Abstract

SIRT1 is a protein deacetylase that has emerged as a therapeutic target for the development of activators to treat diseases of aging. SIRT1-activating compounds (STACs) have been developed that produce biological effects consistent with direct SIRT1 activation. At the molecular level, the mechanism by which STACs activate SIRT1 remains elusive. In the studies reported herein, the mechanism of SIRT1 activation is examined using representative compounds chosen from a collection of STACs. These studies reveal that activation of SIRT1 by STACs is strongly dependent on structural features of the peptide substrate. Significantly, and in contrast to studies reporting that peptides must bear a fluorophore for their deacetylation to be accelerated, we find that some STACs can accelerate the SIRT1-catalyzed deacetylation of specific unlabeled peptides composed only of natural amino acids. These results, together with others of this study, are at odds with a recent claim that complex formation between STACs and fluorophore-labeled peptides plays a role in the activation of SIRT1 (Pacholec, M., Chrunyk, B., Cunningham, D., Flynn, D., Griffith, D., Griffor, M., Loulakis, P., Pabst, B., Qiu, X., Stockman, B., Thanabal, V., Varghese, A., Ward, J., Withka, J., and Ahn, K. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 8340–8351). Rather, the data suggest that STACs interact directly with SIRT1 and activate SIRT1-catalyzed deacetylation through an allosteric mechanism.

Keywords: Allosteric Regulation, Drug Design, Enzyme Kinetics, Enzyme Mechanisms, Sirtuins, Drug Design, Enzyme Kinetics, Enzyme Mechanisms, Sirtuins, Enzyme Activation

Introduction

The sirtuins are a family of enzymes that catalyze the NAD+-dependent deacetylation of ϵ-acetyl-Lys residues of proteins (1–3). Interest in these enzymes stems from the roles they are thought to play in human disease. Of particular interest is SIRT1, which has been implicated in a number of age-related diseases and biological functions involving cell survival, apoptosis, stress resistance, fat storage, insulin production, and glucose and lipid homeostasis (4, 5). Involvement in these diverse biologies is thought to occur through deacetylation of its many known in vivo protein substrates, including histones H1, H3, and H4, p53, p300, FOXOs 1, 3a, and 4, p65, HIVTat, PGC-1α, PCAF, MyoD, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, Ku70, and others (3, 6).

Studies in which SIRT1 protein and activity levels have been manipulated, through gene deletion or overexpression in mice, have validated the beneficial impact of increased SIRT1 activity in several models of disease including those involving metabolic stress (4, 5). This has recently been observed in humans as well where reduced SIRT1 expression in insulin-sensitive tissues was associated with reduced energy expenditure (7). Therefore, for many of the diseases in which SIRT1 is thought to play a role, therapeutic effects are predicted to follow from the administration of activators of the deacetylase activity of this enzyme. Over the past several years, SIRT1-activating compounds3 (STACs), including resveratrol and more target-specific, chemically distinct molecules, have been developed (8–10). When tested in cell-based and animal models of these diseases, STACs produce effects consistent with direct activation of this enzyme (8, 11–17).

At the molecular level, much remains to be learned concerning the mechanism by which these compounds accelerate SIRT1-catalyzed deacetylation. One area of interest is the dependence of activation on structural features of peptide substrates.

This aspect of SIRT1 activation first came to light in 2005, when two studies reported that resveratrol (18) can activate the SIRT1-catalyzed deacetylation of Ac-Arg-His-Lys-LysAc-AMC4 but not the amide or acid analogs of this peptide that lack the AMC fluorophore (19, 20). Recently, the results with resveratrol were confirmed (21) and extended by Pacholec et al. (22) to include SRT1460, SRT1720, and SRT2183, originally described by Milne et al. (8) (Fig. 1). Pacholec et al. (22) investigated the STAC-mediated activation of SIRT1 using several acetylated peptide substrates, including the TAMRA-labeled peptide substrate (TAMRA-peptide; see Table 1 for structure) used by Milne et al. (8), and two known protein substrates of SIRT1. One of the primary conclusions of this work is that the presence of the TAMRA label is necessary for activation because no activation was observed with unmodified peptides or protein substrates.

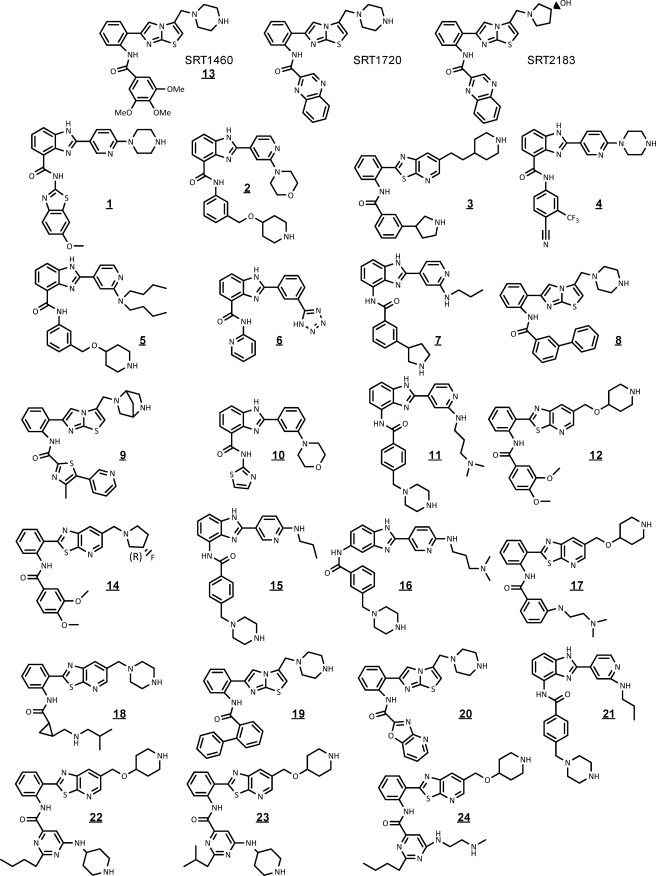

FIGURE 1.

Structures of STACs used in the studies of this report.

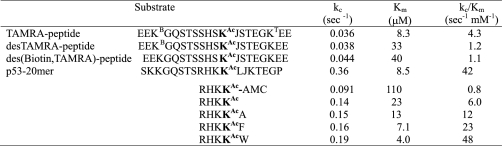

TABLE 1.

Summary of steady-state kinetic parameters for SIRT1 substrates

KB is biotinylated lysine, KT is lysine labeled with a TAMRA group, and J is norleucine. All peptides are blocked at the N-terminus with an acetyl group and at the C terminus with an amide. Experiments were conducted at 25 °C, in a pH 7.5 buffer containing 50 mm HEPES and 150 mm NaCl. [NAD+]o = 2 mm and [SIRT1]o varied from 50 to 1,000 nm, depending on the reactivity of the substrate. Each parameter is the average of 2 or 3 independent experiments. Standard deviations (n = 3) or deviation from the mean (n = 2) are less than 15% in all cases.

In this study, we report the results of studies aimed at understanding the dependence of SIRT1 activation on substrate structure. Although we found, in agreement with Pacholec et al. (22), that certain STACs can form complexes with the TAMRA-peptide, we conclude that these complexes are not involved in the activation of SIRT1. Rather, we propose that STACs interact directly with this enzyme and activate deacetylation by an allosteric mechanism. Such a mechanism can account for the substrate structural dependence of SIRT1 activation described above (19–22), as well as the observations reported herein that STACs can accelerate the deacetylation of unlabeled peptides composed only of natural amino acids.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

All peptides were prepared by BioPeptide (San Diego, CA) and shown to be at least 95% pure by analytical HPLC analysis. NADH, NAD+, and α-ketoglutarate were from Sigma. The preparation of bovine glutamate dehydrogenase (Sigma) was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 30 min before use. Full-length, human SIRT1 and the truncated version used for biophysical studies SIRT1(183–664) were prepared as described previously and shown to have equivalent kinetic properties (8). The nicotinamidase PNC1 was prepared as described by Denu and colleagues (23).

Structures and Synthesis of STACs

Structures of all the STACs of this study appear in Fig. 1. Experimental procedures and characterization data for 22, 23, and 24 can be found in the supplemental data. SRT1460, SRT1720, and SRT2183 were prepared according to literature procedures (8), as was 20 (10). Compound 19 was prepared according to the procedures described for structurally similar compounds (10). Compounds 20 (24), 9 (25), and 10, 21, and 11 (26) were prepared according to the procedures described in the relevant patents. The synthesis of 3 will be published elsewhere.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry Experiments

ITC experiments were performed using either a VP-ITC system or an iTC200 system (MicroCal) at 26 °C in a buffer composed of 137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 2 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, 5% (v/v) glycerol, and 50 mm HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.3. SIRT1(183–664) was purified and dialyzed against the buffer, centrifuged, and degassed before the experiment. The peptide and compounds were dissolved in the final dialysis buffer, and their pH values were adjusted to match that of the protein solution. In a typical binding experiment to characterize the STAC/TAMRA-peptide interaction performed on the VP-ITC system, 1 mm TAMRA-peptide was injected in 35 aliquots of 8 μl (except the first injection, which was 2 μl) into a 1.4699-ml sample cell containing 100 μm STAC. To characterize this interaction using the iTC200 system, 1 mm TAMRA-peptide was injected in 20 aliquots of 2 μl (except the first injection, which was 0.5 μl) into a 0.202-ml sample cell containing 100 μm STAC. For STACs with poor solubility, the concentrations were adjusted accordingly. To characterize the interaction of SRT1460 with the TAMRA-peptide, 5 mm TAMRA-peptide and 0.5 mm SRT1460 were used.

To characterize the interaction of a STAC with SIRT1(183–664) on the VP-ITC system, 100 μm enzyme was injected in 35 aliquots of 8 μl (except the first injection, which was 2 μl) into a 1.4699-ml sample cell containing 10 μm STAC. In a typical binding experiment on the iTC200 system, 100 μm enzyme was injected in 20 aliquots of 2 μl (except the first injection, which was 0.5 μl) into a 0.202-ml sample cell containing 10 μm STAC. In all cases, data were corrected for the heat of dilution and fitted using a nonlinear least squares routine using a single-site binding model with Origin for ITC version 7.0383 (MicroCal) with the stoichiometry (n), the enthalpy of the reaction (ΔH), and the association constant (Ka) calculated.

Fluorescence Binding Experiments for the Interaction of 11 with SIRT1

SIRT1(183–664) was dialyzed against a buffer composed 137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 2 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, 5% (v/v) glycerol, and 50 mm HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.3. 11 was dissolved in the final dialysis buffer, and its pH values were adjusted to match that of the protein solution. The fluorescence emission spectra of 11 in the absence or presence of different concentrations of enzyme was monitored on a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M5 with excitation at 315 nm. The fluorescence intensity change at 450 nm was plotted against the concentration of SIRT1(183–664) and fitted using a standard binding equation.

Screening of Sirtris Compound Collection Using desTAMRA-Peptide

Our collection of ∼5,000 SIRT1 activators was screened using the BioTrove mass spectrometry system, as described previously (8). In this screen, [SIRT1]o = 5 nm, [desTAMRA-peptide]o = 1 μm = Km/33, and [NAD+]o = 30 μm = Km/10. Compounds were present at 10 μm, and the assays were conducted in a pH 7.4 buffer containing 50 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, 1% DMSO, and 0.025% BSA.

Kinetic Studies of Interaction of STACs with SIRT1

Two methods were used in these studies. One, which was used for TAMRA-peptide, desTAMRA-peptide, des(biotin,TAMRA)-peptide, and p53 20-mer, used a previously described mass spectroscopic method for detection of peptide reaction products (8). The other, used with peptides of general structure Ac-Arg-His-Lys-LysAc-X, used a continuous, enzyme-coupled method reported previously (23), in which the SIRT1 product nicotinamide is first converted into nicotinic acid and ammonia by the action of PNC1, and the ammonia is then used by glutamate dehydrogenase to convert α-ketoglutarate into glutamate. This reaction occurs with oxidation of NADH to NAD+, which is accompanied by a change in absorbance at 340 nm (Δϵ340 = −6,200 m−1 cm−1).

Kinetic experiments to characterize activators were run on a PerkinElmer Life Sciences Lambda 25 spectrophotometer equipped with a water-jacketed, eight-cell changer maintained at 25 °C. In a typical kinetic experiment, all components of the reaction solution except SIRT1 were added to a 1-ml cuvette and allowed to reach thermal equilibrium. Final concentrations of the coupling system components were: 1 μm PNC1, 0.23 mm NADH, 3.4 mm α-ketoglutarate, and 20 units/ml bovine glutamate dehydrogenase. This solution also contained peptide substrate, NAD+, and activator, at concentrations indicated under “Results.” The final DMSO concentration was kept constant at 1%, and the buffer used in these experiments was 50 mm HEPES, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, pH 7.5. While the system was reaching thermal equilibrium, the absorbance was monitored to provide an accurate estimate of the background rate, which was subtracted from the reaction rate after the addition of SIRT1.

General Treatment of Activation Data

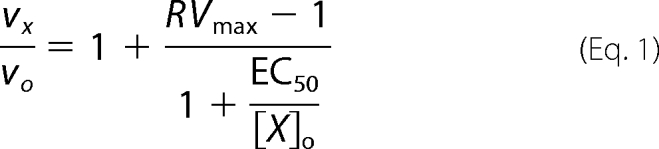

Activator titrations were plotted as relative velocity (RV, i.e. the ratio of vx, velocity in the presence of activator X, to vo, velocity in the absence of activator) versus [X]o, initial concentration of activator, and fit by nonlinear least squares to the mechanism-independent expression for enzyme activation of Equation 1

|

where RVmax is the maximum relative velocity (i.e. vx/vo at infinite [X]o) and EC50 is the activator concentration at which vx/vo = (RVmax −1)/2. EC50 is a function of the kinetic mechanisms of both catalysis and activation and the concentrations of substrates.

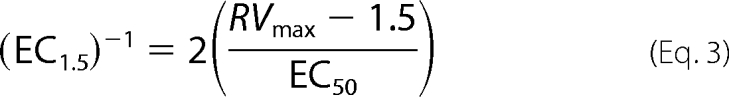

For activators whose insolubility and potency prohibited achieving high enough concentrations for accurate estimates of RVmax and EC50, activator potency can be expressed as EC1.5, which is the concentration of activator needed to achieve 1.5-fold activation. EC1.5 can be shown to equal

|

and thus is a reflection of activator efficacy, with a dependence on both RVmax and EC50. For a series of activators in which RVmax is roughly the same, the ratio EC1.5/EC50 will be similar for all members of the series, and thus, either EC1.5 or EC50 can be used as the measure of activator potency.

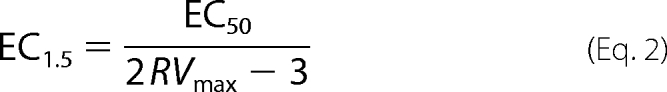

The reciprocal of EC1.5 is a direct measure of activator efficacy and equals

|

It can be seen that (EC1.5)−1 is analogous to Vmax/Km of standard steady-state enzyme kinetics.

RESULTS

Structures and Steady-state Kinetic Parameters for SIRT1 Substrates

Table 1 summarizes steady-state kinetic parameters for the peptide substrates used in this study. These parameters were all determined using the PNC1/glutamate dehydrogenase-coupled assay described under “Experimental Procedures” and agree with data obtained using the mass spectrometry-based assay first described by Milne et al. (8).

Discovery and Initial Characterization of STACs

Our initial lead structures were identified in a high throughput screening campaign that used a fluorescence polarization assay, with TAMRA-peptide as substrate (8). This 20-mer is centered around Lys-382 of p53, a natural substrate for SIRT1. The modifications of the sequence of TAMRA-peptide relative to p53 were made specifically for purposes of the assay (8, 27). Characterization of the initial screening hits and all subsequent studies were conducted using TAMRA-peptide and a mass spectrometry-based assay (8).

As the structure-activity relationship (SAR) around our lead compounds evolved, we tested many of the newer STACs for their ability to activate the deacetylation of desTAMRA-peptide and found that none were able to activate the deacetylation of this peptide (data not shown). These results are consistent with those recently reported by Pacholec et al. (22) and indicate that activation of SIRT1 by STACs is dependent on structural features of the substrate.

Studies of the Interaction of STACs with TAMRA-Peptide Suggest That STAC-TAMRA-Peptide Complexes Play No Role in SIRT1 Activation

In the course of our studies of SIRT1 activation, we found that some STACs bind to TAMRA-peptide to form activator-substrate complexes. These results confirm the observation that SRT1460 and SRT1720 can bind to TAMRA-labeled peptides (22).

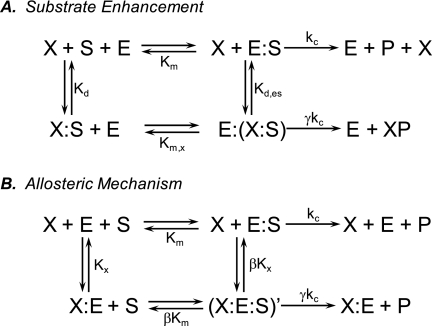

The simplest activation mechanism involving activator-substrate complexes is shown in Fig. 2A,5 according to which activation is observed when X-S is turned over more rapidly than S, that is, when Km,x < Km or γ > 1 or both. Examination of this mechanism indicates that activation is driven by formation of the activator-substrate complex X-S, meaning that stable X-S complexes with lower Kd values should result in more potent activation.

FIGURE 2.

Mechanisms of enzyme activation. Mechanism A, activation by substrate enhancement. Activator binds to substrate to form activator-substrate X-S. Activation occurs when X-S is more efficiently turned over than S, that is, when Km,x < Km or γ > 1 or both. Mechanism B, activation through an allosteric mechanism. Activator and substrate bind to allosteric and active sites, respectively, to form (X-E-S)′. Activation occurs when γ/β > 1.

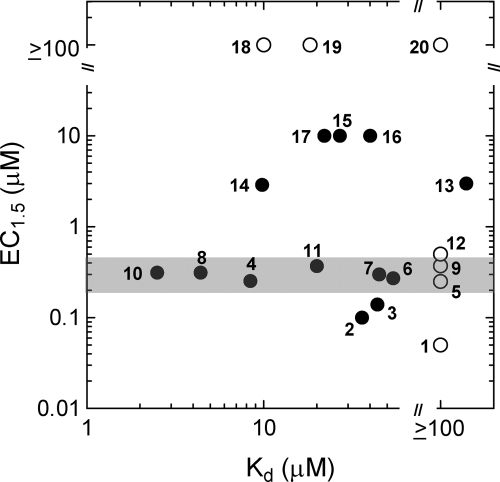

To explore the possibility that X-S might be of mechanistic significance, we determined Kd values for the binding of STACs to TAMRA-peptide for 20 compounds that range in potency from EC1.5 = 0.05 to ≥ 100 μm (see supplemental Fig. S1 for representative ITC titrations). These data are plotted in Fig. 3 and clearly demonstrate a lack of correlation between STAC efficacy and affinity of STACs for TAMRA-peptide. Significantly, there are compounds that activate SIRT1 but show no detectable binding to the TAMRA-peptide, such as 1, with EC1.5 = 0.05 μm, Kd ≥ 100 μm, or 9, with EC1.5 = 0.4 μm, Kd ≥ 100 μm (see supplemental Fig. S1A for ITC results), and there are compounds that do not activate, but bind to TAMRA-peptide, such as 19, with EC1.5 ≥ 100 μm, Kd = 20 μm.

FIGURE 3.

Lack of correlation between STAC efficacy (EC1.5) and STAC affinity for TAMRA-peptide (Kd). Open circles denote compounds with Kd ≥ 100 μm. The gray bar highlights a series of compounds with Kd values that range from 2.5 to ≥100 μm but have the same EC1.5 value of around 0.3 μm. These determinations were all done in buffers containing no cosolvent.

In the plot of Fig. 3, it is interesting to note the compounds highlighted by the gray bar. Although these compounds have Kd values that range from 2.5 μm to greater than 100 μm, they have essentially the same EC1.5 value of 0.3 μm. This again points to the lack of correlation between activator potency and affinity for substrate.

One can speculate that perhaps for a certain structural class of STAC, a correlation might exist between EC1.5 and Kd. Such a correlation would define a line connecting 10 and 20 in Fig. 3. Examination of the structures of the specific compounds on this line reveals that they represent all three structural classes comprising the compounds of Fig. 3. Thus, there is no correlation between EC1.5 and Kd even if we try to parse a potential correlation according to STAC structural class.

These results suggest that the ability of STACs to activate the SIRT1-catalyzed deacetylation of the TAMRA-peptide is unrelated to the affinity of STACs for this substrate.

Activation of SIRT1 toward the desTAMRA-Peptide

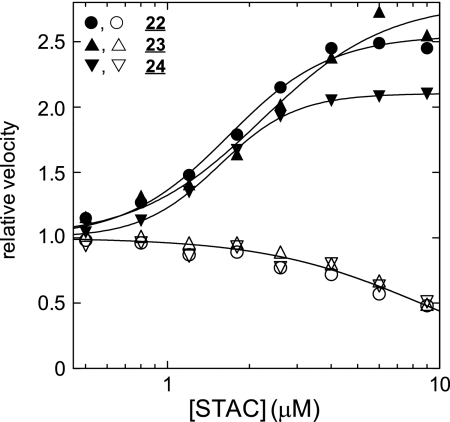

As mentioned above, among the several STACs tested, none activated the deacetylation of the desTAMRA-peptide. To determine whether there might be exceptions to this observation, we screened our collection of over 5,000 STACs for their ability to activate the deacetylation of this peptide and identified three structurally related STACs: 22, 23, and 24. Activation titration curves for the three compounds are shown in Fig. 4, where it can be seen that all three activate the SIRT1-catalyzed deacetylation of desTAMRA-peptide with EC50 and RVmax values of around 2 and 2.3 μm respectively. These results demonstrate that a peptide lacking the TAMRA moiety can still support activation by some STACs.

FIGURE 4.

Modulation of the catalytic activity of SIRT1. Closed symbols correspond to activation of the deacetylation of desTAMRA-peptide. Data points were fit to Equation 1 and yielded: 22, EC50 = 1.7 ± 0.1 μm, RVmax = 2.6 ± 0.1; 23, EC50 = 2.2 ± 0.3 μm, RVmax = 2.8 ± 0.2; 24, EC50 = 1.5 ± 0.1 μm, RVmax = 2.1 ± 0.1. Open symbols correspond to inhibition of the deacetylation p53 20-mer. Data points were fit to the equation RV = 1/(1+([X]o/Ki, apparent)) and yielded: 22, Ki, apparent = 9 ± 4 μm; 23, Ki, apparent = 10 ± 1 μm; 24, Ki, apparent = 9 ± 3 μm.

The fact that so few compounds were identified in this screen deserves comment. Recall that the compounds tested were not a random collection of compounds but had been optimized to activate the deacetylation of TAMRA-peptide. That only three of these compounds activated the deacetylation of desTAMRA-peptide is consistent with the known dependence of SIRT1 activation on substrate structure (19–22), and moreover, is an indication of how strong this dependence is. In related experiments, we found that compounds 22, 23, and 24 did not activate the deacetylation of des(biotin,TAMRA)-peptide, suggesting that a chemical moiety having some measure of steric bulk needs to be present on peptide substrates for their deacetylation to be activated by STACs.

Inhibition of the SIRT1-catalyzed Deacetylation of p53 20-mer

To further study the influence of substrate structure on the activation of SIRT1 by STACs, we tested 22, 23, and 24 for their ability to activate the SIRT1-catalyzed deacetylation of a peptide sequence composed of unmodified amino acids based on p53. Significantly, these three compounds inhibit the deacetylation of this substrate (Fig. 4). These results are consistent with the allosteric mechanism of Fig. 2B, where the ratio γ/β determines whether an allosteric modulator behaves as an activator or an inhibitor; i.e. activation is seen when γ/β > 1, whereas inhibition is seen when γ/β < 1.

Note that the mechanism of Fig. 2A cannot account for inhibition by STACs because in it, there is no provision for formation of a STAC-SIRT1 complex. Such a complex is required for inhibition to be observed.

Activation of the SIRT1-catalyzed Deacetylation of p53-based Peptides of General Structure Ac-Arg-His-Lys-LysAc-X

To further probe the influence of substrate structure on how STACs interact with SIRT1, we investigated the deacetylation of Ac-Arg-His-Lys-LysAc-X, where X is NH2, AMC, Ala-NH2, Phe-NH2, or Trp-NH2. It should be noted that Ac-Arg-His-Lys-LysAc-AMC (aka Fluor-de-Lys®, Enzo Life Sciences) is the substrate used in the assay that identified and characterized resveratrol (18) and is widely used in screens for activators and inhibitors of SIRT1.

Table 2 summarizes data in which we examined the effect of single concentrations of 22 and the three STACs published in Milne et al. (8) on the deacetylation of the five substrates described above. Similar to what we observed with the four 20-mers, the effect that a particular STAC has on deacetylation is dependent on the structure of the substrate. For example, although SRT1460 activates deacetylation when X is Phe-NH2 Trp-NH2, it inhibits deacetylation when X is AMC, and although 22 activates deacetylation when X is AMC or Trp-NH2, it inhibits deacetylation when X is NH2. None of the four compounds tested activate deacetylation when X is Ala-NH2.

TABLE 2.

Summary of the effect of STACs on the SIRT1-catalyzed deacetylation of Ac-Arg-His-Lys-LysAc-X

[STAC]o = 5 μm, [peptide]o < Km, [NAD+] = 70 μm. Each entry represents the average of 3 independent experiments; S.D. <15%.

| X | Relative velocity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRT1460 | SRT1720 | SRT2183 | 22 | |

| AMC | 0.7 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 2.7 |

| NH2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.7 |

| Ala-NH2 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| Phe-NH2 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| Trp-NH2 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.6 |

Table 3 summarizes Kd values for the binding of STACs to Ac-Arg-His-Lys-LysAc-X. As we saw with activation of the deacetylation of TAMRA-peptide, there is no correlation between the ability of a STAC to activate and its affinity for substrate.

TABLE 3.

Kd values for the binding STACs to Ac-Arg-His-Lys-LysAc-X

Kd determinations for SRT1720, SRT2183, and 22 were done in buffer containing 10% DMSO. For SRT1460, no cosolvent was necessary.

|

Kd (μm) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRT1460 | SRT1720 | SRT2183 | 22 | |

| AMC | >500 | >500 | >50 | >500 |

| NH2 | >500 | >500 | >50 | >500 |

| PheNH2 | >500 | >500 | >50 | 190 |

| TrpNH2 | >500 | 150 | >50 | 25 |

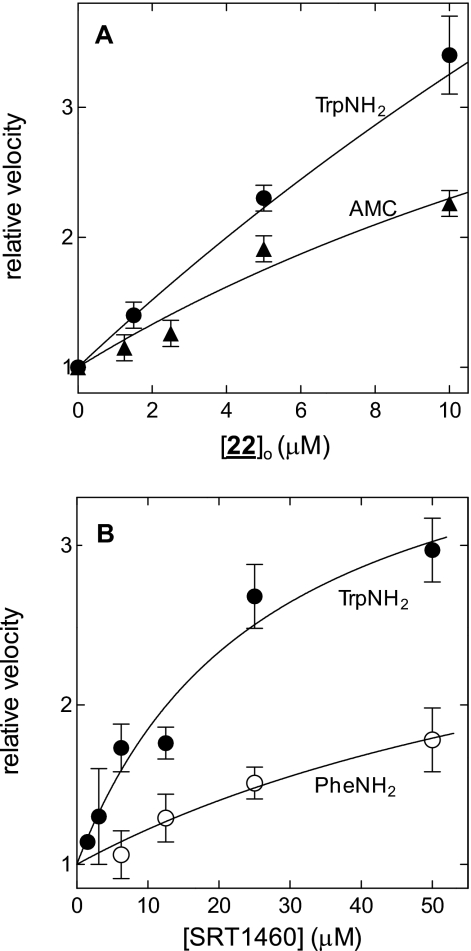

To examine this activation of in more detail, we determined the dependence of SIRT1 activity on STAC concentration. In Fig. 5A, we see that 22 activates the deacetylation of Ac-Arg-His-Lys-LysAc-AMC and Ac-Arg-His-Lys-LysAc-Trp-NH2 in a dose-dependent manner. Likewise, in Fig. 5B, SRT1460 is seen to dose dependently activate the deacetylation of Ac-Arg-His-Lys-LysAc-Phe-NH2 and Ac-Arg-His-Lys-LysAc-Trp-NH2. These results demonstrate, for the first time, that some STACs can accelerate the deacetylation of specific unmodified peptide substrates composed only of natural amino acids.

FIGURE 5.

22 and SRT1460 activate the SIRT1-catalyzed deacetylation of Ac-Arg-His-Lys-LysAc-X. A, X = Trp-NH2, EC1.5 = 1.9 μm; X = AMC, EC1.5 = 3.1 μm. B, X = Trp-NH2, EC1.5 = 5.0 μm, EC50 = 27 ± 8 μm, and RVmax = 4.1 ± 0.1; X = Phe-NH2, EC1.5 = 26 μm. These titrations represent 3–5 independent experiments, conducted over the course of several weeks. Each point is the mean ± S.D. from these experiments.

Binding of Activators to SIRT1 Is Inconsistent with Substrate Enhancement but Consistent with Enzyme Allostery

To investigate the binding of STACs to free SIRT1, we performed ITC titration experiments for 20 activators (see supplemental Fig. S2A for representative data). We found that 9 (EC50 = 2.4 μm), 21 (EC50 = 4.6 μm), and 11 (EC50 = 5.4 μm) bind to SIRT1 with Kx equal to 3.0, 0.43, and 0.32 μm, respectively, where Kx is the dissociation constant for the activator-enzyme complex (Fig. 2B). For 11, we confirmed the ITC result with a fluorescence binding experiment, where we determined a Kx of 0.27 μm (supplemental Fig. S2C).

Note that the mechanism of Fig. 2A excludes the possibility of complex formation between enzyme and activator. In contrast, the allosteric mechanism of Fig. 2B includes the formation of such a complex. It is important to note, however, that this complex need not accumulate to any appreciable extent in the steady state. That is, an allosteric mechanism can still operate even if Kx is very large, so long as βKx is similar in magnitude or less than the activator concentration. This is likely occurring with SIRT1 and many of the STACs that we studied. The fact that these STACs do not interact strongly with free SIRT1 simply means that Kx ≫ [X]o and suggests that these STACs preferentially bind to other steady-state forms of SIRT1, such as enzyme-substrate or enzyme-product complexes. That STACs can bind to enzyme-substrate complexes has been demonstrated by ITC experiments (8, 22).

The fact that the ratio EC50/Kx equals 10 for 21 and 11, but only 1 for 9, raises questions about the dependence of EC50 on Kx. For simple, one-substrate reactions of the sort shown in Fig. 2B, EC50 equals Kx multiplied by a term that is dependent on [S]o, so at low [S]o, EC50 = Kx, whereas at high [S]o, EC50 = βKx. However, for SIRT1, the relationship between these two parameters is much more complex and is dependent on the details of a kinetic mechanism not yet fully elucidated. Sirtuins are two-substrate enzymes, catalyzing reactions that proceed through kinetic mechanisms in which free enzyme, three different substrate-complexed forms of enzyme, as well enzyme-product complexes exist as steady-state intermediates (28). Understanding how EC50 depends on the affinity of an activator for free SIRT1, or any other steady-state form of SIRT1, must await further kinetic characterization of this complex system. Such studies are currently underway in our laboratory.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to gain an understanding of the mechanism by which STACs accelerate SIRT1-catalyzed deacetylation. In particular, we wanted to acquire sufficient data to differentiate between two broad mechanistic classes, one in which activator binds to substrate and another in which activator binds to enzyme.

The lack of correlation between the efficacy with which STACs activate SIRT1 and the affinity with which STACs bind peptide substrates argues against a mechanism involving the formation of activator-substrate complexes. However, this lack of correlation cannot, in and of itself, completely rule out such a mechanism.

One can imagine cases in which an activator binds to substrate with very low affinity, but the resultant activator-substrate complex is turned over by enzyme with great efficiency. Thus, a large Kd would be offset by a large γkc/Km,x (Fig. 2A), and potent activation would still be observed even in the face of an unstable activator-substrate complex that exists at low equilibrium concentrations. What is not considered in this analysis is the influence of activator structure on the efficacy of SIRT1 activation.

Although full structure-activity relationships for the three activator classes (i.e. benzimidazoles, imidazothiazoles, and thiazolopyridines) represented in Fig. 3 have yet to be described, they are consistent with the SAR observed for previously disclosed series (9, 10). Specifically, although a variety of substituents are tolerated on the terminal rings, it is differences in overall geometry that can result in significant changes in activity. For example, consider compounds 11 and 16, where the difference in relative position of the pendant substituents results in a 25-fold difference in EC1.5. Consistent with this relationship are the nearly identical activities found for 10, 4, 11, 7, 6, and 5. For these compounds, the overall molecular landscapes of the core and adjacent rings are very similar.

The SAR just described can readily be explained in terms of the interaction of activator at a specific and geometrically defined site on the SIRT1 but is less well understood in terms of binding of activator to aromatic ring systems (e.g. TAMRA or indole). If interactions between activator and these groups are mediated by aromatic ring stacking and π-π interactions, as they likely are, it is unclear how the shape of the activator would have an influence on this interaction. Consideration of activator structure also allows explanation of two features of Fig. 3 that cannot easily be explained in terms of mechanisms involving STAC-TAMRA-peptide complexes: compounds with nearly identical Kd values but very different EC1.5 values and compounds with nearly identical EC1.5 values but very different Kd values.

Kd values for 8 and 19 differ by only 4-fold, consistent with their nearly identical structures and the nonspecific interactions that likely characterize the complexes they form with TAMRA-peptide. In contrast, their EC1.5 values differ by more than 300-fold, consistent with the SAR outlined above, as well as the extensive literature documenting how seemingly small changes in ligand structure can lead to large changes in ligand affinity for its receptor. A relevant example is the SAR for allosteric activators of glucokinase, where it was recently found that simply changing an ethyl ester to a methyl ester in a series of N-acylureas results in a 20-fold increase in activation efficacy (29).

Similarly, structural isomers 11 and 16 differ in Kd by only 2-fold but display a 25-fold difference in EC1.5. Although such differences in EC1.5 are difficult to explain in the context of a mechanism involving activator-substrate complexes, they fit within an SAR that is based on the presumption that activator binds to a specific site on the enzyme surface (10).

We now turn to several groups of compounds that have the same EC1.5 values but different Kd values. These groups not only include the compounds delineated by the gray bar of Fig. 3 but also 17, 15, and 16, and 14 and 13. According to the mechanism of Fig. 2A, for a series of activators to maintain a given potency despite increasing values of Kd, rates of enzymatic turnover of the corresponding activator-substrate complexes must also increase to offset the low concentrations of the unstable complexes. To invoke such activation, one would have to provide a mechanism that explains why enzymatic reactivity of activator-substrate complexes would increase with decreasing stabilities of these complexes.

Although mechanisms involving the formation of activator-substrate complexes cannot be excluded based on these arguments, such mechanisms are less attractive than ones involving formation of activator-enzyme complexes, specifically those involving enzyme allostery (30). The minimal mechanism that can account for enzyme activity under allosteric control is shown in Fig. 2B (31). According to this mechanism, enzyme can bind either substrate S at its active site to form E-S or modulator X at an exosite to form X-E. These two species can then bind either S or X to form (X-E-S)′. In the course of these binding events, critical conformational isomerizations occur in the formation of (X-E-S)′. In this simple case, the equilibrium constants for these reversible conformational changes are equal to β. (X-E-S)′ turns over with a rate constant that differs from the rate constant for turnover of E-S by the factor γ.

Enzyme allostery explains our observations that both the mode of modulation (i.e. activation or inhibition) and the efficacy of modulation are dependent on structural features of the substrate. This follows from the key concept that modulation of enzyme activity via allosteric regulation is dependent on properties of (X-E-S)′ because it is the properties of this species that set the magnitudes of β and γ. There are of course other examples of enzyme allostery in which both the mode and the efficacy of modulation are dependent on substrate structure, including: chymotrypsin (32), 5-lipoxygenase (33), insulin-degrading enzyme (34, 35), and ribonucleotide reductase (36).

From the studies of this report, it appears that SIRT1-catalyzed deacetylation is accelerated by a STAC only when the peptide bears specific ring systems we have termed activation cofactors. It is unclear how activation cofactors facilitate the activity of STACs. In broad strokes, this must occur by enhancing the binding of activator to enzyme-substrate complexes or by promoting the conformational change that produces (X-E-S)′ or both. Any mechanistic proposal for SIRT1 activation by STACs would have to include provisions that allow the activation cofactor to reside at a number of positions relative to the acetylated Lys residue of substrates. One can speculate that in vivo, the activation cofactor might not reside on protein substrates but rather may be presented to SIRT1 during interaction with accessory proteins with which SIRT1 interacts.

Another in vivo consideration relates to the potency of STACs and whether it is sufficient to elicit the biological responses that are predicted for direct SIRT1 activation. Based on reports that a number of enzyme activators of similar potency (i.e. 2–4-fold activation at low micromolar concentrations) show biological activity (37), one could argue that the potency of STACs is, in fact, sufficient. However, this question can only be answered when STACs are tested in biological systems that have been shown to be dependent on the deacetylase activity of SIRT1. To date, a number of such studies have been published (11, 12, 17, 18, 38–42), demonstrating that these STACs have the potency to elicit SIRT1-dependent biological activities.

In summary, we have shown that SIRT1 activation by STACs occurs by a mechanism in which activator interacts directly with enzyme. Our results demonstrate the dependence of activation on substrate structure and are best explained by an allosteric mechanism in which specific features of the substrate facilitate activation by STACs.

Ten authors, with the exception of B. P. H., are employed by Sirtris, a GSK Company, which has a commercial interest in developing SIRT1 activators.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental experimental procedures and characterization data and Figs. S1 and S2.

In this study, we use the term STAC to refer specifically to the SIRT1-activating compounds that have been developed at Sirtris. Because these are all analogs of the original lead compound we identified, it is reasonable to assume that they all activate SIRT1 by the same basic mechanism. Thus, at least in broad strokes, conclusions drawn from the study of the 24 STACs reported herein should apply to all STACs.

It should be noted that because SIRT1 is a two-substrate reaction, the mechanisms of Fig. 2 are both oversimplifications of any activation mechanism that may operate for this enzyme. Thus, EC50 and RVmax are apparent values, functions not only of intrinsic values for that activator but also functions of the concentrations of the two substrates, the kinetic mechanism of SIRT1, and the rate and equilibrium constants associated with that mechanism for a particular substrate.

- AMC

- 7-amido-4-methyl coumarin

- SAR

- structure-activity relationship

- TAMRA

- tetramethyl-6-carboxyrhodamine

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sauve A. A., Celic I., Avalos J., Deng H., Boeke J. D., Schramm V. L. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 15456–15463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sauve A. A., Schramm V. L. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 9249–9256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sauve A. A., Wolberger C., Schramm V. L., Boeke J. D. (2006) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 435–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haigis M. C., Sinclair D. A. (2010) Annu. Rev. Pathol. 5, 253–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baur J. A. (2010) Mech. Ageing Dev. 131, 261–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guarente L. (2007) Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 72, 483–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutanen J., Yaluri N., Modi S., Pihlajamäki J., Vänttinen M., Itkonen P., Kainulainen S., Yamamoto H., Lagouge M., Sinclair D. A., Elliott P., Westphal C., Auwerx J., Laakso M. (2010) Diabetes 59, 829–835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milne J. C., Lambert P. D., Schenk S., Carney D. P., Smith J. J., Gagne D. J., Jin L., Boss O., Perni R. B., Vu C. B., Bemis J. E., Xie R., Disch J. S., Ng P. Y., Nunes J. J., Lynch A. V., Yang H., Galonek H., Israelian K., Choy W., Iffland A., Lavu S., Medvedik O., Sinclair D. A., Olefsky J. M., Jirousek M. R., Elliott P. J., Westphal C. H. (2007) Nature 450, 712–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bemis J. E., Vu C. B., Xie R., Nunes J. J., Ng P. Y., Disch J. S., Milne J. C., Carney D. P., Lynch A. V., Jin L., Smith J. J., Lavu S., Iffland A., Jirousek M. R., Perni R. B. (2009) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19, 2350–2353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vu C. B., Bemis J. E., Disch J. S., Ng P. Y., Nunes J. J., Milne J. C., Carney D. P., Lynch A. V., Smith J. J., Lavu S., Lambert P. D., Gagne D. J., Jirousek M. R., Schenk S., Olefsky J. M., Perni R. B. (2009) J. Med. Chem. 52, 1275–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feige J. N., Lagouge M., Canto C., Strehle A., Houten S. M., Milne J. C., Lambert P. D., Mataki C., Elliott P. J., Auwerx J. (2008) Cell Metab. 8, 347–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Funk J. A., Odejinmi S., Schnellmann R. G. (2010) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 333, 593–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin L., Galonek H., Israelian K., Choy W., Morrison M., Xia Y., Wang X., Xu Y., Yang Y., Smith J. J., Hoffmann E., Carney D. P., Perni R. B., Jirousek M. R., Bemis J. E., Milne J. C., Sinclair D. A., Westphal C. H. (2009) Protein Sci. 18, 514–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y., Dentin R., Chen D., Hedrick S., Ravnskjaer K., Schenk S., Milne J., Meyers D. J., Cole P., Yates J., 3rd, Olefsky J., Guarente L., Montminy M. (2008) Nature 456, 269–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith J. J., Kenney R. D., Gagne D. J., Frushour B. P., Ladd W., Galonek H. L., Israelian K., Song J., Razvadauskaite G., Lynch A. V., Carney D. P., Johnson R. J., Lavu S., Iffland A., Elliott P. J., Lambert P. D., Elliston K. O., Jirousek M. R., Milne J. C., Boss O. (2009) BMC Syst. Biol. 3, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamazaki Y., Usui I., Kanatani Y., Matsuya Y., Tsuneyama K., Fujisaka S., Bukhari A., Suzuki H., Senda S., Imanishi S., Hirata K., Ishiki M., Hayashi R., Urakaze M., Nemoto H., Kobayashi M., Tobe K. (2009) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 297, E1179–E1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshizaki T., Milne J. C., Imamura T., Schenk S., Sonoda N., Babendure J. L., Lu J. C., Smith J. J., Jirousek M. R., Olefsky J. M. (2009) Mol. Cell Biol. 29, 1363–1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howitz K. T., Bitterman K. J., Cohen H. Y., Lamming D. W., Lavu S., Wood J. G., Zipkin R. E., Chung P., Kisielewski A., Zhang L. L., Scherer B., Sinclair D. A. (2003) Nature 425, 191–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borra M. T., Smith B. C., Denu J. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17187–17195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaeberlein M., McDonagh T., Heltweg B., Hixon J., Westman E. A., Caldwell S. D., Napper A., Curtis R., DiStefano P. S., Fields S., Bedalov A., Kennedy B. K. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17038–17045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beher D., Wu J., Cumine S., Kim K. W., Lu S. C., Atangan L., Wang M. (2009) Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 74, 619–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pacholec M., Bleasdale J. E., Chrunyk B., Cunningham D., Flynn D., Garofalo R. S., Griffith D., Griffor M., Loulakis P., Pabst B., Qiu X., Stockman B., Thanabal V., Varghese A., Ward J., Withka J., Ahn K. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 8340–8351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith B. C., Hallows W. C., Denu J. M. (2009) Anal. Biochem. 394, 101–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nunes J. J., Milne J., Bemis J., Xie R., Vu C. B., Ng P. Y., Disch J. S., Salzmann T., Armistead D. (February15, 2007) World Intellectual Property Organization Patent WO 2007/019346 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bemis J., Disch J. S., Jirousek M., Lunsmann W. J., Ng P. Y., Vu C. B. (December24, 2008) World Intellectual Property Organization Patent WO 2008/156866 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vu C. B., Disch J. S., Ng P. Y., Blum C. A., Perni R. B. (January7, 2010) World Intellectual Property Organization Patent WO 2010/003048 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marcotte P. A., Richardson P. L., Guo J., Barrett L. W., Xu N., Gunasekera A., Glaser K. B. (2004) Anal. Biochem. 332, 90–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borra M. T., Langer M. R., Slama J. T., Denu J. M. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 9877–9887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haynes N. E., Corbett W. L., Bizzarro F. T., Guertin K. R., Hilliard D. W., Holland G. W., Kester R. F., Mahaney P. E., Qi L., Spence C. L., Tengi J., Dvorozniak M. T., Railkar A., Matschinsky F. M., Grippo J. F., Grimsby J., Sarabu R. (2010) J. Med. Chem. 53, 3618–3625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monod J., Changeux J. P., Jacob F. (1963) J. Mol. Biol. 6, 306–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segel I. H. (1975) in Enzyme Kinetics: Behavior and Analysis of Rapid Equilibrium and Steady-state Enzyme Systems, pp 227–241, John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erlanger B. F., Wassermann N. H., Cooper A. G., Monk R. J. (1976) Eur. J. Biochem. 61, 287–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aharony D., Stein R. L. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261, 11512–11519 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cabrol C., Huzarska M. A., Dinolfo C., Rodriguez M. C., Reinstatler L., Ni J., Yeh L. A., Cuny G. D., Stein R. L., Selkoe D. J., Leissring M. A. (2009) PLoS ONE 4, e5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song E. S., Juliano M. A., Juliano L., Fried M. G., Wagner S. L., Hersh L. B. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 54216–54220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eliasson R., Pontis E., Sun X., Reichard P. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 26052–26057 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zorn J. A., Wells J. A. (2010) Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 179–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boily G., He X. H., Pearce B., Jardine K., McBurney M. W. (2009) Oncogene 28, 2882–2893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He W., Wang Y., Zhang M. Z., You L., Davis L. S., Fan H., Yang H. C., Fogo A. B., Zent R., Harris R. C., Breyer M. D., Hao C. M. (2010) J. Clin. Invest. 120, 1056–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lagouge M., Argmann C., Gerhart-Hines Z., Meziane H., Lerin C., Daussin F., Messadeq N., Milne J., Lambert P., Elliott P., Geny B., Laakso M., Puigserver P., Auwerx J. (2006) Cell 127, 1109–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Picard F., Kurtev M., Chung N., Topark-Ngarm A., Senawong T., Machado De Oliveira R., Leid M., McBurney M. W., Guarente L. (2004) Nature 429, 771–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshizaki T., Schenk S., Imamura T., Babendure J. L., Sonoda N., Bae E. J., Oh D. Y., Lu M., Milne J. C., Westphal C., Bandyopadhyay G., Olefsky J. M. (2010) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 298, E419–E428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]