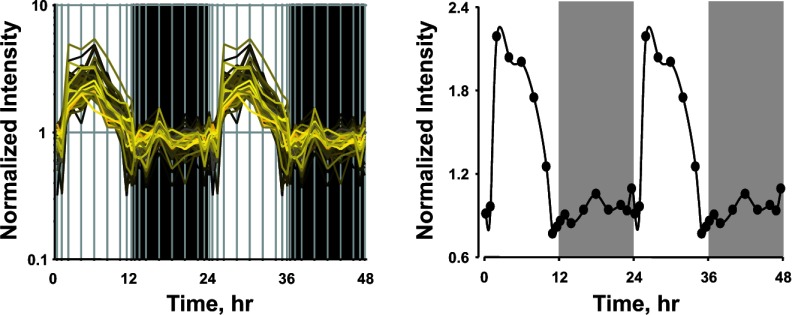

Probe sets showing circadian rhythmicity but not satisfying goodness-of-fit criteria.

In this study the goodness of fit to the sine curve was determined with the R2 value, and probe sets having a value of >0.75 were chosen for further analysis. This represents the 190 probe sets presented in Supplemental Table S2. However, it is possible that this cutoff may exclude some probe sets that show circadian rhythmicity. We therefore visually examined some probe sets for genes that are known to play an important role in adipose tissue function. PEPCK is an enzyme that converts oxaloacetate to phosphoenolpyruvate and has tissue-specific function. In adipose tissue this is the rate-limiting enzyme in glycerologenesis (10). Visual analysis of the probe set for this gene showed that PEPCK does show an apparent circadian rhythmicity in its mRNA expression, but the R2 value was 0.64. To confirm the circadian pattern seen in the microarray we quantified the mRNA expression of this gene as a function of circadian time, using qRT-PCR. Figure 7 shows the expression of PEPCK quantified by microarray and by qRT-PCR. The expression patterns quantified by both methods look very similar, with the peak expression occurring at around ZT 8. Probe sets for other genes including Interleukin 6 receptor (Il6r), Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (Cdkn1b), Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (Pai-1), Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (Ppar) gamma, and Uncoupling protein 3 (Ucp 3) did not pass the goodness-of-fit cutoff for the sine function, but visual inspection of the expression patterns suggested that these probe sets also show circadian rhythmicity in their expression (Supplemental Fig. S3). Interestingly, a group of 76 probe sets showed a very unusual pattern of expression as a function of circadian time as shown in Fig. 8. The expression of these genes did not fit conventional sine or cosine functions that are generally used in the characterization of circadian rhythms. The expression of these genes were relatively constant during the dark/active period but showed a sharp increase in expression at the beginning of the light/inactive period; by the end of the light/inactive period the expression again went back to constant level observed during the dark period. Supplemental Tables S4 and S5 provide the relevant information about the probe sets that show this kind of unusual expression pattern.

Fig. 7.

Circadian pattern of expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) quantified by quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR; A) and Affymetrix gene array chips (B). Shaded areas indicate dark periods, and unshaded areas indicate light periods. Circles represent mean data, with error bars representing 1 SD of the mean, and solid lines represent the curve fitted to a sine function.

Fig. 8.

Expression profiles of probe sets showing unusual patterns of mRNA expression as a function of circadian time. Left: all 76 probe sets that show this unusual pattern. Right: expression pattern of Adiponectin receptor 2, which is one of the genes showing this unusual pattern. Shaded areas indicate dark periods, and unshaded areas indicate light periods.

DISCUSSION

We report here the genomewide microarray analysis of circadian rhythms in mRNA expression in white adipose tissue of the abdominal fat depot along with selected hormonal and physiological parameters that play an important role in the functioning of adipose tissue from male Wistar rats. In this study 54 animals were killed at 18 different time points (n = 3) across the 24-h period (12 h light and 12 h dark). The RNA extracted from the abdominal adipose tissue was hybridized to individual rat 230_2 chips. One aspect of this study that differentiates it from previously published studies is the richness of this data set, which allowed nonlinear fitting to a sinusoidal model and subsequent QT clustering of the data. With this model, 190 probe sets showing robust circadian rhythmicity in expression and that segregated into 7 time clusters were selected for further functional analysis. Another unique and useful aspect of this study is the characterization of hormonal and physiological measurements related to adipose tissue function, which both validates and complements the gene expression data in providing insights into the normal physiological functioning of adipose tissue.

A number of transcription factors are found to be involved in regulating the molecular clock both in the SCN and in peripheral tissues (58). Our study shows that 13 of these transcription factors with probe sets present in rat 230_2 chips displayed robust circadian oscillations in mRNA expression. This suggests that the molecular components of the central clock are well preserved in abdominal adipose tissue, as shown for other peripheral tissues from the same animals (3, 4). These results are also in agreement with the study performed by Zvonic et al. (66) in mouse adipose tissue. Of the remaining five identified clock-related transcription factors, probe sets for Clock, Cry2, Bhlhb2, and RORβ showed very low signal intensities, which suggests that either these genes are not expressed in the tissue or the probe sets are not adequate to measure the expression. Although the probe set for RORα showed a reasonably strong intensity, it did not show any circadian oscillation in expression. Akashi and Takumi (2) showed that RORα displayed a very slight to no oscillation in different peripheral tissues in mice but was still important in regulating the transcription of Bmal1 gene. Since RORα and REV-ERB have opposing effects on transcriptional regulation by binding to the same RORE element, the robust circadian oscillation in REV-ERB expression can cause rhythmicity in RORα-RORE interactions, although the expression of RORα is constant. In contrast to our results, a study by Yang et al. (62) suggests that RORα shows rhythmicity in epididymal fat from the mouse. This kind of contradictory result could arise because of the differences between the two species or if the circadian oscillation of RORα is fat depot specific.

The richness of our data set allowed us to utilize a QT clustering algorithm that groups genes into high-quality clusters based on expression pattern. For some genes, the Rat 230_2 chips contain multiple probe sets for the same gene. As shown in Supplemental Table S2, 17 genes placed under different functional categories were represented by more than 1 probe set (2 for most of the genes except for Nr1d2, TEF, and Fmo2, which are represented by 3 probe sets each). Of these 17 genes, the multiple probe sets for 14 genes fell into the same clustering category. However, in the case of Bteb1, which was represented by two probe sets, one probe set fell into cluster 4 and the other into cluster 5. Similarly, for Tef one probe set fell into cluster 4 but the other two probe sets fell into cluster 5, and for Dtx4 one probe set fell into cluster 1 and the other into cluster 2. The clustering analysis shows that almost 70% of the genes exhibit maximum expression during the dark/active period or the transition from light to dark period. This is consistent with the data analyzed in the liver and muscle tissues from these same animals, suggesting an overall higher transcription rate during the dark/active period (3, 4). Furthermore, the expression of molecular chaperone proteins (Protein Processing category) that are involved in regulating different processes including protein translation, folding, unfolding, and translocation peaks during the dark/active period in the 24-h cycle, which suggests that in addition to more genes showing higher transcription rate, the rates of protein translation and processing are also higher during the dark/active period.

Recent studies have shown a close relationship between circadian machinery and cell cycle progression (6). In fact, some studies have suggested that the core components of the molecular clock may themselves regulate cellular proliferation and differentiation in general and adipogenesis in particular. For example, Shimba et al. (52) showed that Bmal1 plays an important role in both adipogenesis and accumulation of lipids in mature adipocytes. In addition, Nr1d1 was also found to induce adipogenesis similar to Bmal1, and it was hypothesized that regulation of adipogenesis by Bmal1 is at least in part mediated by Nr1d1. Supplemental Table S6 provides a list of genes showing circadian oscillations that are directly or indirectly involved in regulating adipogenesis and adipocyte differentiation. It is interesting to note that many of these proteins regulate adipogenesis by modulating the gene expression or activity of Pparγ, which itself shows circadian oscillations in its expression (Supplemental Fig. S3). This list of genes that are involved in regulating adipogenesis might be incomplete because some genes that are not included in this list such as Camk2n1 (cluster 6) can indirectly affect adipogenesis by inhibiting the activity of CaM-kinase II, which is found to be important for adipocyte differentiation, although no experimental study has been performed to test the direct involvement of Camk2n1 in adipogenesis (59).

It is well accepted that adipose tissue plays an important role in regulating the systemic inflammation and immune response by producing a wide range of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (60). In addition, obesity is considered a condition of low-grade chronic inflammation and is accompanied by increased macrophage infiltration. From our data analysis we found that a number of genes that are involved in regulating this process show circadian rhythms. For example, Cox2 and Hpgd both show oscillations in their expression with almost opposite circadian phases. This result suggests an increase in active production of prostaglandins (which are also proinflammatory) during the early dark/active period similar to other proinflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α that are also present in higher concentrations during the early active period (dark period in rodents and daytime in humans) (15). Hence our data add more credibility to the hypothesis that inflammatory responses in an organism show circadian rhythmicity, with the peak occurring during the early active period. These findings have important implications within the context of inflammatory diseases like arthritis where symptoms worsen during the early active period. Furthermore, the finding that Cox-2 shows rhythmicity in its expression can be very significant in optimizing dosing time for the wide class of Cox-2 inhibitors that are used for the treatment of a large variety of inflammatory disorders.

Endogenous glucocorticoids are important regulators of a wide range of physiological processes including adipogenesis, lipid metabolism, and adipokine expression and secretion by differentially regulating the mRNA expression of many genes (36). As shown in Supplemental Fig. S2, the plasma concentration of endogenous corticosterone peaks during the transition from the light to the dark period (ZT 0). This is consistent with previously published studies in both diurnal and nocturnal mammals in which endogenous glucocorticoid peaks during the transition from the inactive to the active period in the 24-h cycle as an anticipatory response to prepare the organism for activity (11). In this study we also quantitated the mRNA expression of GR as a function of circadian time, and the circadian oscillation in the expression of the receptor looks very similar to that of the hormone. However, it has been well established that glucocorticoid downregulates the expression of its own receptor by negative feedback regulation (7, 13). If the same mechanism applies, and if the circadian rhythm in corticosterone controls the circadian rhythm of the receptor expression, then the nadir of receptor expression should occur within a few hours after the peak of the hormone levels. As shown in Fig. 3, there is a 12-h difference between the peak of the hormone concentration and the nadir of the receptor expression, suggesting that the circadian oscillation in GR mRNA expression is controlled by some other mechanism and not only by the feedback regulation by the hormone. Physiologically this could be a very efficient mechanism because both the hormonal and receptor levels peak at the same time during the transition from inactive to active periods, thereby increasing the physiological effect of the hormone.

Leptin and adiponectin are two major protein hormones produced by adipose tissue. These hormones are produced extensively by mature adipocytes and play an important role in regulating energy homeostasis, with leptin suppressing food intake and stimulating energy expenditure and adiponectin controlling fat metabolism and insulin sensitivity (60). In this study, we quantified both the mRNA expression from adipose tissue and the plasma concentrations of leptin and adiponectin. As illustrated in Fig. 4, leptin shows circadian oscillations in both its mRNA expression and plasma concentrations, with peaks occurring in the late dark/active period and nadirs at the late light period. Since the dark period also represents the active feeding period in rodents, the results suggest that the circadian rhythm in leptin expression could be an anticipatory behavior, with lower levels of the hormone at the beginning of the feeding period to facilitate maximum feeding during this period and levels gradually increasing to maximum concentration at the end of the feeding period to facilitate the suppression of food intake during the upcoming inactive/nonfeeding period. Our results agree with the previous published data by Sánchez et al. (51) in 3-mo-old male Wistar rats that showed that the mRNA expression of leptin from different white adipose tissue depots and serum leptin concentrations show circadian rhythms, with expression/levels increasing during the dark/feeding period and decreasing during the light/inactive period. This study also showed that most of the food intake takes place during the dark/active period. Similar results were also observed in mouse models, and these oscillations are found to be reversed in human subjects (1, 22). In contrast to leptin, adiponectin did not show any rhythmic expression in either its tissue mRNA or plasma protein concentrations.

In addition to hormones including corticosterone and leptin, insulin also shows a distinct circadian rhythm. This hormone produced by the pancreas plays a central role in regulating glucose and energy metabolism. In white adipose tissue, insulin regulates glucose utilization and also influences lipid storage and mobilization by adipocytes. Furthermore, insulin is also important in regulating proliferation and differentiation into mature adipocytes (30). Previous studies have shown that both insulin and glucose levels in the plasma are directly controlled by the SCN, and evidence suggests that the production and secretion of insulin by the pancreas show rhythmic oscillations (5, 31). The data from our study confirm that both insulin and glucose show robust circadian rhythmicity in plasma concentrations. The difference in the phases of the circadian oscillations between plasma insulin and glucose suggests that these rhythms are endogenous and are independent of each other. Furthermore, although the sinusoidal fitting of the plasma glucose data suggests that the peak of the plasma concentration occurs at around ZT 16, the concentrations during the early dark/active period are elevated and do not fall into the predicted curve. This correlates well with the “dawn phenomenon” in humans, where diabetes patients show elevated plasma glucose levels in the early morning hours (active period in humans) (31). The literature data on the circadian oscillations in plasma insulin and glucose concentrations are contradictory, with results ranging from feeble oscillations to strong circadian oscillations with different phase and amplitude (1, 9, 31, 51). Some of the factors that could be causing the difference between these studies could be differences in species, strain, age, animal handling, and duration of light/dark periods. The time of sampling (since most of the studies do not have high-density sampling) could also affect the perceived circadian oscillations in the data. This is one of the main reasons why our study uses such a rich data set for analyzing circadian oscillations. Furthermore, our animal handling and procedures have been designed in such a way as to minimize stress by providing the least possible disturbance to the animals.

In this study we also quantified the concentrations of plasma triglycerides, free fatty acids, and HDL, LDL, and total cholesterol as a function of circadian time. Only plasma triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, and free fatty acids showed circadian oscillations. Triglycerides can be derived from food or can be produced by the liver and adipose tissue in the fed state (state of energy excess) and can be metabolized to free fatty acids that can be used as an energy source during nonfeeding periods. The circadian plasma profiles of these lipids reflect the active/feeding and inactive/nonfeeding periods in the 24-h cycle. The plasma concentration of triglycerides gradually increases during the dark/active period as they are produced during the feeding period and then decreases during the light/inactive period as they are used up during the nonfeeding period. The circadian oscillation of plasma free fatty acids peaks at ZT 5 and shows a 3-h lag from that of plasma triglycerides, which peaks at ZT 2, suggesting that triglycerides are hydrolyzed to free fatty acids during the light period in order to fuel the metabolic processes in the organism during starvation. The circadian oscillations in plasma free fatty acids from our study agree with the previous published data by Stavinoha et al. (53a) in male Wistar rats, and that study suggested that tissue response to free fatty acids also exhibited an diurnal rhythmicity. The circadian oscillation of free fatty acids looks similar to that of Monoglyceride lipase (cluster 3) gene expression, which is involved in hydrolyzing monoglycerides to release free fatty acids (65). On the other hand, LDL contains the maximum concentration of cholesterol as the remaining triglycerides in intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL) are hydrolyzed by capillary lipoprotein lipase (37). The concentration of LDL cholesterol increases during the inactive/nonfeeding or starvation period as triglycerides from very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and IDL are hydrolyzed and the lipoproteins are converted into LDL, which delivers the cholesterol molecules to virtually all cells of the body to be used for cellular structural purposes.

One of the main challenges in analyzing and characterizing circadian rhythms is the use of appropriate mathematical functions and statistical methods to differentiate the genes that show true circadian oscillations. Although many methods to characterize circadian rhythms have been developed in the past, each has its own advantages and disadvantages as reviewed by Refinetti et al. (49). In this study we used nonlinear least-squares fittings to a sinusoidal function, which was feasible because of the richness of our data set. Only probe sets that had R2 values >0.75 were selected for analysis (190 probe sets) and are presented in Supplemental Table S2.

Previously, a microarray study in mouse adipose tissue collected at 4-h intervals reported 4,398 probe sets showing some type of oscillatory expression pattern (66). One of the major differences between that study and ours was our high-density sampling, which provides a rich data set amenable to more refined model fitting and subsequent temporal cluster analysis. Our more stringent selection criteria mined only those genes that exhibited circadian patterns with high similarity to sinusoidal wave function, which is expected for circadian gene expression as followed by many of the clock and clock-controlled genes. This selected a much more limited number of probe sets (190), which could then be temporally and functionally categorized, providing insight regarding the impact of circadian rhythms on adipose tissue physiology. It would have been interesting to compare the probe sets mined in our study with those from that previously published study in mouse adipose tissue; unfortunately, the authors did not provide a list of their mined genes, and those data are not available in public databases. However, a report by Yan et al. (61) presents a reanalysis of that data using a different algorithm, along with a comparison of other circadian data sets in various tissues/species. This reanalysis yielded 897 circadian regulated probe sets in mouse adipose tissue. While a list of these probes is available, the absence of primary data as well as the differences in array platforms and species make a direct comparison difficult.

However, there are two groups of probe sets in our own data set that did not pass the selection criteria, although they did show some kind of circadian oscillation. The first group of probe sets, examples of which are presented in Fig. 7 and Supplemental Fig. S3, did show a sinusoidal rhythm in expression but exhibited higher variability and deviation from the ideal sinusoidal curve. This variability could have a wide range of sources ranging from experimental (e.g., quantification of signal) to biological (e.g., interanimal variability). The other group of probe sets shown in Fig. 8 suggests that genes can also show circadian oscillations that do not follow the classical sinusoidal or cosine function. Unlike the previous case, the probe sets in this group cannot be described appropriately by a sinusoidal model, and their lower R2 value likely results from application of an inappropriate mathematical model rather than true variability. The expression of these genes begins to increase with the onset of light, showing higher expression during the light/inactive period and then decreases to nadir at lights off and is maintained at baseline levels throughout the dark/active period. To our knowledge this is the first study to report circadian oscillations of many genes that show a similar expression pattern that does not follow a conventional sinusoidal or cosine waveform. This observation was possible only because of the high-resolution data available in this study. However, the processes regulating the expression of these genes are still unknown. It is interesting that their pattern of expression appears to be exactly opposite to the pattern of food consumption in rats as reported by Yuan (64).

This study not only confirms, as demonstrated by others, that circadian regulation of gene expression occurs in peripheral tissues but also provides both a temporal and a functional categorization of circadian regulated gene expression in rat white adipose tissue. Many genes exhibited rhythmic 24-h oscillations that adequately fit our model of circadian expression. Among these were 13 previously identified clock-related transcription factors, whose pattern of expression mirrored expression in the central clock. However, temporal patterns of expression of circadian regulated genes differed by phase and amplitude and could be grouped by expression pattern into seven distinct clusters. In addition, a group of genes were identified that exhibited an unusual circadian pattern of expression that did not fit the predicted model. Functional analysis of circadian expressed genes indicated physiological relevance to adipogenesis, energy metabolism, and immune function. Understanding circadian regulation of gene expression has implications for understanding both normal physiological function and potential therapeutic applications. While transcription profiling is valuable in understanding the dynamics and role of circadian regulation, complementing transcription profiling with protein expression and activity studies might be necessary because the time course of protein expression and activity could be different from the mRNA expression for some proteins.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant GM-24211.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental Material for this article is available online at the Journal website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahren B. Diurnal variation in circulating leptin is dependent on gender, food intake and circulating insulin in mice. Acta Physiol Scand 169: 325–331, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akashi M, Takumi T. The orphan nuclear receptor RORalpha regulates circadian transcription of the mammalian core-clock Bmal1. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12: 441–448, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almon RR, Yang E, Lai W, Androulakis IP, DuBois DC, Jusko WJ. Circadian variations in rat liver gene expression: relationships to drug actions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 326: 700–716, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almon RR, Yang E, Lai W, Androulakis IP, Ghimbovschi S, Hoffman EP, Jusko WJ, Dubois DC. Relationships between circadian rhythms and modulation of gene expression by glucocorticoids in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R1031–R1047, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boden G, Ruiz J, Urbain JL, Chen X. Evidence for a circadian rhythm of insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 271: E246–E252, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borgs L, Beukelaers P, Vandenbosch R, Belachew S, Nguyen L, Malgrange B. Cell “circadian” cycle: new role for mammalian core clock genes. Cell Cycle 8: 832–837, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bronnegard M, Reynisdottir S, Marcus C, Stierna P, Arner P. Effect of glucocorticosteroid treatment on glucocorticoid receptor expression in human adipocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80: 3608–3612, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burioka N, Fukuoka Y, Takata M, Endo M, Miyata M, Chikumi H, Tomita K, Kodani M, Touge H, Takeda K, Sumikawa T, Yamaguchi K, Ueda Y, Nakazaki H, Suyama H, Yamasaki A, Sano H, Igishi T, Shimizu E. Circadian rhythms in the CNS and peripheral clock disorders: function of clock genes: influence of medication for bronchial asthma on circadian gene. J Pharmacol Sci 103: 144–149, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cailotto C, La Fleur SE, Van Heijningen C, Wortel J, Kalsbeek A, Feenstra M, Pevet P, Buijs RM. The suprachiasmatic nucleus controls the daily variation of plasma glucose via the autonomic output to the liver: are the clock genes involved? Eur J Neurosci 22: 2531–2540, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakravarty K, Cassuto H, Reshef L, Hanson RW. Factors that control the tissue-specific transcription of the gene for phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase-C. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 40: 129–154, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Challet E. Entrainment of the suprachiasmatic clockwork in diurnal and nocturnal mammals. Endocrinology 148: 5648–5655, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan GK, Deckelbaum RA, Bolivar I, Goltzman D, Karaplis AC. PTHrP inhibits adipocyte differentiation by down-regulating PPARgamma activity via a MAPK-dependent pathway. Endocrinology 142: 4900–4909, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chao HM, Ma LY, McEwen BS, Sakai RR. Regulation of glucocorticoid receptor and mineralocorticoid receptor messenger ribonucleic acids by selective agonists in the rat hippocampus. Endocrinology 139: 1810–1814, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou WL, Chuang LM, Chou CC, Wang AH, Lawson JA, FitzGerald GA, Chang ZF. Identification of a novel prostaglandin reductase reveals the involvement of prostaglandin E2 catabolism in regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activation. J Biol Chem 282: 18162–18172, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cutolo M, Straub RH. Circadian rhythms in arthritis: hormonal effects on the immune/inflammatory reaction. Autoimmun Rev 7: 223–228, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis KE, Scherer PE. Adiponectin: no longer the lone soul in the fight against insulin resistance? Biochem J 416: e7–e9, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunlap JC. Molecular bases for circadian clocks. Cell 96: 271–290, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feder ME, Hofmann GE. Heat-shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and the stress response: evolutionary and ecological physiology. Annu Rev Physiol 61: 243–282, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flajollet S, Lefebvre B, Rachez C, Lefebvre P. Distinct roles of the steroid receptor coactivator 1 and of MED1 in retinoid-induced transcription and cellular differentiation. J Biol Chem 281: 20338–20348, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukuyama R, Niculaita R, Ng KP, Obusez E, Sanchez J, Kalady M, Aung PP, Casey G, Sizemore N. Mutated in colorectal cancer, a putative tumor suppressor for serrated colorectal cancer, selectively represses beta-catenin-dependent transcription. Oncogene 27: 6044–6055, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gachon F. Physiological function of PARbZip circadian clock-controlled transcription factors. Ann Med 39: 562–571, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gavrila A, Peng CK, Chan JL, Mietus JE, Goldberger AL, Mantzoros CS. Diurnal and ultradian dynamics of serum adiponectin in healthy men: comparison with leptin, circulating soluble leptin receptor, and cortisol patterns. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88: 2838–2843, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gimble JM, Ptitsyn AA, Goh BC, Hebert T, Yu G, Wu X, Zvonic S, Shi XM, Floyd ZE. Delta sleep-inducing peptide and glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper: potential links between circadian mechanisms and obesity? Obes Rev 10, Suppl 2: 46–51, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glaser C, Heinrich J, Koletzko B. Role of FADS1 and FADS2 polymorphisms in polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism. Metabolism 59: 993–999, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hackl H, Burkard TR, Sturn A, Rubio R, Schleiffer A, Tian S, Quackenbush J, Eisenhaber F, Trajanoski Z. Molecular processes during fat cell development revealed by gene expression profiling and functional annotation. Genome Biol 6: R108, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hastings JW. The Gonyaulax clock at 50: translational control of circadian expression. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 72: 141–144, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsieh PS, Jin JS, Chiang CF, Chan PC, Chen CH, Shih KC. COX-2-mediated inflammation in fat is crucial for obesity-linked insulin resistance and fatty liver. Obesity (Silver Spring) 17: 1150–1157, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inoue N, Yahagi N, Yamamoto T, Ishikawa M, Watanabe K, Matsuzaka T, Nakagawa Y, Takeuchi Y, Kobayashi K, Takahashi A, Suzuki H, Hasty AH, Toyoshima H, Yamada N, Shimano H. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p21WAF1/CIP1, is involved in adipocyte differentiation and hypertrophy, linking to obesity, and insulin resistance. J Biol Chem 283: 21220–21229, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jetten AM. Retinoid-related orphan receptors (RORs): critical roles in development, immunity, circadian rhythm, and cellular metabolism. Nucl Recept Signal 7: e003, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klemm DJ, Leitner JW, Watson P, Nesterova A, Reusch JE, Goalstone ML, Draznin B. Insulin-induced adipocyte differentiation. Activation of CREB rescues adipogenesis from the arrest caused by inhibition of prenylation. J Biol Chem 276: 28430–28435, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.La Fleur SE, Kalsbeek A, Wortel J, Buijs RM. A suprachiasmatic nucleus generated rhythm in basal glucose concentrations. J Neuroendocrinol 11: 643–652, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laustsen PG, Michael MD, Crute BE, Cohen SE, Ueki K, Kulkarni RN, Keller SR, Lienhard GE, Kahn CR. Lipoatrophic diabetes in Irs1−/−/Irs3−/− double knockout mice. Genes Dev 16: 3213–3222, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee MH, Yang HY. Negative regulators of cyclin-dependent kinases and their roles in cancers. Cell Mol Life Sci 58: 1907–1922, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Legakis I. The role of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) in the pathophysiology of diabetes mellitus. Mini Rev Med Chem 9: 717–723, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li L, Deng B, Xing G, Teng Y, Tian C, Cheng X, Yin X, Yang J, Gao X, Zhu Y, Sun Q, Zhang L, Yang X, He F. PACT is a negative regulator of p53 and essential for cell growth and embryonic development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 7951–7956, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattsson C, Olsson T. Estrogens and glucocorticoid hormones in adipose tissue metabolism. Curr Med Chem 14: 2918–2924, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller NE. Plasma lipoproteins, lipid transport, atherosclerosis: recent developments. J Clin Pathol 32: 639–650, 1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mirsky HP, Liu AC, Welsh DK, Kay SA, Doyle FJ., 3rd A model of the cell-autonomous mammalian circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 11107–11112, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mori T, Sakaue H, Iguchi H, Gomi H, Okada Y, Takashima Y, Nakamura K, Nakamura T, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Kadowaki T, Matsuki Y, Ogawa W, Hiramatsu R, Kasuga M. Role of Kruppel-like factor 15 (KLF15) in transcriptional regulation of adipogenesis. J Biol Chem 280: 12867–12875, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fcgamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 8: 34–47, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Otsuka S, Maegawa S, Takamura A, Kamitani H, Watanabe T, Oshimura M, Nanba E. Aberrant promoter methylation and expression of the imprinted PEG3 gene in glioma. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 85: 157–165, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palming J, Gabrielsson BG, Jennische E, Smith U, Carlsson B, Carlsson LM, Lonn M. Plasma cells and Fc receptors in human adipose tissue—lipogenic and anti-inflammatory effects of immunoglobulins on adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 343: 43–48, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parthun MR. Hat1: the emerging cellular roles of a type B histone acetyltransferase. Oncogene 26: 5319–5328, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peng XD, Xu PZ, Chen ML, Hahn-Windgassen A, Skeen J, Jacobs J, Sundararajan D, Chen WS, Crawford SE, Coleman KG, Hay N. Dwarfism, impaired skin development, skeletal muscle atrophy, delayed bone development, and impeded adipogenesis in mice lacking Akt1 and Akt2. Genes Dev 17: 1352–1365, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Preitner N, Damiola F, Lopez-Molina L, Zakany J, Duboule D, Albrecht U, Schibler U. The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell 110: 251–260, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prusty D, Park BH, Davis KE, Farmer SR. Activation of MEK/ERK signaling promotes adipogenesis by enhancing peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) and C/EBPalpha gene expression during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J Biol Chem 277: 46226–46232, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramsey KM, Marcheva B, Kohsaka A, Bass J. The clockwork of metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr 27: 219–240, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raposinho PD, Pedrazzini T, White RB, Palmiter RD, Aubert ML. Chronic neuropeptide Y infusion into the lateral ventricle induces sustained feeding and obesity in mice lacking either Npy1r or Npy5r expression. Endocrinology 145: 304–310, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Refinetti R, Cornelissen G, Halberg F. Procedures for numerical analysis of circadian rhythms. Biol Rhythm Res 38: 275–325, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature 418: 935–941, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sánchez J, Oliver P, Pico C, Palou A. Diurnal rhythms of leptin and ghrelin in the systemic circulation and in the gastric mucosa are related to food intake in rats. Pflügers Arch 448: 500–506, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shimba S, Ishii N, Ohta Y, Ohno T, Watabe Y, Hayashi M, Wada T, Aoyagi T, Tezuka M. Brain and muscle Arnt-like protein-1 (BMAL1), a component of the molecular clock, regulates adipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 12071–12076, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spencer TE, Jenster G, Burcin MM, Allis CD, Zhou J, Mizzen CA, McKenna NJ, Onate SA, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 is a histone acetyltransferase. Nature 389: 194–198, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53a.Stavinoha MA, RaySpellicy JW, Hart-Sailors ML, Mersmann HJ, Bray MS, Young ME. Diurnal variations in the responsiveness of cardiac and skeletal muscle to fatty acids. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287: E878–E887, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Altieri A, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Cogliano V. Carcinogenicity of shift-work, painting, and fire-fighting. Lancet Oncol 8: 1065–1066, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Summers SA, Yin VP, Whiteman EL, Garza LA, Cho H, Tuttle RL, Birnbaum MJ. Signaling pathways mediating insulin-stimulated glucose transport. Ann NY Acad Sci 892: 169–186, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tint GS, Seller M, Hughes-Benzie R, Batta AK, Shefer S, Genest D, Irons M, Elias E, Salen G. Markedly increased tissue concentrations of 7-dehydrocholesterol combined with low levels of cholesterol are characteristic of the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. J Lipid Res 36: 89–95, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tobin JF, Celeste AJ. Bone morphogenetic proteins and growth differentiation factors as drug targets in cardiovascular and metabolic disease. Drug Discov Today 11: 405–411, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ueda HR, Hayashi S, Chen W, Sano M, Machida M, Shigeyoshi Y, Iino M, Hashimoto S. System-level identification of transcriptional circuits underlying mammalian circadian clocks. Nat Genet 37: 187–192, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang H, Goligorsky MS, Malbon CC. Temporal activation of Ca2+-calmodulin-sensitive protein kinase type II is obligate for adipogenesis. J Biol Chem 272: 1817–1821, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang P, Mariman E, Renes J, Keijer J. The secretory function of adipocytes in the physiology of white adipose tissue. J Cell Physiol 216: 3–13, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan J, Wang H, Liu Y, Shao C. Analysis of gene regulatory networks in the mammalian circadian rhythm. PLoS Comput Biol 4: e1000193, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang X, Downes M, Yu RT, Bookout AL, He W, Straume M, Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM. Nuclear receptor expression links the circadian clock to metabolism. Cell 126: 801–810, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Young ME. The circadian clock within the heart: potential influence on myocardial gene expression, metabolism, and function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H1–H16, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yuan JH. Modeling blood/plasma concentrations in dosed feed and dosed drinking water toxicology studies. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 119: 131–141, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zechner R, Kienesberger PC, Haemmerle G, Zimmermann R, Lass A. Adipose triglyceride lipase and the lipolytic catabolism of cellular fat stores. J Lipid Res 50: 3–21, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zvonic S, Ptitsyn AA, Conrad SA, Scott LK, Floyd ZE, Kilroy G, Wu X, Goh BC, Mynatt RL, Gimble JM. Characterization of peripheral circadian clocks in adipose tissues. Diabetes 55: 962–970, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.