Abstract

Metal-dioxygen adducts are key intermediates detected in the catalytic cycles of dioxygen activation by metalloenzymes and biomimetic compounds. In this study, mononuclear cobalt(III)- peroxo complexes bearing tetraazamacrocyclic ligands, [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+ and [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+, were synthesized by reacting [Co(12-TMC)(CH3CN)]2+ and [Co(13-TMC)(CH3CN)]2+, respectively, with H2O2 in the presence of triethylamine. The mononuclear cobalt(III)-peroxo intermediates were isolated and characterized by various spectroscopic techniques and X-ray crystallography, and the structural and spectroscopic characterization demonstrated unambiguously that the peroxo ligand is bound in a side-on η2 fashion. The O-O bond stretching frequency of [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+ and [Co(13- TMC)(O2)]+ was determined to be 902 cm−1 by resonance Raman spectroscopy. The structural properties of the CoO2 core in both complexes are nearly identical; the O-O bond distances of [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+ and [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ were 1.4389(17) Å and 1.438(6) Å, respectively. The cobalt(III)-peroxo complexes showed reactivities in the oxidation of aldehydes and O2-transfer reactions. In the aldehyde oxidation reactions, the nucleophilic reactivity of the cobalt-peroxo complexes was significantly dependent on the ring size of the macrocyclic ligands, with the reactivity of [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ > [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+. In the O2-transfer reactions, the cobalt(III)-peroxo complexes transferred the bound peroxo group to a manganese(II) complex, affording the corresponding cobalt(II) and manganese(III)- peroxo complexes. The reactivity of the cobalt-peroxo complexes in O2-transfer was also significantly dependent on the ring size of tetraazamacrocycles, and the reactivity order in the O2-transfer reactions was the same as that observed in the aldehyde oxidation reactions.

1. Introduction

Mononuclear metal-dioxygen adducts, M-O2, are generated as key intermediates in the catalytic cycles of dioxygen activation by metalloenzymes, including heme and nonheme iron and copper enzymes.1 As chemical models of the enzymes, a number of metal-O2 complexes have been synthesized and characterized with various spectroscopic techniques and X-ray crystallography, and their reactivities have been extensively investigated in electrophilic and nucleophilic oxidation reactions.2–6 For example, heme and nonheme iron(III)-O2 complexes were synthesized as chemical models of Cytochrome P450 aromatases and Rieske dioxygenases, respectively, and have shown reactivities in nucleophilic reactions such as aldehyde deformylation.4 Mononuclear Cu-O2 complexes have been synthesized as chemical models of copper-containing enzymes, such as peptidylglycine α-hydroxylating monooxygenase (PHM) and dopamine β-monooxygenase (DβM),5 and their reactivities have been investigated in electrophilic reactions.6

The chemistry of cobalt-O2 complexes bearing salen, porphyrin, and tetraazamacrocycle ligands has been extensively investigated as chemical models of dioxygen-carrying proteins, such as hemoglobin and myoglobin,7 and as active oxidants in the oxidation of organic substrates.8 As a result, structural and spectroscopic characterization of the cobalt-O2 complexes has been well established in 1970s. The structural analysis of the cobalt-O2 complexes by X-ray crystallography revealed that the O2 group in the intermediates has superoxo character with an end-on (η1) binding mode, Co(III)-(O2−).7c,9 Mononuclear cobalt-O2 complexes with a side-on (η2) cobalt(III)-peroxo moiety, Co(III)-(O22−), have also been reported,10 such as [Co(2=phos)2(O2)]+ (2=phos = cis-[(C6H5)2PCH=CHP(C6H5)2]),10a Co(Tp′)(O2) (Tp′ = hydridotris(3-tert-butyl-5-methylpyrazolyl)borate),10b [Co(tmen)2(O2)]+ (tmen = tetramethylenthylenediamine),10c [Co(TIMENxyl)(O2)]+ (TIMENxyl = tris[2-(3-xylenylimidazol-2- ylidene)ethyl]amine).10d The oxidation of organic substrates, such as phenols and olefins, by Co(II) Schiff-base complexes has also been extensively investigated under aerobic, catalytic conditions.8,11 In the oxidation reactions, end-on cobalt(III)-superoxo complexes, Co(III)-(O2−), have been proposed as active oxidants that abstract hydrogen atom (H-atom) from weak O-H or C-H bonds of substrates.11

Very recently, we reported the crystal structure and spectroscopic properties of a mononuclear side-on nickel(III)-peroxo complex bearing a macrocyclic ligand, [Ni(12-TMC)(O2)]+ (12-TMC = 1,4,7,10-tetramethyl-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane), and an O2-transfer reaction of the intermediate (i.e., intermolecular O2-transfer reaction).12a In that study, we demonstrated that the geometric and electronic structures and reactivities of the Ni-O2 complexes are markedly affected by supporting ligands,12 as shown in the chemistry of mononuclear Cu-O2 complexes.13 Crystal structures of other metal-O2 complexes bearing tetraazamacrocyclic ligands, such as [Mn(14-TMC)(O2)]+ (14-TMC = 1,4,8,11-tetramethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane), [Mn(13-TMC)(O2)]+ (13-TMC = 1,4,7,10- tetramethyl-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclotridecane), and [Cr(14-TMC)(O2)(Cl)]+, have also been reported along with their reactivities in aldehyde deformation and C-H bond activation reactions.14,15 Herein we report the synthesis, structural and spectroscopic characterization, and reactivities of side-on cobalt(III)- peroxo complexes bearing tetraazamacrocyclic ligands, [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+ (2) and [Co(13- TMC)(O2)]+ (4).16 We have also shown that reactivities of metal-peroxo intermediates in O2-transfer and oxidative nucleophilic reactions are markedly affected by the central metal ions and the ring size of the macrocyclic ligands.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1 Synthesis of Co-O2 Complexes

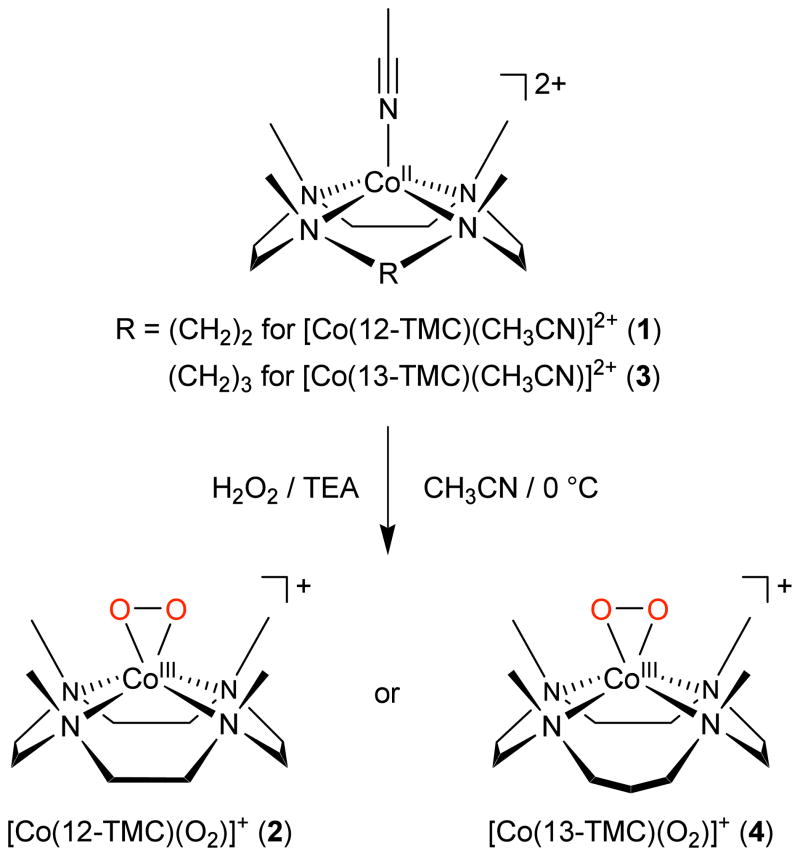

Synthetic procedures for cobalt(III)-peroxo complexes are depicted in Scheme 1. The starting materials, [Co(12-TMC)(CH3CN)]2+ (1) and [Co(13-TMC)(CH3CN)]2+ (3), were prepared by reacting Co(ClO4)2·6H2O with the corresponding 12-TMC and 13-TMC ligands, respectively. The cobalt(III)- peroxo complexes were then synthesized as follows: Addition of 5 equiv H2O2 to a reaction solution containing 1 and 2 equiv triethylamine (TEA) in CH3CN at 0 °C afforded a purple intermediate, [Co(12- TMC)(O2)]+ (2). 2 was then isolated at a temperature below −20 °C. Similarly, [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ (4) was obtained by reacting 3 with 5 equiv H2O2 in the presence of 2 equiv TEA in CH3CN at 0 °C and isolated at a temperature below −40 °C. The intermediates, 2 and 4, persisted for several days at 0 °C. The greater thermal stability of 2 and 4 allowed us to use isolated cobalt-peroxo intermediates in spectroscopic and reactivity studies.

Scheme 1.

2.2 Structural and Spectroscopic Characterization

2.2.1 X-ray Crystallography

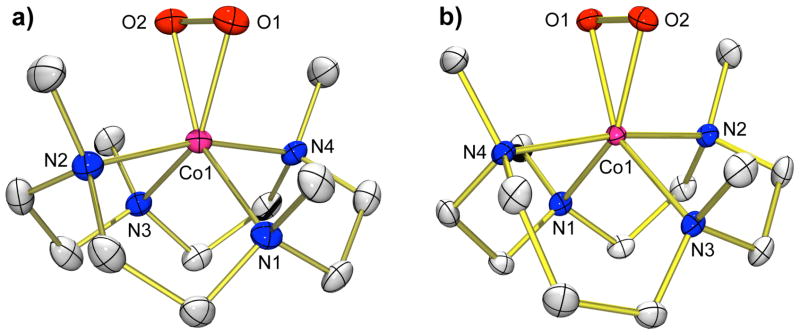

Complexes 1 – 4 were successfully characterized by X-ray diffraction analyses. The molecular structures of the complex cations of 1–4 are shown in Figure 1 and Supporting Information (SI), Figure S1, and selected bond distances and angles are listed in Table 1 and Table S1 in Supporting Information (SI). Complex 1 has a five-coordinate cobalt(II) ion with four nitrogens of the macrocyclic 12-TMC ligand in equatorial positions and one nitrogen of CH3CN in an axial position (SI, Figure S1a), as found in a nickel(II) analog, [Ni(12-TMC)(CH3CN)]2+.12a Complex 3 has a coordination geometry similar to 1 (SI, Figure S1b). The average Co-Nequatorial bond distance of 3 (2.068 Å) is longer than that of 1 (1.988 Å), but the Co-Naxial bond distance of 3 (2.015 Å) is slightly shorter than that of 1 (2.036 Å).

Figure 1.

X-ray crystal structures of (a) [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+ (2) and (b) [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ (4) with thermal ellipsoids drawn at the 30 % probability level. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

Table 1.

Selected Bond Distances (Å) and Angles (°) for 2-(BPh4)•CH3CN and 4-(ClO4)•CH3CN

| 2-(BPh4)•CH3CN | 4-(ClO4)•CH3CN | |

|---|---|---|

| Co1-N1 | 1.9991(17) | 1.995(3) |

| Co1-N2 | 2.0155(18) | 2.017(3) |

| Co1-N3 | 1.9969(16) | 2.078(3) |

| Co1-N4 | 2.0249(18) | 2.037(3) |

| Co1-O1 | 1.8737(12) | 1.846(2) |

| Co1-O2 | 1.8575(13) | 1.864(3) |

| O1-O2 | 1.4389(17) | 1.438(4) |

| N1-Co1-N2 | 85.93(8) | 85.67(12) |

| N1-Co1-N3 | 110.88(7) | 108.84(13) |

| N1-Co1-N4 | 85.96(8) | 84.77(13) |

| N2-Co1-N3 | 86.28(7) | 86.05(12) |

| N2-Co1-N4 | 165.09(7) | 170.10(12) |

| N3-Co1-N4 | 84.94(8) | 94.58(12) |

| O1-Co1-O2 | 45.36(5) | 45.61(12) |

| Co1-O1-O2 | 66.72(7) | 67.85(14) |

| Co1-O2-O1 | 67.91(8) | 66.54(14) |

The X-ray structures of 2 and 4 revealed a mononuclear side-on cobalt-O2 complex in a distorted octahedral geometry arising from the triangular CoO2 moiety with a small bite angle of 45.36(5)° for 2 and 45.16(12)° for 4 (Figure 1). The O-O bond lengths of 1.4389(17) Å for 2 and 1.438(4) Å for 4, which are comparable to those in [Co(tmen)2(O2)]+ (1.457 Å) and [Co(TIMENxyl)(O2)]+ (1.429 Å),10c,10d are indicative of peroxo character of the O2 group,17 as assigned by resonance Raman data (vide infra). The average Co-O bond distance of 4 (1.856 Å) is slightly shorter than that of 2 (1.866 Å). Further, the O-O bond distances of 2 and 4 are longer than that of [Ni(12-TMC)(O2)]+ (1.386 Å), whereas the average Co-O bond distances of 2 (1.866 Å) and 4 (1.856 Å) are shorter than the average Ni-O bond distance of [Ni(12-TMC)(O2)]+ (1.889 Å).12a Finally, all four N-methyl groups of the 12-TMC and 13- TMC ligands point toward the peroxo group, as observed in other metal(III)-peroxo complexes bearing tetraazamacrocyclic ligands, such as [Ni(12-TMC)(O2)]+,12a [Mn(14-TMC)(O2)]+,14a and [Mn(13- TMC)(O2)]+.14b

2.2.2 Co K-edge X-Ray Absorption and EXAFS

The normalized Co K-edge x-ray absorption data for 2 and 4 are presented in SI, Figure S2. The inset shows the pre-edge transition, which is the result of an electric dipole forbidden, quadrupole allowed 1s→3d transition. The pre-edge energy position dominantly reflects the ligand-field strength at the absorbing metal center. The pre-edge transition for both 2 and 4 occurs at ~7710.1 eV. The intense step-function like feature to higher energy (~7712 to 7728 eV) is the rising-edge, which occurs due to dipole-allowed 1s→4p+continuum transitions. The rising edge inflection energy reflects the charge at the absorbing metal center. This inflection point occurs at ~7721.0 eV for both 2 and 4, an energy typical for Co(III) systems.18 The similarity in the pre-edge energy and the rising edge inflection points indicate that 2 and 4 are both Co(III)-O22− complexes.

Co K-edge extended x-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) data were collected on 2 and 4 to evaluate the geometric structure of the O2 bound adducts of 1 and 3 in solution and compare to the crystal structure. The k3 weighted Co K-edge EXAFS data (SI, Figure S3, inset), non-phase shift corrected Fourier transform (k=2–14 Å−1) and the corresponding FEFF fits for 2 and for 4 are shown in SI, Figure S3a and S3b, respectively. Numerical fits are presented in Table S2. FEFF fits to the data for 2 are consistent with 2 Co-O interactions at 1.85 Å and 4 Co-N interactions at 1.99 Å. The second shell for 2 was fit with 8 Co-C single-scattering and 24 Co-C-N multiple-scattering components from the 12- TMC ligand backbone carbons. FEFF fits to the data for 4 resulted in structural parameters similar to those for 2. The first shell was fit with 2 Co-O contribution at 1.85 Å and 4 Co-N contributions at 2.0 Å. The second shell was fit with 8 Co-C single-scattering and 24 Co-C-N multiple-scattering components from the 13-TMC ligand backbone carbons. The additional carbon atom in the 13-TMC ring is at a longer distance than the rest of the ring carbon atoms and does not contribute to the second shell single and multiple scattering. The similarity in the EXAFS fit parameters for 2 and 4 and the resulting structural parameters demonstrate that the solution structure of both 2 and 4 are in agreement with the crystal structure and both the species are mononuclear species with O2 bound in a side-on ( η2) fashion to the Co center.

2.2.3 Spectroscopic Characterization

2.2.3.1 [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+ (2)

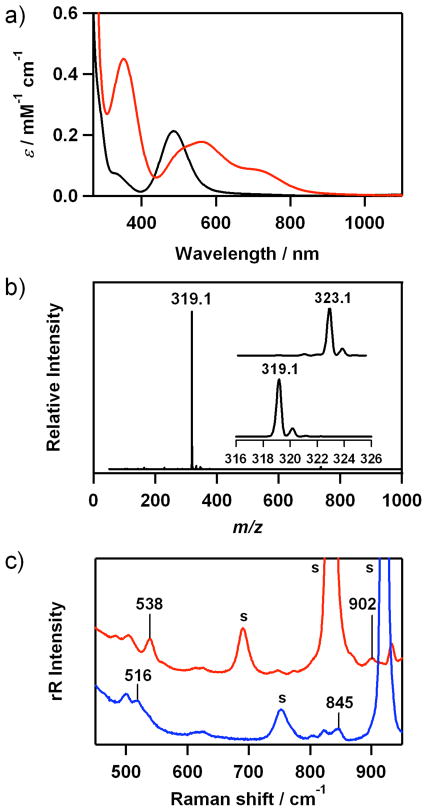

The electronic spectrum of 2 shows distinct absorption bands at 350 (ε = 450 M−1 cm−1) and 560 nm (ε = 180 M−1 cm−1), and shoulders at ~500 (ε = 150 M−1 cm−1) and ~710 nm (ε = 90 M−1 cm−1) (Figure 2a). The electrospray ionization mass spectrum (ESI-MS) of 2 exhibits a prominent signal at m/z 319.1 (Figure 2b), whose mass and isotope distribution pattern correspond to [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+ (calculated m/z 319.2) (Figure 2b, inset). When the reaction was carried out with isotopically labeled H2 18O2, a mass peak corresponding to [Co(12-TMC)(18O2)]+ appeared at m/z of 323.1 (calculated m/z 323.2) (Figure 2b, inset). The observation of the 4-mass unit upshift upon the substitution of 16O with 18O indicates that 2 contains an O2 unit.

Figure 2.

a) UV-vis spectra of [Co(12-TMC)(CH3CN)]2+ (1) (black) and [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+ (2) (red) in CH3CN at 0 °C. b) ESI-MS of 2 in CH3CN at 0 °C. Insets show the observed isotope distribution patterns for [Co(12-TMC)(16O2)]+ at m/z 319.1 and [Co(12-TMC)(18O2)]+ at m/z 323.1. c) Resonance Raman spectra of 2 (32 mM) obtained upon excitation at 442 nm at 0 °C; in situ-generated 2-16O2 (red line) and 2-18O2 (blue line) were recorded in CD3CN and CH3CN, respectively, owing to significant overlap with intense solvent bands. The peaks marked with “s” are ascribed to acetonitrile and d3- acetonitrile solvents. See SI, Figure S4 for resonance Raman spectra of 2 recorded under various conditions.

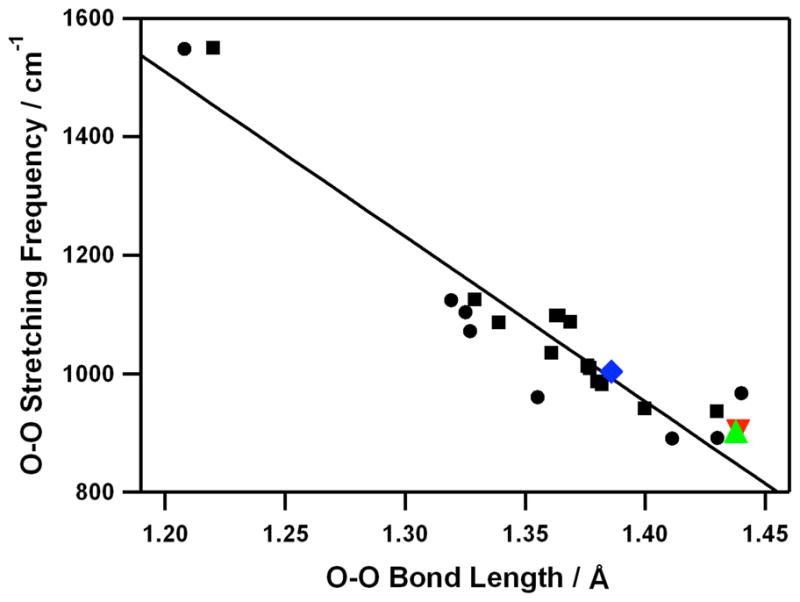

The resonance Raman spectrum of 2 obtained upon 442-nm excitation in CD3CN at 0 °C exhibits two isotopically sensitive bands at 902 and 538 cm−1 that shift to 845 and 516 cm−1, respectively, in samples of 2 prepared with H2 18O2 in CH3CN (Figure 2c and SI, Figure S4). The higher energy feature (902 cm−1) with 16Δ-18Δ value of 57 cm−1 (16Δ-18Δ (calcd) = 51 cm−1) is ascribed to the O-O stretching vibration of the peroxo ligand, and the lower-energy feature (538 cm−1) is assigned to the Co-O stretching vibration (16Δ-18Δ = 22 cm−1; 16Δ-18Δ (calcd) = 24 cm−1).19 In addition, we have observed a good correlation between the O-O stretching frequency and the O-O bond length in 2 (Figure 3).17

Figure 3.

Plot of the O-O stretching frequency (cm−1) vs the O-O bond distance (Å) for side-on metal-O2 complexes. Circles represent experimental data points and squares represent theoretical ones taken from ref. 17. The solid line represents a least-squares linear fit of the experimental and theoretical data. Data points for [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+ (2) ( ), [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ (4) (

), [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ (4) ( ), and [Ni(12-TMC)(O2)]+ (

), and [Ni(12-TMC)(O2)]+ ( ) are included in the diagram.

) are included in the diagram.

The X-band EPR spectrum of the starting complex, [Co(12-TMC)(CH3CN)]2+ (1), at 4.3 K contains features at g⊥ = 2.31 and g|| ≈ 2.07, which are typical for a low-spin (S = 1/2) cobalt(II) complex (SI, Figure S5). The EPR spectrum of 2 is silent at 4.3 K (SI, Figure S5), suggesting that 2 is either a low-spin (S = 0) or an integer spin (S = 1, 2) cobalt(III) d6 species. The 1H NMR and COSY spectra of 2 recorded in d3-acetonitrile at −40 °C show sharp features in the 0 – 10 ppm region (SI, Figure S6), indicating that 2 is, in fact, a low-spin (S = 0) cobalt(III) d6 species at −40 °C.

2.2.3.2 [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ (4)

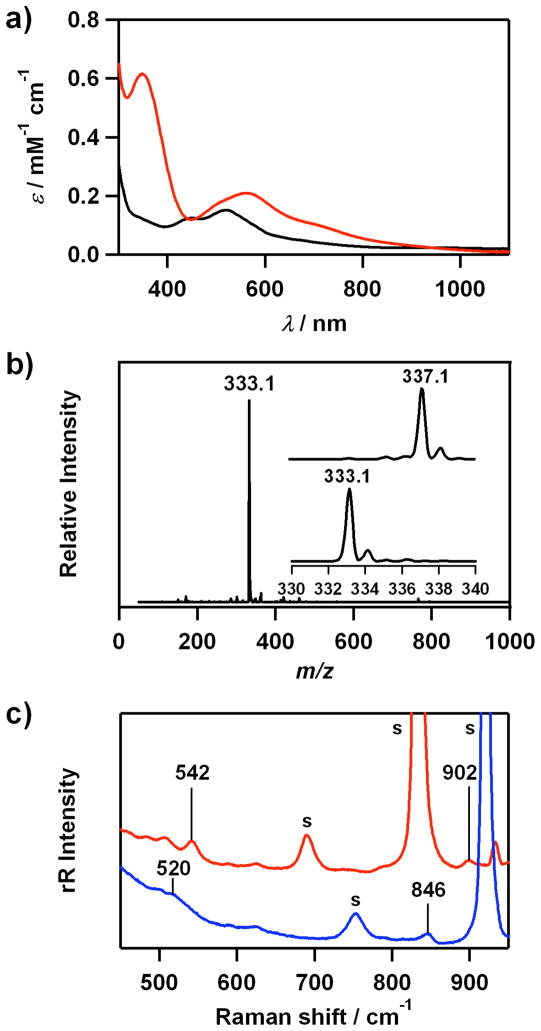

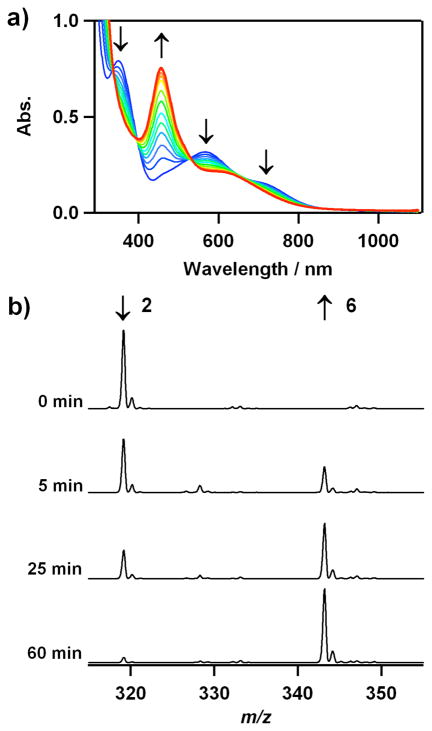

Spectroscopic properties of 4 are similar to those of 2. The electronic spectrum of 4 shows distinct absorption bands at 348 (ε = 620 M−1 cm−1) and 562 nm (ε = 210 M−1 cm−1), and shoulders at ~500 (ε = 170 M−1 cm−1) and ~710 nm (ε = 100 M−1 cm−1) (Figure 4a). The ESI-MS of 4 exhibits a prominent mass signal at m/z 333.1 (Figure 4b), whose mass and isotope distribution pattern correspond to [Co(13- TMC)(O2)]+ (calculated m/z 333.2), with the expected 4-mass unit upshift upon the substitution of 16O by 18O (Figure 4b, inset).

Figure 4.

a) UV-vis spectra of [Co(13-TMC)(CH3CN)]2+ (3) (black) and [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ (4) (red) in CH3CN at 0 °C. b) ESI-MS of 4 in CH3CN at 0 °C. Insets show the observed isotope distribution patterns for [Co(13-TMC)(16O2)]+ at m/z 333.1 and [Co(13-TMC)(18O2)]+ at m/z 337.1. c) Resonance Raman spectra of 4 (32 mM) obtained upon excitation at 442 nm at 0 °C; in situ-generated 4-16O2 (red line) and 4-18O2 (blue line) were recorded in CD3CN and CH3CN, respectively, owing to significant overlap with intense solvent bands. The peaks marked with “s” are ascribed to acetonitrile and d3- acetonitrile solvents. See SI, Figure S7 for resonance Raman spectra of 4 recorded under various conditions.

The resonance Raman spectrum of 4, obtained upon 442-nm excitation in CD3CN at 0 °C, exhibits two isotopically sensitive bands at 902 and 542 cm−1 that shift to 846 and 520 cm−1, respectively, in samples of 4 prepared with H2 18O2 in CH3CN (Figure 4c and SI, Figure S7). The higher energy feature (902 cm−1) with 16Δ-18Δ value of 56 cm−1 (16Δ-18Δ (calcd) = 51 cm−1) is ascribed to the O-O stretching vibration of the peroxo ligand, and the lower energy feature (542 cm−1) is assigned to the Co-O stretching vibration (16Δ-18Δ = 22 cm−1; 16Δ-18Δ (calcd) = 24 cm−1).19 Like 2, the relatively low O-O frequency is consistent with the O-O bond distance in 4, and we have observed a good correlation between the O-O stretching frequency and the O-O bond length (Figure 3).17

The X-band EPR spectrum of [Co(13-TMC)(CH3CN)]2+ (3) at 4.3 K contains features at g⊥ = 2.31 and g|| ≈ 2.07, which are typical for a low-spin (S = 1/2) cobalt(II) species (SI, Figure S8). Complex 4 is EPR silent (X-band, 4.3 K) and exhibits a sharp 1H NMR spectrum in the 0 – 10 ppm region (data not shown), indicating that 4 is a low-spin (S = 0) cobalt(III) d6 species. Taken together, the spectroscopic data with the structural characterization demonstrate that 2 and 4 are low-spin (S = 0) cobalt(III)-peroxo complexes with the peroxo ligand bound in a side-on η2 fashion, [CoIII(12-TMC)(O2)]+ and [CoIII(13- TMC)(O2)]+, respectively.

2.2.4 DFT Calculations

Spin-unrestricted broken symmetry density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed on the cationic moieties of [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+ and [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+, obtained from the crystal structures of 2 and 4. The relevant bond distances are presented in SI, Table S3. The calculated Co-O, O-O, and average Co-N distances of 1.88 Å, 1.44 Å, and ~2.03 Å, respectively, are in close agreement with the data obtained from X-ray crystallography and Co K-edge EXAFS results for 2. The DFT optimized structure of 4 is qualitatively similar to that of 2, although there is a larger spread in the Co-N distances (see SI, Table S3). This is consistent with the slight decrease in the first shell intensity of the Fourier Transform in 4 relative to 2 (see SI, Figure S3 for comparison). The average Co-O and O-O distances are 1.90 Å and 1.42 Å, which are in reasonable agreement with the experimental data. The calculated geometric and electronic structures for 2 and 4 are consistent with a low-spin [Co(III)-O22−]+ ground state as observed from the experimental data.

2.3 Reactivities of Co-O2 Complexes

2.3.1 Nucleophilic Reactions

The reactivity of the cobalt(III)-peroxo complexes was investigated in electrophilic and nucleophilic reactions. First, the electrophilic character of 2 and 4 was tested in the oxidation of thioanisole and cyclohexene. Upon addition of substrates to a solution of 2 and 4 in CH3CN at 25 °C, the intermediate remained intact without showing any absorption spectral change, and product analysis of the reaction solutions revealed that no oxygenated products were formed. These results demonstrate that the Co(III)-peroxo complexes are not capable of conducting electrophilic oxidation with the substrates under the reaction conditions.

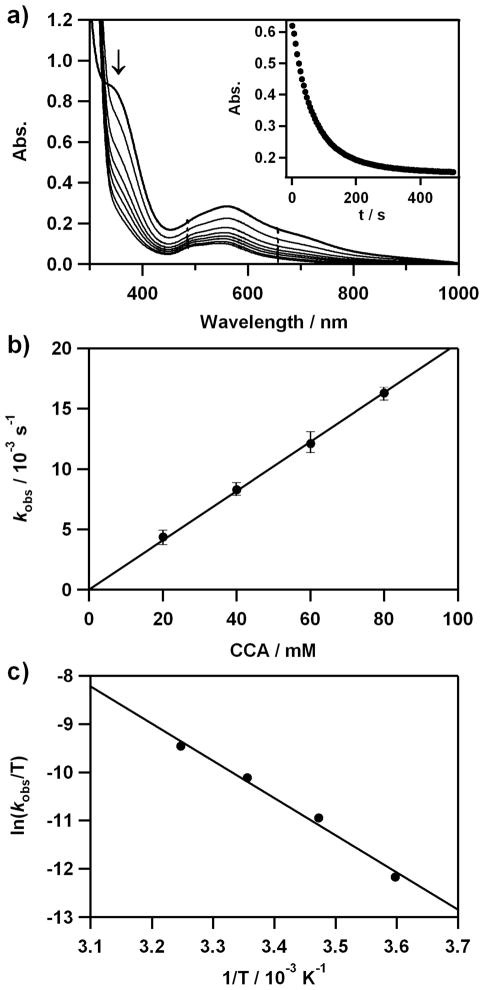

The nucleophilic character of 4 was then investigated in aldehyde deformylation, with precedents that metal(III)-peroxo complexes with heme and nonheme ligands react with aldehydes to give corresponding deformylated products.4,12a,14 Upon reacting 4 with cyclohexanecarboxaldehyde (CCA) in CH3CN at 25 °C, the characteristic UV-vis absorption bands of 4 disappeared with a pseudo-first-order decay (Figure 5a), and product analysis of the reaction solution revealed that cyclohexene (80 ± 10%) was produced in the oxidation of CCA.12a,14,20 The pseudo-first-order fitting of the kinetic data, monitored at 380 nm, yielded the kobs value of 1.6 × 10−2 s−1 (Figure 5a). The pseudo-first-order rate constants increased proportionally with the concentration of CCA, giving a second-order rate constant (k2) of 2.0 × 10−1 M−1 s−1 (Figure 5b). Similar results were obtained in the reactions of 2- phenylpropionaldehyde (2-PPA) but with a slower rate (k2 = 1.5 × 10–2 M−1 s−1 at 25 °C) (SI, Figure S9). The product analysis of the resulting solution revealed the formation of acetophenone (90 ± 10%). Activation parameters for the aldehyde deformylation of 4 between 278 and 308 K were determined to be ΔH‡ = 64 kJ mol−1 and ΔS‡ = –67 J mol−1 K−1 for CCA (Figure 5c) and ΔH‡ = 62 kJ mol−1 and ΔS‡ = – 77 J mol−1 K−1 for 2-PPA (SI, Figure S9). Further, the reactivity of 4 was investigated with parasubstituted benzaldehydes, para-X-Ph-CHO (X = OMe, Me, F, H), to investigate the effect of parasubstitutents on the benzaldehyde oxidation process by Co(III)-peroxo species. Hammett plot of the pseudo-first-order rate constants versus σp + gave a ρ value of 1.7 (Figure S10), which is consistent with the nucleophilic character of the Co-peroxo unit in the oxidation of aldehydes.12a Finally, it is of interest to note that the reactivity of 2 is much lower than that of 4 in nucleophilic reactions; therefore, we were not able to obtain kinetic data for 2 under the reaction conditions. The latter result implies that the nucleophilic character of the peroxo ligand is influenced markedly by the ring size of tetraazamacrocyclic ligands (i.e., [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ > [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+).

Figure 5.

Reactions of [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ (4) with cyclohexanecarboxaldehyde (CCA) in acetonitrile at 25 °C. a) UV-vis spectral changes of 4 (2 mM) upon addition of 40 equiv of CCA. Inset shows the time course of the absorbance at 380 nm. b) Plot of kobs against CCA concentration to determine a second-order rate constant. c) Plot of first-order rate constants against 1/T to determine activation parameters for the reaction of 4 (2 mM) and 30 equiv of CCA.

2.3.2 O2-Transfer Reactions

It has been shown that a mononuclear Ni(III)-peroxo complex, [Ni(12-TMC)(O2)]+, is capable of transferring the peroxo group to a manganese(II) complex, thus affording the corresponding nickel(II) and manganese(III)-peroxo complexes (eq. 1).12a We therefore attempted the intermolecular dioxygen

| (1) |

transfer from the cobalt-peroxo complexes, 2 and 4, to the [Mn(14-TMC)]2+ complex. Interestingly, addition of [Mn(14-TMC)]2+ to a solution of 2 in CH3CN at 25 °C resulted in the disappearance of the band (λmax = 350 nm) corresponding to 2 with the concomitant growth of an absorption band (λmax = 453 nm) corresponding to [Mn(14-TMC)(O2)]+ (5) (Figure 6a).14a The intermolecular O2-transfer from 2 to [Mn(14-TMC)]2+ was further confirmed by taking ESI-MS of the reaction solution at different times, where the mass peak at m/z 319.1 corresponding to 2 disappeared with a concomitant appearance of the mass peak at m/z 343.2 corresponding to 5 (Figure 6b). Further, when the O2-transfer reaction was carried out under an 18O2 atmosphere, the product 5 did not contain the isotopically labeled 18O2 group, demonstrating that molecular oxygen was not involved in the O2-transfer reaction. Furthermore, we found that the reverse reaction, which is the peroxo ligand transfer from 5 to 2 or 4, does not occur.

Figure 6.

Spectral evidence for O2-transfer from [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+ (2) to [Mn(14-TMC)]2+. a) UV-vis spectral changes showing the disappearance of 2 (blue line) and the appearance of [Mn(14-TMC)(O2)]+ (5) (red line) upon addition of [Mn(14-TMC)]2+ (2 mM) to a solution of 2 (2 mM) in CH3CN at 25 °C. b) ESI-MS changes of 2 at m/z 319.1 and 5 at m/z 343.2 in the reaction of 2 (2 mM) and [Mn(14- TMC)]2+ (2 mM) in CH3CN at 25 °C.

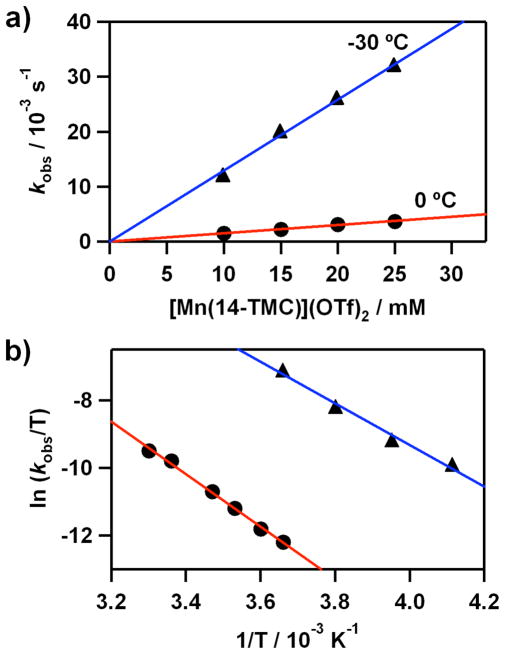

Kinetic studies of the O2-transfer from 2 to [Mn(14-TMC)]2+ were carried out in acetone at 0 °C (SI, Figure S11a). Addition of 15 equiv of [Mn(14-TMC)]2+ to the solution of 2 yielded kobs value of 2.2 × 10−3 s−1 under pseudo-first-order conditions. The rate constant increased proportionally with the concentration of [Mn(14-TMC)]2+, giving a second-order rate constant of k2 = 1.5 × 10−1 M−1 s−1 at 0 °C (Figure 7a, red line). The reaction rate was dependent on temperature, and a linear Eyring plot was obtained between 0 and 25 °C to give the activation parameters of ΔH‡ = 65 kJ mol−1 and ΔS‡ = − 63 J mol−1 K−1 (Figure 7b, red line). The dependence of the rate constants on the concentration of reactants and the significant negative entropy value suggest that the O2-transfer reaction proceeds via a bimolecular mechanism in which the formation of an undetected [(12-TMC)Co− O2− Mn(14-TMC)]3+ intermediate is the rate-determining step (eq. 2). It is of interest to note that the O2-transfer from 2 to

Figure 7.

Kinetic studies of O2-transfer reactions from [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+ (2) and [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ (4) to [Mn(14-TMC)]2+. a) Plots of kobs against the concentration of [Mn(14-TMC)]2+ to determine second-order rate constants for the reactions of 2 at 0 °C (red line with •) and 4 at −30 °C (blue line with ▲) in acetone. b) Plots of first-order rate constants against 1/T to determine activation parameters for the reactions of [Mn(14-TMC)]2+ (10 mM) with 2 (1 mM, red line with •) and 4 (1 mM, blue line with ▲) in acetone.

| (2) |

[Mn(14-TMC)]2+ is ~1100 times slower than that from [NiIII(12-TMC)(O2)]+ to [Mn(14-TMC)]2+ (e.g., k2 = 1.9 × 10−4 M−1 s−1 for the reaction of 2 and k2 = 0.2 M−1 s−1 for the reaction of [NiIII(12-TMC)(O2)]+ at −50 °C),21 indicating that the peroxo group of 2 is much less reactive than that of [NiIII(12-TMC)(O2)]+ in the attack of the Mn(II) ion (eq. 2). The results can be explained by the difference of the enthalpy values of 65 kJ mol−1 for 2 and 49 kJ mol−1 for [NiIII(12-TMC)(O2)]+, and the difference of ΔΔG between complexes 2 and [NiIII(12-TMC)(O2)]+ is ~13 kJ mol−1.

To understand the effect of supporting ligands on the O2-transfer reaction, we performed kinetic studies with 4 and then compared the reactivities of 2 and 4. Since the O2-transfer from 4 to [Mn(14- TMC)]2+ was fast at 0 °C, reactions were carried out in acetone at −30 °C. Pseudo-first-order fitting of the kinetic data yielded a kobs value of 1.2 × 10−2 s−1 (SI, Figure S11b). Plot of kobs against the concentration of 4 gave a linear line, affording a second-order rate constant of k2 = 1.3 M−1 s−1 at −30 °C (Figure 7a, blue line). Activation parameters for the O2-transfer from 4 to [Mn(14-TMC)]2+ were determined to be ΔH‡ = 51 kJ mol−1 and ΔS‡ = −71 J mol−1 K−1, by plotting first-order-rate constants determined at different temperatures against 1/T (Figure 7b, blue line). It is worth noting that the enthalpy value of 51 kJ mol−1 for 4 is much smaller than that (ΔH‡ = 65 kJ mol−1) for 2 and that the difference of ΔΔG between complexes 2 and 4 is ~12 kJ mol−1. Consequently, as the ring size of macrocyclic ligands in the cobalt(III)-peroxo complexes increases from 12-TMC to 13-TMC, the O2- transfer reaction is facilitated and the reaction rate is enhanced ~600 fold (e.g., k2 = 1.9 × 10−4 M−1 s−1 for 2 and k2 = 1.2 × 10−1 M−1 s−1 for 4 at −50 °C).21 The results indicate that the peroxo group in 4 is more reactive than that in 2 on the attack of Mn(II) ion in the O2-transfer reaction. In addition, the reactivity of 4 is slightly lower than that of [NiIII(12-TMC)(O2)]+ (e.g., k2 = 1.2 × 10−1 M−1 s−1 for 4 and k2 = 2.0 × 10−1 M−1 s−1 for [NiIII(12-TMC)(O2)]+ at −50 °C).21 Thus, the reactivity order of [Ni(12-TMC)(O2)]+ > [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ ≫ [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+ is observed in O2-transfer reactions.

3. Conclusions

In this study, we synthesized and characterized mononuclear cobalt(III)-peroxo complexes bearing tetraazamacrocyclic ligands, [CoIII(12-TMC)(O2)]+ and [CoIII(13-TMC)(O2)]+. The structural and Co Kedge EXAFS spectroscopic characterization clearly showed that the peroxo ligand is bound in a side-on η2 fashion. The cobalt(III)-peroxo complexes have shown reactivities in the oxidation of aldehydes and O2-transfer reactions. In the aldehyde oxidation reactions, the nucleophilic reactivity of metal(III)- peroxo complexes was found to depend significantly on the ring size of the macrocyclic ligands, with the reactivity order of [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ > [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+. In the O2-transfer reactions, the cobalt(III)-peroxo complexes were shown to transfer their peroxo ligand to a manganese(II) complex. The O2-transfer reactions were found to depend significantly on the central metal ions and the supporting ligands, showing the reactivity order of [Ni(12-TMC)(O2)]+ > [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ ≫ [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+.

4. Experimental Section

Materials

All chemicals obtained from Aldrich Chemical Co. were the best available purity and used without further purification unless otherwise indicated. Solvents were dried according to published procedures and distilled under Ar prior to use.22 H2 18O2 (90% 18O-enriched, 2% H2 18O2 in water) and 18O2 (95% 18O-enriched) were purchased from ICON Services Inc. (Summit, NJ, USA). The 12-TMC and 13-TMC ligands were prepared by reacting excess amount of formaldehyde and formic acid with 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane and 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclotridecane, respectively.23 All air-sensitive reactions were performed using either a glove box or standard Schlenk techniques. [Ni(12-TMC)(O2)]+ and [Mn(14-TMC)]2+ were prepared according to the literature methods.12a,14a

Caution: Perchlorate salts are potentially explosive and should be handled with care!

Synthesis of [Co(12-TMC)(CH3CN)](ClO4)2

12-TMC (0.50 g, 2.19 mmol) was added to an acetonitrile solution (50 mL) of Co(ClO4)2·6H2O (0.96 g, 2.63 mmol). The mixture was refluxed for 12 h, giving a reddish brown solution. After cooling to room temperature, the solvent was then removed under vacuum to give a reddish brown solid, which was collected by filtration and washed with methanol several times to remove remained Co(ClO4)2·6H2O. Yield: 0.88 g (76%). UV−vis (ε, M−1 cm−1) in CH3CN: ~332 nm (70), 485 nm (200). ESI-MS (in CH3CN): m/z 164.0 [Co(12-TMC)]2+. Anal. Calcd for C14H31N5O8Cl2Co: C, 31.89; H, 5.93; N, 13.28. Found: C, 31.95; H, 5.90; N, 13.49. X-ray crystallographically suitable crystals were obtained by slow diffusion of diethyl ether into concentrated acetonitrile solution of [Co(12-TMC)(CH3CN)](ClO4)2.

Synthesis of [Co(13-TMC)(CH3CN)](ClO4)2

13-TMC (0.50 g, 2.06 mmol) was added to an acetonitrile solution (50 mL) of Co(ClO4)2·6H2O (0.90 g, 2.47 mmol). The mixture was refluxed for 12 h, affording a violet solution. After cooling to room temperature, the solvent was removed under vacuum to give a violet solid, which was collected by filtration and then washed with methanol several times to remove remained Co(ClO4)2·6H2O. Yield: 0.90 g (81%). UV−vis (ε, M−1 cm−1) in CH3CN: ~345 nm (120), 451 nm (120), 520 nm (150). ESI-MS (in CH3CN): m/z 170.9 [Co(13-TMC)]2+. Anal. Calcd for C15H33N5O8Cl2Co: C, 33.28; H, 6.14; N, 12.94. Found: C, 33.25; H, 6.28; N, 12.91. X-ray crystallographically suitable crystals were obtained by slow diffusion of diethyl ether into concentrated acetonitrile solution of [Co(13-TMC)(CH3CN)](ClO4)2.

Synthesis of [Co(12-TMC)(O2)](ClO4)

Aqueous 30 % H2O2 (28 μL, 0.25 mmol) was added to an acetonitrile solution (5 mL) containing [Co(12-TMC)(CH3CN)](ClO4)2 (0.026 g, 0.05 mmol) and triethylamine (14 μL, 0.1 mmol) at −20 °C, producing a purple solution. Diethyl ether (20 mL) was added to the resulting solution to yield purple powder, which was collected by filtration, washed with diethyl ether, and dried in vacuum. Yield: 0.017 g (81%). UV−vis (ε, M−1 cm−1) in CH3CN: 350 nm (450), ~500 nm (150), 560 nm (180), ~710 nm (90). ESI-MS (in CH3CN): m/z 319.1 for [Co(12- TMC)(16O2)]+ and m/z 323.1 for [Co(12-TMC)(18O2)]+. [Co(12-TMC)(18O2)]+ was prepared by adding 5 equiv H2 18O2 (16 μL 90% 18O-enriched, 2% H2 18O2 in water) to a solution containing [Co(12- TMC)(CH3CN)](ClO4)2 (2 mM) and 2 equiv triethylamine in CH3CN (2 mL) at ambient temperature. Xray crystallographically suitable crystals were obtained by addition of NaBPh4.

Synthesis of [Co(13-TMC)(O2)](ClO4)

Aqueous 30 % H2O2 (28 μL, 0.25 mmol) was added to an acetonitrile solution (5 mL) containing [Co(13-TMC)(CH3CN)](ClO4)2 (0.027 g, 0.05 mmol) and triethylamine (14 μL, 0.1 mmol) at −20 °C, producing a purple solution. Diethyl ether (20 mL) was added to the resulting solution to yield a purple powder, which was collected by filtration, washed with diethyl ether, and dried in vacuum. Yield: 0.013 (60%). UV−vis (ε, M−1 cm−1) in CH3CN: 348 nm (620), ~500 nm (170), 562 nm (210), ~710 nm (100). ESI-MS (in CH3CN): m/z 333.1 for [Co(13- TMC)(16O2)]+ and m/z 337.1 for [Co(13-TMC)(18O2)]+. [Co(13-TMC)(18O2)]+ was prepared by adding 5 equiv H2 18O2 (16 μL 90% 18O-enriched, 2% H2 18O2 in water) to a solution containing [Co(13- TMC)(CH3CN)](ClO4)2 (2 mM) and 2 equiv triethylamine in CH3CN (2 mL) at ambient temperature. Xray crystallographically suitable crystals were obtained by slow diffusion of diethyl ether into a concentrated acetonitrile solution of [Co(13-TMC)(O2)](ClO4).

Reactivity Studies

All reactions were run in an 1-cm UV cuvette by monitoring UV-vis spectral changes of reaction solutions, and rate constants were determined by fitting the changes in absorbance at 562 nm for [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+. Reactions were run at least in triplicate, and the data reported represent the average of these reactions. [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ was prepared by reacting [Co(13-TMC)(CH3CN)]+ with 5 equiv H2O2 in the presence of 2 equiv TEA. The intermediate [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ (2 mM) was then used in reactivity studies, such as the oxidation of cyclohexanecarboxaldehyde (CCA) and 2- phenylpropionaldehyde (2-PPA) at 25 °C. The purity of substrates was checked with GC and GC-MS prior to use. After completion of the reactions, products were analyzed by injecting reaction solutions directly into GC and GC-MS. Products were identified by comparing with authentic samples, and product yields were determined by comparison against standard curves prepared with authentic samples and using decane as an internal standard.

The O2-transfer reactions were carried out by adding appropriate amounts of [Mn(14-TMC)]2+ to a solution of [Co(12-TMC)(O2)]+ (1 mM) and [Co(13-TMC)(O2)]+ (1 mM), prepared with isolated cobaltperoxo complexes in acetone. All reactions were run in an 1-cm UV cuvette by monitoring UV-vis spectral changes of reaction solutions, and rate constants were determined by fitting the changes in absorbance at 453 nm. The O2-transfer reactions were further confirmed by taking ESI-MS of reaction solutions.

Physical Methods

UV-vis spectra were recorded on a Hewlett Packard 8453 diode array spectrophotometer equipped with a UNISOKU Scientific Instruments for low-temperature experiments or with a circulating water bath. Electrospray ionization mass spectra were collected on a Thermo Finnigan (San Jose, CA, USA) LCQ™ Advantage MAX quadrupole ion trap instrument, by infusing samples directly into the source using a manual method. The spray voltage was set at 4.2 kV and the capillary temperature at 80 °C. Resonance Raman spectra were obtained using a liquid nitrogen cooled CCD detector (CCD-1024×256-OPEN-1LS, HORIBA Jobin Yvon) attached to a 1-m single polychromator (MC-100DG, Ritsu Oyo Kogaku) with a 1200 groovs/mm holographic grating. An excitation wavelength of 441.6-nm was provided by a He-Cd laser (Kimmon Koha, IK5651R-G and KR1801C), with 15 mW power at the sample point. All measurements were carried out with a spinning cell (1000 rpm) at 0 °C. Raman shifts were calibrated with indene, and the accuracy of the peak positions of the Raman bands was ±1 cm−1. EPR spectra were taken at 4 K using a X-band Bruker EMX-plus spectrometer equipped with a dual mode cavity (ER 4116DM). Low temperatures were achieved and controlled with an Oxford Instruments ESR900 liquid He quartz cryostat with an Oxford Instruments ITC503 temperature and gas flow controller. EPR spectra were obtained on a JEOL JESFA200 spectrometer. 1H NMR spectra were measured with Bruker model digital AVANCE III 400 FTNMR spectrometer. The effective magnetic moments were determined using the modified 1H NMR method of Evans at room temperature.24 A WILMAD® coaxial insert (sealed capillary) tubes containing the blank acetonitrile-d3 solvent (with 1.0 % TMS) only was inserted into the normal NMR tubes containing the complexes (8 mM) dissolved in acetonitrile-d3 (with 0.05 % TMS). The chemical shift of the TMS peak (and/or solvent peak) in the presence of the paramagnetic metal complexes was compared to that of the TMS peak (and/or solvent peak) in the inner coaxial insert tube. The effective magnetic moment was calculated using the equation, μ = 0.0618(ΔνT/2fM)1/2, where f is the oscillator frequency (MHz) of the superconducting spectrometer, T is the absolute temperature, M is the molar concentration of the metal ion, and Δv is the difference in frequency (Hz) between the two reference signals.24c Crystallographic analysis was conducted with an SMART APEX CCD equipped with a Mo X-ray tube at the Crystallographic Laboratory of Ewha Womans University.

X-ray Crystallography

Single crystals of 1-(ClO4)2, 2-(BPh4)·CH3CN, 3-(ClO4)2, and 4- (ClO4)·CH3CN were picked from solutions by a nylon loop (Hampton Research Co.) on a hand made cooper plate mounted inside a liquid N2 Dewar vessel at ca. −40 °C and mounted on a goniometer head in a N2 cryostream. Data collections were carried out on a Bruker SMART AXS diffractometer equipped with a monochromator in the Mo Kα (λ = 0.71073 Å) incident beam. The CCD data were integrated and scaled using the Bruker-SAINT software package, and the structure was solved and refined using SHEXTL V 6.12.25 Hydrogen atoms were located in the calculated positions for 2- (BPh4)·CH3CN and 4-(ClO4)·CH3CN. Due to the high degree of disorder, however, hydrogen atoms could not be placed in ideal positions for 3-(ClO4)2 and the coordinated CH3CN of 1-(ClO4)2. Crystal data for 1-(ClO4)2: C14Cl2CoN5O8, Orthorhombic, Pnma, Z = 4, a = 14.718(2), b = 8.9472(12), c = 17.545(2) Å, V = 2310.4(5) Å3, μ = 1.022 mm−1, ρcalcd = 1.507 g/cm3, R1 = 0.0794, wR2 = 0.2227 for 2927 unique reflections, 160 variables. Crystal data for 2-(BPh4)·CH3CN: C38H51CoBN5O2, Monoclinic, P2(1)/c, Z = 4, a = 12.2417(15), b = 27.912(3), c = 11.1477(13) Å, β = 110.063(2)° V = 3577.9(7) Å3, μ = 0.520 mm−1, ρcalcd = 1.262 g/cm3, R1 = 0.0365, wR2 = 0.0523 for 8229 unique reflections, 429 variables. Crystal data for 3-(ClO4)2: C15Cl2CoN5O8, Tetragonal, P4/nmm, Z = 2, a = 9.2584(6), b = 9.2584(6), c = 14.1473(17) Å, V = 1212.68(18) Å3, μ = 0.972 mm−1, ρcalcd = 1.391 g/cm3, R1 = 0.0673, wR2 = 0.1807 for 890 unique reflections, 75 variables. Crystal data for 4-(ClO4)·CH3CN: C15H33ClCoN5O6, Orthorhombic, Pca2(1), Z = 4, a = 12.789(3), b = 9.5673(18), c = 17.218(3) Å, V = 2106.7(7) Å3, μ = 0.982 mm−1, ρcalcd = 1.494 g/cm3, R1 = 0.0345, wR2 = 0.1164 for 3632 unique reflections, 258 variables. The crystallographic data for 1-(ClO4)2, 2-(BPh4)·CH3CN, 3-(ClO4)2, and 4- (ClO4)·CH3CN are listed in Table 2, and Tables 1 and S1 list the selected bond distances and angles. CCDC-744572 for 1-(ClO4)2, 744571 for 2-(BPh4)·CH3CN, 744573 for 3-(ClO4)2 and 778131 for 4- (ClO4)·CH3CN contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif (or from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12, Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: (+44) 1223-336-033; or deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

Table 2.

Crystallographic Data and Structure Refinements for 1-(ClO4)2, 2-(BPh4)·CH3CN, 3-(ClO4)2, and 4-(ClO4)·CH3CN

| 1-(ClO4)2 | 2-(BPh4)·CH3CN | 3-(ClO4)2 | 4-(ClO4)·CH3CN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C14H28Cl2CoN5O8 | C38H51CoBN5O2 | C15Cl2CoN5O8 | C15H33ClCoN5O6 |

| Formula weight | 524.24 | 679.58 | 508.03 | 473.84 |

| Temperature (K) | 298(2) | 170(2) | 298(2) | 170(2) |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 |

| Crystal system | orthorhombic | monoclinic | tetragonal | orthorhombic |

| Space group | Pnma | P2(1)/c | P4/nmm | Pca2(1) |

| Unit cell dimensions | ||||

| a (Å) | 14.718(2) | 12.2417(15) | 9.2584(6) | 12.789(3) |

| b (Å) | 8.9472(12) | 27.912(3) | 9.2584(6) | 9.5673(18) |

| c (Å) | 17.545(2) | 11.1477(13) | 14.1473(17) | 17.218(3) |

| α(°) | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| β (°) | 90.00 | 110.063(2) | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| γ(°) | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| Volume (Å3) | 2310.4(5) | 3577.9(7) | 1212.68(18) | 2106.7(7) |

| Z | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| dcalcd (g/cm−3) | 1.507 | 1.262 | 1.391 | 1.494 |

| μ (mm−1) | 1.022 | 0.520 | 0.972 | 0.982 |

| Reflections collected | 13894 | 21911 | 7455 | 22983 |

| Independent reflections [R(int)] | 2927 [0.0966] | 8229 [0.0688] | 890 [0.0587] | 3632 [0.0352] |

| Parameters | 160 | 429 | 75 | 258 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.030 | 0.960 | 1.065 | 1.003 |

| Final R [I > 2σ(I)] | 0.0794 | 0.0365 | 0.0673 | 0.0345 |

| Final wR [I > 2σ(I)] | 0.2227 | 0.0481 | 0.1745 | 0.1164 |

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy

The Co K-edge X-ray absorption spectra of 2 and 4 were measured at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) on the focused 16-pole 2.0 T wiggler beam line 9-3 under standard ring conditions of 3 GeV and 80–100 mA. A Si(220) double crystal monochromator was used for energy selection. A Rh-coated harmonic rejection mirror and a cylindrical Rh-coated bent focusing mirror were used. The solution samples for 2 and 4 (5 mM in Co and ~120 μL) were transferred into 2 mm delrin XAS cells with 37 μm Kapton tape windows at −20 °C. The samples were immediately frozen after preparation and stored under liquid N2. During data collection, the samples were maintained at a constant temperature of ~10 – 15 K using an Oxford Instruments CF 1208 liquid helium cryostat. Data were measured to k = 14 Å−1 in fluorescence mode by using a Canberra Ge 30-element array detector. Internal energy calibration was accomplished by simultaneous measurement of the absorption of a Co-foil placed between two ionization chambers situated after the sample. The first inflection point of the foil spectrum was fixed at 7709.5 eV. Data presented here are 8-scan average spectra for both 2 and 4, which were processed by fitting a secondorder polynomial to the pre-edge region and subtracting this from the entire spectrum as background. A four-region spline of orders 2, 3, 3 and 3 was used to model the smoothly decaying post-edge region. The data were normalized by subtracting the cubic spline and assigning the edge jump to 1.0 at 7725 eV using the Pyspline program.26

Theoretical EXAFS signals χ(k) were calculated by using FEFF (macintosh version 8.4)27–29 and the crystal structures of 2 and 4. The theoretical models were fit to the data using EXAFSPAK.30 The structural parameters varied during the fitting process were the bond distance (R) and the bond variance σ2, which is related to the Debye-Waller factor resulting from thermal motion, and static disorder of the absorbing and scattering atoms. The non-structural parameter E0 (the energy at which k = 0) was also allowed to vary but was restricted to a common value for every component in a given fit. Coordination numbers were systematically varied in the course of the fit but were fixed within a given fit.

Electronic Structure Calculations

Gradient-corrected, (GGA) spin-unrestricted, brokensymmetry, density functional calculations were carried out using the ORCA31,32 package on a 8-cpu linux cluster. The Becke8833,34 exchange and Perdew8635 correlation non-local functionals were employed to compare the geometric and electronic structure differences between 2 and 4. The coordinates obtained from the crystal structure of 2 and 4 were used as the starting input structure. The core properties basis set CP(PPP)32,36 (as implemented in ORCA) was used on Co and the Ahlrichs’ all electron triple-ζ TZVP37,38 basis set was used on all other atoms. The calculations were performed in a dielectric continuum using the conductor like screening model (COSMO). Acetonitrile was chosen as the dielectric material. Population analyses were performed by means of Mulliken Population Analysis (MPA). Compositions of molecular orbitals and overlap populations between molecular fragments were calculated using the QMForge.26

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by NRF/MEST of Korea through the CRI, and WCU (R31-2008-000-10010-0), and GRL (2010-00353) Programs (W.N.), the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan through the Global COE program and Priority Area (No. 20050029) (T.O.), and NIH grant DK-31450 (E.I.S.). SSRL operations are funded by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology program is supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Non-phase shift corrected Fourier transform data, their corresponding EXAFS data, and FEFF best fit parameters for 2 and 4. X-ray crystal structures of 1 and 3, resonance Raman data of 2 and 4, EPR data of 1 – 4, COSY NMR spectrum of 2, kinetic data of the reactions of 4 with 2-PPA and para-X-Ph-CHO, UV-vis spectral changes of the O2-transfer reactions of 2 and 4, and X-ray crystallographic files of 1 – 4 in CIF format. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Ortiz de Montellano PR, editor. Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry. 3. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]; (b) Que L Jr, Tolman WB, editors. Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II. Vol. 8. Elsevier; Oxford: 2004. [Google Scholar]; (c) Meunier B, editor. Biomimetic Oxidations Catalyzed by Transition Metal Complexes. Imperial College Press; London: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Sen K, Hackett JC. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10293–10305. doi: 10.1021/ja906192b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shyadehi AZ, Lamb DC, Kelly SL, Kelly DE, Schunck WH, Wright JN, Corina D, Akhtar M. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12445–12450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Vaz AD, Pernecky SJ, Raner GM, Coon MJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4644–4648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Roberts ES, Vaz ADN, Coon MJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8963–8966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.8963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valentine JS. Chem Rev. 1973;73:235–245.Basolo F, Hoffman BM, Ibers JA. Acc Chem Res. 1975;8:384–392.Vaska L. Acc Chem Res. 1976;9:175–183.Klotz IM, Kurtz DM., Jr Chem Rev. 1994;94:567–568.and review articles in the special issue. Bakac A. Coord Chem Rev. 2006;250:2046–2058.Nam W. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:465. doi: 10.1021/ar700027f.and review articles in the special issue.

- 4.(a) Wertz DL, Valentine JS. Struct Bonding. 2000;97:37–60. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gibson DT, Parales RE. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2000;11:236–243. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wertz DL, Sisemore MF, Selke M, Driscoll J, Valentine JS. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:5331–5332. [Google Scholar]; (d) Goto Y, Wada S, Morishima I, Watanabe Y. J Inorg Biochem. 1998;69:241–247. [Google Scholar]; (e) Hashimoto K, Nagatomo S, Fujinami S, Furutachi H, Ogo S, Suzuki M, Uehara A, Maeda Y, Watanabe Y, Kitagawa T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:1202–1205. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020402)41:7<1202::aid-anie1202>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Annaraj J, Suh Y, Seo MS, Kim SO, Nam W. Chem Commun. 2005:4529–4531. doi: 10.1039/b505562h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Kovaleva EG, Lipscomb JD. Science. 2007;316:453–457. doi: 10.1126/science.1134697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Prigge ST, Eipper BA, Mains RE, Amzel LM. Science. 2004;304:864–867. doi: 10.1126/science.1094583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mirica LM, Ottenwaelder X, Stack TDP. Chem Rev. 2004;104:1013–1045. doi: 10.1021/cr020632z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lewis EA, Tolman WB. Chem Rev. 2004;104:1047–1076. doi: 10.1021/cr020633r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hatcher LQ, Karlin KD. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9:669–683. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0578-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Chen P, Solomon EI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13105–13110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402114101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Chen P, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4991–5000. doi: 10.1021/ja031564g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Klinman JP. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3013–3016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Itoh S. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Cramer CJ, Tolman WB. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:601–608. doi: 10.1021/ar700008c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Rolff M, Tuczek F. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:2344–2347. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Himes RA, Karlin KD. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kunishita A, Kubo M, Sugimoto H, Ogura T, Sato K, Takui T, Itoh S. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2788–2789. doi: 10.1021/ja809464e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Maiti D, Lee DH, Gaoutchenova K, Würtele C, Holthausen MC, Sarjeant AAN, Sundermeyer J, Schindler S, Karlin KD. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:82–85. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Fujii T, Yamaguchi S, Hirota S, Masuda H. Dalton Trans. 2008:164–170. doi: 10.1039/b712572k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Maiti D, Fry HC, Woertink JS, Vance MA, Solomon EI, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:264–265. doi: 10.1021/ja067411l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Hikichi S, Akita M, Moro-oka Y. Coord Chem Rev. 2000;198:61–87. [Google Scholar]; (b) Busch DH, Alcock NW. Chem Rev. 1994;94:585–623. [Google Scholar]; (c) Smith TD, Pilbrow JR. Coord Chem Rev. 1981;39:295–383. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey CL, Drago RS. Coord Chem Rev. 1987;79:321–332. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Busch DH, Jackson PJ, Kojima M, Chmielewski P, Matsumoto N, Stevens JC, Wu W, Nosco D, Herron N, Ye N, Warburton PR, Masarwa M, Stephenson NA, Christoph G, Alcock NW. Inorg Chem. 1994;33:910–923. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schaefer WP, Huie BT, Kurilla MG, Ealick SE. Inorg Chem. 1980;19:340–344. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Terry NW, Amma EL, Vaska L. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:653–655. [Google Scholar]; (b) Egan JW, Jr, Haggerty BS, Rheingold AL, Sendlinger SC, Theopold KH. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:2445–2446. [Google Scholar]; (c) Rahman AFMM, Jackson WG, Willis AC. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:7558–7560. doi: 10.1021/ic040044z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hu X, Castro-Rodriguez I, Meyer K. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13464–13473. doi: 10.1021/ja046048k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Zombeck A, Drago RS, Corden BB, Gaul JH. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:7580–7585. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hamilton DE, Drago RS, Zombeck A. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:374–379. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Cho J, Sarangi R, Annaraj J, Kim SY, Kubo M, Ogura T, Solomon EI, Nam W. Nature Chem. 2009;1:568–572. doi: 10.1038/nchem.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kieber-Emmons MT, Annaraj J, Seo MS, Van Heuvelen KM, Tosha T, Kitagawa T, Brunold TC, Nam W, Riordan CG. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14230–14231. doi: 10.1021/ja0644879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Fujisawa K, Tanaka M, Moro-oka Y, Kitajima N. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:12079–12080. [Google Scholar]; (b) Spencer DJE, Aboelella NW, Reynolds AM, Holland PL, Tolman WB. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2108–2109. doi: 10.1021/ja017820b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gherman BF, Cramer CJ. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:7281–7283. doi: 10.1021/ic049958b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Aboelella NW, Kryatov SV, Gherman BF, Brennessel WW, Young VG, Jr, Sarangi R, Rybak-Akimova EV, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI, Cramer CJ, Tolman WB. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:16896–16911. doi: 10.1021/ja045678j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Reynolds AM, Gherman BF, Cramer CJ, Tolman WB. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:6989–6997. doi: 10.1021/ic050280p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Sarangi R, Aboelella N, Fujisawa K, Tolman WB, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8286–8296. doi: 10.1021/ja0615223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Würtele C, Gaoutchenova E, Harms K, Holthausen MC, Sundermeyer J, Schindler S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:3867–3869. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Seo MS, Kim JY, Annaraj J, Kim Y, Lee YM, Kim SJ, Kim J, Nam W. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:377–380. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Annaraj J, Cho J, Lee YM, Kim SY, Latifi R, de Visser SP, Nam W. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:4150–4153. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho J, Woo J, Nam W. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5958–5959. doi: 10.1021/ja1015926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Although the structure of [Co(14-TMC)(O2)]+ was not available, we have reported the reactivity of [Co(14-TMC)(O2)]+ in the deformylation of aldehydes: Jo Y, Annaraj J, Seo MS, Lee YM, Kim SY, Cho J, Nam W. J Inorg Biochem. 2008;102:2155–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.08.008.

- 17.Cramer CJ, Tolman WB, Theopold KH, Rheingold AL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3635–3640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0535926100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujita E, Furenlid LR, Renner MW. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:4549–4550. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girerd JJ, Banse F, Simaan AJ. Struct Bonding. 2000;97:145–177. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaz ADN, Roberts EA, Coon MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:5886–5887. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Due to the large reactivity difference of the metal-peroxo complexes, the k2 values were determined at different temperatures and normalized using the Erying equation.

- 22.Armarego WLF, Perrin DD, editors. Purification of Laboratory Chemicals. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halfen JA, Young VG., Jr Chem Commun. 2003:2894–2895. doi: 10.1039/b311520h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Evans DF. J Chem Soc. 1959:2003–2005. [Google Scholar]; (b) Löliger J, Scheffold R. J Chem Edu. 1972;49:646–647. [Google Scholar]; (c) Evans DF, Jakubovic DA. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 1988:2927–2933. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheldrick GM. SHELXTL/PC Version 612 for Windows XP. Bruker AXS Inc; Madison, Wisconsin, USA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tenderholt A. Pyspline and QMForge. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rehr JJ, Albers RC. Rev Mod Phys. 2000;72:621–654. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rehr JJ, Mustre de Leon J, Zabinsky SI, Albers RC. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:5135–5140. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mustre de Leon J, Rehr JJ, Zabinsky SI, Albers RC. Phys Rev B. 1991;44:4146–4156. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.44.4146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.George GN. EXAFSPAK and EDG-FIT. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neese F. ORCA: an ab initio, DFT and semiempirical Electronic Structure Package, Version 2.4, Revision 16. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neese F, Olbrich G. Chem Phys Lett. 2002;362:170–178. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becke AD. Phys Rev A. 1988;38:3098–3100. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becke AD. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perdew JP. Phys Rev B. 1986;33:8822–8824. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.33.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinnecker S, Slep LD, Bill E, Neese F. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:2245–2254. doi: 10.1021/ic048609e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schaefer A, Horn H, Ahlrichs R. J Chem Phys. 1992;97:2571–2577. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaefer A, Huber C, Ahlrichs R. J Chem Phys. 1994;100:5829–5835. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.