Abstract

From March 1980 to July 1987, 1000 patients with various end-stage liver diseases received orthotopic liver transplants. Of the 7000 patients, three hundred two had definite histories of bleeding from esophageal varices before transplantation. There were 287 patients with nonalcoholic liver diseases and 15 patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. All patients had very poor liver function, which was the main indication for liver transplantation. One- through 5-year actuarial survival rates of the 302 patients were 79%, 74%, 71%, 71%, and 71%, respectively. These survival rates are far better than those obtained with other available modes of treatment for bleeding varices when liver disease is advanced. Long-term sclerotherapy is the treatment of primary choice for bleeding varices. Patients in whom sclerotherapy fails should be considered for liver transplantation unless clear contraindications exist.

Massive hemorrhage from esophageal varices is the most devastating complication of portal hypertension in advanced cirrhosis. Several types of portasystemic shunt operations, portoazygous devascularization (non-shunt operation), and endoscopic sclerotherapy have established their own roles, but they all have certain major limitations, particularly when the liver disease is far advanced. Portasystemic shunt is the most effective way to control bleeding from esophageal varices, but it is plagued by a high incidence of hepatic encephalopathy and progressive hepatic failure after the shunt. Although they do not alter hepatic circulation, non-shunt operations and sclerotherapy have high incidences of recurrent bleeding.

Liver transplantation has long been, at least in theory, the most logical treatment for bleeding esophageal varices in patients with far-advanced liver disease. As the results of liver transplantation have significantly improved in recent years, the role of this procedure in the treatment of bleeding esophageal varices should be closely examined.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

From March 1980 to July 1987, 1000 patients with various liver diseases received orthotopic liver transplants at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center (in 1980), the University Health Center of Pittsburgh (since 1981), and the Pittsburgh-affiliated Baylor University Medical Center at Dallas (since 1985). Basic immunosuppressive therapy consisted of cyclosporine and corticosteroids, and azathioprine and monoclonal anti-T-lymphocyte antibody (OKT-3) were added to the basic immunosuppression when needed. Of the 1000 consecutive liver recipients, 666 were adults of 18 years or older and 334 were children younger than 18 years. The liver diseases of adult recipients as well as the numbers of patients with each disease are listed in Table I; the same data for pediatric recipients are listed in Table II. The three most common liver diseases among adult recipients were (1) postnecrotic cirrhosis (including chronic active hepatitis and cryptogenic cirrhosis), (2) primary biliary cirrhosis, and (3) primary sclerosing cholangitis. The most common diagnoses in pediatric recipients were (1) biliary atresia (including extrahepatic and intrahepatic type, biliary hypoplasia, and Alagille’s syndrome), (2) liver-based inborn metabolic errors (alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency disease, Wilson’s disease, tyrosinemia, and others), and (3) postnecrotic cirrhosis.

Table I.

Liver diseases of adult recipients

| Disease | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| 1. Cirrhosis (postnecrotic, cryptogenic, alcoholic) | 279 |

| Postnecrotic and cryptogenic(HBsAg positive | 237 |

| 36 | |

| Alcoholic | 41 |

| 2. Primary biliary cirrhosis | 166 |

| 3. Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 82 |

| Associated with bile duct cancer | 88 |

| 4. Liver-based inborn metabolic errors (alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson’s, etc) | 35 |

| 5. Primary hepatic malignancy | 33 |

| 6. Fulminant hepatic failure | 25 |

| 7. Secondary biliary cirrhosis | 13 |

| 8. Budd-Chiari syndrome | 13 |

| 9. Secondary hepatic malignancy | 7 |

| 10. Bile duct cancer without sclerosing cholangitis | 2 |

| 11. Others | 11 |

| Total | 666 |

Table II.

Liver diseases of pediatric recipients

| Disease | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| 1. Biliary atresia | 179 |

| 2. Liver-based inborn metabolic errors (alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson’s, etc.). | 63 |

| 3. Cirrhosis (postnecrotic, cryptogenic) | 40 |

| 4. Familial cholestatic syndrome | 15 |

| 5. Fulminant hepatic failure | 12 |

| 6. Secondary biliary cirrhosis | 8 |

| 7. Congenital hepatic fibrosis | 6 |

| 8. Primary hepatic malignancy | 3 |

| 9. Budd-Chiari syndrome | 2 |

| 10. Neonatal hepatitis | 2 |

| 11. Others | 4 |

| Total | 334 |

A total of 302 liver recipients had definite histories of hemorrhage from esophageal varices before liver transplantation; 217 were adults and 85 were children. The types of liver disease in these adult and pediatric variceal bleeders and the number of patients affected are listed in Tables III and IV. The liver function and the general condition of these 302 patients were all very poor and were classified in Child’s class C category. Furthermore, 22 patients had undergone nonselective shunt, 15 patients had undergone selective shunt, and 5 patients had undergone nonshunt operations for treatment of bleeding esophageal varices before liver transplantation. Two hundred nineteen patients had undergone endoscopic sclerotherapy for esophageal varices.

Table III.

Liver diseases of adult recipients who had a definite history of bleeding from esophageal varices

| Disease | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| 1. Postnecrotic and cryptogenic cirrhosis | 85 |

| 2. Primary biliary cirrhosis | 63 |

| 3. Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 31 |

| 4. Liver-based inborn metabolic errors (alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson’s, etc.) | 16 |

| 5. Alcoholic cirrhosis | 15 |

| 6. Secondary biliary cirrhosis | 4 |

| 7. Budd-Chiari syndrome | 2 |

| 8. Biliary atresia | 1 |

| Total | 217 |

Table IV.

Liver disease of pediatric recipients who had a definite history of bleeding from esophageal varices

| Disease | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| 1. Biliary atresia | 37 |

| 2. Liver-based inborn metabolic errors (alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson’s etc.) | 19 |

| 3. Postnecrotic and cryptogenic cirrhosis | 15 |

| 4. Congenital hepatic fibrosis | 5 |

| 5. Familial cholestatic syndrome | 4 |

| 6. Secondary biliary cirrhosis | 4 |

| 7. Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 1 |

| Total | 85 |

The survival data were analyzed as of Feb. 1, 1988, by the method of Kaplan-Meier. The follow-up period ranged from 6 months to 6 years 11 months, with a median follow-up of 2 years 3 months. None of the patients was lost from the follow-up. The statistical comparisons were made by the methods of Breslow and of Mantel-Cox. The difference was considered as significant when p value was less than 0.05.

RESULTS

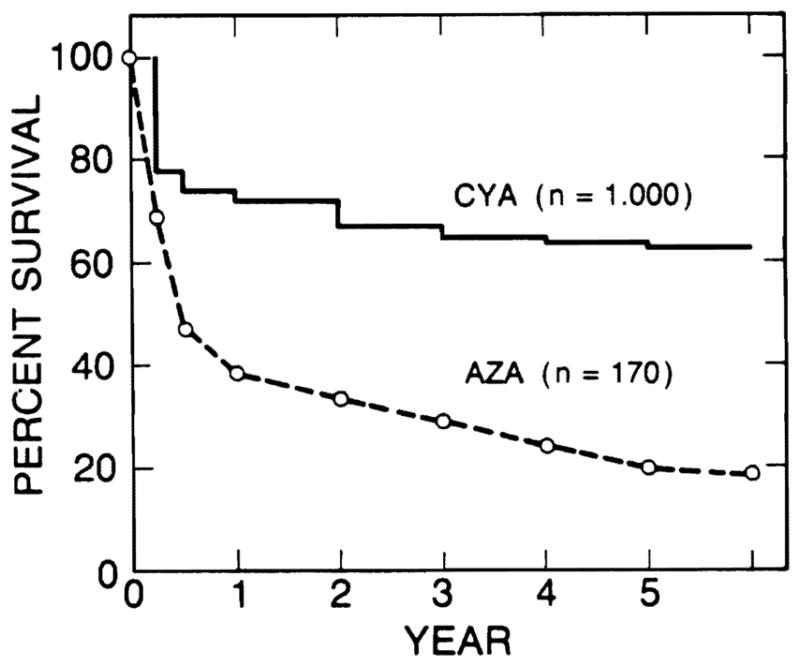

The overall survival rates of the 1000 consecutive patients after liver transplantation were 72% at 1 year, 67% at 2 years, 65% at 3 years, 64% at 4 years, and 63% at 5 years with cyclosporine-steroid therapy. These survivals were three times higher than those obtained with azathioprine-steroid therapy before 1980 (Fig. 1). The survival rates of 666 adult recipients were nearly identical to those of 334 pediatric recipients.

Fig. 1.

Survival rates after liver transplantation have improved significantly since the introduction of cyclosporine in 1980. CyA, cyclosporine group, 1,000 patients; AZA, azathioprine group, 170 patients.

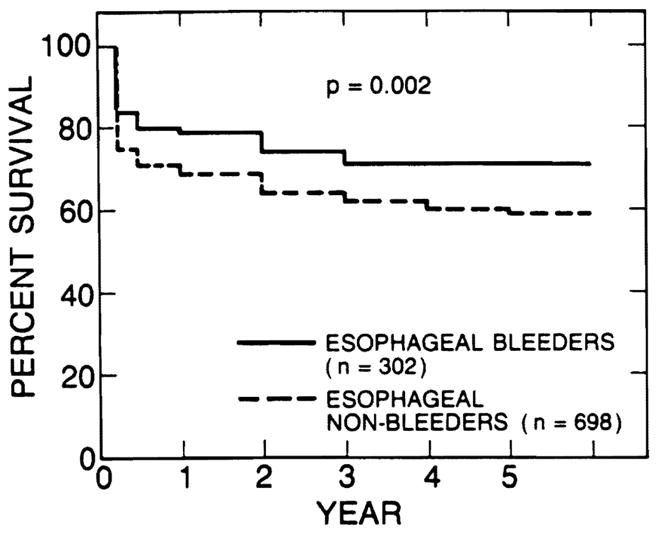

The survival rates of 302 patients who had bled from esophageal varices before transplantation (esophageal bleeders) were 79% at 1 year, 74% at 2 years, and 71 % at 3, 4, and 5 years after transplantation. Survival of 698 patients who had no history of variceal bleeding (variceal nonbleeders) was 69% at 1 year, 64% at 2 years, 62% at 3 years, 60% at 4 years, and 59% at 5 years. The survival rates of variceal bleeders were significantly higher than those of non bleeders (p < 0.01), as shown in Fig. 2. The survival rates of 217 adult esophageal bleeders were 78% at 1 year, 73% at 2 years, and 68% at 3, 4, and 5 years after transplantation, and those of 85 pediatric esophageal bleeders were 80% at 1 year and 77% at 2, 3, 4, and 5 years. There was no statistically significant difference in survival rates between adult and pediatric esophageal bleeders.

Fig. 2.

Survival rates of 302 patients who had bled from esophageal varices before transplantation (esophageal bleeders) were better than those of 698 patients who had not bled (esophageal nonbleeders). The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.002).

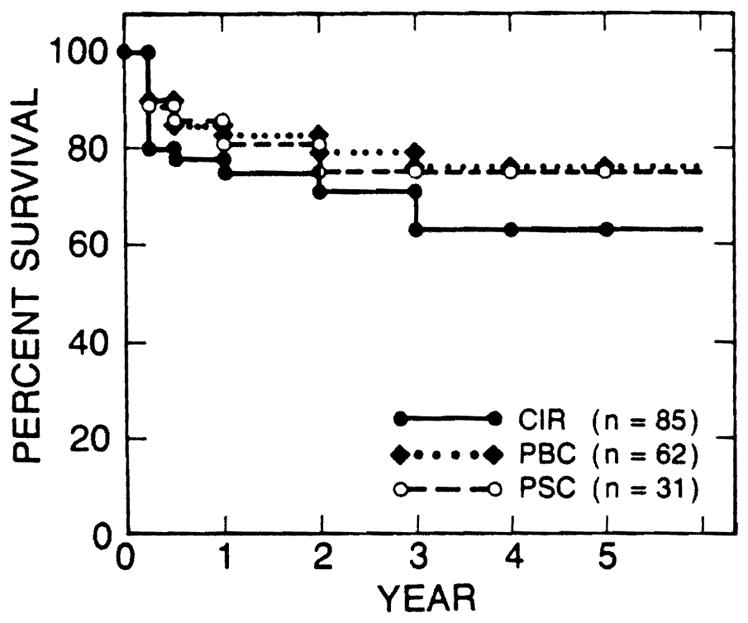

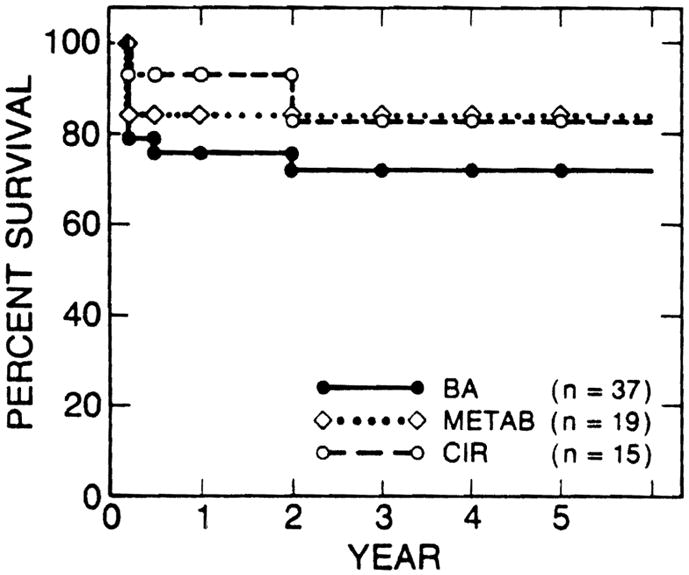

The survival rates after liver transplantation were compared among the esophageal bleeders with the three most common adult liver diseases (Fig. 3) and also among those with the three most common pediatric liver diseases (Fig. 4). There was no statistically significant difference in survival rates among the liver diseases in either the adult or the pediatric esophageal bleeders. The survival rates of 15 variceal bleeders with alcoholic cirrhosis were 93% at 1 year and 76% at 2 years after transplantation; these rates were similar to those of patients with nonalcoholic liver disease.

Fig. 3.

Survival rates of esophageal bleeders were similar among the three most common adult liver diseases. CIR, postnecrotic or cryptogenic cirrhosis; PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Fig. 4.

Survival rates of esophageal bleeders were similar among the three most common pediatric liver diseases. BA, biliary atresia; MET AB, liver-based inborn metabolic errors; CIR, postnecrotic or cryptogenic cirrhosis.

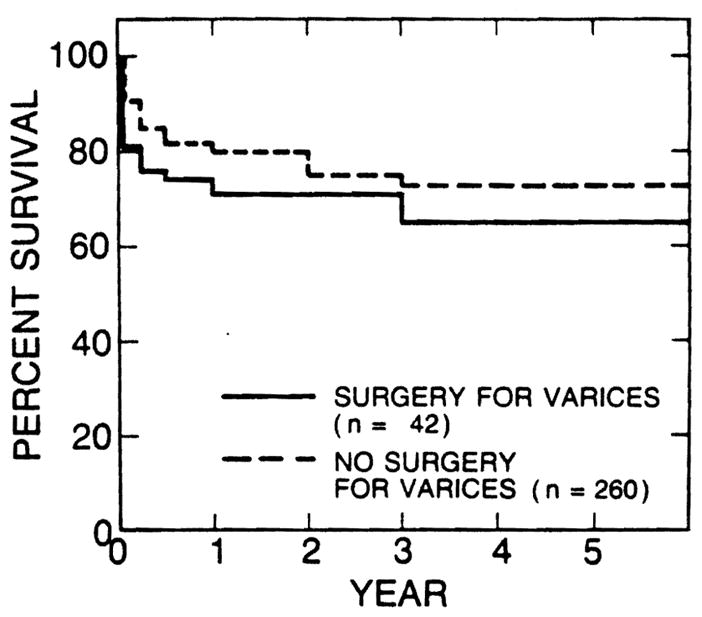

There were 42 patients who had had some kind of operation for bleeding esophageal varices (22 nonselective shunts, 15 selective shunts, and 5 nonshunt operations). The survival rates of these 42 patients were 71 % at 1 and 2 years and 65% at 3, 4, and 5 years after transplantation. Survival rates of the 260 patients who had not had an operation for bleeding varices were 80% at 1 year, 75% at 2 years, and 73% at 3, 4, and 5 years after transplantation (Fig. 5). Seven (17%) of 42 patients of the former group died within a month after transplantation, in contrast with 21 (8%) of the 260 patients of the latter group. However, the differences in short- and long-term survival rates of the two groups have not reached statistical significance.

Fig. 5.

Survival rates of 42 patients who had had some kind of operation for bleeding varices before liver transplantation were lower than those of 260 patients who had not had any such operation before transplantation. The difference, however, was not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

For more than four decades, portal-systemic shunts were readily accepted as the most effective treatment of bleeding from esophageal varices. Enthusiasm, however, started to wane more than two decades ago, when it became apparent that the price of preventing hemorrhage from esophageal varices by portal-systemic shunts was dehumanizing encephalopathy and progressive hepatic dysfunction.

Three controlled studies of prophylactic portal-systemic shunts concluded more than 15 years ago that, in spite of excellent protection from variceal hemorrhage, patients who had such shunts had poorer survival rates than patients who were treated with medical supportive measures alone, apparently because of increased frequency of death from hepatic failure among patients with shunts.1–3 Three controlled studies of therapeutic shunts also failed to show a statistically significant difference in the long-term survival rates between the patients with shunts and the medically treated patients after more than 10 years of follow-up.4–6

With increasing disenchantment with portal-systemic shunting, considerable efforts were expended in developing new operations or modifying old ones that prevent variceal hemorrhage efficiently without significantly altering hepatic circulation. The distal splenorenal shunt was introduced in 1967 by Warren, Zeppa, and Fomon7 as a selective shunt. In the last decade, the effectiveness of this selective shunt has been assessed in five different randomized controlled studies.8–12 All of these well-designed studies failed to show the survival superiority of selective shunt over nonselective shunt despite initial claims. Meanwhile, nonshunt operations (portal azygos disconnection) improved the old techniques and achieved survival rates similar to those achieved with shunt operations, although the incidence of rebleeding was higher than with the shunts.13–15 Since endoscopic sclerotherapy was reintroduced by Johnston and Rogers,16 the long-term management of bleeding varices by this endoscopic procedure has spread worldwide.

Having failed to improve the survival rates, selective shunt was critically examined against long-term sclerotherapy by two randomized trials.17, 18 In their preliminary report Warren and his associates17 concluded that sclerotherapy gave significantly better survival than the selective shunt when the sclerotherapy failures were rescued with surgical therapy, including selective and nonselective shunts and nonshunt operations. Rikkers and his associates18 reported that endoscopic sclerotherapy and shunt surgery (23 selective shunts and 3 nonselective shunts) provided similar results with respect to survival, hepatic function, and frequency of encephalopathy.

Table V compares the survival rates of 302 liver recipients who had a definite history of variceal hemorrhage with those reported in eight well-studied control trials of therapeutic shunt operations.4–6, 10–12, 17, 18 and three uncontrolled series of nonshunt operations.13–15 As the outcomes of shunt and nonshunt operations are highly influenced by the hepatic functional reserve of the patients at the time of operation,19 the results of one study cannot be simply compared with those of another. More than 75% of the patients in each report listed in Table V had good hepatic function or moderately impaired hepatic function (Child’s class A and B), and fewer than 25% of them had advanced hepatic dysfunction (Child’s class C). On the other hand, all the patients who received liver transplants had advanced hepatic dysfunction or far-advanced hepatic dysfunction. Despite this severe disadvantage of preoperative condition, the survival rates of liver transplant recipients who had had variceal hemorrhage were better than or similar to those of patients who had had other kinds of conventional therapy (Table V).

Table V.

Survival comparison among various treatments for bleeding esophageal varices (Child’s classes A, B, and C)

| Treatment | No. of patients | Survival rates (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 yr | 2 yr | 3 yr | 4 yr | 5 yr | ||

| Jackson et al. (1971) | ||||||

| Nonselective shunt | 67 | 80* | 73* | 62* | 58* | 55* |

| Medical | 77 | 80 | 66* | 43* | 35* | 32* |

| Resnick et al. (1974), | ||||||

| Nonselective shunt | 54 | 70* | 58* | 50* | 48* | 48* |

| Medical | 25 | 67* | 52* | 40* | 40* | 40* |

| Reynolds et al. (1981) | ||||||

| Nonselective shunt | 41 | – | 72* | 64* | 52* | 44 |

| Medical | 37 | – | 60* | 44* | 36* | 22 |

| Conn et al. (1981) | ||||||

| Selective shunt | 24 | 76* | 70* | – | – | – |

| Nonselective shunt | 29 | 70* | 67* | – | – | – |

| Langer et al. (1985) | ||||||

| Selective shunt | 38 | 80* | 76* | 63* | 54* | 51* |

| Nonselective shunt | 40 | 90* | 85* | 70* | 56* | 56* |

| Millikan et al. (1985) | ||||||

| Selective shunt | 26 | 85* | 77* | 65* | 60* | 55* |

| Nonselective shunt | 29 | 80* | 72* | 70* | 65* | 60* |

| Warren et al. (1986) | ||||||

| Sclerotherapy† | 36 | 90* | 84 | 82* | 82* | – |

| Selective shunt | 35 | 70* | 59 | 45* | 45* | – |

| Rikkers et al. (1987) | ||||||

| Sclerotherapy | 30 | 77* | 61 | 60* | 50* | – |

| Selective shunt‡ | 27 | 75* | 65 | 60* | 39* | – |

| Yamamoto et al. (1976) | ||||||

| Nonshunt operation | 64 | 81 | 75 | 70 | 70 | 65 |

| Sugiura et al. (1984) | ||||||

| Nonshunt operation | 256 | 87 | 84 | 81 | 78 | 78 |

| Spence et al. (1985) | ||||||

| Nonshunt operation | 100 | 73 | 65 | 54 | 51 | 47 |

| Present study (1988) | ||||||

| Liver transplantation | 302 | 79 | 74 | 71 | 71 | 71 |

Value estimated from survival curve.

Sclerotherapy failures wert rescued by surgical therapy.

Twenty-three selective shunts and four nonselective shunts.

Because the surgical therapy for esophageal varices is usually withheld from the patients with advanced hepatic dysfunction (Child’s class C), the literature contains few survival data for these patients.13, 15, 19–22 In Table VI the results obtained with liver transplantation are compared with those achieved in patients with advanced hepatic dysfunction after conventional surgical therapy. It is obvious that the survival rates of liver transplant recipients are far better than those achieved with conventional types of surgical therapy when the liver disease is advanced.

Table VI.

Survival comparison among various treatments for bleeding esophageal varices (Child’s class C, poor liver function)

| Treatment | No. of patients | Survival rates (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 yr | 2 yr | 3 yr | 4 yr | 5 yr | ||

| Turcotte et al. (1973) | ||||||

| Nonselective shunt | 50 | 36 | 32 | 22 | 20 | 17 |

| Yamamoto et al. (1976) | ||||||

| Nonshunt operation | 13 | 39 | 30 | 22 | 22 | 18 |

| Warren et al. (1982) | ||||||

| Selective shunt | ? | 60* | 53* | 45* | 40* | 35* |

| Nonselective shunt | ? | 50* | 40* | 37* | 20* | 15* |

| Rikkers et al. (1984) | ||||||

| Shunt and nonshunt operation† | 24 | 45 | 35* | 30* | 20* | 17* |

| Chandler et al. (1985) | ||||||

| Shunt‡ | 30 | 36 | 30 | 25 | 20 | 13 |

| Spence et al. (1985) | ||||||

| Nonshunt operation | 25 | 70 | 53 | 38 | 38 | 35 |

| Present study (1988) | ||||||

| Liver transplantation | 302 | 79 | 74 | 71 | 71 | 71 |

Value estimated from survival curve.

Fifteen nonselective shunt, seven selective shunts, and two nonshunt operations.

Both selective and nonselective operations.

As each disease has its own natural history, the results of various kinds of therapy for variceal hemorrhage should ideally be compared among patients with portal hypertension of similar etiology. In the literature, however, whether the etiology of cirrhosis will influence long-term survival after shunt operation is a matter of considerable controversy. Some investigators found that after shunt operations patients with nonalcoholic cirrhosis had significantly better long-term survival rates than those with alcoholic cirrhosis,21, 22 but others could not find a difference between the two groups.11, 24, 25 Our recent review of 1000 liver transplantations under cyclosporine-steroid immunosuppressive therapy26 has shown that the survival rates were similar among the three most common adult liver diseases (postnecrotic cirrhosis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and sclerosing cholangitis) and among the three most common pediatric liver diseases (biliary atresia, liver-based inborn metabolic errors, and postnecrotic cirrhosis). The survival rates of alcoholic cirrhosis were also similar to overall survival rates, although the numbers were small. In this study of the subgroup of 302 patients who had bled from esophageal varices, the original liver diseases did not influence the survival rates after liver transplantation.

The survival rates of the 42 patients who had had shunt or nonshunt operations for treatment of bleeding esophageal varices before liver transplantation were lower than those of patients in whom variceal hemorrhage was treated medically and/or with long-term endoscopic sclerotherapy, but the difference was not statistically significant. It is obvious, however, that a previous shunt or nonshunt operation made the transplant operation more difficult and thereby increased early mortality, as shown in Fig. 5.

Recently two randomized control trials17, 18 have shown that long-term sclerotherapy can provide the same (or better) survival rates as the distal splenorenal shunt, which is generally considered the best among shunt operations. Although the data are not available for nonshunt operations, the results can be expected to be similar to those of shunt operations. The survival rates after liver transplantation for patients with advanced liver disease who had bled from varices are quite satisfactory as presented here. There are ample data in the literature, as discussed, that support long-term sclerotherapy as the treatment of first choice for bleeding esophageal varices. The patients in whom long-term sclerotherapy failed should be considered for liver transplantation, unless some clear contraindications for transplantation exist. We believe that shunt or nonshunt operations should not be performed for treatment of variceal hemorrhage, except under the most unusual circumstances. Liver transplantation is the treatment of choice for many patients with advanced liver disease after failure of sclerotherapy.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Research Grants from the Veterans Administration and Project Grant AM 29961 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.

Footnotes

Presented at the Forty-fifth Annual Meeting of the Central Surgical Association, Columbus, Ohio, March 10–12, 1988.

References

- 1.Jackson FC, Perrin EB, Smith AG, Dagradi AE, Nadal HM. A clinical investigation of the portacaval shunt. II. Survival analysis of the prophylactic operation. Am J Surg. 1968;115:22–41. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(68)90127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resnick RH, Chalmers TC, Ishihara AM, et al. A controlled study of the prophylactic portacaval shunt: a final report. Ann Intern Med. 1969;70:675–88. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-70-4-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conn HO, Lindenmuth WW, May CJ, Ramsby GR. Prophylactic portacaval anastomosis: a tale of two studies. Medicine. 1972;51:27–40. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197201000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson FC, Perrin EB, Felix WR, Smith AG. A clinical investigation of the portacaval shunt. V. Survival analysis of the therapeutic operation. Ann Surg. 1971;174:672–701. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197110000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Resnick RH, Iber FL, Ishihara AM, Chalmers TC, Zimmerman H Boston Inter-Hospital Liver Group. A controlled study of the therapeutic portacaval shunt. Gastroenterology. 1974;67:843–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynolds TB, Donovan AJ, Mikkelsen WP, Redeker AG, Turrill FL, Weiner JM. Results of a 12-year randomized trial of portacaval shunt in patients with alcoholic liver disease and bleeding varices. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:1005–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warren WD, Zeppa R, Fomon JJ. Selective transsplenic decompression of gastroesophageal varices by distal splenorenal shunt. Ann Surg. 1967;166:437–55. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196709000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reichle FA, Fahmy WF, Golsorkhi M. Prospective comparative clinical trial with distal splenorenal and mesocaval shunts. Am J Surg. 1979;137:13–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(79)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer JE, Bower RH, Atamian S, Welling R. Comparison of distal and proximal splenorenal shunts: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1981;194:531–44. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198110000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conn HO, Resnick RH, Grace ND. Distal splenorenal shunt versus portal-systemic shunt: current status of a controlled trial. Hepatology. 1981;1:151–60. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840010211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langer B, Taylor BR, Mackenzie DR, Gilas T, Stone RM, Blendis L. Further report of a protective randomized trial comparing distal splenorenal shunt with end-to-side portacaval shunt: an analysis of encephalopathy. survival, and quality of life. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:424–9. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90502-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Millikan WJ, Warren WD, Henderson JM, et al. The Emory prospective randomized trial: selective versus nonselective shunt to control variceal bleeding. Ten-year follow-up. Ann Surg. 1985;201:712–22. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198506000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamamoto S, Hidemura R, Sawada M, Takeshige K, Iwatsuki S. The late results of terminal esophago-proximal gastrectomy (TEPG) with extensive devascularization and splenectomy for bleeding esophageal varices in cirrhosis. Surgery. 1976;80:106–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugiura M, Futagawa S. Results of 636 esophageal transections with paraesophagogastric devascularization in the treatment of esophageal varices. J Vasc Surg. 1984;1:254–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spence RAJ, Johnston GW. Results in 1000 consecutive patients with stapled esophageal transection for varices. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985;160:323–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston GW, Rogers HW. A review of 15 years’ experience in the use of sclerotherapy in the control of acute hemorrhage from esophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:797–800. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800601011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warren WD, Henderson JM, Millikan WJ, et al. Distal splenorenal shunt versus endoscopic sclerotherapy for long-term treatment of variceal bleeding: preliminary report of a prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1986;203:454–62. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198605000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rikkers LF, Burnett DA, Volentine GD, Buchi KN, Cormier RA. Shunt surgery versus endoscopic sclerotherapy for long-term treatment of variceal bleeding: early results of a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1987;206:261–71. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198709000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turcotte JG, Lambert ML. Variceal hemorrhage, hepatic cirrhosis, and portacaval shunts. Surgery. 1973;73:810–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chandler JG, VanMeter CH, Kaiser DL, Mills SE. Factors affecting immediate and long-term survival after emergent and elective splanchnic-systemic shunts. Ann Surg. 1985;201:476–87. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198504000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warren WD, Millikan WJ, Henderson JM, et al. Ten years’ portal hypertensive surgery at Emory: results and new perspectives. Ann Surg. 1982;195:530–42. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198205000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rikkers LF, Soper NJ, Cormier RA. Selective operative approach for variceal hemorrhage. Am J Surg. 1984;147:89–96. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeppa R, Hutson DG, Levi ]U, Livingstone AS. Factors influencing survival after distal splenorenal shunt. World J Surg. 1984;8:733–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01655770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adson MA, Van Heerden JA, Ilstrup DM. The distal splenorenal shunt. Arch Surg. 1984;119:609–14. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1984.01390170103020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Busuttil RW. Selective and nonselective shunts for variceal bleeding: a prospective study of 103 patients. Am J Surg. 1984;148:27–35. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90285-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE, Todo S, et al. Experience in 1,000 liver transplantations under cyclosporine-steroid therapy; a survival report. Transplant Proc. 1988;20:498–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]