Abstract

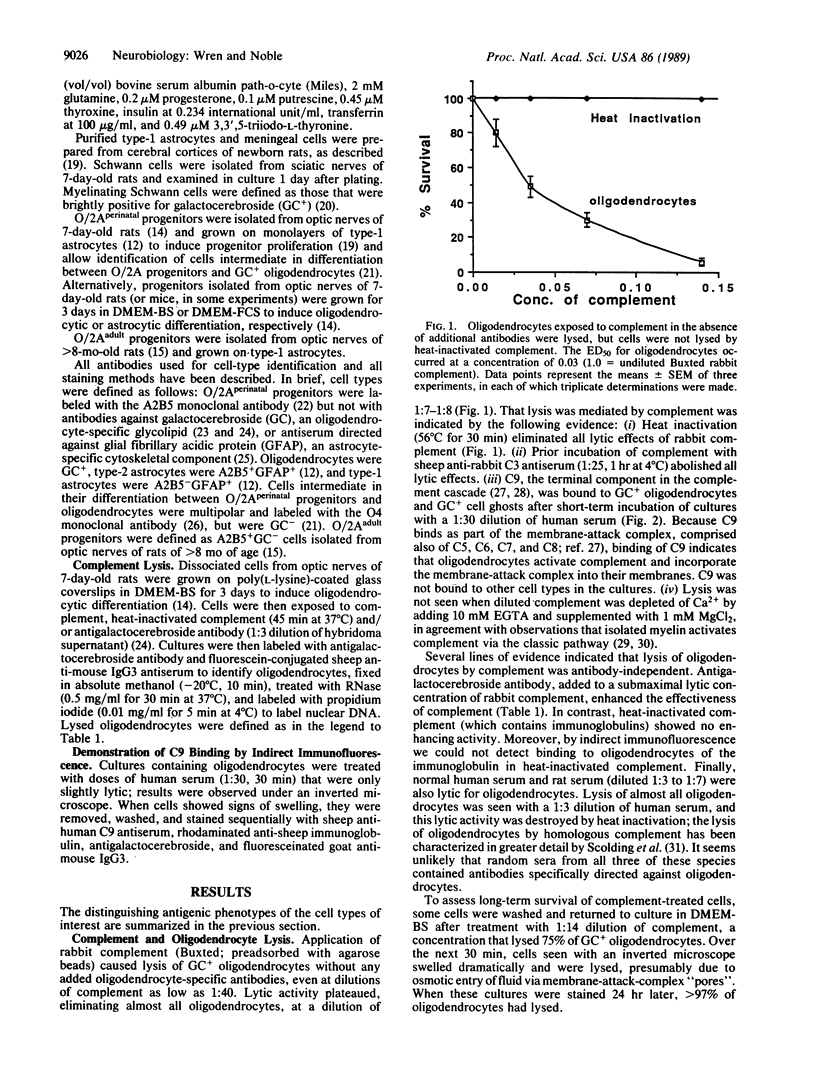

The central nervous system of individuals with multiple sclerosis contains lesions specifically characterized by breakdown of myelin sheaths associated with a general failure of repair of demyelinating damage. The cause of myelin breakdown is unknown. Although immune mechanisms have been implicated in this breakdown, no convincing demonstrations of specific immune reaction against myelin have yet been provided in multiple sclerosis patients. Similarly, the cellular biological mechanisms which underlie the failure of myelin repair are unknown. We have found that (i) oligodendrocytes, the cells that produce myelin sheaths in the central nervous system, and (ii) oligodendrocyte/type-2 astrocyte (O/2A) progenitor cells derived from optic nerves of adult rats bind and activate complement in the absence of antibody in vitro, leading to destruction of these cells. Susceptibility to antibody-independent lysis by complement was a cell-type-specific trait of oligodendrocytes and adult O/2A progenitors and was not shared by perinatal O/2A progenitors, type-2 astrocytes, type-1 astrocytes, meningeal cells, or Schwann cells. We suggest that the susceptibility of oligodendrocytes and adult O/2A progenitor cells to complement-induced lysis, combined with other specific properties of adult O/2A progenitors, are consistent with--and may be a contributing factor--both in the generation of demyelinating lesions in multiple sclerosis and also in the failure of these lesions to be successfully repaired in adult multiple sclerosis patients.

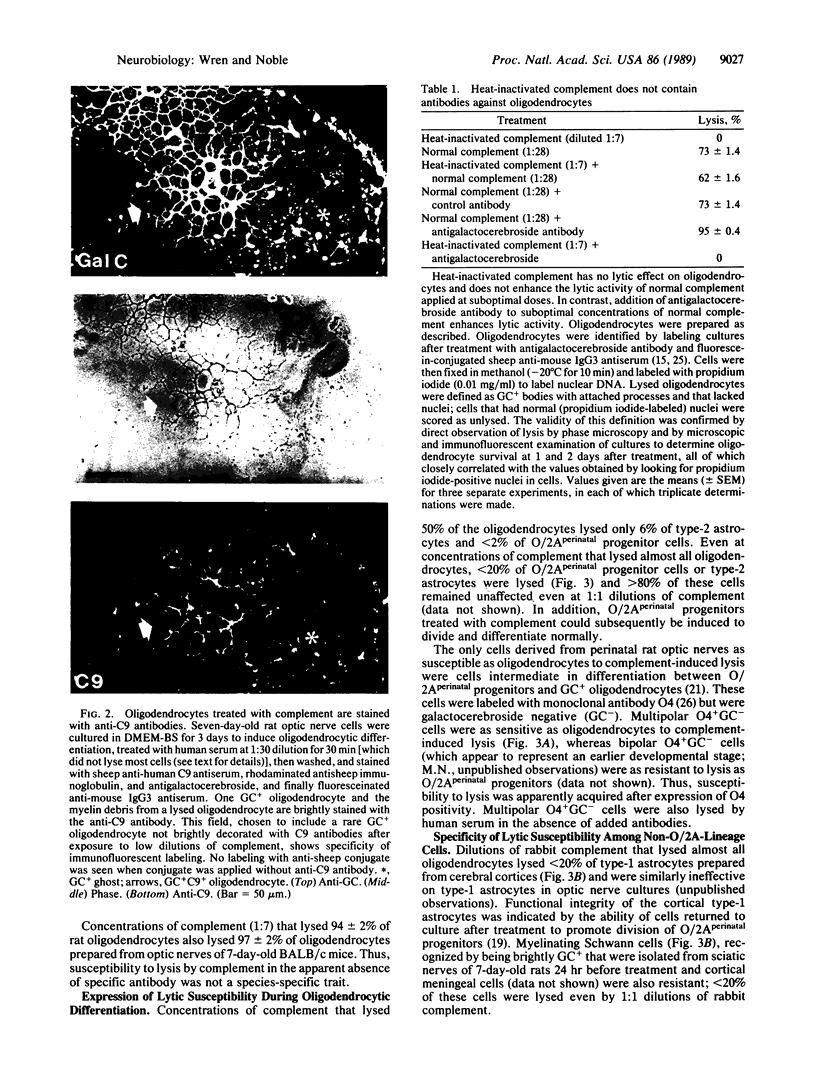

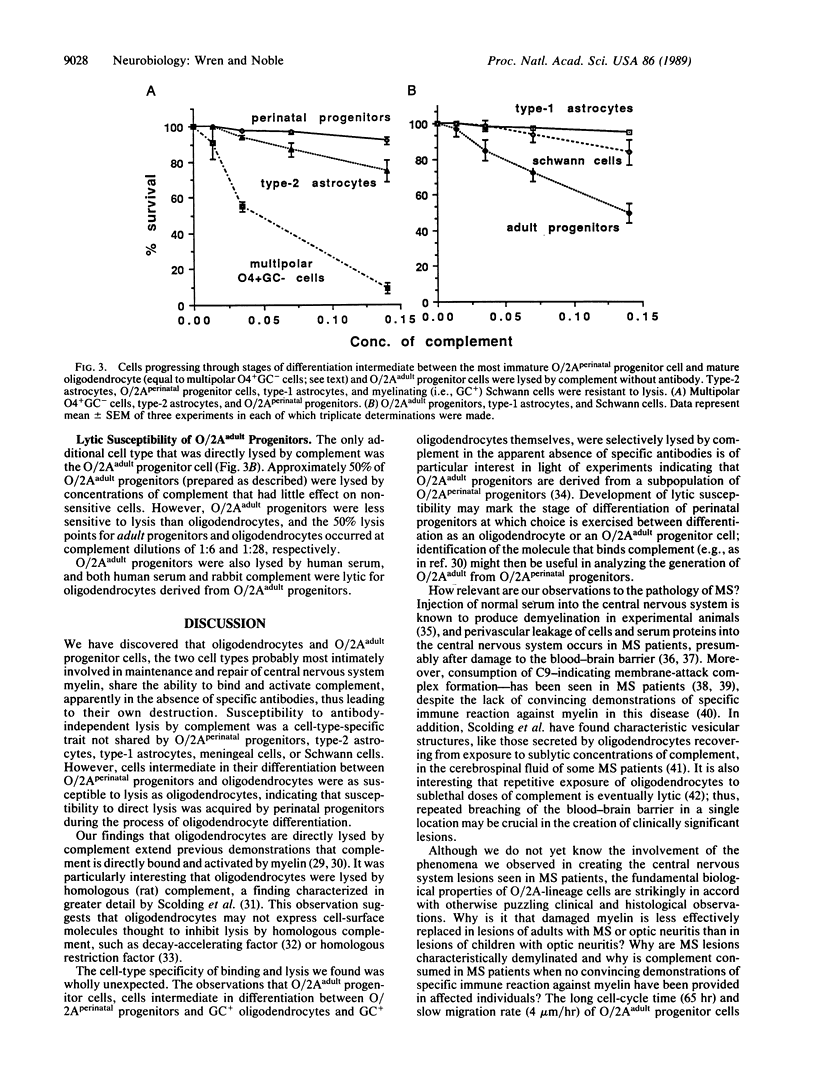

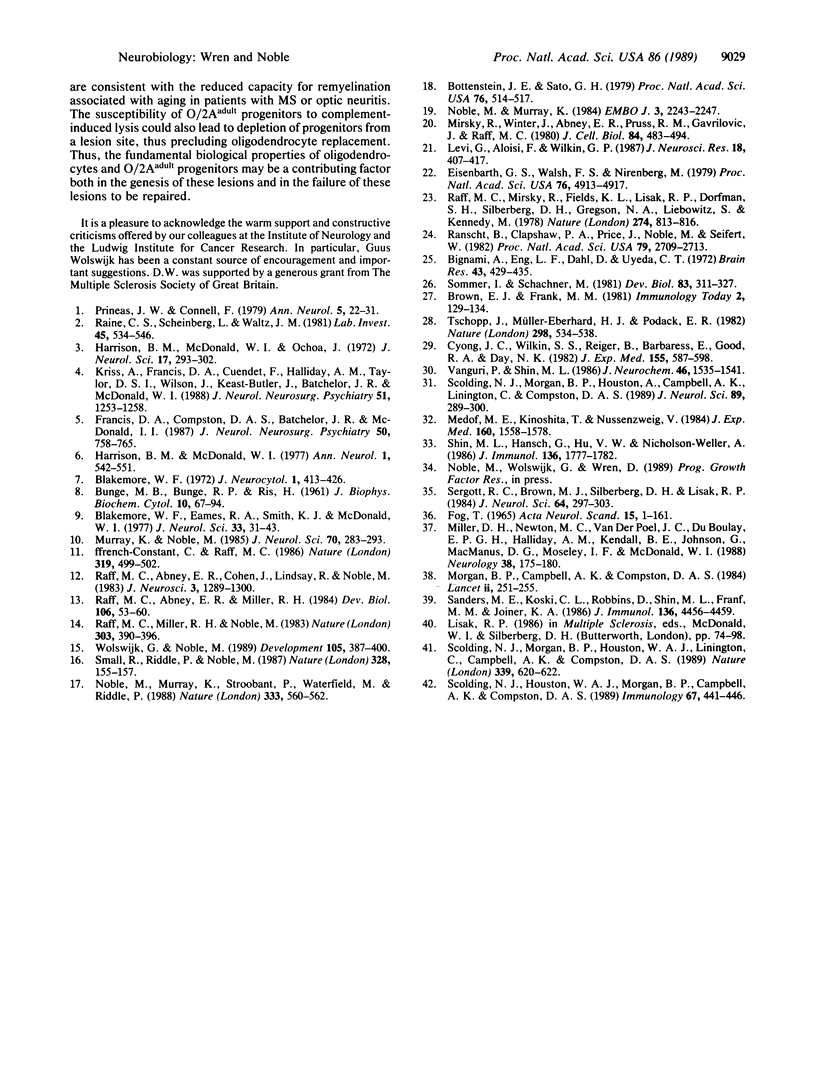

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BUNGE M. B., BUNGE R. P., RIS H. Ultrastructural study of remyelination in an experimental lesion in adult cat spinal cord. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1961 May;10:67–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.10.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignami A., Eng L. F., Dahl D., Uyeda C. T. Localization of the glial fibrillary acidic protein in astrocytes by immunofluorescence. Brain Res. 1972 Aug 25;43(2):429–435. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90398-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore W. F., Eames R. A., Smith K. J., McDonald W. I. Remyelination in the spinal cord of the cat following intraspinal injections of lysolecithin. J Neurol Sci. 1977 Aug;33(1-2):31–43. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(77)90179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore W. F. Observations on oligodendrocyte degeneration, the resolution of status spongiosus and remyelination in cuprizone intoxication in mice. J Neurocytol. 1972 Dec;1(4):413–426. doi: 10.1007/BF01102943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottenstein J. E., Sato G. H. Growth of a rat neuroblastoma cell line in serum-free supplemented medium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Jan;76(1):514–517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyong J. C., Witkin S. S., Rieger B., Barbarese E., Good R. A., Day N. K. Antibody-independent complement activation by myelin via the classical complement pathway. J Exp Med. 1982 Feb 1;155(2):587–598. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.2.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbarth G. S., Walsh F. S., Nirenberg M. Monoclonal antibody to a plasma membrane antigen of neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Oct;76(10):4913–4917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.10.4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ffrench-Constant C., Raff M. C. Proliferating bipotential glial progenitor cells in adult rat optic nerve. Nature. 1986 Feb 6;319(6053):499–502. doi: 10.1038/319499a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis D. A., Compston D. A., Batchelor J. R., McDonald W. I. A reassessment of the risk of multiple sclerosis developing in patients with optic neuritis after extended follow-up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987 Jun;50(6):758–765. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.50.6.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison B. M., McDonald W. I., Ochoa J. Remyelination in the central diphtheria toxin lesion. J Neurol Sci. 1972 Nov;17(3):293–302. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(72)90034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison B. M., McDonald W. I. Remyelination after transient experimental compression of the spinal cord. Ann Neurol. 1977 Jun;1(6):542–551. doi: 10.1002/ana.410010606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriss A., Francis D. A., Cuendet F., Halliday A. M., Taylor D. S., Wilson J., Keast-Butler J., Batchelor J. R., McDonald W. I. Recovery after optic neuritis in childhood. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988 Oct;51(10):1253–1258. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.10.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi G., Aloisi F., Wilkin G. P. Differentiation of cerebellar bipotential glial precursors into oligodendrocytes in primary culture: developmental profile of surface antigens and mitotic activity. J Neurosci Res. 1987;18(3):407–417. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490180305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medof M. E., Kinoshita T., Nussenzweig V. Inhibition of complement activation on the surface of cells after incorporation of decay-accelerating factor (DAF) into their membranes. J Exp Med. 1984 Nov 1;160(5):1558–1578. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.5.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D. H., Newton M. R., van der Poel J. C., du Boulay E. P., Halliday A. M., Kendall B. E., Johnson G., MacManus D. G., Moseley I. F., McDonald W. I. Magnetic resonance imaging of the optic nerve in optic neuritis. Neurology. 1988 Feb;38(2):175–179. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirsky R., Winter J., Abney E. R., Pruss R. M., Gavrilovic J., Raff M. C. Myelin-specific proteins and glycolipids in rat Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes in culture. J Cell Biol. 1980 Mar;84(3):483–494. doi: 10.1083/jcb.84.3.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan B. P., Campbell A. K., Compston D. A. Terminal component of complement (C9) in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1984 Aug 4;2(8397):251–254. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray K., Noble M. In vitro studies on the comparative sensitivities of cells of the central nervous system to diphtheria toxin. J Neurol Sci. 1985 Oct;70(3):283–293. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(85)90170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble M., Murray K. Purified astrocytes promote the in vitro division of a bipotential glial progenitor cell. EMBO J. 1984 Oct;3(10):2243–2247. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble M., Murray K., Stroobant P., Waterfield M. D., Riddle P. Platelet-derived growth factor promotes division and motility and inhibits premature differentiation of the oligodendrocyte/type-2 astrocyte progenitor cell. Nature. 1988 Jun 9;333(6173):560–562. doi: 10.1038/333560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prineas J. W., Connell F. Remyelination in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1979 Jan;5(1):22–31. doi: 10.1002/ana.410050105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raff M. C., Abney E. R., Cohen J., Lindsay R., Noble M. Two types of astrocytes in cultures of developing rat white matter: differences in morphology, surface gangliosides, and growth characteristics. J Neurosci. 1983 Jun;3(6):1289–1300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-06-01289.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raff M. C., Abney E. R., Miller R. H. Two glial cell lineages diverge prenatally in rat optic nerve. Dev Biol. 1984 Nov;106(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raff M. C., Miller R. H., Noble M. A glial progenitor cell that develops in vitro into an astrocyte or an oligodendrocyte depending on culture medium. Nature. 1983 Jun 2;303(5916):390–396. doi: 10.1038/303390a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raff M. C., Mirsky R., Fields K. L., Lisak R. P., Dorfman S. H., Silberberg D. H., Gregson N. A., Leibowitz S., Kennedy M. C. Galactocerebroside is a specific cell-surface antigenic marker for oligodendrocytes in culture. Nature. 1978 Aug 24;274(5673):813–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine C. S., Scheinberg L., Waltz J. M. Multiple sclerosis. Oligodendrocyte survival and proliferation in an active established lesion. Lab Invest. 1981 Dec;45(6):534–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranscht B., Clapshaw P. A., Price J., Noble M., Seifert W. Development of oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells studied with a monoclonal antibody against galactocerebroside. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Apr;79(8):2709–2713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.8.2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders M. E., Koski C. L., Robbins D., Shin M. L., Frank M. M., Joiner K. A. Activated terminal complement in cerebrospinal fluid in Guillain-Barré syndrome and multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 1986 Jun 15;136(12):4456–4459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scolding N. J., Houston W. A., Morgan B. P., Campbell A. K., Compston D. A. Reversible injury of cultured rat oligodendrocytes by complement. Immunology. 1989 Aug;67(4):441–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scolding N. J., Morgan B. P., Houston A., Campbell A. K., Linington C., Compston D. A. Normal rat serum cytotoxicity against syngeneic oligodendrocytes. Complement activation and attack in the absence of anti-myelin antibodies. J Neurol Sci. 1989 Feb;89(2-3):289–300. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(89)90030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scolding N. J., Morgan B. P., Houston W. A., Linington C., Campbell A. K., Compston D. A. Vesicular removal by oligodendrocytes of membrane attack complexes formed by activated complement. Nature. 1989 Jun 22;339(6226):620–622. doi: 10.1038/339620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergott R. C., Brown M. J., Silberberg D. H., Lisak R. P. Antigalactocerebroside serum demyelinates optic nerve in vivo. J Neurol Sci. 1984 Jun;64(3):297–303. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(84)90177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin M. L., Hänsch G., Hu V. W., Nicholson-Weller A. Membrane factors responsible for homologous species restriction of complement-mediated lysis: evidence for a factor other than DAF operating at the stage of C8 and C9. J Immunol. 1986 Mar 1;136(5):1777–1782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small R. K., Riddle P., Noble M. Evidence for migration of oligodendrocyte--type-2 astrocyte progenitor cells into the developing rat optic nerve. Nature. 1987 Jul 9;328(6126):155–157. doi: 10.1038/328155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer I., Schachner M. Monoclonal antibodies (O1 to O4) to oligodendrocyte cell surfaces: an immunocytological study in the central nervous system. Dev Biol. 1981 Apr 30;83(2):311–327. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90477-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschopp J., Müller-Eberhard H. J., Podack E. R. Formation of transmembrane tubules by spontaneous polymerization of the hydrophilic complement protein C9. Nature. 1982 Aug 5;298(5874):534–538. doi: 10.1038/298534a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanguri P., Shin M. L. Activation of complement by myelin: identification of C1-binding proteins of human myelin from central nervous tissue. J Neurochem. 1986 May;46(5):1535–1541. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb01773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolswijk G., Noble M. Identification of an adult-specific glial progenitor cell. Development. 1989 Feb;105(2):387–400. doi: 10.1242/dev.105.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]