Abstract

Shigella flexneri is a facultative intracellular pathogen that invades and disrupts the colonic epithelium. In order to thrive in the host, S. flexneri must adapt to environmental conditions in the gut and within the eukaryotic cytosol, including variability in the available carbon sources and other nutrients. We examined the roles of the carbon consumption regulators CsrA and Cra in a cell culture model of S. flexneri virulence. CsrA is an activator of glycolysis and a repressor of gluconeogenesis, and a csrA mutant had decreased attachment and invasion of cultured cells. Conversely, Cra represses glycolysis and activates gluconeogenesis, and the cra mutant had an increase in both attachment and invasion compared to the wild-type strain. Both mutants were defective in plaque formation. The importance of the glycolytic pathway in invasion and plaque formation was confirmed by testing the effect of a mutation in the glycolysis gene pfkA. The pfkA mutant was noninvasive and had cell surface alterations as indicated by decreased sensitivity to SDS and an altered lipopolysaccharide profile. The loss of invasion by the csrA and pfkA mutants was due to decreased expression of the S. flexneri virulence factor regulators virF and virB, resulting in decreased production of Shigella invasion plasmid antigens (Ipa). These data indicate that regulation of carbon metabolism and expression of the glycolysis gene pfkA are critical for synthesis of the virulence gene regulators VirF and VirB, and both the glycolytic and gluconeogenic pathways influence steps in S. flexneri invasion and plaque formation.

The Gram-negative bacterium Shigella flexneri is a causative agent of shigellosis, a severe infection of the colonic epithelium. S. flexneri is primarily transmitted between hosts via the fecal-oral route to its infective site in the colon. Following attachment to colonic epithelial cells, S. flexneri induces its own uptake and replicates in the host cell cytosol. The bacterium then spreads directly to adjacent epithelial cells, thereby propagating itself within the intestinal epithelium (24). S. flexneri invasion requires genes on the 220-kb virulence plasmid (50, 51). These include the Ipa effectors necessary for bacterial entry into colonic epithelial cells (32) and the type III secretion system that delivers the effectors to the host cytosol (3, 33, 34, 65).

The ability of S. flexneri to sense and respond to environmental changes is an important aspect of its pathogenesis. During intracellular growth, S. flexneri modulates expression of over one-quarter of its genes (30), including genes required for carbon source uptake and utilization (30, 45). The gene encoding the hexose-phosphate transporter, uhpT, was significantly upregulated in S. flexneri growing inside the eukaryotic cell (30, 45). This transport system should allow intracellular shigellae to take up glucose-phosphate for glycolysis, yet the expression of glycolytic genes was downregulated in the bacteria during intracellular growth (30). This may indicate that S. flexneri consumes both glycolytic and nonglycolytic carbon sources during intracellular growth, perhaps at different stages of an infection. Little is known about Shigella carbon metabolism in the colon, a site at which the bacterial cells are adapting to the host environment and initiating expression of genes required for invasion of the epithelium. Carbon metabolism regulators may coordinate expression of central carbon metabolism with external nutrient availability and bacterial metabolic demands. Regulators of central carbon metabolism have been studied in detail in Escherichia coli K-12, and this pathway was used as the basis for analysis of the close relative S. flexneri.

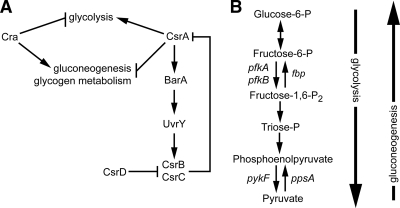

The E. coli carbon storage regulator CsrA is a global regulator of cellular metabolism (Fig. 1 A) (43). CsrA acts posttranscriptionally to increase glycolysis while repressing both gluconeogenesis and glycogen metabolism (46). CsrA is a 6.8-kDa RNA-binding protein that functions as a homodimer to modulate mRNA stability (4, 11, 63). The mechanism by which CsrA inhibits the glycogen biosynthesis gene glgC has been studied in detail. CsrA binds two sites in the glgC mRNA 5′ leader sequence, one of which overlaps the Shine-Dalgarno sequence, interfering with ribosome loading and translation initiation (35) and enhancing decay of the message (4). CsrA acts as a positive regulator of glycolysis, and disruption of csrA led to decreased activity of the glycolytic enzymes glucose-6-phosphate isomerase, triose-phosphate isomerase, and enolase (46), although the mechanism by which CsrA positively regulates the activity of these enzymes has not been fully determined (66).

FIG. 1.

E. coli central carbon metabolism is regulated by CsrA and Cra. (A) The transcriptional regulator Cra inhibits expression of glycolytic genes while activating expression of genes involved in gluconeogenesis. CsrA regulates stability of mRNAs for genes involved in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis. The noncoding RNAs CsrB and CsrC sequester the CsrA protein from its targets. Expression of csrB and csrC is induced by the BarA-UvrY two-component system, which is activated by CsrA. CsrD decreases the stability of both CsrB and CsrC. Based on their genetic relatedness and the data gathered in this study, CsrA and Cra likely regulate metabolism similarly in S. flexneri and E. coli. (Illustration modified from reference 2 with permission of the publisher). (B) Irreversible steps in the metabolic pathways allow for independent regulation of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis. The opposing effects of CsrA and Cra are due in part to their reciprocal regulation of the glycolytic gene pfkA and the gluconeogenic gene ppsA.

The noncoding RNAs CsrB and CsrC regulate the activity of CsrA by sequestering the protein and preventing its binding to target mRNAs (54, 67) (Fig. 1A). E. coli CsrB contains 22 copies of the predicted CsrA-binding site, whereas CsrC contains 9 copies (67). Expression of csrB and csrC is activated by the BarA-UvrY two-component system, which is regulated by CsrA. In response to signals, including the sugar metabolism end products formate and acetate (9), the histidine kinase BarA phosphorylates its cognate response regulator UvrY, which activates transcription of both csrB and csrC (39, 53). The levels of CsrB and CsrC are regulated by CsrD protein, which promotes RNaseE-dependent turnover of CsrB and CsrC (25, 53). By stimulating production of BarA, leading to increased levels of its antagonists, CsrA autoregulates its activity via a larger feedback pathway.

An additional carbon metabolism regulator, Cra, inhibits expression of genes involved in glycolysis while activating expression of gluconeogenic genes (47). Thus, the effect of Cra on carbon metabolism is opposite that of CsrA (Fig. 1A). Cra is a transcriptional regulator that binds to palindromic sequences in the operators of genes in its regulon. The effect of Cra on gene expression is influenced by the position of the Cra operator sequence relative to the RNA polymerase-binding site. If Cra binds upstream of the RNA polymerase-binding site, Cra promotes transcription of the downstream operon. However, if the Cra-binding site overlaps or is downstream of the polymerase-binding site, Cra inhibits transcription (47). Additionally, glycolytic metabolites affect Cra activity, as binding of the glycolytic metabolites fructose-1-phosphate or fructose-1,6-bisphosphate to Cra prevent it from binding its DNA targets (42).

One of the primary control points of CsrA and Cra regulation is phosphofructokinase (Pfk). Although several reversible enzymes function in both glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, the reaction catalyzed by the glycolytic enzyme Pfk is irreversible under physiological conditions (Fig. 1B). Pfk catalyzes the phosphorylation of fructose-1-phosphate to fructose-1,6-bisphosphate. In E. coli, the major enzyme, PfkI, encoded by the pfkA gene, accounts for 90% of total cellular phosphofructokinase activity (19). CsrA and Cra control the glycolytic and gluconeogenic pathways by regulating the level of PfkI and a second enzyme, Pps, which converts pyruvate to phosphoenolpyruvate (46, 48) (Fig. 1B).

Optimal growth and survival of S. flexneri in its host likely require both efficient utilization of available carbon sources and rapid response to changing carbon sources. This work examines the role of CsrA and Cra in S. flexneri pathogenesis in a cell culture model and demonstrates that expression of the glycolysis gene pfkA is required for synthesis of S. flexneri virulence proteins and invasion of cultured cells. The effect on virulence occurs at the level of VirF and VirB, the master regulators of S. flexneri virulence gene expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and growth conditions.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are shown in Table 1. All strains were routinely maintained at −80°C in tryptic soy broth (TSB) supplemented with 20% (vol/vol) glycerol. E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl) or on LB agar plates. S. flexneri was grown on TSB agar containing 0.01% (wt/vol) Congo red (CR) to select CR+ colonies. For assays comparing the wild-type and mutant strains, isolated colonies from Congo red agar were inoculated into LB broth and grown at 37°C with shaking to exponential phase (A650, 0.75 to 0.80). The growth rates were monitored by measuring the A650, and under these conditions, the growth rates for the wild-type and mutant strains were the same. Antibiotics were added at the following concentrations per milliliter: 25 μg ampicillin, 30 μg chloramphenicol, 1.6 μg tetracycline, and 50 μg kanamycin. To examine glycogen accumulation, bacteria were grown on Kornberg medium agar (1.1% K2HPO4, 0.85% KH2PO4, 0.6% yeast extract) containing 1% (wt/vol) glucose. Plates were then inverted over iodine crystals to stain accumulated glycogen with iodine vapor (44).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source and/or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| JW0078 | cra::Kan | Keio collection (1) |

| JW1899 | uvrY::Kan | Keio collection |

| JW2757 | barA::Kan | Keio collection |

| JW3221 | csrD::Kan | Keio collection |

| JW3887 | pfkA::Kan | Keio collection |

| TRMG1655 | csrA::Kan | 44 |

| RG1-B | csrB::Cm | 15 |

| TWMG1655 | csrC::Tet | 68 |

| S. flexneri 2a strains | ||

| 2457T | Wild type | Walter Reed Army Institute of Research |

| AGS100 | 2457T barA::Kan | This study |

| AGS110 | 2457T uvrY::Kan | This study |

| AGS120 | 2457T csrA::Kan | This study |

| AGS130 | 2457T csrB::Cm | This study |

| AGS140 | 2457T csrC::Tet | This study |

| AGS150 | 2457T csrD::Kan | This study |

| AGS190 | 2457T cra::Kan | This study |

| AGS220 | 2457T pfkA::Kan | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-T Easy | PCR cloning vector | Promega |

| pQE2 | Cloning vector; IPTG-inducible expression from T5 promoter | Qiagen |

| pWKS30 | Low-copy-number cloning vector | 63 |

| pWSK29 | Low-copy-number cloning vector | 63 |

| pQCsrB | 2457T csrB in pQE2 | This study |

| pQCsrC | 2457T csrC in pQE2 | This study |

| pQCsrA | 2457T csrA in pQE2 | This study |

| pWCsrA | 2457T csrA in pWSK29 | This study |

| pWCra | 2457T cra in pWKS30 | This study |

| pWPfkA | 2457T pfkA in pWSK29 | This study |

Henle cells (intestinal 407; American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in minimal essential medium (MEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% Bacto tryptone phosphate broth (Difco, Becton Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ), 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 2 mM glutamine, and 1× nonessential amino acids (Gibco). Henle cells were incubated at 37°C with 95% air-5% CO2.

Bacterial strains and techniques.

All S. flexneri mutant strains were derived by bacteriophage P1 transduction of the indicated E. coli mutations into the S. flexneri 2a strain 2457T. E. coli strains TRMG1655 (csrA::Kan), TWMG1655 (csrC::Tet), and RG1-B (csrB::Cm) were kindly provided by T. Romeo (16, 67). The barA, uvrY, csrD (yhdA), cra, and pfkA mutations were transduced from strains in the Keio collection (1). For each mutant, replacement of the wild-type allele was confirmed by PCR analysis.

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Primers used in this study are listed in Table 2. The csrA expression plasmid pQCsrA was constructed by cloning the wild-type S. flexneri csrA gene under the control of the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter in the expression plasmid pQE2 (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). S. flexneri csrA was amplified from the chromosome of 2457T using primers csrA-fwd-BseRI and csrA-rev-HindIII. The amplified fragment was digested with BseRI and HindIII and cloned into similarly digested pQE2. To construct plasmids overexpressing csrB or csrC, the genes were amplified from 2457T using primers pQCsrB-fwd and pQCsrB-rev and pQCsrC-fwd and pQCsrC-rev, respectively, and initially cloned in pGEM-T Easy (Promega). The cloned fragments subsequently were excised using HindIII and EcoRI and ligated into similarly digested pQE2, thereby creating pQCsrB and pQCsrC.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| csrA-fwd-BseRI | 5′-ATCTGAGGAGCAGCAAAGTATGCTGATTCTG-3′ |

| csrA-rev-HindIII | 5′-AAGCTTGGGTGCGTCTCACCGATAAAG-3′ |

| pQCsrB-fwd | 5′-GAATTCTATCTTCGTCGACAGG-3′ |

| pQCsrB-rev | 5′-AAGCTTAAAACTGCCGCGAAGGATAGC-3′ |

| pQCsrC-fwd | 5′-GAATTCCAAAGGCGTAAAGTAGCACCC-3′ |

| pQCsrC-rev | 5′-AAGCTTCTTTTGCATGACCTTTGCTGCG-3′ |

| pWPfkA-fwd | 5′-GTGGACAGGGAGGGTAAACGGTCTATG-3′ |

| pWPfkA-rev | 5′-GCGGCCGCCTTGCGGGTATATGTTGAGGG-3′ |

| pWCra-fwd | 5′-GAATTCTGCGAAATCAGTGGGAAC-3′ |

| pWCra-rev | 5′-GCGGCCGCGTTGGCAGCATTACCTTG-3′ |

| For real-time PCR | |

| virB2-for | 5′-TCCAATCGCGTCAGAACTTAACT-3′ |

| virB2-rev | 5′-CCTTTAATATTGGTAGTGTAGAACTAAGAGATTC-3′ |

| virB2 probe | FAM-5′-AGGACTTGAAAAGGC-3′-MGBNFQ |

| VirF-fwd | 5′-TCGATAGCTTCTTCTCTTAGTTTTTCTG-3′ |

| VirF-rev | 5′-GAAAGACGCCATCTCTTCTCGAT-3′ |

| VirF probe | FAM-5′-TCAGATAAGGAAGATTGTTGAAA-3′-MGBNFQ |

pWPfkA was constructed by amplifying wild-type pfkA from S. flexneri 2457T using primers pWPfkA-fwd and pWPfkA-rev. The resulting PCR fragment was cloned into pGEM-T Easy, creating pGWPfkA. The pfkA fragment was excised from pGWPfkA using SalI and NotI and ligated into similarly digested pWSK29 (62). To construct pWCra, cra was amplified from the chromosome of 2457T using primers pWCra-fwd and pWCra-rev and then cloned into pGEM-T Easy. The cra fragment was excised from pGEM-T Easy by digesting with EcoRI and NotI and ligating the product into similarly cut pWKS30 (62). All plasmid inserts were sequenced using an ABI 3130 sequencer (Applied Biosystems) at the University of Texas at Austin DNA sequencing facility.

Cell culture assays.

Invasion assays were performed using a modification of the method of Hong et al. (23). Briefly, CR+ colonies from an overnight TSB agar plate containing 0.01% (wt/vol) Congo red were inoculated into LB broth and grown at 37°C with aeration to exponential phase (A650, 0.75 to 0.8). Approximately 2 × 108 bacteria were added to a subconfluent monolayer of Henle cells in 35-mm six-well polystyrene plates (Corning) and centrifuged for 10 min at 700 × g. The monolayers were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 5% CO2 and then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS-D; 1.98 g KCl, 8 g NaCl, 0.02 g KH2PO4, and 1.4g K2HPO4 per liter; pH 7.5) to remove extracellular bacteria. Two milliliters of MEM supplemented with 20 μg/ml gentamicin was added. Plates were incubated an additional 40 min, then washed with PBS-D and stained with Wright-Giemsa stain (Camco, Ft. Lauderdale, FL). Internalized bacteria were visualized by microscopy at ×600 magnification. At least 300 Henle cells were examined per well, and those containing three or more internal bacteria were scored positive for invasion.

To measure bacterial attachment, S. flexneri strains were grown as described for the invasion assay. Approximately 2 × 108 bacteria were added to a subconfluent monolayer of Henle cells. Plates were centrifuged for 5 min at 700 × g and then incubated for 15 min at 37°C in 5% CO2 prior to washing with PBS-D and staining as described above. Adherent bacteria were counted via microscopy. The total number of bacteria present per 100 Henle cells was recorded for each strain.

The plaque assays were performed as previously described (17, 22). In brief, 1 × 105 bacteria were added to confluent monolayers of Henle cells cultured in six-well polystyrene plates (Corning). Following the initial incubation, monolayers were washed and overlaid with MEM containing 0.3% glucose and 40 μg/ml gentamicin. After 48 h of incubation, wells were washed with PBS-D and stained with Wright-Giemsa.

Analysis of Ipa.

S. flexneri strains were grown in LB broth to exponential phase as for the invasion assay, collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in Laemmli buffer at a concentration of 1 × 1010 bacteria per ml. Samples were boiled for 5 min, and the proteins in lysates from equal numbers of cells were separated by SDS-12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (37) or transferred to a 0.45-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond-ECL; GE Healthcare) for Western blotting as described previously (18). Membranes were probed with mouse monoclonal anti-IpaB or mouse monoclonal anti-IpaC antibodies (generously provided by E. V. Oaks, WRAIR), followed by goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Bio-Rad). Signal was detected by developing the blot with a Pierce enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection kit (Pierce).

Analysis of lipopolysaccharide.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) extraction was performed following the protocol of Hitchcock and Brown (21). Strains were grown in LB broth as for the invasion assay, and 1 × 109 bacteria were harvested by centrifugation. Pellets were resuspended in 50 μl of lysis buffer (21) and boiled for 10 min. A total of 25 μg of proteinase K was added, and samples were incubated at 65°C for 1 h. Samples were boiled an additional 5 min and separated by 12% tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. LPS was visualized by silver staining (58).

Detergent sensitivity assay.

SDS sensitivity was determined as described by Hong et al. (22). Bacteria were grown in LB broth as for the invasion assay. The culture was centrifuged at 16,300 × g for 5 min and then resuspended in 25 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, to a final A650 of 1.0. SDS was added to a final concentration of 0.1% to one set of samples per strain. Samples were incubated at 37°C without aeration, and the ratio of absorbance at each time point (Tn) versus the absorbance at time zero (T0) was determined and expressed as a percentage (relative to the A650). Data shown are from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate.

Real-time PCR.

RNA was isolated from exponential-phase bacteria grown as described for the invasion assay using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and then treated with DNase I (Invitrogen) to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. The RNA was quantified using an ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE), and a total of 2 μg of RNA was used to make cDNA by using the High-Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). cDNA was diluted 1:10 in diethyl pyrocarbonate-H2O, and 2.5 μl of diluted cDNA was used as template in a 25-μl real-time PCR mixture. TaqMan Universal master mix (Applied Biosystems) was used for all real-time PCRs. Primers and probes were designed using Primer Express (Applied Biosystems), and probes used were labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM) and minor groove-binding nonfluorescent quencher (MGBNFQ). Reactions were performed in a 7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) under standard reaction conditions. All data were normalized to the level of dksA cDNA in the sample.

Intracellular ATP.

The intracellular ATP levels of the wild-type and mutant strains of S. flexneri were measured using the ATP bioluminescence assay kit HS II (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) following the manufacturer's protocol. Strains were grown in LB broth to exponential phase as in the invasion assay, diluted 1:10 into dilution buffer, and lysed using the provided cell lysis reagent. Following addition of the luciferase reagent, the light signal was integrated for 10 s with a 1-s delay. All measurements were within the linear range as determined for an ATP standard curve.

RESULTS

An S. flexneri csrA mutant is defective in invasion.

To assess the role of CsrA in S. flexneri virulence, a csrA mutant was constructed by transduction of the csrA::Kan mutation from E. coli TRMG1655 (44) into S. flexneri 2457T. The transposon insertion site in TRMG1655 is located near the 3′ end of the csrA open reading frame, and the strain has partial CsrA activity. TRMG1655 is defective in glycogen metabolism, leading to a 20-fold increase in glycogen stores (69) but, unlike a csrA null mutant, it shows wild-type growth in rich medium (44, 46, 55). The S. flexneri csrA::Kan mutant AGS120 had the same phenotypes as TRMG1655 in that it grew well in rich medium and appeared to have increased internal glycogen stores as detected by iodine staining (data not shown).

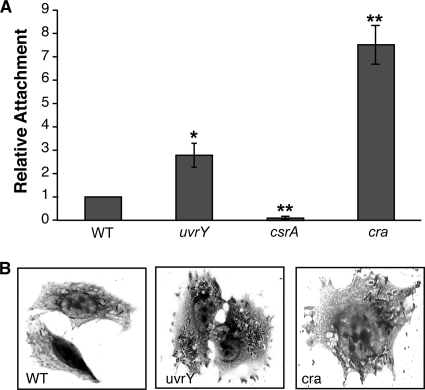

The S. flexneri csrA mutant was assessed for its effect on phenotypes correlated with S. flexneri virulence, including adherence, invasion, and cell-to-cell spread in cultured epithelial cells. The csrA mutant was severely impaired in invasion of Henle cells (Table 3). The invasion defect in the csrA mutant correlated with reduced attachment to the Henle cells, compared to the parental strain (Fig. 2 A). As expected based on the attachment and invasion data, the S. flexneri csrA mutant formed fewer plaques in the epithelial cell monolayers (Table 3). Moreover, the plaques formed by the csrA mutant were smaller and more turbid than those of the wild type (Table 3), indicating a defect in intracellular multiplication or cell-to-cell spread.

TABLE 3.

CsrA and Cra influences on S. flexneri virulence in cell culture assays

| Strain | Genotype | % wild type invasiona | Plaque morphology and relative no.b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2457T | Wild type | 100 | + |

| AGS120 | csrA::Kan | 5 ± 4 | pp, <10% WT |

| AGS120/pQCsrA | csrA::Kan/pQCsrAc | 47 ± 6 | pp, ∼20% WT |

| AGS190 | cra::Kan | 131 ± 13 | pp |

| AGS190/pWCra | cra::Kan/pWCra | 90 | + |

| AGS100 | barA::Kan | 98 ± 9 | + |

| AGS110 | uvrY::Kan | 143 ± 10 | + |

| AGS130 | csrB::Cm | 111 ± 10 | + |

| AGS140 | csrC::Tet | 126 ± 5 | + |

| AGS150 | csrD::Kan | 43 ± 10 | <10% WT |

| 2457T/pQCsrB | pQCsrBc (CsrB overexpression) | 53 | ND |

| 2457T/pQCsrC | pQCsrCc (CsrC overexpression) | 53 | ND |

| AGS220 | pfkA::Kan | 0 | − |

| AGS220/pWPfkA | pfkA::Kan/pWPfkA | 77 ± 10 | + |

Percentage of Henle cells with ≥3 intracellular bacteria. Invasion rates for wild-type (WT) strain 2457T ranged from 70 to 85% in different experiments, and values for the other strains were normalized to the invasion percentage of the wild type within each experiment. At least 300 Henle cells were counted in each experiment, and the values given are averages ± 1 standard deviation of three independent experiments each performed in triplicate. The data shown for complementation of csrA and cra and for csrB and csrC overexpression are averages of two independent experiments performed in triplicate.

+, clear plaques of ∼1.5 mm, number of plaques equivalent to WT (100 to 200 plaques/well); pp, pinpoint turbid plaques with diameter of <0.5 mm; −, no visible plaques; ND, not determined. The relative number of plaques (as a percentage) is based on the number of plaques formed by the WT in the same experiment.

Expression was induced by addition of 200 μM IPTG.

FIG. 2.

CsrA and Cra influence S. flexneri attachment to epithelial cells. (A) Equivalent numbers of each strain were added to subconfluent monolayers and allowed to attach for 15 min prior to washing and staining. The total number of bacteria attached to 100 Henle cells was determined for each strain. Strains tested were 2457T (WT), AGS110 (uvrY), AGS120 (csrA), and AGS190 (cra). Values were normalized to the wild-type attachment level for each experiment. Wild-type adherence was 60 to 90 bacteria/100 cells (average, 0.8 bacteria/cell). Data presented are the mean values with standard deviations for three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05, and **, P < 0.01, compared to WT (by Student's t test). (B) Representative images from bacterial invasion of Henle cells by 2457T (WT), AGS110 (uvrY), or AGS190 (cra). Intracellular bacteria were visualized by Giemsa staining and microscopy.

Introduction of the cloned csrA gene on a plasmid only partially restored invasion and normal plaque phenotype (Table 3). The csrA mutant carrying the plasmid with the CsrA gene (pQCsrA) formed more plaques than the mutant strain, but these plaques were still smaller than those formed by wild-type S. flexneri (Table 3). Lack of full complementation may indicate that the level of CsrA produced by the plasmid is not optimal, or the chromosomal csrA::Kan allele may have a dominant negative effect, since this mutation results in production of a protein with partial CsrA activity (55).

Regulators of CsrA influence S. flexneri virulence.

To determine further the effects of CsrA levels on S. flexneri invasion and plaque formation, we constructed mutations in genes that alter the level of free CsrA. Because CsrB and CsrC sequester CsrA (Fig. 1A), we anticipated that loss of CsrB or CsrC would increase the amount of free CsrA. Disruption of csrB or csrC led to a modest increase in invasion by S. flexneri (Table 3), consistent with an increase in CsrA leading to more efficient invasion of the Henle cells. Conversely, overexpression of csrB or csrC from the IPTG-inducible promoter in pQE2 resulted in a decrease in invasion (Table 3), correlating with reduced CsrA levels. Another regulator of CsrA activity in E. coli, CsrD, promotes RNaseE-mediated degradation of CsrB and CsrC (Fig. 1A). Disruption of csrD decreases the decay rate of CsrB and CsrC, leading to increased levels of these RNAs and thus decreased levels of free CsrA (53). Consistent with csrB and csrC overexpression data, the S. flexneri csrD mutant was impaired in invasion compared to the wild type and formed fewer plaques than wild type (Table 3).

The BarA-UvrY two-component system stimulates expression of csrB and csrC (54, 67). In the absence of BarA or UvrY, levels of CsrB and CsrC decrease, thereby increasing the amount of free CsrA in E. coli (54, 67) (Fig. 1A). We therefore hypothesized that the absence of one or both components of the two-component system would increase Henle cell invasion by S. flexneri. A mutation in uvrY increased the percentage of Henle cells invaded by S. flexneri, consistent with decreased expression of csrB and csrC and a resultant increase in CsrA activity (Table 3). Moreover, Henle cells invaded by the uvrY mutant contained greater numbers of intracellular bacteria compared to the wild type (Fig. 2B). Because of its increased invasion, we examined the attachment of the uvrY mutant to epithelial cells. The increased invasion was accompanied by an increased attachment of the uvrY mutant to Henle cells (Fig. 2A). The barA mutant did not demonstrate any difference in invasion compared to wild type (Table 1). However, UvrY may be phosphorylated by another histidine kinase in the absence of BarA, thus mitigating the effects of a barA mutation on csrB and csrC expression (64).

Inhibition of S. flexneri invasion by the metabolic regulator Cra.

In contrast to CsrA, the transcriptional regulator Cra inhibits glycolysis and stimulates gluconeogenesis (Fig. 1A). We wanted to determine whether Cra would also have the opposite effect of CsrA on S. flexneri invasion. The cra mutant invaded a larger fraction of the Henle cells than the wild type (Table 3), and the invaded Henle cells each contained larger numbers of intracellular bacteria (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the increased invasion, the cra mutant showed a 7-fold increase in the average number of bacteria attached to each epithelial cell (Fig. 2A). In spite of the increased attachment and invasion, the plaques formed by the wild type were much smaller and more turbid than those made by the parental strain. In the invasion assay, it was noted that a large number of the intracellular bacteria appeared to remain within a vacuole (Fig. 2B), and this may contribute to inefficient plaque formation. Introduction of a plasmid carrying cra (pWCra) into the cra mutant reduced invasion to near-wild-type levels and restored wild-type plaque morphology (Table 3). The aberrant plaque morphology indicates that while Cra inhibits attachment and invasion, it is needed for optimal growth inside the host cell or for cell-to-cell spread.

The glycolytic enzyme PfkI is necessary for S. flexneri invasion.

The phenotypes of the csrA and cra mutants indicate that efficient attachment correlates with the amount of free CsrA and positive regulation of glycolysis. To test directly whether the invasion phenotypes of these regulatory mutants were due to altered levels of glycolysis, we made a mutation in a gene required for glycolysis, pfkA, which encodes phosphofructokinase (PfkI) (Fig. 1B). pfkA expression is positively regulated by CsrA (46) and is negatively regulated by Cra (10). If the invasion phenotypes of the csrA and cra mutants are due to their effects on glycolysis, then the pfkA mutant should have the same phenotype as the csrA mutant. The phenotype of the S. flexneri pfkA mutant was consistent with this model; the mutant did not invade Henle cells and subsequently failed to form plaques (Table 3). Expression of pfkA from the plasmid pWPfkA restored invasion of the pfkA mutant to near-wild-type levels and also restored plaque formation (Table 1). The invasion and plaque phenotypes of the pfkA mutant suggest that glycolysis is needed for invasion and virulence.

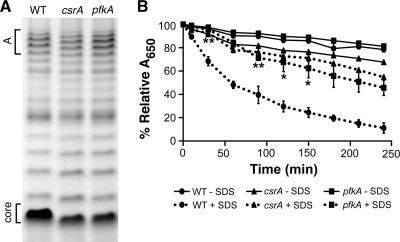

PfkI and CsrA affect the S. flexneri outer membrane.

A possible effect of altered carbon metabolism is changes in the structure of the S. flexneri LPS due to alterations in the intracellular pool of sugars available for LPS synthesis. Altered LPS affects virulence of S. flexneri (23, 36). IcsA, the bacterial protein needed for polar actin polymerization and intercellular spread, is aberrantly localized in rough mutants (36, 49, 59). The length and degree of glycosylation of the LPS also influence invasion by altering exposure of the type III secretion system (TTSS) needle (23, 68). To determine whether there were differences in the LPS structure, the LPS profiles of the csrA and pfkA mutants were compared to the wild type (Fig. 3 A). LPS molecules consisting of only the core migrate fastest in gel electrophoresis, while slower-migrating bands represent chains with increasing numbers of O-antigen repeats. Both the csrA and pfkA mutants produced LPS in which each repeat migrated faster than the wild type (Fig. 3A). The mutants had the typical pattern of chain length distribution, designated mode A (Fig. 3A), and both the csrA and pfkA mutants, like the wild type, had detectable amounts of the very long mode B chains (data not shown). This suggests that the LPS modifications seen in the pfkA and csrA mutants are a result of alterations in the lipid A or core oligosaccharide portion of LPS and not a change in the O-antigen distribution or length. A change in the cell surface of the csrA and pfkA mutants was also detected by measuring resistance to detergent. Both of these mutants were more resistant to SDS than the wild type (Fig. 3B). Deletion of cra had no discernible effects on the S. flexneri LPS profile or resistance to detergent (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Effects of CsrA and PfkA on S. flexneri LPS and sensitivity to SDS. (A) LPS was harvested from 2457T (WT), AGS120 (csrA), and AGS220 (pfkA). LPS samples from equal numbers of cells grown to exponential phase were separated on a 12% tricine-SDS-PAGE gel and visualized by silver staining. “Core” refers to the migration pattern of the LPS core without attached O-antigen repeats. Mode A is the LPS core with chains consisting of approximately 11 to 17 O-antigen repeats. (B) Strains 2457T (WT), AGS120 (csrA), and AGS220 (pfkA) were grown to exponential phase and washed with 1× PBS-D. A final concentration of 0.1% SDS was added to samples at T0. Absorbance (A650) was determined at 0 min, 10 min, and successive 30-min intervals for 4 h. The percent relative A650 was calculated as (A650 at Tn)/(A650 at T0) × 100. Data presented are the averages of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Error bars represent standard deviations. Detergent sensitivity of the mutant strains was compared to wild type by using an unpaired Student's t test. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

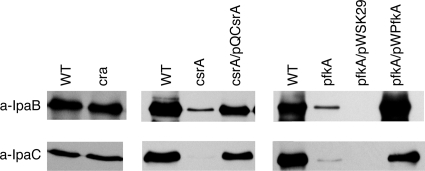

Ipa synthesis and secretion by the pfkA and csrA mutants.

Changes in LPS structure may influence the interaction between S. flexneri and epithelial cells, but the complete loss of invasiveness of the pfkA mutant is similar to the phenotype of mutants defective in the synthesis or presentation of the virulence plasmid-encoded invasion proteins. These proteins, IpaA, -B, -C, and -D, and the TTSS proteins (Mxi and Spa), responsible for their secretion (7) are essential for S. flexneri attachment, invasion, and vacuole lysis (24). The levels of two of the invasion proteins, IpaB and IpaC, were examined in the csrA and pfkA mutants by immunoblotting with monoclonal antibodies against IpaB or IpaC. The S. flexneri pfkA and csrA mutants produced greatly reduced amounts of the effectors compared to the parental strain (Fig. 4). Complementation with the wild-type genes on plasmids restored synthesis of both invasion proteins (Fig. 4). The failure of the csrA and pfkA mutants to synthesize IpaB and IpaC is consistent with the impaired invasion of these strains (Table 3). In contrast, the cra mutant produced IpaB and IpaC at levels similar to wild type (Fig. 4), indicating that the hyperinvasive phenotype was not a result of oversecretion of the invasion proteins.

FIG. 4.

Disruptions in glycolysis inhibit Ipa synthesis. (A) Strains tested were 2457T (WT), AGS120 (csrA), AGS220 (pfkA), AGS190 (cra), AGS120/pQCsrA, and AGS220, carrying either the empty vector (pWSK29) or the cloned pfkA gene (pWPkfA). Total cell extracts were prepared from exponential-phase cells and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with mouse monoclonal anti-IpaB or mouse monoclonal anti-IpaC antibody. Lysates from equal numbers of cells as determined by optical density were used.

Expression of virB and virF are decreased in the csrA and pfkA mutants.

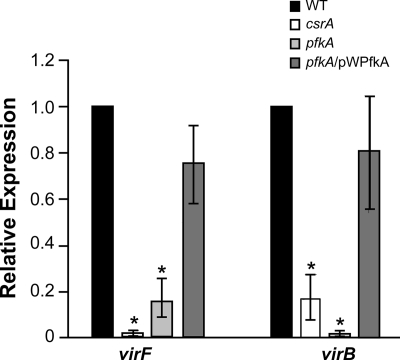

Expression of the ipa genes is controlled by the VirF-VirB regulatory cascade, which modulates their expression in response to several environmental factors, including osmolarity, pH, and temperature (5, 24, 41, 57). VirF activates transcription of virB, and VirB, in turn, activates expression of the invasion loci, including the ipa operon. virF and virB expression levels were examined in the csrA and pfkA mutants. As determined by real-time PCR, the amounts of virF and virB mRNA were reduced 5- to 100-fold in the mutants. Complementation of the pfkA mutation with the wild-type gene on a plasmid restored expression to near-wild-type levels (Fig. 5). The loss of Ipa synthesis is consistent with the reduced expression of virF. Reduced levels of VirF would lead to reduced virB expression and subsequent loss of activation of the virulence operons.

FIG. 5.

Expression levels of the virulence regulators virF and virB are significantly reduced in the csrA and pfkA mutants. Real-time PCR analysis of virF and virB expression was performed using strains S. flexneri 2457T (WT), AGS120 (csrA), AGS220 (pfkA), and AGS220/pWPfkA (PfkI+). Values are normalized to dksA in each sample, and results shown are relative to the value obtained for 2457T. Data presented are the averages of three or more independent experiments, and error bars represent 1 standard deviation. Relative expression was compared to the wild type by using Student's t test. *, P < 0.01.

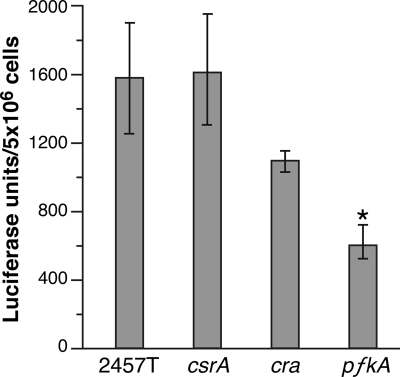

The mechanism by which csrA and pfkA affect expression of virF and the downstream genes is not clear. virF expression is influenced by DNA supercoiling, and the ATP/ADP ratio affects supercoiling (61). To determine whether modifications in central carbon metabolism caused by mutation of csrA or pfkA affect energy production, the levels of intracellular ATP were measured in aliquots of the same cultures used for determining vir gene expression by real-time PCR. The pfkA mutant, and to a lesser extent the cra mutant, showed reductions in intracellular ATP levels, but the csrA mutant had ATP concentrations equal to or greater than the wild type (Fig. 6). Thus, the pfkA mutation resulted in lower ATP levels, but this cannot explain the loss of virulence gene expression, since the csrA mutant, which also reduced virulence gene expression, had normal ATP levels.

FIG. 6.

Intracellular ATP levels in wild-type, csrA, and pfkA strains of S. flexneri. Samples of bacteria grown for measurement of virulence gene expression (Fig. 5) were lysed, and the intracellular ATP level was measured in a bioluminescence assay. ATP concentrations in the wild-type cells were ∼1.2 mM, based on comparison to ATP standards. Data shown are the averages of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 compared to the wild type (by Student's t test).

Alternatively, blocking glycolysis by mutation in pfkA may cause transient accumulation of the precursor, fructose-6-phosphate, or a decrease in the levels of intermediates or end products downstream of the block in the pathway. An increase in fructose-6-phosphate could lead to sugar phosphate stress, which is known to affect regulation of gene expression (13, 40, 60). To determine whether sugar phosphate stress affected expression of the S. flexneri virulence genes, the cells were grown in the presence of α-methylglucoside (0.25, 0.5, or 1.0%) to induce sugar phosphate stress (28) and assayed for Congo red binding. No differences were seen in Congo red binding by the wild-type strain in media with or without α-methylglucoside, indicating that accumulation of sugar phosphates did not suppress production of the virulence proteins.

DISCUSSION

S. flexneri encounters changes in environmental conditions during its transitions from the lumen of the gut to the subepithelial spaces and subsequently into the intracellular environment of the human host. To establish a successful infection, the bacterium must adapt to these environments, including coordinating expression of metabolic genes with nutrient availability. Acquiring and using available carbon sources is particularly important, and expression of genes involved in these pathways is highly regulated in the E. coli/Shigella group. We tested the role of the carbon regulators CsrA and Cra in S. flexneri virulence by constructing mutations in their genes and determining the phenotype of these mutants in cell culture assays. CsrA and Cra have opposite effects on glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, and mutations in the genes had opposite effects on the early stages of epithelial cell invasion. Mutation of csrA, which has been shown in E. coli to reduce glycolysis, led to decreased attachment and invasion, while the cra mutant, which had increased glycolysis, attached and invaded to a greater extent than wild type. This correlation between attachment/invasiveness and increased levels of CsrA could be seen throughout the CsrA regulatory circuit; mutations that led to increased CsrA (csrB, csrC, and uvrY) promoted attachment and invasion, while those that caused a decrease in CsrA (csrA and csrD) had reduced attachment and invasion to cultured cells. These data suggest that regulation of carbon metabolism and the metabolic state of the cell are critical determinants of S. flexneri invasion. A specific role of the glycolytic pathway was confirmed by making a mutation in pfkA which blocks glycolysis at an early step. The pfkA mutant showed reduced attachment and loss of invasion, indicating that a block in glycolysis led to reduced invasion.

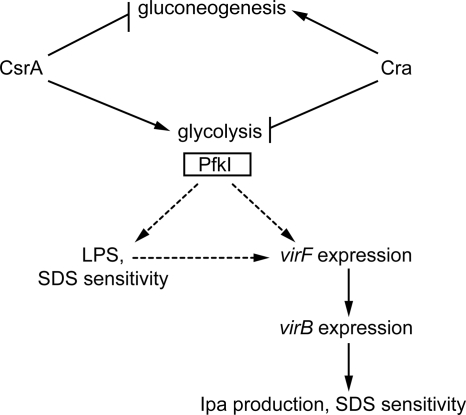

Loss of PfkA led to several changes in S. flexneri that could result in reduced invasion (Fig. 7). The major effect was the reduced expression of the virulence gene regulators virF and virB. The pfkA mutant had a 5-fold reduction in virF expression, and virB expression, which is positively regulated by VirF, was reduced almost 100-fold. Similarly, the csrA mutant had significantly lower levels of virF and virB expression than the wild-type strain. In the absence of VirB, there was little synthesis of IpaB and IpaC, which are essential for S. flexneri invasion.

FIG. 7.

Proposed model for regulation of S. flexneri pathogenesis by CsrA, Cra, and PfkI. Disruptions in glycolysis, caused by mutation of csrA or pfkA, reduce expression of virB and virF, leading to loss of Ipa production. Because all the virulence phenotypes of the csrA mutation are mimicked by the pfkA mutation, the effects of CsrA on attachment and invasion are likely due to its control of pfkA. Decreased expression levels of ipa and TTSS genes likely contribute to the increased resistance of the csrA and pfkA mutants to the detergent SDS. The altered LPS profile may also contribute to detergent resistance in the mutants, and these changes in the cell surface may influence the response of S. flexneri to environmental regulators of virF gene expression. Solid lines indicate known effects, and dashed lines indicate proposed effects based on the data presented.

The mechanism by which loss of glycolysis affects virF expression is not yet known. The VirF-VirB regulatory cascade is regulated by several environmental cues, including pH, osmolarity, and temperature (5, 41, 56). These environmental inputs are thought to influence DNA supercoiling and in turn affect topology and accessibility of the virF promoter. Because DNA supercoiling also is affected by the cell's energy charge (61), we determined the ATP levels in the mutant and wild type. However, the normal ATP levels in the csrA mutant indicated that this is unlikely to be the cause of poor virF expression. The csrA and pfkA mutations result in changes in carbon flux through the metabolic pathways in the bacterial cell, and increased or decreased amounts of a metabolic intermediate or product of one of these pathways may be a regulatory signal for virF expression.

It is possible that the alterations in the LPS and outer membrane structure caused by the csrA or pfkA mutations might affect the bacterium's ability to detect or respond to environmental signals such as osmolarity. Failure to detect the appropriate cues could prevent or delay the expression of virF. Alternatively, some changes in the outer membrane of the mutants, as measured by increased resistance to detergents, may be the result, rather than the cause, of reduced virulence gene expression. We had previously shown that there is a correlation between effector secretion and detergent sensitivity, as a Congo red-binding-negative strain defective in Ipa synthesis and secretion was more resistant to SDS than the virulent parent strain (22). The presence of the TTSS may reduce the stability of the outer membrane and increase sensitivity to detergents. Thus, the overall decrease in virulence gene expression in the pfkA and csrA mutants could account for both SDS resistance and decreased invasion. There was also a change in the migration of the LPS core. This change is not the direct result of decreased Ipa synthesis and secretion, since the Ipa synthesis mutant SA101 had the same LPS migration pattern as the wild type (data not shown). The altered LPS profile in the crsA and pfkA mutants may result from changes in the pools of sugars for LPS core modifications or altered expression of genes in the LPS biosynthetic pathway. These effects on LPS may further influence the interaction of S. flexneri with the host cells, as well as its ability to sense environmental cues for virulence gene expression.

In addition to the effect on invasion, the mutations reducing glycolysis also affected subsequent intracellular growth and cell-to-cell spread. The few plaques that were formed by the csrA mutant were smaller and more turbid than those of the wild type, suggesting a need for glycolysis subsequent to invasion. Reduced production of IpaB and IpaC may inhibit plaque formation in the csrA mutant, as these effectors have roles in both invasion and intercellular spread (33, 38). Synthesis of IpaB and IpaC is downregulated during the early stage of intracellular growth (18), but their production is required later for intercellular spread of the bacteria (52).

Although the cra mutant was highly invasive, it produced small, turbid plaques, indicating a defect in intracellular growth or cell-to-cell spread. This effect may be the result of reduced gluconeogenesis or aberrant upregulation of glycolysis in the intracellular environment. Although the eukaryotic cytosol is seemingly nutrient rich, it is not sufficient to support growth of noninvasive E. coli cells when they are microinjected into the cytosol (14). Thus, S. flexneri must be specifically adapted to growth within the cytosol, and this likely involves the ability to use a variety of carbon sources for optimal growth in this environment.

There is increasing evidence supporting a role for carbon metabolism in virulence (12, 27, 31). Interruption of the glycolytic pathway or the phosphotransferase transport system inhibits replication of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium within macrophage vacuoles (8). Carbohydrate metabolism has also been implicated in pathogenesis of enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), which is closely related to Shigella. In a cell culture model, an EIEC mutant defective in both glucose and mannose transport was significantly impaired in adherence and invasion (15). The intracellular pathogen Listeria monocytogenes appears to maximize its ability to grow intracellularly by using multiple carbon sources, such as glucose-6-phosphate and glycerol (26, 27). Glycolysis genes were downregulated and pentose phosphate cycle genes were upregulated in Listeria growing intracellularly, and mutational analysis supported a role for the pentose phosphate pathway during intracellular growth (27). Because of their roles in regulating these pathways, CsrA and Cra may exert an effect on invasion and replication of the bacteria within the host. Additionally, CsrA may regulate virulence gene expression more directly. In Yersinia enterocolitica, the Csr regulatory system regulates expression of the RovA virulence gene regulator, and a csrA mutant was defective in attachment to and invasion of HEp-2 cells (20). Similarly, csrA regulates the expression of virulence genes required for pedestal formation by enteropathogenic E. coli (6) and is required for expression of Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) invasion genes (29). S. flexneri appears to have adopted similar strategies, using CsrA and Cra to control carbon metabolism and virulence gene expression during the course of infection, in order to initiate invasion and subsequently maintain its replicative niche inside the host epithelial cell.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tony Romeo for providing strains TRMG1655, TWMG1655, and RG1-B and for helpful discussions. We also thank the National BioResource Project (NIG, Japan) for providing E. coli Keio mutant strains, Emily Helton for constructing plasmid pQCsrB, and Carolyn Fisher for construction of strain AGS110. Erin Murphy and Alexandra Mey provided assistance with real-time PCR. We thank Elizabeth Wyckoff and Alexandra Mey for critical review of the manuscript and helpful discussions.

This work was supported by NIH grant AI16935 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Editor: A. J. Bäumler

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 August 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baba, T., T. Ara, M. Hasegawa, Y. Takai, Y. Okumura, M. Baba, K. A. Datsenko, M. Tomita, B. L. Wanner, and H. Mori. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:2006.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babitzke, P., and T. Romeo. 2007. CsrB sRNA family: sequestration of RNA-binding regulatory proteins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:156-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahrani, F. K., P. J. Sansonetti, and C. Parsot. 1997. Secretion of Ipa proteins by Shigella flexneri: inducer molecules and kinetics of activation. Infect. Immun. 65:4005-4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker, C. S., I. Morozov, K. Suzuki, T. Romeo, and P. Babitzke. 2002. CsrA regulates glycogen biosynthesis by preventing translation of glgC in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 44:1599-1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernardini, M. L., A. Fontaine, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1990. The two-component regulatory system ompR-envZ controls the virulence of Shigella flexneri. J. Bacteriol. 172:6274-6281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatt, S., A. N. Edwards, H. T. Nguyen, D. Merlin, T. Romeo, and D. Kalman. 2009. The RNA binding protein CsrA is a pleiotropic regulator of the locus of enterocyte effacement pathogenicity island of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 77:3552-3568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blocker, A., N. Jouihri, E. Larquet, P. Gounon, F. Ebel, C. Parsot, P. Sansonetti, and A. Allaoui. 2001. Structure and composition of the Shigella flexneri “needle complex,” a part of its type III secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 39:652-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowden, S. D., G. Rowley, J. C. Hinton, and A. Thompson. 2009. Glucose and glycolysis are required for the successful infection of macrophages and mice by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 77:3117-3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chavez, R. G., A. F. Alvarez, T. Romeo, and D. Georgellis. 2010. The physiological stimulus for the BarA sensor kinase. J. Bacteriol. 192:2009-2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chin, A. M., D. A. Feldheim, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1989. Altered transcriptional patterns affecting several metabolic pathways in strains of Salmonella typhimurium which overexpress the fructose regulon. J. Bacteriol. 171:2424-2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubey, A. K., C. S. Baker, K. Suzuki, A. D. Jones, P. Pandit, T. Romeo, and P. Babitzke. 2003. CsrA regulates translation of the Escherichia coli carbon starvation gene, cstA, by blocking ribosome access to the cstA transcript. J. Bacteriol. 185:4450-4460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenreich, W., T. Dandekar, J. Heesemann, and W. Goebel. 2010. Carbon metabolism of intracellular bacterial pathogens and possible links to virulence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:401-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Kazzaz, W., T. Morita, H. Tagami, T. Inada, and H. Aiba. 2004. Metabolic block at early stages of the glycolytic pathway activates the Rcs phosphorelay system via increased synthesis of dTDP-glucose in Escherichia coli. Molecular Microbiology. 51:1117-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goetz, M., A. Bubert, G. Wang, I. Chico-Calero, J. A. Vazquez-Boland, M. Beck, J. Slaghuis, A. A. Szalay, and W. Goebel. 2001. Microinjection and growth of bacteria in the cytosol of mammalian host cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:12221-12226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gotz, A., and W. Goebel. 2010. Glucose and glucose 6-phosphate as carbon sources in extra- and intracellular growth of enteroinvasive Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. Microbiology 156:1176-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gudapaty, S., K. Suzuki, X. Wang, P. Babitzke, and T. Romeo. 2001. Regulatory interactions of Csr components: the RNA binding protein CsrA activates csrB transcription in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:6017-6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hale, T. L., E. V. Oaks, and S. B. Formal. 1985. Identification and antigenic characterization of virulence-associated, plasmid-coded proteins of Shigella spp. and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 50:620-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Headley, V. L., and S. M. Payne. 1990. Differential protein expression by Shigella flexneri in intracellular and extracellular environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:4179-4183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hellinga, H. W., and P. R. Evans. 1985. Nucleotide sequence and high-level expression of the major Escherichia coli phosphofructokinase. Eur. J. Biochem. 149:363-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heroven, A. K., K. Bohme, M. Rohde, and P. Dersch. 2008. A Csr-type regulatory system, including small non-coding RNAs, regulates the global virulence regulator RovA of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis through RovM. Mol. Microbiol. 68:1179-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hitchcock, P. J., and T. M. Brown. 1983. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J. Bacteriol. 154:269-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong, M., Y. Gleason, E. E. Wyckoff, and S. M. Payne. 1998. Identification of two Shigella flexneri chromosomal loci involved in intercellular spreading. Infect. Immun. 66:4700-4710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong, M., and S. M. Payne. 1997. Effect of mutations in Shigella flexneri chromosomal and plasmid-encoded lipopolysaccharide genes on invasion and serum resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 24:779-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jennison, A. V., and N. K. Verma. 2004. Shigella flexneri infection: pathogenesis and vaccine development. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28:43-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jonas, K., H. Tomenius, U. Romling, D. Georgellis, and O. Melefors. 2006. Identification of YhdA as a regulator of the Escherichia coli carbon storage regulation system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 264:232-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joseph, B., and W. Goebel. 2007. Life of Listeria monocytogenes in the host cells' cytosol. Microbes Infect. 9:1188-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joseph, B., K. Przybilla, C. Stuhler, K. Schauer, J. Slaghuis, T. M. Fuchs, and W. Goebel. 2006. Identification of Listeria monocytogenes genes contributing to intracellular replication by expression profiling and mutant screening. J. Bacteriol. 188:556-568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimata, K., Y. Tanaka, T. Inada, and H. Aiba. 2001. Expression of the glucose transporter gene, ptsG, is regulated at the mRNA degradation step in response to glycolytic flux in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 20:3587-3595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawhon, S. D., J. G. Frye, M. Suyemoto, S. Porwollik, M. McClelland, and C. Altier. 2003. Global regulation by CsrA in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1633-1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucchini, S., H. Liu, Q. Jin, J. C. Hinton, and J. Yu. 2005. Transcriptional adaptation of Shigella flexneri during infection of macrophages and epithelial cells: insights into the strategies of a cytosolic bacterial pathogen. Infect. Immun. 73:88-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marrero, J., K. Y. Rhee, D. Schnappinger, K. Pethe, and S. Ehrt. 2010. Gluconeogenic carbon flow of tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates is critical for Mycobacterium tuberculosis to establish and maintain infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:9819-9824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maurelli, A. T., B. Baudry, H. d'Hauteville, T. L. Hale, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1985. Cloning of plasmid DNA sequences involved in invasion of HeLa cells by Shigella flexneri. Infect. Immun. 49:164-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Menard, R., M. C. Prevost, P. Gounon, P. Sansonetti, and C. Dehio. 1996. The secreted Ipa complex of Shigella flexneri promotes entry into mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:1254-1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menard, R., P. Sansonetti, and C. Parsot. 1994. The secretion of the Shigella flexneri Ipa invasins is activated by epithelial cells and controlled by IpaB and IpaD. EMBO J. 13:5293-5302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mercante, J., A. N. Edwards, A. K. Dubey, P. Babitzke, and T. Romeo. 2009. Molecular geometry of CsrA (RsmA) binding to RNA and its implications for regulated expression. J. Mol. Biol. 392:511-528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morona, R., C. Daniels, and L. Van Den Bosch. 2003. Genetic modulation of Shigella flexneri 2a lipopolysaccharide O antigen modal chain length reveals that it has been optimized for virulence. Microbiology 149:925-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morrissey, J. H. 1981. Silver stain for proteins in polyacrylamide gels: a modified procedure with enhanced uniform sensitivity. Anal. Biochem. 117:307-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Page, A. L., H. Ohayon, P. J. Sansonetti, and C. Parsot. 1999. The secreted IpaB and IpaC invasins and their cytoplasmic chaperone IpgC are required for intercellular dissemination of Shigella flexneri. Cell. Microbiol. 1:183-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pernestig, A. K., D. Georgellis, T. Romeo, K. Suzuki, H. Tomenius, S. Normark, and O. Melefors. 2003. The Escherichia coli BarA-UvrY two-component system is needed for efficient switching between glycolytic and gluconeogenic carbon sources. J. Bacteriol. 185:843-853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Persson, O., A. Valadi, T. Nystrom, and A. Farewell. 2007. Metabolic control of the Escherichia coli universal stress protein response through fructose-6-phosphate. Mol. Microbiol. 65:968-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Porter, M. E., and C. J. Dorman. 1997. Differential regulation of the plasmid-encoded genes in the Shigella flexneri virulence regulon. Mol. Gen. Genet. 256:93-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramseier, T. M. 1996. Cra and the control of carbon flux via metabolic pathways. Res. Microbiol. 147:489-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romeo, T. 1998. Global regulation by the small RNA-binding protein CsrA and the non-coding RNA molecule CsrB. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1321-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Romeo, T., M. Gong, M. Y. Liu, and A. M. Brun-Zinkernagel. 1993. Identification and molecular characterization of csrA, a pleiotropic gene from Escherichia coli that affects glycogen biosynthesis, gluconeogenesis, cell size, and surface properties. J. Bacteriol. 175:4744-4755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Runyen-Janecky, L. J., and S. M. Payne. 2002. Identification of chromosomal Shigella flexneri genes induced by the eukaryotic intracellular environment. Infect. Immun. 70:4379-4388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sabnis, N. A., H. Yang, and T. Romeo. 1995. Pleiotropic regulation of central carbohydrate metabolism in Escherichia coli via the gene csrA. J. Biol. Chem. 270:29096-29104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saier, M. H., Jr., and T. M. Ramseier. 1996. The catabolite repressor/activator (Cra) protein of enteric bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 178:3411-3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saier, M. H., T. M. Ramseier, and J. Reizer. 1987. Regulation of carbon utilization, p. 1325-1343. In F. C. Neidhardt, J. Ingram, and R. Curtiss (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 49.Sandlin, R. C., M. B. Goldberg, and A. T. Maurelli. 1996. Effect of O side-chain length and composition on the virulence of Shigella flexneri 2a. Mol. Microbiol. 22:63-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sansonetti, P. J., D. J. Kopecko, and S. B. Formal. 1982. Involvement of a plasmid in the invasive ability of Shigella flexneri. Infect. Immun. 35:852-860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sasakawa, C., K. Kamata, T. Sakai, S. Y. Murayama, S. Makino, and M. Yoshikawa. 1986. Molecular alteration of the 140-megadalton plasmid associated with loss of virulence and Congo red binding activity in Shigella flexneri. Infect. Immun. 51:470-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schuch, R., R. C. Sandlin, and A. T. Maurelli. 1999. A system for identifying post-invasion functions of invasion genes: requirements for the Mxi-Spa type III secretion pathway of Shigella flexneri in intercellular dissemination. Mol. Microbiol. 34:675-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suzuki, K., P. Babitzke, S. R. Kushner, and T. Romeo. 2006. Identification of a novel regulatory protein (CsrD) that targets the global regulatory RNAs CsrB and CsrC for degradation by RNase E. Genes Dev. 20:2605-2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suzuki, K., X. Wang, T. Weilbacher, A. K. Pernestig, O. Melefors, D. Georgellis, P. Babitzke, and T. Romeo. 2002. Regulatory circuitry of the CsrA/CsrB and BarA/UvrY systems of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:5130-5140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Timmermans, J., and L. Van Melderen. 2009. Conditional essentiality of the csrA gene in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 191:1722-1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tobe, T., S. Nagai, N. Okada, B. Adler, M. Yoshikawa, and C. Sasakawa. 1991. Temperature-regulated expression of invasion genes in Shigella flexneri is controlled through the transcriptional activation of the virB gene on the large plasmid. Mol. Microbiol. 5:887-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tobe, T., M. Yoshikawa, T. Mizuno, and C. Sasakawa. 1993. Transcriptional control of the invasion regulatory gene virB of Shigella flexneri: activation by VirF and repression by H-NS. J. Bacteriol. 175:6142-6149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsai, C. M., and C. E. Frasch. 1982. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 119:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van den Bosch, L., P. A. Manning, and R. Morona. 1997. Regulation of O-antigen chain length is required for Shigella flexneri virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 23:765-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vanderpool, C. K., and S. Gottesman. 2007. The novel transcription factor SgrR coordinates the response to glucose-phosphate stress. J. Bacteriol. 189:2238-2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Workum, M., S. J. van Dooren, N. Oldenburg, D. Molenaar, P. R. Jensen, J. L. Snoep, and H. V. Westerhoff. 1996. DNA supercoiling depends on the phosphorylation potential in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 20:351-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang, R. F., and S. R. Kushner. 1991. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene 100:195-199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang, X., A. K. Dubey, K. Suzuki, C. S. Baker, P. Babitzke, and T. Romeo. 2005. CsrA post-transcriptionally represses pgaABCD, responsible for synthesis of a biofilm polysaccharide adhesin of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 56:1648-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wanner, B. L. 1992. Is cross regulation by phosphorylation of two-component response regulator proteins important in bacteria? J. Bacteriol. 174:2053-2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Watarai, M., T. Tobe, M. Yoshikawa, and C. Sasakawa. 1995. Contact of Shigella with host cells triggers release of Ipa invasins and is an essential function of invasiveness. EMBO J. 14:2461-2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wei, B. L., A. M. Brun-Zinkernagel, J. W. Simecka, B. M. Pruss, P. Babitzke, and T. Romeo. 2001. Positive regulation of motility and flhDC expression by the RNA-binding protein CsrA of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 40:245-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weilbacher, T., K. Suzuki, A. K. Dubey, X. Wang, S. Gudapaty, I. Morozov, C. S. Baker, D. Georgellis, P. Babitzke, and T. Romeo. 2003. A novel sRNA component of the carbon storage regulatory system of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 48:657-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.West, N. P., P. Sansonetti, J. Mounier, R. M. Exley, C. Parsot, S. Guadagnini, M. C. Prevost, A. Prochnicka-Chalufour, M. Delepierre, M. Tanguy, and C. M. Tang. 2005. Optimization of virulence functions through glucosylation of Shigella LPS. Science 307:1313-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang, H., M. Y. Liu, and T. Romeo. 1996. Coordinate genetic regulation of glycogen catabolism and biosynthesis in Escherichia coli via the CsrA gene product. J. Bacteriol. 178:1012-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]