Abstract

Monte Carlo simulations are used to study the effect of spontaneous (intrinsic) twist on the conformation of topologically equilibrated minicircles of dsDNA. The twist, writhe, and radius of gyration distributions and their moments are calculated for different spontaneous twist angles and DNA lengths. The average writhe and twist deviate in an oscillatory fashion (with the period of the double helix) from their spontaneous values, as one spans the range between two neighboring integer values of intrinsic twist. Such deviations vanish in the limit of long DNA plasmids.

Introduction

DNA minicircles are small circular double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) molecules whose length N is of the order of the persistence length of dsDNA, Np = 150 basepairs (bp). DNA minicircles are found in nature or can be produced by covalent cross-linking (ligation) of short linear DNA molecules, a process referred to as cyclization. Their topology is controlled by the linking number Lk, which is the (integer) number of times the two DNA strands wind around each other. While the linking number is a topological invariant that does not change in the process of thermal fluctuations, the process of cyclization of linear DNA results in a distribution of circular DNA molecules with different values of Lk. The shape of the distribution depends on the length of the linear segments and on their elastic properties such as bending and twist rigidities and the presence of spontaneous (intrinsic) curvature and twist, all of which affect the cyclization probability (J factor) (1–4). Topological equilibrium with respect to Lk can be also achieved by the action of topoisomerases and other related enzymes that cut and ligate circular DNA; cutting through a single strand (by topo I) can change the linking number by integer multiples of ΔLk = ± 1 while cutting both strands (by topo II) changes this number by integer multiples of ΔLk = ± 2 (the latter requires ATP; see, e.g., Bates and Maxwell (1)).

Because dsDNA is a double helix, one can define the spontaneous twist (or commonly, the intrinsic twist) of linear DNA as the number of helical periods per chain, Tw(0) = N/h, where h is the number of basepairs per period. While for B-form DNA, under standard conditions (0.2 M NaCl, pH 7, 37°C) h ≃ 10.5 bp and Tw(0) = N/10.5 (1), this value may be reduced or increased by changing temperature (5), ionic strength (6), or by binding of intercalators such as ethidium bromide (7). The fact that this number is not, in general, an integer, does not significantly affect the conformations of large plasmids (e.g., plasmids with Tw(0) = 1000 and those with 1000.5 have similar conformations), but has important consequences for short circular DNA, because of topological constraints imposed by the White-Fuller relation (8,9). According to this relation the linking number can be expressed as the sum of twist Tw and writhe Wr and while both twist and writhe can vary in the process of thermal fluctuations, their sum is a topological invariant (integer). Because for large plasmids both twist and writhe fluctuations are large (in the limit of large N, both twist and writhe can be considered as random variables and the widths of the corresponding Gaussian distributions increase as ), the fact that twist fluctuates about a finite spontaneous value (Tw(0)) rather than about zero does not significantly constrain the statistical properties of the ensemble of conformations of the plasmid. In the case of minicircles, the variances of the twist and the writhe distributions become smaller than unity and the precise value (integer or noninteger) of spontaneous twist has a major effect on the writhe distribution and through it on the three-dimensional conformation of circular DNA.

Early experimental studies of the effects of varying spontaneous twist on the conformations of DNA minicircles utilized the writhe dependence of the electrophoretic mobility of DNA (3,10). More recently, because of the interest in DNA looping as a possible mechanism for control of gene expression, the interest in DNA minicircles arose again in the context of cyclization of short linear DNA (11,12), and the emergence of atomic force microscopy methods to visualize the conformations of minicircles (13,14). On the theoretical side, previous attempts to model miniplasmids were based on the wormlike rod (WLR) model (15–21) of DNA which incorporates 1), the bending and twist degrees of freedom; 2), the intrinsic shape of DNA; and 3), the linking number. In this model dsDNA is described as a continuous elastic ribbon or rod whose edges represent the two DNA strands. In general, the combination of energetic, geometric, and entropic (due to thermal fluctuations) considerations makes the statistical mechanics of closed DNA circles intractable by analytical methods and one has to resort to computer simulations. Such Monte Carlo (MC) simulations were done either directly on the WLR model (22), or by simulating the ensemble of wormlike chains (WLC) with bending rigidity only, assuming a Gaussian form of the twist distribution and combining the two with the help of the White-Fuller relation (4). A purely analytical approach is possible only in the limit of very small minicircles, for which thermal fluctuations about the lowest energy conformation become negligible and the calculation reduces to the analysis of lowest energy states (23,24).

In this article, we present a MC simulation study of the effects of spontaneous twist on the conformations of DNA minicircles in topological equilibrium, which does not conserve their linking number (for example, in the presence of topo I). In next section, we introduce the wormlike rod model of DNA and define the twist, writhe, and linking numbers. In General Considerations and Plan of Work, we present a qualitative discussion of effects of integer and noninteger spontaneous twist on the twist and writhe distributions of the WLR model of circular DNA. In Results and Analysis, we present our simulation results. We first explore the effects of having integer or noninteger spontaneous twist on the writhe and twist distributions of DNA minicircles. We study the difference between changing the local spontaneous twist angle at fixed chain length, and varying the number of basepairs at fixed spontaneous twist angle. Finally, we study the effect of spontaneous twist on the distribution of the radius of gyration and discuss the connection between the results for the writhe and the radius of gyration distributions. In Summary, we summarize the results of this work and discuss its limitations.

The Wormlike Rod Model

The wormlike rod model (WLR) for dsDNA describes the dsDNA molecule as an elastic rod, with both bending and twist rigidities (25). In the case where the molecule has spontaneous twist, the energy is given by

| (1) |

where lp is the bending persistence length, l3 is the twist persistence length, κ(s) is the curvature at distance s along the rod, and δω3(s) ≡ ω3(s) – ω3(0) is the deviation of the local rate of twist from its spontaneous value. A detailed description of the model and of its discretized form, is given in the Supporting Material. We just note here a few key formulae. The discrete energy functional takes the form

| (2) |

Here, are dimensionless bending and twist persistence lengths, respectively, and

is the dimensionless curvature defined by θn,n+1, the bending angle between the nth and the (n + 1)th segments. is the difference between the twist angle (as defined in the Appendix of Medalion et al. (21)) and the spontaneous twist angle.

The above description of the WLR model is valid for arbitrary (linear or circular) polymer topology. For closed (circular) macromolecules, the model has to be supplemented by two constraints: 1), the chain closure constraint, r(s + L) = r(s); and 2), the periodicity constraint that ensures that the cross-sectional plane of the WLR rotates an integer number of times around the centerline. This integer number, known as the linking number (Lk), is in fact defined for every two closed curves in three dimensions and describes the number of times one curve directionally intersects the plane inscribed by the other curve. According to the well-known White-Fuller theorem (8,9) for two infinitesimally close curves, Lk can be expressed as the sum of writhe (Wr) and twist (Tw),

| (3) |

The definitions of Wr and Tw are given in the Supporting Material.

General Considerations and Plan of Work

Of particular interest to us will be the distributions for Tw and Wr. At first sight, it would appear that the twist distribution for the model with spontaneous twist is completely equivalent to that without, apart from a trivial shift Tw → Tw − Tw(0), where . However, this is not true due to the White-Fuller relation and the constraint that Lk is an integer. Consider what happens when the length N of the plasmid is changed for a given value of (or when we change at fixed N). If Tw(0) is an integer, the model yields the same results, up to the trivial shift, as the WLR model without spontaneous twist. On the other hand, when Tw(0) has a fractional part, interesting effects arise.

For DNA minicircles (L/lp of the order of unity), bending rigidity suppresses the fluctuations about the lowest energy, planar-ring configuration, and the writhe distribution is narrowly peaked about zero. Without spontaneous twist (or when the Tw(0) takes an integer value), one can minimize the bending and twist energies and satisfy the constraint of integer linking number by having Wr = Tw = 0 (up to small deviations). However, when Tw(0) is not an integer, the conflicting demands of minimizing the bending energy (Wr = 0) and the twist energy (Tw = Tw(0)) cannot be simultaneously satisfied because the sum Wr + Tw must be an integer. Consequently, both Wr and Tw will deviate from their spontaneous values (the precise partitioning of Lk into Tw and Wr depends on the ratio of the bending and twist rigidities and on the length of the minicircle). In particular, in the case when the fractional part of the Tw(0) is very close to 1/2, a degenerate situation arises because Tw can change in either direction and thus one expects two peaks in the Tw distribution, at symmetric positions about Tw(0). Similarly, the Wr distribution should also have two complementary peaks. As the plasmid increases in length, the Tw distribution broadens, and these effects are progressively washed out. Thus, for very long chains, the effects of spontaneous twist are negligible.

Results and Analysis

We performed Monte Carlo simulations to measure the effect of spontaneous twist on DNA minicircles. The basic algorithm is similar to that employed in our earlier study of the spontaneous twist free case, and the details are presented in the Supporting Material. We first discuss the writhe and twist distributions and then consider the radius of gyration.

Writhe and twist distributions

To examine the effects of spontaneous twist on the statistical properties of DNA minicircles (using dsDNA parameters lp = 50 nm and l3 = 74 nm), we changed the total spontaneous twist, Tw(0), by varying the spontaneous twist angle () or by changing the DNA length (N). In the first case we simulated a closed WLR of fixed length (180 bp) and changed the spontaneous twist angle, , between 0.595 rad and 0.627 rad, corresponding to total spontaneous twist in the interval 17.04–17.96. Such slight changes in the helical repeat can be caused, for example, by a change of temperature, addition of monovalent salt, or of intercalating dyes such as ethidium bromide and chloroquine (see Section II of Bates and Maxwell (1) and references therein). In the second case, the spontaneous twist angle , corresponding to a single helical turn every 10.45 bp for B-form DNA, was kept constant, and Tw(0) was varied by changing the DNA length by adding basepairs (note that if the total length is not equal to an integer number of helical repeats, Tw(0) is not an integer). We ran simulations for dsDNA lengths of 237–258 bp. Note that because the variances of the twist and the bending distributions depend on the length of the polymer even in the absence of spontaneous twist, changing the number of basepairs affects these distributions in a complex way, and not only through the change of the total spontaneous twist. These effects will be discussed at length later on in this article.

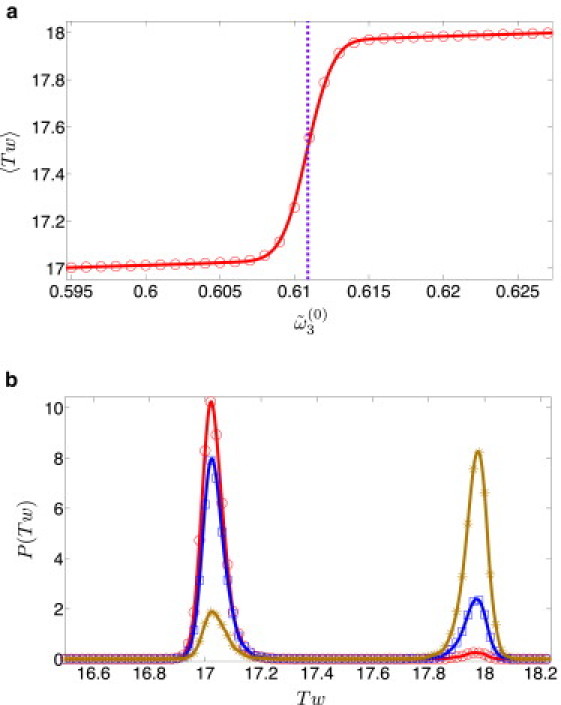

We begin with the fixed length case and examine the effect of changing the total spontaneous twist at fixed DNA length (180 bp). In Fig. 1 a, one observes a sharp transition of the mean twist 〈Tw〉 of the DNA ring from a value very close to an integer, to another value close to the next integer. This transition occurs when the fractional part of Tw(0) is very close to 1/2. For small DNA rings, the writhe is very small and twist is slaved to linking number and follows its behavior. Before and after the transition, the (discrete) linking number distribution is dominated by a single peak at some integer value of Lk (Lk = 17 and 18, respectively). This behavior is followed by the twist distribution which also exhibits a single peak close to an integer value of Tw (because Tw is a continuous variable, the peak has a finite width due to broadening by writhe fluctuations). During the transition, on the other hand, there are two possible Lk values and thus two finite peaks (at Lk = 17 and 18) in the discrete Lk distribution. In this range, the mean linking number 〈Lk〉 is the weighted sum of two successive integers and therefore is not an integer. The relative weights of the two peaks in the Lk distribution change as one traverses the transition region, accompanied by a corresponding change of the weight of the two peaks in the Tw distribution, which is clearly observed in Fig. 1 b (as expected, the positions of the peaks do not change during the transition).

Figure 1.

(Color online) A dsDNA plasmid of length N = 180 bp (lp = 50 nm and l3 = 74 nm). (a) 〈Tw〉 vs. in the range 0.595–0.627 rad (the vertical violet dashed line corresponds to Tw(0) = 17.5). (b) P(Tw) for (red circles), (blue squares), and (brown asterisks). Solid lines are guides to the eye.

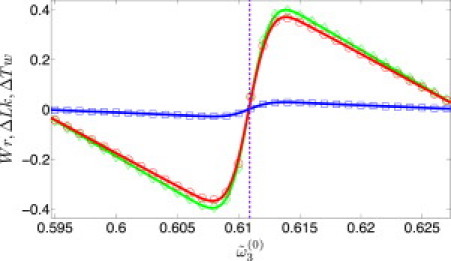

In Fig. 2 we present the mean deviations of the twist, linking number, and writhe,

respectively (note that Wr(0) = 0 and thus Lk(0) = Tw(0)), as a function of for a DNA plasmid of 180 bp. The transitions take place around half-integer values of Tw(0), and between two successive transitions, both 〈ΔTw〉 and 〈ΔLk〉 decrease linearly with , due to the linear dependence of these averages on the variable Tw(0). While both 〈Tw〉 and 〈ΔLk〉 change by a factor close to unity around the transition (from minimum to maximum), 〈Wr〉 experiences much more modest deviations from zero, as expected for dsDNA minicircles, and always makes only a minor contribution to the linking number. Even during the transition, when the writhe distribution has two peaks corresponding to the two different linking numbers, these peaks are very close to zero and strongly overlap (Fig. 1 in the Supporting Material), so effectively this case could be considered as the broadening of a single narrow peak of this distribution about Wr = 0.

Figure 2.

(Color online) N = 180 bp with dsDNA parameters ( and ): 〈ΔTw〉 (red circles), 〈ΔLk〉 (green diamonds), and 〈Wr〉 (blue squares) for s in the range 0.595–0.627 rad (vertical dashed line is the corresponding to Tw(0) = 17.5). Solid lines are guides to the eye.

When the length of DNA is varied at fixed spontaneous twist angle, in addition to the linear change of total spontaneous twist, one must also consider the effect of chain length on the amplitude of Tw and Wr fluctuations. In Fig. 3 we show the dependence of the variance of the writhe distribution, 〈Wr2〉 – 〈Wr〉2, on DNA length N. We expect the mean 〈Wr〉 to vanish both for N/Np << 1 and for N/Np >> 1 (Np = 150 bp corresponds to the persistence length of dsDNA); the second moment of the distribution, 〈Wr2〉, is expected to vanish in the short chain limit (the distribution approaches a δ-function) and to increase linearly with N for long chains (26). These expectations are confirmed by our simulations and we find that the crossover between the two asymptotic regimes takes place at ∼5 Np (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

(Color online) The variance of P(Wr) in the absence of spontaneous twist as a function of chain length (violet points). The value lp is 50 nm, and l3 is 74 nm as in the case of dsDNA. (Red dashed line) Linear fit to the variance in the long chain limit.

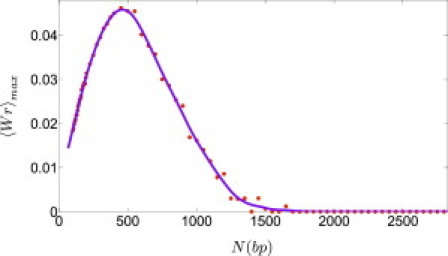

To get a feeling about how the magnitude of writhe varies with DNA length, we used the factorization approximation (see the Supporting Material) and ran simulations of WLC with bending but not twist rigidity, in the length range of 150–3450 bp (here we used a segmentation of 1 segment = 5 bp). For each value of N we calculated 〈|Wr|〉 as a function of the spontaneous twist angle and found the maximal value of the mean writhe for this chain length. As can be observed in Fig. 4, 〈|Wr(N)|〉max appears to vanish both in the short and the long chain limits and has a maximum at N ≃ 500. Clearly, in the limit of small plasmids, N/Np << 1, bending rigidity makes the energy cost of deviations from the lowest-energy, planar-circle configuration prohibitively large, and both the mean and the width of the writhe distribution go to zero. In the opposite limit of N/Np >> 1, the writhe distribution broadens and its width becomes much larger than 1 (the unit interval between two successive linking numbers). In this limit, for any value of Tw, one can find a large number of configurations with writhe that completes this value to the nearest integer linking number. In between the two limits, there is a competition between bending energy that favors conformations with small writhe and twist energy that favors Tw = Tw(0); the coupling of the two by the White-Fuller relation Wr + Tw = Lk (9) results in the maximum in 〈|Wr(N)|〉max observed in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

(Color online) Plot of 〈|Wr|〉max as a function of N (using WLC simulations and the factorization approximation described in the Supporting Material, with lp = 50 nm and l3 = 74 nm). Solid lines are guides to the eye.

Consider now the N-dependence of the twist distribution function. Just like the case of short DNA plasmids shown in Fig. 2, we still get oscillatory behavior of 〈ΔTw〉 with steep transitions at values of N for which the fractional part of the Tw(0) approaches 1/2. The amplitude of these oscillations is expected to become vanishingly small in the limit N/Np >> 1 (not shown).

Because the interplay between twist and writhe degrees of freedom depends on the ratio of the bending and twist rigidities, we proceeded to examine the effects of higher twist rigidity by keeping lp = 50 nm and varying l3. As l3 increases, the energy cost for even small deviations of the twist from its spontaneous value, Tw(0), becomes progressively more expensive, and the chain prefers to convert more of its ΔLk into Wr instead of into ΔTw. The detailed behavior depends on the value of Tw(0) and different phenomena are observed for integer and half-integer values of spontaneous twist.

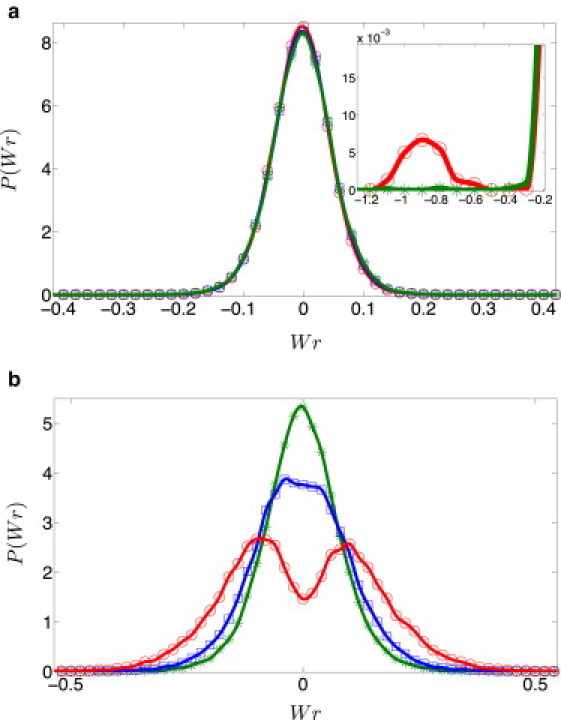

In Fig. 5 a we examine the effect of increasing twist rigidity on the writhe distribution for (nearly) integer spontaneous twist, Tw(0) = 24.019 (N = 251 bp). For relatively low values of twist rigidity (close to that of native dsDNA), a single narrow peak at Wr = 0 is observed, corresponding to Lk = 24. As twist rigidity increases, the amplitude and the width of this peak decrease and two satellite peaks appear at Wr ≃ ±1, corresponding to Lk = 23 and 25, and the amplitude of these peaks increases with increasing l3. While the satellite peaks are too small to be observed for DNA parameters (), they become observable at higher twist rigidities (see inset in Fig. 5 a where the peak about Wr = –1 is shown for ). The physical mechanism that leads to the appearance of satellite peaks has been discussed in detail in Medalion et al. (21). When Tw(0) is an integer, the linking number distribution of topologically relaxed DNA rings contains a large peak at Lk = Tw(0) and a sequence of satellite peaks at neighboring integer values of the linking number Lk = Tw(0) ± 1, Tw(0) ± 2, etc. (the distribution is symmetric about Lk = Tw(0)). The amplitude of the satellite peaks decreases rapidly with distance from Tw(0) and, because the width of the writhe distribution increases with increasing N (roughly as N1/2), only two such peaks are observed for sufficiently small plasmids (for L/lp ∼ O(1); see Fig. 4 b in (21)). For sufficiently small chain lengths and sufficiently large twist rigidity, one reaches the range in which the width of the twist distribution becomes much smaller than unity and the two satellite peaks are dominated by writhe (with ΔTw ≃ 0 and Wr ≃ ±1), as observed in Fig. 5 a.

Figure 5.

(Color online) P(Wr) for different twist rigidities: (green asterisks), 2 (blue squares), and 3, (red circles), where lp = 50 nm. (a) N = 251 bp (Tw(0) = 24.019). Even though the distributions for the above three cases are nearly indistinguishable, a small satellite peak can be observed for (an amplified image of one of the satellite peaks is shown in the inset). (b) N = 256 bp (Tw(0) = 24.49). Progressive splitting of the central peak into two distinct peaks with increasing is clearly observed. Solid lines are guides to the eye.

In Fig. 5 b we consider the effect of twist rigidity on the writhe distribution of plasmids with half-integer spontaneous twist Tw(0) = 24.497 (N = 256 bp) and different values of . Whereas for dsDNA parameters () there is a single peak of P(Wr) at Wr = 0, increasing causes the distribution to become broader until it splits into two distinct peaks that move away from one another with increasing , toward the limiting values of ±0.5 that complete the half-integer value of Tw(0) to the two closest integers. Recall that the two overlapping peaks corresponding to two neighboring Lk values were present even in the case of DNA, , but that they could not be resolved due to the large overlap between them (Fig. 2 b in the Supporting Material).

Radius of gyration

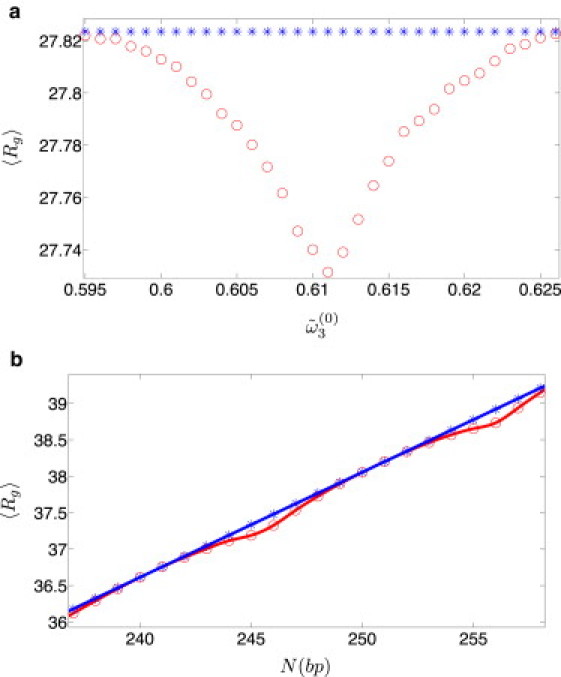

Both writhe Wr and radius of gyration Rg are measures of the three-dimensional conformations of DNA minicircles and thus, we expect these properties to be correlated. Because, for parameter values typical of dsDNA, the effect of spontaneous twist on the writhe was rather small, one expects only modest effects of spontaneous twist on the radius of gyration as well. Keeping N constant and changing the spontaneous twist angle results in slight decrease of the mean radius of gyration 〈Rg〉 (compared to the case without spontaneous twist), when Tw(0) deviates from an integer (Fig. 6 a); as expected, the largest deviation occurs when the fractional part of the Tw(0) approaches 1/2. When Tw(0) is an integer, spontaneous twist does not affect DNA conformations, and 〈Rg〉 coincides with its zero spontaneous twist value. If the spontaneous twist angle is fixed at a value characteristic of native dsDNA and Tw(0) is varied by changing N, oscillations of 〈Rg〉 with N are observed, with periodicity coinciding with the helical repeat of dsDNA (Fig. 6 b). Note that the values of 〈Rg〉 are limited from above by the line corresponding to the zero spontaneous twist case, 〈Rg〉 ∝ N (for short polymers, linear increase of 〈Rg〉 with chain length is expected). This concurs with the expectation that the presence of noninteger spontaneous twist forces the writhe of small plasmids to deviate from zero, resulting in more compact DNA configurations and therefore in smaller 〈Rg〉.

Figure 6.

(Color online) Effect of spontaneous twist on Rgrms of DNA minicircles (lp = 50 nm and l3 = 74 nm). (a) Constant length (N = 180 bp) with varying in the range 0.595–0.626 rad (violet circles). (b) Constant with N varying in the range 237–258 bp (violet circles). In both graphs, the case is shown by blue asterisks. Solid lines are guides to the eye.

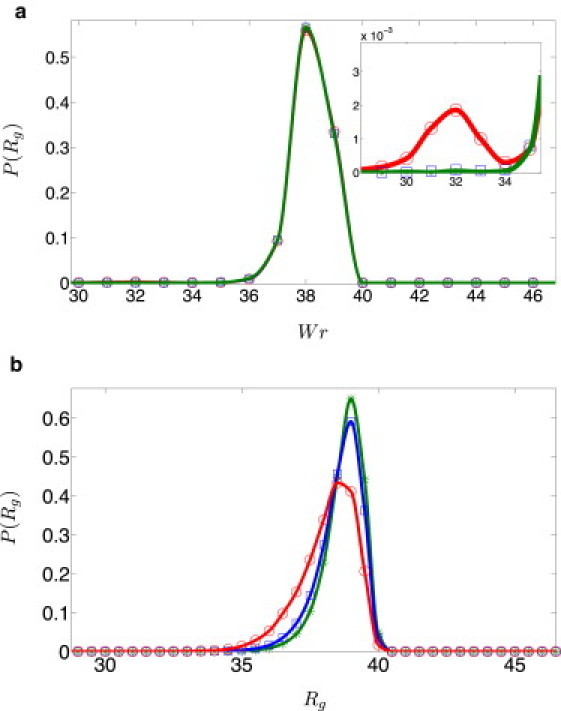

The effects of spontaneous twist on the distribution of radii of gyration P(Rg) of small plasmids can be amplified by increasing the twist rigidity. While for DNA parameters, only a single peak of P(Rg) is observed for all values of Tw(0), the distinction between integer and half-integer values of Tw(0) becomes apparent at larger values of l3. Inspection of Fig. 7 a shows that for integer Tw(0) (N = 251 bp), a single peak of P(Rg) is observed at the value of l3 that corresponds to native dsDNA. While, at first glance, increasing l3 appears to have no effect on the distribution, closer inspection (see inset of Fig. 7 a) reveals that already for another small peak in P(Rg) appears, at a lower Rg value. This peak is produced by the same mechanism that led to the appearance of the satellite peaks in the Wr distribution at higher values of l3 (Fig. 5 a), and is the consequence of the twist-rigidity-induced broadening of the linking number distribution and the appearance of additional peaks at higher |Lk| values; as one increases l3, satellite peaks appear at Wr = ±1 and one concludes that plectonemic conformations with |Wr| = 1 become increasingly important. Because such conformations are more compact than those corresponding to the central peak at Wr = 0, the probability to observe conformations with larger Rg (Wr ≃ 0) decreases, and those with smaller Rg (|Wr| ≃ ±1) increases with increasing twist rigidity.

Figure 7.

(Color online) P(Rg) for Np = 150 bp and different twist rigidities (green asterisks), (blue squares), and (red circles). (a) N = 251 bp (Tw(0) = 24.0191). Solid lines are guides to the eye. (Inset) Magnified view of the new peak at . (b) N = 256 bp (Tw(0) = 24.497).

When the fractional part of Tw(0) is close to 1/2 (for N = 256 bp), the main effect of increasing l3 is to shift the single peak in P(Rg) to lower values of Rg (this translation saturates in the high limit) and to make it more symmetric. The reason for this behavior becomes clear if we examine the corresponding writhe distributions (see Fig. 5 b). Note that, in this case, there is a single peak of P(Wr) around Wr ≃ 0 for DNA parameters (). As l3 is increased, this peak splits into two peaks centered at ±Wrpeak (the two peaks correspond to the integers Lk = Tw(0) ± 1/2). At yet higher values of twist rigidity, twist fluctuations about Tw(0) are suppressed and |Wrpeak| approaches 1/2. Because conformations differing only in the sign of writhe have the same radius of gyration, we expect to see a single peak in P(Rg), which moves to lower values of Rg and eventually is pinned down at some value of the radius of gyration, with increasing l3. Comparison of the inset of Fig. 7, panel a with panel b, shows that for , the most probable value of Rg for the N = 256 bp minicircle (that corresponds to 0 < |Wr| < 1/2) is higher than the value of Rg at the small peak for the N = 251 bp case (that corresponds to |Wr| ≃ ±1), in agreement with the expectation that higher writhe yields more compact DNA conformations.

Summary

To study the effect of spontaneous twist on the conformations of DNA minicircles, we carried out MC simulations of closed wormlike rods with length comparable to the persistence length of DNA. We examined the variation of the twist and writhe distributions with spontaneous twist, as the latter takes integer and noninteger values, by varying the spontaneous twist angle and the number of basepairs (within a period of the double helix). In agreement with the literature (4,13), the largest differences were observed to be between integer and half-integer values of spontaneous twist, reflecting the fact that while in the former case the only contribution comes from Lk = Tw(0), in the latter case the two neighboring linking numbers, Lk = Tw(0) ± 1/2 contribute to the observed distributions and their moments. Oscillatory dependence of 〈Tw〉 – Tw(0), 〈Wr〉, and of 〈Rg〉 on spontaneous twist (as it changes between two adjacent integers) is observed for small minicircles. The amplitude of the effect depends on DNA length; it first increases to a maximum at N of approximately three persistence lengths of DNA and then decays rapidly to zero at higher (of ∼10 Np) DNA lengths. Our results concur with the conclusion of previous studies that plectonemic conformations make a negligible contribution to DNA minicircles. Nevertheless, we were able to generate such conformations at higher values of l3, which suggests that they could be reached experimentally as well, provided that one could increase the twist rigidity of DNA minicircles; e.g., by binding of proteins.

Finally, we would like to comment on the limitations of this work. While excluded volume effects and knot formation were not taken into consideration, such effects are expected to play a minor role for minicircles and should not affect our results. A more important limitation comes from the fact that the use of coarse-grained elastic models of DNA becomes questionable for very short (and for highly under/overwound) DNA molecules where the details of microscopic structure become increasingly important and one has to resort to atomistic simulations (27). In particular, one may wonder whether the White-Fuller relation, originally derived to infinitely thin filaments, is valid for short DNA minicircles. Because the thickness of the DNA molecule is ∼2 nm and the shortest chains we examined are 180 bp (i.e., ∼60 nm) long, this gives a ratio of 1:30 between the thickness and the contour length, suggesting that these chains are still well in the range of very thin filaments, and the expected deviations from the slender rod limit are small.

Acknowledgments

Y.R. acknowledges stimulating discussions with Alexander Vologodskii, Steven Levene, Jonathan Widom, John Marko, and Thomas Witten. We thank Dan Major for allowing us use of his cluster for our simulations.

This work was supported by grants from the Israel Science Foundation and the Israel-France Research Networks Program in Biophysics and Physical Biology, and by the Materials Research Science and Engineering Center program of the National Science Foundation No. DMR-0520513 at Northwestern University.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Bates A.D., Maxwell A. 2nd Ed. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2005. DNA Topology. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shore D., Langowski J., Baldwin R.L. DNA flexibility studied by covalent closure of short fragments into circles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:4833–4837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shore D., Baldwin R.L. Energetics of DNA twisting. I. Relation between twist and cyclization probability. J. Mol. Biol. 1983;170:957–981. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levene S.D., Crothers D.M. Topological distributions and the torsional rigidity of DNA. A Monte Carlo study of DNA circles. J. Mol. Biol. 1986;189:73–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90382-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duguet M. The helical repeat of DNA at high temperature. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:463–468. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.3.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rybenkov V.V., Vologodskii A.V., Cozzarelli N.R. The effect of ionic conditions on DNA helical repeat, effective diameter and free energy of supercoiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1412–1418. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.7.1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang J.C. The degree of unwinding of the DNA helix by ethidium. I. Titration of twisted PM2 DNA molecules in alkaline cesium chloride density gradients. J. Mol. Biol. 1974;89:783–801. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White J.H. Self-linking and the Gauss integral in higher dimensions. Am. J. Math. 1969;91:693–728. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuller F.B. The writhing number of a space curve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1971;68:815–819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horowitz D.S., Wang J.C. Torsional rigidity of DNA and length dependence of the free energy of DNA supercoiling. J. Mol. Biol. 1984;173:75–91. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cloutier T.E., Widom J. DNA twisting flexibility and the formation of sharply looped protein-DNA complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:3645–3650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409059102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du Q., Vologodskaia M., Vologodskii A. Gapped DNA and cyclization of short DNA fragments. Biophys. J. 2005;88:4137–4145. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.055657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fogg J.M., Kolmakova N., Zechiedrich E.L. Exploring writhe in supercoiled minicircle DNA. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2006;18:S145–S159. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/18/14/S01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witz G., Rechendorff K., Dietler G. Conformation of circular DNA in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;101:148103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.148103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marko J.F., Siggia E.D. Bending and twisting elasticity of DNA. Macromolecules. 1994;27:981–988. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moroz J.D., Nelson P. Torsional directed walks, entropic elasticity, and DNA twist stiffness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:14418–14422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fain B., Rudnick J., Ostlund S. Conformations of linear DNA. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip. Topics. 1997;55:7364–7368. doi: 10.1103/physreve.60.7239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vologodskii A.V., Marko J.F. Extension of torsionally stressed DNA by external force. Biophys. J. 1997;73:123–132. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78053-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouchiat C., Mezard M. Elasticity model of a supercoiled DNA molecule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998;80:1556–1559. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panyukov S.V., Rabin Y. On the deformation of fluctuating chiral ribbons. Europhys. Lett. 2002;57:512–518. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medalion S., Rappaport S.M., Rabin Y. Coupling of twist and writhe in short DNA loops. J. Chem. Phys. 2010;132:045101. doi: 10.1063/1.3298878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katritch V., Vologodskii A. The effect of intrinsic curvature on conformational properties of circular DNA. Biophys. J. 1997;72:1070–1079. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78757-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furrer P.B., Manning R.S., Maddocks J.H. DNA rings with multiple energy minima. Biophys. J. 2000;79:116–136. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76277-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coleman B.D., Swigon D., Tobias I. Elastic stability of DNA configurations. II. Supercoiled plasmids with self-contact. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip. Topics. 2000;61:759–770. doi: 10.1103/physreve.61.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marko J.F., Siggia E.D. Stretching DNA. Macromolecules. 1995;28:8759–8770. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kholodenko A.L., Vilgis T.A. Path integral calculation of the writhe for circular semiflexible polymers. J. Phys. Math. Gen. 1996;29:939–948. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris S.A., Laughton C.A., Liverpool T.B. Mapping the phase diagram of the writhe of DNA nanocircles using atomistic molecular dynamics simulations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:21–29. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.