Abstract

Increasing evidence supports a crucial role for glial metabolism in maintaining proper synaptic function and in the etiology of neurological disease. However, the study of glial metabolism in humans has been hampered by the lack of noninvasive methods. To specifically measure the contribution of astroglia to brain energy metabolism in humans, we used a novel noninvasive nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopic approach. We measured carbon 13 incorporation into brain glutamate and glutamine in eight volunteers during an intravenous infusion of [2-13C] acetate, which has been shown in animal models to be metabolized specifically in astroglia. Mathematical modeling of the three established pathways for neurotransmitter glutamate repletion indicates that the glutamate/glutamine neurotransmitter cycle between astroglia and neurons (0.32 ± 0.07 μmol · gm−1 · min−1) is the major pathway for neuronal glutamate repletion and that the astroglial TCA cycle flux (0.14 ± 0.06 μmol · gm−1 · min−1) accounts for ∼14% of brain oxygen consumption. Up to 30% of the glutamine transferred to the neurons by the cycle may derive from replacement of oxidized glutamate by anaplerosis. The further application of this approach could potentially enlighten the role of astroglia in supporting brain glutamatergic activity and in neurological and psychiatric disease.

Keywords: human, brain, astrocyte, glutamate/glutamine cycle, TCA cycle, NMR, acetate

Recent studies have established the crucial role of glial metabolism for brain function. Astrocytes have been shown to be the major pathway of uptake of the released neurotransmitter glutamate (Waniewski and Martin, 1986; Rothstein et al., 1996). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies have shown that the uptake of glutamate by the astrocyte and the return to the neuron as glutamine, a pathway referred to as the glutamate/glutamine (Glu/Gln) cycle, is a major metabolic pathway in cerebral cortex (Gruetter et al., 1998; Sibson et al., 1998; Shen et al., 1999). The rate of the glutamatine/glutamate cycle has been shown to increase with close to a 1:1 slope with neuronal glucose oxidation with increasing neuronal activity (Sibson et al., 1998). It has also been proposed that astroglial glycolysis may account for the majority of brain glucose uptake used to fuel functional neuroenergetics through stoichiometric coupling of astroglial glutamate uptake and conversion to glutamine (Magistretti et al., 1999). Together, these findings suggest a redefining of brain glutamate neurotransmitter release and recycling as a series of metabolic interactions between glial cells and neurons.

Both 13C and1H{13C} NMR allows for noninvasive measurement of metabolic fluxes in human brain based on the detection of label incorporation into the large cerebral pools of glutamate and glutamine (Rothman et al., 1992;Gruetter et al., 1998; Shen et al., 1999; Bluml et al. 2001). Previous studies have derived metabolic rates from infused [1-13C] glucose. However because glucose is metabolized in both neurons and glia, this approach requires assumptions to separately determine metabolic flows in these two different cell populations. These assumptions, based on animal models and cellular studies, may not hold in the human brain under all conditions.

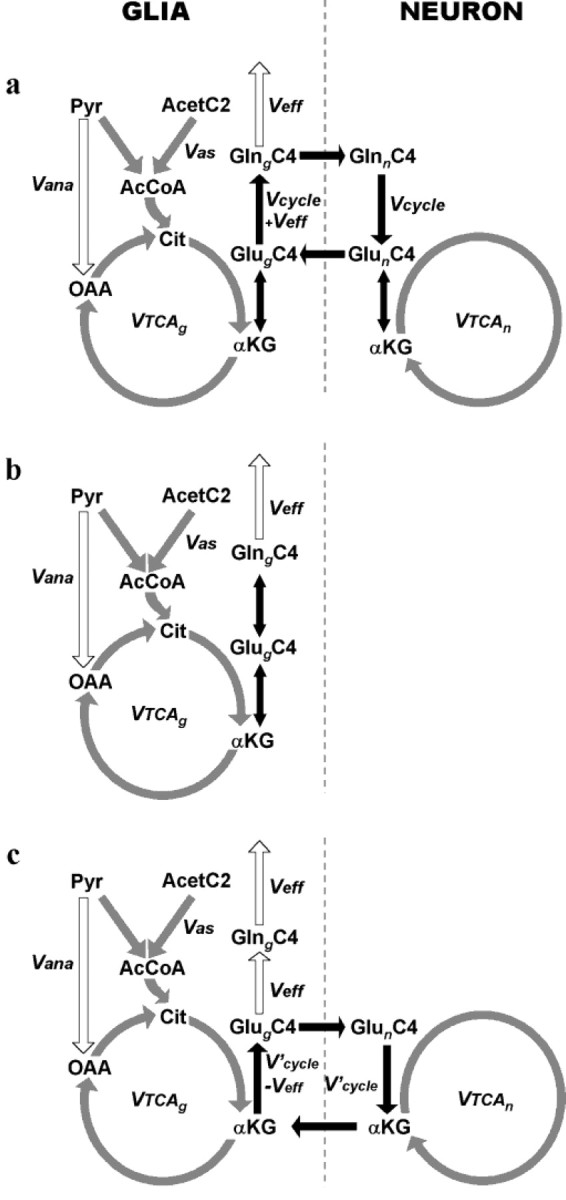

Neuronal and glial metabolism may be more directly distinguished using acetate as a substrate, which, because of far greater transport activity, is almost exclusively metabolized in astrocytes (Waniewski and Martin, 1998), as has been validated in vivo(Badar-Goffer et al., 1990; Hassel et al., 1995). This strategy has been used in in vitro13C NMR studies of animals (Kunnecke and Cerdan, 1989; Cerdan et al., 1990;Hassel et al., 1995). In this study, we used [2-13C]-labeled acetate to selectively measure the contribution of astroglial oxidative metabolism to total substrate oxidation and the rate of total glial/neuronal glutamate trafficking in human brain by 13C NMR spectroscopy. Two models to describe neuronal/astroglial substrate trafficking for repletion of neuronal glutamate were tested along with the possibility of internal label exchange (see Fig. 1). Estimates were made of glutamate oxidation and pyruvate recycling. Our results indicate that astroglia contributes ∼15% of the total oxidative metabolism and that the glutamate/glutamine cycle is the major source of neuronal glutamate repletion, with up to 30% of this flux contributed by anaplerosis replacing oxidized glutamate. The further application of this approach could potentially enlighten the role of astroglia in supporting brain glutamatergic activity and in neurological and psychiatric disease.

Fig. 1.

Incorporation of label from [2-13C] acetate into the brain glutamate and glutamine pools. Different models of neuronal glutamate replenishment are presented: glutamate/glutamine cycle model (a), internal exchange model (b), and glutamate/α-ketoglutarate cycle model (c). For the sake of clarity, the carbon position labeled only in the first TCA cycle turn (C4) is indicated.Acet, Acetate; Pyr, pyruvate;AcCoA, acetyl coenzyme A; Cit, citrate;OAA, oxaloacetate; αKG, α-ketoglutarate; Glu, glutamate; Gln, glutamine; Vas, flux through the acetyl coenzyme A synthetase; Vana, anaplerotic flux; Veff, glutamine efflux from the brain (Veff =Vana);Vcycle, Glu/Gln cycle flux;V′cycle, Glu/α-KG cycle flux;VTCAn, neuronal TCA cycle rate;VTCAg, glial TCA cycle rate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects. NMR studies were performed with eight healthy volunteers (four males and four females; aged 29 ± 6; mean ± SD) at rest after a 12 hr overnight fasting. Informed written consent was obtained from all subjects after the aims and potential risks were explained to them. The protocol was approved by the Yale University School of Medicine Human Investigation Committee.

NMR acquisition. NMR data were acquired on a 2.1 T whole body (1 m bore) magnet connected to a modified Bruker AVANCE spectrometer (Bruker Instruments, Billerica, MA). Subjects remained supine in the magnet with the head lying on top of a home-built radio-frequency NMR probe, consisting of one13C circular coil (8.5 cm diameter) and two 1H quadrature coils for1H acquisitions and decoupling. After tuning, acquisition of scout images, shimming with the FASTERMAP procedure (Shen et al., 1997), and calibration of the decoupling power,13C NMR spectra were acquired for 10 min before and during a 160 min [2-13C] acetate infusion (350 mol/l sodium salt, 99%13C enriched; Isotec, Miamisburg, OH) at an infusion rate of 3 mg · kg−1 · min−1. NMR spectra were acquired using an ISIS localized adiabatic13C{1H} polarization transfer sequence optimized for detection of glutamate and glutamine in the C4 position (Shen et al., 1999). The spectroscopic voxel was located in the parietal-occipital lobe. Its size was adapted to each volunteer and was on average 96 ± 3 ml.

NMR data processing. Amplitudes of glutamate C4 and C3 (34.3 and 27.7 ppm, respectively) and glutamine C4 and C3 (31.7 and 27.1 ppm, respectively) were measured after Gaussian multiplication, Fourier transformation, and baseline subtraction.

Glutamate C4 fractional enrichment was derived from the NMR signal by comparison with the signal measured on a glutamate phantom under the same experimental conditions, assuming gray and white matter glutamate concentrations of 9 and 4.5 mm, respectively, based on previous magnetic resonance spectroscopy and biopsy studies (Michaelis et al., 1993; Gruetter et al., 1994). Glutamate C3 and glutamine C4 and C3 fractional enrichments were derived from NMR measurements using glutamate C4 as a reference, assuming gray and white matter glutamine concentrations of 4 and 2 mm, respectively, and using the gray/white matter distribution measured by segmentation magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Because of the minimal13C label incorporated into white matter, the calculated rates are influenced mainly by the concentration ratio of glutamate and glutamine assumed for gray matter.

Measurement of gray/white matter distribution by segmentation MRI. The gray and white matter content of a 96 ml voxel located in an identical position to the spectroscopic voxel in the parietal-occipital lobe were determined by segmentation MRI in eight healthy volunteers on the same NMR system (G. F. Mason, personal communication). Sets of B1 maps and inversion-recovery images were acquired and processed to yield quantitative images of T1, which were converted to segmented images of gray matter, white matter, and CSF. The gray matter volume was 57 ± 5% of tissue content in the voxel (mean ± SD).

Blood sample processing. Fractional enrichments and plasma acetate concentrations were measured from blood samples collected at 10 min intervals and analyzed on a Hewlett-Packard (Palo Alto, CA) 5890 gas chromatograph (HP-1 capillary column; 12 × 0.2 × 0.33 mm film thickness) interfaced to a Hewlett-Packard 5971A mass selective detector operating in the electron impact ionization mode.

Glucose fractional enrichment was measured from the blood samples collected at the end of the studies. Total fractional enrichment was determined by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. The distribution of 13C label among the six glucose carbon atoms was then determined by high-resolution NMR using a 500 MHz vertical-bore spectrometer (Bruker Instruments).

Absence of contribution from hepatic metabolism of acetate.The liver is known to metabolize acetate so that some of the13C label is incorporated into glucose by gluconeogenesis (Schumann et al., 1991). Contribution of [2-13C] acetate to liver gluconeogenesis leads to the release of glucose labeled in the C1, C2, C5, and C6 positions. Glucose being the main substrate of brain metabolism and glucose C1 and C6 being incorporated in the TCA cycle the same way as acetate C2, the contribution of13C-labeled glucose could alter our measurements. Therefore, the fractional enrichment of plasma glucose at steady state was measured for each carbon atom position. Fractional enrichments over natural abundance were found to be 1.2 ± 0.2% for C1, 1.1 ± 0.2% for C2, 0.0 ± 0.1% for C3, 0.5 ± 0.2% for C4, 1.7 ± 0.3% for C5, and 1.3 ± 0.2% for C6. In comparison, steady-state fractional enrichment of [2-13C] acetate was 87.7 ± 4.1%. Based on previous human studies using [1-13C] glucose, the contribution of13C glucose is within the margin of error of our measurements.

RESULTS

Metabolic models of neuronal/glial glutamate repletion tested

Radioisotope labeling experiments performed almost 40 years ago have suggested that cerebral metabolism is characterized by two distinct metabolic compartments (Berl et al., 1962; Van den Berg et al., 1969). The immunohistochemical localization of enzymes (Martinez-Hernandez et al., 1977; Yu et al., 1983) later led to the two metabolic compartments being associated primarily with neurons and glial cells. Over the last decade, two models of repletion of neuronal glutamate by astrocytes have been proposed (Fig.1). These models, which are described below, as well as the possibility of internal label exchange in the astroglia, were tested.

Model a: neuronal/astroglial glutamate/glutamine cycle

In the Glu/Gln cycle (Fig. 1a), neuronal glutamate is first released in the synaptic cleft, taken up by astrocytes, and converted to glutamine by the astrocyte-specific enzyme glutamine synthetase (Martinez-Hernandez et al., 1977). Glutamine is transported to the extracellular fluid in which it is taken up by neurons and converted back to glutamate by the enzyme phosphate-activated glutaminase (PAG) (Erecinska and Silver, 1990). In addition to glutamine synthesis arising from exogenous glutamate, a lesser amount is produced de novo through anaplerosis to remove excess ammonia derived from blood and/or brain metabolism (Sibson et al., 1997). Figure 1a illustrates the label incorporation from [2-13C] acetate into glial glutamate and glutamine expected to arise via the glutamate/glutamine cycle model of glutamate replenishment. [2-13C] acetate is converted into [2-13C] acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) in the glial compartment, which labels glial TCA cycle intermediates and, subsequently, glutamate and glutamine C4. The neuronal pool of glutamate C4 is subsequently labeled from glutamine C4. After the second turn of the glial TCA cycle, C2 and C3 of glutamate and glutamine become labeled.

Model b: astroglial internal glutamate/glutamine exchange

An alternative explanation for the high rate of glutamine labeling from [1-13C] glucose is that it reflects label exchange between glutamate and glutamine within astrocytes as opposed to glutamate and glutamine movements between neurons and astrocytes. Although there is no compelling evidence that a significant degree of label exchange occurs, we believe it is important to evaluate this possible explanation of the 13C labeling data from [1–13C] glucose attributable to the presence of enzymes, which can catalyze this exchange. Activities of enzymes capable of converting glutamine to glutamate (or α-ketoglutarate) exist in astrocytes, as well as neurons. In addition to PAG (Cooper and Plum, 1987; Hogstad et al., 1988), membrane-bound γ-glutamyl transferase (γ-glutamyl transpeptidase) and enzymes of the glutaminase II system (glutamine transaminase K/cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase plus ω-amidase) have been detected in astrocytes (Shine et al., 1981; Kvamme et al., 1985; Makar et al., 1994), although the function of the later may be related more to kynurenine metabolism than glutamine (Okuno et al., 1991;Alberati-Giani et al., 1995). Although glutamine formation from glutamate and ammonia as catalyzed by glutamine synthetase is essentially irreversible, isotopic exchange could potentially lead to label equilibration between them. Because of the glial compartmentation of the cycle, this model can be referred to as an internal exchange (Fig. 1b). In this model, neuronal glutamate repletion would be entirely through uptake by neuronal glutamate transporters.

Model c: neuronal/astroglial glutamate/α-ketoglutarate cycle

A third model for neuronal glutamate repletion is based on the potential participation of α-ketoglutarate (Shank and Campbell, 1984;Schousboe et al., 1997) in terms of a glutamate/α-ketoglutarate (Glu/α-KG) cycle between astrocytes and neurons. In this cycle (Fig. 1c), glutamate derived from neurons is converted to α-ketoglutarate (by oxidation or transamination) in astroglia, in which it is released and taken up by neurons for resynthesis of neurotransmitter glutamate.

Acetate and glucose are metabolized in distinct compartments in human brain

Shortly after the onset of [2-13C] acetate infusion, the fractional enrichment (FE) of plasma acetate reached steady state (FE of 83 ± 4% 10 min into the infusion; FE of 86 ± 2% at the end of infusion). Figure2a shows a13C NMR spectrum acquired in the parietal-occipital lobe of one volunteer at steady state, during the last 40 min of the [2-13C] acetate infusion. Glutamate and glutamine were significantly labeled in the C4, C3, and C2 positions, demonstrating that acetate is taken up and metabolized by brain at low plasma concentrations. The acetate concentrations achieved during the infusion (from 0.11 ± 0.06 to 0.61 ± 0.14 mm) were within the physiological range of plasma acetate levels observed in humans (Lundquist, 1962).

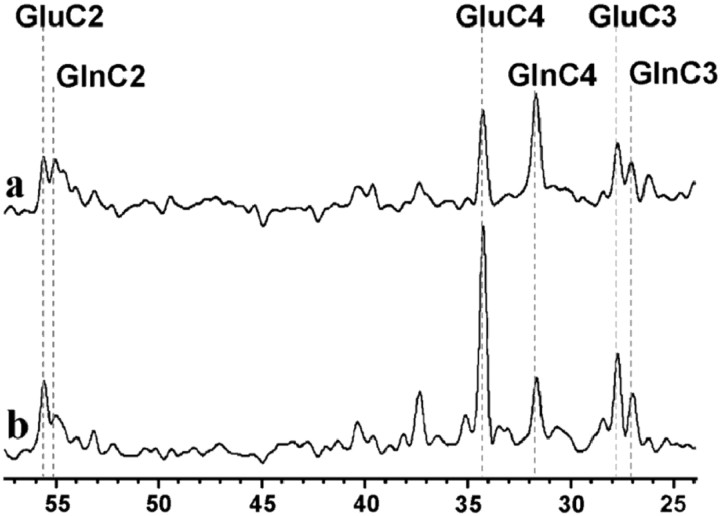

Fig. 2.

Steady-state 13C-NMR spectra obtained in the parietal-occipital cortex of a volunteer during the infusion of13C-labeled substrates. a, Spectrum acquired during an infusion of [2-13C] acetate. b, Spectrum obtained under identical experimental conditions during an infusion of [1-13C] glucose (Shen et al., 1999) in the same volunteer. Differences between the two spectra reflect the compartmentation of acetate metabolism in glia as opposed to glucose, which is mainly consumed by neurons.

Figure 2b shows a spectrum acquired from the same volunteer under identical experimental conditions over the last 40 min of a [1-13C] glucose infusion reported previously by Shen et al. (1999). The two spectra exhibit clear differences in labeling patterns, reflecting cell-type specific metabolism: 13C from acetate C2 is incorporated predominantly into brain glutamine, whereas13C from glucose C1 leads to higher labeling of glutamate. This observation is consistent with previousin vivo and ex vivo findings from animal brain studies (Hassel et al., 1995; Bachelard, 1998) that acetate and glucose are metabolized primarily in different metabolic compartments in human brain, astroglia and neurons, respectively.

Estimate of the contribution of labeled glutamine in white matter

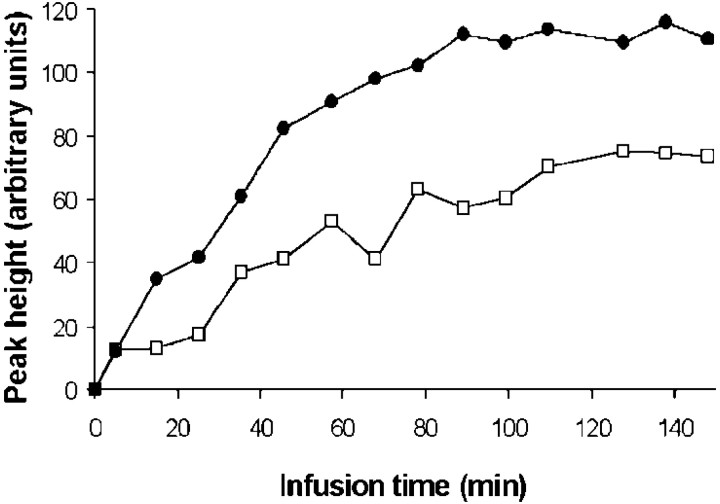

The time course of glutamine and glutamate C4 were measured during the entire course of infusion in four volunteers (Fig.3). The summed time courses were analyzed to determine the fraction of steady-state labeling arising from gray matter and white matter. Because there should be no discernable neurotransmitter glutamate cycling in white matter, glutamine C4 would be expected to be labeled in white matter through the de novo synthesis of glutamine at the rateVeff, assuming that the small brain acetate pool is rapidly labeled from blood acetate. A negligible delay in the glutamine C4 labeling from brain acetate was assumed because of the fast isotopic turnover of the small glial glutamate pool (Ottersen et al., 1992). In contrast to white matter, glutamine C4 may be labeled through the Glu/Gln cycle in gray matter, leading to a higher rate of labeling (Vcycle +Veff).

Fig. 3.

Time course of [4-13C] glutamine (filled circles) and [4-13C] glutamate (open squares) NMR signals measured in one subject during [2-13C] acetate infusion. These curves are proportional to the concentrations of 13C over natural abundance in the C4 positions.

To quantitatively compare 13C incorporation from acetate into white matter (VasWM) with13C incorporation into gray matter (VasGM), the Glu/Gln cycle model (Fig.1a) was partitioned into two compartments representing gray and white matter using the software Cwave (G. F. Mason).VasWM andVasGM were iterated to fit the experimental glutamine C4 time course. The gray/white matter content in the voxel of interest was assessed by segmentation MRI. We usedVeff of 0.04 μmol · gm−1 · min−1, as reported by Shen et al. (1999). The label incorporation into the white matter glial TCA cycle, VasWM, was only 15 ± 5% of the gray matter value,VasGM. Knowing that glutamine and glutamate concentrations in white matter are typically twice as small as in gray matter (Michaelis et al., 1993) and that our voxels of interest contain a majority of gray matter, the contribution of white matter to the measured signal does not exceed ∼7%. Thus, the NMR measurement primarily reflects gray matter metabolism (∼93%). The preponderance of labeling of glutamine in gray matter by acetate, with minimal labeling of white matter, most likely reflects the participation of the majority of glutamine synthesis in the glutamate/glutamine cycle. It also reflects the lack of the enzyme glutamine synthetase in oligodendrocytes, which are the most abundant white matter glia (Norenberg and Martinez-Hernandez, 1979).

Estimate of the glial glutamate pool size

The determination of the astroglial and neuronal glutamate enrichment required calculation of the size of the astroglial glutamate pool. The astroglial glutamate pool concentration was assessed from a detailed analysis of the time course of glutamate and glutamine C4. Because glutamate is significantly less concentrated in astrocytes than in neurons (Van den Berg and Garfinkle, 1971; Ottersen et al., 1992), the astroglial glutamate pool is expected to reach steady state faster than the neuronal pool. Moreover, if neuronal glutamate is labeled, then the 13C incorporation in this larger pool is delayed because of the transfer of13C from the astroglial to the neuronal compartment. Based on this and in accordance with earlier14C acetate studies of rat brain metabolism (Van den Berg and Garfinkle, 1971), we assumed that astroglial glutamate reached isotopic steady state much earlier than neuronal glutamate during the [2-13C] acetate infusion. The glutamate 13C labeling detected over the first 20 min of infusion was considered as reflecting steady-state astroglial glutamate only. Knowing that, at the end of infusion, total glutamine reaches the same FE as astroglial glutamate (steady-state equilibrium), steady-state glutamine FE (10.4% as measured on a reference phantom) yielded the following: [Glug] of 0.7 ± 0.5 mm.

Determination of the dominant pathway for neuronal glutamate repletion

A limitation of using [1-13C] glucose to study neuronal/astroglial glutamate trafficking in vivo is that it is difficult to distinguish potential cycling pathways attributable to label entering both the neuron and astrocyte. To determine what mechanism is dominant in the human brain, the measured ratio of the concentrations of [4-13C] glutamate and [4-13C] glutamine from acetate was compared with the prediction of the models of glutamate repletion. The [4-13C] glutamate concentration was expressed as the product of glutamate fractional enrichment and the glutamate concentration in the labeled compartment y (glia or neuron depending on the model): [Glu13C4] = GluyC4 × [Gluy]. The corresponding expression for glutamine leads to the concentration ratio: [Glu13C4]/[Gln13C4] = GluyC4/GlnyC4 × [Gluy]/[Glny]. Steady-state solutions of the differential equations describing each model allow for prediction of the fractional enrichment ratio GluyC4/GlnyC4 (Table1), and estimates of glutamate and glutamine concentrations lead to the ratio [Gluy]/[Glny].

Table 1.

Differential equations describing 13C incorporation into gray matter according to three different models of neurotransmitter glutamate repletion

| Glu/Gln cycle model |

|---|

| d[GlngC4]/dt = (Vcycle +Veff)·GlugC4 − (Vcycle +Veff)·GlngC4 |

| d[GlnnC4]/dt =Vcycle·GlngC4 −Vcycle·GlnnC4 |

| d[GlunC4]/dt =Vcycle·GlnnC4 − (Vcycle +VTCAn)·GlunC4 |

| d[GlugC3]/dt = (VTCAg +Veff)·OAAgC3 +Vcycle·GlunC3 − (Vcycle + Veff +VTCAg)·GlugC3 |

| d[GlngC3]/dt = (Vcycle +Veff)·GlugC3 − (Vcycle +Veff)·GlngC3 |

| d[OAAgC3]/dt = ½VTCAg·(GlugC3 + GlugC4) − (VTCAg +Veff)·OAAgC3 |

| Internal exchange model |

| d[GlngC4]/dt =Veff·GlugC4 −Veff·GlngC4 |

| Glu/αKG cycle model |

| d[GlngC4]/dt =Veff·GlugC4 −Veff·GlngC4 |

| d[GlunC4]/dt =V′cycle·GlugC4 − (V′cycle +VTCAn)·GlunC4 |

Only the differential equations used to test the models and to derive metabolic fluxes are given. [GlxyCz] is the concentration of metabolite Glx (Glu or Gln) labeled in the positionz in the compartment y (glial or neuronal cells) of gray matter.

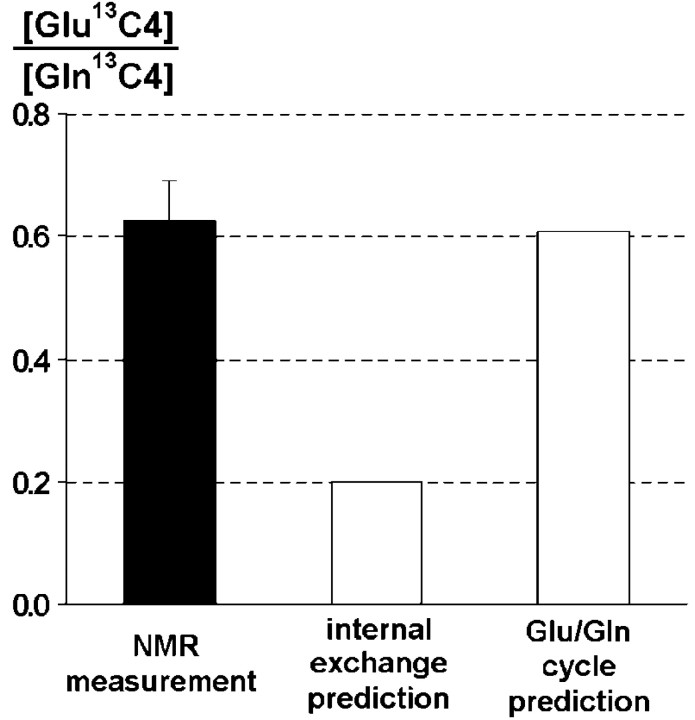

For the internal exchange model (Fig. 1b), the predicted fractional enrichment ratio GlugC4/GlngC4 = 1, because the differential equations predict identical glutamate and glutamine fractional enrichments in glia from [2-13C] acetate at steady state, with no labeling of neuronal glutamate. Using the concentration of glial glutamate measured in the present study, which is consistent with previous results using histochemical staining (Ottersen et al., 1992) and 14C tracers (Van den Berg and Garfinkle, 1971) leads to a maximum value of the concentration ratio: [Glu13C4]/[Gln13C4] = 0.2. However, the measured concentration ratio [Glu13C4]/[Gln13C4] = 0.63 ± 0.07 is three times greater than the predicted value based on this model, indicating that there is a large transfer of13C label from the astrocyte to the neuron (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Ratio of glutamate 13C4 and glutamine13C4 concentrations measured and predicted by different models of glutamate replenishment. As opposed to the internal exchange model, the glutamate/glutamine cycle model is in excellent agreement with the experimental results.

In the Glu/Gln cycle pathway, the 13C label is transferred from glial glutamine to neuronal glutamate. The differential equations describing this model predict the following relationship between the fractional enrichments of glutamate and glutamine C4:

| Equation 1 |

where VTCAn is the neuronal TCA cycle flux, and Vcycle is the rate of neuronal glutamate repletion by the Glu/Gln cycle.Vcycle andVTCAn have been measured previously in a similar region in the human parietal-occipital cortex during an infusion of [1-13C] glucose, yielding values of 0.32 and 0.80 μmol · gm−1 · min−1, respectively (Mason et al., 1999; Shen et al., 1999). Based on these values, the predicted [Glu13C4]/[Gln13C4] ratio for the Glu/Gln cycle model is 0.61, showing an excellent agreement with the measured ratio (0.63).

In the metabolic modeling of the glucose data, the flux of13C label from neuronal glutamate to astroglial glutamine was calculated to determineVcycle, which does not include the contribution through the Glu/α-KG cycle (at the rateV′cycle) because the later does not label glutamine. Therefore, glucose-based measurements of Glu/Gln cycling reflect Vcycle, whereas acetate-based measurements reflect Vcycle +V′cycle. If the Glu/α-KG model is taken into account, an additional cycle flux must be added between neuronal and glial glutamate pools (Fig. 1c), leading to the predicted fractional enrichment ratio:

| Equation 2 |

Because the addition of V′cyclewould affect the prediction for the steady-state [Glu13C4]/[Gln13C4] ratio, our measurement rules out the possibility of a major contribution of the Glu/α-KG cycle to neuronal glutamate replenishment. Within measurement accuracy,V′cycle is at most 10% ofVcycle, indicating a minor role for the Glu/α-KG cycle under normal physiological conditions. Together, these findings strongly support the glutamate/glutamine cycle as being a major metabolic flux and glutamine as the primary source of neuronal glutamate replenishment in human brain.

Calculation of Vcycle andVTCAg

Based on the label distribution implied by the Glu/Gln cycle model, glutamate and glutamine C4 and C3 NMR signals were converted into gray matter fractional enrichments after correction for white/gray matter distribution and the respective concentrations of glutamate in neurons and astroglia (Table 2).

Table 2.

Fractional enrichments (over natural abundance) of neuronal glutamate and glutamine C4 and C3 in gray matter measured at steady state during the [2-13C] acetate infusion (n= 8; mean ± SD)

| Gln C4 | Gln C3 | Glu C4 | Glu C3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | 10.4 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 2.1 |

| SD | 2.4 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

The differential equations describing 13C incorporation according to the Glu/Gln cycling model can be solved analytically under steady-state conditions, leading to the following relationships between Vcycle,VTCAg, andVTCAn:

| Equation 3 |

| Equation 4 |

where VTCAg is the glial TCA cycle flux, and GlxyCz is the fractional enrichment (over natural abundance) of the metabolite Glx in carbon atom position z, in cellular compartment y (i.e., glial or neuronal pool).

Equation 3 allows for calculation of theVcycle/VTCAnratio, which reflects the contribution of neuronal/glial trafficking to neuronal metabolism. We measured aVcycle/VTCAnratio of 0.39 ± 0.09.

Using VTCAn of 0.80 μmol · gm−1 · min−1and Veff of 0.04 μmol · gm−1 · min−1for gray matter as measured previously in humans using [1-13C] glucose (Mason et al., 1999;Shen et al., 1999), Equations 3 and 4 yieldedVcycle of 0.32 ± 0.07 μmol · gm−1 · min−1and VTCAg of 0.14 ± 0.06 μmol · gm−1 · min−1.

DISCUSSION

The glutamate/glutamine cycle is the major pathway of neuronal glutamate repletion in the human cerebral cortex

Comparison of the measurement of rate of total neuronal/glial glutamate trafficking, with a previous study using [1-13C] glucose (Shen et al., 1999), which measured the glutamate/glutamine cycle, indicates that the large majority of glutamate trafficking under normal conditions is through the glutamate/glutamine cycle. The value of the ratioVcycle/VTCAnin the present study was 0.39 ± 0.09, which is slightly lower than the value of 0.46 ± 0.10 reported by Shen et al. (1999)using [1-13C] glucose. This difference may be explained by the specificity of acetate for gray matter in which TCA cycle flux is significantly higher than in white matter (Mason et al., 1999). When the fluxes reported previously are corrected for the small contribution from the white matter TCA cycle, the value of the ratio (0.40 ± 0.06) is not significantly different from the value determined using [2-13C] acetate.

The determination ofVcycle/VTCAnfrom the [2-13C] acetate data depends on an estimate of the partition of glutamate between glia and neurons. Using an approach pioneered by workers using14C acetate in animal models (Van den Berg and Garfinkel, 1971), we estimated the glial glutamate concentration based on the relative labeling of glutamine and glutamate at a time point early enough that neuronal glutamate labeling may be neglected to a first order. Consistent with previous studies, we found a low value of glial glutamate, ∼0.7 mm. To the extent that there was also neuronal glutamate labeling at the time point used, this value would be an overestimate of the actual glutamate in the glia, and the ratioVcycle/VTCAnwould be slightly underestimated.

The calculation of Vcycle from the acetate data (assuming VTCAn of 0.80 μmol · gm−1 · min−1as measured in human gray matter) leads to 0.32 ± 0.07 μmol · gm−1 · min−1. This value is the same as the one measured during [1-13C] glucose infusions (0.32 ± 0.05 μmol · gm−1 · min−1) (Shen et al., 1999). The excellent agreement with the studies that used labeled glucose validates the NMR measurement ofVcycle and indicates the Glu/Gln cycle as the major pathway of glutamate neuronal/glial trafficking in the human cerebral cortex.

The astroglial TCA cycle accounts for 14% of the total human brain TCA cycle flux

The ratio of the astroglial TCA cycle rate to the total TCA cycle is consistent with previous studies of the mouse brain (0.17–0.19) (Van den Berg and Garfinkel, 1971; Hassel et al., 1995) and approximately two times higher than reported in humans by our group previously using [1-13C] glucose (Shen et al., 1999). The difference is primarily attributable to the relative insensitivity of the [1-13C] glucose experiment to this flux because of label entry at both neuronal and glial pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and extensive mixing of label between these compartments by the glutamate/glutamine cycle. The specificity of acetate entry into the glial TCA cycle allowed a more accurate measure of VTCAg. The value of VTCAg is closer to the glial PDH flux of 0.15 μmol · gm−1 · min−1reported by Gruetter et al. (1998, 2001) in human occipital cortex studied at 4 T using [1-13C] glucose as a label. However, in the Gruetter et al. studies, most of the rate of glial PDH was coupled to pyruvate carboxylase and efflux from the TCA cycle at α-ketoglutarate, whereas, in contrast, the findings with acetate support most of the glial acetyl-CoA production being involved in a complete TCA cycle. These findings may be reconciled if most of the pyruvate carboxylase flux is coupled to an “oxaloacetate/malate/pyruvate” recycling pathway operating through malic enzyme and pyruvate carboxylase rather than net anaplerosis and glutamine efflux. It has been suggested that there is a need for this pathway for the replacement of glutamate lost in the astrocyte to oxidation (Hertz et al., 1999; Lieth et al. 2001), as is discussed further below. Alternatively, this pathway may be used to generate NADPH in the glial cytosol. Indeed, malic enzyme and pyruvate carboxylase have been detected in glia (Shank et al., 1985; Kurz et al., 1993), and the importance of this recycling pathway has been demonstrated in other human tissues in which these enzymes are expressed (Petersen et al., 1995; Jones et al., 1997).

Influence of glutamine efflux on the calculated astroglial TCA cycle flux

As shown by Equation 4, the glutamine effluxVeff is required to deriveVTCAg from the NMR measurement. We used a value of Veff of 0.04 μmol · gm−1 · min−1, as estimated in a previous study of the human parietal-occipital lobe (Shen et al., 1999). However, there is no real consensus on the value of glutamine efflux in human brain, as reflected by the wide range of literature values (0.003–0.08 μmol · gm−1 · min−1). To assess the influence of Veff on the calculated astroglial TCA cycle flux,VTCAg was calculated for the lowest possible Veff (assuming no glutamine efflux) and the highest glutamine efflux reported in the literature (Gruetter et al., 1998) in which it was assumed that all labeling through anaplerosis represents replacement of lost TCA cycle intermediates through glutamine. ForVeff of 0 and 0.08 μmol · gm−1 · min−1,VTCAg was 0.10 ± 0.06 and 0.18 ± 0.07 μmol · gm−1 · min−1, respectively. If the measured anaplerotic flux instead represents oxaloacetate (OAA) or pyruvate recycling andVeff is negligible, then the lower value will hold.

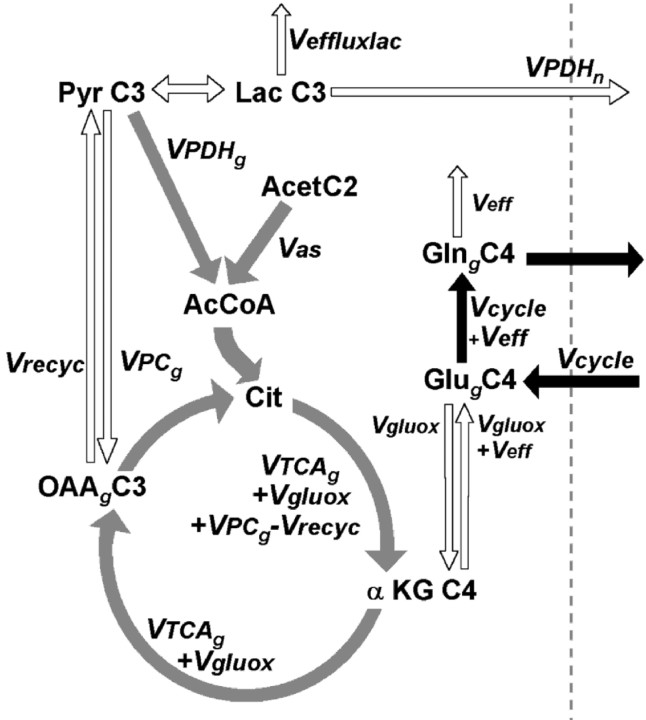

Contributions to glutamate C4 labeling from pyruvate recycling

The three models tested here do not take into account metabolic pathways such as pyruvate recycling, glutamate oxidation, and lactate transfer from glial to neuronal cells. A detailed diagram of the astroglial compartment including these pathways is presented in Figure5. Under physiological conditions, pyruvate recycling (Vrecyc) through malic enzyme is considered to occur in the astroglial compartment only (Haberg et al., 1998; Lieth et al. 2001; Sibson et al., 2001), although there may be direct neuronal glutamate repletion through malic enzyme (Hassel and Brathe, 2000). Pyruvate produced by this pathway may be converted to lactate and potentially transported to neurons and converted to acetyl-CoA by PDH (Bouzier et al., 2000). Flux through this pathway may lead to an overestimate of the glutamate/glutamine cycle by bringing additional label into neuronal glutamate C4. Although the flux associated with pyruvate recycling cannot be determined uniquely from the present data, it can be shown that this flow insignificantly affects the13C distribution of brain glutamate and glutamine C4 labeling from [2-13C] acetate. Indeed, the FE of lactate C3 resulting from pyruvate recycling cannot exceed 0.3% above natural abundance (see ), which does not significantly affect our calculations of glial/neuronal glutamate trafficking. This conclusion is consistent with in vivostudies in animal models using [2-13C] acetate (Hassel et al., 1995, Haberg et al., 1998) and [2-13C] glucose (Sibson et al. 2001).

Fig. 5.

Pyruvate recycling through malic enzyme or PEPCK (Vrecyc) and glutamate oxidation and cycling into the astroglial TCA cycle (Vgluox). Combined with lactate transfer to neurons, these pathways could potentially alter the13C distribution into brain glutamate and glutamine described in Figure 1. However, it can be calculated that these fluxes do not contribute significantly to glutamate and glutamine C4 labeling during an infusion of [2-13C] acetate.VPDHg, Glial pyruvate dehydrogenase flux; VPDHn, neuronal pyruvate dehydrogenase flux;VPCg, glial pyruvate carboxylase flux (Vana =Veff =VPCg −Vrecyc);Veffluxlac, lactate efflux from the brain.

Estimate of glutamate oxidation

In the glutamate oxidation pathway (Vgluox), glutamate released by the neuron is taken up by the glia, converted through glutamate dehydrogenase or transamination to α-ketoglutarate, converted by the glial TCA cycle to malate, converted from malate to pyruvate through malic enzyme, and then oxidized by pyruvate dehydrogenase in the glia (Hertz et al., 1999; Lieth et al., 2001). Glutamate lost to the system by oxidation is replaced by anaplerosis, starting with the conversion by pyruvate carboxylase (VPC) of pyruvate to OAA. Glial glutamate formed by this pathway will then be cycled back to the neuron as either glutamine or α-ketoglutarate. Thus, the calculation ofVcycle/VTCAnfrom acetate will include this pathway. Because glutamate in this pathway traverses the TCA cycle from α-ketoglutarate to OAA, the upper limit of the rate of this pathway is given by the astroglial TCA cycle, leading to Vgluox <VTCAg of 0.14 ± 0.06 μmol · gm−1 · min−1. Because the glutamate oxidation flux cannot exceed the rate of anaplerosis, ∼30% of the glutamine transferred to the neurons by the cycle may derive from replacement of oxidized glutamate by anaplerosis.

An alternate repletion source for the glutamate oxidation pathway has been proposed previously (Hassel, 2000), in which neurons use malic enzyme to directly replete glutamate. This pathway would not be detected using [2-13C] acetate as a label precursor, so that the rate cannot be calculated. The in vivo rate of this pathway is most likely small based on recent studies of the rat brain using [2-13C] glucose and [14CO2] as a label source in vivo, both of which would be incorporated by neuronal malic enzyme. These studies found labeling consistent with glial a naplerosis and the glutamate/glutamine cycle being the major glutamate repletion pathway (Lieth et al. 2001; Sibson et al. 2001)

Conclusions and applications

The results demonstrate the ability of13C NMR in combination with selective astroglial labeling with [2-13C] acetate to study glial metabolism in humans. Astroglia contribute ∼15% of the total oxidative metabolism, and the glutamate/glutamine cycle is the major source of neuronal glutamate repletion, with up to 30% of this flux contributed by anaplerosis replacing oxidized glutamate The high specificity of acetate for astroglial metabolism should prove useful for exploring the role of astroglia in supporting functional neuroenergetics, as well as alterations of neuronal/glial trafficking under pathological conditions.

Pyruvate recycling, glutamate oxidation, and lactate transport to neurons were modeled as shown in Figure 5. Pyruvate recycling may lead to the transfer of label from [2-13C] acetate to neuronal glutamate C4 by conversion of malate into [3-13C] pyruvate, followed by conversion to lactate, transport to the neuron, and oxidation there by the TCA cycle. An upper estimate of the contribution of these pathways to13C labeling of glutamate C4 during [2-13C] acetate infusion was calculated as follows. The isotope balance equation for OAAgC3 in the astrocyte at steady state is given by the following:

| Equation A1 |

The second term in the brackets comes from mass balance considerations and is the mass flow into citrate from OAA. This leads to the following:

| Equation A2 |

The cancellation of Vrecyc is attributable to OAA that is converted to pyruvate and then back to OAA, as would be the case for NADPH production via a malic enzyme/pyruvate carboxylase futile cycle, not being a net flux out of the OAA pool.

For lactate (assuming glial and neuronal lactate are effectively one pool, which is maximum transfer to neuron), we have the following:

| Equation A3 |

Substituting Equation EA2 into A1 to eliminate OAAgC3 as follows:

| Equation A4 |

If we assume that, under these conditions, malic enzyme is not active in the neuron, then all of the label incorporation into lactate C3 is in the astrocyte. A maximum estimate of lactate C3 labeling is under the conditions in which the astroglial and neuronal lactate pool are in rapid equilibrium (or alternatively, most of the lactate is made in the astrocyte first).

Because at metabolic steady state any carbon lost from the glial TCA cycle by pyruvate recycling must be replenished by pyruvate carboxylase, the maximum possible value forVrecyc isVrecyc =VPCg. Substituting and rearranging yields the following:

| Equation A5 |

From [2-13C] glucose and other labeling studies in animals (Sibson et al., 2001), we know that at mostVPCg ≈ 0.05–0.1 · (VPDHn +VPDHg). From the glutamine C4/C3 labeling patterns observed in this study, we also know thatVTCAg +Vgluox ≈ 0.1 · (VPDHn +VPDHg). Ignoring lactate efflux to the first order yields the following:

| Equation A6 |

from which the highest estimate of lactate C3 fractional enrichment is as follows:

| Equation A7 |

The neuronal glutamate C4 enrichment from this lactate pool is given by the following:

| Equation A8 |

where the dilution factor DF refers to dilution of glutamate C4 relative to its lactate precursor, which, based on animal models and human studies (Mason et al., 1999), is ∼10–20% (DF of 0.8–0.9). Knowing that GlngC4 and GlngC3 are ∼10 and 3%, we obtain GlunC4 ≈ 0.3%, which makes the maximum label from pyruvate recycling into glutamate C4 on the same order of magnitude as the noise of our measurements.

Footnotes

This work was supported by United States Public Health Service Grants RO1 DK-49230, P30 DK-45735, MO1 RR-00125, and R01 NS37527–03 and a Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Center Award for the Study of Hypoglycemia. K.F.P. is the recipient of a K-23 award from the National Institutes of Health, V.L. and S.D. are research associates, and G.I.S. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. We thank Dr. Chunli Yu, Yanna Kosover, Amy Dennean, Tony Romanelli, and the staff of the Yale–New Haven Hospital General Clinical Research Center for expert technical assistance, Terry Nixon for maintenance and upgrades to the spectrometer, Peter Brown for coil construction, and Drs. Robert Shulman, Ognen Petroff, Jullie Pan, James Lai, and Robert Sherwin for valuable conversations about the interpretation of this study.

Correspondence should be addressed to Douglas L. Rothman, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, P.O. Box 208043, 330 Cedar Street, New Haven, CT 06520-8043. E-mail: douglas.rothman@yale.edu.

V. Lebon's present address: Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique/Service Hospitalier Frédéric Joliot, 4 place du Général Leclerc, 91401 Orsay Cedex, France.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alberati-Giani D, Malherbe P, Kohler C, Lang G, Kiefer V, Lahm H-W, Cesura AM. Cloning and characterization of a soluble kynurenine aminotransferase from rat brain: identity with kidney cycteine conjugate β-lyase. J Neurochem. 1995;64:1448–1455. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64041448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachelard H. Landmarks in the application of 13C-magnetic resonance spectroscopy to studies of neuronal/glial relationships. Dev Neurosci. 1998;20:277–288. doi: 10.1159/000017322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badar-Goffer RS, Bachelard HS, Morris PG. Cerebral metabolism of acetate and glucose studied by 13C-n.m.r. spectroscopy. A technique for investigating metabolic compartmentation in the brain. Biochem J. 1990;266:133–139. doi: 10.1042/bj2660133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berl S, Takagaki G, Clarke DD, Waelsch H. Metabolic compartments in vivo: ammonia and glutamic acid metabolism in brain and liver. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:2562–2569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bluml S, Moreno-Torres A, Ross BD. [1–13C]glucose MRS in chronic hepatic encephalopathy in man. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45:981–993. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouzier AK, Thiaudiere E, Biran M, Rouland R, Canioni P, Merle M. The metabolism of [3-(13)C]lactate in the rat brain is specific of a pyruvate carboxylase-deprived compartment. J Neurochem. 2000;75:480–486. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerdan S, Kunnecke B, Seelig J. Cerebral metabolism of [1,2-13C2]acetate as detected by in vivo and in vitro 13C NMR. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:12916–12926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper AJ, Plum F. Biochemistry and physiology of brain ammonia. Physiol Rev. 1987;67:440–519. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1987.67.2.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erecinska M, Silver IA. Metabolism and role of glutamate in mammalian brain. Prog Neurobiol. 1990;35:245–296. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(90)90013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gruetter R, Novotny EJ, Boulware SD, Mason GF, Rothman DL, Shulman GI, Prichard JW, Shulman RG. Localized 13C NMR spectroscopy in the human brain of amino acid labeling from D-[1-13C]glucose. J Neurochem. 1994;63:1377–1385. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63041377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gruetter R, Seaquist ER, Kim S, Ugurbil K. Localized in vivo 13C-NMR of glutamate metabolism in the human brain: initial results at 4 Tesla. Dev Neurosci. 1998;20:380–388. doi: 10.1159/000017334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gruetter R, Seaquist ER, Ugurbil K. A mathematical model of compartmentalized neurotransmitter metabolism in the human brain. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281:E100–E112. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.1.E100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haberg A, Qu H, Bakken IJ, Sande LM, White LR, Haraldseth O, Unsgard G, Aasly J, Sonnewald U. In vitro and ex vivo 13C-NMR spectroscopy studies of pyruvate recycling in brain. Dev Neurosci. 1998;20:389–398. doi: 10.1159/000017335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassel B. Carboxylation and anaplerosis in neurons and glia. Mol Neurobiol. 2000;22:21–40. doi: 10.1385/MN:22:1-3:021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassel B, Brathe A. Neuronal pyruvate carboxylation supports formation of transmitter glutamate. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1342–1347. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01342.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hassel B, Sonnewald U, Fonnum F. Glial-neuronal interactions as studied by cerebral metabolism of [2-13C]acetate and [1-13C]glucose: an ex vivo 13C NMR spectroscopic study. J Neurochem. 1995;64:2773–2782. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64062773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hertz L, Dringen R, Schousboe A, Robinson SR. Astrocytes: glutamate producers for neurons. J Neurosci Res. 1999;57:417–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogstad S, Svenneby G, Torgner IA, Kvamme E, Hertz L, Schousboe A. Glutaminase in neurons and astrocytes cultured from mouse brain: kinetic properties and effects of phosphate, glutamate, and ammonia. Neurochem Res. 1988;13:383–388. doi: 10.1007/BF00972489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones JG, Naidoo R, Sherry AD, Jeffrey FM, Cottam GL, Malloy CR. Measurement of gluconeogenesis and pyruvate recycling in the rat liver: a simple analysis of glucose and glutamate isotopomers during metabolism of [1,2,3-(13)C3]propionate. FEBS Lett. 1997;412:131–137. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00764-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunnecke B, Cerdan S. Multilabeled 13C substrates as probes in in vivo 13C and 1H NMR spectroscopy. NMR Biomed. 1989;2:274–277. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940020516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurz GM, Wiesinger H, Hamprecht B. Purification of cytosolic malic enzyme from bovine brain, generation of monoclonal antibodies, and immunocytochemical localization of the enzyme in glial cells of neural primary cultures. J Neurochem. 1993;60:1467–1474. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kvamme E, Schousboe A, Hertz L, IAa, Torgner, Svenneby G. Developmental change of endogenous glutamate and gamma-glutamyl transferase in cultured cerebral cortical interneurons and cerebellar granule cells, and in mouse cerebral cortex and cerebellum in vivo. Neurochem Res. 1985;10:993–1008. doi: 10.1007/BF00964635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieth E, LaNoue KF, Berkich DA, Xu B, Ratz M, Taylor C, Hutson SM. Nitrogen shuttling between neurons and glial cells during glutamate synthesis. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1712–1723. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lundquist F. Production and utilization of free acetate in man. Nature. 1962;193:579–580. doi: 10.1038/193579b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magistretti PJ, Pellerin L, Rothman DL, Shulman RG. Energy on demand. Science. 1999;283:496–497. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5401.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makar TK, Nedergaard M, Preuss A, Hertz L, Cooper AJL. Glutamine transaminase K and ω-amidase activities in primary cultures of astrocytes and neurons and in embryonic chick forebrain: marked induction of brain glutamine transaminase K at time of hatching. J Neurochem. 1994;62:1983–1988. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62051983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez-Hernandez A, Bell KP, Norenberg MD. Glutamine synthetase: glial localization in brain. Science. 1977;195:1356–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.14400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mason GF, Pan JW, Chu WJ, Newcomer BR, Zhang Y, Orr R, Hetherington HP. Measurement of the tricarboxylic acid cycle rate in human grey and white matter in vivo by 1H-[13C] magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 4.1T. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:1179–1188. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199911000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michaelis T, Merboldt KD, Bruhn H, Hanicke W, Frahm J. Absolute concentrations of metabolites in the adult human brain in vivo: quantification of localized proton MR spectra. Radiology. 1993;187:219–227. doi: 10.1148/radiology.187.1.8451417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norenberg MD, Martinez-Hernandez A. Fine structural localization of glutamine synthetase in astrocytes of rat brain. Brain Res. 1979;161:303–310. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okuno E, Nakamura M, Schwarcz R. Two kynurenine aminotransferases in human brain. Brain Res. 1991;542:307–312. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91583-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ottersen OP, Zhang N, Walberg F. Metabolic compartmentation of glutamate and glutamine: morphological evidence obtained by quantitative immunocytochemistry in rat cerebellum. Neuroscience. 1992;46:519–534. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90141-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petersen KF, Blair JB, Shulman GI. Triiodothyronine treatment increases substrate cycling between pyruvate carboxylase and malic enzyme in perfused rat liver. Metabolism. 1995;44:1380–1383. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(95)90133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rothman DL, Novotny EJ, Shulman GI, Howseman AM, Petroff OA, Mason G, Nixon T, Hanstock CC, Prichard JW, Shulman RG. 1H-[13C] NMR measurements of [4-13C]glutamate turnover in human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9603–9606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothstein JD, Dykes-Hoberg M, Pardo CA, Bristol LA, Jin L, Kuncl RW, Kanai Y, Hediger MA, Wang Y, Schielke JP, Welty DF. Knockout of glutamate transporters reveals a major role for astroglial transport in excitotoxicity and clearance of glutamate. Neuron. 1996;16:675–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schousboe A, Westergaard N, Waagepetersen HS, Larsson OM, Bakken IJ, Sonnewald U. Trafficking between glia and neurons of TCA cycle intermediates and related metabolites. Glia. 1997;21:99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schumann WC, Magnusson I, Chandramouli V, Kumaran K, Wahren J, Landau BR. Metabolism of [2-14C]acetate and its use in assessing hepatic Krebs cycle activity and gluconeogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6985–6990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shank RP, Campbell GL. Alpha-ketoglutarate and malate uptake and metabolism by synaptosomes: further evidence for an astrocyte-to-neuron metabolic shuttle. J Neurochem. 1984;42:1153–1161. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb12724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shank RP, Bennett GS, Freytag SO, Campbell GL. Pyruvate carboxylase: an astrocyte-specific enzyme implicated in the replenishment of amino acid neurotransmitter pools. Brain Res. 1985;329:364–367. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90552-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen J, Rycyna RE, Rothman DL. Improvements on an in vivo automatic shimming method (FASTERMAP). Magn Reson Med. 1997;38:834–839. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen J, Petersen KF, Behar KL, Brown P, Nixon TW, Mason GF, Petroff OA, Shulman GI, Shulman RG, Rothman DL. Determination of the rate of the glutamate/glutamine cycle in the human brain by in vivo 13C NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8235–8240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shine HD, Hertz L, De Vellis J, Haber B. A fluorometric assay for gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase: demonstration of enzymatic activity in cultured cells of neural origin. Neurochem Res. 1981;6:453–463. doi: 10.1007/BF00963860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sibson NR, Dhankhar A, Mason GF, Behar KL, Rothman DL, Shulman RG. In vivo 13C NMR measurements of cerebral glutamine synthesis as evidence for glutamate-glutamine cycling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2699–2704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sibson NR, Dhankhar A, Mason GF, Rothman DL, Behar KL, Shulman RG. Stoichiometric coupling of brain glucose metabolism and glutamatergic neuronal activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:316–321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sibson NR, Mason GF, Shen J, Cline GW, Herskovits AZ, Wall JE, Behar KL, Rothman DL, Shulman RG. In vivo 13C NMR measurement of neurotransmitter glutamate cycling, anaplerosis, TCA cycle flux in rat brain during [2–13C]glucose infusion. J Neurochem. 2001;76:975–989. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van den Berg CJ, Garfinkel D. A simulation study of brain compartments. Biochem J. 1971;123:211–218. doi: 10.1042/bj1230211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van den Berg CJ, Krzalic L, Mela P, Waelsch H. Compartmentation of glutamate metabolism in brain. Evidence for the existence of two different tricarboxylic acid cycles in brain. Biochem J. 1969;113:281–290. doi: 10.1042/bj1130281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waniewski RA, Martin DL. Exogenous glutamate is metabolized to glutamine and exported by rat primary astrocyte cultures. J Neurochem. 1986;47:304–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb02863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waniewski RA, Martin DL. Preferential utilization of acetate by astrocytes is attributable to transport. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5225–5233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05225.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu AC, Drejer J, Hertz L, Schousboe A. Pyruvate carboxylase activity in primary cultures of astrocytes and neurons. J Neurochem. 1983;41:1484–1487. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]