Abstract

The mammalian diving response is a dramatic autonomic adjustment to underwater submersion affecting heart rate, arterial blood pressure, and ventilation. The bradycardia is known to be modulated by the parasympathetic nervous system, arterial blood pressure is modulated via the sympathetic system, and still other circuits modulate the respiratory changes. In the present study, we investigate the submergence of rats brought past their aerobic dive limit, defined as the diving duration beyond which blood lactate concentration increases above resting levels. Hemodynamic measurements were made during underwater submergence with biotelemetric transmitters, and blood was drawn from cannulas previously implanted in the rats' carotid arteries. Such prolonged submersion induces radical changes in blood chemistry; mean arterial Pco2 rose to 62.4 Torr, while mean arterial Po2 and pH reached nadirs of 21.8 Torr and 7.18, respectively. Despite these radical changes in blood chemistry, the rats neither attempted to gasp nor breathe while underwater. Immunohistochemistry for Fos protein done on their brains revealed numerous Fos-positive profiles. Especially noteworthy were the large number of immunopositive profiles in loci where presumptive chemoreceptors are found. Despite the activation of these presumptive chemoreceptors, the rats did not attempt to breathe. Injections of biotinylated dextran amine were made into ventral parts of the medullary dorsal horn, where central fibers of the anterior ethmoidal nerve terminate. Labeled fibers coursed caudal, ventral, and medial from the injection to neurons on the ventral surface of the medulla, where numerous Fos-labeled profiles were seen in the rats brought past their aerobic dive limit. We propose that this projection inhibits the homeostatic chemoreceptor reflex, despite the gross activation of chemoreceptors.

Keywords: diving response, respiration, central chemoreceptors, apnea, c-Fos, sudden infant death syndrome

the diving response is considered an organism's defense against asphyxia (29, 115). It is present in all mammals investigated (3, 7, 8, 14, 15, 30, 33, 35, 59, 61), including rats (65, 66, 68, 69, 71, 89, 90, 92). The diving response consists of at least three simpler reflexes involving a parasympathetically modulated bradycardia, a sympathetically modulated peripheral vasoconstriction, and an apnea [see Panneton et al. (92) for review].

Kooyman and colleagues (58, 60) defined the aerobic dive limit (ADL) in diving mammals as the diving duration beyond which blood lactate concentration increases above resting levels (62). Naturally diving mammals have several physiological adaptations that buffer against an underwater environment [see Meir et al. (75), for discussion], but most dives are shorter in duration than the ADL. Nevertheless, the diving mammals' blood chemistry is constantly in flux while underwater, since the animal is no longer breathing. Thus variables such as partial pressures of arterial oxygen (PaO2), arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2), arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2), and acidity (pH) are altered progressively (43, 75, 107) toward hypoxia, hypercapnia, and acidosis. Bert was the first to show that rats die after ∼2 min underwater (see 53), suggesting their ADL must be less than this time. Thus we investigated terrestrial laboratory rats after submergence until they developed extreme hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and acidemia to compare their ADL to that of diving mammals.

Chemoreceptors in both the carotid body and the central nervous system sense changes in the chemistry of blood and neural tissue and regulate ventilation appropriate to physiological needs. It is well known that increasing levels of PaCO2 and hydrogen ions, as well as decreasing levels of PaO2, increase ventilation by increasing both respiratory rate and depth (23, 32, 41, 44, 45); this reflex is called the respiratory chemoreceptor reflex. Despite this, diving animals by necessity cannot breathe while underwater, or they will drown. This has prompted suggestions that the respiratory chemoreceptor reflex is inhibited during underwater submersion (29). This is especially pertinent in mammals as they approach their ADL.

Previous investigations in rodents have shown that innervation of the nasal mucosa is important for cardiorespiratory behaviors similar to the diving response (22, 74, 130), since numbing the nasal mucosa inhibits them. The anterior ethmoidal nerve innervates the anterior nasal mucosa, as well as tissue surrounding the nares [see Panneton et al. (91), for review] and, when stimulated electrically, induces similar cardiac and respiratory depression (24–28, 70, 112). This nerve projects densely into areas of the medullary dorsal horn (MDH) (86, 91), where the autonomic responses due to stimulation of the nasal mucosa can be inhibited (87, 99). Moreover, neuronal transport techniques show that neurons in similar parts of the MDH project to numerous nuclei in the brain stem associated with cardiorespiratory behaviors (91, 96). The diving response must be driven via neurons within the medulla and spinal cord, however, since these behaviors still are elicited in vertebrates after transecting their brain stems rostral to the caudal pons (22, 52, 67, 92, 98).

In the present investigation, we submerged rats underwater past their ADL, while extracting arterial blood to measure blood chemistry. We also processed their brains immunohistochemically to visualize Fos protein induced with activation of neurons (6, 21) and compare these data with those derived from brains immunohistochemically stained for antibodies against Neun, which labels neurons. We finally describe a pathway from the ventral MDH, known to be important for the cardiorespiratory depression after nasal stimulation, to the ventral surface of the caudal medulla, where numerous chemoreceptors are known to reside (76, 77, 114). We show that the rats did not breathe while underwater, despite increases in multiple stimuli in blood chemistry, which usually induce hyperventilation. These experiments suggest numerous chemoreceptors are activated during prolonged underwater submersion and also suggest that brain stem circuits inhibiting ventilation are activated as well. These data support ideas of the diving response both being the most powerful autonomic response known, as well as fetal reflexes as a cause of the sudden infant death syndrome (64).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

ADL Experiments

Cardiovascular data.

Thirteen adult (∼275–325 g) Sprague-Dawley male rats were obtained commercially (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) and used in this study. All protocols were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Saint Louis University and followed the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Handling of Laboratory Animals.

Eight rats were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine (60:40 mg/kg ip), and the catheter of a biotelemetric transmitter (model PA-C40; Data Sciences International, DSI, St. Paul, MN) was inserted through their femoral arteries while the transmitter itself was implanted in their abdominal cavities. The rats healed for 5–7 days and then were anesthetized again and their anterior neck dissected. The right carotid artery was located and cut, and polyethylene tubing (PE 50) was inserted caudally to the level of the aortic arch. The distal end of the tubing was routed subcutaneously and exited on the dorsal cranium.

After 2–3 more days of postoperative recovery, cardiovascular data were obtained from all rats before, during, and after experimental submersion. The transmitter's broadcast was received with a radio receiver (model RLA3000, DSI), relayed to a Calibrated Pressure Analog Adaptor (model R11CPA, DSI), and transferred through an A/D interface (1401 plus, Cambridge Electronic Design, CED, Cambridge UK), stored in the computer, and analyzed using Spike 2 software (CED). Systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) were calculated, and heart rate (HR) determined by counting peaks of systolic pressure. We assumed the rats made no attempt to breathe while underwater, since none drowned during submergence.

Blood chemistry data.

Experiments commenced on each rat individually 2–3 days after the placement of the carotid cannulas. After a sterile 1-ml heparinized syringe was attached to the carotid cannula, ∼300 μl of blood (baseline sample) were withdrawn from the rat's carotid artery and placed on ice. The cannula then was flushed with sterile heparinized saline and readied for the next sample. The rats then were placed in a Plexiglas restrainer tube, the syringe assembly reattached, and another 300 μl of blood were withdrawn and stored in ice. Both the rat and tube then were submerged underwater (29–32°C) for 90–100 s. Blood was continuously withdrawn during this period, with each syringe taking ∼20 s to fill and be replaced with another. The rats were removed from the tube, and another 300 μl of arterial blood were withdrawn at ∼30 s, 2 min, and up to 20 min after emergence from the water. All blood samples were placed immediately on ice after collection. Although three rats were unconscious and not breathing after their removal from the tube, they were resuscitated within seconds by gently protracting the tongue. The cold blood samples were taken immediately to a blood-gas analyzer (ABL700 Radiometer, Westlake, OH) and an oximeter (OSM3, Radiometer, Westlake, OH) for measurement of PaO2, PaCO2, SaO2, acidity (pH), hemoglobin (Hb), and calculation of base excess (BE).

Immunohistochemical data.

The eight rats from the blood chemistry experiments remained in their home cage for 2 h after submersion. They then were deeply anesthetized (Sleepaway, 0.1 ml/100 g ip) and perfused through the heart with a peristaltic pump (Masterflex), first with a saline-procaine solution, followed immediately by a fixative of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.3). Brains and spinal cords were removed and refrigerated in the fixative with 20% sucrose at 4°C. The brains were blocked in the coronal plane using a precision brain slicer before frozen transverse sections (40 μm) were cut with a microtome.

Every third section was processed immunohistochemically overnight with antibodies against Fos (rabbit polyclonal IgG for c-fos p62; 1:20,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) mixed in 0.1 M PB with 0.3% Triton. On the following day, the sections were washed and then incubated for 1 h in goat anti-rabbit biotinylated secondary IgG (1:500; Vector Laboratories), washed, and then incubated in an ABC complex (Vectastain Elite; Vector Laboratories) for another hour. The Fos antigen was visualized in the brain stem with the chromogen diaminobenzidine enhanced with nickel ammonium sulfate catalyzed by hydrogen peroxide. Sections were mounted serially on gelatin-coated slides, counterstained with Neutral Red, dehydrated in alcohol, defatted in xylene, and coverslipped with Permount. Fos-positive neurons appeared as cells with black-labeled nuclei and were visualized with bright-field optics (Nikon E800). Two cases usually were processed simultaneously to minimize procedural differences in immunohistochemistry (i.e., slight differences in reaction times and/or dilution factors of the primary or secondary antibodies).

Neurons were considered Fos-positive if their nuclei contained the black immunoprecipitate. Fos-positive neurons in selected brain stem nuclei were photographed digitally (MicroImager II) with Northern Eclipse Software (Empix). Sections were drawn with a Nikon E600 microscope interfaced with Neurolucida software (MicroBrightField). The figures were standardized in Adobe Photoshop software (version 7) using levels, brightness, and contrast and aligned in Adobe Illustrator software (version 11). All nomenclature and abbreviations are from a stereotaxic rat atlas (102).

Tract-tracing Experiments

Five animals were anesthetized (vide supra) and secured prone in a flat skull position in a stereotaxic device. The skull was exposed via a dorsal incision, and the acromiotrapezius muscle split along the dorsal midline. After retracting the deep neck muscles laterally, the medulla oblongata was exposed after cutting the dura. Micropipettes (20 ∼ 25 μm outer diameter) were filled with 10% biotinylated dextran amine (BDA; Molecular Probes; 10,000 molecular weight) in saline and lowered into the ventral MDH. The carrier was angled anteriorly at 24° from vertical; the coordinates were 0.5 mm rostral to calamus scriptorius, 2.4–2.6 mm lateral to the midline, and 1.4 mm ventral from the dorsal surface of the brain stem. Tracers were deposited in the brain with a positive current (5 mA; 7 s on/off) via a silver wire inserted into the micropipette for 10–15 min using a constant-current device (MidGuard). The micropipette was left in place for 5 min after the injections. Wounds were washed with sterile saline and closed with silk.

After survivals of 7 to 10 days, the animals were deeply anesthetized and perfused, and their brains and spinal cords removed, refrigerated in fixative with 20% sucrose, and sectioned frozen (vide supra). A 1:3 series was then processed for BDA. Sections were washed three times with 0.1 M PB for 10 min and then in 0.1 M PB with 0.3% Triton for at least 5 min. The sections then were incubated to visualize the immunoprecipitate. The sections finally were rinsed, mounted on gelatinized slides, air-dried, counterstained with Neutral Red, dehydrated in alcohols, defatted in xylenes, and coverslipped with Permount. Sections were examined and reconstructed as above. Varicosities on labeled fibers were considered synaptic boutons.

Data Analysis

Means and standard errors (means ± SE) were determined for both hemodynamic and blood-gas measurements and compared with control values for significance (SPSS software, version 15). Cardiovascular and blood chemistry parameters during submersion were compared with data considered control. Control data were taken from the rats in the physiological experiments when they freely roamed in their home cages before submersion. A repeated one-way ANOVA revealed significant differences in these parameters from control values. This strict statistical analysis amplified the findings presented herein. Data are presented as means ± SE, and significance was calculated as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

All rats showed a marked drop in HR and an immediate but temporary increase in arterial blood pressure (ABP) to prolonged involuntary submersion (Fig. 1). Numerous brain stem neurons also were immunolabeled with Fos after this prolonged submergence. Tract tracing experiments showed projections from the MDH to the caudal superficial ventral medulla, where neurons immunolabeled with Fos after prolonged submergence also were found.

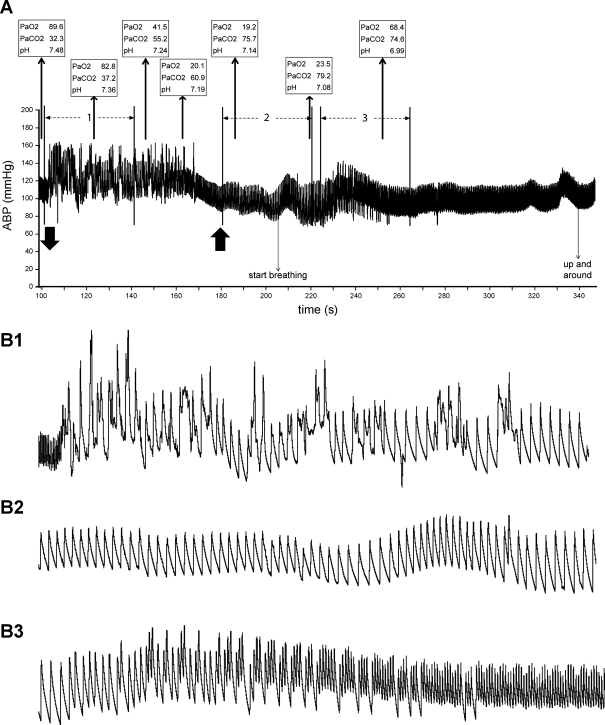

Fig. 1.

Traces illustrating the typical cardiovascular behavior of a submerged rat brought toward its dive limit. A: trace illustrates changes in cardiovascular dynamics, as well as arterial blood chemistry over a 250-s experiment. Downward-pointing arrow on bottom indicates submersion, while the upward-pointing arrow to the right marks exit from the water. There was an immediate bradycardia and increase in arterial blood pressure (ABP) on submersion highlighted by numerous arrhythmias (the 40-s period marked 1 in A is seen on an expanded time scale in B1). After ∼70 s of submersion, ABP fell in all rats, and the arrhythmias ceased (the 40-s period marked 2 in A is shown at expanded time scale in B2). This behavior continued until the rat exited the water and started to breathe again. Heart rate gradually accelerated with respiratory activity, but arrhythmias returned temporarily (the 40-s period marked 3 in A is shown at expanded time scale in B3). Note that the rat became extremely hypoxic, hypercapnic, and acidotic during submersion. PaO2, arterial Po2; PaCO2, arterial Pco2.

ADL Experiments

Cardiovascular data.

Both the bradycardia and the increase in ABP seen with underwater submersion were significantly different from control values obtained before submersion (Fig. 2, A and B). HR reached a nadir of 106 ± 7 beats/min in submerged rats, significantly (P < 0.001) different from control values of 461 ± 11 beats/min (Fig. 2A). The bradycardia was maintained throughout the period of submergence compared with predive, but was less intense during the last 10 s underwater; HR rose rapidly after the rat was taken from the water (Fig. 2A). There were numerous arrhythmias in these untrained rats for approximately the first 70 s that the rats were underwater (Fig. 1B1). A rhythmic cardiac cycle then appeared as the rat became more hypoxic, hypercapnic, and acidotic (Fig. 1B2); some rats apparently became unconscious during this time, since they stopped moving in the restrainer tube. On emersion, the heartbeats again became arrhythmic after respirations commenced and the rat awoke (Fig. 1B3) before settling into a normal cardiac rhythm (Figs. 1A), returning to control values 2 min after emersion (Fig. 2A).

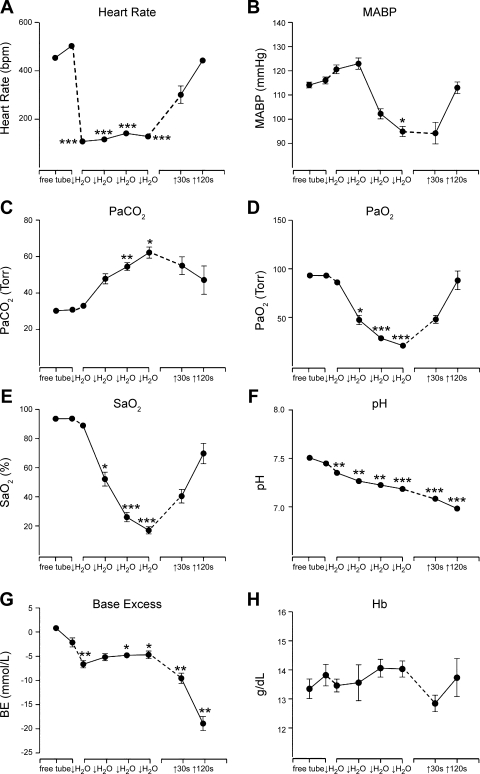

Fig. 2.

Line graphs illustrating the mean changes in hemodynamics and blood chemistry during prolonged underwater submersion. A: there was a dramatic bradycardia with submersion, which persisted while the rat was underwater. B: there also was a slight increase in mean ABP (MABP) initially, but pressure fell during later stages of submersion before rising to control levels after the rat emerged and started breathing. PaCO2 rose dramatically (C), while PaO2 (D) and arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2; E) fell sharply in the rats while underwater, reaching levels at which most mammals are induced to breathe. The blood also quickly became very acidotic (F) with great loss of base excess (BE; G). H: hemoglobin (Hb) fluctuated nonsignificantly during the period of underwater submersion and afterwards. The first point represents data from rats free in their home cage, while the second data point is after their enclosure in the restraining tube. Dashed lines mark time either just before submersion or out of the water. The four middle data points represent time underwater; each slash marks ∼20 s. Points without error bars represent very small standard errors. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001.

MABP rose from 115 ± 2 mmHg in control periods to 124 ± 3 mmHg after ∼30 s underwater (Fig. 2B), but then fell significantly (P < 0.05) to 98 ± 4 mmHg as the ADL was approached (Figs. 1A and 2B). MABP returned to control levels by 2 min after emersion from the water (Fig. 2B).

Blood chemistry data.

Partial pressures of carbon dioxide, oxygen, and oxygen saturation were measured throughout the experiments. Initially, PaCO2 was 30.3 ± 0.6 Torr and peaked significantly at 62.4 ± 3.7 Torr at the end of the submersion period (Fig. 2C). PaO2 dropped from 93.1 ± 1.6 Torr at control times to 21.8 ± 2.2 Torr at the end of submersion (Fig. 2D), which also was significant (P < 0.001). Oxygen saturation also dropped significantly (P < 0.001), changing from 93.7 ± 0.4 to 17.6 ± 2.8% at the end of submersion (Fig. 2E). All of these parameters approached control values within 2 min after emerging from the water. Blood acidity, however, continued to rise after the rat emerged from the water. pH fell significantly (P < 0.001) from control levels of 7.51 ± 0.01 to 7.18 ± 0.02 at the end of submersion and continued falling to 6.99 ± 0.02 2 min later (Fig. 2F). Similarly, BE initially fell significantly (P < 0.01) to −5.7 ± 0.6 after 20-s submersion from a control value of 0.86 ± 0.4, and continued to plummet rapidly to −18.2 ± 1.6 2 min after exit from the water (Fig. 2G). Hb concentration was never significantly different from control values.

Fos data.

Neurons immunolabeled with Fos protein were noted in numerous cell groups in the brain stem after prolonged submersion of 90–100 s (Fig. 3). Many of these nuclei were similar to those labeled during voluntary diving for shorter time periods (90). These nuclei included the caudal pressor area (CPA; Figs. 3A and 4, C and D), the MDH (Figs. 3, D–E, and 4, A–D), the lateral reticular nucleus, pars parvocellularis, subnuclei of the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) near the level of the obex (Fig. 4, D–E), as well as its subnucleus commissuralis (Figs. 3C and 4, B and C), the rostroventrolateral medulla (RVLM; Figs. 3G and 4F), the lateral medulla (Fig. 4, C–F), the nucleus raphe pallidus (Figs. 3H and 4, C–G), the nucleus raphe magnus and adjacent nucleus gigantocellular reticular nucleus, pars alpha (GiA; Fig. 4G), the A5 area (A5), the superior salivatory nucleus (SSn; Fig. 3J), and the nucleus locus coeruleus (LC; Figs. 3L and 4H). Fos protein also was immunolabeled in the medial and spinal vestibular nuclei (SpVe; Fig. 4, F and G), the ventral cochlear nuclei (Fig. 3I.2), and the dorsal tegmental nucleus (Figs. 3L and 4H) in the present study. Presumptive catecholaminergic neurons were labeled in all submerged rats; these have been discussed previously (72). We also will not report herein on labeling in the Kölliker-Fuse nucleus, and the external lateral and superior lateral subnuclei of the parabrachial complex, since the sections containing these nuclei were lost in three cases during the sectioning procedure. Although we did not quantify these neurons labeled with Fos in the present study, it was our qualitative perception that the number of labeled neurons was greater than that reported previously (90).

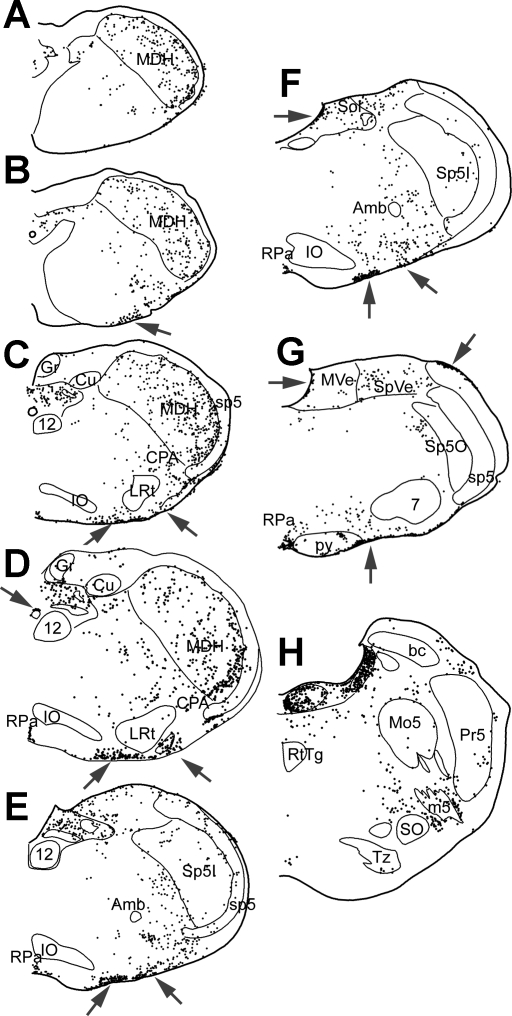

Fig. 3.

Photomicrographs illustrating the activation of numerous brain stem neurons by prolonged underwater submersion. Numerous neurons were immunolabeled for Fos in the caudal pressor area (CPA; circled; A) and pars commissuralis of nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS; C). The rostral medullary dorsal horn showed abundant Fos label in both its laminar (D) and alaminar parts (E); these areas closely match the terminal fields of the anterior ethmoidal nerve (outlined). The rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), where many neurons modulating ABP lie, showed intense immunolabeling (G); the boxed area shows the area we defined as the RVLM. Immunolabeling of cells on the ventral surface of the medulla, presumptive chemoreceptors, were robustly labeled for Fos throughout the medulla (B); the parapyramidal nucleus (PP) is shown here. Other cells on the brain stem surface also were activated by the prolonged hypoxia, hypercapnia, and academia, including the ectotrigeminal nucleus (E5; large arrows; F), the raphe pallidus (RPa; H), and a layer of cells covering the medial vestibular (MVe; I.1) and ventral cochlear nuclei (VCn; I.2). Similar cells were also noted in the dorsal half of the epithelium lining the central canal (C). Note that this epi-pia on the MVe and VCn looks similar to that seen on the ventral medullary surface (see Fig. 6). Neurons in the superior salivatory nucleus (SSn; J) were immunolabeled with Fos after these prolonged breath holds. Neurons in the caudal pons, including those of the A5 area and others surrounding the trigeminal nerve root (m5; K) and the locus coeruleus (LC; L), were well-labeled with Fos. Also note numerous small neurons labeled in the reticular formation just dorsal to the reticulotegmental nucleus (L; arrows). See Glossary for definitions of acronyms.

Fig. 4.

Line drawings illustrating the position of neurons and cells immunolabeled with Fos after prolonged underwater submersion. All labeled cells were drawn in these sections. Arrows point to numerous labeled cells on the ventral surface of the medulla, as well as some on dorsal and lateral surfaces. These include cells with both large (presumptive neurons) and small nuclei. See Glossary for definitions of acronyms.

The rats in the present study were submerged for 90–100 s, which was ∼70–80 s longer than previous studies (90, 92). This prolonged submersion induced radical changes in blood chemistry (Fig. 2), and such changes presumably activated both central and peripheral chemoreceptors. Numerous brain stem cells thought either to be putative respiratory central chemoreceptors or general chemoreceptors (32, 81) were labeled with Fos after these prolonged submersions. Numerous cells on the ventral surface of the medulla were labeled (Fig. 3B; arrows) from the level of the pyramidal decussation to the caudal pons.

Many of these cells were located in a thickened “epi-pia” (128), which was most prominent along the ventral medullary surface from the lateral border of the pyramidal tract medially to the medial border of the spinal trigeminal tract laterally (Fig. 4, arrows), lining the fourth ventricle (Figs. 3I.1 and 4, E–H), and over the cochlear nuclei (Fig. 3I.2). These immunoreactive profiles were generally of two sizes, and we questioned whether all were neurons. We thus compared the Fos data to laboratory reference sections immunostained with antibodies against Neun, a protein that marks neurons. Indeed, the thickened epi-pia covering most of the fourth ventricle and cochlear nuclei showed no immunostaining with Neun (Fig. 5A; arrows), and none of the smaller profiles on the ventral medullary surface was stained. What was seen, however, were neurons immunostained with Neun within the epi-pia. These more often were isolated (Fig. 5C; arrows), but sometimes were clumped, especially close to exits of cranial motor nerves, particularly the trigeminal (Fig. 3K), glossopharyngeal/vagus, and hypoglossal (Fig. 5H; arrows) nerves. Moreover, this distribution of Neun-stained profiles mimicked that of the larger profiles immunostained with Fos (Fig. 5, F and K; arrows), suggesting that these larger profiles were chemoreceptive neurons, probably respiratory, while the smaller immunoreactive profiles were general chemoreceptors. While there was no immunostaining of neurons with Neun in the thickened glia layer over the cochlear nucleus or lining the fourth ventricle, there were several neurons immunostained against both Fos and Neun juxtaposed to this membrane in the NTS and LC. Neurons in the retrotrapezoid nucleus (Rtz) were well labeled in these animals brought past their ADL [compare the immunoreactivity of these neurons immunostained for Neun (Fig. 5B) with those immunostained for Fos (Fig. 5E)] as were those in the paraolivary (POI; Figs. 5, G and J) and parapyramidal (Fig. 5, H and K) nuclei (PPy).

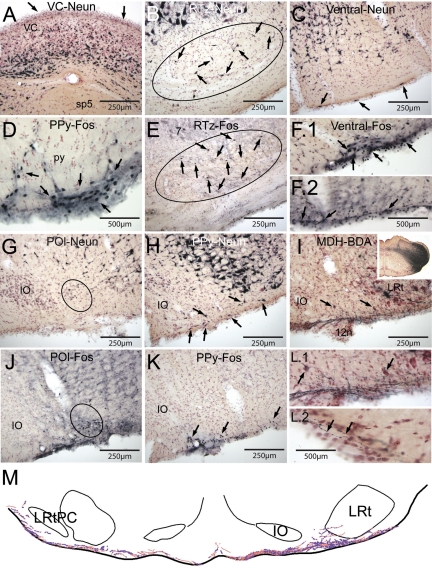

Fig. 5.

Photomicrographs of sections illustrating putative chemoreceptors and projections from the medullary dorsal horn to the ventral surface of the medulla. A: immunostaining for Neun, a neuronal marker, is shown through the ventral cochlear (VC) nucleus. Compare A to Fig. 3I.1; note that there are no cells labeled with Neun, suggesting no neurons are in this superficial layer. Numerous brain stem neurons were labeled showed Fos immunoreactivity in rats brought close to their aerobic dive limit, suggesting many of them were chemoreceptors. The retrotrapezoid nucleus (Rtz) contained numerous Fos-labeled neurons after underwater submersion (E; surrounded by oval; arrows point to Fos-labeled neurons); their distribution was similar to neurons labeled with Neun (B; surrounded by oval; arrows point to Neun-labeled neurons). Numerous cells on or near the ventral surface of the medulla were labeled with Fos antibodies (F and K; arrows), but comparing these sections to others immunostained with Neun (C) suggests that many of the smaller labeled profiles are not neurons. We considered only the larger profiles stained with antibodies against Fos as neurons; numerous such profiles are seen in the parapyramidal nucleus (PPy; arrows; D and K), the ventral surface of the medulla (F; arrows), and the paraolivary nucleus (POI; oval; J). Compare the distribution of these profiles to those in Neun-stained material (G and H). Injections of biotinylated dextran amine (BDA) into the ventral MDH (I, inset) resulted in numerous fibers with swellings coursing in along the caudal ventral medullary surface (I) bilaterally. These small fibers displayed numerous swellings both ipsilateral (L.1) and contralateral (L.2) to the injection. Arrows in I point to two neurons, possibly respiratory chemoreceptors, shown at higher magnification in L.1. Note that many of the fibers coursed within a gelatinous-appearing “epi-pia”, covering the neuropil (L.2). A line drawing illustrating these fibers with varicosities is shown in M. See Glossary for definitions of acronyms.

Tract Tracing Experiments

Numerous labeled fibers of small diameter emerged medially from the injection of BDA in the ventral MDH (Fig. 5I, inset); such injections were targeted in the area innervated by the central processes of the anterior ethmoidal nerve (86, 91). These small fibers were directed along the ventral surface of the medulla at the level of the caudal pole of the inferior olivary complex and lateral reticular nuclei (Fig. 5I), where they contained numerous swellings. These swellings were found both in the thickened epi-pia membrane, as well as juxtaposed to triangular-shaped neurons close to the ventral surface (Fig. 5, L.1 and L.2). The rostrocaudal length of this projection was only ∼500 μm. A line drawing on one such section is shown (Fig. 5M).

DISCUSSION

The mammalian diving response is a dramatic perturbation of normal autonomic function and may be the most powerful autonomic response known. Our laboratory has previously documented the cardiovascular dynamics of this response in the rat (92), as well as some of the neural pathways that mediate these responses (70, 72, 73, 86–88, 90, 91, 93, 94, 96–99, 130). While the homeostatic baroreceptor reflex apparently is inhibited during diving (73), less is known about the inhibition of the respiratory chemoreceptor reflex. We present data herein for the first time on activation of putative central chemoreceptors and illustrate a neural pathway that may initiate inhibition of the homeostatic chemoreceptor reflex.

Technical Considerations

Occlusion of a carotid artery with the cannula for blood sampling may have disrupted hemispheric cerebral blood flow (16) and biased our results. However, the rats recovered for 2–3 days postoperatively, and cerebral blood flow is not significantly different 24 h after carotid occlusion in normocapnic rats, but is after 15 min of hypercapnia (16). Moreover, brain stem tissues are mostly perfused by the vertebral arteries, which branch from the subclavian arteries. Several studies have shown the diving response persists after transecting the brain stem through the thalamus (22), colliculi (52, 67, 92), or pons (98), suggesting the neural circuits driving this response are intrinsic to the brain stem and were not compromised by unilateral carotid occlusion.

Approximately 2 ml of blood were withdrawn from these rats over the experimental period of 3–4 min, inducing a hypovolemia of <10% (estimating the total blood volume of our rats to be ∼24 ml). The volume withdrawn was considerably less than other studies investigating hemorrhage, where 30–40% of volume is commonly withdrawn (see Ref. 12 for references). Nevertheless, hypovolemia may have contributed to the slight increase in HR and decrease in MABP toward the end of the submersion period.

ADL.

All cells in a mammalian organism's body need oxygen to survive. Such oxygen is derived from inspired air and exchanged for carbon dioxide, the waste product of aerobic metabolism, in the lungs. Terrestrial animals mostly utilize aerobic metabolic pathways, maintaining levels of carbon dioxide, oxygen, and pH in the blood within tight limits by adjusting ventilation. The metabolism of aquatic mammals, such as seals is similar, but these animals routinely perform underwater breath holds of unusual length, denying the replenishment of oxygen for their cells. These apneic periods, combined with the cardiovascular adjustments, result in their profound diving response to underwater submersion. The massive peripheral vasoconstriction reduces or eliminates perfusion of nonessential organs, saving oxygen in the blood for the heart and brain. The heart slows considerably, reducing cardiac output and inducing profound reflex peripheral vasoconstriction to maintain central arterial pressure (54). It is thought diving mammals generally utilize these cardiovascular adjustments for maintenance of levels of gases in their blood necessary for aerobic metabolism. Indeed, the dives of aquatic mammals generally are shorter in duration than the ADL, with the animal surfacing from the water before anaerobic biochemical pathways are needed. However, prolonged underwater submersion activates anaerobic pathways, resulting in accumulations of its waste product, lactic acid (60, 62, 104). The result of prolonged underwater submersion is greatly lowered PaO2 and pH and much higher PaCO2 and lactic acid.

Blood chemistry is difficult to measure in feral underwater mammals, but, despite this, Kooyman et al. (62) first documented the blood chemistry of diving seals and coined the term “aerobic dive limit” (58, 60). This term marks the shift from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism and suggests the progressive release of lactic acid from cells. The ADL has been measured in only a few aquatic species, but has been calculated in more (60, 62, 103, 104), and to our knowledge that of terrestrial mammals has never been measured or calculated. Nevertheless, we report herein on the cardiovascular changes, blood chemistry, and activation of neurons of rats brought beyond their ADL. However, the time needed for such a transformation of metabolism in the rat may have been accomplished with <100 s of submergence herein. A detailed analysis of blood chemistry over different times is needed to define the ADL in the rat. For those studying hypoxemic tolerance of bodily tissues or regulation of tissue oxygen delivery and consumption, this rat model may circumnavigate the problems of variable depth, duration, and behavioral strategies seen in pinniped divers.

Cardiovascular consequences of prolonged underwater submersion.

There was an immediate drop of HR upon submersion of 77%, comparable to that previously reported by our laboratory in rats (92). This bradycardia lasted throughout the period of submergence, similar to that seen in aquatic animals (3, 15, 30, 59, 61). It should be noted, however, that there was a slight increase in both HR and MABP upon entering the restrictive tube, as well as numerous cardiac arrhythmias, much different than the regular cardiac rhythms seen after trained rats voluntarily dive without the tight quarters of the restraining tube (92). Such tubes usually induce restraint stress, resulting in a tachycardia, increases in arterial pressure, and arrhythmias (57, 79, 116, 117). The sympathetic input from this stressor, combined with massive cardiac parasympathetic outflow of the diving response, may result in the numerous arrhythmias seen in the present study. Some of the bradycardia from these restrained rats also may be the result of extreme fear, which also induces significant bradycardia and increases in ABP (11, 36, 119–121, 131). However, the bradycardia noted herein was locked tightly to the time submerged, and we speculate it was the result of underwater submersion rather than fear.

MABP rose early in the submersion period, similar to our laboratory's previous observations (92). However, it fell precipitously as normal blood gases eroded, before it again stabilized. The etiology of this drop in arterial pressure is unknown, but could have been the result of either a fall in peripheral resistance or of increased vasoconstriction near the opening of the cannula of the biotelemetric transmitter measuring ABP.

Changes in blood chemistry.

It is well known that hypercapnia, hypoxia, and acidity induce increases in ventilation. The acute hypercapnia and hypoxia seen in the submerged rats in the present study was dramatic: PaCO2 rose to 79.2 Torr in one case, and PaO2 dropped to 15.7 Torr in another. Studies have shown that small increases in PaCO2 induce vigorous ventilation (55, 80), while decreases in PaO2 (105) and pH also increase ventilation. pH dropped from 7.51 in control periods to 7.18 at the end of submersion, while BE went from 0.86 to −4.3 mmol/l in the present study. Both pH and BE, however, continued to drop after emersion from the water to 6.99 and −18.24 mmol/l, respectively. Documenting the progressive changes of blood chemistry in diving aquatic mammals has been relatively rare due to the difficulty of such measurements. Nevertheless, initial studies (43, 60, 62, 107) showed changes in several metabolites in blood, but measurements of tensions of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and pH are difficult to compare to results seen in the rats herein. Moreover, measurements of variables in blood chemistry of naturally diving feral mammals is biased by parameters such as compression hyperoxia, when the animals dive to great underwater depths, dive duration, or the “intent” of the dive (e.g., foraging or drift dives). Mean PaO2 and SaO2 values after submersion in the present study were 21.8 ± 2.2 Torr and 17.6 ± 2.8%, respectively, which are comparable to the minimum means of 22 ± 15 Torr and 28 ± 25.5% seen in diving elephant seals (75). However, the caveats in such comparisons are that the elephant seals dove underwater for variable times to different depths, they apparently never reached their ADL, and oxygen saturations were calculated at pHs of either 7.4 or 7.3, depending on length of the dive.

The arterial pH of the submerged rats was 7.18 ± 0.02 at the end of submersion, but continued falling to 6.99 ± 0.02 2 min later. These measurements of acid-base balance dropped after emersion, creating a combined respiratory and metabolic acidosis, probably due to a massive release of lactate produced by anaerobic metabolism during the later stages of submersion and subsequent to release of the sympathovasoconstriction. Nevertheless, the rats in the present study did not breathe while underwater, despite all of these stimulants. Studies of cellular or tissue metabolism in extreme hypoxia, hypercapnia, and pH states may find this rat model advantageous, since the study is easily controlled in the laboratory.

Spleens store numerous red blood cells and thus act as a reservoir of bound oxygen. Indeed, the spleens of naturally diving mammals are proportionately larger than those of terrestrial animals. Splenic contraction is prominent during dives in many species (10, 31, 113, 123, 124), prompting suggestions that such contractions liberate more Hb-bound oxygen into the circulation and thus curb the oxygen hunger of cells during underwater submersion. There were variable fluxes in hematocrit of the submerged rats in the present study, but none was significantly different from control values. Moreover, the Hb concentration did not change from baseline, suggesting that rats' spleens either are not large reservoirs or fail to contract during underwater submersion.

Fos studies.

The principal chemoreceptors regulating respiration are found in the carotid body and the central nervous system. It is thought that glomus cells in the peripheral carotid body mainly modulate ventilation to hypoxic conditions (40, 63, 106), while central chemoreceptors induce ventilation in response to hypercarbic and acidotic conditions (32, 81). The carotid sinus nerve carries impulses monitoring changes in blood gases and pH and has its major projection into the caudal NTS of the medulla (1, 34, 50, 95). Physiological and Fos studies show that neurons in the commissural subnucleus of the NTS are especially sensitive to hypoxia in the peripheral blood (4, 42, 48, 100, 101, 118). It is thus of interest that considerably more neurons were labeled in subnuclei of the NTS near the calamus scriptorius in the present study vs. those labeled in voluntary diving behavior (90). The average time of submergence of voluntary dives (∼20 s) seen in our laboratory's previous studies (72, 90, 92) coincides with periods in which blood gases had changed little (Fig. 2), but the more prolonged dives reported herein should have vigorously stimulated peripheral chemoreceptors and induced formation of the Fos protein in the caudal NTS.

Cells on the ventral surface of the medulla originally were proposed as the locus of central chemoreceptors, whose activation induced increases in ventilation (76, 77, 114). This view has been expanded widely to include neurons in the raphe (83, 109, 110), the LC (19, 85), the NTS (19, 20), parapyramidal/paraolivary areas (2, 5, 78, 108), the Rtz (32, 44, 45, 80, 82), and many other neurons in between (13, 56, 80). Although these neurons are all responsive to chemical stimuli, it is uncertain if all directly influence the respiratory network (46, 111).

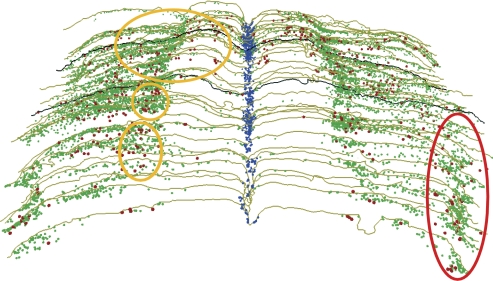

We observed the thickened glia on the ventral surface of the medulla described previously (84, 125, 126) and noted that nuclei immunostained for Fos were especially aggregated near the exits of the hypoglossal nerve medially (included in yellow ovals, Fig. 6), but also near the ventrolateral exit of the glossopharyngeal/vagus nerves (red oval in Fig. 6). Numerous blood vessels also penetrated the pial surface ventrolaterally near the penetration of the IX-X cranial nerves, as well as along the midline raphe, where numerous Fos-labeled nuclei were located (blue markers in Fig. 6). The nuclei immunostained for Fos protein in the superficial ventral medulla after prolonged submersion were of two sizes: the smaller nuclei mostly were embedded in the epi-pia layer, while the larger nuclei compared favorably qualitatively, quantitatively, and in location with the superficial neurons noted in our Neun immunostained material. While the cells with small nuclei obviously were activated by prolonged underwater submersion and are potential chemoreceptors, they apparently are not neurons and thus potentially peripheral to the respiratory network. These “general chemoreceptors” in their thick pia matrix may, however, still be important in modulating respiratory output (49). The fact that numerous swellings from fibers labeled after BDA injections of the ventral MDH were found in this thickened epi-pia layer suggests that these fibers may modulate the activity of these putative chemoreceptors and inhibit ventilation. The carotid body similarly is composed of numerous glomus cells, which sense changes in blood chemistry, yet are not considered neurons. However, glomus cells depolarize primary afferent fibers in the carotid sinus nerve. It is possible that these smaller cells in the epi-pia on the ventral surface of the medulla perform similar duties. Moreover, presumptive neurons, possibly respiratory chemoreceptors (41), near the ventral surface, were juxtaposed by swellings from the MDH injections. We suggest these neurons directly modulate the respiratory network. In this regard, it is of interest that application of a local anesthetic to similar areas in the cat induces an apnea (125–127).

Fig. 6.

A montage of serial sections through the medulla from rostral (top) to caudal (bottom) showing the numerous cells labeled with Fos on its ventral surface after prolonged underwater submersion. Neurons in both the raphe nuclei (blue squares) and cells on the ventral surface of the medulla (green dots and red asterisks) are suggested to be putative chemoreceptors. While the present study cannot determine whether any of these profiles represent chemoreceptors, we did notice that the Fos-immunolabeled cells on the ventral surface were of two sizes. Thus cells labeled with green dots on the medulla's ventral surface represent the smaller immunolabeled profiles, while those marked by red asterisks denote large stained profiles seen in our material. The red asterisks also were similar in size, number, and distribution to neurons stained with Neun, implicating them as neurons, whereas the green dots were embedded in a thickened epi-pia layer (see text for details). The yellow ovals on the left side of the figure represent the original outlines proposed by Mitchell, Loeschcke, and Schläfke (76, 77, 114; see text), which generally include the exit of the hypoglossal nerve, while the red oval marks an abundance of such profiles near the exit of the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. The most rostral black outline represents the level of the caudal facial nucleus, while the more caudal black line represents the level of the obex.

Neurons in many brain stem nuclei were labeled with Fos protein herein, including the CPA, periobex NTS, MDH, RVLM, LC, SSn, lateral medulla, and A5 area. While many of these also may influence the respiratory network, we speculate most may be more important in the sensory and cardiovascular pathways driving the diving response (70, 72, 73, 86, 87, 90–94, 96, 97, 130). Moreover, these same nuclei were labeled after voluntary diving for shorter periods (90).

Several studies have described gap junctions in central chemoreceptors (17, 122). Such coupling provides fast transmission of a message but provides little access to modulation. It also suggests a minimal synaptic input may influence a large matrix of cells. Thus it is significant that the projection described herein is only to the most caudal aspect of the ventral medulla. It also is significant that neurons coupled by gap junctions are more prominent in fetal and neonatal brains (18, 51). An inhibitory signal from the MDH to such caudal medullary chemoreceptors potentially could inhibit the chemoreceptor reflex in diving mammals and prevent them from breathing.

The diving response is a physiological stressor to voluntary diving rats, but rats dunked underwater involuntarily also may feel anxiety stress (9, 92). Although these neuroanatomic studies cannot describe the function of any of these neurons labeled with Fos after prolonged submersion, there was a dearth of labeled nuclei in brain stem areas where respiratory-related neurons are described to lie. However, numerous neurons in all nuclei where presumptive chemoreceptors are found were reactive to Fos antibodies in the rats exceeding their ADL described herein. We monitored the blood chemistry during these prolonged dives and show that the gross alterations of it should have activated numerous respiratory chemoreceptors. Nevertheless, the rats neither gasped nor breathed.

Summary

There has been much debate concerning the stimulus, location, and projections of respiratory chemoreceptors. The incongruity of ideas no doubt rests in part on the multiple approaches used to analyze the putative receptors and a clear interpretation of how the respiratory network works. We have shown herein that despite radical changes in arterial levels of partial pressures of oxygen and carbon dioxide, as well as significant changes in pH, the rats did not breathe while underwater. Immunohistochemistry against Fos suggests numerous neurons in the brain were activated, including those in areas like the commissural subnucleus of the NTS, the ventral surface of the medulla, the midline raphe, and the PPy and Rtz. All of these areas are known loci where either peripheral chemoreceptors project or central chemoreceptors lie.

The mammalian diving response is a complex configuration of numerous independent reflexes regulating respiration, HR, and blood pressure and initiated by a somatic stimulus. Aquatic mammals develop more intense diving responses as they mature, providing credence to such statements as “practice makes perfect” or “use it or lose it.” Humans are mammals and also possess a diving response (31, 33, 35, 113), albeit the response in adults is not as profound as in aquatic mammals. However, the diving response is brisk in human neonates (38). Numerous incidents of “cold-water drowning” have been documented in humans (37, 39, 47, 129), where humans lie submerged underwater for extended periods, yet recover with minimal functional loss. We speculate this is similar to our rats brought past their ADL. We feel, however, that the cardiovascular responses occur merely to buffer the deficit of breathing. Our data also support the hypothesis that the diving response, or similar cardiorespiratory responses elicited by nasal CO2 (130), could be a major factor dooming children in sudden infant death syndrome. Nevertheless, our data give new emphasis to the diving response as “the master switch of life” (115). These data support our contention that the diving response is the most powerful autonomic response known.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL64772 to W. M. Panneton and monies from the Saint Louis University School of Medicine.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Le for help in early phases of the analysis of this data.

Glossary

- A5

Noradrenergic cell group in ventrolateral pons

- ABP

Arterial blood pressure

- Amb

Nucleus ambiguus

- bc

Brachium conjuctivum

- BE

Base excess

- CPA

Caudal pressor area of the caudal medulla

- Cu

Cuneate nucleus

- E5

Ectotrigeminal nucleus

- GiA

Gigantocellular reticular nucleus, pars alpha

- Gr

Gracile nucleus

- Hb

Hemoglobin

- HR

Heart rate

- IO

Inferior olivary nucleus

- LC

Nucleus locus coeruleus

- LRt

Lateral reticular nucleus

- LRtPC

Lateral reticular nucleus, pars parvocellularis

- MABP

Mean arterial blood pressure

- MDH

Medullary dorsal horn

- m5

Trigeminal motor root

- Mo5

Motor trigeminal nucleus

- MVe

Medial vestibular nucleus

- Pa5

Paratrigeminal nucleus

- PaCO2

Partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide

- PaO2

Partial pressure of arterial oxygen

- PDTg

Posterodorsal tegmental nucleus

- POI

Paraolivary nucleus

- PPy

Parapyramidal nucleus

- Pr5

Principal trigeminal nucleus

- py

Pyramidal tract

- RtTg

Reticulotegmental nucleus of the pons

- Rtz

Retrotrapezoid nucleus

- RVLM

Pressor area of the rostral medulla

- SaO2

Arterial oxygen saturation

- sol

Tractus solitarii

- Sol, NTS

Nucleus tractus solitarii

- SO

Superior olivary nucleus

- sp5

Spinal tract of the trigeminal nerve

- Sp5I

Nucleus of the spinal tract of the trigeminal nerve, interpolar part

- Sp5O

Nucleus of the spinal tract of the trigeminal nerve, oral part

- SpVe

Spinal vestibular nucleus

- SSn

Superior salivary nucleus

- Tz

Trapezoid nucleus

- VCn

Ventral cochlear nucleus

- 7

Facial motor nucleus

- 12

Hypoglossal motor nucleus

- 12n

Hypoglossal nerve root

REFERENCES

- 1. Berger AJ. Distribution of carotid sinus nerve afferent fibers to solitary tract nuclei of the cat using transganglionic transport of horseradish peroxidase. Neurosci Lett 14: 153–158, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berquin P, Bodineau L, Gros F, Larnicol N. Brainstem and hypothalamic areas involved in respiratory chemoreflexes: a Fos study in adult rats. Brain Res 857: 30–40, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blix AS, Folkow B. Cardiovascular adjustments to diving in mammals and birds. In: Handbook of Physiology. The Cardiovascular System. Peripheral Circulation and Organ Blood Flow. Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Soc., 1983, sect. 2, vol. III, pt. 2, chapt. 25, p. 917–945 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bodineau L, Larnicol N. Brainstem and hypothalamic areas activated by tissue hypoxia: Fos-like immunoreactivity induced by carbon monoxide inhalation in the rat. Neuroscience 108: 643–653, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bradley SR, Pieribone VA, Wang WG, Severson CA, Jacobs RA, Richerson GB. Chemosensitive serotonergic neurons are closely associated with large medullary arteries. Nat Neurosci 5: 401–402, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bullitt E. Expression of C-fos-like protein as a marker for neuronal activity following noxious stimulation in the rat. J Comp Neurol 296: 517–530, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Butler PJ, Jones DR. The comparative physiology of diving in vertebrates. Adv Comp Physiol Biochem 8: 179–364, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Butler PJ, Jones DR. Physiology of diving of birds and mammals. Physiol Rev 77: 837–899, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Byku M, Gan Q, Panneton WM. A physiological and neuroanatomical comparison of rats after either voluntary or forced dives (Abstract). FASEB J 18: A1102, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cabanac A, Folkow LP, Blix AS. Volume capacity and contraction control of the seal spleen. J Appl Physiol 82: 1989–1994, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carrive P. Conditioned fear to environmental context: cardiovascular and behavioral components in the rat. Brain Res 858: 440–445, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chan RKW, Sawchenko PE. Spatially and temporally differentiated patterns of c-fos expression in brainstem catecholaminergic cell groups induced by cardiovascular challenges in the rat. J Comp Neurol 348: 433–460, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Coates EL, Li A, Nattie EE. Widespread sites of brain stem ventilatory chemoreceptors. J Appl Physiol 75: 5–14, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davis RW, Polasek L, Watson R, Fuson A, Williams TM, Kanatous SB. The diving paradox: new insights into the role of the dive response in air-breathing vertebrates. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 138: 263–268, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Burgh Daly M. Breath-hold diving: mechanisms of cardiovascular adjustments in the mammal. In: Recent Advance in Physiology, edited by Baker PF. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1984, p. 201–245 [Google Scholar]

- 16. De Lay G, Nshimyumuremyi JB, Leusen I. Hemisheric blood flow in the rat after unilateral common carotid occlusion: evolution with time. Stroke 16: 69–73, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dean JB, Ballantyne D, Cardone DL, Erlichman JS, Solomon IC. Role of gap junctions in CO2 chemoreception and respiratory control. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 283: L665–L670, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dean JB, Huang RQ, Erlichman JS, Southard TL, Hellard DT. Cell-cell coupling occurs in dorsal medullary neurons after minimizing anatomical-coupling artifacts. Neuroscience 80: 21–40, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dean JB, Kinkade EA, Putnam RW. Cell-cell coupling in CO2/H+-excited neurons in brainstem slices. Respir Physiol 129: 83–100, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dean JB, Lawing WL, Millhorn DE. CO2 decreases membrane conductance and depolarizes neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius. Exp Brain Res 76: 656–661, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dragunow M, Faull R. The use of c-fos as a metabolic marker in neuronal pathway tracing. J Neurosci Methods 29: 261–265, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Drummond PC, Jones DR. The initiation and maintenance of bradycardia in a diving mammal, the muskrat, Ondatra zibethica. J Physiol 290: 253–271, 1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Duffin J. Role of acid-base balance in the chemoreflex control of breathing. J Appl Physiol 99: 2255–2265, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dutschmann M, Herbert H. The Kölliker-Fuse nucleus mediates the trigeminally induced apnoea in the rat. Neuroreport 7: 1432–1436, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dutschmann M, Herbert H. Fos expression in the rat parabrachial and Kölliker-Fuse nuclei after electrical stimulation of the trigeminal ethmoidal nerve and water stimulation of the nasal mucosa. Exp Brain Res 117: 97–110, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dutschmann M, Herbert H. The medial nucleus of the solitary tract mediates the trigeminally evoked pressor response. Neuroreport 9: 1053–1057, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dutschmann M, Herbert H. Pontine cholinergic mechanisms enhance trigeminally evoked respiratory suppression in the anesthetized rat. J Appl Physiol 87: 1059–1065, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dutschmann M, Paton JFR. Influence of nasotrigeminal afferents on medullary respiratory neurones and upper airway patency in the rat. Pflügers Arch 444: 227–235, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elsner R, Franklin DL, Van Citters RL, Kenney DW. Cardiovascular defense against asphyxia. Science 153: 941–949, 1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Elsner R, Gooden B. Diving and asphyxia: a comparative study of animals and man. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983, p. 1–168 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Espersen K, Frandsen H, Lorentzen T, Kanstrup IL, Christensen NJ. The human spleen as an erythrocyte reservoir in diving-related interventions. J Appl Physiol 92: 2071–2079, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Feldman JL, Mitchell GS, Nattie EE. Breathing: rhythmicity, plasticity, chemosensitivity. Annu Rev Neurosci 26: 239–266, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ferretti G. Extreme human breath-hold diving. Eur J Appl Physiol 84: 254–271, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Finley JCW, Katz DM. The central organization of carotid body afferent projections to the brainstem of the rat. Brain Res 572: 108–116, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Foster GE, Sheel AW. The human diving response, its function, and its control. Scand J Med Sci Sports 15: 3–12, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gabrielsen G, Kanwisher J, Steen JB. “Emotional” bradycardia: a telemetry study on incubating willow grouse (Lagopus laopus). Acta Physiol Scand 100: 255–257, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Giesbrecht GG. Cold stress, near drowning and accidental hypothermia: a review. Aviat Space Environ Med 71: 733–752, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Goksör E, Rosengren L, Wennergren G. Bradycardic response during submersion in infant swimming. Acta Paediatr 91: 307–312, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Golden FS, Tipton MJ, Scott RC. Immersion, near-drowning and drowning. Br J Anaesth 79: 214–225, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. González C, Almaraz L, Obeso A, Rigual R. Oxygen and acid chemoreception in the carotid body chemoreceptors. Trends Neurosci 15: 146–153, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gourine AV. On the peripheral and central chemoreception and control of breathing: an emerging role of ATP. J Physiol 568: 715–724, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Greenberg HE, Sica AL, Scharf SM, Ruggiero DA. Expression of c-fos in the rat brainstem after chronic intermittent hypoxia. Brain Res 816: 638–645, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Guppy M, Hill RD, Schneider RC, Qvist J, Liggins GC, Sapol WM, Hochachka PW. Microcomputer-assisted metabolic studies of voluntary diving of Weddell seals. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 250: R175–R187, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Guyenet PG. The 2008 Carl Ludwig Lecture: retrotrapezoid nucleus, CO2 homeostasis, and breathing automaticity. J Appl Physiol 105: 404–416, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Guyenet PG, Bayliss DA, Stornetta RL, Fortuna MG, Abbott SBG, DePuy SD. Retrotrapezoid nucleus, respiratory chemosensitivity and breathing automaticity. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 168: 59–68, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Bayliss DA. Retrotrapezoid nucleus and central chemoreception. J Physiol 586: 2043–2048, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hayward JS, Hay C, Matthews BR, Overweel CH, Radford DD. Temperature effect on the human dive response in relation to cold water near-drowning. J Appl Physiol 56: 202–206, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hirooka Y, Polson JW, Potts PD, Dampney RAL. Hypoxia-induced Fos expression in neurons projecting to the pressor region in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Neuroscience 80: 1209–1224, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Holleran J, Babbie M, Erlichman JS. Ventilatory effects of impaired glial function in a brain stem chemoreceptor region in the conscious rat. J Appl Physiol 90: 1539–1547, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Housley GD, Martin Body RL, Dawson NJ, Sinclair JD. Brain stem projections of the glossopharyngeal nerve and its carotid sinus branch in the rat. Neuroscience 22: 237–250, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Huang RQ, Erlichman JS, Dean JB. Cell-cell coupling between CO2-excited neurons in the dorsal medulla oblingata. Neuroscience 80: 41–57, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Huxley FM. On the nature of apnoea in the duck in diving. I. The nature of submersion apnoea. J Physiol 6: 147–157, 1913 [Google Scholar]

- 53. Irving L. Respiration in diving mammals. Physiol Rev 19: 112–134, 1939 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Irving L, Scholander PF, Grinnell SW. The regulation of arterial blood pressure in the seal during diving. Am J Physiol 135: 557–566, 1942 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Iscoe S, Beaton M, Duffin J. Chemoreflex thresholds to CO2 in decerebrate cats. Respir Physiol 113: 1–10, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kawai A, Ballentyne D, Mückenhoff K, Scheid P. Chemosensitve medullary neurones in the brainstem-spinal cord preparation of the neonatal rat. J Physiol 492: 277–292, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kawakami Y, Natelson BH, Dubois AB. Cardiovascular effects of face immersion and factors affecting diving reflex in man. J Appl Physiol 23: 964–970, 1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kooyman GL. Physiology without restraint in diving mammals. Marine Mammal Sci 1: 166–178, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kooyman GL, Castellini MA, Davis RW. Physiology of diving in marine mammals. Annu Rev Physiol 43: 343–356, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kooyman GL, Castellini MA, Davis RW, Maue RA. Aerobic dive limits in immature Weddell seals. J Comp Physiol 151: 171–174, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kooyman GL, Ponganis PJ. The physiological basis of diving to depth: birds and mammals. Annu Rev Physiol 60: 19–32, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kooyman GL, Wahrenbrock EA, Castellini MA, Davis RW, Sinnett EE. Aerobic and anaerobic metabolism during diving in Weddell seals: evidence of preferred pathways from blood chemistry and behavior. J Comp Physiol 138: 335–346, 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lahiri S, Rozanov C, Roy A, Storey B, Buerk DG. Regulation of oxygen sensing in peripheral arterial chemoreceptors. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 33: 755–774, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Leiter JC, Böhm I. Mechanisms of pathogenesis in the sudden infant death syndrome. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 159: 127–138, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lin YC. Autonomic nervous control of cardiovascular response during diving in the rat. Am J Physiol 227: 601–605, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lin YC, Baker DG. Cardiac output and its distribution during diving in the rat. Am J Physiol 228: 733–737, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Martner J, Wadenvik H, Lisander B. Apnoea and bradycardia from submersion in “chronically” decerebrated cats. Acta Physiol Scand 101: 476–480, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. McCulloch PF. Activation of the trigeminal medullary dorsal horn during voluntary diving in rats. Brain Res 1051: 194–198, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. McCulloch PF, Dinovo KM, Connolly TM. The cardiovascular and endocrine responses to voluntary and forced diving in trained and untrained rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298: R224–R234, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. McCulloch PF, Faber KM, Panneton WM. Electrical stimulation of the anterior ethmoidal nerve produces the diving response. Brain Res 830: 24–31, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. McCulloch PF, Ollenberger GP, Bekar LK, West NH. Trigeminal and chemoreceptor contributions to bradycardia during voluntary dives in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 273: R814–R822, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. McCulloch PF, Panneton WM. Activation of brainstem catecholaminergic neurons during voluntary diving in rats. Brain Res 984: 42–53, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. McCulloch PF, Panneton WM, Guyenet PG. The rostral ventrolateral medulla mediates the sympathoactivation produced by chemical stimulation of the nasal mucosa. J Physiol 516: 471–484, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. McCulloch PF, Paterson IA, West NH. An intact glutamatergic trigeminal pathway is essential for the cardiac response to simulated diving. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 269: R669–R677, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Meir JU, Champagne CD, Costa DP, Williams CL, Ponganis PJ. Extreme hypoxemic tolerance and blood oxygen depletion in diving elephant seals. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R927–R939, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Mitchell RA, Loeschcke HH. Respiratory responses mediated through superficial chemosensitive areas on the medulla. J Appl Physiol 18: 523–533, 1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mitchell RA, Loeschcke HH, Severinghaus JW, Richardson BW, Massion WH. Regions of respiratory chemosensitivity on the surface of the medulla. Ann NY Acad Sci 109: 661–681, 1963 [Google Scholar]

- 78. Miura M, Okada J, Kanazawa M. Topology and immunohistochemistry of proton-sensitive neurons in the ventral medullary surface of rats. Brain Res 780: 34–45, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Natelson BH, Cagin NA. Stress-induced ventricular arrhythmias. Psychosom Med 41: 259–262, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Nattie E. CO2, brainstem chemoreceptors and breathing. Prog Neurobiol 59: 299–331, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Nattie EE. Central chemosensitivity, sleep, wakefulness. Respir Physiol 129: 257–268, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Nattie EE, Gdovin M, Li A. Retrotrapezoid nucleus glutamate receptors: control of CO2-sensitive phrenic and sympathetic output. J Appl Physiol 74: 2958–2968, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nattie EE, Li AH. CO2 dialysis in the medullary raphe of the rat increases ventilation in sleep. J Appl Physiol 90: 1247–1257, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Okada Y, Chen ZB, Kuwana S. Cytoarchitecture of central chemoreceptors in the mammalian ventral medulla. Respir Physiol 129: 13–23, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Oyamada Y, Ballantyne D, Mückenhoff K, Scheid P, Ballantyne D. Respiration modulated membrane potential and chemosensitivity of locus coeruleus neurones in the in vitro brainstem-spinal cord of the neonatal rat. J Physiol 513: 381–398, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Panneton WM. Primary afferent projections from the upper respiratory tract in the muskrat. J Comp Neurol 308: 51–65, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Panneton WM. Trigeminal mediation of the diving response in the muskrat. Brain Res 560: 321–325, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Panneton WM, Anch MA, Gan Q. Topography of preganglionic parasympathetic cardiac motor neurons labeled after underwater submersion (Abstract). FASEB J 21: 952.6, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 89. Panneton WM, Gan Q. Cardiovascular changes induced in freely diving, swimming and nasally stimulated rats (Abstract). Neurosci Abstr 28: 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 90. Panneton WM, Gan Q, Clerc P, Palkert J, Kasinadhuni P, Lemon C. Activation of brainstem neurons by underwater submersion (Abstract). Neurosci Abstr 34: 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 91. Panneton WM, Gan Q, Juric R. Brainstem projections from recipient zones of the anterior ethmoidal nerve in the medullary dorsal horn. Neuroscience 141: 889–906, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Panneton WM, Gan Q, Juric R. The rat: a laboratory model for studies of the diving response. J Appl Physiol 108: 811–820, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Panneton WM, Gan Q, Sun W. Pressor responses to nasal stimulation are unaltered after disrupting the caudalmost ventrolateral medulla. Auton Neurosci 144: 13–21, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Panneton WM, Johnson SN, Christensen ND. Trigeminal projections to the peribrachial region in the muskrat. Neuroscience 58: 605–625, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Panneton WM, Loewy AD. Projections of the carotid sinus nerve to the nucleus of the solitary tract in the cat. Brain Res 191: 239–244, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Panneton WM, McCulloch PF, Sun W. Trigemino-autonomic connections in the muskrat: the neural substrate for the diving response. Brain Res 874: 48–65, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Panneton WM, McCulloch PF, Tan Y, Tan YX, Yavari P. Brainstem origin of preganglionic cardiac motoneurons in the muskrat. Brain Res 738: 342–346, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Panneton WM, Sun W. Cardiorespiratory changes after nasal stimulation persist after partial pontine transection (Abstract). Neurosci Abstr 27: 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 99. Panneton WM, Yavari P. A medullary dorsal horn relay for the cardiorespiratory responses evoked by stimulation of the nasal mucosa in the muskrat, Ondatra zibethicus: evidence for excitatory amino acid transmission. Brain Res 691: 37–45, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Paton JFR, De Paula PM, Spyer KM, Machado BH, Boscan P. Sensory afferent selective role of P2 receptors in the nucleus tractus solitarii for mediating the cardiac component of the peripheral chemoreceptor reflex in rats. J Physiol 543: 995–1005, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Paton JFR, Deuchars J, Li YW, Kasparov S. Properties of solitary tract neurones responding to peripheral arterial chemoreceptors. Neuroscience 105: 231–248, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego, CA: Academic, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 103. Ponganis PJ, Kooyman GL, Starke LN, Kooyman CA, Kooyman TG. Post-dive blood lactate concentration in emperor penguins, Apenodytes forsteri. J Exp Biol 200: 1623–1626, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Ponganis PJ, Kooyman GL, Winter LM, Starke LN. Heart rate and plasma lactate responses during submerged swimming and trained diving in California sea lions, Zalophus californianus. J Comp Physiol [B] 167: 9–16, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Powell FL, Milsom WK, Mitchell GS. Time domains of the hypoxic ventilatory response. Respir Physiol 112: 123–134, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Prabhakar NR. Oxygen sensing by the carotid body chemoreceptors. J Appl Physiol 88: 2287–2295, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Qvist J, Hill RD, Schneider RC, Falke KJ, Liggins GC, Guppy M, Elliot RL, Hochachka PW, Zapol WM. Hemoglobin concentrations and blood gas tensions of free-diving Weddell seals. J Appl Physiol 61: 1560–1569, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Ribas-Salgueiro JL, Gaytan SP, Crego R, Pasaro R, Ribas J. Highly H+-sensitive neurons in the caudal ventrolateral medulla of the rat. J Physiol 549: 181–194, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Richerson GB. Response to CO2 of neurons in the rostral ventral medulla in vitro. J Neurophysiol 73: 933–944, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Richerson GB. Serotonergic neurons as carbon dioxide sensors that maintain pH homeostasis. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 449–461, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Richerson GB, Wang W, Hodges MR, Dohle CI, Diez-Sampedro A. Homing in on the specific phenotype(s) of central respiratory chemoreceptors. Exp Physiol 90: 259–266, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Rozloznik M, Paton JFR, Dutschmann M. Repetitive paired stimulation of nasotrigeminal and peripheral chemoreceptor afferents cause progressive potentiation of the diving bradycardia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R80–R87, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Schagatay E, Andersson JP, Nielsen B. Hematological response and diving response during apnea and apnea with face immersion. Eur J Appl Physiol 101: 125–132, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Schläfke ME. Central chemosensitivity: a respiratory drive. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 90: 171–172, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Scholander PF. The master switch of life. Sci Am 209: 92–106, 1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Sgoifo A, De Boer SF, WestenBroek C, Maes FW, Beldhuis H, Suzuki T, Koolhaus JM. Incidence of arrhythmias and heart rate variability in wild-type rats exposed to social stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 273: H1754–H1760, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Sgoifo A, Koolhaas JM, Musso E, De Boer SF. Different sympathovagal modulation of heart rate during social and nonsocial stress episodes in wild-type rats. Physiol Behav 67: 733–738, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Sica AL, Gootman PM, Ruggiero DA. CO2-induced expression of c-fos in the nucleus of the solitary tract and the area postrema of developing swine. Brain Res 837: 106–116, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Smith EN, Johnson C, Martin KJ. Fear bradycardia in captive eastern chipmunk, Tamias striatus. Comp Biochem Physiol 70: 529–532, 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 120. Smith NE, Tobey EW. Heart rate response to forced and voluntary diving in swamp rabbits, Sylvilagus aquaticus. Physiol Zool 56: 632–638, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 121. Smith NE, Woodruff RA. Fear bradycardia in free ranging woodchucks, Marmota monax. J Mammal 61: 750–753, 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 122. Solomon IC, Halat TJ, El-Maghrabi MR, O'Neal MH., III Localization of connexin26 and connexin32 in putative CO2-chemosensitive brainstem regions in rat. Respir Physiol 129: 101–121, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Stephenson R. Physiological control of diving behaviour in the Weddell seal, Leptonychotes weddelli: a model based on cardiorespiratory control theory. J Exp Biol 208: 1971–1991, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Thornton SJ, Spielman DM, Pelc NJ, Block WF, Crocker DE, Costa DP, LeBoeuf BJ, Hochachka PW. Effects of forced diving on the spleen and hepatic sinus in northern elephant seal pups. Proc Natl Acad Sci 98: 9413–9418, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Trouth CO, Loeschcke HH, Berndt J. Histological structures in the chemosensitive regions on the ventral surface of the cat's medulla oblongata. Pflügers Arch 339: 171–183, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Trouth CO, Odek Ogunde M, Holloway JA. Morphological observations on superficial medullary CO2-chemosensitive areas. Brain Res 246: 35–45, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Trouth CO, Patrickson JW, Holloway JA, Wright LE. Neurophysiological studies on superficial medullary chemosensitive area for respiration. Brain Res 246: 47–56, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Williams PL, Warwick R. Gray's Anatomy. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 129. Xu XJ, Tikuisis P, Giesbrecht G. A mathematical model for human brain cooling during cold-water near-drowning. J Appl Physiol 86: 265–272, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Yavari P, McCulloch PF, Panneton WM. Trigeminally-mediated alteration of cardiorespiratory rhythms during nasal application of carbon dioxide in the rat. J Auton Nerv Syst 61: 195–200, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Zhang WN, Murphy CA, Feldon J. Behavioural and cardiovascular responses during latent inhibition of conditioned fear: measurement by telemetry and conditioned freezing. Behav Brain Res 154: 199–209, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]