Abstract

Homeostatic regulation of NF-κB requires the continuous synthesis of IκBα and its rapid degradation by the proteasome through a ubiquitin-independent pathway. We previously showed that the ubiquitin-independent degradation signal of unbound IκBα was located in the C-terminal PEST region, and we have now identified a single tyrosine, Tyr-289, and determined that the hydrophobic character of the tyrosine is important for the rapid turnover of IκBα. The sequence composition of the PEST peptide surrounding this Tyr-289 imposes a distinct polyproline II conformation. Enhancing the polyproline II helix formation correlates with slower degradation rates of unbound IκBα. We have further identified a degradation signal located within the 5th ankyrin repeat that is functional once the C terminus is removed. Both the C-terminal and 5th ankyrin repeat degradation signals have inherent flexibility and specific hydrophobic residue(s), which together constitute the ubiquitin-independent degradation signal for IκBα.

Keywords: NF-kappa B, Proteasome, Protein Degradation, Protein Stability, Protein Structure

Introduction

Inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) proteins are the key regulators of NF-κB dimeric transcription factors (1–3). Three canonical IκB proteins (IκBα, -β, and ϵ) can inhibit NF-κB dimers from binding to their target DNA sequences, although IκBα is the most well studied NF-κB inhibitor. The primary structures of IκB proteins can be divided into three regions as follows: the N-terminal signal response domain, the central ankyrin repeat domain, and the C-terminal PEST domain. In the canonical signaling pathway, inhibition of NF-κB is relieved by signal-induced degradation of IκBα through phosphorylation of serines 32 and 36 in the signal response domain by IκB kinase leading to ubiquitination by ubiquitin (Ub)2 ligases and degradation of IκBα by the 26 S proteasome (1–3). Degradation of IκBα allows NF-κB to activate gene transcription by binding to specific DNA sequences in the promoters of many target genes, including that of the IκBα gene.

In addition to stimulus-dependent degradation of NF-κB-bound IκBα, recent reports have demonstrated the importance of synthesis and degradation of unbound IκBα to ensure NF-κB inhibition as well as to allow for rapid NF-κB activation upon stimulation (4–6). Whereas NF-κB-bound IκBα undergoes Ub-dependent degradation, IκBα not bound to NF-κB rapidly degrades without prior phosphorylation by IκB kinase nor ubiquitination (6). We have further shown that Ub-independent rapid degradation of unbound IκBα can be altered by deletion of the C-terminal 30 amino acids within the PEST domain of IκBα, and alteration of this degradation pathway has detrimental effects on NF-κB activation. The PEST domain of IκBα is also known to be constitutively phosphorylated by casein kinase 2 (CK2) at six threonines and serines, which has been implicated in the turnover of IκBα (7–10). The degradation of unbound IκBα can also be slowed by mutation of these phosphorylation sites to alanine (5, 6). These results are consistent with the PEST hypothesis, which suggests that proteins containing the amino acids (Pro), (Glu), (Ser), and (Thr) have higher turnover rates; however, the exact role of CK2 phosphorylation within this region remains unknown (11).

In vitro studies have revealed several interesting features of IκBα. IκBα contains six ankyrin repeats (AR), which are composed of a structural motif of ∼30 amino acids that fold into a helix-loop-helix followed by a β-hairpin extending from one repeat into the next. These repeats vary in sequence and hence flexibility (12, 13). The N-terminal four repeats fold independently of the C-terminal two repeats, which are weakly folded when IκBα is not bound to NF-κB, but they become well structured and much less dynamic when IκBα is bound to NF-κB (12, 14). The flexibility of the 5th and 6th repeats is essential for unbound IκBα degradation and tight NF-κB binding (13). However, it has not been shown whether any of these flexible ankyrin repeats can act as a degradation signal to promote degradation of IκBα. The N-terminal signal response domain and C-terminal PEST region are also highly solvent-accessible (15, 16).

Although the PEST region of IκBα is highly solvent-accessible and may not contain significant secondary structure (16), it is possible that this region is not a complete random coil. Various regions of proteins are known to be disordered or “flexible”; however, there may be some residual structure within these regions. For example, recent studies have demonstrated that a major conformation in unfolded peptides is a polyproline type II (PPII) helix (17). The structure of a PEST domain found in the E2 protein from papillomavirus has been studied using both CD and NMR and contains a PPII helix that is disrupted by phosphorylation and promotes degradation of E2 (18, 19).

This study investigates how structural features of IκBα, either inherent or introduced through point mutations, affect the ubiquitin-independent degradation of IκBα. We explored the contribution of hydrophobic residues within flexible regions toward proteasomal degradation. Results presented here show that truncations retaining highly solvent-accessible ankyrin repeats of IκBα promote rapid degradation, whereas truncations retaining only stably folded ankyrin repeats slow degradation significantly. Two regions which, once removed, slow degradation of unbound IκBα are the last 30 amino acids of the PEST region and the 5th AR. However, removal of the 5th AR internal degradation signal does not significantly affect Ub-independent degradation in the context of the full-length protein, suggesting that the C-terminal degradation signal located within the PEST region is more influential overall. In addition, we show that mutation of CK2 phosphorylation sites to alanine within the PEST domain alters the secondary structure of the PEST peptide. These mutations lead to a more stable PPII helix, which suggests that structural changes within the PEST domain can alter ubiquitin-independent degradation rates of IκBα. Finally, we show that hydrophobic residues within flexible and exposed regions promote degradation. Overall, we have correlated specific flexible regions to degradation of unbound IκBα and pinpointed a single tyrosine residue within the PEST region that controls unbound IκBα degradation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

Procedures followed in this study are very similar to the ones found in Ref. 6. Briefly, immortalized 3T3 cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% bovine calf serum and 100 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine. Cells treated with cycloheximide were used at 10 μg/ml resuspended in 50% EtOH (EMD Biosciences). For proteasome inhibition, 50 μm MG132 (Calbiochem) was used for various amounts of time. For virus production, 293T cells were transiently transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 with 8 μg of pBABE co-transfected with 3 μg of pCl-Eco (Imgenex), and cells were allowed to grow for 40–48 h. Filtered virus was placed onto target cells along with 8 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma). Infected cells were selected with 10 μg/ml puromycin (Calbiochem).

DNA Constructs

All IκBα constructs were cloned into the retrovirus vector pBabe-puro between the restriction sites EcoRI and SalI. Mutagenesis reactions were performed with the Stratagene QuikChange mutagenesis kit. ΔAR5 refers to the deletion of amino acids 207–243.

Western Blot Analysis

After treatment with cycloheximide, cells were lysed in a modified RIPA buffer. Approximately 50 μg of each cell extract was separated on a 12.5% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. IκBα was probed with either sc-371 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or sc-203 followed by anti-rabbit HRP conjugate. Quantification of Western blots was performed with ImageQuant TL (Amersham Biosciences), and quantification of EMSAs were performed with ImageJ.

CD Analysis

Peptides were purchased through GenScript, Inc., and resuspended in 10 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, ∼0.2 mg/ml. CD scans were performed on an Aviv 215 in a 1-mm cuvette from 260 to 180 nm. Three consecutive scans were performed at each temperature for each peptide and smoothed, and the base-line average was subtracted for the final CD trace.

RESULTS

Truncations of IκBα within Flexible Ankyrin Repeats Promote Rapid Degradation

It was previously shown that in the absence of NF-κB subunits, the unbound inhibitor protein IκBα degrades rapidly (4, 6, 20, 21). Although removal of the N-terminal domain (residues 1–67) does not affect rapid degradation, removal of the C terminus (residues 287–317) significantly reduced unbound IκBα degradation (6). However, this truncation did not remove all amino acids within the PEST domain, so, we set out to determine whether the deletion of the entire PEST region further stabilizes unbound IκBα. Using NF-κB-deficient cells (cells lacking the NF-κB subunits RelA, c-Rel, and p50, hereafter will be referred to as nfkb−/−), we expressed a truncated version of IκBα that removed the entire PEST domain (IκBαΔC281). All IκBs expressed in nfkb−/− are referred to as unbound IκBα. By treating cells with cycloheximide (CHX), an inhibitor of translation, the approximate half-life of unbound IκBα was determined. Unexpectedly, IκBαΔC281 slightly increased the degradation rate of IκBα as compared with IκBαΔC288 (Fig. 1B). To determine what further truncations would stabilize unbound IκBα, we created three more constructs, ΔC257, ΔC242, and ΔC207 (Fig. 1, A and C). ΔC257 removes the entire PEST domain as well as half of the 6th AR and has been shown to slow unbound IκBα degradation in vitro (22). ΔC242 removes entire 6th repeat and ends at the 5th AR of IκBα. Finally, ΔC207 removes all residues C-terminal to the 4th AR. Surprisingly, removal of residues N-terminal to the PEST domain (ΔC257 and ΔC242) enhanced the degradation rate of unbound IκBα as compared with IκBα ΔC288 (Fig. 1C). However, when both the 5th and 6th ARs of IκBα are entirely removed (IκBαΔC207), unbound IκBα is dramatically stabilized (Fig. 1C). It was earlier reported that the 5th and 6th repeats are inherently flexible (12). These results suggest that the seven-residue segment (281–287) might act as a cap for the last two repeats, i.e. removal of this peptide exposes the flexible 5th and 6th ARs.

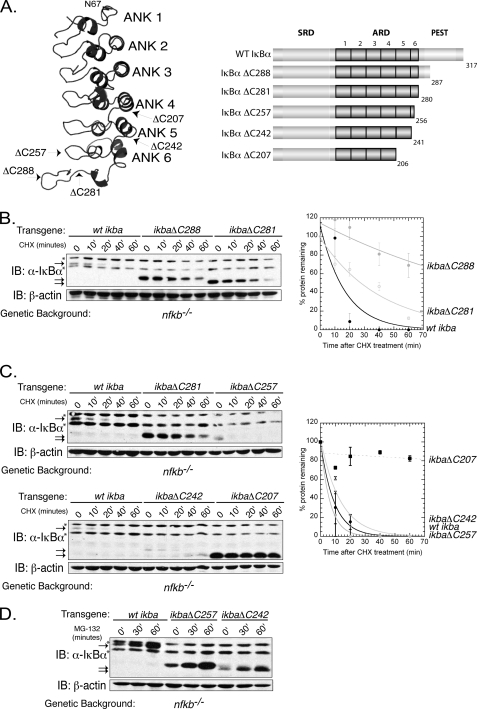

FIGURE 1.

Truncations in flexible regions of IκBα increase the rate of proteasome-mediated unbound IκBα degradation. A, left panel, structure of IκBα from the crystal structure bound to NF-κB (Protein Data Bank code 1IKN). Only IκBα is shown, with truncations and ankyrin (ANK) repeats indicated on the structure. Right panel, domain organizations of various truncations used in this study. ARD, ankyrin repeat domain; SRD, signal response domain. B, left panel, nfkb−/− cells expressing WT IκBα, IκBαΔC288, and IκBαΔC281 were treated with CHX and detected by Western blot using an antibody directed against the N terminus of IκBα. * indicates nonspecific bands associated with this antibody. Right panel, left panel quantitated, normalized to β-actin, and graphed. Error bars indicate S.E. from at least three experiments. ● represents WT IκBα; ○ represents IκBαΔC281, and gray circle represents IκBα ΔC288. IB, immunoblot. C, top left panel, nfkb−/− cells expressing WT IκBα, IκBαΔC281, and IκBαΔC257 were treated with CHX, and protein levels were detected by Western blot. Bottom left panel, nfkb−/− cells expressing WT IκBα, IκBαΔC242 and IκBαΔC207 were treated with CHX and protein levels detected by Western blot. Right panel, averages from at least two experiments were quantitated and graphed. Error bars indicate S.E. from at least two experiments. ■ represents IκBαΔC207; ● represents WT IκBα; gray circle represents IκBαΔC257, and (○) represents IκBαΔC242. D, nfkb−/− cells expressing WT IκBα, IκBαΔC257, or IκBαΔC242 were treated with MG132, a proteasomal inhibitor for the indicated periods of time. All IκBα protein levels increase, suggesting that the proteasome is involved in this degradation pathway.

To test whether the truncated forms of IκBα are degraded by the proteasome, the proteasome inhibitor MG132 was added to nfkb−/− cells expressing WT IκBα, IκBαΔC257, or IκBαΔC242. After addition of MG132 to these cell lines, the protein level increases over time; therefore, degradation of these proteins is mediated by the proteasome (Fig. 1D).

A Cluster of Hydrophobic Residues in the 5th Ankyrin Repeat Acts as a Degradation Signal

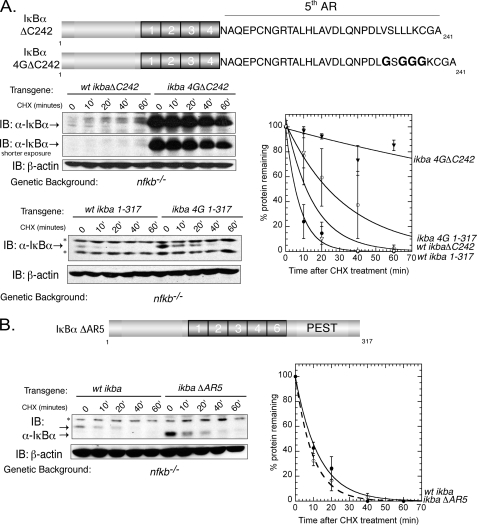

Because the IκBαΔC242 truncation degrades at a faster rate as compared with IκBαΔC207 (Fig. 1C), a degradation signal must exist in the flexible 5th AR. It has been shown that even in the presence of the 6th AR and a portion of the PEST domain, the 5th AR is very solvent-accessible compared with the 4th AR (12). The 5th AR also contains several hydrophobic residues, and it has been hypothesized that hydrophobic residues play a role in proteasomal recognition and activation (23–27). For instance, a 4-mer hydrophobic peptide can stimulate the gate opening of the α subunits of the 20 S proteasome, leading to the activation of the inner catalytic sites of the β subunits (23). Therefore, we mutated four residues (Val-233, Leu-235, Leu-236, and Leu-237), which are located in a C-terminal hydrophobic patch of IκBα in the 5th AR to glycine (Fig. 2A). We introduced this mutation (4G) into either full-length IκBα or IκBαΔC242. When 4G IκBαΔC242 was introduced into nfkb−/− cells, the degradation was significantly slowed compared with WT IκBαΔC242, suggesting that hydrophobic residues are important in proteasomal recognition and degradation through the flexible 5th AR (Fig. 2A, top panel). This is the first time that the requirement for both a flexible region and hydrophobic residues has been observed for IκBα. However, when the 4G mutation is introduced into full-length IκBα, only a small decrease in the degradation rate was observed (Fig. 2A, bottom panel). It is possible that the 5th AR is not completely exposed for proteasomal recognition within the context of the rest of the protein. Selective removal of the entire 5th AR shows a similar degradation rate as WT IκBα (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these observations suggest that the most dominant degradation signal in the full-length protein is located within the C-terminal 30 residues (residues 288–317) whereas the 5th AR provides a secondary degradation signal.

FIGURE 2.

Degradation in an IκBα truncation is influenced by hydrophobic residues. A, schematic detailing the location of the hydrophobic residues mutated to glycine (4G), either in the full-length or IκBαΔC242 background. Top left panel, nfkb−/− cells expressing WT IκBαΔC242 or IκBα4GΔC242 were treated with CHX, and degradation was observed by Western blot. Bottom left panel, nfkb−/− cells expressing WT IκBα(1–317) or IκBα4G(1–317) were treated with CHX, and degradation was detected by Western blot. * indicates nonspecific band associated with the antibody directed against the N terminus of IκBα. Right panel, quantification of left panels. ▿ represents WT IκBαΔC242; ▾ represents IκBα4GΔC242; ● represents WT IκBα(1–317), and ○ represents IκBα4G(1–317). Error bars indicate S.E. and are representative of at least two individual experiments. AR, ankyrin repeats; IB, immunoblot. B, removal of the 5th ankyrin repeat does not slow degradation of IκBα. Left panel, nfkb−/− cells expressing WT IκBα(1–317) or IκBαΔAR5 were treated with CHX and degradation was detected by Western blot. * indicates nonspecific band associated with the antibody directed against the N terminus of IκBα. Right panel, quantification of left panel. ● represents WT IκBα(1–317) and ○ represents IκBαΔAR5.

IκBα PEST Region Assumes Sequence-sensitive PPII Conformation

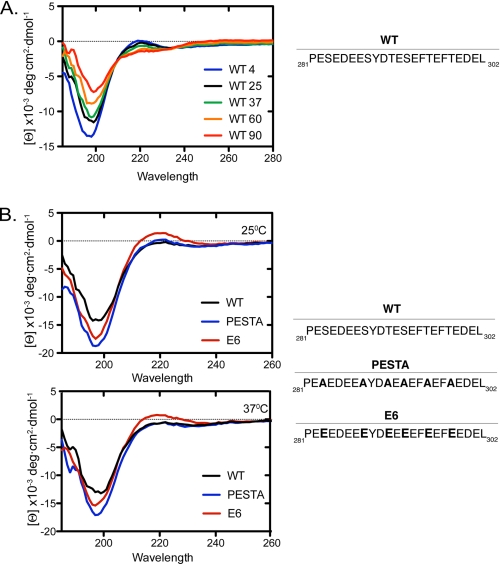

Because protein flexibility has shown to be important for degradation of IκBα, we decided to investigate whether the structure of the PEST region influences unbound IκBα degradation (13). CD was used to determine whether the PEST region has any residual structure. To this end, peptides containing residues 281–302 were synthesized. The WT PEST peptide has a PPII conformation, similar to that of another PEST peptide derived from the E2 protein of papillomavirus, with a negative band at 228 nm, a positive band at 218 nm, and a minimum at 198 nm (18). The molar ellipticity of the WT PEST peptide is altered upon temperature change suggesting structural transition from PPII to random coil (Fig. 3A). In all, these results suggest that the IκBα PEST sequence is not entirely unstructured but rather shows some degree of extended helical conformation. Peptides with PPII helical conformation remain solvent-exposed as no intramolecular hydrogen bonds are formed, consistent with previous reports (16).

FIGURE 3.

CD analysis of PEST peptides. A, far-UV scan of the PEST peptide of IκBα. The molar ellipticity of the WT peptide at 198 nm changes upon variation in temperature, suggesting that this peptide is not a random coil. Numbers indicate temperature in °C from 4 °C (blue trace) to 90 °C (red trace). Curves shown represent a smoothed average of three independent experiments with the base-line molar ellipticity subtracted. B, comparison of WT PEST peptide to the E6 and PESTA peptides at various temperatures.

Mutation of the CK2 phosphorylation sites in the PEST to alanine has been shown to slow degradation of unbound IκBα (5, 6). Although many studies suggest that CK2 phosphorylation affects IκBα degradation and NF-κB signaling, there are no insights as to whether structural changes within the PEST regions play a role in degradation rates (7–10). To investigate this possibility, we created a peptide with all serines and threonines that are potential CK2 phosphorylation sites mutated to alanine (PESTA). Although both the WT and PESTA peptides displayed characteristics of a polyproline type II helix, the PESTA peptide had a significantly lower minimum at 198 nm, suggesting that this mutant peptide adopts a PPII structure to a greater extent as compared with the WT PEST peptide (Fig. 3B). This enhancement of PPII helical conformation may not allow for efficient recognition by the proteasome, resulting in the stabilization of unbound IκBα. We have further tested another peptide where all CK2 sites are converted to glutamic acids (Glu-6) to mimic a phosphorylated PEST region. To our surprise, this mutant peptide had a higher propensity to form a PPII helix, similar to the PESTA peptide rather than disrupting the PPII helix. Although many studies show the involvement of CK2 in the degradation of IκBα independent of IκB kinase, it is possible that CK2 phosphorylation does not lead to the degradation of IκBα through structural changes. In addition the degradation kinetics of a CK2 phosphomimetic of IκBα has not been established in nfkb−/− cells. Moreover, UV-induced degradation of IκBα has been linked to an inhibition of translation, rather than direct CK2 phosphorylation. Taken together, of the mutants studied in this report, a correlation exists between PPII propensity and degradation kinetics.

Hydrophobic Residues in the PEST Sequence Influence the Half-life of IκBα

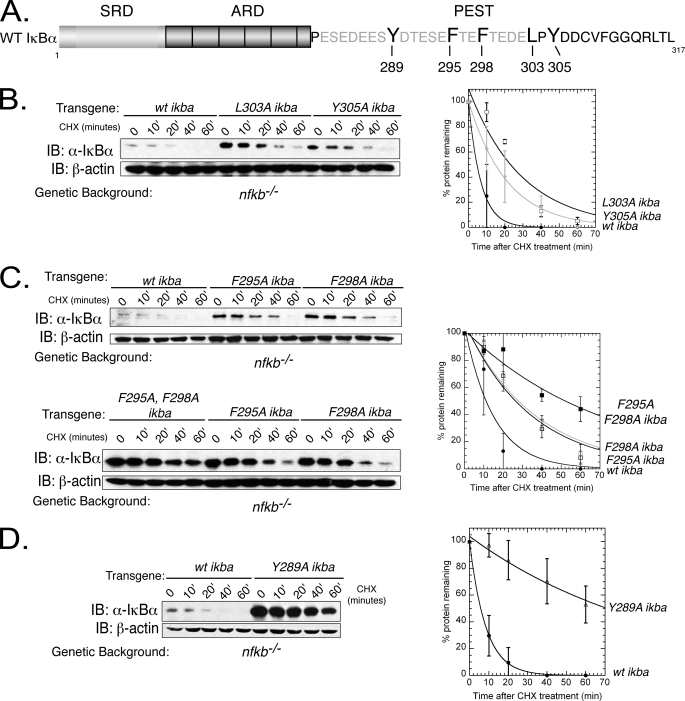

We wished to further dissect the degradation signal in the PEST sequence. The PEST sequence is almost exclusively negatively charged with a few hydrophobic residues within this highly negative stretch. These residues are Tyr-289, Phe-295, Phe-298, Leu-303, and Tyr-305. To determine whether these residues contribute to unbound IκBα degradation, they were mutated to alanine (Y289A, F295A, F298A, L303A, and Y305A). Because these residues are scattered throughout the PEST region, we examined the effect of these residues individually (Fig. 4A). All of the mutations increased the half-life of IκBα to varying degrees (Fig. 4, B–D). IκBαY305A slightly slowed the degradation of IκBα, as compared with WT IκBα (t½ ∼15 min; Fig. 4B). L303A had a moderate effect on unbound IκBα stabilization (t½ ∼30 min) (Fig. 4B). The F295A and F298A single mutations also had a moderate effect on IκBα degradation (t½ ∼30 min WT- Fig. 4C, top panel). The F295A,F298A double mutant was created due to the presence of an extra “EFT” insert in human IκBα as compared with other species that contain just one phenylalanine, so perhaps a combined mutation of both phenylalanines could have a more significant impact on degradation (Fig. 6A). Indeed, the double mutant enhanced the stability of IκBα (t½ = 40 min; Fig. 4C, bottom panel). The last mutant, Y289A, showed the most significant effect on IκBα stability (t½ = 60 min; Fig. 4D). These results clearly establish a role for the hydrophobic residues as a determinant of unbound IκBα stability. In addition, these results show that mutation of residues within the PEST region other than Pro, Glu, Ser, and Thr can contribute significantly to ubiquitin-independent degradation of IκBα.

FIGURE 4.

Mutations in PEST domain alter unbound IκBα degradation. A, top, schematic representing IκBα and the C-terminal PEST domain with residues that were mutated indicated in boldface. ARD, ankyrin repeat domain; SRD, signal response domain. B, left panel, transgenic nfkb−/−cells expressing either WT IκBα, L303A IκBα, or Tyr-305 IκBα were treated with CHX, and IκBα protein levels were detected by Western blot. IB, immunoblot. Right panel, left panel quantified, normalized with β-actin, and graphed as percentage of protein remaining with 0 min (0′) equal to 100% for each cell line. □, L303A IκBα; ●, WT IκBα; gray diamond, Y305A IκBα. C, top left panel, transgenic nfkb−/−cells expressing F295A IκBα, F298A IκBα, or the combined F295A,F298A IκBα mutants were treated with CHX, and degradation was detected through Western blot. Bottom left panel, transgenic cells expressing WT IκBα or F295A,F298A IκBα were treated with CHX and degradation monitored by Western blot. Right panel, quantification and graphic representation of averages from both top and bottom panels. ●, pale open square, □, and ■ denote WT IκBα, F295A IκBα, F298A IκBα, F295A,F298A IκBα, respectively. Error bars represent S.E. and are representative of at least two experiments. D, left panel, Western blot of CHX-treated nfkb−/− cells expressing WT IκBα or Y289A IκBα. Right panel, quantification and graphic representation of left panel. WT IκBα and Y289A IκBα are denoted by ● and Δ, respectively. Error bars represent S.E. and are representative of at least two experiments.

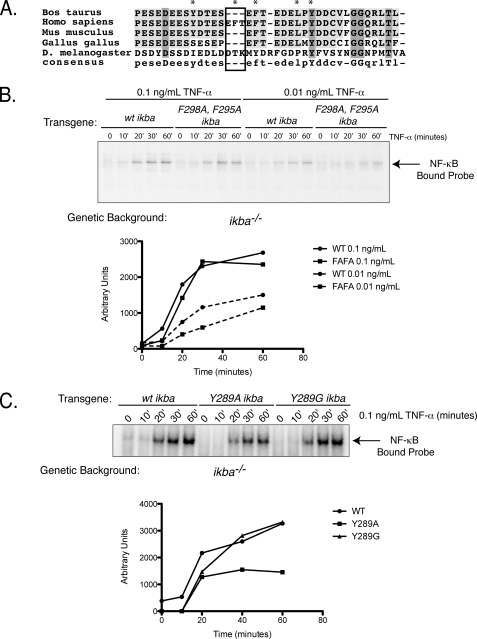

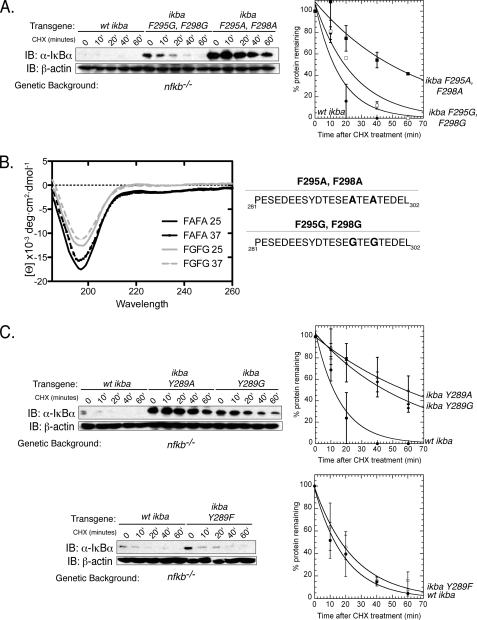

FIGURE 6.

Mutations within the PEST domain of IκBα affect NF-κB activation. A, sequences from Bos taurus, Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, Gallus gallus, and Drosophila melanogaster were aligned using ClustalW. Mutations made in this study are boxed and marked with an asterisk. Light gray shading indicates identical residues across several species, and dark gray shading indicates complete conservation. B, top panel, EMSA of IκBα−/− cells expressing F295A,F298A IκBα were stimulated with various concentrations of TNF-α, and NF-κB activation was observed. Bottom, quantification of top panel. C, top panel, IκBα−/− cells expressing Y289A or Y289G were stimulated with 0.1 ng/ml TNF-α, and NF-κB activation was observed. Solid lines indicate 0.1 ng/ml TNF-α, and dashed lines indicate 0.01 ng/ml TNF-α. Bottom panel, quantification of top panel. EMSAs shown here are representative of at least three experiments.

Structural Changes within the PEST Alters Degradation Rates

The hydrophobic residues in the PEST domain may control Ub-independent degradation rates in the following two ways: by influencing the secondary structure of the PEST peptide (similar to the PESTA mutant) or they could serve as a specific proteasome recognition signal. To ensure that the effect of mutating Phe-295 and Phe-298 to alanine is a specific rather than an indirect effect, these residues were also mutated to glycine. Surprisingly, the F295G,F298G double mutant did not have the same stabilization effect as the F295A,F298A double mutant (Fig. 5A). Therefore, these phenylalanines are most likely not involved in a specific interaction leading to proteasomal degradation. Mutation of Phe-295 and Phe-298 to alanine then could have an indirect effect such as introducing some structural stabilization. To determine whether there was a correlation between degradation rate and PPII propensity, we created PEST peptides containing the F295A, F298A and F295G,F298G double mutations. The peptide containing the F295A,F298A double mutation had more molar ellipticity than the F295G,F298G peptide, suggesting that the F295A,F298A peptide has more PPII propensity than the F295G,F298G peptide (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that the two phenylalanines (Phe-295 and Phe-298) are key to the maintenance of native structure of the PEST sequence but have no role in direct proteasome recognition.

FIGURE 5.

Tyr-289 is the key residue within the PEST domain that determines degradation rate of unbound IκBα. A, left panel, transgenic nfkb−/− cells expressing WT IκBα, F295G,F298G IκBα, or F295A,F298A IκBα were treated with CHX, and IκBα protein levels were detected by Western blot. Right panel, Western blot quantitated, normalized to β-actin levels, and graphed as a percentage of protein. IB, immunoblot. ● represents WT IκBα; ■ represents F295A,F298A IκBα, and □ represents F295G,F298G IκBα (B). CD analysis of both the F295A,F298A and F295G,F298G PEST peptides at both 25 and 37 °C. C, left panel, transgenic nfkb−/− cells expressing either WT IκBα, Y289A IκBα, or Y289G IκBα were treated with CHX. Right panel, average and S.E. of at least three experiments are quantitated and graphed. ● represents WT IκBα; Δ represents Y289A IκBα, and ♦ represents Y289G IκBα. Bottom panel, transgenic nfkb−/− cells expressing either WT IκBα or Y289F IκBα were treated with CHX. ● represents WT IκBα, and ○ represents Y289F IκBα.

However, unlike Phe-295 and Phe-298, mutation of tyrosine at 289 to glycine (Y289G) had the same stabilizing effect as the Y289A mutation. Therefore, Tyr-289 is directly involved in unbound IκBα degradation. It is possible that this tyrosine is modified, either through phosphorylation or nitrosylation. We eliminated any possibility of modification by mutating this Tyr-289 to Phe-289, to separate a potential modification from the inherent hydrophobic character of the residue (Fig. 5C). Our results clearly show that mutation of Tyr-289 to Phe-289 did not significantly change the degradation of unbound IκBα, suggesting that it is not a modification that controls degradation but rather the hydrophobic nature of Tyr-289.

Stable Free IκBα Alters NF-κB Function

Our hypothesis is that disruption of the free IκBα degradation pathway will affect NF-κB activation, as NF-κB released through degradation of bound IκBα may be bound by an abundance of stable free IκBα. To test this hypothesis, we investigated NF-κB activation by TNF-α in cells expressing three different mutants as follows: Y289A IκBα, Y289G IκBα, and F295A,F298A IκBα. IκBα−/− MEF cells were reconstituted with WT or mutant IκBα genes and were subjected to TNF-α treatment for different times. NF-κB activity was detected by EMSA. The F295A,F298A IκBα mutant showed a defect in NF-κB activation (Fig. 6B). Y298A IκBα mutant showed defects in both basal and induced activation (Fig. 6C). However, Y298G IκBα affected basal NF-κB binding, rather than activated NF-κB. It is unclear as to why Y289A IκBα and Y289G IκBα mutants behave differently. It is important to note that Tyr-289 is close to NF-κB in the IκBα-NF-κB complex, and therefore this residue may play a role in NF-κB binding. Therefore, in addition to degradation as a free protein, differential binding to NF-κB due to mutations may impact inducible NF-κB activity.

Moreover, slower degradation of these mutants is caused due to different reasons; the F295A,F298A double mutant is stabilized due to greater foldedness of the C-terminal degron as shown by CD. However, both the Y289G and Y289A mutants are not effectively degraded, suggesting that structural stability does not play a role in slowing the degradation of these mutants. Differential characteristics of these mutants may alter their degradation both in the free and bound states. Nevertheless, our results clearly show that stabilization of IκBα in its free state affects NF-κB activity both at homeostatic and inducible states.

DISCUSSION

Degradation Signals for IκBα Are Found within Flexible Regions

This study defines and characterizes two ubiquitin-independent degradation signals for unbound IκBα, in addition to the well known signal and ubiquitin-dependent degradation for bound IκBα. Interestingly, all of these degradation signals are in the flexible regions, whether the degradation pathway is ubiquitin-dependent or ubiquitin-independent (12, 15, 16). This is consistent with reports that the proteasome requires a degradation signal as well as an extended peptide (28). In addition, the correlation between classic degradation motifs such as the PEST region, destruction-box, KEN-box, or the N-terminal residue and the half-life of the protein is weak. Instead, a stronger correlation is found between the amount of disorder in a protein and its half-life (29). For ubiquitin-independent degradation of IκBα, the primary degradation signal is located within the solvent-accessible C terminus where mutation of a single residue, Tyr-289, can significantly alter the degradation rate of unbound IκBα. We have further shown that in the absence of the primary degradation signal, the 5th AR can also promote degradation of IκBα, which we refer to as the secondary degradation signal. This secondary degradation signal can be in three possible structural states with distinct functional consequences. First, in an IκB-NF-κB complex, the 5th AR is structured, which precludes proteasomal recognition. Second, in a full-length unbound IκBα protein, the 5th AR is partly unfolded with intact secondary structures. Third, in an unbound IκBα protein where the C-terminal PEST is truncated. In the last case, the 5th AR is mostly or fully unstructured such that it is recognized by the proteasome. NMR and H/D exchange studies have clearly demonstrated the structural differences of full-length IκBα in bound and unbound states (12, 30). Although there is no direct experimental proof that the 5th AR is more flexible in a PEST-deleted mutant than in the context of full-length IκBα, the faster degradation rate of IκBαΔ242 as compared with IκBαΔ288 suggests that within the IκBαΔ242 truncation, the 5th repeat may promote proteasomal recognition and rapid degradation. We suspect that the greater flexibility is responsible for this function. It is likely that the segment encompassing residues 281–287 acts as a “cap” allowing retention of residual structures for the last two ARs. Altogether, these observations suggest that the difference in flexibility/foldedness is an important regulator of Ub-independent degradation by altering the status of the degradation signal.

Because the inherent degradation signals are found in flexible regions, there may be modifications that also alter secondary structure and therefore degradation. In this study, we have analyzed the secondary structure of the PEST region of IκBα through CD to test this hypothesis. Our results clearly showed a significant difference between the secondary structures of the WT PEST peptide and the PESTA peptide, where all possible CK2 phosphorylation sites were mutated to alanine. We also found that phosphorylation mimetic peptide E6 behaved similarly to the PESTA peptide. Our result is inconsistent with observation made with papillomavirus E2. Studies on the E2 protein of papillomavirus showed that a phosphorylated PEST peptide has less PPII structure than the unmodified peptide; this difference in structure correlates to a difference in degradation rates (18, 19). It is possible that structural propensity of IκBα and E2 PEST sequences are different due to their differential sequence compositions. Therefore, it is not a global phenomenon where phosphorylation of the PEST domain leads to an unstructured region.

It has been shown that that CK2 phosphorylation of IκBα induces NF-κB activation after exposure to UV radiation (7). However, the mechanism of UV-induced activation of NF-κB has remained a controversial issue. Our results suggest that CK2 phosphorylation of the PEST sequence may not induce free IκBα degradation and that NF-κB activation by UV is the result of inhibition of translation through phosphorylation of translation initiation factor eIF2a. Finally, a structural change determined by CD also explains the large difference in degradation rates that we observe between the F295A,F298A and F295G,F298G double mutants of IκBα. In all, modulation of degradation through apparent structural variations of the PEST degradation signals allows us to suggest a correlation between Ub-independent proteasomal degradation and structural flexibility.

Hydrophobic Residues Promote Degradation of IκBα

Although flexibility is necessary for degradation of IκBα, hydrophobic residues also play a role in determining the degradation rate. We find that a single residue, Tyr-289, is a key residue within the C-terminal PEST degradation signal, although the precise mechanism of its involvement in proteasomal recognition is still unclear. In addition, the degradation signal within the 5th AR also contains hydrophobic residues. Interestingly, the flexible N terminus (residues 1–67) also contains several hydrophobic residues but is not considered a degradation signal, as removal of this region does not slow unbound IκBα degradation. It is likely that hydrophobic residues must be present in a proper sequence context to be able to serve as degradation signals. The significance of hydrophobic residues in Ub-independent protein degradation has been shown in other protein systems. For instance, 20 S proteasome activity is stimulated when incubated with peptides containing a 4-mer hydrophobic motif (23). In addition, it has been shown that proteasomal degradation of proteins such as Huntington protein (Htt), androgen receptor (AR), SGK-1 and MATα-2 is also determined by hydrophobic motifs (24–26). Finally, exposure of hydrophobic residues in mildly oxidized proteins has been shown to increase proteasomal activity (27). Future studies are required to determine what proteasomal chaperone is required for ubiquitin-independent IκBα degradation, and how Y289 plays a role in this recognition.

Requirement for Multiple Degradation Signals for IκBα

This study demonstrates that IκBα contains more than one degradation signal that can lead to its ubiquitin-independent degradation. Why would IκBα contain these various degradation signals? There are two aspects that can be highlighted in this context. First, although there was only a small (1.5-fold) decrease in degradation rate when the 4G mutations were introduced in the full-length protein, this small change in degradation rate may have a large impact in NF-κB signaling. We cannot rule out the possibility that the 6th repeat also contains a degradation signal, and disruption of both the 5th and 6th repeats may have a much more detrimental effect on free IκBα degradation.

The second possibility is that the secondary degradation signal(s) is essential for complete fragmentation of IκBα by the proteasome. This is particularly relevant because the first four ARs are so stable the PEST degradation signal alone might be unable to fragment the entire protein. Once the C terminus is removed, the presence of the 5th AR can support degradation of the entire protein, as perhaps the PEST region is not strong enough on its own to promote degradation of the entire protein. Presence of stable IκBα fragments may be detrimental to cell physiology.

Free IκBα Pool Regulates NF-κB Activity

Mathematical modeling showed that NF-κB activity is sensitive to the levels of free IκBα pool. It was shown that NF-κB activation was dramatically enhanced when cells were co-stimulated with two inducers, such as UV and LPS, compared with their independent activation potential (5). UV induced the reduction of the free IκBα pool by blocking new IκBα synthesis, whereas LPS induced bound IκBα degradation. These observations were an experimental validation of a model that predicted that even a small decline of the free IκBα pool would significantly impact NF-κB activation by a second signal that degrades bound IκBα through IκB kinase and the Ub conjugation pathway. Although physiological signals that target free IκBα have not been identified, the significance of the free IκBα pool in NF-κB regulation is clear.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sulakshana Mukjeree, Kendra Hailey, and Joseph Taulan for helpful discussions and technical advice and Ellen O'Dea and Alexander Hoffmann for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Award T32 CA009523, Ruth L. Kirschstein award from NRSA (to E. M.), and Grant 5P01GM071862-04 (to G. G.).

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- CHX

- cycloheximide

- AR

- ankyrin repeat

- PPII

- polyproline type II.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karin M., Ben-Neriah Y. (2000) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 621–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin A. S., Jr. (1996) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 14, 649–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh S., May M. J., Kopp E. B. (1998) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16, 225–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Dea E. L., Barken D., Peralta R. Q., Tran K. T., Werner S. L., Kearns J. D., Levchenko A., Hoffmann A. (2007) Mol. Syst. Biol. 3, 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Dea E. L., Kearns J. D., Hoffmann A. (2008) Mol. Cell 30, 632–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathes E., O'Dea E. L., Hoffmann A., Ghosh G. (2008) EMBO J. 27, 1357–1367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kato T., Jr., Delhase M., Hoffmann A., Karin M. (2003) Mol. Cell 12, 829–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin R., Beauparlant P., Makris C., Meloche S., Hiscott J. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 1401–1409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McElhinny J. A., Trushin S. A., Bren G. D., Chester N., Paya C. V. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 899–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarz E. M., Van Antwerp D., Verma I. M. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 3554–3559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers S., Wells R., Rechsteiner M. (1986) Science 234, 364–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Truhlar S. M., Torpey J. W., Komives E. A. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 18951–18956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Truhlar S. M., Mathes E., Cervantes C. F., Ghosh G., Komives E. A. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 380, 67–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferreiro D. U., Cervantes C. F., Truhlar S. M., Cho S. S., Wolynes P. G., Komives E. A. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 365, 1201–1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobs M. D., Harrison S. C. (1998) Cell 95, 749–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Croy C. H., Bergqvist S., Huxford T., Ghosh G., Komives E. A. (2004) Protein Sci. 13, 1767–1777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi Z., Woody R. W., Kallenbach N. R. (2002) Adv. Protein Chem. 62, 163–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.García-Alai M. M., Gallo M., Salame M., Wetzler D. E., McBride A. A., Paci M., Cicero D. O., de Prat-Gay G. (2006) Structure 14, 309–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penrose K. J., Garcia-Alai M., de Prat-Gay G., McBride A. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 22430–22439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rice N. R., Ernst M. K. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 4685–4695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pando M. P., Verma I. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 21278–21286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroll M., Conconi M., Desterro M. J., Marin A., Thomas D., Friguet B., Hay R. T., Virelizier J. L., Arenzana-Seisdedos F., Rodriguez M. S. (1997) Oncogene 15, 1841–1850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kisselev A. F., Kaganovich D., Goldberg A. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 22260–22270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandra S., Shao J., Li J. X., Li M., Longo F. M., Diamond M. I. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 23950–23955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bogusz A. M., Brickley D. R., Pew T., Conzen S. D. (2006) FEBS J. 273, 2913–2928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson P. R., Swanson R., Rakhilina L., Hochstrasser M. (1998) Cell 94, 217–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shringarpure R., Davies K. J. (2002) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 32, 1084–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeuchi J., Chen H., Coffino P. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 123–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tompa P., Prilusky J., Silman I., Sussman J. L. (2008) Proteins 71, 903–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sue S. C., Cervantes C., Komives E. A., Dyson H. J. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 380, 917–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]