Abstract

The PDZ1 domain of the four PDZ domain-containing protein PDZK1 has been reported to bind the C terminus of the HDL receptor scavenger receptor class B, type I (SR-BI), and to control hepatic SR-BI expression and function. We generated wild-type (WT) and mutant murine PDZ1 domains, the mutants bearing single amino acid substitutions in their carboxylate binding loop (Lys14-Xaa4-Asn19-Tyr-Gly-Phe-Phe-Leu24), and measured their binding affinity for a 7-residue peptide corresponding to the C terminus of SR-BI (503VLQEAKL509). The Y20A and G21Y substitutions abrogated all binding activity. Surprisingly, binding affinities (Kd) of the K14A and F22A mutants were 3.2 and 4.0 μm, respectively, similar to 2.6 μm measured for the WT PDZ1. To understand these findings, we determined the high resolution structure of WT PDZ1 bound to a 5-residue sequence from the C-terminal SR-BI (505QEAKL509) using x-ray crystallography. In addition, we incorporated the K14A and Y20A substitutions into full-length PDZK1 liver-specific transgenes and expressed them in WT and PDZK1 knock-out mice. In WT mice, the transgenes did not alter endogenous hepatic SR-BI protein expression (intracellular distribution or amount) or lipoprotein metabolism (total plasma cholesterol, lipoprotein size distribution). In PDZK1 knock-out mice, as expected, the K14A mutant behaved like wild-type PDZK1 and completely corrected their hepatic SR-BI and plasma lipoprotein abnormalities. Unexpectedly, the 10–20-fold overexpressed Y20A mutant also substantially, but not completely, corrected these abnormalities. The results suggest that there may be an additional site(s) within PDZK1 that bind(s) SR-BI and mediate(s) productive SR-BI-PDZK1 interaction previously attributed exclusively to the canonical binding of the C-terminal SR-BI to PDZ1.

Keywords: Cholesterol, Cholesterol Regulation, Crystal Structure, Protein Structure, Receptor Regulation, HDL, PDZ Domains, PDZK1, SR-BI

Introduction

Protein interaction domains fold into stable, at least partially autonomously functioning, modular domains that mediate a wide variety of protein-protein interactions and appear to have played major roles in evolution. One of the most abundant of such domains in mammals is the PDZ (PSD-95/Discs-large/ZO-1) family of domains, with more than 250 members found in over 100 proteins in the human genome (1). PDZ domains are composed of ∼80–100 amino acids and fold into compact globular structures that usually contain six β-strands and two α-helices (2). PDZ domains often interact with the five C-terminal amino acids of their binding partners (target peptides), and the C-terminal residue is often hydrophobic, although some can interact with as many as seven residues of the C terminus of their targets (3). Many PDZ domain-containing proteins have multiple PDZ domains and thus can promote clustering or scaffolding of target proteins and can be involved in a wide variety of cellular functions (4).

One such multifunctional protein is PDZK1 (5). PDZK1, a four PDZ domain-containing protein, is involved in the regulation of several membrane-associated proteins such as ion channels and cell-surface receptors (6–8). For example, PDZK1 plays a key role as a tissue-specific adaptor that controls the hepatic activity of the high density lipoprotein (HDL) receptor called scavenger receptor class B, type I (SR-BI)3 (9, 10).

SR-BI is a 509-amino acid integral membrane, cell surface glycoprotein with two transmembrane domains, a large extracellular loop, and very short cytoplasmic N and C termini (10). SR-BI, which mediates the binding of HDL and other lipoproteins to cells and the consequent transfer of cholesterol, is most highly expressed in the liver and steroidogenic tissues, and it can be found in a variety of other tissues and cells (e.g. macrophages and endothelial cells). In addition to transporting cholesterol between lipoproteins and cells, SR-BI can function as a signaling receptor in endothelial cells, mediating the activation of intracellular signaling pathways in response to extracellular HDL (11–14). Studies in mice have shown that SR-BI, particularly its expression in the liver, plays an important role in controlling lipoprotein metabolism (10). Inactivation of the SR-BI gene results in an ∼2.2-fold elevation of plasma cholesterol in the form of abnormally large HDL particles in SR-BI KO mice (15). Studies with transgenic mice have shown that SR-BI can influence gastrointestinal, endocrine, reproductive, and cardiovascular physiology and protect against female infertility, certain blood disorders, and atherosclerosis (10, 16–22). The regulation of hepatic SR-BI protein expression and function is of interest both because of its role in physiology and because of its potential as a target for the prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia and atherosclerotic disease.

In 2000, Ikemoto et al. (23) reported that PDZK1 can bind in vitro to the cytoplasmic C terminus of SR-BI via its most N-terminal PDZ domain, PDZ1, and suggested that PDZK1 may play an important role in controlling SR-BI in vivo. Subsequent studies in transgenic and knock-out (KO) mice have established that PDZK1 has a profound influence on SR-BI protein expression and function in some tissues and that it is a tissue-specific adaptor for SR-BI (9, 11–14). In mice with homozygous inactivation of the PDZK1 gene (PDZK1 KO mice), there is a 95% decrease of expression of SR-BI protein in hepatocytes, a 50% reduction in small intestinal mucosa, but no change in the steroidogenic cells of the adrenal cortex, testes, or ovaries (9) or in macrophages (24). The dramatic reduction in hepatic SR-BI protein expression in PDZK1 KO mice leads to an ∼70% increase in total plasma cholesterol in the form of abnormally large HDL particles, a phenotype similar to but not as severe as that in SR-BI KO mice (9). Indeed, normal expression of PDZK1 is athero- and cardio-protective in the apoE KO mouse model of atherosclerosis, presumably because it is necessary for normal hepatic SR-BI expression (24, 25).

The detailed mechanism by which PDZK1 controls hepatic SR-BI protein expression has not been fully elucidated. Studies in PDZK1 KO mice have shown that the influence of PDZK1 on hepatic SR-BI is post-transcriptional (9) and that PDZK1 influences its intracellular distribution as well as the steady-state levels of hepatic SR-BI in vivo (9, 26, 27). Hepatic transgenic overexpression experiments involving serial C-terminal truncation mutants of PDZK1 have shown that all four PDZ domains of PDZK1 are necessary for normal hepatic expression, localization, and function of SR-BI (26), although previous studies suggested that SR-BI interacts directly with only its PDZ1 domain (23).

Here, we have examined further the role of the PDZ1 domain in PDZK1 control of hepatic SR-BI protein expression and function in vitro and in vivo. We generated recombinant PDZ1 domains, wild-type and mutants carrying single amino acid substitutions in the PDZ1 carboxylate binding loop (CBL) (Lys14-Xaa4-Asn19-Tyr-Gly-Phe-Phe-Leu24), that were designed to interfere with PDZ1-SR-BI target peptide binding. We used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to measure SR-BI target peptide (503VLQEAKL509) binding to these recombinant proteins. We also determined the high resolution crystal structure of wild-type PDZ1 bound to its SR-BI target peptide to better understand the interaction and the effects of the amino acid substitutions on target peptide binding in vitro (two mutations abrogated binding and two had little effect). We incorporated two of the PDZ1 single residue substitutions, K14A (essentially normal target peptide binding, PDZK1(K14A)) and Y20A (no binding, PDZK1(Y20A)) into full-length PDZK1 expression constructs and used them to generate transgenic WT and PDZK1 KO mice with liver-specific expression of the transgenes. Unexpectedly, analysis of hepatic SR-BI protein expression (intracellular distribution and amount) and lipoprotein metabolism (total plasma cholesterol and plasma lipoprotein size distribution) in these and control animals suggests that interruption of SR-BI binding to PDZ1 only partially interferes with the ability of overexpressed PDZK1 to control SR-BI expression and lipoprotein metabolism. Thus, PDZK1 may have one or more binding sites for SR-BI in addition to the canonical site on PDZ1.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of Full-length Mutant PDZK1 Transgenic Expression Vectors

PDZK1 K14A, Y20A, G21Y, and F22A mutations were produced using a PDZK1/pLiv-LE6 recombinant plasmid and the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene according to the manufacturer's protocol. Oligonucleotide primers containing the mutations were synthesized and PAGE-purified by Integrated DNA Technologies. The sequences of the resulting plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Protein Production and Purification

PCR fragments corresponding to WT and mutated first PDZ domain of PDZK1, PDZ1 (K14A, Y20A, G21Y, and F22A), were cloned into a modified pMAL-c2x vector (New England Biolabs) and expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells to produce maltose-binding fusion proteins carrying an N-terminal hexahistidine tag or into pGEX-4T-3 and expressed in E. coli JM109 cells to produce glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins. The expressed proteins were purified on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen) or glutathione-Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) and released by digestion with either human rhinovirus 3C (HRV3C) or thrombin proteases. The recombinant proteins (residues 7–116 of PDZK1) included the first PDZ domain of PDZK1 (residues 7–86) and 31 residues from the region of the protein between the PDZ1 and PDZ2 domain (interdomain residues 87–116). The isolated recombinant proteins (111 residues total) contained a glycine residue (encoded by the cloning vector) at the N termini that is not normally present in PDZK1. The recombinant proteins were further purified by fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) using a Superdex S75 column (GE Healthcare) and were shown to be homogeneous using SDS-PAGE.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

Binding constants for interaction of WT and mutated PDZ1 domains with a SR-BI 7-mer C-terminal peptide (503VLQEAKL509) were measured using a VP-ITC microcalorimeter (GE Healthcare). The SR-BI peptide was synthesized and purified by HPLC at the Tufts University Core Facility (Boston). Briefly, 0.18 to 0.6 mm SR-BI peptide was titrated against PDZ1-derived recombinant proteins at concentrations between 0.01 and 0.03 mm in a buffer containing 150 mm NaCl, 25 mm Tris, pH 8.0, at 20 °C under reducing conditions (0.5 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine). Titration curves were analyzed and Kd values determined using ORIGIN 5.0 software (Origin Lab). Protein and peptide concentrations were determined by quantitative amino acid analysis (Dana Farber Molecular Biology Core Facility) and absorption spectroscopy (280 nm).

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of recombinant WT PDZ1 and Y20A PDZ1 mutant proteins (40 μm in PBS, 1 mm DTT, pH 7.4) and protein-free buffer controls were collected in 1-nm steps with an averaging time of 1 s from 280 to 200 nm at 20 °C using an Aviv circular dichroism spectrometer model 202 (Aviv, Lakewood, NJ) kindly made available by Amy Keating (Biology Department, MIT) and a strain-free quartz cell with a path length of 0.1 cm (Hellma, Plainview, NY). The samples were slowly shifted to 70 °C and then the spectra were re-collected. The spectra presented represent background-corrected values in which the buffer control data were subtracted from the observed spectra for the protein-containing samples.

Crystallography

A PCR-generated DNA fragment encoding the chimeric PDZ1-SR-BI recombinant protein (residues 7–106 of PDZK1, including the first PDZ domain of PDZK1 (residues 7–86), 20 residues from the region of the protein between the PDZ1 and PDZ2 domain (interdomain residues 87–106) and, fused to the C terminus of this interdomain segment, the five C-terminal amino acids of SR-BI (505QEAKL509), was cloned into a modified pMAL-c2x vector. In addition, a serine was substituted by site-directed mutagenesis for Cys10 to prevent disulfide bond formation. The recombinant protein was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells, purified on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin, and released from the maltose-binding protein by HRV3C protease digestion and further purified by FPLC using a Superdex S75 column. The isolated, recombinant protein (106 residues total) contains a glycine residue (from the cloning vector) at the N terminus that is not normally present in PDZK1. After screening for optimal crystallization conditions using the polyethylene glycols (PEGs) suite (Qiagen), the PDZ1-SR-BI chimera at 1 mm concentration was crystallized by the sitting drop vapor diffusion method at 18 °C in a well containing 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, and 40% (v/v) PEG 200. Crystals were flash-frozen directly in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected on beamline X12C at the National Synchrotron Light Source (Brookhaven National Laboratory, New York). The crystals belong to space group P212121 with unit cell dimensions of a = 35.6, b = 55.1, and c = 111.1 Å. The data were reduced and merged using the HKL2000 suite (Table 1) (28).

TABLE 1.

Crystal structure of the PDZ1-SR-BI chimera, structure determination and refinement statistics

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P212121 |

| Unit cell | a = 35.6 Å, b = 55.1 Å, c = 111.1 Å |

| Wavelength | 1.1 Å |

| Resolutiona | 100.0 to 1.65 Å (1.86 to 1.65 Å) |

| Completeness | 97.5% (91.7%) |

| Total observations | 279,182 |

| Unique observations | 26,518 |

| Redundancy | 10.5 (5.8) |

| Rsym | 5.6 (54.5) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 41.1 (3.7) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution | 29.9 to 1.80 Å |

| Rcryst | 20.0% |

| Rfree | 23.8% |

| Root mean square bond lengths | 0.022 Å |

| Root mean square bond angles | 1.851° |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Preferred/allowed/outliers | 93.5, 6.5, 0.0% |

a Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell (1.86 to 1.65 Å). Rsym = Σ|I − 〈I〉|/Σ(I), where I is the observed integrated intensity, 〈I〉 is the average integrated intensity obtained from multiple measurements, and the summation is over all observable reflections. Rcryst = Σ‖Fobs|−k|Fcalc‖/Σ|Fobs|, where Fobs and Fcalc are the observed and calculates structure factors, respectively. Rfree is calculated as Rcryst using 5% of the reflection chosen randomly and omitted from the refinement calculations. Bond lengths and angles are root-mean-square deviations from ideal values.

Structure Determination and Refinement

The structure of the PDZ1-SR-BI chimera was solved by molecular replacement with PHASER (29) using the NMR structure of murine PDZK1 PDZ1 (Protein Data Bank code 2EDZ) as the search model. Refinement was carried out with REFMAC5 (30), and model building and addition of water molecules were performed manually using Coot (31). The final model contains 1701 protein atoms and 187 water molecules. The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank as code 3NGH.

Animals

All animal experiments were performed according to IACUC guidelines. All mice were on a 25:75 FVB/N:129SvEV genetic background and were maintained on a normal chow diet (32), and ∼6–8-week-old male mice were used for experiments. All procedures on transgenic and nontransgenic mice were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Committee on Animal Care.

Transgenic mice were generated for the K14A and Y20A PDZK1 mutants using the pLIV-LE6 plasmid, kindly provided by Dr. John M. Taylor (Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease, University of California, San Francisco). The pLiv-LE6 plasmid contains the promoter, first exon, first intron, and part of the second exon of the human apoE gene, the polyadenylation sequence, and a part of the hepatic control region of the apoE/C-I gene locus (33). These constructs were linearized by SacII/SpeI digestion, and the resulting 7.3-kb constructs were used to generate transgenic mice using standard procedures (34).

Founder animals for these transgenes in an FVB/N genetic background were identified by PCR performed on tail DNA using the following oligonucleotide primers: one at the 3′-end of the PDZK1 cDNA (GCAGATGCCTGTTATAGAAGTGTGC) and one corresponding to the 3′-end of the human apoE gene sequence included in the cloning vector (AGCAGATGCGTGAAACTTGGTGA). Founders expressing PDZK1 transgenic mutants were crossed with PDZK1 KO mice (129SvEv background). Heterozygous pups expressing the transgenes were crossed with WT and PDZK1 KO mice to obtain transgenic and control nontransgenic WT and PDZK1 KO mice, thus ensuring that the mixed genetic backgrounds of experimental and control mice in each founder line were matched. PDZK1 KO mice were genotyped as described previously (32). Two independent founder lines for K14A-Tg and three independent founder lines for Y20A -Tg were generated.

Blood and Tissue Sampling, Processing, and Analysis

Plasma and liver samples were collected and processed, and total plasma cholesterol levels and individual size-fractionated FPLC cholesterol profiles were obtained as described previously (27). Plasma cholesterol results presented here for transgenic mice were pooled from data collected from animals derived from all five founder transgenic animals.

For immunoblotting, protein samples (∼30 μg) from total liver lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and incubated with either a rabbit polyclonal anti-SR-BI anti-peptide antibody (mSR-BI495–112) (1:1000) or a rabbit polyclonal anti-PDZK1 anti-peptide antibody (1:30,000) (27), followed by an anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Invitrogen, 1:10,000) and visualized by ECL chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare). Immunoblotting using a polyclonal anti-ϵ-COP (1:5000) (35) antibody was used for loading controls. The relative amounts of proteins were determined by quantitation using a Kodak Image Station 440 CF and Kodak 1D software. Multiple independent determinations of band intensities from serially diluted samples were made to ensure that the intensities were both in the linear range of the detector and reproducible.

Immunoperoxidase Analysis

Livers were harvested, fixed, and frozen, and 5-μm sections were stained with the anti-mSR-BI495–112 antibody and biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG, visualized by immunoperoxidase staining, and counterstained with Harris modified hematoxylin, as described previously (9).

Statistical Analysis

Data are shown as the means ± S.D. Statistically significant differences were determined by either pairwise comparisons of values using the unpaired t test, with (if variances differed significantly) or without Welch's correction, or by one-way analysis of variance followed by the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison post-test when comparing three or more sets of data. Mean values for experimental groups are considered statistically significantly different for p < 0.05 for both types of tests.

RESULTS

Effects of Single Amino Acid Mutation in the Carboxylate Binding Loop of the First PDZ Domain of PDZK1 (PDZ1) Determined by ITC

The first PDZ domain (PDZ1) of PDZK1 has been reported to be responsible for binding to the C terminus of SR-BI and thus the regulation of hepatic SR-BI protein expression and function (9, 23, 36). To better define the molecular basis of this interaction, we attempted to generate several mutations in the PDZ1 domain that might interfere with PDZ1/SR-BI binding.

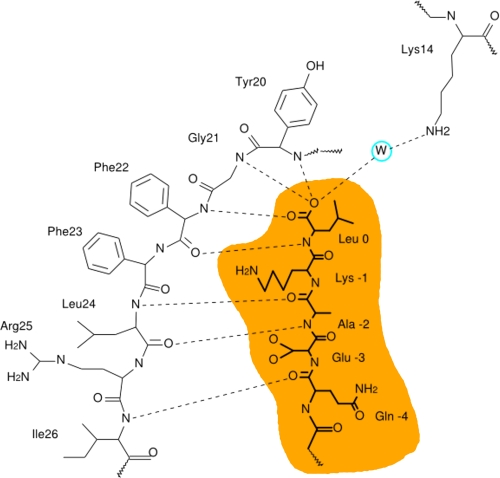

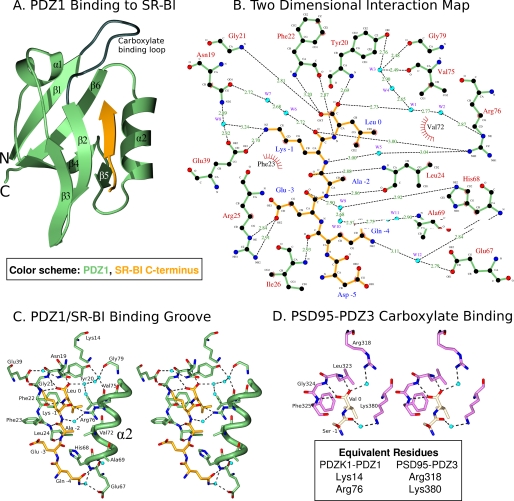

We focused our efforts on single amino acid substitutions within the carboxylate binding loop (CBL, Lys14-Xaa4-Asn19-Tyr-Gly-Phe-Phe-Leu24) of PDZ1, a region with several residues (especially the central hydrophobic-Gly-hydrophobic (Tyr20-Gly-Phe22) sequence) that are highly conserved in PDZ domains and directly interact via numerous hydrogen bonds with the C termini of target proteins (4). Fig. 1 shows a schematic diagram of putative hydrogen bonds between the PDZ1 CBL and the C terminus of SR-BI, Gln505-Glu-Ala-Lys-Leu509 (SR-BI numbering). In Fig. 1 and elsewhere, we will also use the alternative numbering scheme Gln −4-Glu-Ala-Lys-Leu0 (numbering from the C-terminal residue “0”), which is commonly used for PDZ domain target peptide sequences and will distinguish the target peptide residues from those of PDZK1. The hydrogen bonds (dashed lines) in Fig. 1 are based on structures of CBL-target peptide interactions of other PDZ domains, especially that of the third PDZ domain of the protein PSD95 (PSD95-PDZ3) (2). Based on that structure, we expected the following interactions: the three backbone amino groups of Tyr20-Gly-Phe22 hydrogen bonding to the target peptide C-terminal (Leu0) carboxyl group; the carbonyl group of Phe22 and amide nitrogen of Leu24 hydrogen bonding to the target peptide amide nitrogen of Leu0 and carbonyl oxygen of Ala−2; and the amino group of Ile26 hydrogen bonding to the carboxyl group of Gln−4, interactions that would extend the β-sheet-like structure of the PDZ domain (2). The positively charged side chain of Lys14 (equivalent to Arg318 of PSD95) was presumed to stabilize the negative charge of the C-terminal carboxyl group of the target via an indirect interaction through a bound water molecule (2).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the predicted interactions between the C terminus of SR-BI and the CBL of the first PDZ domain (PDZ1) of PDZK1. The predicted hydrogen bonding interactions (dashed lines) between the CBL of PDZ1 and the C-terminal pentapeptide from SR-BI (−4QEAKL0, shaded orange) are based on the structure of the third PDZ domain of PSD-95 and its bound target peptide (2). A water (W) is expected to mediate at least partial neutralization of the negative charge of the carboxylate of Leu0 of the target peptide by the positive side chain of Lys14 in the CBL.

To explore the potential significance of these putative interactions, we generated cDNA expression vectors encoding maltose-binding protein or GST fusion proteins incorporating wild-type (WT) PDZ1 and four PDZ1 mutants with the following single amino acid substitutions: K14A, Y20A, G21Y, and F22A. These constructs were used to express the corresponding fusion proteins in E. coli, which were partially purified, cleaved to release the maltose-binding protein or GST, and then purified to homogeneity as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The recombinant proteins analyzed include residues 7–116 of PDZK1, including the first PDZ domain of PDZK1 (residues 7–86) and 31 residues (87–116) from the 47 residue segment that lies between the PDZ1 and PDZ2 domains (interdomain segment), as well as a glycine residue at the N terminus.

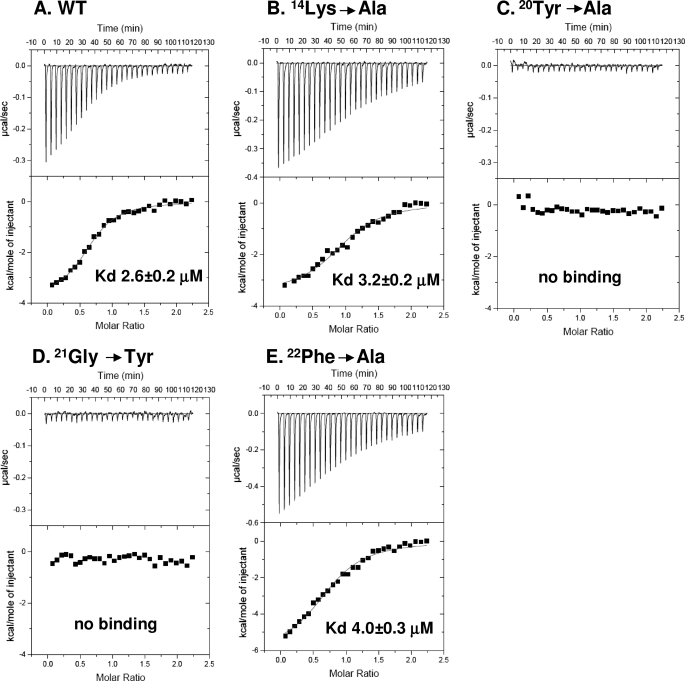

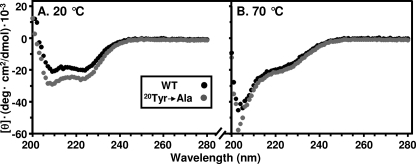

We used ITC at 20 °C to measure the binding of a peptide corresponding to the seven C-terminal residues of SR-BI (503VLQEAKL509) to these recombinant wild-type and mutant PDZ1 domains. Fig. 2A shows that WT PDZ1 bound to the peptide with high affinity (Kd, 2.6 ± 0.2 μm) in the range typically observed for high affinity PDZ domains binding to peptides, including their target sequences (37–39). Somewhat unexpectedly, the alanine mutations at the highly conserved K14A and F22A did not markedly alter peptide binding (Kd of 3.2 ± 0.2 and 4.0 ± 0.3 μm respectively, see Fig. 2, B and E) (further discussed below). In contrast, the Y20A and G21Y mutations abrogated all binding detectable with this highly sensitive technique (Fig. 2, C and D). To determine whether the loss of target peptide binding by the Y20A mutation was a consequence of unfolding of the domain, we compared the CD spectra of the WT and Y20A recombinant proteins at the temperature used for the ITC binding assay, 20 °C. Fig. 3 shows that their CD spectra, which are particularly sensitive to changes in α-helical content, were very similar at 20 °C (Fig. 3A), exhibiting the characteristics of a folded protein with α-helices. Their spectra were also similar at 70 °C (Fig. 3B) and markedly differed from those at 20 °C, as is expected after thermal denaturation. Thus, the loss of target peptide binding due to the Y20A mutation does not appear to be due to gross global loss of secondary structural elements. To better understand these mutagenesis results, we determined the high resolution (1.80 Å) crystal structure of a chimeric molecule containing the WT PDZ1 of PDZK1 and the five C-terminal residues of SR-BI (505QEAKL509).

FIGURE 2.

ITC analysis of the binding of a C-terminal peptide from SR-BI to recombinant WT and mutant PDZ1 domains. The indicated WT (A) or mutant (B–E) PDZ1 domains (0.01–0.03 mm in 1.8 ml of 150 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, 25 mm Tris, pH 8.0) were placed in a titration cell and equilibrated at 20 °C. A solution containing a seven-residue peptide from the C terminus of SR-BI-503VLQEAKL509 (0.18 to 0.6 mm) was added in 10-μl injections with an interval of 4 min between each injection to permit re-equilibration. Titration curves were analyzed and Kd values determined using ORIGIN 5.0 software.

FIGURE 3.

CD spectra of WT PDZ1 and Y20A PDZ1 mutant. Purified recombinant WT PDZ1 (black) and the Y20A PDZ1 mutant (gray) proteins (40 μm in PBS containing 1 mm DTT, pH 7.4) were subjected to CD spectroscopy at 20 °C (A) and subsequently heated to 70 °C and re-analyzed (B) as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

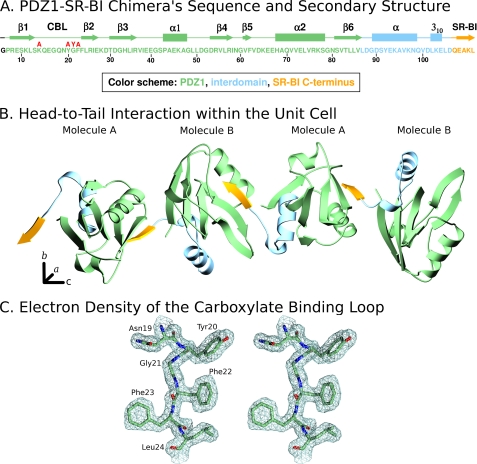

Crystal Structure of the PDZ1 Domain of PDZK1 Bound to the C Terminus of SR-BI

We generated a chimeric recombinant protein (sequence in Fig. 4A) for structure analysis. This protein includes an N-terminal glycine (encoded by the cloning vector, black in Fig. 4A), residues 7–106 of PDZK1, including the first PDZ domain of PDZK1 (residues 7–86, green) and 20 residues (87–106, blue) from the 47-residue segment that lies between the PDZ1 and PDZ2 domains (interdomain) whose C terminus was extended by addition of the five C-terminal residues of its target peptide on SR-BI (yellow): 505QEAKL509 (SR-BI numbering, alternatively −4QEAKL0). We grew crystals, collected x-ray diffraction data at the NSLS (Brookhaven National Laboratory), and solved the crystal structure at 1.80 Å resolution (Table 1) by molecular replacement using the NMR structure of the first PDZ domain of PDZK1 as the search model. Our strategy was based on that previously reported for the structural analysis of human Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor PDZ1 bound to the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (40), the β2-adrenergic and platelet-derived growth factor receptors (41). The high quality of the electron density map (Fig. 4C) permitted unequivocal assignment of all amino acid side chains. Fig. 4B shows that in the crystal the SR-BI peptide (yellow) of one molecule interacts with the peptide binding pocket of the PDZ domain (green) of an adjacent molecule (two molecules, designated A and B, per asymmetric unit), resulting in an “infinite chain” of head-to-tail molecules that runs parallel to the crystallographic c-axis. The interdomain sequence is shown in blue in Fig. 4B. Molecules A and B in the asymmetric unit have similar structures and superimpose with a root-mean-square deviation of 0.29 Å over all main chain atoms between Pro7 and Leu111. Molecule B was judged to have a superior quality electron density and will therefore be used to describe the structure below. For clarity, we numbered the residues in the PDZ1 portion of the structure to correspond to the numbering of this domain in the intact murine PDZK1 sequence. Fig. 5A shows the PDZ1 domain (residues 7–86 shown in green with the CBL highlighted in gray; the N- and C-terminal extensions have been removed for clarity) and the bound SR-BI peptide (yellow) from an adjacent molecule. The tertiary structure of PDZ1 matches that described previously for many PDZ domains, a compact globular structure containing a six-stranded antiparallel β-barrel (β1–β6) flanked by two α-helices (α1 and α2) (2, 42). An additional α-helix and a 310-helix are found in the portion of the interdomain sequence included in the structure (Fig. 4, A and B, and not shown in Fig. 5). To facilitate the description of the structure, we will designate the secondary structural elements (e.g. β1, α2, and CBL) in parentheses following residues that are in those elements (e.g. Gly21 (CBL)). As has been described for target peptide binding to other PDZ domains (2, 37, 41), the target peptide from the C terminus of SR-BI (−4QEAKL0) binds in a groove between the β2-strand and α2-helix, interacting with them and the CBL formed by Lys14-Xaa5-Tyr20-Gly21-Phe22-Phe23-Leu24 that connects β1- and β2-strands. The backbone amides and carbonyls of the target peptide form classic anti-parallel β-sheet hydrogen bonding interactions with Phe22 (CBL) to Ile26 (β2) (Fig. 5, A and B).

FIGURE 4.

X-ray crystal structure of a PDZ1-SR-BI chimera. A, amino acid sequence of the recombinant chimeric protein used for crystallization as follows: N-terminal glycine (black), PDZ1 (residues 7–86 (PDZK1 numbering), green), partial interdomain segment (87–106, lies between the PDZ1 and PDZ2 domains, blue), and five C-terminal residues of SR-BI (505QEAKL509, SR-BI numbering, yellow), The positions of the regions of secondary structure (β strands, α-, and 310-helices) and the CBL are indicated above the sequence, as are the single amino acid substitutions examined in this study (red). B, unit cell representation showing the head-to-tail arrangement of PDZ1-SR-BI chimeric molecules. This figure was generated using MOLSCRIPT (47) using the color scheme in A. C, stereo view of the electron density map (contoured at 2.5σ) and associated molecular model of a portion of the CBL (residues 19–24) at 1.80 Å resolution.

FIGURE 5.

Structure of the C terminus of SR-BI binding to the PDZ1 domain of PDZK1. A, ribbon diagram showing the three-dimensional structure of PDZ1 (residues 7–86, green with gray carboxylate binding loop) and the bound C terminus of SR-BI (−4QEAKL0) from an adjacent molecule. The six β-strands (β1–β6), two α-helices (α1–α2), and carboxylate binding loop (dark gray) are indicated. SR-BI C terminus (yellow) is bound in a groove between the β2-strand and α2-helix. The N-terminal glycine and interdomain residues (see Fig. 4) are not shown. B, two-dimensional representation of interactions between PDZ1 (green) and C terminus of SR-BI (yellow). Water molecules (W1, W2, etc.) are shown as cyan spheres. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines and hydrophobic interactions as arcs with radial spokes. This figure was generated using LIGPLOT (48). C, stereo representation of the ligand-binding groove of PDZ1 (green) and the bound C terminus of SR-BI (yellow). Oxygen atoms, nitrogen atoms, and waters are shown in red, dark blue, and cyan, respectively. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines. The orientation is similar to that in A. D, stereo representation of a portion of the ligand-binding groove of the third PDZ domain of PSD95 (PSD95-PDZ3, violet) and the two C-terminal residues of its bound ligand (Ser−1-Val0, beige) (2). Oxygen atoms, nitrogen atoms, and waters are shown in red, blue, and cyan, respectively. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines. The orientation is similar to that in C, and the residues in equivalent positions to Lys14 and Arg76 in PDZK1 are indicated.

There is a well defined, extensive hydrogen bonding network directly and indirectly connecting the target peptide, multiple regions of PDZ1, and bound water molecules (dashed lines in Fig. 5, B and C). The carboxylate group of Leu0 of the target peptide makes hydrogen bonds with the amide nitrogens of Tyr20, Gly21, and Phe22 and, through water (W1–4)-mediated interactions, the carbonyl oxygens of Val75 (α2) and Gly79, and the side chain of Arg76 (α2). It is noteworthy that the water-mediated interaction of the side chain of Lys14 with the carboxylate of the target peptide that was predicted based on the structure of PSD95 (Fig. 1) is not observed in the present structure (see additional discussion below). In addition, the hydroxyl group of Tyr20 (CBL) also forms water-mediated hydrogen bonds with the carbonyl oxygens of Val75 (α2), Arg76 (α2) and Gly79 (α2), interconnecting multiple segments of PDZ1 (Fig. 5, B and C). The amide nitrogen of Leu0 makes a hydrogen bond to the carbonyl oxygen of Phe22 (CBL). The isobutyl side chain of Leu0 fits into a deep hydrophobic pocket composed of the side chains of Phe22 (CBL), Leu24 (CBL), Val72 (α2), Val75 (α2), and Arg76 (α2) (Fig. 5, B and C)). The Nζ of Lys−1 of the target peptide makes a direct hydrogen bond to the side chain of Glu39 and hydrogen bonds via a water (W8) to the side chains of both Glu39 and Asn19 (CBL) (Fig. 5, B and C). There are also hydrogen bonds between the nitrogen and the carboxyl group of Ala−2 of the target peptide and the carboxyl group and the amide nitrogen of Leu24 (CBL), respectively. The backbone of Lys−1 also makes several direct and water-mediated interactions with Arg76 (α2) (Fig. 5, B and C). There is a hydrophobic interaction between the Cβ of Ala−2 and the isopropyl side chain of Val72 (α2). The side chain of Glu−3 makes a hydrogen bond to Nϵ of Arg25 (β2) (Fig. 5C). The side chain of Gln− 4 makes water-mediated hydrogen bonds to the side chain of Glu67 and the amides of His68 and Ala69 at the beginning of the α2-helix (Fig. 5, B and C).

The structure provides insight into the results of the ITC peptide binding studies. We were initially surprised that the Lys14 (CBL) to Ala mutation had essentially no effect on peptide binding because this position is highly conserved as a Lys or Arg in PDZ domains. Also, the high resolution crystal structures of several PDZ domain/target peptides (e.g. structures of PDZ domains with target peptides from PSD95 (PDZ3), Erbin, and PTP-1E (Protein Data Bank code 3LNY) (2, 37)) have suggested that the positive side chain at this position would, via one or two intermediate water molecules, participate in stabilization of the buried negative charge of the C-terminal carboxylate group of the target peptide. Indeed, mutagenesis analysis of Erbin by Skelton et al. (43) suggests that the equivalent Lys1287 (CBL) in Erbin significantly contributes to target peptide binding. The structure of the PDZ1-SR-BI peptide interaction suggests an attractive explanation of the essentially normal binding for the K14A mutant (Fig. 2B). Although Lys14 in PDZ1 does not appear to play a role in charge neutralization of the carboxylate of the target peptide (no interaction observed), the Nϵ of Arg76 (α2) indirectly interacts with the target carboxylate via two waters: carboxylate-W1-W2-Nϵ of Arg76 (α2) (Fig. 5, B and C). It is noteworthy that the positively charged side chains of the residues in the equivalent position to Arg76 (α2) in three close homologues of PDZ1 (PSD95 (PDZ3), Erbin, and PTP-1E) do not directly or indirectly (via water) interact with the carboxylate groups of their target peptides (Fig. 5D). However, they all exhibit water-mediated interactions of the carboxylate with the Lys14 (CBL) equivalent positive side chains (e.g. Fig. 5D). Furthermore, in all four structures, there is a water molecule in a position essentially identical to that of W1 in PDZ1 (Fig. 5, B–D) that hydrogen bonds to the target peptide carboxylate and, directly or through an additional water, hydrogen bonds to a positive side chain of residues at positions equivalent to either Lys14 (CBL) or Arg76 (α2). It is noteworthy that the PDZ domain in Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor uses the combination of these interactions with the carboxylate of its target peptide (water-mediated interactions with both the Lys14 (CBL) or Arg76 (α2) equivalents (44)). It seems likely that PDZ domains with very similar structures use slight variations on a theme as follows: water-mediated charge stabilization of the negative carboxylate of the target peptide to facilitate high affinity peptide binding. It seems likely that in PDZ1 of PDZK1, the positively charged side chain of Arg76 (α2) together with the H-bonding for the carbonyls of Gly21 and Phe22 may be sufficient to stabilize the negative C-terminal carboxylate of the target peptide in the context of the Lys14 to alanine (K14A) mutation, thus accounting for the essentially normal Kd value for target peptide binding to this mutant (Fig. 2).

The structure of PDZ1 also suggests that the F22A mutation would be unlikely to interfere with the direct bonds between the nitrogen and carbonyl groups of the residue in position 22 and the carboxylate and nitrogen groups of the target peptide Leu0. Furthermore, compared with the hydrophobic side chains of Leu24 (CBL), Val72 (α2), and Val75 (α2), the side chain of Phe22 (CBL) appears to make a significantly smaller contribution to the hydrophobic pocket into which the side chain of the target peptide Leu0 binds (Fig. 5, B and C). Thus, the F22A mutation also does not alter peptide binding substantially (Fig. 2).

The small side chain of Gly21 (CBL), the most highly conserved residue in the CBLs of PDZ domains, appears to be essential for the proper orientation of the CBL backbone and its interactions with the target peptide. The G21Y mutation would be expected to force the backbone into a conformation incompatible with high affinity peptide binding, including disruptions of the interactions that stabilize the C terminus of the peptide. Molecular modeling of the G21Y mutation based on wild-type PDZ1 structure was performed using the RosettaBackrub server (45). Ten models were generated and analyzed. The results show that the G21Y mutation would lead to substantial loss in the affinity of PDZ1 for the SR-BI peptide due to a change in the orientation of the CBL loop, which in the mutant is predicted to move closer to the carboxylate group of Leu0, forcing the amino acid out of the hydrophobic pocket.

Finally, the structure helps explain the virtually complete loss of target peptide binding by the Y20A mutation. The side chain of Tyr20 (CBL) appears essential for several reasons. The hydroxyl group forms water (W3)-mediated hydrogen bonds with the backbones of Gly79 and Val75 (α2) and is also involved in an elaborate network of water-mediated hydrogen bonding linking to the Nϵ of Arg76 (α2) and the carboxylate of Leu0 (Fig. 5, B and C). The phenol ring also makes a hydrophobic interaction with the side chain of 14Lys (CBL) and makes a contribution to the hydrophobic binding pocket that binds the side chain of Leu0. These interactions would be significantly disrupted by the Y20A mutation.

Effects of the Mutated PDZK1 Transgenes on Hepatic SR-BI Expression and Lipoprotein Metabolism in Vivo

We incorporated two of the PDZ1 single amino acid substitutions, K14A (essentially normal target peptide binding, PDZK1(K14A)) and Y20A (no binding, PDZK1(Y20A)), into full-length PDZK1 expression constructs and used them to generate transgenic mice with liver-specific expression in FVB mice. Two founder lines for PDZK1(K14A) (952 and 954) and three founder lines for PDZK1(Y20A) (694–696) were generated and used to generate matched wild-type (WT-Tg) and PDZK1 KO (KO-Tg) transgenic mice on a mixed FVB/129SvEv background. Background-matched nontransgenic WT and PDZK1 KO mice were used as controls for each founder.

Hepatic expression levels of PDZK1 and SR-BI proteins in nontransgenic and transgenic mice were determined by quantitative immunoblotting in which ϵ-COP was used as a loading control (e.g. Figs. 6A and 7A), and the ratios of band intensities (transgenic/nontransgenic) are shown in Table 2. The steady-state levels of PDZK1 transgene-encoded proteins (WT-Tg/WT) varied between 6.8 ± 1.6- and 20.8 ± 8.3-fold greater than that of endogenous PDZK1 in nontransgenic WT mice. Thus, for all experiments described below, there was substantial overexpression of the transgene-encoded PDKZ1 proteins relative to that of the endogenous PDZK1 protein in nontransgenic WT mice.

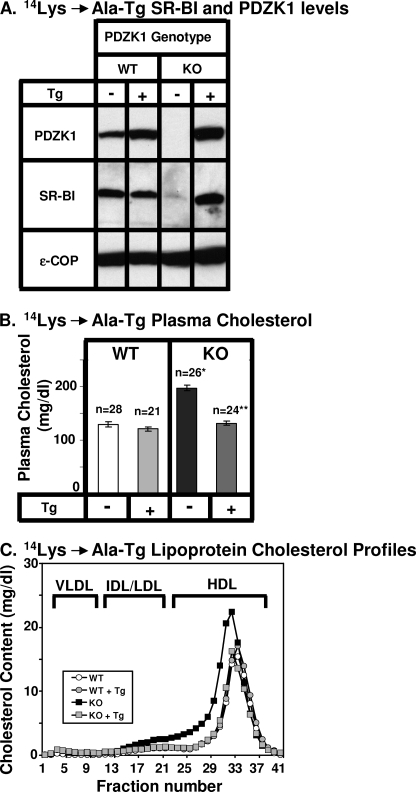

FIGURE 6.

Effects of expression of the PDZK1(K14A) transgene on hepatic SR-BI protein levels (A) and plasma lipoprotein cholesterol (B and C) in WT and PDZK1 KO mice. A, liver lysates (∼30 μg of protein) from mice with the indicated genotypes, with (+) or without (−) the PDZK1(K14A) Tg, were analyzed by immunoblotting, and bands representing PDZK1 (∼70 kDa) and SR-BI (∼82 kDa) were visualized by chemiluminescence. ϵ-COP (∼34 kDa) was used as a loading control. Note the faint SR-BI band in the nontransgenic PDZK1 KO lane. Replicate experiments with multiple exposures and sample loadings were used to determine the relative levels of expression of SR-BI. All bands in adjacent panels were from a single gel. WT and WT (K14A-Tg) data were all from a single gel but reordered for clarity of presentation. B, plasma samples were harvested from mice with the indicated genotypes and PDZK1(K14A) transgene. Total plasma cholesterol levels were determined in individual samples by enzymatic assay, and mean values from the indicated numbers of animals (n) are shown for each genotype. Independent WT and KO control animals for each founder line were generated to ensure that the mixed genetic backgrounds for experimental and control mice were matched. * indicates the nontransgenic KO plasma cholesterol levels were statistically significantly different from those plasma cholesterol levels of WT (p < 0.0001). ** indicates PDZK1 KO (K14A-Tg) plasma cholesterol levels were statistically significantly different from those plasma cholesterol levels of nontransgenic PDZK1 KO mice (p < 0.0001). WT, WT (K14A-Tg), and KO (K14A-Tg) plasma cholesterol levels were not statistically significantly different. C, plasma samples (described in B) from individual animals were size-fractionated by FPLC, and the total cholesterol content of each fraction was determined by an enzymatic assay. The chromatograms are representative of multiple individually determined profiles. Approximate elution positions of native VLDL, IDL/LDL, and HDL particles are indicated by brackets and were determined as described previously (15).

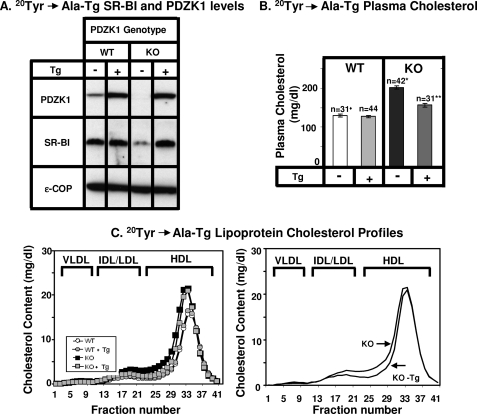

FIGURE 7.

Effects of expression of the PDZK1(Y20A) transgene on hepatic SR-BI protein levels (A) and plasma lipoprotein cholesterol (B and C) in WT and PDZK1 KO mice. A, liver lysates (∼30 μg of protein) from mice with the indicated genotypes, with (+) or without (−) the PDZK1(Y20A) Tg, were analyzed by immunoblotting, and bands representing PDZK1 (∼70 kDa) and SR-BI (∼82 kDa) were visualized by chemiluminescence. ϵ-COP (∼34 kDa) was used as a loading control. Note the faint SR-BI band in the nontransgenic PDZK1 KO lane. Replicate experiments with multiple exposures and sample loadings were used to determine the relative levels of expression of SR-BI. All bands in adjacent panels were from a single gel. WT and WT (Y20A-Tg) data were all from a single gel but reordered for clarity of presentation. B, plasma samples were harvested from mice with the indicated genotypes and PDZK1(Y20A) transgene. Total plasma cholesterol levels were determined in individual samples by enzymatic assay, and mean values from the indicated numbers of animals (n) are shown for each genotype. Independent WT and KO control animals for each founder line were generated to ensure that the mixed genetic backgrounds for experimental and control mice were matched. * indicates the nontransgenic PDZK1 KO plasma cholesterol levels were statistically significantly different from those plasma cholesterol levels of WT (p < 0.0001). ** indicates PDZK1 KO (Y20A-Tg) plasma cholesterol levels were statistically significantly different from those plasma cholesterol levels of nontransgenic PDZK1 WT and KO mice (p < 0.0001). WT and WT(Y20A-Tg) plasma cholesterol levels were not statistically significantly different. C, plasma samples (described in B) from individual animals were size-fractionated by FPLC, and the total cholesterol content of each fraction was determined by an enzymatic assay. The chromatograms are representative of multiple individually determined profiles. Approximate elution positions of native VLDL, IDL/LDL, and HDL particles are indicated by brackets and were determined as described previously (15).

TABLE 2.

Quantitation of PDZK1 and SR-BI expression in transgenic mice expressing PDZK1 mutants

| Mutant | Founder | PDZK1, WT-Tg/WT | SRBI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT-Tg/WT | KO-Tg/WT | |||

| K14A | 952 | 6.78 ± 1.61a | 1.04 ± 0.42b | 1.59 ± 0.22b |

| 954 | 12.24 ± 0.71a | |||

| Y20A | 694 | 10.21 ± 0.09a | 1.36 ± 0.13b | 0.87 ± 0.12b |

| 695 | 20.76 ± 8.31a | |||

| 696 | 11.69 ± 1.40a | |||

a p < 0.05 between WT-Tg and WT.

b p > 0.05 between WT-Tg or KO-Tg and WT.

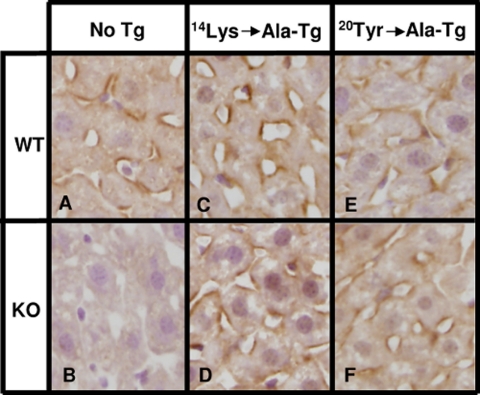

In transgenic WT mice relative to nontransgenic WT mice, expression of the mutant PDZK1 proteins had virtually no influence on the levels of hepatic SR-BI protein expression determined by immunoblotting (Figs. 6A and 7A and Table 2) nor did the transgenes alter sinusoidal membrane-associated distribution of SR-BI determined by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 8, A, C, and E), plasma cholesterol levels (left panels in Figs. 6B and 7B), and lipoprotein cholesterol size distribution profiles determined by FPLC (circles in Figs. 6C and 7C)). In particular, the mutated transgene did not produce a dominant negative effect when expressed in WT mice, such as that observed with overexpression of a transgene encoding only the WT PDZ1 domain (27).

FIGURE 8.

Immunohistochemical analysis of hepatic SR-BI in WT and PDZK1 KO nontransgenic (A and B), PDZK1(K14A) transgenic (C and D), and PDZK1(Y20A) transgenic (E and F) mice. Livers from mice of the indicated genotypes and Tg were fixed, frozen, and sectioned. The sections were then stained with a polyclonal anti-SR-BI antibody and a biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody and visualized by immunoperoxidase staining. Magnification, ×600.

As described previously (9, 26, 27, 46), absence of PDKZ1 expression in nontransgenic PDZK1 KO mice resulted in a dramatic loss of hepatic SR-BI protein (Figs. 6A, 7A, and 8B), increased plasma total cholesterol (black bars in Figs. 6B and 7B), and an increase in the size of HDL particles (leftward shift in lipoprotein profiles, Figs. 6C and 7C, black squares). These abnormalities are corrected by hepatic expression of a wild-type PDZK1 transgene (27). Hepatic transgenic expression of the PDZK1(K14A) mutant in PDZK1 KO mice corrected all of these abnormalities (Figs. 6 and 8D and Table 2), as one might expect from the ability of the PDZ1(K14A) domain to bind the SR-BI C-terminal target peptide essentially normally in vitro (Fig. 2B).

The effects on PDZK1 KO mice of the PDZK1(Y20A) transgene were unexpected. We assumed that PDZK1(Y20A) would not be able to complement any of the abnormalities in PDZK1 KO mice because the mutant Y20A PDZ1 domain cannot bind the C terminus of SR-BI (Fig. 2C). This was not the case. Hepatic transgenic overexpression (∼10–20-fold) of the mutant encoding PDZK1(Y20A) in PDZK1 KO mice restored essentially normal levels of hepatic SR-BI protein (Fig. 7A and Table 2), a substantial amount that was expressed on the surfaces of the hepatocytes (Fig. 8F). This was associated with a partial correction of the plasma cholesterol level (Fig. 7B, right, dark gray bar) from 200.9 ± 3.8 mg/dl in PDZK1 KO mice to 156.3 ± 4.6 mg/dl in PDZK1(Y20A) expressing transgenic PDZK1 KO mice (p < 0.0001); the WT control value was (130.5 ± 4.0 mg/dl). There was a modest, but reproducible, reduction in the amounts of larger lipoproteins in the plasma (Fig. 7C). Thus, the Y20A mutation that prevents the binding of PDZ1 to the C terminus of SR-BI only partially disrupts function of PDZK1 in vivo.

DISCUSSION

PDZK1 is a four PDZ domain containing the tissue-specific adaptor of the HDL receptor SR-BI (9, 23, 36) and is necessary to maintain normal steady state, cell-surface expression, and function of SR-BI at the sinusoidal membrane of hepatocytes in vivo, and consequently normal plasma cholesterol concentration and lipoprotein size distribution as determined by FPLC (9). Absence of PDZK1 in PDZK1 KO mice dramatically reduces hepatic levels of SR-BI protein and, similar to the case of SR-BI KO mice, results in increased plasma cholesterol and an altered lipoprotein distribution with abnormally large HDL particles (9, 15). Because of their important roles in lipoprotein metabolism, SR-BI and PDZK1 are atheroprotective (17, 19, 20, 24, 25). The only direct interaction between these two molecules responsible for the influence of PDZK1 on SR-BI has been assumed to be via the binding of the cytoplasmic C-terminal tail of SR-BI (target peptide) to the first PDZ domain of PDZK1 (PDZ1) (23, 36). As expected, hepatic overexpression of the PDZ1 domain alone produces a dominant negative phenotype (26). Studies in which PDZK1 transgenes with nested C-terminal deletions were expressed in the livers of PDZK1 KO mice have shown that all four PDZ domains of PDZK1 are necessary to restore normal expression, localization, and function of SR-BI in these mice (26). However, the precise functions of the second, third, and fourth PDZ domains of PDZK1 are unclear.

Using ITC, we have demonstrated that a seven residue peptide with the sequence of the C terminus of SR-BI binds with high affinity (Kd = 2.6 μm) to a recombinant, purified wild-type PDZ1 domain of PDZK1. We also prepared four mutant PDZ1 domains with individual amino acid substitutions at one of four conserved residues in the carboxylate binding loop as follows: K14A, Y20A, G21Y, or F22A. The Y20A and G21Y substitutions completely blocked binding of the SR-BI target peptide, whereas the K14A and F22A substitutions had very little influence on the binding (Fig. 2).

To understand the structural bases of these results, we determined the high resolution crystal structure of a chimeric recombinant protein including residues 7–106 of wild-type PDZK1 (residues 7–86 compose PDZ1) whose C terminus was extended by addition of the five C-terminal residues of its target peptide on SR-BI, 505QEAKL509. In the crystals, the SR-BI target peptide from one molecule binds in the peptide binding pocket of the PDZ1 portion of an adjacent molecule, resulting in an infinite chain of head-to-tail molecules. The overall fold of the PDZ1 domain and many of the interactions between the PDZ1 domain and its target peptide were similar to those reported previously for a variety of PDZ domains (2, 37, 41), with the PDZ1 carboxylate binding loop playing a critical role in binding the target peptide.

Analysis of the structure suggested that the K14A substitution did not dramatically influence binding because an alternative positively charged side chain (Arg76) would be able to stabilize the binding of the negatively charged carboxylate of the C-terminal Leu (Leu0) on the target peptide. The structure also indicated that the F22A substitution was unlikely to substantially alter either the conformation of the portions of PDZ1 that hydrogen bond to the target peptide or the characteristics of the hydrophobic pocket into which the aliphatic side chain of the target peptide 0Leu binds. This may be because the hydrophobic side chains of other residues that line the pocket can compensate for the substitution of the Phe22 side chain by the methyl group of Ala. In contrast, the G21Y substitution is predicted to dramatically alter the conformation of the carboxylate binding loop, in part because the bulky aromatic side chain of Tyr cannot be accommodated in the structure without forcing the backbone of the carboxylate binding loop to move relative to the rest of the protein and the target peptide-binding site, and thus prevent target peptide binding to this critical region. The G21Y substitution might also reduce the flexibility of the carboxylate binding loop, and flexibility in this loop due to the presence of Gly21 has been proposed to contribute to the ability of PDZ domains to bind their target peptides (2). Similarly, the structure suggests that the Y20A substitution may abrogate target peptide binding because the side chain of Tyr20 appears to help orient the CBL backbone for optimal target peptide binding. Indeed, the amino group of Tyr20 and the adjacent amino group of Gly21 directly hydrogen bond to the target peptide (Figs. 1 and 5).

The identification of a single amino acid substitution, Y20A, in PDZ1 that abrogates binding to the C terminus of SR-BI yet does not dramatically alter the conformation of the domain as assessed by circular dichroism opened the possibility of directly assessing the significance of this binding interaction in vivo. We incorporated the Tyr20 to Ala substitution (PDZK1(Y20A)), as well as a control K14A substitution (essentially normal target peptide binding, PDZK1(K14A)) into full-length PDZK1 expression constructs, and we used them to generate transgenic WT and PDZK1 KO mice with liver-specific transgene expression and control nontransgenic mice. As expected (27), in WT mice, the transgenes did not interfere with endogenous hepatic SR-BI protein expression (amounts, localization to sinusoidal plasma membrane) nor with lipoprotein metabolism, as assessed by total plasma cholesterol measurements and determination of lipoprotein size distributions by FPLC. Also as expected, hepatic transgenic expression in PDZK1 KO mice of the PDZK1(K14A) protein (substitution does not alter target peptide binding to PDZ1) was able to restore essentially normal hepatic SR-BI protein expression and lipoprotein metabolism (WT plasma cholesterol levels and WT-like lipoprotein size distribution).

We expected that transgenic expression of PDZK1(Y20A) would not be able to correct in PDZK1 KO mice their striking defects in hepatic SR-BI protein expression and lipoprotein metabolism, because earlier studies suggested that such a mutant adaptor protein would not be able to bind to hepatic SR-BI. Remarkably, PDZK1 KO mice expressing PDZK1(Y20A) protein (levels 10–20-fold higher than endogenous PDZK1 in WT mice) exhibited hepatic SR-BI protein expression not significantly different from WT control mice (Fig. 7), a substantial amount of which was expressed on the surfaces of the hepatocytes (Fig. 8), and a significant and substantial, but not complete, restoration of normal lipoprotein metabolism (Fig. 7). There appear to be two possible explanations for these unexpected observations. First, the mutated PDZ1 domain of PDZK1(Y20A) might have retained some SR-BI binding activity and that residual activity combined with the in vivo overexpression of PDZK1(Y20A) may have been sufficient to partially complement the PDZK1 deficiency in the KO mice. We find this explanation unlikely, given our inability to detect any binding in vitro using the highly sensitive ITC method. Second, there may be an additional site(s) in PDZK1 other than PDZ1 (e.g. other PDZ domains or the C-terminal portion of the protein) that can bind to SR-BI and mediate the SR-BI-PDZK1 interaction required for hepatic SR-BI protein expression and consequent control of lipoprotein metabolism. Such an alternative site might exhibit a lower affinity for binding SR-BI than that of wild-type PDZ1 because overexpression of PDZK1(Y20A) did not completely correct the lipoprotein metabolism abnormalities in the PDKZ1 KO mice. Additional studies will be required to determine whether such additional SR-BI-binding sites exist and the role they might play in the mechanism underlying PDZK1-dependent SR-BI expression and function in the liver.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joel Lawitts from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Transgenic Facility; Debby Pheasant from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Biophysical Instrumentation Facility for helping with the ITC experiments; Verna Frasca from Microcal for helping with the interpretation of the ITC data, and the National Synchrotron Light Source (Brookhaven National Laboratory, Long Island, NY).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL077780 (to O. K.) and HL52212 and HL66105 (to M. K.).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3NGH) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- SR-BI

- scavenger receptor class B type I

- KO

- knock-out

- CBL

- carboxylate binding loop

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- Tg

- transgene.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Ham M., Hendriks W. (2003) Mol. Biol. Rep. 30, 69–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doyle D. A., Lee A., Lewis J., Kim E., Sheng M., MacKinnon R. (1996) Cell 85, 1067–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tonikian R., Zhang Y., Sazinsky S. L., Currell B., Yeh J. H., Reva B., Held H. A., Appleton B. A., Evangelista M., Wu Y., Xin X., Chan A. C., Seshagiri S., Lasky L. A., Sander C., Boone C., Bader G. D., Sidhu S. S. (2008) PLoS Biol. 6, e239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pawson T., Scott J. D. (1997) Science 278, 2075–2080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kocher O., Comella N., Tognazzi K., Brown L. F. (1998) Lab. Invest. 78, 117–125 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seidler U., Singh A., Chen M., Cinar A., Bachmann O., Zheng W., Wang J., Yeruva S., Riederer B. (2009) Exp. Physiol. 94, 175–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yesilaltay A., Kocher O., Rigotti A., Krieger M. (2005) Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 16, 147–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kocher O., Krieger M. (2009) Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 20, 236–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kocher O., Yesilaltay A., Cirovic C., Pal R., Rigotti A., Krieger M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 52820–52825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rigotti A., Miettinen H. E., Krieger M. (2003) Endocr. Rev. 24, 357–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Assanasen C., Mineo C., Seetharam D., Yuhanna I. S., Marcel Y. L., Connelly M. A., Williams D. L., de la Llera-Moya M., Shaul P. W., Silver D. L. (2005) J. Clin. Invest. 115, 969–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimura T., Tomura H., Mogi C., Kuwabara A., Damirin A., Ishizuka T., Sekiguchi A., Ishiwara M., Im D. S., Sato K., Murakami M., Okajima F. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 37457–37467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seetharam D., Mineo C., Gormley A. K., Gibson L. L., Vongpatanasin W., Chambliss K. L., Hahner L. D., Cummings M. L., Kitchens R. L., Marcel Y. L., Rader D. J., Shaul P. W. (2006) Circ. Res. 98, 63–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu W., Saddar S., Seetharam D., Chambliss K. L., Longoria C., Silver D. L., Yuhanna I. S., Shaul P. W., Mineo C. (2008) Circ. Res. 102, 480–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rigotti A., Trigatti B. L., Penman M., Rayburn H., Herz J., Krieger M. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 12610–12615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yesilaltay A., Morales M. G., Amigo L., Zanlungo S., Rigotti A., Karackattu S. L., Donahee M. H., Kozarsky K. F., Krieger M. (2006) Endocrinology 147, 1577–1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun A., Trigatti B. L., Post M. J., Sato K., Simons M., Edelberg J. M., Rosenberg R. D., Schrenzel M., Krieger M. (2002) Circ. Res. 90, 270–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun A., Zhang S., Miettinen H. E., Ebrahim S., Holm T. M., Vasile E., Post M. J., Yoerger D. M., Picard M. H., Krieger J. L., Andrews N. C., Simons M., Krieger M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 7283–7288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trigatti B., Rayburn H., Viñals M., Braun A., Miettinen H., Penman M., Hertz M., Schrenzel M., Amigo L., Rigotti A., Krieger M. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 9322–9327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Eck M., Twisk J., Hoekstra M., Van Rij B. T., Van der Lans C. A., Bos I. S., Kruijt J. K., Kuipers F., Van Berkel T. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 23699–23705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dole V. S., Matuskova J., Vasile E., Yesilaltay A., Bergmeier W., Bernimoulin M., Wagner D. D., Krieger M. (2008) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 1111–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holm T. M., Braun A., Trigatti B. L., Brugnara C., Sakamoto M., Krieger M., Andrews N. C. (2002) Blood 99, 1817–1824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikemoto M., Arai H., Feng D., Tanaka K., Aoki J., Dohmae N., Takio K., Adachi H., Tsujimoto M., Inoue K. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6538–6543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kocher O., Yesilaltay A., Shen C. H., Zhang S., Daniels K., Pal R., Chen J., Krieger M. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1782, 310–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yesilaltay A., Daniels K., Pal R., Krieger M., Kocher O. (2009) PLoS ONE 4, e8103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fenske S. A., Yesilaltay A., Pal R., Daniels K., Barker C., Quiñones V., Rigotti A., Krieger M., Kocher O. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 5797–5806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fenske S. A., Yesilaltay A., Pal R., Daniels K., Rigotti A., Krieger M., Kocher O. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22097–22104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2007) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vagin A., Steiner R., Lebedev A., Potterton L., McNicholas S., Long F., Murshudov G. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2184–2195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kocher O., Pal R., Roberts M., Cirovic C., Gilchrist A. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 1175–1180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simonet W. S., Bucay N., Lauer S. J., Taylor J. M. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 8221–8229 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmiter R. D., Brinster R. L. (1986) Annu. Rev. Genet. 20, 465–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo Q., Penman M., Trigatti B. L., Krieger M. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 11191–11196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silver D. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34042–34047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birrane G., Chung J., Ladias J. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1399–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiedemann U., Boisguerin P., Leben R., Leitner D., Krause G., Moelling K., Volkmer-Engert R., Oschkinat H. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 343, 703–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen J. R., Chang B. H., Allen J. E., Stiffler M. A., MacBeath G. (2008) Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1041–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karthikeyan S., Leung T., Ladias J. A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19683–19686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karthikeyan S., Leung T., Ladias J. A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18973–18978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.von Ossowski I., Oksanen E., von Ossowski L., Cai C., Sundberg M., Goldman A., Keinänen K. (2006) FEBS J. 273, 5219–5229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skelton N. J., Koehler M. F., Zobel K., Wong W. L., Yeh S., Pisabarro M. T., Yin J. P., Lasky L. A., Sidhu S. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7645–7654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karthikeyan S., Leung T., Birrane G., Webster G., Ladias J. A. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 308, 963–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lyskov S., Gray J. J. (2008) Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W233–W238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yesilaltay A., Kocher O., Pal R., Leiva A., Quiñones V., Rigotti A., Krieger M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 28975–28980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kraulis P. (1991) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24, 946–950 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wallace A. C., Laskowski R. A., Thornton J. M. (1995) Protein Eng. 8, 127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]