Abstract

The lifetime of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) in neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) is increased from <1 day to >1 week during early postnatal development. However, the exact timing of AChR stabilization is not known, and its correlation to the concurrent embryonic to adult AChR channel conversion, NMJ remodeling, and neuromuscular diseases is unclear. Using a novel time lapse in vivo imaging technology we show that replacement of the entire receptor population of an individual NMJ occurs end plate-specifically within hours. This makes it possible to follow directly in live animals changing stabilities of end plate receptors. In three different, genetically modified mouse models we demonstrate that the metabolic half-life values of synaptic AChRs increase from a few hours to several days after postnatal day 6. Developmental stabilization is independent of receptor subtype and apparently regulated by an intrinsic muscle-specific maturation program. Myosin Va, an F-actin-dependent motor protein, is also accumulated synaptically during postnatal development and thus could mediate the stabilization of end plate AChR.

Keywords: Development, Fluorescence, Fusion Protein, Mouse, Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors, Myosin Va, Neuromuscular Junction, Receptor Stability, Synaptogenesis, Time Lapse Imaging

Introduction

In developing and adult muscle, acetylcholine receptors (AChRs)2 at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) undergo dramatic changes in their metabolic stability. In newly formed synapses, AChRs become clustered and stabilized at a relatively rapid turnover rate of t½ ≈ 1 day (1). The initial clustering requires the muscle-specific kinase MuSK (2), associated signaling components (3), as well as the receptor-aggregating protein, rapsyn (4). Rapsyn, which interacts directly with AChR (5), contributes to receptor stability (6).

In the adult synapses the AChRs turnover is rather slow (t½ ≈ 10 days) (1, 7–10). Recent investigation of AChR has revealed that stabilization is not a static integration process, but results from AChR recycling that is regulated by muscle activity (11). There are indications that the actin cytoskeleton is involved in regulating synaptic targeting and stabilization of AChRs. Lately, class V myosin motor proteins have been identified to play important roles in synaptic plasticity. Although myosin Va (12) or myosin Vb (13) seems to be crucial for recycling of AMPA receptors of central synapses, proper turnover of AChR in adult neuromuscular synapses is dependent on myosin Va (14). The mechanism that localizes and stabilizes the AChRs within a postsynaptic scaffold and the operational and organizational sequence of postnatal stabilization processes including the developmentally occurring AChR channel conversion, however, remains unknown.

The temporal resolution of AChR stabilization as well as the direct observation of the rapid dynamics of channel conversion during early postnatal development has not been accomplished and appeared inaccessible. In the current study we implemented in vivo time lapse imaging techniques for direct, continuous visualization of surface AChR trafficking in vivo. This way we narrowed down the analysis time frame to the period between postnatal days 3 and 8 in mice, when major remodeling and maturation processes of the NMJs are initiated. We track AChR channel conversion at real time resolution, and we observe directly AChR stabilization events at single NMJs. The determination of the metabolic stability of end plate receptors is crucial for the understanding of the regulation of AChR turnover and activity-dependent plasticity of NMJs. Furthermore, in neuromuscular diseases, including myasthenic or dystrophic disorders, pathological changes could affect AChR stability. The direct visualization of receptor stability will be an important tool to investigate motor function deficits or genetic disorders.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals and Genotyping

The mouse line AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP was generated by homologous recombination fusing GFP into the γ subunit gene as described previously (15, 31). GFP-labeled γ subunits, γ-GFP subunits, are assembled into AChRγ-GFP complexes that substitute the wild type γ subunit-containing AChRγ. Dilute and wild type mice of the DLS/LeJ and the C57BL/6J strains, respectively, were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and then maintained in the local animal facility. All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institute of Health (Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996) and the European Community guidelines for the use of experimental animals.

Surgical Procedures

Newborn AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP, AChRϵ−/−, dilute and wild type animals between 3 and 30 days of age were anesthetized with a 20% w/v urethane (Sigma-Aldrich) solution in Ringer solution (2.0 g/kg, intraperitoneally). A skin area of about 5 × 5 mm was surgically removed above the left cnemis exposing the musculus tibialis anterior. Layers of connective tissue were gently removed from the muscle surface to allow better accessibility of the end plates and to reduce refraction artifacts when imaging.

Histological Preparation

AChRs were visualized with rhodamine-labeled α-bungarotoxin (r-bgt), at 2 μg/ml in Ringer's solution) (Molecular Probes). The solution was pipetted on the exposed muscle surface, incubated for 5 min, and washed off with Ringer's solution to avoid complete saturation and therefore possible inactivation of receptors. In toxin saturation experiments the muscle was incubated for 1 h with a concentrated toxin solution (r-bgt, at 5 μg/ml in Ringer's solution).

The anesthetized animal was then kept warm on a heated surface for the entire duration of the experiment, and the leg was attached to a metal bar of an adjustable, custom-made steel contraption to minimize body movement due to cardiac and respiratory activity. The exposed stained muscle surface was pressed against a coverslip (12-mm  ; Assistant, Germany), which was fixed underneath an immersion chamber and overcast with water for microscopy procedures.

; Assistant, Germany), which was fixed underneath an immersion chamber and overcast with water for microscopy procedures.

Time Lapse in Vivo Image Acquisition

The muscle surface was viewed with a water immersion objective (20 × HCX APO, 0.5 numerical aperture; Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany) attached through a high speed nanofocusing Z-Drive (p-725.2CD, PIFOC; Physik Instrumente, Karlsruhe, Germany) to an upright microscope stage (Leica RXA2; Leica Microsystems). Recording of GFP and r-bgt fluorescence (50–60 optical sections in 500-nm intervals) was performed every 90 min over a course of 6 h as follows. Green and red fluorescence were excited by 488-nm and 568-nm laser lines, respectively (stack sequential illumination) and recorded through a 475-nm long pass filter with a cooled EMCCD camera (Cascade II; Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) attached to a Yokogawa CSU100 spinning disk module (Visitech, Sunderland, UK) using InVivo image acquisition software (MediaCybernetics, Bethesda, MD). Animals were euthanized after the procedure.

Imaging Quantification

All images were analyzed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA) and ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). Image stacks acquired at different time points were collapsed into maximum z-projections, and individual end plates were selected manually for quantitative analysis. The end plate area stained with r-bgt in the first image of the time series was considered to be the total surface (100% area) of the end plate occupied by AChRs. Fluorescence areas of r-bgt and γ-GFP signals were calculated individually at all time points for 6–8 en face end plates in 3 animals (n ≥14 end plates).

First, the area analysis method overcomes the drawbacks of inconsistent signal intensities, which arise due to preparation-specific fluctuations of fluorescence, when imaging structures in deep tissue layers. Second, we proved previously the validity of the area analysis approach for quantification of AChR dynamics, by showing that newly synthesized AChR incorporated into the end plate surface in a unidirectional fashion, proceeding from the periphery to the center (15, 29). Areas of red and green signal measurements in an end plate over time were compared with the initial area of that end plate.

Statistical Analysis

For statistical comparison of labeled receptor content change over time, a Student's t test was applied. A probability (p) equal to or less than 0.05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance when comparing area values.

For synchronicity assessment of receptor turnover, a k-nearest neighbor analysis of the calculated metabolic half-life values was performed.

Transversal Slices, Immunohistochemistry, Data Acquisition, and Analysis

Gastrocnemius muscles from C57BL/6J mice were explanted, washed in PBS (2.67 mm KCl, 1.47 mm KH2PO4, 137.93 mm NaCl, 8.06 mm Na2HPO4 x×7H2O), snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane, and then stored at −80 °C. Transversal slices of 10-μm thickness were made on a Leica CM1900 cryostat at −19 °C and placed on Superfrost slides (Labonord).

For staining, sections were moistened with PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min. After washing with PBS, slices were blocked with 10% FBS/PBS for 20 min. Then, slices were incubated with polyclonal LF-18 anti-myosin Va (Sigma) antibody overnight at 4 °C. After washing they were co-incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-rabbit antibody and Alexa Fluor 647 labeled α-bungarotoxin (both Invitrogen) for 2 h at room temperature. Slices were then washed with 10% FBS/PBS, PBS, and H2O and embedded in Mowiol (Calbiochem).

Confocal images were acquired with a DMRE TCS SP2 confocal microscope equipped with Confocal Software 2.61, a KrAr laser (488 nm), a HeNe laser (633 nm), and a HCX PL APO CS 63×/1.2 W CORP water objective (all Leica Microsystems). AF488 and AF647 fluorescence signals were excited at 488 nm and 633 nm, respectively. Emission was detected from 495–535 nm (AF488) and from 650 to 750 nm (AF647). Images were taken at 8-bit, 1024 pixels with two times line average.

Image analysis employed the ImageJ program. First, NMJs were segmented by thresholding AF647 signals (30–255). Then, for each detected NMJ the corresponding fiber was segmented, sparing the NMJ area. Subsequently, myosin Va mean signal intensity and S.D. values were determined in the NMJ and fiber segments. NMJs were counted as myosin Va-positive if the mean signal intensity in the NMJ segment was higher than the fiber background plus twice the signal S.D. in the fiber background.

RESULTS

Time Lapse in Vivo Imaging at Early Postnatal Stages

Our aim was to resolve in vivo changes in AChR stability and changes of receptor composition in individual NMJs. We chose the tibialis anterior muscle because the fibers at the surface of this muscle are easily accessible to microscopic in vivo inspection. One established method is to follow changes in fluorescence intensities of r-bgt-stained end plate receptors (11). The AChR labeled with nonsaturating concentrations of r-bgt (50 nm/5 min) blocks neurotransmission only partially without affecting the turnover of the receptors. The decrease in fluorescence intensities observed over time has been used to determine AChR stability at end plates (t½ ≈ 13 days). A one-time blockade (0.25 μm/30 min), on the other hand, causes an immediate loss of AChRs, reducing the stability to t½ <1 day. This low stability has not only been observed for pharmacologically blocked but also for extrasynaptic AChRs (1). With increasing time after blockade, however, the rate of AChR loss decreases again (1).

Until now, there have been no in vivo measurements on early postnatal end plate AChR, and it is not known how and at what time during postnatal development they acquire their high metabolic stability. Here, we overcome the technical difficulties of neonatal imaging by implementation of a newly developed setup for analyzing end plate AChR of the tibialis muscle (Fig. 1, A and B). Using a spinning disk microscope for fluorescence measurements, it is possible to minimize distortions caused by breathing and heart beat due to the high sensitivity and high speed imaging. We acquired a continuous series of microscopic images of groups of 15–20 neighboring end plates in 90-min intervals for 6 h after the initial pulse-labeling with r-bgt (see “Experimental Procedures”).

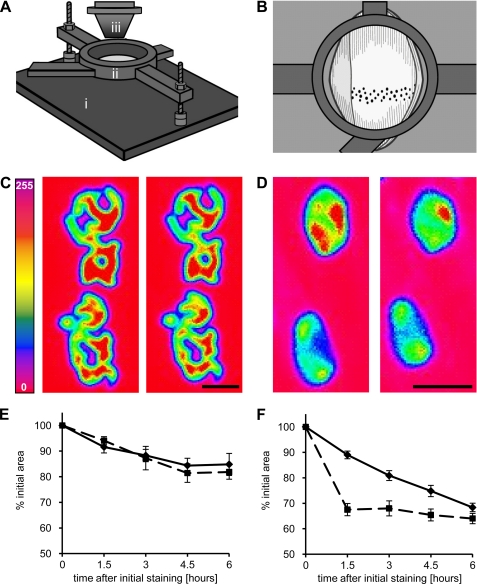

FIGURE 1.

Microscope setup for in vivo imaging of the tibialis anterior muscle in adult and newborn mice. A, microscope stage with its main components: adjustable steel contraption (i), objective immersion chamber (ii), and high speed nanofocusing PIFOC Z-Drive with an objective (iii). B, top view schematic drawing of the exposed limb (light gray) and tibialis muscle (white) when attached to the contraption. End plates are depicted as black. C and D, false color images of adult (C) and P6 newborn (D) end plates blocked with a one-time saturating dose of r-bgt. Left and right panels depict stained end plate surfaces at 0 and 6 h after the initial staining, respectively. Scale bars, 10 μm. E and F, change of area (solid lines) and fluorescence (dashed lines) values over time in adult (E) and P6 newborn (F) end plates, respectively. Data points are means ± S.E. (error bars; n = 17–25 end plates; three animals).

Because quantification of fluorescence intensity requires corrections for variable laser intensities and may vary during experiments, we decided to quantify end plate areas, instead. This is based on our observation that new receptors are added to the end plates from the periphery (15). So, after the initial labeling, new nonfluorescent AChRs are inserted, and the area of fluorescent receptors will decrease as a consequence of AChR loss. In Fig. 1, C and E, we analyze in vivo end plates of an adult mouse after labeling AChR one time with saturating r-bgt concentrations. Changes in AChR levels are followed by quantifying the fluorescence intensity or by evaluating the end plate area over a period of 6 h (see “Experimental Procedures”). As described by Akaaboune et al. (11) we observed initially a fast decrease of fluorescence, which became slower with continued observation, and decreased overall to 84.8 ± 4.3%. A similar decrease to 81.9 ± 2.8% was seen when measuring end plate areas. Thus, both fluorescence intensity as well as end plate area can serve as valid parameters to quantify the time-dependent loss of end plate receptors.

Neuromuscular blockade might affect AChRs at early postnatal stages different from adult AChRs due to their different metabolic stabilization. In Fig. 1, D and F, we analyze end plates in postnatal day 6 muscle. Employing again one-time saturating r-bgt concentrations, we saw over the 6-h observation time a decrease in end plate AChRs to 64.0 ± 2.0%, which is significantly lower than observed in adult muscle. In contrast to adult muscle, there was a consistent rapid loss of AChR over the period of analysis, indicating that most receptors have a fast turnover rate that is not increased further by toxin blockade.

Next, using nonsaturating r-bgt concentrations for end plate staining, we measured the apparent metabolic stability of the AChRs during postnatal development to determine the time point of transition from fast to slow AChR turnover. At present, it is unclear whether there is a correlation of AChR stabilization and the concurrent embryonic to adult AChR channel conversion. In the AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP mouse line we showed that the overall AChR channel conversion is largely completed by postnatal day 6, which is earlier than in wild type (15) (see below). This gives us the possibility to separate channel conversion from receptor stabilization temporally by comparing the stabilization process in mutant and wild type mice. We therefore measured AChR stability in dependence of postnatal development in this mouse line.

End Plate Receptor Stability

For 6 h, we followed the loss of AChRs in vivo from end plates after labeling with one-time nonsaturating concentrations of r-bgt. At each end plate the initial r-bgt-labeled area was taken as 100% of the end plate area, and changes were recorded continuously over the observation period.

The analysis of the metabolic stabilities of end plate AChRs at developmental stages P3 through P8 in AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP animals is shown in Fig. 2A. After 6 h of observation, the mean r-bgt-stained end plate area was reduced to 55.4 ± 5.4% (n = 21) of the initially stained area on P3 and to 68.6 ± 5.7% (n = 23) in the end plates at P4. These depletion rates of the end plate receptor population correspond to metabolic half-life times of t½ = 7.1 h and t½ = 10.5 h for total end plate receptor content in 3- and 4-day-old animals, respectively.

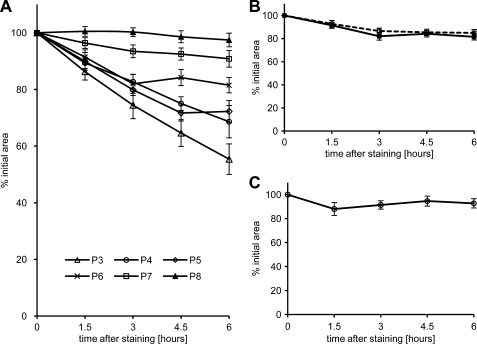

FIGURE 2.

Age-dependent receptor stabilization. A, time course of r-bgt-stained end plate area change over time in AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP animals from P3 through P8. Data points represent mean values of each of the five measurements: 0, 1.5, 3, 4.5, and 6 h after initial staining. Error bars are ± S.E. (n = 14–23 end plates; three or four animals). B, comparison of the change in r-bgt-stained area in P6 wild type (dashed line) and AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP (solid line) animals over the course of 6 h. Data points are means ± S.E. (error bars; n = 14–19 end plates; three or four animals). C, change of the r-bgt-stained end plate area over time in P30 AChRϵ−/− animals. Data points are means ± S.E. (n = 14 end plates; three animals).

The detectable fluorescence of the initially labeled r-bgt receptor area after 6 h was reduced to 72.3 ± 3.8% (n = 23) in P5 and to 81.5 ± 2.7% (n = 19) in P6 animals. This corresponds to a net metabolic stability of t½ = 10.3 and 15.1 h on P5 and P6, respectively. Virtually no change was measured in the analysis of the r-bgt-stained areas of P7 and P8 end plates remaining at 90.8 ± 3.0% (n = 14) and 97.4 ± 2.4% (n = 14), respectively, after 6 h. Therefore, after day P8, estimation of receptor metabolism over 6 h is difficult due to the increasing stability of end plate AChRs population around this age. Further experiments on days P10 and P23 showed that this stabilization becomes permanent (data not shown), and no change in r-bgt labeled end plate receptor population could be measured during a 6-h imaging session after the initial AChR staining.

Comparison of AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP with Wild Type and AChRϵ−/− Lines

The estimated mean total content of adult AChRϵ (<50%) in wild type animals on P6 is significantly lower than the AChRϵ content (75.8 ± 3.8%) in end plates of AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP animals on the same postnatal day (15, 16). To address the possible influence of the untimely γ-to-ϵ conversion in the AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP line on end plate receptor stabilization we compared animals 6 days of age from both wild type and AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP lines. The results revealed a striking similarity between the two animal lines with a mean metabolic half-life time of 15.1 h for P6 AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP animals and 15.2 h for end plates of wild type mice (Fig. 2B). Given the premature overall channel conversion around P4 in AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP animals, this analysis indicates that the time point of the γ-to-ϵ switch and receptor depletion properties of the end plate are not correlated.

To corroborate further the finding that the γ-to-ϵ switch is not crucial for AChR stabilization and to investigate whether the ϵ subunit plays any role in this process, we next analyzed AChRϵ−/− mice that express exclusively the embryonic AChRγ throughout life (17). Notably, the stained end plate AChR content in P30 animals declined merely to 92.7 ± 3.9% of the initial r-bgt-stained area after 6 h, displaying a high degree of stability in the absence of adult AChRϵ (Fig. 2C).

Asynchronous Receptor Internalization in Individual Muscle Fibers

Using the same quantification method, we assessed all analyzed end plates for differences in the loss of r-bgt-labeled AChRs over the entire observation period. P3 end plates (Fig. 3, A–E, labeled with arrows) displayed rather heterogeneous AChR stabilities with an average half-life of t½ = 7.1 h. The nearest neighbor index (Rn) of 0.8<Rn<1.1 for the assessed time points suggest a fairly random distribution of the t½ values among different end plates. The heterogeneity, however, did not correlate with the AChR composition of individual end plates because we found, on one side, end plates having comparable AChRγ-GFP contents with significantly different loss of end plate AChRs as well as vastly different AChRγ-GFP contents with similar loss of end plate AChRs (data not shown). With progressing age the average AChR stability increased to t½ = 15.1 h at P6 with small, but significant amounts of AChR having a half-life of several days already (Fig. 3F). The first stabilized end plates (t½ ≥10 days) appeared on P7 as reflected by the wide distribution of AChR half-lives among the individual end plates at this stage (Fig. 3F). At P8 and older, AChR turnover became consistently slow for all end plates (Fig. 3F).

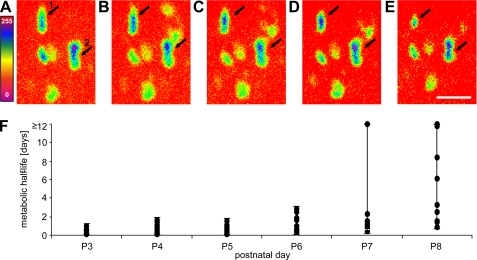

FIGURE 3.

Change of stained end plate receptor area over time. A–E, false color image crops of r-bgt-stained end plates of a P3 AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP animal at 0, 1.5, 3, 4.5, and 6 h after initial staining. Upper and lower black arrows point to the same two representative en face end plates (1 and 2) in each panel. Labeled AChR areas of end plates 1 and 2 after 6 h are 20.7% and 41.6% of their original areas, respectively. A rainbow color scheme in which red color marks the lowest and purple color the highest intensities was applied (scaled intensity from 0 to 255). Scale bar, 10 μm. F, distribution of metabolic half-life values within the end plate populations from postnatal day P3 throughout P8. Data points represent individual end plates at each given time point. Whisker bars show the range of t½ values at each age, making no assumptions on underlying statistical distributions.

These findings show that AChR stabilization occurs asynchronously among neighboring muscle fibers and proceeds independently in the individual end plates within hours. It is of interest to note that stabilization increased dramatically from hours to days between P6 and P8.

Postnatal Enrichment of Myosin Va in the NMJ Region

We have recently shown a principal role of myosin Va for the maintenance of the NMJ and for the proper turnover of AChR in adult end plates (14). Therefore, we investigated whether myosin Va could be a molecular factor participating in the stabilization pathway in the early postnatal period. First, we analyzed the expression pattern of myosin Va in hind limb muscles at different ages, from P1 to adult. Myosin Va and AChR were labeled with LF-18 antibody and bgt-AF647, respectively (see “Experimental Procedures”). Confocal image analysis in gastrocnemius muscles from wild type mice showed a clear, age-dependent enrichment of myosin Va at the NMJ (Fig. 4A). On P1 myosin Va, immunofluorescence signals were detected throughout the fibers, but were hardly stronger at the NMJ site. On P7, myosin Va was still spread all over the fiber, but also started to accumulate at the synaptic site. From P16 onward, most fibers exhibited very strong accumulation of myosin Va at the NMJ of wild type animals and close to zero signal in the central portions of the fibers. This is well reflected by quantitative analysis showing <10% of myosin Va-positive NMJs at P1 and >80% in adult animals (Fig. 4B). With progressing age of the animal the difference in myosin Va staining intensity in the NMJ region versus the rest of the fiber increased continuously (Fig. 4C). Very similar results were also obtained for other muscles, such as tibialis anterior and triceps brachii (data not shown). This shows that myosin Va enriches in the NMJ region in parallel to the occurrence of early postnatal AChR stabilization, suggesting a role of the motor protein in this process.

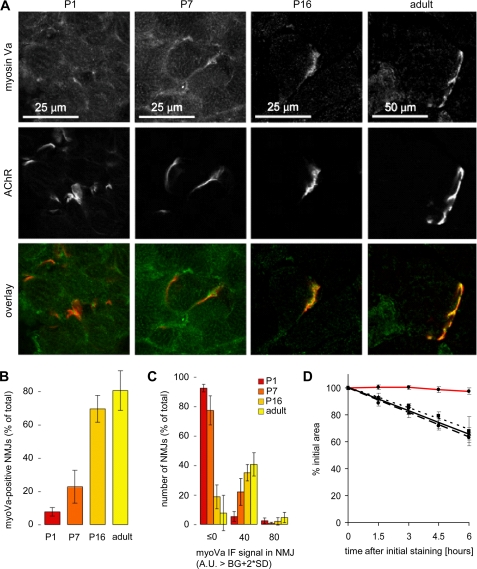

FIGURE 4.

Myosin Va enrichment in the NMJ region occurs in the early postnatal period. Wild type gastrocnemius muscles were sampled on P1, P7, P16, and from adult mice. Transversal muscle sections were stained against myosin Va and AChR and imaged with confocal microscopy. A, representative optical sections. Shown are myosin Va immunofluorescence (myosin Va), bgt-AF647 staining (AChR), and the overlay of both. In the overlay images myosin Va and bgt-AF647 signals are depicted in green and red, respectively. Overlapping signals with similar intensity are yellow. B, quantitative analysis showing the amount of NMJs exhibiting significant enrichment of myosin Va signals. Data show mean ± S.E. (error bars; n = 3 mice; for each time point at least 160 NMJs were analyzed). C, quantification of the intensity distribution of the synaptic myosin Va signals significantly exceeding the fiber background. Data show immunofluorescence (IF) signal (arbitrary units, A.U.) in NMJs that are higher than background (BG) plus two times S.D. in muscle section (same data set as in B). D, comparative time courses of the changes of r-bgt-stained end plate area over 6 h in vivo observation in P8 (dashed line), P10 (solid line), and P14 (dotted line) homozygous dilute and P8 AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP animals (red line). All data points are mean values ± S.E. (error bars; n = 14–21 end plates; three animals for each time point).

Lack of Metabolic Receptor Stabilization in Myosin Va-deficient Mice

Next, we examined the metabolic stabilization of AChR in the early postnatal phase of dilute-lethal mice, which lack functional myosin Va due to a naturally occurring spontaneous mutation of the dilute locus (26). Homozygous animals used for this set of experiments were phenotyped by typical characteristics, namely silvery fur color and seizures. Performing the in vivo r-bgt pulse-label imaging approach revealed that metabolic stabilization of AChR was almost completely missing in all dilute specimens (Fig. 4D). The mean decline of the initial r-bgt-stained end plate area in dilute animals on P8, P10, and P14 was 65.6 ± 1.4% after 6 h. This value was very similar to P4 in wild type or AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP end plates and differed significantly from the previously obtained value of 95.1 ± 2.0% for P8 AChR γ-GFP/γ-GFP animals. Thus, the level of net receptor stability corresponded to a mean metabolic half-life of t½ = 9.9 h for end plate receptors of the dilute animals. Notably, the rate of r-bgt-labeled end plate receptor area loss did not vary significantly among the analyzed NMJs of the dilute animals and did not change with the age of the animal.

DISCUSSION

It has been long known that AChR metabolic stability is significantly increased in mature synapses (1). The onset of this stabilization causing an apparent loss of plasticity, however, is still poorly understood. Here, we analyze for the first time the stability of end plate receptors in genetically different mouse lines using a high speed image acquisition to resolve in vivo trafficking of AChRs to the postsynaptic membrane of the developing NMJ.

Existing in vivo microscopy methods employ a series of distinct short imaging sessions with repetitious cycles of anesthesia and surgery (18). Apart from the inaccessibility of neonatal stages before P7, great stress to the animal, and formation of inflammatory scar tissue, it is also unwieldy to identify the same region of interest in every reimaging session. Here, we introduce a new method that allows one to obtain continuous time lapse in vivo images from a selected region of easy accessible leg muscles. This approach could be also used for any other muscle or tissue. The condition of the animals remains stable over a period of at least 8 h after a single injection of anesthetics, a time that might be even extended, if necessary. This method is especially attractive for rapid time lapse visualization of developmentally relevant processes in early neonatal stages.

Our setup allows one to capture series of consecutive high resolution microscopic images of a large tissue area over a period of several hours in a living, anesthetized animal. Image stacks are recorded by a highly sensitive cooled EMCCD camera, which is attached to a spinning disk confocal microscope and features short frame integration times and whole image acquisition at low laser excitation intensities. Compared with normal confocal microscopy artifacts caused by photodamaging can be minimized. In addition, the tissue is fixated tightly to the rigid contraption structure and does not require user interaction after the initial preparation. These properties of the experimental configuration significantly reduce imaging artifacts resulting from tissue movement within a single image or between images of a stack due to cardiac and respiratory activity. As such, the setup overcomes common difficulties associated with in vivo imaging of deep tissue in small anesthetized animals and provides a powerful microscopy tool for every scientific field, which requires high spatiotemporal resolution in vivo imaging.

Using this method we observe that the loss of AChR from one-time labeled end plates results in a decrease of r-bgt-stained end plate area, supporting the observation that newly synthesized receptors are added to the periphery of end plates (15). Therefore, it is possible to follow changes in AChR stability by quantifying end plate areas over time instead of fluorescence intensities, which are more prone to experimental variation.

We introduced the AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP earlier as a model organism for tracking developmental events, such as the γ-to-ϵ subunit and AChR conversion at the NMJ (15), which appears to proceed within hours in a fiber type-specific manner. The in vivo analysis here shows that the stabilization of AChRs at individual end plates proceeds also unsynchronized among end plates of the same age and in the same muscle. Fiber-specific regulatory signals could modulate directly structural and/or functional properties of the AChRs. Because receptor stabilization, γ-to-ϵ subunit switch, and channel conversion occur postnatally, it had been assumed that AChR subunit composition confers the metabolic properties of AChRs. To decide whether there is any correlation, one needs to know the precise temporal occurrence of postnatal AChR stabilization, which has not been determined so far.

With our in vivo imaging method, using one-time nonsaturating conditions, we have been able to determine the time point of transition from “instable” to “stabilized” end plate AChRs. The stabilization of AChR at the end plate started around P3 and increased dramatically between P6 and P8, when it was no longer possible to determine significant changes at NMJs within the 6-h observation time. Although this transition seems to coincide with AChR subunit and channel conversion, our results show that AChR subunit composition has no effect on receptor stability. We find that the ratio of embryonic to adult receptors at individual end plates does not correlate with the decreasing loss rates of end plate receptors. Accordingly, the stability of end plate receptors at P6 shows no significant difference comparing AChRγ-GFP/γ-GFP and wild type mice. We demonstrated previously that the embryonic receptors of AChR γ-GFP/γ-GFP mice are largely depleted from the NMJ at P6 (15), whereas wild type mice still contain >50% of embryonic AChR at that stage (16, 19). Finally, AChRs in mature NMJs of AChRϵ−/− animals at P30 have a stability similar to that of AChRs in wild type mice of the same age, although they lack adult-type AChRϵ and express embryonic-type AChRγ throughout life.

The observed age-dependent change in AChR stability could result from a recycling pathway (11). Factors such as Cdk5, c-Src, Rac1, and the actin cortex have been shown to participate in AChR turnover at the postsynaptic membrane (20–22) and may also play a role in AChR recycling. Recently, myosin Va, an actin-associated motor protein that is known for its docking factor activity in vesicular and organelle transport in neurons (23–25), has been shown to co-localize with postsynaptic NMJ structures, and its role in synaptic plasticity was elucidated (14).

The NMJs of myosin Va-deficient dilute animals (26) are inconspicuous in early postnatal stages, but they decrease continuously in size after P8, until the morphology and the functionality of the end plate are abolished (14), which leads to premature lethality around P21.

Our analysis of the dilute mouse line revealed that these animals fail to accumulate myosin Va at the synapse and also do not undergo further AChR stabilization after P4. It is therefore possible that myosin Va facilitates the recycling pathway as a capturing factor, which retains the vesicles containing internalized AChR in the end plate proximity and increases their probability of being reinserted into the synaptic membrane. In addition, myosin Va and other actin cortex proteins might reinforce the surface-connected compartments into which AChR are first sequestered (22). Taken together, the results suggest that myosin Va activity contributes significantly to the developmentally regulated recycling-induced stabilization of receptors during synaptic maturation.

Developmental stabilization of AChR involving a recycling process ensures stable and reliable neurotransmission at the expense of plasticity, which is needed to form muscle-specific end plate structures (27–29) and allow end plate receptors to adapt rapidly to altered synaptic activity states, e.g. following pharmacological blockade by toxins or surgical denervation (11, 29, 30). On the basis of these observations one might ask, why are receptors stabilized only after birth?

During embryonic development abundant AChR expression allows the establishment of correctly localized functional synapses. Dispersal of extrasynaptic receptors, changes in the transcriptional control of the receptor subunit genes, and channel conversion contribute to the functional and anatomical specialization of the synapses. Further refinement requires synaptic stabilization and is mediated by muscle-specific postnatal differentiation. This process may be called long term potentiation, in analogy to changes observed in the central nervous system. A recycling pool of AChR could serve not only as a quality control check point, in which the decision for reinsertion of intact receptors or possible degradation of damaged or toxin-inactivated receptors (e.g. by bungarotoxin or curare) is made but also how long receptors are kept recycling. The machinery for such a stabilization process may depend on the maturation of the synaptic actin cortex that is achieved gradually in early neonatal stages as the localized accumulation of integral components such as myosin Va increases.

A stabilized end plate does not require the receptor proteins to be expressed constantly at full capacity and the muscle cell can adjust synaptic strength by increasing receptor expression levels upon acute demand, such as in the case of neuronal signal impairment by denervation or botulinum toxin. Thus, the basally low supply of receptors creates a safety factor for synaptic transmission, allowing modulations of synaptic strength and facilitates plasticity throughout adulthood.

Footnotes

- AChR

- acetylcholine receptor

- NMJ

- neuromuscular junction

- r-bgt

- rhodamine-labeled α-bungarotoxin

- P

- postnatal day.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fambrough D. M. (1979) Physiol. Rev. 59, 165–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeChiara T. M., Bowen D. C., Valenzuela D. M., Simmons M. V., Poueymirou W. T., Thomas S., Kinetz E., Compton D. L., Rojas E., Park J. S., Smith C., DiStefano P. S., Glass D. J., Burden S. J., Yancopoulos G. D. (1996) Cell 85, 501–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okada K., Inoue A., Okada M., Murata Y., Kakuta S., Jigami T., Kubo S., Shiraishi H., Eguchi K., Motomura M., Akiyama T., Iwakura Y., Higuchi O., Yamanashi Y. (2006) Science 312, 1802–1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckler S. A., Kuehn R., Gautam M. (2005) Neuroscience 131, 661–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borges L. S., Yechikhov S., Lee Y. I., Rudell J. B., Friese M. B., Burden S. J., Ferns M. J. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 11468–11476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gervásio O. L., Armson P. F., Phillips W. D. (2007) Dev. Biol. 305, 262–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg D. K., Hall Z. W. (1974) Science 184, 473–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang C. C., Huang M. C. (1975) Nature 253, 643–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinbach J. H., Merlie J., Heinemann S., Bloch R. (1979) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 76, 3547–3551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salpeter M. M., Cooper D. L., Levitt-Gilmour T. (1986) J. Cell Biol. 103, 1399–1403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akaaboune M., Culican S. M., Turney S. G., Lichtman J. W. (1999) Science 286, 503–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Correia S. S., Bassani S., Brown T. C., Lisé M. F., Backos D. S., El-Husseini A., Passafaro M., Esteban J. A. (2008) Nat. Neurosci. 11, 457–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z., Edwards J. G., Riley N., Provance D. W., Jr., Karcher R., Li X. D., Davison I. G., Ikebe M., Mercer J. A., Kauer J. A., Ehlers M. D. (2008) Cell 135, 535–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Röder I. V., Petersen Y., Choi K. R., Witzemann V., Hammer J. A., 3rd, Rudolf R. (2008) PLoS One 3, e3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yampolsky P., Gensler S., McArdle J., Witzemann V. (2008) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 37, 634–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yumoto N., Wakatsuki S., Sehara-Fujisawa A. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 331, 1522–1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Witzemann V., Schwarz H., Koenen M., Berberich C., Villarroel A., Wernig A., Brenner H. R., Sakmann B. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 13286–13291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turney S. G., Lichtman J. W. (2008) Methods Cell Biol. 89, 309–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Missias A. C., Chu G. C., Klocke B. J., Sanes J. R., Merlie J. P. (1996) Dev. Biol. 179, 223–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sadasivam G., Willmann R., Lin S., Erb-Vögtli S., Kong X. C., Rüegg M. A., Fuhrer C. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 10479–10493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin W., Dominguez B., Yang J., Aryal P., Brandon E. P., Gage F. H., Lee K. F. (2005) Neuron 46, 569–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumari S., Borroni V., Chaudhry A., Chanda B., Massol R., Mayor S., Barrantes F. J. (2008) J. Cell Biol. 181, 1179–1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bridgman P. C. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 146, 1045–1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lalli G., Gschmeissner S., Schiavo G. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 4639–4650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desnos C., Huet S., Darchen F. (2007) Biol. Cell 99, 411–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mercer J. A., Seperack P. K., Strobel M. C., Copeland N. G., Jenkins N. A. (1991) Nature 349, 709–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prakash Y. S., Sieck G. C. (1998) Muscle Nerve 21, 887–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos A. F., Caroni P. (2003) J. Neurocytol. 32, 849–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yampolsky P., Pacifici P. G., Witzemann V. (2010) Eur. J. Neurosci. 31, 646–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruneau E., Sutter D., Hume R. I., Akaaboune M. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 9949–9959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gensler S., Sander A., Korngreen A., Traina G., Giese G., Witzemann V. (2001) Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 2209–2217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]