Abstract

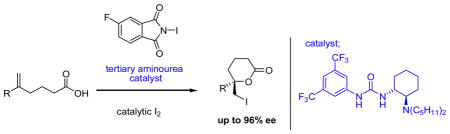

Binding the anion: A highly enantioselective iodolactonization of 5-hexenoic acids has been achieved using a tertiary aminourea-catalyst. The use of catalytic iodine in this process is critical to enhancing both the reactivity and enantioselectivity of the stoichiometric I+source.The mechanism is proposed to involve binding of an iodonium imidate intermediate by the H-bond donor catalyst.

Keywords: asymmetric catalysis, iodolactonization, halogenation, organocatalysis, anion binding

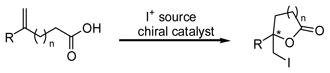

The intramolecular reaction of carboxylic acids with pendant olefins in the presence of a source of I+ – the iodolactonization reaction – is a powerful method for the generation of five- and six-membered lactones (eq 1). Diastereoselective variants of this reaction provide efficient access to stereochemically defined lactones, and consequently this reaction has found widespread use in natural products synthesis.[1] In contrast, the development of catalytic enantioselective variants has proved challenging,[2],[3] a problem likely associated with the inherent difficulty of controlling the reactivity of iodonium ion intermediates through intermolecular interactions.[4]

|

(1) |

The recent discovery of anion-binding mechanisms in H-bonding catalysis[5] has opened the door to the development of asymmetric catalytic methods that engage reactive cationic intermediates such as N-acyliminum ions,[6] N-protioiminium ions,[7] acylpyridinium ions,[8] aziridinium ions,[9] and oxocarbenium ions.[10] We were intrigued by the possibility that analogous pathways might be available to iodonium ions, thereby providing the control over halonium ion reactivity that is necessary for enantioselective iodolactonization and related reactions. Herein, we report the successful application of such a strategy in the development of a tertiary aminourea-catalyzed asymmetric iodolactonizationreaction.

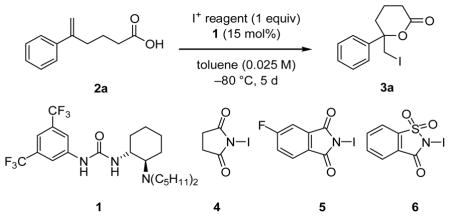

The iodolactonization of hexenoic acid derivtive 2a was selected as a model reaction for catalyst and reagent screening studies. A broad survey of potential H-bond donor catalysts revealed that bifunctional tertiary aminourea derivatives were required to induce useful levels of catalysis. A sharp dependence on the amino group substituents was observed, with di-n-pentyl derivative 1 affording highest enantioselectivities.[11] Whereas N-iodoimides or I2 alone proved poorly reactive (Table 1, entries 1–4), the combination of stoichiometric levels of an N-iodoimide derivative and catalytic I2 was found to produce a high-yielding and highly enantioselective system for iodolactonization (entries 5–6). It has been shown recently that N-iodoimides undergo conversion to the corresponding triiodide cations upon treatment with I2 and a protic acid,[12] and this provides a likely explanation for the synergistic effect of these reagents in the present system. However, increasing the I2 loading above that of the chiral catalyst (1) led to measurable decreases in enantioselectivity (entry 7). Variation of the identity of the N-iodoimide resulted in small but measurable changes in the enantioselectivity of the reaction, with N-iodo-4-fluorophthalimide derivative 5 proving optimal.[13] The sensitivity of the product ee to the structure of the imidate suggests a direct involvement of this counterion in the enantiodetermining step.

Table 1.

Optimization Studies for the enantioselective iodolactonization of 2a.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry[a] | I+ Source | I2 Additive (mol%) | Yield [b] | ee[c] |

| 1 | 4 | 0 | 0% | - |

| 2 | 5 | 0 | 3% | 50% |

| 3 | 6 | 0 | 25% | 30% |

| 4 | I2 | - | 12% | 66% |

| 5 | 4 | 15 | 95% | 92% |

| 6 | 5 | 15 | 98% | 94% |

| 7 | 5 | 30 | 85% | 88% |

Reactions performed on a 0.05 mmol scale.

Determined by 1H NMR analysis using 1, 3, 5-trimethoxybenzene as the internal standard.

Determined by HPLC analysis using commercial chiral columns.

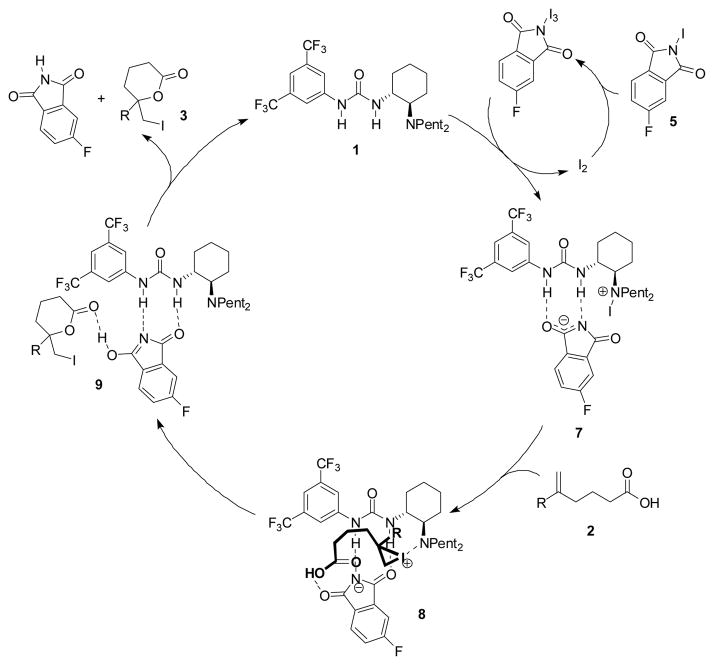

Low-temperature 1H NMR studies were performed in an effort to gain insight into the mechanism of the iodolactonization reaction. In the presence of N-iodo-4-fluorophthalimide 5 and catalytic iodine, catalyst 1 was found to undergo a rapid reaction to yield a compound with spectroscopic and reactivity properties consistent with the N-iodo complex 7 (Scheme 1).[14] Intermediate 7 can be quenched with aqueous sodium thiosulfate to regenerate the starting tertiary amine catalyst 1 as well as the corresponding secondary amine. The latter is presumably formed from 7 via elimination of HI and subsequent iminium hydrolysis.

Scheme 1.

Proposed catalytic cycle for the iodolactonization of 2.

A proposal for the mechanism of iodolactonization catalysis is outlined in Scheme 1. Iodonium ion formation from hexenoic acid 2 is presumably induced by N-iodo tertiary aminourea 7. Subsequent cyclization is proposed to take place as the rate- and enantiodeterminng step, based on the observation of differing reactivities, under otherwise identical conditions, of pentenoic, hexenoic, and heptenoic acid substrates to generate the corresponding 5-, 6-, and 7-membered lactone products (5>6≫7). Preliminary computational studies support the intermediacy of iodonium ion complex 8, which maintains a tertiary amino-iodonium ion interaction.[15] On the basis of this putative structure, we suggest that urea-bound phthalimide serves as the base to effect deprotonation of the carboxylic acid in the enantiodetermining cyclization event. An alternative mechanism in which deprotonation is induced by the tertiary amino group present in the catalyst is also plausible, although such a mechanism would require significant reorganization of complex 8.

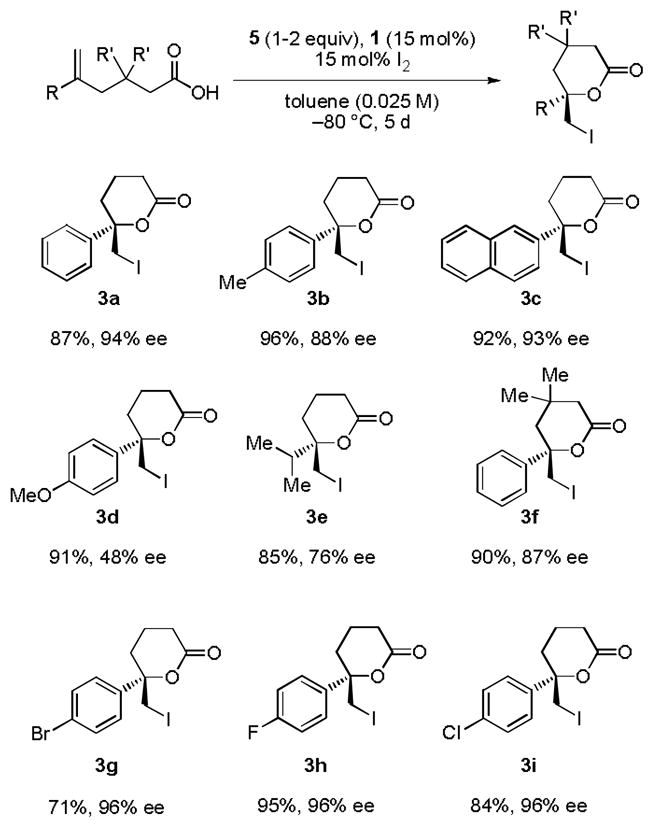

The optimized reaction conditions developed for the enantioselective iodolactonization of 2a were applied to a variety of other 5-substituted hexenoic acid derivatives (Figure 2). In the case of 5-arylhexenoic acids, a clear correlation emerged between the electronic properties of the arene and the observed ee, with electron-deficient derivatives undergoing more enantioselective cyclization. For these less reactive substrates (3g–3i), it was necessary to use 2 equivalents of the iodinating agent 5 to achieve useful conversions.

Figure 2.

Substrate scope in the catalytic iodolactonization reaction. Reactions were performed on a 0.2 mmol scale. Yields are of isolated product following purification by column chromatography. Ee’s were determined by HPLC or GC (3e) analysis on commercial chiral columns. See Supporting Information for full details.

To determine the absolute configuration of 3a, a radical deiodination was performed to provide the corresponding, known methyl lactone.[16] This assignment was confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis of the 4-bromo derivative 3g.[17]

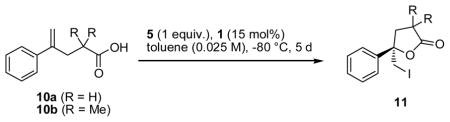

These reaction conditions proved ineffective with the corresponding pentenoic acid substrate 10a (Table 2, R = H), providing the iodolactonization product 11a in low enantiomeric excess (entry 1). However, enantioselectivities were improved dramatically by decreasing the loading of iodine additive, with best results obtained using 0.1 mol% of I2 (entry 3). The rate of racemic iodolactonization in the absence of 1 is not affected by the concentration of added I2, so it appears that the inverse relationship between ee and I2 loading may be due to competing pathways promoted by 1. In that context, it is interesting to note that the absolute configuration of 10a was found to be opposite to that of the hexenoic acid cyclization products 3. The basis for the striking differences in behaviour between the pentenoic and hexenoic acid substrates is not understood at this point but is the subject of current analysis.

Table 2.

Optimization studies for the enantioselective iodolactonization of pentenoic acid derivative 10a.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry[a] | Substrate | I2 Additive [mol%] | Yield [%][b] | Ee [%][c] |

| 1 | 10a | 15 | 86 | 31 |

| 2 | 10a | 1.0 | 95 | 76 |

| 3 | 10a | 0.1 | 45 | 90 |

| 4[d] | 10a | 0.1 | 82 | 90 |

| 5 | 10b | 0.1 | 98 | 0 |

Reactions performed on a 0.05 mmol scale.

Determined by 1H NMR analysis using 1, 3, 5-trimethoxybenzene as the internal standard.

Determined by HPLC analysis using commercial chiral columns.

Reaction performed using 2 equiv. 5.

Another potentially valuable mechanistic clue is provided by the fact that gem-dimethyl-substituted substrate 10b (R′ = Me) was found to undergo cyclization to give racemic product under the conditions optimized for 9a. Analogous gem-dimethyl substitution in the hexenoic acid case also led to significant decrease in ee (product 3f). In general, it was found that any factors expected to lead to more rapid cyclization of the iodonium ion intermediate (8, Scheme 1) led to diminished enantioselectivities. If the rates of the two steps (iodonium formation, 7 → 8 and cyclization, 8 → 9, Scheme 1) are finely balanced, it is possible that acceleration of the second step change the identity of the rate- and ee-determining step to formation of the iodonium ion. Poor face selectivity in the iodination of the alkene would then be responsible for the decreases in enantioselectivity.

In conclusion, under appropriate conditions, tertiary aminourea derivative 1 induces enantioselective iodolactonization reactions to afford 5- and 6-membered iodolactones with high levels of enantioselectivity. Studies to elucidate the mechanism and origin of enantioinduction in this process are underway.

Experimental Section

To a stirred solution of the 5-hexenoic acid (0.2 mmol) and catalyst 1 (15.4 mg, 0.03 mmol) in toluene (8 mL) at −80 °C was added N-iodo-4-fluorophthalimide (58 mg, 0.2 mmol) followed by iodine (7.6 mg, 0.03 mmol) as solids under a nitrogen atmosphere. After stirring at this temperature for 5 d, the reaction mixture was quenched at −80 °C by addition of 10% aqueous sodium thiosulfate solution (4 mL) and partitioned between 1 M sodium hydroxide solution (30 mL) and CH2Cl2 (30 ml). The organic layer was separated, further washed with 1 M sodium hydroxide solution (30 mL), dried (MgSO4), and concentrated in vacuo. Purification by flash column chromatography on silica gel (5–40% ethyl acetate in hexanes) afforded the iodolactone products.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (GM-43214) and by postdoctoral fellowships to G.E.V. from the Fulbright Commision and the Royal Society for the Exhibition of 1851. We acknowledge Mr. Mitchell Denti for experimental assistance and Dr. Eugene Kwan for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author

References

- 1.a) Dowle MD, Davies DI. Chem Soc Rev. 1979;8:171–197. [Google Scholar]; b) Ranganathan S, Muraleedharan KM, Vaish NK, Jayaraman N. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:5273–5308. [Google Scholar]; c) French AN, Bissmire S, Wirth T. Chem Soc Rev. 2004;33:354–362. doi: 10.1039/b310389g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Laya MS, Banerjee AK, CEV Curr Org Chem. 2009;13:720–730. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Only two reports of moderately selective enantioselective iodolactonization have appeared to date: Wang M, Gao LX, Mai WP, Xia AX, Wang F, Zhang SB. J Org Chem. 2004;69:2874–2876. doi: 10.1021/jo035719e.Ning ZL, Jin RH, Ding JY, Gao LX. Synlett. 2009:2291–2294.

- 3.For examples of reagent-controlled enantioselective iodolactonization see: Kitagawa O, Hanano T, Tanabe K, Shiro M, Taguchi T. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1992:1005–1007.Grossman RB, Trupp RJ. Can J Chem. 1998;76:1233–1237.Haas J, Piguel S, Wirth T. Org Lett. 2002;4:297–300. doi: 10.1021/ol0171113.Haas J, Bissmire S, Wirth T. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:5777–5785. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500507.Garnier JM, Robin S, Rousseau G. Eur J Org Chem. 2007:3281–3291.

- 4.For successful examples of other types of enantioselective halocyclization reactions see: Kang SH, Lee SB, Park CM. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:15748–15749. doi: 10.1021/ja0369921.Sakakura A, Ukai A, Ishihara K. Nature. 2007;445:900–903. doi: 10.1038/nature05553.Whitehead DC, Yousefi R, Jaganathan A, Borhan B. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3298–3300. doi: 10.1021/ja100502f.Zhang W, Zheng SQ, Liu N, Werness JB, Guzei IA, Tang WP. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3664–3665. doi: 10.1021/ja100173w.

- 5.a) Doyle AG, Jacobsen EN. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5713–5743. doi: 10.1021/cr068373r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang ZG, Schreiner PR. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:1187–1198. doi: 10.1039/b801793j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Taylor MS, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10558–10559. doi: 10.1021/ja046259p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Raheem IT, Thiara PS, Peterson EA, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13404–13405. doi: 10.1021/ja076179w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Pan SC, List B. Org Lett. 2007;9:1149–1151. doi: 10.1021/ol0702674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Peterson EA, Jacobsen EN. Angew Chem. 2009;134:6446–6449. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:6328–6331. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Knowles RR, Lin S, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5030–5032. doi: 10.1021/ja101256v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Klausen RS, Jacobsen EN. Org Lett. 2009;11:887–890. doi: 10.1021/ol802887h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Xu H, Zuend SJ, Woll MG, Tao Y, Jacobsen EN. Science. 2010;327:986–990. doi: 10.1126/science.1182826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De CK, Klauber EG, Seidel D. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:17060–17061. doi: 10.1021/ja9079435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mita T, Jacobsen EN. Synlett. 2009:1680–1684. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1217344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reisman SE, Doyle AG, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7198–7199. doi: 10.1021/ja801514m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Details of the catalyst screen are provided in the Supporting Information.

- 12.Chaikovskii VK, Funk AA, Filiminov VD, Petrenko TV, Kets TS. Russ J Org Chem. 2008;44:935–938. [Google Scholar]

- 13.For full details of the optimization of the N-iodoimide see the Supporting Information.

- 14.Complex 7 displays changes in the 1H NMR spectrum comparable to those observed upon protonation of 1 with strong mineral acids. See Supporting Information for further details.

- 15.DFT calculations were performed using the hybrid GGA functional B3PW91/6-31g(d) with a modified SDD pseudopotential, as described in: Haas J, Bissmire S, Wirth T. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:5777–5785. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500507.

- 16.Date M, Tamai Y, Hattori T, Takayama H, Kamikubo Y, Miyano S. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1–2001. 2001:645–653.

- 17.CCDC 781487 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.