Abstract

Formation of centromeric heterochromatin in fission yeast requires the combined action of chromatin modifying enzymes and small RNAs derived from centromeric transcripts. Positive feedback mechanisms that link the RNAi pathway and the Clr4/Suv39h1 histone H3K9 methyltransferase complex (Clr-C) result in requirements for H3K9 methylation for full siRNA production and for siRNA production to achieve full histone methylation. Nonetheless, it has been proposed that the Argonaute protein, Ago1, is the key initial trigger for heterochromatin assembly via its association with Dicer-independent “priRNAs.” The RITS complex physically links Ago1 and the H3-K9me binding protein Chp1. Here we exploit an assay for heterochromatin assembly in which loss of silencing by deletion of RNAi or Clr-C components can be reversed by re-introduction of the deleted gene. We showed previously that a mutant version of the RITS complex (Tas3WG) that biochemically separates Ago1 from Chp1 and Tas3 proteins permits maintenance of heterochromatin, but prevents its formation when Clr4 is removed and re-introduced. Here we show that the block occurs with mutants in Clr-C, but not mutants in the RNAi pathway. Thus, Clr-C components, but not RNAi factors, play a more critical role in assembly when the integrity of RITS is disrupted. Consistent with previous reports, cells lacking Clr-C components completely lack H3K9me2 on centromeric DNA repeats, whereas RNAi pathway mutants accumulate low levels of H3K9me2. Further supporting the existence of RNAi–independent mechanisms for establishment of centromeric heterochromatin, overexpression of clr4+ in clr4Δago1Δ cells results in some de novo H3K9me2 accumulation at centromeres. These findings and our observation that ago1Δ and dcr1Δ mutants display indistinguishable low levels of H3K9me2 (in contrast to a previous report) challenge the model that priRNAs trigger heterochromatin formation. Instead, our results indicate that RNAi cooperates with RNAi–independent factors in the assembly of heterochromatin.

Author Summary

Centromeres are the chromosomal regions that promote chromosome movement during cell division. They consist of repetitive DNA sequences that are packaged into heterochromatin. Disruption of centromeric heterochromatin leads to chromosome loss that can result in miscarriages and genetic disorders. We have sought to define the precise steps leading to heterochromatin assembly using fission yeast as the model system. To accomplish this we employed our novel Tas3WG mutant strain that can propagate preassembled heterochromatin but cannot support its de novo establishment. Current models suggest that small RNAs initiate heterochromatin assembly by targeting the RNAi machinery and subsequently the Clr-C chromatin-modifying complex to the centromere. Here, we demonstrate that transient depletion of components of the RNAi pathway that generate or bind small RNAs does not perturb heterochromatin assembly in our Tas3WG strain. Instead, transient depletion of the Clr-C complex blocks heterochromatin assembly, suggesting a critical role for continuous Clr-C activity during heterochromatin assembly in Tas3WG cells. We have directly tested whether Clr-C can target centromeres when expressed in cells deficient for RNAi and Clr-C. We find that RNAi–independent recruitment of Clr-C can occur and likely contributes to the critical initiating mechanisms of heterochromatin assembly.

Introduction

Eukaryotic genomes are characterized by domains of transcriptionally permissive euchromatin and relatively transcriptionally inert heterochromatin. In addition to its important role in transcriptional regulation, heterochromatin plays a critical role in the regulation of genomic stability. In fission yeast constitutive heterochromatin assembles at the centromeres, telomeres and the mating type locus. This heterochromatin is required for high fidelity chromosome transmission, protecting chromosome ends from fusion to form dicentric chromosomes, and preventing co-expression of both sets of mating type information which could lead to haploid meiosis and cell death.

A major hallmark of heterochromatin in most eukaryotes is the presence of methyl groups on lysine 9 of histone H3. In fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe), methylation of H3 K9 is carried out by a single enzyme, Clr4 (the homolog of Suvar39 enzymes in higher eukaryotes), which is responsible for mono, di and tri-methylation of H3K9 [1]. This mark is in turn bound by proteins bearing a chromodomain, including the HP1 homologs Swi6 and Chp2, and importantly, Clr4 itself, leading to models for perpetuation and spreading of heterochromatin [2]–[5]. A fourth chromodomain protein, Chp1, has high affinity for binding the methyl mark [6]. Chp1 is a component of the RITS complex (RNA-induced initiation of transcriptional silencing complex), which is critical for the accumulation of heterochromatin at centromeres [7], [8].

Heterochromatin assembly in several organisms also depends upon the cellular RNA interference (RNAi) pathway [9]. RNAi is triggered by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), which is processed by the RNAseIII-like activity of Dicer into short interfering (si) RNAs. siRNAs are loaded into RNA –induced silencing complexes (RISC), where they associate with Argonaute proteins, and base-pair with and promote the sequence-dependent destruction of RNA via cleavage mediated by Argonaute. In fission yeast, the RNAi effector complex is called RITS, and consists of the sole argonaute protein, Ago1, in complex with Tas3 which physically links Ago1 to Chp1 [8], [10]. Association of the RITS complex with centromeres is co-dependent on the RNA dependent RNA polymerase complex, RDRC [11]. RITS and RDRC physically associate with the Clr4-containing Clr-C complex [5], [12], and trigger an RNAi-mediated positive feedback loop to enhance H3K9me2 accumulation and heterochromatin assembly [13]. Accumulation of H3K9me2 allows recruitment of heterochromatin- binding proteins such as Swi6 (the fission yeast homolog of HP1) and cohesin to centromeric repeats, and is required for efficient chromosome segregation (reviewed in [14]). Clearly, the mechanism by which RITS and RDRC are initially recruited to centromeres to promote RNAi-dependent accumulation of H3K9me2 is critical to our understanding of heterochromatin assembly.

Somewhat paradoxically, the outer repeats of the centromere are transcribed by RNA polymerase II, and this transcription correlates with heterochromatin assembly [15]–[18]. Recently, two models have been proposed for how centromeric transcripts may initiate recruitment of RITS/RDRC. The first proposes that single stranded centromeric transcripts fold into hairpin structures to provide dsRNA template for the activity of dicer (Dcr1) to generate centromeric siRNAs to target RITS to homologous centromeric sequences [19]. Alternatively, RNA degradation products (priRNAs) associate with Ago1, and if derived from centromeric transcripts, target Ago1 to centromeres [20]. Ago1 slices transcripts that are homologous to priRNAs, recruiting RDRC which promotes dsRNA synthesis. dsRNAs are cleaved by Dcr1 to form centromeric siRNAs that recruit RITS to centromeres [8]. In both models, centromeric RITS/RDRC then promotes Clr-C association, and H3K9 methylation facilitating binding of Chp1 to chromatin.

These models infer that small RNAs and the RNAi pathway act as the priming signal for heterochromatin assembly, with Dcr1 or Ago1 playing the initiating role respectively. However, RITS possesses two potential centromeric targeting motifs: Ago1 which binds siRNAs and can target centromeric transcripts and Chp1 which has high affinity for binding H3K9me2 [6], [7]. We questioned whether indeed RNAi is the upstream event for heterochromatin assembly, or whether Clr4 functions upstream of RNAi to generate H3K9me2 to recruit RITS.

Dissection of the requirements for the initial assembly of centromeric heterochromatin is greatly hampered by the inter-relatedness of the RNAi and chromatin modifying pathways and the positive feedback loops involved in full heterochromatin assembly. Deletion of genes required for assembly of heterochromatin ablates heterochromatin, complicating analysis of whether the gene contributes to the establishment or maintenance of heterochromatin. To define the contribution of siRNAs and H3K9me to targeting RITS to centromeres, we have generated mutants that separate Ago1 from the RITS complex [10], that remove Chp1 from the RITS complex [21], and mutations within the chromodomain of Chp1 [6], [22] that weaken the high affinity of Chp1's chromodomain for binding H3K9me2/3. Data accumulated from analysis of these mutants strongly supports that centromeric targeting of RITS critically depends on Chp1 and in particular, Chp1 chromodomain's high affinity for binding H3K9me2/3.

The tas3WG mutant separates Ago1 from Tas3-Chp1 [10]. This mutant bears a two amino acid alanine substitution of residues W265 and G266 within the conserved WG/GW Ago “hook” (or interaction domain) of Tas3 [10], [23], that renders the Chp1-Tas3 subcomplex incapable of associating with Ago1. Surprisingly, tas3WG cells can maintain preassembled heterochromatin, most likely via retention of the subcomplexes of RITS at centromeres because of Chp1-Tas3 association with H3K9me2 and Ago1's association with centromeric siRNAs [10]. Interestingly, following removal of all H3K9me2 and loss of heterochromatin –dependent siRNAs (in clr4Δ backgrounds), tas3WG cells fail to generate de-novo heterochromatin on reintegration of clr4+ [10]. We reasoned that genes that are particularly important for the establishment of heterochromatin would likewise be defective for heterochromatin assembly if transiently depleted in the tas3WG background. In contrast, genes with a less critical role for heterochromatin assembly might be expected to assemble heterochromatin efficiently if transiently depleted in tas3WG cells.

Here, we directly test the contribution of proteins involved in the RNAi pathway or in methylation of H3K9 to the initiation of centromeric heterochromatin. We find that transient depletion of any Clr-C component perturbs the establishment of heterochromatin in tas3WG cells. In contrast, transient depletion of genes involved in the RNAi pathway does not block heterochromatin assembly in tas3WG cells. Thus there appears to be a continuous requirement for the Clr-C complex, but not RNAi, during heterochromatin assembly in cells bearing a disrupted RITS complex. Consistent with this, RNAi-defective cells retain low levels of the heterochromatin mark, H3K9me2, whereas this mark is completely absent from Clr-C mutant cells. Because RNAi-defective cells maintain residual H3K9me2, it is not heterochromatin initiation which is being monitored following reintroduction of RNAi components, but more downstream aspects of heterochromatin assembly. To determine if RNAi is required for the initial step in heterochromatin assembly, we additionally removed H3K9me2 from RNAi defective cells by making compound mutants with clr4Δ, and interrogated whether on re-expression of clr4+, Clr-C could target centromeric sequences. We found that Clr4 can promote de novo methylation of centromeric repeats when overexpressed in cells otherwise lacking Clr4 and either of the RNAi components Ago1 or Dcr1. Thus, Clr-C can target H3K9me2 to centromeric repeats independently of the RNAi pathway. This data, plus our finding that ago1-deficient cells retain significant levels of H3K9me2 on centromeric repeats shows that Ago1 and Ago1 bound priRNAs are not necessary for the initiation of assembly of centromeric heterochromatin. Instead, our data strongly indicates that RNAi-independent mechanisms function together with RNAi in the cooperative assembly of centromeric heterochromatin.

Results

Transient depletion of rik1+ causes defective heterochromatin establishment in tas3WG cells

To precisely define the point of action of regulators of heterochromatin assembly, we have employed the tas3WG allele which disrupts the RITS complex. Transient gene depletion experiments in tas3WG cells previously showed that the H3K9 methyltransferase, Clr4, is required to establish centromeric heterochromatin when Ago1 is separated from Chp1-Tas3 [10]. Clr4 is a component of a large complex of proteins called Clr-C. Cells lacking Clr-C components lose centromeric heterochromatin [24]–[29], but the role of individual Clr-C components in heterochromatin assembly is poorly understood. We therefore assessed the point of action of Clr-C components in heterochromatin establishment, using transient gene depletion experiments in the tas3WG background.

Rik1 was the first protein identified in complex with Clr4 [30], and it resembles the UV DNA damage binding protein, UV-DDB1, including homology to the CPSF-A factor involved in RNA processing [31]. Rik1 is thought to act upstream of Clr4, and to help recruit Clr-C to chromatin, since Rik1 remains localized at centromeres in mutants that mislocalize Clr4 [5], [28]. We tested whether transient depletion of rik1 + in tas3WG cells would prevent assembly of heterochromatin. We introduced the tas3WG-TAP and tas3-TAP alleles into a rik1Δ strain that carries a ura4 + transgene within the outer repeats of centromere 1 (cen::ura4 +). Wild type cells efficiently assemble heterochromatin on cen::ura4 +, silencing its expression, and allowing growth on media containing the drug 5-FOA, which is toxic to cells that express ura4+. Cells lacking rik1+ fail to silence the centromeric transgene. The re-establishment of centromeric heterochromatin was monitored following reintroduction of rik1+ into its normal genomic locus. Addition of rik1+ to rik1Δ tas3-TAP cells allowed efficient establishment of heterochromatin and silencing of the cen::ura4+ transgene (Figure 1B). In contrast, on reintroduction of rik1+ into tas3WG-TAP cells, heterochromatin did not reassemble to silence the cen::ura4+ reporter.

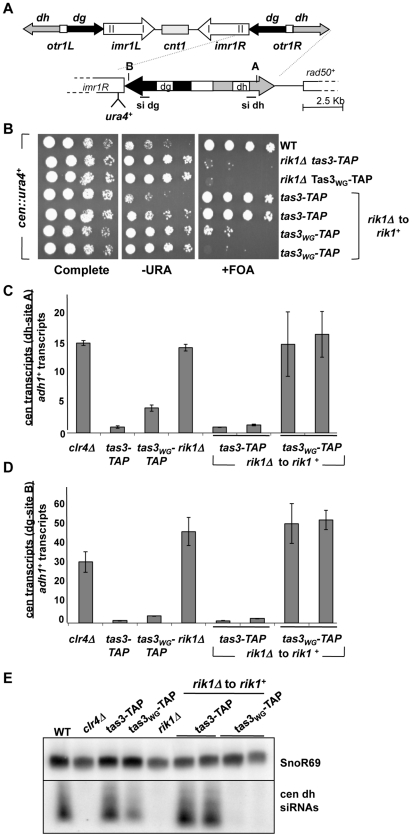

Figure 1. Clr-C component rik1+ is required for establishment of repressive chromatin at the centromere.

A. Cartoon representing the dg and dh repeat structure within the outer repetitive sequences (otr) at centromere 1. In the cen::ura4+ strain, the ura4+ marker gene is located within dg. A and B represent PCR fragments for real-time PCR analyses from dh and dg respectively, and probes used for siRNA detection are also represented. B. Serial dilution assay of yeast bearing the cen::ura4+ marker plated onto complete synthetic media (PMG complete), media lacking uracil (−URA), or complete media supplemented with 5-fluoro-orotic acid (+FOA). In the last 4 rows, the rik1+ gene has been reintegrated into the rik1Δ locus (rik1Δ to rik1+). Strains analyzed: PY2036, 3776, 3778, 4879, 4880, 4881, 4882. C. Real time PCR analysis of centromeric transcripts from the dh repeats (site A), relative to the adh1+ euchromatic control in cDNA from indicated strains. Duplicate experiments used independent RNA samples, and data represents the mean ± SEM. All values were normalized to the value obtained for a wild type cen::ura4+ strain (PY2036). Strains used: PY 2036, 1838, 3494, 3497, 3776, 4879, 4880, 4881, 4882. D. Real time PCR analysis performed as described for (C), but measuring the transcript accumulation from the dg repeats (site B) relative to adh1+. E. Northern blot of small RNA populations isolated from indicated strains, hybridized with probes for siRNAs derived from the dh repeat, or SnoR69 RNA as loading control. Strains used as in (C).

Transcription of endogenous dg and dh centromeric repeats was measured by real time PCR in cDNA prepared from these strains. In wild type cells, centromeric transcripts are processed by siRNA-dependent Ago1-mediated processing and by RNAi-independent turnover [32]–[34]. In addition, heterochromatin that assembles on repeat sequences can reduce access of RNA polymerase, thus preventing transcript accumulation [35]. Centromeric transcripts from dh (Figure 1C) and dg (Figure 1D) accumulate in cells lacking rik1+, similar to cells lacking clr4+. On reintegration of rik1+ into tas3-TAP cells, centromeric transcripts become normally processed, resulting in no net gain in transcript levels in rik1Δ to rik1+ tas3-TAP cells relative to tas3-TAP cells. Strikingly, both dg and dh transcript levels remain high in tas3WG cells following reintegration of rik1+, consistent with the observed silencing defect of the cen::ura4+ reporter in these strains. This accumulation of transcripts is at least in part due to defective processing of centromeric transcripts into siRNAs by the RNAi machinery since siRNAs were not detectable by Northern blotting in tas3WG-TAP rik1Δ to rik1+ cells whereas rik1+ reconstituted tas3-TAP cells synthesized centromeric siRNAs as efficiently as tas3-TAP cells (Figure 1E).

Transient depletion of Raf1 or Raf2 in tas3WG cells causes defective heterochromatin assembly

Raf1 (Cmc1, Dos1, Clr8) and Raf2 (Cmc2, Dos2, Clr7) have also been identified as components of Clr-C [27], [29]. They are required for localization of Swi6 [25], and are important for silencing the mating type locus [26]. raf1+ encodes a WD repeat protein which can bind Rik1 [25], and raf2+ encodes a putative Zn finger protein which binds to Pcu4 [26].

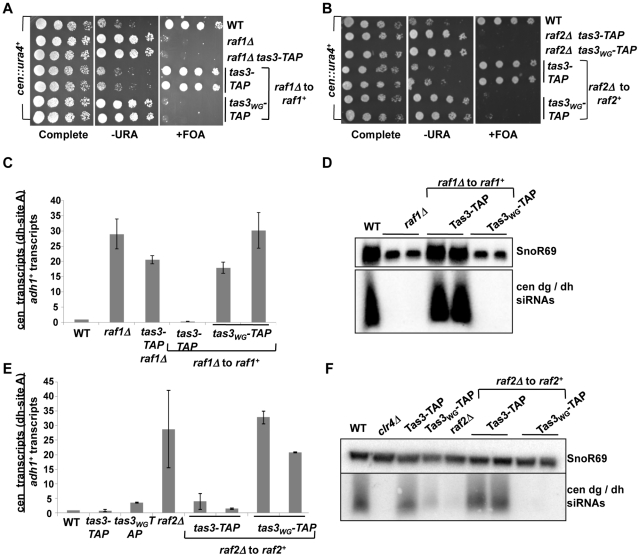

raf1Δ and raf2Δ were crossed into tas3-TAP and tas3WG -TAP backgrounds, and wild type genomic copies of raf1+ or raf2+ were reintegrated into the corresponding deletion mutants and assessed for heterochromatin assembly. As seen for transient depletion experiments with rik1, tas3-TAP cells efficiently re-assembled centromeric heterochromatin on reintroduction of raf1+ or raf2+, whereas silencing of the cen::ura4+ reporter was not apparent in tas3WG-TAP backgrounds (Figure 2A and 2B). Centromeric transcripts accumulate to high levels in raf1 and raf2 deleted cells, and although transcript levels drop following reintegration of raf1 + into raf1Δ tas3-TAP cells or of raf2 + into raf2Δ tas3-TAP cells, high levels of dg and dh transcripts are maintained in both raf1+ and raf2+ reconstituted tas3WG-TAP cells (Figure 2C and 2E, Figure S1A and S1B). Consistent with this failure to suppress high levels of centromeric transcription in tas3WG-TAP cells transiently depleted for raf1+ or raf2+, these cells fail to engage the RNAi pathway to promote destruction of centromeric transcripts into siRNAs (Figure 2D and 2F).

Figure 2. Clr-C components raf1+ and raf2+ facilitate establishment of repressive centromeric heterochromatin.

A. Serial dilution assay of raf1+ reintegration strains bearing the cen::ura4+ reporter, and plated on specified media. Strains analyzed: PY2036, 3287, 3659, 3707, 3708, 3710, 3711. B. Serial dilution assay to monitor heterochromatin establishment in raf2Δ cells into which raf2+ has been reintegrated in tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP backgrounds. Strains analyzed: PY2036, 3675, 3676, 3781, 3783, 3791, 3792. C. Real time PCR analysis of dh centromeric transcripts relative to transcripts from adh1+. Data shown represent the mean ± SEM measurements from cDNA derived from two independent cultures, normalized to the wild type cen::ura4+ strain (PY2036). Strains analyzed: PY2036, 3287, 3659, 3707, 3710, 3711. See also Figure S1A. D. Northern blotting for dg and dh siRNAs and for the loading control SnoR69 on small RNA populations derived from indicated strains (as used in (C) and PY3708). E. Real time PCR analysis of cDNA to monitor centromeric transcript accumulation following reintegration of raf2+ into raf2Δ cells bearing the tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP alleles. Transcripts from dh were measured relative to the adh1+ control. Data were normalized to wild type cen::ura4+ strains, and represents mean ± SEM. Strains analyzed: PY2036, 3494, 3497, 3293, 3781, 3783, 3791, 3792. See also Figure S1B. F. Northern blot analysis of siRNAs derived from dg and dh regions of the centromere, with SnoR69 as a loading control. Strains were as listed in (E).

Transient depletion of Pcu4 in tas3WG cells causes defective heterochromatin assembly

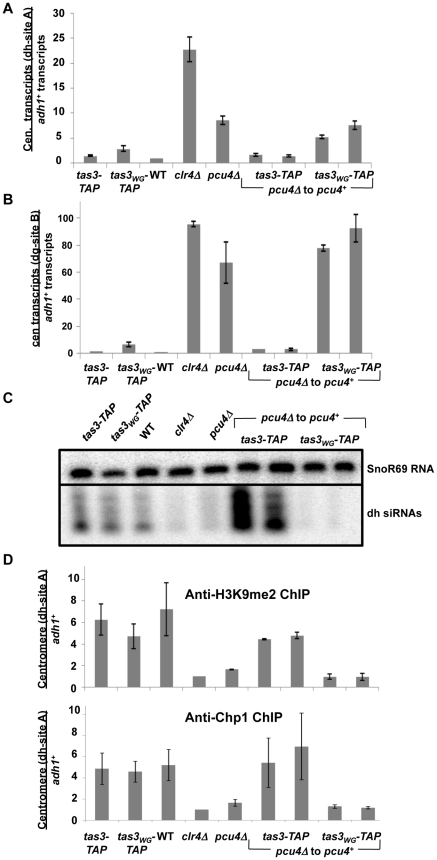

Pcu4 is the fission yeast cullin4, and it has been identified in complex with the UV-DDB1 E3 ubiquitin ligase [35], [36], and with the related Rik1 protein in the Clr-C complex [27]–[29]. To define the role of Pcu4 in heterochromatin establishment, we monitored heterochromatin assembly following reintroduction of the pcu4+ gene into pcu4Δ tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP strains. Clearly centromeric transcripts accumulate in pcu4Δ cells, and processing of transcripts is efficiently resumed following re-introduction of the wild type gene into tas3-TAP cells (Figure 3A and 3B). However, both dh and dg transcript levels are maintained at high levels following pcu4+ reintroduction into pcu4Δ tas3WG -TAP cells. This failure to silence centromeric transcripts was reflected in the failure to produce abundant centromeric siRNAs in these tas3WG reconstituted cells (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Pcu4 is required for establishment of repressive centromeric heterochromatin.

A. Real time PCR analysis of centromeric transcripts from dh sequences relative to adh1+ in cDNA derived from the indicated strains. Data represent mean ± SEM, normalized to wild type strain (PY41). Strains used were PY1065, PY2268, PY41, PY1797, PY3515, PY5082, PY5083, PY5085, PY5086. B. Real time PCR analysis of centromeric transcript accumulation from dg repeats. Samples were processed as described in (A). C. Northern blotting for dh siRNAs and SnoR69 as a loading control in small RNAs from strains listed in (A). D. ChIPs of H3K9me2 (upper panel) and Chp1 (lower panel) association with centromeric dh sequences, with adh1 serving as control. Strains analyzed were as for (A), and data represents mean ± SEM from duplicate ChIP experiments, quantified by real time PCR.

In summary, all components of Clr-C are defective for silencing of endogenous centromeric or centromeric reporter transcripts following their transient depletion in tas3WG cells, suggesting that their continuous presence is required for the initiation of heterochromatin in RITS-defective cells.

Defective heterochromatin assembly on transient depletion of Clr-C complex in tas3WG cells correlates with absence of centromeric H3K9me2

Next we analyzed H3K9 methylation on centromeric sequences following transient depletion of components of the Clr-C complex. In wild type cells, H3K9me accumulates to high levels on centromeric repeats through both RNAi-dependent and RNAi-independent mechanisms [15], [30]. In cells lacking pcu4, H3K9me2 levels on dh sequences are not above the background seen for clr4Δ cells which lack H3K9me2 (Figure 3D, upper panel). Following pcu4 + reintroduction into pcu4Δ tas3-TAP cells, H3K9me2 levels rise to that seen in tas3-TAP cells, whereas no significant accumulation of H3K9me2 is observed in pcu4 + reconstituted tas3WG-TAP cells. Thus Clr4 mediated H3K9 methylation is abrogated in tas3WG-TAP cells transiently depleted for pcu4. This methylation defect is not likely due to defective reassembly of the Clr-C complex following transient depletion of pcu4, since H3K9 methylation resumes effectively in pcu4+ reconstituted tas3-TAP cells.

Chp1 binds H3K9me2/3 and Chp1 recruitment to centromeres is a hallmark of heterochromatin. ChIP experiments performed with anti-Chp1 antibodies demonstrated that pcu4Δ cells are also defective for Chp1 association with centromeres, and pcu4+ reconstitution of pcu4Δ tas3-TAP but not of pcu4Δ tas3WG -TAP cells promotes Chp1 association with centromeres (Figure 3D, lower panel).

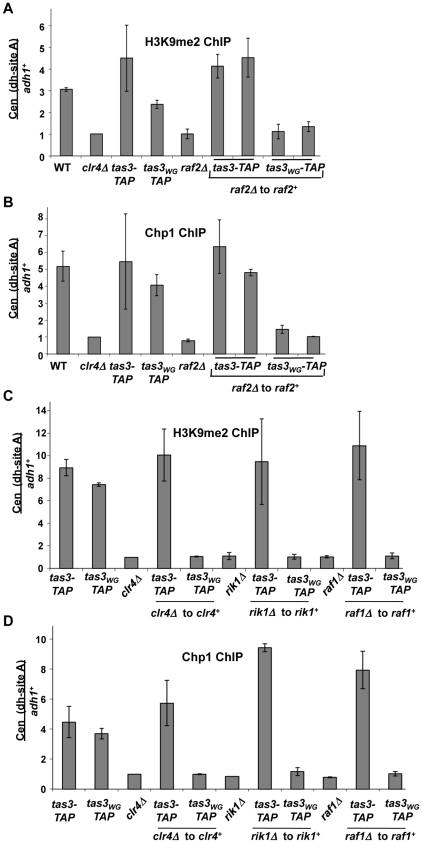

We also assessed H3K9me2 levels at centromeres in other strain backgrounds. In all Clr-C mutants (raf2, rik1, raf1), centromeric H3K9me2 levels were no higher than seen in clr4Δ cells (Figure 4A and 4C). Following reconstitution with raf2+, clr4+, rik1+, or raf1+, tas3-TAP cells accumulated “wild type” levels of H3K9me2, but tas3WG-TAP cells failed to accumulate H3K9me2 at centromeres.

Figure 4. Components of the Clr-C complex are required for establishment of H3K9me2 at centromeres.

A. ChIP analysis of H3K9me2 at dh repeats compared with adh1+ locus measured by real time PCR. Enrichment of H3K9me2 was normalized to a strain lacking clr4+. Data represents the mean of 2 independent ChIP experiments ± SEM. Strains analyzed PY2036, 1838, 3494, 3497, 3293, 3781, 3783, 3791, 3792. B. ChIP analysis of Chp1 occupancy on centromeric dh repeats relative to adh1+, measured by real time PCR. ChIP values were normalized to strains lacking clr4+, and are the mean ± SEM of two independent ChIP experiments. Strains analyzed as in (A). C. Real time PCR quantitation of ChIP of H3K9me2 at centromeric dh repeats in tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP strains following reintegration of clr4+, raf1+, and rik1+ into knockout backgrounds, measured relative to adh1+. Data represents mean ± SEM of 2 independent ChIP experiments and combine analyses for 2 reintegrants. Data were normalized to a strain lacking clr4Δ (PY1838). Strains analyzed PY3494, 3497, 1838, 2678, 2679, 2680, 2681, 3776, 4879, 4880, 4881, 4882, 3287, 3707, 3708, 3710, 3711. D. Real time PCR analysis of ChIP material derived from strains analyzed in (C), assessed for Chp1 association with centromeric dh repeats (site A). Data were processed as described in (C).

Very similar results were obtained for Chp1 association with centromeres (Figure 4B and 4D), consistent with tas3WG-TAP cells being dependent on constitutive expression of all components of the Clr-C complex to provide H3K9me2 at centromeric sites for recruitment of Chp1. In sum, these experiments demonstrate that in cells where the association of Ago1 with Chp1-Tas3 has been abrogated, that reintroduction of Clr-C components is not sufficient to direct H3K9me2 accumulation on centromeric repeats. Clr-C defective cells should still express heterochromatin independent siRNAs, and Ago1 in these cells would be expected to maintain association with primal RNAs. Thus targeting of Ago1 by priRNAs to centromeric repeats is not sufficient to drive Clr-C recruitment to centromeres when Ago1 is physically separated from Tas3-Chp1.

Dicer knockout cells show efficient assembly of centromeric heterochromatin on reintegration of the dcr1 + gene

Next we examined whether RNAi components contribute to the initial steps in heterochromatin assembly. RNAi defective cells, such as dcr1Δ, are expected to retain priRNAs but lose most of their siRNAs. In contrast to Clr-C defective cells, dcr1Δ cells maintain low levels of H3K9me2 at centromeres (Figure S2D). Following overexpression of dcr1+, both dcr1Δ tas3-TAP and dcr1Δ tas3WG -TAP cells efficiently assembled heterochromatin [10]. This suggested that H3K9me2, and not siRNA, acts at an early stage of heterochromatin initiation. However, in these experiments it was unclear whether overexpression of dcr1+ suppressed an establishment defect in tas3WG dcr1+ reconstituted cells [10], [14].

We directly tested whether integration of dcr1+ into the genomic dcr1Δ locus of tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP cells could support reassembly of centromeric heterochromatin. Cells lacking dcr1+ fail to silence the cen::ura4+ centromeric transgene. Following reintegration of dcr1+, silencing of the cen::ura4 + reporter resumed in both dcr1Δ to dcr1+ tas3-TAP and dcr1Δ to dcr1+ tas3WG-TAP cells (Figure S2A). Cells lacking dcr1+ accumulate high levels of centromeric transcripts, but following dcr1+ reintegration, centromeric transcript levels were reduced in both the dcr1+ reconstituted tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP cells, confirming that reintegration of dcr1+ promoted efficient assembly of centromeric heterochromatin (Figure S2B, S2C). In addition, dcr1Δ cells cannot generate siRNAs from centromeric transcripts, but on reintegration of dcr1+, siRNA production resumed efficiently in both tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP backgrounds (Figure S2D). Together, these results confirmed and extended our data obtained with overexpressed dcr1+ [10]. dcr1+ and siRNAs are not critical for Clr-C activity at centromeres, but are important for amplification of the H3K9me2 signal during later stages of heterochromatin assembly.

Components of the RDRC complex are not required for heterochromatin assembly in tas3WG cells

We next asked whether transient depletion of genes that act upstream of Dcr1 in the RNAi pathway would cause defective heterochromatin establishment. RDRC acts upstream of Dcr1, generating dsRNA for siRNA production. RDRC consists of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Rdp1), the RNA helicase Hrr1, and a non-canonical poly (A) polymerase, Cid12 [11]. Cells lacking any component of RDRC show reduced RITS association and reduced H3K9me2 at centromeres, and have reduced siRNA production [11], [19], [20].

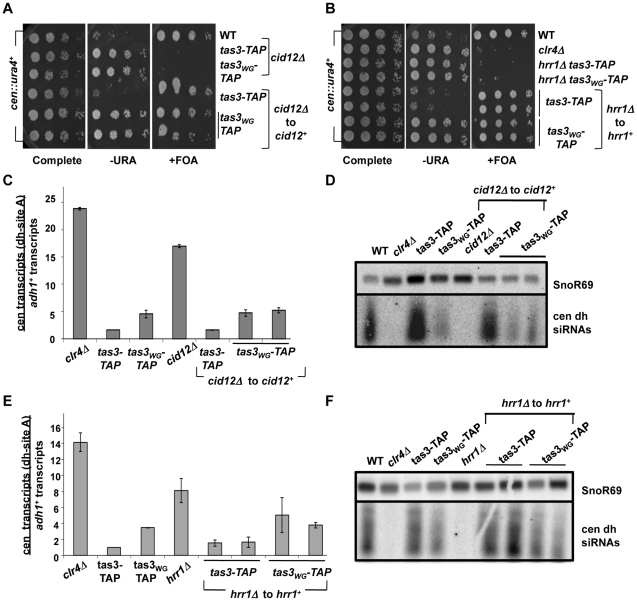

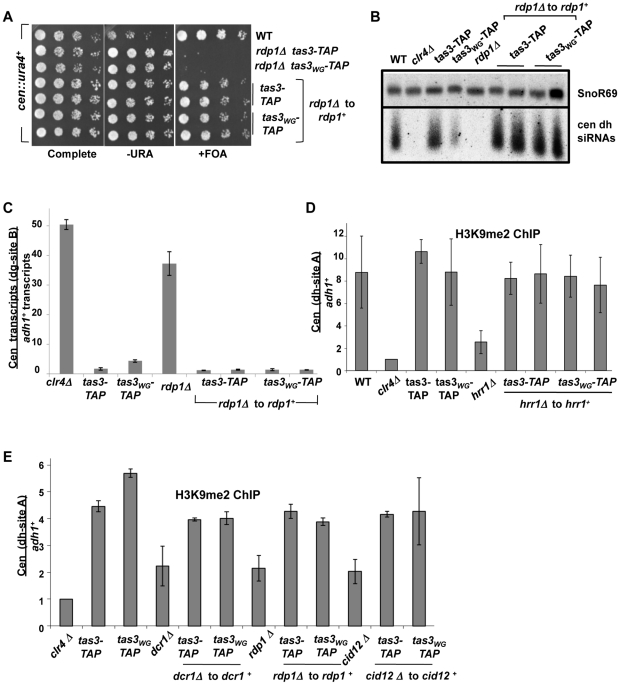

We introduced the tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP alleles into deletion mutants of all components of RDRC, and then tested whether silenced chromatin assembled on the cen::ura4+ reporter following reintegration of genomic clones encoding these genes. For cells lacking cid12+, hrr1+, or rdp1+, reintegration of these genes into knockout tas3-TAP cells allowed efficient assembly of heterochromatin. Interestingly, as seen for Dcr1, reintroduction of the genes into the mutant tas3WG-TAP strains also supported silencing of the cen::ura4+ reporter (Figure 5A and 5B, Figure 6A).

Figure 5. cid12+ and hrr1+ RDRC components are not required to initiate silencing of centromeric heterochromatin.

A. Serial dilution spotting assay to monitor the role of cid12+ in the silencing of the cen::ura4+ reporter gene. Cells of the indicated genotypes and carrying the cen::ura4+ reporter were plated onto selective media. Following reintegration of cid12+ into the cid12Δ locus (cid12Δ to cid12+), both tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP cells grew on FOA media. Strains analyzed were PY2036, 4338, 4340, 4423, 4424, 4425. B. Serial dilution spotting assay of strains carrying the cen::ura4+ reporter, following hrr1+ reintegration at the hrr1Δ locus (hrr1Δ to hrr1+) and assessed for ura4 expression compared with control strains on selective media. Strains analyzed: PY2036, 1838, 4334, 4336, 4420, 4481, 4586, 4587. C. Real time PCR analysis of cDNAs derived from indicated strains, quantifying centromeric dh transcripts relative to adh1+ and normalized to ratio obtained in wild type cells. Data represent mean ± SEM from 2 independent RNA preparations. Strains analyzed: PY2036,1838, 3494, 3497, 4312, 4423, 4424, 4425. See also Figure S3A. D. Small RNA northern blot was hybridized with a probe for centromeric dh siRNAs, and with a probe for snoR69 as a loading control. Small RNAs were derived from strains used in (C). E. Real time PCR analysis of dh relative to adh1+ transcripts in cDNA derived from indicated strains. Values represent means of 2 RNA preparations ± SEM. Strains analyzed: PY2036, 1838, 3494, 3497, 4308, 4420, 4481, 4586, 4587. See also Figure S3B. F. Northern blot for small RNA species hybridizing to the cen dh probe and to snoR69 as loading control. Strains are listed in (E).

Figure 6. RDRC components are not required for establishment of silent H3K9me2 chromatin at centromeres.

A. Serial dilution assay of strains bearing the cen::ura4+ reporter and of the indicated genotype, plated on selective media. Strains analyzed: PY2036, 4300, 4304, 4401, 4402, 4403 and 4404. B. Northern blotting for small RNAs derived from dh centromeric repeats, with snoR69 RNA as loading control. Strains analyzed: PY 2036, PY1838, 3494, 3497, 4274, 4401, 4402, 4403, 4404. C. Real time PCR analysis of cDNA derived from strains of the indicated genotypes (as for Figure 6B), measuring centromeric dh transcripts normalized to adh1+, and to a wild type strain (PY2036). Data represents the mean ± SEM from analysis of 2 independent cDNA preparations from duplicate biological samples. See also Figure S4A. D. Real time PCR analysis of ChIP material derived using antibodies against H3K9me2, analyzed for centromeric dh sequences and normalized to euchromatic adh1+ sequences. Data represent mean from two independent experiments ± SEM, normalized to data obtained from clr4Δ cells. Strains analyzed: PY2036, 1838, 3494, 3497, 4308, 4420, 4481, 4586, 4587. See also Figure S4B. E. ChIP for H3K9me2 at centromeric dh sequences relative to adh1+, normalized to a clr4Δ strain. Duplicate ChiP experiments were performed and data were processed as described above. Strains analyzed included dcr1+ reintegration strains (dcr1Δ to dcr1+), rdp1+ reintegration strains (rdp1Δ to rdp1+) and cid12+ reintegrants (cid12Δ to cid12+). Two independent gene reintegrants for each tas3WG-TAP strain background were tested in duplicate. Strains analyzed: PY 2036, 3494, 3497, 3235, 3501, 3502, 3499, 3500, 4274, 4401, 4402, 4403, 4404, 4312, 4423, 4424, 4425.

Transcript analyses performed on the RDRC reconstituted strains revealed that cells lacking RDRC components accumulate both centromeric dg and dh transcripts, but that on reconstitution with the wild type gene, dg and dh transcript levels dropped to levels close to those normally found in tas3-TAP or tas3WG-TAP cells, which is considerably less than seen in RDRC mutant cells (Figure 5C and 5E, Figure 6C, and Figures S3A, S3B, and S4A). Thus processing of centromeric transcripts is efficiently resumed following reintroduction of RDRC components into RDRC deficient tas3WG cells, and this conclusion is further supported by detection of siRNAs in RDRC reconstituted cells (Figure 5D, 5F and Figure 6B). In summary, in contrast to cells transiently depleted for Clr-C components, centromeric heterochromatin assembly can occur efficiently following the transient depletion of RDRC components or of dcr1 + in tas3WG cells.

Low levels of H3K9me2 at centromeres in RDRC deficient cells support assembly of heterochromatin in reconstituted tas3WG cells

Cells lacking dcr1+ accumulate H3K9me2 on centromeric sequences, whereas Clr-C deficient cells completely lack H3K9me2. We therefore asked whether cells lacking RDRC components accumulate centromeric H3K9me2, and whether H3K9me2 levels could signal the difference in outcome, promoting heterochromatin assembly in tas3WG cells following transient depletion of RDRC, but not Clr-C components.

We assessed centromeric H3K9me2 levels in RDRC deficient cells and following reintegration of RDRC components. In these experiments, we note that in all RDRC mutants, the level of H3K9me2 at centromeres is considerably higher than seen in cells lacking clr4+, although at least 2 fold reduced compared with wild type cells. Reintegration of RDRC components into the corresponding RDRC null cells supported centromeric accumulation of H3K9me2 of both tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP cells to levels found normally (Figure 6D and 6E). In addition, although Chp1 association with centromeres is diminished in hrr1Δ cells, reintroduction of hrr1+ into tas3WG-TAP cells promoted Chp1 association (Figure S4B). Together then this data shows that heterochromatin assembly occurs efficiently following transient depletion of genes required for siRNA synthesis, including RDRC components that act upstream of Dcr1. In addition, the ability of heterochromatin to reform efficiently, following transient depletion of RNAi components in tas3WG cells, correlates with the persistence of low levels of H3K9me2 on centromeric repeats in the mutant backgrounds.

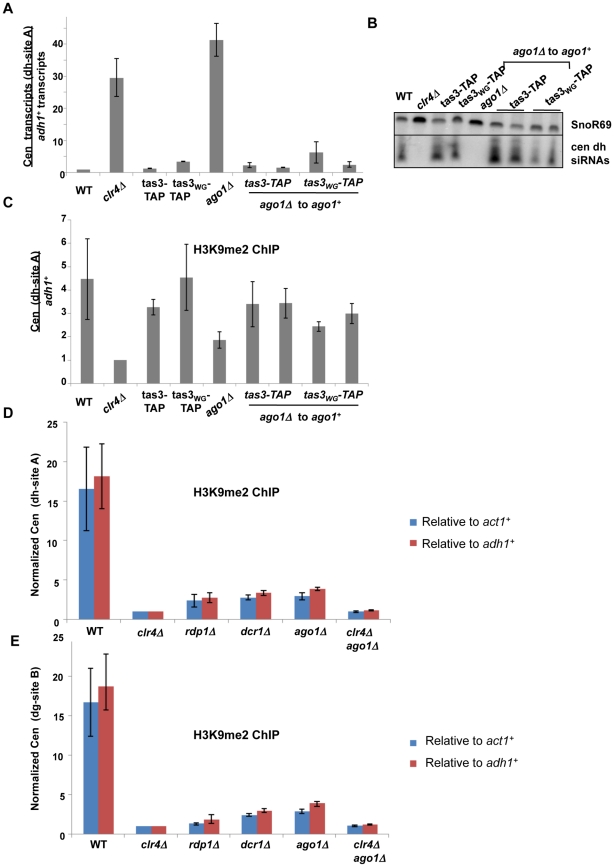

Transient depletion of Ago1 in Tas3WG cells causes no defect in heterochromatin establishment

Very recently it has been proposed that Ago1 is the most upstream factor in heterochromatin assembly. It is thought to act as an acceptor for RNA degradation products, termed pri-RNAs, which, based on frequency of occurrence, preferentially target antisense transcripts resulting from bidirectional transcription of DNA repeats. Cleavage of nascent centromeric transcripts by priRNA-directed activity of Ago1 is proposed to recruit the RDRC complex and eventually promote siRNA-dependent recruitment of RITS, and subsequent robust assembly of heterochromatin via recruitment of Clr-C [20]. This model therefore places Ago1 as an initiator, upstream of RDRC and Dcr1 and of the Clr-C complex and H3 K9 methylation. This model is supported by the detection of small RNAs (priRNAs) in dcr1Δ strains, and of siRNAs in cells lacking clr4+, or in which heterochromatin assembly is blocked because of mutation of H3K9, supporting that heterochromatin is not essential for small RNA generation [19], [20]. Finally, the model would suggest that siRNAs and priRNAs act upstream of heterochromatin assembly, and that Ago1 is the most upstream component of the RNAi pathway. Indeed, Halic and Moazed argue that Ago1 activity is required for the initial deposition of H3K9me, since in their publication strains lacking Ago1 exhibit lower levels of centromeric H3K9me accumulation than strains deficient in other components of the RNAi pathway [20].

To test the role of Ago1 in heterochromatin assembly, we first performed transient depletion experiments for Ago1 in the tas3WG-TAP background (Figure 7). We integrated a genomic clone of ago1+ into ago1 null tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP cells, and monitored heterochromatin assembly. In contrast to ago1 null cells, where centromeric transcripts are highly elevated (above the levels seen in clr4Δ cells), reintroduction of ago1+ into either tas3-TAP or tas3WG-TAP cells reduced centromeric dh and dg transcripts to levels seen normally in tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP cells (Figure 7A and Figure S5A). Consistent with this suppression, we found that unlike ago1 null cells, where siRNA production is severely reduced, centromeric siRNAs are synthesized at normal levels following reintroduction of ago1 + (Figure 7B). Next, we performed ChIP experiments to monitor H3K9me2 levels in ago1Δ cells. ago1 deletion reduces H3K9me2 accumulation at centromeres below that of wild type cells, but above that of clr4Δ cells. On reintroduction of ago1+, centromeric H3K9me2 levels accumulate to normal levels (Figure 7C), similar to the results seen on reintegration of other RNAi components into tas3WG cells. These data suggest that cells lacking ago1 behave similarly to other RNAi defective strains, and functionally that there is sufficient H3K9me2 in ago1Δ tas3WG cells to drive heterochromatin assembly following reintroduction of ago1+. We further analyzed centromeric H3K9me2 levels in RNAi defective strains. At the 2 sites tested within centromeric dg and dh repeats, H3K9me2 levels were significantly elevated in ago1Δ cells above the background levels in clr4Δ or ago1Δ clr4Δ cells, and H3K9me2 accumulation at centromeres was similar in all RNAi deficient backgrounds tested. This data would suggest that Ago1, like other RNAi components, is not acting upstream of Clr-C for heterochromatin assembly.

Figure 7. Ago1 reintegration into tas3WG cells promotes heterochromatin assembly, and ago1 null cells retain significant centromeric H3K9me2.

A. Real time PCR analysis of cDNA derived from the indicated strains, measuring centromeric dh transcripts normalized to adh1+, and to a wild type strain (PY 42). Data represents the mean ± SEM from analysis of 2 independent cDNA preparations from duplicate biological samples. Strains used: PY 42, 1798, 1064, 2267, 901, 5193, 5194, 5202, 5203. See also Figure S5A. B. Small RNA Northern blot to identify centromeric dh siRNAs, with SnoR69 as a loading control. Samples used as in (A). C. ChIP for H3K9me2 on centromeric dh repeats, assessed by real time PCR and normalized to adh1 association. Data represents mean of duplicate independent ChIP experiments ± SEM. Strains as listed in (A). D. ChIP for H3K9me2 on centromeric dh repeats, assessed by real time, and normalized to both act1+ and adh1+ association. Data represent mean of 4 independent ChIP experiments ± SEM. Strains analyzed are PY42, 1798, 1478, 1550, 901, 5236. Two tailed P value for ago1Δ vs clr4Δ and for ago1Δ vs ago1Δclr4Δ = <0.0001 in t test for data normalized to adh1+, and p = 0.0053 (ago1Δ vs clr4Δ) and p = 0.0058 (ago1Δ vs ago1Δclr4Δ) for data normalized to act1+. E. ChIP for H3K9me2 on centromeric dg repeats, as described for (D). Two tailed P value for ago1Δ vs clr4Δ = 0.0005 and for ago1Δ vs ago1Δclr4Δ = <0.0008 in t test for adh1 normalized data, and p = 0.001 (ago1Δ vs clr4Δ) and p = 0.0016 (ago1Δvs ago1Δclr4Δ) for act1 normalized data.

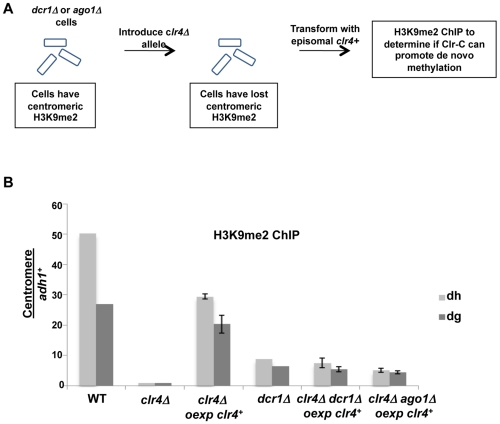

RNAi pathway is not required for initial step in heterochromatin initiation

Our demonstration that heterochromatin can assemble following transient depletion of RNAi components in tas3WG cells is suggestive that the RNAi pathway is acting downstream of Clr-C. However, given that low levels of centromeric H3K9me2 are maintained in RNAi-defective cells, it is difficult to assess whether RNAi is required for the initial step in heterochromatin initiation. To address this question, we removed residual H3K9me2 from RNAi defective cells by introduction of the clr4Δ allele. We then tested whether H3K9me2 could be deposited at centromeres following expression of Clr4 in these cells that lack both Clr4 and Ago1 or Clr4 and Dcr1 (Figure 8A). Following overexpression of clr4 + in ago1Δclr4Δ cells, H3K9me2 could be detected on centromeric repeats above the background observed in clr4 null cells, and similar to levels found normally in ago1Δ cells. Similar results were obtained following overexpression of clr4 + in dcr1Δclr4Δ cells (Figure 8B). Thus, when overexpressed, Clr4 can target centromeric repeats to initiate H3K9me2 deposition in the absence of a functional RNAi pathway. We note, however, that reintroduction of clr4+ into its normal locus in these cells is not sufficient, in the absence of the RNAi pathway, for accumulation of detectable centromeric H3K9me2 (data not shown). Together, these experiments strongly indicate that Clr-C can initiate H3K9me deposition at centromeres via RNAi-independent mechanisms, but that cooperation between RNAi-dependent and RNAi-independent factors normally results in full heterochromatin assembly (summarized in Figure 9).

Figure 8. Initial Clr-C recruitment to centromeres can occur independently of ago1+ and dcr1+.

A. Schematic for removal of residual H3K9me2 in dcr1Δ or ago1Δ cells by introduction of clr4Δ, prior to re-expression of genomic clr4+ from episomal vector to test for Clr-C's ability to promote de novo heterochromatin assembly in RNAi-deficient tas3WG cells. B. Removal of residual H3K9me2 in dcr1Δ and ago1Δ cells was performed by generation of double mutants with clr4Δ, and then ability of Clr-C to generate de novo centromeric H3K9me2 methylation was tested in absence of RNAi pathway following transformation with genomic clr4+ plasmid. H3K9me2 ChIP was performed on indicated strains, and assessed by real time PCR analysis. Strains analyzed: PY12, 5516, 5557, 5517, 1637, 5522, 5523, 5520, 5521. All were grown in PMG-his media. Data represent mean of 3 or 4 ChIPs ±SEM for all samples except dcr1Δ and WT for which 1 ChIP is shown.

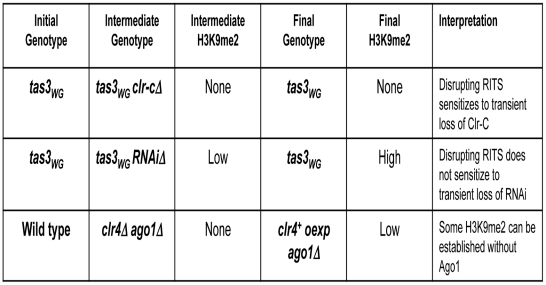

Figure 9. Table summarizing results from this study.

Tas3WG cells lacking Clr-C components lack H3K9me, but retain heterochromatin independent siRNAs and priRNAs. These cells cannot support recruitment of Clr-C to centromeres following reintegration of the missing Clr-C component. In contrast, Tas3WG cells lacking RNAi components retain residual H3K9me, but lack siRNAs. On reintegration of the missing RNAi component, these cells convert to allow full heterochromatin assembly on centromeric repeats. These results suggest that Clr-C can function independently of the RNAi pathway in the assembly of centromeric heterochromatin. To further test this hypothesis, H3K9me was withdrawn from RNAi deficient cells to determine whether Clr-C can target centromeres de novo independently of the RNAi pathway. Overexpression of Clr4 in clr4Δago1Δ cells supports recruitment of Clr-C activity to centromeric repeats to allow initiation of heterochromatin. These data suggest that normally RNAi-independent and RNAi-dependent mechanisms cooperate for full heterochromatin assembly.

Discussion

We have utilized our novel mutant, tas3WG, to identify genetic requirements for heterochromatin initiation as opposed to those required for the maintenance of pre-existing heterochromatin. We used an approach in which genes required for heterochromatin formation are deleted and reintroduced and then heterochromatin assembly is examined. In wild-type cells, heterochromatin can be established regardless of the factor removed, indicating that establishment mechanisms are robust to perturbations of the system. However, in cells harboring a disrupted RITS complex, we found that the establishment of silencing becomes sensitive to the prior presence of particular silencing factors. Our data demonstrate that the ability to assemble heterochromatin in such gene removal-restoration experiments in tas3WG cells correlates with the prior presence of H3K9me2 on centromeric repeats, but does not require the prior presence of small RNA species. These data strongly suggest that RNAi-independent mechanisms of recruitment of Clr-C play a key role in the assembly of centromeric heterochromatin.

We also tested whether RNAi is required in an obligate manner to initiate de novo heterochromatin assembly in cells that lack any prior H3K9me. To accomplish this, we generated clr4Δ dcr1Δ cells and found that some deposition of H3K9me2 at centromeric sequences occurred upon overexpression of clr4+ (Figure 8C). These experiments clearly demonstrate that Clr-C can function to initiate de novo centromeric heterochromatin assembly independently of the RNAi pathway.

Recently, Ago1 and its associated priRNAs have been proposed to trigger heterochromatin formation. This notion is partly based on an observation that an ago1Δ strain had little or no H3K9me2 at centromeres, suggesting an upstream role for Ago1 [20]. If this hypothesis were correct, we anticipated that in our tas3WG system, that transient depletion of Ago1 might block heterochromatin assembly similar to what we observed for Clr4. In contrast, we found that tas3WG cells formed robust centromeric heterochromatin on reintroduction of ago1+ into ago1Δ cells (Figure 7A–7C). Consequently, we re-examined the reported critical Dicer-independent role for Ago1 in driving H3K9Me. In contrast to a recent study [20], we found that H3K9me2 levels in ago1Δ cells were no lower than in other RNAi-defective backgrounds (Figure 7D and 7E). To further probe for a potential role of priRNAs in heterochromatin initiation, we generated cells that lack both Ago1 (which binds priRNAs) and Clr4, and tested whether reintroduction of Clr4 could promote de novo centromeric H3K9me2 in the absence of Ago1-priRNA targeting activities. This experiment revealed that indeed Clr4, when overexpressed, can initiate H3K9me2 deposition at centromeres independent of Ago1 (Figure 8C).

Taken together, our data demonstrate (1) that Clr-C components can act independently of members of the RNAi pathway to initiate heterochromatin assembly and (2) the ability to promote heterochromatin assembly in tas3WG cells correlates with the prior levels of centromeric H3K9me2 in mutant backgrounds, and not the initial small RNA abundance and (3), that Ago1-bound priRNAs are unlikely to be the key initiator of heterochromatin assembly. The functional data that we present therefore counters the model for heterochromatin initiation proposed recently [20], and supports that RNAi-independent factors, together with the RNAi pathway, are necessary for full heterochromatin assembly.

The conclusions that derived from our observations contrast with the widely held belief that RNAi initiates heterochromatin assembly at fission yeast centromeres. Although it has been shown by several labs that small RNAs derived from exogenous hairpin RNAs can induce silencing of genomic loci [37], [38], these effects tend to be very weak and very locus specific. In these experiments, silencing efficiency correlates with proximity to sites of heterochromatin, or is enhanced by overexpression of heterochromatin proteins.

The production of the majority of centromeric small RNAs depends on the presence of heterochromatin. However, low levels of small RNAs are found in Clr-C deletion backgrounds [12], [20] or in histone H3K9R mutant cells [19]. Interestingly, Clr-C mutants that completely lack H3K9me are deficient for heterochromatin establishment in our reintegration assay, in spite of the presence of centromeric siRNAs (which are below the level of detection of our Northern assay). In contrast, RNAi-defective strains that are devoid of, or express even lower levels of centromeric small RNAs than Clr-C mutants [12], [19], [20], can assemble heterochromatin effectively following reintegration of the wild type gene into the tas3WG background.

Although not easy to detect, priRNAs, which have been postulated to prime heterochromatin establishment, are expected to be present in all of the genetic backgrounds that we tested for heterochromatin initiation. This class of small RNAs therefore does not appear to contribute to the differential ability of mutants to initiate heterochromatin assembly in the tas3WG background. Finally, our data showing that transient depletion of ago1 + does not impair heterochromatin establishment in tas3WG cells, and that ago1Δ cells retain H3K9me2, would argue that ago1 + and priRNAs are not the initiating trigger for heterochromatin assembly.

These results beg the question of how low levels of siRNA synthesis occur in the absence of heterochromatin, since early models suggested that localization of the RITS and RDRC complexes to centromeres was a prerequisite for centromeric siRNA generation, and that RITS and RDRC complex localization was dependent on Clr4 [8], [11]. One study suggested that single-stranded transcripts from centromeric sequences can adopt secondary structures to yield dsRNA that can be targeted by Dcr1 to form siRNAs [19]. Such models for the heterochromatin-independent synthesis of centromeric siRNAs may now help to explain our previously puzzling result that Chp1 chromodomain mutants that are defective for heterochromatin establishment following transient depletion of clr4+ express abundant siRNAs [6].

How low levels of H3K9me2 are initially placed at centromeres remains an open question, but our data supports that it is not absolutely dependent on small RNAs and the RNAi pathway. We suggest that H3K9me2 deposition is linked to the transcription of the centromere. Mutants in three separate components of the RNA pol II complex show defects in heterochromatin assembly, including a mutant that truncates the C terminal repetitive tail of the largest subunit of the polymerase, Rpb1 [16]–[18]. This raises the intriguing possibility that, similar to other histone modifying enzymes such as the Set1 and Set2 methyltransferases, that Clr-C may associate with, and be brought to chromatin, via RNA polymerase II [39]. Another mutation in RNA pol II that causes defective heterochromatin assembly resides in the Rpb7 subunit [16], which together with its partner, Rpb4, is thought to be an accessory and non-obligate component of yeast RNA pol II. One interesting possibility would be if Clr-C recruitment to regions of chromatin that are destined to become heterochromatic was controlled by modulation of RNA pol II by the Rpb4/7 subcomplex. In contrast, in plants, two pol II-related RNA polymerase activities, Pol IV and Pol V, have evolved to mediate heterochromatin assembly on repetitive sequences (reviewed in [40]).

Materials and Methods

Plasmid construction

Integration plasmids for genomic clones were constructed by PCR using Phusion polymerase (NEB) and standard cloning or Gateway (Invitrogen) techniques. Oligonucleotide sequences are listed in Table S2. Full details of plasmid construction are listed in Text S1.

Strain generation

Strains used in this study are listed in Table S1 and details of their construction and verification are in Text S1.

Serial dilution assays on selective media

Cells were cultured overnight at 25°C in rich YES medium to a density of approximately 5×106 cells/ml. Cells were washed extensively in PMG media, counted, and five-fold serial dilutions made, such that plating of 4 ul of cells yielded 1.2×104 cells within the most concentrated spot. Plating was performed on PMG complete media, PMG media lacking uracil, and PMG complete media supplemented with 2g FOA per liter as described previously [21], and incubated for 5 days at 25°C.

Transcript and siRNA analyses

Transcript and siRNA analyses were performed as previously described [10], [21]. Oligos for real time PCR analysis: (dh) JPO-769 and JPO-770, (dg) JPO-986, JPO-987, adh1, JPO-793 and JPO-794 [10]. RNA was prepared from duplicate cultures for every experiment, and for analyses following gene reintegration, multiple independent re-integrants were assessed.

Real-time PCR was performed on an Eppendorf Mastercycler ep Realplex machine using Quantifast Sybr green (Qiagen). Data was analyzed using the ΔCt method, ensuring that all samples gave Ct values within the experimentally determined linear range.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation analyses

Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed as previously described [10], [21], using antibodies that recognize H3K9me2 (Abcam) and Chp1 (Abcam). Further details are in Text S1.

Supporting Information

Analysis of transcript accumulation from dg sites within the centromere by real time PCR analysis. A. Transcripts from cen dg sequences were measured by real time PCR relative to adh1+ transcript accumulation in cDNA derived from strains listed in Figure 2C (raf1Δ to raf1 +). Duplicate RNA preparations were used to generate duplicate cDNAs and data represent mean ± SEM. B. Centromeric transcripts from the dg region of the centromere were measured by real time PCR of cDNA derived from strains listed in Figure 2E (raf2Δ to raf2 +). Analysis was performed as described above.

(0.01 MB PDF)

Analysis of strains bearing genomic reintegration of dcr1 +. A. Serial dilution assay to monitor growth of cen::ura4 + reporter strains on non-selective media (complete), media lacking uracil (−URA), or media supplemented with FOA (+FOA). Following reintegration of dcr1 + into the genomic dcr1Δ locus, both tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP isolates were able to grow on FOA. Strains used were PY2036, 3310, 3307, 3501, 3502, 3499, 3500. B. Real time PCR analysis of centromeric transcript accumulation from the dh repeat sequences relative to adh1 + transcript accumulation in cDNA derived from the indicated strains. Two independent reintegrants of dcr1 + (dcr1Δ to dcr1 +) were analyzed for both the tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP backgrounds. Data represent mean ± SEM for cDNA samples from 2 independent RNA preparations for each strain. Data was normalized to wild type cen::ura4+ strain (PY2036), which was set at 1. Strains used were PY2036, 3310, 3307, 3501, 3502, 3499, 3500. C. Centromeric dg transcripts were measured by similar methods and using the same cDNA samples as used for (B). D. Northern blotting for small RNA species in RNA preparations from the strains listed in (B). Blot was probed for siRNAs derived from dh repeats and for the snoR69 RNA as a loading control.

(0.24 MB PDF)

Analysis of centromeric dg and dh transcript accumulation by real time PCR. A. Real time PCR analysis of dg centromeric transcripts relative to adh1 + in cDNA derived from strains listed in Figure 5C (cid12Δ to cid12 +). Duplicate RNA preparations were used to generate duplicate cDNAs and data represent mean ± SEM. B. Real time PCR analysis of transcripts derived from dg centromeric repeats relative to adh1 + in strains listed in Figure 5E (hrr1Δ to hrr1 +). Analysis was performed as described above.

(0.02 MB PDF)

Analysis of centromeric transcript accumulation in rdp1 null cells and Chp1 association with centromeric dh sequences in hrr1 mutant cells. A. Real time PCR analysis of transcripts derived from dh centromeric repeats relative to adh1 + in strains listed in Figure 6C (rdp1Δ to rdp1 +). Analysis was performed as described in Figure 6C. B. ChIP was performed with Chp1 antibodies on chromatin prepared from strains listed in Figure 6D. Real time PCR was used to quantify Chp1 association with dh relative to the euchromatic adh1 control. Data was normalized to cells lacking clr4 (set at 1), in which Chp1 does not associate with centromeres. Error bars represent the SEM of duplicate ChIPs using different biological samples.

(0.02 MB PDF)

Transient depletion of ago1 + does not affect establishment of silencing of centromeric transcripts in tas3WG cells. A. Real Time PCR analysis of cDNA prepared from indicated strains, measuring centromeric dg transcript accumulation normalized to adh1 + expression. Data represents mean average of analysis of 2 independent cDNA preparations from duplicate biological samples, measuring two independent ago1 + reintegrants for each background, with error bars representing SEM. Strains used were as in Figure 7A.

(0.01 MB PDF)

Strains used in this study.

(0.11 MB DOC)

Oligonucleotide sequences.

(0.06 MB DOC)

Supplemental experimental procedures.

(0.05 MB DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Moazed, G. Thon, and R. Allshire for deletion allele strains. Thanks to P. Brindle, M. Bix, G. Thon, J. Ihle, and members of Partridge Lab for their critical input.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

This work was supported by R01GM084045 (JFP), the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Core Support (5 P30 CA 021765-32), and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Yamada T, Fischle W, Sugiyama T, Allis CD, Grewal SI. The nucleation and maintenance of heterochromatin by a histone deacetylase in fission yeast. Mol Cell. 2005;20:173–185. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bannister AJ, Zegerman P, Partridge JF, Miska EA, Thomas JO, et al. Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature. 2001;410:120–124. doi: 10.1038/35065138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakayama J, Rice JC, Strahl BD, Allis CD, Grewal SI. Role of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation in epigenetic control of heterochromatin assembly. Science. 2001;292:110–113. doi: 10.1126/science.1060118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadaie M, Kawaguchi R, Ohtani Y, Arisaka F, Tanaka K, et al. Balance between distinct HP1 family proteins controls heterochromatin assembly in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6973–6988. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00791-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang K, Mosch K, Fischle W, Grewal SI. Roles of the Clr4 methyltransferase complex in nucleation, spreading and maintenance of heterochromatin. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:381–388. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schalch T, Job G, Noffsinger VJ, Shanker S, Kuscu C, et al. High-affinity binding of Chp1 chromodomain to K9 methylated histone H3 is required to establish centromeric heterochromatin. Mol Cell. 2009;34:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Partridge JF, Scott KS, Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T, Allshire RC. cis-acting DNA from fission yeast centromeres mediates histone H3 methylation and recruitment of silencing factors and cohesin to an ectopic site. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1652–1660. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verdel A, Jia S, Gerber S, Sugiyama T, Gygi S, et al. RNAi-mediated targeting of heterochromatin by the RITS complex. Science. 2004;303:672–676. doi: 10.1126/science.1093686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Djupedal I, Ekwall K. Epigenetics: heterochromatin meets RNAi. Cell Res. 2009;19:282–295. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Partridge JF, Debeauchamp JL, Kosinski AM, Ulrich DL, Hadler MJ, et al. Functional separation of the requirements for establishment and maintenance of centromeric heterochromatin. Mol Cell. 2007;26:593–602. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motamedi MR, Verdel A, Colmenares SU, Gerber SA, Gygi SP, et al. Two RNAi complexes, RITS and RDRC, physically interact and localize to noncoding centromeric RNAs. Cell. 2004;119:789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bayne EH, White SA, Kagansky A, Bijos DA, Sanchez-Pulido L, et al. Stc1: a critical link between RNAi and chromatin modification required for heterochromatin integrity. Cell. 2010;140:666–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugiyama T, Cam H, Verdel A, Moazed D, Grewal SI. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is an essential component of a self-enforcing loop coupling heterochromatin assembly to siRNA production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:152–157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407641102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Partridge JF. Centromeric chromatin in fission yeast. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3896–3905. doi: 10.2741/2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volpe TA, Kidner C, Hall IM, Teng G, Grewal SI, et al. Regulation of heterochromatic silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi. Science. 2002;297:1833–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.1074973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Djupedal I, Portoso M, Spahr H, Bonilla C, Gustafsson CM, et al. RNA Pol II subunit Rpb7 promotes centromeric transcription and RNAi-directed chromatin silencing. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2301–2306. doi: 10.1101/gad.344205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato H, Goto DB, Martienssen RA, Urano T, Furukawa K, et al. RNA polymerase II is required for RNAi-dependent heterochromatin assembly. Science. 2005;309:467–469. doi: 10.1126/science.1114955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schramke V, Sheedy DM, Denli AM, Bonila C, Ekwall K, et al. RNA-interference-directed chromatin modification coupled to RNA polymerase II transcription. Nature. 2005;435:1275–1279. doi: 10.1038/nature03652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Djupedal I, Kos-Braun IC, Mosher RA, Soderholm N, Simmer F, et al. Analysis of small RNA in fission yeast; centromeric siRNAs are potentially generated through a structured RNA. EMBO J. 2009;28:3832–3844. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halic M, Moazed D. Dicer-independent primal RNAs trigger RNAi and heterochromatin formation. Cell. 2010;140:504–516. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Debeauchamp JL, Moses A, Noffsinger VJ, Ulrich DL, Job G, et al. Chp1-Tas3 interaction is required to recruit RITS to fission yeast centromeres and for maintenance of centromeric heterochromatin. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2154–2166. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01637-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrie VJ, Wuitschick JD, Givens CD, Kosinski AM, Partridge JF. RNA interference (RNAi)-dependent and RNAi-independent association of the Chp1 chromodomain protein with distinct heterochromatic loci in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2331–2346. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2331-2346.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Till S, Lejeune E, Thermann R, Bortfeld M, Hothorn M, et al. A conserved motif in Argonaute-interacting proteins mediates functional interactions through the Argonaute PIWI domain. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:897–903. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allshire RC, Nimmo ER, Ekwall K, Javerzat JP, Cranston G. Mutations derepressing silent centromeric domains in fission yeast disrupt chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:218–233. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li F, Goto DB, Zaratiegui M, Tang X, Martienssen R, et al. Two novel proteins, dos1 and dos2, interact with rik1 to regulate heterochromatic RNA interference and histone modification. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1448–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thon G, Hansen KR, Altes SP, Sidhu D, Singh G, et al. The Clr7 and Clr8 directionality factors and the Pcu4 cullin mediate heterochromatin formation in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 2005;171:1583–1595. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.048298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horn PJ, Bastie JN, Peterson CL. A Rik1-associated, cullin-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase is essential for heterochromatin formation. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1705–1714. doi: 10.1101/gad.1328005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jia S, Kobayashi R, Grewal SI. Ubiquitin ligase component Cul4 associates with Clr4 histone methyltransferase to assemble heterochromatin. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1007–1013. doi: 10.1038/ncb1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong EJ, Villen J, Gerace EL, Gygi SP, Moazed D. A Cullin E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Complex Associates with Rik1 and the Clr4 Histone H3-K9 Methyltransferase and Is Required for RNAi-Mediated Heterochromatin Formation. RNA Biol. 2005;2:106–111. doi: 10.4161/rna.2.3.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadaie M, Iida T, Urano T, Nakayama J. A chromodomain protein, Chp1, is required for the establishment of heterochromatin in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2004;23:3825–3835. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neuwald AF, Poleksic A. PSI-BLAST searches using hidden markov models of structural repeats: prediction of an unusual sliding DNA clamp and of beta-propellers in UV-damaged DNA-binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3570–3580. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.18.3570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Irvine DV, Zaratiegui M, Tolia NH, Goto DB, Chitwood DH, et al. Argonaute slicing is required for heterochromatic silencing and spreading. Science. 2006;313:1134–1137. doi: 10.1126/science.1128813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buhler M, Haas W, Gygi SP, Moazed D. RNAi-dependent and -independent RNA turnover mechanisms contribute to heterochromatic gene silencing. Cell. 2007;129:707–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buker SM, Iida T, Buhler M, Villen J, Gygi SP, et al. Two different Argonaute complexes are required for siRNA generation and heterochromatin assembly in fission yeast. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:200–207. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noma K, Sugiyama T, Cam H, Verdel A, Zofall M, et al. RITS acts in cis to promote RNA interference-mediated transcriptional and post-transcriptional silencing. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1174–1180. doi: 10.1038/ng1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmberg C, Fleck O, Hansen HA, Liu C, Slaaby R, et al. Ddb1 controls genome stability and meiosis in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 2005;19:853–862. doi: 10.1101/gad.329905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iida T, Nakayama J, Moazed D. siRNA-mediated heterochromatin establishment requires HP1 and is associated with antisense transcription. Mol Cell. 2008;31:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simmer F, Buscaino A, Kos-Braun IC, Kagansky A, Boukaba A, et al. Hairpin RNA induces secondary small interfering RNA synthesis and silencing in trans in fission yeast. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:112–118. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hampsey M, Reinberg D. Tails of intrigue: phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II mediates histone methylation. Cell. 2003;113:429–432. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00360-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matzke M, Kanno T, Daxinger L, Huettel B, Matzke AJ. RNA-mediated chromatin-based silencing in plants. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Analysis of transcript accumulation from dg sites within the centromere by real time PCR analysis. A. Transcripts from cen dg sequences were measured by real time PCR relative to adh1+ transcript accumulation in cDNA derived from strains listed in Figure 2C (raf1Δ to raf1 +). Duplicate RNA preparations were used to generate duplicate cDNAs and data represent mean ± SEM. B. Centromeric transcripts from the dg region of the centromere were measured by real time PCR of cDNA derived from strains listed in Figure 2E (raf2Δ to raf2 +). Analysis was performed as described above.

(0.01 MB PDF)

Analysis of strains bearing genomic reintegration of dcr1 +. A. Serial dilution assay to monitor growth of cen::ura4 + reporter strains on non-selective media (complete), media lacking uracil (−URA), or media supplemented with FOA (+FOA). Following reintegration of dcr1 + into the genomic dcr1Δ locus, both tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP isolates were able to grow on FOA. Strains used were PY2036, 3310, 3307, 3501, 3502, 3499, 3500. B. Real time PCR analysis of centromeric transcript accumulation from the dh repeat sequences relative to adh1 + transcript accumulation in cDNA derived from the indicated strains. Two independent reintegrants of dcr1 + (dcr1Δ to dcr1 +) were analyzed for both the tas3-TAP and tas3WG-TAP backgrounds. Data represent mean ± SEM for cDNA samples from 2 independent RNA preparations for each strain. Data was normalized to wild type cen::ura4+ strain (PY2036), which was set at 1. Strains used were PY2036, 3310, 3307, 3501, 3502, 3499, 3500. C. Centromeric dg transcripts were measured by similar methods and using the same cDNA samples as used for (B). D. Northern blotting for small RNA species in RNA preparations from the strains listed in (B). Blot was probed for siRNAs derived from dh repeats and for the snoR69 RNA as a loading control.

(0.24 MB PDF)

Analysis of centromeric dg and dh transcript accumulation by real time PCR. A. Real time PCR analysis of dg centromeric transcripts relative to adh1 + in cDNA derived from strains listed in Figure 5C (cid12Δ to cid12 +). Duplicate RNA preparations were used to generate duplicate cDNAs and data represent mean ± SEM. B. Real time PCR analysis of transcripts derived from dg centromeric repeats relative to adh1 + in strains listed in Figure 5E (hrr1Δ to hrr1 +). Analysis was performed as described above.

(0.02 MB PDF)

Analysis of centromeric transcript accumulation in rdp1 null cells and Chp1 association with centromeric dh sequences in hrr1 mutant cells. A. Real time PCR analysis of transcripts derived from dh centromeric repeats relative to adh1 + in strains listed in Figure 6C (rdp1Δ to rdp1 +). Analysis was performed as described in Figure 6C. B. ChIP was performed with Chp1 antibodies on chromatin prepared from strains listed in Figure 6D. Real time PCR was used to quantify Chp1 association with dh relative to the euchromatic adh1 control. Data was normalized to cells lacking clr4 (set at 1), in which Chp1 does not associate with centromeres. Error bars represent the SEM of duplicate ChIPs using different biological samples.

(0.02 MB PDF)

Transient depletion of ago1 + does not affect establishment of silencing of centromeric transcripts in tas3WG cells. A. Real Time PCR analysis of cDNA prepared from indicated strains, measuring centromeric dg transcript accumulation normalized to adh1 + expression. Data represents mean average of analysis of 2 independent cDNA preparations from duplicate biological samples, measuring two independent ago1 + reintegrants for each background, with error bars representing SEM. Strains used were as in Figure 7A.

(0.01 MB PDF)

Strains used in this study.

(0.11 MB DOC)

Oligonucleotide sequences.

(0.06 MB DOC)

Supplemental experimental procedures.

(0.05 MB DOC)