Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Conditional gene targeting has been extensively used for in vivo analysis of gene function in β-cell biology. The objective of this study was to examine whether mouse transgenic Cre lines, used to mediate β-cell– or pancreas-specific recombination, also drive Cre expression in the brain.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Transgenic Cre lines driven by Ins1, Ins2, and Pdx1 promoters were bred to R26R reporter strains. Cre activity was assessed by β-galactosidase or yellow fluorescent protein expression in the pancreas and the brain. Endogenous Pdx1 gene expression was monitored using Pdx1tm1Cvw lacZ knock-in mice. Cre expression in β-cells and co-localization of Cre activity with orexin-expressing and leptin-responsive neurons within the brain was assessed by immunohistochemistry.

RESULTS

All transgenic Cre lines examined that used the Ins2 promoter to drive Cre expression showed widespread Cre activity in the brain, whereas Cre lines that used Pdx1 promoter fragments showed more restricted Cre activity primarily within the hypothalamus. Immunohistochemical analysis of the hypothalamus from Tg(Pdx1-cre)89.1Dam mice revealed Cre activity in neurons expressing orexin and in neurons activated by leptin. Tg(Ins1-Cre/ERT)1Lphi mice were the only line that lacked Cre activity in the brain.

CONCLUSIONS

Cre-mediated gene manipulation using transgenic lines that express Cre under the control of the Ins2 and Pdx1 promoters are likely to alter gene expression in nutrient-sensing neurons. Therefore, data arising from the use of these transgenic Cre lines must be interpreted carefully to assess whether the resultant phenotype is solely attributable to alterations in the islet β-cells.

In vivo analysis of gene function in the pancreas and β-cells has benefited from the development of mouse lines expressing Cre in all pancreatic compartments or restricted to the islet β-cells. The choice of promoter to drive recombinase expression is critical for controlling the location and timing of gene activity. In addition, inducible versions of Cre recombinase, e.g., CreER, allow temporal control to the manipulation of gene activity, which becomes important when analyzing gene function at specific embryonic and adult stages (1,2). Promoters of the pancreas duodenal homeobox 1 (Pdx1) (3,4) and insulin (Ins1 and Ins2) (5–8) genes have been well characterized to allow the use of regulatory sequences for directing Cre expression to specific pancreatic cell populations. Commonly used transgenic mouse lines that employ rat Ins2 gene promoter sequences to drive Cre expression within the β-cell population include Ins2-Cre/RIP-Cre [Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI): Tg(Ins2-cre)25Mgn and Tg(Ins2-cre)1Herr] (9–11) and RIP-CreER [MGI: Tg(Ins2-cre/Esr1)1Dam] (12). Pdx1 gene promoter sequences have proven useful for directing Cre expression throughout the early pancreatic epithelium (4,10,13,14) and to the endocrine cells of the pancreas (15). The Pdx1 gene is expressed early in pancreas development throughout the endoderm of the dorsal and ventral buds, but expression becomes restricted during development such that high levels of Pdx1 are maintained in the insulin-producing β-cells with lower levels in subpopulations of acinar cells (8,16). Examples of Pdx1-Cre transgenic lines include Pdx1-Creearly [MGI: Tg(Pdx1-cre)89.1Dam] (13), Pdx1-Crelate [MGI: Tg(Ipf1-cre/Esr1)1Dam/Mmcd] (10), Pdx1-Cre [MGI: Tg(Ipf1-cre)1Tuv] (14), and Pdx1-CreER [MGI: Tg(Pdx1-cre/ERT)1Mga] (15).

To assess the specificity of recombination and perform lineage tracing analysis, reporter lines such as the ROSA26-stop-lacZ [MGI: Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1Sho], also known as R26R (17), or the ROSA26-stop-YFP [MGI: Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(EYFP)Cos] (18) mice have been developed. Upon Cre-mediated recombination, these reporter lines activate expression of a β-galactosidase (β-gal) or a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) reporter under the control of the ubiquitously active ROSA26 promoter, resulting in expression that is stably inherited by all cell progeny regardless of their differentiation fate.

Here we show that most Cre lines currently being used to mediate pancreas or β-cell recombination also direct Cre expression to areas of the brain, and this may lead to altered gene expression in nutrient-sensing neurons that affects nutrient homeostasis.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Mouse models.

Transgenic Cre and R26R reporter mouse lines used in this study are listed in Table 1. Experimental animals were generated by crossing Tg(Ins2-cre)25Mgn (termed RIP-CreMgn) (11), Tg(Ins2-cre)1Herr (termed RIP-CreHerr) (10), Tg(Ins2-creEsr1)1Dam (termed RIP-Cre/ERT) (12), Tg(Pdx1-cre)89.1Dam (termed Pdx1-CreDam) (13), Tg(Ipf1-cre)1Tuv (termed Pdx1-CreTuv) (14), Tg(Pdx1-cre/ERT)1Mga (termed Pdx1AI-III-Cre/ERT) (15), or Tg(Ins1-cre/ERT)1Lphi (termed MIP-Cre/ERT) (Tamarina et al., unpublished data) transgenic lines with a reporter strain expressing either lacZ Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1Sor (termed R26Rwt/lacZ) (17,19) or enhanced YFP Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(EYFP)Cos (termed R26Rwt/YFP) (18). Both R26R reporter strains on C57BL/6 background were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Pdx1tm1Cvw mice (16) on B6D2 F1 background were obtained from Dr. C.V. Wright (Vanderbilt University). Complete details of the sources for all mouse strains used in this study are listed in supplementary Table 1 (available at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/content/full/db10-0624/DC1). For timed pregnancies, noon on the day of the vaginal plug was considered embryonic day 0.5 (e0.5). All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the relevant institutions.

TABLE 1.

Mouse transgenic Cre and R26R reporter lines used in this study

| MGI nomenclature | Synonym used in this report | Institution using this reporter | Transgene promoter fragment or gene locus | Original reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tg(Ins2-cre)25Mgn | RIP-CreMgn | Chicago | Rat insulin 2–668 bp distal to transcriptional start | (11) |

| Vanderbilt | ||||

| Tg(Ins2-cre)1Herr | RIP-CreHerr | Vanderbilt | Rat insulin 2–660 bp from transcriptional start | (10) |

| Tg(Ins2-creEsr1)1Dam | RIP-Cre/ERT | Chicago | Rat insulin 2–668 bp fragment + hsp68 | (12) |

| Tg(Ins1-cre/ERT)1Lphi | MIP-Cre/ERT | Chicago | Mouse insulin 1–8,500 bp from transcriptional start | Tamarina et al. (in preparation) |

| Tg(Pdx1-cre)89.1Dam | Pdx1-CreDam | Michigan | Mouse Pdx1–5,500 bp from transcriptional start | (13) |

| Vanderbilt | ||||

| Tg(Ipf1-cre)1Tuv | Pdx1-CreTuv | Vanderbilt | Mouse Pdx1–4,300 bp from transcriptional start | (14) |

| Tg(Pdx1-cre/ERT)1Mga | Pdx1AI-III-Cre/ERT | Chicago | Mouse Pdx1–1 kb fragment (∼2 kb from transcriptional start) + hsp68 promoter | (15) |

| Vanderbilt | ||||

| Pdx1tm1Cvw | Pdx1wt/lacZ | Vanderbilt | Targeted inactivation | (16) |

| Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(EYFP)Cos | R26RYFP | Vanderbilt | Targeted insertion into the Gt(ROSA)26Sor locus | (18) |

| Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1Sor | R26RlacZ | Chicago | Targeted insertion into the Gt(ROSA)26Sor locus | (19) |

| Michigan | ||||

| Vanderbilt |

Reagents.

Primary antibodies included guinea pig anti-porcine insulin IgG (1:500; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), guinea pig anti-insulin antibody (1:1,000; Millipore, Billerica, MA), rabbit anti–β-gal IgG (1:5,000; MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH), goat anti–β-gal IgG (1:1,000; Biogenesis Ltd, Poole, UK), rabbit anti-STAT3 phosphorylation (pSTAT3) IgG (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technologies, Beverly, MA), rabbit anti-orexin IgG (1:2,000; Calbiochem, EMD Biosciences/Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and rabbit anti-Cre antibody (1:1,000, cat. #69050; EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA) and Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Recombinant mouse leptin was obtained from the National Hormone and Peptide Program (Los Angeles, CA).

Tamoxifen administration.

Over a 5-day period, mice were injected subcutaneously or intraperitoneally with 3 doses of 1–8 mg tamoxifen (Sigma, T5648) freshly dissolved in corn oil (Sigma, C8267) at 10 mg/ml, 20 mg/ml, or corn oil vehicle. The subcutaneous injection site was sealed with a drop of Vetbond tissue adhesive (3M). Following tamoxifen administration, the mice were housed individually for 5–10 days before being analyzed for Cre-recombinase–mediated activity.

Detection of β-gal activity.

β-Gal activity was detected by 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-gal) staining as described previously (20) with slight modifications. Briefly, pancreata and brains were dissected in ice-cold 10 mmol/l PBS and fixed in freshly prepared 1–2% paraformaldehyde for either 2–4 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Brains (2-mm slices) and pancreata were permeabilized for 5 h in 2 mmol/l MgCl2, 0.01% sodium deoxycholate, 0.02% NP-40, 10 mmol/l PBS, and then stained overnight in the dark in 2 mmol/l MgCl2, 5 mmol/l potassium ferricyanide, 5 mmol/l potassium ferrocyanide, 1 mg/ml X-gal, 0.01% sodium deoxycholate, 0.02% NP-40, 10 mmol/l PBS pH 7.4 at ambient temperature or 37°C. Tissues were washed in PBS, postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h, washed in PBS, and placed into 70% ethanol prior to whole mount imaging. For YFP detection, embryos were dissected at e15.5 and imaged in whole mount.

Leptin administration.

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with leptin (5 mg/kg) or vehicle (PBS) and then rested for 2 h prior to perfusion.

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunodetection of pancreatic Cre expression was performed in 5-μm paraffin sections prepared from paraformaldehyde-fixed pancreata of RIP-CreMgn, RIP-Cre/ERT, Pdx1AI-III-Cre/ERT, and MIP-Cre/ERT mice. Transgenic lines expressing Cre/ERT received the third dose of tamoxifen on the day prior to being killed. After antigen retrieval, sections were incubated with primary antibodies to Cre and insulin (Millipore). For immunodetection of β-gal expression in the brain, mice were perfusion-fixed, and brains were removed and postfixed overnight as described previously (21). Following cryoprotection, brains were sectioned into 30-μm coronal slices, collected in four consecutive series, and stored at −20°C. Sections were then incubated with primary antibodies to pSTAT3, β-gal (Biogenesis), or orexin overnight at 4°C. Immunolabeling was visualized with appropriate fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies. Digital images were acquired by confocal microscopy. One-way ANOVA analysis was used to compare the percent of β-cells that express Cre in the islets of the different transgenic lines.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Islets (22) and hypothalamus were isolated from adult Tg(Pdx1-cre)89.1Dam (13) mice and their controls. Total cellular RNA was isolated using the RNAqueous Small Scale Phenol-Free Total RNA isolation kit (Ambion, Austin, TX), and trace contaminating DNA was removed with the TURBO DNA-free kit (Ambion). High-quality RNA had a 28S–to–18S ratio from 1.2 to 2.0 and an RNA integrity number from 8.2 to 8.9. Single-stranded cDNA was generated by reverse transcription from 180-ng total RNA using the Superscript III First Strand Synthesis kit (Invitrogen). cDNA (40 ng/reaction) was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR using the ABI Prism 7900 Sequence Detection System and POWER SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Samples were analyzed in duplicates, and relative cDNA levels were determined by comparing cycle threshold values of Cre cDNA to Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) cDNA. Samples with cycle threshold values greater than 40 were considered to have undetectable amounts of template. Primer sequences were the following; Cre (5′TGCAACGAGTGATGAGGTTC3′ and 5′GCAAACGGACAGAAGCATTT3′), HPRT (5′TACGAGGAGTCCTGTTGATGTTGC3′ and 5′GGGACGCAGCAACTGACATTTCTA3′), and Pdx1 (5′CTGAGGGACAAAGATGCAGA3′ and 5′TTCTAATTCAGGGCGTTGTG3′). One-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison tests were used to compare outcomes in mice of different genotypes. Data were expressed as mean ± SE.

RESULTS

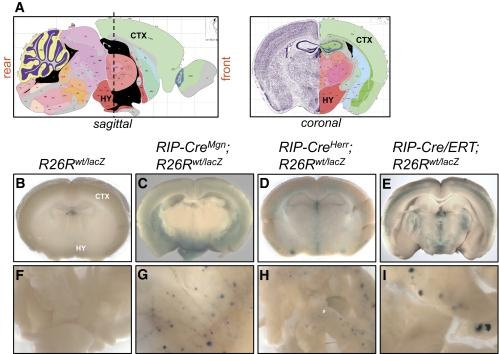

Using the R26R reporter line, the RIP-CreMgn line (11) was previously shown to have robust Cre-mediated recombination within the β-cells and the ventral brain during development (9). To investigate whether Cre-mediated recombination occurred within the brain of other transgenic Cre lines using the rat Ins2 or Pdx1 promoter (Table 1), these mouse strains were crossed with the R26R reporter strain and analyzed for β-gal activity in whole mount brain slices (Figs. 1 and 2). No X-gal staining was detected in the brain or pancreas from control R26Rwt/lacZ littermates indicating that β-gal is not expressed in the absence of Cre activity (Fig. 1B and F and supplementary Fig. 1). In RIP-CreMgn;R26Rwt/lacZ mice, widespread X-gal staining was detected in most brain areas with robust expression in the mid-brain and ventral regions, which was consistent with previous reports (9) (Fig. 1C and supplementary Fig. 2). In the brains of RIP-CreHerr;R26Rwt/lacZ mice, X-gal staining was less widespread and had a more punctate pattern without any obvious regionalization (Fig. 1D and supplementary Fig. 3). The brains of RIP-Cre/ERT;R26Rwt/lacZ mice with Cre activity induced by three 2-mg doses of tamoxifen revealed a diffuse intermediate pattern of X-gal staining that was more extensive than in RIP-CreHerr;R26Rwt/lacZ mice but less than in RIP-CreMgn;R26Rwt/lacZ mice (Fig. 1E and supplementary Fig. 4). All three transgenic lines, RIP-CreMgn, RIP-CreHerr, and RIP-Cre/ERT, showed a high level of recombination in pancreatic islets (Fig. 1G–I and supplementary Figs. 2–4).

FIG. 1.

RIP-Cre transgenic lines display Cre-mediated recombination in multiple regions of the brain. Adult brains were sliced into four or five coronal sections and subjected to whole mount X-gal staining. Images of individual brain slices from each sectioning plane are available in supplementary Figs. 1–4. A: Sagittal and coronal views of mouse brain (adapted from Allen Mouse Brain Atlas, http://www.brain-map.org/) (29). A dashed vertical line marks coronal sectioning plane spanning the hypothalamic region of the brain. B–E: Images of coronal brain slices located on the left side of the sectioning plane in the sagittal view in A. B: R26Rwt/lacZ littermate control mice (n = 17) lacked X-gal staining in the brain. The cortex (CTX) and hypothalamus (HY) are labeled and correspond to regions marked on the coronal view in A. C: RIP-CreMgn;R26Rwt/lacZ mice (n = 8) showed X-gal staining throughout the brain with high signal intensity in the mid-brain and ventral regions. D: RIP-CreHerr;R26Rwt/lacZ mice (n = 14) showed weaker, punctate X-gal staining throughout the brain without obvious regionalization. E: RIP-Cre/ERT;R26Rwt/lacZ mice (n = 4) injected intraperitoneally with three 2-mg doses of tamoxifen over a 5-day period displayed strong, punctate X-gal staining throughout the brain with expression pattern more restricted than in RIP-CreMgn; R26Rwt/lacZ mice. Brains from littermate controls injected with corn oil vehicle were negative for X-gal staining (data not shown). F–I: Whole-mount X-gal staining of pancreas from R26Rwt/lacZ in F, RIP-CreMgn; R26Rwt/lacZ in H, RIP-CreHerr;R26Rwt/lacZ in G, and RIP-Cre/ERT;R26Rwt/lacZ mice in I. (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

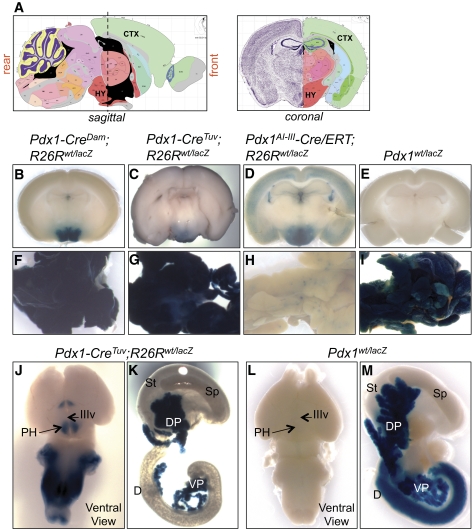

FIG. 2.

Pdx1-Cre transgenic lines show localized Cre-mediated recombination within specific regions of the brain including the hypothalamus. Adult brains were sliced, labeled, and imaged as described in Fig. 1. Images of individual brain slices from each sectioning plane are available in supplementary Figs. 5–7 and supplementary Fig. 9. A: Sagittal and coronal views of mouse brain. A dashed vertical line marks coronal sectioning plane spanning hypothalamic region of the brain. B–D: Images of coronal brain slices located on the left side of sectioning plane in the sagittal view in A. The schematics of the mouse brain are from the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas (http://www.brain-map.org/) (29). B: X-gal staining in Pdx1-CreDam;R26Rwt/lacZ brain (n = 7) was localized to the brain stem and hypothalamus. C: X-gal positive cells in Pdx1-CreTuv;R26Rwt/lacZ brain (n = 4) were localized to hypothalamic region. D: Adult Pdx1AI-III-Cre/ERT;R26Rwt/lacZ mice (n = 4) were injected subcutaneously with three 8-mg doses of tamoxifen (right panel) and analyzed for lacZ expression. X-gal staining had a broader punctate pattern with high-intensity signal localized to the hypothalamic region. Brains from littermate controls injected with corn oil vehicle (n = 2) were negative for X-gal staining (data not shown). E: Brains from adult Pdx1lacZ/wt mice (n = 4) were negative for X-gal staining. F–I: Whole-mount X-gal staining of pancreas from Pdx1-CreDam;R26Rwt/lacZ in F, Pdx1-CreTuv;R26Rwt/lacZ in G, Pdx1AI-III-Cre/ERT;R26Rwt/lacZ mice in H, and Pdx1lacZ/wt mice in I. J and K: Brains from Pdx1-CreTuv;R26Rwt/lacZ embryos at e15.5 (n = 6) in J were analyzed for LacZ expression. X-gal staining indicated expression of Pdx1-CreTuv transgene in the brain stem and ventral region of the brain that gives rise to the hypothalamus (arrows). Pancreas in K had expected X-gal staining. Similar results were obtained using the R26RYFP reporter strain in supplementary Fig. 8. Brain and pancreas from R26Rwt/lacZ (n = 5) and R26Rwt/YFP (n = 6) e15.5 controls were negative for X-gal staining and YFP fluorescence, respectively (supplementary Fig. 8). L and M: Brains from e15.5 Pdx1lacZ/wt embryos (n = 7) in L were negative for X-gal staining, while pancreas showed expected X-gal positivity in M. In e15.5 Pdx1wt/wt embryos (n = 10), both brain and pancreas were X-gal negative (supplemental Fig. 9). CTX, cortex; D, duodenum; DP, dorsal pancreas; HY, hypothalamus; IIIv, third ventricle; PH, posterior hypothalamic region; Sp, spleen; St, stomach; VP, ventral pancreas. (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

Cre-mediated recombination within the brain of Pdx1-Cre transgenic lines has not been examined, but ectopic recombination was reported in the pharyngeal region of Pdx1-CreDam;R26Rwt/lacZ embryos (23). Unlike the widespread recombination in brains from RIP-Cre transgenic lines, X-gal staining in Pdx1-CreDam;R26Rwt/lacZ brains (Fig. 2B and supplementary Fig. 5) and Pdx1-CreTuv;R26Rwt/lacZ brains (Fig. 2C and supplementary Fig. 6) was localized primarily to the hypothalamus and brain stem. Analysis of Cre mRNA by quantitative RT-PCR in the Pdx1-CreDam line confirmed expression in the hypothalamus with levels of hypothalamic expression 12.6-fold lower than in islets (supplemental Fig. 5). Pdx1AI-III-Cre/ERT transgenic mice express the tamoxifen-inducible Cre (15). Injection of a single dose of tamoxifen into pregnant females (2 mg/40 g body weight) at e16.5 did not result in recombination in the brains of Pdx1AI-III-Cre/ERT;R26Rwt/lacZ embryos dissected at e20.5 (15). In adult Pdx1AI-III-Cre/ERT;R26Rwt/lacZ mice injected with three 1-mg doses of tamoxifen, recombination was detected mainly in the hypothalamus (supplementary Fig. 7, left panel). However, three 8-mg doses of tamoxifen induced much broader recombination throughout the brain, suggesting that the extent of recombination in the adult brain is dependent upon the tamoxifen dose (Fig. 2D and supplementary Fig. 7, right panel). These data suggest that the Pdx1AI-III-Cre/ERT transgene is expressed in the adult brain but not in the e16.5 brain, although it is possible that higher tamoxifen levels may be needed to induce Cre-mediated recombination within the embryonic brain.

To further examine the timing of Cre expression in the brains of the Pdx1-Cre lines expressing constitutively active Cre, we studied the Pdx1-CreTuv transgenic line crossed into either R26RlacZ/lacZ or R26RYFP/YFP reporter mice and analyzed embryos at e15.5 (Fig. 2J–K and supplementary Fig. 8). Both reporter strains demonstrated Cre activity in the brain stem and ventral region of the developing brain that gives rise to the hypothalamus, indicating that functional Cre protein is expressed in the ventral region of the Pdx1-CreTuv brain prior to e15.5.

To determine whether Cre activity in the hypothalamus of the three different Pdx1-Cre transgenes was due to previously unrecognized endogenous Pdx1 expression, a mouse line with a lacZ reporter cassette in the Pdx1 locus was examined (16). Both adult and embryonic (e15.5) Pdx1wt/lacZ (Fig. 2E and L and supplementary Fig. 9) brains were negative for X-gal staining. Furthermore, expression of the endogenous Pdx1 gene was undetectable in the hypothalamus by real-time RT-PCR (data not shown) indicating that Pdx1-CreDam, Pdx1-CreTuv, and Pdx1AI-III-Cre/ERT transgenes are ectopically expressed in the brain.

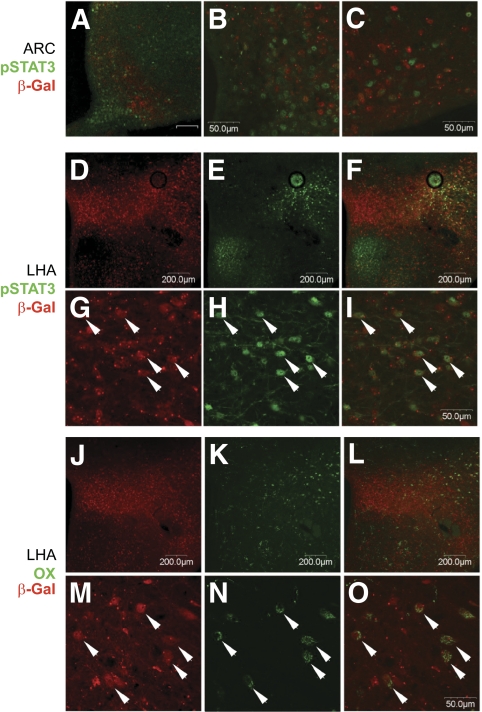

Detection of Cre-mediated recombination in the hypothalamus of Pdx1-CreDam;R26Rwt/lacZ mice (Fig. 2B, supplementary Fig. 5, and supplementary Fig. 10) raised the possibility that Cre protein may be expressed in neurons involved in the regulation of energy and glucose homeostasis. To determine the extent of Cre-mediated recombination within these specific neuronal populations, β-gal positive cells in brain sections from leptin-treated Pdx1-CreDam;R26Rwt/lacZ mice were co-localized with orexin and leptin-induced pSTAT3, respectively. In the lateral hypothalamus, β-gal protein was expressed in a complex pattern that partially overlapped with both the orexin-expressing and LepRb-expressing neuronal populations (Fig. 3), although significant populations of β-gal positive cells did not overlap with the neuronal cell population in either the lateral hypothalamus or in other hypothalamic regions including the arcuate nucleus. Nonetheless, these data clearly illustrate that the Pdx1-CreDam line induces Cre-mediated recombination in subpopulations of hypothalamic neurons involved in energy expenditure and glucose metabolism.

FIG. 3.

Pdx1-CreDam;R26Rwt/lacZ mice display a complex pattern of Cre-mediated recombination that partially overlaps with orexin-positive and leptin-responsive neuronal populations. Adult Pdx1-CreDam;R26Rwt/lacZ mice were treated with leptin (5 mg/kg, intraperitoneally, 2 h), perfusion-fixed and brains isolated for immunohistochemical detection of pSTAT3, orexin, and β-gal positive. Localization of β-gal signal in brain sections of adult Pdx1-CreDam;R26Rwt/lacZ mice is available in supplementary Fig. 10. A–C: pSTAT3 (green) and β-gal (red) immunoreactivity do not co-localize efficiently in the arcuate nucleus (ARC). D–I: Co-localization of pSTAT3 (green) and β-gal (red) immunoreactivity in a subpopulation of neurons in the lateral hypothalamus (LHA). Despite extensive β-gal labeling within the preoptic area, there was essentially no co-localization with leptin-responsive neurons (data not shown). J–O: Co-localization of orexin (green) and β-gal (red) immunoreactivity within neurons in the LHA. Arrows indicate co-labeled neurons. All scale bars are either 50 μm or 200 μm (as indicated). The unlabeled scale bar in the ARC panel in A is 50 μm. (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

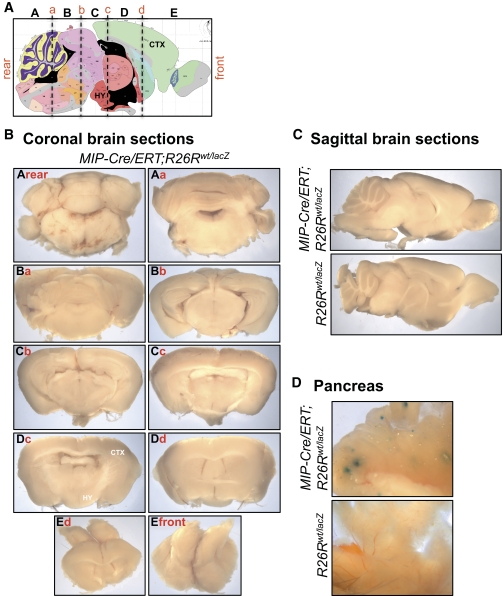

A new transgenic line, MIP-Cre/ERT, which employs an 8.5-kb fragment of the mouse Ins1 promoter has been recently developed to express the tamoxifen-inducible Cre/ERT in β-cells (Tamarina et al., unpublished data) (Table 1). Following three doses of 2-mg tamoxifen, strong β-gal activity was detected in the pancreatic islets of adult MIP-Cre/ERT;R26Rwt/lacZ mice but not in their R26Rwt/lacZ littermates (Fig. 4). By contrast, no β-gal activity was detected in any region of the brain from MIP-Cre/ERT;R26Rwt/lacZ mice (Fig. 4). Furthermore, when the tamoxifen dose was increased to three doses of 8-mg, β-gal activity was not detected within the brain (data not shown). Cre expression efficiency in the β-cells, as determined by immunohistochemistry, was similar in MIP-Cre/ERT (89.0 ± 8.0%), RIP-Cre (85.4 ± 5.5%), RIP-Cre/ERT (88.9 ± 5.8%), and Pdx1-Cre/ERT (92.1 ± 6.6%) mice (supplemental Fig. 11).

FIG. 4.

Cre activity is undetectable in MIP-Cre/ERT brain. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with three 2-mg doses of tamoxifen over a 5-day period. Brains from adult MIP-Cre/ERT; R26Rwt/lacZ (n = 5) and their R26Rwt/lacZ littermates (n = 5) (24) were sliced into five coronal sections and subjected to whole-mount X-gal staining. A: Sagittal view of mouse brain. The schematic of the mouse brain is from the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas (http://www.brain-map.org/) (29). Brain slices examined are shown in capital letters (A, B, C, etc.). Vertical dashed lines mark coronal sectioning plane designated as face in lowercase letters (a, b, c, etc.). B: Images of individual brain slices from each coronal sectioning plane. C: Sagittal brain sections from MIP-Cre/ERT; R26Rwt/lacZ (top panel) and R26Rwt/lacZ littermates (bottom panel). D: Whole-mount X-gal staining of pancreas from MIP-Cre/ERT; R26Rwt/lacZ (top panel) and R26Rwt/lacZ littermates (bottom panel). Brains from MIP-Cre/ERT; R26Rwt/lacZ mice and controls in B and C were negative for X-gal staining, while MIP-Cre/ERT; R26Rwt/lacZ pancreas showed robust X-gal labeling in the islets in D. CTX, cortex; HY, hypothalamus. (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

DISCUSSION

The studies examining the in vivo role of genes associated with biological processes in the pancreas and β-cells have relied largely upon fragments of the rat Ins2 gene promoter or the Pdx1 gene promoter (3,8–13,16). Although insulin secretion from β-cells plays an important role in glucose control, many other tissues including the brain are intimately involved in the regulation of glucose metabolism. Previous studies have demonstrated that the 668 bp rat Ins2 promoter fragment drives Cre-recombinase expression within the central nervous system of the mouse transgenic line, RIP-CreMgn [Tg(Ins2-cre)25Mgn] (9,24,25). In this study, we examined whether Cre-mediated recombination occurred in the brain of six mouse transgenic lines that have been extensively used to express Cre specifically within the pancreas or islet β-cells (Table 1). Analysis of Cre-mediated recombination using the R26R reporter strain demonstrated that all six transgenic lines expressed Cre recombinase to varying extents within the brain, raising the possibility that alterations of gene expression in the brain may complicate the analysis and that the observed phenotype may not be solely due to changes in the β-cell. This possibility was highlighted by a recent study that used the RIP-CreMgn line to selectively delete the Stat3 gene in the β-cells (24). STAT3-deficient mice displayed increased food intake, obesity, and leptin resistance; physiological effects that the authors attributed to STAT3 deficiency in the brain leading to impaired leptin signaling.

There are no previous studies reporting Cre-mediated recombination in the brain with Pdx1-Cre lines. Our findings indicate that the Pdx1-CreDam line causes recombination in a subset of hypothalamic neurons involved in energy and nutrient homeostasis. The similarity of β-gal–expression patterns in the hypothalamus with the other two Pdx1-Cre transgenic lines suggest that Cre-mediated recombination in these lines may also affect similar neuronal subpopulations. The lack of β-gal activity in the brains of Pdx1wt/lacZ mice indicates that the Cre expression in the brain of the Pdx1-CreDam, Pdx1-CreTuv, and Pdx1AI-III-Cre/ERT mice is not a reflection of endogenous Pdx1 gene expression. A likely explanation for this spurious expression is the removal of these Pdx1 gene promoter fragments from their endogenous gene context. Furthermore, the similar recombination pattern generated with Pdx1-Cre lines makes it unlikely that this brain expression is a result of neighboring sequences at the sites of integration, which are almost certainly different for each line. While a lacZ knock-in reporter to analyze endogenous Ins2 expression is currently not available, a recent study demonstrated expression of the Ins2 gene but not the Ins1 gene in the mouse hypothalamus (26). Thus, in contrast to the infidelity of Cre transgene expression found with the Pdx1 promoter, Cre expression observed using the Ins2 promoter may reflect, in part, endogenous promoter activity. It is not known whether the ectopic expression of the insulin or Pdx-1 transgenes occurs during the embryonic period, adult periods, or in both periods.

Several caveats should be considered in interpreting our results. First, we did not examine all currently available insulin, PDX-1, or other gene promoters used to direct Cre expression to the pancreas or β-cell. Thus, it is essential that investigators examine brain expression in any Cre line thought to be pancreas- or β-cell–specific. Second, our results should not be interpreted to indicate specific expression (or lack of expression) in any brain region or nuclei as we did not perform detailed mapping of brain regions following lacZ staining. We did note regions with strong X-gal staining, but this should not be taken as evidence that other areas do not express Cre, and it is possible that a more isolated or diffuse expression in other brain regions may also lead to Cre activity. More detailed work is needed to identify which brain regions are positive or negative for Cre activity. Third, whether Cre expression leads to excision of a floxed DNA fragment is an incompletely understood process that depends on both Cre expression and the floxed allele. We mostly used a single reporter line, and we do not know if the results would differ with other lines that express other reporters such as alkaline phosphatase. In fact, we predict that some reporter lines will not show the same Cre activity we observed given that a range of sensitivity of floxed alleles to Cre-mediated recombination is likely (with the R26Rwt/lacZ line being more Cre-sensitive) (27). This possibility further complicates interpretation of studies using Cre to inactivate a gene of interest. Thus, we urge caution in extrapolating that the lack of Cre-mediated recombination with a certain reporter gene predicts a lack of Cre-mediated recombination of a gene of interest in the brain. Based on the current study, it is clear that the R26Rwt/lacZ floxed allele is susceptible to Cre-mediated recombination in several brain regions, including orexin-positive and leptin-responsive neuronal populations. Finally, the experimental intent for using Cre transgene must be considered. If lineage tracing is the goal, is it preferable to use a “sensitive” or “insensitive” reporter? If gene inactivation is the goal of Cre-mediated recombination, then whether other tissues or cells endogenously express the gene of interest becomes a critical factor. If the gene of interest is expressed in places other than the pancreas or β-cell (especially in the brain where a large number of genes are known to be expressed in both tissues), then the current finding of Cre-mediated recombination in brain regions involved in glucose homeostasis, appetite, weight, and energy expenditure make attributions of the phenotype to the β-cell more difficult.

The above analysis clearly illustrates that new transgenic lines are needed to ensure fidelity of conditional Cre expression in islet β-cells. In transgenic Tg(Ins1-EGFP)1Hara mice (28), an 8.5-kb fragment of the mouse Ins1 gene promoter was successfully used to express enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) specifically within islet β-cells in the absence of eGFP expression in other tissues. This same Ins1 promoter fragment was used in the MIP-Cre/ERT transgenic line to direct Cre/ERT gene expression in β-cells (Tamarina et al., unpublished data). The improved fidelity of Cre expression observed in the MIP-Cre/ERT line is likely due, in part, to the additional regulatory elements within the larger promoter fragment employed and because the mouse Ins1 gene is not expressed in the hypothalamus (26). Thus, the MIP-Cre/ERT mice appear to represent a transgenic line to express Cre efficiently and specifically in islet β-cells.

In conclusion, this study reveals that the current transgenic lines utilizing Ins2 and Pdx1 promoter fragments target Cre expression not only to the islet β-cells, but also to the brain. While not invalidating the use of these lines, our data indicate that studies conducted using these Cre transgenic mice should be interpreted carefully to assess whether manipulation of the target gene within the brain could contribute to the observed phenotype. The lack of Cre-mediated recombination in the brain of MIP-Cre/ERT;R26Rwt/lacZ mice suggests that the newly developed MIP-Cre/ERT line is currently the only available β-cell–specific Cre line. As with all newly developed Cre transgenic lines, caution must also be exhibited when using this line until its potential as a β-cell–specific Cre line has been validated through further experimental analysis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the following grants: National Institutes of Health (NIH) DK63363, Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JRDF) 1-2008-473, American Diabetes Association (ADA) 7-09-BS-41, University of Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center Pilot & Feasibility (DRTC P&F) P60 DK020572, and the D.R.E.A.M. Foundation (to P.J.D.); ADA Junior Faculty Award and University of Chicago DRTC P&F grant P60 DK20595 (to B.W.); NIH DK057768 and American Heart Association Established Investigator Award (to M.G.M.); NIH DK074966 (to M.W.R.); NIH DK065131, DK071052, and JRDF 1-2007-548 (to M.G.); NIH HD36720 and JDRF 1-2006-219 and Vanderbilt DRTC P&F grant P60 DK020593 (to P.A.L.); NIH T32DK07563 (to J.P.); NIH DK073716 and JDRF 1-2008-147 (to E.B.); NIH DK69603, DK66636, DK072473, a Merit Review Award from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Research Service, and JDRF 1-2008-512 (to A.C.P.). Core facilities used in this study were supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases DRTCs from the University of Chicago (P60 DK020595), University of Michigan (P60 DK020572), Vanderbilt University (P60 DK020593), and the Vanderbilt Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center (DK59637). The schematics of the mouse brain shown in the figures are from the Allen Brain Atlas Resources (http://www.brain-map.org/) (29).

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

B.W., M.B., A.C.P., and P.J.D. conceived the study. B.W., M.B., P.A.L., M.G., M.G.M., A.C.P., and P.J.D. designed the experimental approach. B.W., M.B., W.Y., D.M.O., J.L.P., R.B.R., L.M.D., A.S., and L.E. researched data. E.B.-M., M.G.M., and M.G. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. N.A.T., L.H.P., and M.W.R. provided novel reagents. B.W., M.B., M.G., A.C.P. and P.J.D. wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

See accompanying commentary, p. 2991.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fawell SE, Lees JA, White R, Parker MG: Characterization and colocalization of steroid binding and dimerization activities in the mouse estrogen receptor. Cell 1990;60:953–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayashi S, McMahon AP: Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre: a tool for temporally regulated gene activation/inactivation in the mouse. Dev Biol 2002;244:305–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gannon M, Gamer LW, Wright CV: Regulatory regions driving developmental and tissue-specific expression of the essential pancreatic gene pdx1. Dev Biol 2001;238:185–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiebe PO, Kormish JD, Roper VT, Fujitani Y, Alston NI, Zaret KS, Wright CV, Stein RW, Gannon M: Ptf1a binds to and activates area III, a highly conserved region of the Pdx1 promoter that mediates early pancreas-wide Pdx1 expression. Mol Cell Biol 2007;27:4093–4104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whelan J, Poon D, Weil PA, Stein R: Pancreatic beta-cell-type-specific expression of the rat insulin II gene is controlled by positive and negative cellular transcriptional elements. Mol Cell Biol 1989;9:3253–3259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edlund T, Walker MD, Barr PJ, Rutter WJ: Cell-specific expression of the rat insulin gene: evidence for role of two distinct 5′ flanking elements. Science 1985;230:912–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.German MS, Moss LG, Wang J, Rutter WJ: The insulin and islet amyloid polypeptide genes contain similar cell-specific promoter elements that bind identical beta-cell nuclear complexes. Mol Cell Biol 1992;12:1777–1788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahlgren U, Jonsson J, Jonsson L, Simu K, Edlund H: β-Cell-specific inactivation of the mouse Ipf1/Pdx1 gene results in loss of the β-cell phenotype and maturity onset diabetes. Genes Dev 1998;12:1763–1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gannon M, Shiota C, Postic C, Wright CV, Magnuson M: Analysis of the Cre-mediated recombination driven by rat insulin promoter in embryonic and adult mouse pancreas. Genesis 2000;26:139–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrera PL: Adult insulin- and glucagon-producing cells differentiate from two independent cell lineages. Development 2000;127:2317–2322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Postic C, Shiota M, Niswender KD, Jetton TL, Chen Y, Moates JM, Shelton KD, Lindner J, Cherrington AD, Magnuson MA: Dual roles for glucokinase in glucose homeostasis as determined by liver and pancreatic beta cell-specific gene knock-outs using Cre recombinase. J Biol Chem 1999;274:305–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dor Y, Brown J, Martinez OI, Melton DA: Adult pancreatic beta-cells are formed by self-duplication rather than stem-cell differentiation. Nature 2004;429:41–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu G, Dubauskaite J, Melton DA: Direct evidence for the pancreatic lineage: NGN3+ cells are islet progenitors and are distinct from duct progenitors. Development 2002;129:2447–2457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hingorani SR, Petricoin EF, Maitra A, Rajapakse V, King C, Jacobetz MA, Ross S, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Hitt BA, Kawaguchi Y, Johann D, Liotta LA, Crawford HC, Putt ME, Jacks T, Wright CV, Hruban RH, Lowy AM, Tuveson DA: Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell 2003;4:437–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H, Fujitani Y, Wright CV, Gannon M: Efficient recombination in pancreatic islets by a tamoxifen-inducible Cre-recombinase. Genesis 2005;42:210–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Offield MF, Jetton TL, Labosky PA, Ray M, Stein RW, Magnuson MA, Hogan BL, Wright CV: PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development 1996;122:983–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soriano P: Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet 1999;21:70–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, William CM, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, Costantini F: Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol 2001;1:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zambrowicz BP, Imamoto A, Fiering S, Herzenberg LA, Kerr WG, Soriano P: Disruption of overlapping transcripts in the ROSA beta geo 26 gene trap strain leads to widespread expression of beta-galactosidase in mouse embryos and hematopoietic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997;94:3789–3794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagy A, Gertsenstein M, Vintersten K, Behringer R: Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Münzberg H, Jobst EE, Bates SH, Jones J, Villanueva E, Leshan R, Björnholm M, Elmquist J, Sleeman M, Cowley MA, Myers MG, Jr: Appropriate inhibition of orexigenic hypothalamic arcuate nucleus neurons independently of leptin receptor/STAT3 signaling. J Neurosci 2007;27:69–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brissova M, Fowler M, Wiebe P, Shostak A, Shiota M, Radhika A, Lin PC, Gannon M, Powers AC: Intraislet endothelial cells contribute to revascularization of transplanted pancreatic islets. Diabetes 2004;53:1318–1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H, Ackermann AM, Gusarova GA, Lowe D, Feng X, Kopsombut UG, Costa RH, Gannon M: The FoxM1 transcription factor is required to maintain pancreatic beta-cell mass. Mol Endocrinol 2006;20:1853–1866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui Y, Huang L, Elefteriou F, Yang G, Shelton JM, Giles JE, Oz OK, Pourbahrami T, Lu CY, Richardson JA, Karsenty G, Li C: Essential role of STAT3 in body weight and glucose homeostasis. Mol Cell Biol 2004;24:258–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Tobe K, Yano W, Suzuki R, Ueki K, Takamoto I, Satoh H, Maki T, Kubota T, Moroi M, Okada-Iwabu M, Ezaki O, Nagai R, Ueta Y, Kadowaki T, Noda T: Insulin receptor substrate 2 plays a crucial role in beta cells and the hypothalamus. J Clin Invest 2004;114:917– 927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madadi G, Dalvi PS, Belsham DD: Regulation of brain insulin mRNA by glucose and glucagon-like peptide 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008;376:694–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Badea TC, Hua ZL, Smallwood PM, Williams J, Rotolo T, Ye X, Nathans J: New mouse lines for the analysis of neuronal morphology using CreER(T)/loxP-directed sparse labeling. PLoS One 2009;4:e7859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hara M, Wang X, Kawamura T, Bindokas VP, Dizon RF, Alcoser SY, Magnuson MA, Bell GI: Transgenic mice with green fluorescent protein-labeled pancreatic beta-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2003;284:E177–E183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen Brain Atlas Resources [Internet], 2009. Seattle, WA, Allen Institute for Brain Science; Available from http://www.brain-map.org/ Accessed 17 April 2010 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.