Abstract

Genetically defined mouse models offer an important tool to identify critical secondary genetic alterations with relevance to human cancer pathogenesis. We used newly generated MMTV-Cre105Ayn mice to inactivate p53 and/or Rb strictly in the mammary epithelium and to determine recurrent genomic changes associated with deficiencies of these genes. p53 inactivation led to formation of estrogen receptor positive raloxifene-responsive mammary carcinomas with features of luminal subtype B. Rb deficiency was insufficient to initiate carcinogenesis but promoted genomic instability and growth rate of neoplasms associated with p53 inactivation. Genome-wide analysis of mammary carcinomas identified a recurrent amplification at chromosome band 9A1, a locus orthologous to human 11q22, which contains protooncogenes cIAP1 (Birc2), cIAP2 (Birc3) and Yap1. Interestingly, this amplicon was preferentially detected in carcinomas carrying wild-type Rb. However, all three genes were overexpressed in carcinomas with p53 and Rb inactivation, likely due to E2F-mediated transactivation, and cooperated in carcinogenesis according to gene knockdown experiments. These findings establish a model of luminal subtype B mammary carcinoma, identify critical role of cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap co-expression in mammary carcinogenesis and provide an explanation for the lack of recurrent amplifications of cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1 in some tumors with frequent Rb-deficiency, such as mammary carcinoma.

Keywords: breast cancer, genomic maintenance, mouse models of cancer, oncogenomics, tumor suppressor

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women in the US (Jemal et al., 2009). p53 and Rb and their pathways are frequently altered in breast cancer. p53 is a transcription factor that regulates genes critical for cell cycle, apoptosis, senescence, and DNA repair, thus preventing genomic instability (Meek, 2009, Riley et al., 2008). Mutation of p53 is the most common genetic abnormality found in human cancer, and occurs in 20-40% of sporadic breast carcinomas (Borresen-Dale, 2003). Furthermore, p53 is mutated in individuals with Li-Fraumeni syndrome, a heritable condition in which early-onset breast cancers are the most prevalent cancer types (Malkin, 1994). According to gene expression profiling, p53 mutations are most frequently associated with basal-like/estrogen receptor (ER) negative (82%), ERBB2/HER2 overexpressing/ER negative (71%) and luminal/ER positive subtype B (40%) breast cancers (Sorlie et al., 2001) all of which have poor prognosis (Hu et al., 2006, Sorlie et al., 2001, Sorlie et al., 2003).

Mice homozygous for the p53 null allele (p53−/−) develop lymphomas or sarcomas within first three months (Donehower et al., 1992, Jacks et al., 1994). Development of some mammary tumors has been observed in p53+/− mice, but only on the BALB/c background (Kuperwasser et al., 2000). With the development of Cre-loxP technology, spontaneous mammary carcinogenesis has been observed after inactivation of wild-type p53 by either its deletion (Lin et al., 2004, Liu et al., 2007) or expression of a dominant negative form carrying a p53.R270H point mutation (Wijnhoven et al., 2005). Unfortunately, the interpretation of experiments has been somewhat complicated by formation of lymphomas and/or other neoplasms due to expression of the Cre transgene in lymphocytes and other tissues.

Rb is essential for cell cycle control and exerts diverse effects on cell proliferation, survival and differentiation (Burkhart and Sage, 2008). More recently the role of Rb in control of genomic instability has been demonstrated in cell culture experiments and in a mouse model of liver neoplasia (Knudsen et al., 2006, Reed et al., 2009). The observation that Rb is inactivated in 20-35% of human breast cancers, suggests that it has an important role in the pathogenesis of these neoplasms (Bosco and Knudsen, 2007, Scambia et al., 2006). Additionally, other defects in Rb pathway components, such as Cyclin D1 overexpression, and p16INK4A loss are frequently observed in human breast cancer (Geradts and Wilson, 1996, Roy and Thompson, 2006). However, in serial transplantations of Rb mutant mammary anlagen no significant differences were found in outgrowth of Rb-deficient and wild-type epithelia (Robinson et al., 2001). At the same time, transgenic mice expressing cyclin D1 in the mammary gland, hence deprived of functional Rb family proteins (Rb, p107 and p130), develop mammary neoplasms (Wang et al., 1994). Accordingly, it has been reported that inactivation of the whole Rb family by T121m, a fragment of SV40 T antigen, also leads to mammary carcinogenesis (Simin et al., 2004).

In agreement with the potential cooperation between p53 and Rb inactivation, p53 deficiency results in acceleration of mammary carcinogenesis in the T121m model (Simin et al., 2004) as well as in transgenic mice expressing SV40 large T antigen (Li et al., 2000) which inactivates both p53 and all proteins of Rb family. However, it remains unclear if selective inactivation of Rb has any effect on cancer initiation or progression.

To ensure mammary epithelium-restricted Cre expression, we have established a new FVB/N MMTV-Cre transgenic mouse line (MMTV-Cre105Ayn) which does not express Cre in lymphocytes and other tissues. Using this line we demonstrate that conditional inactivation of p53 results in ER-positive mammary carcinomas which carry recurrent amplification of cellular inhibitor of apoptosis (cIAP)1, cIAP2 and Yap1. Rb inactivation alone is insufficient to initiate mammary carcinogenesis but promotes genetic instability and accelerates neoplastic growth. Interestingly, lack of Rb suppresses genomic amplification of cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1. However, expression levels of these genes remain elevated and their knockdown decreases tumorigenicity, thereby indicating critical importance of the cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1 in mammary carcinogenesis.

Results

Generation of MMTV-Cre transgenic mice

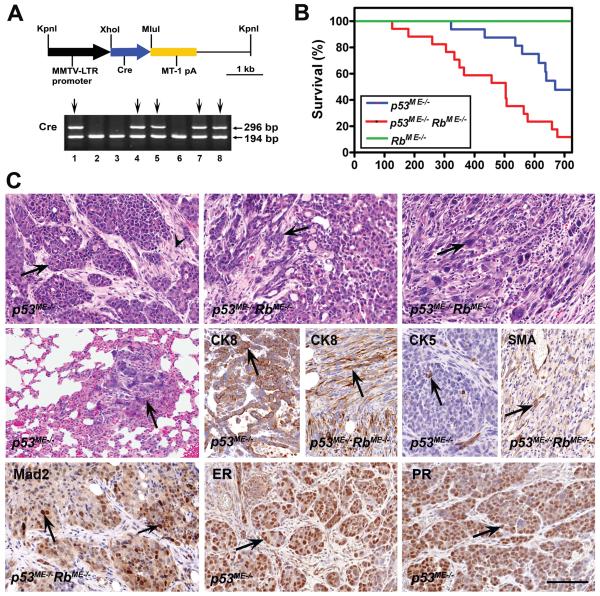

To avoid genetic background variations and frequent lymphomas due to Cre expression in lymphocytes and other tissues we generated mice expressing Cre under the control of MMTV-LTR (Fig. 1 A) and screened founders for exclusive expression of Cre in the mammary epithelium after their crosses with Gt(ROSA)26SorTM1sor reporter mice. One out of five tested lines, FVB/N Tg(MMTV-Cre)105Ayn expressed Cre selectively in the mammary epithelium (Suppl. Table 1 and Suppl. Fig. 1) Furthermore, no lymphomas or other non-mammary neoplasms were observed in crosses of this line with p53floxP/floxP mice. Therefore, it has been chosen for all subsequent experiments and will be described as MMTV-Cre.

Figure 1. Generation and characterization of a mouse model of mammary carcinoma associated with p53 and Rb deficiency.

A, Generation and characterization of MMTV-Cre transgenic mice. (Top) The MMTV-Cre transgene consists of the 1.48 kb MMTV-LTR promoter followed by the 1.1 kb Cre gene and the 1.2 kb MT-1 polyadenylation site. (Bottom) Identification of MMTV-Cre transgenic mice by PCR genotyping. 296 bp and 194 bp fragments are diagnostic for the Cre gene and mouse Rb gene, respectively. MMTV-Cre founder mice are identified in lanes 1, 4, 5, 7, and 8 (lines MMTV-Cre104Ayn, 105Ayn, 106Ayn, 107Ayn, 108Ayn, respectively). B, Survival of mice with mammary-specific inactivation of p53 (n=16, median 669 days), Rb alone (n=8, median 700 days) or p53 and Rb together (n=17, median 504 days). P for log-rank comparisons of survival curves of p53ME−/− and p53ME−/−RbME−/− mice is 0.0058. C, Neoplasms of the mammary epithelium in p53ME−/− and p53ME−/−RbME−/− mice. (Top) Mammary carcinomas with mainly (Left) solid pattern of growth (arrow) and dense fibrous stroma (arrowhead), (Middle) glandular pattern (arrow), (Right) spindle cell pattern with diverse cell types (arrow). H&E stain. (Middle) Lung metastasis of mammary carcinoma (arrow) (Left), H&E stain. Expression of CK8, CK5 and SMA in carcinoma cells (arrows) (Middle and Right). (Bottom) Expression of Mad2, ER and PR in carcinoma cells (arrows). ABC Elite method, hematoxylin counterstaining. Calibration bar for all images: 100 μm.

Inactivation of p53 in mammary epithelium leads to neoplastic lesions and Rb loss accelerates carcinogenesis

Conditional inactivation of p53 was sufficient for mammary carcinogenesis in our model. Eight out of 16 (50%) p53ME−/− mice (see Materials and Methods for abbreviations) and none out of eight (0%) RbME−/− mice developed mammary neoplasms by 700 days of age (Fig. 1 B). Fifteen out of 17 (88%) p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice developed mammary neoplasms. All neoplasms arising in p53ME−/− and p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice have lost both copies of p53 and p53 and Rb, respectively (Suppl. Fig. 2). The median tumor-free survival of p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice was significantly shorter than that of p53ME−/− mice (P=0.0058). Thus, although Rb inactivation alone is insufficient for initiation of mammary carcinogenesis, p53 and Rb cooperate in suppression of carcinogenesis.

In agreement with the low frequency (1% of cells) of Cre expression in the mammary glands, the majority of mice developed only one mammary tumor (Suppl. Table 2). Eleven (3 out of 27) and 10 (4 out of 40) percent of p53ME−/− and p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice, respectively developed lung metastasis. Eight out of 27 (30%) and 10 out of 43 (23%) neoplasms in p53ME−/− and p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice, respectively, were relatively well differentiated carcinomas (Fig. 1 C and Suppl. Table 2). In these tumors neoplastic cells formed solid, glandular and trabecular patterns and were separated by desmoplastic stroma. One tumor in each group was an adenosquamous carcinoma. The remaining tumors were poorly differentiated carcinomas and consisted of cytokeratin (CK) 8-positive epithelioid, spindle or polygonal, frequently pleomorphic, cells. The degree of pleomorphism was particularly notable in two out of 18 (11%) and nine out of 32 (28%) neoplasms from p53ME−/− and p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice respectively. The frequency of poorly differentiated carcinomas of p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice was also somewhat higher than that of p53ME−/− mice (67% vs. 75%). However, both parameters were not statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test two-sided P=0.2866 and 0.579, respectively). Seven out of 32 poorly differentiated neoplasms of p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice but none out of 18 those of p53ME−/− mice contained significant (over 5%) areas of solid or glandular differentiation (Fisher’s exact test two-sided P=0.04). SMA, CK5 or CK6 positive cells were present in one third of neoplasms but did not exceed 3-5% of tumor cells. As expected from the loss of Rb function, neoplastic cells deficient for both p53 and Rb proliferated significantly faster than cells with p53 deficiency alone in histologically comparable areas (Suppl. Fig. 3). In agreement with preferentially luminal differentiation of the neoplasms, all of them (10 out of 10 in each group) expressed ERα in at least 25% of cells (Fig. 1 C). All tumors also expressed a downstream target of ERα, progesterone receptor (PR). At the same time, as characteristic for luminal subtype B carcinomas (Hu et al., 2006), all tumors expressed mitotic checkpoint protein Mad2.

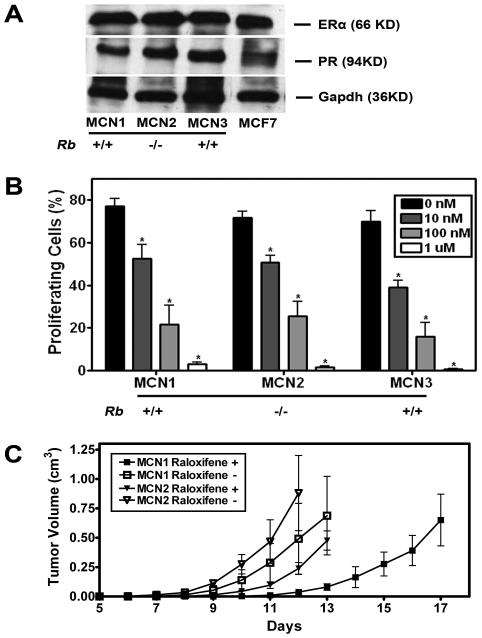

Mammary neoplasms respond to hormone therapy with a selective estrogen receptor modulator

In addition to detection of ER and PR in all mammary carcinomas by immunohistochemical analysis (Fig. 1 C), we confirmed their expression in the cell lines MCN1, MCN2 and MCN3 established from those tumors (Fig. 2 A and Suppl. Table 3). To determine if tumors respond to hormone therapy, effects of raloxifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), which competes with endogenous estrogen for ERα binding (Sporn et al., 2004), were tested in all three mammary carcinoma cell lines. According to the BrdU incorporation assay, raloxifene treatment resulted in a dose dependent cell proliferation decrease in all three cell lines within concentration range from 10 nM to 1 μM (P<0.05 in all treatments and cell lines, Fig. 2 B). Raloxifene also significantly delayed the neoplastic growth after mammary fat pad transplantation of MCN1 (P=0.0132) and MCN2 (P=0.0088; Fig. 2 C). Taken together, these results confirm functional status of ERα in p53ME−/− and p53ME−/− RbME−/−mouse models of mammary carcinoma.

Figure 2. Mammary neoplasms respond to hormone therapy with raloxifene.

A, Western blot of ERα, and PR in MCN1, MCN2, MCN3 and MCF7 cell lines. To normalize for differences in loading, the blots were stripped and reprobed with mouse anti-Gapdh monoclonal antibody. B, Effects of raloxifene on proliferation of mammary carcinoma cells as determined by BrdU incorporation and compared to control (Mean ± SD, n=3 in each group, P < 0.05, indicated as *). All MCN cell lines are p53 null and have either two (+/+) or no (−/−) functional copies of the Rb gene. C, Effects of raloxifene on tumor growth in vivo. MCN1 and MCN2 cells (106) were transplanted to cleared fad pad of 4 weeks old FVB mice. According to the tumor volume measurements 12 days after transplantation, raloxifene (Raloxifene +) significantly delays the tumor growth of MCN1 (P=0.0132) and MCN2 (P=0.0088) cells as compared to control group without raloxifene treatment (Raloxifene −).

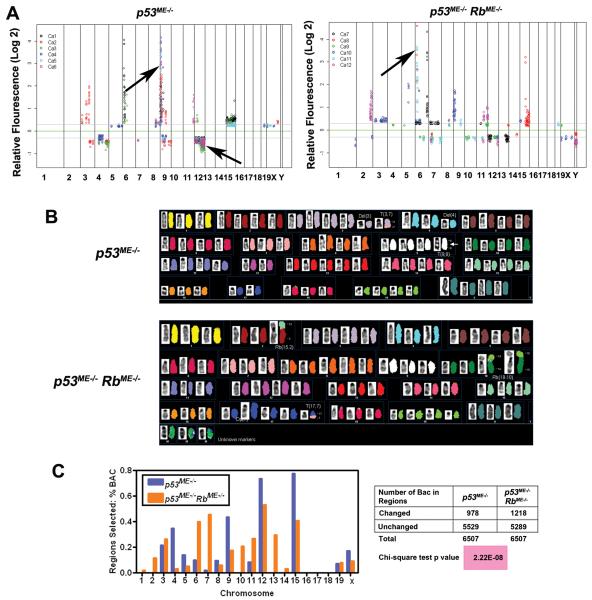

Rb inactivation affects the pattern of secondary genetic alterations and increases genomic instability of mammary cancer associated with p53 deficiency

To determine whether there were any specific genetic aberrations associated with mammary carcinomas in our models, comparative genomic hybridization array (aCGH) analyses were performed on DNA isolated from these neoplasms (Fig. 3). The genome of p53 deficient tumors was characterized by a recurrent amplification (5 out of 6 tumors) at chromosomal band 9A1. Additionally, chromosome bands 12C2 - 12F1 were deleted in 5 out of 6 mammary tumors from p53ME−/− mice. Interestingly, in mammary tumors from p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice (Fig. 3 A), only 1 out of 6 tumors had a genomic amplification of 9A1 and none carried the deletion at 12C2 - 12F1. At the same time, 5 out of 6 (83%) mammary tumors from p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice had amplification at chromosome 6A1 and 6A2, while only 2 out 6 (33%) mammary tumors from p53ME−/− mice had amplification of these regions. Analysis by SKY showed chromosomal aberrations that resulted in a net gain of chromosome 9A1 (Fig. 3 B).

Figure 3. Genomic alterations in mammary carcinomas of p53ME−/− and p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice.

A, The log2 ratios for each chromosome in order from 1p to Xqter. (Top) Chromosomal regions with consistent gene copy number alterations (5 out of 6 samples, arrows). Carcinomas of p53ME−/− mice: significant gain and loss are mapped to the chromosomal bands 9A1 and 12C2 - 12F1, respectively. Carcinomas of p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice: significant gain at 6A1 and 6A2. B, SKY analysis of chromosome metaphase spreads of primary tumor cells (Top, p53ME−/−; Bottom, p53ME−/− RbME−/−). Karyotype of metaphase spread with classification pseudo-color and its corresponding inverted-DAPI. Arrow, net gain of chromosome 9A1 in tumors of p53ME−/− mice. C, (Left) Comparison of aCGH profiles of tumors from p53ME−/− and p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice. (Right) Chi-square test of the number of BAC in altered chromosome region of tumors from p53ME−/− and p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice.

aCGH data also demonstrated that neoplasms from p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice contained 20% more genomic imbalances compared to those in p53ME−/− mice (Fig. 3 C). Consistently, SKY analysis demonstrated a high degree of aneuploidy and an increased rate of structural chromosomal instability (P=0.0213) in carcinomas from p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice. This was measured as the presence of de novo non-clonal chromosome aberrations per cell (Fig. 3 B and Suppl. Table 4).

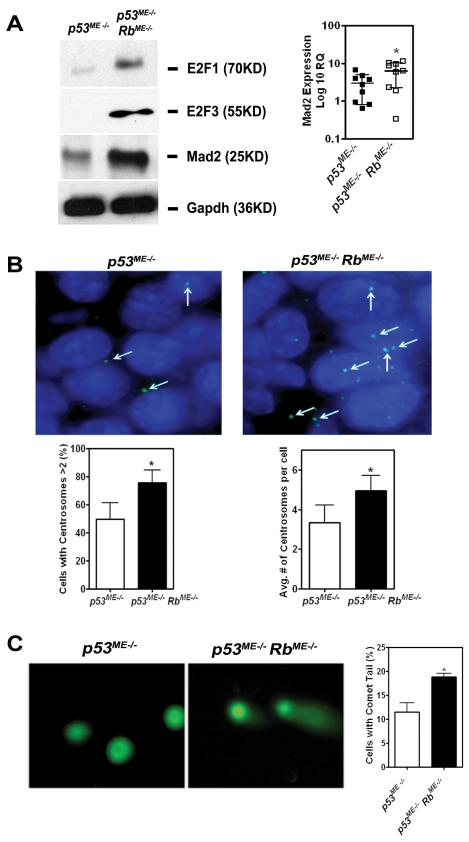

Previous studies demonstrated that E2F family, one of the main Rb downstream effectors, mediates DNA double strand break accumulation and contribute to mitotic defects and genomic instability (Pickering and Kowalik, 2006) at least in part by activating Mad2 expression (Hernando et al., 2004). Consistently with those observations, higher levels of E2F1, E2F3 and Mad 2 were found in primary tumors from p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice as compared to p53ME−/− mice (Fig. 4 A). Accordingly, tumor cells deficient for both p53 and Rb contained higher subpopulation with multiple centrosomes (Fig. 4 B) and double strand breaks (Fig. 4 C) according to γ-tubulin staining and neutral comet assays, respectively.

Figure 4. Rb inactivation promotes genomic instability.

A, (Left) Western blot of E2F1, E2F3, and Mad2 in primary tumor cells from p53ME−/− and p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice. (Right) Relative Mad2 mRNA expression in carcinomas of p53ME−/− and p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice (Mean ± SD, 2.9 ± 2.1 versus 6.3 ± 4.0, n=10, P = 0.0411, indicated as *). B, (Top) Immunofluorescence staining (γ-tubulin) of centrosomes in primary tumor cells from p53ME−/− and p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice. (Bottom Left) Percentage of cells with more than 2 centrosomes is higher in cells from p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice, as compared to that in cells from p53ME−/− mice (75.8 ± 9.0 versus 49.6 ± 12.0, n=10, P = 0.0083). (Bottom Right) Tumor cells from p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice have higher average number of centrosomes per cell than that from p53ME−/− mice (4.96 ± 0.76 versus 3.34 ± 0.90, n=10, P=0.0152,). C, (Left) Representative images of neutral comet assay with primary tumor cells from p53ME−/− and p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice. (Right) Tumor cells from p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice have higher percentage of cell with comet tail as compared to p53ME−/− (18.9 ± 1.3 versus 11.5 ± 3.3, n=10, P = 0.0232).

cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1 are regulated by E2F and cooperate in mammary carcinogenesis

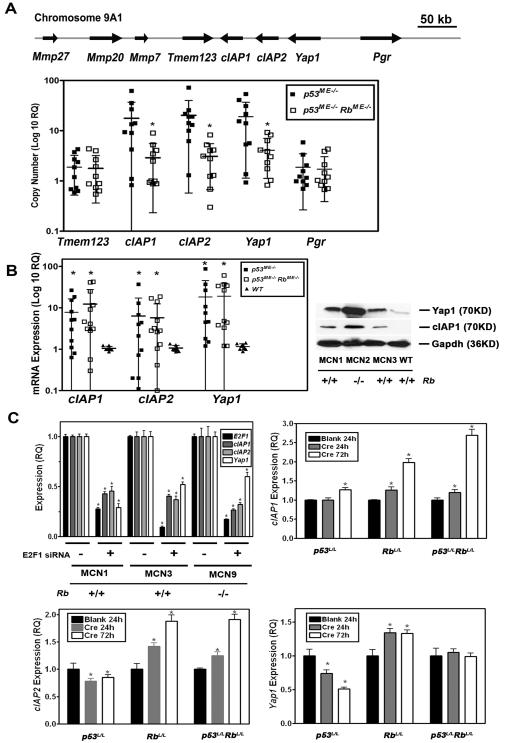

The chromosome band 9A1 is orthologous to human chromosome band 11q22, which is frequently amplified in human cancers (Overholtzer et al., 2006) and contains the protooncogenes cIAP1 (Birc2), cIAP2 (Birc3) and Yap1. Given the potential importance of these genes for human cancer we fine mapped the extent of the amplicon by demonstrating lack of amplification of the flanking genes Tmem123 (Porimin) and Pgr (PR) genes by real time quantitative PCR (qPCR) in tumors from p53ME−/− mice (Fig. 5 A). At the same time, qPCR was also used to confirm the aCGH results indicating lack of recurrent amplification of cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1 in carcinomas of p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice.

Figure 5. Copy number and expression of cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1 in mammary carcinomas of p53ME−/− and p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice.

A, (Top) The map of the genes in the chromosome 9A1 region under study. (Bottom) Mammary carcinomas from p53ME −/− mice have higher cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1 gene copy number than those from p53ME −/− RbME −/− mice (Mean ± SD, n=10 in each group). cIAP1: 17.6 ± 19.2 versus 3.1 ± 3.1; cIAP2: 20.3 ± 19.7 versus 3.1 ± 2.4 and Yap1: 19.03 ± 17.96 versus 4.08 ± 2.95, respectively. * indicates P < 0.05. DNA copy number of Tmem123 and Pgr is similar between the cells from these two different types of mice (Tmem123: 1.88 ± 1.36 versus 1.78 ± 1.41 and Pgr: 1.87 ± 1.6 versus 1.72 ± 1.32). Quantitative PCR. B, (Left) Overexpression of cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1 in mammary carcinomas from both p53ME −/− and p53ME −/− RbME −/− mice as compared to the wild-type (WT) mammary epithelium (Mean ± SD, n=10 in each group) cIAP1: 7.80 ± 8.61 (p53ME −/−), 12.30 ± 15.30 (p53ME −/− RbME −/−) versus 1.05 ± 0.13 (WT); cIAP2: 6.31 ± 10.89 (p53ME −/−), 5.73 ± 6.72 (p53ME −/− RbME −/−) versus 1.06 ± 0.18 (WT), and Yap1: 18.29 ± 27.12 (p53ME −/−), 19.12 ± 20.15 (p53ME −/− RbME −/−) versus 1.16 ± 0.19 (WT), * indicates P < 0.05. Quantitative RT-PCR. (Right) Western blot of cIAP1 and Yap1 in MCN1, MCN2, MCN3 cells and primary culture of wild type mammary epithelium (WT). C, Expression of E2F1, cIAP1, cIAP2, and Yap1 after E2F1 knockdown by E2F1 siRNA as compared to scrambled siRNA control (Mean ± SD, n=4 in each group; P < 0.05 is indicated as*). All MCN cell lines are p53 null and have either two (+/+) or no (−/−) functional copies of the Rb gene (Top Left). Relative expression (Mean ± SD, n=4 in each group) of cIAP1 (Top Right), cIAP2 (Bottom Left) and Yap1 (Bottom Right) collected at 24 and 72 hours after treatment of mammary epithelium cells from floxed p53 (p53L/L), Rb (RbL/L), or p53 and Rb (p53L/LRbL/L) mice with blank Adenovirus (Blank) or AdCre (P < 0.05 is indicated as *). Quantitative RT-PCR.

Notably, mRNA expression analyses demonstrated that all three genes were similarly overexpressed in carcinomas of both p53ME−/− and p53ME−/− RbME−/− mice (Fig. 5 B). Since promoter regions of all three genes contain E2F binding sites (Suppl. Fig. 4), E2F regulation was tested by E2F1 knockdown on cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1 expression. Consistent with the Rb/E2F regulation model, knockdown of E2F1 by siRNA in mammary carcinoma cell lines resulted in significant (P<0.05) downregulation of cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1 24 hours after transfection (Fig. 5 C). Cre-loxP-mediated inactivation of Rb alone or together with p53 in primary mammary epithelial cells resulted in increased expression of cIAP1 and cIAP2 at 24 hours followed by further increase at 72 hours (Fig. 5 C). Inactivation of p53 alone had only marginal effect on expression of cIAP1 and led to decreased expression of cIAP2. Furthermore, induction of p53 expression by treatment with doxorubicin did not result in decreased expression of cIAP1 and cIAP2 as compared to p53 deficient cells (Suppl. Fig. 5). Yap1 expression also increased after Rb inactivation but lacked significant increase immediately after simultaneous inactivation of p53 and Rb genes. Computational analysis of the Yap1 gene identified a putative p53 binding site in the intron 1 (Suppl. Fig. 4). Consistently, decrease and increase of Yap1 expression was observed after deletion and doxorubicin-induced upregulation of p53, respectively (Fig. 5 C and Suppl. Fig. 5 C). Taken together, these observations indicate that defective Rb/E2F pathway was likely to be sufficient for immediate upregulation of cIAP1 and cIAP2, as well as later overexpression of Yap1, thereby avoiding the need for genomic amplification of these genes during mammary carcinogenesis.

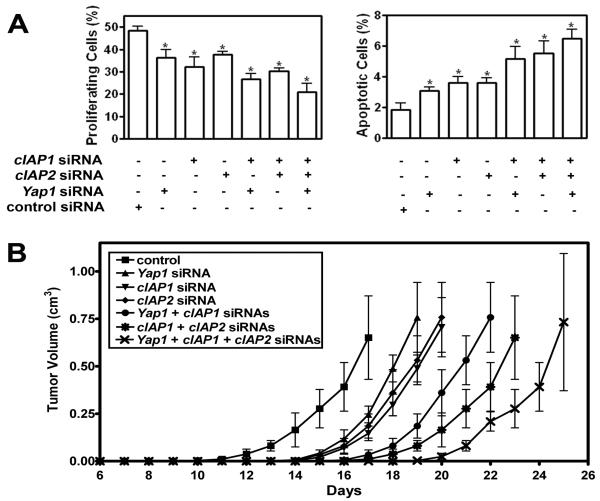

To further elucidate the roles of cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1 in mammary carcinomas we used siRNA to knockdown the expression of these genes (Fig. 6 and Suppl. Fig. 6). Downregulation of each gene individually resulted in significant decrease in cell proliferation and increase in apoptosis (Fig. 6 A). The effect was even more pronounced after two or all three genes were inactivated simultaneously. To test tumorigenic properties of cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1, respective siRNAs were delivered with atelocollagen to mammary carcinoma cells transplanted to the mammary fat pad. Downregulation of each gene individually resulted in deceleration of tumor growth. Similarly to cell culture results, suppression of tumor growth was most pronounced by simultaneous downregulation of 2 and particularly all 3 genes. Taken together, these observations demonstrate that cIAP1, cIAP2, and Yap1 are important for mammary carcinogenesis associated with p53 deficiency and cooperate to promote neoplastic growth.

Figure 6. cIAP1, cIAP2, and Yap1 cooperate in mammary carcinogenesis.

A, Downregulation of either cIAP1, cIAP2 or Yap1 by siRNA in primary mammary carcinoma cells leads to decreased cell proliferation (Left) and increase of apoptosis (Right) as compared to scrambled siRNA control. Both effects are more pronounced after inactivation of any two or all three genes. (Mean ± SD, n=4 in each group, P<0.05, indicated as*). B, Effect of cIAP1, cIAP2 or Yap1 knockdown on tumor growth (Mean ± SD, n=4 in each group). According to the tumor volume measurements 17 days after transplantation, downregulation of cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1 by siRNA in MCN1 mammary carcinoma cells decelerates tumor growth as compared to control (P = 0.014, P = 0.0056, and P = 0.0091, respectively). Combination of cIAP1 and cIAP2, cIAP1 and Yap1, or all three genes further delays the tumor growth (P = 0.0022, P = 0.0073, and P = 0.0069, n=4, respectively).

Discussion

Human sporadic cancers have a broad repertoire of genetic changes and understanding of their contributions to major pathways defects is of critical importance. Mouse models of human cancer have been shown to serve as useful systems to facilitate identification of genetic alterations essential for carcinogenesis by comparative oncogenomic approaches (Kim et al., 2006, Maser et al., 2007, Zender et al., 2006). During the past two decades it has become increasingly clear that different cancer phenotypes of mouse models may reflect distinct initiating genetic and epigenetic alterations (Cardiff et al., 2000). Indeed, combination of p53 and Brca1 somatic inactivation results in formation of tumors mimicking human BRCA1-mutated ER negative basal-like cancer (Liu et al., 2007). At the same time inactivation of p53 together with E-cadherin leads to ER negative metastatic lobular mammary carcinoma (Derksen et al., 2006). Mammary neoplasms associated with p53 deficiency alone were reported to be either ER negative (Liu et al., 2007) or both ER negative and positive, depending on MMTV or WAP promoter used to express Cre in deleter mouse strains (Lin et al., 2004).

Since available mammary epithelium-specific deleter strains express Cre in lymphoid and other tissues, we have established an additional MMTV-Cre strain with a highly mammary epithelium-restrictive expression pattern. Interestingly, different from other MMTV-Cre based models and likely due to transgene positional effects, the cancers forming in our model are ER positive and have no or very limited non-luminal differentiation typical for such tumor types as adenomyoepthelial, adenosquamous and basal-like carcinomas. Thus interpretation of cancer phenotypes is also likely to be affected by variations in transgene expression patterns and transformation of distinct cell lineages and their subpopulations.

Based on the expression of markers for luminal differentiation, such as ER and CK8, combined with p53 deficient status, as well as expression of Mad2 and cIAP2 (Frasor et al., 2009), this model may represent an attractive tool for studies of human luminal subtype B breast cancers (Hu et al., 2006, Sorlie et al., 2001). This model is also particularly amenable to further experiments because of responsiveness of mammary carcinomas to an estrogen antagonist as well as availability of established syngeneic mammary carcinoma cell lines. Considering the 50% frequency of mammary carcinomas and long latency period of carcinogenesis in p53ME−/− mice, they are particularly well suited for assessment of other endogenous and exogenous factors which are expected to accelerate carcinogenesis.

Our studies confirmed previous observations that sporadic inactivation of Rb alone is insufficient for the initiation of mammary carcinogenesis (Robinson et al., 2001). Furthermore, the use of a Cre-loxP approach allowed direct genetic demonstration that Rb loss-of-function, without inactivation of p107 and/or p130, leads to acceleration of mammary carcinogenesis associated with p53 inactivation. At least in part, this effect may be explained by increased proliferation rate of Rb-deficient neoplastic cells.

p53 and Rb pathways are extensively connected and their inactivation frequently cooperates during carcinogenesis presumably by abrogating E2F-induced p53-mediated apoptosis or senescence (Sherr and McCormick, 2002, Sherr, 2004). Our study illuminates genomic instability as another mechanism of p53 and Rb cooperation. Genomic instability is a hallmark of most human cancers. Although much attention has been focused on the role of p53 in the maintenance of genomic stability, an accumulating body of evidence indicates Rb as another important player (Knudsen et al., 2006). Rb inactivation has been shown to promote genomic instability by uncoupling cell cycle progression from mitotic control (Hernando et al., 2004) and by mediating DNA double strand break accumulation (Pickering and Kowalik, 2006) in cell culture models. In vivo, Rb loss results in ectopic cell cycle, compromises ploidy control in mouse liver (Mayhew et al., 2005) and promotes hepatocarcinogenesis (Mayhew et al., 2007, Reed et al., 2009). Our study extends these observations by demonstrating higher levels of the E2F downstream target Mad2, higher rates of double strand DNA breaks and centrosome amplification and overall increase in chromosomal structural instability in mammary carcinomas deficient for both p53 and Rb. Further studies should determine if Rb loss leads to similar consequences in the normal mammary epithelium. It also remains to be demonstrated whether observed increase in phenotypical diversity and trend towards increase of cellular polymorphism and poorer differentiations in carcinomas of p53ME−/−RbME−/− mice are a result of elevated genomic instability associated with Rb deficiency.

Using aCGH, we identified a number of recurrent genetic alterations in our mammary carcinoma models. It is likely that each of these alterations has individual contributions to carcinogenesis. The amplification of 9A1 locus is of a particular interest because it includes protooncogenes, such as cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1. cIAP1 and cIAP2 encoded proteins contain baculoviral IAP repeat (BIR) domain and are key regulators of apoptosis, cytokinesis, and signal transduction. Both genes are are commonly amplified in many human cancers (reviewed in LaCasse et al., 2008). Yap1 contains a WW domain and binds to the SH3 domain of the tyrosine kinase Yes. It has been shown to be expressed in common solid tumors (Steinhardt et al., 2008) and to have tumorigenic properties in both liver (Zender et al., 2006) and breast cancer (Overholtzer et al., 2006). Considering the high frequency of 9A1 locus amplification in neoplasms of p53ME−/− mice, this model may prove to be very valuable for further studies of mechanisms involved in amplification of human orthologous genes on chromosome 11q22.

Amplification of both cIAP1 and Yap1 was observed in 4 out of 7 tumors in a transplantable mouse model of liver cancer based on transduction of p53 deficient fetal hepatoblasts with Myc retrovirus (Zender et al., 2006). At the same time, amplification of cIAP1 and cIAP2, together with matrix metalloproteinase MMP13, was observed in 5 out of 41 osteosarcomas (Ma et al., 2009). Yap1 amplification was detected in one out of 15 mammary tumors of MMTV-Cre Brca1floxP/− p53+/− mice. However, amplification of Yap1 was detected in none of over 100 sporadic human breast cancers (Overholtzer et al., 2006). Our observations of E2F-mediated control of cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1 may explain how dysfunctional Rb/E2F pathway may substitute for recurrent amplification of these genes. Since alterations in the Rb pathway are quite common in mouse and human tumors, including mammary carcinomas, this mechanism may also explain differences in frequencies of cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1 amplification among various tumor types.

Our results demonstrate that cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1 overexpression is critical for mammary carcinogenesis associated with p53 mutations. It is of interest that overexpression of cIAP2 has been recently reported to be associated with luminal subtype B of breast cancer (Frasor et al., 2009). Further studies will examine whether tumors of this subtype also overexpress cIAP1 and Yap1. Cooperation among cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1 in promoting tumorigenicity observed in our work is consistent with previously reported cooperation between cIAP1 and Yap1 in hepatocarinogenesis (Zender et al., 2006). Recently a broad variety of IAP molecule antagonists has been developed (LaCasse et al., 2008). Our results indicate that their application may be particularly effective in combination with downregulation of Yap1.

In summary, we established a new mouse model of sporadic ER positive luminal mammary carcinoma associated with p53 inactivation. We demonstrated that Rb deficiency accelerates mammary carcinogenesis and leads to increased genomic instability and to a different spectrum of recurrent genomic alterations. Of particular interest, genes of chromosome band 9A1, namely cIAP1, cIAP2 and Yap1, were shown to be important for mammary carcinogenesis. We proposed the E2F-mediated mechanism of their regulation and established cooperation among all three genes in promoting neoplastic growth. These observations provide the basis for further elucidation of cooperation of these genes in human cancers and lay the ground for rational development of therapeutic approaches in preclinical settings.

Materials and Methods

Mouse breeding

Male MMTV-Cre transgenic mice were crossed with female p53floxP/floxP (p53L/L), RbfloxP/floxP (RbL/L) or p53floxP/floxPRbfloxP/floxP (p53L/LRbL/L) mice to achieve, respectively, inactivation of p53 or Rb alone or together in the mammary epithelium. The resulting MMTV-Cre, p53L/L, MMTV-Cre, RbL/L and MMTV-Cre, p53L/L RbL/L mice, were designated as p53ME−/−, RbME−/−, and p53ME−/− RbME−/−, respectively. Reporter mice Gt(ROSA)26SorTM1sor (Chai et al., 2000, Jiang et al., 2000) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Mice carrying conditional alleles for p53 (floxed exon 2-10) and/or Rb (floxed exon 19) were described elsewhere (Jonkers et al., 2001, Marino et al., 2000). All mice were placed on FVB/N genetic background by at least 10 backcrosses and only nulliparous females were used. All mice were maintained identically, following recommendations of the Institutional Laboratory Animal Use and Care Committee.

Pathological evaluation

Mice were euthanized when mammary tumors reached 1 cm in diameter, at 700 days of age or after becoming moribund. Animals were evaluated grossly during necropsy and subjected to the systematic pathological assessment as descried earlier (Flesken-Nikitin et al., 2003, Zhou et al., 2006, Zhou et al., 2007). All lesions were identified according to the Classification of Neoplasia of Genetically Engineered Mice (Cardiff et al., 2000) endorsed by the Mouse Models of Human Cancer Consortium (NIH/NCI).

Histochemical analyses

Immunohistochemical analysis of paraffin sections of paraformaldehyde-fixed tissue was done by a modified avidin-biotin-peroxidase (ABC, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) technique with antigen retrieval as described earlier (Zhou et al., 2006). Primary antibodies to the following antigens were used: cytokeratin 5 (CK5, Covance, Berkeley, CA, 1:1000), CK6, (Covance, 1:300), CK8 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, 1:50), Ki67 (Novocastra Laboratories, Bannockburn, IL, 1:1000) smooth muscle actin (SMA, Spring Bioscience, Fermont, CA, 1:300), estrogen receptor α (ERα; Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, 1:200), and progesterone (PR; Santa Cruz, 1:200). Enzymatic detection of bacterial β-galactosidase was performed as previously described (Flesken-Nikitin et al., 2003, Zhou et al., 2007). All quantitative analyses were performed on digitally captured images as described in (Zhou et al., 2006).

Cell culture

To prepare mammary epithelial cells, mammary glands were dissected from 3-6 months old females. The tissue was placed in EpiCult-B medium (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC) with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 300 U/ml collagenase (StemCell Technologies) and 100U/ml hyaluronidase (StemCell Technologies) for 8 hours at 37°C. The dissociated tissue fragments were resuspended in 0.64% NH4Cl for lysis of the red blood cells. The further dissociation of fragments was obtained by their gentle pipetting in 0.25% Trypsin (Cellgro) for 2 min, followed by placing into 5 mg/ml dispase (StemCell Technologies) and 0.1 mg/ml DNase (StemCell Technologies) for 3 min and filtration through a 40-μm mesh. Derivation of MCN1, MCN2, MCN3 and MCN9 cells is described in Suppl. Table 3. Cells were cultured in HAM’s medium DMEM/F12, 50/50 Mix; Cellgro), supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-Glutamine, 1 mM Na-Pyruvate, 5 μg/ml Insulin. MCF7 (ATCC, Manassas, VA), a human breast cancer cell line, was cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 10 μg/ml Insulin. All cell lines were maintained in 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C.

Mammary fat pad transplantation, raloxifene and siRNA treatment

The No. 4 pair of mammary glands of anaesthetized, 3-week-old female FVB mice were surgically exposed under sterile condition. 106 tumor cells in 100 μl sterile PBS were injected into the cleared fat pad using a Hamilton syringe and 25 gauge needle and tumor formation monitored daily. Tumors were measured in three dimensions with a caliper, and the volume was calculated using the formula: V = π/ 6 (L × W × H). Raloxifene (10 μg/g body weight in DMSO) was applied s.c. to mice every two days from second day after cell transplantation. For siRNA treatment, 100 μl 5 μM siRNA was mixed with 100 μl atelocollagen (AteloGene™ Systemic Use; Koken, Tokyo, Japan) and administered locally as described (Minakuchi et al., 2004). All mice were monitored daily and the experiments were terminated after tumors reached volume 0.8 cm3.

Comparative genomic hybridization assay

Genomic DNA of mammary tumors from p53ME−/− and p53ME−/−; RbME−/− mice was assayed by comparative genomic hybridization. Genomic DNA from FVB female mice was used as a control. Genomic DNA was extracted using DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Mouse BAC genomic arrays, each composed of 6500 RPCI-23 or PRCI-24 clones, were prepared in the Roswell Park Cancer Institute Microarray Core Facility (Buffalo, NY). Data were analyzed as previously described (Zhou et al., 2006).

Other methods, including generation of transgene, genotyping, Western blotting analyses, proliferation and apoptosis assays, neutral comet and centrosome assays, AdCre, E2F1 knockdown and doxorubicin treatment assays, real-time PCR, spectral karyotyping (SKY) and statistical analyses, are described in Supplementary Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank David C. Corney for critical reading of this manuscript and Dr. Anton Berns (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for the generous gift of the p53floxP/floxP and RbfloxP/floxP mice. This work was supported by grants R01 CA96823 (NIH/NCI) and C023050 (NYSTEM) to AYN.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Borresen-Dale AL. TP53 and breast cancer. Hum Mutat. 2003;21:292–300. doi: 10.1002/humu.10174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco EE, Knudsen ES. RB in breast cancer: at the crossroads of tumorigenesis and treatment. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:667–671. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.6.3988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart DL, Sage J. Cellular mechanisms of tumour suppression by the retinoblastoma gene. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:671–682. doi: 10.1038/nrc2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiff RD, Anver MR, Gusterson BA, Hennighausen L, Jensen RA, Merino MJ, et al. The mammary pathology of genetically engineered mice: the consensus report and recommendations from the Annapolis meeting. Oncogene. 2000;19:968–988. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y, Jiang X, Ito Y, Bringas P, Han J, Rowitch DH, et al. Fate of the mammalian cranial neural crest during tooth and mandibular morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127:1671–1679. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derksen PW, Liu X, Saridin F, van der Gulden H, Zevenhoven J, Evers B, et al. Somatic inactivation of E-cadherin and p53 in mice leads to metastatic lobular mammary carcinoma through induction of anoikis resistance and angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:437–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, McArthur MJ, Montgomery CA, Jr., Butel JS, et al. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flesken-Nikitin A, Choi KC, Eng JP, Shmidt EN, Nikitin AY. Induction of carcinogenesis by concurrent inactivation of p53 and Rb1 in the mouse ovarian surface epithelium. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3459–3463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasor J, Weaver A, Pradhan M, Dai Y, Miller LD, Lin CY, et al. Positive cross-talk between estrogen receptor and NF-kappaB in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8918–8925. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geradts J, Wilson PA. High frequency of aberrant p16(INK4A) expression in human breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:15–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernando E, Nahle Z, Juan G, Diaz-Rodriguez E, Alaminos M, Hemann M, et al. Rb inactivation promotes genomic instability by uncoupling cell cycle progression from mitotic control. Nature. 2004;430:797–802. doi: 10.1038/nature02820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Fan C, Oh DS, Marron JS, He X, Qaqish BF, et al. The molecular portraits of breast tumors are conserved across microarray platforms. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, Schmitt EM, Halachmi S, Bronson RT, et al. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr Biol. 1994;4:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer Statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Rowitch DH, Soriano P, McMahon AP, Sucov HM. Fate of the mammalian cardiac neural crest. Development. 2000;127:1607–1616. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkers J, Meuwissen R, van der Gulden H, Peterse H, van der Valk M, Berns A. Synergistic tumor suppressor activity of BRCA2 and p53 in a conditional mouse model for breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2001;29:418–425. doi: 10.1038/ng747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Gans JD, Nogueira C, Wang A, Paik JH, Feng B, et al. Comparative oncogenomics identifies NEDD9 as a melanoma metastasis gene. Cell. 2006;125:1269–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen ES, Sexton CR, Mayhew CN. Role of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor in the maintenance of genome integrity. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:749–757. doi: 10.2174/1566524010606070749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperwasser C, Hurlbut GD, Kittrell FS, Dickinson ES, Laucirica R, Medina D, et al. Development of spontaneous mammary tumors in BALB/c p53 heterozygous mice. A model for Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:2151–2159. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64853-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaCasse EC, Mahoney DJ, Cheung HH, Plenchette S, Baird S, Korneluk RG. IAP-targeted therapies for cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:6252–6275. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Lewis B, Capuco AV, Laucirica R, Furth PA. WAP-TAg transgenic mice and the study of dysregulated cell survival, proliferation, and mutation during breast carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2000;19:1010–1019. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SC, Lee KF, Nikitin AY, Hilsenbeck SG, Cardiff RD, Li A, et al. Somatic mutation of p53 leads to estrogen receptor a-positive and -negative mouse mammary tumors with high frequency of metastasis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3525–3532. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Holstege H, van der Gulden H, Treur-Mulder M, Zevenhoven J, Velds A, et al. Somatic loss of BRCA1 and p53 in mice induces mammary tumors with features of human BRCA1-mutated basal-like breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12111–12116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702969104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma O, Cai WW, Zender L, Dayaram T, Shen J, Herron AJ, et al. MMP13, Birc2 (cIAP1), and Birc3 (cIAP2), amplified on chromosome 9, collaborate with p53 deficiency in mouse osteosarcoma progression. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2559–2567. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkin D. Germline p53 mutations and heritable cancer. Annu Rev Genet. 1994;28:443–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.28.120194.002303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino S, Vooijs M, van Der Gulden H, Jonkers J, Berns A. Induction of medulloblastomas in p53-null mutant mice by somatic inactivation of Rb in the external granular layer cells of the cerebellum. Genes Dev. 2000;14:994–1004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maser RS, Choudhury B, Campbell PJ, Feng B, Wong KK, Protopopov A, et al. Chromosomally unstable mouse tumours have genomic alterations similar to diverse human cancers. Nature. 2007;447:966–971. doi: 10.1038/nature05886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew CN, Bosco EE, Fox SR, Okaya T, Tarapore P, Schwemberger SJ, et al. Liver-specific pRB loss results in ectopic cell cycle entry and aberrant ploidy. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4568–4577. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew CN, Carter SL, Fox SR, Sexton CR, Reed CA, Srinivasan SV, et al. RB loss abrogates cell cycle control and genome integrity to promote liver tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:976–984. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek DW. Tumour suppression by p53: a role for the DNA damage response? Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:714–723. doi: 10.1038/nrc2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakuchi Y, Takeshita F, Kosaka N, Sasaki H, Yamamoto Y, Kouno M, et al. Atelocollagen-mediated synthetic small interfering RNA delivery for effective gene silencing in vitro and in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e109. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overholtzer M, Zhang J, Smolen GA, Muir B, Li W, Sgroi DC, et al. Transforming properties of YAP, a candidate oncogene on the chromosome 11q22 amplicon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12405–12410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605579103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering MT, Kowalik TF. Rb inactivation leads to E2F1-mediated DNA double-strand break accumulation. Oncogene. 2006;25:746–755. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed CA, Mayhew CN, McClendon AK, Yang X, Witkiewicz A, Knudsen ES. RB has a critical role in mediating the in vivo checkpoint response, mitigating secondary DNA damage and suppressing liver tumorigenesis initiated by aflatoxin B1. Oncogene. 2009;28:4434–4443. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley T, Sontag E, Chen P, Levine A. Transcriptional control of human p53-regulated genes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:402–412. doi: 10.1038/nrm2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson GW, Wagner KU, Hennighausen L. Functional mammary gland development and oncogene-induced tumor formation are not affected by the absence of the retinoblastoma gene. Oncogene. 2001;20:7115–7119. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy PG, Thompson AM. Cyclin D1 and breast cancer. Breast. 2006;15:718–727. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scambia G, Lovergine S, Masciullo V. RB family members as predictive and prognostic factors in human cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:5302–5308. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ, McCormick F. The RB and p53 pathways in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:103–112. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ. Principles of tumor suppression. Cell. 2004;116:235–246. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simin K, Wu H, Lu L, Pinkel D, Albertson D, Cardiff RD, et al. pRb inactivation in mammary cells reveals common mechanisms for tumor initiation and progression in divergent epithelia. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, Hastie T, Marron JS, Nobel A, et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8418–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn MB, Dowsett SA, Mershon J, Bryant HU. Role of raloxifene in breast cancer prevention in postmenopausal women: clinical evidence and potential mechanisms of action. Clin Ther. 2004;26:830–840. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt AA, Gayyed MF, Klein AP, Dong J, Maitra A, Pan D, et al. Expression of Yes-associated protein in common solid tumors. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1582–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TC, Cardiff RD, Zukerberg L, Lees E, Arnold A, Schmidt EV. Mammary hyperplasia and carcinoma in MMTV-cyclin D1 transgenic mice. Nature. 1994;369:669–671. doi: 10.1038/369669a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijnhoven SW, Zwart E, Speksnijder EN, Beems RB, Olive KP, Tuveson DA, et al. Mice expressing a mammary gland-specific R270H mutation in the p53 tumor suppressor gene mimic human breast cancer development. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8166–8173. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zender L, Spector MS, Xue W, Flemming P, Cordon-Cardo C, Silke J, et al. Identification and validation of oncogenes in liver cancer using an integrative oncogenomic approach. Cell. 2006;125:1253–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Flesken-Nikitin A, Corney DC, Wang W, Goodrich DW, Roy-Burman P, et al. Synergy of p53 and Rb deficiency in a conditional mouse model for metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7889–7898. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Flesken-Nikitin A, Nikitin AY. Prostate cancer associated with p53 and Rb deficiency arises from the stem/progenitor cell-enriched proximal region of prostatic ducts. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5683–5690. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.