Abstract

Epidemiological studies have reported that coffee and/or caffeine consumption may reduce Alzheimer's disease (AD) risk. We found that coffee extracts can similarly protect against β-amyloid peptide (Aβ) toxicity in a transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans Alzheimer's disease model. The primary protective component(s) in this model is not caffeine, although caffeine by itself can show moderate protection. Coffee exposure did not decrease Aβ transgene expression and did not need to be present during Aβ induction to convey protection, suggesting that coffee exposure protection might act by activating a protective pathway. By screening the effects of coffee on a series of transgenic C. elegans stress reporter strains, we identified activation of the skn-1 (Nrf2 in mammals) transcription factor as a potential mechanism of coffee extract protection. Inactivation of skn-1 genetically or by RNAi strongly blocked the protective effects of coffee extract, indicating that activation of the skn-1 pathway was the primary mechanism of coffee protection. Coffee also protected against toxicity resulting from an aggregating form of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in a skn-1–dependent manner. These results suggest that the reported protective effects of coffee in multiple neurodegenerative diseases may result from a general activation of the Nrf2 phase II detoxification pathway.

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL studies have indicated that coffee consumption may be protective in Alzheimer's (AD) (Barranco Quintana et al. 2007) and Parkinson's diseases (PD) (Hu et al. 2007). Although a universal consensus on the cause(s) of Alzheimer's disease has not been reached, the best-supported hypotheses posit that accumulation of the β-amyloid peptide (Aβ) is central to the induction of Alzheimer's disease pathology. The strongest evidence for this claim is the identification of germ line mutations in the gene encoding amyloid precursor protein (APP), (Chartier-Harlin et al. 1991; Murrell et al. 1991), or in the presenilin genes involved in cleaving Aβ from APP (reviewed in Cruts et al. 1996) in familial cases of early-onset AD. The pathological similarities between familial and sporadic AD, along with the results of many studies of transgenic mice engineered to overexpress Aβ in the brain, argue for a causal role of Aβ accumulation in all forms of AD. Intramuscular accumulation of Aβ is also observed in inclusion body myositis (IBM), a severe myopathy that can be phenocopied by overexpression of APP in transgenic mice (Sugarman et al. 2002).

Models of Aβ toxicity can potentially be used to investigate the biological mechanisms underlying the protective effects of coffee consumption in Alzheimer's disease. In this context, caffeine administration has been reported to reverse cognitive impairment and amyloid β (Aβ) levels in transgenic Alzheimer's disease model mice (Arendash et al. 2009). To examine the protective effects of coffee in a genetically tractable model, we investigated the effects of aqueous coffee extracts in a C. elegans model of Aβ toxicity (Link et al. 2003). In this model, temperature upshift induces expression of human Aβ42 in body wall muscle. This induction of Aβ42 leads to a highly reproducible paralysis phenotype, in which all induced animals become paralyzed within 28 hr of temperature upshift. This model has previously been used to investigate gene expression changes in response to Aβ accumulation (Link et al. 2003) and the role of specific genes (Fonte et al. 2008; Hassan et al. 2009) and autophagy (Florez- McClure et al. 2007) in countering Aβ toxicity. Here we employ this model to investigate candidate genes and pathways that might play a significant role in the protective effects of coffee.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. elegans strains used in this study:

CL4176 smg-1(cc546) I; dvIs27 [pAF29 (Pmyo-3∷Aβ42) + pRF4] X

SJ4006 zcIs4(Phsp-4∷GFP) V

CL685 ldIs001(skn-1∷GFP)

CL6176 smg-1(cc546) I; dvIs19(Pgst-4∷GFP) III; +/nT1(unc d;let-? IV;V); dvIs27 [pAF29 (Pmyo-3∷Aβ42) + pRF4] X

CL6180 smg-1(cc546) I; dvIs19(Pgst-4∷GFP) III; skn-1(zu67) IV/nT1(unc d;let-? IV;V); dvIs27 [pAF29 (Pmyo-3∷Aβ42) + pRF4] X

CL6222 smg-1(cc546) I; dvIs19(Pgst-4∷GFP) III; skn-1(zu169) IV/nT1(unc d;let? IV;V); dvIs27 [pAF29 (Pmyo-3∷Aβ42) + pRF4] X

CL2337 smg-1(cc546) I; dvIs38 [pCL60 (Pmyo-3∷GFP∷degron/long 3′ UTR) + pRF4].

Coffee extract preparation:

We employed an aqueous extraction protocol originally developed in the Pallanck lab (Trinh et al. 2010). Coffee beans (Starbucks House Blend, caffeinated or decaffeinated) were ground for 3 min in a standard coffee grinder, and then an 18.4% (w/v) slurry of grounds in deionized water was boiled for 30 min before removing grounds with a French press. Extracts were filter sterilized by passage through a Nalgene Fast PES Filter Unit, a 75-mm diameter membrane (0.2 μm pore size), and stored a 2°.

Media preparation:

Small (5.7 cm) Petri plates containing 10 ml nematode growth media agar (Wood 1988) were supplemented with coffee extract or purified caffeine (Sigma) after agar was solidified and allowed to diffuse throughout the agar before addition of bacteria. Caffeine concentrations were based on the caffeine concentration reported for Starbucks caffeinated drip coffee or from direct mass spectroscopy measurements of decaffeinated coffee extracts (Trinh et al. 2010). Plates were spotted with Escherichia coli strain OP50 or, for feeding RNAi, strain HT115 transformed with a skn-1 dsRNA-expressing plasmid or vector-only control (Kamath et al. 2003). In all experiments worms were exposed from hatching to the coffee extracts or caffeine.

Quantification of paralysis kinetics:

Staged populations of CL4176, CL6176, CL6180, CL6222, or CL2337 transgenic worms were prepared by synchronous egg lay and induced to express Aβ as third-stage larvae by upshift from 16° to 25° as previously described (Link et al. 2003). All paralysis plots were done in triplicate with an average of 129 worms per strain and condition. Plots shown in Figures 1 and 4–7 are representative; all experiments were independently replicated (see supporting information, Table S1). Statistical analysis of paralysis curves was performed using a paired log rank survival test (Peto and Peto 1972) implemented in Statistica.

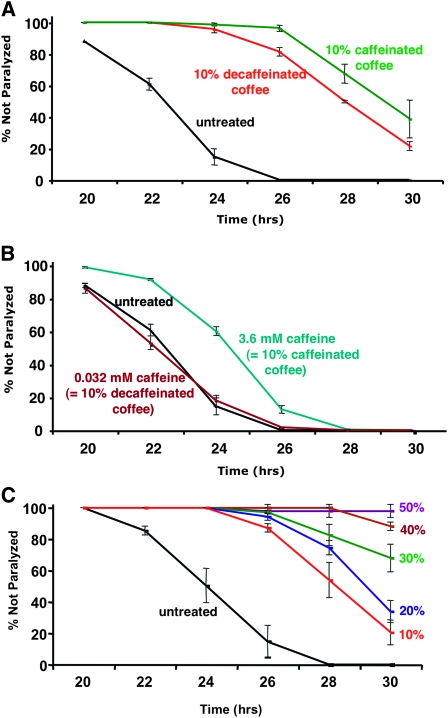

Figure 1.—

Effects of coffee extracts and caffeine on paralysis in inducible Aβ expression strain CL4176 (Pmyo-3∷Aβ42). Time refers to hours after Aβ expression was induced by temperature upshift. (A) Incorporation of 10% caffeinated or decaffeinated coffee extract into agar media plates suppresses paralysis (control vs. caffeinated or decaffeinated coffee, P < 0.001; decaffeinated coffee vs. caffeinated coffee, P < 0.02, paired log rank survival test). (B) Incorporation of pure caffeine into agar media plates can also slow induced paralysis, but this effect is weaker than that of decaffeinated coffee. (This experiment was done in parallel with that shown in A; separate plots are presented for clarity.) (C) Dose response paralysis curves for agar media containing 0–50% coffee extract. Error bars = SEM.

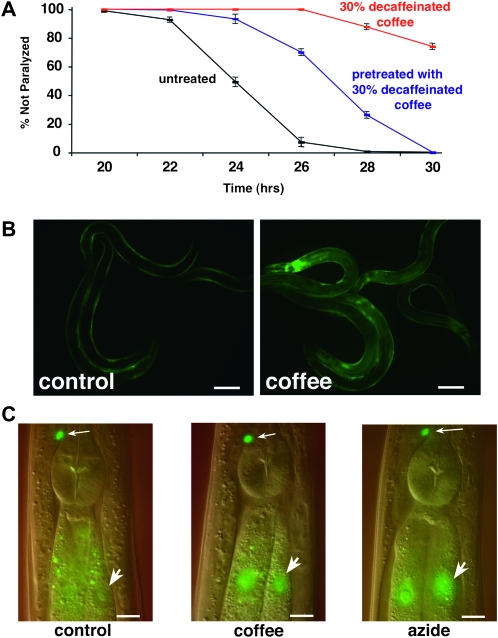

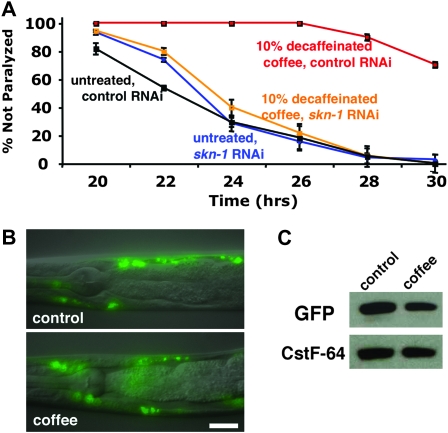

Figure 4.—

Coffee extract exposure induces the skn-1 detoxification pathway. (A) CL4176 (Pmyo-3∷Aβ42) worms were propagated from hatching to third larval stage (48 hr) on agar media plates containing 30% decaffeinated coffee, either moved to control media or maintained on 30% decaffeinated coffee plates, and then induced to express Aβ42. Note that significant protection against paralysis is observed even in worms shifted to control plates before induction of Aβ42 expression (P < 0.001, paired log rank survival test). (B) CL2166 (Pgst-4∷GFP) worms were propagated from hatching to adulthood on control or 10% decaffeinated coffee plates. Coffee extract exposure induces strong upregulation of the gst-4∷GFP reporter, particularly in the intestine. This induction requires the skn-1 transcription factor (data not shown). Bar, 100 μm. (C) Worms containing transgene ldIs001(skn-1∷GFP) were propagated from hatching on control and 10% decaffeinated coffee plates. The translational fusion protein expressed by this transgene is expressed in the ASI neurons (small arrows) and the intestine. Propagation on coffee extract plates causes nuclear localization of the fusion protein (large arrow) similar to what is observed if this reporter strain is exposed to 100 mM sodium azide for 1 hr (right). Digitally fused DIC/epifluorescence images. Bar, 10 μm.

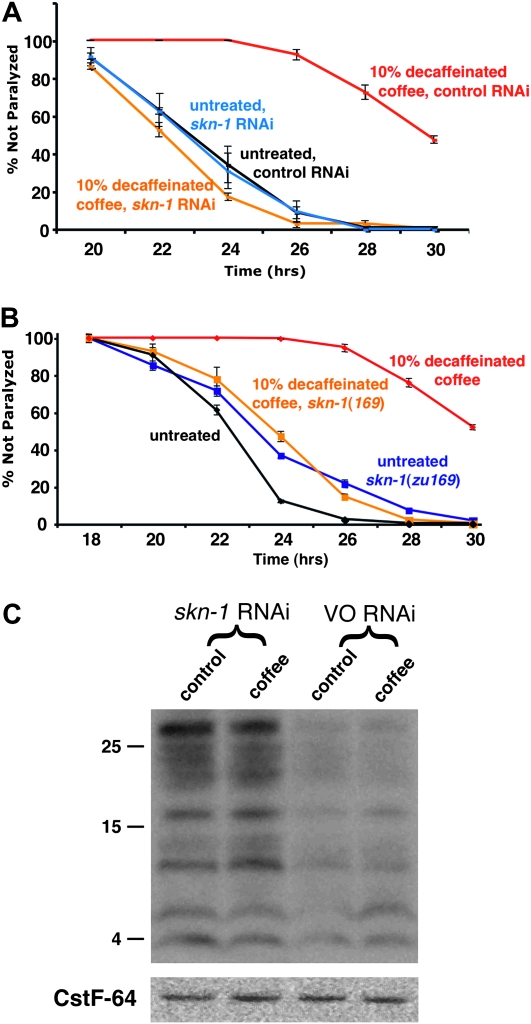

Figure 5.—

SKN-1 is required for coffee extract protection against Aβ42-induced paralysis. (A) CL4176 worms were propagated on control or 10% decaffeinated coffee plates seeded with E. coli expressing control (vector only) or skn-1 dsRNA. Coffee extract exposure produces strong protection in worms propagated on the control RNAi strain (black vs. red lines), but not in worms propagated on skn-1 RNAi (blue vs. orange lines). (B) Aβ42 transgenic worms homozygous for the skn-1(zu169) (segregated from CL6222) allele show no coffee extract protection (blue vs. orange lines), while +/+ worms (segregated from control strain CL6176) also containing the nT1 balancer chromosome) are strongly protected (black vs. red lines). (C) CL4176 (Pmyo-3/Aβ42) worms propagated control or 10% coffee plates exposed to skn-1 or control (VO, vector only) RNAi were induced for 24 hr and 20 μg total protein was run on an immunoblot and probed with anti-Aβ monoclonal antibody 6E10. Note increased accumulation of Aβ on both control and coffee plates in worms treated with skn-1 RNAi. (Blot reprobed with anti-CstF-64 antibody to demonstrate equal lane loading.)

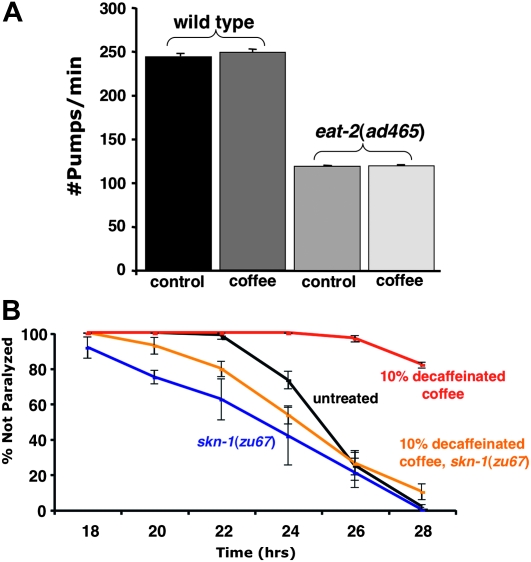

Figure 6.—

Coffee extract protection is not explained by reduction in feeding and subsequent induction of a dietary restriction response. (A) Pharyngeal pumps per minute were determined for fourth larval stage wild-type and eat-2(ad465) worms propagated on control or 10% decaffeinated coffee plates. Coffee extract exposure does not affect pharyngeal pumping rates under a Student's t-test analysis (P = 0.806). Furthermore, coffee extract has no effect on pumping rates while controlling for strain (N = 30 for each strain/condition), as per a two-way ANOVA (P = 0.304). (B) Coffee extract protection is blocked by a skn-1 mutation that does not block the effects of dietary restriction on life span. Aβ42 transgenic worms homozygous for the skn-1(zu67) allele show no coffee extract protection (blue vs. orange lines), while +/+ worms (segregated from control strain CL6176 also containing the nT1 balancer chromosome) are strongly protected (black vs. red lines). Error bars = SEM.

Figure 7.—

Coffee extract exposure protects against GFP∷degron toxicity in a skn-1–dependent manner. (A) CL2337 (Pmyo-3∷GFP∷degron) worms were propagated on control or 10% decaffeinated coffee plates seeded with E. coli expressing control (vector only) or skn-1 dsRNA. Induction of GFP∷degron expression also results in paralysis (Link et al. 2006). Coffee extract exposure produces strong protection in worms propagated on the control RNAi strain (black vs. red lines, P < 0.001, paired log rank survival test), but not in worms propagated on skn-1 RNAi (blue vs. orange lines). (B) Fused DIC/epifluorescence image of GFP∷degron worms propagated on control or 10% decaffeinated coffee plates. Distribution or size of the GFP∷degron deposits was not detectably altered by coffee exposure. Bar, 20 μm. (C) Immunoblot assaying GFP∷degron accumulation in worms propagated on control or 10% decaffeinated coffee plates. Equal gel loading was confirmed by reprobing the blot with antibody against CstF64, a slicing factor unlikely to be influenced by coffee exposure.

Feeding RNAi interference knockdown of skn-1:

skn-1 expression was knocked down by feeding RNAi interference using the corresponding E. coli from the Ahringer RNAi feeding library (clone verified by DNA sequencing). Using standard RNAi feeding protocols (Kamath et al. 2003) we observed that one generation of exposure to the skn-1 RNAi clone was insufficient to induce the 100% embryonic lethality phenotype observed for skn-1(zu169) homozygotes. We therefore developed a two-generation RNAi exposure protocol in which third larval stage worms were placed on the skn-1 (or control vector only, VO) RNAi plates and allowed to grow until the second day of adulthood at 16°. These treated adults were then used for a synchronous egg lay on RNAi plates to generate populations for paralysis quantitation after upshift. Under these conditions, control populations that were not upshifted grew to adulthood but laid 100% dead eggs.

Microscopy:

DIC and epifluorescence images were acquired on a Zeiss Axiophot compound microscope equipped with a computer-controlled Z-drive and software from Intelligent Imaging Innovations. Photoshop software (Adobe) was used to globally adjust brightness and contrast of digital images and to fuse DIC and epifluorescence images (Figures 4C and 7B).

Quantification of Pgst-4∷GFP expression:

Eggs of CL2166 were collected by hypochlorite, hatched overnight at 16°, and first-stage larvae (L1s) were placed onto NGM or 10% decaffeinated coffee plates and allowed to grow to L4 stage at 16°. Worms were harvested 1000 worms/ml in 1X S-Basal, and sorted using COPAS Biosort 250 Worm Sorter (Union Biometrica Inc., Harvard Biosciences). Length, optical absorbance, and integrated fluorescence intensity at 488 nm (GFP) were factors in the worm sorting. A total of 100 worms were sorted per condition. All sorting was done at room temperature.

Quantitative RT–PCR:

Aβ mRNA levels were quantified as previously described (Link et al. 2003) using an ABI Prism 7000 thermocycler using a TM of 55° and the following primers: forward primer 5′ CTTTCTGGCACCAGCAGGTAC and reverse primer 5′ CTTGCAGACTTCTCGCTGCTAG.

Aβ mRNA levels were normalized to reference genes cdc-42, pmp-3, and Y45F10D.4 as described in Hoogewijs et al. (2008).

Immunoblotting:

Worms were harvested in deionized water with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, P 2714) added, and then snap frozen. Worms were boiled in sample buffer (1X protease inhibitor cocktail, 62 mm Tris pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 4% BME) for 10 min, put on ice, and then centrifuged 1 min at 14,000 g. Supernatant was quantitated via Bradford assay (Pierce, 23238).

Just before loading, samples were boiled for 5 min in sample buffer with dye (62 mm Tris pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 4% BME, 0.0005% BPB). Samples were run at 180 V on Nu PAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Gel (Invitrogen, NP0321) using MES SDS Running Buffer (Invitrogen NP0002). ECL DualVue Western markers (GE Healthcare, RPN810) were used as size reference. Gel was transferred to 0.45 μm supported nitrocellulose (GE Osmonics, WP4HY00010) using 20% methanol, 39 mm glycine, and 48 mm Tris base. Transfer conditions were 21 V, 108 min.

Blots were visualized by Pouceau stain and then boiled for 3 min in PBS. Blots were blocked in TBS-Tween + 5% milk (100 mm Tris 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20). Aβ was detected with 6E10 (Covance, SIG-39320) at 1 μg/ml; secondary anti-mouse IgG peroxidase conjugate (Sigma, A5906). GFP was probed with 11E5 (Quantum Biotechnologies, AFP5001) at 0.5 μg/ml; secondary anti-mouse IgG (same as above). After stripping, blots were probed with CTSF64 (gift of Blumenthal Lab) at 1/7500; secondary antibody anti-rabbit IgG peroxidase conjugate (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, 211-032-171). Secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies were developed in ECL Plus (Amersham, RPN2132). CstF-64 immunoreactivity was used as an internal control for immunoblots because preliminary experiments indicated that accumulation of actin, a more commonly used internal control, was actually altered by loss of skn-1 activity.

RESULTS

Coffee extracts delay paralysis induced by Aβ expression:

We found that addition of coffee extract to the agar media (10% extract, vol/vol) used to propagate C. elegans significantly delayed the onset of paralysis in worms induced to express Aβ42 (Figure 1A). Suppression of paralysis was observed with extracts from both caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee, with caffeinated coffee having a slightly stronger effect (P < 0.02, paired log rank survival test). Addition of pure caffeine at a concentration equivalent to that found in caffeinated coffee had a moderate effect, and addition of caffeine at the concentration present in the decaffeinated coffee extract showed no protection (Figure 1B). We conclude that most of the protective effect is from coffee components other than caffeine, although caffeine may also contribute. The protective effects of decaffeinated coffee was also dose dependent (Figure 1C).

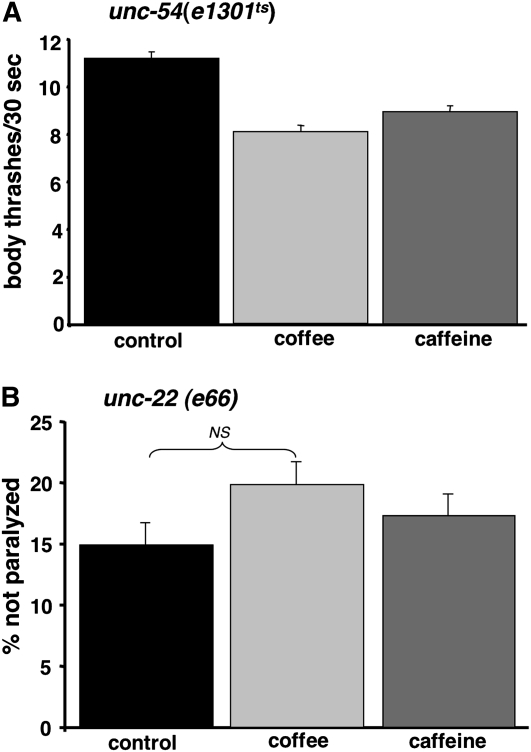

To investigate whether the reduced paralysis rates resulting from coffee extract or caffeine exposure might be due to a general effect on C. elegans movement or muscle function, we assayed extract effects on two well-characterized mutants with a partial paralysis phenotype, unc-54(e1301ts) and unc-22(e66). (unc-54 encodes a myosin protein expressed in body wall muscle, while unc-22 encodes twitchin, a large sarcomere-associated protein homologous to mammalian titin.) Movement of unc-54(e1301ts) was assayed by counting body thrashes in liquid for 30-sec intervals. At the nonpermissive temperature (25°), the thrashing rate of unc-54(e1301ts) was ∼10% of wild-type animals (11.2 thrashes/30 sec for unc-54(e1301ts) vs. 105.0 thrashes/30 sec for wild-type strain N2) when these worms were propagated on standard media. As shown in Figure 2A, thrashing rates of unc-54(e1301ts) were actually slightly reduced by propagation on 10% decaffeinated coffee or 3.6 mm caffeine, indicating that these treatments do not improve the movement of this strain. unc-22 mutants have a spontaneous “twitcher” phenotype; at 25° the majority of the unc-22(e66) mutant worms have a more severe paralysis phenotype. As shown in Figure 2B, propagation on 10% decaffeinated coffee or 3.6 mm caffeine did not significantly reduce the fraction of paralyzed unc-22(e66) worms.

Figure 2.—

Effect of coffee extracts and caffeine on control mutants with movement defects. (A) Rate of body thrashing in liquid for unc-54(e1301ts) mutant raised at 25° on agar media plates. Decaffeinated coffee extract (10%) and caffeine (3.6 mm) do not improve movement of this mutant and actually caused small but statistically significant reductions in thrashing (control plates, 11.2 thrashes/30 sec; coffee plates, 8.1 thrashes/30 sec; caffeine plates, 8.9 thrashes/30 sec; P < 0.0001 calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test). (B) Fraction unparalyzed unc-22(e66) mutant worms after propagation at 25° on control, 10% coffee extract, or 3.6 mm caffeine agar media plates. Neither coffee extract nor caffeine significantly increase the fraction of unparalyzed unc-22 mutant worms (χ2, P = 0.5, treatment vs. paralyzed/nonparalyzed). Error bars = SEM.

We also examined whether decaffeinated coffee could reduce neuronal cell loss induced by a dominant mutation [mec-4(u231)] in the MEC-4 sodium channel. This mutation induces necrotic neuronal cell death by causing excessive ion influx, resulting in vacuoles visible by DIC microscopy. To enhance scoring of mec-4(u231)-induced vacuoles, we used a strain containing additional mutations [ced-5(n1815) and ced-7(n1892)] that block cell corpse removal and increase the persistence of vacuoles (Chung et al. 2000). Propagation on 10% decaffeinated coffee did not significantly reduce the fraction of staged ced-7(n1892); ced-5(n1815); mec-4(u231) worms displaying vacuoles (88/100 on control media, 85/100 on 10% decaffeinated coffee, exact χ2, P = 0.34).

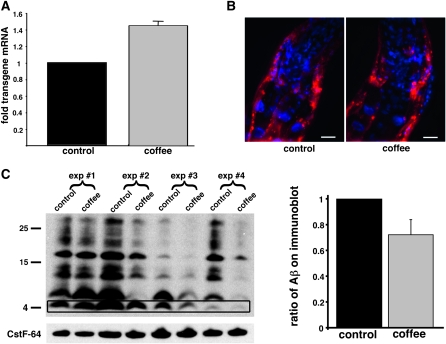

Coffee extracts do not reduce Aβ transgene expression:

To determine whether coffee extract might trivially slow Aβ-induced paralysis by reducing expression of the Aβ transgene, quantitative RT–PCR was used to assay Aβ mRNA levels and anti-Aβ antibody (monoclonal 6E10) was used to monitor Aβ peptide accumulation. Both coffee-treated and control worms were harvested 24 hr after Aβ induction, and parallel populations were processed for quantitative RT–PCR, immunohistochemistry, and immunoblots. As shown in Figure 3A, Aβ transcript levels were actually slightly higher (∼1.4-fold) in coffee-treated worms than in the controls. (This increase in Aβ transcript levels in coffee-treated worms may be due to the improved robustness of these animals at time of harvest.) No qualitative difference in the accumulation or distribution of large Aβ deposits was observed between treated and control worms as assayed by whole-animal immunohistochemistry (Figure 3B). However, coffee treatment did result in a variable reduction in total Aβ levels as assayed by immunoblot (Figure 3C). The average reduction in Aβ accumulation induced by coffee exposure was ∼25% when averaged over four biologically independent experiments.

Figure 3.—

Effect of coffee extract treatment on Aβ transgene expression and Aβ accumulation. (A) Quantitative RT–PCR of measurement of Aβ mRNA levels 24 hr after induction of CL4176 transgenic worms propagated on control or 10% coffee extract plates, average of three biologically independent experiments. (B) Anti-Aβ immunohistochemistry of anterior region of CL4176 worms induced for 24 hr after propagation on control or 10% decaffeinated coffee plates. Aβ immunoreactivity, red; DAPI counterstain, blue. Bar, 10 μm. (C) Immunoblot assay of Aβ accumulation 24 hr after upshift of CL4176 grown on control or 10% coffee extract plates. Left, visualization of monomeric (4 kDa band, boxed) and multimeric (higher molecular weight species) Aβ recovered from CL4176 worms induced for 24 hr after propagation on control or 10% decaffeinated coffee plates. Shown are total protein preparations (20 μg/lane) from four biologically independent experiments fractionated on a 4–12% polyacrylamide SDS gel and probed with anti-Aβ monoclonal antibody 6E10. The gel blot was reprobed with antibody against CstF-64 (Evans et al. 2001) to demonstrate equal lane loading. Right shows quantitation of average Aβ levels in coffee extract-treated CL4176 worms relative to untreated worms, obtained from the four independent experiments shown on the left. Total Aβ immunoreactivity (monomeric and multimeric bands) in each lane was quantified. Error bars = SEM.

Coffee extracts induce the skn-1/Nrf2 pathway:

To determine whether coffee extract needed to be present in the media to convey protection, Aβ transgenic worms were relocated at the third larval (L3) stage (48 hr after hatching) from coffee to control plates and upshifted to induce Aβ expression. As shown in Figure 4A, paralysis rates in worms that were shifted to control plates from coffee plates were still significantly slowed relative to worms maintained solely on control plates (although the protection was less than that observed with continual coffee exposure). This result suggested that coffee extract components do not need to be present at the time of Aβ accumulation to reduce Aβ toxicity. We hypothesized that the protective compounds in coffee extract might be acting by induction of a previously identified stress response pathway.

To test this hypothesis, we used a suite of transgenic GFP-reporter strains to determine whether 10% decaffeinated coffee could induce any of the major stress response pathways identified in C. elegans. The reporter strains and their previously characterized response patterns are listed in Table 1. No induction was observed for general heat shock response (Phsp-16∷GFP), the unfolded protein response (Phsp-4∷GFP), or reduced insulin-like signaling (nuclear localization of daf-16∷GFP) (data not shown). However, significant induction was observed for a Pgst-4∷GFP reporter (Figure 4B). To quantify this induction, staged populations of the Pgst-4∷GFP reporter strain (CL2166) were propagated on 10% decaffeinated coffee extract or control plates, and individual whole-animal GFP fluorescence was measured using a COPAS worm sorter. Coffee exposure resulted in a 77% increase in induction of GFP fluorescence for this reporter [control: 219.8 ± 9.0 arbitrary fluorescence units; 10% coffee: 389.7 ± 18.1 arbitrary fluorescence units (± SEM)]. gst-4 encodes a glutathione-s-transferase and is a downstream effector of the conserved skn-1 (Nrf2 in mammals) phase II detoxification pathway (Kahn et al. 2008).

TABLE 1.

| Strain | Genotype | Pathway | Responsive to | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL2166 | dvIs19 (Pgst-4∷GFP) | skn-1 | Oxidative stress | Link and Johnson (2002) |

| CL2070 | dvIs70 (Phsp-16.2∷GFP) | hsf-1 | Heat shock | Link et al. (1999) |

| SJ4005 | zcIs4 (Phsp-4∷GFP) | xbp-1 | ER stress | Calfon et al. (2002) |

| TJ356 | zIs356 (daf-16∷GFP) | daf-16 | Starvation, heat shock | Henderson and Johnson (2001) |

Transgenic stress-responsive GFP reporter strains used to assay the ability of coffee extracts to induce a stress response.

Like Nrf2, activation of SKN-1 requires a redistribution of this protein from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (An and Blackwell 2003). We therefore tested the ability of coffee extract to cause nuclear localization of a skn-1∷GFP translation fusion reporter gene. As shown in Figure 4C, propagation on 10% coffee extract induced nuclear localization of SKN-1∷GFP in intestinal nuclei, qualitatively similar to the effect of sodium azide exposure, a known inducer of skn-1 activation (Kell et al. 2007).

Coffee extract protection requires the SKN-1 transcription factor:

To determine whether induction of the skn-1 pathway was required for coffee protection in this model, we first knocked down expression of the SKN-1 master transcription factor by feeding RNA interference. SKN-1 has an essential (but maternally rescuable) role in C. elegans embryonic development, but we were able to establish RNAi conditions (see materials and methods) that resulted in treated worms that reached adulthood normally but had 100% inviable embryos. Under these conditions, skn-1 RNAi reversed the protective effects of coffee extracts (Figure 5A).

To test the role of skn-1 genetically, we constructed a strain (CL6222) with inducible Aβ expression and a strong loss-of-function allele of skn-1(zu169) balanced in trans with a translocation (nT1) marked with a dominant uncoordinated (Unc) mutation and a recessive lethal mutation. This strain segregates non-Unc skn-1(zu169) homozygous worms that are wild type in movement but become self-sterile adults. These skn-1 homozygotes show no protection from coffee exposure (Figure 5B), confirming the skn-1 requirement for coffee protection.

We also tested whether skn-1 activity was required for the reduced accumulation of Aβ peptide. Knockdown of skn-1 resulted in a significant increase in Aβ accumulation in transgenic worms on both coffee extract and control plates (Figure 5C), suggesting that the skn-1 pathway may generally play a role in modulating Aβ accumulation.

Coffee exposure does not reduce feeding:

Expression of the SKN-1 transcription factor specifically in the two C. elegans ASI neurons is necessary for life-span extension in response to dietary restriction (Bishop and Guarente 2007). Dietary restriction has also been shown to reduce the toxicity of aggregating proteins in C. elegans, including toxicity due to Aβ accumulation (Steinkraus et al. 2008). We considered the possibility that coffee extract might trivially provide protection by inhibiting C. elegans feeding and secondarily inducing a protective dietary restriction response. Mutations in eat-2 slow pharyngeal pumping (Raizen et al. 1995) thereby producing a genetic dietary restriction model that shows SKN-1–dependent life-span extension (Park et al. 2010). We directly measured pharyngeal pumping in response to coffee exposure but found no effect (Figure 6A). We also observed that coffee exposure had no effect on the developmental rate of wild-type worms, while in comparison eat-2 mutants grown on standard media show a day delay in reaching adulthood. To independently assess the possibility that coffee exposure was inducing dietary restriction, we made use of the observation that skn-1 loss-of-function mutations that preserve expression of a skn-1 isoform in the ASI neurons, such as zu67, can still show (attenuated) life-span extension in response to dietary restriction (Bishop and Guarente 2007). This result predicts that introduction of zu67 would not block coffee protection if the extract was acting by directly inducing dietary restriction. As shown in Figure 6B, transgenic worms homozygous for skn-1(zu67) are not protected by coffee exposure, consistent with the view that this protection was not through the ASI signaling underlying dietary restriction life-span extension.

Coffee extract protects against toxicity from model aggregating protein:

We have previously demonstrated that induced expression of GFP∷degron, a model aggregating protein, in C. elegans muscle can lead to a paralysis phenotype grossly similar to that caused by induction of Aβ42 (Link et al. 2006). To determine whether coffee extract exposure might be generally protective against aggregating protein toxicity, we assayed the effects of coffee extract exposure on a transgenic strain (CL2337) with inducible GFP∷degron expression. As shown in Figure 7A, coffee exposure strongly blocked the paralysis induced by GFP∷degron, and this protective effect was reversed by RNAi knockdown of SKN-1. Coffee exposure did not result in any qualitative change in GFP∷degron deposits (Figure 7B), but did cause a small reduction in the accumulation of GFP∷degron as assayed by immunoblot (Figure 7C).

DISCUSSION

We have shown that exposure to aqueous coffee extracts strongly reduces the paralysis resulting from induction of expression of Aβ42 in a transgenic C. elegans model. Coffee extract exposure-induced expression of a reporter transgene (gst-4 promoter∷GFP) controlled by the SKN-1 transcription factor, and protection against Aβ42 toxicity was reversed if SKN-1 is knocked down by RNAi or removed by genetic mutation. These results support the model that coffee protection against Aβ42 toxicity results from activation of the skn-1 pathway. SKN-1 is a member of the Cap'n'collar family of transcription factors that includes the Drosophila Cnc protein and the vertebrate Nrf1, Nrf2, and Nrf3 proteins (Sykiotis and Bohmann 2010). Although initially identified due to its role in embryonic development (Bowerman et al. 1992), subsequent studies demonstrated SKN-1 plays a role in the response to oxidative stress (An and Blackwell 2003). Thus, SKN-1 appears functionally analogous to Nrf2, the best-studied member of the Nrf family, which controls phase II detoxification response genes and is centrally involved in cellular responses to oxidative stress (reviewed in Osburn and Kensler 2008). Nrf2 activation, either by tert-butylhydroquinone treatment or viral Nrf2 gene transfection, has been shown to be protective in an APP/PS1 transgenic mouse model (Kanninen et al. 2008, 2009), as well as in neuronal cells exposed to exogenous Aβ (Wruck et al. 2008). Interestingly, a polymorphism in the human Nrf2 gene, NFE2L2, has recently been associated with earlier AD onset (Von Otter et al. 2010).

Studies have suggested that Nrf2 activation may be protective in a range of neurodegenerative conditions. For example, Nrf2 activation has been reported to be protective in a mouse MPTP model of PD (Chen et al. 2009), as well as a transgenic mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Vargas et al. 2008). Similarly, chemical or genetic activation of the Nrf2 pathway is protective in multiple Drosophila models of PD (Trinh et al. 2008). Of perhaps greatest relevance to our C. elegans studies, coffee and tobacco extracts have recently been shown to be protective in Drosophila neurodegeneration models, and this protection is Nrf2 dependent (Trinh et al. 2010). Our demonstration that coffee exposure protects against GFP∷degron, a model toxic aggregating protein not associated with a specific disease, further supports the generality of protection by Nrf2 activation.

What are the molecular mechanisms underlying skn-1–dependent coffee protection in the C. elegans Aβ toxicity model? We found that coffee exposure variably reduced the accumulation of Aβ (and GFP∷degron) as assayed by immunoblot, without reducing transgene expression. These results suggest that coffee extract activation of skn-1 may increase the degradation of Aβ. Nrf2 activation is known to upregulate expression of proteasomal subunits and proteasome activity (Arlt et al. 2009; Kapeta et al. 2010), and Nrf2-dependent upregulation of proteasomal activity has been directly implicated in protection against Aβ toxicity in cell culture models (Park et al. 2009a). However, in some experiments we observed coffee-induced protection against Aβ toxicity without a detectable decrease in accumulation (e.g., first two immunoblot lanes in Figure 3C). Thus, although loss of skn-1 leads to significant increase in the accumulation of Aβ (Figure 5C), skn-1 activation by coffee extract exposure leads to a smaller and more variable decrease in Aβ accumulation (Figure 3C). Therefore, protection in C. elegans by skn-1 activation may primarily result from the upregulation of other effectors of this pathway, particularly the numerous antioxidant genes that have been identified by gene expression analysis (Park et al. 2009b). Supporting this model, Nrf2 activation is protective in PD models that do not involve accumulation of a toxic protein: MPTP treatment in mice (Chen et al. 2009) and parkin loss-of-function in flies (Trinh et al. 2008). It may be possible to identify additional protective processes induced by coffee exposure by RNAi knockdown of individual skn-1–modulated genes.

What are the specific compounds in coffee extract responsible for activation of the skn-1/Nrf2 pathway? Our results indicate that caffeine is not the primary protective compound in aqueous coffee extracts, in agreement with the Drosophila studies examining the protective effects of coffee in PD models (Trinh et al. 2010). We cannot exclude the possibility that the protective effects of coffee are due to changes in the E. coli food source used in these experiments, but this seems highly unlikely given the effects of coffee extracts in other systems, such as flies, that do not use a bacterial food source. Multiple components of coffee have been shown to induce Nrf2 activation, including cafestol and kahweol (Higgins et al. 2008), and cafestol is protective in the Drosophila PD models (Trinh et al. 2010). A number of natural polyphenols, including hydroxytyrosol (Martin et al. 2010), quercetin (Kimura et al. 2009), and epigallocatechin-3-gallate (Na et al. 2008), have also been shown to activate the Nrf2 pathway. These observations suggest that the skn-1/Nrf2 pathway has evolved to be broadly responsive to xenobiotic compounds, and that there may be multiple compounds in coffee extracts that contribute to activation of this pathway. Given that invertebrate neurodegeneration models are actively being used to screen for protective compounds, it may be wise to test all initial positive compounds for skn-1/Nrf2 activation, as this may be a common molecular mechanism underlying protective responses.

It is currently unclear whether the protective effects of coffee in this C. elegans Aβ42 toxicity model are due to cell autonomous activation of the skn-1 pathway or more global physiological changes initiated by skn-1–activated intercellular signaling. This latter possibility is supported by reports that skn-1 expression in C. elegans is restricted to the intestine and the two ASI neurons, while Aβ42 accumulation and toxicity occur in body wall muscle cells (Link et al. 2001; An and Blackwell 2003). [We note that low-level expression of skn-1 in other cell types, such as muscle, may have been missed by the standard transgenic techniques used in the An and Blackwell (2003) study]. The role of skn-1 in dietary restriction-induced life-span extension depends solely on expression of SKN-1 in the ASI neurons (Bishop and Guarente 2007), implying that it is likely there are intercellular signaling events downstream of skn-1 activation modulating life span. Indeed, a neuropeptide-like hormone, NLP-7, has been recently shown to act downstream of skn-1 to promote life-span extension by dietary restriction (Park et al. 2010). It is also interesting to note that astrocyte activation of Nrf2 is sufficient to convey neuronal protection in mouse models of PD and ALS (Vargas et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2009), demonstrating that Nrf2-dependent neuroprotection in mammals can also be non-cell autonomous. The genetic tools available in C. elegans should allow us to determine to what degree cell autonomous activation of skn-1 contributes to protection against Aβ42 toxicity.

Our studies in C. elegans provide a plausible explanation of why epidemiological studies indicate consumption of coffee (and other plant extracts such as tea) may be protective against Alzheimer's disease and other neuropathologies. However, given the differences in human and nematode physiology, more study is needed to determine whether coffee activation of Nrf2 is actually the relevant mechanism in people. Of particular relevance are the questions of whether Nrf2-activating components of coffee actually cross the blood/brain barrier and whether Nrf2 activation in the periphery can lead to physiological changes that impact the brain. Nevertheless, our studies add to the growing body of literature indicating that Nrf2 activation is neuroprotective and accessible to dietary modulation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Leo Pallanck, University of Washington, for sharing data, protocols, and insights before publication. Phyllis Carosone-Link and James Cypser assisted with statistical analyses. Some C. elegans strains were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This work was supported by NIH grant AG12423 (to C.D.L.).

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.110.120436/DC1.

References

- An, J. H., and T. K. Blackwell, 2003. SKN-1 links C. elegans mesendodermal specification to a conserved oxidative stress response. Genes Dev. 17 1882–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendash, G. W., T. Mori, C. Cao, M. Mamcarz, M. Runfeldt et al., 2009. Caffeine reverses cognitive impairment and decreases brain amyloid-beta levels in aged Alzheimer's disease mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 17 661–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlt, A., I. Bauer, C. Schafmayer, J. Tepel, S. S. Muerkoster et al., 2009. Increased proteasome subunit protein expression and proteasome activity in colon cancer relate to an enhanced activation of nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). Oncogene 28 3983–3996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barranco Quintana, J. L., M. F. Allam, A. Serrano Del Castillo and R. Fernandez-Crehuet Navajas, 2007. Alzheimer's disease and coffee: a quantitative review. Neurol. Res. 29 91–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman, B., B. A. Eaton and J. R. Priess, 1992. skn-1, a maternally expressed gene required to specify the fate of ventral blastomeres in the early C. elegans embryo. Cell 68 1061–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, N. A., and L. Guarente, 2007. Two neurons mediate diet-restriction-induced longevity in C. elegans. Nature 447 545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calfon, M., H. Zeng, F. Urano, J. H. Till, S. R. Hubbard et al., 2002. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature 415 92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier-Harlin, M. C., F. Crawford, H. Houlden, A. Warren, D. Hughes et al., 1991. Early-onset Alzheimer's disease caused by mutations at codon 717 of the beta-amyloid precursor protein gene. Nature 353 844–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P. C., M. R. Vargas, A. K. Pani, R. J. Smeyne, D. A. Johnson et al., 2009. Nrf2-mediated neuroprotection in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease: critical role for the astrocyte. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106 2933–2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, S., T. L. Gumienny, M. O. Hengartner and M. Driscoll, 2000. A common set of engulfment genes mediates removal of both apoptotic and necrotic cell corpses in C. elegans. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2 931–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruts, M., L. Hendriks and C. Van Broeckhoven, 1996. The presenilin genes: a new gene family involved in Alzheimer disease pathology. Hum. Mol. Genet. 5 1449–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D., I. Perez, M. Macmorris, D. Leake, C. J. Wilusz et al., 2001. A complex containing CstF-64 and the SL2 snRNP connects mRNA 3′ end formation and trans-splicing in C. elegans operons. Genes Dev. 15 2562–2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florez-McClure, M. L., L. A. Hohsfield, G. Fonte, M. T. Bealor and C. D. Link, 2007. Decreased insulin-receptor signaling promotes the autophagic degradation of beta-amyloid peptide in C. elegans. Autophagy 3 569–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonte, V., D. R. Kipp, J. Yerg, III, D. Merin, M. Forrestal et al., 2008. Suppression of in vivo beta-amyloid peptide toxicity by overexpression of the HSP-16.2 small chaperone protein. J. Biol. Chem. 283 784–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, W. M., D. A. Merin, V. Fonte and C. D. Link, 2009. AIP-1 ameliorates beta-amyloid peptide toxicity in a Caenorhabditis elegans Alzheimer's disease model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18 2739–2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, S. T., and T. E. Johnson, 2001. daf-16 integrates developmental and environmental inputs to mediate aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 11 1975–1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, L. G., C. Cavin, K. Itoh, M. Yamamoto and J. D. Hayes, 2008. Induction of cancer chemopreventive enzymes by coffee is mediated by transcription factor Nrf2. Evidence that the coffee-specific diterpenes cafestol and kahweol confer protection against acrolein. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 226 328–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogewijs, D., K. Houthoofd, F. Matthijssens, J. Vandesompele and J. R. Vanfleteren, 2008. Selection and validation of a set of reliable reference genes for quantitative sod gene expression analysis in C. elegans. BMC Mol. Biol. 9 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G., S. Bidel, P. Jousilahti, R. Antikainen and J. Tuomilehto, 2007. Coffee and tea consumption and the risk of Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 22 2242–2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, N. W., S. L. Rea, S. Moyle, A. Kell and T. E. Johnson, 2008. Proteasomal dysfunction activates the transcription factor SKN-1 and produces a selective oxidative-stress response in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem. J. 409 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, R. S., A. G. Fraser, Y. Dong, G. Poulin, R. Durbin et al., 2003. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature 421 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanninen, K., T. M. Malm, H. K. Jyrkkanen, G. Goldsteins, V. Keksa-Goldsteine et al., 2008. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 protects against beta amyloid. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 39 302–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanninen, K., R. Heikkinen, T. Malm, T. Rolova, S. Kuhmonen et al., 2009. Intrahippocampal injection of a lentiviral vector expressing Nrf2 improves spatial learning in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106 16505–16510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapeta, S., N. Chondrogianni and E. S. Gonos, 2010. Nuclear erythroid factor 2-mediated proteasome activation delays senescence in human fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 285 8171–8184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kell, A., N. Ventura, N. Kahn and T. E. Johnson, 2007. Activation of SKN-1 by novel kinases in Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43 1560–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, S., E. Warabi, T. Yanagawa, D. Ma, K. Itoh et al., 2009. Essential role of Nrf2 in keratinocyte protection from UVA by quercetin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 387 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link, C. D., and C. J. Johnson, 2002. Reporter transgenes for study of oxidant stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods Enzymol. 353 497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link, C. D., J. R. Cypser, C. J. Johnson and T. E. Johnson, 1999. Direct observation of stress response in Caenorhabditis elegans using a reporter transgene. Cell Stress Chaperones 4 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link, C. D., C. J. Johnson, V. Fonte, M. Paupard, D. H. Hall et al., 2001. Visualization of fibrillar amyloid deposits in living, transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans animals using the sensitive amyloid dye, X-34. Neurobiol. Aging 22 217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link, C. D., A. Taft, V. Kapulkin, K. Duke, S. Kim et al., 2003. Gene expression analysis in a transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans Alzheimer's disease model. Neurobiol. Aging 24 397–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link, C. D., V. Fonte, B. Hiester, J. Yerg, J. Ferguson et al., 2006. Conversion of green fluorescent protein into a toxic, aggregation-prone protein by C-terminal addition of a short peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 281 1808–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M. A., S. Ramos, A. B. Granado-Serrano, I. Rodriguez-Ramiro, M. Trujillo et al., 2010. Hydroxytyrosol induces antioxidant/detoxificant enzymes and Nrf2 translocation via extracellular regulated kinases and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/protein kinase B pathways in HepG2 cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 54 956–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrell, J., M. Farlow, B. Ghetti and M. D. Benson, 1991. A mutation in the amyloid precursor protein associated with hereditary Alzheimer's disease. Science 254 97–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na, H. K., E. H. Kim, J. H. Jung, H. H. Lee, J. W. Hyun et al., 2008. (-)-Epigallocatechin gallate induces Nrf2-mediated antioxidant enzyme expression via activation of PI3K and ERK in human mammary epithelial cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 476 171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osburn, W. O., and T. W. Kensler, 2008. Nrf2 signaling: an adaptive response pathway for protection against environmental toxic insults. Mutat. Res. 659 31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, H. M., J. A. Kim and M. K. Kwak, 2009. a Protection against amyloid beta cytotoxicity by sulforaphane: role of the proteasome. Arch. Pharm. Res. 32 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, S. K., P. M. Tedesco and T. E. Johnson, 2009. b Oxidative stress and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans as mediated by SKN-1. Aging Cell 8 258–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, S. K., C. D. Link and T. E. Johnson, 2010. Life-span extension by dietary restriction is mediated by NLP-7 signaling and coelomocyte endocytosis in C. elegans. FASEB J. 24 383–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peto, R., and L. Peto, 1972. Asymptotically efficient rank invariant test procedures. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 135 185–207. [Google Scholar]

- Raizen, D. M., R. Y. Lee and L. Avery, 1995. Interacting genes required for pharyngeal excitation by motor neuron MC in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 141 1365–1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinkraus, K. A., E. D. Smith, C. Davis, D. Carr, W. R. Pendergrass et al., 2008. Dietary restriction suppresses proteotoxicity and enhances longevity by an hsf-1-dependent mechanism in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell 7 394–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman, M. C., T. R. Yamasaki, S. Oddo, J. C. Echegoyen, M. P. Murphy et al., 2002. Inclusion body myositis-like phenotype induced by transgenic overexpression of beta APP in skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99 6334–6339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykiotis, G. P., and D. Bohmann, 2010. Stress-activated cap'n'collar transcription factors in aging and human disease. Sci. Signal 3 re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh, K., K. Moore, P. D. Wes, P. J. Muchowski, J. Dey et al., 2008. Induction of the phase II detoxification pathway suppresses neuron loss in Drosophila models of Parkinson's disease. J. Neurosci. 28 465–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh, K., L. Andrews, J. Krause, T. Hanak, D. Lee et al., 2010. Decaffeinated coffee and nicotine-free tobacco provide neuroprotection in Drosophila models of Parkinson's disease through an NRF2-dependent mechanism. J. Neurosci. 30 5525–5532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, M. R., D. A. Johnson, D. W. Sirkis, A. Messing and J. A. Johnson, 2008. Nrf2 activation in astrocytes protects against neurodegeneration in mouse models of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurosci. 28 13574–13581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Otter, M., S. Landgren, S. Nilsson, M. Zetterberg, D. Celojevic et al., 2010. Nrf2-encoding NFE2L2 haplotypes influence disease progression but not risk in Alzheimer's disease and age-related cataract. Mech. Ageing Dev. 131 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, W. B., 1988. The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Wruck, C. J., M. E. Gotz, T. Herdegen, D. Varoga, L. O. Brandenburg et al., 2008. Kavalactones protect neural cells against amyloid beta peptide-induced neurotoxicity via extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2-dependent nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 activation. Mol. Pharmacol. 73 1785–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]