Abstract

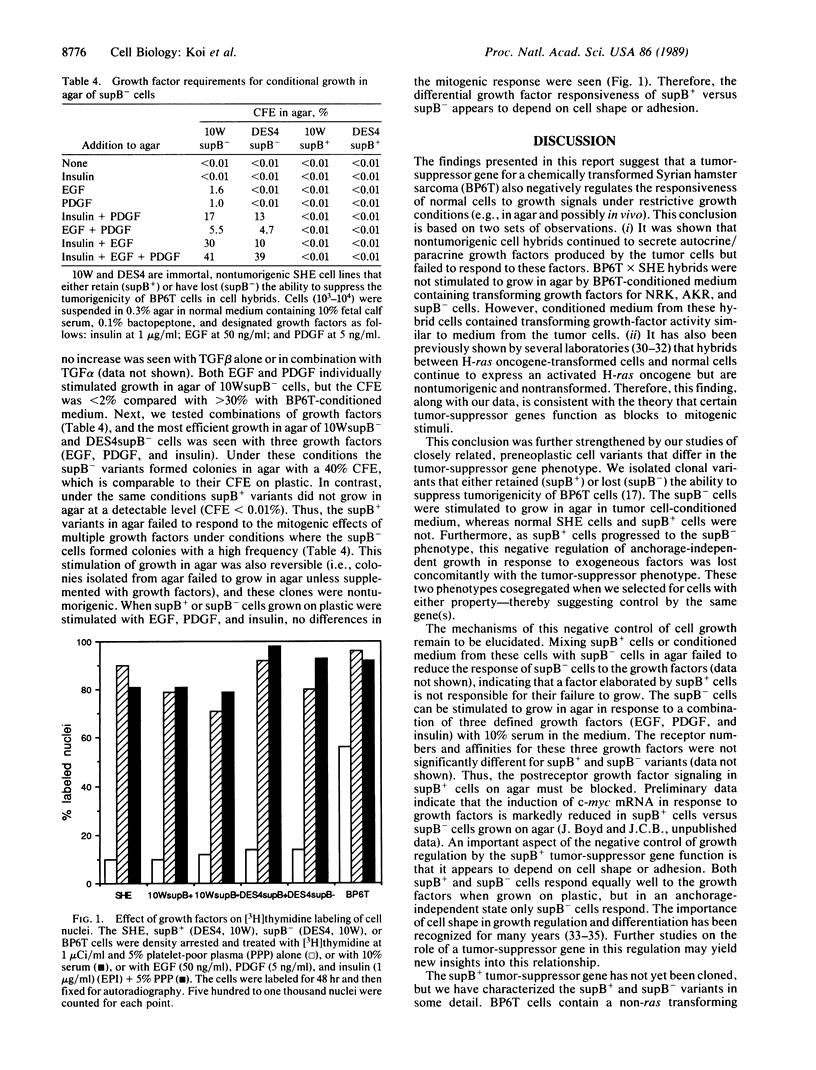

Tumor-suppressor genes control the neoplastic phenotype of tumor cells, but the function of these genes in normal cells is unknown. In this report we show that the loss of a tumor-suppressor gene function releases negative controls on the growth of cells in agar. This conclusion is based on observations of cell hybrids and studies of cell variants that have retained or lost a tumor-suppressor gene function. Nontumorigenic cell hybrids between normal Syrian hamster embryo cells and a benzo[a]pyrene-transformed tumor-cell line (BP6T) continued to secrete autocrine and/or paracrine growth factors produced by the tumor cells but failed to respond to these factors by growing in agar. Normal diploid cells also failed to grow in agar in response to the growth factors produced by the tumor cells. Clonal variants of nontumorigenic, immortal Syrian hamster cell lines were isolated that either retained (termed supB+) or had lost (termed supB-) the ability to suppress tumorigenicity of BP6T tumor cells after cell hybridization. Neither supB+ nor supB- variants grew in agar under conditions that allowed efficient growth of the tumor cells. However, supB- cells were reversibly induced to grow in agar with high colony-forming efficiencies in the presence of tumor cell-conditioned medium or by supplementation of the medium with a combination of growth factors. Under the same conditions, the supB+ cells failed to grow in agar. This enhanced growth-factor responsiveness in agar was used to select for supB- variants existing at a low frequency in the supB+ population. These two phenotypes, loss of tumor-suppressor function and enhanced growth-factor responsiveness in agar, were seen to cosegregate. These results indicate the tumor-suppressor gene function in these cells negatively regulates the growth response of cells in agar to mitogenic stimuli. This growth regulation may depend on cell shape or adhesion because supB+ and supB- cells grown attached to plastic responded similarly to growth factors.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Armelin H. A., Armelin M. C., Kelly K., Stewart T., Leder P., Cochran B. H., Stiles C. D. Functional role for c-myc in mitogenic response to platelet-derived growth factor. Nature. 1984 Aug 23;310(5979):655–660. doi: 10.1038/310655a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J. C. A National Institutes of Health Workshop Report. Cellular and molecular mechanisms for suppression and reversion of tumorigenicity. A Chemical Pathology Study Section workshop. Cancer Res. 1987 May 1;47(9):2514–2520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J. C., Ts'o P. O. Evidence for the progressive nature of neoplastic transformation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Aug;75(8):3761–3765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen-Pope D. F., Vogel A., Ross R. Production of platelet-derived growth factor-like molecules and reduced expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptors accompany transformation by a wide spectrum of agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Apr;81(8):2396–2400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.8.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavenee W. K., Dryja T. P., Phillips R. A., Benedict W. F., Godbout R., Gallie B. L., Murphree A. L., Strong L. C., White R. L. Expression of recessive alleles by chromosomal mechanisms in retinoblastoma. 1983 Oct 27-Nov 2Nature. 305(5937):779–784. doi: 10.1038/305779a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavenee W. K., Koufos A., Hansen M. F. Recessive mutant genes predisposing to human cancer. Mutat Res. 1986 Jul;168(1):3–14. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(86)90019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig R. W., Sager R. Suppression of tumorigenicity in hybrids of normal and oncogene-transformed CHEF cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Apr;82(7):2062–2066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.7.2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J., Moscona A. Role of cell shape in growth control. Nature. 1978 Jun 1;273(5661):345–349. doi: 10.1038/273345a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friend S. H., Bernards R., Rogelj S., Weinberg R. A., Rapaport J. M., Albert D. M., Dryja T. P. A human DNA segment with properties of the gene that predisposes to retinoblastoma and osteosarcoma. Nature. 1986 Oct 16;323(6089):643–646. doi: 10.1038/323643a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung Y. K., Murphree A. L., T'Ang A., Qian J., Hinrichs S. H., Benedict W. F. Structural evidence for the authenticity of the human retinoblastoma gene. Science. 1987 Jun 26;236(4809):1657–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.2885916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser A. G., Der C. J., Marshall C. J., Stanbridge E. J. Suppression of tumorigenicity with continued expression of the c-Ha-ras oncogene in EJ bladder carcinoma-human fibroblast hybrid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Jul;83(14):5209–5213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer T. M., Annab L. A., Barrett J. C. Characterization of activated proto-oncogenes in chemically transformed Syrian hamster embryo cells. Mol Carcinog. 1988;1(3):180–188. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940010306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goustin A. S., Leof E. B., Shipley G. D., Moses H. L. Growth factors and cancer. Cancer Res. 1986 Mar;46(3):1015–1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris H. The analysis of malignancy by cell fusion: the position in 1988. Cancer Res. 1988 Jun 15;48(12):3302–3306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay E. D. Matrix-cytoskeletal interactions in the developing eye. J Cell Biochem. 1985;27(2):143–156. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240270208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan P. L., Ozanne B. Cellular responsiveness to growth factors correlates with a cell's ability to express the transformed phenotype. Cell. 1983 Jul;33(3):931–938. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama H., Sugimoto Y., Matsuzaki T., Ikawa Y., Noda M. A ras-related gene with transformation suppressor activity. Cell. 1989 Jan 13;56(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90985-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein G. The approaching era of the tumor suppressor genes. Science. 1987 Dec 11;238(4833):1539–1545. doi: 10.1126/science.3317834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson A. G., Jr Hereditary cancer, oncogenes, and antioncogenes. Cancer Res. 1985 Apr;45(4):1437–1443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koi M., Barrett J. C. Loss of tumor-suppressive function during chemically induced neoplastic progression of Syrian hamster embryo cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Aug;83(16):5992–5996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.16.5992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. H., Bookstein R., Hong F., Young L. J., Shew J. Y., Lee E. Y. Human retinoblastoma susceptibility gene: cloning, identification, and sequence. Science. 1987 Mar 13;235(4794):1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.3823889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leof E. B., Proper J. A., Moses H. L. Modulation of transforming growth factor type beta action by activated ras and c-myc. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Jul;7(7):2649–2652. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.7.2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuto F., Del Monte P., Barreca A., Alama A., Cariola G., Giordano G. Evidence for autocrine mitogenic stimulation by somatomedin-C/insulin-like growth factor I on an established human lung cancer cell line. Cancer Res. 1988 Jul 1;48(13):3716–3719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphree A. L., Benedict W. F. Retinoblastoma: clues to human oncogenesis. Science. 1984 Mar 9;223(4640):1028–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.6320372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshimura M., Gilmer T. M., Barrett J. C. Nonrandom loss of chromosome 15 in Syrian hamster tumours induced by v-Ha-ras plus v-myc oncogenes. Nature. 1985 Aug 15;316(6029):636–639. doi: 10.1038/316636a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshimura M., Koi M., Ozawa N., Sugawara O., Lamb P. W., Barrett J. C. Role of chromosome loss in ras/myc-induced Syrian hamster tumors. Cancer Res. 1988 Mar 15;48(6):1623–1632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pledger W. J., Stiles C. D., Antoniades H. N., Scher C. D. Induction of DNA synthesis in BALB/c 3T3 cells by serum components: reevaluation of the commitment process. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Oct;74(10):4481–4485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.10.4481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers S., Fisher P. B., Pollack R. Analysis of the reduced growth factor dependency of simian virus 40-transformed 3T3 cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1984 Aug;4(8):1572–1576. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.8.1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozengurt E. Early signals in the mitogenic response. Science. 1986 Oct 10;234(4773):161–166. doi: 10.1126/science.3018928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sager R. Genetic suppression of tumor formation: a new frontier in cancer research. Cancer Res. 1986 Apr;46(4 Pt 1):1573–1580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer R., Iyer J., Iten E., Nirkko A. C. Partial reversion of the transformed phenotype in HRAS-transfected tumorigenic cells by transfer of a human gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Mar;85(5):1590–1594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon E., Voss R., Hall V., Bodmer W. F., Jass J. R., Jeffreys A. J., Lucibello F. C., Patel I., Rider S. H. Chromosome 5 allele loss in human colorectal carcinomas. Nature. 1987 Aug 13;328(6131):616–619. doi: 10.1038/328616a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino V., Drozdoff V., McKinney M. D., Zeitz L., Fleissner E. Potentiation of growth factor activity by exogenous c-myc expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Nov;83(21):8167–8171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn M. B., Roberts A. B. Autocrine growth factors and cancer. 1985 Feb 28-Mar 6Nature. 313(6005):745–747. doi: 10.1038/313745a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanbridge E. J., Der C. J., Doersen C. J., Nishimi R. Y., Peehl D. M., Weissman B. E., Wilkinson J. E. Human cell hybrids: analysis of transformation and tumorigenicity. Science. 1982 Jan 15;215(4530):252–259. doi: 10.1126/science.7053574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern D. F., Roberts A. B., Roche N. S., Sporn M. B., Weinberg R. A. Differential responsiveness of myc- and ras-transfected cells to growth factors: selective stimulation of myc-transfected cells by epidermal growth factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Mar;6(3):870–877. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.3.870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiles C. D. The molecular biology of platelet-derived growth factor. Cell. 1983 Jul;33(3):653–655. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomassen D. G., Gilmer T. M., Annab L. A., Barrett J. C. Evidence for multiple steps in neoplastic transformation of normal and preneoplastic Syrian hamster embryo cells following transfection with Harvey murine sarcoma virus oncogene (v-Ha-ras). Cancer Res. 1985 Feb;45(2):726–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker R. F., Volkenant M. E., Branum E. L., Moses H. L. Comparison of intra- and extracellular transforming growth factors from nontransformed and chemically transformed mouse embryo cells. Cancer Res. 1983 Apr;43(4):1581–1586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vennström B., Bravo R. Anchorage-independent growth of v-myc-transformed Balb/c 3T3 cells is promoted by platelet-derived growth factor or co-transformation by other oncogenes. Oncogene. 1987;1(3):271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt F. M., Jordan P. W., O'Neill C. H. Cell shape controls terminal differentiation of human epidermal keratinocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Aug;85(15):5576–5580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman B. E., Saxon P. J., Pasquale S. R., Jones G. R., Geiser A. G., Stanbridge E. J. Introduction of a normal human chromosome 11 into a Wilms' tumor cell line controls its tumorigenic expression. Science. 1987 Apr 10;236(4798):175–180. doi: 10.1126/science.3031816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman B., Aaronson S. A. Members of the src and ras oncogene families supplant the epidermal growth factor requirement of BALB/MK-2 keratinocytes and induce distinct alterations in their terminal differentiation program. Mol Cell Biol. 1985 Dec;5(12):3386–3396. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.12.3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Asua L. J., O'Farrell M. K., Clingan D., Rudland P. S. Temporal sequence of hormonal interactions during the prereplicative phase of quiescent cultured 3T3 fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Sep;74(9):3845–3849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.9.3845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]