Abstract

Long-term colonization of humans with Helicobacter pylori can cause the development of gastric B cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, yet little is known about the sequence of molecular steps that accompany disease progression. We used microarray analysis and laser microdissection to identify gene expression profiles characteristic and predictive of the various histopathological stages in a mouse model of the disease. The initial step in lymphoma development is marked by infiltration of reactive lymphocytes into the stomach and the launching of a mucosal immune response. Our analysis uncovered molecular markers of both of these processes, including genes coding for the immunoglobulins and the small proline-rich protein Sprr 2A. The subsequent step is characterized histologically by the antigen-driven proliferation and aggregation of B cells and the gradual appearance of lymphoepithelial lesions. In tissues of this stage, we observed increased expression of genes previously associated with malignancy, including the laminin receptor-1 and the multidrug-resistance channel MDR-1. Finally, we found that the transition to destructive lymphoepithelial lesions and malignant lymphoma is marked by an increase in transcription of a single gene encoding calgranulin A/Mrp-8.

Colonization of the human stomach by Helicobacter pylori is causally associated with gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, and two gastric malignancies, adenocarcinoma and B cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (1, 2). Direct antigenic stimulation by H. pylori results in the proliferation of lymphocytes and the formation of lymphoid follicles in the gastric mucosa, constituting the so-called MALT (3–5). Gastric MALT lymphoma is believed to arise from neoplastic B cell clones in the marginal zone of the follicle that invade the adjacent epithelium (6), a process marked histologically by the appearance of lymphoepithelial lesions (LELs). Malignant lymphomas are distinguished from precancerous MALT by the appearance of atypical centrocyte-like cells, multiple destructive LELs, and extension of the infiltrate into the submucosa (reviewed in ref. 7).

Evidence for the causal link between infection and tumor development comes from epidemiological studies showing a high prevalence of the bacterium in MALT lymphoma patients (8–10). Remarkably, eradication of the bacterium by antibiotic treatment leads to the complete regression of tumors in the majority of patients (6, 11, 12).** Consequently, antimicrobial therapy has largely replaced gastric resection as the first line of MALT lymphoma treatment (13).

The clinical and histopathological characteristics of human MALT lymphomas, including the antibiotic-induced regression of the disease, can be mimicked in BALB/c mice by long-term infection with several gastric Helicobacter species (14–16). The murine model provides a unique experimental system to study the progression of the disease from the early immune responses to fully developed malignant marginal zone lymphomas. To increase our knowledge of Helicobacter-induced lymphomagenesis, we have used murine cDNA microarrays and laser microdissection to identify molecular markers of the histopathological stages of the disease and to define the cellular origin of the transcriptional responses. We show here that the disease follows a molecular progression, and we have identified a collection of genes whose expression level is predictive of disease stage.

Methods

Mouse Infections and RNA Extraction.

Groups of specific pathogen-free BALB/c mice were infected with either Helicobacter heilmannii (a Mandrill monkey isolate), Helicobacter felis (ATCC 49179 strain CS1), or H. pylori SSI (ref. 17). Uninfected age-matched animals served as controls. The animals were killed at various time intervals after inoculation (12, 18, 20, 22, and 24 mos), one-half of the stomach was fixed in paraformaldehyde for histopathological examination, and the remainder was snap frozen at −80°C. Hematoxylin/eosin-stained sections were coded and examined blindly for the presence of lymphocytic infiltrates and LEL. These features were graded on a 0 to 3 point scale by using the following criteria. Lymphocytic infiltration: 0, no change; 1, single or few small aggregates of lymphocytes; 2, multiple multifocal large lymphoid aggregates or follicles; 3, extensive multifocal lymphocytic infiltration often extending through depth of mucosa resulting in distortion of the epithelial surface. LELs: 0, no LELs; 1, early or single LELs; 2, multiple well formed LELs, 3, multiple LELs resulting in extensive destruction of the epithelium.

RNA extractions from the remaining half of every stomach were performed by using Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Total RNA was then further purified by using Qiagen (Chatsworth, CA) RNeasy kits.

RNA Labeling and Hybridization.

Detailed protocols for probe synthesis and DNA microarray hybridization are given at http://cmgm.stanford.edu/pbrown/protocols/index.html. In short, 40 μg of total RNA was used for single-stranded cDNA probe synthesis incorporating aminoallyl-dUTP, which was subsequently coupled with either Cy3 (for the reference sample) or Cy5 (for the experimental sample). Experimental and references samples were combined and hybridized at 65°C in 3.4× SSC and 0.3% SDS to a 38,000-element spotted mouse cDNA microarray. The reference for all arrays used in this study consisted of pooled cDNA extracted from stomachs of age-matched uninfected control animals (10 animals per time point).

Laser Microdissection and RNA Amplification.

Ten-micrometer cryosections of mouse stomachs were mounted on polyester membrane slides (Leica, Deerfield, IL) and a quick staining was performed: after fixation in 75% ethanol for 30 s, the slides were dipped in distilled water and stained for 1 min with Histogene staining solution (Arcturus, Mountain View, CA). The slides were washed in distilled water, dehydrated for 30 s in 75%, 95%, and 100% ethanol, respectively, and dried at room temperature. Mucosal tissue and lymphocytic aggregates were isolated by laser microdissection with a Leica AS laser microdissection system. Total RNA was isolated with the Picopure kit (Arcturus) and amplified by two rounds of T7-based linear amplification with the Riboamp kit (Arcturus) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Data Analysis.

Arrays were scanned by using a GenePix 4000A scanner and images analyzed with genepix pro software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Microarray data were stored in the Stanford Microarray Database (18). Data were filtered with respect to spot quality (spots with regression correlations <0.6 were omitted) and data distribution (genes whose log2 of red/green normalized ratio is more than two standard deviations away from the mean in at least three arrays were selected) before clustering. Only genes for which information was available for more than 80% of arrays were included. Data were log2 transformed and analyzed by using cluster and treeview (19). Statistical analysis was done by using the significance analysis of microarrays algorithm (SAM, ref. 20). Data from all of the arrays used in this paper are available at http://genome-www4.stanford.edu/MicroArray/SMD/.

Results and Discussion

To identify the most virulent Helicobacter species in the mouse, groups of BALB/c mice were infected for up to 24 mos with either H. pylori, H. felis, or H. heilmannii, the latter also being associated with MALT lymphoma in humans (21). Their stomachs were examined histopathologically (Fig. 1). Although the lesions (Fig. 1A) induced by the three species were indistinguishable qualitatively, H. heilmannii triggered the most severe response in the highest proportion of infected animals (Fig. 1B). On the basis of this result, we decided to follow disease progression in H. heilmannii-infected mice and chose the time points 12, 18, and 24 mos postinfection for further analysis. Total RNA was extracted from the stomachs of infected animals and of a cohort of age-matched uninfected control animals. The corresponding cDNA was labeled with the fluorescent dye Cy5, mixed with Cy3-labeled reference sample, and hybridized to a spotted 38,000-element murine cDNA microarray that contains features derived from the RIKEN (22) and NIA (23) mouse clone sets.

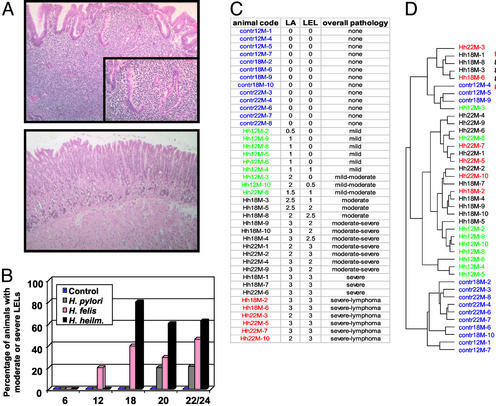

Figure 1.

Histopathological and CLUSTER analysis of BALB/c mice infected with Helicobacter. (A and B) Mice were infected up to 24 mos with H. pylori, H. felis, or H. heilmannii. One-half of each stomach was fixed, stained with hematoxylin/eosin, and examined for the presence of LELs. (A) Cross section of a H. heilmannii-infected stomach (Upper) displaying marked lymphocytic infiltration (dark-blue staining) and partial destruction of gastric gland epithelium (Inset). (Lower) Cross section of an age-matched uninfected stomach. (B) Virulence comparison of the three Helicobacter species. Infected stomachs were graded on a 0–3 scale, as described in Methods. The percentage of animals with moderate (grade 2) or severe (grade 3) pathology is indicated. Note: at ≈18 mos postinfection (p.i.), the majority of animals show severe signs of illness, and thus group sizes dwindle due to infection-induced and age-related deaths (only 80% of uninfected and 50–70% of infected animals survive for 24 mo, depending on the infecting Helicobacter species). This finding explains the increased percentage of animals with severe LELs at 18 mos p.i. compared with the later time points. (C) Overview of the pathology observed in all 41 animals used in this study. Thirteen control (uninfected) animals and 28 H. heilmannii-infected animals (contr and Hh) from three different time points [12, 18, and 22 mos (12M, 18M, 22M)] were classified on a 0–3 scale with respect to the presence of lymphocytic infiltration and LELs, as described in Methods. An overall pathology classification was assigned to every animal on the basis of these grades. The animals were assembled into four groups, as indicated by the color coding. Animals with mild pathology are depicted in green; animals with moderate and severe pathology are depicted in black; and animals with a lymphoma diagnosis are depicted in red. Control animals are shown in blue. The color code is maintained throughout the paper. (D) The dendrogram reveals the relatedness of the gene expression profiles of the mice as determined by CLUSTER analysis. The data were filtered with respect to spot quality and data distribution before clustering.

A hierarchical clustering algorithm was used to group genes and experimental samples in an “unsupervised” fashion on the basis of similarities of gene expression (19). The relationships between the experimental samples are summarized in a dendrogram (Fig. 1D). The resulting clusters were subsequently compared with the stomach pathology of the corresponding mice (Fig. 1C), which was histologically classified on a 0–3 scale. All but three control samples (blue) cluster separately from the infected specimens and form a distinct branch of the dendrogram (Fig. 1D). Infected samples displaying mild pathology (green) segregate from moderate or severe pathology samples (black and red), with two exceptions. In contrast, the specimens histologically classified as lymphomas due to the presence of groups of centrocyte-like cells invading the epithelium (red) failed to form a distinct cluster but were interspersed among the other moderate and severe pathology samples. The differences in gene expression between samples with severe lymphoid hyperplasia and those with true malignancy are therefore not sufficient to drive the clustering. This finding argues against one definitive transforming event and in favor of a continuum of which malignant lymphomas represent the end point.

Because the hierarchical clustering segregated uninfected from infected samples, we sought to identify genes whose expression was characteristic and predictive of infection. We used a strategy referred to as “supervised clustering” (24), which allowed us to identify a limited set of “signature genes” for the different stages of pathology. A two-group unpaired t test was performed on the log2 red/green normalized ratios of infected vs. uninfected samples, and the 250 most differentially expressed genes (P values <0.001) were selected and subjected to hierarchical clustering. This procedure revealed clusters of genes that were up- or down-regulated specifically in the infected group (overview in Fig. 2A). The gene cluster in Fig. 2B shows the genes up-regulated in the infected stomachs, and selected genes are designated (complete gene clusters are published as Fig. 5).

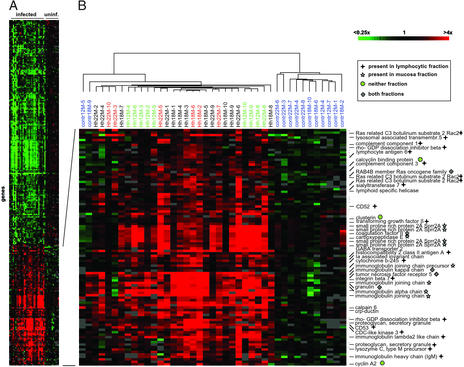

Figure 2.

Molecular signature of Helicobacter-infected murine stomachs. (A) Overview of all 250 genes that are differentially regulated in the infected vs. the uninfected animals and have P values <0.001. Data are a measure of relative gene expression and represent the quotient of the hybridization of the fluorescent cDNA probe prepared from each stomach sample compared with its reference pool. Red and green represent high and low experimental sample/reference ratios, respectively (see scale bar). Gray signifies technically inadequate or missing data. Rows represent genes, and columns represent arrays. An enlarged section of the overview is shown in B. The color coding of array names is described in Fig. 1C. Selected genes are designated. The symbols next to the gene names specify the laser microdissection fraction (as indicated in the legend) containing the respective transcript. See Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org, for the complete cluster.

The up-regulated genes fall into two major groups: first, there are typical lymphocyte signature genes such as those coding for the Ig genes, the tetraspanin family member CD53, TNF receptor 5 (also called CD40, a marker for mature B cells), and integrin β7, a component of the mucosal homing receptor of B cells. Up-regulation of these genes confirms the presence of lymphocytes in the lesions (reviewed in ref. 25). The up-regulation of several genes encoding components of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is of interest because MHC class II molecules reportedly mediate H. pylori binding to target cells (26). Another lymphocyte surface molecule in this cluster, CD52, is the target of CAMPATH-1H, an antibody of increasing clinical importance in the treatment of lymphoproliferative disorders (reviewed in ref. 27). The other major group consists of several factors with putative functions in fortifying the epithelial barrier of the gastrointestinal tract against invasion of microorganisms. For example, the most pronounced up-regulation was seen with the gene encoding the small proline-rich protein 2A (Sprr2A), which was identified recently as the most highly induced gene in a study investigating the molecular response of a germ-free mouse gut to Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron colonization (28). Other proteins with epithelial barrier functions that are up-regulated in Helicobacter-infected mice are CRP-ductin along with its ligands, the trefoil peptides. The two groups of genes reflect the immune response mounted by the infected host, which, in the case of Helicobacter, fails to clear the infection (reviewed in ref. 29).

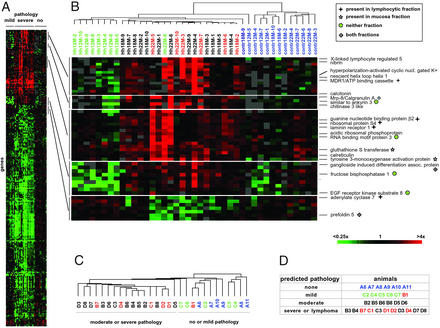

Having determined the signature of infected vs. uninfected stomachs, we next sought to identify genes that discriminate between mild and moderate to severe pathology. Mice that were uninfected and/or exhibited mild pathology were grouped together and compared with animals with moderate and severe pathology. The 300 most differentially expressed genes (P < 0.001) allowed the complete segregation of the three major pathology groups into three distinct arms of the dendrogram (overview in Fig. 3A), with only three exceptions. Several representative gene clusters are shown in Fig. 3B and selected genes are designated (the complete gene clusters can be found in Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). A number of genes up-regulated consistently in the severe pathology specimens are associated with human malignancies and can therefore be tentatively assembled into a functional group. One example is the gene encoding the laminin receptor-1, a protein found to be overexpressed on tumor cell surfaces of a variety of cancers (30) and implicated in basement membrane degradation and tumor dissemination. Another interesting gene included in this group encodes MDR-1, a protein causally linked to the multidrug resistance of tumors by acting as an efflux pump of chemotherapeutic agents (31). The DNA double-strand repair protein nibrin has previously been shown to be overexpressed in a high proportion of gastric carcinomas (32). Its up-regulation in mice with severe pathology is particularly interesting in light of the finding that H. pylori has been shown to cause DNA fragmentation when cocultured with gastric epithelial cells (33). Moreover, the chitinase-3 like protein, also known as human cartilage glycoprotein 39, has been shown to stimulate proliferation in human connective tissue cells and can therefore be classified as a mitogen (34).

Figure 3.

Molecular signature of the histologically distinct stages of Helicobacter-induced lymphoproliferative disease. (A) Overview of all 300 genes that are differentially regulated in the mild pathology vs. the moderate and severe pathology cohorts of infected animals and have P values <0.001. Five enlarged sections are shown in B. Selected genes are designated and the color coding of array names is as described in Fig. 1C. The symbols next to the gene names specify the laser capture fraction (as indicated in the legend) containing the respective transcript. See Fig. 6 for the complete cluster. (C and D) Predictive power of the signature gene lists shown in Fig. 2 and A and B. Gene expression profiles were generated for an additional set of 29 animals. Arrays were clustered by using the 250 and 300 genes constituting the signature gene lists. The dendrogram in C reflects the relatedness of all 29 specimens when the 300 gene list distinguishing mild from moderate and severe pathology is used for clustering. The color coding of arrays is described in Fig. 1C. (D) Comparison of the pathology predictions that were made on the basis of gene and array clustering shown in C and Fig. 7, with the results of the histopathological classification of the stomachs (as indicated by the color coding). Only animal B1 was placed in the wrong pathology group.

The described statistical approach allowed us to delineate gene expression changes accompanying the transition from uninfected to infected and mild to severe pathology, respectively. To test the usefulness of the two signature gene lists for predicting the pathology of as-yet-unclassified samples, an independent study on a separate set of 29 animals was conducted in a blinded fashion (Fig. 3 C and D). RNA was extracted and hybridizations were performed for this “test set” of mice exactly as described for the “training set.” Hierarchical clustering was then performed by using only the 250 and 300 genes, respectively, of the two signature gene lists (Fig. 3C; Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), and pathology predictions were made based on the resulting gene and array clustering patterns (Fig. 3D). A comparison of these predictions with the independently derived pathology data for each animal (as symbolized by the color coding in Fig. 3D) revealed only one completely false classification (animal B1) of 29 (3.4%). As suggested earlier by the unsupervised clustering performed on the training set (Fig. 1D), the gene lists do not allow for discrimination between severe premalignant pathology and malignant lymphoma, implying that the transcriptional changes between these histologically defined grades of pathology are subtle or follow along a continuum. Alternatively, the lack of distinguishing gene expression between these two groups could indicate that the classification by histology (which is currently considered the standard for MALT lymphoma diagnosis) may actually be artifactual.

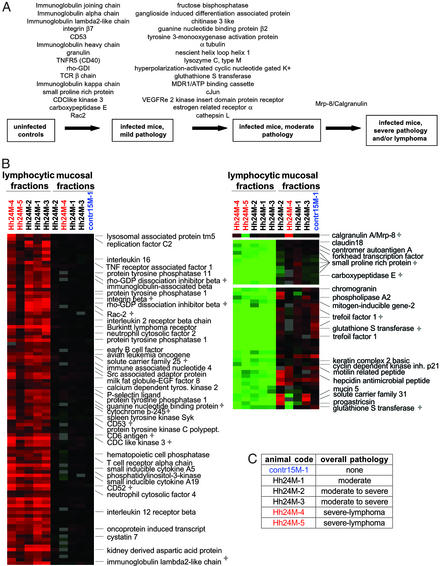

As an independent method to identify genes characteristic of distinct histopathological disease stages, we used the SAM algorithm (20). SAM is based on the t test but additionally performs permutations of the data to account for the multiple comparisons typically complicating the statistical analysis of microarray data. Pairwise SAM was run on groups of increasing pathology (using a comparable false-positive discovery rate of under 5% for all three comparisons), and genes that differ significantly between pairs are listed in Fig. 4A. One major conclusion could be drawn using this approach. It is apparent from the diagram shown in Fig. 4A that the vast majority of gene expression changes occur in the two earlier stages of the disease; they reflect the initial marked infiltration of immune cells into the gastric mucosa and the later expansion into the epithelium, respectively. In contrast, we find that the last step leading to malignant transformation of the B cells and the associated destructive LELs (only those histologically classified as grade 3) is accompanied by a significant change in expression of only a single gene encoding Mrp-8/calgranulin.

Figure 4.

(A) The diagram depicts the result of the SAM algorithm applied pairwise to cohorts of mice grouped according to their pathology (as indicated in the squares). The 15 most significantly differing genes are listed, and the gene order reflects the significance score assigned by SAM (highest scores at the top). (B) The cellular origin of selected transcripts. Frozen tissue sections cut from stomachs of six animals were stained and subjected to laser microdissection. Both lymphocytic and mucosal fractions were isolated from each stomach with two exceptions: only the mucosal fraction could be harvested from the uninfected stomach contr15M-1, because it did not display lymphocytic aggregation. In the case of stomach Hh24M-5, the mucosa was so severely destroyed and interspersed with large aggregates of lymphocytes that no contamination-free mucosal fraction could be obtained. The gene expression data were filtered with respect to spot quality (spots with regression correlations <0.6 were omitted) and data values (genes whose log2 of red/green normalized ratio is more than two in at least four arrays were selected) before clustering. Only genes for which information was available for >80% of arrays were included. Two representative clusters are shown: (Left) Genes present in the lymphocytic fractions (“lymphocyte signature”); (Right) mucosal genes (“mucosal signature”). The gene expression pattern for calgranulin/Mrp-8 is shown separately, because it did not fall into either cluster. Genes of interest are designated, and those genes that were also identified in the whole-stomach screen are marked with an asterisk. The overall pathology of all six animals is listed in C.

Both calgranulin A and its close relative, calgranulin B, have recently been found in a screen for phorbolester-induced genes (35, 36), thereby linking these proteins to skin carcinogenesis. Their expression appears to be negatively regulated by c-Fos/AP-1 and transcripts localize to neutrophils and monocytes infiltrating the inflamed skin section (36). The calgranulins are believed to function mainly in the extracellular space (reviewed in ref. 37), where they display potent antimicrobial activity, trigger the transendothelial migration of leukocytes, and induce local inflammation. The function of the calgranulins in the transition from lymphoid hyperplasia to lymphoma remains to be elucidated.

To determine whether the observed changes in gene expression occur in the mucosa itself or in the lymphocytic fraction of infected stomachs, we isolated the respective tissues by laser microdissection. Frozen sections of six stomachs (one uninfected and five infected; see Fig. 4C for histopathology data on these animals) were stained by using an abbreviated protocol that minimizes RNA degradation. Lymphocytic aggregates were easily detected by their characteristic size and the shape of their nuclei and could be captured virtually free of contaminating mucosa (for micrographs of the tissue sections before and after laser dissection, see Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The mucosal fraction was harvested in addition. RNA was extracted and amplified in two rounds by using a T7 RNA polymerase-based protocol (38) before labeling and hybridization. The reference RNA was extracted from pooled age-matched control stomachs and amplified accordingly.

Fig. 4B shows gene clusters representing parts of the lymphocytic and mucosal signatures (Left and Right), respectively (complete clusters can be found in Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Genes that were also identified in the whole stomach screen are marked with an asterisk. Although the majority of genes up-regulated in the lymphocyte fractions (Fig. 4B Left) seem to be of B cell origin (specific examples being the tyrosine kinases Btk and Syk or the Ig heavy chain), some typical T cell markers such as the T cell receptor α and β chains, Zap70, Lnk, the transcription factor NFATc1, and others (Fig. 4B and supporting information on the PNAS web site) could also be detected, thus confirming previous observations of T cells in murine MALT tissue (14). Earlier reports have suggested that the CD4+ population of T cells in human MALT tissue is Helicobacter specific and sustains an actively proliferating B cell population by indirect stimulation (25). Several genes found in the lymphocytic fraction point to the presence of neutrophils in the lymphoid tissue of infected stomachs (e.g., neutrophil cytosolic factors 2 and 4). The neutrophilic response to Helicobacter infection, which is characterized by the release of potentially DNA damaging reactive oxygen species, is believed to promote the acquisition of genetic abnormalities and malignant transformation of reactive B cells (25).

Among the most prevalent functional groups of genes in the lymphocyte fraction are signaling molecules such as kinases (e.g., the tyrosine kinases Syk, Btk, Jak3, Lck, and Csk), phosphatases (nonreceptor type protein tyrosine phosphatases 1 and 11, hematopoietic cell phosphatase Hcph), small G proteins (Rac2, Rab4b, Rab11b), and cytokines, as well as their receptors (IL2 receptor β and γ chains; IL3 receptor α chain; IL7 receptor; IL12 receptor β chain; IL16; small inducible cytokines 13, A5, A19, and A21b; and chemokine receptor 4). Several lymphoma/leukemia related factors are also found to be expressed in the lymphocytic fraction: examples include the Burkitt lymphoma receptor, Bcl2-A1a, Bcl2-A1d, and Bcl6. Bcl2-A1a is of particular interest in this subgroup, because it is most highly expressed in the two lymphoma samples Hh24M-4 and -5 (not shown).

Among the genes up-regulated in the mucosal fractions (Fig. 4B Right) are several that have proposed functions in the mucosal defense against damage caused by invading pathogens. The small proline-rich protein was identified in whole-stomach profiles (Fig. 2B) and can clearly be attributed to this functional group (28). The trefoil factor 1 functions as a ligand for CRP-ductin and is believed to protect the gastrointestinal epithelium from apoptosis. Another gene involved in fortifying the epithelium is hepcidin, a short cysteine-rich peptide displaying potent antimicrobial activity (39).

Because Mrp-8/calgranulin was identified as the only marker for severe pathology and lymphomas, its cellular origin was of particular interest. We found the transcript expressed in both the mucosal and the lymphocytic fraction, although it is relatively more abundant in the former tissue (Fig. 4B Left). Because calgranulin mainly functions extracellularly (37), investigating the localization of the corresponding protein will be useful in shedding light on its function in MALT lymphoma development.

Using expression profiles generated from microdissected tissues, every gene found to be up-regulated in the whole stomach screen (Figs. 2B and 3B) was reexamined with regard to its cellular localization. Symbols representing the lymphocytic and mucosal fractions have been added to the genes shown in the respective clusters to illustrate the likely cellular origin of these transcripts.

In an attempt to validate the laser microdissection approach by another method, the cellular distribution of a protein encoded by a transcript found in the lymphocytic fraction was confirmed by immunohistochemistry on paraffin sections. The Rac-2 protein was chosen because of its consistent and strong up-regulation early on during lymphocytic infiltration of the stomach (Fig. 2B). It is a small G protein and has been implicated in cell motility and consequently cellular functions depending on cell motility, such as neutrophil chemotaxis. This experiment confirmed that B cells in the lymphoid aggregate indeed express Rac-2, as suggested by the laser microdissection results (see Fig. 10, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

In summary, the studies described above demonstrate that Helicobacter-induced lymphoma develops through a series of molecularly distinct stages. The transcripts that characterize particular histopathological stages were shown to be useful in predicting the pathology of previously unclassified specimens. In contrast to similar studies performed on biopsies of other human malignancies, which usually represent the end stage of the disease, our lymphoma model provides a unique opportunity for monitoring the progression of events over time. The murine model for MALT lymphoma is particularly useful, because it is one of the few animal tumor models that faithfully reproduce almost all of the histological features of the human malignancy.

A comparison of the findings of the murine model with gene expression profiles of human MALT lymphoma biopsies may further support the model. The human counterpart of calgranulin A will be of particular interest in this respect, because it might prove to be of predictive value for the late stages of Helicobacter-induced lymphoproliferative disease. This and the molecular analysis of other interesting features of the murine model system, such as the remission of the tumor after antimicrobial therapy, may lead to a better understanding of how a bacterial agent can cause a human malignancy and which transcriptional changes accompany its regression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Falkow laboratory as well as Pat Brown, Ronald Levy, and Stephen Popper for helpful discussions and suggestions. We are indebted to the staff of the Stanford Functional Genomics Facility for providing high-quality mouse arrays and to the Stanford Microarray Database for help with DNA microarray experiments. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI38459 and CA92229 (to S.F.). A.M. received an Otto Hahn Fellowship from the Max Planck Society and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant MU1675/1-1. We acknowledge support from the Cancer Research Fund of the Damon Runyon–Walter Winchell Foundation (Fellowship DRG-1509 to K.G.). K.G. is a recipient of a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award in the Biomedical Sciences. J.O. is funded by National Health and Medical Research Council Grant 9936694.

Abbreviations

- MALT

mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

- LEL

lymphoepithelial lesion

- SAM

significance analysis of microarrays

Footnotes

This finding could suggest that MALT lymphomas are not true malignancies. On the basis of the fact that these tumors show uncontrolled growth as well as a (low) tendency to local and systemic dissemination (reviewed in ref. 7) and the disease is potentially lethal if left untreated, we will use the term “malignancy” here for both the human disease and the parallel disease described in the murine model.

References

- 1.Parsonnet J, Friedman G D, Vandersteen D P, Chang Y, Vogelman J H, Orentreich N, Sibley R K. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaser M J. Br Med J. 1998;316:1507–1510. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7143.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wyatt J I, Rathbone B J. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1988;142:44–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stolte M, Eidt S. J Clin Pathol. 1989;42:1269–1271. doi: 10.1136/jcp.42.12.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Genta R M, Hamner H W, Graham D Y. Hum Pathol. 1993;24:577–583. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isaacson P G. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:637–645. doi: 10.1023/a:1008396618983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavalli F, Isaacson P G, Gascoyne R, Zucca E. Hematology. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program; 2001. pp. 241–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wotherspoon A C, Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Falzon M R, Isaacson P G. Lancet. 1991;228:1175–1176. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eidt S, Stolte M, Fischer R. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:436–439. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.5.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura S, Yao T, Aoyagi K, Iida M, Fujishima M, Tsuneyoshi M. Cancer. 1997;97:3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wotherspoon A C, Doglioni C, Diss T C, Pan L, Moschini A, de Boni M, Isaacson P G. Lancet. 1993;342:575–577. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91409-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wotherspoon A C. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:289–299. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peura D. Am J Med. 1998;105:424–430. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enno A, O'Rourke J L, Howlett C R, Jack A, Dixon M F, Lee A. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:217–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enno A, O'Rourke J, Braye S, Howlett R, Lee A. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1625–1632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee A, O'Rourke J, Enno A. Rec Res Cancer Res. 2000;156:42–51. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-57054-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee A, O'Rourke J, De Ungria M C, Robertson B, Daskalopoulos G, Dixon M F. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1386–1397. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherlock G, Hernandez-Boussard T, Kasarskis A, Binkley G, Matese J C, Dwight S S, Kaloper M, Weng S, Jin H, Ball C A, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:152–155. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisen M B, Spellman P T, Brown P O, Botstein D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tusher V G, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stolte M, Kroher G, Meining A, Morgner A, Bayerdorffer E, Bethke B. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:28–33. doi: 10.3109/00365529709025059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miki R, Kadota K, Bono H, Mizuno Y, Tomaru Y, Carninci P, Itoh M, Shibata K, Kawai J, Konno H, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2199–2204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041605498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka T S, Jaradat S A, Lim M K, Kargul G J, Wang X, Grahovac M J, Pantano S, Sano Y, Piao Y, Nagaraja R, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9127–9132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raychaudhuri S, Sutphin P D, Chang J T, Altman R B. Trends Biotechnol. 2001;19:189–193. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(01)01599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Du M Q, Isaccson P G. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00651-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan X, Crowe S E, Behar S, Gunasena H, Ye G, Haeberle H, Van Houten N, Gourley W K, Ernst P B, Reyes V E. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1659–1669. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.10.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pangalis G A, Dimopoulou M N, Angelopoulou M K, Tsekouras C, Vassilakopoulos T P, Vaiopoulos G, Siakantaris M P. Med Oncol. 2001;18:99–107. doi: 10.1385/mo:18:2:99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hooper L V, Wong M H, Thelin A, Hansson L, Falk P G, Gordon J I. Science. 2001;291:881–884. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5505.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ernst P B, Takaishi H, Crowe S E. Dig Dis. 2001;19:104–111. doi: 10.1159/000050663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menard S, Tagliabue E, Colnaghi M I. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;52:137–145. doi: 10.1023/a:1006171403765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnstone R W, Ruefli A A, Smyth M J. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01493-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsutani N, Yokozaki H, Tahara E, Tahara H, Kuniyasu H, Kitadai Y, Haruma K, Chayama K, Tahara E, Yasui W. Pathobiology. 2001;69:219–224. doi: 10.1159/000055946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Obst B, Wagner S, Sewing K F, Beil W. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1111–1115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Recklies A D, White C, Ling H. Biochem J. 2002;365:119–126. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breitenbach U, Tuckermann J P, Gebhardt C, Richter K H, Furstenberger G, Christofori G, Angel P. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:634–640. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gebhardt C, Breitenbach U, Tuckermann J P, Dittrich B T, Richter K H, Angel P. Oncogene. 2002;21:4266–4276. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donato R. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:637–668. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Gelder R N, von Zastrow M E, Yool A, Dement W C, Barchas J D, Eberwine J H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1663–1667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park C H, Valore E V, Waring A J, Ganz T. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7806–7810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.