Abstract

Background

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) hepatitis is a rare and potential life-threatening disease. The diagnosis of HSV hepatitis is hampered by its indifferent clinical presentation, which necessitates confirmatory laboratory data to identify HSV in the affected liver. However, liver biopsies are often contraindicated in the context of coagulopathy, are prone to sampling errors and have low sensitivity in mild HSV hepatitis cases. There is an unmet need for less-invasive diagnostic tools.

Methods

The diagnostic and therapeutic value of HSV DNA load and liver enzyme level kinetics was determined in five HSV hepatitis patients and twenty disease controls with HSV-DNAemia without hepatitis.

Results

At time of hospitalization, HSV hepatitis patients had a higher median (± interquartile range) HSV DNA load (6.0×106 ± 1.2×109) compared to disease controls (171 ± 2,845). Viral DNA load correlated with liver transaminase levels and disease severity. Antiviral treatment led to rapid decline of HSV DNA load and improvement of liver function of HSV hepatitis patients.

Conclusions

The data advocate the prompt and consecutive quantification of the HSV DNA load and liver enzyme levels in plasma of patients suspected of HSV hepatitis as well as those under antiviral treatment.

Keywords: Acute Liver Failure, Herpes simplex virus, Plasma Viral Load, Diagnosis, Follow-up

INTRODUCTION

Herpes simplex viruses (HSV) are endemic worldwide [1]. Whereas HSV-related diseases are generally limited to the oral, ocular and genital mucosa, HSV infection may disseminate to cause acute HSV hepatitis [1]. HSV hepatitis is a potentially life-threatening disease, characterized by abundant viral replication and liver cell necrosis [2–4]. Pathology is mainly due to the cytopathic effect of the virus [5–7]. Various host conditions (e.g., immunodeficiency and pregnancy) and viral factors (e.g., primary infection, high viral inoculum, HSV superinfection or infection with a hepatovirulent HSV strain) are considered to initiate and perpetuate HSV hepatitis pathology [8–11]. The mortality rates vary between 50% and 90%, depending on early diagnosis and prompt intervention with intravenous acyclovir (ACV iv) [11–14]. Unfortunately, only in about one-third of the HSV hepatitis cases reported in the literature definitive diagnosis was made ante-mortem [2–4]. Early diagnosis of HSV hepatitis is often complicated by the absence of specific clinical symptoms including mucocutaneous HSV lesions. Liver biopsies are considered the gold standard to diagnose HSV hepatitis, but are often contraindicated in the context of coagulopathy [2–4]. Moreover, the sensitivity of this assay is low and prone to sampling errors, especially in mild cases.

Less invasive and more sensitive and specific diagnostic tests are mandatory to diagnose and follow-up HSV hepatitis cases. HSV serology and detection of HSV DNA in plasma of suspected cases have been proposed [2–4, 15–17]. Whereas HSV serology is not informative in patients already infected with HSV, HSV-1 seroprevalence in adults is about 70% in developed countries [1], diagnostic HSV-specific PCR analyses on affected liver tissue and plasma samples of suspected HSV hepatitis cases are promising [2–4]. Thus far, only a few studies have addressed the applicability of quantitative HSV-specific PCR (qPCR) assays to diagnose HSV hepatitis and to determine the kinetics of HSV DNA load in blood in relation to liver enzyme levels, prognosis and development of clinical complications in HSV hepatitis patients [3,16–17]. Here, we report on the detailed diagnostic and clinical follow-up of five HSV hepatitis cases in relation to twenty disease controls with HSV DNAemia without hepatitis.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Sequential plasma samples were obtained for diagnostic purposes from 4 HSV hepatitis patients (patients 1 – 4), admitted to the Erasmus Medical Center (EMC; Rotterdam, Netherlands). Patient 5 was admitted to a hospital in the Seattle area (WA, US) and partly described in reference 17. Data from three additional Seattle HSV hepatitis patients [17] and data from four patients described in reference 3 were used for the calculation of the association between liver enzyme levels and HSV DNA loads. Non-hepatitis patients with active herpetic lesions and a detectable plasma HSV DNA load (n=20) were taken as disease controls at the EMC (supplementary Table 1). At the EMC and Seattle, hepatitis is suspected when the liver transaminase levels are >5-times the maximum reference value: AST (>250 U/ml) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT; >190 U/ml). The study was performed according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the local Ethical Committees and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects studied.

Isolation of nucleic acids and real-time PCR analyses

Nucleic acids were isolated from the plasma samples and liver biopsies using the MagnaPure LC Isolation station (Roche Applied Science, Almere, Netherlands). Quantitative PCR analyses for hepatitis B (HBV) and C virus (HCV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), HSV-1 and HSV-2 was performed on an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as described previously [18–20]. The methodology of DNA isolation and HSV-specific qPCR analyses on plasma samples of the Seattle patient group have been described previously [16,17].

Statistical analyses

Clinical and laboratory data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical software package (version 15; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Spearman’s rank correlation test was used to detect possible correlations between viral load and liver enzyme levels of the corresponding plasma samples. Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was used to compare the plasma HSV DNA loads between HSV hepatitis patients and disease controls. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The diagnostic and therapeutic value of combined HSV DNA-specific qPCR and liver enzyme level detection was determined in sequential plasma samples of the following 5 HSV hepatitis patients.

Patient 1

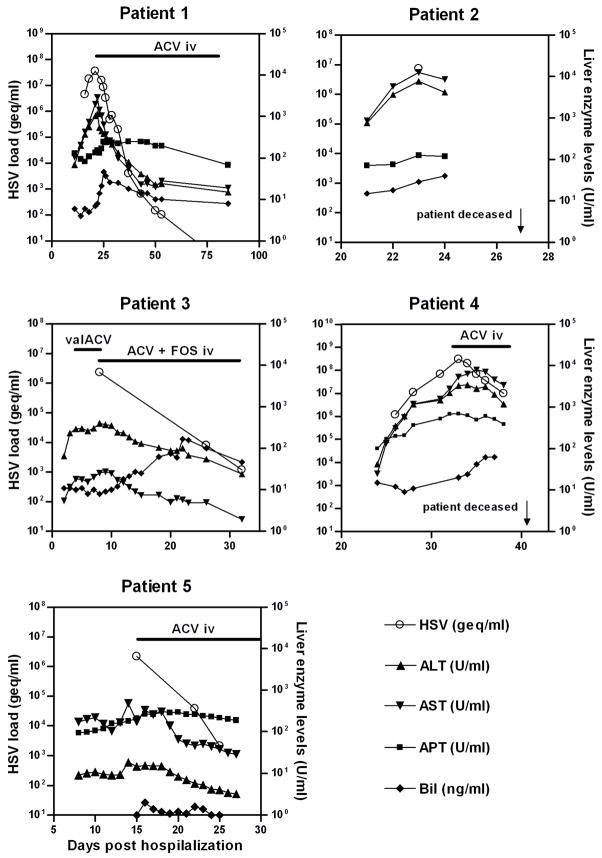

A 59-year-old woman was diagnosed with multiple myeloma IgD lambda (stage IIIA) and received autologous stem cell transplantation. Pre-transplant serology showed no antibodies to HBV, HCV and HSV. At day 11 post-transplantation, she developed high fever without localized symptoms. Laboratory analyses showed slightly elevated serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and C-reactive protein (CRP). PCR analyses on the patient’s plasma were negative for HBV, HCV, CMV, and EBV. In the days that followed, liver transaminase levels increased rapidly (Fig. 1). The patient developed acute liver failure, coagulopathy and became lethargic with one generalized seizure, but brain magnetic resonance imaging on day 20 showed no abnormalities. A percutaneous liver biopsy (day 22) showed necrotic lesions with signs of inflammation, but stained negative for HSV-1 and HSV-2 antigens. HSV-1 PCR analysis of the liver biopsy was positive (5,5×106 genome equivalents per ml; geq/ml), which confirmed the HSV hepatitis diagnosis. On day twenty-two, 3.5×107 HSV-1 geq/ml were detected in the patient’s plasma (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Kinetics of liver enzyme levels and HSV DNA load in blood of five patients with HSV hepatitis starting on the day of hospitalization. Liver enzymes (right y-axis) determined were aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase (APT), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). HSV load (left y-axis) represents HSV genome equivalent copies (geq) per ml. Start and end point of antiviral therapy are indicated with a horizontal bar. ACV iv, intravenous acyclovir; FOS, foscarnet; valACV, oral valacyclovir.

Starting at day 23, she was treated with ACV iv. Clinical symptoms initially worsened and foscarnet was additionally administered every 8 hours for 24 hours to account for the possibility of ACV-resistant HSV-1. During convalescence, the HSV-1 DNA load decreased about one 10-log every four days, liver enzyme levels dropped rapidly and clinical symptoms improved (Fig. 1).

Patient 2

A 72-year old man was diagnosed with pemphigus foliaceous. Despite prednisolone and azathioprine treatment the disease did not improve. Four weeks later, the patient was admitted with high fever and extensive blistering skin lesions on his arms, trunk and legs. At day 21, he had elevated serum AST, serum creatinine and CRP (Fig. 1). PCR analyses of the patient’s plasma did not demonstrate the presence of HBV, HCV, CMV and EBV, and no antibodies to HSV were detectable. Because drug-related liver toxicity was considered, azathioprine was discontinued and prednisolone was increased. The following day, both the skin swabs and plasma sample (7.5×106 geq/ml) were HSV-1 DNA positive (Fig. 1). Multiple organ failure ensued and the patient died on day 27. Post-mortem in situ analyses of the patient’s liver tissue showed multifocal coalescing severe acute coagulating necrosis with overt expression of HSV-1 antigens in hepatocytes (data not shown).

Patient 3

A 39-year old woman was diagnosed in 2002 with a progressive follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma. She had been in a complete remission, but in January 2006 progression of the lymphoma occurred in several lymph nodes and bone marrow. She received standard treatment followed by Rituximab and prednisolone. In September 2007 she presented with high fever and chills of unknown cause. On day 2 of hospitalization, physical examination revealed no abnormalities, but laboratory results showed elevated serum AST and CRP levels (Fig. 1). Plasma PCR analyses did not demonstrate the presence of HBV, HCV, CMV and EBV. The patient developed a HSV-1 ulcerative vulvo-vaginitis for which she was treated with valacyclovir. Three days later, plasma AST levels increased and the HSV-1 load was very high (2.3×106 geq/ml; Fig 1). Because HSV hepatitis was considered as a probable diagnosis, she received ACV iv in combination with foscarnet. A liver biopsy at day 12 showed focal necrosis without inflammation, but was complicated by hemobilia, necessitating cholecystectomy on day 19. PCR analysis of the liver biopsy was positive for HSV-1 DNA (3.5×104 geq/ml). Plasma HSV-1 DNA load and liver enzymes dropped within days and liver function normalized within 3 weeks after initiation of antiviral therapy (Fig. 1).

Patient 4

A 47-year old man was diagnosed in 2004 with neurological and pulmonary sarcoidosis and received prednisolone. On January 2008, he was hospitalized with cryptococcal meningitis and received amphotericin B and 5-flucytosine. On admission, he had a remarkable low CD4 T-cell count for which prednisolone was gradually reduced. Treatment was complicated by renal dysfunction and recurrent episodes of fever without positive viral and bacterial cultures. Four weeks after admission (Fig. 1; day 1) liver function started to deteriorate and he developed high fever. Because of potential toxicity, cotrimoxazole and 5-flucytosine prophylaxis was stopped. Plasma antibodies to HSV, HCV and HBV were undetectable. On day 32, qPCR analysis of plasma revealed a very high plasma HSV-1 DNA load (3×108 geq/ml) and ACV iv treatment was started immediately. The patient developed acute liver failure with hepatic encephalopathy, coagulopathy and renal failure. Shortly after start of ACV iv treatment, the clinical condition and liver functions improved along with a decline of HSV-1 DNA load in plasma (Fig. 1). However, on day 42 the patient died due to multi-organ failure. Postmortem liver histopathology demonstrated extended patchy and azonal liver tissue necrosis. Analogous to patient 2, the affected liver sections were HSV-1 antigen positive and lacked inflammatory cell infiltrates (data not shown).

Patient 5

A 61 year-old female with history of peptic ulcer presented with abdominal pain and was discharged with the diagnosis of Ileus after a two day hospital stay. She returned two days later with high fever, chills, dysuria, cervical motion tenderness and bilateral flank pain and was admitted to the hospital with presumed pelvic inflammatory disease and was started on cefotetan and doxycycline. However, her fever, abdominal pain, and tachycardia persisted on antibiotics. Vulvar lesions were detected that were not thought, at the time, to be consistent with herpetic lesions. Serum antibodies to CMV and HSV were negative. On day 8 she developed a transaminitis and contrast nephropathy. Her CT scan was remarkable for borderline splenomegaly and pericholecystic fluid collection. On day 15, serum HSV DNA levels of 2.2×106 geq/ml were detected (Fig. 1). Vulvar viral cultures were positive for HSV-2. She was initiated on ACV iv. Shortly after initiation of ACV therapy her fever rapidly defervesced, her liver function normalized, and viral load sharply dropped. She continues on prophylactic dosing of valacyclovir (Fig. 1).

Liver enzyme levels correlate with HSV DNA load in plasma

The daily blood sampling of the HSV hepatitis patients facilitated detailed analyses of the viral load and liver enzyme kinetics during the course of disease. To increase the statistical power, analogous data of 7 previously reported HSV hepatitis patients were included [3,17]. In comparison, data of control patients with HSV-DNAemia without hepatitis (n=20) were included. The characteristics and clinical data of the latter patient cohort are summarized in supplementary Table 1.

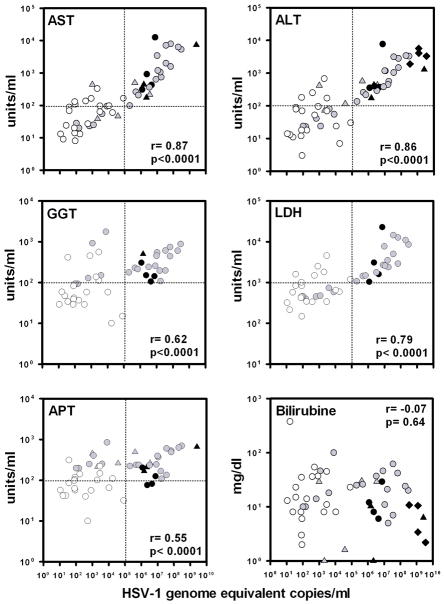

The median plasma HSV DNA load of the HSV hepatitis patients [(6.0×106, ranged between 1.2×106 to 3.6×109 geq/ml) (n=12 HSV hepatitis patients; admitted to the EMC (n=4), Seattle area (n=4) and the 4 HSV hepatitis patients described in reference 3], obtained at the earliest time point post-hospitalization, was significantly higher compared to disease controls (171; range 11 to 81,957geq/ml) (p<0.0001). The plasma HSV DNA loads, combined from both the HSV hepatitis patients and disease control groups, correlated significantly with the respective levels of AST (r=0.87, p<0.0001), ALT (r=0.86, p<0.0001), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT; r=0.62, p<0.0001), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; r=0.79, p<0.0001) and alkaline phosphatase (APT; r=0.55, p<0.0001), but not the bilirubin levels (r=−0.070, p=0.64) (Fig. 2). Notably, the HSV DNA and liver enzyme data clustered according to disease entity, providing potential diagnostic cut-off values of plasma HSV DNA load (provisionally set at >105 geq/ml) and liver enzyme levels (e.g., AST, ALT, GGT and APT levels provisionally set at >102 U/ml) applicable to diagnose HSV hepatitis cases in the acute stage of disease (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Liver enzyme levels correlate with HSV DNA load in plasma. Data shown are the HSV DNA load and corresponding liver enzyme levels recorded at the earliest time point of hospitalization of HSV hepatitis patients (n= 12; black symbols) and the peak levels of disease controls (n=20; white dots). The data represent the combination of HSV hepatitis patients recruited in Rotterdam (Netherlands; n=4, dots) and Seattle (n=4, triangles; partially described in references 16 and 17), and HSV hepatitis patients described in reference 3 (n=4, diamonds). The gray symbols represent data of the same HSV hepatitis patients during follow-up. The Spearman’s rank correlation test was used to determine the correlation between HSV DNA load and liver enzymes. Abbreviations: AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase levels (LDH), APT, alkaline phosphatase; and Bil, bilirubin.

DISCUSSION

Acute liver failure is a life-threatening disease commonly due to acetaminophen toxicity, autoimmune reactions, metabolic diseases or viruses including hepatitis A and B, as well as HSV [21,22]. HSV hepatitis is very rare and comprises less than 1% of all acute liver failures [15,23]. The clinical course of HSV hepatitis is rapid, relentless, and frequently fatal. The lethality rates of HSV hepatitis are between 50% and 90%; mainly because of delayed diagnosis and instituting specific treatment, thus arguing for rapid and specific diagnostic laboratory tests to identify HSV hepatitis patients promptly [2–4].

The current study consolidates the diagnostic value of HSV qPCR analyses on blood samples of patients with acute liver failure suspected of HSV hepatitis [3,16,17]. To our knowledge, the largest HSV hepatitis case series analyzed by HSV qPCR. The significant correlation between the plasma HSV DNA load and liver enzyme levels are in line with the histopathologic findings on affected liver tissue of HSV hepatitis patients, emphasizing the pivotal role of the viral cytopathic effect in HSV hepatitis pathogenesis [5–7]. The inclusion of disease controls provided comparative data to identify HSV hepatitis patient-specific viral and liver enzyme values that can be applied for differential diagnosis of HSV hepatitis. The HSV hepatitis patients had a higher median (± interquartile range) HSV DNA load (6.0×106 ± 1.2×109) compared to disease controls (171 ± 2,845). Moreover, HSV DNA peak levels in the HSV hepatitis patients were always >106 HSV geq/ml, but did not exceed 105 HSV geq/ml in the disease controls even though the vast majority of the latter cohort was severely immunocompromised (supplementary Table 1).

Based on the data presented we propose that HSV DNA loads of >105 geq/ml, combined with AST, ALT, GGT and APT levels of >102 U/ml, and LDH levels of >103 U/ml in plasma of patients with acute liver failure are highly indicative for HSV hepatitis and merits prompt life-saving ACV iv treatment. The early diagnosis of the five HSV hepatitis patients presented was hindered by the absence of HSV IgG and IgM, limited or nonspecific mucocutaneous HSV lesions (patients 1 and 4) and negative HSV immunohistology of an ante-mortem liver biopsy (patient 1). We anticipate that performing HSV qPCR analyses of plasma samples, obtained at the earliest time point post-hospitalization, would have expedited the differential diagnosis and subsequent treatment of the HSV hepatitis patients. Moreover, the general availability of qPCR technology will eventually reduce the need for a diagnostic liver biopsy in patients with liver failure and coagulopathy. Indeed, bleeding complicated the liver biopsies in two of five HSV hepatitis patients (patients 1 and 3).

In addition to its applicability to diagnose HSV hepatitis, HSV qPCR was of additive value to monitor the effectiveness of antiviral therapy. In the ACV-treated HSV hepatitis patients, viral loads decreased about 0.5 log within one day after the initiation of antiviral therapy (Fig. 1). Whereas the data underscore the improved outcomes of HSV hepatitis patients on ACV iv treatment [11–14], prolonged ACV administration may select for ACV resistant HSV and subsequent treatment failure [24]. The prevalence of acyclovir resistant HSV is rare in immunocompetent individuals (0.1%–0.7%), but more common in those who are immunocompromised (4%–14%) [24–25]. In 1 of 5 of the HSV hepatitis patients ACV resistance was suspected. In patient 1, the HSV DNA load increased and clinical symptoms worsened despite ACV iv treatment. ACV resistance was considered and foscarnet therapy was provided successfully (Fig. 1). However, neither the HSV-1 isolates cultured from the patient’s blood nor skin lesions were ACV resistant (data not shown). Two HSV hepatitis cases involving ACV resistant HSV that eventually resulted in ACV refractory disease and death have been described in the literature [13,16]. Consecutive quantification of the HSV DNA load and liver enzyme levels in plasma of ACV-treated HSV hepatitis patients would promptly identify those with ACV refractory disease so that they can be switched to alternative anti-HSV drugs like foscarnet and cidovovir [26].

In conclusion, the data indicate that quantification of HSV DNA levels in plasma is a fast, sensitive and specific test to differentially diagnose HSV hepatitis in patients with acute liver failure. We anticipate that HSV qPCR assays will reduce the need for diagnostic liver biopsies and can be applied to monitor the efficacy of antiviral therapy and development of antiviral resistance. Prospective studies are needed to generate a larger laboratory data set of HSV hepatitis patients, necessary to define diagnostic and prognostic plasma HSV DNA load and liver enzyme cut-off values to diagnose and treat HSV hepatitis patients more efficiently in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was in part supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant K08 AI080952 01A1 to W.R.B.).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors do not have a commercial or other association that might pose a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Roizman B, Knipe DM, Whitley RJ. Herpes simplex virus. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields virology. 5. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 2502–2557. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norvell JP, Blei AT, Jovanovic BD, Levitsky J. Herpes simplex virus hepatitis: an analysis of the published literature and institutional cases. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1428–1434. doi: 10.1002/lt.21250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levitsky J, Duddempudi AT, Lakeman FD, et al. Detection and diagnosis of herpes simplex virus infection in adults with acute liver failure. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:1498–1504. doi: 10.1002/lt.21567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riediger C, Sauer P, Matevossian E, Müller MW, Büchler P, Friess H. Herpes simplex virus sepsis and acute liver failure. Clin Transplant. 2009;21:37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halliday J, Lokan J, Angus PW, Gow P. A case of fulminant hepatic failure in pregnancy. Hepatology. 2010;51:341–342. doi: 10.1002/hep.23372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakhan SE, Harle L. Fatal fulminant herpes simplex hepatitis secondary to tongue piercing in an immunocompetent adult: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2008;2:356. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duckro AN, Sha BE, Jakate S, et al. Herpes simplex virus hepatitis: expanding the spectrum of disease. Transpl Infect Dis. 2006;8:171–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2006.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyazaki Y, Akizuki S, Sakaoka H, Yamamoto S, Terao H. Disseminated infection of herpes simplex virus with fulminant hepatitis in a healthy adult. A case report. APMIS. 1991;99:1001–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1991.tb01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitley R, Lakeman AD, Nahmias A, Roizman B. DNA restriction-enzyme analysis of herpes simplex virus isolates obtained from patients with encephalitis. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1060–1062. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198210213071706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dix RD, McKendall RR, Baringer JR. Comparative neurovirulence of herpes simplex virus type 1 strains after peripheral or intracerebral inoculation of BALB/c mice. Infect Immun. 1983;40:103–112. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.1.103-112.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montalbano M, Slapak-Green GI, Neff GW. Fulminant hepatic failure from herpes simplex virus: post liver transplantation acyclovir therapy and literature review. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:4393–4396. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shanley CJ, Braun DK, Brown K, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure secondary to herpes simplex virus hepatitis. Successful outcome after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1995;59:145–149. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199501150-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longerich T, Eisenbach C, Penzel R, et al. Recurrent herpes simplex virus hepatitis after liver retransplantation despite acyclovir therapy. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1289–1294. doi: 10.1002/lt.20567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters DJ, Greene WH, Ruggiero F, McGarrity TJ. Herpes simplex-induced fulminant hepatitis in adults: a call for empiric therapy. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:2399–2404. doi: 10.1023/a:1005699210816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ichai P, Roque Afonso AM, Sebagh M, et al. Herpes simplex virus-associated acute liver failure: a difficult diagnosis with a poor prognosis. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1550–1555. doi: 10.1002/lt.20545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czartoski T, Liu C, Koelle DM, Schmechel S, Kalus A, Wald A. Fulminant, acyclovir-resistant, herpes simplex virus type 2 hepatitis in an immunocompetent woman. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1584–1586. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.4.1584-1586.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berrington WR, Jerome KR, Cook L, Wald A, Corey L, Casper C. Clinical correlates of herpes simplex virus viremia among hospitalized adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1295–1301. doi: 10.1086/606053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Doornum GJ, Guldemeester J, Osterhaus AD, Niesters HG. Diagnosing herpesvirus infections by real-time amplification and rapid culture. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:576–580. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.2.576-580.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pas SD, Fries E, De Man RA, Osterhaus AD, Niesters HG. Development of a quantitative real-time detection assay for hepatitis B virus DNA and comparison with two commercial assays. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2897–2901. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.8.2897-2901.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schutten M, Fries E, Burghoorn-Maas C, Niesters HG. Evaluation of the analytical performance of the new Abbott RealTime RT-PCRs for the quantitative detection of HCV and HIV-1 RNA. J Clin Virol. 2007;40:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoofnagle JH, Carithers RL, Jr, Shapiro C, Ascher N. Fulminant hepatic failure: summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 1995;21:240–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiødt FV, et al. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:947–954. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-12-200212170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schiødt FV, Davern TJ, Shakil AO, McGuire B, Samuel G, Lee WM. Viral hepatitis-related acute liver failure. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:448–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.t01-1-07223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bacon TH, Levin MJ, Leary JJ, Sarisky RT, Sutton D. Herpes simplex virus resistance to acyclovir and penciclovir after two decades of antiviral therapy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:114–128. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.114-128.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danve-Szatanek C, Aymard M, Thouvenot D, et al. Surveillance network for herpes simplex virus resistance to antiviral drugs: 3-year follow-up. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:242–249. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.1.242-249.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbert C, Bestman-Smith J, Boivin G. Resistance of herpesviruses to antiviral drugs: clinical impacts and molecular mechanisms. Drug Resist Updat. 2002;5:88–114. doi: 10.1016/s1368-7646(02)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.