Abstract

In humans, environmental exposure to a high dose of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) protects from allergic asthma the immunological underpinnings of which are not well understood. In mice, exposure to a high LPS dose blunted house dust mite-induced airway eosinophilia and Th2 cytokine production. While adoptively transferred Th2 cells induced allergic airway inflammation in control mice, they were unable to do so in LPS-exposed mice. LPS promoted the development of a CD11b+Gr1intF4/80+ lung-resident cell resembling myeloid-derived suppressor cells in a TLR4- and MyD88-dependent fashion that suppressed lung dendritic cell (DC)-mediated reactivation of primed Th2 cells. LPS effects switched from suppressive to stimulatory in MyD88-/- mice. Suppression of Th2 effector function was reversed by anti-IL-10 or inhibition of Arginase 1. Lineageneg bone marrow progenitor cells could be induced by LPS to develop into CD11b+Gr1intF4/80+ cells both in vivo and in vitro which when adoptively transferred suppressed allergen-induced airway inflammation in recipient mice. These data suggest that CD11b+Gr1intF4/80+ cells contribute to the protective effects of LPS in allergic asthma by tempering Th2 effector function in the tissue.

Keywords: LPS, lung, myeloid cells, asthma, suppression

Introduction

The incidence of atopy and asthma has greatly increased over recent years concomitant with an improved hygienic status in the industrialized world. This suggests some form of environmental control on the development of allergic diseases. The hygiene hypothesis was invoked in 1989 to explain the inverse relationship between the risk of an allergic disease, hay fever, and family size 1. This hypothesis contends that in recent years, reduced microbial exposure in early life due to improved sanitary conditions and altered lifestyles has caused an increase in allergic diseases including asthma in developed countries. Several studies have supported the concept of the hygiene hypothesis. For example, an inverse association was noted between delayed-type hypersensitivity responses to tuberculin, a measure of responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and serum IgE titer, an indicator of the allergic burden 2. A lower incidence of allergic disease was reported in children enrolled early in day care 3. High levels of endotoxin, measured in dust samples collected from mattresses, was shown to be inversely related to the occurrence of hay fever, atopic asthma and atopic sensitization among children raised in farms in rural areas in Europe 4. Initially, this observed inverse relationship between LPS and allergic disease was attributed to Th1/Th2 cross-regulation 2,5. However, it has become apparent after many studies that the underlying mechanism of the hygiene hypothesis is not Th1/Th2 cross-regulation. For example, in the studies of von Mutius and colleagues, LPS exposure was found to correlate with the inability of the children's blood leukocytes to produce both Th1 and Th2 cytokines demonstrating an overall down-regulation of immune responses 4. It should be noted that not only have atopic diseases been on the rise in recent years, but so have autoimmune diseases such as diabetes mellitus and multiple sclerosis 6 such that investigators have begun to search for a common denominator for this increase in immune-mediated disorders. The contribution of immunosuppressive mechanisms underlying the hygiene hypothesis is being increasingly entertained 4.

To better understand the mechanism by which LPS inhibits allergic responses, we examined the effect of LPS on the status of myeloid cells in the lung in adult mice. Continual exposure to LPS induced the generation of a suppressive myeloid cell type that expressed CD11b, Gr1 at intermediate levels and F4/80, the combination of which distinguished it from neutrophils, macrophages and dendritic cells. The cells resembled previously described hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell-derived myeloid cells in specific tissues including the lung whose numbers were shown to expand in the presence of TLR agonists such as LPS 7. The LPS-induced myeloid cells did not traffic to lung-draining lymph nodes (LNs) and did not affect T cell functions in the LNs. However, the cells suppressed Th2 effector function in the lung tissue, which was in alignment with their tissue-dwelling characteristic. DC-induced STAT5 activation, GATA-3 upregulation and cytokine production in primed Th2 cells were inhibited by the LPS-induced myeloid cells. The cells could be generated by a combination of LPS and GM-CSF from lineageneg progenitor cells. Adoptive transfer of the in vitro- or in vivo-derived cells efficiently inhibited allergen-induced airway inflammation. Our findings show that exposure of the lungs of adult mice to a high dose of LPS induces a myeloid suppressive cell type that serves to temper the function of effector Th2 cells.

Results

Exposure of the lung to bacterial lipopolysaccharide promotes a CD11b+Gr1int F4/80+ cell-type that is distinct from neutrophils

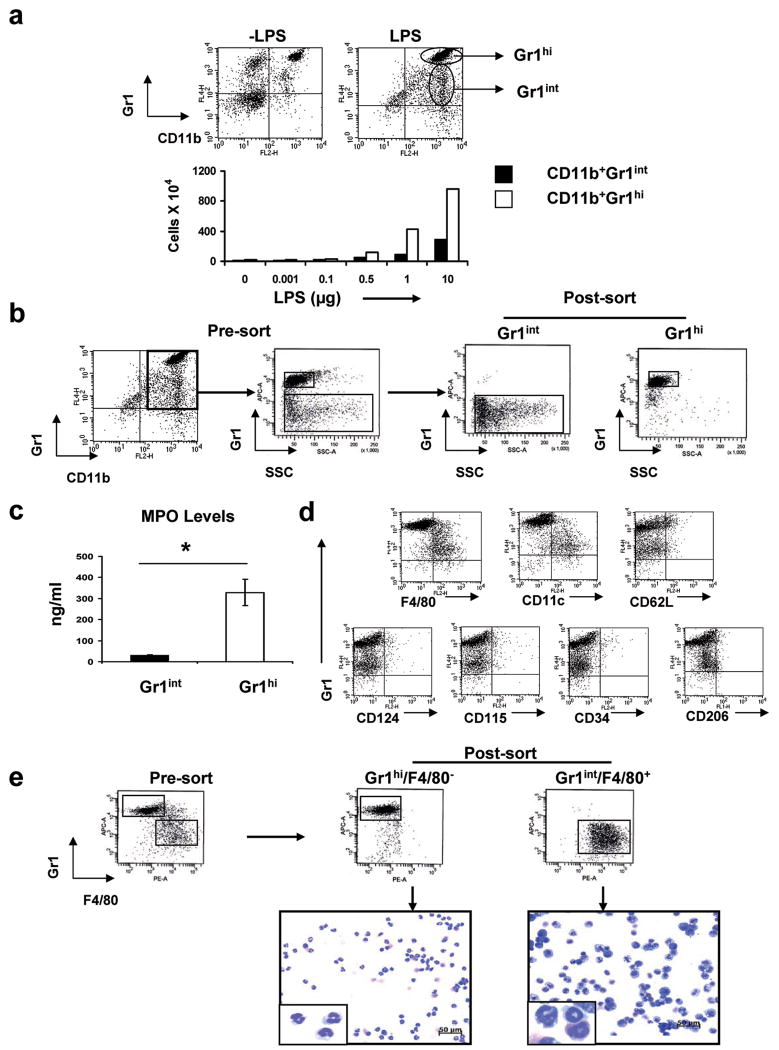

LPS has been associated with both promotion and inhibition of allergic airway inflammation. A dose lower than 1 ng of LPS induces tolerance, ∼100 ng promotes allergic airway inflammation while a higher dose (μg range) inhibits the same process 8,9. LPS in the range of 30,000 endotoxin units (3 μg)/m2 of mattress surface area was detected in farms where children were found to be protected from allergic diseases including hay fever and asthma 4. We examined the effect of different doses of LPS on the frequency of CD11b+Gr1+ cells since this dual expression would be expected to reveal neutrophils, which should be recruited by LPS to the lungs. Interestingly, LPS not only caused the expected increase in the frequency of a CD11b+Gr1hi population, but a second population, with the phenotype CD11b+Gr1int, was also promoted by LPS (Figure 1a). The frequency of the CD11b+Gr1int population increased with each instillation of LPS and was discernible as early as 24 h after the first instillation. To characterize each population further, the cells were sorted as shown (Figure 1b). As expected, the Gr1hi population showed myleoperoxidase (MPO) activity characteristic of neutrophils but the Gr1int cells did not express MPO (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

LPS administration increases the frequency of CD11b+Gr1+F4/80+ cells in the lung. Lung cells were isolated by enzymatic digestion of lung tissue. The cells were stained with anti-CD11b and anti-Gr1 monoclonal antibodies and were analyzed by flow cytometry. The forward versus side light scatter pattern revealed a distinct non-lymphocytic population of cells where CD11b-expressing and Gr1-expressing cells were concentrated (data not shown). This population of cells was gated upon for subsequent analyses. (a) Expression of CD11b and Gr1 on lung cells measured by flow cytometry with or without LPS treatment of mice (upper panels). The numbers of CD11b+ cells expressing high (hi) or intermediate (int) levels of Gr1 were determined in response to increasing concentrations of LPS per treatment (lower panel). (b) Two populations of CD11b+ cells from the lungs of LPS-treated mice were sorted based upon expression of intermediate (Gr1int) or high (Gr1hi) levels of Gr1. The purity of Grint and Grhi populations was more than 95%. (c) Levels of MPO in the supernatants of Grint and Grhi populations were detected using an ELISA kit for MPO. *, P<0.05. (d) Expression of F4/80, CD11c, CD124, CD115, CD62L, CD34 and CD206 on the LPS-induced CD11b+Grint cells by flow cytometry. Cursors are placed based on staining with isotype control antibodies. (e) CD11b+ cells isolated from the lungs of LPS-treated mice were sorted based upon expression of Gr1 and F4/80 (upper panels). The purity of CD11b+Gr1intF4/80+ and CD11b+Gr1hiF4/80- cells was >94%. Cytospin slides were prepared and stained using the 3-Step Stain kit (Richard-Allan Scientific). CD11b+/Gr1hi/F4/80- cells were identified as neutrophils with characteristic lobular-shaped nuclei. The CD11b+Gr1int/F4/80+ cells appeared to be a heterogeneous population with the majority containing ring-shaped nuclei (inset) (lower panels). The data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

The cells were also examined for the expression of F4/80 which is not expressed by neutrophils10,11. While the neutrophils were F4/80-, the Gr1int cells were F4/80+. Collectively, the features of the Gr1int cells resembled those of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) isolated from tumor sites that have the phenotype CD11b+Gr1+F4/80+ 12. We also, examined the expression of other molecules such as CD115 (M-CSF receptor), CD124 (IL-4 receptor α chain), CD62L, CD34 and CD206, which have been associated with tumor-infiltrating MDSCs 13. However, the expression of these molecules is not essential for the suppressive function of MDSCs 12. The CD11b+Gr1int F4/80+ cells induced by LPS in the lung did not express CD115, CD124, CD62L, CD34 or CD206 (Figure 1d). The LPS-induced cells also expressed intermediate/low levels of CD11c. As shown in Figure 1e, the Gr1hi and Gr1int populations were morphologically distinct. As expected, the CD11b+Gr1hiF4/80- cells exhibited neutrophil-like morphology with characteristic lobular shaped nuclei. Morphological assessment of CD11b+Gr1intF4/80+ cells revealed the presence of myeloid cells similar to the Gr1+CD11b+ cells described in murine models of cancer and trauma with many cells showing the presence of ring-shaped nuclei 12-14.

Since specific antibodies recognizing the two epitopes of Gr1, Ly6C and Ly6G, are available (anti-Gr1 recognizes both), we also characterized the LPS-induced Gr1int cells on the basis of expression of the two epitopes. The non-neutrophilic LPS-induced cells consisted of 2 subsets based on their differential Ly6C expression. Among the CD11b+ cells gated on F4/80 expression, Ly6GintLy6C- was the dominant population expanded by LPS treatment with the Ly6GintLy6Clo population being the minor subset (right panel in Supplementary Figure 1). Since inflammatory monocytes express Ly6C but do not express Ly6G 15, the Gr1int cells did not appear to be inflammatory monocytes.

The CD11b+Gr1int F4/80+ cell type is phenotypically distinguishable from lung dendritic cells

We next compared the Gr1int cells with conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) isolated side-by-side from the lungs of the same LPS-treated mice, the DCs being identified based on CD11c expression and low autofluorescence (Figure 2a). The cells were cultured briefly to identify the cytokines they produce. The CD11b+Gr1intF4/80+ cells produced higher levels of IL-6 and GM-CSF as compared to equal numbers of cultured cDCs (Figure 2b). The cDCs, however, secreted more IL-12p40 (Fig. 2b). The cDCs expressed higher levels of cell surface markers such as MHC class II, CD86 and CD40 and the reverse was true for CD80 (Figure 2c). High level of CD80 expression is a characteristic of MDSCs and is important for their suppressive function 16. The CD11b+Gr1int cells have considerable similarity to MDSCs including the expression of CD80. Given that the Gr1int cells resembled MDSCs, we also examined nitric oxide production by the cells and as shown in Figure 2d, the cells produced NO which was more than that produced by cDCs. For convenience, from here on we have referred to the LPS-induced myeloid cells as CD11b+Gr1int to distinguish them from neutrophils that are CD11b+Gr1hi and lung cDCs in which this phenotype has not been encountered.

Figure 2.

CD11b+Gr1intF4/80+ cells induced by LPS administration are distinct from conventional lung DCs. (a) CD11c+ cells were purified from the lung cells obtained from LPS-treated mice. Conventional DCs were identified as CD11c+ cells with a relatively low level of autofluorescence and side scatter and were used as APCs in experiments where needed. The purity of these cells was more than 95%. (b) 2×105 cells (cDCs or CD11b+Gr1intF4/80+ cells) were plated for 20 h and culture supernatants were analyzed for cytokine production. Values shown are mean ± SEM, *, P<0.01, **, P< 0.001. (c) Expression of co-stimulatory molecules detected by flow cytometry on the cDC and CD11b+Gr1int F4/80+ populations. Dark lines represent expression of the indicated molecules, the light lines being background fluorescence determined by staining with appropriate isotype control antibodies. (d) Levels of NO in the supernatants of cell cultures. DC and Gr1int/F4/80+ were isolated from the same LPS-treated mice as described before. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments and depict mean ± SD *, P<0.05.

Lineageneg progenitors develop into CD11b+Gr1int cells in the lung in the presence of LPS but do not migrate to draining lymph nodes

A previous study showed that migratory hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) proliferate within extramedullary tissues such as the lungs and kidneys in response to LPS and give rise to myeloid cells that express CD11c with a subset also expressing Gr1 at intermediate levels 7. It was suggested that an important function of the migratory HSPCs is rapid expansion into innate cells of the immune system after sensing danger signals such as TLR agonists so that an aggressive immune response can be expeditiously mounted against the invading pathogen 7. We, therefore, wished to determine whether infusion of GFP+ lineageneg (lin-) bone marrow progenitor cells into naïve mice and subsequent LPS instillation into lungs would promote the development of GFP+CD11b+Gr1int cells. Figure 3a (left panel) depicts the quality of lin- cells isolated from bone marrow progenitor cells which express high levels of c-kit but low levels of Gr1 unlike the lin+ fraction. As shown in Figure 3a (right panel), after intravenous injection of the lin- GFP+ cells, 10 fold more GFP+ CD11b+Gr1int cells were detected in the lungs of LPS-treated mice compared to that in the lungs of control mice.

Figure 3.

The CD11b+Gr1int cells do not migrate to the lung-draining lymph nodes and LPS instillation in the lung does not inhibit CD4+ T cell proliferation in the LNs. (a) The lin- population in bone marrow cells was enriched using a lineage depletion kit and phenotypic analysis was performed by flow cytometry. Also, shown is the phenotypic analysis of the lin+ fraction. The lin- population of bone marrow cells was enriched from EGFP transgenic mice and transferred intravenously (i.v.) into naïve mice. Mice were divided into two groups and one group then received three daily treatments of 10μg LPS while the other group was left untreated. The top right panel shows the presence of GFP+ cells in the lung after transfer of GFP+ lin- cells. The forward versus side light scatter pattern revealed a distinct non-lymphocytic population of cells where CD11b- and Gr1-expressing cells were concentrated (data not shown). This population of cells was gated on for subsequent analyses. Within the GFP gate, the percentage of cells expressing intermediate (int) levels of Gr1 were determined in the presence or absence of LPS (lower panel). (b) CD11c+ and CD11b+ cells were purified from the lung cells obtained from LPS-treated mice. Expression of CCR7 on low autofluorescent CD11c+ and CD11b+ cells was detected by flow cytometry. (c) Expression of CD11b and Gr1 on LN cells measured by flow cytometry with or without LPS treatment of mice. The histogram shows CCR7 levels on CD11c+ cells obtained from LN cells of LPS-treated mice. Thin gray lines indicate staining with appropriate isotype control antibody and the overlay represents expression of the CCR7 molecules. The last panel shows a ∼30-fold increase in the number of CD11c+Gr1- cells in the LNs in LPS-treated mice. Data represent average values obtained from 3 independent experiments ± SD **, P<0.005. (d) TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells were isolated from the spleens of DO11.10 mice. The cells were labeled with CFSE and adoptively transferred to either naïve or LPS-treated mice (four daily treatments with 10 μg/treatment of LPS). Beginning one day after adoptive transfer, the mice received OVA/CT once per day for 2 d. 24 h later, the number of KJ-126+ (DO11.10), CFSE-expressing cells in the lung-draining lymph nodes was determined (upper panel), and the degree of cell proliferation was quantitated based upon CFSE dilution (lower panels). Results shown are representative of two independent experiments.

The earlier study also showed that the HSPCs lack CCR7 and do not migrate to lymph nodes draining tissues 7. To further determine the similarity of the previously described HSPC-derived cells, we also stained cells with anti-CCR7. The CD11b+Gr1int cells isolated from the lung were all largely CCR7- while CD11c+CCR7+ cells were detected in the lung (Figure 3b). CD11b+Gr1int cells were not detectable in the LNs of the LPS-treated mice (Figure 3c). However, as expected, we observed a ∼30 -fold increase in the number of DCs in the LN upon LPS treatment (Figure 3c). Given that these data showed that the CD11b+Gr1int cells do not traffic to the lung-draining LNs, we reasoned that effects on CD4+ T cells in the LNs such as proliferation would not be any different in LPS-treated mice as compared to that in the LNs of control mice. Indeed, LPS administration into the lungs of mice did not cause inhibition of proliferation of CD4+ T cells in LNs as studied by transfer of CFSE-labeled naïve CD4+ T cells and assessment of CFSE dilution in proliferating cells (Figure 3d).

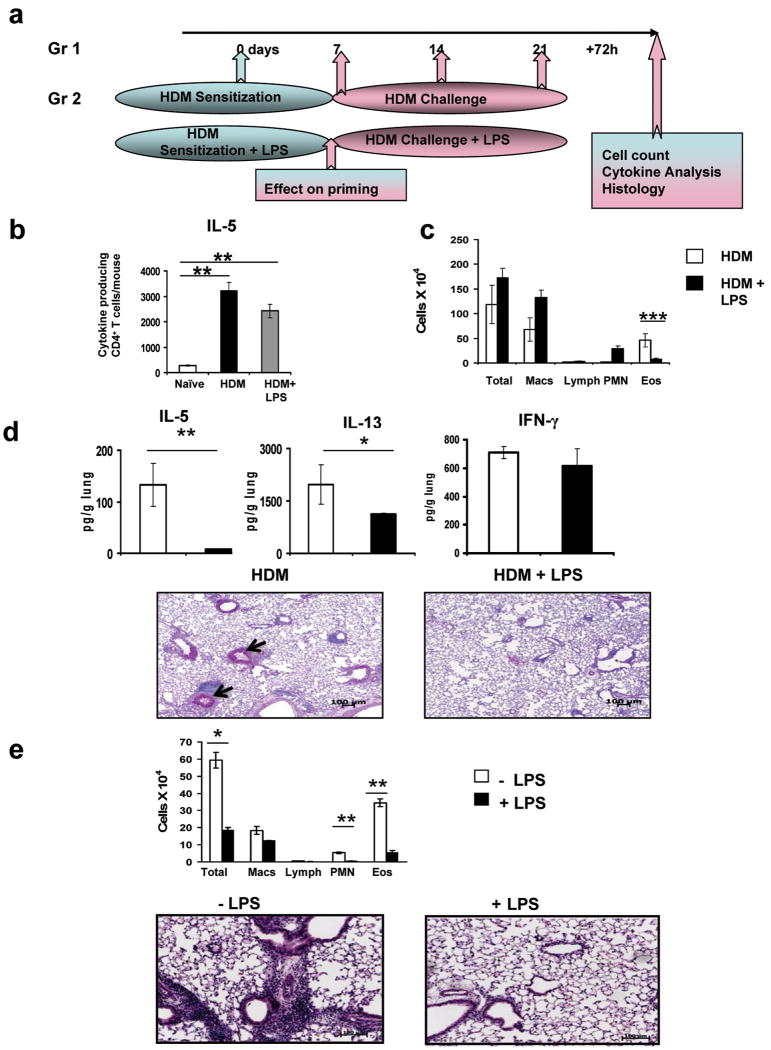

High LPS dose blunts allergen-induced allergic airway inflammation and Th2 effector function in the lung

Since our experiments suggested that the LPS-induced CD11b+Gr1int cells did not traffic to the lung-draining LNs, as was also observed in the prior study 7, our next question was whether these cells would temper effector T cell responses in the tissue. We chose a mouse model of allergic airway inflammation induced by the common household allergen, house dust mite (HDM) (Figure 4a). Mice were sensitized and challenged with HDM 17. After one instillation of HDM and allowing time for priming, we assessed IL-5+ CD4+ T cells by ELISPOT assay in the lung-draining LNs. As shown in Figure 4b, significantly greater numbers of IL-5+ CD4+ T cells were discernible in the LNs of both HDM and HDM+LPS groups as compared to that in the LNs of naive mice again demonstrating that a high dose of LPS had minimal effects at the LN level. The slightly lower numbers of IL-5+ cells under conditions of HDM+LPS should be considered in light of the fact that activated T cells can enter LNs from tissues via afferent lymphatics 18. Thus, the number of effector T cells in the draining LNs after immunization is governed by two criteria- cells that remain in the LN and those that migrate to the antigen-delivery site and reenter the lymph node via the afferent lymph. Since all of our evidence indicated that the CD11b+Gr1int cells develop in the lung without detectable presence in the LNs, we did not expect to see any influence on effector response in the LNs soon after priming which is what we observed. However, when the lungs were examined after 3 rounds of challenges with the allergen alone or in the presence of LPS, a significant reduction in airway inflammation as well as Th2 cytokine levels in the lung was observed when LPS was mixed with HDM (Figure 4, panels c and d). Thus, LPS treatment induced a condition in the lung that did not favor effector Th2 responses. Most importantly, LPS did not cause more IFN-γ production in the lung suggesting that the inhibition was not due cross-regulation by this cytokine. If our inference was correct that the LPS-induced tissue-dwelling myeloid cells would suppress Th2 effector function in the lung, we expected in vitro- generated Th2 cells to be unable to induce inflammation in the airways of LPS-treated mice. To test this, Th2 cells were generated in vitro by repetitive stimulation of CD4+ (DO11.10) T cells under Th2-skewing conditions. The cells were then adoptively transferred into control and LPS-treated mice and the cells were recruited to the lung by challenge with aerosolized OVA 19,20}. There was a remarkable difference in the level of airway inflammation between the LPS-treated and untreated groups with severe inhibition observed when cells were transferred into LPS-treated mice (Figure 4e). This observation was in line with a previous report in which intravenous LPS administration was shown to suppress experimental asthma in a NOS2-dependent fashion although the mechanism for this observation was not identified 9.

Figure 4.

Suppression of HDM- and TH2 cell-induced eosinophilic inflammation in the airways by LPS. (a) Diagram of the treatment protocol. HDM (100 μg per mouse) ± LPS (10 μg LPS per mouse) was administered intratracheally (i.t.) at the indicated time points. Lung-draining LNs were harvested from one group 7 days after one HDM instillation ± LPS to assess CD4+ T cell priming. The rest of the animals were challenged with HDM ± LPS and at 72 h after the final instillation, BAL fluid and lung tissue samples were obtained. (b) ELISPOT assay of cells harvested from lung-draining LNs. Naive mice were used as control. For all the groups, the total cell population was used for ELISPOT assay and the number of cytokine-expressing Th cells was estimated based upon the percentage of CD4+ T cells determined by flow cytometry. For the HDM and HDM+LPS groups, CD4+ T cells were also purified by magnetic bead selection prior to being subjected to the assay to confirm that the cytokines were being produced by CD4+ T cells. In all cases, cells were stimulated for 8-10 h with PMA (25 ng/ml) plus ionomycin (500 ng/ml). Results are expressed as the number of cytokine-producing cells per sample. Data shown are mean ± SD **, P <0.01. The data shown are representative of two independent experiments. (c) Counts of cells recovered in the BAL fluid. Values are mean + SEM ***, P<0.005. (d) The concentrations of IL-5, IL-13 and IFN-g in lung homogenates were measured by multiplex assay and are presented as mean ± SEM *, P<0.05 and **, P<0.01. Histological examination of lung sections stained with PAS for assessment of inflammation and mucus production. Lung infiltrates around bronchovascular bundles where eosinophilic response is most pronounced in disease were of +4 grade in animals that received HDM and +1/2 in those that received LPS together with HDM. Arrows indicate mucus staining. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (e) Th2 cells were generated in vitro using CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 mice and were injected i.v. into either LPS-treated mice or naïve recipient mice (5 × 106 cells/mouse). The mice were then exposed to aerosolized OVA daily for 7 days and were analyzed 24 h after the last exposure. Total and differential counts of cells recovered in the BAL fluid (upper panel) and H&E staining of lung sections (lower panels) of both group of mice were performed. Values are mean ± SEM *, P<0.01 and

**, P<0.001. The data shown are representative of two independent experiments.

LPS-induced development of CD11b+Gr1int cells is dependent on MyD88 but not TRIF and inhibition of eosinophilic inflammation by LPS is abolished without MyD88

Our next goal was to determine which of the TLR4-induced pathways, MyD88-dependent or -independent (via TRIF), was responsible for the generation of our cell of interest. To match their genetically altered counterparts, WT control mice used for the MyD88-/- mice were on Balb/c background while those for the TRIF-/- animals were on C57BL/6 background. We were able to generate the CD11b+Gr1+ cells in the presence of GM-CSF+LPS but not with either agent alone from lineage- bone marrow progenitor cells (Supplementary Figure 2). GM-CSF alone induced DC development as is standard for generation of bone marrow-derived DCs from mouse cells. No difference in the generation of the CD11b+Gr1int cells has been noted by us whether bone marrow cells are derived from Balb/c or C57BL/6 mice. Cells developed under both conditions expressed the myeloid marker CD11b. In contrast to 80-90% of the cells generated in the presence of GM-CSF being conventional CD11c+ DCs, simultaneous stimulation with LPS reduced CD11c+ cells to less than 5% (Supplementary Figure 2). The lung CD11b+Gr1+ cells were found to express CD11c (Figure 1d), but at a lower level compared to expression by lung cDCs. The GM-CSF+LPS-induced cells also expressed Gr1 and Thy1.2, the latter being only found on the in vitro-generated cells. Interestingly, Thy1.2 expression on a minor subset of splenic CpG ODN-induced CD11c+ DCs was previously described 21. MyD88- but not TRIF-deficiency blocked generation of Gr1+ cells from bone marrow cells in the presence of GM-CSF and LPS (Figure 5a). To further strengthen this observation, we took a complementary approach of culturing bone marrow cells with GM-CSF and poly (I:C), a TLR3 ligand which only signals via TRIF. Unlike LPS, different doses of poly (I:C) when combined with GM-CSF did not induce generation of the CD11b+Gr1int cells (data not shown). To determine the role of MyD88 in vivo, TLR4-/- and MyD88-/- mice were treated with LPS and the frequency of the CD11b+Gr1int cells in their lungs was compared with that in untreated mice. As shown in Figure 5b, the CD11b+Gr1int cells in the lungs of LPS-treated TLR4-/- and MyD88-/- mice increased by only ∼8- and 4-fold respectively as compared to 63-fold in WT mice.

Figure 5.

MyD88-dependence of development of CD11b+Gr1int cells. (a) Bone marrow cells were cultured with GM-CSF and LPS for 9 days and phenotypic analysis was performed using flow cytometry. The resulting cells from wild-type Balb/c mice were compared to those from MyD88-deficient (MyD88-/-) mice (left-hand panel), and those from wild-type C57BL/6 mice were compared to TRIF-deficient (TRIF-/-) mice (right-hand panel). (b) Estimation of fold-induction of CD11b+Gr1int cells in response to LPS in the lungs of WT, TLR4-/- and MyD88-/- mice. (c) MyD88 -/- mice received HDM ± LPS i.t. as in Figure 4a. 72 h after the final instillation, BAL fluid and lung tissue samples were obtained. Total and differential counts of cells recovered in the BAL fluid (left-hand panel) and H&E staining of lung sections (right-hand panels) were performed. Values shown are mean ± SD, *, P<0.05, **, P<0.005. The concentration of IL-5 in lung homogenates was measured by multiplex assay and is presented as mean ± SEM ***, P<0.001. The data shown are representative of two independent experiments.

To functionally ascertain the influence of LPS on HDM-induced allergic responses in the absence of MyD88, WT and MyD88-/- mice were sensitized and challenged with HDM in the presence or absence of LPS. Interestingly, the MyD88-/- mice displayed attenuated airway inflammation compared to WT mice in response to HDM (please compare with inflammatory response in WT mice as shown in Figure 4). Recently, Der p 2, a key allergen of HDM, was shown to be a mimic of the TLR4-associated adaptor MD-2 and provide this essential component of LPS-induced TLR4 signaling in lung epithelial cells which lack MD-2 22. Similarly, TLR4 signaling in epithelial cells was shown to be important for HDM-induced allergic airways disease 23. In line with these observations, the MyD88-/- mice mounted less airway inflammatory response although it was not totally absent (Figure 5c). Interestingly, almost twice the number of cells could be recovered in the BAL fluid when LPS was administered together with HDM in the MyD88-deficient mice compared to that obtained with HDM alone (Figure 5c). The results of these experiments showed that the absence of MyD88 abolishes the suppressive function of a high dose of LPS. However, given that the TRIF/type I IFN pathway stimulates the expression of costimulatory molecules 24, it is likely that LPS augmented HDM-induced airway inflammation in MyD88-/- mice not only because of a reduction in the number of CD11b+Gr1int cells in the absence of MyD88 but also due to preservation of the second pathway, TRIF, downstream of TLR4. Along with increased eosinophilic airway inflammation, the HDM/LPS combination also yielded more IL-5 in the lung as compared to treatment with HDM alone (Figure 5c).

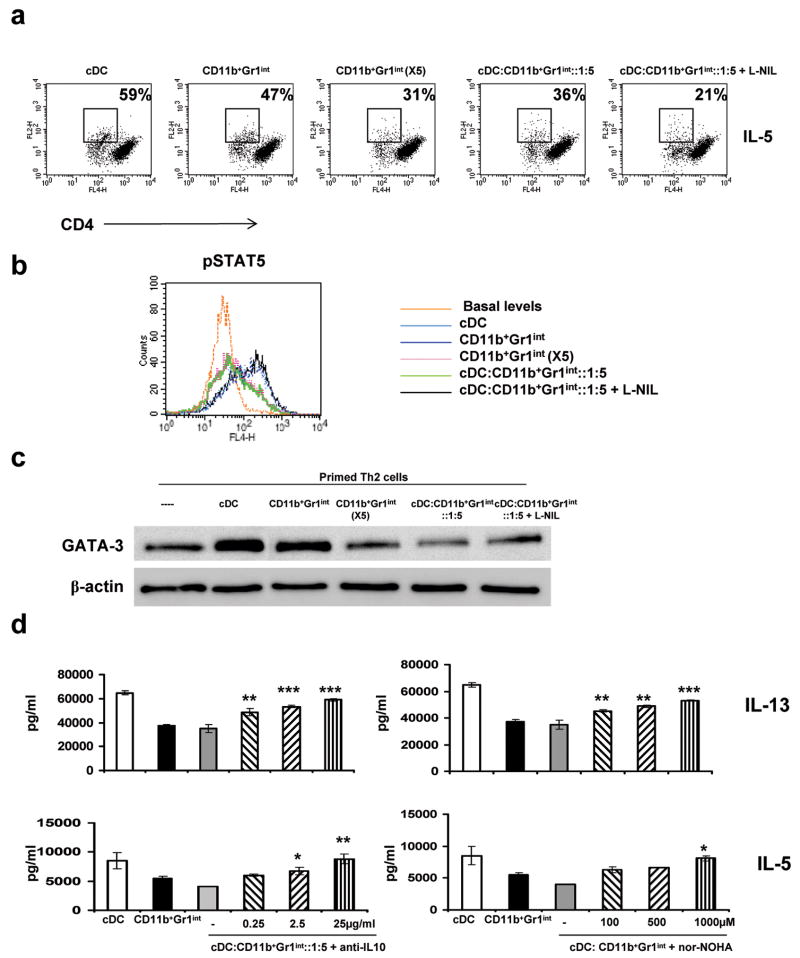

Activation of Th2-primed cells by lung DCs is inhibited by CD11b+Gr1int cells with effects on STAT5 phosphorylation and GATA-3 expression

We next sought to determine whether the CD11b+Gr1int cells could block activation of transcription factors such as STAT5 and GATA-3 in freshly primed Th2 cells. GATA-3 is the key regulator of Th2 differentiation as previously described by us and others 25-29 and a role for STAT5 in Th2 differentiation has also been shown 30,31. The protocol of priming involving 6 days of culture under Th2-skewing conditions does induce GATA-3, albeit in at low levels in a small fraction of the CD4+ T cells, as judged by expression of GATA-3-dependent genes such as T1ST2 31. Administration of anti-T1ST2 into mice blocks the effector function of adoptively transferred OVA-specific Th2 cells including Th2 cytokine secretion and eosinophilic airway inflammation. The expression of T1ST2 has been recently shown to require GATA-3 and activated STAT5 31. We reasoned that if both STAT5 and GATA-3 are required for expression of Th2 cytokine genes and other Th2 expressed molecules such as T1ST2, the efficient Th2 suppression observed in vivo (Figure 4) might be due to the inability of primed Th2 cells migrating into tissue to be reactivated by tissue DCs resulting in GATA-3 upregulation and STAT5 activation. We, therefore, asked whether stimulatory effects of lung cDCs on the primed Th2 cells would be compromised by the LPS-induced lung CD11b+Gr1int cells. As measures of Th2 activation, we examined Th2 cytokine production, STAT5 phosphorylation and GATA-3 expression (Figure 6). The frequency of IL-5-secreting Th2 cells was ascertained by intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) after coculture of the primed Th2-skewed cells with either lung cDCs, CD11b+Gr1int cells, or their mixture for 36 h as shown in Figure 6a. The ratio of DC to CD11b+Gr1int cells used was 1:5 based on our quantitation of these cells in the lungs after LPS administration over a 4 day time period which ranges from 5-10-fold more than cDCs. As expected with specific antigen-induced stimulation, as opposed to PMA plus ionomycin which would activate all primed T cells, a fraction of CD4 cells displayed blast-like (activated) morphology (by FSC vs SSC, data not shown) as well as typically lower CD4 expression32,33. Among reactivated CD4 cells (reduced CD4 expression), the frequency of IL-5-secreting cells was greater with stimulation by lung cDCs as compared to lung CD11b+Gr1int cells (Figure 6a). 5-fold more CD11b+Gr1int cells reduced cytokine production by 55.0 ± 3.5%. However, as expected, the addition of 5-fold more lung cDCs slightly increased cytokine production (data not shown). Furthermore, IL-5 production was inhibited when the cDCs were mixed with the CD11b+Gr1int cells in a 1:5 ratio by 60.7 ± 2.4 % (Figure 6a). The inhibition was not reversed when the NOS2 inhibitor L-NIL was used. We next cocultured the primed Th2 cells with cDCs or CD11b+Gr1int cells as above, removed the culture supernatant and exposed the cells briefly to IL-2 to assess STAT5 phosphorylation. IL-2 was able to induce STAT5 phosphorylation in cells cocultured with lung DCs and same numbers of CD11b+Gr1int cells but not when 5 fold more CD11b+Gr1int cells were used (Figure 6b). When added to cDCs, the cells partially inhibited STAT5 phosphorylation which was reversed by L-NIL. The reversal of suppression by L-NIL was expected since NO blocks Jak3-mediated STAT5 activation34,35. With respect to GATA-3 expression, lung cDCs induced an increase in GATA-3 expression in the primed Th2 cells. Similar to results obtained for STAT5 phosphorylation, equal numbers of CD11b+Gr1int cells as cDCs also caused GATA-3 upregulation. However, at 5-fold higher numbers and when mixed with DCs, GATA-3 upregulation was not achieved (Figure 6c). Of note, however, the cells maintained a low level of GATA-3 expression. Addition of L-NIL only slightly reversed GATA-3 expression (Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

CD11b+Gr1int cells induced by LPS administration suppress Th2 cell responses. Th2 cells were generated in vitro using CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 mice by incubation under Th2-skewing conditions for 6 days. cDCs and CD11b+Gr1int cells were isolated from the lungs of LPS-treated mice. cDCs and CD11b+Gr1int cells alone (each at 1 × 105 cells/well or at 5 fold more numbers of CD11b+Gr1int cells) or in combination as shown were cultured with Th2 polarized DO11.10 CD4+ T cells (1 × 106 cells/well) and OVA peptide (5 μg/ml). (a) Following cell-surface staining for CD4, intracellular cytokine staining for IL-5 was performed on co-cultured cells after 36 h. Cells were incubated with Golgi Stop (BD Biosciences) for the last 4 h of culture, were fixed with CytoFix/CytoPerm (BD Biosciences), permeabilized with Perm/Wash buffer (BD Biosciences) and labeled with anti-IL-5 mAb. For analysis by flow cytometry, gating on CD4-positive cells revealed a population with lower CD4 expression and blast-like FSC vs SSC properties (not shown), consistent with activated T cells. In each dot plot, the number represents the proportion of IL-5-producing cells (indicated by the box) among activated CD4-positive cells. (b) Cells were stimulated with IL-2 (50 U/ml) for 15 min and STAT5 phosphorylation determined by intracellular staining. (c) Nuclear extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against GATA-3 and β-actin. (d) Reversal of suppression of Th2 (IL-5 and IL-13) cytokine production by Arg 1 inhibitor and anti-IL-10. Culture supernatants were analyzed by multiplex cytokine assay. Data shown are mean ± s.d. * P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 with respect to cDC:CD11b+Gr1int (1:5 ratio).

Several mediators produced by MDSCs have been shown to mediate their suppressive functions which include NO, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and Arginase I (Arg 1) 13,36-38. Using RT-PCR techniques, both Arg1 and NOS2 expression was detected in the CD11b+Gr1int cells (data not shown). We therefore examined whether the suppressive effect of the lung-derived CD11b+Gr1int cells could be reversed by inhibiting some of these mediators produced by the cells. As shown in Figure 6d, addition of the Arg 1 inhibitor, nor-NOHA, or use of neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibody completely reversed Th2 cytokine suppression by the CD11b+Gr1int cells. However, addition of apocynin (inhibitor of NADPH oxidase), uric acid (peroxynitrite scavenger) or L-NIL (specific inhibitor of NOS2) to the co-culture did not reverse the suppressive effects of CD11b+Gr1int cells on cDC-induced IL-13 production from primed Th2 cells (Supplementary Figure 3). Thus, although L-NIL partially restored the ability of the Th2 cells to mount STAT5 activation and express GATA-3, it was not able to reverse suppression of cytokine production, which was only achieved by blocking Arg1 and IL-10.

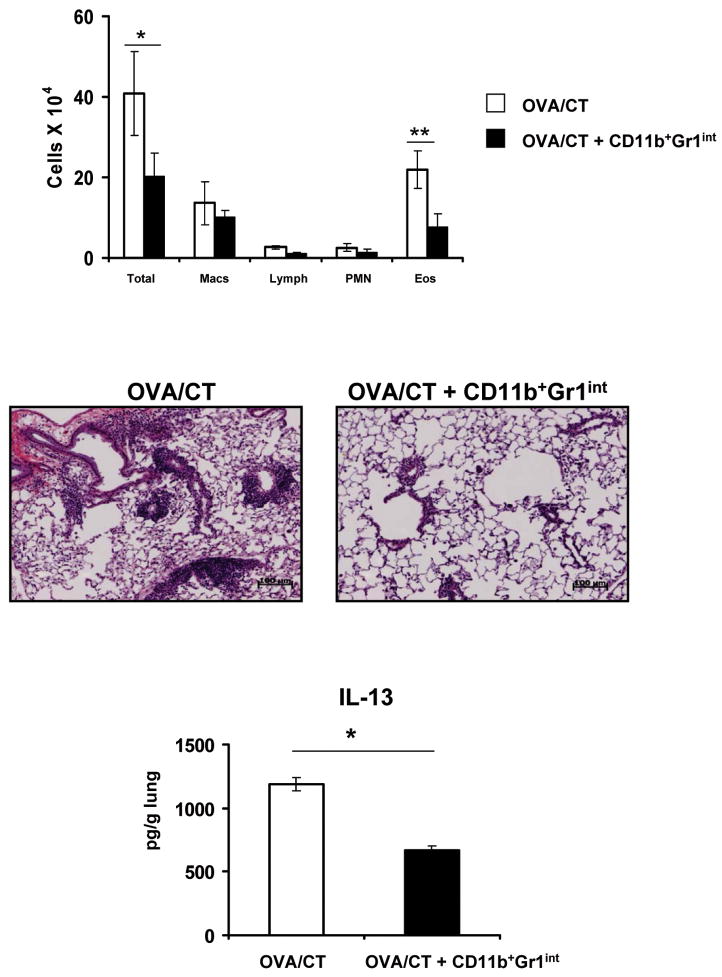

Adoptive transfer of in vitro- or in vivo-induced CD11b+Gr1int cells inhibit allergen-induced airway inflammation

Because all of our data showed the ability of the CD11b+Gr1int cells to inhibit the effector function of Th2 cells, we asked whether under post allergen-sensitized conditions that would mimic human disease, intratracheally transferred CD11b+Gr1int cells would have the ability to suppress recall responses to an allergen. We used OVA in combination with the mucosal adjuvant cholera toxin (CT) which we have shown previously shown induces allergic airway inflammation 39,40. In vitro-generated CD11b+Gr1+ cells (Figure 7) or LPS-induced cells isolated from the lung (Supplementary Figure 4) were transferred into mice sensitized with OVA plus CT. 24 h after the transfer of cells, mice were challenged over a span of 7 days with aerosolized 1% OVA. Control mice did not receive any cells. As shown in Fig. 7, and in Supplementary Fig. 4, transfer of CD11b+Gr1+ cells significantly reduced eosinophilic inflammation and IL-13 production in the lung suggesting the potential of these cells in therapeutic intervention of allergic airways disease.

Figure 7.

CD11b+Gr1int cell-mediated prevention and treatment of eosinophilic airway inflammation in vivo. Mice were antigen-sensitized by three daily consecutive intranasal treatments with OVA plus cholera toxin (CT) followed by 5 d of rest. CD11b+Gr1int cells were generated from bone-marrow progenitor cells in the presence of GM-CSF (10ng/ml) and LPS (1μg/ml) and then adoptively transferred intratracheally (1 × 106 cells/mouse) into mice that had received OVA/CT. Control mice did not receive any cells. Mice were then challenged with aerosolized OVA daily for 7 d. Total and differential cell counts in the BAL fluid (upper panel) were enumerated. Values are mean ± SEM *, P<0.05 and **, P<0.01. H&E staining (middle panel) of lung sections was performed. Lung infiltrates around bronchovascular bundles were of +5 grade in animals that did not receive CD11b+Gr1int cells and +1 grade in those that did. IL-13 present in lung homogenates (lower panel) was measured by ELISA and presented as the mean value ± SEM *, P < 0.05.

Discussion

In recent years, the notion that microbial products thwart the development of allergic disease by causing Th2 to Th1 immune deviation has not been supported by scientific evidence. For example, worm infections that induce Th2 responses were also found to be inversely associated with allergic disease which itself is a Th2-dominated disease 41. Given that immunosuppressive mechanisms are now thought to be more likely involved in mediating the protective effects of microbial products 42, we explored the possibility that LPS-induced TLR signaling promotes the development of suppressive cells in the lung since multiple studies have established an inverse relationship between the level of LPS exposure and the development of asthma and allergy 4,8,9.

LPS/TLR4 exerts a range of effects on allergic responses in the lung depending on the target cell and dose. Studies published recently show that TLR4 signaling in lung epithelial cells is important for HDM-induced allergic responses in the lung. Der p 2, an important allergen of HDM was able to substitute for the TLR4-associated adaptor, MD-2, that is not expressed by lung epithelial cells thereby providing this essential component of LPS-induced TLR4 signaling in these cells 22. Another study has also reported on the importance of TLR4 signaling in epithelial cells in HDM-induced allergic airways disease 23. With regard to the level of exposure, at very low levels below 10 ng, LPS induces suppression 43 while at levels ∼100 ng, LPS promotes Th2-mediated inflammation due to its adjuvant effects 8. A high dose of LPS is suppressive for allergic responses in the airways as shown in multiple studies 8,9, including the present study but the mechanism has not been investigated prior to this study.

We have identified a population of LPS-induced CD11b+Gr1int F4/80+ cells in the lung that does not traffic to lung-draining LNs. Indeed, no effect of LPS on T cell responses such as CD4 T cell proliferation or Th2 priming was evident in the lung-draining LNs. However, allergen-induced inflammation in the airways was dampened when the allergen was mixed with LPS and upon adoptive transfer, Th2-primed cells were unable to induce inflammation in LPS-exposed lungs. Together, these observations suggested suppressive effects of the cells localized to the lung tissue. When the effect of the CD11b+Gr1int cells on Th2-primed cells was examined in vitro, lung DC-induced GATA-3 upregulation and IL-2-induced STAT5 phosphorylation were both inhibited. The development of these cells was dependent on MyD88 but not TRIF. Lack of MyD88 unmasked the TRIF-dependent adjuvant effects of LPS even at a high LPS dose causing LPS to promote rather than suppress HDM-induced allergic inflammation. When adoptively transferred into mice, the myeloid cells efficiently inhibited allergen-induced airway inflammation.

The cell type identified by us bears close similarity to MDSCs. Although in addition to cancers, MDSCs have been identified in various other pathological conditions including acute and chronic infections such as worm infections13,37,44-46 and trauma 14, no prior study has explored the possibility that exposure of the lungs to a high dose of LPS might induce MDSC-like myeloid cells that would suppress reactivation of primed Th2 cells. In a previous study, HSPCs that had emigrated from the bone marrow were found to proliferate in extramedullary tissues such as the lung and respond to LPS resulting in differentiation into CD11c+ myeloid cells some of which coexpressed Gr17. While not examined in specific models, it was suggested that the myeloid cells might have immunosurveillance functions given that they arose in response to TLR agonists such as LPS. Our study shows that the LPS-induced lung-resident cells do have immunomodulatory functions and suppress Th2 effector function without promoting Th1 differentiation. In our experiments, linneg bone marrow progenitor cells stimulated with a combination of LPS and GM-CSF but not LPS alone yielded CD11b+Gr1int cells resembling the in vivo generated cells (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. 2). While LPS administration at a high dose alone was sufficient to promote the development of these cells in the lung, a prior study has implicated GM-CSF in the effects of LPS in the lung47. Thus, similar to the ability of GM-CSF to promote LPS-mediated development of these cells in vitro, GM-CSF most likely is also involved in the generation of these cells in vivo. Based on data shown in Figure 3 on the generation of GFP+ CD11b+Gr1int cells from linneg GFP+ cells introduced i.v. into animals, it is possible that HSPCs cells circulating through the lung 7 respond to LPS in situ to generate these cells.

Gr1+CD11b+ cells fall into two subsets in tumor models: cells with granulocytic phenotype that express Ly6G and cells with monocytic phenotype called inflammatory monocytes expressing Ly6C 48. The two populations with granulocytic versus monocytic characteristics might have different functions in infectious and autoimmune diseases and cancer. The majority of the LPS-induced myeloid cells in the lung expressed Ly6G, but not Ly6C and also did not express a range of other molecules expressed by MDSCs such as CD124 and CD115. To our knowledge, there are no reports that have shown the expression of Ly6G on either inflammatory monocytes or monocyte-derived DCs. In fact, Zhu et al. clearly showed that CD11b+ Ly6Chi suppressive monocytes are Ly6G negative15 further suggesting that the populations we have identified more closely resemble MDSCs. That being said, we feel that the functional distinction between inflammatory monocytes and MDSCs may blur over time since inflammatory monocytes have been shown to possess potent immunosuppressive functions 15,49,50.

Continual exposure to LPS causes a selective enrichment of the CD11b+Gr1int cells in the tissue over cDCs because these cells, unlike the cDCs, are unable to traffic to the LNs because of lack of CCR7 expression (Figure 3). The data in Figure 6 suggest that this enrichment is necessary since similar numbers of CD11b+Gr1int cells as cDCs are unable to inhibit either STAT5 phosphorylation, GATA-3 expression or cytokine production by primed Th2 cells but 5× more cells can. Thus, while increasing lung DC:T cell ratio induces more cytokine expression and transcription factor activation in the T cells, the opposite is true for the CD11b+Gr1int cells. Moreover, when mixed with cDCs, these cells suppress the ability of cDCs to reactivate primed Th2 cells (Figure 6). We have used the most conservative DC: CD11b+Gr1int ratio of 1:5 in our experiments with the numbers of these cells at the LPS dose used over a 4 day time period ranging between 5 and 10 fold over cDCs. Inhibition of Th2 cytokine production by the CD11b+Gr1int cells was reversed using neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibody or the specific Arg 1 inhibitor, nor-NOHA. Since IL-10 has been shown to induce Arg151,52, our data suggests that the IL-10-Arg1 axis is responsible for the suppressive effect of the myeloid cells on Th2 cytokine production. Interestingly, a similar suppressive effect of Arg1 on Th2 effector function was recently reported in mice infected with the helminth Schistosoma mansoni 53. Mice lacking Arg1 in macrophages harbored increased levels of Th2 cytokines in the liver of infected mice which was not simply due to increased frequency of the cells 53. The suppressive effect of Arg1 activity on Th2 effector function is interesting given that Th2 cytokines actually stimulate Arg1 expression 54,55. Thus, it is possible that while Th2 cytokine promotes Arg1 expression, Arg1-stimulated metabolites such as polyamines may function as negative feedback regulators of Th2 effector function. We would propose that the IL-10-Arg1-mediated inhibition is a dominant mechanism that overrides the activity of key regulators of Th2 cells such as GATA-3 and STAT5. This is because Th2 cytokine production was suppressed by the CD11b+Gr1int cells despite the ability of the Th2 cells to mount a low level of STAT5 phosphorylation and the presence of a low level of GATA-3 in the cells. In fact, as previously shown by Paul and colleagues, the low level of GATA-3 that is normally present in naïve CD4+ T cells is sufficient to synergize with constitutively active STAT5 to induce Th2 cytokine production 30,56. Given that a self-amplification loop stimulated by various cytokines is thought to sustain Th2 effector cells 56, it is possible that the blunting of this response by attenuation of GATA-3 and STAT5 activation and suppression of cytokine production would also negatively impact Th2 memory. This is based on the linear model of Th2 memory in which the memory pool size is directly proportional to the effector pool size 57. Thus, it will be interesting to determine in future studies the effect of these cells on effector cell survival in vivo.

CD11b+Gr1+ cells were also identified in a model of sepsis but the cells described in this study do not appear to be the kind we have identified in the lung since the splenic cells in the sepsis model actually promoted Th2 polarization 46. While the sepsis model would have involved stimulation by microbial products, and indeed the generation of the CD11b+Gr1+ cells was shown to be dependent on MyD88-dependent signaling, the requirement for functional TLR4 was not evident in the study 46. In contrast, TLR4 was required for development of the cell in our study (Figure 5). Similar to our findings, the TRIF pathway was not involved in the generation of the splenic CD11b+Gr1+ cells. Since despite producing high levels of IL-10, the sepsis-associated CD11b+Gr1+ cells favored Th2 development that was detrimental in the sepsis context46, it is possible that unlike the lung cells, the splenic cells do not express Arg 1.

In a recent study, prenatal exposure to a non-pathogenic bacterial species was found to protect from allergic airways disease later in the adult mice, the protective effect being dependent on multiple TLRs 58. Whether such exposures prenatally generated the kind of suppressive cell identified by us remains to be determined. Also, whether these cells play a role in the development of Tregs will be important to examine given that CTLA-4, a ligand of CD80, is expressed at high levels by Tregs and is important for Treg functions 59.

In summary, our study has identified the ability of LPS to induce Th2-suppressive myeloid cells in the lung that phenotypically and functionally resemble MDSCs. In the context of allergic airways disease, these cells may have beneficial effects in inhibiting disease pathogenesis, which contrasts with the negative connotation that MDSCs have in most disease contexts. Thus, the CD11b+Gr1int cells may be the underlying principle of the hygiene hypothesis in the context of protection from allergic asthma. A complete understanding of the generation and regulation of these cells in the lung in response to various pathogens would provide new avenues to either promote or target these cells for therapeutic benefits to develop disease-specific immunoregulation.

Methods

Animals and Reagents

Male 6-8 week old BALB/c ByJ mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. DO11.10 transgenic mice were originally provided by Dr. Kenneth Murphy at Washington University, St. Louis and were bred at the animal facility at the University of Pittsburgh. The generation of MyD88-/- mice was previously described 60. TRIF-/- mice were a gift of Dr. Bruce Beutler at the Scripps Research Institute. All studies with mice were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pittsburgh. Recombinant GM-CSF was purchased from PeproTech. LPS from Escherichia coli, strain O26:B6, was obtained from Sigma. House Dust Mite (HDM; Dermatophagoides Pteronyssinus) was purchased from Greer Laboratories and was stripped of LPS using Endo-Trap columns. A number of directly labeled monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were used in cell phenotyping experiments as follows: PE-labeled anti-mouse CD40 (clone:3/23), PE-labeled anti-mouse CD86 (clone:GL1), APC-labeled anti-mouse CD11c (clone:HL3), APC-labeled anti-mouse Gr1 (clone: RB6-8C5), FITC-labeled anti-mouse Ly6C (clone: AL-21), PE-labeled anti-mouse Ly6G (clone: 1A8), and neutralizing anti-mouse IL-6 were all purchased from BD Biosciences. PE-labeled rat anti-mouse CD80 was purchased from Serotec. PE-labeled anti-mouse MHC II (clone: NIMR-4) was purchased from Southern Biotech. PE- and APC-labeled anti-mouse F4/80, streptavidin–tricolor was purchased from Caltag Laboratories. L-(1-iminoethyl)lysine) (L-NIL; NOS2-specific inhibitor) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Induction of allergic airway inflammation by HDM

Balb/c mice were exposed to HDM (100 μg/mouse/treatment) intratracheally on days 0, 7, 14 and 21 with or without concomitant treatment with LPS (10μg/mouse/treatment). Lung-draining LNs were harvested 7 days after one HDM instillation ± LPS to assess CD4+ T cell priming. IL-5 ELISPOT assay was then performed with kit from eBioscience as per the manufacturer's specifications. Briefly, ELISPOT plates (Millipore 96-well MultiScreen HTS) were coated with the capture antibody at 4°C overnight. Lymph node cells were plated and stimulated with PMA (25 ng/ml) and ionomycin (500 ng/ml) overnight. Biotin-conjugated detection antibody was used to detect the secreted cytokine. Plates were developed with Avidin–horseradish peroxidase and peroxidase substrate (Vectastatin) and quantified with an automated ELISPOT plate reader (ImmunoSpot; Cellular Technology). The number of cytokine-expressing CD4+ T cells from lymph node was estimated by calculation using the percentage of CD4 T cells determined by flow cytometry.

72 h after the final HDM exposure, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and lung tissue were obtained. Lung inflammation was gauged based upon BAL fluid differential cell counts and H&E and Periodic acid Schiff staining performed on lung tissue sections. A semiquantitative method was used to score lung infiltrates. A >3 cell-deep infiltrate around bronchovascular bundles was a +5 grade infiltrate and +1 or lower signified a low degree of inflammation. Production of cytokines was assessed by preparation of whole lung homogenates and analysis by multiplex assay (Bioplex; Bio-Rad).

Generation of LPS-induced cells in vivo

LPS (up to 10μg/mouse/dose) was instilled intratracheally in 100 μl into Balb/c mice daily for four consecutive days. 24 h after the final exposure, mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg)/xylazine (10 mg/kg) mixture. After exsanguination via cardiac puncture, the aorta was severed and the pulmonary vasculature was perfused with sterile PBS plus heparin (500 U/ml) to remove peripheral blood cells. The perfused lungs were removed, finely minced, and incubated in an enzyme solution containing 0.7 mg/ml collagenase A (Boehringer Mannheim) and 30 μg/ml type IV bovine pancreatic DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) for 60 min at 37°C. Digested lung tissue was pressed through a 70 μm cell strainer and the filtered cells were further enriched by positive selection using magnetic bead separation with anti-CD11b microbeads and an AutoMACs automated cell separation instrument (Miltenyi Biotec). CD11b+ cells were then stained with APC-labeled anti-Gr1 and PE-labeled anti-F4/80 antibodies (BD Biosciences). Cells expressing F4/80 and an intermediate level of Gr1 (Gr1intF4/80+), and cells expressing a high level of Gr1 but no F4/80 (Gr1hi, polymorphonuclear (PMNs); neutrophils) were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting using a BD Biosciences FACSAria flow cytometer running FACSDiva software.

Conventional DCs (cDCs) were isolated from mouse lungs. Single cell lung suspensions were prepared as above except that magnetic bead selection was performed using anti-CD11c microbeads. Then CD11c+ cells, with low autofluorescence detected by the E PMT of the FACSAria cytometer, were sorted from highly autofluorescent cells (largely CD11c+ alveolar macrophages) and were used as conventional DCs.

Cytokine production from CD11b+Gr1int cells and DCs was assessed by culturing the cells overnight at 37°C then examining culture supernatants by multiplex cytokine assay (Bio-Rad).

Generation of dendritic cells and CD11b+Gr1+ cells from bone marrow cells in vitro

Femurs of mice were aseptically removed and cleaned of surrounding muscle tissue. Bone marrow cells flushed from the femurs using PBS were grown in RPMI medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gemini), 100 U/ml of penicillin and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin sulfate (Gibco), 1mM sodium-pyruvate (Gibco) and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma). The cultures were supplemented with 10 ng/ml of granulocyte- macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in the absence or presence of LPS (Escherichia coli, strain O26:B6) and were incubated for 8-9 days at 37°C. At the end of the culture period, non-adherent cells were collected and purified by magnetic bead positive selection (Miltenyi Biotec) for CD11c-expressing cells in the case of cultures with GM-CSF alone, or for Thy1.2-expressing cells with LPS+GM-CSF-treated cultures. Similar cultures were also started from lineageneg cells enriched using a lineage depletion kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Cell purity, assessed by flow cytometry, was greater than 95% in both the cases. CD11c+ cells, considered to be conventional bone marrow DCs (BMDCs).

Development of CD11b+Gr1int cells in the lung from lineageneg progenitor cells from UBC-GFP transgenic mice in the presence of LPS

The linneg population of bone marrow cells was enriched from Transgenic (UBC-GFP) mice (Jackson Laboratories, stock#004353). These transgenic mice express enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (EGFP) under the direction of the human ubiquitin C promoter. GFP expression is uniform within a cell type lineage and remains constant throughout development. This GFP+linneg population was then transferred intravenously (i.v.) into naive C57BL/6 mice. Mice were divided into two groups and one group then received three daily treatments of 10 μg LPS while the other group was left untreated. The percentage of cells expressing intermediate (int) levels of Gr1 was determined in the presence or absence of LPS by flow cytometric analysis.

Phenotypic evaluation of CD11b+Gr1int cells and cDCs

The surface phenotype of cells was assessed by flow cytometry using standard methods. Briefly, cells were first incubated with unlabeled CD16/CD32 mAb (Fc block) for 5 min on ice, then with specifically conjugated mAbs for an additional 15 min. In all cases, control staining with appropriate, matched isotype control antibodies was similarly performed. All incubations were conducted at 4°C in PBS supplemented with 2% FBS. Analysis was carried out on a BD Biosciences FACSCalibur flow cytometer using CellQuest Pro software. Propidium iodide, used to exclude dead cells, was added just prior to data collection, and at least 10,000 events within the live cell gate were acquired for each sample.

Colorimetric Assay for Nitric Oxide

Nitric oxide production by DCs and CD11b+Gr1int cells was measured using a commercially-available colorimetric assay (Oxford Biomedical Research) as per the manufacturer's instructions. This kit employs the NADH-dependent enzyme nitrate reductase for conversion of nitrate to nitrite prior to quantitation using Griess reagent, thus providing for accurate determination of total NO production.

Proliferation of adoptively transferred CD4+ T Cells

CD4+ T cells isolated from spleen cells of DO11.10 mice using anti-CD4 magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), were labeled with CFSE (Molecular Probes), and 5 × 106 labeled cells were adoptively transferred i.v. to naïve mice or LPS-treated (four consecutive daily intratracheal injections of 10 ug/treatment LPS) mice. Twenty four hrs after the adoptive transfer, mice received two consecutive daily intranasal treatments with OVA plus cholera toxin (CT; 1 μg/mouse/treatment). One day later, total lung-draining lymph node cells were harvested and assessed for dilution of CFSE by flow cytometry. OVA-specific DO11.10 T cells were identified by staining with anti-clonotypic KJ-126 antibody (BD Pharmingen).

Generation and adoptive transfer of Th2 cells prior to antigen challenge

To generate Th2 cells, CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 TCR Tg mice were cultured with APCs (T cell-depleted splenocytes), OVA-peptide (5μg/ml), IL-4 (20ng/ml), IL-2 (5U/ml) and anti-IFN-γ (1μg/ml) as described previously 19. Cultures were maintained for 5 days and re-stimulated again for 3 days under the same TH2 conditions. The Th2-skewed nature of these cells was verified based upon production of Th2 cytokines, and expression of the TH2-specific nuclear transcription factor GATA-3 (data not shown). TH2 cells were collected, washed with PBS, and injected intravenously into naïve and LPS treated mice (5 × 106 cells/mouse). Beginning one day after cell transfer, mice were challenged with aerosolized OVA (1% in PBS) for 20 min daily for 7 days using an ultrasonic nebulizer (Omron Healthcare). Twenty four hrs after the final OVA challenge, BAL fluid and lung tissue were obtained and processed as described above.

Effect of adoptively transferred CD11b+Gr1int cells on allergic airway inflammation

Mice were sensitized by intranasal administration of OVA/CT for 3 consecutive days and then were rested for 5 days. After the rest period, 1 × 106 in vitro or in vivo-generated CD11b+Gr1int (see above) cells were adoptively transferred intratracheally into each mouse. Beginning one day after transfer, mice were challenged by exposure to aerosolized OVA for 7 consecutive days. Twenty four hrs after the final OVA challenge, BAL fluid and lung tissue were obtained and processed as described above.

Statistical analyses

Comparisons of means ± SD or ± SEM were performed using one way analysis of variance and Student t- test with GraphPad Prism software. Differences between the groups were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants HL 060207 and HL 069810 (to P.R.), HL 077430 and AI 048927 (to A.R.), HL 084932 (to P.R. and A.R.), and grants from the American Heart Association, AHA 0865379D (to M.A.) and American Lung Association, RG-49737-N (to T.B.O.). The authors thank S. Akira for the kind gift of MyD88-/- mice, Y. Zhang and M. Porter for assistance with multiplex assay and A. Khare for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict.

References

- 1.Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. Bmj. 1989;299:1259–1260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shirakawa T, Enomoto T, Shimazu S, Hopkin JM. The inverse association between tuberculin responses and atopic disorder. Science. 1997;275:77–79. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball TM, et al. Siblings, day-care attendance, and the risk of asthma and wheezing during childhood. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:538–543. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008243430803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun-Fahrlander C, et al. Environmental exposure to endotoxin and its relation to asthma in school-age children. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:869–877. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yabuhara A, et al. TH2-polarized immunological memory to inhalant allergens in atopics is established during infancy and early childhood. Clin Exp Allergy. 1997;27:1261–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson DL, Gange SJ, Rose NR, Graham NM. Epidemiology and estimated population burden of selected autoimmune diseases in the United States. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;84:223–243. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massberg S, et al. Immunosurveillance by hematopoietic progenitor cells trafficking through blood, lymph, and peripheral tissues. Cell. 2007;131:994–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenbarth SC, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-enhanced, toll-like receptor 4-dependent T helper cell type 2 responses to inhaled antigen. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1645–1651. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez D, et al. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide signaling through Toll-like receptor 4 suppresses asthma-like responses via nitric oxide synthase 2 activity. J Immunol. 2003;171:1001–1008. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bliss SK, Butcher BA, Denkers EY. Rapid recruitment of neutrophils containing prestored IL-12 during microbial infection. J Immunol. 2000;165:4515–4521. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.8.4515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hidalgo A, et al. Heterotypic interactions enabled by polarized neutrophil microdomains mediate thromboinflammatory injury. Nat Med. 2009;15:384–391. doi: 10.1038/nm.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Collazo M, Gabrilovich DI. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:5791–5802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makarenkova VP, Bansal V, Matta BM, Perez LA, Ochoa JB. CD11b+/Gr-1+ myeloid suppressor cells cause T cell dysfunction after traumatic stress. J Immunol. 2006;176:2085–2094. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu B, et al. CD11b+Ly-6C(hi) suppressive monocytes in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2007;179:5228–5237. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang R, et al. CD80 in immune suppression by mouse ovarian carcinoma-associated Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6807–6815. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohl J, et al. A regulatory role for the C5a anaphylatoxin in type 2 immunity in asthma. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:783–796. doi: 10.1172/JCI26582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackay CR, Marston WL, Dudler L. Naive and memory T cells show distinct pathways of lymphocyte recirculation. J Exp Med. 1990;171:801–817. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.3.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohn L, Homer RJ, Marinov A, Rankin J, Bottomly K. Induction of airway mucus production By T helper 2 (Th2) cells: a critical role for interleukin 4 in cell recruitment but not mucus production. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1737–1747. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Das J, et al. A critical role for NF-kappa B in GATA3 expression and TH2 differentiation in allergic airway inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:45–50. doi: 10.1038/83158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishii KJ, et al. CpG-activated Thy1.2+ dendritic cells protect against lethal Listeria monocytogenes infection. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2397–2405. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trompette A, et al. Allergenicity resulting from functional mimicry of a Toll-like receptor complex protein. Nature. 2009;457:585–588. doi: 10.1038/nature07548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammad H, et al. House dust mite allergen induces asthma via Toll-like receptor 4 triggering of airway structural cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:410–416. doi: 10.1038/nm.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoebe K, et al. Upregulation of costimulatory molecules induced by lipopolysaccharide and double-stranded RNA occurs by Trif-dependent and Trif-independent pathways. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1223–1229. doi: 10.1038/ni1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang DH, Cohn L, Ray P, Bottomly K, Ray A. Transcription factor GATA-3 is differentially expressed in Th1 and Th2 cells and controls Th2-specific expression of the interleukin-5 gene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21597–21603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang DH, et al. Inhibition of allergic inflammation in a murine model of asthma by expression of a dominant-negative mutant of GATA-3. Immunity. 1999;11:473–482. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng Wp, Flavell RA. The transcription factor GATA-3 is necessary and sufficient for Th2 cytokine gene expression in CD4 T cells. Cell. 1997;89:587–596. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee HJ, O'Garra A, Arai KI, Arai N. Characterization of cis-regulatory elements and nuclear factors conferring Th2-specific expression of the IL-5 gene: a role for a GATA-binding protein. J Immunol. 1998;160:2343–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Das J, et al. A critical role for NF-kB in Gata3 expression and Th2 differentiation in allergic airway inflammation. Nature Immunol. 2001;2:45–50. doi: 10.1038/83158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu J, Cote-Sierra J, Guo L, Paul WE. Stat5 activation plays a critical role in Th2 differentiation. Immunity. 2003;19:739–748. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo L, et al. IL-1 family members and STAT activators induce cytokine production by Th2, Th17, and Th1 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13463–13468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906988106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weyand CM, Goronzy J, Fathman CG. Modulation of CD4 by antigenic activation. J Immunol. 1987;138:1351–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Acres RB, Conlon PJ, Mochizuki DY, Gallis B. Rapid phosphorylation and modulation of the T4 antigen on cloned helper T cells induced by phorbol myristate acetate or antigen. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:16210–16214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bingisser RM, Tilbrook PA, Holt PG, Kees UR. Macrophage-derived nitric oxide regulates T cell activation via reversible disruption of the Jak3/STAT5 signaling pathway. J Immunol. 1998;160:5729–5734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazzoni A, et al. Myeloid suppressor lines inhibit T cell responses by an NO-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2002;168:689–695. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bronte V, et al. IL-4-induced arginase 1 suppresses alloreactive T cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 2003;170:270–278. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez PC, Ochoa AC. Arginine regulation by myeloid derived suppressor cells and tolerance in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:180–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagaraj S, et al. Altered recognition of antigen is a mechanism of CD8+ T cell tolerance in cancer. Nat Med. 2007;13:828–835. doi: 10.1038/nm1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krishnamoorthy N, et al. Activation of c-Kit in dendritic cells regulates T helper cell differentiation and allergic asthma. Nat Med. 2008;14:565–573. doi: 10.1038/nm1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oriss TB, et al. Dynamics of dendritic cell phenotype and interactions with CD4+ T cells in airway inflammation and tolerance. J Immunol. 2005;174:854–863. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yazdanbakhsh M, Kremsner PG, van Ree R. Allergy, parasites, and the hygiene hypothesis. Science. 2002;296:490–494. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5567.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wills-Karp M, Santeliz J, Karp CL. The germless theory of allergic disease: revisiting the hygiene hypothesis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:69–75. doi: 10.1038/35095579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bedoret D, et al. Lung interstitial macrophages alter dendritic cell functions to prevent airway allergy in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3723–3738. doi: 10.1172/JCI39717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Terrazas LI, Walsh KL, Piskorska D, McGuire E, Harn DA., Jr The schistosome oligosaccharide lacto-N-neotetraose expands Gr1(+) cells that secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines and inhibit proliferation of naive CD4(+) cells: a potential mechanism for immune polarization in helminth infections. J Immunol. 2001;167:5294–5303. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sica A, Bronte V. Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1155–1166. doi: 10.1172/JCI31422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Delano MJ, et al. MyD88-dependent expansion of an immature GR-1(+)CD11b(+) population induces T cell suppression and Th2 polarization in sepsis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1463–1474. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bozinovski S, et al. Innate immune responses to LPS in mouse lung are suppressed and reversed by neutralization of GM-CSF via repression of TLR-4. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L877–885. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00275.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Movahedi K, et al. Identification of discrete tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations with distinct T cell-suppressive activity. Blood. 2008;111:4233–4244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gallina G, et al. Tumors induce a subset of inflammatory monocytes with immunosuppressive activity on CD8+ T cells. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2777–2790. doi: 10.1172/JCI28828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dunay IR, et al. Gr1(+) inflammatory monocytes are required for mucosal resistance to the pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. Immunity. 2008;29:306–317. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Corraliza IM, Soler G, Eichmann K, Modolell M. Arginase induction by suppressors of nitric oxide synthesis (IL-4, IL-10 and PGE2) in murine bone-marrow-derived macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;206:667–673. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lang R, Patel D, Morris JJ, Rutschman RL, Murray PJ. Shaping gene expression in activated and resting primary macrophages by IL-10. J Immunol. 2002;169:2253–2263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pesce JT, et al. Arginase-1-expressing macrophages suppress Th2 cytokine-driven inflammation and fibrosis. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000371. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Modolell M, Corraliza IM, Link F, Soler G, Eichmann K. Reciprocal regulation of the nitric oxide synthase/arginase balance in mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages by TH1 and TH2 cytokines. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1101–1104. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Munder M, et al. Th1/Th2-regulated expression of arginase isoforms in murine macrophages and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:3771–3777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paul WE, Zhu J. How are T(H)2-type immune responses initiated and amplified? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:225–235. doi: 10.1038/nri2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu H, et al. CD4(+) T cell effectors can become memory cells with high efficiency and without further division. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:705–710. doi: 10.1038/90643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Conrad ML, et al. Maternal TLR signaling is required for prenatal asthma protection by the nonpathogenic microbe Acinetobacter lwoffii F78. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2869–2877. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wing K, et al. CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science. 2008;322:271–275. doi: 10.1126/science.1160062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adachi O, et al. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity. 1998;9:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.