Abstract

The acquisition of superantigen-encoding genes by Streptococcus pyogenes has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality in humans, and the gain of four superantigens by Streptococcus equi is linked to the evolution of this host-restricted pathogen from an ancestral strain of the opportunistic pathogen Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus. A recent study determined that the culture supernatants of several S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strains possessed mitogenic activity but lacked known superantigen-encoding genes. Here, we report the identification and activities of three novel superantigen-encoding genes. The products of szeF, szeN, and szeP share 59%, 49%, and 34% amino acid sequence identity with SPEH, SPEM, and SPEL, respectively. Recombinant SzeF, SzeN, and SzeP stimulated the proliferation of equine peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production, in vitro. Although none of these superantigen genes were encoded within functional prophage elements, szeN and szeP were located next to a prophage remnant, suggesting that they were acquired by horizontal transfer. Eighty-one of 165 diverse S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strains screened, including 7 out of 15 isolates from cases of disease in humans, contained at least one of these new superantigen-encoding genes. The presence of szeN or szeP, but not szeF, was significantly associated with mitogenic activity in the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus population (P < 0.000001, P < 0.000001, and P = 0.104, respectively). We conclude that horizontal transfer of these novel superantigens from and within the diverse S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus population is likely to have implications for veterinary and human disease.

Gene gain via the horizontal acquisition of mobile genetic elements is a key factor in the emergence of new pathogenic strains of streptococci. An immediate selective advantage may be conferred on recipient bacteria through acquisition of antibiotic resistance mechanisms or the production of new virulence functions. Streptococcus equi subsp. equi is the causative agent of equine strangles, characterized by abscessation of the lymph nodes of the head and neck. S. equi subsp. equi is believed to have evolved from an ancestral strain of Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus (23, 49), which is associated with a wide variety of diseases in horses and other animals, including humans, through a process of gene loss and gain (20). These pathogens share approximately 80% DNA identity with the important human pathogen Streptococcus pyogenes (20).

During the 1980s, strains of S. pyogenes emerged that caused streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS), which was associated with particularly high morbidity and mortality in humans and the production of superantigens (sAgs) (13, 22). sAgs bypass the conventional mechanism of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-restricted antigen presentation (15) and interfere with the development of a protective immune response through the generation of an overzealous proinflammatory response (32), disruption of antigen-specific T-cell responses, and inhibition of specific antibody production (27, 43).

A total of 11 S. pyogenes sAgs have been described: SPEA, SPEC, SPEG, SPEH, SPEI, SPEJ, SPEK, SPEL, SPEM, SSA, and SMEZ (18, 43). The genes encoding SPEG, SPEJ, and SMEZ are chromosomally located, while the remaining sAg genes are located on mobile genetic elements. SPEA, SPEH, SPEI, and SSA share sequence similarities with the staphylococcal enterotoxins SEB, SEC, and SEG (18, 43). The S. equi subsp. equi strain 4047 genome contains four genes: seeH, seeI, seeL, and seeM (20), also known as sepe-H, sepe-I, speLSe, and speMSe, respectively, that encode homologues of S. pyogenes sAgs (4, 36). These genes are carried on two prophages, seeL and seeM on φSeq3 and seeH and seeI on φSeq4. S. equi subsp. equi sAgs stimulate equine T-cell proliferation in vitro and likely play an important role in S. equi subsp. equi pathogenicity (2, 4, 33). Interestingly, S. equi subsp. equi strain CF32 contains these sAg genes and predates SPEL- and SPEM-producing strains of S. pyogenes (20, 22), suggesting that cross-species transfer may have been responsible for the emergence of invasive M3/T3 strains of S. pyogenes. Comparison of S. equi subsp. equi strain 4047 prophage sequences to those in the public databases revealed that they share extensive similarity with prophage from S. pyogenes, so much so that clustering analysis demonstrated that the individual S. equi subsp. equi prophage are more closely related to phage in the sequenced S. pyogenes genomes than they are to each other, suggesting that the exchange of converting phage continues to influence the virulence of these important pathogens (20).

S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus is the most frequently isolated opportunistic pathogen of horses; it is associated with inflammatory airway disease in Thoroughbred racehorses (50, 51), uterine infections in mares (21, 41), and ulcerative keratitis (8). It is also associated with disease in a wide range of other animal hosts, including cattle (39), sheep (25, 44), pigs (38, 42), monkeys (38, 42), dogs (12, 34), and humans (7, 17, 19). The broad range of hosts and tissues infected by S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus is reflected in its population diversity as determined by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (49). Screening of a diverse population of 140 S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus isolates identified 25 strains of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus that elicited potent mitogenic activity but did not test positive for the presence of seeH, seeI, seeL, or seeM (20), raising the possibility that these strains produce as-yet-unidentified sAgs. Several of these strains were related by MLST (49) and clustered into three groups around sequence type 123 (ST-123), ST-7, and ST-8 (20).

In this study, we sequenced the genome of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 (ST-123), isolated from a dog with acute fatal hemorrhagic pneumonia in the United Kingdom in 1999 (49). Using comparative genomic analysis, we report the identification, activity, and prevalence of three novel sAgs and provide further evidence that the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus population harbors virulence loci of importance to cross-species pathogen evolution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain growth and DNA isolation.

S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 was isolated from a dog with acute fatal hemorrhagic pneumonia in London, England, in 1999 and has been typed as ST-123 by MLST (49). Details of all of the isolates examined in this study are presented in Table SA1 in the supplemental material and are also available in the online MLST database (http://pubmlst.org/szooepidemicus/ [accessed 28 June 2010).

For the preparation of DNA for whole-genome sequencing, S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 was grown overnight in Todd-Hewitt broth (THB) at 37°C in a 5% CO2-enriched atmosphere. Cells were harvested, and chromosomal DNA was extracted according to the method of Marmur (30) with the addition of 5,000 units of mutanolysin (Sigma) and 20 μg of RNase A (Sigma) during the lysis step.

Whole-genome sequencing.

The genome of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 was sequenced to ∼45-fold coverage using a Genome Sequencer-FLX (454 Life Sciences; Roche Applied Sciences, IN). Two sequencing libraries were prepared from genomic DNA: the first was a fragment (∼250- bp read length) and the second was a 3,000-bp insert, long-tag paired end library (∼100 bp) to provide scaffolding. The 515,689 reads were assembled with Newbler (v2.0.01.14) using the default assembly parameters.

Annotation and analysis.

Protein-coding genes were identified with GLIMMER (14) and GENEMARK (29) and tRNA genes with tRNAscan-SE (28). Putative functions were inferred using BLAST against the National Center for Biotechnology Information databases and InterProScan (1). Artemis v11 was used to organize data and facilitate annotation (37). Repeat identification was made using MUMmer (24). Comparison of the genome sequences was facilitated by using the Artemis Comparison Tool (ACT) (11). Orthologues were defined using ORTHOMCL (26), and inferred positional information was investigated using ACT. The sequences used for comparative genomic analysis were S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain MGCS10565 (CP001129) (6), S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain H70 (FM204884) (20), and S. equi subsp. equi strain 4047 (FM204883) (20).

Generation of recombinant sAgs.

sAg coding sequences (CDSs) were cloned as glutathione S-transferase (GST) (szeF and szeP) or His tag (szeN) fusions using pGEX-3X or pET-24a, respectively, and the primers listed in Table SA2 in the supplemental material. The cloned fragments corresponded to codons, 30 to 235 (szeF), 35 to 264 (szeP), and 28 to 246 (szeN), and in each case, the DNA encoding the signal peptide was omitted. PCR products were generated using S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 DNA and Phusion DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs). The purified PCR products were cut with either BamHI and EcoRI (szeF and szeP) or NdeI and XhoI (szeN), ligated into the pGEX-3X vector or the pET-24a vector cut with the appropriate restriction enzymes, and transformed into E. coli DH10B (for pGEX-3X fusion constructs) or E. coli BL21(DE3) (for pET-24a fusion constructs), and transformants were selected at 37°C on 2× yeast extract-tryptone (YT) plates with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) or kanamycin (50 μg/ml), respectively. For expression, cultures (100 ml) were grown overnight at 37°C in 2× YT with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) or kanamycin (50 μg/ml), diluted 1/10 the next day, grown for 1 h, induced with 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), and grown for a further 4 h at 28°C. Cells were harvested and lysed, and fusion protein was recovered using glutathione-Sepharose beads (GST fusions) (Amersham) or His SpinTrap columns (His fusions) (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Factor Xa (Amersham) was then used to cleave the recombinant proteins from the GST. The His tag was not cleaved from recombinant His-tagged proteins. The purified recombinant sAgs were then quantified and stored at −70°C in 50% glycerol.

Mitogenicity assays and quantification of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) synthesis.

Functional activities of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus sAgs were measured as previously described (33). Briefly, equine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were purified from heparinized blood by centrifugation on a Ficoll density gradient. PBMCs (2 × 105) were incubated with S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus recombinant sAgs at the indicated concentrations. The recombinant S. equi subsp. equi sAg SeeL was used as a positive control. PBMC proliferation was detected by overnight incorporation of [3H]thymidine (3HT) after 3 days of culture. Equine PBMC proliferation was performed in triplicate and expressed as a stimulation index (SI) calculated as follows: (experimental response)/(control response). An SI of ≥2 was considered positive. TNF-α synthesis was measured in the culture supernatant of equine PBMCs (1 × 106 cells/ml) stimulated with recombinant sAgs using the equine TNF-α screening set (Thermo Scientific). For measurement of IFN-γ synthesis, 1 × 106 fresh PBMCs were stimulated in vitro with sAgs at the indicated concentrations, or medium alone as a negative control, in the presence of brefeldin A (BFA) (BD GolgiPlug; BD Biosciences). After overnight incubation, the cells were fixed in 3% (vol/vol) formaldehyde in PBS prior to detection of equine IFN-γ by intracellular-cytokine staining (ICC) using an antibody specific for equine IFN-γ (clone CC302; Serotec) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch). IFN-γ detection was performed in duplicate. The percentage of sAg-specific IFN-γ synthesis was calculated according to the following formula: (percent sAg-stimulated IFN-γ synthesis) − (percent medium-stimulated IFN-γ synthesis). Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (100 ng/ml) and ionomycin (5 μM) were used as positive controls for IFN-γ stimulation.

Gene prevalence studies.

Genomic DNA from a diverse set of 26 S. equi subsp. equi strains and 165 S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strains was prepared from single colonies grown on COBA strep select plates (bioMérieux) and purified using GenElute spin columns according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma). The relatedness of MLST STs was determined using ClonalFrame (16) by generating a majority rules 50% consensus tree from 6 independent runs of ClonalFrame (16), each with 250,000 iterations, and viewed using MEGA (45). Gene prevalence was then determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using a SYBR green-based method with a Techne Quantica instrument. For the qPCR, 10 ng DNA was mixed with 0.3 μM forward and reverse primers (see Table SA2 in the supplemental material) and 1× ABsolute qPCR SYBR green mix (Abgene) in a total volume of 20 μl and subjected to thermocycling at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Dissociation curves were analyzed following a final ramp step from 60°C to 90°C with reads at 0.5°C increments to rule out nonspecific amplification. Data were analyzed using Quansoft software (Techne). Crossing point values relative to those for the gyrA housekeeping gene were used to determine gene presence or absence.

Sequencing of szeF.

The szeF gene was PCR amplified using primers F1 and R1 (see Table SA2 in the supplemental material). The PCRs were performed in volumes of 50 μl using Hotstar Taq plus (Qiagen) with a 15-min activation at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 59°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min and a final elongation time of 10 min at 72°C. The amplified DNA fragments were purified using a PCR purification kit (Qiagen), and the sequence of szeF was obtained on both strands using an ABI3100 DNA sequencer with BigDye fluorescent terminators with the original F1 and R1 primers and primers F2 and R2, which are internal to those used in the initial PCR. Sequence data were assembled using SeqMan 5.03 (DNAstar Inc.).

Phage particle DNA purification and PCR.

Phage particle DNA was purified according to previously published methods (5). S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 was grown to log phase and treated for 3 h with mitomycin C. The bacteria were centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant was sterilized with a 0.45-μm filter (Millipore). The filter-sterilized supernatant was centrifuged at 141,000 × g for 4 h at 10°C, and the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml phage suspension buffer. Phage particles (0.5 ml) were treated with 25 U benzonase (Novagen) for 1 h at 37°C and then lysed with 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10 mM EDTA, and 500 μg of proteinase K (Sigma)/ml for 1 h at 37°C. Phage DNA was extracted with an equal volume of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) (Sigma), followed by an equal volume of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) (Sigma). The phage DNA was precipitated with 300 mM sodium acetate (NaOAc) (pH 4.6) (Sigma) and a 2.5-fold volume of ethanol at −20°C overnight, washed with 70% ethanol, and suspended in distilled H2O.

Prophage induction was determined by PCR with primers φBHS5.1f and φBHS5.1r (see Table SA2 in the supplemental material), which were specific for recircularized φBHS5.1 and were predicted to amplify across the join of prophage ends. S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 genomic DNA was used to confirm that the integrated prophage did not generate a PCR product using these primers.

Statistical methods.

Fisher's exact test was used to test the null hypothesis that there were no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of sAg-encoding sequences in S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strains that were mitogenic or recovered from cases of acute fatal hemorrhagic pneumonia in dogs or nonstrangles lymph node abscessation. Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata 9.2 software (StataCorp LP), with statistical significance set at a P value of ≤0.05.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequence and annotation of the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 genome have been deposited in the EMBL database under accession numbers CABY01000001 to CABY01000011.

RESULTS

Identification of novel sAg-encoding sequences in S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5.

The group of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus isolates most closely related to S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 (ST-123) by MLST includes strain 6360 (ST-127), isolated from an equine wound infection; strain 0482 (ST-141), isolated from an equine cervical swab; and strain 0985 (ST-129) from an independent case of canine acute fatal hemorrhagic pneumonia in the United States in 2005. Conditioned culture media from all of these isolates, with the exception of strain 0985, which was not available for this study, elicited potent mitogenic activity on equine PBMCs (20). However, qPCR of these strains did not amplify the products of seeH, seeI, seeL, or seeM. We generated an ∼45-fold-coverage draft genome sequence of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 with the aim of identifying the novel sAg-encoding sequence(s) responsible for the strain's mitogenic activity.

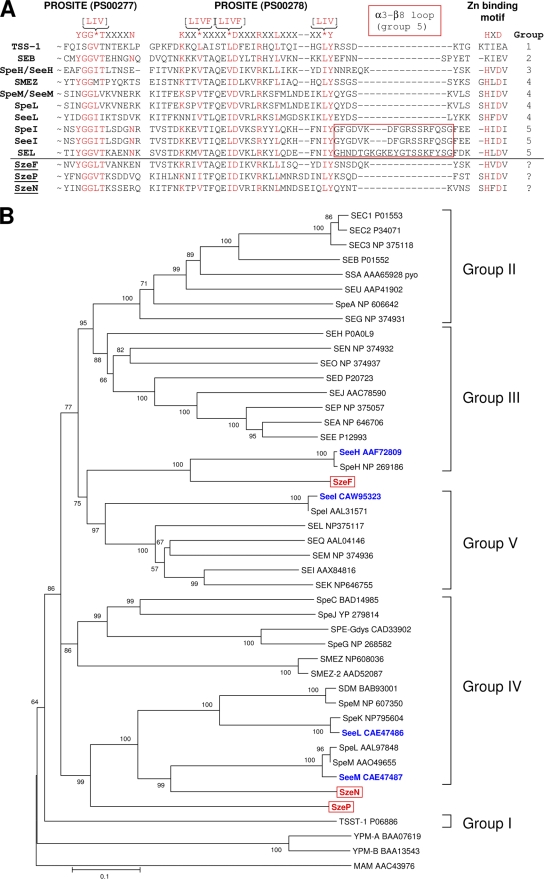

Analysis of the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 genome identified three new putative sAg-encoding sequences: szeF (SzBHS5_01670), szeN (SzBHS5_04190), and szeP (SzBHS5_04180). The predicted products of these sequences share 59%, 49%, and 34% amino acid sequence identity with the sAgs SPEH, SPEM, and SPEL, respectively. They possess a characteristic sAg amino acid sequence signature, K-X2-[LIVF]-X4-[LIVF]-D-X3-R-X2-L-X5-[LIV]-Y (Prosite pattern PS00278) (35), and the primary zinc binding motif (H-X-D) near the carboxy terminus. The second sAg amino acid sequence signature Y-G2-[LIV]-T-X4-N (Prosite pattern PS00277) is only partially conserved in szeF, szeN, and szeP (Fig. 1A). None of these S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus sAgs possess the α3-β8 loop that characterizes group 5 sAgs (10). Comparison of the predicted amino acid sequences of SzeF, SzeN, and SzeP with known sAg sequences confirmed that each of these sAgs represented a novel example, with SzeP sharing the least similarity with known sAgs (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

(A) Superantigen characteristic signature sequences. The sAg PROSITE sequences and zinc binding motif are highlighted in red. The group 5 sAg-specific α3-β8 loop is shown in the red box. (B) Neighbor-joining tree showing phylogenetic relationships of known full-length sAgs. S. equi subsp. equi sAgs and novel S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus sAgs are highlighted in blue and red, respectively. The five main groups of sAgs are indicated (30, 31). The unrooted tree was based on the alignment of amino acid sequences using ClustalW (47) and constructed using MEGA 4 (45). The sAg abbreviations are indicated, followed by the relevant accession numbers. Percentages from 1,000 bootstraps supporting a given partitioning are indicated on the branches.

The novel sAgs are active in vitro.

Recombinant SzeF, SzeN, and SzeP stimulated the proliferation of equine PBMCs in vitro with median half-maximal proliferation responses (P50s) of 4.5 ± 4.9 ng/ml (n = 4), 5.35 ± 3.1 pg/ml (n = 7), and 25.9 ± 6.6 pg/ml (n = 8), respectively (Fig. 2A). Proliferation of equine PBMCs was detected as early as 24 h after stimulation with SzeP (Fig. 2B). A peak of proliferation was reached at 48 h after stimulation with SzeP and SzeN and at 72 h after stimulation with SzeF. All 3 S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus sAgs induced the production of TNF-α by equine PBMCs in vitro, with synthesis particularly noteworthy after stimulation with SzeN and SzeP (Fig. 2C). IFN-γ synthesis was also induced by all three sAgs (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

Functional activities of recombinant SzeF, SzeN, and SzeP in vitro. (A) Dose response. Equine PBMCs (2 × 105) were cultured for 4 days in triplicate with the indicated concentrations of sAg and incubated with 3HT for 16 h before measurement of proliferation. (B) Kinetics of proliferation. Equine PBMCs (2 × 105) were cultured with 0.125 μg/ml sAg in triplicate for 24 to 96 h. 3HT was added for the last 16 h of each period. The results are presented as the stimulation index. (C and D) Kinetics of TNF-α synthesis in equine PBMC culture supernatants (C) and IFN-γ synthesis after overnight culture (D) after stimulation with recombinant sAgs (0.125 μg/ml). Recombinant SeeH and SeeL (33) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. IFN-γ synthesis was detected by flow cytometry after intracellular staining. The dashed line represents the threshold above which the response was considered positive (>2). The error bars represent standard deviations from the mean.

Genomic context of the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 sAg genes suggests that they are horizontally transferred.

szeF is located at a locus orthologous to the attachment site of φSeq1 of S. equi subsp. equi strain 4047 but is not associated with prophage-like CDSs, and therefore, it is not possible to determine the precise method of its acquisition. szeN and szeP are located next to one another but oriented in opposite directions and are up- stream of the prophage-associated CDSs SzBHS5_04200 and SzBHS5_04210. SzBHS5_04200 and SzBHS5_04210 share 59% and 90% predicted amino acid identity with the predicted products of the Streptococcus agalactiae prophage-like CDSs SAG1836 and SAG1835, respectively (46).

A 132-bp gene fragment (SzBHS5_05670) sharing 83% DNA sequence identity with the 5′ region of szeP but lacking sAg motifs was identified in the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 genome alongside a prophage remnant (SzBHS5_05640). We also identified a nonannotated 121-bp homologue of this gene remnant in S. equi subsp. equi strain 4047 between SEQ0511 and SEQ0514, a 72-bp S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain H70 orthologue between SZO15420 and SZO15430, and a 132-bp orthologue between Sez_0438 (a putative phage integrase) and Sez_0439 of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain MGCS10565. These gene fragments shared 95% to 99% DNA identity with each other.

Although none of the novel S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus sAgs are associated with complete prophage, the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 genome contains a single 54-kb prophage. φBHS5.1 is integrated between SzBHS5_08790 and SzBHS5_09350, which is in the same context as ICESe1 in the S. equi subsp. equi strain 4047 genome. The predicted products of the putative cargo of φBHS5.1 (SzBHS5_09320 and SzBHS5_09330) share amino acid sequence identity with type III restriction-modification system proteins. φBHS5.1 is predicted to encode 55 products, 54 of which share >44% amino acid identity with the predicted products of other bacterial genomes (see Table SA3 in the supplemental material). However, in contrast to prophage of S. equi subsp. equi strain 4047, none of the best matches were identified in other streptococcal genomes. Twelve φBHS5.1 CDSs shared between 59% and 88% amino acid identity with predicted products of Anaerostipes caccae strain DSM 14662, and 11 CDSs shared between 64% and 92% amino acid identity with Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195. Recircularized φBHS5.1 was not amplified by PCR across the join of the predicted recircularized phage following preparation of phage particles present in cultures of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 treated with mitomycin C, suggesting that this prophage may not be capable of recircularization.

Prevalence of novel sAgs in other S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strains.

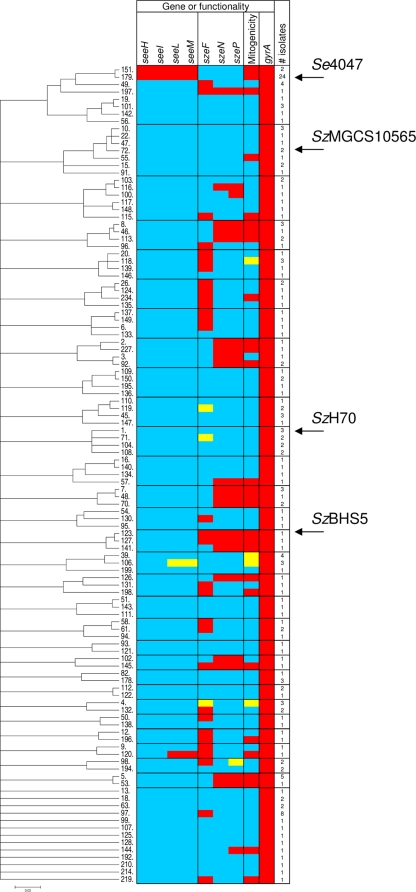

To determine the prevalence of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus sAgs, we screened by qPCR a panel of S. equi subsp. equi and S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strains that were representative of the wider population as defined by MLST (49). They included 26 isolates of S. equi subsp. equi (representing 2 STs) and 165 isolates of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus (representing 111 STs) (49). Of the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus isolates examined, 31% (51 of 165) contained szeF, 19% (32 of 165) contained szeN, and 21% (35 of 165) contained szeP (Fig. 3). In terms of repartition, 45 S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus isolates possessed szeF alone and 2 isolates possessed szeP alone, but szeN was not present in the absence of szeP. Twenty-eight isolates possessed both szeN and szeP, one isolate possessed szeF and szeP, and four S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus isolates possessed all three sAgs. Only one isolate possessed seeL, seeM, and szeF. None of the 26 diverse isolates of S. equi subsp. equi examined contained szeF, szeN, or szeP.

FIG. 3.

ClonalFrame analysis of MLST alleles of 26 S. equi subsp. equi and 165 S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus isolates and its relationship to the prevalence of sAg genes and mitogenic activity. Shown is a majority rules 50% consensus tree generated from 6 independent runs of ClonalFrame (16), each with 250,000 iterations, and imported into MEGA 4 (45). The genes examined were seeL, seeM, seeH, seeI, szeF, szeN, szeP, and gyrA. Mitogenic assays determined the abilities of different isolates to induce proliferation of equine PBMCs. The number of isolates representing each ST is indicated. STs in which all isolates contained the gene or possessed functional activity are shown in red, STs in which all isolates lacked the gene or functionality are shown in blue, and STs in which not all isolates contained the gene or functionality are colored yellow. The positions of S. equi subsp. equi strain 4047 and S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strains H70, MGCS10565, and BHS5 are indicated.

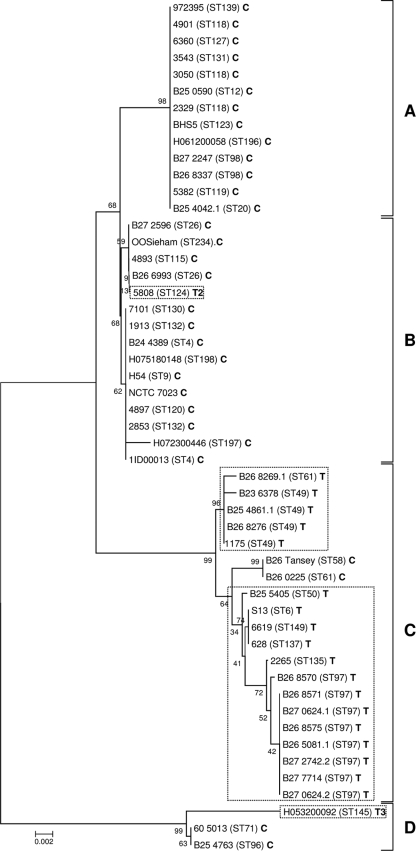

The presence of szeN or szeP was significantly associated with mitogenic activity (P < 0.000001), but that was not the case for szeF (P = 0.104). Additional sAg-encoding genes were identified in 5 out of the 12 isolates that contained szeF and were mitogenic. S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain 1175 (ST-49) represents one of the 38 isolates that were qPCR positive for szeF alone and produced culture supernatants that did not stimulate the proliferation of equine PBMCs in vitro. The cluster of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strains around ST-49 are the most closely related by MLST to S. equi subsp. equi and are significantly associated with isolation from cases of uterine infection or abortion in horses (P < 0.001) (49). We have generated a draft genome sequence for S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain 1175, the full details of which will be reported elsewhere. Analysis of this sequence data confirmed that S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain 1175 contains a copy of szeF in the same genome context as in the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 genome. However, the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain 1175 copy of szeF contains a 10-bp insertion at bp 333 leading to a frameshift at codon 111 and a nonsense mutation at codon 114, which provides one explanation for the strain's lack of mitogenic activity. PCR and sequencing of all 51 szeF-containing strains (including S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain 1175) revealed that 18 of the strains, encompassing ST-49, ST-135, ST-137, ST-149, ST-6, ST-61, ST-50, and ST-97, contained the same 10-bp insertion (Fig. 4; see Table SA1 in the supplemental material). S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain 5808 (ST-124) contained an 11-bp deletion at bp 16 leading to a frameshift and nonsense mutation at codon 23, and strain H053200092 (ST-145) contained a 1-bp deletion at position 427 leading to a frameshift and nonsense mutation at codon 155. Together, these truncations provide an explanation for the lack of mitogenic activity in 19 of the 38 nonmitogenic szeF-containing strains. However, accounting for truncated forms, szeF was still not significantly associated with mitogenic activity in vitro (P = 0.073).

FIG. 4.

Neighbor-joining tree showing phylogenetic relationships of szeF in 51 S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus isolates that screened positive. The unrooted tree was based on the alignment of nucleotide sequences using ClustalW (47) and constructed using MEGA 4 (45). Percentages from 1,000 bootstraps supporting a given partitioning are indicated on the branches. C indicates a predicted full-length SzeF. T, T2, and T3 (dotted boxes) indicate predicted truncated SzeF amino acid sequences (113, 22, and 154 amino acids long, respectively). The four groups of szeF (A, B, C, and D) are indicated.

Analysis of szeF sequencing data identified four distinct phylogenetic groups (Fig. 4). All strains sharing the same 10-bp insertion as strain S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain 1175 clustered in szeF group C. The remaining two S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strains containing a szeF group C sequence were B26Tansey and B260225, which did not contain the 10-bp insertion but contained an A-to-G substitution at bp 457. This mutation leads to a K-to-E substitution at amino acid 153, which forms part of a 12-amino-acid sequence (TKKRIVTAQEID) that is well conserved among bacterial sAgs.

The majority of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strains related by MLST analysis were found to share similar szeF sequences, although some groups of unrelated MLST types also shared similar szeF sequences. For example strains 972395 (ST-139), 4901 (ST-118), 3050 (ST-118), 2329 (ST-118), and B25 4042.1 (ST-20) clustered in szeF group A and are related by ClonalFrame analysis of MLST data (Fig. 3). Strains BHS5 (ST-123) and 6360 (ST-127) are single-locus variants related by MLST but unrelated to the ST-118 group (Fig. 3) that share szeF sequences identical to those of the ST-118 group (Fig. 4).

Of the 51 S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strains containing szeF, three groups of strains related by MLST contained szeF sequences of different groups. These were strains 3543 (ST-131) and H075180148 (ST-198), which contained szeF sequences in groups A and B, respectively; 2265 (ST-135), which contained a group C szeF in contrast to strains B272596 (ST-26), OOSieham (ST-234), B266993 (ST-26), and 5808 (ST-124), which are related to strain 2265 by MLST but contained szeF group B sequences; and H072300446 (ST-197), which had a group B szeF but was related to strains B236378 (ST-49), B254861.1 (ST-49), B268276 (ST-49), and B271175.2 (ST-49), which had group C szeF sequences.

Of the five mitogenic strains of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus examined in this study that do not possess szeF, szeN, or szeP, two were qPCR positive for seeL and seeM. All 15 isolates from the three mitogenic groups of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus that were related by MLST (ST-123, ST-127, and ST-141; ST-7, ST-48, ST-70, ST-5, and ST-53; and ST-8, ST-46, and ST-113) (20) contained szeF, szeN, and/or szeP. Strains of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus that were isolated from cases of canine hemorrhagic pneumonia were significantly less likely to contain sAg-encoding genes (P = 0.015). However, mitogenic activity was significantly associated with strains isolated from equine cases of slowly forming nonstrangles lymph node abscesses (P = 0.003), and all 10 isolates from nonstrangles lymph node abscesses were qPCR positive for szeF, szeN, and/or szeP (P = 0.0006).

DISCUSSION

In this article, we report the identification of three novel sAgs,: SzeF, SzeN, and SzeP, from a strain of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus (BHS5) isolated from a case of acute fatal hemorrhagic pneumonia in a dog from the United Kingdom in 1999. Screening of a diverse collection of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus isolates by qPCR revealed that 49% (81/165) of these isolates were positive for the new sAg genes. However, despite the origins of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5, the presence of superantigen-encoding genes in the broader S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus population was not associated with isolation from cases of acute fatal hemorrhagic pneumonia in dogs, and we hypothesize that other features of the genomes of these strains are responsible for their ability to cause this disease. Importantly, the presence of superantigen-encoding genes was significantly associated with isolation from equine cases of nonstrangles lymph node abscessation. Our data suggest that superantigens play an important role in the development of this disease and provide further evidence that the four S. equi subsp. equi superantigens, SeeH, SeeI, SeeL, and SeeM, are important to the ability of this host-restricted pathogen to cause lymph node abscessation and strangles (2, 4, 20, 36). However, the prevalence of functional sAgs across the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus population (81/165 isolates) also argues that the additional features of the S. equi subsp. equi genome may enhance the speed of lymph node abscessation typically observed during outbreaks of strangles.

Interestingly, SzeF, which shares 59% amino acid identity with SpeH and SeeH, was much less potent at stimulating equine PBMCs than SzeN and SzeP. Our findings are in agreement with recent data, which showed that in contrast to an earlier study (4), SeeH of S. equi subsp. equi did not stimulate equine PBMCs in vitro and that deletion of seeI, seeL, and seeM abolished the mitogenic activity of S. equi subsp. equi strain 4047 culture supernatants (33). SeeH was found to stimulate PBMCs isolated from 6 out of 8 donkeys and is hypothesized to increase the ability of S. equi subsp. equi to infect a broader host range. SzeF may play a similar role in extending the host range of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus. The identification of φBHS5.1, which shares little homology with other streptococcal prophage, coupled with the ability of the species to infect a large number of different mammalian hosts, highlights the potential role of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus as a mixing vessel and source of new virulence factors.

The presence of szeP-like gene fragments in the same genome context of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5, S. equi subsp. equi strain 4047, S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain H70, and S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain MGCS10565 suggests that they originated in a common evolutionary ancestor. The gain and fragmentation of the szeP-like fragment and reacquisition of szeP in S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 illustrate that the pathogenic niches occupied by S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus and its ancestors have probably changed during the course of its evolution. The determination that 19 of 51 szeF sequences are likely to generate a truncated gene product highlights the fact that this process of gene gain and loss continues today and that the production of sAgs may not be advantageous in certain pathogenic niches. For example, the culture supernatants of only 4 of 45 isolates from cases of uterine infection or abortion examined in this study possessed mitogenic activity (P < 0.00093). However, we note that superantigen activity in some strains could be masked by the production of cytolysins or other factors that interfere with their activity (31, 48). It is interesting that the majority of truncated szeF sequences (18/20) clustered together in szeF group C and that the remaining two group C szeF sequences contained an A-to-G substitution at bp 457 leading to a K-to-E substitution at amino acid 153. This region is involved in transcytosis of the sAg through the epithelium and cytokine synthesis (3, 9, 40), and we hypothesize that the K153E substitution will affect the function of this predicted form of SzeF.

Previous observations regarding the associations of streptococcal sAgs with phage (20) and the genomic context of szeF, szeN, and szeP in S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 suggest that it is very likely that they were transduced into S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5. The corresponding region of the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain MGCS10565 genome contains CDSs with homology to phage integrases (Sez_0298) and plasmid/phage replication initiation proteins (Sez_0300), suggesting that this area of the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus genome may be targeted for lysogenic conversion. The further horizontal transfer of the sAg-CDSs from S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 may be hypothesized to be unlikely based on their present genome context. However, the presence of similar szeF sequences in strains that were unrelated by MLST suggests that horizontal transfer of these genes within the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus population has occurred. Related bacteriophage carrying highly similar sAg cargo have been identified in the genomes of S. pyogenes and S. equi subsp. equi, showing that the pangenomes of these distinct pathogens are linked (20). The identification of homologous orphaned sAg cargo related to those in S. pyogenes and S. equi subsp. equi suggests that S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus also contributes to the pangenome.

This study utilized 15 isolates from human cases of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus infection, including cases of meningitis and septicemia. Seven of these isolates contained szeF, szeN, and/or szeP and had mitogenic activity against equine PBMCs. The genome context of szeF, szeN, and szeP in other isolates of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus is not yet known, but the high prevalence of these genes across diverse groups of the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus population suggests that there may yet be examples of strains in which these sAg genes reside within functional prophage elements and retain the capacity for horizontal transfer. It will be interesting to determine if these sAgs have already been transferred to the S. pyogenes population and if such transfer events have affected the virulence of this important human pathogen.

The absence of mitogenic activity in the culture supernatants of 19 strains containing only szeF and which have a confirmed complete szeF coding sequence suggests that the levels of SzeF produced by these strains in culture are insufficient to trigger a mitogenic response in vitro and that the remaining seven mitogenic strains that were qPCR positive only for szeF either produce significantly more SzeF or produce additional uncharacterized sAgs. The mitogenic strains B237163, NCTC4675, and HO53200090 were qPCR negative for all seven sAg-encoding genes examined in this study, suggesting that they are likely to contain additional as-yet-uncharacterized sAgs. Our data illustrate the diversity of the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus population and highlight its importance as a reservoir of streptococcal virulence factors with the potential for horizontal transfer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The determination of the S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain BHS5 genome sequence was completed as part of the RCVS Trust Veterinary Pathogen Genomics Project at the University of Liverpool.

A.S.W. is funded by the Anne Duchess of Westminster's Charity. C.R. is funded by the Elise Pilkington Charitable Trust.

Editor: J. N. Weiser

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 August 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anzai, T., A. S. Sheoran, Y. Kuwamoto, T. Kondo, R. Wada, T. Inoue, and J. F. Timoney. 1999. Streptococcus equi but not Streptococcus zooepidemicus produces potent mitogenic responses from equine peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 67:235-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arad, G., D. Hillman, R. Levy, and R. Kaempfer. 2001. Superantigen antagonist blocks Th1 cytokine gene induction and lethal shock. J. Leukoc. Biol. 69:921-927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Artiushin, S. C., J. F. Timoney, A. S. Sheoran, and S. K. Muthupalani. 2002. Characterization and immunogenicity of pyrogenic mitogens SePE-H and SePE-I of Streptococcus equi. Microb. Pathog. 32:71-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banks, D. J., B. Lei, and J. M. Musser. 2003. Prophage induction and expression of prophage-encoded virulence factors in group A Streptococcus serotype M3 strain MGAS315. Infect. Immun. 71:7079-7086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beres, S. B., R. Sesso, S. W. Pinto, N. P. Hoe, S. F. Porcella, F. R. Deleo, and J. M. Musser. 2008. Genome sequence of a Lancefield group C Streptococcus zooepidemicus strain causing epidemic nephritis: new information about an old disease. PLoS One 3:e3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley, S. F., J. J. Gordon, D. D. Baumgartner, W. A. Marasco, and C. A. Kauffman. 1991. Group C streptococcal bacteremia: analysis of 88 cases. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13:270-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks, D. E., S. E. Andrew, D. J. Biros, H. M. Denis, T. J. Cutler, D. T. Strubbe, and K. N. Gelatt. 2000. Ulcerative keratitis caused by beta-hemolytic Streptococcus equi in 11 horses. Vet. Ophthalmol. 3:121-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brosnahan, A. J., M. M. Schaefers, W. H. Amundson, M. J. Mantz, C. A. Squier, M. L. Peterson, and P. M. Schlievert. 2008. Novel toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 amino acids required for biological activity. Biochemistry 47:12995-13003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brouillard, J. N., S. Gunther, A. K. Varma, I. Gryski, C. A. Herfst, A. K. Rahman, D. Y. Leung, P. M. Schlievert, J. Madrenas, E. J. Sundberg, and J. K. McCormick. 2007. Crystal structure of the streptococcal superantigen SpeI and functional role of a novel loop domain in T cell activation by group V superantigens. J. Mol. Biol. 367:925-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carver, T. J., K. M. Rutherford, M. Berriman, M. A. Rajandream, B. G. Barrell, and J. Parkhill. 2005. ACT: the Artemis Comparison Tool. Bioinformatics 21:3422-3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chalker, V. J., H. W. Brooks, and J. Brownlie. 2003. The association of Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus with canine infectious respiratory disease. Vet. Microbiol. 95:149-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunningham, M. W. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:470-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delcher, A. L., D. Harmon, S. Kasif, O. White, and S. L. Salzberg. 1999. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:4636-4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dellabona, P., J. Peccoud, J. Kappler, P. Marrack, C. Benoist, and D. Mathis. 1990. Superantigens interact with MHC class II molecules outside of the antigen groove. Cell 62:1115-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Didelot, X., and D. Falush. 2007. Inference of bacterial microevolution using multilocus sequence data. Genetics 175:1251-1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Downar, J., B. M. Willey, J. W. Sutherland, K. Mathew, and D. E. Low. 2001. Streptococcal meningitis resulting from contact with an infected horse. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2358-2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraser, J. D., and T. Proft. 2008. The bacterial superantigen and superantigen-like proteins. Immunol. Rev. 225:226-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashikawa, S., Y. Iinuma, M. Furushita, T. Ohkura, T. Nada, K. Torii, T. Hasegawa, and M. Ohta. 2004. Characterization of group C and G streptococcal strains that cause streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:186-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holden, M. T., Z. Heather, R. Paillot, K. F. Steward, K. Webb, F. Ainslie, T. Jourdan, N. C. Bason, N. E. Holroyd, K. Mungall, M. A. Quail, M. Sanders, M. Simmonds, D. Willey, K. Brooks, D. M. Aanensen, B. G. Spratt, K. A. Jolley, M. C. Maiden, M. Kehoe, N. Chanter, S. D. Bentley, C. Robinson, D. J. Maskell, J. Parkhill, and A. S. Waller. 2009. Genomic evidence for the evolution of Streptococcus equi: host restriction, increased virulence, and genetic exchange with human pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong, C. B., J. M. Donahue, R. C. Giles, Jr., M. B. Petrites-Murphy, K. B. Poonacha, A. W. Roberts, B. J. Smith, R. R. Tramontin, P. A. Tuttle, and T. W. Swerczek. 1993. Etiology and pathology of equine placentitis. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 5:56-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikebe, T., A. Wada, Y. Inagaki, K. Sugama, R. Suzuki, D. Tanaka, A. Tamaru, Y. Fujinaga, Y. Abe, Y. Shimizu, and H. Watanabe. 2002. Dissemination of the phage-associated novel superantigen gene speL in recent invasive and noninvasive Streptococcus pyogenes M3/T3 isolates in Japan. Infect. Immun. 70:3227-3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jorm, L. R., D. N. Love, G. D. Bailey, G. M. McKay, and D. A. Briscoe. 1994. Genetic structure of populations of beta-haemolytic Lancefield group C streptococci from horses and their association with disease. Res. Vet. Sci. 57:292-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurtz, S., A. Phillippy, A. L. Delcher, M. Smoot, M. Shumway, C. Antonescu, and S. L. Salzberg. 2004. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 5:R12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Las Heras, A., A. I. Vela, E. Fernandez, E. Legaz, L. Dominguez, and J. F. Fernandez-Garayzabal. 2002. Unusual outbreak of clinical mastitis in dairy sheep caused by Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1106-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, L., C. J. Stoeckert, Jr., and D. S. Roos. 2003. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13:2178-2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Llewelyn, M., and J. Cohen. 2002. Superantigens: microbial agents that corrupt immunity. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2:156-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowe, T. M., and S. R. Eddy. 1997. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:955-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lukashin, A. V., and M. Borodovsky. 1998. GeneMark.hmm: new solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:1107-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marmur, J. 1961. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from micro-organisms. J. Mol. Biol. 3:208-218. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nooh, M. M., R. K. Aziz, M. Kotb, A. Eroshkin, W. J. Chuang, T. Proft, and R. Kansal. 2006. Streptococcal mitogenic exotoxin, SmeZ, is the most susceptible M1T1 streptococcal superantigen to degradation by the streptococcal cysteine protease, SpeB. J. Biol. Chem. 281:35281-35288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norrby-Teglund, A., M. Norgren, S. E. Holm, U. Andersson, and J. Andersson. 1994. Similar cytokine induction profiles of a novel streptococcal exotoxin, MF, and pyrogenic exotoxins A and B. Infect. Immun. 62:3731-3738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paillot, R., C. Robinson, K. Steward, N. Wright, T. Jourdan, N. Butcher, Z. Heather, and A. Waller. 2010. Contribution of each of four superantigens to Streptococcus equi-induced mitogenicity, IFN gamma synthesis and immunity. Infect. Immun. 78:1728-1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pesavento, P. A., K. F. Hurley, M. J. Bannasch, S. Artiushin, and J. F. Timoney. 2008. A clonal outbreak of acute fatal hemorrhagic pneumonia in intensively housed (shelter) dogs caused by Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus. Vet. Pathol. 45:51-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Proft, T., and J. D. Fraser. 2003. Bacterial superantigens. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 133:299-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Proft, T., P. D. Webb, V. Handley, and J. D. Fraser. 2003. Two novel superantigens found in both group A and group C Streptococcus. Infect. Immun. 71:1361-1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rutherford, K., J. Parkhill, J. Crook, T. Horsnell, P. Rice, M. A. Rajandream, and B. Barrell. 2000. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 16:944-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salasia, S. I., I. W. Wibawan, F. H. Pasaribu, A. Abdulmawjood, and C. Lammler. 2004. Persistent occurrence of a single Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus clone in the pig and monkey population in Indonesia. J. Vet. Sci. 5:263-265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharp, M. W., M. J. Prince, and J. Gibbens. 1995. S. zooepidemicus infection and bovine mastitis. Vet. Rec. 137:128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shupp, J. W., M. Jett, and C. H. Pontzer. 2002. Identification of a transcytosis epitope on staphylococcal enterotoxins. Infect. Immun. 70:2178-2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith, K. C., A. S. Blunden, K. E. Whitwell, K. A. Dunn, and A. D. Wales. 2003. A survey of equine abortion, stillbirth and neonatal death in the UK from 1988 to 1997. Equine Vet. J. 35:496-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soedarmanto, I., F. H. Pasaribu, I. W. Wibawan, and C. Lammler. 1996. Identification and molecular characterization of serological group C streptococci isolated from diseased pigs and monkeys in Indonesia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2201-2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sriskandan, S., L. Faulkner, and P. Hopkins. 2007. Streptococcus pyogenes: Insight into the function of the streptococcal superantigens. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39:12-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stevenson, R. G. 1974. Streptococcus zooepidemicus infection in sheep. Can. J. Comp. Med. 38:243-250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamura, K., J. Dudley, M. Nei, and S. Kumar. 2007. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24:1596-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tettelin, H., V. Masignani, M. J. Cieslewicz, J. A. Eisen, S. Peterson, M. R. Wessels, I. T. Paulsen, K. E. Nelson, I. Margarit, T. D. Read, L. C. Madoff, A. M. Wolf, M. J. Beanan, L. M. Brinkac, S. C. Daugherty, R. T. DeBoy, A. S. Durkin, J. F. Kolonay, R. Madupu, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, N. B. Fedorova, D. Scanlan, H. Khouri, S. Mulligan, H. A. Carty, R. T. Cline, S. E. Van Aken, J. Gill, M. Scarselli, M. Mora, E. T. Iacobini, C. Brettoni, G. Galli, M. Mariani, F. Vegni, D. Maione, D. Rinaudo, R. Rappuoli, J. L. Telford, D. L. Kasper, G. Grandi, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. Complete genome sequence and comparative genomic analysis of an emerging human pathogen, serotype V Streptococcus agalactiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:12391-12396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tokura, Y., F. Furukawa, H. Wakita, H. Yagi, T. Ushijima, and M. Takigawa. 1997. T-cell proliferation to superantigen-releasing Staphylococcus aureus by MHC class II-bearing keratinocytes under protection from bacterial cytolysin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 108:488-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Webb, K., K. A. Jolley, Z. Mitchell, C. Robinson, J. R. Newton, M. C. Maiden, and A. Waller. 2008. Development of an unambiguous and discriminatory multilocus sequence typing scheme for the Streptococcus zooepidemicus group. Microbiology 154:3016-3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wood, J. L., M. H. Burrell, C. A. Roberts, N. Chanter, and Y. Shaw. 1993. Streptococci and Pasteurella spp. associated with disease of the equine lower respiratory tract. Equine Vet. J. 25:314-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wood, J. L., J. R. Newton, N. Chanter, and J. A. Mumford. 2005. Association between respiratory disease and bacterial and viral infections in British racehorses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:120-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.