Abstract

Cells infected with wild type HSV-1 showed significant lamin A/C and lamin B rearrangement, while UL34-null virus-infected cells exhibited few changes in lamin localization, indicating that UL34 is necessary for lamin disruption. During HSV infection, US3 limited the development of disruptions in the lamina, since cells infected with a US3-null virus developed large perforations in the lamin layer. US3 regulation of lamin disruption does not correlate with the induction of apoptosis. Expression of either UL34 or US3 proteins alone disrupted lamin A/C and lamin B localization. Expression of UL34 and US3 together had little effect on lamin A/C localization, suggesting a regulatory interaction between the two proteins. The data presented in this paper argue for crucial roles for both UL34 and US3 in regulating the state of the nuclear lamina during viral infection.

Keywords: HSV-1, UL34, US3, Lamin disruption, Egress

Introduction

During primary envelopment herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) nucleocapsids translocate from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. The capsid must face numerous obstacles before it can reach the inner nuclear membrane (INM). Lining the inside of the INM is the nuclear lamina, which is composed of a meshwork of proteins with spaces too small for the capsid to move through without some disruption of the lamina. The lamina is mainly made up of lamin A/C and lamin B proteins, with smaller amounts of other proteins also present (Gruenbaum et al., 2000). Type A and C lamins are derived from the same gene that is differentially spliced and are expressed primarily in differentiated cells (Goldman et al., 2002). All vertebrate cells express some form of type B lamins (Holaska et al., 2002). The lamins share significant structural similarities to intermediate filaments, and have a characteristic α-helical domain flanked by nonhelical domains, which mediate binding of the lamin proteins to each other to form filaments (McKeon et al., 1986). Lamins associate with themselves, other types of lamins, lamin associated proteins (LAPs) and even chromatin (Gruenbaum et al., 2000; Holaska et al., 2002; Holmer and Worman, 2001). In addition to multiple interactions with cellular proteins, lamins also interact with viral proteins, like the IR6 protein of equine herpesvirus, which is thought to play a role in primary envelopment (Osterrieder et al., 1998). Herpesvirus infections also affect lamin localization and morphology. HSV-1 infection distorts localization of GFP-tagged lamin A, lamin B and lamin B receptor (LBR) constructs, and also disrupts interactions between LBR and the lamina (Scott and O'Hare, 2001). Murine cytomegalovirus M50/p35, the homolog to the UL34 gene in HSV-1, recruits cellular proteins kinase C to the nuclear membrane and induces lamin phosphorylation (Muranyi et al., 2002). Disruption of the lamina is thought to allow the viral capsid access to the INM, however, there is currently no conclusive experimental evidence to support this hypothesis.

Modifications of the nuclear lamina occur during the normal cell processes of apoptosis and mitosis (Goldman et al., 2002). During apoptosis, cleavage of lamins by caspase 6, as well as cleavage of LAPs by caspase 3, is necessary for progression to cell death (Gruenbaum et al., 2000; Rao et al., 1996). It is thought that lamin degradation plays a crucial role in shutting down nuclear processes during apoptosis. During mitosis, the lamins are phosphorylated and reversibly depolymerized by various cellular kinases (Gerace and Blobel, 1980; Peter et al., 1990; Thompson et al., 1997). After cell division, phosphatases dephosphorylate the lamins, allowing them to reassemble at the nuclear envelope. It is possible that herpesviruses utilize lamin cleavage, phosphorylation, or both processes to create breaks in the lamina network during viral egress.

Many HSV proteins have been identified as having roles in primary envelopment, including: UL34, UL31, US3, UL11, UL36 and UL37 (Baines and Roizman, 1992; Brown et al., 1994; Desai, 2000; Desai et al., 2001; Granzow et al., 2000; Hutchinson and Johnson, 1995; Mossman et al., 2000; Reynolds et al., 2001, 2002; Roller et al., 2000). Cellular proteins have not been shown to be required for this process, although it is likely that cellular proteins play a role in targeting viral proteins to specific locations within the cell. The HSV-1 UL34 gene product is critical for primary envelopment since a recombinant virus that fails to express this protein showed a three- to five-log order of magnitude decrease in replication, and TEM analysis of infected cells showed no evidence of enveloped nucleocapsids (Roller et al., 2000). This critical function is conserved in pseudorabies virus (Klupp and Mettenleiter, 2000) equine herpesvirus type 1 (Neubauer et al., 2002), and Epstein–Barr virus (Farina et al., 2005). The HSV-1 UL34 gene is a probable type II membrane protein that is phosphorylated by the viral kinase US3 (Purves et al., 1991, 1992). In addition to a role in viral egress (Klupp et al., 2001; Reynolds et al., 2002; Wagenaar et al., 1995), the US3 gene product protects cells from apoptosis (Asano et al., 1999; Galvan and Roizman, 1998; Leopardi et al., 1997). Recently, UL34 was shown to also be phosphorylated by an unidentified kinase in specific cell types, although to a lesser extent than phosphorylation by US3 (Ryckman and Roller, 2004). The phosphorylation state of UL34 has different effects on viral growth depending on cell type (Ryckman and Roller, 2004), and it is unknown whether these effects are directly related to problems with primary envelopment. The UL34 coding sequence is present in β and γ herpesvirus family members and is well conserved among alphaherpesviruses (Davison and Scott, 1986; Dolan et al., 1998; Telford et al., 1992), which may indicate that the role of this protein in primary envelopment is also conserved.

HSV-1 UL34 forms part of an envelopment complex that also includes the UL31 and US3 proteins. All three proteins colocalize at the nuclear membrane, and each of these is necessary for normal localization of the others in infected cells (Reynolds et al., 2004; Roller et al., 2000). UL34 also interacts with and forms a complex with the UL31 protein in vitro (Reynolds et al., 2001).

Alphaherpesvirus US3 homologs have been implicated in diverse processes in the infected cell, including inhibition of apoptosis (Leopardi et al., 1997; Asano et al., 1999; Hata et al., 1999; Jerome et al., 1999; Takashima et al., 1999; Asano et al., 2000; Munger and Roizman, 2001; Murata et al., 2002; Benetti et al., 2003; Cartier et al., 2003; Calton et al., 2004; Ogg et al., 2004; Geenen et al., 2005; Matsuzaki et al., 2005; Poon and Roizman, 2005), de-envelopment of capsids at the outer nuclear membrane (Klupp et al., 2001; Reynolds et al., 2002; Granzow et al., 2004; Ryckman and Roller, 2004; Schumacher et al., 2005), and rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton (Murata et al., 2000; Cartier et al., 2003; Favoreel et al., 2005; Schumacher et al., 2005). Although UL34 was the first identified substrate of the US3 protein kinase activity, it is now clear that there may be many others. It has recently been shown that the viral UL31, US9 and ICP22 proteins can be directly phosphorylated by US3 (Kato et al., 2005).

Evidence in the literature supports a role for components of the envelopment complex in disrupting the nuclear lamina. UL34 and UL31 proteins have recently been shown to be required for changes in nuclear shape and for changes in the distribution of nuclear lamin A/C protein in infected and transfected cells, and UL34 has a lamin A/C disrupting activity in transfected cells (Reynolds et al., 2004; Simpson-Holley et al., 2004). UL34 protein has been shown to interact directly with Lamin A/C in vitro (Reynolds et al., 2004). When UL34 is overexpressed during transient transfections, the morphology of the nuclear membrane is altered so that the inner and outer membranes are separated (Ye et al., 2000). This distortion of the nuclear membrane resembles the phenotype seen in HSV-1 infected cells. In addition, the location of UL34 in infected cells at the nuclear membrane places it in an excellent position to interact with and modulate the actions of lamin proteins and LAPs. There is no direct evidence to suggest that US3 plays a role is disassembling the nuclear lamina, however, this protein also localizes to the INM during infections and is closely linked to UL34 localization and function (Leopardi et al., 1997; Reynolds et al., 2002). Here we examine the individual activities and functional relationship of UL34 and US3 in nuclear lamina disruption.

Results

UL34 and US3 proteins are necessary for changes in nuclear contour shape during HSV-1 infection

Previous data have shown that UL34 and UL31 are necessary for HSV infection-dependent changes in nuclear shape and lamin A/C distribution (Reynolds et al., 2004; Simpson-Holley et al., 2004). In order to examine the distribution of lamin B, the functional interactions between UL34 and US3 in lamin reorganization, and the role of the US3 protein in affecting lamin localization, we determined the localization of nuclear lamins in cells infected with viruses that fail to express either UL34 or US3.

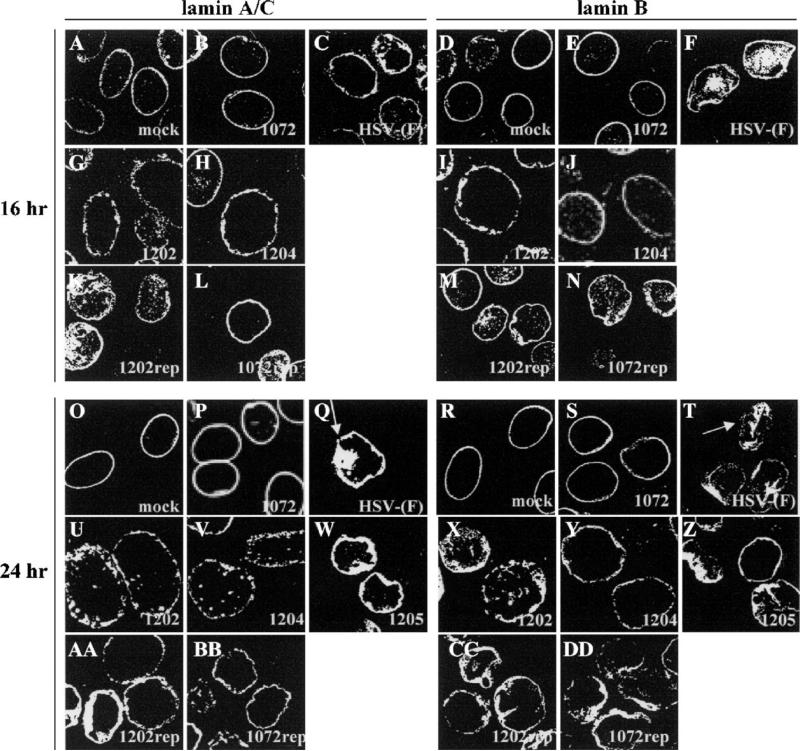

To investigate the roles of UL34 and US3 in disrupting lamins, Vero cells were infected with wild type or mutant viruses at an MOI of 5 for 16 and 24 h, processed for confocal microscopy, and immunostained for lamin A/C or lamin B (Fig. 1). In mock-infected cells, lamin A/C (panels A and O) and lamin B (panels D and R) proteins localized in a tight ring around the nucleus of the cell, showing a smooth, regular distribution of protein on the nuclear envelope. The shape of the nucleus revealed by lamin staining is ovoid and smooth. HSV-1 (F) infection of Vero cells resulted in a disruption of normal lamin localization and the shape of the nucleus. By 16 h after infection, when new infectious virus is being produced at high levels, Lamin A/C (panel C) and lamin B (panel F) proteins did not localize smoothly; some lamin protein localized with a globular distribution in the nucleus, and nuclear envelope staining became irregular and patchy, revealing a wrinkled nuclear shape not seen in mock-infected cells. After 24 h of infection with wild-type virus (panels Q and T), changes in lamin distribution and nuclear shape were more pronounced. Arrows point to areas where staining is absent. Consistent with previous findings (Reynolds et al., 2004; Simpson-Holley et al., 2004) cells infected with the UL34-null virus vRR1072 did not show changes in nuclear shape or mislocalization of lamin A/C protein to cytoplasmic or nuclear structures (panels B and P); these cells looked similar to mock-infected cells even at 24 h after infection. We observed similar UL34-dependent changes in lamin B staining. Cells infected with HSV-1(F) showed disruption of lamin localization and change in nuclear shape (panels F and T), whereas cells infected with the UL34-null virusvRR1072 did not (panels E and S). Cells infected with a vRR1072 repair virus showed lamin A/C and lamin B phenotypes identical to wild type virus-infected cells (panels L, N, BB, and DD).

Fig. 1.

UL34- and US3-dependent disruption of the nuclear lamina of Vero cells. Shown are digital confocal images of optical sections taken near the middle of the cell nucleus showing the disruption of lamin A/C and lamin B localization in infected Vero cells. For all panels, Vero cells were mock infected or infected with the UL34-null virus vRR1072, HSV-1(F), the US3-null virus vRR1202, the US3 kinase-dead virus vRR1204, the UL34 phosphorylation mutant virus vRR1205, the UL34 repair virus vRR1072Rep, or the US3 repair virus vRR1202Rep for 16 or 24 h at an MOI of 5. The infecting virus is indicated in the lower right corner of each panel. The time of infection is indicated to the left of the figure. The primary antibody used for staining is indicated at the top of the figure. Cells stained for lamin A/C were fixed with formaldehyde; those stained for lamin B were fixed with cold methanol. Cover slips were also co-stained with a viral protein to ascertain infection.

Cells infected with the US3-null virus vRR1202 showed a phenotype different from either mock-infected or wild type virus-infected cells. Both lamin A/C (panels G and U) and lamin B (panels I and X) localized in punctate patches on the nuclear envelope, with a small amount of the proteins localizing inside the nucleus. The change in lamin distribution was evident at 16 h (panels G and I) and more pronounced at 24 h (panels U and X). Despite aberrant lamin localization, there was no change in nuclear shape as was seen in wild type virus-infected cells. Lamin staining in cells infected with the vRR1202 repair virus showed lamin phenotypes that were indistinguishable from wild type virus-infected cells (panels K, M, AA and CC). Nuclei in US3-null virus-infected cells (panels G, I, U, and X) were larger than nuclei seen in other infected or mock-infected cells. When the diameters at the narrowest part of the nuclei from vRR1202-infected cells were measured, they were on average 1.5–2 times larger than nuclei of mock-infected cells. Nuclei from HSV-1(F) infected cells were not included in this analysis because their uneven nuclear shape prevented accurate measurements.

The role of HSV-1 US3 in preventing apoptosis and in supporting single-step growth on some cell types depends on its kinase activity (Ogg et al., 2004; Ryckman and Roller, 2004). To determine the effect of US3 kinase activity on lamin distribution, Vero cells were infected with a virus encoding a non-catalytic US3 gene (vRR1204) and the distribution of lamin A/C and lamin B were observed by confocal microscopy (Fig. 1). The distribution of lamin A/C (panels H and V) and lamin B (panels J and Y) in cells infected with vRR1204 looked identical to lamin distribution in cells infected with the US3-null virus vRR1202 at both 16 and 24 h, and measurements of nuclear diameters showed the same degree of enlargement for both viruses indicating that kinase activity of US3 is necessary for changes in nuclear shape and size.

To determine whether the phosphorylation state of UL34 has an effect on lamin disruption, cells were infected with a virus in which the phosphorylated residues were changed to alanines (vRR1205) and lamin A/C and lamin B distribution was examined by confocal microscopy (Fig. 1). In cells infected with vRR1205 for 24 h, both lamin A/C (panel W) and lamin B (panel Z) staining revealed significant changes in nuclear shape and patchy, irregular NM staining indistinguishable from phenotypes seen in wild type HSV-infected cells.

To ensure that disruption of lamin localization was not cell type specific, confocal microscopy was also used to analyze the effects of virus infection on the lamina of HEp-2 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1). Lamin A/C and lamin B localization looked the same in human HEp-2 cells as it did in simian Vero cells infected with the virus mutants discussed above.

US3-null and kinase-dead US3 viruses cause perforations in the lamina

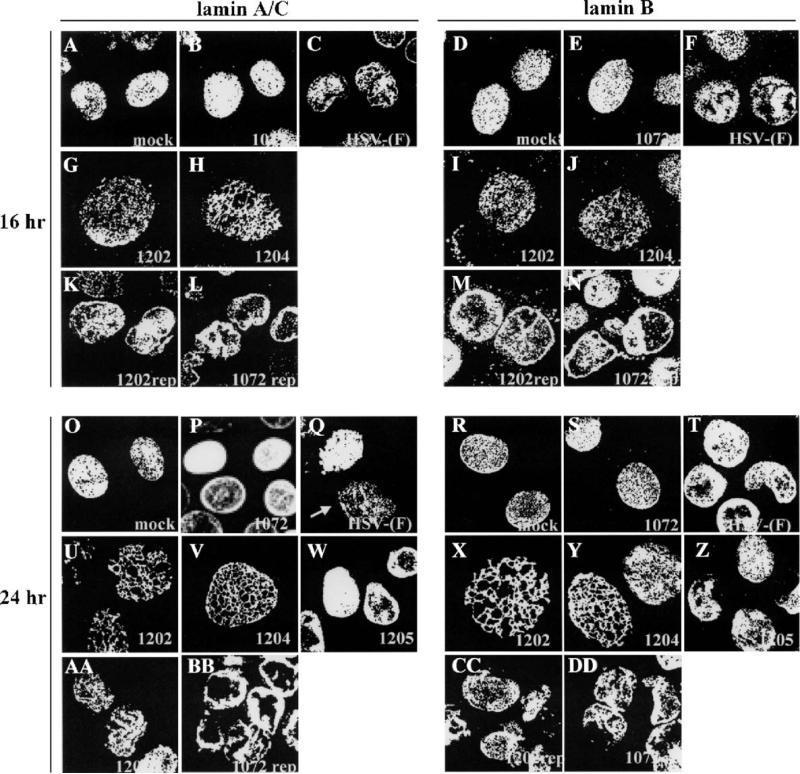

Cross sections taken towards the top of Vero cells (Fig. 2) during confocal microscopy revealed different phenotypes than sections taken in the middle of the cell or Z stacks of the entire cell. In mock-infected Vero cells, a top section showed that both lamin A/C (panels A and O) and lamin B (panels D and R) were distributed on the surface of the nuclear envelope in a diffuse, even pattern. Cells infected with vRR1072 (panels B, E, P, and S) appeared identical to mock-infected cells at both 16 and 24 h after infection. However, cells infected with HSV-1(F) developed small perforations throughout the lamina, exhibited by an absence of staining for both lamin A/C (panels C and Q ) and lamin B (panels F and T). The arrow in Fig. 2, panel Q shows perforations in the lamina of HSV-1(F) infected cells. Repair viruses for vRR1072 (panels L, N, BB, and DD) and vRR1202 (panels K, M, AA, and CC) showed results identical to wild type HSV-infected cells.

Fig. 2.

UL34- and US3-dependent formation of perforations in the nuclear lamina of Vero cells. Shown are digital confocal images of optical sections taken near the top of the cell nucleus showing perforations in lamin A/C and lamin B localization in infected Vero cells. For all panels, Vero cells were mock infected or infected with the UL34-null virus vRR1072, HSV-1(F), the US3-null virus vRR1202, the US3 kinase-dead virus vRR1204, the UL34 phosphorylation mutant virus vRR1205, the UL34 repair virus vRR1072Rep, or the US3 repair virus vRR1202Rep for 16 or 24 h at an MOI of 5. The infecting virus is indicated in the lower right corner of each panel. The time of infection is indicated to the left of the figure. The primary antibody used for staining is indicated at the top of the figure. Cells stained for lamin A/C were fixed with formaldehyde; those stained for lamin B were fixed with cold methanol. Cover slips were also co-stained with a viral protein to ascertain infection.

Cells infected with vRR1202 (panels G, I, U, and X) and vRR1204 (panels H, J, V, and Y) showed numerous large perforations in the lamin A/C (panels G, H, U, and V)) and lamin B (panels I, J, X, and Y) layers in every cell. The perforations were evident at 16 h after infection (panels G, H, I, and J) and were more pronounced at 24 h after infection (panels U, V, X, and Y). These perforations were larger and more widespread than those found in wild type virus-infected cells, suggesting that the ability to inhibit formation of these perforations is abrogated in cells infected with vRR1202 or vRR1204.

Examination of HEp-2 cells in identical experiments showed results similar to those seen in Vero cells for all viruses tested (Supplementary Fig. 2).

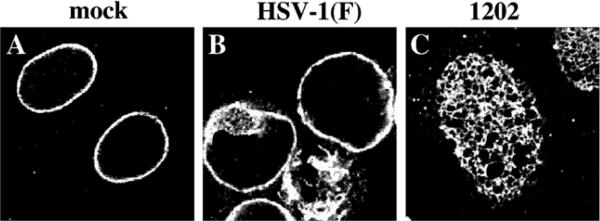

To determine whether the reorganization of lamins seen in virus infection might be the result of masking of the epitopes recognized by the monoclonal antibodies used, uninfected cells and cells infected for 24 h with HSV-1(F) and the US3-null virus vRR1202 were stained using polyclonal directed against lamin A/C (Fig. 3). Disruption of the lamina in wild-type infected cells (panel B and formation of perforations in US3-null virus-infected cells (panel C) were indistinguishable from those detected with monoclonal antibody (compare Fig. 3, panel A with Fig. 1, panel Q and Fig. 3, panel C with Fig. 2, panel U).

Fig. 3.

Alterations of lamin staining in infected cells are not due to monoclonal antibody epitope masking. Shown are digital confocal images showing the localization of lamin A/C in infected Vero cells. Vero cells were mock infected (A), or infected with HSV-1(F) (B) or vRR1202 (C) for 24 h at an MOI of 5. Cells were fixed with formaldehyde and immunostained with chicken polyclonal anti-lamin A/C detected with AlexaFluor 548 goat anti-chicken.

UL34 and US3 localize inside perforations in the lamina during US3-null and kinase-dead US3 virus infections

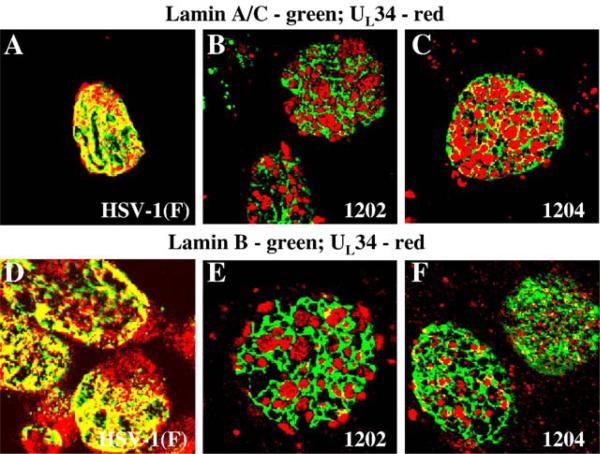

In vRR1204 infected cells, US3, UL34 and UL31 proteins localize together in punctate patches around the nuclear membrane that correspond to large vesicular bodies formed by the nuclear membrane that contain numerous enveloped capsids (Reynolds et al., 2002). To test the hypothesis that the UL34 and US3 proteins in vRR1202 virus infected cells would be associated with the perforations in the lamina, cells were infected for 24 h with HSV-1(F), the US3-null virus vRR1202 or the US3 kinase-dead virus vRR1204 and immunostained for lamin A/C or lamin B proteins and UL34 (Fig. 4). In HSV-1(F)-infected cells, the UL34 protein colocalized extensively with both types of lamins (panels A and D). In vRR1202-infected cells (panels B and E), and in vRR1204-infected cells (panels C and F) UL34 localized almost exclusively inside the perforations formed in the lamin A/C layer (panels B and C)) and lamin B layer (Panels E and F).

Fig. 4.

Association of UL34 with lamin perforations in cells infected with US3 mutant viruses. Shown are digital confocal images showing the localization of UL34 and lamin A/C or lamin B in infected Vero cells. Green: lamins, red: UL34. Vero cells were infected with HSV-1(F) (A and D) vRR1202 (B and E) or vRR1204 (C and F) for 24 h at an MOI of 5. Cells were stained for UL34 (A–F) and for either lamin A/C (A–C) or lamin B (D–F).

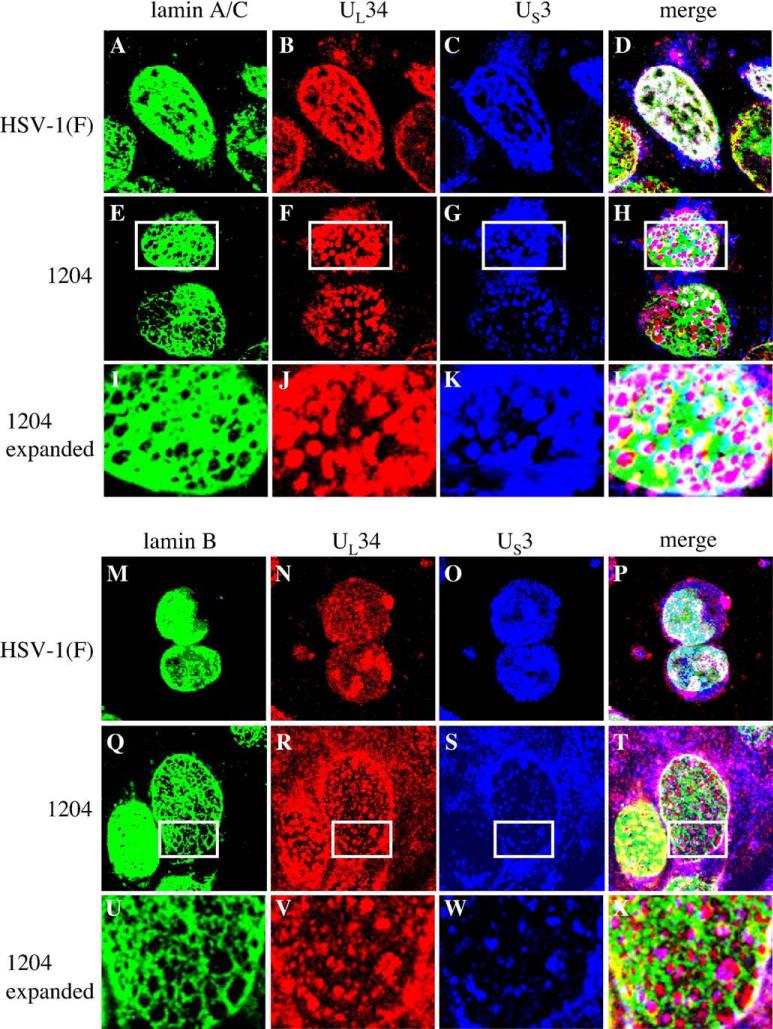

To see whether the US3 protein would also localize inside the larger perforations when the protein is present, cells were infected for 24 h with HSV-1(F) or the US3 kinase-dead virus vRR1204 and immunostained for lamin A/C or lamin B proteins (green), UL34 (red) and US3 (blue) (Fig. 5). All three proteins co-localized extensively in HSV-1(F)-infected cells (panels A–D and panels M–P). In cells infected with vRR1204, however, US3 co-localized with UL34 (panels E–H and panels Q–T) in patches on the nuclear membrane. These patches were located at the perforations in the lamin layer, although lamins and UL34 and US3 co-localized at the edges of the perforations. Boxed regions of panels E–H and Q–T are expanded in panels I–L and U–X, respectively to more clearly show the correspondence between UL34 and US3 staining, and their concentration inside the lamin perforations.

Fig. 5.

Association of US3 with lamin perforations in cells infected with kinase-dead US3 mutant virus. Shown are digital confocal images of UL34, US3 and lamin A/C or lamin B localizations in HSV-1(F) or vRR1204 infected Vero cells. Green: lamins, red: UL34, blue: US3. For all panels, Vero cells were infected with the HSV-1(F) or vRR1204 for 24 h at an MOI of 5. Infecting viruses are indicated to the left of the figure. Panels I–L and U–X each show an enlarged view of the area enclosed in the white box in the panel immediately above.

The different staining patterns seen for UL34 and US3 proteins in Fig. 5 are the result of different fixation conditions needed to detect lamin A/C and lamin B. The expression pattern of UL34 and US3 in formaldehyde fixed cells (Figs. 4 and 5, lamin A/C panels) matches the localization of these proteins in immunogold electron micrographs (Reynolds et al., 2002), with tight nuclear membrane localization of both proteins. The methanol fixation necessary for lamin B staining results in higher background for staining with both UL34 and US3 and fails to distinguish membrane morphology as clearly as formaldehyde fixing.

UL34 protein and other intrinsic membrane proteins are sufficient to cause perforations in the lamina

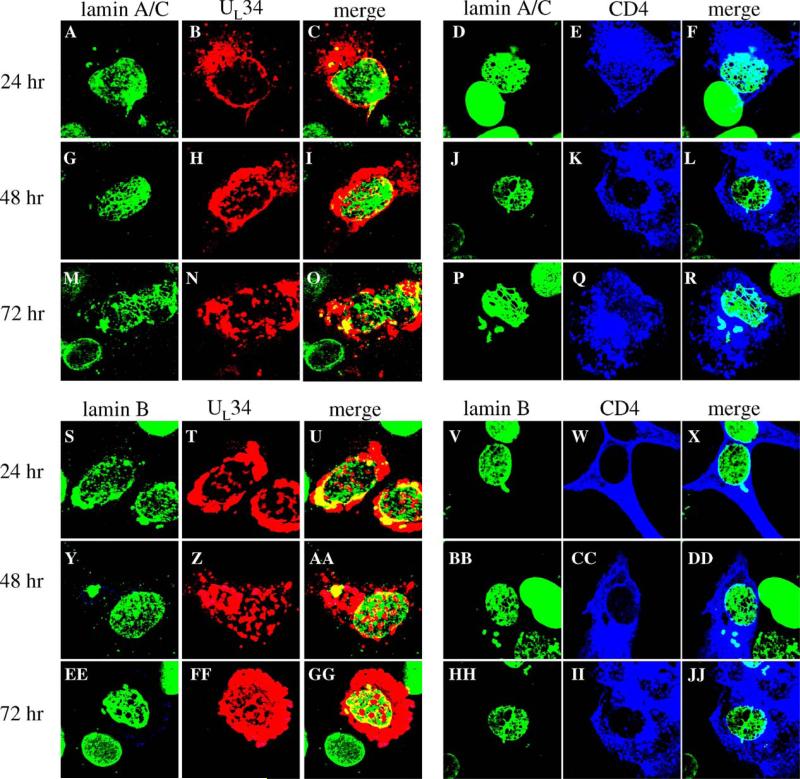

Our data indicate that UL34 is necessary for disrupting the lamina during HSV infection, and both Simpson-Holley et al. (2004) and Reynolds et al. (2004) have shown that UL34 expression in transfected cells leads to disruption of lamin A/C localization. The hypothesis that UL34 alone could affect localization of lamin B as well was tested by transfecting Vero cells with a plasmid encoding the UL34 gene driven by the HCMV-MIEP promoter for 24, 48, or 72 h, processing the cells for confocal microscopy and immunostaining for lamin A/C or lamin B and UL34 (Fig. 6). Expression of UL34 had an increasingly disruptive effect on lamin disruption with time after transfection, such that there was little effect on the lamins A/B or B at 24 h after transfection (panels A–C and S–U cells shown were chosen to illustrate the limited disruption seen at this time point), limited disruption of both lamin types at 48 h after transfection (panels G–I and Y–AA) and extensive disruption by 72 h (panels M–O and EE–GG). The perforations generated in transfected cells differed from those seen in cells infected with vRR1202 in that they were smaller and less evenly distributed than those in infected cells. Despite the formation of these perforations, the lamin proteins mostly remained associated with the nuclear membrane, with only a small subset of both the lamin proteins and UL34 moving to small patches in the cytoplasm.

Fig. 6.

Disruption of Lamin A/C and lamin B localization by expression of transfected UL34 or CD4 genes. Shown are digital confocal images showing the localization of UL34, CD4 and lamin A/C or lamin B in Vero cells expressing either the UL34 or CD4 protein for various times. Green: lamins, red: UL34, blue: CD4. For all panels, Vero cells were transfected with plasmids expressing either UL34 or CD4 for 24, 48, or 72 h. Time after transfection is indicated to the left of each row of panels. The protein being detected is indicated above each column of panels.

In order to determine whether UL34 has a specific ability to create perforations in the lamin layer, the ability of other intrinsic membrane proteins to influence lamin localization was analyzed by confocal microscopy. Surprisingly, we found that all four intrinsic membrane proteins that were tested (CD4, gD, HveA and nectin-2) were all able to disrupt both lamin A/C and lamin B localization with similar kinetics to those seen for UL34. HveA and nectin, cellular proteins involved in HSV-1 entry, were both expressed as RFP fusion proteins under the control of HCMV-MIEP promoters and produced more extensive perforations in the lamina than UL34. CD4 and gD, an HSV-1 glycoprotein, were able to form perforations in the lamina that were similar to what was seen with UL34 expression. Confocal images from cells transfected with a plasmid over-expressing CD4 (Fig. 6) show a small effect on the lamins A/C or B at 24 h after transfection (panels D–F and V–X, cells chosen to show the greatest degree of disruption seen at this time), but increasing disruption of both lamin types 48 h after transfection (panels J–L and BB–DD) and extensive disruption by 72 h (panels P–R and HH–JJ). When over-expressed, intrinsic membrane proteins other than UL34 are also capable of creating perforations in the lamina.

US3 and kinase-dead US3 proteins are sufficient to cause perforations in the lamina and eliminate lamin staining

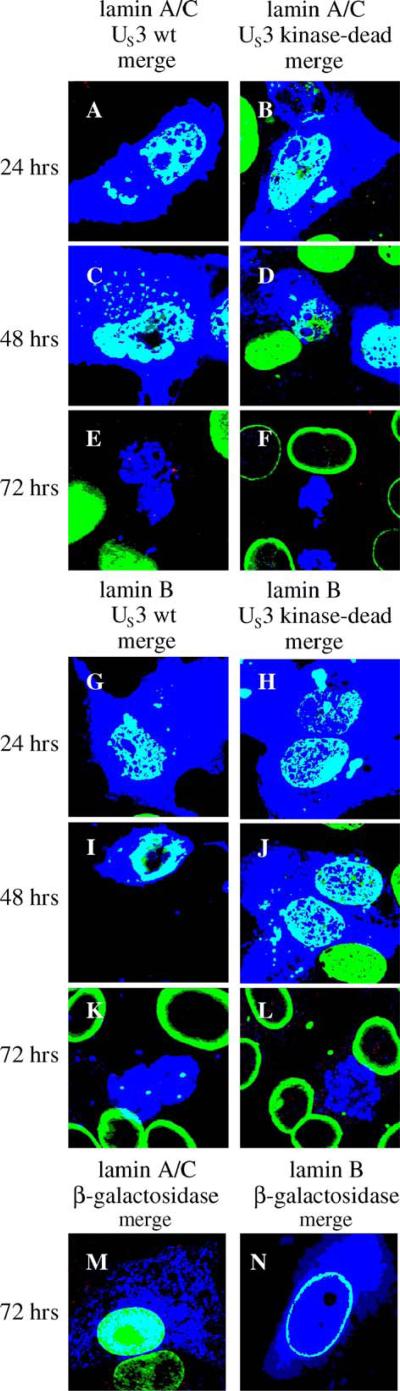

In vRR1202-infected cells, the perforations in the lamina are larger and more ubiquitous than in cells infected with wild type virus, therefore we hypothesized that the function of US3 was to limit lamina disruption during infection. To test the prediction that expression of the US3 protein by transient transfection would not affect lamin localization, Vero cells were transfected with a plasmid containing the US3 gene driven by the HCMV-MIEP and after 24, 48 and 72 h the cells were processed for confocal microscopy and immunostained for lamin A/C or lamin B and US3 (Fig. 7). Unexpectedly, expression of US3 resulted in substantial disruption of lamin A/C and lamin B at 24 h (panel A for lamin A/C and panel G for lamin B, increased disruption at 48 h (panel C for lamin A/C and I for lamin B) and complete loss of lamin staining in some cells at 72 h after transfection (panel E for lamin A/C, and K for lamin B). The remaining transfected cells had extensive perforations in the lamina. It is unlikely that these perforations are due to the onset of apoptosis in these cells, since most transiently transfected cells expressing US3 did not stain with an antibody for cleaved poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (data not shown). US3 appears to have a greater ability than UL34 to produce holes in the lamin A/C and lamin B layers. Although we have no anti-lamin B polyclonal, we have repeated these experiments with two different lamin B monoclonals and found the same result (data not shown), making it unlikely that epitope masking is responsible for loss of lamin B staining in US3-transfected cells.

Fig. 7.

Disruption of lamin A/C and lamin B localization by expression of a transfected US3 gene. Shown are digital merged images showing the localization of wild type US3, mutant US3, beta-galactosidase and lamin A/C or lamin B in Vero cells transfected with plasmids expressing US3 or beta-galactosidase protein. Green: lamins, blue: US3 or beta-galactosidase. For all panels A–L, Vero cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing wild-type or kinase dead US3 for 24, 48 and 72 h. For panels M and N, only the 72 h time point is shown. Time after transfection is indicated to the left of each row of panels. The proteins being detected are indicated above each column of panels.

To test the hypothesis that kinase activity of US3 is also important for the protein to create perforations in the lamina, Vero cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing a kinase-dead US3 gene from an HCMV-MIEP and after 24, 48 and 72 h cells were processed for confocal microscopy (Fig. 7). Like cells expressing a wild type US3 protein, cells expressing the kinase-dead US3 protein showed increasing disruption of lamin A/C (panels B, D, and F) and lamin B (panels H, J, and L) with increasing time after transfection, until at 72 h after transfection (panels F and L) little or no lamin staining could be detected in transfected cells. The appearance of lamins A/C and B at all times after transfection with a kinase-dead US3 expression construct was similar to cells transfected with a wild type US3 construct (compare corresponding of Fig. 7). The ability of US3 to eliminate lamin immunoreactivity from transfected cells does not require kinase activity.

To determine whether the loss of lamin A/C immunoreactivity at late times after US3 and kinase-dead US3 transfection was due to epitope masking of the antibody, a polyclonal lamin A/C antibody was used for confocal microscopy experiments. There was no difference in the lamina phenotype between US3 expressing cells that were processed with monoclonal or polyclonal lamin A/C antibody, making it unlikely that epitope masking is the cause for loss of lamin staining (data not shown).

To confirm that the US3 effect on lamins was specific, Vero cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing the beta-galactosidase gene from an HCMV-MIEP and after 24, 48 and 72 h cells were processed for confocal microscopy. Results at 72 h after transfection are shown in Fig. 7 panels M and N. Beta galactosidase localizes to the cytoplasm and nucleus in transfected cells, similar to US3 in transfected cells. Over-expression of beta galactosidase had very little effect on lamin A/C (panel M) or lamin B (panel N) localization or level of staining.

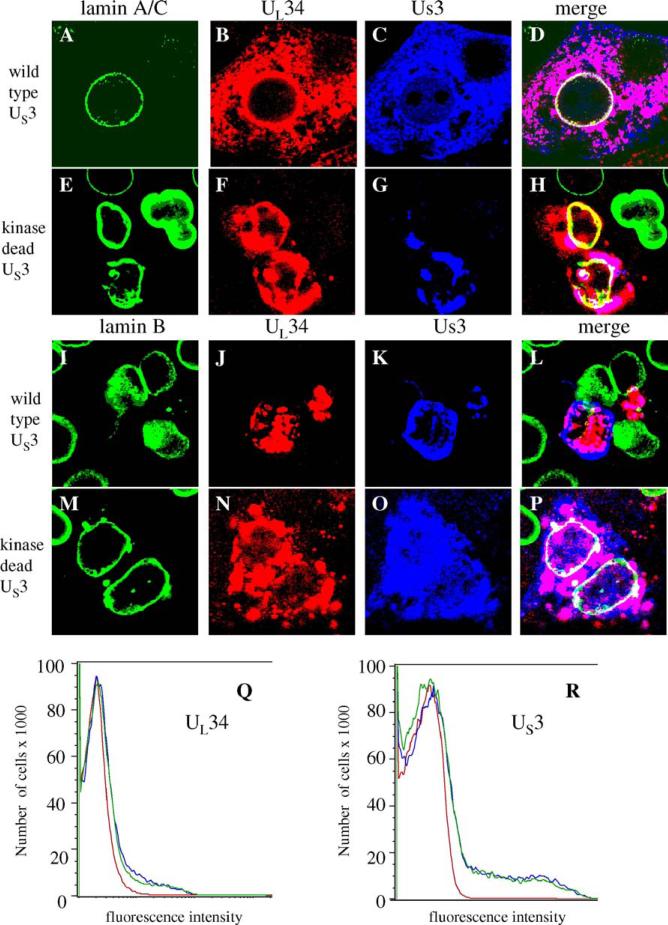

US3 and kinase-dead US3 proteins regulate the lamin-disrupting activity of UL34

Since both UL34 and US3 are able to disrupt the lamina by themselves when expressed in cells, we hypothesized that together the proteins might have enhanced lamin disrupting abilities. To test this hypothesis, we transfected plasmids containing HCMV-MIEP-driven UL34 and either wild type or kinase-dead US3 into cells together and stained for lamin A/C or lamin B, UL34 and US3 72 h after transfection (Fig. 8). Surprisingly, the combined effect of UL34 and US3 proteins on lamin A/C localization was minimal. Lamin A/C colocalized with both UL34 and wild-type US3 at the nuclear membrane in transfected cells (panels A–D). Localization of lamin A/C was not as smooth and regular as seen in mock-infected cells, but there was little evidence of perforations in the lamina or loss of lamin A/C staining. In the case of lamin A/C, UL34 inhibited the effect of US3 on lamins and vice versa so that there was little net effect on the lamina. Similar results were obtained using a kinase dead US3 protein (panels E–H). When UL34 and US3 were expressed together, a subset of both proteins localized to the nuclear membrane, with the remainder of the proteins localizing to the cytoplasm.

Fig. 8.

Regulation of UL34-mediated lamin disruption by co-expression of US3. For all panels, Vero cells were transfected with plasmids expressing UL34 and US3or kinase-dead US3 for 72 h. (A–Q) Digital confocal images showing the localization of UL34, US3 or kinase-dead US3 and lamin A/C or lamin B in Vero cells transfected with plasmids expressing UL34 and US3 or kinase-dead US3. All cells were transfected with UL34-expressing plasmid. The identity of the US3-expressing plasmid is indicated to the left of each row. The protein being detected is indicated above each column of panels. Green: lamins, red: UL34, blue: US3 (Q and R) Cells transfected with UL34 or US3 alone or together were analyzed by flow cytometry. (Q) UL34 staining profile for untransfected cells (red) or cells transfected with UL34 (blue) or UL34 and US3 (green). (R) US3 staining profile for untransfected cells (red) cells transfected with US3 (blue) or US3 and UL34 (green).

As with most transfections, there was a range of expression levels for both the viral proteins. Intense UL34 staining, coupled with low US3 staining in an individual transfected cell was generally, but not exclusively, associated with formation of perforations in the lamin A/C layer, presumably from UL34 activity. Conversely, when US3 staining was relatively high and UL34 expression relatively low, US3 maintained the ability to eliminate lamin A/C staining.

Lamin B localization in UL34 and US3 transfected cells appeared identical to cells transfected only with US3; the lamin B staining was eliminated from the cell (panels I–L). The elimination of staining was seen regardless of the ratio of UL34 to US3, suggesting that the two proteins do not have the ability to regulate themselves when disrupting lamin B localization. These data support earlier observations that the mechanism of lamin A/C and lamin B disruption may be different during HSV infection.

In contrast to cells that express wild type US3 and UL34, cells that express kinase-dead US3 and UL34 showed lamin B localization very similar to lamin A/C localization; very little disruption and no evidence of perforations (panels M–P).

To ensure that the level of UL34 and US3 protein expression in cells where the proteins are expressed together does not differ significantly from levels of expression when the proteins are expressed individually, flow cytometry was used to quantify the amount of staining for both of these proteins in cells that were singly or doubly transfected, allowed to express the protein(s) for 24 h, and then fixed and permeabilized before staining. The staining profiles for cells that were transfected with UL34 alone, or UL34 and US3 together were very similar, as were the staining profiles for cells transfected with US3 alone or UL34 and US3 together (Fig. 8, panels Q and R). Thus, the lack of change in lamin localization in UL34 and US3 doubly transfected cells is not due to lower protein expression than in singly transfected cells.

Total lamin levels are similar between uninfected and infected Vero cells but infected HEp-2 cells have lower lamin protein levels than uninfected cells

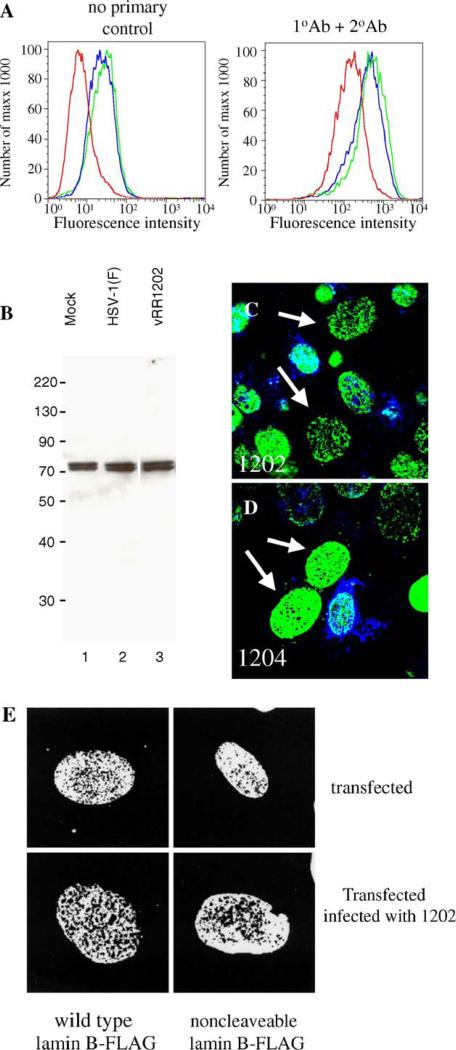

Early during apoptosis lamins are cleaved by caspase 6, which leads to nuclear breakdown and membrane blebbing (Gruenbaum et al., 2000). Since US3 regulates apoptosis, and this function is dependent on kinase activity of the protein, we hypothesized that caspase cleavage of lamins could be responsible for the numerous perforations in the lamina generated in cells infected with vRR1202 and vRR1204. To address these issues, we determined the total amount of lamin A/C and lamin B proteins in infected and uninfected cells. Vero cells were mock-infected for 24 h, or infected with HSV-1(F) or vRR1202. For detecting lamin A/C levels in Vero cells, flow cytometry was used due to inability of the lamin A/C antibodies used to react with Vero protein in western blots (Fig. 9A). The use of a polyclonal antibody made it unlikely that masking or unmasking of epitopes affected the results. Infection of Vero cells with HSV-1(F) or vRR1202 virus results in a small increase in fluorescence. A similar increase was seen when cells were stained without primary antibody (left histogram), suggesting that the increase is not due to alterations of lamin A/C protein levels. There is no decrease in the amount of total lamin A/C in HSV-1(F)-infected and vRR1202-infected cells compared to mock, indicating that disruption of lamin A/C seen in infected cells is not due to loss of a significant amount of lamin A/C protein. For detecting lamin B protein levels in Vero cells, total cellular protein was separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted to nitrocellulose and probed with antibodies to lamin B (Fig. 9B). Coomassie staining of protein extracts was used to equilibrate loading for all samples (not shown). The amounts of total lamin B proteins in mock, HSV-1(F) or vRR1202-infected Vero cells were similar. Also, no cleavage products of lamin B were detected in the western blots (panel B).

Fig. 9.

Disruptions in lamin localization are not accompanied by loss of lamin protein or cleavage of PARP. (A) Lamin A/C protein levels in Vero cells mock-infected (red), or infected with HSV-1(F) (blue) or vRR1202 (green), as analyzed by flow cytometry. The left histogram shows the results of detection with no primary antibody; the right graph shows the results of detection with both primary and secondary antibodies. (B) Lamin B protein levels in Vero cells mock-infected (lane 1), or infected with HSV-1(F) (lane 2) or vRR1202 (lane 3), as analyzed by western blot. Total cellular protein was extracted as described in Materials and methods. Coomassie staining was used to equilibrate loading (not shown). These experiments were done three times. Representative images are shown. Lane 3 is from the same blot and the same exposure as lanes 1 and 2, but was not adjacent to these lanes. (C and D) Digital confocal merged images showing the presence of cleaved PARP positive cells in Vero cells infected with vRR1202 or vR1204 at an MOI of 5 for 24 h. This experiment was done five times. A representative experiment is shown. The infecting virus is indicated on each panel. Green: lamin A/C; blue: cleaved PARP. The arrows point to cells that have perforations in the lamina, but do not stain positive for cleaved PARP. (E) Vero cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing either wild type lamin B-FLAG or non-cleavable lamin B-FLAG, then mock-infected or infected with vRR1202. The identity of the transfecting plasmid is indicated below each column. The state of infection is indicated to the right of each row.

Since infection with vRR1202 resulted in an increased number of apoptotic cells, and the activation of this pathway might be responsible for generating perforations in the lamina, we used confocal microscopy to see whether cells that contained perforations in the lamina network also stained positive for cleaved PARP. PARP is cleaved by caspases, probably caspase 3, early during apoptosis (Villa et al., 1997). It is unlikely that either lamin A/C or lamin B themselves is cleaved by caspase 3, but caspase 6 is known to cleave lamins during apoptosis and PARP cleavage is upstream of this event (Villa et al., 1997). Detection of cleaved PARP has previously been used to identify apoptotic cells (Duriez and Shah, 1997; Simbulan-Rosenthal et al., 1998), and US3 has been shown to prevent cleavage of PARP in cells induced to -undergo apoptosis (Ogg et al., 2004). Vero cells were infected for 24 h with vRR1202 and vRR1204, processed for confocal microscopy, and immunostained for lamin A/C or lamin B and cleaved PARP (Figs. 9C and D). Only a minority of cells infected with either US3 mutant virus stained PARP positive, indicating that these cells were in the beginning stages of apoptosis. More apoptotic cells were observed in US3-null or kinase-dead US3-infected cultures than in wild-type infected cultures because US3 has been shown to protect from apoptosis in wild type HSV, and without this gene present, the virus causes an increased level of apoptosis among infected cells (Leopardi et al., 1997). However, nearly 100% of the cells contained perforations in the lamin A/C layer. Arrows in Figs. 9C and D indicate cells with extensive lamin disruption that did not stain for cleaved PARP. Most cells containing holes in the lamina did not stain positive for cleaved PARP, which suggests that apoptotic activation of the caspase pathways is not required to form holes in the lamina.

To further investigate the role of apoptotic lamin cleavage in generating the perforations observed during HSV-1 infection and transfection with viral proteins, Vero cells were transfected with plasmids encoding FLAG-tagged wild type lamin B or lamin B in which the caspase-6 cleavage site was mutated to render it non-cleavable (Rao et al., 1996), and then stained with anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 9E). In mock-infected cells, neither the wild type or non-cleavable lamin B-FLAG constructs showed evidence of perforations in the lamin layer, but infection with vRR1202 resulted in the presence of numerous perforations in the lamin B layer regardless of whether wild type or non-cleavable lamin B was expressed.

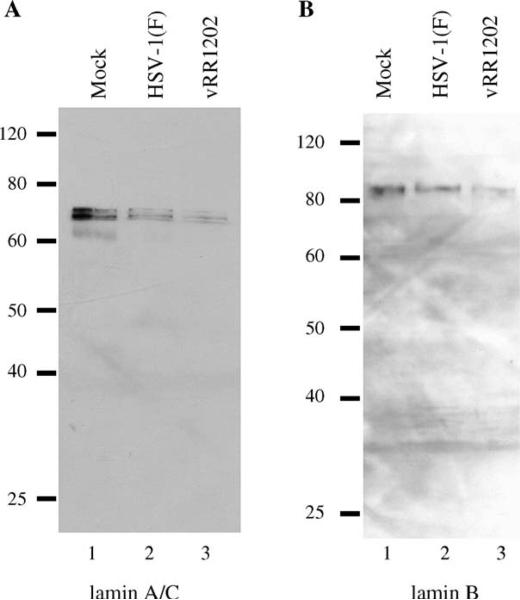

We also determined the total amount of lamin A/C and lamin B proteins in infected and uninfected HEp-2 cells. HEp-2 cells were mock-infected for 24 h, or infected with HSV-1(F) or vRR1202. For detecting lamin A/C and lamin B protein levels, total cellular protein was separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted to nitrocellulose and probed with antibodies to lamin A/C and lamin B (Figs. 10A and B, respectively). Coomassie staining of protein extracts was used to equilibrate loading for all samples (not shown). Despite very similar appearances of the lamin layers in confocal microscopy studies of Vero and HEp-2 cells, both HSV-1(F) and vRR1202-infected HEp-2 cells had less lamin A/C (panel A) and lamin B (panel B) than in mock-infected cells. More specifically, there was less lamin protein in HSV-1(F)-infected cells than mock-infected cells, and less lamin protein in vRR1202-infected cells than in HSV-1(F)-infected cells. These results suggest that the less intense lamin staining observed in confocal micrographs of vRR1202-infected cells may be the result of less lamin protein in the cell.

Fig. 10.

Lamin disruption in infected HEp-2 cells is associated with loss of lamin protein. Shown are digital images of western blots of protein from HEp-2 cells infected for 24 h probed for lamin A/C (A) and lamin B (B). Coomassie staining was used to equilibrate loading (not shown). These experiments were done three times. Representative images are shown. The infecting virus is indicated above each lane.

Additionally, there were no visible cleavage products for either of the lamin proteins in HEp-2 cells, which would indicate that caspases were actively cleaving lamins. Cleavage of lamin A and C by caspase 6 results in protein fragments of 47 and 37 kDa molecular weights, and cleavage of lamin B results in the generation of a 45 kDa fragment (Rao et al., 1996). The absence of these lamin cleavage products supports the hypothesis that in HEp-2 cells, diminished staining of lamin A/C and lamin B proteins in HSV infected-cell lysates is the result of lower total protein levels of lamins in the cells, but not the result of caspase-mediated cleavage.

Discussion

Results presented in this paper demonstrate that wild-type herpes simplex virus infection results in disruption of both A/C and B type lamins. The disruption of lamin A/C organization is consistent with earlier studies (Reynolds et al., 2004; Scott and O'Hare, 2001; Simpson-Holley et al., 2004); the disruption of lamin B organization is a novel finding. Since B lamins, unlike lamins A and C, are expressed in all cell types, and since HSV infects multiple cell types during pathogenesis, it is not surprising that this virus has developed mechanisms for disrupting lamin B organization. HSV-mediated effects on lamin A/C have been shown to include changes in accessibility of specific monoclonal antibody epitopes (Reynolds et al., 2004). The limited UL34-dependent changes in nuclear shape and distribution of lamin A/C observed in wild-type-infected cells reported here are also evident in cells stained with polyclonal lamin A/C antibody shown by Reynolds et al. Both the changes in monoclonal reactivity and the changes in lamin distribution are consistent with HSV-dependent alterations of lamin conformation, interactions, or both. Disruption of both A/C and B type lamins depends on the expression of the viral UL34 protein. Primary envelopment of capsids at the inner nuclear membrane also strongly depends upon UL34. The dependence of both capsid envelopment and lamin disruption on UL34 suggests that these processes are functionally connected. One reasonable hypothesis is that lamin disruption is required for capsid access to the inner nuclear membrane for envelopment. Alternatively, lamin disruption could be the result of primary envelopment.

We have also found that expression of the US3 protein in infected cells is not necessary for disruption of either lamin A/C or lamin B organization. In fact, failure to express US3 in the context of a viral infection results in more extensive disruption of both lamin types, suggesting that US3 may function as a negative regulator of lamina disruption. This regulatory role of US3 requires its kinase activity, since infection with recombinant virus carrying a specific mutation that results in expression of US3 protein without kinase activity showed the same phenotype as the US3-null virus. Surprisingly, US3-mediated regulation of lamina disruption is not mediated by phosphorylation of UL34, indicating the existence of some other substrate critical to this process.

In HSV-1 and HSV-2, viruses that fail to express US3 have been shown to be defective in their ability to protect infected cells from apoptosis (Asano et al., 1999; Aubert et al., 1999; Galvan and Roizman, 1998; Leopardi et al., 1997; Ogg et al., 2004). This defect is reflected in a somewhat elevated frequency of apoptotic cells in cultures that are infected with deletion virus, but are otherwise unstressed (Aubert et al., 1999). The defect is only dramatically evident in the inability of US3-null viruses to protect infected cells from a variety of pro-apoptotic insults. Disruption of the nuclear lamina occurs late in apoptosis and is the result of the activation of effector caspases and subsequent cleavage of the lamins (Gruenbaum et al., 2005). Although enhanced lamin disruption as a result of elevated apoptosis would be an economical explanation for the phenotype of the US3-null virus, the following considerations suggest that it is untrue, at least in Vero cells. (i) Consistent with previous reports, we observed evidence of apoptosis in only a minority of cells infected with US3-null virus, whereas enhanced lamina disruption was observed in all cells infected with either US3-null virus or recombinant virus that expresses catalytically inactive US3. (ii) In Vero cells, no loss of full-length lamins was observed following infection with US3-null virus, and none of the cleavage products expected from caspase-mediated lamin cleavage were seen. (iii) Incorporation of mutant lamins that are not cleavable by caspases into the lamina had no effect on the enhanced disruption of the nuclear lamins. It seems most likely that the function of US3 in regulating disruption of the lamina is distinct from its role as a regulator of apoptosis. Loss of lamins is observed in infected HEp-2 cells and is not associated with accumulation of products of caspase cleavage, but our data do not rule out involvement of apoptotic lamin cleavage in HEp-2 cells, and further study of the mechanism of lamin loss is necessary.

The behavior of the nuclear lamina in cells infected with wild-type or recombinant viruses is consistent with the hypothesis that UL34 has the ability to disrupt the organization of the lamina and US3 is able to negatively regulate that activity. Transient expression of UL34 has previously been show to cause disruption of lamin A/C localization (Reynolds et al., 2004). We show here that expression of UL34 is also sufficient to disrupt lamin B localization. The ability of UL34 to cause disruptions in the lamina depended on the level of protein expression in each cell. Cells expressing high levels of UL34, as determined by staining intensity, showed numerous perforations in both lamin A/C and lamin B, while cells expressing less of the protein showed fewer, smaller perforations (not shown). Surprisingly, the effect of UL34 expression on lamin A/C and lamin B distribution differed slightly. Both types of lamins developed perforations, but those in the lamin A/C layer developed more quickly (compare Fig. 6 panels M and EE). A greater level of UL34 expression was required to obtain a similar number and size of perforations in the lamin B layer. These results may reflect a difference in the mechanism UL34 uses to disrupt lamins.

Previously published experiments did not control for the effect of high-level expression of intrinsic membrane proteins. We have done so here and find that overexpression of a variety of intrinsic membrane proteins can also mediate disruption of localization of both lamin B and lamin A/C. Regulation of UL34-mediated lamin disruption by US3 does not depend on the kinase activity of US3 protein, suggesting that this regulatory effect may be due to direct or indirect physical interaction between these proteins.

One unexpected outcome of these experiments is the observation that expression of US3 protein in the absence of other viral proteins also severely disrupts the organization of both A/C and B type lamins. The lamin disrupting activity of US3 protein does not require its catalytic activity. While lamin A/C staining in US3 expressing cells was often absent at 72 h after transfection, cells stained for lamin B showed small, punctate patches of staining in the nucleus, which may represent the ability of US3 to target lamin B to specific locations within the cell. The disruption of lamin organization by US3 and UL34 suggests the possibility that lamin disruption in the wild-type infected cell result from the combined actions of UL34 and US3 proteins, and that the disruption is limited by a regulatory interaction between them. In the infected cell, the lamin-disrupting activity of US3 must also be limited by factors other than UL34, since US3 does not mediate wholesale destruction of the nuclear lamina in UL34-null virus-infected cells.

The perforations in the nuclear lamina in US3-null or kinase-dead US3- infected cells are associated with accumulations of UL34 and US3. The accumulations of UL34 have been previously shown to correspond to accumulations of enveloped virions in distended spaces between the inner and outer nuclear membranes. These virions are heavily labeled with anti-UL34 antibody in immunogold TEM experiments, suggesting that much of the accumulated UL34 is incorporated into the trapped virions. In cells that express the UL34 gene from transfected plasmid, perforations in the lamina are formed, but are not associated with accumulations of UL34 protein (Fig. 6), presumably because UL34-containing, enveloped virus particles are not being formed and trapped in the perinuclear space. The accumulation of perinuclear virions at discrete sites in the nuclear envelope of US3 mutant infected cells, and the association of those sites with perforations in the nuclear lamina raises the possibility that perforations in the lamina create “hot spots” for envelopment where capsids have unimpeded access to the inner nuclear membrane.

The results presented here are consistent with the idea that capsid access to the inner nuclear membrane for primary envelopment depends upon rearrangement or removal of nuclear lamina components. This hypothesis would require that the virus have a mechanism for disrupting the organization of lamin B as observed here, since lamin B proteins are expressed and incorporated into the nuclear lamina in all cell types. Interestingly, our results also suggest that it is advantageous to the virus to limit the extent of that disruption. This also should not be surprising. In addition to its role as a structural framework for the nucleus, roles for the nuclear lamina and lamina constituents have been found in control of transcription (reviewed in Gruenbaum et al., 2005). Herpes-viruses rely on the host cell transcription machinery, modulated by viral proteins, for the expression of viral genes. Wholesale disruption of any important component of that host cell machinery might be expected to impair virus gene expression and replication.

Although the mechanism of lamin disruption by UL34 or US3 is not yet clear, in both cases it seems most likely that these activities depend upon interactions made by these proteins rather than catalytic activity. Identification of cellular interaction partners for both proteins is thus a high priority. UL34 protein has been shown to interact directly with lamin A/C in vitro (Reynolds et al., 2004). Regulation of lamin disruption by US3 in the infected cell does require the protein's catalytic activity. Our results suggest that UL34 is not the relevant substrate for this activity. It has recently been shown that that UL31 protein is a substrate for US3 (Kato et al., 2005). UL31 protein is also a component of the envelopment apparatus and is involved in alteration of lamin A/C organization in the infected cell (Reynolds et al., 2004), These results suggest the hypothesis that US3 may affect the lamin disrupting function of the envelopment apparatus by UL31 phosphorylation.

Materials and methods

Cells and viruses

HEp-2 and Vero cells were maintained as previously described (Roller et al., 2000). The properties of HSV-1(F), vRR1072 (thymidine kinase positive UL34-null virus), vRR1202 (US3-null virus), vRR1204 (US3 kinase dead mutant virus), vRR1205 (non-phosphorylatable UL34 mutant virus) and repair viruses for vRR1072 and vRR1202 were previously described and characterized (Reynolds et al., 2001; Ryckman and Roller, 2004). No repair virus was used for vRR1204; two independently isolated clones of this virus were used in parallel for all experiments and yielded identical results.

Plasmids

Plasmid pRR1098 contains the HSV-1(F) US3 open reading frame (ORF) under the control of the human cytomegalovirus immediate early promoter (HCMV-MIEP) and was described previously (Reynolds et al., 2001). Plasmid pRR1203 encodes the HSV-1(F) US3 gene in which lysine 220 is mutated to alanine (K220A) and was also previously described (Ryckman and Roller, 2004). Plasmid pRR1062 contains the HSV-1(F) UL34 gene under the control of the HCMV-MIEP and was described by Reynolds et al. (2001). Plasmid cDNA3/CD4 was generated by using PCR to amplify the CD4 cDNA with LH 5′ TGCGAATCCAAGCCCAGAGCCCGCCATTTC 3′ and RH 5′ TTGCTGAATTCGGATCCAAATGAGCAGTGGGG 3′ primers to clone into the EcoRI site of pCDNA3. The plasmid pCMVβ (beta galactosidase ORF expressed by HCMV-MIEP) was obtained from Mark Stinski. The wild type lamin B-FLAG fusion construct was obtained from Eileen White (Rao et al., 1996). The non-cleavable lamin B-FLAG fusion was constructed using PCR mutagenesis (Bjerke et al., 2003) to generate a lamin B insert with amino acid 186 changed to alanine, making lamin B non-cleavable. The following primers were used to introduce the alanine mutation and a BspEI site: laminBcleaveright 5′ AATTGACGTCCGGAATCCACCCACCAAGCGCGTTTCATGCTTC 3′ and laminBcleaveleft 5′ GAGGTGGCTTCCGGACGCAAATTGAGTACAAGCTGGCGCAA 3′. The outside pair of primers was laminBBlp 5′ CACGCCGCGAGCCCCAC 3′ and laminBXhoI5′ GCCATCTCGAGTACATAATTGCACAGCTTCTATTGGATGCTCTGGGG 3′.

Transfections and infections

For immunofluorescence (IF) experiments, 70% confluent cultures of Vero cells in 24-well dishes were transfected with 250 ng of total plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine as described by the manufacturer (Gibco-BRL) and incubated at 37 °C overnight or for 24, 48 or 72 h. Infections were done for 24 h at an MOI of 5 unless otherwise noted.

Indirect immunofluorescence

If was performed as previously described, with some variations (Reynolds et al., 2001). Cells stained for lamin A/C were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 20 min and then washed with PBS (phosphate buffered saline). Due to masking of lamin B epitopes when cells were fixed with formaldehyde, cells stained for lamin B were fixed with cold methanol for 20 min and then washed with PBS. Cells were permeabilized and blocked in the same step by incubating in 10% Blokhen (Aves Labs) in IF buffer. During US3 staining, pooled human immunoglobulin was also added to the blocking solution to further eliminate background Fc receptor staining (Reynolds et al., 2002). Primary antibodies were diluted as follows in IF buffer: chicken anti-UL34 (1:1000), rabbit anti-US3 (1:750), rabbit anti-US11 (1:200), mouse monoclonal IgG anti-lamin A/C (1:1000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), chicken polyclonal anti-lamin A/C (1:200) (gift from Joel Baines), rabbit polyclonal anti- poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) Fragment p85 (1:300) (Promega), mouse monoclonal IgG anti-lamin B (1:50) (Oncogene Research Products), mouse anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal IgG1 (1:8000) (Sigma), rabbit anti-beta galactosidase (1:1000) (Chemicon International), and goat anti-hCD4 (1:400) (R and D Systems). Secondary antibodies were also diluted in IF buffer as follows: AlexaFluor 594 goat anti-chicken IgG (1:1000) was used to detect UL34 and polyclonal lamin A/C, AlexaFluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (1:400) was used to detect the lamin antibodies and FLAG epitope, Texas Red goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugate (1:200) was used to detect US11 and US3, and AlexaFluor 660 goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugate (1:400) was used to detect US3, PARP and beta galactosidase (all secondary antibodies from Molecular Probes). For the CD4 experiments the following antibodies were diluted in IF buffer: AlexaFluor 488 donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:400) was used to detect lamins, AlexaFluor 594 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:400) was used to detect US3 and AlexaFluor 647 donkey anti-goat IgG (1:400) was used to detect CD4. Slo-fade II was used to mount coverslips on glass slides. All confocal microscopy work was done with a Zeiss 510 confocal microscope. All images shown are representative of experiments performed a minimum of three times.

Flow cytometry

For the UL34 and US3 experiments, 70% confluent cultures of Vero cells in 6-well dishes were transfected with 1.25 μgof UL34, US3 or a combination of UL34 and US3 DNA using Lipofectamine as described by the manufacturer (Gibco-BRL) and incubated at 37 °C overnight. For the lamin A/C experiment, 100% confluent cultures of Vero cells in 6-well dishes were mock infected, or infected with HSV-1(F) or US3-null virus at an MOI of 10 for 24 h. For all experiments, the cells were detached with trypsin and washed with Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (DMEM). The cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 15 min, and then washed once with DMEM and once with PBS. The cells were incubated with IF buffer for 10 min and then antibodies to UL34, US3 or both proteins were added at dilutions of 1:500 for 1 h. The cells were washed twice with PBS and then AlexaFluor 660 goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugate was added to detect US3 and AlexaFluor 594 goat anti-chicken IgG was added to detect UL34, both at 1:400 dilutions. For the lamin A/C experiment, a chicken polyclonal lamin A/C antibody was used at 1:200 and detected with fluorescein goat anti-chicken IgY at 1:1000 (Aves Labs). The cells were washed twice with PBS and fluorescent cells were quantified using the Cell-Quest Pro software package (Becton Dickinson, Inc.) on a FACSCaliber (Becton Dickinson, Inc.) instrument and analyzed with the FlowJo version 3.4 software package (Tree Star, Inc.).

Nuclear extraction and western blotting

Cell extracts and nuclear matrix fractions were prepared by a modification of the procedure described by Markiewicz et al. (2002). Confluent six-well cultures of Vero or HEp-2 cells were infected with 5 PFU/cell of virus for 24 h. Infected cells were washed once with PBS, scraped into 1 ml PBS and pelleted by centrifugation at 400 × g for 2 min in a microcentrifuge. The cell pellet was resuspended in 0.2 ml CSK [10 mM HEPES pH 6.8, 0.3 M sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM Dithiothreitol, 1% Triton X-100 and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)] with 100 mM NaCl and placed on ice for 5 min to lyse the cells. Nuclei were collected by centrifugation at 400 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was saved as the cytoplasmic fraction. Nuclei were resuspended in 0.2 ml CSK containing 50 mM NaCl, 50 mg/ml RNase A and 500 U DNase I and digested for 30 min at room temperature. Ammonium sulfate was added to a concentration of 0.25 M and proteins were extracted on ice for 5 min. Nuclei were collected by centrifugation at 400 × g for 5 min and the supernatant was saved. The pellet containing the nuclear matrix fraction was dissolved in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. For comparison of total cellular lamins, equal volumes of each of the three fractions were combined for loading. Equal loading of lanes was confirmed by comparison of parallel lanes stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Mark Stinski, Charles Grose, Paul Ogg and members of the Roller laboratory for helpful discussions and reading of the manuscript. We thank Bernard Roizman for supplying the rabbit US3 antibody, Wendy Maury for supplying CD4 antibodies, Eileen White for supplying the lamin B-FLAG plasmid, and Joel Baines for supplying the polyclonal lamin A/C antibody. We would like to thank Katie Stein for constructing the pCDNA3/CD4 plasmid. We thank Paul Ogg for technical assistance with the flow cytometry experiments. These studies were supported by the University of Iowa and Public Health Service award AI 41478.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.053.

References

- Asano S, Honda T, Goshima F, Watanabe D, Miyake Y, Sugiura Y, Nishiyama Y. US3 protein kinase of herpes simplex virus type 2 plays a role in protecting corneal epithelial cells from apoptosis in infected mice. J. Gen. Virol. 1999;80:51–56. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-1-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano S, Honda T, Goshima F, Nishiyama Y, Sugiura Y. US3 protein kinase of herpes simplex virus protects primary afferent neurons from virus-induced apoptosis in ICR mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2000;294:105–108. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01554-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubert M, O'Toole J, Blaho J. Induction and prevention of apoptosis in human HEp-2 cells by herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 1999;73:10359–10370. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10359-10370.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baines JD, Roizman B. The UL11 gene of herpes simplex virus 1 encodes a function that facilitates nucleocapsid envelopment and egress from cells. J. Virol. 1992;66:5168–5174. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.5168-5174.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benetti L, Munger J, Roizman B. The herpes simplex virus 1 US3 protein kinase blocks caspase-dependent double cleavage and activation of the proapoptotic protein BAD. J. Virol. 2003;77:6567–6573. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.11.6567-6573.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerke S, Cowan J, Kerr J, Reynolds A, Baines J, Roller R. Effects of charged cluster mutations on the function of herpes simplex virus type 1 UL34 protein. J. Virol. 2003;77(13):7601–7610. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7601-7610.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M, MacLean AR, Aitken JD, Harland J. ICP34.5 influences herpes simplex virus type 1 maturation and egress from infected cells in vitro. J. Gen. Virol. 1994;75:3679–3686. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-12-3679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calton CM, Randall JA, Adkins MW, Banfield BW. The pseudorabies virus serine/threonine kinase Us3 contains mitochondrial, nuclear and membrane localization signals. Virus Genes. 2004;29:131–145. doi: 10.1023/B:VIRU.0000032796.27878.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier A, Komai T, Masucci MG. The Us3 protein kinase of herpes simplex virus 1 blocks apoptosis and induces phosphorylation of the Bcl-2 family member Bad. Exp. Cell Res. 2003;291:242–250. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison AJ, Scott JE. The complete DNA sequence of varicella-zoster virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1986;67:1759–1816. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-9-1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai P. A null mutation in the UL36 gene of herpes simplex virus type 1 results in accumulation of unenveloped DNA-filled capsids in the cytoplasm of infected cells. J. Virol. 2000;74:11608–11618. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11608-11618.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai P, Sexton G, McAffrey J, Person S. A null mutation in the gene encoding the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL37 polypeptide abrogates virus maturation. J. Virol. 2001;75:10259–10271. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10259-10271.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan A, Jamieson FE, Cunningham C, Barnett BC, McGeoch DJ. The genome sequence of herpes simplex virus type 2. J. Virol. 1998;72:2010–2021. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2010-2021.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duriez P, Shah G. Cleavage of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase: a sensitive parameter to study cell death. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1997;75:337–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina A, Feederle R, Raffa S, Gonnella R, Santarelli R, Frati L, Angeloni A, Torrisi MR, Faggioni A, Delecluse HJ. BFRF1 of Epstein-Barr virus is essential for efficient primary viral envelopment and egress. J. Virol. 2005;79:3703–3712. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3703-3712.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favoreel HW, Van Minnebruggen G, Adriaensen D, Nauwynck HJ. Cytoskeletal rearrangements and cell extensions induced by the US3 kinase of an alphaherpesvirus are associated with enhanced spread. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:8990–8995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409099102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan V, Roizman B. Herpes simplex virus 1 induces and blocks apoptosis at multiple steps during infection and protects cells from exogenous inducers in a cell-type-dependent manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:3931–3936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geenen K, Favoreel HW, Olsen L, Enquist LW, Nauwynck HJ. The pseudorabies virus US3 protein kinase possesses anti-apoptotic activity that protects cells from apoptosis during infection and after treatment with sorbitol or staurosporine. Virology. 2005;331:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerace L, Blobel G. The nuclear envelope lamina is reversibly depolymerized during mitosis. Cell. 1980;19:277–287. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman R, Gruenbaum Y, Moir R, Shumaker D, Spann T. Nuclear lamins: building blocks of nuclear architecture. Genes Dev. 2002;16:533–547. doi: 10.1101/gad.960502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granzow H, Klupp B, Fuchs W, Veits W, Osterrieder N, Mettenleiter T. Egress of alphaherpesviruses: comparative ultrastructural study. J. Virol. 2000;73:3675–3684. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3675-3684.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granzow H, Klupp BG, Mettenleiter TC. The pseudorabies virus US3 protein is a component of primary and of mature virions. J. Virol. 2004;78:1314–1323. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1314-1323.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenbaum Y, Wilson KL, Harel A, Goldberg M, Cohen M. Review: nuclear lamins—Structural proteins with fundamental functions. J. Struct. 2000:313–323. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenbaum Y, Margalit A, Goldman R, Shumaker D, Wilson K. The nuclear lamina comes of age. Nat. Rev., Mol. Biol. 2005;6:21–31. doi: 10.1038/nrm1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata S, Koyama AH, Shiota H, Adachi A, Goshima F, Nishiyama Y. Antiapoptotic activity of herpes simplex virus type 2: the role of US3 protein kinase gene. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:601–607. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holaska J, Wilson KL, Mansharamani M. The nuclear envelope, lamins and nuclear assembly. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002;14:357–364. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmer L, Worman HJ. Inner nuclear membrane proteins: functions and targeting. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2001;58:1741–1747. doi: 10.1007/PL00000813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson L, Johnson DC. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein K promotes egress of virus particles. J. Virol. 1995;69:5401–5413. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5401-5413.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerome KR, Fox R, Chen Z, Sears AE, Lee H, Corey L. Herpes simplex virus inhibits apoptosis through the action of two genes, Us5 and Us3. J. Virol. 1999;73:8950–8957. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.8950-8957.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato A, Yamamoto M, Ohno T, Kodaira H, Nishiyama Y, Kawaguchi Y. Identification of proteins phosphorylated directly by the Us3 protein kinase encoded by herpes simplex virus 1. J. Virol. 2005;79:9325–9331. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.9325-9331.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klupp BG, Mettenleiter TC. Primary envelopment of pseudorabies virus at the nuclear membrane requires the UL34 gene product. J. Virol. 2000;74:10063–10073. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.21.10063-10073.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klupp BG, Granzow H, Mettenleiter TC. Effect of the pseudorabies virus US3 protein on nuclear membrane localization of the UL34 protein and viral egress from the nucleus. J. Gen. Virol. 2001;82:2363–2371. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-10-2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopardi R, Van Sant C, Roizman B. The herpes simplex virus 1 protein kinase US3 is required for protection from apoptosis induced by the virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997;94:7891–7896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markiewicz E, Venables R, Mauricio-Alvarez-Reyes R, Quinlan R, Dorobek M, Hausmanowa-Petrucewicz I, Hutchison C. Increased solubility of lamins and redistribution of lamin C in X-linked Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy fibroblasts. J. Struct. Biol. 2002;140(1–3):241–253. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(02)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki A, Yamauchi Y, Kato A, Goshima F, Kawaguchi Y, Yoshikawa T, Nishiyama Y. US3 protein kinase of herpes simplex virus type 2 is required for the stability of the UL46-encoded tegument protein and its association with virus particles. J. Gen. Virol. 2005;86:1979–1985. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80949-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeon F, Kirschner MW, Caput D. Homologues in both primary and secondary structure between nuclear envelope and intermediate filament proteins. Nature. 1986;319:463–468. doi: 10.1038/319463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman K, Sherburne R, Lavery C, Duncan J, Smiley J. Evidence that herpes simplex virus VP16 is required for viral egress downstream of the initial envelopment event. J. Virol. 2000;74(14):6287–6299. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6287-6299.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger J, Roizman B. The US3 protein kinase of herpes simplex virus 1 mediates the posttranslational modification of BAD and prevents BAD-induced programmed cell death in the absence of other viral proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:10410–10415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181344498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muranyi W, Haas J, Wagner M, Krohne G, Koszinowski U. Cytomegalovirus recruitment of cellular kinases to dissolve the nuclear lamina. Science. 2002;297:854–857. doi: 10.1126/science.1071506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T, Goshima F, Daikoku T, Takakuwa H, Nishiyama Y. Expression of herpes simplex virus type 2 US3 affects the Cdc42/Rac pathway and attenuates c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation. Genes Cells. 2000;5:1017–1027. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T, Goshima F, Yamauchi Y, Koshizuka T, Takakuwa H, Nishiyama Y. Herpes simplex virus type 2 US3 blocks apoptosis induced by sorbitol treatment. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:707–712. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01590-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer A, Rudolph J, Brandmüller C, Just F, Osterrieder N. The equine herpesvirus 1 UL34 gene product is involved in an early step in virus egress and can be efficiently replaced by a UL34-GFP fusion protein. Virology. 2002;300:189–204. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg P, McDonell P, Ryckman B, Knudson CM, Roller R. The HSV-1 Us3 protein kinase is sufficient to block apoptosis induced by overexpression of a variety of Bcl-2 family members. Virology. 2004;319(2):212–224. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterrieder N, Neubauer A, Brandmuller C, Kaaden OR, O'Callaghan DJ. The equine herpesvirus 1 IR6 protein that colocalizes with nuclear lamins is involved in nucleocapsid egress and migrates from cell to cell independently of virus infection. J. Virol. 1998;72:9806–9817. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9806-9817.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter M, Nakagawa J, CDoree M, Labbe J, Nigg A. In Vitro Disassembly of the Nuclear Lamina and M Phase-Specific Phosphorylation of Lamins by cdc2 Kinase. Cell. 1990;61:591–602. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90471-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon AP, Roizman B. Herpes simplex virus 1 ICP22 regulates the accumulation of a shorter mRNA and of a truncated US3 protein kinase that exhibits altered functions. J. Virol. 2005;79:8470–8479. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8470-8479.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves FC, Spector D, Roizman B. The herpes simplex virus 1 protein kinase encoded by the Us3 gene mediates posttranslational modification of the phosphoprotein encoded by the UL34 gene. J. Virol. 1991;65:5757–5764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5757-5764.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves FC, Spector D, Roizman B. UL34, the target of the herpes simplex virus Us3 protein kinase, is a membrane protein which in its unphosphorylated state associates with novel phosphoproteins. J. Virol. 1992;66:4295–4303. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4295-4303.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao L, Perez D, White E. Lamin proteolysis facilitates nuclear events during apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 1996;135:1441–1455. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A, Ryckman B, Baines J, Zhou Y, Liang L, Roller R. UL31 and UL34 proteins of herpes simplex virus type 1 form a complex that accumulates at the nuclear rim and is required for envelopment of nucleocapsids. J. Virol. 2001;75(18):8803–8817. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.18.8803-8817.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A, Wills EG, Roller R, Ryckman B, Baines J. Ultrastructural localization of the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL31, UL34 and US3 proteins suggests specific roles in primary envelopment and egress of nucleocapsids. J. Virol. 2002;76:8939–8952. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.17.8939-8952.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A, Liang L, Baines J. Conformational changes of the nuclear lamina induced by herpes simplex virus 1 requires genes UL31 and UL34. J. Virol. 2004;78:5564–5575. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5564-5575.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roller RJ, Zhou Y, Schnetzer R, Ferguson J, DeSalvo D. Herpes simplex virus type 1 UL34 gene product is required for viral envelopment. J. Virol. 2000;74:117–129. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.117-129.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckman B, Roller RJ. Herpes simplex virus type 1 primary envelopment: UL34 protein modification and the US3-UL34 catalytic relationship. J. Virol. 2004;78(1):399–412. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.1.399-412.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher D, Tischer BK, Trapp S, Osterrieder N. The protein encoded by the US3 orthologue of Marek's disease virus is required for efficient de-envelopment of perinuclear virions and involved in actin stress fiber breakdown. J. Virol. 2005;79:3987–3997. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.3987-3997.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott E, O'Hare P. Fate of the inner nuclear membrane protein lamin B receptor and nuclear lamins in herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 2001;18:8818–8830. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.18.8818-8830.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simbulan-Rosenthal C, Rosenthal D, Iyer S, Boulares A, Smulson M. Transient poly (ADP-ribosyl)ation of nuclear proteins and role of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase in the early stages of apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:13703–13712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson-Holley M, Baines J, Roller R, Knipe D. Herpes simplex virus 1 UL34 and UL31 promote the late maturation of viral replication compartments to the nuclear periphery. J. Virol. 2004;78 doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5591-5600.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima Y, Tamura H, Xuan X, Otsuka H. Identification of the US3 gene product of BHV-1 as a protein kinase and characterization of BHV-1 mutants of the US3 gene. Virus Res. 1999;59:23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(98)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telford EA, Watson MS, McBride K, Davison AJ. The DNA sequence of equine herpesvirus-1. Virology. 1992;189:304–316. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90706-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L, Bollen M, Fields AP. Identification of protein phosphatase 1 as a mitotic lamin phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272(47):29693–29697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa P, Kaufmann S, Earnshaw W. Caspases and caspase inhibitors. Top. Biol. Sci. 1997;22:388–393. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar F, Pol JM, Peeters B, Gielkens AL, de Wind N, Kimman TG. The US3-encoded protein kinase from pseudorabies virus affects egress of virions from the nucleus. J. Gen. Virol. 1995;76:1851–1859. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-7-1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye G, Vaughan K, Vallee R, Roizman B. The herpes simplex virus type 1 UL34 protein interacts with a cytoplasmic dynein intermediate chain and targets nuclear membrane. J. Virol. 2000;74(3):1355–1363. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.3.1355-1363.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.