Abstract

The use of recombinant adeno-associated viral (rAAV) vectors as a means of gene delivery to the central nervous system has emerged as a potentially viable method for the treatment of several types of degenerative brain diseases. However, a limitation of typical intracranial injections into the adult brain parenchyma is the relatively restricted distribution of the delivered gene to large brain regions such as the cortex, presumably due to confined dispersion of the injected particles. Optimizing the administration techniques to maximize gene distribution and gene expression is an important step in developing gene therapy studies. Here, we have found additive increases in distribution when 3 methods to increase brain distribution of rAAV were combined. The convection enhanced delivery (CED) method with the step-design cannula was used to deliver rAAV vector serotypes 5, 8 and 9 encoding GFP into the hippocampus of the mouse brain. While the CED method improved distribution of all 3 serotypes, the combination of rAAV9 and CED was particularly effective. Systemic mannitol administration, which reduces intracranial pressure, also further expanded distribution of GFP expression, in particular, increased expression on the contralateral hippocampi. These data suggest that combining advanced injection techniques with newer rAAV serotypes greatly improves viral vector distribution, which could have significant benefits for implementation of gene therapy strategies.

INTRODUCTION

Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors have recently emerged as a promising and novel means by which transgenes can be delivered to different tissue types successfully in a large range of animal species including humans. rAAVs have a number of advantageous characteristics that identify them as one of the most feasible gene transfer vectors in the treatment of a variety of diseases, including neurological diseases. The most attractive characteristics of rAAV are their lack of pathogenicity, typical persistence of the transgene as an episome, low immunogenicity, removal of all viral genes and in many paradigms long-term gene expression. Furthermore, there are now a number of different rAAV serotypes available that confer different cellular tropisms (Daya and Berns, 2008).

Unfortunately, one disadvantage to single intracranial injections of rAAV vectors into the brain parenchyma of large animal models or humans will be the restricted distribution of the rAAV vectors to relatively small volumes of the brain. Convection enhanced delivery (CED) is a method of delivering clinically relevant volumes of therapeutic agents to significantly larger areas of the brain in a direct intracranial injection procedure. The CED technique is designed to utilize the phenomenon of bulk flow and positive pressure to distribute macromolecules to a large volume within solid tissue. Scientists originally proposed the CED technique in the early 1990s as a method of delivering drugs, or macromolecules, directly to the parenchyma that would not normally cross the blood brain barrier (Raghavan et al., 2006). Due to the lack of approved drugs that can be intracranially administered into the brain and the difficulty in predicting methods that ensure delivery of the therapeutic agent to its target site, CED remains an experimental procedure. However, research into CED delivery devices is under current investigation by several researchers (Bankiewicz et al., 2000; Raghavan et al., 2006).

The CED method was previously investigated in gene therapy studies as a way to increase the distribution of rAAV2 vectors in the brain. Studies conducted by Bankiewicz et. al. (2000) revealed that CED can significantly increase gene transfer and distribution of rAAV expressing AADC in the striatum of MPTP-treated monkeys. The rAAV vector was found to be safely distributed throughout the entire region of the striatum compared to the simple injection method where the distribution was severely limited (Bankiewicz et al., 2000). Similar results were replicated in the rat brain by Cunningham et. al. (2000) with rAAV2 expressing thymidine kinase (TK) where the CED method showed robust gene transfer and increased distribution area within the putamen. CED injections in the striatum were found to distribute the rAAV-TK throughout the striatum after a single injection into this region and TK immunoreactive cells were also found outside the striatum, in the globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus, thalamus, and substantia nigra (Cunningham et al., 2000; Hadaczek et al., 2006).

One of the mechanistic limitations of the CED method as well as the simple injection method is the reflux of injected material from the needle tract during infusion and upon the removal of the cannula. Krauze et. al. (Krauze et al., 2005b) developed a step cannula design which effectively reduces reflux by placing silicone coated tubing within the cannula creating a horizontal step that acts as a barrier to the backflow of fluid. The optimization of more efficient cannula designs coupled with the encouraging results from studies showing enhanced gene transfer and distribution emphasize the therapeutic potential of the CED method in helping overcome some of the mechanical disadvantages of gene delivery for gene therapy (Krauze et al., 2005a).

The use of osmotic agents such as mannitol is another method that can be used to increase the area of distribution of macromolecules throughout the CNS. Mannitol when injected i.p. induces systemic hyperosmolarity and efflux of fluid from the brain, thereby lowering intracranial pressure and facilitating the movement of particles through the interstitial space. High concentrations of intravenously delivered mannitol are currently used in patients with traumatic brain injury to reduce excessive intracranial pressure. Several studies have also shown that with intra-arterial infusion of mannitol the blood brain barrier can be opened to enhance the distribution of chemotherapeutics throughout the CNS in both rats and humans (Muldoon et al., 1995; Nilaver et al., 1995; Rapoport, 2001). Further, the use of systemic mannitol injection was shown to be effective in increasing the distribution of rAAV2 within the brain (Burger, 2004; Fu et al., 2003)}.

Therefore, in this particular study we tested whether these distinct methods (mannitol, CED and serotype optimization) of increasing the volume of therapeutic gene expression from rAAV were additive, or if there was some maximal volume of AAV gene expression (keeping injection volume constant) that could not be exceeded. We demonstrate that the use of both mannitol and CED can significantly increase the expression of transgene in an additive manner irrespective of serotype, leading to efficient expression of a transduced gene in most of the hippocampus ispilateral to the injection site, and also contralateral to the injection site.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

C57BL6 mice were acquired from the breeding colonies at the University of South Florida. Multiple mice were housed together whenever possible until the time of use in the study; mice were then singly housed just before surgical procedures until the time of sacrifice. Study animals were given water and food (ad libitum) and maintained on the twelve hour light/dark cycle and standard vivarium conditions. Mice aged 9 to 11 months were used for all experimental procedures with an n = 4 – 6 for each experimental group.

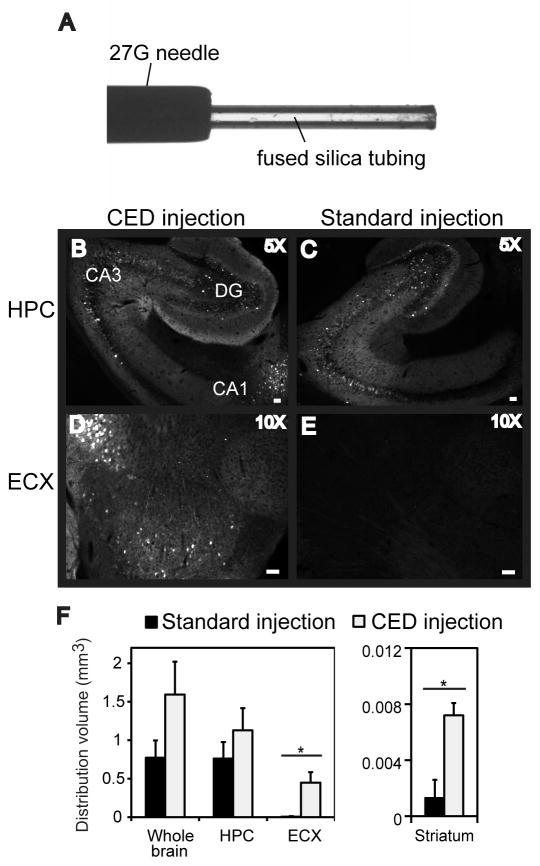

Step Design Cannula

The step design cannula was used for all CED intracranial surgeries and a beveled 26-gauge needle was used for standard injections. The step design cannula was prepared as follows: fused silica tubing (inner diameter ~100 μm; outer diameter ~167 μm; Polymicro Technologies, Pheonix, AZ, part# 1068150020) was inserted into a Hamilton removable 27-gauge stainless steel blunt ended needle (Hamilton, RN NDL (27/2″/3)S, cat# 7762-01) and fixed in place with super glue (Krauze et al., 2005b). The end of the silica tubing was cut leaving ~1 mm of tubing protruding from the end of the needle. Image shown in Fig. 1A. The modified needle was used in a 10 μL removable needle Hamilton syringe.

FIG. 1.

GFP expression is increased following intracranial administration of rAAV5 into the hippocampus using CED into 9-month-old mice. Panel A shows an image of the CED needle setup. The CED method (B, D, F) is compared to the standard injection method (C, E, F). Hippocampus (HPC), dentate gyrus (DG), cornu ammonis (CA) and entorhinal cortex (ECX) regions are shown. The volume of GFP fluorescence is graphed in panel G. The asterisk (*) indicates significance with a p-value < 0.05. The scale bar represents 120 μm for panels B, C, and 50 μm for panels D, E).

GFP Expression Following CED or traditional injection

Surgery was performed on animals using a stereotaxic apparatus. Immediately before surgery, mice were weighed and then anesthetized using isoflurane. The surgical procedure was performed by exposing the cranium with an incision along the median sagittal plane, and holes were drilled through the cranium. Previously determined coordinates for burr holes, taken from bregma were as follows; hippocampus, anteroposterior, −2.7mm; lateral +/−2.5mm, vertical, −3.0mm. In prior studies these coordinates typically produce placements at the CA3/CA4 junction between the tips of the upper and lower blades of the dentate gyrus granule cell layer when examined in horizontal sections (as used for all studies here). Burr holes were drilled using a dental drill bit (SSW HP-3, SSWhite Burs Inc., Lakewood, NJ). Mice (n =6) received rAAV vector encoding for GFP expression (1.5 × 1012 vector genomes (vg)/ml) via an intracranial injection using the CED injection method or a conventional injection method into the hippocampus. The CED method used the step design cannula to inject a 2 μl volume at a flow rate of 5 μl/min (infusion time of 0.4 min). In contrast, the conventional injection method used a blunt ended stainless steel needle (no insert) to inject 2 μl at a flow rate of 0.5 μl/min (4 min infusion time). Prior to removal the needle was left in place for at least 1 min after injection to allow distribution of the virus.

Six weeks after surgery mice were weighed, overdosed with pentobarbital (200 mg/kg) and perfused with 25 ml of 0.9% normal saline solution, then with 50 ml of freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were collected from the animals immediately following perfusion and immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h. Mouse brains were cryoprotected in successive incubations of 10%, 20% and 30% solutions of sucrose; 24 h in each solution. Subsequently, brains were frozen on a cold stage and sectioned in the horizontal plane (25 μm thickness) on a sliding microtome and stored in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) with 0.2% sodium azide solution at 4°C.

Six to eight sections 300 μm apart spanning the site of injection were chosen and free-floating immunochemical and histological analysis was performed to determine gene expression using an anti-GFP antibody at a concentration 1:3,000 (Chemicon; Temecula, CA). Immunohistochemical procedural methods were analogous to those described by Gordon et al. 2002 for each marker. Animal tissue was placed in multisample staining tray and endogenous peroxidase was blocked (10% methanol, 30% H202, in PBS). Tissue samples were then permeabilized (with lysine 0.2%, 1% Triton X-100 in PBS solution), and incubated overnight in appropriate primary antibody. Sections were washed in PBS, then incubated in the corresponding biotinylated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The tissue was again washed after a 2 h incubation period and incubated with Vectastin® Elite® ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for enzyme conjugation. Finally, sections were stained using 0.05% diaminobenzidine and 0.3% H202. Tissue sections were mounted onto slides, dehydrated, and cover slipped.

To evaluate the mechanical injury profile of the CED injection method, mice were injected with saline (n =6) using either the CED method or the conventional injection method into the right or left hippocampus respectively. Animals were sacrificed 4 days post surgery as described above to determine the extent to which the methods increased microglial activation or caused mechanical tissue damage using histology. Six sections 100 μm apart spanning the site of injection were chosen from each animal and a series of sections were immunostained for CD45 (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC) to assess microglial activation. Immunostaining was performed as described above except that 0.5% nickelous ammonium sulfate was added to the color development step. Another series of sections were mounted on slides and stained with fluoro-jade (0.001%, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to assess the degree of neurotoxicity. Fluoro-jade is an anionic fluorochrome that selectively stains degenerating neurons effectively detecting neuropathic lesions by fluorescent microscopy (Schmued et al., 1997). Finally, a series of sections (6 per animal) were mounted on slides and stained with the cresyl violet stain (0.05%, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The cresyl violet stains all Nissl bodies of the rough endoplasmic reticulum and other acidic components in neuronal cytoplasm and cell nuclei. Neurotoxicity is revealed by development of pyknosis in neurons and glial hyperplasia.

GFP Expression with Serotypes rAAV 5, 8, and 9

Study animals were assigned to one of three treatment groups receiving rAAV serotype 5, 8, or 9. All rAAV vectors contain a coding sequence for green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the hybrid CMV chicken beta-actin promoter with the rAAV2 terminal repeat DNA sequences. All animals received an intracranial injection into the right hippocampus and all injections were performed using the CED technique described earlier. Each group received a single intracranial injection of 2 μl of each respective rAAV vector expressing GFP (1.5 × 1011vg/ml). All viruses were diluted to the lowest equivalent titer prior to injection; therefore, the titer for the rAAV5 is lower in this study than in the previous study. All intracranial surgeries were performed on a stereotaxic apparatus using predetermined stereotaxic coordinates for the mouse hippocampus described earlier. Six weeks after injection animals were sacrificed and brain tissue was collected as described earlier.

GFP Expression with Serotypes rAAV 5 or 9 and Mannitol

Animals were assigned to one of four groups. Group 1 and 2 received intracranial injection of 2 μl of either rAAV serotype 5 or 9 expressing GFP (1.5 × 1011vg/ml) into the right hippocampus using the CED injection method. Group 3 and 4 received a single systemic intraperitoneal injection of 25% w/v mannitol (Sigma) (3 mL/100g mouse at ~0.1 mL/min) administered 15 minutes before the identical intracranial injections of rAAV. The left hemisphere in all animals remained untreated. Surgery was performed on animals using a stereotaxic apparatus with burr hole coordinates previously described. Six weeks post injection animals were sacrificed and brain tissue was collected as described earlier. Sections were immunohistochemically stained using anti-GFP antibody (1:3000; Chemicon; Temecula, CA) to test for gene distribution and expression. In addition, to assess the cellular localization of the GFP expression, some sections were stained using cell-type specific markers and fluorescently-tagged secondary antibodies. Astrocytes were identified by expression of GFAP (Dako), while neurons were identified with anti-NeuN (Chemicon).

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

For the first two studies, DAB immunostained sections were imaged using an Evolution MP digital camera mounted on an Olympus BX51 microscope. Immunoflourescent double labeled images were taken using an Olympus FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope. Six to eight horizontal brain sections (~300 μm apart) were taken from each animal and four nonoverlapping images near the site of injection from each of these sections were captured (24 measurements per mouse). Images were taken from the same location in all animals. Quantification of positive staining surrounding and including the injection site in the right hippocampus and the corresponding regions in the left hemisphere were determined using Image-Pro® Plus (Media Cybernetics®, Silver Springs, MD). The mannitol and serotype experiments was analyzed using the Zeiss Mirax Scan 150 microscope and Image Analysis software (created by Andrew Lesniak) was used to quantitate the area of positive stain in each whole brain section or brain region. The software used hue, saturation and intensity (HSI) to segment the image fields. Thresholds for object segmentation were established with images of high and low levels of staining to identify positive staining over any background levels. These limits were held constant for the analysis of every section in each study (Gordon et al., 2002). The volume of transduction was calculated based on the area of positive stain multiplied by the thickness of the sections and the distance between sections. ANOVA statistical analysis was performed using StatView® version 5.0.1 (SAS Institute, Raleigh, NC). rAAV production and purification: rAAV5, rAAV8 and 9 were purified as described by Levites et al. (Levites et al., 2006).

RESULTS

GFP Expression Using CED

Nine-month-old C57BL6 mice were injected with rAAV5 encoding GFP bilaterally into the left and right hippocampus using either the CED injection method or the conventional injection method. rAAV serotype 5 was chosen for the initial experiment because it had previously been shown to give better transduction of neurons than the other commonly used serotype 2 (Burger et al., 2004). The CED injection method was performed as described in the methods section, using the step design cannula with a flow rate of 5 μl/min and a total injection time of approximately 0.4 min (2 min including the time the cannula remained in the injection site to further prevent backflow of the rAAV vector material). The standard injection was performed at a flow rate of 0.5 μl/min, with a total injection time of approximately 5 min. The animals survived 6 weeks post-surgery and histology was performed to assess gene distribution and expression. Regions of the hippocampus receiving the CED injection showed more robust expression of GFP and an increased area of distribution than the conventional injection method (Fig. 1B–E). In addition, GFP expression was detected in regions distant from the initial site of injection in the hemisphere that received the CED injection method. Areas with positive GFP staining included the entorhinal cortex (Fig 1F), as well as some neurons in the striatum and thalamus

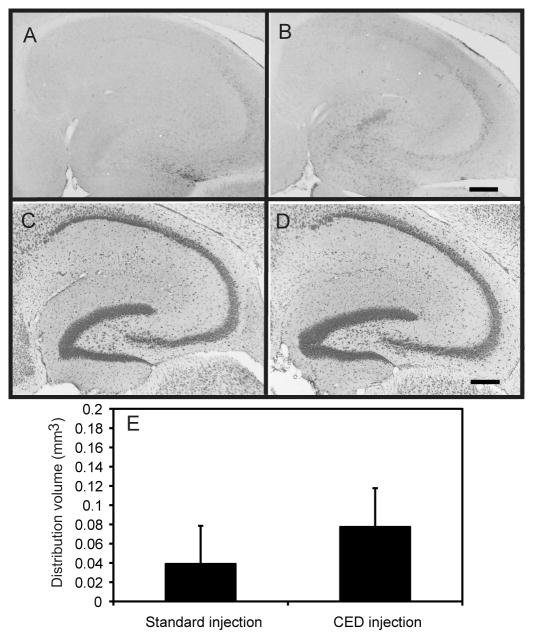

A second aspect of this experiment was to determine the safety profile of the CED method with respect to mechanical damage of parenchymal brain tissue. Mice (n=6) were bilaterally injected with PBS in the same manner described above using both the CED and conventional injection methods. The mice were sacrificed and tissue was analyzed 4 days post injection and histology performed. Neurotoxity was determined using the fluoro-jade stain. Positive fluoro-jade staining was only seen in a very small area at the injection site of two animals and was not statistically different in the CD and conventional injection groups (data not shown). Microglial expression was analyzed to assess the increase in microglial activation due to the mechanical technique. CD45 is a protein tyrosine phosphatase that is only expressed when microglial cells become activated, in this case, as a result of tissue damage. Immunohistochemistry revealed that CD45 staining was increased slightly in both groups after the injections. This increase was limited to the area immediately surrounding the cannula tract and was not significantly different in the two injection groups (Fig. 2, panels A, B, E). The cresyl violet stain, for Nissl bodies of the rough endoplasmic reticulum and other acidic components, did not reveal any significant areas of pyknosis or glial hyperplasia, implying little neurotoxicity was present with either method (Fig. 2, panels C–D).

FIG. 2.

The CED method does not result in neuron loss or significant increase in CD45 expression. CD45 immunostaining in the hippocampus appears similar after the traditional injection method (panel A) or the CED injection method (panel B). No obvious loss of Nissl staining was observed after the traditional injection method (panel C) or the CED injection method (panel D). Quantification of CD45 immunostaining is represented as volume of stain in panel E. Scale bar = 120 μm for all panels.

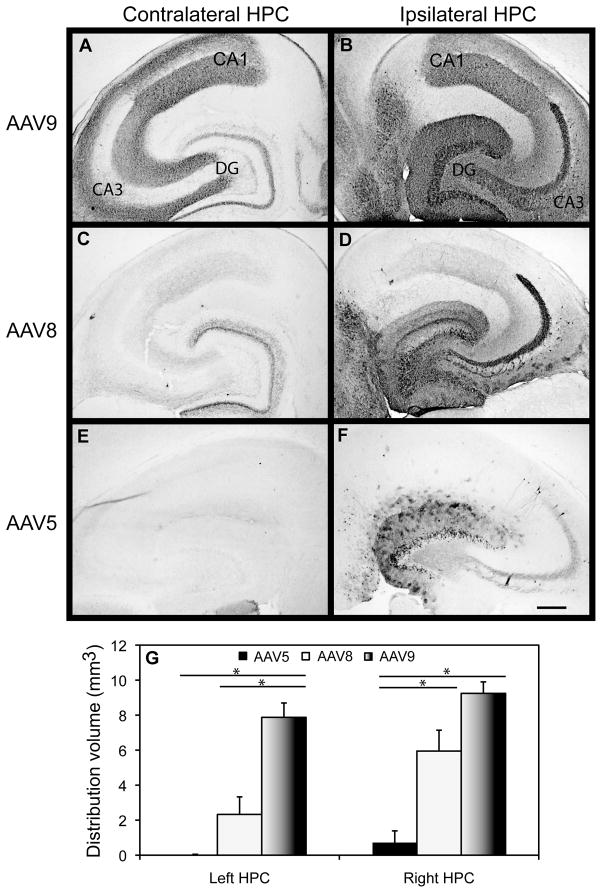

GFP Expression with Serotypes rAAV 5, 8, and 9

During the course of our examination of rAAV5 with the CED method of injection, a number of other rAAV serotypes were cloned and converted into vector systems. These serotypes have been shown to give significantly increased transduction of brain regions (Klein et al., 2006; Klein et al., 2008). Therefore, we wanted to examine two of these serotypes with the CED method. Three different vector serotypes 5, 8 and 9 were administered into the right hippocampus of mice using the CED method. A comparison of the area of GFP expression revealed that serotype 9 was widely distributed throughout the ipsilateral hippocampus (Fig. 3). rAAV8 and 9 serotypes revealed intense staining of GFP positive neurons in all three CA regions of the hippocampus, very intense staining in the granular and molecular layers of the dentate gyrus, as well as and a large number of positive cells in the hilus and CA3 of the ipsilateral hippocampus. The majority of cells that had been transduced had intense GFP staining not only of the cell body but also of the axonal and dendritic projections (although slightly less intense). These axonal projections were positive throughout the hippocampus and corpus callosum (which contains axonal connections between the right and left hemisphere). A large number of intensely stained cells were also evident in neurons distal to the site of injection, and were observed in the entorhinal cortex, anterior cortex, thalamic nuclei, striatum, septal nuclei, superior colliculus, subiculum and cerebellum of the ipsilateral hemisphere. Conversely, rAAV serotype 5 was expressed in far fewer cells, which were primarily located in the granular and molecular cell layers of the dentate gyrus, with only a few cells in the hilus and pyramidal cell layers. A few GFP positive cells were observed in the entorhinal cortex (left side of panels 3B,D and F) and lateral thalamic region but these were insignificant in comparison to serotypes 8 and 9.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of rAAV serotypes 5, 8, and 9 expressing GFP in the hippocampus (HPC). Images are presented depicting GFP expression in the contralateral HPC (A, C, E) and ipsilateral HPC (panels B, D, F) following a single CED intracranial injection into the right HPC with rAAV5, 8, or 9 serotypes. Quantification of the volume of positive staining for GFP is shown graphically in panel G. The asterisk (*) indicates significance with a p-value < 0.05. Scale = 120 μm. HPC= Hippocampus, DG= Dentate gyrus, CA=cornu ammonis.

Very few cell bodies were positively stained in the contralateral hemispheres of mice receiving the rAAV8 and 9 serotypes; rather, positive staining appeared restricted to axon terminals in the molecular layers adjacent to the granular and pyramidal cell layers. As observed in the hippocampus, some GFP expression was observed in the contralateral entorhinal cortex of the rAAV8 and 9 treatment groups (on the right of panels 3A, C and E), but it was less intense and appeared restricted to neuronal processes.

Quantification of the volume of positive stain revealed that rAAV9, compared to rAAV5, showed a 5 fold significant increase in the volume of distribution in the right (ipsilateral) hippocampus with the left (contralateral) hippocampus showing an approximate 10 fold increase in the volume of distribution (Figure 3, panel G). While rAAV serotype 8 was able to transduce a significantly greater volume than rAAV5 on the ipsilateral side (4.5 fold), it was not as efficient as rAAV9 on the contralateral side (Figure 3, panel G). rAAV9 showed ~5 fold greater staining than rAAV8 in the contralateral hippocampus.

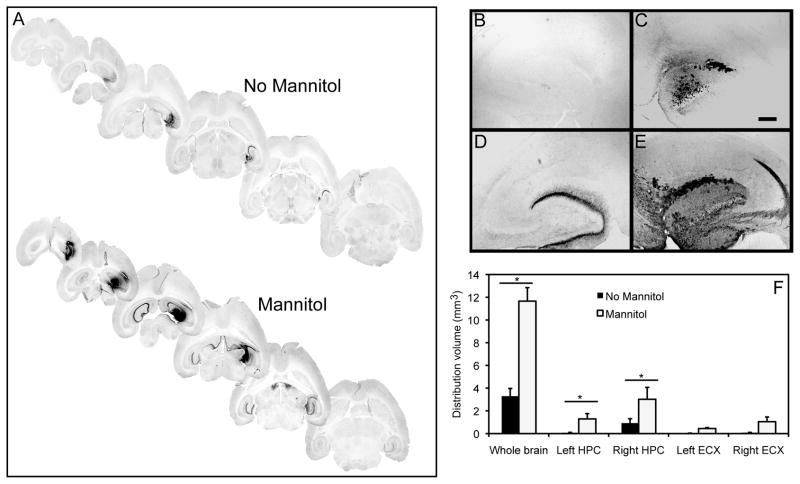

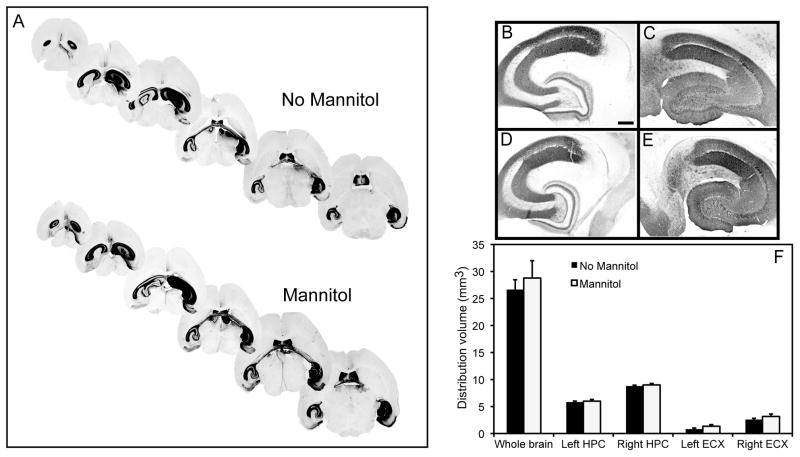

GFP expression with mannitol injection

Finally, we analyzed whether the osmotic agent, mannitol, could improve total area of distribution, thus enhancing transduction efficiencies of the different rAAV serotypes in conjunction with the CED method. rAAV serotypes 5 and 9, with low and high transducing capacity respectively, were given via direct intracranial injection using the CED method to 11-month-old mice with or without systemic pretreatment of mannitol. Animals receiving a systemic injection of 25% mannitol followed by CED administration into the right hippocampus of rAAV5 showed significantly greater volume of GFP expression 6 weeks post injection compared to animals only receiving rAAV5 administration alone (Fig. 4A). GFP expression in animals receiving systemic mannitol was observed throughout the entire right hippocampal region and was also observed in the left (contralateral) hippocampus. All brain slices throughout the hippocampus showed positive GFP staining in the mannitol-treated group. Animals that did not receive mannitol lacked staining in the most ventral and dorsal portions of the hippocampus (Fig. 4A). A 3-fold increase in the volume of positive GFP stain in the right hippocampus was observed compared to animals that did not receive mannitol (Fig. 4B–F). In the contralateral hemisphere we observed a 2 fold significant increase in GFP expression in mannitol treated animals compared to animals without mannitol pretreatment (Fig. 4B–F). A comparison of the staining present in the whole brain slices showed a 3.5 fold increase in volume of GFP expression (Fig. 4F).

FIG. 4.

GFP expression is increased following administration of rAAV5 using CED and systemic mannitol. Panel (A) shows stained sections from mannitol treated or untreated mice. Panels (B) and (C) show the left and right hippocampus respectively of a mouse injected with rAAV5 but no mannitol treatment. Panels (D) and (E) show the left and right hippocampus respectively of a mouse injected with rAAV5 and treated with mannitol. Panel (F) shows quantification of the volume of positive stain for anti-GFP immunohistochemistry. Hippocampus (HPC), entorhinal cortex (ECX) and whole brain (entire brain slice analyzed) are graphed. The asterisk (*) indicates significance with a p-value < 0.05. Scale = 120 μm.

All animals receiving rAAV9 administered using CED with or without systemic mannitol showed much higher GFP expression than animals receiving rAAV5. In our comparison between animals receiving rAAV9 with systemic mannitol pretreatment (Fig. 5A, E–F) and those that did not receive mannitol (Fig. 5A–C), we observed no significant differences in GFP expression in either the ipsilateral or the contralateral hippocampus (Fig. 5H). GFP expression in the ipsilateral hemisphere in both untreated and mannitol treated groups was widespread (Fig 5C, F) with cell bodies and axonal projections, including the perforant pathway and mossy fibers intensely stained revealing a significant amount of GFP expression. Also, GFP positive neurons were observed in the subiculum and entorhinal cortex which complete the hippocampal circuit (Fig. 5C, D, F, G). In the contralateral hippocampus a few cells in the hilus were positive for GFP expression, but most staining was observed in mossy fibers as well as axonal projections of CA regions presumably of those originating in the right hippocampus. GFP positive neurons were also observed in the right thalamic nuclei, which receives input from the subiculum of the hippocampus. Intense staining was observed in white matter tracts of the corpus collusum, which connect the right and left hemispheres, as well as in the hippocampal commissure or commissure of fornix adjoining the right and left hippocampus. Neurons positive for GFP expression were also observed in the anterior cortex, striatum, lateral and dorsal septal nuclei, superior colliculus, and cerebellum of the ipsilateral hemisphere in both groups receiving rAAV9 whether or not they received mannitol pretreatment.

FIG. 5.

GFP expression is increased following administration of rAAV9 using CED and systemic mannitol. Panel (A) shows stained sections from mannitol treated or untreated mice. Panels (B) and (C) show the left and right hippocampus respectively of a mouse injected with rAAV9 but no mannitol treatment. Panels (E) and (F) show the left and right hippocampus respectively of a mouse injected with rAAV9 and treated with mannitol. Panels (D) and (G) show the right entorhinal cortex of a mouse injected with rAAV9 not treated and treated with mannitol, respectively. Panel (H) shows quantification of the volume of positive stain for GFP. Hippocampus (HPC), entorhinal cortex (ECX) and whole brain (entire brain slice analyzed) are graphed. Scale = 120 μm (panels B–G).

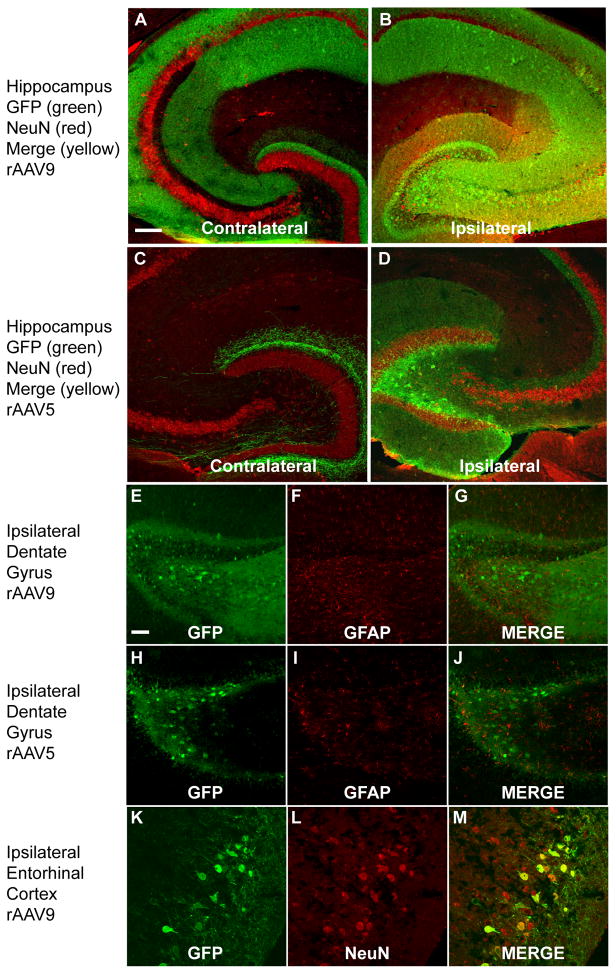

To further characterize vector serotype tropism and whether tropism and transduction efficiency of rAAV5 and rAAV9 were modified by mannitol, the tissue was double labeled using fluorescent immunostaining. GFP labeled cells co-localized with Neu-N positive staining in the ipsilateral hippocampus and entorhinal cortex (Fig. 6, panels B, D, K–M) as expected from previous publications (Cearley and Wolfe, 2007, 2006). Positive labeling in the contralateral hemisphere was in a few cells in the hilus of the DG but the majority of positive labeling was in the axons surrounding the cell bodies (Fig. 6, panel A, C). There was no significantly detectable co-localization of astrocytes (GFAP immunostaining) and GFP positive labeling in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (or in any other regions in the brain) (Fig. 6E–J). This was noted in all animals receiving either serotype with or without mannitol pretreatment. This is consistent with no change in tropism with the use of mannitol.

FIG. 6.

Transduction efficiency and GFP expression in cell types following rAAV5 and rAAV9 administration into hippocampus. Panels (A) and (B) show the contralateral and ipsilateral hippocampus respectively of a mouse injected with rAAV9 and treated with mannitol. Red indicates Neu-N staining, green shows GFP fluorescence and yellow shows colocalization. Panels (C) and (D) show the contralateral and ipsilateral hippocampus respectively of a mouse injected with rAAV5 and treated with mannitol (staining as above panels). Panels (E–G) and (H–J) show no co-localization of astrocytic staining (GFAP) (panels F and I) and GFP fluorescence (panels E and H) in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus for rAAV9 and rAAV5 respectively. Panels (K–M) show GFP fluorescence and Neu-N co-staining in the ipsilateral entorhinal cortex. The scale bar represents 120 μm in panels A–D and 50 μm in panels E–P.

DISCUSSION

Human trials have been initiated utilizing rAAV2 vectors for the treatment of human diseases such as cystic fibrosis, α-1 anti-trypsin deficiency, Parkinson’s disease, Batten’s disease, muscular dystrophy, hemophilia B. Unfortunately, one major disadvantage of using rAAV2 in the treatment of neurological disorders within large brain regions of humans, such as the cortex, is its limited distribution following intracranial injection (Cearley and Wolfe, 2007).

Therefore, our goal here was to determine whether recent approaches to improve rAAV distribution within the brain parenchyma could act additively when combined. To achieve this we examined three parameters to improve transgene expression levels; convection enhanced delivery (CED), systemic mannitol pre-treatment and optimization of rAAV serotype. We indeed found that mannitol pre-treatment coupled with CED of rAAV9 led to robust distribution and expression of GFP throughout the hippocampi of injected mice. Impressively, rAAV9 dispersed across the hippocampal commissures to the contralateral hippocampi as well. Moreover, only rAAV9 administered by CED led to transduction in multiple regions outside the hippocampus in both hemispheres. Thus, for the first time, we were able to deliver rAAV gene product to a large portion of the entire brain using a single injection in adult mice. Therefore it is reasonable to assume that using 4–6 injection sites using the rAAV9/CED/mannitol approach could produce high levels of transduction throughout the entire brain.

The recent identification and cloning (for recombinant virus production) of different AAV serotypes has advanced the study of rAAV vectors in the field of gene therapy (Gao et al., 2004; Gao et al., 2005). There are currently a number of studies aimed at characterizing these different serotypes with respect to transduction efficiency, tissue tropism, cell surface receptors, intracellular processing, and capsid structure. AAV2 serotype was the first to be cloned into bacterial plasmids by Samulski et al. in 1982 (Samulski et al., 1982). AAV5 was originally discovered in a penile flat condylomatous lesion in 1984. Although it contained terminal repeat structures similar to those of AAV2, it is the most divergent of the serotypes (Bantel Schaal and zur Hausen, 1984; Choi et al., 2005). AAV8 was originally isolated from rhesus monkey tissue in 2002 by Gao and colleagues (Gao et al., 2002). AAV9, like AAV5, was originally discovered in human tissue, while AAV10 and AAV11 the most recently identified serotypes, were initially isolated from cynomolgus monkey tissue in 2004 by Mori et. al., and to date have not been fully characterized (Mori et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2006a).

Several recent studies have shown that different serotypes have distinct variations in their transduction efficiencies depending on the specific cell or tissue type, yet the molecular mechanisms which determine the preferred target cell tropism for many serotypes remains unknown. Despite what is currently known concerning different rAAV transduction profiles, the data regarding rAAV serotype specific tissue tropism is possibly confounded by variations in vector titer, promoters, and transgenes between studies. In the CNS, serotype characterization studies have revealed that rAAV1, and 5 have higher transduction efficiencies than rAAV2 throughout all the regions and cell types of the CNS (Alisky et al., 2000); (Burger et al., 2004; Burger et al., 2005). However, rAAV4 will efficiently transduce specific cell types such as astrocytes within the subventricular zone (Davidson et al., 2000; Weber et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2006b). Studies by Wolfe and colleagues also reveal that rAAV7, 8, 9 and 10 expressing cDNA for lysosomal enzyme are also capable of transducing neurons within specific regions in the mouse brain. rAAV9 and rAAV10 appeared to have the highest transduction efficiencies and were found to undergo vector genome transport through axonal transport pathways (Cearley and Wolfe, 2007, 2006).

Before the initiation of this study, rAAV5 and rAAV1 vectors were shown to transduce more neurons in the CNS than the commonly used rAAV2 (Burger et al., 2004). Therefore, we chose to study rAAV5 serotype with the CED method. CED has been shown to increase the area of distribution of material in the brain parenchyma in murine, canine, nonhuman primate as well as in humans (Bankiewicz et al., 2000; Cunningham et al., 2000; Dickinson et al., 2008; Fiandaca et al., 2008; Krauze et al., 2005a; Szerlip et al., 2007). In the present study, we successfully increased gene expression and the area of distribution, especially in regions distal to the injection site, by combining the CED method with the step cannula design. However, since the availability and more recent publications of other serotypes, such as 8 and 9, which also efficiently transduce neurons in the murine CNS (Klein et al., 2006; Klein et al., 2008; Taymans et al., 2007), we examined the use of rAAV8 and rAAV9 serotypes with the CED injection method.

Following a single CED intracranial injection, we successfully demonstrated that rAAV9 was the most efficient serotype in transducing a larger number of neurons in a larger area of the brain than either rAAV5 or rAAV8. rAAV8 was only slightly less efficient than rAAV9 and much more efficient that rAAV5 at transducing neurons in the mouse CNS. Our data are consistent with others who have also shown that both rAAV8 and 9 can more efficiently transduce a larger region of brain than rAAV5 in murine models (Cearley and Wolfe, 2006). rAAV9 not only provides superior transduction compared to serotypes 5 and 8 in the CNS, but also results in global transduction of several cell and tissue types in peripheral organs such as heart, liver and lung, when systemically injected (Bish et al., 2008; Zincarelli et al., 2008). Furthermore, studies have clearly shown rAAV8 to have significantly superior transduction efficiency than rAAV2 or 5 in murine and nonhuman primate animal models. That is also consistent with our data showing serotype 8 to be more efficient at transducing neurons in the mouse CNS than serotype 5 (Davidoff et al., 2005).

The differences in transduction are most likely mediated by the cell surface receptor binding of the AAV capsid proteins, as well as co-receptors and the expression patterns of these receptors in the mouse CNS. Different serotypes have been shown to use different cell surface receptors for viral entry. For example, AAV2 uses heparin sulfate proteoglycan, αVβ5 integrin and fibroblast growth factor receptor (Qing et al., 2003; Summerford et al., 1999; Summerford and Samulski, 1998). AAV5 interacts with the sialic acid receptors and platelet derived growth factor receptor (Akache et al., 2006; Kaludov et al., 2003; Walters et al., 2001; Zabner et al., 2000). Akache et al. (2006) have demonstrated that AAV8 and 9 use the 37/67 kD laminin receptor (Akache et al., 2006). Other factors that may contribute to the higher levels of expression for rAAV8 and 9 include viral uptake through endocytosis, intracellular trafficking and translocation of the particle to the nucleus, virion uncoating, and synthesis of double stranded DNA.

The final parameter that we examined was the use of mannitol to induce hyperosmolarity, thereby reducing intracranial pressure and facilitating the movement of particles through the interstitial space. Previously, mannitol was shown to increase the distribution of rAAV2 within the striatum of the rat brain (Burger, 2004; Fu et al., 2003). Therefore, we wanted to examine the effect of mannitol administration with the more efficient rAAV serotypes in combination with the more efficient CED injection method. We first demonstrated that mannitol could significantly increase the volume of distribution of rAAV5 after a single CED administration into the DG of the right hippocampus (Fig. 4). This distribution was evident throughout the entire ipsilateral hemisphere allowing viral particles to travel throughout the injected hippocampus as well as other areas adjacent to the injection site such as the entorhinal cortex and thalamus (although the expression was limited to a few cells in these regions). In addition, a significant amount of GFP gene expression was noted in the contralateral hemisphere most likely due to axonal transport via commissural fibers that was not as apparent without mannitol pretreatment. Axonal transport has previously been observed for rAAV including rAAV5 (Burger et al., 2004). The axonal transport observed by Burger et al. (2004) was without the use of mannitol pretreatment, and was most likely due to the higher titer of virus used in that study (~1 × 1013 vg/mL compared to ~1 × 1011 vg/mL used in this study). The use of the lower titer in this study dramatically demonstrates the effectiveness of the mannitol in increasing transduction efficiency of the rAAV5.

We also examined the rAAV9 vector expression in conjunction with the mannitol injection. Interestingly, we did not observe significant changes in the level of GFP expression in the injected or contralateral hippocampus for the rAAV9. This is possibly due to a ceiling in the amount of GFP overexpression possibly due to the preexisting high transduction efficiency of rAAV9 with the CED injection procedure. However, the mannitol did modestly increase rAAV9-driven GFP gene expression at sites distal to the injection site, the entorhinal cortex and thalamus (Fig. 5). The use of mannitol did not have any effect on viral tropism regarding neurons versus glia (Fig. 6). As previously observed the rAAV used in these study predominantly infected neurons (Burger et al., 2004; Cearley and Wolfe, 2007, 2006). GFP labeling in the contralateral hemisphere was in a few cells in the hilus of the DG (retrograde labeling), but the majority of positive labeling was in the axons surrounding the cell bodies (anterograde labeling of commissural fibers). Further, there was very little co-labeling of the astrocyte marker GFAP with GFP, indicating little tropism toward astrocytes.

Optimization of administration techniques such as those described here should enhance the development of rAAV as a gene delivery tool for the treatment of a variety of neurological diseases. The advancement in AAV vectors has been made possible by the isolation of several naturally occurring AAV serotypes 1–11, but more recently over 100 AAV capsid sequence variants from different animal species have been identified. These isolates are ideally suited for development into human gene therapy vectors due to their varied tissue tropisms. Advances in the study of mutated capsids, chimeric capsids and modified capsids (such as the addition of single chain antibodies) may further contribute to differences in viral tropism (Bowles et al., 2003; Kruger et al., 2008; Rabinowitz and Samulski, 2000; Wu et al., 2006a; Xiao et al., 1999). Through such modifications of the rAAV combined with cell specific promoters, it may be possible to uniquely tailor a vector allowing transduction of specific cell/tissue types, and increased potential for use as a successful gene therapy technique.

Acknowledgments

Supported by The Johnnie Byrd Center for Alzheimer’s Research, NIH grants AG-25509, AG 15490, and AG 04418

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCE LIST

- Akache B, Grimm D, Pandey K, Yant SR, Xu H, Kay MA. The 37/67-kilodalton laminin receptor is a receptor for adeno-associated virus serotypes 8, 2, 3, and 9. J Virol. 2006;80:9831–6. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00878-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alisky JM, Hughes SM, Sauter SL, Jolly D, Dubensky TW, Jr, Staber PD, Chiorini JA, Davidson BL. Transduction of murine cerebellar neurons with recombinant FIV and AAV5 vectors. Neuroreport. 2000;11:2669–73. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200008210-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankiewicz KS, Eberling JL, Kohutnicka M, Jagust W, Pivirotto P, Bringas J, Cunningham J, Budinger TF, Harvey-White J. Convection-enhanced delivery of AAV vector in parkinsonian monkeys; in vivo detection of gene expression and restoration of dopaminergic function using pro-drug approach. Exp Neurol. 2000;164:2–14. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantel Schaal U, zur Hausen H. Characterization of the DNA of a defective human parvovirus isolated from a genital site. Virology. 1984;134:52–63. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90271-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bish LT, Morine K, Sleeper MM, Sanmiguel J, Wu D, Gao G, Wilson JM, Sweeney HL. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotype 9 provides global cardiac gene transfer superior to AAV1, AAV6, AAV7, and AAV8 in the mouse and rat. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:1359–68. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles DE, Rabinowitz JE, Samulski RJ. Marker rescue of adeno-associated virus (AAV) capsid mutants: a novel approach for chimeric AAV production. J Virol. 2003;77:423–32. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.423-432.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger C, Gorbakyuk O, Velardo MJ, Peden C, Williams P, Zolotukhin S, Reier PJ, Mandel RJ, Muzyczka N. Recombinant AAV viral vectors pseudotyped with viral capsids from serotypes 1, 2, and 5 display differential efficiency and cell tropism after delivery to different regions of the central nervous system. Mol Ther. 2004;10:302–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger C, Nash K, Mandel RJ. Recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors in the nervous system. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:781–91. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger C, Nguyen F, Deng J, Mandel RJ. Systemic mannitol-induced hyperosmolality amplifies rAAV2 mediated striatal transduction to a greater extent than local co-infusion. Exp Neurol. 2004 doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.031. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cearley CN, Wolfe JH. A single injection of an adeno-associated virus vector into nuclei with divergent connections results in widespread vector distribution in the brain and global correction of a neurogenetic disease. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9928–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2185-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cearley CN, Wolfe JH. Transduction characteristics of adeno-associated virus vectors expressing cap serotypes 7, 8, 9, and Rh10 in the mouse brain. Mol Ther. 2006;13:528–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi VW, McCarty DM, Samulski RJ. AAV hybrid serotypes: improved vectors for gene delivery. Curr Gene Ther. 2005;5:299–310. doi: 10.2174/1566523054064968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J, Oiwa Y, Nagy D, Podsakoff G, Colosi P, Bankiewicz KS. Distribution of AAV-TK following intracranial convection-enhanced delivery into rats. Cell Transplant. 2000;9:585–94. doi: 10.1177/096368970000900504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff AM, Gray JT, Ng CY, Zhang Y, Zhou J, Spence Y, Bakar Y, Nathwani AC. Comparison of the ability of adeno-associated viral vectors pseudotyped with serotype 2, 5, and 8 capsid proteins to mediate efficient transduction of the liver in murine and nonhuman primate models. Mol Ther. 2005;11:875–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson BL, Stein CS, Heth JA, Martins I, Kotin RM, Derksen TA, Zabner J, Ghodsi A, Chiorini JA. Recombinant adeno-associated virus type 2, 4, and 5 vectors: Transduction of variant cell types and regions in the mammalian central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000 doi: 10.1073/pnas.050581197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daya S, Berns KI. Gene therapy using adeno-associated virus vectors. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:583–93. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00008-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson PJ, LeCouteur RA, Higgins RJ, Bringas JR, Roberts B, Larson RF, Yamashita Y, Krauze M, Noble CO, Drummond D, Kirpotin DB, Park JW, Berger MS, Bankiewicz KS. Canine model of convection-enhanced delivery of liposomes containing CPT-11 monitored with real-time magnetic resonance imaging: laboratory investigation. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:989–98. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/5/0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiandaca MS, Forsayeth JR, Dickinson PJ, Bankiewicz KS. Image-guided convection-enhanced delivery platform in the treatment of neurological diseases. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5:123–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.10.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Muenzer J, Samulski RJ, Breese G, Sifford J, Zeng X, McCarty DM. Self-complementary adeno-associated virus serotype 2 vector: global distribution and broad dispersion of AAV-mediated transgene expression in mouse brain. Mol Ther. 2003;8:911–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G, Vandenberghe LH, Alvira MR, Lu Y, Calcedo R, Zhou X, Wilson JM. Clades of Adeno-associated viruses are widely disseminated in human tissues. J Virol. 2004;78:6381–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6381-6388.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G, Vandenberghe LH, Wilson JM. New recombinant serotypes of AAV vectors. Curr Gene Ther. 2005;5:285–97. doi: 10.2174/1566523054065057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MN, Holcomb LA, Jantzen PT, DiCarlo G, Wilcock D, Boyett KW, Connor K, Melachrino J, O’Callaghan JP, Morgan D. Time course of the development of Alzheimer-like pathology in the doubly transgenic PS1+APP mouse. Exp Neurol. 2002;173:183–95. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadaczek P, Kohutnicka M, Krauze MT, Bringas J, Pivirotto P, Cunningham J, Bankiewicz K. Convection-enhanced delivery of adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) into the striatum and transport of AAV2 within monkey brain. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:291–302. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaludov N, Padron E, Govindasamy L, McKenna R, Chiorini JA, Agbandje-McKenna M. Production, purification and preliminary X-ray crystallographic studies of adeno-associated virus serotype 4. Virology. 2003;306:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(02)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RL, Dayton RD, Leidenheimer NJ, Jansen K, Golde TE, Zweig RM. Efficient neuronal gene transfer with AAV8 leads to neurotoxic levels of tau or green fluorescent proteins. Mol Ther. 2006;13:517–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RL, Dayton RD, Tatom JB, Henderson KM, Henning PP. AAV8, 9, Rh10, Rh43 vector gene transfer in the rat brain: effects of serotype, promoter and purification method. Mol Ther. 2008;16:89–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauze MT, McKnight TR, Yamashita Y, Bringas J, Noble CO, Saito R, Geletneky K, Forsayeth J, Berger MS, Jackson P, Park JW, Bankiewicz KS. Real-time visualization and characterization of liposomal delivery into the monkey brain by magnetic resonance imaging. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 2005a;16:20–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresprot.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauze MT, Saito R, Noble C, Tamas M, Bringas J, Park JW, Berger MS, Bankiewicz K. Reflux-free cannula for convection-enhanced high-speed delivery of therapeutic agents. J Neurosurg. 2005b;103:923–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.5.0923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger L, Eskerski H, Dinsart C, Cornelis J, Rommelaere J, Haberkorn U, Kleinschmidt JA. Augmented transgene expression in transformed cells using a parvoviral hybrid vector. Cancer Gene Ther. 2008;15:252–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7701113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levites Y, Jansen K, Smithson LA, Dakin R, Holloway VM, Das P, Golde TE. Intracranial adeno-associated virus-mediated delivery of anti-pan amyloid beta, amyloid beta40, and amyloid beta42 single-chain variable fragments attenuates plaque pathology in amyloid precursor protein mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11923–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2795-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Takeuchi T, Enomoto Y, Kondo K, Sato K, Ono F, Iwata N, Sata T, Kanda T. Biodistribution of a low dose of intravenously administered AAV-2, 10, and 11 vectors to cynomolgus monkeys. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2006;59:285–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon LL, Nilaver G, Kroll RA, Pagel MA, Breakefield XO, Chiocca EA, Davidson BL, Weissleder R, Neuwelt EA. Comparison of intracerebral inoculation and osmotic blood-brain barrier disruption for delivery of adenovirus, herpesvirus, and iron oxide particles to normal rat brain. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:1840–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilaver G, Muldoon LL, Kroll RA, Pagel MA, Breakefield XO, Davidson BL, Neuwelt EA. Delivery of herpesvirus and adenovirus to nude rat intracerebral tumors after osmotic blood-brain barrier disruption. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9829–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qing K, Li W, Zhong L, Tan M, Hansen J, Weigel-Kelley KA, Chen L, Yoder MC, Srivastava A. Adeno-associated virus type 2-mediated gene transfer: role of cellular T-cell protein tyrosine phosphatase in transgene expression in established cell lines in vitro and transgenic mice in vivo. J Virol. 2003;77:2741–6. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.4.2741-2746.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz JE, Samulski RJ. Building a better vector: the manipulation of AAV virions. Virology. 2000;278:301–8. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan R, Brady ML, Rodriguez-Ponce MI, Hartlep A, Pedain C, Sampson JH. Convection-enhanced delivery of therapeutics for brain disease, and its optimization. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20:E12. doi: 10.3171/foc.2006.20.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport SI. Advances in osmotic opening of the blood-brain barrier to enhance CNS chemotherapy. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;10:1809–18. doi: 10.1517/13543784.10.10.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samulski RJ, Berns KI, Tan M, Muzyczka N. Cloning of adeno-associated virus into pBR322: rescue of intact virus from the recombinant plasmid in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:2077–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmued LC, Albertson C, Slikker W., Jr Fluoro-Jade: a novel fluorochrome for the sensitive and reliable histochemical localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res. 1997;751:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01387-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerford C, Bartlett JS, Samulski RJ. AlphaVbeta5 integrin: a co-receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. Nat Med. 1999;5:78–82. doi: 10.1038/4768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerford C, Samulski RJ. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J Virol. 1998;72:1438–45. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1438-1445.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szerlip NJ, Walbridge S, Yang L, Morrison PF, Degen JW, Jarrell ST, Kouri J, Kerr PB, Kotin R, Oldfield EH, Lonser RR. Real-time imaging of convection-enhanced delivery of viruses and virus-sized particles. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:560–7. doi: 10.3171/JNS-07/09/0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taymans JM, Vandenberghe LH, Haute CV, Thiry I, Deroose CM, Mortelmans L, Wilson JM, Debyser Z, Baekelandt V. Comparative analysis of adeno-associated viral vector serotypes 1, 2, 5, 7, and 8 in mouse brain. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:195–206. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters RW, Yi SM, Keshavjee S, Brown KE, Welsh MJ, Chiorini JA, Zabner J. Binding of adeno-associated virus type 5 to 2,3-linked sialic acid is required for gene transfer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20610–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber M, Rabinowitz J, Provost N, Conrath H, Folliot S, Briot D, Cherel Y, Chenuaud P, Samulski J, Moullier P, Rolling F. Recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 4 mediates unique and exclusive long-term transduction of retinal pigmented epithelium in rat, dog, and nonhuman primate after subretinal delivery. Mol Ther. 2003;7:774–81. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Asokan A, Samulski RJ. Adeno-associated virus serotypes: vector toolkit for human gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2006a;14:316–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Miller E, Agbandje-McKenna M, Samulski RJ. Alpha2,3 and alpha2,6 N-linked sialic acids facilitate efficient binding and transduction by adeno-associated virus types 1 and 6. J Virol. 2006b;80:9093–103. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00895-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W, Chirmule N, Berta SC, McCullough B, Gao G, Wilson JM. Gene therapy vectors based on adeno-associated virus type 1. J Virol. 1999;73:3994–4003. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3994-4003.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabner J, Seiler M, Walters R, Kotin RM, Fulgeras W, Davidson BL, Chiorini JA. Adeno-associated virus type 5 (AAV5) but not AAV2 binds to the apical surfaces of airway epithelia and facilitates gene transfer [In Process Citation] J Virol. 2000;74:3852–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3852-3858.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zincarelli C, Soltys S, Rengo G, Rabinowitz JE. Analysis of AAV serotypes 1–9 mediated gene expression and tropism in mice after systemic injection. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1073–80. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]