Abstract

Calcium (Ca2+) is a versatile second messenger that regulates a wide range of cellular functions. Although it is not established how a single second messenger coordinates diverse effects within a cell, there is increasing evidence that the spatial patterns of Ca2+ signals may determine their specificity. Ca2+ signaling patterns can vary in different regions of the cell and Ca2+ signals in nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments have been reported to occur independently. No general paradigm has been established yet to explain whether, how, or when Ca2+ signals are initiated within the nucleus or their function. Here we highlight that receptor tyrosine kinases rapidly translocate to the nucleus. Ca2+ signals that are induced by growth factors result from phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate hydrolysis and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate formation within the nucleus rather than within the cytoplasm. This novel signaling mechanism may be responsible for growth factor effects on cell proliferation.

Keywords: Calcium, Proliferation, Receptor tyrosine kinases, Nucleus

Introduction

Intracellular Ca2+ can regulate cellular processes as distinct as cell death and proliferation (1). To achieve this versatility, there is increasing evidence that the spatial patterns of Ca2+ signals may determine their specificity (2). Ca2+ signals in nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments occur independently in several different cell types (3). However, the mechanisms and pathways that promote localized increases of free Ca2+ levels in the nucleus have not been entirely defined.

Recently, ligand-dependent translocation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) to the nucleus has been reported (4–7). RTKs can activate phospholipase C (PLC) that hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), generating two intracellular products: inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3), a universal Ca2+-mobilizing second messenger, and diacylglycerol, an activator of protein kinase C (PKC) (8,9). It has also been reported that the interior of the nucleus has all the Ca2+ signaling machinery necessary to produce nuclear Ca2+ signaling (10–15). The translocation of RTK to the nucleus indicates a new mechanism by which RTK increases Ca2+ in the nucleus and a new paradigm to explain the mechanism and pathways that promote nuclear Ca2+ signaling. This review highlights the recent advances in this area.

The nucleus contains the machinery needed to locally increase Ca2+

PLC hydrolyzes PIP2 to generate InsP3 (16), and InsP3 then binds to the InsP3 receptor (InsP3R) to release Ca2+ from internal stores. It is well established that components necessary for InsP3-mediated Ca2+ signaling are present in the plasma membrane and the endoplasmic reticulum, and there is evidence that these components are also present in the nuclear envelope as well. These components include PIP kinase (PIPK) (17,18), which synthesizes PIP2, plus PLC (19) and the InsP3R (20–22). InsP3R is found on both the cytoplasmic and the intranuclear side of the nuclear membrane (11,23), and the nuclear envelope contains sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) pumps for Ca2+ reuptake as well (24). The nucleus, therefore, is equipped to produce InsP3 and to release and take up free Ca2+, independent of cytosolic InsP3 or Ca2+. Although Ca2+ can spread passively from the cytosol into the nucleus under certain circumstances (25–27), intranuclear InsP3 can increase Ca2+ directly within the nucleus as well, both in isolated nuclei (12,20,28) and in nuclei within intact cells (23,29,30). Moreover, RTKs may selectively activate nuclear isoforms of PLC (18,31). However, until recently it was not known whether such receptors use this mechanism to increase Ca2+ in the nucleus. Two additional details about nuclear Ca2+ signaling have recently been established. First, the relative distribution of InsP3R isoforms in the nucleus and cytosol can differ among cell types (21). Because each InsP3R isoform has distinct sensitivities to InsP3 (32) and to Ca2+ (33,34), this differential distribution provides a mechanism by which the nucleus may be more sensitive than the cytosol to InsP3-mediated Ca2+ release in certain cell types (21). Second, InsP3-gated Ca2+ stores are found not only within the nuclear envelope, but also along a nucleoplasmic reticulum (23). PIPK and PIP2 are present in the interior of the nucleus (14), and insulin and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) can induce InsP3 production in nuclei (6,7,35). These findings suggest that Ca2+ signaling machinery is present not only along the nuclear envelope but within the interior of the nucleus as well, which may provide an additional level of spatial control of nuclear Ca2+ signaling. In fact, Ca2+ signals induced by HGF and insulin begin in the nucleus (6,7); nuclear Ca2+ signals are initiated in both SKHep-1 cells and primary hepatocytes when PIP2 is hydrolyzed to form InsP3 (6,7). Moreover, both the HGF receptor (c-met) and insulin receptor translocate to the nucleus (Figure 1). Translocation of the HGF receptor to the nucleus depends upon the adaptor protein Gab1, that contains a nuclear localization sequence and importin-β1, and the formation of Ca2+ signals depends upon this translocation (6). Transport of proteins through the nuclear pore complex typically involves importins α/β and exportins. Specifically, importin-β binds to the classical lysine-rich nuclear localization signal in the cargo, and importin-β interacts with the importin-β/cargo complex to guide it through the nuclear pore (6). Together, these data indicate that RTKs can activate the calcium signaling machinery within the nucleus.

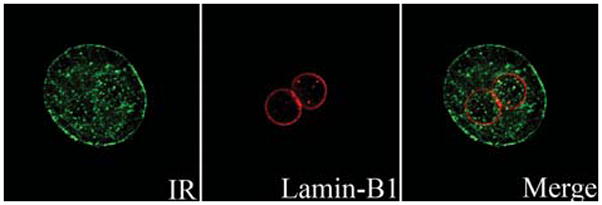

Figure 1.

The insulin receptor translocates to the nucleus. Confocal immunofluorescence images of the insulin receptor (IR) after 5-min stimulation with insulin (10 nM). Isolated rat hepatocytes were double-labeled with a polyclonal antibody against insulin receptor B (BD Biosciences, USA) and a monoclonal antibody against the nuclear membrane marker Lamin-B1 (Abcam, USA) and then incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa 488 and 555 (Invitrogen, USA), respectively. Images were collected with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope using a 63X, 1.4-NA objective lens with excitation at 488 nm and observation at 505–550 nm to detect Alexa 488 (green), and excitation at 543 nm and observation at 560–610 nm to detect Alexa 555 (red).

Increases in Ca2+ within the nucleus have specific cellular effects

Nuclear Ca2+ signaling directly regulates cellular functions such as activation of kinases within the nucleus (23,36), protein transport across the nuclear envelope (11,37), and transcription of certain genes (38–40). For example, nuclear Ca2+ activates calmodulin kinase IV (36) and induces translocation of intranuclear but not cytosolic PKC (23). Gene transcription mediated by either the cAMP response element (CRE), CRE binding protein (CREB), or CREB binding protein (CBP) specifically depends upon increases in nuclear Ca2+, whereas gene transcription mediated by the serum response element instead is mediated by increases in cytoplasmic Ca2+ (38,39). Transcriptional activation of Elk-1 by epidermal growth factor also depends upon nuclear rather than cytosolic Ca2+ (40). Moreover, Ca2+ can bind to and directly regulate certain nuclear transcription factors (41), and can affect DNA structure as well (42). Nuclear Ca2+ can negatively regulate the activity of transcription factors as well (43). This was demonstrated by examining the relative effects of nuclear and cytosolic Ca2+ on the activity of the transcription enhancer factor TEF/TEAD. Chelation of nuclear but not cytosolic Ca2+ increased TEAD activity to twice that of controls, providing evidence that nuclear Ca2+ negatively regulates the activity of this transcription factor. Collectively, these findings show that nuclear Ca2+ regulates the expression of certain genes. Exogenous expression of the Ca2+ buffering protein parvalbumin has shown that intracellular Ca2+ regulates cell growth (44), but lack of effective experimental tools has made it difficult to demonstrate whether the effect of Ca2+ on cell growth is due to nuclear or cytosolic Ca2+ signals. Initial functional studies of nuclear Ca2+ on gene transcription relied on microinjection of Ca2+ chelators into either the nucleus or cytosol of individual cells (39), but it is impractical to use this labor-intensive approach to conduct biochemical, cell population, or in vivo studies. However, a newer approach has been developed in which cells are infected with adenovirus to deliver Ca2+ chelators such as parvalbumin that are targeted to be expressed in either the nucleus or cytosol (45). Nuclear Ca2+ stimulates cell proliferation rather than apoptosis and specifically permits cells to advance through early prophase (45). Furthermore, nuclear Ca2+ regulates cell proliferation in multiple cell lines and in vivo (45).

Conclusions and future directions

The current evidence suggests that nucleoplasmic Ca2+ regulates cell cycle progression. RTKs move to the nucleus to generate InsP3 and therefore Ca2+ signals within the nucleus, and this nuclear Ca2+ signaling is important for cell proliferation. Further work is needed to identify the mechanism by which RTKs move to the nucleus and how nucleoplasmic Ca2+ control the pathways involved in cell cycle progression.

Acknowledgments

Research supported by NIH (#DK57751, #DK34989, and #DK45710), and by CNPq, FAPEMIG, and Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Presented at the IV Miguel R. Covian Symposium, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil, May 23–25, 2008.

References

- 1.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Lipp P. Calcium - a life and death signal. Nature. 1998;395:645–648. doi: 10.1038/27094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bootman MD, Thomas D, Tovey SC, Berridge MJ, Lipp P. Nuclear calcium signalling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:371–378. doi: 10.1007/PL00000699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sardi SP, Murtie J, Koirala S, Patten BA, Corfas G. Presenilin-dependent ErbB4 nuclear signaling regulates the timing of astrogenesis in the developing brain. Cell. 2006;127:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo HW, Ali-Seyed M, Wu Y, Bartholomeusz G, Hsu SC, Hung MC. Nuclear-cytoplasmic transport of EGFR involves receptor endocytosis, importin beta1 and CRM1. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:1570–1583. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomes DA, Rodrigues MA, Leite MF, Gomez MV, Varnai P, Balla T, et al. c-Met must translocate to the nucleus to initiate calcium signals. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4344–4351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706550200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodrigues MA, Gomes DA, Andrade VA, Leite MF, Nathanson MH. Insulin induces calcium signals in the nucleus of rat hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2008 doi: 10.1002/hep.22424. (ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponzetto C, Bardelli A, Zhen Z, Maina F, dalla Zonca P, Giordano S, et al. A multifunctional docking site mediates signaling and transformation by the hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor receptor family. Cell. 1994;77:261–271. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eichhorn J, Kayali AG, Austin DA, Webster NJ. Insulin activates phospholipase C-gamma1 via a PI-3 kinase dependent mechanism in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:615–620. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irvine RF. Nuclear lipid signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:349–360. doi: 10.1038/nrm1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stehno-Bittel L, Luckhoff A, Clapham DE. Calcium release from the nucleus by InsP3 receptor channels. Neuron. 1995;14:163–167. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stehno-Bittel L, Perez-Terzic C, Clapham DE. Diffusion across the nuclear envelope inhibited by depletion of the nuclear Ca2+ store. Science. 1995;270:1835–1838. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malviya AN. The nuclear inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate receptors. Cell Calcium. 1994;16:301–313. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(94)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boronenkov IV, Loijens JC, Umeda M, Anderson RA. Phosphoinositide signaling pathways in nuclei are associated with nuclear speckles containing pre-mRNA processing factors. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:3547–3560. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cocco L, Martelli AM, Vitale M, Falconi M, Barnabei O, Stewart GR, et al. Inositides in the nucleus: regulation of nuclear PI-PLCbeta1. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2002;42:181–193. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(01)00030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cocco L, Gilmour RS, Ognibene A, Letcher AJ, Manzoli FA, Irvine RF. Synthesis of polyphosphoinositides in nuclei of Friend cells. Evidence for polyphosphoinositide metabolism inside the nucleus which changes with cell differentiation. Biochem J. 1987;248:765–770. doi: 10.1042/bj2480765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Divecha N, Banfic H, Irvine RF. The polyphosphoinositide cycle exists in the nuclei of Swiss 3T3 cells under the control of a receptor (for IGF-I) in the plasma membrane, and stimulation of the cycle increases nuclear diacylglycerol and apparently induces translocation of protein kinase C to the nucleus. EMBO J. 1991;10:3207–3214. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04883.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martelli AM, Gilmour RS, Bertagnolo V, Neri LM, Manzoli L, Cocco L. Nuclear localization and signalling activity of phosphoinositidase C beta in Swiss 3T3 cells. Nature. 1992;358:242–245. doi: 10.1038/358242a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malviya AN, Rogue P, Vincendon G. Stereospecific inositol 1,4,5-[32P]trisphosphate binding to isolated rat liver nuclei: evidence for inositol trisphosphate receptor-mediated calcium release from the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:9270–9274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leite MF, Thrower EC, Echevarria W, Koulen P, Hirata K, Bennett AM, et al. Nuclear and cytosolic calcium are regulated independently. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2975–2980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0536590100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mak DO, Foskett JK. Single-channel inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor currents revealed by patch clamp of isolated Xenopus oocyte nuclei. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29375–29378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Echevarria W, Leite MF, Guerra MT, Zipfel WR, Nathanson MH. Regulation of calcium signals in the nucleus by a nucleoplasmic reticulum. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:440–446. doi: 10.1038/ncb980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogue PJ, Humbert JP, Meyer A, Freyermuth S, Krady MM, Malviya AN. cAMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylates and activates nuclear Ca2+-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9178–9183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allbritton NL, Oancea E, Kuhn MA, Meyer T. Source of nuclear calcium signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12458–12462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fox JL, Burgstahler AD, Nathanson MH. Mechanism of long-range Ca2+ signalling in the nucleus of isolated rat hepatocytes. Biochem J. 1997;326 (Part 2):491–495. doi: 10.1042/bj3260491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipp P, Thomas D, Berridge MJ, Bootman MD. Nuclear calcium signalling by individual cytoplasmic calcium puffs. EMBO J. 1997;16:7166–7173. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerasimenko OV, Gerasimenko JV, Tepikin AV, Petersen OH. ATP-dependent accumulation and inositol trisphosphate- or cyclic ADP-ribose-mediated release of Ca2+ from the nuclear envelope. Cell. 1995;80:439–444. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90494-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hennager DJ, Welsh MJ, DeLisle S. Changes in either cytosolic or nucleoplasmic inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate levels can control nuclear Ca2+ concentration. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4959–4962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.4959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santella L, Kyozuka K. Effects of 1-methyladenine on nuclear Ca2+ transients and meiosis resumption in starfish oocytes are mimicked by the nuclear injection of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and cADP-ribose. Cell Calcium. 1997;22:11–20. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark EA, Brugge JS. Integrins and signal transduction pathways: the road taken. Science. 1995;268:233–239. doi: 10.1126/science.7716514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newton CL, Mignery GA, Sudhof TC. Co-expression in vertebrate tissues and cell lines of multiple inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) receptors with distinct affinities for InsP3. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28613–28619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hagar RE, Burgstahler AD, Nathanson MH, Ehrlich BE. Type III InsP3 receptor channel stays open in the presence of increased calcium. Nature. 1998;396:81–84. doi: 10.1038/23954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramos-Franco J, Fill M, Mignery GA. Isoform-specific function of single inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor channels. Biophys J. 1998;75:834–839. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77572-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martelli AM, Billi AM, Manzoli L, Faenza I, Aluigi M, Falconi M, et al. Insulin selectively stimulates nuclear phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC) beta1 activity through a mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase-dependent serine phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 2000;486:230–236. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deisseroth K, Heist EK, Tsien RW. Translocation of calmodulin to the nucleus supports CREB phosphorylation in hippocampal neurons. Nature. 1998;392:198–202. doi: 10.1038/32448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perez-Terzic C, Pyle J, Jaconi M, Stehno-Bittel L, Clapham DE. Conformational states of the nuclear pore complex induced by depletion of nuclear Ca2+ stores. Science. 1996;273:1875–1877. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chawla S, Hardingham GE, Quinn DR, Bading H. CBP: a signal-regulated transcriptional coactivator controlled by nuclear calcium and CaM kinase IV. Science. 1998;281:1505–1509. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hardingham GE, Chawla S, Johnson CM, Bading H. Distinct functions of nuclear and cytoplasmic calcium in the control of gene expression. Nature. 1997;385:260–265. doi: 10.1038/385260a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pusl T, Wu JJ, Zimmerman TL, Zhang L, Ehrlich BE, Berchtold MW, et al. Epidermal growth factor-mediated activation of the ETS domain transcription factor Elk-1 requires nuclear calcium. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27517–27527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carrion AM, Link WA, Ledo F, Mellstrom B, Naranjo JR. DREAM is a Ca2+-regulated transcriptional repressor. Nature. 1999;398:80–84. doi: 10.1038/18044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dobi A, Agoston D. Submillimolar levels of calcium regulates DNA structure at the dinucleotide repeat (TG/AC)n. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5981–5986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson M, Andrade VA, Andrade SJ, Pusl T, Ortega JM, Goes AM, et al. Inhibition of the TEF/TEAD transcription factor activity by nuclear calcium and distinct kinase pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:267–274. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)03024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rasmussen CD, Means AR. The presence of parvalbumin in a nonmuscle cell line attenuates progression through mitosis. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3:588–596. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-3-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodrigues MA, Gomes DA, Leite MF, Grant W, Zhang L, Lam W, et al. Nucleoplasmic calcium is required for cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17061–17068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700490200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]