Abstract

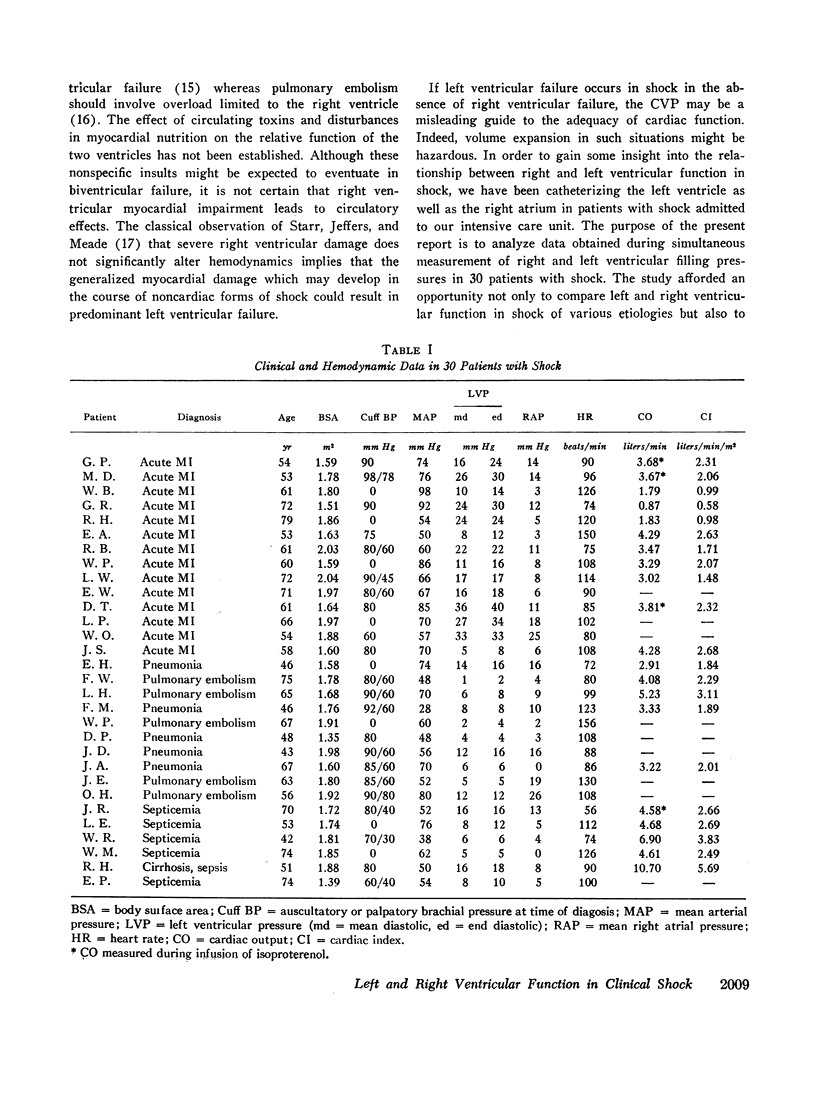

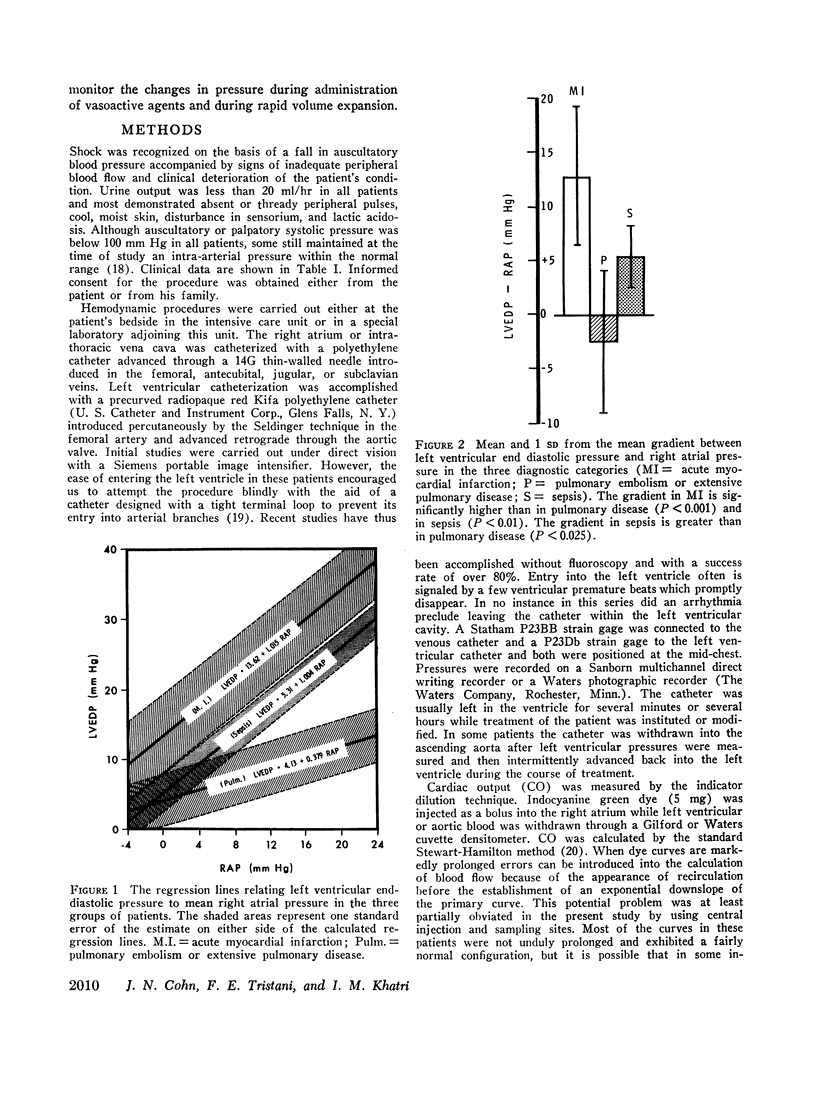

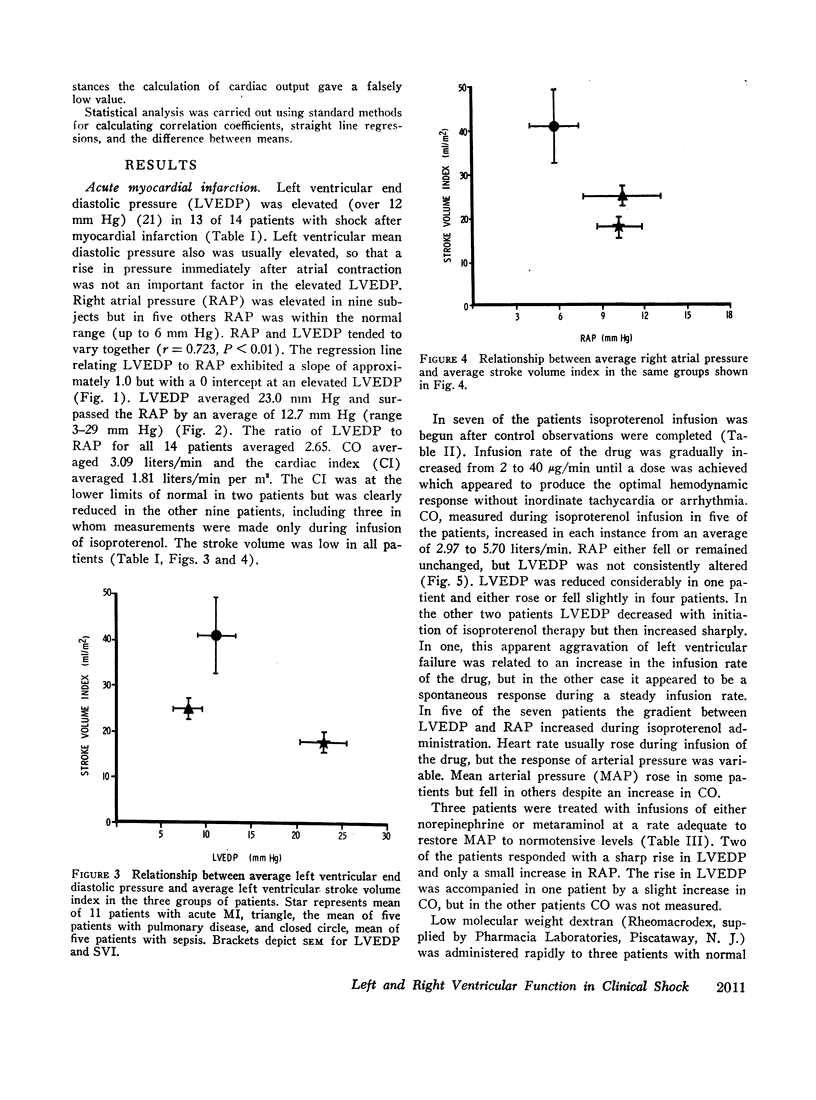

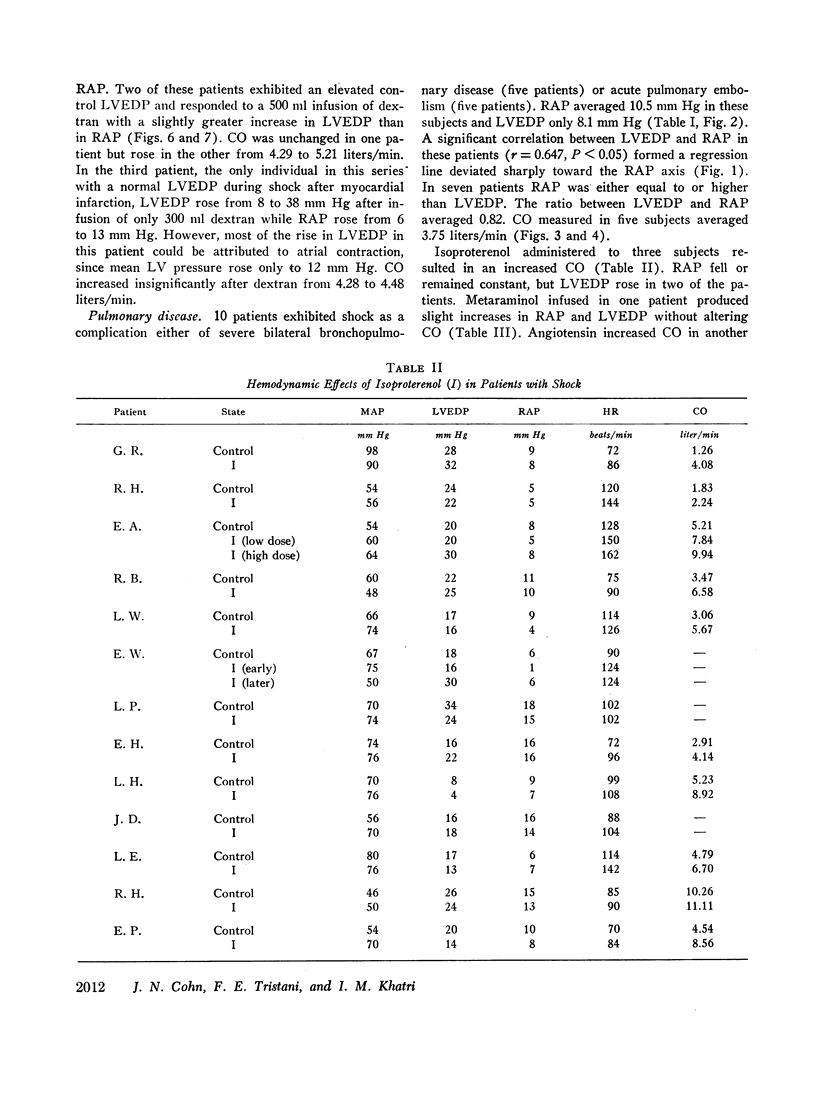

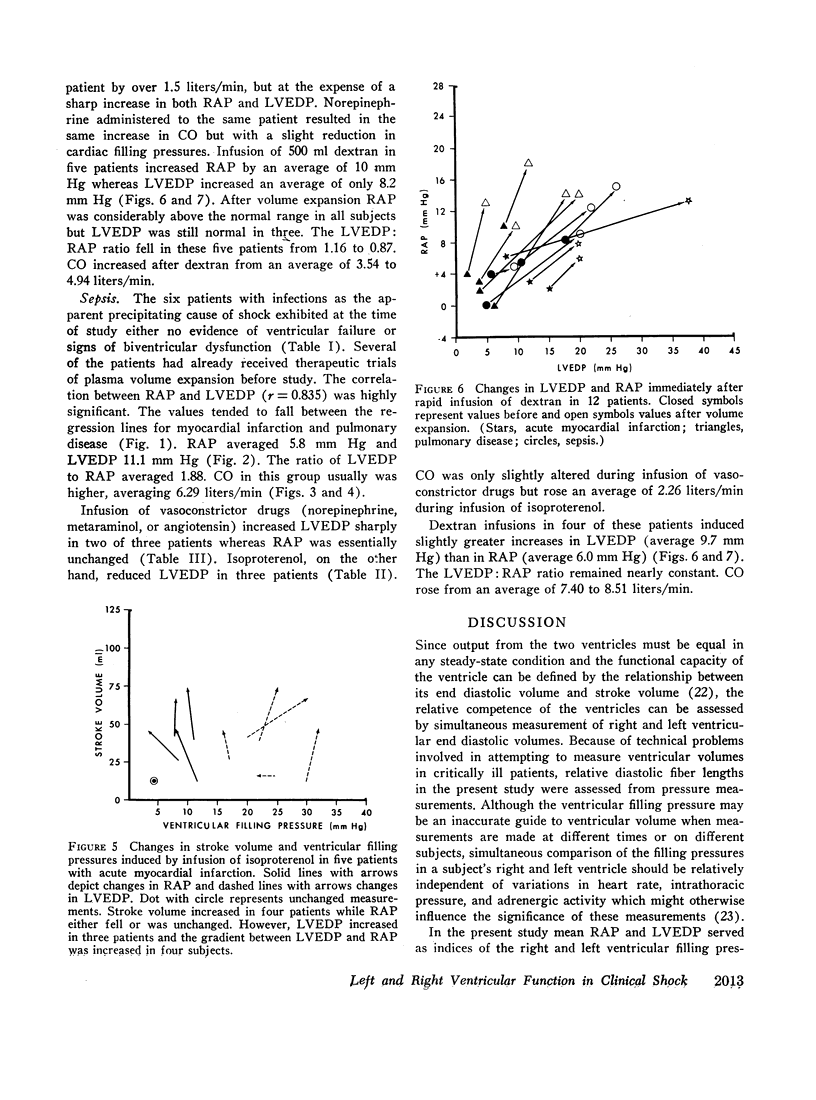

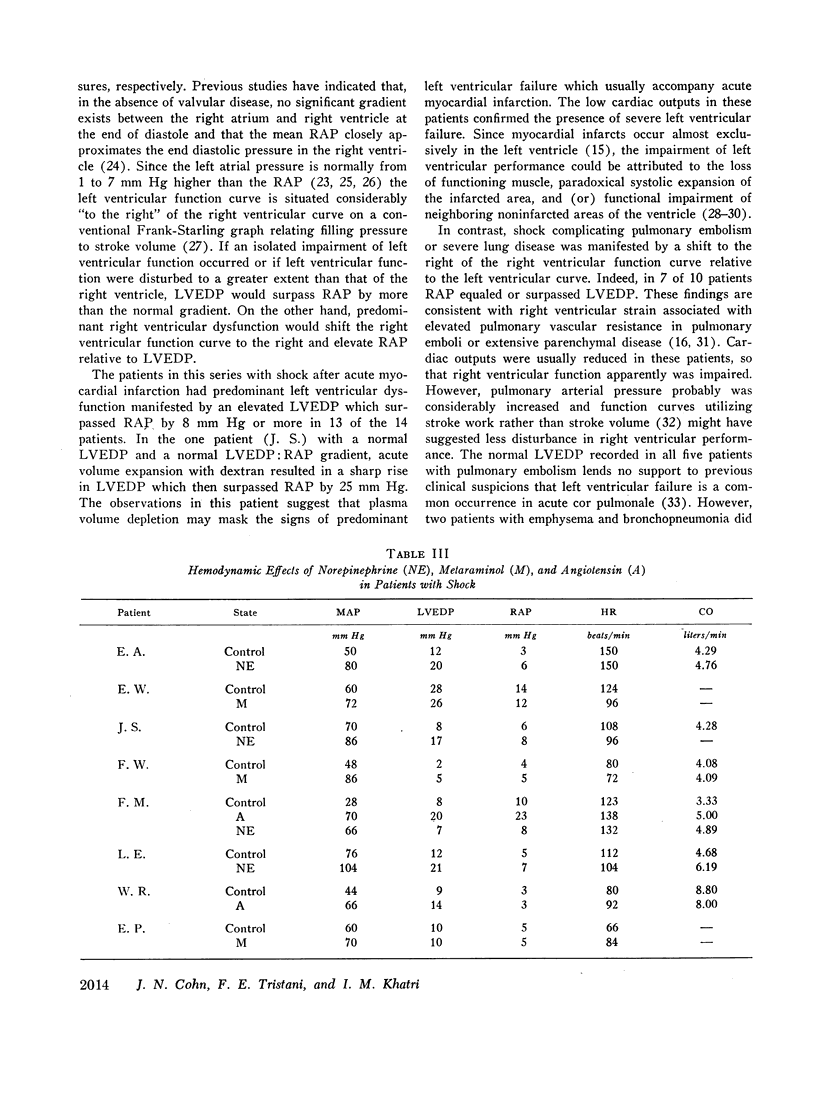

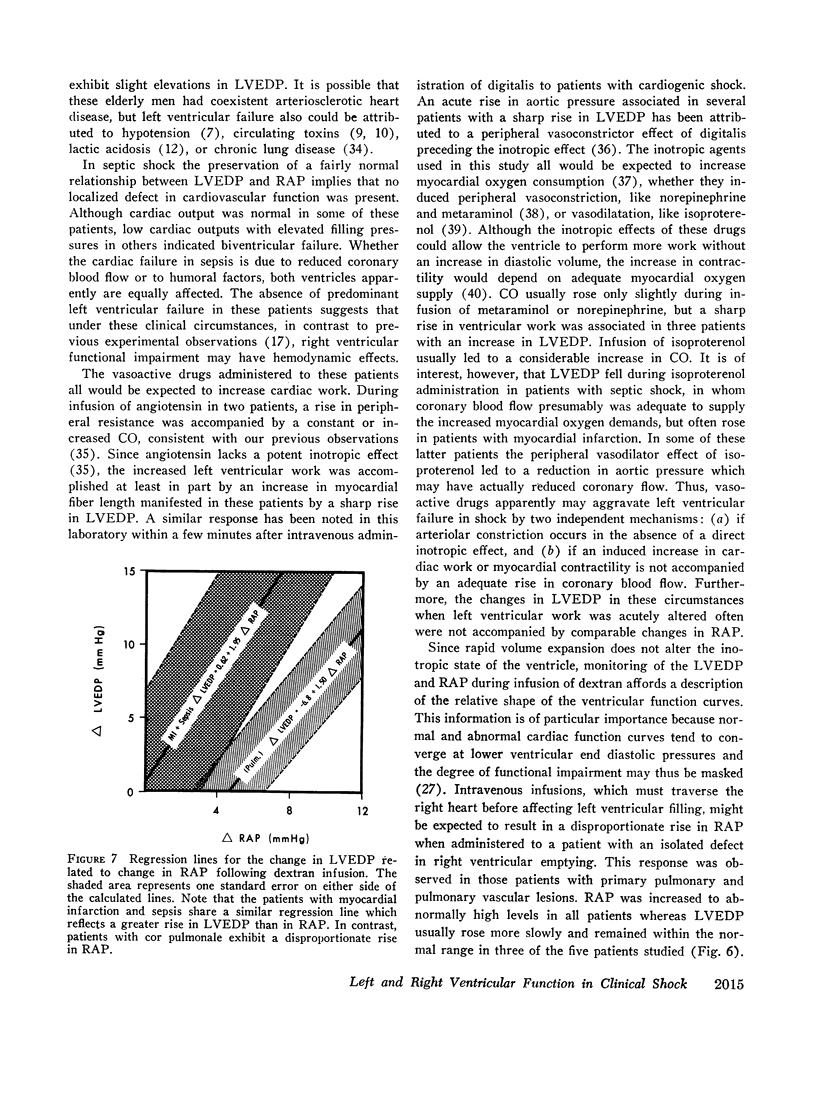

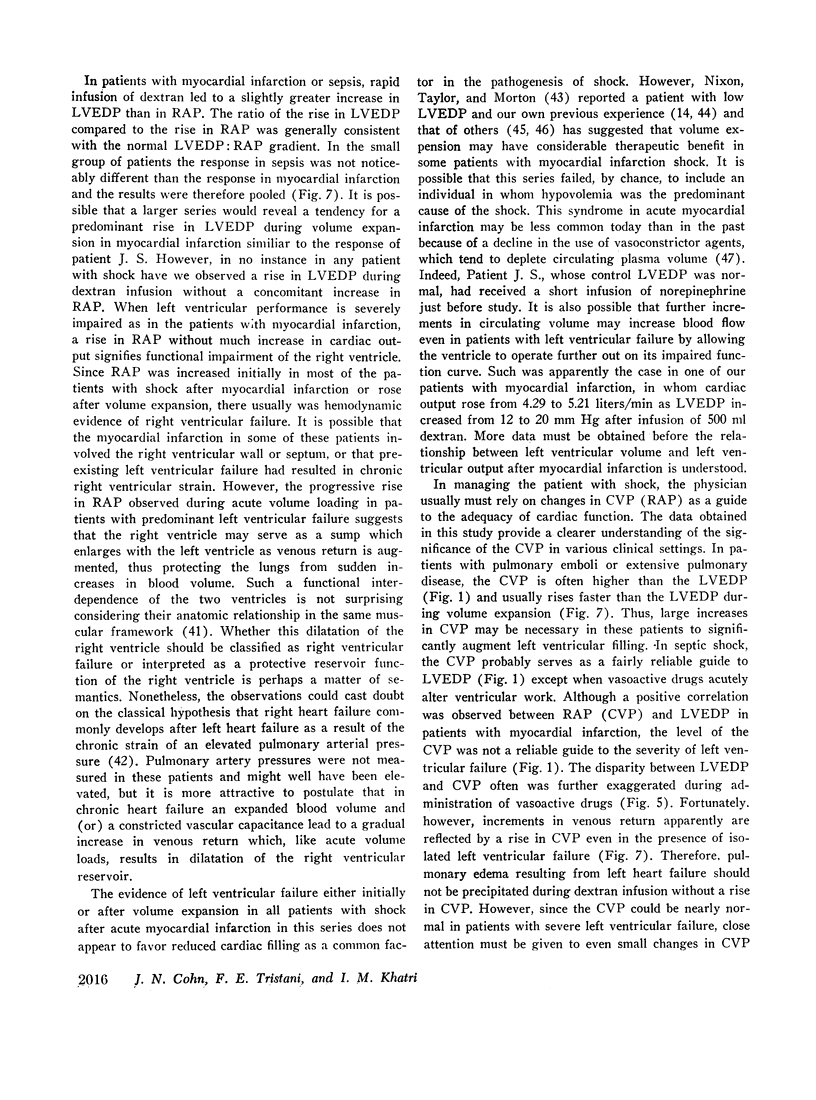

Left ventricular end diastolic (LVEDP) and mean right atrial (RAP) pressures were recorded simultaneously in 30 patients with shock (14 acute myocardial infarction, 10 acute pulmonary embolism or severe bronchopulmonary disease, and 6 sepsis). Myocardial infarction was characterized by a predominant increase in LVEDP, pulmonary disease by a predominant increase in RAP, and sepsis by a normal relationship between LVEDP and RAP. In all three groups a significant positive correlation was noted between RAP and LVEDP, with the regression line in cor pulmonale deviated significantly toward the RAP axis and the regression line in myocardial infarction exhibiting a zero RAP intercept at an elevated LVEDP.

Low cardiac outputs with elevated LVEDP in myocardial infarction indicated severe left ventricular failure. Low outputs with elevated RAP in cor pulmonale were consistent with right ventricular overload. Although cardiac outputs often were normal in sepsis, low outputs with elevated cardiac filling pressures in some patients were consistent with a hemodynamic or humoral-induced generalized depression of cardiac performance.

Vasoconstrictor and inotropic drugs often produced a functional disparity between the two ventricles, with the gradient between LVEDP and RAP increasing, apparently because of an increase in left ventricular work or an inadequacy of left ventricular oxygen delivery. Acute plasma volume expansion with dextran in patients with pulmonary vascular disease resulted in a somewhat more rapid rise in RAP than in LVEDP. In septic and myocardial infarction shock, however, LVEDP and RAP usually rose proportionally, with the absolute rise of LVEDP surpassing that of RAP. Although the absolute level of the central venous pressure thus may not be a reliable indicator of left ventricular function in shock, changes in venous pressure during acute plasma volume expansion should serve as a fairly safe guide to changes in LVEDP.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ALICAN F., DALTON M. L., Jr, HARDY J. D. Experimental endotoxin shock. Circulatory changes with emphasis upon cardiac function. Am J Surg. 1962 Jun;103:702–708. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(62)90249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGLUND E. Ventricular function. VI. Balance of left and right ventricular output: relation between left and right atrial pressures. Am J Physiol. 1954 Sep;178(3):381–386. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1954.178.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunwald E., Brockenbrough E. C., Frahm C. J., Ross J., Jr Left atrial and left ventricular pressures in subjects without cardiovascular disease: observations in eighteen patients studied by transseptal left heart catheterization. Circulation. 1961 Aug;24:267–269. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.24.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASE R. B., BERGLUND E., SARNOFF S. J. Ventricular function. II. Quantitative relationship between coronary flow and ventricular function with observations on unilateral failure. Circ Res. 1954 Jul;2(4):319–325. doi: 10.1161/01.res.2.4.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COHN J. N., LURIA M. H. STUDIES IN CLINICAL SHOCK AND HYPOTENSION. II. HEMODYNAMIC EFFECTS OF NOREPINEPHRINE AND ANGIOTENSIN. J Clin Invest. 1965 Sep;44:1494–1504. doi: 10.1172/JCI105256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COHN J. N., LURIA M. H. STUDIES IN CLINICAL SHOCK AND HYPOTENSION; THE VALUE OF BEDSIDE HEMODYNAMIC OBSERVATIONS. JAMA. 1964 Dec 7;190:891–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROWELL J. W., GUYTON A. C. Further evidence favoring a cardiac mechanism in irreversible hemorrhagic shock. Am J Physiol. 1962 Aug;203:248–252. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1962.203.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn J. N. Central venous pressure as a guide to volume expansion. Ann Intern Med. 1967 Jun;66(6):1283–1287. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-66-6-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn J. N., Luria M. H., Daddario R. C., Tristani F. E. Studies in clinical shock and hypotension. V. Hemodynamic effects of dextran. Circulation. 1967 Feb;35(2):316–326. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.35.2.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn J. N. Relationship of plasma volume changes to resistance and capacitance vessel effects of sympathomimetic amines and angiotensin in man. Clin Sci. 1966 Apr;30(2):267–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn J. N., Tristani F. E., Khatri I. M. Cardiac and peripheral vascular effects of digitalis in clinical cardiogenic shock. Am Heart J. 1969 Sep;78(3):318–330. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(69)90039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEXTER L., DOCK D. S., McGUIRE L. B., HYLAND J. W., HAYNES F. W. Pulmonary embolism. Med Clin North Am. 1960 Sep;44:1251–1268. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)33960-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniell H. B., Bagwell E. E., Walton R. P. Limitation of myocardial function by reduced coronary blood flow during isoproterenol action. Circ Res. 1967 Jul;21(1):85–98. doi: 10.1161/01.res.21.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOWLER N. O., WESTCOTT R. N., SCOTT R. C. Normal pressure in the right heart and pulmonary artery. Am Heart J. 1953 Aug;46(2):264–267. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(53)90205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOMEZ O. A., HAMILTON W. F. FUNCTIONAL CARDIAC DETERIORATION DURING DEVELOPMENT OF HEMORRHAGIC CIRCULATORY DEFICIENCY. Circ Res. 1964 Apr;14:327–336. doi: 10.1161/01.res.14.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar R. M., Cruz A., Boswell J., Co B. S., Pietras R. J., Tobin J. R., Jr Myocardial infarction with shock. Hemodynamic studies and results of therapy. Circulation. 1966 May;33(5):753–762. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.33.5.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARVEY R. M., FERRER M. I., RICHARDS D. W., Jr, COURNAND A. Influence of chronic pulmonary disease on the heart and circulation. Am J Med. 1951 Jun;10(6):719–738. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(51)90340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimbecker R. O., Chen C., Hamilton N., Murray D. W. Surgery for massive myocardial infarction. An experimental study of emergency infarctectomy. Surgery. 1967 Jan;61(1):51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRASNOW N., ROLETT E. L., YURCHAK P. M., HOOD W. B., Jr, GORLIN R. ISOPROTERENOL AND CARDIOVASCULAR PERFORMANCE. Am J Med. 1964 Oct;37:514–525. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(64)90065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefer A. M., Cowgill R., Marshall F. F., Hall L. M., Brand E. D. Characterization of a myocardial depressant factor present in hemorrhagic shock. Am J Physiol. 1967 Aug;213(2):492–498. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1967.213.2.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon P. G., Ikram H., Morton S. Infusion of dextrose solution in cardiogenic shock. Lancet. 1966 May 14;1(7446):1077–1079. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)91016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon P. G., Taylor D. J., Morton S. D. Left ventricular diastolic pressure in cardiogenic shock treated by dextrose infusion and adrenaline. Lancet. 1968 Jun 8;1(7554):1230–1232. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)91925-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson S. W., Piper H., Starling E. H. The regulation of the heart beat. J Physiol. 1914 Oct 23;48(6):465–513. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1914.sp001676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao B. S., Cohn K. E., Eldridge F. L., Hancock E. W. Left ventricular failure secondary to chronic pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 1968 Aug;45(2):229–241. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(68)90041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARNOFF S. J., BRAUNWALD E., WELCH G. H., Jr, CASE R. B., STAINSBY W. N., MACRUZ R. Hemodynamic determinants of oxygen consumption of the heart with special reference to the tension-time index. Am J Physiol. 1958 Jan;192(1):148–156. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1957.192.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARNOFF S. J., CASE R. B., WAITHE P. E., ISAACS J. P. Insufficient coronary flow and myocardial failure as a complication factor in late hemorrhagic shock. Am J Physiol. 1954 Mar;176(3):439–444. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1954.176.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasahara A. A., Sidd J. J., Tremblay G., Leland O. S., Jr Cardiopulmonary consequences of acute pulmonary embolic disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1966 Nov;9(3):259–274. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(66)80027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenblick E. H., Ross J., Jr, Covell J. W., Kaiser G. A., Braunwald E. Velocity of contraction as a determinant of myocardial oxygen consumption. Am J Physiol. 1965 Nov;209(5):919–927. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1965.209.5.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starzecki B., Spink W. Hemodynamic effects of isoproterenol in canine endotoxin shock. J Clin Invest. 1968 Oct;47(10):2193–2205. doi: 10.1172/JCI105905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THROWER W. B., DARBY T. D., ALDINGER E. E. Acid-base derangements and myocardial contractility. Effects as a complication of shock. Arch Surg. 1961 Jan;82:56–65. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1961.01300070060008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildenthal K., Mierzwiak D. S., Myers R. W., Mitchell J. H. Effects of acute lactic acidosis on left ventricular performance. Am J Physiol. 1968 Jun;214(6):1352–1359. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1968.214.6.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]