Abstract

In fission yeast, the Sty1/Spc1/Phh1 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is known to be involved in multiple-stress responses. It is currently thought that the Sty1 MAPK cascade is mediated by histidine kinases and phosphorelay proteins in response to oxidative stress signals. However, studies of the exact transduction mechanism of multiple-stress responses are lacking. Thus, in response to various stimuli, we monitored the Sty1 MAPK pathway through the downstream transcription factor Atf1 in living cells using a highly sensitive luciferase reporter gene. Surprisingly, in cadmium and low glucose (LG) medium, Atf1 activation was observed even in the absence of all of the four fission yeast MAPK kinase kinases (MAPKKKs); whereas in osmotic stress, Atf1 activation was abolished. Thus, the osmotic stress likely mediates the MAPK activation via MAPKKKs, whereas a cadmium or LG condition activates the MAPK in a MAPKKK-independent manner. On the other hand, knockout of tyrosine phosphatase gene pyp1+ abolished the Atf1 response to cadmium and LG, but not to osmotic stress, suggesting that Pyp1 is a sensor for cadmium and LG.

Keywords: Cell Cycle, Cellular Regulation, Glucose, MAP Kinases (MAPKs), p38 MAPK, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), Transcription Regulation, Protein-tyrosine Phosphatase (Tyrosine Phosphatase)

Introduction

The MAPK signaling pathways are critical for the response of eukaryotic cells to adapt to external environment conditions (1). A MAPK module is a three-kinase cascade, consisting of three protein kinases: a MAPKKK2 that activates a MAPK kinase (MAPKK), which in turn activates a MAPK enzyme. In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the Sty1 MAPK pathway is known to be involved in multiple-stress responses such as high temperature, osmotic stress, oxidative stress, nutrient limitation, and heavy metal toxicity (2–5). In general, signals induced by these multiple stress agents are relayed from the membrane or the cytoplasm to the nucleus to regulate gene expression for stress adaptation.

To date, histidine-to-aspartate (His-to-Asp) phosphorelay signaling systems are thought to be involved in the signal transduction implicated in oxidative stress response: activated histidine kinases Mak1, Mak2, and Mak3 (6) mediate their effects through phosphorelay protein Mpr1/Spy1 and Mcs4 response regulator (6–8). Mcs4 then in turn regulates MAPK module by activating the MAPKKKs Wis4/Wak1/Wik1 and Win1 (3, 9), which are functionally redundant in activating MAPKK Wis1. Wis1 is required for activation of the MAPK Sty1 following osmotic, heat, or oxidative stresses (10, 11). Besides, Pyp1 phosphotyrosine-specific phosphatase that dephosphorylates and inactivates the MAPK (2, 3, 12, 13) was also reported to regulate Sty1 activation upon heat shock (14). Activated Sty1 accumulates in the nucleus (15, 16), where it activates transcription factors, such as bZIP transcription factor Atf1, and regulates a large set of genes that are relevant to the stress adaptation (see Fig. 4A).

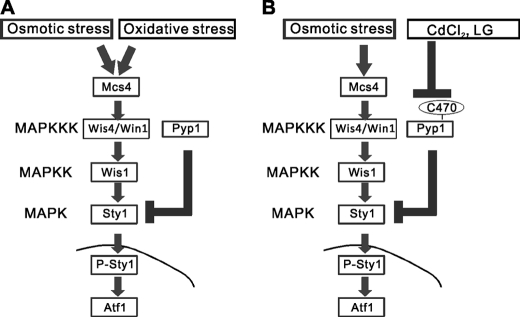

FIGURE 4.

A, previous hypothesis proposing that all of the stresses are mediated by the two MAPKKKs (38). B, our hypothesis: MAPKKK-dependent and -independent activation of Sty1 MAPK in fission yeast.

In an attempt to identify the mechanisms of signal transduction and the sensing systems of each distinct stress factor in fission yeast, we monitored the transcriptional activity of Atf1 in living cells using a destabilized luciferase reporter gene fused to three tandem repeats of cAMP response elements (CRE)-like sequence under the conditions of osmotic stress KCl, heavy metal CdCl2, and low-glucose (LG) medium. We have investigated the knock-out strains known to be involved in the Sty1 MAPK pathway to see if there are defects in signal transduction accompanying the gene knockout. Here, we show evidence for the presence of MAPKKK-dependent and -independent activation of the MAPK. We also show that Pyp1 plays a role for sensing heavy metal CdCl2 and LG.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains, Media, and Genetic and Molecular Biology Methods

S. pombe strains used in this study are listed in supplemental Table S1. The media, notation, and genetic methods have been described previously (17, 18).

Construction of Reporter Plasmid

A multicopy plasmid (pKB5760) containing the nmt1 promoter without its cis element, three tandem repeats of CRE-like sequence (TGACGTAG or CTACGTCA) which is the binding core of the Atf1-Pcr1 heterodimeric transcriptional activator identified in the fbp1 promoter (19), and the destabilized luciferase from pGL3(R2.2) version containing PEST, CL1, and AU-rich repeats was constructed as described previously (20) except that the CDRE oligonucleotides were replaced by the CRE-like oligonucleotides (sense, 5′-GGC TTT GAC GTA GAT ACA TGA CGT AGA TAC ACA TGA CGT AGA TGC AC-3′; antisense, 5′-TCG AGT GCA TCT ACG TCA TGT GTA TCT ACG TCA TGT ATC TAC GTC AAA GCC TGC A-3′, CRE-like sequence underlined). Similarly, an integration vector used to stably integrate 3×CRE::luc(R2.2) constructs into the arg1+ locus was constructed by inserting the CRE-like oligonucleotides and arg1+ into pBC SK(+) (Stratagene) to give pKB5810 (21). These two reporter vectors were used for live-cell monitoring of Atf1-mediated transcriptional activity in living cells.

Real-time Monitoring Assay of Atf1-mediated Transcriptional Activity

The above constructed multicopy reporter plasmid was transformed into fission yeast cells for reporter assays, and an integration reporter plasmid was used to construct stable integration strains as described previously (20). For the experiments with the stress agents, cells as indicated were transformed with the reporter plasmid and were either untreated (water as control) or treated with KCl, CdCl2, and LG, respectively. For the experiments with LG, cells were cultured at 27 °C in EMM containing 2% glucose overnight to mid-log phase and then recovered by filtration and resuspended in EMM containing 0.1% glucose. The assay is based on the interaction of luciferase with substrate luciferin, and yielding luminescence was detected using a luminometer (AB-2300; ATTO Co., Tokyo, Japan) at 1-min intervals and reported as relative light units.

Immunoblot Analyses

An integration vector containing Sty1–2×HA-His6 construct (5) was generously provided by J. Kanoh and was used for transformation of various strains. Immunoblot analyses were performed as described previously (22) using anti-phosphorylated p38 (Thr180/Tyr182) MAPK antibody (Cell Signaling) and anti-HA antibody (Roche). Antibody to fission yeast Cdc4 protein was prepared by immunizing the rabbit with purified Cdc4 protein and was used for the detection of endogenous Cdc4 as a loading control.

Construction of Inducible Expression Plasmid of Sty1 MAPK

For inducible ectopic expression of proteins, we used the thiamine-repressible nmt1 promoter (23). The open reading frame (ORF) of sty1+ was amplified by PCR primers (sense, 5′-CGG GAT CCC ATG GCA GAA TTT ATT CGT AC-3′; antisense, 5′-CGG AAT TCG CGG CCG CGG GAT TGC AGT TCA TTA TCC-3′) and subcloned into the BglII/NotI site of pSLF372L (24) to express 3×HA-tagged Sty1 MAPK. The above constructed inducible plasmid was transformed into cells harboring the integrated 3×CRE::luc(R2.2) reporter. Expression was repressed by the addition of 4 μm thiamine to EMM as described previously (23).

Disruption of byr2+ and mkh1+ Genes

The byr2+ gene was disrupted via the plasmid-based approach (21): a 1446-bp fragment (563–1908 base) was amplified by PCR using the following primers: 5′-CGG GAT CCC GAG CAC TCA GAA ACG AAG TGT C-3′ and 5′-CGG GAT CCC TCA AGG AAA TCT ATG GCC GAT G-3′ and subcloned into the BamHI site of pGEM-7Zf(−) (Promega) to give pKB7953. Gene disruption constructs were prepared by inserting lys3+ flanked by EcoRV site into the HincII/EcoRV site of the ORF of the byr2+ gene that was subcloned into pKB7955 and transformed into lys3+-deleted cells to disrupt the byr2+ gene by homologous recombination. The mkh1+ gene was similarly disrupted (24): a 3323-bp fragment (9–3331 base) was amplified by PCR using the following primers: 5′-AAA ACT GCA GCG ATA TCG GAT CGC AGT CAT CAG-3′ and 5′-AAA ACT GCA GGC ATG TCG TAA AGA TTC GTG TCC-3′ and subcloned into the PstI site of pGEM-5Zf(+) (Promega) to give pKB7954. Gene disruption constructs were prepared by inserting asn1+ flanked by the BamHI site into the BamHI site of the ORF of the mkh1+ gene that was subcloned into pKB7956 and transformed into asn1+-deleted cells to disrupt the mkh1+ gene. Disruptions of the byr2+ and mkh1+ gene were confirmed by PCR.

Construction of Δpyp1 Cells Containing Integrated pREP1-pyp1C470S-GFP

A mutant of wild-type pyp1+ containing Ser instead of Cys at amino acid 470 (pyp1C470S) was generated using a QuikChange® Site-directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing, and the fragment was subcloned into the C-terminal GFP fusion pREP1 vector. The pREP1-pyp1C470S-GFP was linearized and transformed into Δpyp1 cells. Integration of pREP1-pyp1C470S-GFP was confirmed by Southern hybridization.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

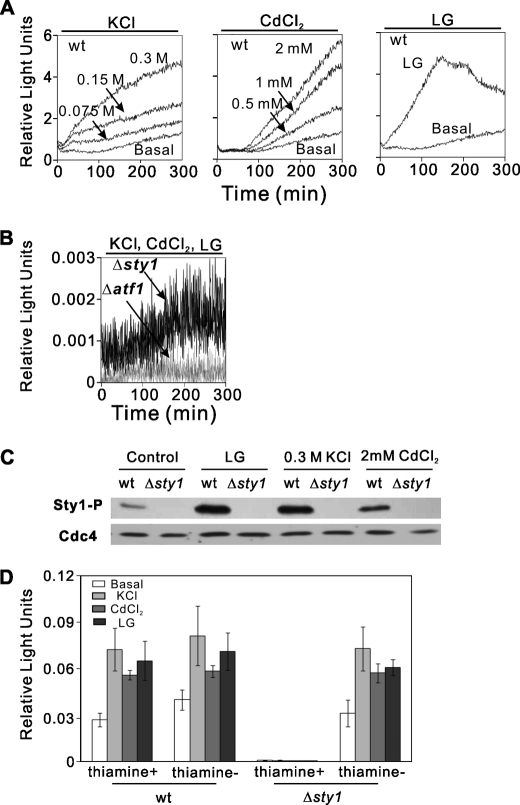

Wild-type cells, Δatf1 cells, and Δsty1 cells were subjected to osmotic stress (0.075–0.3 m KCl), heavy metal stress (0.5–2 mm CdCl2), and LG (0.1% glucose), respectively. In wild-type cells, elevated extracellular KCl caused a continuous rise in a dose-dependent manner in the Atf1 transcriptional activity (Fig. 1A, left panel). CdCl2 also caused a dose-dependent increase (Fig. 1A, center panel); however, it should be noted that there was a delayed onset of increasing response compared with that by KCl. LG showed a steady increase in response, with a peak rise at about 120 min (Fig. 1A, right panel). In Δatf1 cells, there was no response upon treatment with KCl, CdCl2, or LG (Fig. 1B), indicating that the 3×CRE::luc(R2.2) reporter assay reflects the Atf1 activity. In Δsty1 cells, the 3×CRE::luc(R2.2) reporter activity was hardly detected (Fig. 1B), indicating that the reporter assay also reflects the Sty1 activity.

FIGURE 1.

Real-time monitoring of Atf1 activity in living cells. A, live-cell monitoring of Atf1 activity in wild-type cells. Wild-type cells transformed with the multicopy plasmid (3×CRE::luc(R2.2) reporter plasmid) were incubated with d-luciferin and treated with KCl (0.075–0.3 m), CdCl2 (0.5–2 mm), or EMM with LG (0.1% glucose). Relative light units are expressed as the ratio of light emission of each sample to the basal (without stimulation) light emission of wild-type cells in EMM at 180 min. The data shown are representative of multiple experiments. B, reporter assay reflecting Sty1 activity as well as Atf1 activity in living cells. The cells as indicated were transformed with the reporter plasmid, cultured in EMM at 27 °C, and treated with KCl (0.3 m), CdCl2 (2 mm), or LG (0.1% glucose), as described under “Experimental Procedures.” C, detection of phosphorylated Sty1 by immunoblotting. Cells were grown in YPD medium at 27 °C and exposed to LG medium, 0.3 m KCl, or 2 mm CdCl2 for 30 min. Phosphorylated Sty1 protein (Sty1-P) was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-phosphorylated p38 (Thr180/Tyr182) MAPK antibody and anti-Cdc4 antibody as described under “Experimental Procedures.” D, real-time monitoring of integration reporter activities in wild-type and Δsty1 cells. Δsty1 cells harboring the stable integration reporter vector transformed with an inducible-expression plasmid of Sty1 in the presence or absence of thiamine (see “Experimental Procedures”) were treated as indicated. Error bars, mean ± S.D.

As a further test, we examined the level of dual phosphorylation on threonine and tyrosine of Sty1 by immunoblotting under the treatment with KCl, CdCl2, or LG (Fig. 1C). The immunoblot detected a substantial increase in the phosphorylation level caused by each stress factor, which is consistent with the results of 3×CRE::luc(R2.2) reporter assay.

Also, the integrated 3×CRE::luc(R2.2) reporter activities were examined in Δsty1 cells that were transformed with an inducible Sty1 on an expression plasmid. When the Sty1 expression was repressed by thiamine, there was an extremely low response upon stimulation, and in the absence of the thiamine the reporter activities returned to almost the same level as that in wild-type cells (Fig. 1D and supplemental Table S2). These results again indicate that the luciferase reporter reflects Sty1 activity in living cells.

The integrated 3×CRE::luc(R2.2) reporter showed much lower sensitivity than the multicopy reporter, and it failed to detect the activity in some knock-out cells. Therefore, we used the multicopy reporter for most of knock-out cells showing low Atf1 activity. Although the copy number of plasmids in fission yeast is variable, the S.D. obtained with the multicopy reporter suggests that the experiments are reliable.

To investigate the role of Mcs4 in multiple-stress-induced responses, we monitored the reporter activities in Δmcs4 cells. It has been reported that Mcs4 acts as a “response regulator” protein of the prototypical bacterial two-component system transmitting oxidative stress signals to the Sty1 MAPK cascade (6–8, 25). In Δmcs4 cells, the basal and stimulated activities of the reporter were markedly low as the basal reporter activity in Δmcs4 cells was only about 5% of that in wild-type cells (Table 1). Notably, the reporter activity responded only weakly (∼2-fold basal levels) to osmotic stress, whereas it responded well to CdCl2 and to LG (∼7-fold and 17-fold basal levels, respectively). Contrary to the study showing that Mcs4 is a response regulator transmitting oxidative stress signals to the Sty1 cascade (8), our present data suggest that Mcs4 functions as a regulator primarily in response to osmotic stress and to a lesser extent to oxidative stress agents.

TABLE 1.

3×CRE::luc(R2.2) reporter activity in various cells

Cells were transformed with the reporter plasmid containing the 3×CRE::luc(R2.2) reporter gene. The effect of various stimuli on the Atf1 activation was monitored as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Relative light units are expressed as the ratio of light emission of each sample to the basal (without stimulation) light emission of wild-type cells in EMM at 180 min. Values from at least three independent experiments are expressed as means ± S.D.

| Cell types | Basal | Stimuli |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KCl (0.3 m) | CdCl2 (2 mm) | LG (2% → 0.1%) | ||

| Wild type | 1.0 ± 0.096 | 3.5 ± 0.31 | 2.1 ± 0.20 | 3.3 ± 0.48 |

| Δmcs4 | 0.048 ± 0.016 | 0.095 ± 0.035 | 0.34 ± 0.13 | 0.82 ± 0.40 |

| Δwis4 | 0.078 ± 0.014 | 0.19 ± 0.041 | 0.55 ± 0.068 | 0.66 ± 0.17 |

| Δwin1 | 0.15 ± 0.013 | 0.26 ± 0.028 | 1.0 ± 0.17 | 0.80 ± 0.18 |

| Δwis4Δwin1 | 0.015 ± 0.0016 | 0.017 ± 0.0033 | 0.15 ± 0.032 | 0.10 ± 0.010 |

| Δwis1 | 0.0031 ± 0.00054 | 0.0039 ± 0.0014 | 0.0018 ± 0.00078 | 0.0036 ± 0.0019 |

| Δwis4Δwin1Δbyr2Δmkh1 | 0.0097 ± 0.00034 | 0.011 ± 0.0085 | 0.19 ± 0.049 | 0.11 ± 0.0099 |

| Δpyp1 | 3.18 ± 0.11 | 6.73 ± 0.64 | 3.32 ± 0.37 | 2.91 ± 0.59 |

| pyp1C470S | 3.06 ± 0.15 | 5.62 ± 0.38 | 2.81 ± 0.56 | 2.85 ± 0.14 |

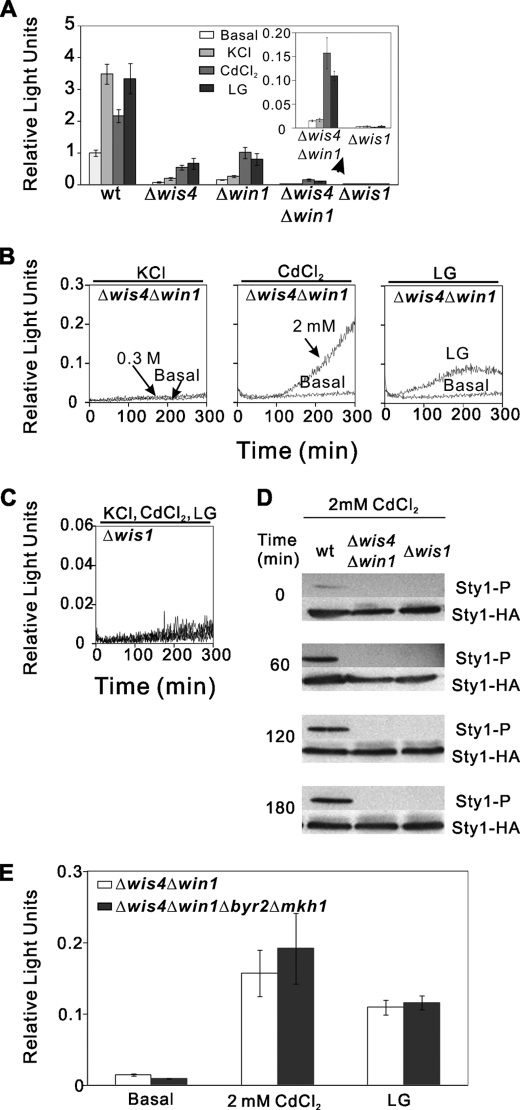

MAPK Sty1 is directly phosphorylated by a MAPKK, Wis1, which is phosphorylated by two redundant MAPKKKs, Wis4 and Win1 (26). In Δwis1 cells, the promoter activities induced by the three stress agents, respectively, were abolished (Fig. 2, A and C, and Table 1). The Sty1 phosphorylation level was also monitored under the treatment with 2 mm CdCl2, and no detectable Sty1 phosphorylation was observed in Δwis1 cells (Fig. 2D). These results are consistent with the notion that Wis1 is required for the activation of Sty1 under several stress conditions (10, 11).

FIGURE 2.

KCl-stimulated Sty1 activation is dependent on MAPKKKs, whereas both the CdCl2- and LG-stimulated activations are independent of MAPKKKs. A, both CdCl2- and LG-stimulated activations of Sty1 are dependent on MAPKK Wis1 but not MAPKKKs Wis4 and Win1. Wild-type, Δwis4, Δwin1, Δwis4Δwin1, and Δwis1 cells, respectively, transformed with the reporter plasmid were treated as indicated. Data were analyzed and plotted as in Fig. 1D, and the inset is a magnification of the results obtained in Δwis4Δwin1 cells and Δwis1 cells. B, MAPKKKs Wis4 and Win1 are required for KCl-stimulated Sty1 activation but not for CdCl2- or LG-stimulated activations. The Δwis4Δwin1 cells transformed with the reporter plasmid were treated as indicated. C, MAPKK Wis1 is absolutely required for the activation of Sty1. The Δwis1 cells transformed with the reporter plasmid were treated with the three agents, respectively, as described in Fig. 1A. D, detection of phosphorylated Sty1 by immunoblotting under the treatment with CdCl2 is shown. Cells were grown in YPD medium at 27 °C. CdCl2 was added to a final concentration of 2 mm at time 0, and aliquots of cells were harvested every 60 min. Sty1 protein was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-phosphorylated p38 (Thr180/Tyr182) MAPK antibody (Sty1-P) and anti-HA antibody (Sty1-HA) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” E, CdCl2- and LG-stimulated activations are independent of MAPKKKs. Δwis4Δwin1 cells or Δwis4Δwin1Δbyr2Δmkh1 cells transformed with the reporter plasmid were untreated (basal) or treated with CdCl2 (2 mm) or LG. Data were analyzed and plotted as in Fig. 1D.

We then monitored the reporter activity in single MAPKKK knock-out cells, Δwis4 and Δwin1. In Δwis4 or Δwin1, similar to Δmcs4 cells, both the basal activity and the stimulated activity of the reporter were very low. It should be noted that the response to KCl stimulation was only weakly observed, in contrast to the clear responses to CdCl2 and LG (Fig. 2A). These results, together with the results obtained in Δmcs4 cells, suggest that Mcs4, Wis4, and Win1 may synergistically mediate osmotic stress signal to the MAPKK Wis1. In Δwis4Δwin1 double knock-out cells, no reporter activity was observed by KCl treatment, whereas CdCl2 and LG, respectively, showed significant stimulated reporter activity (Fig. 2, A and B, and Table 1). The phosphorylation level of Sty1 under the treatment with CdCl2 was not detected in Δwis4Δwin1 double knock-out cells by immunoblotting (Fig. 2D), further indicating that the 3×CRE::luc(R2.2) reporter assay has a much higher sensitivity than the immunoblot detection. Our findings of the reporter assay suggest that KCl-stimulated Sty1 activation is dependent on MAPKKKs Wis4 and Win1, whereas both CdCl2- and LG-stimulated activations are independent. Possibly, two other known fission yeast MAPKKKs, Byr2 and Mkh1, compensate for the loss of Wis4 and Win1.

Byr2 is required for mating and sporulation (27), and Mkh1 regulates morphogenesis and cell wall integrity (28). We constructed the strains lacking all of the four MAPKKKs and tested them using this reporter assay. In Δwis4Δwin1Δbyr2Δmkh1 tetra knock-out cells, similar reporter activities were observed compared with those in Δwis4Δwin1 double knock-out cells upon the treatment with CdCl2 or LG (Fig. 2E and Table 1). This further suggests that both CdCl2- and LG-stimulated MAP kinase activations are MAPKKK-independent.

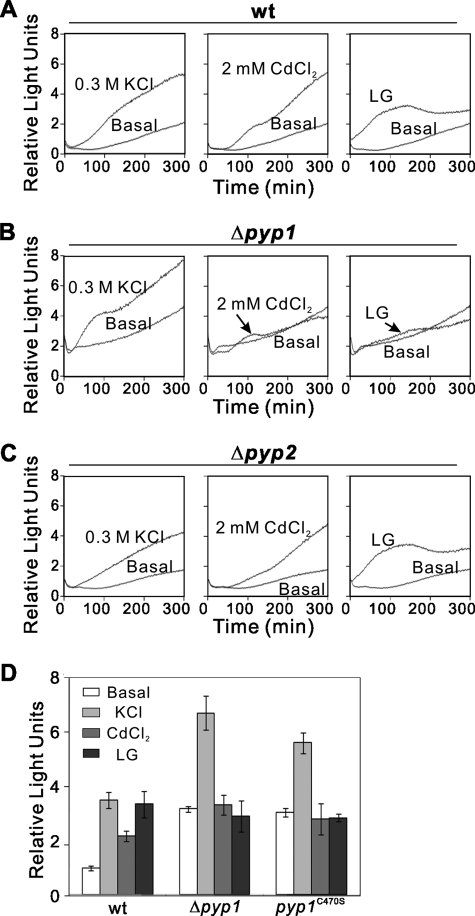

These results led us to look into the negative regulators of the Sty1 MAPK cascade. The protein-tyrosine phosphatases Pyp1 and Pyp2 are found to function by inactivating Sty1 (12). We then monitored the reporter activities in Δpyp1 and Δpyp2 cells. Higher basal reporter activity was observed in Δpyp1 cells than in wild-type or Δpyp2 cells (Fig. 3, A–C). This is consistent with the notion that Pypl and Pyp2 dephosphorylate and inhibit the Styl MAPK (12) and that Pyp1 is a major tyrosine phosphatase for Sty1 dephosphorylation (3). In Δpyp1 cells, notably, the promoter activity stimulated by the treatment with CdCl2 or LG was not or was barely observed, whereas the stimulation by KCl was clearly observed (Fig. 3B). In Δpyp2 cells, the reporter activity stimulated by the three stress agents, respectively, was similar to that in wild-type cells (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that Pyp1, but not Pyp2, is responsible for sensing and transmitting the signals to Sty1 MAPK upon treatment with CdCl2 or LG.

FIGURE 3.

Deletion of pyp1+ gene abolished both CdCl2- and LG-stimulated Sty1 activation, whereas KCl-stimulated activation was unaffected. A, wild-type cells transformed with the reporter plasmid were incubated with d-luciferin and treated as indicated. B and C, Δpyp1 and Δpyp2 cells transformed with the reporter plasmid were treated as indicated. D, the highly conserved Cys residue of Pyp1 may function as a sensor for CdCl2 and LG. Wild-type, Δpyp1, and Δpyp2 cells containing integrated pREP1-pyp1C470S-GFP, transformed with the reporter plasmid, were treated as indicated. Data were analyzed and plotted as in Fig. 1D.

Notably, Δpyp1 cells showed a higher basal reporter activity than wild-type cells (Fig. 3, A and B), suggesting that even in the absence of extracellular stresses, Sty1 is still phosphorylated by MAPKK Wis1. Consistently, Δwis1Δpyp1 double knock-out cells showed extremely low basal and response reporter activities that were similar to those of Δwis1 single knock-out cells (data not shown), indicating that high basal reporter activity in Δpyp1 cells is dependent on the activity of Wis1 and on its Sty1-phosphorylating activity and suggests that Wis1 has some activity and phosphorylates Sty1 in the absence of two upstream MAPKKKs. Consistent with this notion, a previous article by Samejima et al. showed that Wis1AA (unphosphorylated form) still phosphorylates Sty1 (3). This seems to be the reason why Wis1 is absolutely required for Sty1 activation by CdCl2 and LG. Also, morphological comparison between Δwis1 cells and wild-type cells overexpressing pyp1+ has been performed. Similar to Δwis1 cells, overexpression of pyp1+ in a wild-type background led to significant cell elongation (supplemental Fig. 1), indicating that Pyp1 is actually opposing the Wis1 activity.

Recent studies in mammalian cells have reported that CdCl2 induces the formation of reactive oxygen species (29–31) and that LG causes a metabolic oxidative stress (32, 33). The highly conserved Cys residue located within the core catalytic domains of all known protein-tyrosine phosphatases is essential for the catalytic activity in vitro (34–36), and it has been reported that the conserved Cys residue in PTPα is sensitive to reactive oxygen species and that it may function as a redox sensor (37). In fission yeast, to determine whether this Cys residue (Cys470) is also crucial for the ability of Pyp1 to sense the signals induced by the treatment with CdCl2 and LG, respectively, the pREP1-pyp1C470S-GFP was integrated into the chromosome of Δpyp1 cells. The mutation of this Cys residue showed similar reporter activity compared with that in Δpyp1 cells upon the treatment with the three stress agents, respectively (Fig. 3D and Table 1). This suggests that alteration of the Cys residue in the catalytic site abolishes the ability to sense and to transmit the signals to Sty1 MAPK upon the treatment with CdCl2 and LG, respectively, indicating that Cys470 may function as a sensor for these two stress agents.

In summary, in contrast with the hypothesis that all of the stresses are mediated by the two MAPKKKs (38) (Fig. 4A), here we show evidence in favor of the conclusion shown in Fig. 4B: KCl stimulates the Sty1 MAPK pathway through MAPKKKs, whereas CdCl2 and LG stimulate the pathway through the inhibition of Pyp1 independently of MAPKKKs. This is in contrast with a previous hypothesis that insights on the mechanisms of stress response and signal transduction in fission yeast may help in studying similar mechanisms in higher eukaryotes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Takashi Toda and Dr. Mitsuhiro Yanagida for providing strains and plasmids and Susie O. Sio for a critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Global Centers of Excellence Program and research grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1, Tables S1 and S2, and additional references.

- MAPKKK

- MAPK kinase kinase

- CRE

- cAMP response element

- EMM

- Edinburgh minimal medium

- LG

- low glucose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marshall C. J. (1994) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 4, 82–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Degols G., Russell P. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 3356–3363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samejima I., Mackie S., Fantes P. A. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 6162–6170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shieh J. C., Wilkinson M. G., Buck V., Morgan B. A., Makino K., Millar J. B. (1997) Genes Dev. 11, 1008–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiozaki K., Russell P. (1995) Nature 378, 739–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buck V., Quinn J., Soto Pino T., Martin H., Saldanha J., Makino K., Morgan B. A., Millar J. B. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 407–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aoyama K., Mitsubayashi Y., Aiba H., Mizuno T. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 4868–4874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen A. N., Lee A., Place W., Shiozaki K. (2000) Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 1169–1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiozaki K., Russell P. (1996) Genes Dev. 10, 2276–2288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Degols G., Shiozaki K., Russell P. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 2870–2877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato T., Jr., Okazaki K., Murakami H., Stettler S., Fantes P. A., Okayama H. (1996) FEBS Lett. 378, 207–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Millar J. B., Buck V., Wilkinson M. G. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 2117–2130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiozaki K., Russell P. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 492–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen A. N., Shiozaki K. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1653–1663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaits F., Degols G., Shiozaki K., Russell P. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 1464–1473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaits F., Russell P. (1999) Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 1395–1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreno S., Klar A., Nurse P. (1991) Methods Enzymol. 194, 795–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toda T., Dhut S., Superti-Furga G., Gotoh Y., Nishida E., Sugiura R., Kuno T. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 6752–6764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neely L. A., Hoffman C. S. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 6426–6434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng L., Sugiura R., Takeuchi M., Suzuki M., Ebina H., Takami T., Koike A., Iba S., Kuno T. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 4790–4800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma Y., Sugiura R., Saito M., Koike A., Sio S. O., Fujita Y., Takegawa K., Kuno T. (2007) Curr. Genet. 52, 97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogiso Y., Sugiura R., Kamo T., Yanagiya S., Lu Y., Okazaki K., Shuntoh H., Kuno T. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 2324–2331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basi G., Schmid E., Maundrell K. (1993) Gene 123, 131–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forsburg S. L., Sherman D. A. (1997) Gene 191, 191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quinn J., Findlay V. J., Dawson K., Millar J. B., Jones N., Morgan B. A., Toone W. M. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 805–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Price M. A., Cruzalegui F. H., Treisman R. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 6552–6563 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masuda T., Kariya K., Shinkai M., Okada T., Kataoka T. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 1979–1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loewith R., Hubberstey A., Young D. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 113, 153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avery S. V. (2001) Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 49, 111–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schützendübel A., Polle A. (2002) J. Exp. Bot. 53, 1351–1365 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valko M., Morris H., Cronin M. T. (2005) Curr. Med. Chem. 12, 1161–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee Y. J., Galoforo S. S., Berns C. M., Chen J. C., Davis B. H., Sim J. E., Corry P. M., Spitz D. R. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 5294–5299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song J. J., Rhee J. G., Suntharalingam M., Walsh S. A., Spitz D. R., Lee Y. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 46566–46575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guan K. L., Dixon J. E. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 17026–17030 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho H., Ramer S. E., Itoh M., Kitas E., Bannwarth W., Burn P., Saito H., Walsh C. T. (1992) Biochemistry 31, 133–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barford D., Flint A. J., Tonks N. K. (1994) Science 263, 1397–1404 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Persson C., Sjöblom T., Groen A., Kappert K., Engström U., Hellman U., Heldin C. H., den Hertog J., Ostman A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 1886–1891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiozaki K., Shiozaki M., Russell P. (1997) Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 409–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.