Abstract

Protein loops are often involved in important biological functions such as molecular recognition, signal transduction, or enzymatic action. The three dimensional structures of loops can provide essential information for understanding molecular mechanisms behind protein functions. In this paper, we develop a novel method for protein loop modeling, where the loop conformations are generated by fragment assembly and analytical loop closure. The fragment assembly method reduces the conformational space drastically, and the analytical loop closure method finds the geometrically consistent loop conformations efficiently. We also derive an analytic formula for the gradient of any analytical function of dihedral angles in the space of closed loops. The gradient can be used to optimize various restraints derived from experiments or databases, for example restraints for preferential interactions between specific residues or for preferred backbone angles. We demonstrate that the current loop modeling method outperforms previous methods that employ residue-based torsion angle maps or different loop closure strategies when tested on two sets of loop targets of lengths ranging from 4 to 12.

Keywords: Loop modeling, Protein structure prediction, Fragment assembly method, Analytical loop closure, Loop ensemble

I. INTRODUCTION

Prediction of the native structure of a protein from its amino acid sequence is one of the most important problems in protein science. However, modeling the native structure based solely on physico-chemical energy functions remains an unsolved problem [1–3]. Therefore, bioinformatics approaches that utilize information extracted from the database of known structures are widely used in practice. When experimental structures of homologous sequences are available, these structures can be used as templates [4, 5]. However, homologous proteins still have gaps or insertions in sequences, referred to as loops, whose structures are not conserved during evolution. Since the templates give no structural information on these regions, the loops have to be modeled ab initio.

Although the length of a loop region is generally much shorter than that of the whole protein chain, modeling a loop poses a challenge not present in the global protein structure prediction, in that the modeled loop structure has to be geometrically consistent with the rest of the protein structure. The condition of such consistency imposes constraints on the possible values of the loop dihedral angles, called the loop closure constraint, when the bond lengths and bond angles are kept close to canonical values. In many loop modeling methods developed so far, conformations are generated without explicit loop closure constraint. The gap in the chain is reduced afterwards either by screening out conformations with large gaps or by minimizing an energy term penalizing the gap [6–13].

On the other hand, conformations satisfying the loop closure constraint can be generated by using analytical loop closure [14–24]. Among these methods, the polynomial formulation developed in Ref. [20, 21] has the combined advantage of simplicity and generality, and can be applied to closing loops by rotation of torsion angles of non-consecutive residues. Iterative loop closure methods have also been developed [25–28]. An analytical loop closure approach is natural and efficient in that minimization of an arbitrary gap penalty is unnecessary since loops are restricted to be closed in a purely geometric way, and there is no small remaining chain break that needs to be ignored or reduced afterwards. In a sampling test on thirty loop targets of lengths ranging from four to twelve residues and an optimization test on an eight-residue loop, it was shown that loop sampling can be performed much more efficiently when analytical loop closure is employed [20]. Analytical loop closure was also combined with the Rosetta energy function [24] and was shown to predict loop structures more accurately than the previous Rosetta method that employs an iterative loop closure method [29].

The loop conformational space can be further reduced by using fragment assembly. Fragment assembly methods have been applied widely and successfully to protein structure prediction when structural templates are not available [13, 30–45]. In a fragment assembly method, local structures are limited to those of short fragments collected from a structure database, and the global structure is modeled by searching for the lowest free energy state among the states with such local structures.

In this work, we combine the two approaches, analytical loop closure and fragment assembly, for efficient protein loop sampling. Since an initial loop conformation generated by fragment assembly alone does not close the loop in general, backbone torsion angles are perturbed so that the analytical loop closure equation is satisfied. A torsional energy function can be minimized at the same time to confine the angle changes that accompany loop closure within a desired range. In order to perform this task efficiently, we develop an analytic formula for the gradient of a function of backbone dihedral angles in the space of closed loops.

Prediction results on eight short protein loops using a preliminary version of the current method was reported in Ref. [30], where a Monte Carlo search was used to find conformations minimizing a deviation from the original fragment angles. In this work, by developing a general formula for the analytic gradient of a function of dihedral angles that satisfy the loop closure constraint, such minimization can be performed much more efficiently.

We demonstrate the performance of our method by loop reconstruction tests on the 30 loops proposed by Canutescu and Dunbrack [27] and the 317 loops developed by Fiser et al. [46]. We found that the sampling efficiency is significantly improved compared to four different previous methods [7, 20, 27, 47]. By combining our sampling method with a statistical potential DFIRE [48, 49] the loop prediction accuracy could also be improved.

II. METHODS

A. Collection of Fragments and Structure Database

For each residue of a target loop, a seven-residue window centered on the residue is considered. For each window, two hundred fragment structures of length seven with similar sequence features are collected from a non-redundant structure database, as described below. The structure database was constructed by clustering an ASTRAL SCOP (version 1.63) set so that no two proteins in the database have more than 25 % sequence identity with each other [50–52]. The resulting set consists of 4362 non-redundant protein chains and total of 905684 residues. In order to perform a fair benchmark test, we did not use fragments obtained from proteins homologous to the target proteins in this work. To elaborate, we removed the proteins with E-value less than 0.01 after a BLAST search [53] with the whole sequence containing the target loop.

The sequence features to be compared for fragment selection are the sequence profiles obtained from a PSI-BLAST search. A sequence profile is a set of position-dependent mutation probabilities of the protein residues to other amino acids, obtained from local alignment of a given sequence with related sequences in a sequence database. The PSI-BLAST profile contains evolutionary information that cannot be obtained directly from the raw sequence, and it has been widely used for local structure prediction [51, 52, 54] as well as for global structure prediction by fragment assembly methods [13, 30, 32–45].

Since we consider windows of size seven, the sequence features for each window form a matrix of size 7 × 20. The distance between two sets of sequence features A and B is defined as

| (1) |

where is a component of the sequence feature set A, and wi is a weight parameter. Since the end-regions of a fragment is often cut off during fragment assembly, as explained in the next subsection, the structure of the central region is more frequently used. We thus place higher weight on the central region by using the formula

| (2) |

Two hundred fragments of seven residues that have the shortest distances from the target loop sequence for each window are then collected for fragment assembly. It must be noted that for the terminal residues of the loop, the windows contain residues in the framework region. Therefore, the sequence features used for collecting the fragments contain information on the framework region as well.

B. Fragment Assembly for the Loop Region

The fragments obtained as above are assembled to construct loop conformations. Conformations are generated by sequentially adding randomly chosen fragments starting from the N-terminal region of the loop. A new fragment is joined to the growing loop conformation only if they share at least one residue with close dihedral angles. Two sets of dihedral angles (ϕ1, ψ1) and (ϕ2, ψ2) are considered to be close if

| (3) |

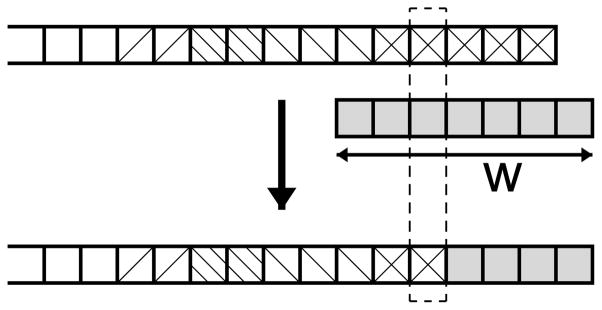

The comparison of dihedral angles is made between the first w − 1 residues of the new fragment and the last w − 1 residues of the current partial loop conformation, where w is the the fragment length. As mentioned above, w = 7 is used in this work. If we find a residue that satisfies the condition Eq. (3), the new fragment is added starting from the next residue position, and the length of the partial loop is increased by 1. This assembly procedure is illustrated in Fig. 1. When there is no position satisfying the condition Eq. (3), another fragment is selected from the fragment set. If no fragment can be added at the current step, the assembly procedure goes back to the previous loop conformation with one less residue, and another fragment is chosen randomly. For a loop of length L, conformations of length L + 8 are generated to utilize information in the fragments including framework residues. The structures outside the loop region are discarded in the subsequent analysis.

FIG. 1.

Illustration of the fragment assembly process. A fragment of length w = 7 (middle) is joined to the growing loop conformation (top), resulting in a loop conformation with one more residue (bottom). The fragment is joined starting from the position next to the residue with close dihedral angles between the fragment and the growing loop (indicated with a dotted box). The blocks of different shadings represent contributions from distinct fragments. Their average size is 1.9, as presented in the text.

Since the joining of new fragments usually occurs in the middle of the fragments, only parts of the 7-residue-long fragments are used in the assembly, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The average length of the actually inserted part of fragments by the current method is 1.9 for the conformations generated for the Fiser loop set [46], as shown in Table I. One can see that the sizes of the inserted fragments do not depend much on the target loop length.

TABLE I.

The average length of the inserted part of fragments in loop construction of the Fiser loop set for each target loop length

| Loop length | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insertion length | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.9 |

By joining the fragments only at close values of dihedral angles, we concentrate on more realistic structures that resemble those found in the structure database even near fragment junctions. In this way, the conformational search space is reduced significantly [39–45] compared to other fragment assembly methods that do not require such condition. Due to this fact, a random sampling method tested in this study performs very well for the sizes of the loops considered here (up to 12 residues), as presented in the Results and Discussion section. A set of 5000 conformations was generated for each loop target in the Canutescu and Dunbrack set to compare with several previous methods. Initial 4000 conformations were generated for the test on the Fiser set [46], out of which a final set of 1000 conformations were selected after a screening procedure to compare with the RAPPER method [7]. There is no difficulty in increasing the number of sampled conformations because the whole procedure is very efficient, and the method may also be combined with more extensive search methods, especially for loops longer than those considered here.

C. Analytical Loop Closure and Analytical Gradient

Conformations for a protein loop generated by the fragment assembly method alone do not satisfy the loop closure constraint in general. Therefore, the backbone torsion angles of the loop must be rotated so that the loop structures correctly fit into the rest of the protein structure. Since the minimum number of backbone torsion angles that has to be rotated for loop closure is six, we first perform an initial loop closure by randomly selecting three residues and computing their six backbone dihedral angles (three ϕ and three ψ angles) by solving the analytical loop closure equation [20, 21]. Among N loop dihedral angles, the N − 6 unperturbed ones are from the database fragments. However, the six dihedral angles perturbed for the closure may deviate from the initial fragment angles significantly or may even fall into Ramachandran-disallowed regions [55] in some cases, depending on the initial conformation. Such a problem can be alleviated by distributing the torsion angle changes from the initial six angles to all the available torsion angles, resulting in small changes for many angles instead of large changes for a few. The angle changes can be distributed by minimizing an energy function that guides the dihedral angles into desirable regions in the space of closed loop conformations.

The loop closure procedure adopted in this work is as follows. We first perform initial loop closure by randomly selecting three residues and compute their six backbone dihedral angles (three ϕ and three ψ angles) by solving the analytical loop closure equation [20, 21]. As an optional next step, we adjust all the torsion angles simultaneously to minimize the following measure for deviation from Ramachandran-allowed regions

| (4) |

under the loop-closure constraint, where fRama(ϕ, ψ) is an energy function for a residue that represents a Ramachandran plot, and n is the number of loop residues that are neither glycine nor proline. The function fRama(ϕ, ψ) is a sum of the Lennard-Jones and Coulomb interactions among the non-side chain atoms within a dipeptide, as developed in Ref. [56] with the CHARMM22 parameters [57]. The same form of fRama is used for the 18 amino acids that are neither glycine nor proline. The two-dimensional energy contour of the dipeptide energy function has been shown to reproduce the dihedral angle distribution in the structural database much better than the hard-sphere repulsion potential energy of Ramachandran et al. [55]. We allowed free changes for the glycine angles because of their flexibility and fixed proline angles at the fragment angles because of the ϕ angle rigidity. Separate fRama functions for glycine, proline, and pre-proline residues such as in Ref. [58] may also be used if desired. Minimization of the function FRama enforces the torsion angles to lie within the allowed regions of the Ramachandran map for each residue.

Among the N variable torsion angles, {φ1, φ2, φ3, ···, φN−1, φN}, only N − 6 of them are independent under the loop closure constraint, and the minimization is performed in the N − 6 dimensional space of closed loops. For simplicity we choose {φ7, φ8, ···, φN} as the independent variable used for minimization, called the driver angles, and express the remaining 6 adjuster angles in terms of the driver angles. We then derive a formula for the gradient of FRama in the N − 6 dimensional space using chain rules as follows.

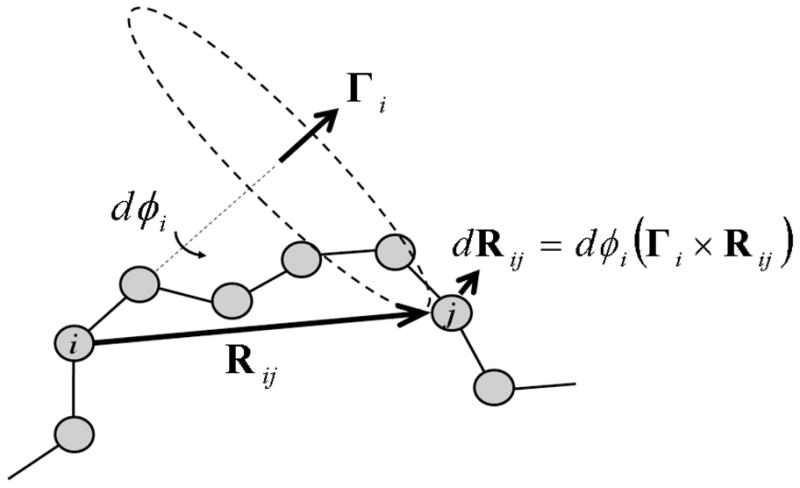

Let us denote the axis of φi-rotation by a unit vector Γi, and label the atom at the N-terminal of the rotation axis by i, as depicted in Fig. 2. For any atom j located in the C-terminal direction of the chain relative to the atom i, the variation of its position dRij due to an infinitesimal change of φi, dφi, is given by

FIG. 2.

The displacement of an atom j, dRj, when the torsion angle about the axis Γi changes by a small amount dφi is dRj = dφi (Γi × Rij).

| (5) |

where Rij is the position of the atom j relative to i.

Since the Cartesian coordinates of atoms in the framework region, the region outside the loop, are fixed under the loop closure constraint, dRj = Σi dRij = 0 for any atom j in the framework. In the current convention, the framework region at the N-terminal side of the loop is unaffected by the change of loop dihedral angles, and the C-terminal framework moves as a rigid body in the absence of the loop closure constraint. It is therefore necessary and sufficient to impose the following constraint for three distinct atoms A, B, and C in the C-terminal framework region:

| (6) |

Eq. (6) is a constraint on possible changes of the torsion angles dφi under the loop closure constraint. Considering i (= 1, ···, N) as the column index and j (= A, B, C) together with the space index μ (= x, y, z) as the row index α (= 1, ···, 9), the matrix

| (7) |

is a 9 × N matrix, and Eq. (6) is a system of 9 equations for N variables. However, it has to be noted that

| (8) |

which amounts to 3 identities among the 9 rows of Miα. These identities show that the distances between atoms A, B, and C are preserved,

| (9) |

when dRi’s are given by the rotation Eq. (5). Due to the three identities in Eq. (8), any 3 rows of Miμ can be expressed as linear combinations of the remaining 6 rows, and Eq. (6) is reduced to a system of 6 independent equations for N variables. Therefore, Eq. (6) can be used to express the change of the adjuster angles dφ1, ···, dφ6 for an arbitrary perturbation of the driver angles dφ7, ···, dφN.

Expressing Eq. (6) in terms of the driver angle perturbations, we get

| (10) |

The derivative of the adjuster angles with respect to the driver angles ∂φk/∂φi can then be obtained from the following linear equation:

| (11) |

For simplicity, we use N, Cα, and C′ atoms of the first residue in the C-terminal framework region as the three atoms A, B, and C, and solve Eq. (11) to obtain ∂φk/∂φi (k = 1, ···, 6; i = 7, ···, N) as a function of φi (i = 7, ···, N). The analytic form of the gradient for the function FRama in the space of closed loops is then

| (12) |

Using the analytic gradient formula, the minimization was carried out with a gradient-based quasi-Newton optimization method, L-BFGS-B [59]. It has to be noted that any differentiable function of the backbone torsion angles can be used in place of FRama for minimization. For example, empirical functions for torsion angle maps may be used by deriving analytical versions of the functions using spline methods [60]. Other empirical energy functions for multipeptides [61] may also be useful.

D. Screening of the Sampled Loop Conformations

After the loop closure, a screening procedure is performed for the Fiser loop set to compare with the results of RAPPER [7]. In the RAPPER program, each residue is sampled in the space of a fine-grained ϕ/ψ map obtained from the Ramachandran plot, and conformations that have steric clashes or that are impossible to satisfy loop closure are discarded during the loop building process [7]. Since we have not considered possible steric clashes for the loop conformations so far, we apply a screening step for a fairer comparison.

We employ the DFIRE potential [48], which has been derived from the distribution of inter-atomic distances found in a structure database and thus takes steric clashes into account effectively. Because the screening is performed before the side chain atoms are constructed, side chain atoms beyond Cβ atoms are not included for score calculation. We call this score DFIRE-β.

The purpose of the screening is to eliminate unphysical conformations with large steric clashes so that the overall qualities of the ensembles are improved. However, it is inevitable that some native-like conformations are eliminated as well in the process. After randomly generating 4000 conformations by fragment assembly and loop closure (and optional Ramachandran energy minimization) for each loop target, we score the resulting conformations using the DFIRE-β score and select the 1000 conformations with the best scores for further processing.

It is not possible for us to simply estimate the fraction of the discarded loops during sampling by RAPPER [7], but we found that if we select 1000 out of 4000 sampled conformations, more native-like conformations than the 1000 conformations sampled by RAPPER are obtained, as presented in the Results and Discussion section. In this four-fold sampling, only three quarters of the conformations are discarded, and this fraction is expected to be much smaller than the actual fraction of the conformations discarded in RAPPER due to steric clashes and impossibility of loop closure, which disfavors us in comparison.

E. Construction of the Side Chains and Final Section of the Model Structure

Although the new developments in this work mainly involve loop sampling, the current method by itself can be combined with pre-existing scoring functions to provide predicted loop structures. We present a model selection procedure here to illustrate such an application.

Since the fragments are collected from proteins whose sequences are different from that of the query, only backbone dihedral angles are obtained from the fragments. With backbone fixed, the optimal side chain conformations are constructed by selecting the side chain dihedral angles from Dunbrack’s backbone-dependent rotamer library [62]. Possible side chain conformations are finite combinations of rotamers, and the exact global minimum of a free energy function can be found using an efficient optimization algorithm based on graph theory [63], where the free energy function of SCWRL 3.0 is used, consisting of a one-body term proportional to the log of the rotamer probability and steric repulsions with backbone and other side chain atoms [64].

We found that steric clashes still remain after the side chain building for some model structures and tried force-field minimization to adjust backbone structures to accommodate the clashes. However, the model accuracy became worse (data not shown) probably because optimization of backbone results in the erasure of the database information contained in the initial backbone conformations.

The final model structures are selected from the conformations generated for the Fiser loop set using the DFIRE potential [48, 49] again, now in the all-atom form. DFIRE has been shown to be as successful in scoring loop decoy conformations as the force fields such as AMBER or OPLS with generalized Born solvation free energy [65, 66].

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. Loop Conformation Sampling

The loop sampling method developed here that combines fragment assembly and analytical loop closure (FALC) was applied to the 30 loop targets of lengths 4, 8, and 12 residues proposed by Canutescu and Dunbrack [27]. The loop set, chosen from a set of nonredundant X-ray crystallographic structures, was used to test the performance of several loop sampling algorithms including the Cyclic Coordinate Descent (CCD) algorithm [27] and the self-organizing algorithm (SOS) [47]. CCD is a robust iterative loop closure algorithm. It can be coupled with Ramachandran probability maps in a Monte Carlo fashion, resulting in preferential sampling in the Ramachandran maps. A recent loop construction method called self-organizing algorithm (SOS) iteratively superimposes small, rigid fragments (amide and Cα) and adjusts distances between atoms to satisfy loop closure and to consider steric conditions simultaneously. This method was reported to outperform the CCD method [47]. We previously tested a method that samples φ/ψ angles from Ramachandran maps using PLOP (Protein Local Optimization Program) [8] and closes the loop with analytical loop closure on the same loop set. This method, called CSJD in Ref. [20], is also compared together.

For each of the loops in the test set, the minimum backbone RMSDs from the crystal structure among 5000 conformations sampled by the following five methods are compared in Table II: the Ramachandran map CCD (from Table 2 of Ref. [27]), the CSJD method (from Table 1 of Ref. [20]), the SOS algorithm (from Table 1 of Ref. [47]), and the current methods (FALC and FALCm). In Table II, ‘FALC’ refers to the results of the loop closure by rotating six random torsion angles after fragment assembly, and ‘FALCm’ to the results of the gradient minimization after FALC, as described in Methods. Both FALC and FALCm perform better than CCD, CSJD, and SOS. In particular, our algorithms perform better than SOS in all 10 8-residue loop targets and 8 out of 10 12-residue loop targets. With the FALC method, the minimum RMSD improves from 1.19 Å to 0.78 Å and from 2.25 Å to 1.84 Å on average for the 8-, and 12-residue loops, respectively. The FALCm method show further improvements over the FALC method for the 8- and 12-residue loops from 0.78 Å to 0.72 Å and from 1.84 Å to 1.81 Å.

TABLE II.

The minimum backbone RMSD values of the loops sampled by CCD, CJSD, SOS, and by the methods developed here, FALC and FALCm.

| Loop | CCDa | CJSDb | SOSc | FALCd | FALCme | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-residue | 1dvjA_20 | 0.61 | 0.38 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.39 |

| 1dysA_47 | 0.68 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.20 | |

| 1eguA_404 | 0.68 | 0.36 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.22 | |

| 1ej0A_74 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.15 | |

| 1i0hA_123 | 0.62 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.17 | |

| 1id0A_405 | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.19 | |

| 1qnrA_195 | 0.49 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.23 | |

| 1qopA_44 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.13 | 0.28 | 0.30 | |

| 1tca_95 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.09 | |

| 1thfD_121 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.21 | |

| Average | 0.56 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.22 | |

| 8-residue | 1cruA_85 | 1.75 | 0.99 | 1.48 | 0.60 | 0.62 |

| 1ctqA_144 | 1.34 | 0.96 | 1.37 | 0.62 | 0.56 | |

| 1d8wA_334 | 1.51 | 0.37 | 1.18 | 0.96 | 0.78 | |

| 1ds1A_20 | 1.58 | 1.30 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 0.73 | |

| 1gk8A_122 | 1.68 | 1.29 | 0.96 | 0.79 | 0.62 | |

| 1i0hA_145 | 1.35 | 0.36 | 1.37 | 0.88 | 0.74 | |

| 1ixh_106 | 1.61 | 2.36 | 1.21 | 0.59 | 0.57 | |

| 1lam_420 | 1.60 | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.66 | |

| 1qopB_14 | 1.85 | 0.69 | 1.24 | 0.72 | 0.92 | |

| 3chbD_51 | 1.66 | 0.96 | 1.23 | 1.03 | 1.03 | |

| Average | 1.59 | 1.01 | 1.19 | 0.78 | 0.72 | |

| 12-residue | 1cruA_358 | 2.54 | 2.00 | 2.39 | 2.27 | 2.07 |

| 1ctqA_26 | 2.49 | 1.86 | 2.54 | 1.72 | 1.66 | |

| 1d4oA_88 | 2.33 | 1.60 | 2.44 | 0.84 | 0.82 | |

| 1d8wA 46 | 4.83 | 2.94 | 2.17 | 2.11 | 2.09 | |

| 1ds1A_282 | 3.04 | 3.10 | 2.33 | 2.16 | 2.10 | |

| 1dysA_291 | 2.48 | 3.04 | 2.08 | 1.83 | 1.67 | |

| 1eguA_508 | 2.14 | 2.82 | 2.36 | 1.68 | 1.71 | |

| 1f74A_11 | 2.72 | 1.53 | 2.23 | 1.33 | 1.44 | |

| 1qlwA_31 | 3.38 | 2.32 | 1.73 | 2.11 | 2.20 | |

| 1qopA_178 | 4.57 | 2.18 | 2.21 | 2.37 | 2.36 | |

| Average | 3.05 | 2.34 | 2.25 | 1.84 | 1.81 | |

RMSD values (in Å) taken from Table 2 of Ref. [27].

RMSD values (in Å) taken from Table 1 of Ref. [20].

RMSD values (in Å) taken from Table 1 of Ref. [47].

RMSD values (in Å) obtained from fragment assembly and initial loop closure.

RMSD values (in Å) obtained from minimization of the Ramachandran energy with the analytical gradient after FALC.

The current method is different from the Ramachandran map CCD method in two respects. First, the local backbone torsion angles are sampled in the fragment space here, but they are sampled from Ramachandran probability maps in CCD. Ramachandran probability maps contain information specific to the amino acid types only, but fragments obtained from the PSI-BLAST profiles provide sequence-specific information. Second, the loop closure is performed analytically here, but an iterative method is used in CCD.

The differences between the current method and the SOS method are also two-fold. First, the small fragments (amide and Cα) employed in SOS are chosen to satisfy local geometric constraints, but the fragments used here contain additional information on the sequence-specific conformational preferences that encompass the length of several residues as well as local geometry. Second, loop closure is accomplished by iterative distance adjustments in SOS but by a single step of analytical loop closure here.

We argue that the excellent performance of the current loop sampling method originates from both fragment assembly and analytical loop closure. The fact that the CJSD method shows better performance than the Ramachandran CCD, as presented in Table II, implies that analytical loop closure has an advantage over CCD. In addition, the fact that the current methods (FALC and FALCm) give better results than the CSJD method and SOS demonstrates the effectiveness of the current fragment assembly method.

CCD has been used with Rosetta for loop modeling [29], and analytical loop closure was also combined with Rosetta for loop reconstruction tests [24] showing substantial improvement in performance over the CCD-based Rosetta protocol. These methods involve extensive sampling guided by the Rosetta energy function, but the current method is more focused on sampling independent of energy function by reducing the search space effectively. Since our sampling method is an order of magnitude faster than these methods (data not shown), it would be promising to employ the current method for global optimization of an accurate energy function in the future.

Application of the target function minimization in analytical loop closure, referred to as FALCm here, improves the loop sampling results for the 8- and 12-residue loops, as discussed above. The improvement is not dramatic probably because it is more probable to close the loop with resulting angles in Ramachandran-allowed regions when more native-like angles are assembled from fragments in the initial stage. The analytical gradient formula still has a wide potential area of applications, for example in guiding loop sampling with target functions that favor hydrogen bonding to specific functional groups in protein-ligand binding problems or that favor interactions with known or predicted hot spot residues in protein-protein binding problems.

B. Loop Ensemble Generation with Screening

In order to test the feasibility of the application of the current method to loop ensemble generation, we carried out a loop reconstruction test on a subset of the loop target test set developed by Fiser et al. [46]. We consider only the targets used for the test in Ref. [7], where some of the targets in the original Fiser set were omitted due to poor qualities in the experimental structures. We also omit the shortest (and the easiest) loops of 2 and 3 residues. The resulting set consists of 317 targets, as shown in Table III.

TABLE III.

The main chain RMSD values of the loops sampled by RAPPER and by this work for the Fiser loop set.

| Loop |

RAPPERa |

FALCm4b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length | Targetsc | Rmind | Ravee | Rmind | Ravee |

| 4 | 35 | 0.43 | 1.65 | 0.33 | 0.92 |

| 5 | 35 | 0.53 | 2.27 | 0.44 | 1.63 |

| 6 | 36 | 0.69 | 3.06 | 0.47 | 2.34 |

| 7 | 38 | 0.78 | 3.79 | 0.58 | 2.74 |

| 8 | 32 | 1.11 | 4.16 | 0.84 | 3.69 |

| 9 | 37 | 1.29 | 5.00 | 0.95 | 4.21 |

| 10 | 37 | 1.67 | 5.66 | 1.45 | 5.07 |

| 11 | 33 | 1.99 | 6.71 | 1.47 | 5.76 |

| 12 | 34 | 2.21 | 6.96 | 1.74 | 6.31 |

Taken from Table 3 of Ref. [7].

Obtained from screening with the DFIRE-β potential after the four-fold sampling with fragment assembly, analytical loop closure, and Ramachandran minimization.

The number of loop targets.

Minimum main-chain RMSD (in Å) averaged over the loop targets.

Average main-chain RMSD (in Å) averaged over the loop targets.

The results of loop ensemble generation are displayed in Table III with the results of RAPPER reported in Table 3 of Ref. [7]. The minimum main chain RMSD and the average main chain RMSD of the 1000 conformations, obtained after screening 4000 conformations sampled by FALCm, were examined for each target, and their average values Rave and Rmin are displayed for each loop length. The main chain RMSD was calculated using the coordinates of N, Cα, C′, and O atoms, following Ref. [7].

In the ensemble generation test by RAPPER, 1000 conformations were generated screening out loops with possible steric clashes or with too extended conformations for loop closure during the loop building process. Although it is not possible for us to accurately estimate the fraction of the loops that were screened out in the RAPPER program, the fraction must be much larger than 3/4, considering the probabilities of typical loop closure and steric clash.

The performance of our method in generating native-like conformations are significantly better than RAPPER, both in Rave and Rmin, as can be seen from Table III. There are more improvements for longer loops, especially in the minimum RMSD. It has to be noted that only a four-fold random sampling was performed for an illustrative comparison. The success of this simple application shows the potential of the current method for loop ensemble generation enriched with native-like conformations when combined with more conformational search and more extensive use of good scoring functions [8, 67].

C. Loop Model Selection with DFIRE

From the ensemble of 1000 conformations generated for each target in the Fiser set, the final model was selected by scoring the conformations with the DFIRE potential after side chain optimization, as presented in Methods. As compared in Table IV, the accuracy of the loop model prediction is improved significantly compared to that reported in Ref. [49] in which the RAPPER ensembles are also scored with DIFRE. This result demonstrates that the better-quality conformational ensembles obtained by this study can lead to higher modeling accuracy.

TABLE IV.

The average RMSD values of the lowest energy conformations obtained by DFIRE scoring of the RAPPER ensemble sets and those generated by FALCm4 presented in Table III.

| Loop length | RAPPERa | FALCm4 |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 0.86 | 0.54 |

| 5 | 1.00 | 0.92 |

| 6 | 1.85 | 1.36 |

| 7 | 1.51 | 1.17 |

| 8 | 2.11 | 1.87 |

| 9 | 2.58 | 2.08 |

| 10 | 3.60 | 3.09 |

| 11 | 4.25 | 3.43 |

| 12 | 4.32 | 3.84 |

Taken from Table S2 of Ref. [49].

IV. CONCLUSION

In this paper, we presented a novel method for protein loop sampling, based on fragment assembly and analytical loop closure. Efficient sampling is possible because the search space is drastically reduced by sampling in the space of closed loops and in the space of fragments obtained by utilizing sequence-specific information.

We also developed an analytic formula for the gradient of a target function that depends on a set of torsion angles satisfying the loop closure constraint. This gradient can be used for efficient sampling of closed loops satisfying an additional requirement of optimizing a target function.

The efficiency of our sampling method was demonstrated by performing loop reconstruction tests on two sets of loop targets whose lengths range from 4 to 12. We found that the ability of our method for generating native-like conformations is significantly better than the previous methods based on amino acid-specific information only and less elaborate loop closure methods. It is remarkable that such a result can be obtained when no or minimal level of energy information is used in the loop ensemble generation.

One notable feature of our method is that sampling and scoring procedures are separated. Given the efficiency of our method in generating native-like conformations, the current method would also be useful for testing discriminatory powers of various scoring functions and developing a new one.

Although the current tests were restricted to the loop reconstruction problem, where the framework region is fixed to the experimentally determined native structure, the efficiency of the current sampling method would allow application to a more challenging task of modeling loops in the context of the comparative modeling problem, where the framework region is given by templates and therefore contain inherent uncertainties.

Acknowledgments

JL was supported by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST) (No. R01-2008-000-11299-0). EAC acknowledges partial support from NIH-NIGMS Grants No. R01-GM081710 and R01-GM090205.

References

- 1.Lesk AM, Lo Conte L, Hubbard TJP. Assessment of novel fold targets in CASP4: Predictions of three-dimensional structures, secondary structures, and interresidue contacts. Proteins. 2001;(Suppl 5):98–118. doi: 10.1002/prot.10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aloy P, Stark A, Hadley C, Russel RB. Predictions Without Templates: New Folds, Secondary Structure, and Contacts in CASP5. Proteins. 2003;53:436–456. doi: 10.1002/prot.10546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vincent JJ, Tai CH, Sathyanarayana BK, Lee B. Assessment of CASP6 predictions for new and nearly new fold targets. Proteins. 2005;(Suppl 7):67–83. doi: 10.1002/prot.20722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moult J, Fidelis K, Rost B, Hubbard T, Tramontano A. Critical assessment of methods of protein structure prediction (CASP) - Round 6. Proteins. 2005;(Suppl 7):3–7. doi: 10.1002/prot.20716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker D, Sali A. Protein Structure Prediction and Structural Genomics. Science. 2001;294:93–96. doi: 10.1126/science.1065659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Bakker PIW, DePristo MA, Burke DF, Blundell TL. Ab initio construction of polypeptide fragments: Accuracy of loop decoy discrimination by an all-atom statistical potential and the AMBER force field with the Generalized Born solvation model. Proteins. 2002;51:21–40. doi: 10.1002/prot.10235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DePristo MA, de Bakker PIW, Lovell SC, Blundell TL. Ab initio construction of polypeptide fragments: Efficient generation of accurate, representative ensembles. Proteins. 2002;51:41–55. doi: 10.1002/prot.10285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobson MP, Pincus DL, Rapp CS, Day TJF, Honig B, Shaw DE, Friesner RA. A hierarchical approach to all-atom protein loop prediction. Proteins. 2004;55:351–367. doi: 10.1002/prot.10613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mönnigmann M, Floudas CA. Protein loop structure prediction with flexible stem geometries. Proteins. 2005;61:748–762. doi: 10.1002/prot.20669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu K, Pincus DL, Zhao S, Friesner RA. Long loop prediction using the protein local optimization program. Proteins. 2006;65:438–452. doi: 10.1002/prot.21040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng H-P, Yang A-S. Modeling protein loops with knowledge-based prediction of sequence-structure alignment. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2836–2842. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sellers BD, Zhu K, Zhao S, Friesner RA, Jacobson MP. Toward better refinement of comparative models: Predicting loops in inexact environments. Proteins. 2008;72:959–971. doi: 10.1002/prot.21990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rohl CA, Strauss CEM, Chivian D, Baker D. Modeling structurally variable regions in homologous proteins with rosetta. Proteins. 2004;55:656–677. doi: 10.1002/prot.10629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Go N, Scheraga HA. Ring Closure and Local Conformational Deformations of Chain Molecules. Macromolecules. 1970;3:178–187. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruccoleri RE, Karplus M. Prediction of the folding of short polypeptide segments by uniform conformational sampling. Biopolymers. 1987;26:137–168. doi: 10.1002/bip.360260114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruccoleri RE, Karplus M. Chain closure with bond angle variations. Macromolecules. 1985;18:2767–2773. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu MG, Deem MW. Analytical rebridging Monte Carlo: Application to cis/trans isomerization in proline-containing, cyclic peptides. J Chem Phys. 1999;111:6625–6632. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dinner AR. Local deformations of polymers with nonplanar rigid main-chain internal coordinates. J Comput Chem. 2000;21:1132–1144. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wedemeyer WJ, Scheraga HA. Exact analytical loop closure in proteins using polynomial equations. J Comput Chem. 1999;20:819–844. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199906)20:8<819::AID-JCC8>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coutsias EA, Seok C, Jacobson MP, Dill K. A Kinematic View of Loop Closure. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:510–528. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coutsias EA, Seok C, Wester MJ, Dill K. Resultants and Loop Closure. Int J Quantum Chem. 2006;106:176–189. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cortes J, Simeon T, Remaud-Simeon M, Tran V. Geometric algorithms for the conformational analysis of long protein loops. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:956–967. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noonan K, O’Brien D, Snoeyink J. Probik: Protein backbone motion by inverse kinematics. Int J Robotics Res. 2005;24:971–982. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandell DJ, Coutsias EA, Kortemme T. Sub-angstrom accuracy in protein loop reconstruction by robotics-inspired conformational sampling. Nature Methods. 2009;6:551–552. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0809-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fine RM, Wang H, Shenkin PS, Yarmush DL, Levinthal C. Predicting antibody hypervariable loop conformations II: Minimization and molecular dynamics studies of MCPC603 from many randomly generated loop conformations. Proteins. 1986;1:342–362. doi: 10.1002/prot.340010408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L-CT, Chen CC. A Combined Optimization Method for Solving the Inverse Kinematics Problem of Mechanical Manipulators. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON ROBOTICS AND AUTOMATION. 1991 AUGUST;7(4):489. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canutescu AA, Dunbrack RL., Jr Cyclic coordinate descent: A robotics algorithm for protein loop closure. Protein Sci. 2003;12:963–972. doi: 10.1110/ps.0242703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee A, Streinu I, Brock O. A methodology for efficiently sampling the conformation space of molecular structures. Phys Biol. 2005;2:S108–115. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/2/4/S05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C, Bradley P, Baker D. Protein-protein docking with backbone flexibility. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:503–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee D-S, Seok C, Lee J. Protein Loop Modeling Using Fragment Assembly. J Korean Phys Soc. 2008;52:1137–1142. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abagyan RA, Totrov MM. Biased Probability Monte Carlo Conformational Searches and Electrostatic Calculations for Peptides and Proteins. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:983–1002. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simons KT, Kooperberg C, Huang E, Baker D. Assembly of protein tertiary structures from fragments with similar local sequences using simulated annealing and bayesian scoring functions. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:209–225. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rohl C, Strauss C, Misura K, Baker D. Protein Structure Prediction Using Rosetta. Methods Enzymol. 2004;383:66–93. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)83004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones DT. Predicting novel protein folds by using FRAGFOLD. Proteins. 2001;(Suppl 5):127–132. doi: 10.1002/prot.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones DT, Bryson K, Coleman A, McGuffin LJ, Sadowski MI, Sodhi JS, Ward JJ. Prediction of novel and analogous folds using fragment assembly and fold recognition. Proteins. 2005;(Suppl 7):143–151. doi: 10.1002/prot.20731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chikenji G, Fujitsuka Y, Takada S. A reversible fragment assembly method for de novo protein structure prediction. J Chem Phys. 2003;119:6895–6903. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujitsuka Y, Chikenji G, Takada S. SimFold energy function for de novo protein structure prediction: Consensus with Rosetta. Proteins. 2006;62:381–398. doi: 10.1002/prot.20748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chikenji G, Fujitsuka Y, Takada S. Shaping up the protein folding funnel by local interaction: Lesson from a structure prediction study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3141–3146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508195103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee J, Kim S-Y, Joo K, Kim I, Lee J. Prediction of protein tertiary structure using PROFESY, a novel method based on fragment assembly and conformational space annealing. Proteins. 2004;56:704–714. doi: 10.1002/prot.20150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee J, Kim S-Y, Lee J. Protein structure prediction based on fragment assembly and parameter optimization. Biophys Chem. 2005;115:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2004.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee J, Kim S-Y, Lee J. Protein Structure Prediction Based on Fragment Assembly and the -Strand Pairing Energy Function. J Korean Phys Soc. 2005;46:707–712. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim S-Y, Lee W, Lee J. Protein folding using fragment assembly and physical energy function. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:194908. doi: 10.1063/1.2364500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim T-K, Lee J. Exhaustive Enumeration of Fragment-Assembled Protein Conformations. J Korean Phys Soc. 2008;52:137–142. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cho K-H, Lee J, Kim T-K. Protein Structure Prediction Using the Hybrid Energy Function, Fragment Assembly and Double Optimization. J Korean Phys Soc. 2008;52:143–151. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cho K-H, Lee J. Protein Structure Prediction Using a Hybrid Energy Function and an Exact Enumeration. J Korean Phys Soc. 2008;53:873. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fiser A, Do RKG, Sali A. Modeling of loops in protein structures. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1753–1773. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu P, Zhu F, Rassokhin DN, Agrafiotis DK. A self-organizing algorithm for modeling protein loops. PLOS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou H, Zhou Y. Distance-scaled, finite ideal-gas reference state improves structure-derived potentials of mean force for structure selection and stability prediction. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2714–2726. doi: 10.1110/ps.0217002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang C, Liu S, Zhou Y. Accurate and efficient loop selections by the DFIRE-based all-atom statistical potential. Protein Sci. 2004;13:391–399. doi: 10.1110/ps.03411904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brenner SE, Koehl P, Levitt M. The ASTRAL compendium for protein structure and sequence analysis. Nuc Acids Res. 2000;28:254–256. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sim J, Kim S-Y, Lee J. Prediction of protein solvent accessibility using fuzzy k-nearest neighbor method. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2844–2849. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim S-Y, Sim J, Lee J. Double Optimization for Design of Protein Energy Function. In: Istrail S, Pevzner P, Waterman M, editors. Computational Intelligence and Bioinformatics. Heidelberg: Springer Berlin; 2006. pp. 562–670. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nuc Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones DT. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:195–202. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramachandran GN, Ramakrishnan C, Sasisekharan V. Stereochemistry of polypeptide chain configurations. J Mol Biol. 1963;7:95–99. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(63)80023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ho BK, Thomas A, Brasseur R. Revisiting the Ramachandran plot: Hard-sphere repulsion, electrostatics, and H-bonding in the α-helix. Protein Science. 2003;12:2508–2522. doi: 10.1110/ps.03235203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.MacKerell AD, Jr, Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL, Jr, Evanseck JD, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, et al. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics Studies of proteins. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ho BK, Brasseur R. The Ramachandran plots of glycine and pre-proline. BMC Str Biol. 2005;5:14–24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu C, Byrd RH, Nocedal J. L-BFGS-B: Algorithm 778: L-BFGS-B, FORTRAN routines for large scale bound constrained optimization. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software. 1997;23:550–560. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rata IA, Li Y, Jakobsson E. Backbone Statistical Potential from Local Sequence-Structure Interactions in Protein Loops. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:1859. doi: 10.1021/jp909874g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ting D, Wang G, Shapovalov M, Mitra R, Jordan MI, Dunbrack RL., Jr Neighbor-Dependent Ramachandran Probability Distributions of Amino Acids Developed from a Hierarchical Dirichlet Process Model. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6:e1000763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dunbrack RL, Karplus M. Backbone-dependent rotamer library for proteins: application to side-chain prediction. J Mol Biol. 1993;230:543–574. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Canutescu AA, Shelenkov AA, Dunbrack RL., Jr A graph-theory algorithm for rapid protein side-chain prediction. Protein Sci. 2003;12:2001–2014. doi: 10.1110/ps.03154503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bower MJ, Cohen FE, Dunbrack RL., Jr Prediction of Protein Side-chain Rotamers from a Backbone-dependent Rotamer Library: A New Homology Modeling Tool. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:1268. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Still WC, Tempczyk A, Hawley RC, Hendrickson T. Semianalytical treatment of solvation for molecular mechanics and dynamics. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:6127–6129. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qiu D, Shenkin PS, Hollinger FP, Still WC. The GB/SA Continuum Model for Solvation. A Fast Analytical Method for the Calculation of Approximate Born Radii. J Phys Chem A. 1997;101:3005–3014. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin MS, Head-Gordon T. Improved Energy Selection of Nativelike Protein Loops from Loop Decoys. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008;4:515–521. doi: 10.1021/ct700292u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]