Abstract

The KATP channel is an important player in vascular tone regulation. Its opening and closure lead to vasodilation and vasoconstriction, respectively. Such functions may be disrupted in oxidative stress seen in a variety of cardiovascular diseases, while the underlying mechanism remains unclear. Here, we demonstrated that S-glutathionylation was a modulation mechanism underlying oxidant-mediated vascular KATP channel regulation. An exposure of isolated mesenteric rings to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) impaired the KATP channel-mediated vascular dilation. In whole-cell recordings and inside-out patches, H2O2 or diamide caused a strong inhibition of the vascular KATP channel (Kir6.1/SUR2B) in the presence, but not in the absence, of glutathione (GSH). Similar channel inhibition was seen with oxidized glutathione (GSSG) and thiol-modulating reagents. The oxidant-mediated channel inhibition was reversed by the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT) and the specific deglutathionylation reagent glutaredoxin-1 (Grx1). Consistent with S-glutathionylation, streptavidin pull-down assays with biotinylated glutathione ethyl ester (BioGEE) showed incorporation of GSH to the Kir6.1 subunit in the presence of H2O2. These results suggest that S-glutathionylation is an important mechanism for the vascular KATP channel modulation in oxidative stress.

Keywords: Ion Channels, Membrane Biophysics, Membrane Proteins, Oxidative Stress, Potassium Channels, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), Glutathione, Vascular Tones

Introduction

ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP)3 channels are regulated by intracellular ATP/ADP and couple intermediary metabolic states to membrane excitability. The activity of these channels is low under physiological conditions and drastically rises during metabolic stress (1, 2). The KATP channels are expressed in almost all tissues. In vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs), activation of KATP channels by several vasodilators reduces SMC membrane excitability, leading to vasorelaxation (3, 4). Activity of the channels is inhibited by vasoconstrictors (5), resulting in depolarization of the SMCs and vasoconstriction. Such a common vascular regulator is thus targeted by a variety of cellular events in physiological and pathological conditions (1, 6).

One important cellular event is oxidative stress that is known to play an important role in the development and maintenance of several cardiovascular diseases, such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, and diabetic vascular complications (7, 8). During oxidative stress, excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide (O⨪), hydroxyl radical (OH·), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), are overly produced causing vascular dysfunction and structural damages (9, 10). Previous studies indeed have shown that O⨪ suppresses KATP channels and blunts the pial arterial dilation responses (11). In diabetic patients, in whom oxidative stress is evident, KATP channel function is disrupted, leading to impaired vasodilation responses (12). In insulin-resistant rats, the KATP channel-dependent vasodilation is also impaired, which is likely to be mediated by ROS (13). Although the dysfunction of KATP channels in oxidative stress has been documented, the mechanism underlying channel modulation remains unknown (9, 14).

ROS can modulate proteins by intra- and intermolecular thiol oxidation (15, 16), which may be the underlying cause for the modulation of vascular KATP channels in oxidative stress. To test this hypothesis, we performed studies using a combined molecular biology, electrophysiology, and biochemistry approach. Our results showed that the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel, the major isoform of vascular KATP channels, was inhibited by micromolar concentrations of H2O2 as well as several other oxidants via S-glutathionylation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and Reagents

Unless stated, all reagents and chemicals used in this study were purchased from Sigma. H2O2 and glutathione (GSH) were freshly made and used within 4 h. Other reagents were prepared as concentrated stocks in double-distilled water or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). In cases where DMSO was used, the final concentration of DMSO in solution was <0.1% (v/v). At this concentration, DMSO did not have any detectable effect on the channel activity.

Mesenteric Artery Preparation and Tension Measurements

All animal experiments were performed in compliance with an approved protocol by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) at Georgia State University. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250 g body weight) were deeply anesthetized and sacrificed. Mesenteric arteries were dissected, and connective tissues were removed in physiological saline solution (PSS) containing the following (concentrations in mm): NaCl, 140; KCl, 4.6; CaCl2, 1.5; MgCl2, 1; glucose, 10; and HEPES, 5 (pH 7.3). The arteries were cut into small rings (2 mm in length) and transferred to ice-cold Krebs solution containing the following (concentrations in mm): NaCl, 118.0; NaHCO3, 25.0; KCl, 3.6; MgSO4, 1.2; KH2PO4, 1.2; glucose, 11.0; and CaCl2, 2.5. The arterial ring was mounted on a force-electricity transducer (Model FT-302; iWorx/CBSciences Inc. Dover, NH) for measurements of isometric force contraction in a 5-ml tissue bath containing air-bubbled Krebs solution. Tissue vitality was confirmed with the contraction response to phenylephrine (PE). When endothelium-free rings were needed, the rings were rubbed with sanded polyethylene tubing. The endothelium-free rings were then tested for PE contraction followed by acetylcholine (ACh, 1 μm) for relaxation. The rings were considered to be endothelium-free, if >90% relaxation was eliminated. PE and ACh were then washed out, and the rings were allowed to equilibrate in the Krebs solution for another 30–60 min before the experiments.

Expression of KATP Channel in HEK293 Cells

KATP channels were expressed in HEK293 cells because these cells have low numbers of endogenous channels. The HEK293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM)/F12 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C with 5% CO2. A eukaryotic expression vector pcDNA3.1 was used to express rat Kir6.1 (GenBankTM No. D42145) in cells with SUR2B (GenBankTM No. D86038; mRNA isoform, NM_011511). A 35-mm Petri dish of cells was transfected with 1 μg of Kir6.1 or Kir6.2 and 3 μg of SUR2B using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA). To facilitate the identification of positively transfected cells, 0.4 μg of green fluorescent protein (GFP) cDNA (pEGFP-N2; Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) was included in the cDNA mixture. One day after transfection, cells were disassociated with 0.25% trypsin, split, and transferred to coverslips for further growth. Experiments were performed on the cells in coverslips during the following 12–48 h.

Electrophysiology

Patch-clamp experiments were carried out at room temperature as described previously (3–5, 17, 18). In brief, fire-polished patch pipettes with 2–5 MΩ resistance were made of 1.2-mm borosilicate glass capillaries. Whole-cell currents were recorded in single-cell voltage clamp with a holding potential of 0 mV and step to −80 mV. The bath solution contained the following (concentration in mm): KCl, 10; potassium gluconate, 135; EGTA, 5; glucose, 5; and HEPES, 10 (pH 7.4). The pipette was filled with a solution containing the following (concentration in mm): KCl, 10; potassium gluconate, 133; EGTA, 5; glucose, 5; K2ATP, 1; NaADP, 0.5; MgCl2,1; and HEPES, 10 (pH = 7.4). To avoid nucleotide degradation, all intracellular solutions were freshly made and used within 4 h. All the recordings were made with the Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments Inc., Foster City, CA). The data were low-pass filtered (2 kHz, Bessel 4-pole filter, −3 dB) and digitized (10 kHz, 16-bit resolution) with Clampex 9 (Axon Instruments Inc.). Macroscopic currents were recorded from giant inside-out patches, and single-channel currents were recorded from small inside-out patches with a constant single voltage of −80 or −60 mV. Symmetric high K+ (145 mm in total) was used in both bath and pipette solutions and K2ATP (1 mm), and NaADP (0.5 mm), were included in the bath solution to maintain the channel activity. Higher sampling rate (20 kHz) was used to digitize the currents recorded from inside-out patch. Data were analyzed using Clampfit 9 (Axon Instruments Inc.).

Immunochemistry

Immunochemistry was performed on the HEK293 cells with and without Kir6.1/SUR2B transfection. Two hours before the experiments, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium. Biotinylated glutathione ethyl ester (BioGEE; 250 μm; Invitrogen) was added to the medium and incubated for 1 h followed by an H2O2 (750 μm) challenge for 15 min. The medium was then discarded, and the cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (containing 0.3% Triton X-100) to remove the excessive free BioGEE that had not conjugated with the proteins. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehdyde for 30 min followed by three washes with PBS. Dylight-488-conjugated streptavidin was diluted 1:1000 in PBS and added to the cells for 1 h of incubation at room temperature. After three PBS washes, the cells were examined under the LSM 510 confocal microscope (Zeiss). For double staining, the cells were further incubated with rabbit primary antibody against Kir6.1 for 2 h followed by three washes. Dylight-594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1000; Jackson ImmunoResearch) was used to visualize the Kir6.1 staining. Experiments were repeated three times.

Streptavidin Pull-down Assay and Western Blot

HEK293 cells expressing Kir6.1/SUR2B channels and the A10 smooth muscle cell line were used for this experiment. A10 cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C in humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. BioGEE and H2O2 treatments were performed as described above in Immunochemistry. The cells were then washed once and lysed using RIPA buffer (Sigma). Samples were run on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide non-reducing gel and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). Rabbit primary antibodies against Kir6.1 (1:500; Sigma) and secondary antibodies conjugated with alkaline phosphatase were used in the Western blot (1:10,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch). Signals were visualized by SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific).

Biotin-GSH-conjugated proteins were pulled down using streptavidin-dynabeads according to the instructions provided by Invitrogen. Briefly, the beads were washed three times before the immobilization. Samples were then mixed with beads and incubated at room temperature with gentle rotation for 30 min. A magnet was used to separate the biotinylated molecules-bead complex from other unlabeled proteins. Supernatant containing unlabeled proteins was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended followed by three washes. The biotinylated molecules-beads complex was then resuspended in the loading buffer with 0.1% SDS and boiled so that glutathionylated proteins were released into the solvent for further analysis. Experiments on HEK293 cells transfected with the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel were repeated four times, and experiments on A10 cells were repeated five times.

Data Analysis

Data were presented as means ± S.E. Differences were evaluated using Student's t-tests or ANOVA, and statistical significance was accepted when p < 0.05.

RESULTS

H2O2 Impaired Pinacidil-induced Vasodilation in Isolated Mesenteric Rings

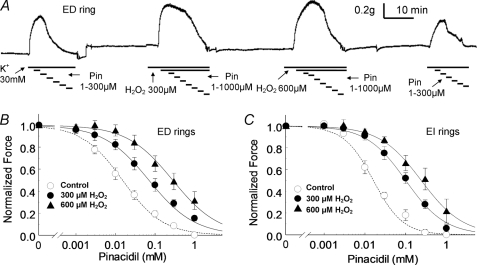

To define conditions whereby oxidative stress disrupts vascular KATP channel function, we examined the vasodilating effects of the KATP channel opener in the presence and absence of H2O2. Experiments were conducted on endothelium-intact (EI) and endothelium-denuded (ED) mesenteric rings. Vasoconstriction was first produced with 30 mm K+. This was followed by treatments with increasing concentrations of pinacidil, a specific KATP channel opener and a strong vasodilator (Fig. 1A). The vascular tones were measured with a force-electricity transducer. A pretreatment of the rings with H2O2 (300, 600 μm) impaired the pinacidil-induced vasodilation in both ED and EI rings. In ED rings, the IC50 concentration of pinacidil for vasorelaxation was raised by 5–18-fold with the 300 μm and 600 μm H2O2 treatments, respectively (Fig. 1, A and B). Similar results were obtained in EI rings (Fig. 1C). Taken together, our data indicate that the function of vascular KATP channels is disrupted in oxidative stress.

FIGURE 1.

The responses of mesenteric rings to KATP channel opener. A, the relaxing effect of the KATP channel opener, Pin, with and without H2O2 pretreatment were studied in a vascular endothelium-denuded (ED) ring obtained from mesenteric artery. The ring was contracted with 30 mm K+ followed by increasing concentrations of Pin. The constriction force was measured using a force-electricity transducer. Under control conditions, Pin effectively relaxed the ring with a midpoint effect of ∼10 μm. K+ and Pin were then washed out. After equilibration for 30 min, 300 μm H2O2 was applied to the ring for 10 min, and the ring was constricted again using K+ followed by incremental concentrations of Pin. Under this condition, the relaxing effect of Pin was impaired. About a 10-fold higher concentration of Pin was needed to relax the ring to the same 50% level. This experiment was then performed again with another dose of H2O2 (600 μm) pretreatment followed by a final control round in which >80% recovery in both constriction and relaxation was seen. B, in ED rings, the concentration-dependent vasodilation of Pin was shown in the presence and absence of H2O2. Data were described by the Hill equations with IC50 of 15 μm in control (n = 11), 70 μm with 300 μm H2O2 pretreatment (n = 4), and 280 μm with 600 μm H2O2 pretreatment (n = 7), respectively. C, similar experiments were also done in endothelium-intact (EI) rings with IC50 16 μm in control (n = 6), 100 μm with 300 μm H2O2 pretreatment (n = 6), and 240 μm with 600 μm H2O2 pretreatment (n = 5), respectively.

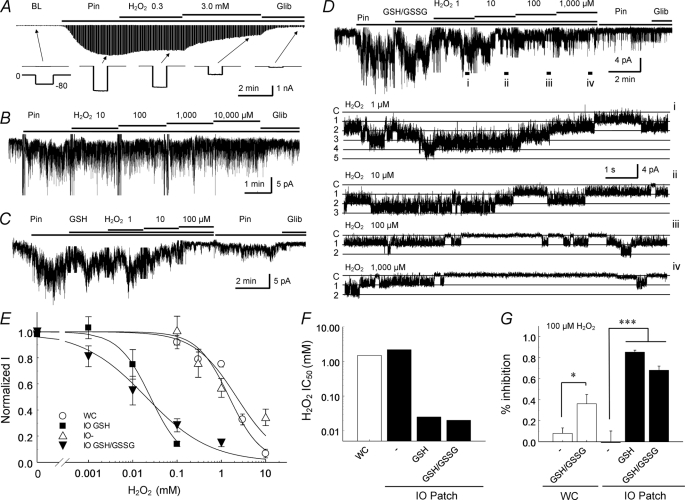

H2O2 Inhibited Kir6.1/SUR2B Channel Activity in the Presence of GSH

The Kir6.1/SUR2B channel is the major isoform of vascular KATP channels (6, 19, 20). Thus, we studied its modulation by expressing the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel in HEK293 cells. In whole-cell voltage clamp, the baseline Kir6.1/SUR2B currents were small, and no obvious effect on the currents was observed when H2O2 was applied. After the currents were activated by pinacidil, however, the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel was dose-dependently inhibited by H2O2 with an IC50 of 1.53 mm (Fig. 2A, E, and F).

FIGURE 2.

Responses of vascular KATP channel to H2O2. A, whole-cell currents were recorded from a cell expressing Kir6.1/SUR2B channels. The bath solutions contained 145 mm K+, making the reversal potential of the K+ currents close to 0 mV. Command pulses of −80 mV were given every 3 s. The recording pipette was filled with the same solution (bath solution) with the addition of 1 mm ATP, 0.5 mm ADP, and 1 mm free Mg2+. Application of Pin (10 μm) markedly augmented the whole-cell currents that were subsequently inhibited by 0.3 mm and 3 mm H2O2 progressively. The KATP channel-specific blocker, Glib (10 μm) further reduced channel activity. The lower panel shows individual current traces produced by single command pulses. B, currents were recorded from giant inside-out patches obtained from HEK293 cells expressing the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel with a holding potential of −60 mV. Currents were activated by Pin, followed by increasing doses of H2O2. The H2O2 exposures did not lead to significant changes in channel activity. C, in the presence of GSH (100 μm), the H2O2 application strongly inhibited the Pin-activated currents, and the channels were almost completely inhibited by 100 μm H2O2 in giant inside-out patches. D, similar channel inhibition by H2O2 occurred in the presence of 2 mm GSH and 40 μm GSSG. Single channel activity from different treatments was displayed in expanded records from the top trace. Five active channels were seen, which were dose-dependently inhibited by H2O2. Note that the channel retained the same conductance with H2O2 exposure. Labels on the left: C, closure and 1, 2…5, the first, second … fifth opening. The locations from where these traces were expanded were marked with i–iv. E, dose-response relationships obtained in the whole-cell or inside-out patch configurations with or without GSH/GSSG. WC, whole-cell configuration; IO GSH, inside-out patch with 100 μm GSH; IO-, inside-out patch without GSH; IO GSH/GSSG, inside-out patch with a mixture of 2 mm GSH and 40 μm GSSG; F, the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of H2O2 was compared under whole-cell (WC) and inside-out patch (IO) configurations in the absence or presence of GSH or GSH/GSSG; G, the effect of 100 μm H2O2 on the channel activity showed significant differences (*, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001) between these conditions.

The results of whole-cell recordings may be affected by washout or inadequate controls of cytosolic soluble factors that can be potentially involved in the channel modulation, such as endogenous GSH and GSSG. Therefore, further studies were performed in excised patches. In giant inside-out patches, millimolar concentrations of H2O2 were required to inhibit the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel in the absence of cytosolic soluble components (Fig. 2, B, E, and F). Strikingly, the administration of small amount of glutathione (GSH) drastically enhanced the channel sensitivity to H2O2. In the presence of 100 μm GSH, H2O2 as low as 10 μm began to inhibit channel activity, and clear concentration dependence was seen with an IC50 of 25 μm (Fig. 2, C, E, and F). The effect of H2O2 was subsequently studied in the presence of 2 mm GSH and 40 μm GSSG, a ratio that is close to the physiological concentrations of GSH/GSSG in the cytosol (21). Under this condition, H2O2 also potently inhibited the channel with an IC50 of 20 μm (Fig. 2, D–F).

Consistent with these observations in inside-out patches, a supplement of GSH/GSSG (2 mm and 40 μm, respectively) to the pipette solution significantly enhanced the channel sensitivity to H2O2 in whole-cell recordings. With GSH/GSSG in the pipette solution, 100 μm H2O2 inhibited the whole-cell currents by 36.2 ± 8.8% (n = 5) compared with 8.0 ± 5.1% when GSH/GSSG were absent (n = 4, p < 0.05; Fig. 2G). In contrast, the same concentration of H2O2 (100 μm) inhibited the channel by >80% in inside-out patches in the presence of GSH or GSH/GSSG (Fig. 2G). The difference in the H2O2 sensitivity between inside-out patches and whole-cell recordings may be due to the diffusion kinetics across plasma membranes. Using the pseudo-first-order reaction analysis described by Tang et al. (22) in their study on H2O2-mediated BK channel inhibition, we calculated the pseudo first order constant to be 724 m−1 min−1 based on the average Kir6.1/SUR2B channel inhibition (36.2%) by 100 μm H2O2 (with GSH/GSSG) during a period of <5 min. With this constant, our further calculation showed that a 50% inhibition of the channel was achieved by ∼23 μm H2O2 in ∼30 min, which implies a protective role of the membrane barrier against a burst of H2O2 (see discussion for details). The requirement of GSH for H2O2 to produce its channel inhibition effect indicates that GSH-mediated protein modifications of the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel, such as S-glutathionylation, are likely to occur when H2O2 is produced as an intermediary metabolite or a product of oxidative stress.

To understand the biophysical mechanisms underlying Kir6.1/SUR2B modulation, we analyzed single channel properties recorded in regular inside-out patches in the presence of 2 mm GSH and 40 μm GSSG. We found that the channel open-state probability was progressively suppressed with increased H2O2 concentrations while the unitary conductance remained unchanged (Fig. 2D).

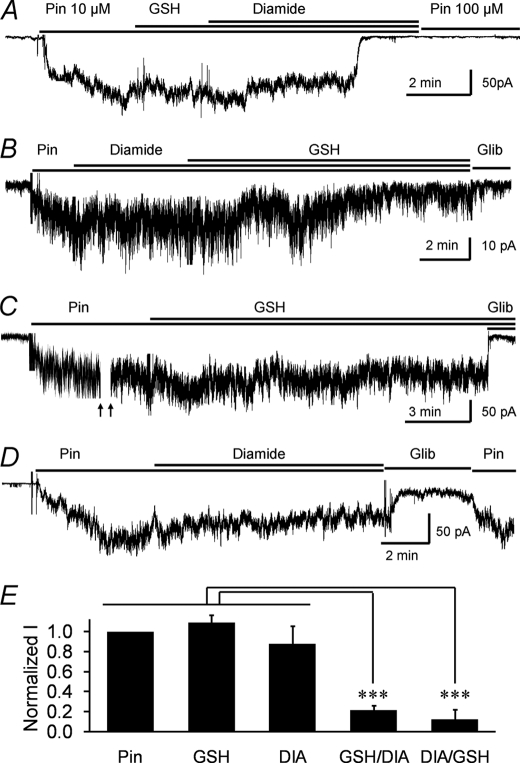

GSH-dependent Modulation by Other Oxidants

Diamide, an oxidant that produces intra- and intermolecular disulfide bonds, is known to cause S-glutathionylation in the presence of GSH (23, 24). In giant inside-out patches, we found that the joint application of diamide and GSH drastically inhibited channel activity within 2–8 min, regardless of the order of application, i.e. 78.4 ± 5.1% inhibition with GSH first and 87.9 ± 8.7% inhibition with diamide first (Fig. 3, A, B, and E). No statistical difference was found between the experiments (p > 0.05, n = 12). In contrast, neither GSH (Fig. 3, C and E) nor diamide alone (Fig. 3, D and E) resulted in such channel inhibition over an extended time period (8–14 min), suggesting that the channel inhibition is unlikely to be a result of the formation of disulfide bonds within a protein or between proteins.

FIGURE 3.

The effect of diamide/GSH on the channel activity. Currents were studied in giant inside-out patches obtained from HEK293 cells expressing the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel with a holding potential of −60 mV. A, after channel activation by pinacidil, application of GSH (100 μm) followed by DIA (100 μm) for additional ∼4 min strongly inhibited the channel activity. The inhibition was not reversed by high concentration of pinacidil (100 μm). B, in another cell, the application of DIA followed by GSH also markedly inhibited the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel activity. C, a prolonged GSH (100 μm) treatment did not have detectable effects on the Pin-activated currents. D, a prolonged treatment (8 min) with DIA (100 μm) did not cause marked channel inhibition. E, summary of the effects of Pin, GSH alone, DIA alone, GSH followed by DIA, and DIA followed by GSH.

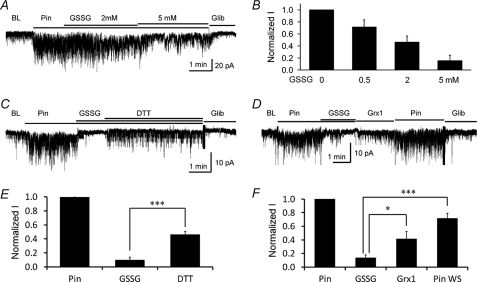

GSSG is another S-glutathionylation inducer (23, 24). In giant inside-out patches, we found that the application of GSSG inhibited the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4, A and B). Evident channel inhibition was seen with 0.5 mm GSSG, and stronger inhibition was produced by higher concentrations (Fig. 4, A and B). Together, these data strongly suggest that S-glutathionylation appears to occur in the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel during oxidative stress leading to the inhibition of the channel activity.

FIGURE 4.

The effect of GSSG on the channel activity and its reversibility. A, in a cell expressing the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel, the Pin-activated currents were dose-dependently inhibited by GSSG treatment. B, summary of different dosages of GSSG on the channel activity (n = 4∼6). C, in a giant inside-out patch, the Pin-induced currents were strongly inhibited by 5 mm GSSG. The current partially recovered with the application of the reducing agent, DTT (5 mm). D, Pin-induced currents were inhibited by GSSG and partially reversed by 4 μm Grx1. Additional pinacidil perfusion (Pin WS) further augmented the channel activity. E and F, quantification of the data from C and D, respectively (n = 4). *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001.

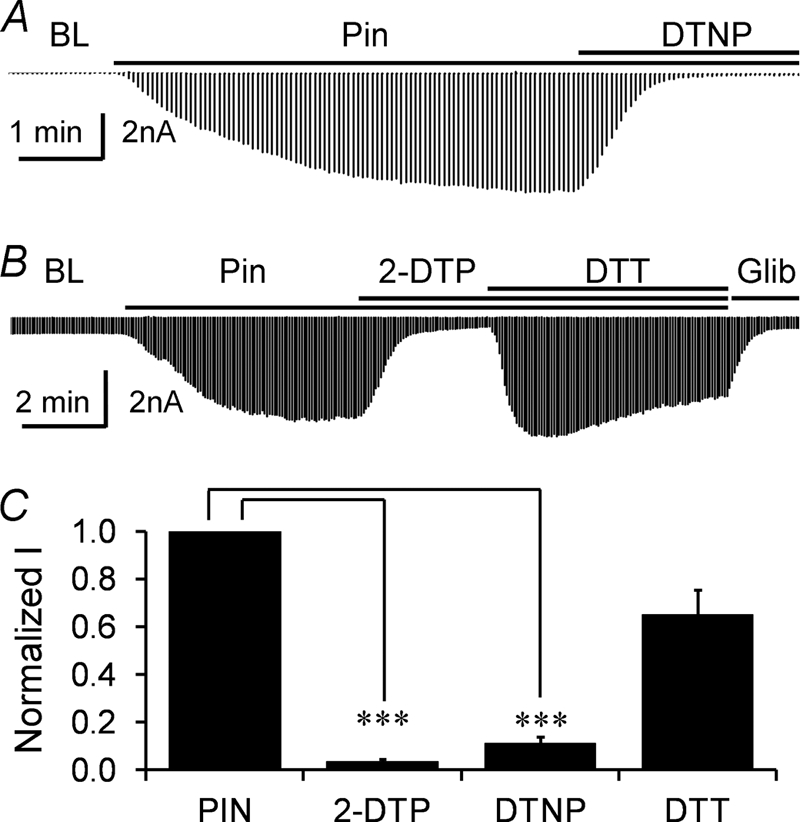

Thiol Oxidants Inhibited the Kir6.1/SUR2B Channel

Several reactive 2-pyridinedisulfides (2-PDSs) are known to target the free sulfhydryl groups of cysteine residues forming thiol moieties, a protein modulation mechanism that resembles S-glutathionylation (25). Thus, we further tested the thiol oxidation of the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel using 2-PDSs. In whole-cell recording, the bath application of 2, 2′-dithiodipyridine (2-DTP; 50 μm), a membrane permeable 2-PDS, inhibited the Kir6.1/SUR2B currents almost completely (by 95.8 ± 1.1%; n = 5; Fig. 5, B and C). Similar results were obtained with another membrane permeable 2-PDS, 2, 2′-dithiobis-5-nitropyridine (DTNP; 50 μm), which inhibited the currents by 88.8 ± 2.7% (n = 5; Fig. 5, A and C). These observations are also consistent with S-glutathionylation.

FIGURE 5.

Thiol modification by reactive disulfide reagents. A, in whole-cell configuration, the Pin-activated currents were potently inhibited by DTNP (50 μm). B, another reactive disulfide, 2-DTP (50 μm) also had a strong inhibitory effect on the Pin-sensitive currents of the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel, and this inhibitory effect was reversed by the reducing agent DTT (5 mm). C, the effects of 2-DTP (50 μm), DTNP (50 μm), and DTT (5 mm) on the channel activity were summarized. ***, p < 0.001.

Reversal of the KATP Channel Inhibition by Deglutathionylation Reagents

After pinacidil-activated currents were strongly inhibited by the oxidants, washout with addition of pinacidil (10 μm) had only a modest effect on channel activity (10.2 ± 2.6% of the original pinacidil-induced currents; n = 4; Fig. 2C). Increasing the pinacidil concentration to 100 μm had no additional effect (3.9 ± 0.6% of the original pinacidil induced-current, n = 3; Fig. 3A). However, application of the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT; 5 mm) reversed the GSSG-mediated (5 mm) current inhibition by 36.1 ± 4.7% (p < 0.001; n = 4; Fig. 4, C and E). Similarly, the 2-PDS mediated channel inhibition was partially reversed by DTT (34.9 ± 10.3% inhibition, n = 5; Fig. 5, B and C).

An exposure of the cell to the specific deglutathionylation reagent glutaredoxin-1 (Grx1; 4 μm) immediately reversed current inhibition by 27.8 ± 10.5% (p < 0.05; n = 4; Fig. 4D). After washout of both GSSG and Grx1, the pinacidil-induced currents were resumed to 72.0 ± 7.1% of its original level (p < 0.001; n = 4; Fig. 4, D and F). Collectively, these data suggest that S-glutathionylation-mediated Kir6.1/SUR2B channel inhibition can be reversed substantially by reducing or deglutathionylation reagents.

Biochemical Evidence for the Kir6.1 S-Glutathionylation

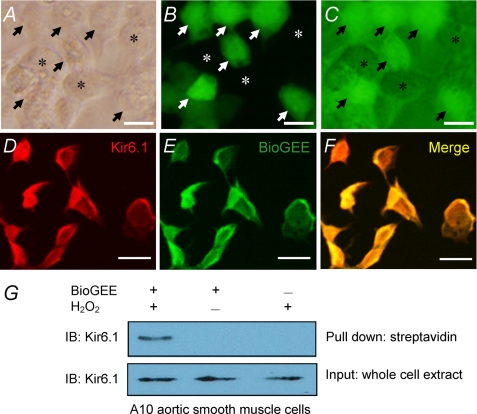

Does S-glutathionylation occur on the channel protein or on another protein that regulates the channel activity? To address this question, we examined S-glutathionylation using membrane-permeable BioGEE. HEK293 cells transfected with Kir6.1/SUR2B or the expression vector alone were loaded with BioGEE (250 μm) for 1 h followed by an H2O2 (750 μm) challenge for 15 min. Clear labeling was observed in the Kir6.1/SUR2B-transfected cells (Fig. 6, A–C), whereas a rather weak stain was seen with the mock transfection (data not shown). When the cells were double-stained with BioGEE (green) and Kir6.1 antibodies (red), co-localization was observed (Fig. 6, D–F).

FIGURE 6.

Biochemical detection of the Kir6. 1-GSH interaction using BioGEE. A, B, and C, HEK293 cells transfected with Kir6.1/SUR2B were loaded with BioGEE for 1 h and then challenged with H2O2 (750 μm) for 15 min. Free, unlabeled BioGEE was washed out, and the cells were visualized with streptavidin-Dylight 488 under phase contrast (A), fluorescence microscopy (B), and overlaid image (C). Labeled and unlabeled cells are indicated by arrows and asterisks, respectively. D, E, and F, 1.25-μm confocal optical slices of HEK293 cells transfected with Kir6.1/SUR2B were double-stained with Kir6.1 (red) and BioGEE (green). Yellow indicated that Kir6.1 co-localizes with BioGEE. Scale bar, 25 μm. G, the A10 aortic smooth muscle cells were lysed with RIPA buffer. Kir6.1 proteins were detected in the whole-cell lysis (lower panel). Only those protein samples that were obtained from the cells treated with both H2O2 and BioGEE showed a clear band in the streptavidin pull-down assay (upper panel).

The Kir6.1 S-glutathionylation was further tested with the streptavidin pull-down assay (26). The A10 vascular smooth muscle cell line, in which the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel was endogenously expressed (17, 27), was loaded with BioGEE (250 μm) for 1 h followed by an H2O2 (750 μm) challenge for 15 min. A strong Kir6.1-reactive band (∼32 kDa) was detected in the whole-cell lysate (Fig. 6G, lower panel). After pull-down with streptavidin, the cell lysate pretreated with a combination of BioGEE and H2O2 showed a clear band of Kir6.1 immunoreactivity (Fig. 6G, upper panel), whereas no band was observed in cell lysates treated with either BioGEE or H2O2 alone (Fig. 6G). Similar results were obtained using HEK293 cells transfected with Kir6.1/SUR2B (supplemental Fig. S1).

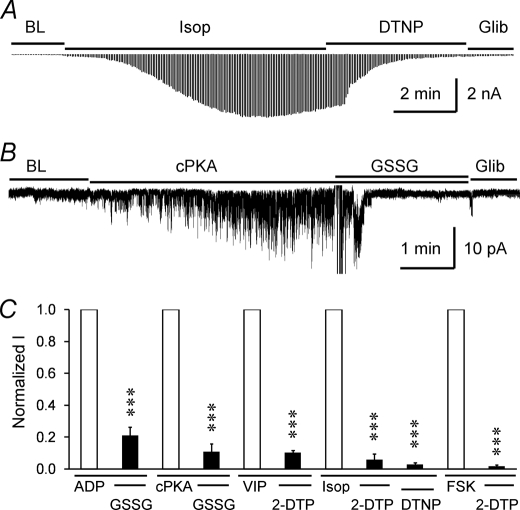

Oxidant-mediated Blockade of the KATP Channel Activation by Natural Activators

Kir6.1/SUR2B channel activity is low under basal condition but increases significantly in the presence of several vasodilating hormones and neurotransmitters that are coupled to the adenylyl cyclase-cAMP-PKA pathway (3, 18). Therefore, we examined the effect of S-glutathionylation on the Kir6.1/SUR2B currents activated by the vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP; 100 nm) and β-adrenoreceptor agonist isoproterenol (Isop; 100 nm), both of which activate Kir6.1/SUR2B currents through the PKA pathway. In the whole-cell configuration, DTNP (50 μm) or 2-DTP (50 μm) inhibited Isop-activated currents strongly (94.1 ± 3 .6% and 97.0 ± 0.9%, respectively; n = 4; Fig. 7, A and C). Similarly, 2-DTP inhibited the VIP-activated currents by 89.7 ± 1.4% (n = 3; Fig. 7C). 2-DTP and DTNP were not acting at the level of the receptors as forskolin (an adenylyl cyclase activator) elicited currents were also potently inhibited by these agents (Fig. 7C). In inside-out patches, basal currents as well as the currents activated by the catalytic subunit of PKA (cPKA; 50 units/ml), were strongly inhibited by 5 mm GSSG as well (79.1 ± 5.4%, n = 4 and 89.1 ± 5.0%, n = 4, respectively; Fig. 7, B and C). Taken together, these results indicate that the Kir6.1/SUR2B channels are inhibited by S-glutathionylation, regardless of how the channels are activated.

FIGURE 7.

Redox-mediated blockade of the KATP channel activation by natural activators. A, in whole-cell configuration, Isop (100 nm) activated Kir6.1/SUR2B currents were subsequently inhibited by DTNP (50 μm). B, in a giant inside-out patch, the channel was activated by the catalytic subunit of PKA (cPKA, 50 units/ml), and inhibited by 5 mm GSSG. C, summary of the effects of GSSG, DTNP, and 2-PDS on the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel induced by a variety of channel activators (n = 3∼5). Abbreviations: FSK, forskolin; VIP, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. ***, p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Inflammatory oxidative stress is a common pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, and diabetic vascular complications, which mostly result from the overproduction of ROS overwhelming the capacity of cellular antioxidant defense systems (7, 8). When excessively produced, ROS can cause damages to lipids, proteins, and nucleotides, leading to cell dysfunction, structural injuries, and death (7). As the universal antioxidant treatment did not yield promising results in clinic trials (28), the identification of specific molecules and the understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the oxidant-mediated protein modulation becomes crucial for the development of novel therapeutic strategies. Our studies indicate that the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel is inhibited by micromolar concentrations of H2O2 through S-glutathionylation. Such channel inhibition is of pathophysiological relevance and is likely to occur in vasculatures as the production of micromolar concentrations of H2O2 has been shown during oxidative stress (10).

H2O2, O⨪, OH·, and peroxyl (RO⨪) are the major oxidants produced endogenously in biological systems. Their concentrations in the cytoplasm are tightly controlled by several antioxidant systems (29). Early studies have shown that ROS including H2O2 have modulatory effects on membrane proteins (22, 30, 31). Most of the studies, however, use millimolar concentrations of H2O2 (32, 33). In the present study, we have observed a clear inhibition of the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel by H2O2 with IC50 of ∼1.5 mm in whole-cell recording. In contrast, the inhibition of KATP currents can be clearly seen with micromolar concentrations of H2O2 in vascular rings. The major reason for the discrepancy is likely to be the effect of washout or inadequate controls of the cytosolic soluble factors that play a role in the channel modulation in oxidative stress. Indeed, some of the cytosolic substances are identified to be GSH and GSSG in the present study.

Searching for the missing cytosolic factors to better characterize the effect of H2O2, we conducted experiments in giant inside-out patches. We have found that supplying a small amount of exogenous GSH dramatically reduces the concentration of H2O2 needed for channel inhibition. Using 2 mm GSH and 40 μm GSSG, which mimic the intracellular GSH/GSSG ratio (21, 34), we have also observed clear channel inhibition by micromolar concentration of H2O2. The drastic effect of GSH/GSSG on the channel sensitivity to H2O2 is not only seen in inside-out patches, but also takes place in the whole-cell recordings. A supplement of GSH/GSSG to the pipette solution markedly augments the H2O2-mediated inhibition of the whole-cell Kir6.1/SUR2B currents.

Comparing the inside-out patch data with the whole-cell recordings, we have found that the lower H2O2 sensitivity in the whole-cell recordings appears to be also related to the transmembrane diffusion kinetics. The limited capacity of transmembrane diffusion may act as a cellular protection mechanism, diminishing or even eliminating the effect of a burst of H2O2 production in the interstitial fluid. In the vascular inflammation state, however, such a membrane barrier does not seem adequate to protect the cell against a long-lasting production of H2O2. Consequently, H2O2 manages to pass through the plasma membranes and inhibits the channel from inside with a potency similar to that seen in inside-out patches.

Such channel inhibition is not limited to H2O2 as diamide, another oxidant, also produces strong channel inhibition when applied together with GSH. Furthermore, channel inhibition can be produced by the general S-glutathionylation-inducer GSSG. These results thus indicate that S-glutathionylation is likely to be the underlying cause for Kir6.1/SUR2B channel inhibition by these oxidants under pathophysiological conditions.

Hence, several lines of evidence shown in the present study support S-glutathionylation of the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel. (i) The channel is inhibited by H2O2 or diamide potently only when there is GSH. (ii) The S-glutathionylation inducer GSSG causes the channel inhibition. (iii) Several 2-PDSs reactive with thiol groups to form adaptors at cysteine residues inhibit the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel in micromolar concentrations. (iv) The oxidant-mediated channel inhibition can be reversed by the specific deglutathionylation reagent Grx1 and the general reducing reagent DTT. (v) Streptavidin pull-down assays reveal the incorporation of the GSH moiety to the Kir6.1 subunit in the presence but not in the absence of H2O2. This KATP channel modulation mechanism is not limited to the pinacidil-induced currents. The KATP currents activated by the natural vasodilators VIP and Isop are similarly inhibited by these oxidants.

The modulation of protein activity by S-glutathionylation is a newly recognized post-translational regulatory mechanism (35, 36). This process, facilitated by oxidative stress and also seen in unstressed cells, can result in major changes to protein conformations and functions (16). Such modulation has been demonstrated in a large number of proteins using microarray (37) or proteomic analysis (38), while the physiological relevance of this modulation remains to be understood (36). Several recent studies indicate that the following membrane proteins are modulated by S-glutathionylation: the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (24), the ryanodine receptor (39), the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (40), and the Na+-K+ pump (41). The present study has shown for the first time that an important vascular tone regulator, Kir6.1/SUR2B channel, is subject to S-glutathionylation produced by H2O2 at physiological or pathophysiological concentrations. This channel modulation by H2O2 can lead to impairment of the vasodilation responses in a variety of vascular complications. Therefore, the demonstration of S-glutathionylation as a regulatory mechanism has important clinical implications. With the information, new therapeutic strategies may be formulated by preventing the oxidative modulation of the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel.

Another similar post-translational regulation mechanism is S-nitrosylation through which a nitric oxide (NO) moiety is incorporated into the thiol group of a cysteine residue (25, 42). However, our initial attempts using NO donors yielded inconsistent results (data not shown).

In conclusion, our studies indicate that the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel is inhibited by H2O2 at micromolar concentrations owing to S-glutathionylation. The demonstration of the mechanism underlying the impairment of the vascular KATP channel should have impacts on the treatment and prevention of several vascular diseases caused by oxidative stress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Yinwei Zhang and Ravi Charka Turaga for assistance with the biochemical experiments. We are grateful to Dr. Deb Baro, Dr. Yuan Liu, and their laboratory members for suggestions on the immunochemistry and Western blot analysis, and to Timothy C. Trower for proofreading the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant HD060959 and the American Heart Association (09GRNT2010037).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- KATP channel

- ATP-sensitive K+ channel

- Kir

- inwardly rectifying potassium channels

- SUR

- sulfonylurea receptors

- Pin

- pinacidil

- Glib

- glibenclamide

- PSS

- physiological saline solution

- BioGEE

- biotinylated glutathione ethyl ester

- RIPA

- radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- 2-PDS

- 2-pyridinedisulfides

- 2-DTP

- 2,2′-dithiodipyridine

- DTNP

- 2,2′-dithiobis-5-nitropyridine

- Isop

- isoproterenol

- Grx

- glutaredoxin

- IC50

- half-maximal inhibitory concentration

- HEK293 cells

- human embryonic kidney 293 cells

- cPKA

- catalytic subunit of PKA

- DIA

- diamide.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miki T., Seino S. (2005) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 38, 917–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nichols C. G. (2006) Nature 440, 470–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi Y., Wu Z., Cui N., Shi W., Yang Y., Zhang X., Rojas A., Ha B. T., Jiang C. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 293, R1205–R1214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Y., Shi Y., Guo S., Zhang S., Cui N., Shi W., Zhu D., Jiang C. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778, 88–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi W., Cui N., Shi Y., Zhang X., Yang Y., Jiang C. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 293, R191–R199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teramoto N. (2006) J. Physiol. 572, 617–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madamanchi N. R., Vendrov A., Runge M. S. (2005) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 29–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brownlee M. (2001) Nature 414, 813–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gutterman D. D., Miura H., Liu Y. (2005) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 671–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ardanaz N., Pagano P. J. (2006) Exp. Biol. Med. 231, 237–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstead W. M. (1999) Stroke 30, 153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miura H., Wachtel R. E., Loberiza F. R., Jr., Saito T., Miura M., Nicolosi A. C., Gutterman D. D. (2003) Circ. Res. 92, 151–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erdös B., Simandle S. A., Snipes J. A., Miller A. W., Busija D. W. (2004) Stroke 35, 964–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weintraub N. L. (2003) Circ. Res. 92, 127–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moran L. K., Gutteridge J. M., Quinlan G. J. (2001) Curr. Med. Chem. 8, 763–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalle-Donne I., Rossi R., Giustarini D., Colombo R., Milzani A. (2007) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43, 883–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi W., Cui N., Wu Z., Yang Y., Zhang S., Gai H., Zhu D., Jiang C. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3021–3029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi Y., Chen X., Wu Z., Shi W., Yang Y., Cui N., Jiang C., Harrison R. W. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7523–7530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao K., Tang G., Hu D., Wang R. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 296, 463–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tricarico D., Mele A., Lundquist A. L., Desai R. R., George A. L., Jr., Conte Camerino D. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 1118–1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waypa G. B., Guzy R., Mungai P. T., Mack M. M., Marks J. D., Roe M. W., Schumacker P. T. (2006) Circ. Res. 99, 970–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang X. D., Garcia M. L., Heinemann S. H., Hoshi T. (2004) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kil I. S., Kim S. Y., Park J. W. (2008) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 373, 169–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang W., Oliva C., Li G., Holmgren A., Lillig C. H., Kirk K. L. (2005) J. Gen. Physiol. 125, 127–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida T., Inoue R., Morii T., Takahashi N., Yamamoto S., Hara Y., Tominaga M., Shimizu S., Sato Y., Mori Y. (2006) Nat. Chem. Biol. 2, 596–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zmijewski J. W., Banerjee S., Abraham E. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 22213–22221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun X., Cao K., Yang G., Huang Y., Hanna S. T., Wang R. (2004) Biochem. Pharmacol. 67, 147–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kris-Etherton P. M., Lichtenstein A. H., Howard B. V., Steinberg D., Witztum J. L. (2004) Circulation 110, 637–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pryor W. A., Houk K. N., Foote C. S., Fukuto J. M., Ignarro L. J., Squadrito G. L., Davies K. J. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 291, R491–R511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y., Gutterman D. D. (2002) Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 29, 305–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zha X. M., Wang R., Collier D. M., Snyder P. M., Wemmie J. A., Welsh M. J. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 3573–3578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krippeit-Drews P., Kramer C., Welker S., Lang F., Ammon H. P., Drews G. (1999) J. Physiol. 514, 471–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ichinari K., Kakei M., Matsuoka T., Nakashima H., Tanaka H. (1996) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 28, 1867–1877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown L. A., Ping X. D., Harris F. L., Gauthier T. W. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 292, L824–L832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dalle-Donne I., Rossi R., Colombo G., Giustarini D., Milzani A. (2009) Trends Biochem. Sci 34, 85–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dalle-Donne I., Milzani A., Gagliano N., Colombo R., Giustarini D., Rossi R. (2008) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10, 445–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fratelli M., Goodwin L. O., Ørom U. A., Lombardi S., Tonelli R., Mengozzi M., Ghezzi P. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 13998–14003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lind C., Gerdes R., Hamnell Y., Schuppe-Koistinen I., von Löwenhielm H. B., Holmgren A., Cotgreave I. A. (2002) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 406, 229–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aracena-Parks P., Goonasekera S. A., Gilman C. P., Dirksen R. T., Hidalgo C., Hamilton S. L. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 40354–40368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adachi T., Weisbrod R. M., Pimentel D. R., Ying J., Sharov V. S., Schöneich C., Cohen R. A. (2004) Nat. Med. 10, 1200–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Figtree G. A., Liu C. C., Bibert S., Hamilton E. J., Garcia A., White C. N., Chia K. K., Cornelius F., Geering K., Rasmussen H. H. (2009) Circ. Res. 105, 185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martínez-Ruiz A., Lamas S. (2007) Cardiovasc. Res. 75, 220–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.