Abstract

Proteins of the Lsm family, including eukaryotic Sm proteins and bacterial Hfq, are key players in RNA metabolism. Little is known about the archaeal homologues of these proteins. Therefore, we characterized the Lsm protein from the haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii using in vitro and in vivo approaches. H. volcanii encodes a single Lsm protein, which belongs to the Lsm1 subfamily. The lsm gene is co-transcribed and overlaps with the gene for the ribosomal protein L37e. Northern blot analysis shows that the lsm gene is differentially transcribed. The Lsm protein forms homoheptameric complexes and has a copy number of 4000 molecules/cell. In vitro analyses using electrophoretic mobility shift assays and ultrasoft mass spectrometry (laser-induced liquid bead ion desorption) showed a complex formation of the recombinant Lsm protein with oligo(U)-RNA, tRNAs, and an small RNA. Co-immunoprecipitation with a FLAG-tagged Lsm protein produced in vivo confirmed that the protein binds to small RNAs. Furthermore, the co-immunoprecipitation revealed several protein interaction partners, suggesting its involvement in different cellular pathways. The deletion of the lsm gene is viable, resulting in a pleiotropic phenotype, indicating that the haloarchaeal Lsm is involved in many cellular processes, which is in congruence with the number of protein interaction partners.

Keywords: Nucleic Acid, Protein-Nucleic Acid Interaction, RNA, RNA-binding Protein, RNA-Protein Interaction, Hfq, Lsm, Sm, Archaea, Small RNAs

Introduction

Sm and Sm-like (Lsm) proteins constitute a large family of proteins known to be involved in RNA metabolism. Representatives of this family are found in all three domains: bacteria, archaea, and eukarya. All of them share a common bipartite sequence motif, known as the Sm domain, consisting of two conserved segments separated by a region of variable length and sequence. The bacterial family member is the Hfq protein (1, 2), which has a plethora of functions (3). Hfq is a highly conserved protein encoded within many bacterial genomes (4). Although the protein does not show a high similarity to the Lsm proteins on the primary structure level, it possesses striking similarities in both function and tertiary and quaternary structure to the eukaryotic Lsm proteins (3, 5). Hfq monomers assemble to form highly stable hexamers (6), which bind preferentially to A/U-rich sequences (7, 8) but have a relaxed RNA binding specificity and participate in many stages of RNA metabolism. It was therefore proposed that Hfq is an ancient, less specialized form of the Lsm proteins (9). One of the identified functions of Hfq is its interaction with sRNAs (10). It has been proposed that the protein acts as an RNA chaperone that might simultaneously recognize the sRNA and its target and facilitate its interaction. An Escherichia coli hfq insertion mutant showed pleiotropic phenotypes including decreased growth rates and yields, increased cell sizes, and an increased sensitivity to stress conditions (11–13). These defects are at least in part a reflection of the fact that Hfq is required for the function of several sRNAs including DsrA, RprA, Spot42, OxyS, and RhyB (14–17).

Eukaryotes have the most diverse members of the Sm/Lsm protein family. They contain at least 18 different Sm and Lsm proteins involved in mRNA splicing, histone maturation, telomere maintenance, and mRNA degradation that form at least six different heteroheptameric complexes (18). The Lsm proteins alone form at least two heteroheptameric complexes: the nuclear Lsm2-8, a large fraction of which associates with U6 snRNA,2 and the cytoplasmic Lsm1-7, which functions in mRNA degradation (19, 20). The Lsm proteins that associate with U6 snRNA are necessary for its stability (21–23), binding to the U-rich region at the 3′ end of the U6 snRNA. Additional functions of the nuclear Lsm proteins are the involvement in processing pre-snoRNA, pre-rRNA, pre-tRNA precursor, and nuclear pre-mRNA decay (5).

The fact that Lsm proteins have been found in archaea (22–25) suggests that they were present in a common ancestor shared by archaea and eukarya. This correlates with the observation that several eukaryotic proteins clearly evolved from archaea-related precursors (26) and that snoRNAs have also been found in archaea (27). Some archaea, such as the Pyrococcus species and halophilic archaea, encode only one Lsm protein (Lsm1), whereas others encode two (Lsm1 and Lsm2) (23). The Lsm1 and Lsm2 proteins have been shown to be associated in vivo (28), so they might also form heteromeric complexes. Crenarchaeota have an additional Lsm protein, Lsm3, which contains a traditional Sm domain fused to a second domain by a flexible linker (29, 30).

The archaeal Lsm1 proteins have been shown to form heptamers (28, 31–33) and bind RNA (18, 28, 31). The Lsm2 protein from Archaeoglobus fulgidus has been reported to form a hexameric (34) or a heptameric (31) complex. The Lsm3 protein has also been shown to form 14-mer complexes (30), a process of which some of the Lsm1 proteins are also capable (35).

Interestingly, Methanocaldococcus jannaschii lacks a classical Lsm gene (9, 36) but contains an Hfq-like protein. Although some data have been acquired on the structure and RNA binding characteristics of the archaeal Lsm protein, so far the function and interaction partners of the Lsm protein in archaea have not been revealed.

Here, we analyze the Lsm protein from the halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii. H. volcanii encodes only one Lsm protein, which makes it easier to employ genetic methods for analyzing the biological function of the archaeal Lsm proteins. Recently, it has been shown that H. volcanii also has an sRNA population potentially involved in gene expression regulation (37, 38). To investigate whether the Haloferax Lsm is involved in sRNA regulation and to clarify its biological function, we generated a deletion strain for Lsm and analyzed the in vivo and in vitro function of this protein.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and Culture Conditions

H. volcanii strains H119 (ΔpyrE2, ΔtrpA, ΔleuB) (39) and Δlsm (ΔpyrE2, ΔtrpA, ΔleuB, Δlsm) were grown aerobically at 45 °C in Hv-YPC or Hv-Ca medium (39). The term “normal growth conditions” for H. volcanii used here stands for aerobic growth at 45 °C and 2.1 m NaCl.

Generation of the pTA927 Vector

To generate pTA927, a 131-bp KpnI fragment containing the terminator sequence of the H. volcanii L11e rRNA gene (40) was inserted at the KpnI site of pTA230 (39). Next, a 224-bp region of the tnaA promoter (41) was amplified by PCR and inserted at the ApaI and ClaI sites; the reverse primer incorporated a novel NdeI site (at the ATG start codon) for cloning the regulatable gene. Finally, a synthetic transcription terminator sequence (5′-GGCCGCACCTCTGGACCATCGCATTTTTCGGCGCG-3′) was inserted downstream between the NotI and BstXI sites. The sequence of pTA927 is available upon request.

Isolation and Analysis of RNA

Total RNA was isolated according to Chomczynski and Sacchi (42). For Northern blot analysis the aliquots were separated on formaldehyde-containing agarose gels, transferred to nylon membranes by downward capillary blotting, and UV cross-linked. Digoxigenin-labeled DNA probes were synthesized as described (43). Digoxigenin-dUTP was purchased from Roche Applied Science. After hybridization using standard stringency conditions (50% formamide, 50 °C), the membrane was washed successively in 2× SSC, 0.1% SDS at room temperature and 1× SSC, 0.1% SDS at 50 °C. Detection of digoxigenin-labeled probes was performed as described (44).

For the analysis of 5′ and 3′ ends of the lsm transcript, the circularized RNA RT-PCR approach was used (45). First, total RNA was circularized with RNA ligase. Then a gene-specific cDNA was generated using a primer specific for the lsm ORF. The DNA was amplified by a PCR and a subsequent nested PCR using four primers specific for the ORFs of the lsm and the l37e genes. The PCR product was purified and sequenced, and the comparison of the sequence with the H. volcanii genome allowed the identification of the 5′ and 3′ ends of the transcript.

Production of the Haloferax Lsm Protein in E. coli and Generation of Antibodies

The lsm gene sequence was taken from HaloLex (46). Chromosomal DNA from H. volcanii was isolated using the alternative rapid chromosomal isolation method as published in the Halohandbook (75). The reading frame of the Lsm protein was amplified from Haloferax genomic DNA using primers Sm1 (primer sequences are available upon request) and Sm2, which contained the restriction sites NcoI and NotI, respectively. The resulting PCR product was digested with NcoI and NotI and cloned into the vector pET29a (Novagen), which was previously digested with the same restriction enzymes, yielding the plasmid pET29a-Sm. pET29a-Sm was transformed into Bl21-AI (Novagen), and the Lsm protein was expressed and purified according to the manufacturer's protocol using S-protein-agarose (Novagen). For the production of antibodies, 0.5 mg of purified protein were sent to Davids Biotechnology (Regensburg, Germany).

Western Blot Analysis and Determination of Lsm Copy Number

For Western blot analysis cytoplasmic extracts of H. volcanii (20 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nylon membrane by semi-dry blotting (1.5 h with 2 mA/cm2). The membrane was blocked using skimmed milk powder, incubated with the newly generated antiserum (see above) or the preimmune serum at dilutions of 1:500, washed, and incubated with the secondary, peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody. Peroxidase activity was detected with the chemiluminescence substrates luminol and para-hydroxycoumaric acid. Light emission was detected with films. The generated antiserum reacted with several bands, all but one of which also reacted with the preimmune serum. The specific band had the expected size of ∼9 kDa.

For the quantification of the Lsm copy number, cytoplasmic extracts were prepared of 2.3 × 108 H. volcanii cells. They were used for Western blot analysis alongside with 1–50-ng aliquots of purified Lsm protein. The film was scanned, and the signals were quantified using ImageJ. The aliquots of the purified Lsm protein were used to generate a standard curve, which was used to quantify the Lsm amount in cell extracts. The value was used to calculate the Lsm molecules/cell using a molecular mass of 8.25 kDa.

Substrate Preparation and Binding of the Recombinant Protein to RNA

Substrates for the electrophoretic mobility shift assays were prepared as follows. U15- and U30-RNA oligonucleotides were generated by Sigma. Wheat tRNA (tRNA isolated from wheat germ, type V; Sigma) and oligo(U)-RNA were labeled at the 3′ end using [α-32P]pCp as described (47). EMSAs were carried out as described (48) with the following modifications: 100 ng of recombinant Lsm protein was used if not indicated otherwise. For the determination of the dissociation constant of Lsm/oligo(U)-RNA (KD), 0.1 pmol (0.6 ng) of U15-RNA were incubated with increasing amounts of Lsm protein (0.012–24 pmol, equating 0.1–200 ng). If all of the proteins are present as homoheptameric complexes, 0.1–200 ng of protein would equate to 1.7 fmol–3.4 pmol of Lsm complexes.

Laser-induced Liquid Bead Ion Desorption-MS

LILBID is a novel mass spectrometry method that allows an exact mass determination of single macromolecules dissolved in droplets of solution containing an adequate buffer, pH, ion strength, etc., as described previously (49). Briefly, droplets of solution of analyte are ejected by a piezo-driven droplet generator and transferred into a high vacuum. There, they are irradiated droplet by droplet (d = 50 μm, V = 65 pl, 10 Hz) by a pulsed IR laser tuned to the stretching vibration of water at 2.9 μm. By laser ablation the droplets explode, ejecting preformed biomolecular ions into the vacuum. The total volume of solution required for the mass determination is only few microliters in typically micromolar concentration. The method is ideal for studying biomolecules of low availability (49). The amount of energy transferred into noncovalent complexes by the IR desorption/ablation process can be controlled in a wide range, starting from ultrasoft to harsh conditions, just by varying the laser intensity (50). At ultrasoft conditions large macromolecules can be detected in their native stoichiometry. The complexes are detected in different charged states, preferentially as anions. The number of charge states observed increases with the size of the molecules but is less than those observed in electro spray ionization and considerably more than in MALDI. To investigate the quaternary structure of the Lsm protein, we dialyzed the recombinant protein against a buffer (50 mm NaCl, 10 mm of Tris/HCl, pH 7.5). Complexes were analyzed using LILBID-MS. To analyze the binding of Lsm proteins to oligo(U)-RNA, 8 μm oligo(U)-RNA (U30) were incubated at room temperature for 30 min with 4 μm of heptameric Lsm complexes in a buffer containing 20 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, and 10 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.5. The resulting complexes were analyzed using LILBID-MS. To investigate the binding to sRNAs, 4 μm of Lsm heptamers were incubated with 8 μm of sRNA30 at room temperature for 30 min. Again the resulting complexes were analyzed using LILBID-MS.

Generation of the lsm Deletion Strain

The lsm reading frame was completely removed in the H. volcanii strain H119 using the pop-in/pop-out method (39, 51). The upstream and downstream regions of the lsm gene were amplified by PCR using chromosomal DNA from H. volcanii and primers SmKO/FLAG1, SmKO3, SmKO/FLAG2, and SmKO4, respectively, yielding fragments Sm1 and Sm2, both ∼1 kb long. PCR primers contained different restriction sites: ApaI (SmKO/FLAG1), EcoRV (SmKO3), EcoRV (SmKO/FLAG2), and XbaI (SmKO4). Both PCR fragments were first cloned into pBluescriptII (Stratagene), yielding plasmids pblue-Sm1 and pblue-Sm2 and subsequently subcloned into the integrative vector pTA131 containing the pyrE2 marker (39), yielding pTA131-Sm1/2. This plasmid was integrated into the chromosomal DNA of H. volcanii (strain H119, pop-in). The plasmid containing the pyrE2 marker was forced out by plating the cells on 5-fluoro-orotic acid (pop-out). Southern blot analysis was carried out as described in Ref. 52 with the following modifications. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from wild type and knock-out strains and digested using XhoI. 10 μg of digested DNA was separated on a 0.8% agarose gel and transferred to a nylon membrane (HybondTM-N; GE Healthcare). Hybridization probe Sm1 was generated by PCR using primers SmKO/FLAG1 and SmKO3 on template pblue-Sm1, yielding a 1-kb fragment, which was subsequently radioactively labeled using the random prime kit ReadiprimeTM II (GE Healthcare).

Co-immunoprecipitation

To isolate an S100 extract, the cells were grown to stationary phase in Hv-Ca+ broth including 0.25 mm tryptophane and harvested at OD650 = 2.8. The cells were pelleted, and the resulting pellets were washed with enriched PBS (2.5 m NaCl, 150 mm MgCl2, 1× PBS (137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 10 mm Na2PO4, 2 mm KHPO4, pH 7.4)). The cells were again pelleted, resuspended in enriched PBS containing 1% formaldehyde, and incubated for 20 min at 45 °C. To stop the cross-linking reaction, glycine was added to a final concentration of 0.25 m and incubated for 5 min at 45 °C. The cells were washed twice with enriched PBS at 4 °C, and then lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2) containing 150 μl of proteinase inhibitor (Sigma) was added. After ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g for 30 min) RNase A was added to a final concentration of 400 μg/ml extract, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, NaCl was added to a final concentration of 150 mm, and the lysate was frozen at −80 °C. For affinity purification, 1.6 ml of anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma) was washed 10 times with 10 ml of ice-cold washing buffer (50 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl) before the lysate was added. After incubation overnight (14–16 h) at 4 °C, anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel was washed eight times with 10 ml of ice-cold washing buffer. The elution of the FLAG fusion protein was performed by using 4 ml of washing buffer, to which 3× FLAG peptide was added (final concentration, 150 ng/μl). The samples were incubated at 4 °C with gentle shaking. In a final elution step the affinity gel was rinsed with 2 ml of washing buffer. For the isolation of co-precipitated RNA, the cross-link reaction was released by incubating the samples at 95 °C for 20 min. The fraction was treated with 20 μg of proteinase K for 30 min at 37 °C in 100 μl of buffer (100 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 12.5 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl, 0.2% SDS). The solution was extracted with phenol-chloroform-isoamylalcohol. The aqueous phase containing RNA was precipitated, and the resulting pellet was dissolved in water. An aliquot of the RNA fraction was 3′-labeled with [α-32P]pCp as described (53).

Mass Spectrometry

For mass spectrometric analysis proteins associated with the FLAG only, the FLAG-Lsm (without cross-link), and the FLAG-Lsm (with cross-link) proteins were dissolved in 1× loading buffer, and cross-linked samples were incubated for 20 min at 95 °C. The samples were then loaded onto a 4–12% NuPAGE-Gel (Invitrogen). After Coomassie staining, the gel lanes were cut into 23 slices, and the proteins were in-gel digested with trypsin according to Ref. 54. Extracted peptides were analyzed by LC-MS/MS on a Q-ToF instrument (Waters) under standard conditions. Peptide fragment spectra were searched against a target decoy database for H. volcanii (46) using MASCOT as a search engine. Peptides with a peptide score lower than 25 were omitted from the results. Scaffold software (Proteome Software, Inc., Portland, OR) was used for data evaluation (see supplemental tables). The proteins that were co-purified with the FLAG peptide in the control reaction were subtracted from the proteins co-purified with the FLAG-Lsm protein. In Table 1 only proteins, which were present in all three FLAG-Lsm purifications with at least four MS/MS spectra in each of the three independent isolations are listed. The complete list of identified proteins is shown in supplemental Table S3.

TABLE 1.

Proteins interacting with the Lsm protein

Co-immunoprecipitation with the FLAG-Lsm fusion protein revealed several proteins associated specifically with the Lsm protein (proteins co-purified with the control were subtracted). Proteins are grouped into functional classes. The number of obtained MS/MS spectra is shown. Only proteins that were present in all three FLAG-Lsm purifications with at least four MS/MS spectra in each of the three independent isolations are listed. The complete list of identified proteins is shown in supplemental Table 3. In addition, supplemental Table 3 lists the accession numbers and the number of MS/MS spectra for all three replicas.

| Protein | Number of MS/MS spectra | |

|---|---|---|

| Translation | ||

| 1 | Translation elongation factor aEF-2 | 47 |

| 2 | Translation elongation factor aEF-1 α subunit | 29 |

| 3 | Ribosomal protein S3 | 10 |

| 4 | Threonyl-tRNA synthetase | 9 |

| 5 | Ribosomal protein S3a.eR | 8 |

| 6 | Valyl-tRNA synthetase | 7 |

| Stress-related | ||

| 7 | Heat shock protein Cct2 | 32 |

| 8 | Heat shock protein Cct1 | 30 |

| 9 | CBS domain pair, putative | 16 |

| 10 | Thermosome subunit 3 | 10 |

| 11 | UspA domain protein | 7 |

| Nucleic acid metabolism | ||

| 12 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit A | 15 |

| 13 | mRNA 3-end processing factor homolog | 13 |

| 14 | Sugar-specific transcriptional regulator TrmB | 6 |

| 15 | Putative nuclease | 6 |

| 16 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit B | 5 |

| 17 | Replication factor C small subunit | 4 |

| Cell cycle | ||

| 18 | Cell division control protein 48 | 15 |

| 19 | Cell division control protein 48 | 12 |

| 20 | SMC-like protein Sph2 | 10 |

| Diverse functions | ||

| 21 | Betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase | 16 |

| 22 | Chlorite dismutase family protein | 12 |

| 23 | Pyruvate-ferredoxin oxidoreductase α subunit | 10 |

| 24 | Predicted hydrolase | 10 |

| 25 | Aconitate hydratase, putative | 10 |

| 26 | Coiled-coil protein | 9 |

| 27 | Fumarate hydratase class II | 9 |

| 28 | Proteasome subunit α1 | 8 |

| 29 | Putative orotatephosphoribosyl transferase | 8 |

| 30 | Phosphopyruvate hydratase | 7 |

| 31 | Aspartate carbamoyltransferase | 7 |

| 32 | Short chain family oxidoreductase | 7 |

| 33 | Inosine-5-monophosphate dehydrogenase | 6 |

DNA Microarray Analysis

The affinity-purified FLAG-tagged Lsm complexes and a negative control (FLAG peptide not tagged to Lsm) were used for RNA isolation as described (see “Co-immunoprecipitation” above). 1-μg aliquots of the two fractions were used for cDNA synthesis, labeling, and DNA microarray analysis as described, using a self-constructed DNA microarray for H. volcanii (55). sRNA-specific oligonucleotide probes were added to the DNA microarray to allow the analysis of sRNA gene expression.3 Three independent experiments were performed, including a dye swap. The analysis of DNA microarray results was performed as described (55).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Little is known about the archaeal Lsm proteins and therefore we were interested in unraveling the function of the archaeal Lsm protein using in vitro and in vivo approaches.

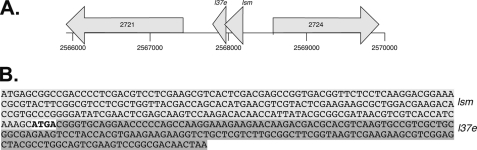

The Lsm Reading Frame Overlaps with the Reading Frame for a Ribosomal Protein

Using a BLAST search (56) with previously described archaeal Lsm proteins (23), we identified the Lsm protein gene in the genome of H. volcanii (46). H. volcanii contains a single lsm gene (HVO_2723), which encodes a protein of 76 amino acids with a molecular mass of 8.25 kDa and an pI of 3.9. The Haloferax Lsm protein was found to belong to the Lsm1 subfamily of Lsm proteins. The lsm gene overlaps by four nucleotides with a gene annotated to encode the L37e ribosomal protein (HVO_2722; Fig. 1). To analyze the conservation of gene order and Lsm protein sequence in the domain archaea, a BLAST search was used to identify similar proteins and their genes. The gene order is highly conserved in archaea. In more than 40 archaeal genomes, the gene for the L37e proteins follows the lsm gene. In more than 30 genomes, the two genes are very closely spaced or overlap, so that co-transcription can be assumed. The multiple sequence alignment of the H. volcanii Lsm1 and 31 other archaeal Lsm1 proteins (supplemental Fig. S1A) shows that the protein is highly conserved in archaea with the exception of the regions corresponding to β-sheets 2 and 3 in the structure of the P. abyssi Lsm (18), which is variable in the whole family and especially in the six haloarchaeal Lsm proteins. It should be noted that the three residues that form a highly specific binding pocket for uridine in the P. abyssi Lsm are universally conserved, indicating specific uridine binding in all of the archaeal Lsm1 proteins.

FIGURE 1.

Genomic location of the Lsm protein gene. A, the operon containing the genes for Lsm and L37e is bordered by the gene for a potential hydrolase (HVO_2724) and the gene for an amidophosphoribosyltransferase (HVO_2721). The genomic region is given below in nucleotides. B, the reading frames for the Lsm protein (shown in light gray) and the ribosomal protein L37e (shown in dark gray) overlap by 4 nt (shown in bold type).

Expression of the lsm Gene and Determination of Lsm Copy Number

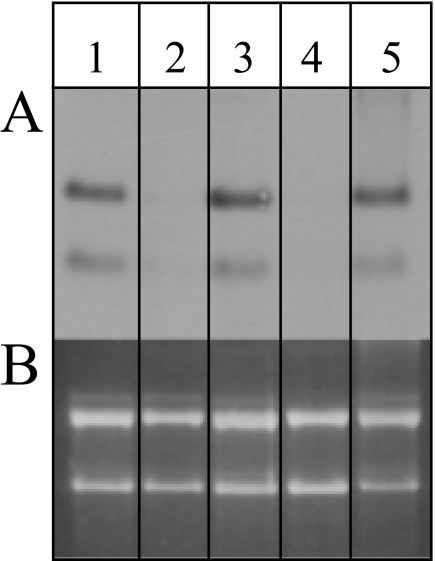

Northern blot analyses were used as a first approach to analyze the expression of the lsm gene. Using a probe against the two overlapping genes, two transcripts of ∼430 and ∼210 nt, respectively, could be detected (Fig. 2). Gene-specific probes revealed that the smaller transcript was derived from the gene for the L37e protein, which can either be a primary transcript initiated from a promoter localized within the open reading frame of the upstream located lsm gene or originate from the processing of the bicistronic transcript. According to the genome sequence, a bicistronic transcript should be 404 nt, and a transcript encoding only L37e should be 177 nt. Using circularized RNA RT-PCR (45, 57), we determined that the bicistronic transcript is leaderless and contains a 3′-UTR of 41 nt, in excellent agreement with the Northern blot results (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Differential expression of the lsm gene. A, the transcript levels of the lsm gene in cells grown under different conditions were determined by Northern blot analysis. B, the corresponding agarose gel shows that all of the lanes were loaded with the same amount of RNA. The following conditions were applied: aerobic growth in 2.1 m NaCl at 42 °C (lane 1), at 30 °C (lane 2), and at 48 °C (lane 3); anaerobic, nitrate-respirative growth (lane 4); and 1.5 m NaCl (lane 5).

To observe a potential differential regulation of transcription, Northern blot analyses were performed using RNA from cells cultivated under different conditions. During aerobic growth, the transcript levels did not change throughout the growth curve, from early exponential to stationary phase (data not shown). It was also identical during growth at low salt (1.5 m NaCl; Fig. 2), high salt (3 m NaCl, data not shown), and high temperature (48 °C; Fig. 2). By contrast, both the bicistronic and the monocistronic transcript were undetectable in the cultures grown at a low temperature (30 °C; Fig. 2) or via nitrate-respirative growth (Fig. 2). Taken together, both transcripts were apparently co-regulated and are present in H. volcanii under most but not all conditions.

For the analysis of the Lsm protein, we expressed the lsm gene in E. coli to produce a recombinant protein. The gene was efficiently expressed to yield a pure fraction of recombinant Lsm protein (supplemental Fig. S3), against which an antiserum was generated. Western blot analysis was used for the relative quantification of the protein levels in cytoplasmic extracts from cells grown at different salt concentrations (1.2, 2.5, and 3 m) either to the exponential or stationary phase. In each case, the Lsm protein levels were identical; thus, we found no indication for translational regulation (data not shown). For the absolute quantification of the intracellular protein level, a standard curve was generated using heterologously produced and purified Lsm protein (see below), revealing that H. volcanii contains ∼4,000 Lsm molecules/cell (supplemental Fig. S2). By contrast, 50,000–60,000 copies of Hfq are present in rapidly growing E. coli cells in the exponential phase, but the level is rapidly down-regulated to ∼20,000 copies/cell at the onset of the stationary phase (3, 58). We found no reports about intracellular copy numbers of additional Lsm proteins, neither in prokaryotes nor in eukaryotes.

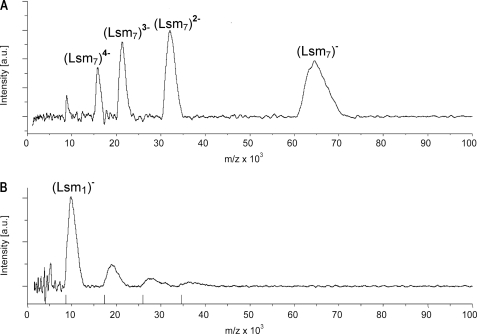

The Recombinant Lsm Protein Forms Homoheptamers

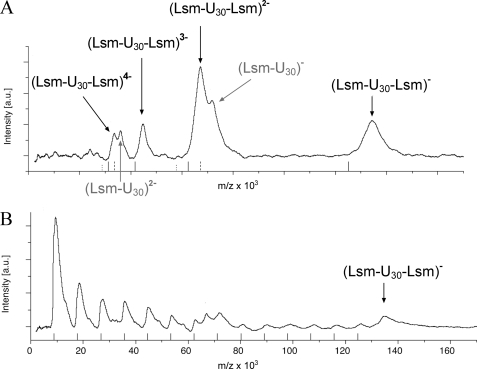

To investigate whether the Haloferax Lsm protein forms homomeric complexes, we employed ultrasoft mass spectrometry (LILBID-MS) (see “Experimental Procedures” for details) (49). This approach revealed that the protein forms homoheptamers in vitro (Fig. 3A and data not shown). Under harsh conditions (high laser intensity), the complex could be fragmented and masses corresponding to Lsm monomers, dimers, trimers, and tetramers were observed (Fig. 3B). Other archaeal Lsm1-type proteins also form homoheptamers (28, 31–33), in contrast to proteins of the Hfq and Lsm2 subfamilies, which form exclusively homohexamers (Hfq) or have the potential to form homohexamers (Lsm2) (6, 36). The eukaryotic Lsm proteins have been shown to form heteroheptamers (28, 31–33). Therefore, as for other archaeal proteins involved in transcription, replication, or translation, the archaeal Lsm proteins can be regarded as a closer mimic and simpler model for the eukaryotic proteins, which have added further complexity during evolution. Thus, the archaeal Lsm proteins are much better models for the eukaryotic proteins than the bacterial Hfq protein (5).

FIGURE 3.

The Lsm protein forms homoheptameric complexes. A, in soft mode native mass spectrometry clearly shows that the Haloferax Lsm protein forms heptameric complexes. Depicted are the charge states of the heptamer. B, under harsh conditions the heptamer completely dissociates into fragments mostly into the monomer. Markers on the x axis indicate the masses of Lsm monomers, dimers, trimers, and tetramers (for z = 1).

Characterization of Lsm-RNA Interactions in Vitro

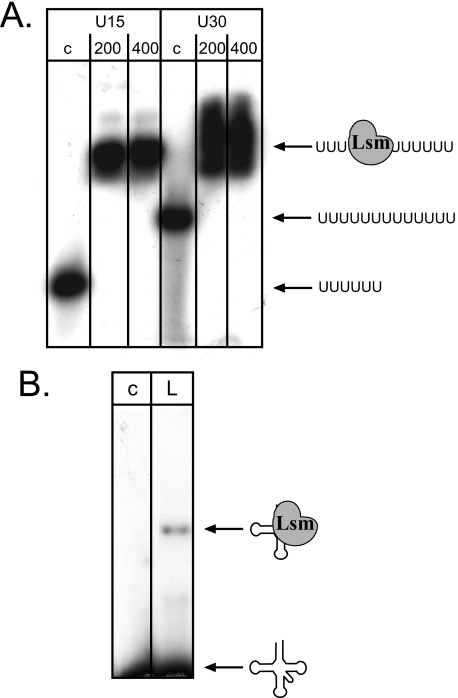

To analyze whether the recombinant Lsm protein binds RNA, we incubated it with oligo(U)-RNA (U15- and U30-RNA) and investigated the interaction using EMSA. The gel shift analysis showed that the recombinant Lsm indeed binds U30-RNA. Using U30-RNA and increasing Lsm protein concentrations, we determined the dissociation constant KD to be 72 nm (Fig. 4A and supplemental Fig. S4). Binding to oligo(U)-RNA has been shown for eukaryotic Lsm proteins (31, 59), for other archaeal ones (31), and also for Hfq (6). The physiological significance of the archaeal Lsm binding to oligo(U)-RNA is unclear because oligo(U) stretches have not been identified in the RNA population from Haloferax so far.

FIGURE 4.

Haloferax Lsm binds to RNA. A, the recombinant Lsm protein was incubated with oligo(U)-RNA and subsequently loaded onto nondenaturing PAGE. Lanes c, control reaction without proteins; lanes 200 and 400, incubation with 200 and 400 ng of recombinant Lsm protein, respectively. U15 and U30, incubation with U15-RNA and U30-RNA, respectively. RNA and complex are shown schematically at the right. B, tRNA is also bound by the Lsm protein. Incubation of Lsm with a wheat tRNA fraction shows that Lsm also binds to tRNAs. Lane c, control reaction without protein. Lane L, incubation with 100 ng of Lsm protein. RNA and complex are shown schematically on the right.

Because the E. coli Hfq and the yeast Lsm protein were suggested to be involved in tRNA processing and modification (60–62), we incubated the archaeal Lsm protein with tRNAs. EMSA revealed that the Haloferax Lsm protein also binds to tRNAs (Fig. 4B).

Native Mass Spectrometry Confirms Lsm-RNA Interactions

An additional approach to study RNA binding by Lsm and to unravel the stoichiometry of complex formation LILBID-MS was used. Purified Lsm protein was incubated with U30-RNA, and mass spectrometry analysis under ultrasoft conditions (low laser intensity) confirmed that one Lsm heptamer bound to U30-RNA and revealed in addition that another complex forms consisting of two Lsm heptamers bound to U30-RNA (Fig. 5A). Analysis under harsh conditions (high laser intensity) revealed that the ternary complex was very stable, and Lsm subunits were lost, whereas the complex remains otherwise intact (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Two Lsm complexes bind to oligo(U)-RNA. A, in soft mode native mass spectrometry shows mostly a ternary complex consisting of two Lsm heptamers bound to one U30-RNA molecule. The charge states of the ternary complex are indicated. In addition, a binary complex could also be detected with a lower signal intensity (shown in gray). B, under harsh conditions the complexes partially dissociate into smaller fragments. As can be clearly seen, the ternary complex does not dissociate stoichiometrically but rather loses a varying number of monomers.

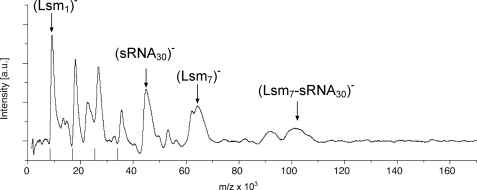

LILBID-MS was also used to clarify whether sRNAs bind to Lsm. Incubation of Lsm with sRNA30 and subsequent analysis with LILBID-MS revealed that an Lsm-sRNA30 complex forms but, in contrast to U30-RNA ternary complexes (Lsm-sRNA30-Lsm), were not detected (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

The Lsm complex binds to sRNA30. LILBID-MS shows a significant amount of unbound heptamer as well as unbound sRNA30. In addition, a binary complex could be detected preceded by a complex of unexpected size. A second complex of unexpected size was also found, which cannot be explained. However, analysis of the RNA alone also revealed a peak of the expected mass of 42 kDa and a second, unexpected peak. Although further experiments are needed to explain the unexpected peaks, the results clearly show the absence of the ternary complex (two Lsm heptamers: one RNA) with sRNA30, which was the major complex with U30-RNA. In addition, the results confirmed the higher affinity of the Lsm protein to U30-RNA compared with sRNA30, because in the former case the total protein amount was bound in a complex with RNA, whereas in the latter case a considerable fraction of the protein remained unbound.

Deletion of the Lsm Frame Is Viable

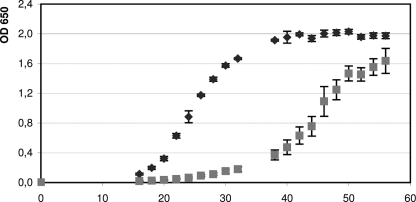

To pinpoint the biological function of the archaeal Lsm protein, we generated an lsm deletion mutant using the pop-in/pop-out method (39, 51, 63). Because the overlap of the lsm and l37e genes indicated translational coupling, care was taken to generate an in-frame deletion mutant that left translational coupling intact and avoided putative polar effects. After pop-out selection, small and large colonies were observed. Southern blot analysis revealed that only the small colonies contained the lsm deletion (termed Δlsm), and the large colonies still contained the wild type lsm gene (supplemental Fig. S5). Comparison of the Δlsm deletion mutant and the wild type under standard growth conditions (see “Experimental Procedures”) revealed that the mutant exhibited an extensive lag phase before the onset of growth and had a reduced growth rate (Fig. 7). Comparison of the growth capabilities of mutant and wild type under various conditions revealed that the phenotypic difference between the two strains was variable, e.g. the mutant grew nearly as well as the wild type on casamino acids, pyruvate, xylose, and arabinose (lower growth yield on arabinose) but was severely compromised on glycerine and sucrose (data not shown). Therefore, it seems that the importance of the Lsm protein for cellular physiology is different for various metabolic pathways. To gain further insight into the function of Lsm, we decided to identify its interaction partners.

FIGURE 7.

Comparison of wild type and lsm deletion strain. Comparison of the growth curves of wild type (dark gray diamonds) and deletion strain (light gray squares) shows that the lsm deletion results in slower growth. The x axis indicates the time of growth in hours.

Co-immunoprecipitation Reveals Several Interaction Partners

To identify the interaction partners of the Lsm protein, we constructed a FLAG-Lsm fusion protein. For that purpose we first generated the expression vector pTA927, which is based on pTA230 (39) and features the tryptophan-inducible tnaA promoter for regulatable gene expression in Haloferax (41). Subsequently, the FLAG peptide cDNA was cloned in-frame downstream and upstream, respectively, of the Lsm reading frame into the pTA927 vector. In addition, a plasmid was constructed encoding only the FLAG peptide as a negative control. Haloferax was transformed with the plasmids, and expression was analyzed using Western blots (supplemental Fig. S6A), showing that both fusion proteins were efficiently expressed in Haloferax. The lsm deletion strain Δlsm was likewise transformed with the plasmids, resulting in Haloferax strains expressing only the plasmid-encoded FLAG-Lsm fusion proteins. H. volcanii has an intracellular salt concentration of 2.5–4 m KCl, and it is currently not known whether any protein and ribonucleoprotein complexes require high salt concentrations for stability in vitro. Therefore, interacting RNA and protein molecules were cross-linked to the Lsm protein by incubating the Haloferax cells with formaldehyde before cell lysis to prevent disintegration of complexes during dialysis against low salt buffer. Cross-linking offers the additional advantage that transient interactions and low affinity partners are captured. As control, additional preparations were performed without the addition of formaldehyde to compare formaldehyde-treated and untreated samples. After the formaldehyde treatment, the cells were lysed, and an S100 protein extract was isolated. To remove proteins attached to the Lsm protein via RNA molecules, the S100 was digested with RNase A. Subsequently, the fusion protein and its interaction partners were isolated from the S100 extract using anti-FLAG affinity agarose.

To identify which proteins bind to the FLAG peptide, a control was prepared in parallel with only the FLAG peptide (without the Lsm protein). All of the precipitations were done in triplicate.

Identification of Protein Interaction Partners

For the analysis of protein interaction partners, the cross-link was reversed, and the proteins were separated with 3–12% SDS-PAGE (supplemental Fig. S6B). The proteins were subsequently analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The control preparation containing only the FLAG peptide revealed very few protein molecules, and in the three independent preparations only six proteins were present in all three samples (supplemental Table S1), showing that few proteins bind to the FLAG tag. The precipitation of proteins from the FLAG-Lsm sample, which was not treated with formaldehyde before cell lysis, also revealed only very few proteins. In this case, only a single protein was identified that was present in all three independent samples, indicating that without cross-linking no specific interaction partner can be isolated (supplemental Table S2) and thus that the cross-linking step is required to identify interaction partners. The comparison of FLAG-Lsm co-immunoprecipitation with and without cross-link clearly showed that the purification procedure interrupts existing complexes and that cross-linking is required to keep the complexes intact upon lowering the salt concentration from the intracellular 2.1 m KCl to 150 mm NaCl.

To identify proteins specific for Lsm co-immunoprecipitation, the proteins identified by mass spectrometry in the control (FLAG only) (supplemental Table S1) were subtracted from those identified in the FLAG-Lsm co-immunoprecipitation, resulting in proteins specific for the Lsm co-immunoprecipitation (Table 1). Therefore, the proteins listed in Table 1 are true interaction partners, because proteins from the control co-purification (FLAG only) were subtracted, and in addition an RNase digest was performed. Altogether 33 proteins were identified; a similar high number of interaction partners has been found for the bacterial Hfq (57 proteins (64)) and the eukaryotic Sm and Lsm proteins (5). Furthermore, the proteins identified here as interaction partners belong to similar functional classes as the partners identified for the bacterial Hfq and eukaryotic Lsm proteins (5): e.g. ribosomal proteins, elongation factors, tRNA synthetases, chaperones, and ribonucleases. Details such as the regions of the Lsm protein involved in the interactions remain to be analyzed, but the apparent functional conservation of the protein is striking, and the number of interaction partners confirms the versatility of these proteins.

The Archaeal Lsm Protein Interacts with sRNAs and snoRNAs

To identify the RNA interaction partners, the cross-link was reversed, and the RNA was isolated from this fraction. An aliquot was labeled with [α-32P]pCp, revealing several RNA molecules binding to Lsm (supplemental Fig. S6C). To further identify the RNA molecules, we employed DNA microarray analysis. Labeled cDNA was generated from the RNA, which co-purified with the FLAG-Lsm protein and with the FLAG only peptide, respectively. Competitive hybridization with a self-constructed DNA microarray led to the identification of 20 sRNAs that co-purified with the Lsm protein (Table 2). Several of these RNAs have recently been identified as candidate sRNAs (Ref. 38 and Table 1 therein): intergenic sRNAs 30, 34, 132, 304, and 308; antisense sRNAs 25 and 144; and sense sRNAs 15 and 93. Seven of the Lsm-binding RNAs (H225.1, p12, p5, H225.2r, H230, H11.1, and H62r) had been predicted as sRNAs using bioinformatic approaches.4 The DNA microarray results show for the first time that these predicted sRNAs are indeed expressed. A snoRNA (sRNA45) that had been predicted as C/D box snoRNA4 was also identified. Interestingly, the 7 S RNA also co-purified with the Lsm protein. The binding of Lsm to sRNAs suggests a similar function of the archaeal protein in the regulatory network of sRNAs as for the bacterial Hfq protein. Unfortunately, so far no targets have been identified for an archaeal sRNA; thus, the influence of Lsm on sRNA/target RNA interaction remains to be determined.

TABLE 2.

RNAs interacting with the Lsm protein

RNA isolated from the co-immunoprecipitation with the FLAG-Lsm fusion protein was used to hybridize DNA microarrays. Several RNAs associated with the Lsm protein could be identified. The red/green ratio denotes the average signal strengths of cDNAs generated from RNA co-purified with the FLAG-Lsm protein divided by the average signal strengths of a negative control cDNA generated from RNA purified from cultures only expressing the FLAG peptide. RNAs termed “sRNA” were previously identified as sRNAs in Haloferax (37,38). RNAs termed “H” and “p” had been predicted as sRNAs using bioinformatic approaches.4

| RNA | Ratio of red/green |

|---|---|

| H225.1 | 194,02 |

| sRNA25 | 29,71 |

| sRNA30 | 22,76 |

| sRNA144 | 17,76 |

| sRNA34 | 16,44 |

| p12 | 15,15 |

| sRNA15 | 14,15 |

| sRNA93 | 12,77 |

| sRNA308 | 9,83 |

| sRNA132 | 9,62 |

| p5 | 9,10 |

| sRNA45 | 8,91 |

| H225.2r | 7,30 |

| H230 | 6,95 |

| H11.1 | 5,45 |

| H62r | 2,30 |

| sRNA140 | 2,16 |

The binding of the Lsm protein to a potential C/D box snoRNA is interesting because the attachment of an Lsm protein to a snoRNA has not yet been found in archaea. The archaeal C/D box snoRNAs and their function have been studied in detail in Sulfolobus solfataricus (65). Three proteins have been identified that associate with the snoRNA to form the methylation guide complex: L7Ae, aFib, and aNop56/58. Homologues for all three proteins are also present in H. volcanii. Interestingly, the aNop56/58 homologue is also found as a protein interaction partner in the co-immunoprecipitation but not L7Ae and aFib (Table 1). Because the eukaryotic counterparts of the archaeal Lsm protein bind to snoRNAs, it is likely that the archaeal Lsm protein binds to archaeal snoRNAs. The specific role of that interaction remains to be determined.

The lsm Deletion Mutant Exhibits a Pleiotropic Phenotype

Although the Lsm protein is involved in many processes, it is not essential. The mutant has severe growth defects compared with the wild type under a variety of conditions, supporting the suggestion that Lsm is involved in many different pathways. Similar observations have been made in bacteria, where Hfq is involved in several processes. Deletions of the E. coli hfq gene resulted in pleiotropic physiological effects, and the lack of phenotype under specific conditions was also observed (11, 13, 66, 67). The construction of hfq deletion mutants in other bacterial species revealed a fundamental role of Hfq in the virulence of pathogenic bacteria (67–73). No apparent phenotype emerged from an hfq knock-out in Staphylococcus aureus (74). In summary, deletion mutants of prokaryotic lsm genes revealed that Lsm proteins are involved in many processes, and their absence results in pleiotropic phenotypes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Elli Bruckbauer for expert technical assistance and Katharina Jantzer for growth experiments with the lsm mutant. Furthermore, we thank members of the SPP 1258 Priority Program for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through SPP 1258 Priority Program “Sensory and Regulatory RNAs in Prokaryotes” Grants DFG Ma1538/11-1 and So264/14-1.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1–S3 and Figs. S1–S6.

J. Straub, C. Lange, and J. Soppa, unpublished data.

J. Straub, B. Stoll, B. Tjaden, B. Voss, W. R. Hess, A. Marchfelder, and J. Soppa, in preparation.

- snRNA

- small nuclear RNA

- snoRNA

- small nucleolar RNA

- LILBID

- laser-induced liquid bead ion desorption

- sRNA

- small RNA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Møller T., Franch T., Højrup P., Keene D. R., Bächinger H. P., Brennan R. G., Valentin-Hansen P. (2002) Mol. Cell 9, 23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang A., Wassarman K. M., Ortega J., Steven A. C., Storz G. (2002) Mol. Cell 9, 11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valentin-Hansen P., Eriksen M., Udesen C. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 51, 1525–1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun X., Zhulin I., Wartell R. M. (2002) Nucleic. Acids Res. 30, 3662–3671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilusz C. J., Wilusz J. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 1031–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schumacher M. A., Pearson R. F., Møller T., Valentin-Hansen P., Brennan R. G. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 3546–3556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senear A. W., Steitz J. A. (1976) J. Biol. Chem. 251, 1902–1912 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Haseth P. L., Uhlenbeck O. C. (1980) Biochemistry. 19, 6146–6151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen J. S., Bøggild A., Andersen C. B., Nielsen G., Boysen A., Brodersen D. E., Valentin-Hansen P. (2007) RNA 13, 2213–2223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wassarman K. M., Repoila F., Rosenow C., Storz G., Gottesman S. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 1637–1651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsui H. C., Leung H. C., Winkler M. E. (1994) Mol. Microbiol. 13, 35–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown L., Elliott T. (1996) J. Bacteriol. 178, 3763–3770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muffler A., Fischer D., Hengge-Aronis R. (1996) Genes Dev. 10, 1143–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massé E., Gottesman S. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 4620–4625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Møller T., Franch T., Udesen C., Gerdes K., Valentin-Hansen P. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 1696–1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sledjeski D. D., Whitman C., Zhang A. (2001) J. Bacteriol. 183, 1997–2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang A., Altuvia S., Tiwari A., Argaman L., Hengge-Aronis R., Storz G. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 6061–6068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thore S., Mayer C., Sauter C., Weeks S., Suck D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1239–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tharun S., He W., Mayes A. E., Lennertz P., Beggs J. D., Parker R. (2000) Nature 404, 515–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouveret E., Rigaut G., Shevchenko A., Wilm M., Séraphin B. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 1661–1671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pannone B. K., Xue D., Wolin S. L. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 7442–7453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayes A. E., Verdone L., Legrain P., Beggs J. D. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 4321–4331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salgado-Garrido J., Bragado-Nilsson E., Kandels-Lewis S., Séraphin B. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 3451–3462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klenk H. P., Clayton R. A., Tomb J. F., White O., Nelson K. E., Ketchum K. A., Dodson R. J., Gwinn M., Hickey E. K., Peterson J. D., Richardson D. L., Kerlavage A. R., Graham D. E., Kyrpides N. C., Fleischmann R. D., Quackenbush J., Lee N. H., Sutton G. G., Gill S., Kirkness E. F., Dougherty B. A., McKenney K., Adams M. D., Loftus B., Peterson S., Reich C. I., McNeil L. K., Badger J. H., Glodek A., Zhou L., Overbeek R., Gocayne J. D., Weidman J. F., McDonald L., Utterback T., Cotton M. D., Spriggs T., Artiach P., Kaine B. P., Sykes S. M., Sadow P. W., D'Andrea K. P., Bowman C., Fujii C., Garland S. A., Mason T. M., Olsen G. J., Fraser C. M., Smith H. O., Woese C. R., Venter J. C. (1997) Nature 390, 364–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith D. R., Doucette-Stamm L. A., Deloughery C., Lee H., Dubois J., Aldredge T., Bashirzadeh R., Blakely D., Cook R., Gilbert K., Harrison D., Hoang L., Keagle P., Lumm W., Pothier B., Qiu D., Spadafora R., Vicaire R., Wang Y., Wierzbowski J., Gibson R., Jiwani N., Caruso A., Bush D., Safer H., Patwell D., Prabhakar S., McDougall S., Shimer G., Goyal A., Piertrokovski S., Church G. M., Daniels C. J., Mao J. I., Rice P., Nölling J., Reeve J. N. (1997) J. Bacteriol 179, 7135–7155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pühler G., Leffers H., Gropp F., Palm P., Klenk H. P., Lottspeich F., Garrett R. A., Zillig W. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 4569–4573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omer A. D., Lowe T. M., Russell A. G., Ebhardt H., Eddy S. R., Dennis P. P. (2000) Science. 288, 517–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Törö I., Thore S., Mayer C., Basquin J., Séraphin B., Suck D. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 2293–2303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khusial P., Plaag R., Zieve G. W. (2005) Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 522–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mura C., Phillips M., Kozhukhovsky A., Eisenberg D. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 4539–4544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Achsel T., Stark H., Lührmann R. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 3685–3689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collins B. M., Harrop S. J., Kornfeld G. D., Dawes I. W., Curmi P. M., Mabbutt B. C. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 309, 915–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mura C., Cascio D., Sawaya M. R., Eisenberg D. S. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 5532–5537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Törö I., Basquin J., Teo-Dreher H., Suck D. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 320, 129–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mura C., Kozhukhovsky A., Gingery M., Phillips M., Eisenberg D. (2003) Protein Sci. 12, 832–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sauter C., Basquin J., Suck D. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 4091–4098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soppa J., Straub J., Brenneis M., Jellen-Ritter A., Heyer R., Fischer S., Granzow M., Voss B., Hess W. R., Tjaden B., Marchfelder A. (2009) Biochem. Soc Trans. 37, 133–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Straub J., Brenneis M., Jellen-Ritter A., Heyer R., Soppa J., Marchfelder A. (2009) RNA Biol 6, 281–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allers T., Ngo H. P., Mevarech M., Lloyd R. G. (2004) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 943–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimmin L. C., Dennis P. P. (1996) J. Bacteriol. 178, 4737–4741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Large A., Stamme C., Lange C., Duan Z., Allers T., Soppa J., Lund P. A. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 66, 1092–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chomczynski P., Sacchi N. (1987) Anal. Biochem. 162, 156–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herrmann U., Soppa J. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 46, 395–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baumann A., Lange C., Soppa J. (2007) BMC Cell Biol. 8, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yokobori S., Pääbo S. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 10432–10435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pfeiffer F., Broicher A., Gillich T., Klee K., Mejía J., Rampp M., Oesterhelt D. (2008) Arch. Microbiol. 190, 281–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hölzle A., Fischer S., Heyer R., Schütz S., Zacharias M., Walther P., Allers T., Marchfelder A. (2008) RNA 14, 928–937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Späth B., Kirchner S., Vogel A., Schubert S., Meinlschmidt P., Aymanns S., Nezzar J., Marchfelder A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 35440–35447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morgner N., Barth H., Brutschy B. (2006) Aust. J. Chem. 59, 109–114 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morgner N., Kleinschroth T., Barth H. D., Ludwig B., Brutschy B. (2007) J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 18, 1429–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bitan-Banin G., Ortenberg R., Mevarech M. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185, 772–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sambrook J., Russell D. (2001) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, pp. 6.47–6.58, Cold Spring Harbor Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kunzmann A., Brennicke A., Marchfelder A. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 108–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shevchenko A., Wilm M., Vorm O., Mann M. (1996) Anal Chem. 68, 850–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zaigler A., Schuster S. C., Soppa J. (2003) Mol. Microbiol 48, 1089–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schäffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D. J. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brenneis M., Hering O., Lange C., Soppa J. (2007) PLoS Genet 3, e229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Azam T. A., Ishihama A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 33105–33113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Achsel T., Brahms H., Kastner B., Bachi A., Wilm M., Lührmann R. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 5789–5802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kufel J., Allmang C., Verdone L., Beggs J. D., Tollervey D. (2002) Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 5248–5256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee T., Feig A. L. (2008) RNA 14, 514–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang A., Wassarman K. M., Rosenow C., Tjaden B. C., Storz G., Gottesman S. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 50, 1111–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Allers T., Mevarech M. (2005) Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 58–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Butland G., Peregrín-Alvarez J. M., Li J., Yang W., Yang X., Canadien V., Starostine A., Richards D., Beattie B., Krogan N., Davey M., Parkinson J., Greenblatt J., Emili A. (2005) Nature 433, 531–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Omer A. D., Ziesche S., Ebhardt H., Dennis P. P. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 5289–5294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Muffler A., Traulsen D. D., Fischer D., Lange R., Hengge-Aronis R. (1997) J. Bacteriol. 179, 297–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sittka A., Pfeiffer V., Tedin K., Vogel J. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 63, 193–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Christiansen J. K., Larsen M. H., Ingmer H., Søgaard-Andersen L., Kallipolitis B. H. (2004) J. Bacteriol. 186, 3355–3362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ding Y., Davis B. M., Waldor M. K. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 53, 345–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lucchetti-Miganeh C., Burrowes E., Baysse C., Ermel G. (2008) Microbiology 154, 16–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Robertson G. T., Roop R. M., Jr. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 34, 690–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sharma A. K., Payne S. M. (2006) Mol. Microbiol. 62, 469–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sonnleitner E., Hagens S., Rosenau F., Wilhelm S., Habel A., Jäger K. E., Bläsi U. (2003) Microb. Pathog. 35, 217–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bohn C., Rigoulay C., Bouloc P. (2007) BMC Microbiol. 7, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dyall-Smith M. L. (2001) The Halohandbook: Protocols for Haloarchael Genetics, http://www.haloarchaea.com/resources/halohandbook/Halohandbook_2008_v7.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.