Abstract

The Staphylococcus aureus SarA global regulator controls the expression of numerous virulence genes, often in conjunction with the agr quorum-sensing system and its effector RNA, RNAIII. In the present study, we have examined the role of both SarA and RNAIII on the regulation of the promoter of tst, encoding staphylococcal superantigen toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1). In vitro DNA-protein interaction studies with purified SarA using gel shift and DNase I protection assays revealed one strong SarA binding site and evidence for a weaker site nearby within the minimal 400-bp promoter region upstream of tst. In vivo analysis of tst promoter activation using a ptst-luxAB reporter inserted in the chromosome revealed partial but not complete loss of tst expression in a Δhld-RNAIII strain. In contrast, disruption of sarA abrogated tst expression. No significant tst expression was found for the double Δhld-RNAIII-ΔsarA mutant. Introduction of a plasmid containing cloned hld-RNAIII driven by a non-agr-dependent promoter, pHU, into isogenic parental wild-type or ΔsarA strains showed comparable levels of RNAIII detected by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) but a two-log10 reduction in ptst-luxAB reporter expression in the ΔsarA strain, arguing that RNAIII levels alone are not strictly determinant for tst expression. Collectively, our results indicate that SarA binds directly to the tst promoter and that SarA plays a significant and direct role in the expression of tst.

Staphylococcus aureus is a remarkable and feared human pathogen because of its ability to cause infections ranging from mild skin disease to life-threatening systemic illness. Once S. aureus gains access to subcutaneous tissues and is disseminated by the circulatory system, it can infect nearly every organ, leading to, for example, severe osteomyelitis, sepsis, abscesses, and endocarditis. S. aureus produces a wide array of toxins, such as hemolysins, Panton-Valentine leukocidin, and superantigens (SAg) such as enterotoxins, exfoliatins, or toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1) (32). The potential disease spectrum coupled with the emergence of drug resistance and its formidable arsenal of strategies to counter the host immune response makes S. aureus one of the leading causes of infectious disease morbidity and mortality worldwide (6, 12, 14, 32, 44).

Of particular interest are S. aureus toxinoses caused by the acquisition of mobile genetic elements encoding one or more toxins and their subsequent expression (33). Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is a potentially fatal illness whose principal clinical features are fever, skin rash, hypotension, and hemodynamic shock. Originally described as a tampon-related syndrome in young, healthy women, TSS cases are now associated with surgical infections (23, 31).

TSST-1 is encoded by the tst gene and is carried on at least three known mobile pathogenicity islands: SaPI1, SaPI2, and SaPIbov1 (22, 50). Although approximately 20% of S. aureus strains actually carry a pathogenicity island and thus have the genetic capacity of producing the toxin, the disease is fortunately rarely seen (24). This finding suggests that expression of tst is tightly regulated. The environmental triggers and molecular mechanisms that control the production of TSST-1 are complex and not fully understood. Multiple factors, such as glucose, pH, CO2, O2, NaCl, magnesium concentration, the α and β chains of hemoglobin, and TSST-1 itself, have been assessed and shown to affect toxin production (4, 19, 46, 48, 56, 59).

Glucose has been proposed to negatively regulate tst transcription and toxin production via CcpA, the glucose catabolite repressor, most likely through interaction with phosphorylated HPr. A putative CRE site, a cis-acting replication element for the binding of the CcpA-HPr complex, has been proposed for the tst promoter (48). Oxygen partial pressure has an effect on TSST-1 production possibly through the action of the SrrAB two-component system (37). SrrAB-imposed regulation may function in a dual manner, since studies suggest that SrrAB represses tst in anaerobic conditions and enhances its expression in aerobic conditions (36). The precise mechanisms that permit the detection of oxygen via SrrAB or other sensors in S. aureus remain elusive.

Virulence factors in S. aureus tend to be produced in postexponential phase of growth, whereas adhesive surface proteins are produced during exponential phase and downregulated postexponentially (6, 32). The temporal expression of virulence factors, including exotoxins, in S. aureus is under the control of a network of global regulators which include the quorum-sensing system agr via the agr effector molecule RNAIII, as well as the SarA protein family (8, 32, 40). Additional levels of control are imposed, for example, by numerous environmental-sensing systems of the two-component histidine kinase type (6, 16).

SarA is a 14.5-kDa dimeric DNA binding protein of the winged helix family, and transcriptional profiling has shown that it modulates, directly or indirectly, at least 120 genes in S. aureus (13, 26). DNA binding studies show that SarA binds to the agrP3 promoter region to positively modulate RNAIII expression, as well as to its own promoter region, where it imposes negative autoregulation (7, 10, 39). SarA has also been shown to bind the promoter regions of hla, fnbA, spa, sec, cna, ica, and trxB (1, 3, 11, 52).

The precise role of SarA and agr-RNAIII in the regulation of tst is presently unclear, although both global regulators modulate TSST-1 expression (6). Several studies suggest that the loss of RNAIII reduces TSST-1 production and dramatically reduces tst transcription (4, 40). Whether SarA modulates the tst promoter directly or indirectly via its positive regulation of RNAIII, or both, has been debated and is an open question (5, 32, 48, 57).

In the present work, we address this question both biochemically and genetically. We find that SarA binds to at least one site with high affinity in the tst promoter and possibly to a second one with less affinity. We show that disruption of sarA alone is far more deleterious to tst transcription than disruption of hld-RNAIII alone. SarA is thus a direct and major transcriptional regulator of tst gene expression. Our findings predict that factors which modulate SarA regulation will also concomitantly impact TSST-1 expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth and S. aureus strains were grown in Muller-Hinton broth (MHB) or brain heart infusion broth (BHI). Media were supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (40 μg/ml), tetracycline (3 μg/ml), or chloramphenicol (15 μg/ml) when appropriate. Recombinant lysostaphin was obtained from AMBI Products LLC (Lawrence, NY).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or characteristic(s) | Source/reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strain | ||

| DH5α | Routine laboratory strain | Gibco/BRL |

| S. aureus strains | ||

| RN4220 | Restriction-defective strain which accepts foreign DNA | 21 |

| RN4282 | Clinical strain harboring SaPI1 with tst | 22 |

| N315P | MRSA strain N315 lacking penicillinase plasmid | 20 |

| PC1072 | ptst-luxAB::geh Tcr | 4 |

| ALC2057 | RN6390 sarA::kan | 9 |

| WA400 | 8325-4 ΔRNAIII-hld region::cat | 18 |

| DA101 | PC1072 sarA::kan | This study |

| DA102 | PC1072 RNAIII::cam | This study |

| DA103 | PC1072 RNAIII::cam sarA::kan | This study |

| DA104 | PC1072/pDA201 | This study |

| DA105 | DA101/pDA201 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMK4 | E. coli-S. aureus shuttle plasmid, Camr Ampr | 51 |

| pBluescript II KS(+) | Cloning vector, Ampr | Stratagene |

| pDA200 | pMK4 containing NotI-Kpn Hu promoter region, Camr | This study |

| pDA201 | pDA200 containing a Kpn-Pst 0.5-kb fragment coding for RNAIII, Camr | This study |

| pDA301 | ptst 0.4-kb Kpn-Pst fragment in pKS+, Ampr | This study |

Construction of the strain PC1072 containing the ptst-luxAB transcriptional fusion has been described (4) and was kindly provided by Simon J. Foster, University of Sheffield, United Kingdom. Derivatives of PC1072 containing the various indicated gene disruptions were constructed by bacteriophage-mediated transduction using Φ80α and standard genetic procedures. The sarA::kan allele was transduced from donor strain ALC2057 (9), and the ΔRNAIII::cam allele was transduced from donor strain WA400 (18). Transductants were selected on kanamycin or chloramphenicol medium as necessary. All strain constructions were verified by PCR-based assays using appropriate primers. Genomic DNA extraction from S. aureus was performed on lysostaphin-treated samples by using the DNeasy kit (Qiagen) as described previously (41). DNA yields and purity were quantified using an ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., Rockland, DE). The presence or absence of functional RNAIII was also monitored using hemolytic assay of alpha-toxin production on sheep blood agar plates.

The tst promoter region from nucleotides −364 to +100 from SaPI1 in S. aureus N315P was amplified by the PCR using primers tst−364F and tst+100R and cloned into pBluescript KS(+) cleaved with Kpn and Pst to give plasmid pDA301. Following sequence verification, pDA301 served as template DNA for all subsequent PCR amplifications for tst promoter probe preparation.

Plasmids made using the E. coli-S. aureus shuttle vector pMK4 (51), containing RNAIII under the control of the heterologous pHU promoter, were constructed stepwise. Briefly, a synthetic polylinker was designed containing a unique series of restriction sites for the convenient insertion of promoter and gene combinations in modular form. This linker was introduced into pBluescript II KS(+) in place of the existing polylinker to create pMB. Spurious transcription emanating from upstream promoters in pMB was reduced by the insertion of an rrnBT1T2 terminator at the extreme margin of the polylinker. Promoter modules are inserted between NotI-Kpn sites, and gene cassettes are inserted downstream between Kpn-Pst sites. The expression cassette in pMB, once assembled, is excised with Mfe+BglII and inserted into pMK4 cut with EcoRI-BamHI. Details of the construction are available upon request. A plasmid, pWKD56f, containing the coding sequence of GFPuv4 under the control of the xylose-inducible promoter pXylR/A′, constructed using this strategy, has been previously described (54). A 200-bp NotI-Kpn fragment containing the S. aureus hu upstream promoter sequence was generated from PCR amplification from N315P genomic DNA using primers pHU-A and pHU-B and used to engineer pDA200. pDA201 is a derivative of pDA200 containing a 513-bp Kpn-Pst fragment with promoterless rnaIII prepared by PCR amplification using primers rnaIIIF and rnaIIIR. All constructions were sequence verified.

Plasmids constructed in E. coli were first introduced by electroporation into the nonrestricting S. aureus strain RN4220 prior to transfer to PC1072 and its derivatives. Electroporation conditions were as described previously (54).

Luciferase assay.

Precultures of all luxAB reporter strains were first grown in MHB containing the appropriate antibiotic and then diluted in 5 ml BHI, containing no antibiotic, to a final optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.01. Cultures were then grown with vigorous shaking (210 rpm) and aeration in an orbital shaker at 37°C. Aliquots were removed at different time points, representing exponential, post-exponential, and stationary growth phases determined by standard growth curves, normalized to an OD600 of 0.5 in a volume of 1 ml, and immediately measured for luciferase activity with a Glomax luminometer (Promega) by the addition of 20 μl 1% (vol/vol) decanal freshly diluted in absolute ethanol. Aliquots from the same time points were also taken in parallel and fixed and processed for total RNA extraction as described below. The statistical significance of strain-specific differences in light emission was evaluated by Student's paired t test, and data were considered significant when P values were <0.05.

Total bacterial RNA extraction and real-time qRT-PCR assays.

RNA extraction from culture aliquots fixed in liquid nitrogen was performed using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen), and the absence of contaminating DNA was verified by PCR. RNA levels were determined by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) using the one-step reverse transcriptase qPCR master mix kit (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium) as described previously (42). RNAIII transcript levels were monitored using probe sets RNAIII 367F, 436R, and 388T as described previously (55). The raw mRNA levels determined from the midpoint threshold cycle (CT) from the different strains were normalized to 16S rRNA levels, which were assayed in each round of qRT-PCR as internal controls. Data were collected for a minimum of three independent determinations.

Purification of SarA.

Recombinant 6×His-tagged SarA was purified using pET14b-sarA and purification by nickel affinity column chromatography as described previously (11). Aliquots were concentrated, adjusted to 50% glycerol, and frozen at −80°C. Protein concentrations were determined by using Bradford assay (Bio-Rad), using bovine serum albumin as a reference standard.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

Gel shift experiments were performed by incubating increasing amounts of SarA with various 5′-end-labeled tst promoter-containing probes prepared by PCR using primer sets described in Table 2. DNA probes were labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (Hartmann Analytic, FP-301; 111 TBq/mmol) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). Unincorporated radioactivity was removed by microcentrifugation on ProbeQuant G-50 spin columns according to the manufacturer's recommendations (GE Healthcare). SarA was incubated with the radiolabeled probes, approximately 10 fmol, for 7,000 Cerenkov counts per minute (cpm) for 15 min at 22°C in binding buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 2.5 mM MgCl2, 25 mM KCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) with the addition of 0.5 μg carrier sonicated calf thymus DNA, for a final volume of 30 μl. SarA for all reactions was diluted using binding buffer containing 100 μg/ml gelatin. Competition experiments were performed using as a negative control for SarA-DNA binding a 200-fold molar excess of a fragment (coordinates −364 to −255) from the ptst promoter region of pDA301 prepared using primers tst−364F and tst−255R. Control experiments showed that this fragment had no detectable affinity for SarA under any tested conditions. Specific competition used a 200-fold excess of unlabeled specific probe. All reactions were migrated in 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels using 1× TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate [pH 8.0], 0.2 mM EDTA) and then dried and autoradiographed (Amersham Hyperfilm).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′)a |

|---|---|

| tst−364F | TGGGGTACCCTCAAAGATAGATTGACCAGCGATG |

| tst−279F | TGGGGTACCTCCCTTACTGCAACACAGGACGTTT |

| tst−152F | TGGGGTACCTGCTATTTGTAACTTTAAAATGTTG |

| tst−44F | TGGGGTACCATGGTTAATTGATTCATTTAAA |

| tst−255R | TATCTGCAGAAACGTCCTGTGTTGCAGTAAGGGA |

| tst−45R | TATCTGCAGCTCTAAATTATTGTTTAAATATATA |

| tst+100R | TATCTGCAGCGATTGTCGCAAGCAACAAAGGGC |

| pHuA | TCCCCCGGGGCGGCCGCATTATATAGAGTATTATTTG |

| pHuB | CGCGGTACCGAGGTTTGATAATGATATGTTTATATC |

| rnaIIIF | GGGGTACCAGATCACAGAGATGTGATGGAAAAT |

| rnaIIIR | AACTGCAGAAGGCCGCGAGCTTGG |

| tst317R | GTGTTTAAGTCAACTTTTTCCCCTTTTGTAAAAGCAGGGC |

| tst706R | TTAATTAATTTCTGCTTCTATAGTTTTTATTT |

Underlined regions represent restriction enzyme sequences.

Dissociation constant determination.

Apparent dissociation constants (Kd) for SarA binding to Box1 alone or Box2 alone were derived from digital gel scans as follows. Autoradiograms were processed with Multi-Gauge 4.0 software (Fujifilm). The scanned peak heights for residual-free probe at each protein concentration were normalized as a percentage of free probe alone. Data were then fitted to a sigmoid curve using Origin 6.0 software, and apparent Kd were derived from computed concentrations at half maximal binding. Correlation coefficients for both curves exceeded 0.97. Protein concentrations used were significantly higher than radioactive probe concentrations so that the protein present in the bound fraction was negligible.

DNase I footprinting..

To label coding or noncoding strands, each primer, tst−279F or tst+100R, was first 5′-end-labeled using [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase. In a second step, a 381-bp fragment was obtained by PCR amplification using one labeled and one cold primer and ptst-pKS+ (pDA301) as a template. Probes were resolved on 1% agarose gels and excised and purified with a gel extraction kit (Qiagen). Binding reactions with increasing amounts of SarA and promoter probe were carried out for 15 min at room temperature with buffer and nonspecific carrier DNA conditions similar to those used for the gel shift assay. Then 1 μl (1 unit) of RQ1 DNase I (Promega) was added for 4 min. DNase I cleavage conditions were previously determined by pilot titrations. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 12.5 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.5% (wt/vol) SDS, and 0.4 mg/ml proteinase K. Reactions were extracted with phenol-chloroform, and ethanol was precipitated in the presence of 16 μg glycogen carrier. Pellets were washed with 70% ethanol, dried, and resuspended in formamide loading buffer (98% deionized formamide, 10 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 0.025% [wt/vol] xylene cyanol FF, and 0.025% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue). Samples were applied to 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gels with an adjacent sequencing ladder. The antisense sequence ladder was obtained by cycle-sequencing reaction (U.S. Biochemical) using the same primer sets as those used for PCR; the sense sequencing ladder was obtained from an unrelated sequence. Gels were dried and autoradiographed (Amersham Hyperfilm).

Transcription start site mapping by 5′RACE.

The transcription start site in the tstSaPI1 promoter was determined using RNA extracted from RN4282 and 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′RACE). Briefly, first-strand cDNA was generated using primers tst706R, SMARTer IIA oligonucleotide (SmarterRace, Clontech), and PrimeScript Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMLV) reverse transcriptase (Takara Biochemicals) according to the manufacturers' recommendations. Specific PCR amplification was then performed using a nested tst coding sequence primer (tst317R) and universal primer A mix (Clontech) and the Advantage 2 PCR kit (Clontech). The PCR product was resolved on a 1% agarose gel, excised and purified by a gel extraction kit (Qiagen), and then sequenced directly using tst317R primer. The transcription start site was unambiguously located at a single site in the sequenced PCR fragment population.

RESULTS

SarA binding to the tst promoter in vitro.

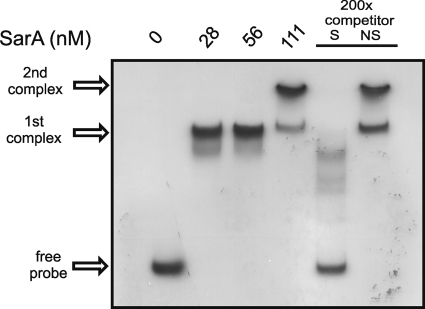

As a first step to elucidate whether purified SarA binds directly to the tst promoter region, we performed an electrophoretic mobility shift assay. As a probe, we used a PCR fragment containing the tst promoter region, encompassing nucleotides −152 to +100 (nucleotide coordinates throughout define +1 as the transcription start site determined in this study). The tst promoter probe amplified from SaPI1 in S. aureus strain N315P overlaps a previously described, partially active tst promoter at least 45 bp long (56). Various amounts of purified recombinant SarA containing an N-terminal 6×His affinity purification tag were incubated with γ-32P end-labeled probe under our standard reaction conditions in the presence of nonspecific carrier DNA (see Materials and Methods). The results are shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Gel shift showing binding of SarA on the tst promoter. Increasing amounts of recombinant SarA were incubated with 10 fmol of a radiolabeled 250-bp DNA probe containing the tst promoter. As a nonspecific competitor, 2 pmol of an unlabeled 100-bp DNA fragment, situated far upstream of tst, was added to SarA (at 111 nM). The same molar ratio was used for the addition of the 250-bp cold specific competitor. S, specific; NS, nonspecific.

We observed the formation of a strong protein-DNA complex in the smallest amounts of SarA tested (28 and 56 nM) and the apparent formation of a second protein-DNA complex in the largest amount of SarA tested (111 nM). To demonstrate the specificity of the SarA-tst promoter interaction, we performed a competition experiment with the largest amount of SarA (111 nM) in the presence of a 200-fold molar excess of unlabeled probe as a specific competitor or a 200-fold molar excess of a DNA fragment found to have no detectable affinity for SarA in pilot control experiments. The results in Fig. 1 showed that both SarA-promoter complexes detected were disrupted by a cold specific competitor but not by a nonspecific competitor, indicating that the observed SarA-tst promoter interaction was specific.

Localization of SarA binding sites by DNase I footprinting.

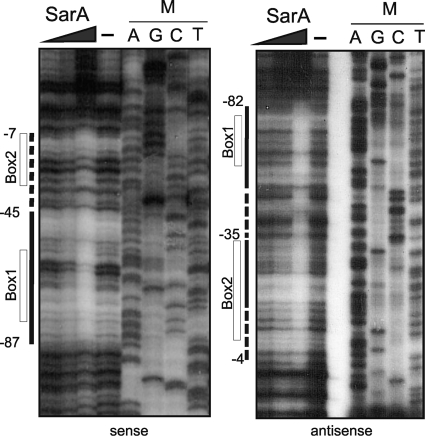

The appearance of two distinct SarA-tst promoter complexes suggested that the tst promoter fragment contained two SarA dimer binding sites or, alternatively, that SarA binding to one occupied site recruited additional SarA dimers or SarA binding induced topological DNA alteration that affected probe fragment mobility. In order to examine these possibilities, we next performed DNase I footprinting to define the region of SarA binding more precisely. The results are shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

DNase I footprint assay of SarA on the tst promoter. Increasing amounts of recombinant SarA, 62 nM, 111 nM, and 145 nM, were incubated with an asymmetrically radiolabeled 381-bp DNA probe containing the tst promoter. Nucleotide coordinates are defined relative to the transcriptional start site at +1. The continuous lines show strong protection by SarA, while the dashed lines show milder protection. The positions of predicted binding boxes are indicated. For the antisense panel, adjacent sequencing reactions were carried out using the same primers as those used for the probe. For the sense panel, the sequencing marker ladder corresponds to an unrelated sequence.

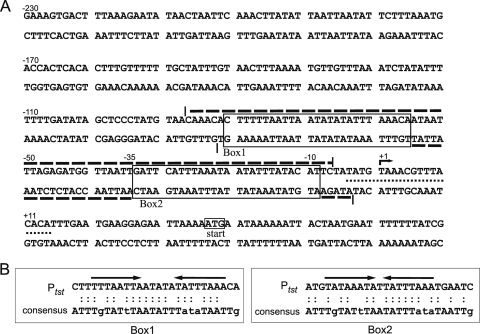

DNase I protection assay was performed using two 381-bp DNA probes 5′-end-labeled with γ-32P on either the top (sense) or bottom (antisense) strand. An extended region of protection of approximately 80 bp was observed on both strands from nucleotides −87 to −7 (top strand) and nucleotides −82 to −4 (bottom strand). However, a differentiated pattern appeared with a strong protection from nucleotides −87 to −45 compared to a weaker protection from nucleotides −44 to −4, this being especially obvious on the sense strand. Previously reported SarA binding to a single site within the sarA promoter revealed a zone of protection of approximately 30 bp (7), consistent with predictions for regions of DNase I protection upon binding of a winged helix protein (26). The zone of protection that we observed suggested the possibility of one strong SarA binding site and a second site with less affinity, consistent with the gel shift complex formation. The results are summarized schematically in Fig. 3 A.

FIG. 3.

(A) Nucleotide sequences and schematic diagram of the tst promoter region. The bracketed dashed lines indicate the limits of the SarA DNase I protected region. The dotted line refers to a previously proposed CRE site for CcpA-mediated catabolite repression (48). Box1 and Box2 correspond to consensus sites for SarA binding. The arrow marked with “+1” denotes the tst transcription start site determined by 5′RACE. The start codon of the TSST-1 open reading frame is indicated. (B) Comparison and nucleotide conservation between the published SarA consensus sequence (7) and both SarA binding sites proposed on this promoter. Both SarA sites contain incomplete 8-bp inverted repeats: Box1 TTTAATTA-TATTTAAA with a 5-bp spacer region and Box2 TATAAATA-TATTTAAA with a 1-bp spacer region.

The 80-bp sequence encompassing the region of DNase I protection was next examined by a computer search (using the “Needle” option of the EMBOSS pairwise alignment tool) for potential SarA binding sites by similarity with the published SarA consensus sequence (7). Two potential binding sites (Fig. 3B) were predicted: the first, named SarA Box1, was orientated with the same sense as the consensus SarA site on the top strand (from coordinates −81 to −56); a second site, named SarA Box2, was inverted relative to the SarA consensus on the bottom strand (coordinates −34 to −9). The Box1 binding site displays an 18/26-bp identity to the consensus SarA site, while Box2 displays a 17/26-bp identity. Additional comparison between only the most conserved nucleotides (uppercase) revealed a 75% sequence identity to the SarA consensus for both SarA boxes.

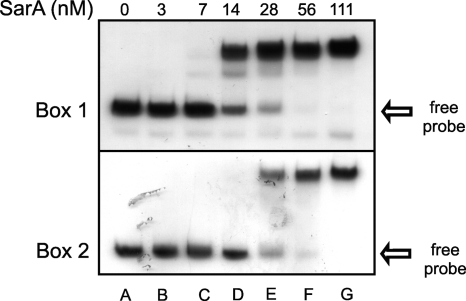

Determination of the relative binding affinity of the two SarA boxes.

To determine whether the distal Box1 alone or proximal Box2 alone were sufficient for SarA binding and to concomitantly compare the relative affinity of SarA to each binding site, we performed gel shift assays on tst promoter segments encompassing either Box1 alone (spanning nucleotides −152 to −45) or Box2 alone (−44 to +100). The results are shown in Fig. 4. Identical titrations of SarA were used in both experiments in order to allow comparison. Our results showed that the Box1 promoter region alone bound SarA. The SarA concentration which permitted half of the input probe to shift in this assay resulted in a computed apparent Kd for SarA Box1 of 15 nM. In contrast, SarA Box2 had a computed apparent Kd of 27 nM. From these experiments, we conclude that SarA affinity in vitro is approximately 2-fold higher for Box1 than for Box2. Taken together, these data show that in vitro SarA can bind two different sites on the tst promoter, with a higher affinity to Box1 than to Box2. The two sites are inverted, with one on the sense strand and another on the nonsense strand, and separated by approximately two helical turns. Interestingly, in both strands, the strong protected area overlapped Box1, while Box2 mapped into a milder protection area; this correlates with the higher similarity of Box1 to the consensus sequence.

FIG. 4.

Gel shift experiments showing binding of SarA with segments of the tst promoter encompassing either binding Box1 (upper) or binding Box2 (bottom). Increasing amounts of recombinant SarA were incubated with 10 fmol of a radiolabeled DNA probe.

Genetic analysis of a ptst-luxAB transcriptional reporter fusion in strains carrying ΔsarA, Δhld-RNAIII, or both mutations.

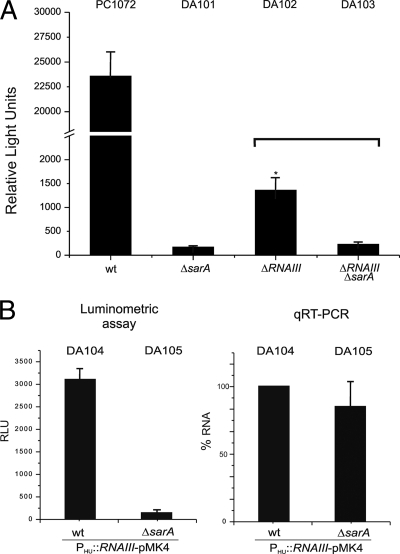

Since we identified two SarA binding sites on the tst promoter, we hypothesized that SarA could exert a direct regulation of this promoter independently of SarA-driven RNAIII. Indeed, this has been a controversial point which is unresolved (32). If this hypothesis were true, we would expect that the disruption of sarA would have a more pronounced effect on the ptst-luxAB reporter than disruption of hld-RNAIII alone. In order to address the question, we constructed various derivatives of strain PC1072 carrying a ptst-luxAB reporter stably integrated in the S. aureus chromosome at the geh locus (4). Strains DA101, DA102, and DA103 carried ΔsarA::kan, Δhld-RNAIII::cam, or both mutations, respectively. Under aerobic conditions, we measured luciferase activity in PC1072 in exponential, late post-exponential, and stationary phases (at 2.5 h, 6 h, and 14 h of growth, respectively). As previously reported (4), the maximum induction of luciferase under these experimental conditions was recorded in stationary phase between 13 to 15 h of growth (data not shown). Importantly, strain PC1072 shows an agr+ RNAIII+ phenotype on sheep blood agar plates, indicating that the agr quorum-sensing system was functional in this strain background. The results of luciferase assays conducted upon entry to stationary growth phase for PC1072 and its three mutant derivatives are depicted in Fig. 5 A.

FIG. 5.

(A) Luciferase reporter assay for the tst promoter. The histogram shows measured luminometric activity of different strains in stationary growth phase. All cultures were first normalized to an OD600 of 0.5 and then assayed. Bars show ± standard deviations. The asterisk indicates significant difference between strains DA102 and DA103 calculated by Student's two-tailed t test (P < 0.05). (B) Luciferase reporter assay for the tst promoter in the indicated strains harboring the plasmid pDA201, which drives hld-RNAIII transcript expression by pHU independent of sarA and agr regulation (left). Quantitative qRT-PCR measurements of RNAIII expression in both strains, setting DA104 as 100% (right). Bars show ± standard deviations. All data are compiled from three independent experiments. RLU, relative light units.

Strain DA101 carrying ΔsarA::kan showed nearly complete abrogation of ptst-luxAB reporter induction compared to PC1072 parental strain (from 23,600 to 170 relative light units). In contrast, DA102 carrying the Δhld-RNAIII::cam disruption showed markedly reduced (approximately 94% of PC1072 control, 1,400 relative light units) but not complete loss of luciferase reporter induction under these conditions. The double mutation in DA103 carrying both ΔsarA and Δhld-RNAIII disruptions showed a loss of luciferase reporter induction comparable to and statistically indistinguishable from DA101 (200 relative light units). Importantly, we measured a statistically significant (P < 0.05) reduction in luciferase reporter activity when comparing DA102 and DA103, indicating that disruption of sarA could account for the additional loss of luciferase reporter induction in a strain background where hld-RNAIII had already been eliminated. Collectively, these findings strongly suggest that SarA does control the tst promoter both directly and in an agr-dependent manner.

To further explore this point, we next constructed plasmid pDA201 harboring cloned hld-RNAIII under the control of the pHU promoter that was not subject to regulation by the agr quorum-sensing system (11, 27). We reasoned that the introduction of this plasmid, pDA101, into both PC1072 and DA101 (yielding strains DA104 and DA105, respectively) would permit us to drive and monitor RNAIII level equilibration in the presence or absence of sarA by qRT-PCR and also concomitantly measure the ptst-driven luciferase reporter in the same strains. Specifically, we reasoned that if RNAIII levels were comparable between the two strains, but if measured luciferase activity were strongly reduced, then we could conclude that SarA most likely also exerted a direct influence upon the tst promoter independently of agr and SarA-driven hld-RNAIII production in post-exponential phase. Indeed, this was observed, and the results are shown in Fig. 5B. qRT-PCR analysis showed that RNAIII transcript levels in DA104 and DA105 were comparable (setting DA104 as 100%, DA105 RNAIII levels were measured in three independent experiments as 84.8% ± 20.8% [mean ± SD]). Despite the essentially equivalent RNAIII levels, loss of sarA in DA105 was associated with an approximately 2-fold log10 reduction in ptst-luxAB reporter activity. Collectively, we conclude from these results that SarA can modulate tst promoter activation independently of RNAIII levels under these experimental conditions.

DISCUSSION

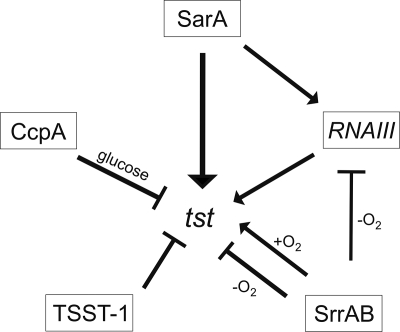

Our study has revealed two SarA binding sites on the tst promoter upstream of its transcriptional start site, which we have mapped precisely by 5′RACE. Genetic analysis has further revealed that SarA exerts dual control over the tst promoter by both agr-dependent and agr-independent pathways. Disruption of RNAIII showed reduced but not complete abolition of a luciferase reporter driven by the tst promoter, whereas disruption of both sarA and RNAIII reduced luciferase reporter measurements to background control levels. The residual sarA-dependent transcriptional regulation of tst seen in the absence of RNAIII coupled with the detection of SarA binding to the tst promoter strongly supports the notion that SarA exerts significant direct positive regulation of the tst promoter. Figure 6 summarizes some of the pathways thought to comprise tst promoter regulation, including both SarA routes.

FIG. 6.

Scheme of tst transcriptional regulation. Positive regulation is represented by the arrows, negative regulation by the bars.

The distal Box1 SarA binding site positioned between 20 and 45 nucleotides upstream of the −35 and −10 box suggests a role as an activator site. In contrast, the physiological relevance of Box2 is less clear. Box2 overlaps canonical promoter elements and likely disrupts RNA polymerase accessibility. Thus, although we detect SarA binding to Box2 in vitro, the question of the occupancy of this site in vivo remains open. Since SarA has an apparent higher affinity for Box1 than for Box2, it is conceivable that low SarA levels are sufficient to occupy the first site and that the second site gets occupied only at higher SarA concentrations. Thus, we could speculate that this site is a repressor site under some circumstances compared to a strong Box1 activator site.

Upon sequence inspection, Box2 is inverted with respect to Box1 and separated by approximately two helical turns. Their close proximity and orientation on the same helical face suggest that SarA binding to one site could conceivably favor SarA binding to the second site. The configuration of two inverted SarA binding sites, but with various intervening helical spacings, is also seen on the sarA, agr, ica, and rot promoters (7, 30, 39) (D. Andrey, unpublished observations). These findings suggest that detailed studies of promoter architecture, intersite spacing, and transcription start site mapping will reveal additional clues to SarA-mediated transcriptional regulation. SarA could well exert both positive and negative control over promoters in vivo depending upon multiple complex interactions, the constraints imposed by DNA configuration, and the disposition of additional promoter binding proteins.

The SarA consensus site used in this study has been compiled from an alignment of six promoters to which SarA binds (7, 11). The consensus site is remarkably AT rich, and the most important DNA bases required for specific recognition remain poorly understood. SarA DNA binding domains encompass an HTH domain and a winged domain with affinity for the major groove and minor groove of DNA, respectively. Based upon structural studies, it has been proposed that SarA binding as a dimer shortens the DNA helix and causes DNA bending (25, 26, 47). Interestingly, Rohs and coworkers (43) recently reported the importance of DNA shape in protein-DNA recognition and show that AT-rich sequences, specifically A tracts (as short as three adenines), tend to narrow the minor groove of DNA. Their results suggest that the width of the minor groove below 5 Å is read as a second type of DNA recognition pattern. They propose that the arginine-mediated narrow minor-groove recognition is complementary to classical sequence-based recognition typical of major-groove DNA binding. From this perspective, it is noteworthy that SarA mutant proteins R84A and R90A, situated in the β2 sheet and the loop between sheets β2 and β3 of the winged domain, respectively, both totally abolished SarA binding in vitro to the spa promoter (26). It is thus tempting to speculate that SarA recognizes certain binding sites by a dual mechanism relying on both base sequence and local DNA structure. Such a dual binding site recognition mechanism might explain the wide variation in reported SarA binding sites and an extended consensus motif as large as 26 bases.

The experimental conditions used in our study excluded known negative autoregulation of the tst promoter imposed by TSST-1 itself (56), since the reporter strain did not encode a complete copy of tst. Since maximal induction of the luciferase reporter was observed in post-exponential phase, we believe that catabolite repression is also most likely inoperative in our experimental conditions as a result of glucose depletion in the growth medium. Interestingly, the consensus CRE site identified in the tst promoter (48), which is the cis-acting element for catabolite repression imposed by the binding of the CcpA-Hpr complex, maps immediately adjacent to the potential SarA Box2 and precisely overlaps the transcription start site. This finding suggests that catabolite repression regulates the tst expression through promoter occlusion by preventing RNA polymerase binding or by preventing open promoter complex formation. It is also possible that CcpA-Hpr complex binding to the CRE site is modulated by the adjacent binding of SarA. No direct binding of the CcpA-Hpr complex has been reported to date to address these possibilities.

The agr locus is encoded by a typical two-component histidine kinase sensor effector (termed TCS) that responds to population density by responding to diffusible autoinducing peptide (AIP) quorum-sensing signals also encoded within the locus. The only known AgrA response regulator DNA binding target to date is the agrP3 promoter, which controls expression of the hld-RNAIII transcript. A possible exception is the direct binding of AgrA to phenol-soluble modulin (PSM) cytolysin genes (38). The issue of instability of the agr quorum-sensing system in laboratory strains and possibly also in clinical isolates has been noted (49, 53). Thus, even in cases where agr is mutated and loss of RNAIII expression ensues, our findings suggest the potential for residual tst expression mediated by SarA. Indeed, Chan and Foster reported that strain PC1072, harboring agr::Tn551, could be spiked with EDTA or EGTA to induce additional reporter induction, arguing for additional uncharacterized modes of tst promoter regulation independent of agr (57). Surface charge is now known to influence the response of diverse TCS systems and may provide clues to the mechanism underlying the effects of chelators (17).

How many regulatory circuits and environmental stimuli collectively influence the tst promoter is unknown. An additional candidate is SrrAB, another TCS system, thought to control S. aureus metabolic responses to changes in oxygen partial pressure (36). SrrA has been reported to bind to both the agrP3 promoter region and to tst, thus permitting it to potentially modulate TSST-1 expression both directly and indirectly through its regulation of RNAIII expression (37). How SrrA regulates tst is unknown, but it is worth noting that mutation of SrrA in a clinical S. aureus strain resulted in an N-terminal-truncated SrrA and was correlated with increased TSST-1 expression (35). In addition, mutation of SrrAB has been correlated with increased RNAIII levels (58).

The PC1072 reporter strain used in our study is an 8325-4 derivative which has a defect in rsbU resulting in reduced activity of the alterative sigma factor σB. Loss of σB is also associated with increased RNAIII production (2), which in part explains the high level of luciferase reporter activity in this experimental system (4).

Our present work also suggests that those factors which influence SarA expression or activity should also concomitantly influence tst expression. SarA is known to comprise a large family of similar global regulators; SarA is negatively regulated by SarR (28) and also regulates itself (7), and one of its three transcripts, sarP3, is controlled by σB (29). SarA binding activity also appears to be subject to redox conditions. How S. aureus precisely senses oxygen is unknown but may involve contributions from SrrAB, NreBC, Spx, and SarA itself (5, 34, 45, 58). Indeed, it was recently shown that cysteine 9 of SarA governs binding to the agr promoter in vitro in response to redox agents (15). Mutation of C9 also affects binding to the spa promoter (26).

Overall, this complex regulatory network sheds light on how layers of regulation are imposed upon TSST-1 expression. Since tst is prevalent in S. aureus strains by virtue of its location on a mobile pathogenicity island, yet TSST-1-mediated toxic shock is rarely seen, tight regulation of tst transcription and toxin secretion must ultimately occur. Identifying what combinatorial arrangements of positive and negative regulators occur on the tst promoter is being vigorously investigated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a research grant from the Swiss National Foundation (3100A0-120428) (to W.L.K.), an MD-PhD doctoral training grant from F. Hoffmann-La Roche (to D.O.A.), and NIH grant RO1AI37142 (to A.L.C.).

We thank Simon J. Foster (University of Sheffield) and Stefan Arvidson (Karolinska Institute) for generous gifts of strains and plasmids, Dominique Garcin (University of Geneva) for access and advice with the GloMax Promega luminometer, Colette Rossier of the University of Geneva Medical School core sequencing facility, and David Andrey for assistance with enhanced digital graphics. We thank members of the laboratory, in particular Régis Villet and Elena Galbusera, for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 September 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ballal, A., and A. C. Manna. 2010. Control of thioredoxin reductase gene (trxB) transcription by SarA in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 192:336-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bischoff, M., J. M. Entenza, and P. Giachino. 2001. Influence of a functional sigB operon on the global regulators sar and agr in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 183:5171-5179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blevins, J. S., A. F. Gillaspy, T. M. Rechtin, B. K. Hurlburt, and M. S. Smeltzer. 1999. The staphylococcal accessory regulator (sar) represses transcription of the Staphylococcus aureus collagen adhesin gene (cna) in an agr-independent manner. Mol. Microbiol. 33:317-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan, P. F., and S. J. Foster. 1998. The role of environmental factors in the regulation of virulence-determinant expression in Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4. Microbiology 144(Pt. 9):2469-2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan, P. F., and S. J. Foster. 1998. Role of SarA in virulence determinant production and environmental signal transduction in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 180:6232-6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung, A. L., A. S. Bayer, G. Zhang, H. Gresham, and Y. Q. Xiong. 2004. Regulation of virulence determinants in vitro and in vivo in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 40:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung, A. L., K. Nishina, and A. C. Manna. 2008. SarA of Staphylococcus aureus binds to the sarA promoter to regulate gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 190:2239-2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheung, A. L., K. A. Nishina, M. P. Trotonda, and S. Tamber. 2008. The SarA protein family of Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 40:355-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung, A. L., K. Schmidt, B. Bateman, and A. C. Manna. 2001. SarS, a SarA homolog repressible by agr, is an activator of protein A synthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 69:2448-2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chien, Y., and A. L. Cheung. 1998. Molecular interactions between two global regulators, sar and agr, in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 273:2645-2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chien, Y., A. C. Manna, S. J. Projan, and A. L. Cheung. 1999. SarA, a global regulator of virulence determinants in Staphylococcus aureus, binds to a conserved motif essential for sar-dependent gene regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:37169-37176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeLeo, F. R., and H. F. Chambers. 2009. Reemergence of antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the genomics era. J. Clin. Invest. 119:2464-2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunman, P. M., E. Murphy, S. Haney, D. Palacios, G. Tucker-Kellogg, S. Wu, E. L. Brown, R. J. Zagursky, D. Shlaes, and S. J. Projan. 2001. Transcription profiling-based identification of Staphylococcus aureus genes regulated by the agr and/or sarA loci. J. Bacteriol. 183:7341-7353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster, T. J. 2005. Immune evasion by staphylococci. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:948-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujimoto, D. F., R. H. Higginbotham, K. M. Sterba, S. J. Maleki, A. M. Segall, M. S. Smeltzer, and B. K. Hurlburt. 2009. Staphylococcus aureus SarA is a regulatory protein responsive to redox and pH that can support bacteriophage lambda integrase-mediated excision/recombination. Mol. Microbiol. 74:1445-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao, R., and A. M. Stock. 2009. Biological insights from structures of two-component proteins. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63:133-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyyrylainen, H. L., M. Pietiainen, T. Lunden, A. Ekman, M. Gardemeister, S. Murtomaki-Repo, H. Antelmann, M. Hecker, L. Valmu, M. Sarvas, and V. P. Kontinen. 2007. The density of negative charge in the cell wall influences two-component signal transduction in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 153:2126-2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janzon, L., and S. Arvidson. 1990. The role of the delta-lysin gene (hld) in the regulation of virulence genes by the accessory gene regulator (agr) in Staphylococcus aureus. EMBO J. 9:1391-1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kass, E. H. 1989. Magnesium and the pathogenesis of toxic shock syndrome. Rev. Infect. Dis. 11(Suppl. 1):S167-S175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katayama, Y., H. Murakami-Kuroda, L. Cui, and K. Hiramatsu. 2009. Selection of heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus by imipenem. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3190-3196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreiswirth, B. N., S. Lofdahl, M. J. Betley, M. O'Reilly, P. M. Schlievert, M. S. Bergdoll, and R. P. Novick. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305:709-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreiswirth, B. N., M. O'Reilly, and R. P. Novick. 1984. Genetic characterization and cloning of the toxic shock syndrome exotoxin. Surv. Synth. Pathol. Res. 3:73-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lappin, E., and A. J. Ferguson. 2009. Gram-positive toxic shock syndromes. Lancet Infect. Dis. 9:281-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindsay, J. A., A. Ruzin, H. F. Ross, N. Kurepina, and R. P. Novick. 1998. The gene for toxic shock toxin is carried by a family of mobile pathogenicity islands in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 29:527-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu, Y., A. Manna, R. Li, W. E. Martin, R. C. Murphy, A. L. Cheung, and G. Zhang. 2001. Crystal structure of the SarR protein from Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:6877-6882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu, Y., A. C. Manna, C. H. Pan, I. A. Kriksunov, D. J. Thiel, A. L. Cheung, and G. Zhang. 2006. Structural and function analyses of the global regulatory protein SarA from Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:2392-2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luong, T. T., P. M. Dunman, E. Murphy, S. J. Projan, and C. Y. Lee. 2006. Transcription profiling of the mgrA regulon in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 188:1899-1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manna, A., and A. L. Cheung. 2001. Characterization of sarR, a modulator of sar expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 69:885-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manna, A. C., M. G. Bayer, and A. L. Cheung. 1998. Transcriptional analysis of different promoters in the sar locus in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 180:3828-3836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manna, A. C., and B. Ray. 2007. Regulation and characterization of rot transcription in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology 153:1538-1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCormick, J. K., J. M. Yarwood, and P. M. Schlievert. 2001. Toxic shock syndrome and bacterial superantigens: an update. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:77-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novick, R. P. 2003. Autoinduction and signal transduction in the regulation of staphylococcal virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1429-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Novick, R. P. 2003. Mobile genetic elements and bacterial toxinoses: the superantigen-encoding pathogenicity islands of Staphylococcus aureus. Plasmid 49:93-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pamp, S. J., D. Frees, S. Engelmann, M. Hecker, and H. Ingmer. 2006. Spx is a global effector impacting stress tolerance and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 188:4861-4870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pragman, A. A., L. Herron-Olson, L. C. Case, S. M. Vetter, E. E. Henke, V. Kapur, and P. M. Schlievert. 2007. Sequence analysis of the Staphylococcus aureus srrAB loci reveals that truncation of srrA affects growth and virulence factor expression. J. Bacteriol. 189:7515-7519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pragman, A. A., Y. Ji, and P. M. Schlievert. 2007. Repression of Staphylococcus aureus SrrAB using inducible antisense srrA alters growth and virulence factor transcript levels. Biochemistry 46:314-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pragman, A. A., J. M. Yarwood, T. J. Tripp, and P. M. Schlievert. 2004. Characterization of virulence factor regulation by SrrAB, a two-component system in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 186:2430-2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Queck, S. Y., M. Jameson-Lee, A. E. Villaruz, T. H. Bach, B. A. Khan, D. E. Sturdevant, S. M. Ricklefs, M. Li, and M. Otto. 2008. RNAIII-independent target gene control by the agr quorum-sensing system: insight into the evolution of virulence regulation in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Cell 32:150-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rechtin, T. M., A. F. Gillaspy, M. A. Schumacher, R. G. Brennan, M. S. Smeltzer, and B. K. Hurlburt. 1999. Characterization of the SarA virulence gene regulator of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 33:307-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Recsei, P., B. Kreiswirth, M. O'Reilly, P. Schlievert, A. Gruss, and R. P. Novick. 1986. Regulation of exoprotein gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus by agar. Mol. Gen. Genet. 202:58-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Renzoni, A., C. Barras, P. Francois, Y. Charbonnier, E. Huggler, C. Garzoni, W. L. Kelley, P. Majcherczyk, J. Schrenzel, D. P. Lew, and P. Vaudaux. 2006. Transcriptomic and functional analysis of an autolysis-deficient, teicoplanin-resistant derivative of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3048-3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Renzoni, A., P. Francois, D. Li, W. L. Kelley, D. P. Lew, P. Vaudaux, and J. Schrenzel. 2004. Modulation of fibronectin adhesins and other virulence factors in a teicoplanin-resistant derivative of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2958-2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rohs, R., S. M. West, A. Sosinsky, P. Liu, R. S. Mann, and B. Honig. 2009. The role of DNA shape in protein-DNA recognition. Nature 461:1248-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rooijakkers, S. H., K. P. van Kessel, and J. A. van Strijp. 2005. Staphylococcal innate immune evasion. Trends Microbiol. 13:596-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlag, S., S. Fuchs, C. Nerz, R. Gaupp, S. Engelmann, M. Liebeke, M. Lalk, M. Hecker, and F. Gotz. 2008. Characterization of the oxygen-responsive NreABC regulon of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 190:7847-7858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schlievert, P. M., L. C. Case, K. A. Nemeth, C. C. Davis, Y. Sun, W. Qin, F. Wang, A. J. Brosnahan, J. A. Mleziva, M. L. Peterson, and B. E. Jones. 2007. Alpha and beta chains of hemoglobin inhibit production of Staphylococcus aureus exotoxins. Biochemistry 46:14349-14358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schumacher, M. A., B. K. Hurlburt, and R. G. Brennan. 2001. Crystal structures of SarA, a pleiotropic regulator of virulence genes in S. aureus. Nature 409:215-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seidl, K., M. Bischoff, and B. Berger-Bachi. 2008. CcpA mediates the catabolite repression of tst in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 76:5093-5099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Somerville, G. A., S. B. Beres, J. R. Fitzgerald, F. R. DeLeo, R. L. Cole, J. S. Hoff, and J. M. Musser. 2002. In vitro serial passage of Staphylococcus aureus: changes in physiology, virulence factor production, and agr nucleotide sequence. J. Bacteriol. 184:1430-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Subedi, A., C. Ubeda, R. P. Adhikari, J. R. Penades, and R. P. Novick. 2007. Sequence analysis reveals genetic exchanges and intraspecific spread of SaPI2, a pathogenicity island involved in menstrual toxic shock. Microbiology 153:3235-3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sullivan, M. A., R. E. Yasbin, and F. E. Young. 1984. New shuttle vectors for Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli which allow rapid detection of inserted fragments. Gene 29:21-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tormo, M. A., M. Marti, J. Valle, A. C. Manna, A. L. Cheung, I. Lasa, and J. R. Penades. 2005. SarA is an essential positive regulator of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm development. J. Bacteriol. 187:2348-2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Traber, K., and R. Novick. 2006. A slipped-mispairing mutation in AgrA of laboratory strains and clinical isolates results in delayed activation of agr and failure to translate delta- and alpha-haemolysins. Mol. Microbiol. 59:1519-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tu Quoc, P. H., P. Genevaux, M. Pajunen, H. Savilahti, C. Georgopoulos, J. Schrenzel, and W. L. Kelley. 2007. Isolation and characterization of biofilm formation-defective mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 75:1079-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vaudaux, P., P. Francois, C. Bisognano, W. L. Kelley, D. P. Lew, J. Schrenzel, R. A. Proctor, P. J. McNamara, G. Peters, and C. Von Eiff. 2002. Increased expression of clumping factor and fibronectin-binding proteins by hemB mutants of Staphylococcus aureus expressing small colony variant phenotypes. Infect. Immun. 70:5428-5437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vojtov, N., H. F. Ross, and R. P. Novick. 2002. Global repression of exotoxin synthesis by staphylococcal superantigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:10102-10107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yarwood, J. M., J. K. McCormick, M. L. Paustian, V. Kapur, and P. M. Schlievert. 2002. Repression of the Staphylococcus aureus accessory gene regulator in serum and in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 184:1095-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yarwood, J. M., J. K. McCormick, and P. M. Schlievert. 2001. Identification of a novel two-component regulatory system that acts in global regulation of virulence factors of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 183:1113-1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yarwood, J. M., and P. M. Schlievert. 2000. Oxygen and carbon dioxide regulation of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 production by Staphylococcus aureus MN8. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1797-1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]