Abstract

The interactions between the N- and C-terminal heptad repeat (NHR and CHR) regions of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) glycoprotein gp41 create a structure comprising a 6-helix bundle (SHB). A sequence in the SHB named the “pocket” is crucial for the SHB's stability and for the fusion inhibitory activity of 36-residue NHR peptide N36. We report that a short 27-residue peptide, N27, which lacks the pocket sequence, exhibits potent inhibitory activity in both cell-cell and virus-cell fusion assays when fatty acids were conjugated to its N but not C terminus. Furthermore, mutations in the positions that prevent interaction with the CHR but not with the NHR resulted in a dramatic reduction in N27 activity. These data support a mechanism in which N27 mainly targets the CHR rather than the internal NHR coiled-coil, reveal the N-terminal edge of the endogenous core structure in situ and hence complement our recent findings of the C-terminal edge of the core, and provide a new approach for designing short inhibitors from the NHR region of other lentiviruses due to similarities in their envelope proteins.—Wexler-Cohen, Y., Ashkenazi, A., Viard, M., Blumenthal, R., Shai, Y. Virus-cell and cell-cell fusion mediated by the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein is inhibited by short gp41 N-terminal membrane-anchored peptides lacking the critical pocket domain.

Keywords: membrane fusion, HIV-1 entry inhibitor, peptide-membrane interaction, viral envelope protein

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) belongs to the family of lentiviruses and is responsible for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). To start an infectious cycle the virus must fuse its membrane with that of its host cell. HIV-1, like other enveloped viruses, utilizes a protein embedded in its membrane, termed envelope protein (ENV), to facilitate the fusion process (1–5). It is composed of 2 noncovalently associated subunits, gp120 and gp41, which are organized as trimers (1, 6). Gp120 is responsible for the host tropism (reviewed in ref. 7), whereas gp41, the transmembrane subunit, is responsible for the actual fusion event (reviewed in ref. 8).

The extracellular part of gp41 is composed of several functional regions, including the fusion peptide (FP), N-terminal heptad repeat (NHR), and C-terminal heptad repeat (CHR). The ability of the virus to fuse its own membrane with that of the host cell depends on the conversion between 3 identified ENV conformations: the native, metastable conformation; the prefusion conformation; and the postfusion conformation (9). In the native, metastable conformation, gp41 is considered to be sheltered by gp120. Binding of gp120 to the receptor CD4 and a coreceptor such as CCR5 or CXCR4 causes major conformational changes that drive the transition from the native into the prefusion conformation. In this conformation, gp41 is extended, leading to the insertion of the FP into the host cell membrane (10–12). The complex representing the postfusion conformation is designated the 6-helix bundle (SHB) or “core” structure. It is composed of 3 CHR regions that are packed in an antiparallel manner into hydrophobic grooves created on a trimeric, internal, NHR coiled coil (6, 13). Similar bundles are created in intracellular vesicle fusion by SNARE proteins, thus demonstrating a common mechanism in diverse systems (14, 15). In the core structure, each of the grooves on the surface of the NHR trimer has a deep cavity called the “pocket” that interacts with 3 conserved hydrophobic residues of the CHR region (16). These interactions are crucial for maintaining the stability of the SHB; this suggests that this domain is an attractive target for antiviral compounds.

Folding into the postfusion conformation is apparently the rate-limiting step for the fusion reaction, and it enables inhibition of the fusion process. This is demonstrated by the inhibitory capability of C or N peptides derived from the CHR or NHR regions, respectively. These peptides bind their endogenous counterparts, thereby preventing progression into the postfusion conformation and consequently arresting fusion (17–20). N peptides inhibit HIV-1 entry by 2 possible mechanisms. First, the N peptides may target an exposed C-helix region of gp41. Alternatively, synthetic N peptides can interact with the N helices of gp41, thereby interfering with their coiled coil formation within a gp41 trimer. Because N peptides tend to aggregate, C peptides are more potent fusion inhibitors (21), and therefore they have attracted the most therapeutic effort and research (the first FDA-approved fusion inhibitor is a C peptide) (22).

To reveal the role of specific domains within the NHR in a dynamic membrane fusion event, we investigated the inhibitory capacity of a short N peptide, N27. This peptide was derived from the extended N terminus of the classical NHR region, N36, but lacks the pocket sequence. Strikingly, N27 exhibited a potent fusion inhibitory effect only when a fatty acid was conjugated to its N terminus and not to its C terminus. Using a designed mutant peptide that does not bind to the CHR, we discuss its mode of action and reveal an important role for the extended N terminus of the NHR in gp41-mediated fusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

F-moc amino acids including lysine with an MTT side-chain protecting group and F-moc Rink Amide MBHA resin were purchased from Novabiochem (Laufelfinger, Switzerland). Other peptide synthesis reagents, fatty acids, namely, octanoic acid (C8), dodecanoic acid (C12), and hexadecanoic acid (C16), lysophosphatidylcholine, and PBS were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (Rehovot, Israel). DiD (DiIC18(5) or 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′,-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine, 4-chlorobenzenesulfonate salt) and DiI (1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′,0-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate) lypophilic fluorescent probes were obtained from Biotium (Hayward, CA, USA). Buffers were prepared in double-distilled water.

Cell lines and reagents

Cell culture reagents and media were purchased from Biological Industries Israel (Beit Haemek, Israel). All cell lines were obtained through the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). Jurkat E6-1 cells were obtained from Dr. Arthur Weiss (University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA) (23), and Jurkat HXBc2 (4) cells expressing HIV-1 HXBc2 Rev, and ENV proteins were from obtained from Dr. Joseph Sodroski (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA) (24). Cells were cultured every 3–4 d and maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. For ENV expression, Jurkat HXBc2 cells (4) were transferred to medium without tetracycline 3 d prior to the experiments.

Peptide synthesis and fatty acid conjugation

Peptides were synthesized on Rink Amide MBHA resin by using the F-moc strategy as described previously (25). C-terminally conjugated N peptides contain a lysine residue at their C terminus with an MTT side-chain protecting group, enabling the conjugation of a fatty acid that requires a special deprotection step under mild acidic conditions (2×1 min of 5%TFA in DCM and 30 min of 1% TFA in DCM). Conjugation of a fatty acid to the N terminus was performed using standard F-moc chemistry. All peptides were cleaved from the resin by a TFA:DDW:TES (93.1:4.9:2 (v/v)) mixture and purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography to >95% homogeneity. The molecular weight of the peptides was confirmed by platform LCA electrospray mass spectrometry.

Cell-cell fusion inhibition assay

The protocol utilizing Jurkat E6–1 and Jurkat HXBc2 cells for a cell-cell fusion assay was previously described (26). In short, Jurkat E6–1 and Jurkat HXBc2 cells were labeled with DiI and DiD lypophilic fluorescent probes, respectively. The 2 cell populations were coincubated for 6 h in a ratio of 1:1 in the presence of different concentrations of the inhibitory peptides. Cells that coincubated without the presence of peptides served as an optimal fusion reference. Unlabeled cells served as an intrinsic fluorescence control. Cells labeled separately with DiI or DiD were used to compensate for the optimal separation of fluorescent signals. Jurkat HXBc2 cells labeled with DiI were coincubated with Jurkat HXBc2 cells labeled with DiD for a fusion background that was subtracted from the measurements of the experiment. Data were collected on FACSort and upgraded to a FACSCalibur cell analyzer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Fitting of the data points was performed according to the following equation, derived from Hill's equation:

In brief, in this equation B is the maximum value and therefore it equals 100% fusion, A is the value of inhibition concentration at 50% fusion (IC50), and c represents Hill's coefficient, in this case, the inhibitory oligomeric state of the peptide. For the fitting, we uploaded the X and Y values of the raw data (after subtracting the background) into a nonlinear least squares regression (curve fitter) program that provided the IC50 value (parameter A), as well as the inhibitory oligomeric state of the peptide (parameter c).

Virus infectivity assay

HIV-1 HXB2 concentrated virus stock was a kind gift of the AIDS Vaccine Program, SAIC (Frederick, MD, USA). The infectivity of HIV-1 HXB2 was determined using the TZM-bl cell line as a reporter. Cells were added (2×104 cells/well) to a 96-well clear-bottomed microtiter plate with 10% serum-supplemented DMEM. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 18–24 h to allow the cells to adhere. The medium was then aspirated from each well and replaced with serum-free DMEM containing 40 μg/ml DEAE-dextran. Stock dilutions of each peptide were prepared in DMSO so that each final concentration was achieved with 1% dilution. On addition of the peptides, the virus was added to the cells diluted in serum-free DMEM containing 40 μg/ml DEAE-dextran. The plate was then incubated at 37°C for 18 h to allow the infection to occur. Luciferase activity was analyzed using the Steady-Glo Luciferase assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). All infectivity assays were performed in triplicate. IC50 values were calculated from the fitted curve similarly to the cell-cell fusion assay.

Triple staining flow cytometry fusion assay

The protocol was previously described (27). In brief, for triple staining, the same cell-cell fusion inhibition assay experiment as above was performed in the presence of NBD-labeled peptides. Cells labeled separately with DiI or DiD, and unlabeled cells in the presence of an NBD-labeled peptide were used to compensate for the optimal separation of the 3 fluorescent signals. For each data point 5 × 105 events were collected. The 8 different possible combinations (triple, NBD, DiI, DiD, NBD+DiI, NBD+DiD, DiI+DiD, no label) were defined in the analysis software, and the percentage of each was calculated. The percentage of NBD labeling (peptide) on all cell types in relation to all available labeled cells in the system was calculated. This analysis provided us with the percentage of cells labeled with NBD peptide:

In addition, the percentage of NBD labeling (peptide) in cells labeled with DiD (effector) or DiI (target) cells was further calculated. Analysis of the data enabled us to examine the relative binding of labeled peptides to different cell populations, namely, target or effector cells:

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

CD measurements were performed on an Aviv 202 spectropolarimeter (Aviv Instruments, Lakewood, NJ, USA). The spectra were scanned using a thermostatic quartz cuvette with a path length of 1 mm. Wavelength scans were performed at 25°C; the average recording time was 20 s, in 1-nm steps; and the wavelength range was 190–260 nm. Peptides were scanned at a concentration of 10μM in HEPES buffer (5 mM, pH 7.4).

RESULTS

Conjugation of a fatty acid to a short NHR peptide potentiates its inhibitory activity

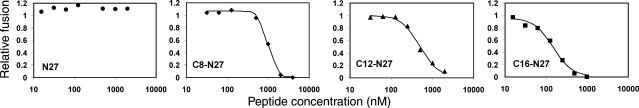

Previously we identified the C-terminal boundary of the core structure in situ by utilizing a short C peptide named DP, derived from T20, the FDA-approved HIV entry inhibitor. DP regained full inhibitory activity when conjugated to a fatty acid (27). Here we synthesized the NHR-derived peptide to which DP interacts in the postfusion conformation, namely, N27 (Fig. 1A). This peptide, which lacks the critical pocket domain, has been conjugated with fatty acids of increasing lengths at its N terminus (Table 1) The various peptides were examined in cell-cell and virus-cell fusion inhibition assays. In general the inhibitory activity against virus-cell fusion was higher than that in the cell-cell fusion assay. While N27 was inactive in cell-cell fusion assay, the conjugation of a fatty acid at its N terminus conferred an inhibitory activity that was dependent on the length of the fatty acid (Fig. 2). C8-N27, C12-N27, and C16-N27 exhibited inhibitory IC50 values of 1075 ± 90, 473 ± 74, and 148 ± 4 nM, respectively. Note that only 26 aa from the original NHR sequence are contained in this peptide. The C-terminal lysine was introduced to allow for the conjugation of a fatty acid at this end of the peptide. N27 conjugated with a fatty acid at its C terminus was inactive in the cell-cell fusion inhibition assay (Table 1).

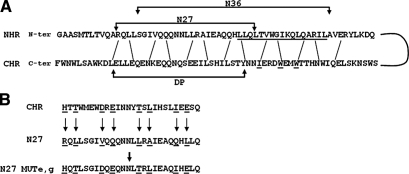

Figure 1.

A) Representation of the bonds created between the NHR and CHR regions in the postfusion conformation. Amino acids that are underscored represent either those amino acids that create the pocket (in the NHR) or those that are packed into the pocket (in the CHR). Sequence of the novel peptide N27 is indicated as well as that of the known peptides, DP and N36. B) Sequence of the N27 MUTe,g. Sequence of the N27 peptide is indicated at the center. The e and g positions of all peptides are underscored. To create the N27 MUTe,g, the e,g positions of the N27 peptide were replaced by the e,g positions of the classic CHR peptide. The rationale followed the original design of the N36 MUTe,g peptide (28).

Table 1.

Sequences, designations, and IC50 values of the peptides and their lipophilic conjugates, analyzed using cell-cell fusion assay

| Designation | X | Peptide sequence | Z | IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N27 | X-RQLLSGIVQQQNNLLRAIEAQQHLLQK-Z | Not active | ||

| AcN27 | Acetate | Not active | ||

| C8-N27 | C8- | 1075 ± 90 | ||

| C12-N27 | C12- | 473 ± 74 | ||

| C16-N27 | C16- | 148 ± 4 | ||

| N27-C16 | -C16 | Not active | ||

| N25 | X-RQLLSGIVQQQNNLLRAIEAQQHLL | Not active | ||

| C16-N25 | C16- | 484 ± 60 | ||

| N23 | X-RQLLSGIVQQQNNLLRAIEAQQH | Not active | ||

| C16-N23 | C16- | 1931 ± 187 | ||

| N22 | X-SGIVQQQNNLLRAIEAQQHLLQ | Not active | ||

| C16-N22 | C16- | Not active | ||

| N26 RGGL MUT | X-RGGLSGIVQQQNNLLRAIEAQQHLLQ | Not active | ||

| C16-N26 RGGL MUT | C16- | Not active | ||

| N27 MUTe,g | X-HQTLSGIDQEQNNLTRLIEAQIHELQK-Z | Not active | ||

| C16-N27 MUTe,g | C16- | Not active | ||

| N27 RQLL MUTe,g | X-RQLLSGIDQEQNNLTRLIEAQIHELQK-Z | Not active | ||

| C16-N27 RQLL MUT | C16- | Not active |

IC50 values (means±sd) were calculated from 3 different fusion inhibition experiments.

Figure 2.

Cell-cell fusion inhibition assay. Representative inhibition curves (from ≥3 experiments for each peptide) for the active peptides. Symbols denote the data, whereas the continuous line denotes the fitted curve. ●, N27 alone; ♦, C8-N27; ▲, C12-N27; ■, C16-N27.

N-terminal sequence of N27 peptide is crucial for its fusion inhibitory activity

N27 is shifted in its amino acid sequence with regard to N36; it starts 4 aa upstream from the N terminus of N36 (RQLL) and ends 14 aa upstream from the C terminus of N36 (Fig. 1). Whereas N36 includes the pocket sequence, N27 does not, but contains an extended N terminus of the NHR. To examine whether N27 made up the minimal sequence that enables a potent inhibitory effect, we shortened the peptide at the C or N terminus. The truncation of 2 and 4 aa in the C terminus of N27 reduced its inhibitory capability. In the cell-cell fusion assay C16-N25 and C16-N23 resulted in inhibitory IC50 values of 484 ± 60 and 1931 ± 187 nM, respectively. The removal of 4 aa (RQLL) from the N terminus of N27 resulted in inactive peptide (C16-N22). The importance of the RQLL sequence was further investigated by mutating this sequence to RGGL. The peptide, N26 RGGL MUT, as well as its palmitic acid conjugate, was inactive in cell-cell fusion assay (Table 1).

Fatty acid-conjugated N27 peptides inhibit gp41-mediated fusion by binding the CHR region

The sites named e and g positions in the NHR are critical for its interaction with the C helices. Previously, the e and g positions of the N36 peptide were replaced so that the resulting mutant, N36 MUTe,g, could still self-assemble to create the internal coiled coil but could no longer interact with the CHR region to create the SHB (28). Formerly, by conjugating fatty acids to N36 MUTe,g, we were able to distinguish between 2 modes of binding and inhibition of conjugated N peptides (26). Here we synthesized an N27 peptide with the same mutations in its e and g positions as N36 MUTe,g (Fig. 1B). This peptide, N27 MUTe,g, as well as its fatty acid conjugates, was inactive in a cell-cell fusion assay (Table 1). We demonstrate here that the RQLL sequence is important for N27 activity; therefore, it might be assumed that the e,g mutations in this sequence were the reason for the inactivation of the N27 MUTe,g. To rule out this possibility, we prepared a N27 MUTe,g with the endogenous sequence (RQLL) or with continuous e,g mutations (HQTL). Both peptides as well as their fatty acid conjugates were inactive in cell-cell fusion assay (Table 1).

Lipopeptides exhibit a similar pattern of inhibition on virus-cell infection

Various C16-conjugated N27 peptides were introduced to CD4-expressing cells infected with fully infectious HIV-1 viruses. The fusion inhibitory activities of the peptides are represented by the IC50 values derived from their inhibition curves (Table 2). As a control, we used the C-peptide entry inhibitor T20. We found that N27 alone was active, and its inhibitory activity increased following fatty acid conjugation to the N terminus in correlation with the length of the fatty acid. C16-N27 demonstrated highly potent inhibitory activity similarly to T20 (IC50 of 10 nM). The mutations in the e,g positions caused ∼60-fold reduction in the inhibitory activity of C16-N27. Conjugation of the fatty acid to the C-terminal of N27 (N27-C16) transformed it to a very weak inhibitor. Note that the inhibitory activity against virus-cell fusion was higher than that in the cell-cell fusion assay. However, the 2 assays demonstrated similarities in the inhibition pattern of the peptides. The possible reasons for that will be elaborated in the discussion.

Table 2.

IC50 values of N27 and its fatty acid conjugates, analyzed using virus-cell fusion assay

| Designation | IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|

| N27 | 338 ± 16 |

| C8-N27 | 293 ± 27 |

| C12-N27 | 182 ± 15 |

| C16-N27 | 10 ± 1 |

| N27-C16 | >1000 |

| C16-N27 MUTe,g | 643 ± 137 |

| N27 MUTe,g-C16 | >1000 |

IC50 values (means±sd) were calculated from 2 independent experiments. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. For comparison, IC50 of the FDA-approved entry inhibitor, T-20, in the assay was 20 nM.

C- and N-terminal fatty acid-conjugated peptides bind similarly to cell membranes

A possible explanation for the loss of inhibitory activity of the C-terminal-conjugated N27 peptides could originate from their inability to bind the cell membrane. Through a triple-staining flow cytometry assay, we demonstrated that N27 conjugates (either to the N or C terminus) exhibited similar abilities to bind to the cell membrane, independently of the cell population considered (unpublished results). Thus, we can conclude that the ability to anchor to the cell membrane does not explain the difference in the inhibitory activity.

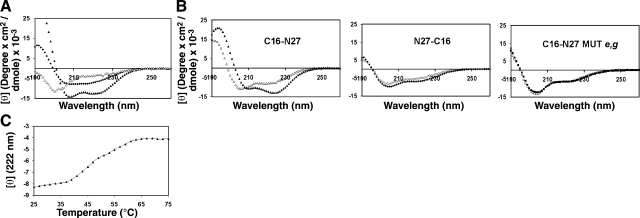

C- and N-terminal fatty acid-conjugated N27 peptides differ in their ability to create a stable core structure

To examine whether the N27 conjugates differ in their secondary structure or their ability to create a core structure with the CHR region, we performed CD experiments. The CD signal of each peptide was measured and is presented in Fig. 3A. C16-N27 and N27-C16 exhibited a partial α-helical structure in solution (fractional α-helicity of 37 and 16%, respectively). This observation showed that the orientation of the fatty acid contributed to the secondary structure of N27. The peptide's ability to create a core structure with its CHR counterpart (DP) in solution was monitored by calculating their combined signal, assuming that they do not interact with each other. This signal was compared to the actual signal monitored on coincubation of the 2 peptides together. If the couple interacts, a difference between the 2 signals is expected. C16-N27 interacted with DP, whereas N27-C16 was unable to create a core structure (Fig. 3B). As expected, the mutated peptide in its e,g positions was unable to create a core structure with DP (Fig. 3B). The stability of the C16-N27+DP complex was further characterized by performing temperature denaturation (Fig. 3C), yielding a Tm of 47°C for the complex melting. Overall, these data indicate that the fusion inhibitor C16-N27 peptide was able to create a core structure with DP, whereas core structure formation was not observed in the poorly active peptides (N27-C16 and the e,g mutant).

Figure 3.

A) Utilizing CD spectroscopy to analyze peptide structure. Peptides were measured at 10 μM in 5 mM HEPES. ▲, C16-N27; ♦, v N27-C16; ▵, DP. B) Analysis of ability of peptides to create a core structure with DP. Open shape in each panel represents the calculated noninteracting signal for combining an N peptide with DP; closed shape represents the actual experimental signals, obtained following incubation of the 2 peptides together. C) Temperature denaturation of the C16-N27 + DP core. Complex was created at 10 μM in 5 mM HEPES.

DISCUSSION

Peptide fusion inhibitors of HIV are a well-established tool for dissecting the intermediate states during a dynamic membrane fusion event involving the HIV virus (18–20, 29). The pocket sequence has long been established as a crucial interaction interface for maintaining the stability of the core structure; therefore, it has led to research mostly on N peptides that contain the pocket region. However, it has already been demonstrated that the core structure in the dynamic fusion event is larger than that analyzed using the crystal structure (based on N36 and C34 peptides) (27, 30, 31). Here we studied a short N peptide, N27, lacking the C-terminal sequence of N36, which makes up the pocket of the SHB structure (Fig. 1). Conjugation of fatty acids with increasing lengths to the N terminus of the peptide resulted in increased inhibitory activity in the low nanomolar range (Tables 1 and 2).

The N27 peptide differs from the N36 peptide by 2 important characteristics:

1) Formerly, we compared the inhibitory mode of action of a fatty acid-conjugated N36 to its fatty acid-conjugated mutant peptide, N36 MUTe,g, which cannot bind the CHR region. All the peptides exhibited potent inhibitory activity (26). This comparison enabled us to distinguish between 2 possible inhibitory modes for N36: inhibiting the creation of the core structure by binding the CHR, or inhibiting the creation of the internal NHR coiled coil by binding the endogenous NHR. Here we synthesized the short e,g mutant of the N27 peptide, namely, N27 MUTe,g (Fig. 1B), and its fatty acid conjugates. The e,g mutation did interfere with the ability of N27 to create a core structure with its CHR counterpart, DP (Fig. 3) but, unexpectedly, and contrary to what was observed with N36, the fatty acid-conjugated N27 MUTe,g was poorly active (Tables 1 and 2). Overall, the data presented herein support a mechanism in which the N-terminally conjugated N27 inhibits fusion mainly by targeting the CHR prior to SHB formation, thereby preventing gp41 folding into the postfusion conformation (Table 3). Although we showed that the N-terminal-conjugated N27 peptides are inserted to the cell membrane independently of the cell population considered; it is reasonable to assume that the peptides inhibit by binding the CHR in an antiparallel fashion when they are anchored to the viral membrane. This inhibition model differs from the accepted model of the N peptides, such as N36, in which they can either target the NHR or the CHR.

2) Owing to the importance of the pocket in the fusion process, researchers concentrated on this region when designing inhibitory N peptides (21, 32). Here a short fatty acid-conjugated N27 peptide that lacks the pocket sequence but comprises an extended N terminus of N36 peptide (RQLL sequence) exhibited a potent fusion inhibitory effect. This effect was abolished by either deleting or mutating the RQLL sequence (Table 1), suggesting that the extended N terminus of the NHR plays a major role in stabilizing the SHB structure, in addition to the pocket domain. Furthermore, it explains why the N36 peptide does not exhibit the same inhibition characteristics as N27.

Table 3.

Summary of the characteristics of the membrane-anchored N27 peptides

| Peptide characteristic | Palmitic acid-conjugated N27 peptides |

|---|---|

| Inhibition by N-terminal-conjugated peptide | + |

| Inhibition by, e.g., mutant of N-terminal-conjugated peptide | − |

| Inhibition by C-terminal-conjugated peptide | − |

| Core structure formation by N-terminal-conjugated peptide | + |

| Core structure formation by C-terminal-conjugated peptide | − |

| Binding of the N- and C-terminal-conjugated peptides to the cell membrane | Same extent |

| Mode of action of fusion inhibition | Binding mainly the CHR, thus preventing core formation |

For fusion inhibition, + indicates potent activity, − indicates poor or no activity.

In this work, we analyzed the inhibitory activity of short, membrane-anchored, N peptides by cell-cell or virus-cell fusion assays. In both assays we obtained the same tendency of inhibition. However, the inhibitory activity against virus-cell fusion was higher than that of the cell-cell fusion (Tables 1 and 2). It is assumed that fewer envelope glycoproteins are required to mediate virus-cell vs. cell-cell fusion (33), which may increase the inhibitory activity of the peptides in virus-cell fusion assay. An additional major difference relates to the lipid environment in which the envelope is presented at the cell surface or in the viral membrane. The viral membrane has a unique lipid composition, which differs significantly from the T cell membrane (34). Such a difference can modify the antiviral activity of peptides, but we cannot rule out the possibility that the differences in the inhibitory potencies are the results of different experimental approaches used in the 2 assays.

HIV-1 also targets other cells, such as macrophages and epithelial mucosal cells (35), that have some difference in their membrane lipid composition. These differences may also modulate the fusion inhibitory activity of the peptides when anchored to the membrane of different types of target cells.

Inhibition of HIV-1-cell fusion has been demonstrated by several N or C peptides, peptides that originate from the endogenous NHR or CHR sequences of gp41, respectively. The N peptides that have been researched the most are N36 (36 residues), DP107 (37 residues), and their analogues (21, 28, 32, 36, 37). The only short N peptide that was utilized so far corresponded to the 17 C-terminal amino acids of N36. It was however used as a fusion construct with a known (unrelated to HIV) coiled coil protein in order to prevent aggregation (21). Besides resulting in a peptide longer in its overall length than N36, this peptide still contained the pocket. In the current study, the inhibitory activity of C16-N27 in the virus-cell fusion assay was comparable to the inhibitory activity of the FDA-approved drug T20. Therefore, the results presented here might support further consideration of peptides derived from the NHR region as future therapeutic tools.

In summary, the N27 peptide exhibits increased inhibitory activity at the low nano-molar range on fatty acid conjugation only to its N terminus. To our knowledge, this is the first short inhibitory N-terminal-derived peptide that lacks the pocket domain. These data support a mechanism in which N27 mainly targets the CHR rather than the internal NHR coiled coil; reveal the N-terminal edge of the endogenous core structure in situ and hence complement our recent findings of the C-terminal edge of the core; and provide a new approach for designing short inhibitors from the NHR region of other lentiviruses because of similarities in their envelope proteins.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Batya Zarmi for her valuable help with peptide purification, and Dr. Ayala Sharp and Eitan Ariel and the staff of the flow cytometry unit at the Weizmann Institute of Science for their valuable technical assistance and advice.

This study was supported by the Israel Science Foundation and has been funded in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, NIH, under contract HHSN26120080001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government. This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

REFERENCES

- 1. Center R. J., Leapman R. D., Lebowitz J., Arthur L. O., Earl P. L., Moss B. (2002) Oligomeric structure of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein on the virion surface. J. Virol. 76, 7863– 7867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang C. W., Chishti Y., Hussey R. E., Reinherz E. L. (2001) Expression, purification, and characterization of recombinant HIV gp140: the gp41 ectodomain of HIV or simian immunodeficiency virus is sufficient to maintain the retroviral envelope glycoprotein as a trimer. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39577– 39585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chernomordik L. V., Kozlov M. M. (2008) Mechanics of membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 675– 683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. White J. M., Delos S. E., Brecher M., Schornberg K. (2008) Structures and mechanisms of viral membrane fusion proteins: multiple variations on a common theme. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43, 189– 219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dimitrov D. S. (2004) Virus entry: molecular mechanisms and biomedical applications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 109– 122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weissenhorn W., Dessen A., Harrison S. C., Skehel J. J., Wiley D. C. (1997) Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature 387, 426– 430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clapham P. R., McKnight A. (2002) Cell surface receptors, virus entry and tropism of primate lentiviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 83, 1809– 1829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chan D. C., Kim P. S. (1998) HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell 93, 681– 684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Colman P. M., Lawrence M. C. (2003) The structural biology of type I viral membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4, 309– 319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nieva J. L., Nir S., Muga A., Goni F. M., Wilschut J. (1994) Interaction of the HIV-1 fusion peptide with phospholipid vesicles: different structural requirements for fusion and leakage. Biochemistry 33, 3201– 3209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dimitrov A. S., Rawat S. S., Jiang S., Blumenthal R. (2003) Role of the fusion peptide and membrane-proximal domain in HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein-mediated membrane fusion. Biochemistry 42, 14150– 14158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Melikyan G. B., Egelhofer M., von Laer D. (2006) Membrane-anchored inhibitory peptides capture human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 conformations that engage the target membrane prior to fusion. J. Virol. 80, 3249– 3258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chan D. C., Fass D., Berger J. M., Kim P. S. (1997) Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell 89, 263– 273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Skehel J. J., Wiley D. C. (1998) Coiled coils in both intracellular vesicle and viral membrane fusion. Cell 95, 871– 874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sollner T. H. (2004) Intracellular and viral membrane fusion: a uniting mechanism. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16, 429– 435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Suntoke T. R., Chan D. C. (2005) The fusion activity of HIV-1 gp41 depends on interhelical interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 19852– 19857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sia S. K., Carr P. A., Cochran A. G., Malashkevich V. N., Kim P. S. (2002) Short constrained peptides that inhibit HIV-1 entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99, 14664– 14669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kilgore N. R., Salzwedel K., Reddick M., Allaway G. P., Wild C. T. (2003) Direct evidence that C-peptide inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry bind to the gp41 N-helical domain in receptor-activated viral envelope. J. Virol. 77, 7669– 7672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Root M. J., Kay M. S., Kim P. S. (2001) Protein design of an HIV-1 entry inhibitor. Science 291, 884– 888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu S., Lu H., Niu J., Xu Y., Wu S., Jiang S. (2005) Different from the HIV fusion inhibitor C34, the anti-HIV drug Fuzeon (T-20) inhibits HIV-1 entry by targeting multiple sites in gp41 and gp120. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 11259– 11273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eckert D. M., Kim P. S. (2001) Design of potent inhibitors of HIV-1 entry from the gp41 N-peptide region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 11187– 11192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Burton A. (2003) Enfuvirtide approved for defusing HIV. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3, 260– 269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weiss A., Wiskocil R. L., Stobo J. D. (1984) The role of T3 surface molecules in the activation of human T cells: a two-stimulus requirement for IL 2 production reflects events occurring at a pre-translational level. J. Immunol. 133, 123– 128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cao J., Park I. W., Cooper A., Sodroski J. (1996) Molecular determinants of acute single-cell lysis by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 70, 1340– 1354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Merrifield R. B., Vizioli L. D., Boman H. G. (1982) Synthesis of the antibacterial peptide cecropin A (1–33). Biochemistry 21, 5020– 5031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wexler-Cohen Y., Shai Y. (2009) Membrane-anchored HIV-1 N-heptad repeat peptides are highly potent cell fusion inhibitors via an altered mode of action. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wexler-Cohen Y., Shai Y. (2007) Demonstrating the C-terminal boundary of the HIV 1 fusion conformation in a dynamic ongoing fusion process and implication for fusion inhibition. FASEB J. 21, 3677– 3684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bewley C. A., Louis J. M., Ghirlando R., Clore G. M. (2002) Design of a novel peptide inhibitor of HIV fusion that disrupts the internal trimeric coiled-coil of gp41. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 14238– 14245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yu H., Tudor D., Alfsen A., Labrosse B., Clavel F., Bomsel M. (2008) Peptide P5 (residues 628–683), comprising the entire membrane proximal region of HIV-1 gp41 and its calcium-binding site, is a potent inhibitor of HIV-1 infection. Retrovirology 5, 93– 105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. He Y., Cheng J., Li J., Qi Z., Lu H., Dong M., Jiang S., Dai Q. (2008) Identification of a critical motif for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) gp41 core structure: implications for designing novel anti-HIV fusion inhibitors. J. Virol. 82, 6349– 6358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Noah E., Biron Z., Naider F., Arshava B., Anglister J. (2008) The membrane proximal external region of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp41 contributes to the stabilization of the six-helix bundle formed with a matching N′ peptide. Biochemistry 47, 6782– 6792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bianchi E., Finotto M., Ingallinella P., Hrin R., Carella A. V., Hou X. S., Schleif W. A., Miller M. D., Geleziunas R., Pessi A. (2005) Covalent stabilization of coiled coils of the HIV gp41 N region yields extremely potent and broad inhibitors of viral infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 12903– 12908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yang X., Kurteva S., Ren X., Lee S., Sodroski J. (2006) Subunit stoichiometry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein trimers during virus entry into host cells. J. Virol. 80, 4388– 4395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brugger B., Krautkramer E., Tibroni N., Munte C. E., Rauch S., Leibrecht I., Glass B., Breuer S., Geyer M., Krausslich H. G., Kalbitzer H. R., Wieland F. T., Fackler O. T. (2007) Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef protein modulates the lipid composition of virions and host cell membrane microdomains. Retrovirology 4, 70– 82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alfsen A., Yu H., Magerus-Chatinet A., Schmitt A., Bomsel M. (2005) HIV-1-infected blood mononuclear cells form an integrin- and agrin-dependent viral synapse to induce efficient HIV-1 transcytosis across epithelial cell monolayer. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 4267– 4279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Louis J. M., Nesheiwat I., Chang L., Clore G. M., Bewley C. A. (2003) Covalent trimers of the internal N-terminal trimeric coiled-coil of gp41 and antibodies directed against them are potent inhibitors of HIV envelope-mediated cell fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 20278– 20285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wild C., Oas T., McDanal C., Bolognesi D., Matthews T. (1992) A synthetic peptide inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus replication: correlation between solution structure and viral inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89, 10537– 10541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]